Abstract

Reading is one of many things vying for young people’s attention. In the case of volitional reading, young people between 8 and 15 are following trends of less enjoyment of reading and declining time spent reading. There are complex explanations for patterns of decline in their volitional reading related to how choice is afforded within social and material relations. This article offers a glimpse into the motivations for young people’s volitional reading through placing a socio-material lens on descriptive statistics. Affect theory provides new ways of comprehending and using patterns in children and young people’s relationships to reading, recognising these as mutable and contingent relations within reading assemblages. Reading affect in volitional reading describes felt experiences of encountering other bodies (human and nonhuman) through reading. The secondary data from the Growing Up in New Zealand longitudinal cohort measures the physical, social, and cultural dimensions of over 6000 children in Aotearoa New Zealand. Descriptive statistical analyses showed relationships between reading enjoyment and frequency at age 8 and over 60 variables from throughout their life course. We comprehend reading affect by applying our socio-material lens to variables related to reading enjoyment assembled within a rough approximation of the complex arrangements of young people’s lives at home and in out of home experiences. Through reflecting upon associations identified in statistics, we find potential in encounters with other people and things to draw young people back into reading, rather than act as distractions.

Introduction

Reading is one of many things vying for young people’s attention. In the case of volitional reading, that is, reading ‘in which we choose to engage’ (Kucirkova and Cremin Citation2020, p. 2), young people between 8 and 15 are following trends of less enjoyment of reading and declining time spent reading (OECD Citation2021). There are complex explanations for patterns of decline in their volitional reading. Some of these explanations are related to how choice is afforded within social and material relations. Self-concept and choice in reading are constrained by deeply embedded and stereotypically gendered assumptions (Scholes et al. Citation2021) or follow lines of family socio-economic status (Sullivan and Brown Citation2015). The deep reading that sustains critical thought and contemplation is declining as young people’s engagement with technology increases (Wolf Citation2018). However, understanding the reasons behind declines does not necessarily help to reverse them.

Studies on young people’s out-of-school literacy activities in Aotearoa New Zealand show reading is only one of various things they do in their free time (Cummings et al. Citation2018), and perhaps not their most favoured (Wylie Citation2004). Motivation to read is established and undone as young people experience various ways of being with other people, encounter new objects, and explore different ways of engaging with them (Cummings et al. Citation2018; Neugebauer and Gilmour Citation2020). Literacy researchers have sought to learn from children’s volitional reading so those relations may be reproduced in classrooms (Damaianti Citation2017). In recognising the influence of volitional reading upon school literacy achievement, researchers pay closer attention to children and young people’s outside of school reading (Rutherford et al. Citation2018).

We approach volitional reading, or reading as a chosen form of engagement, from an affective position, where reading affect describes felt experiences of encountering and affecting other bodies, human and nonhuman, through reading (Johnson Citation2019). We seek further understanding of the affective, relational experiences that motivate and sustain young people’s volitional reading, before reading and what it enables slips away, or ‘before the changes to the reader’s brain are so ingrained that there is no going back’ (Wolf Citation2018, p. 14). Reading when viewed as affective experience is hard to study, because like other forms of aesthetic experience, there are many factors at play and the felt experience is comprised of more than its constituent parts (Marin et al. Citation2016). We use transdisciplinary methodology, inspired by others who attempt to cross a divide in literacy research between using quantitative methods to illuminate relationships between variables or components of reading while simultaneously considering the unity of reading experiences (Pulvirenti et al. Citation2020). There are new possibilities for motivating and sustaining volitional reading in the refinement and rearrangement of relations between things within new wholes or assemblages.

In this article, we bring affect theory into an assemblage with descriptive statistics and qualitative interpretation. Specifically, we build upon our report of descriptive statistical analyses of the longitudinal cohort study Growing Up in New Zealand (GUiNZ) (Boyask et al. Citation2022). The GUiNZ study measures the physical, social, and cultural dimensions of over 6000 children in Aotearoa New Zealand. Correlational analysis of these secondary data provides a description of reading for enjoyment within a rough approximation of the complex arrangements of people and objects that make up the lives of young people. What we found of relevance was that while reading frequently was strongly associated with socio-economic and ethnicity factors, reading enjoyment is more evenly distributed, that is, enjoyment of reading is common. Some other kinds of experiences children have, like being active at home, taking part in the arts or being read to at an early age have associations with both enjoyment and frequency of reading. We think paying closer attention to reading affect has potential to impact upon the distribution of reading, making its spread more equitable.

While we summarise in this article some of the correlational associations found in the analysis of GUiNZ data, the main purpose of their inclusion is to provide a text for an overlaid interpretive analysis. Adding the further layer of analysis through an interpretive lens enables deeper contemplation that extends beyond the meaning of individual associations. While the correlational statistics are descriptive and cannot inform conclusive recommendations, in this article we consider the results from an interpretive perspective. What does an assemblage of relations between reading objects in its totality reveal about motivation for volitional reading and the sustenance of reading within classrooms?

Literature and context

Volitional reading in the literature

Volitional reading is a social phenomenon. Engagements with other people are known to be significant in motivating reading. While it is well established that early reading is affected by relations with parents, this appears to continue for older children (Klauda and Wigfield Citation2012) and young people (Wilhelm and Smith Citation2016). However, the social connections of older children broaden, so that peer relationships also assume importance in motivating volitional reading. In general, teacher activity in classrooms seems less important for motivating students’ recreational and academic autonomous reading than other people (De Naeghel and Van Keer Citation2013). Yet, some teachers in some classrooms are influential. In a study of exceptional teachers of reading, it was found that for children age 11, reading aloud, school culture, and teachers’ interest in reading were strategies that can encourage students’ autonomous reading motivation in the classroom (De Naeghel et al. Citation2014). Opportunities to read are afforded by a ‘multitude of nested relationships encompassing peers, school, family social networks, community connections, online environments and the wider media’ (Cummings et al. Citation2018, p. 105).

Sociological studies on reading for pleasure have been very important for challenging normative assumptions about children’s reading through its relationship with sociological positions such as class and gender (Sullivan and Brown Citation2015; Jerrim and Moss Citation2019; Scholes et al. Citation2021). Cognitive ability is not fixed, and evidence that differences in reading are socially produced opens possibilities for future intervention. However, for young people in Aotearoa New Zealand, the realisation in research that reading has sociological explanations has not contributed to better reading outcomes (McNaughton Citation2020). We think that when describing young people’s reading, social categorisations themselves risk becoming fixed and self-fulfilling prophecies (Boyask et al. Citation2009). A socio-material lens enables comprehending patterns in children and young people’s reading and their reading identities as mutable, contingent, affective, and relational.

As well as their social dimension, reading engagements are also afforded by material relations, affecting choices of reading texts, locality, and time for reading. Indeed, the relationships that motivate young people’s engagement with reading have both material and social dimensions. For example, while teachers generally have less influence over volitional reading, a deeper understanding of this phenomenon is arrived at through applying a critical literacy lens that recognises limits upon the material conditions of schooling (Gutiérrez Citation2008). School-based literacies are weak because they are ahistorical and privilege dominant values (Graff Citation2010). Older children whose chosen reading texts are not those valued in school environments may not even conceive of their out-of-school reading experiences as reading, and even define themselves as nonreaders (Cummings et al. Citation2018).

Our turn to affect theory comes from the recognition that there are many influences, both obvious and hidden, upon children’s volitional reading, and that our statistical analyses describe the ways different variables may be affecting one another. Relationships between reading objects (or the reading ‘things’ in assemblages) can be discerned through examining the quality and affective intensity of young people’s reading experiences. In our work, reading affect, drawing from affect theory (Massumi Citation2015), is defined as the intensity of experience within a sociality of reading. It is observed through affective concepts such as enjoyment, interest, confidence, boredom, motivation, and resistance; however, affect is not reducible to emotion (Johnson Citation2019). Affect ‘is the flow of intensities that catches things up, brings things together, breaks things apart, and can be expressed as possibility, momentum, and emerging directions of force’ (Boldt and Leander Citation2020, p. 518). Contemplation on the quality of relations between people, objects, and concepts leads us towards thinking of potential and new, sustainable configurations for reading.

Interpreting descriptive statistics on reading

Most of what is known about volitional reading in Aotearoa New Zealand comes from large scale research studies of young people’s reading from 8 to 15 years of age, including the international comparative studies of Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) and Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), and national study National Monitoring Study of Student Achievement (NMSSA). These studies show patterns in reading over time and have been used as indicators of quality in educational systems. While the studies continue to provide insight on reading, there is ongoing criticisms of their methodology, and PISA, for example, has been criticised for methodological ‘issues such as sample representativeness, non-response rates, population coverage and cross-cultural comparability’ (Zieger et al. Citation2022, p. 633). These studies are also very poor at attending to variations in culture, ways of being and systems of knowledge, recognition of which is of great importance in bi-cultural Aotearoa New Zealand. At very least, this suggests the need for new ways of generating insight on children’s reading.

In this article, we interpret the results of a correlational statistical analysis of longitudinal data through a socio-material lens. Our original study analysed secondary data obtained from the Growing Up in New Zealand (GUiNZ) study, which is the largest and most varied population study of children in Aotearoa New Zealand. While GUiNZ studies the children’s life course, its variables on reading are not consistent over time, so identify different kinds of patterns than the PISA and PIRLs longitudinal studies. Furthermore, reading-related variables form only a small part of its database. What we find in the GUiNZ database is the opportunity to examine two small insights on children’s reading in the light of many other social, cultural, psychological, and physical variables. Through correlational analysis, we can start to see how variables may affect one another.

Easily understandable descriptive statistics were originally adopted as a useful tool for the investigation of the data, with many predictor variables to be explored. Following standard statistical methodology, the relationships identified were descriptive, and not intended to be read as causal or even independent of other influences.

We examined reading enjoyment and frequency at age 8 (from child proxy reports by mothers) in the context of over 60 variables from throughout their life course. Our institutional ethics committee did not require an application since the data we received were fully anonymised. The bivariate analyses included contingency tables (where sensible, categorical variables were split to produce 2 × 2 contingency tables), Fisher’s exact tests, logistic regression (for the categorical variables with more than two groups such as ethnicity, high/med/low deprivation, ½/>2 adults, etc.), and plots. The odds ratio is used to indicate effect size.

We have interpreted these results using a socio-material interpretive framework (Fenwick et al. Citation2011) in a reflexive science paradigm (Burawoy Citation1998). Through viewing them through our socio-material lens, we seek an understanding more closely attuned to volitional reading as an affective mode of being (Stewart Citation2017). This form of analysis speaks to the Aotearoa New Zealand context, where volitional reading is found to be part of multimodal immersion and engagement with texts as children follow their interests across different media (Cummings et al. Citation2018), and Māori scholars have been reframing literacy using Mana-centric concepts that have affective qualities such as ‘Mana Motuhake (positive self-concept and a sense of embedded achievement), Mana Tū (tenacity and self-esteem), Mana Ūkaipō (belonging and connectedness to place)’ (Hetaraka, Meiklejohn-Whiu, et al. Citation2023, p. 63).

The socio-material analysis highlights relationality in children’s reading between children as readers, other people, and things at differing levels of proximity. This view of childhood extends commonly used ecological systems theory frameworks, such as Bronfenbrenner’s view of individual children located within ecological systems that are framed by contexts or localities (Neal and Neal Citation2013). In our analysis, we move away from a language of ecological systems to consider children located in assemblages that have material, spatial, temporal, and cultural characteristics (Fox and Alldred Citation2016). Variables are ‘things’ examined in relation to one another that ‘are taken to be gatherings [or assemblages] rather than existing as foundational objects with properties’ (Fenwick et al. Citation2011, p. 3, (parentheses added). The variables examined have categorical characteristics while concurrently perceived through their relationships in assemblages that describe children’s experiences of reading, 1) at home and with family and whānau,Footnote1 2) outside of home experiences (e.g., at school or community organisations), and 3) societal positions (e.g., gender, household income and ethnicity). In this article we focus upon the first two of these assemblages to consider affective relations in children’s reading at home and with family and whānau and outside of home within communities and social institutions.

Results on reading frequency and enjoyment

At the centre of the descriptive statistical analysis were two variables derived from the GUiNZ database: reading frequency and reading enjoyment. We originally examined these variables through univariate analyses, including tabulation and plots, and bivariate analyses of each outcome variable in association with predictor variables, seeing in the data meaningful ways to divide the response categories from both educational and statistical perspectives.

The categorical reading enjoyment variable was split into a binary variable by distinguishing between children who very much enjoy reading and all others. That made sense statistically, creating a binary variable that was very close to a 50% split, and educationally provided greater confidence that children in the study enjoy reading. If they did not fall in the very much enjoys category, the subsequent category was only somewhat enjoys reading. The reading enjoyment variable was the outcome variable used for other analyses related to enjoyment of reading.

With most readers falling in the most frequent category, it made sense statistically to divide the variable responses for reading frequency between those who read more than once per week and those who do not. This is the outcome variable used for subsequent analyses related to reading frequency. However, from an educational perspective, a child at age 8 years who reads frequently reads more often than only once per week (Silinskas et al. Citation2020) and we would have preferred a more fine-grained distinction in reading frequency.

Most children in the study at age 8 engaged in reading for pleasure more frequently than once per week. Their mothers also reported that about half of the children very much enjoyed reading for pleasure. The association between reading frequency and enjoyment suggested that the largest group of children both very much enjoy reading for pleasure and read for pleasure more than once per week. As children enjoy reading less than this, they tend to read less frequently ().

Table 1. Association between children’s reading frequency and enjoyment.

There is also a small group of children (n = 160) who were reported as not reading very often even though they very much enjoying reading. We sought in the data an explanation for why these children may not be reading as often, wondering if it indicated difficulties accessing reading material. The small sample size did not reveal much; these and other silences in our results are what drives us to look at the same problem from innovative or multiple perspectives. Our intention to examine reading enjoyment and frequency in relation to other people and things from the children’s environments meant that we were working in an exploratory and iterative way with many different variables. The variables were organised and grouped through our interpretive framework. The first depiction of the children’s reading assemblages is seen through tables of odds ratios ( and ).

Table 2. Summary of the odds of home and whānau experiences associated with reading frequency and enjoyment.

Table 3. Reading frequency and enjoyment in association with outside of home experiences.

Reading enjoyment and reading frequency at home

The first assemblage of associations summarised here were those between children’s experiences of reading and variables within their home and whānau environments. Through comparing the odds ratios of reading enjoyment and frequency with other variables from the home milieu we started to see some patterns emerging that describe children’s reading experiences within home environments and through engagement with whānau. summarises the comparisons of odds ratios.

There is a greater number of significant odds ratios for reading frequency than enjoyment. The home and whānau variables observed from throughout the children’s life course were more closely associated at age 8 with reading frequency than enjoying reading. There was more commonality in reading enjoyment. There were also differences in the nature of the variables that have significance to frequency of reading compared with enjoyment of reading. For example, how children spend their time from when they are very young onwards may have greater effect on reading frequency than enjoyment. Whereas the people in children’s home and whānau seemed to be associated with both more and less reading enjoyment at age 8.

Most mothers reported that their children at the age of 8 had an appropriate amount of time designated for free or unstructured play during a typical week. Out of the 315 children characterized as having too much playtime, only 112 (35.6%) were reported to fall into the higher reading enjoyment category. Surprisingly, this percentage was lower compared to the 442 children who were reported as not having enough playtime, among whom 213 (48.2%) very much enjoyed reading. Only half of the children with an excess of free time engaged in frequent reading, whereas three-quarters of those with just the right amount of or insufficient free time did.

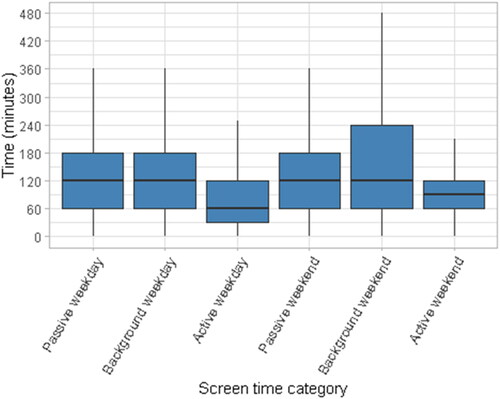

Mothers were asked about their children’s engagement and screen time, shown here as passive, background and active screen time: 1) watching television or other video (passive screen time); 2) with television on in the same room (background screen time); 3) doing activities and tasks on devices (active screen time). compares the different forms of screen time for a usual weekday and weekend day.

Figure 1. Number of minutes at age 8 of passive, background and active screen time on a usual weekday or weekend.

Higher passive screen time during weekdays was linked to reduced odds of both engaging in frequent reading [OR 0.48, 95% CI (0.4, 0.56)] and finding greater enjoyment in reading [OR 0.55, 95% CI (0.48, 0.63)].

Reading enjoyment and reading frequency and outside of home experiences

The next group of variables were assembled to understand the experiences children have outside of home. provides an overview of the connections between reading and some of the people and things children encountered beyond their home environment. The ‘things’ that represent children’s out-of-home experiences include education in early learning settings, use of libraries, engagement in school activities, and participation in organized extracurricular activity outside the home. Some variables were derived from the child’s own responses, while others reflect parental viewpoints.

Analysing both the child’s and parent’s perceptions of experiences beyond the home setting offers deeper insights into the cultural milieu that shapes a child’s reading habits. This examination sheds light on the congruence between home-based and external experiences, providing a valuable understanding of how a child’s engagement with reading develops within diverse environments. Notably, parental perspectives and attitudes regarding their children’s educational progress emerge as significant associations with children’s reading.

summarises relationships between reading frequency and enjoyment and predictor variables that refer to people and things within children’s networks outside of the home. The list includes variables that describe children’s engagement with early childhood education, libraries, schools, and organised activities experienced outside of the home. While some of the variables described the child’s own feelings and perceptions, others were the perceptions of parents. Examination of both child and parent views of outside of home experiences provides greater insight on the culture in which a child’s reading develops, including insight on alignment or variation between home and outside of home experiences. Parental views and attitudes towards their children’s learning and progress stand out in the results as associated with children’s relationships to reading, and especially notable was that the association between enjoyment and satisfaction with learning progress had one of the highest odds ratios in the study.

Discussion

In this section, we build arguments from the socio-material interpretation of the results for each of the two assemblages examined: home and outside of home.

Reading is something we do together at home

Greater enjoyment of reading seems closely linked with the culture of children’s homes and the people who make them up. In the correlational results in the prior section, there is a significant increase in odds of children enjoying reading when living in smaller households. This could be because children spend more time on their own. More than two adults [OR 0.78, 95% CI (0.67, 0.91)] or siblings [OR 0.8, 95% CI (0.7,0.91)] reduce the odds of reading enjoyment, and siblings also reduce the frequency of reading [OR 0.66, 95% CI (0.57, 0.76)]. A study investigating differences between intrinsic and extrinsically motivated reading found that less reading occurs in larger households; however, those in larger households who are frequent readers read more frequently, suggesting that larger families may share more reading materials or recommendations for reading texts (Suárez-Fernández and Boto-García Citation2019), or we speculated that it may be a means of escaping a busy household. Other studies show the importance of significant others to developing reading skill (Buckingham et al. Citation2014) and intrinsic motivation to read at early years (Clark and Rumbold Citation2006; Vanobbergen et al. Citation2009), yet other people also motivate and enthuse older children and young people to read (Strommen and Mates Citation2004; Clinton and Hattie Citation2013; Fletcher and Nicholas Citation2018). We found that while other people may be a distraction from reading, more adults in the house were associated with increased frequency of reading, and parents are particularly influential in raising the odds for both greater frequency and enjoyment of reading.

Parents are common to most children’s experience at home, and as primary care givers, obviously influential on children’s language development. Parental education is a characteristic often associated in other studies with reading. Sullivan and Brown (Citation2015) discovered that when examining reading vocabulary among 16-year-olds, parental education demonstrated a stronger correlation with linguistic fluency compared to parental material resources, sibling interactions, or other academic achievements like math performance. In our results, parents who had some tertiary education were associated with reading frequently and to a lesser extent, greater reading enjoyment at age 8, with mothers’ tertiary education increasing odds more than partners. We think this may be because overall mothers spend more time reading with their children. Children who enjoy reading more and read more often at age 8 also enjoyed being read to as a baby by their parents. Numbers of books in homes is a traditional measure of children’s literacy (Sullivan and Brown Citation2015). In our study, more books at home increases the odds of reading frequency [OR 2.29, 95% (2.0, 2.62)] and to a lesser extent, enjoyment [OR 1.51, 95% CI (1.34, 1.7)], which is consistent with other study findings. For lower secondary students in Poland, ‘the strongest predictor of not reading books is the size of a household’s and student’s library – as many as 22% of non-readers come from households with a minimum number of books (up to 10 books)’ (Zasacka and Bulkowski Citation2017, p. 86). Reading at home has both social and material qualities, and reading at home is motivated or demotivated as children and young people engage with other people and objects in reading relationships.

Reading as engagement

Volitional reading is associated with participation in other activities at home. In the results tables above, children who prefer to spend their time at home in quiet or inactive pursuits had higher odds of reading more frequently. Yet, children also had higher odds of reading more frequently when they were more often engaged in active play, and enjoyed reading if they were perceived by their mothers to not have enough play time. An interesting discovery in our results was a tentative link between reading enjoyment and enjoying exercise, which suggested an association between volitional reading and interest-based activity may extend to some very active pursuits and interests, thus broadening the view of who reads beyond stereotypes of quiet, physically inactive children. Children who frequently undertook homework or household chores—defined as more than once a week—had double the odds of reading frequently, indicating a positive relationship between these activities and habitual reading. This builds a picture of children engaging in volitional reading as well as being active at home and engaged in many kinds of activities.

While historical studies have shown that reading is not a passive process for children cognitively (Phillips and McNaughton Citation1990), an active mindset in general may be significant for motivating and sustaining reading activity.

We also looked at the technology use of children at age 8 since engagement with digital technology is a distraction from deep reading (Wolf Citation2018). There seems to be a connection in the level of active engagement in device use and reading in our results. An association emerged between inactive pursuits during free time and greater time spent on screen-based activities. This association implies that children who favour inactive pastimes might be more inclined to spend their time passively viewing screens rather than actively engaged in digital technology use. Conversely, children who exhibit equal inclinations toward both active and inactive pursuits tend to have lower screen time and higher odds of engaging in frequent reading while enjoying it more.

It may not be that reading takes you away from other things, but that doing other things can bring you closer towards reading. While the odds are higher for children who prefer and engage in quiet and less physical activity, we think the critical difference for more frequent reading may be balanced interests and engagement in a variety of unstructured and structured activities. Other literacy researchers are certainly examining the significance and use of active engagement and interest-based activity as a means to stimulate children and young people’s reading (Davey and Parkhill Citation2012; Traficante et al. Citation2017; Romero-González et al. Citation2023).

Reading for pleasure is something we do outside of school

Research on school aged children’s reading in Aotearoa New Zealand has tended to focus upon reading literacy as a construct of their schooling (Boyask et al. Citation2022). Until very recent curriculum reform (Ministry of Education Citation2023), educational policy has framed reading for pleasure as an at home activity that can support success at school. A strength of GUiNZ data is that it provided us with insight on children’s lives both inside and outside of formal education, including their reading, thus not framing children exclusively as school students or limiting purposes for reading to success at school.

The formal education variables come from the children’s own perceptions of school at age 8 and their parents’ perceptions of early childhood education and school throughout the data collection waves. These perceptions were the closest we could get from the database to observations of the children’s academic performance. In general, there is a small effect for reading at age 8 when parents perceived their children to be receiving good pre-reading support through early childhood education. There was a larger effect when they perceived their children to be making good progress at school. While earlier empirical studies were inconclusive on the effects of volitional reading on reading achievement (Taylor et al. Citation1990), over time a tentative picture has developed of relationships between reading motivation and achievement (Morgan and Fuchs Citation2007). This is consistent with the effects observed in the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study, where there has been a general trend of relationships between higher school performance and more reading for pleasure (Chamberlain with Essery Citation2020). Yet, declining reading enjoyment has been observed in samples of 8- and 12-year-old children who show evidence of overall higher reading achievement, leading the researchers to support Smith et al.’s conclusion that in schools:

We need to focus more strongly on ensuring that students see value and get pleasure out of their reading. Perhaps stronger efforts can be made to see that students get to read material that they see as being of interest to them and worthy of their efforts (Smith et al. Citation2012; p. 206).

Reading as engagement with the world outside of home and school

One of the most intriguing findings of our study was the effects of out of school activities on the odds of reading frequency and enjoyment. In general, children at age 8 who are involved in interest-based, secular, organised community activities and groups have higher odds of more frequent reading. Organised sports (both individual and team-based) or arts activities and trips to the library have similar associations, with odds ratios ranging between 1.96 and 1.57. Community group or club (e.g., Cubs, Brownies, or cultural group) [OR 1.4, 95% CI (1.2, 1.63)] activity also had a weaker but significant association with more frequent reading. These are some of the highest odds among our results. While these activities are associated with higher reading frequency, other community activities [including academic lessons (reading, maths, second language, etc.) or religious services or classes once a week or more] do not show this association.

There are more varied associations between children’s activity in the community and reading enjoyment. Engaging in arts-related activities shows an association with higher odds of enjoyment of reading [OR 1.65, 95% CI (1.47, 1.86)]. Similarly, participating in organised individual sports [OR 1.36, 95% CI (1.21, 1.53)] and visiting the library at the age of 6 [OR 1.35, 95% CI (1.19, 1.54)] are also linked with increased enjoyment of reading. However, there appears to be no noticeable association between deriving pleasure from reading and engagement with community groups or clubs, religious services or classes, organised team sports, or academic lessons. In a study of children aged 9 to 11 interests were followed across media and activities, including reading print and digital texts (Cummings et al. Citation2018). These interests were pursued in peer groups.

The majority of children reported that their friends shared the same interests as them. Shared interests have reciprocal influences and are a common way to develop peer relationships as well as mediating children’s development of interests and pursuit of activities (Cummings et al. Citation2018, p. 112).

Overall, this points to older children’s volitional reading being one of many activities in a multi-faceted life, and to some extent supports the thesis alluded to above that reading is associated with taking part in purposeful, interest-based activity with others. Engagement in interests such as arts and sports that are shared with other people may draw children and young people into reading rather than act as a distraction.

Conclusion

Children and young people’s volitional reading viewed through a socio-material lens highlights its interconnectedness, as new materialist studies ‘perceive humans (including feelings or cognitive responses) and materials (and the environment in which these materials are used) as inseparable’ (Kucirkova Citation2021, p.150). While reading in literacy education tends to focus upon the cognitive dimensions of reading such as decoding and comprehension, volitional reading refocuses attention on the affective qualities of reading. Focusing upon older children’s reading for pleasure, our study identified some affective relations between people and materials within lived experiences that may support and motivate more of young people’s volitional reading.

It is well known in literacy research that reading enjoyment develops in the relationships young people have had with others throughout their life course, especially adults (Cremin et al. CitationN.D.). In our study this was usually mothers, which may be because mothers are more frequently spending time reading with their children. Since other adults at home statistically had a positive effect on reading frequency, we see potential for other people from home or in whānau to also be involved in young people’s enjoyable encounters with reading.

Volitional reading is something we enjoy doing together at home. While the volitional reading of children and young people in Aotearoa New Zealand is known to be influenced by significant others, or reading together (Quigan et al. Citation2021; Oakden and Spee Citation2022), we have added italicised emphasis to the word ‘doing’ to indicate the importance also of engagement with reading and other people and objects that affect volitional reading. The children in the study who read more frequently are busy in other ways. They choose both active and quiet play at home. They do household chores and homework. They also spend less time passively watching screens preferring to use technology for activities and tasks. These findings hint at further possibilities for education to sustain reading.

We wonder about the potential of shared activities and interests to bring young people back to reading. Some of the biggest effects in our study on young people’s enjoyment of reading come from their activities outside of school. Involvement in organised arts and sports activities appear to have a positive influence upon reading. Historical work argued that children’s reading stimulates interest to develop the intellect (Gray Citation1924). From our findings, it seems interest-based engagement with certain kinds of objects may motivate and sustain reading relationships rather than act as a distraction that draws them apart. Young people who are engaged in purposeful, interest-based activities (such as arts and sports) that are shared with other people may be drawn into reading.

While we observed a relationship between reading and perceptions of school performance, our own and other studies results point away from enjoyment of school as a primary motivation for volitional reading. Volitional reading is something that may be motivated more by outside of school interests and encounters. If this is the case, we wonder why there is a difference between inside and outside school? Schools could adopt more of the characteristics of encounters that motivate reading outside of school. Bringing into schools more objects like those encountered outside of school and encouraging shared engagement with them has also potential for creating greater equity. This is an argument to increase the kinds of organised purposeful activities in school that are associated with reading (for example, visual art, music, sports, or chess) and the material resources that sustain them (including people who can enthuse others to engage in them). We can imagine more school programmes that are organised to enhance and draw upon affective relationships in reading, where passions and interests are shared, questions are raised, and curiosity sated through engagement in the sociality and materiality of volitional reading.

Data availability

Quantitative data analysed in the original study referred to in this article come from the Growing Up in New Zealand Study, reference: DA20_1009.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Whānau translates roughly to extended family in the indigenous language of Te Reo Māori, and is commonly used to describe the familial relations in which tamariki or Māori children are embedded.

References

- Boldt G, Leander K. 2020. Affect theory in reading research: imagining the radical difference. Read Psychol. 41(6):515–532. https://doi.org/10.1080/02702711.2020.1783137.

- Boyask R, Carter R, Waite S, Lawson H. 2009. Changing concepts of diversity: mapping relationships between policy and identity in English schools. In: Quinlivan K, Boyask R, Kaur B, editors. Educational enactments in a globalised world: Intercultural conversations. Rotterdam, Netherlands: Sense Publishers; p. 115–127.

- Boyask R, Harrington C, Milne J, Smith B. 2022. “Reading enjoyment” is ready for school: foregrounding affect and sociality in children’s reading for pleasure. NZ J Educ Stud. 58(1):169–182. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40841-022-00268-x.

- Boyask R, May R, Milne J, Jackson J, Harrington C, Hankin RLF, Hall D. 2022. Experiences of New Zealand children actively reading for pleasure. https://www.msd.govt.nz/about-msd-and-our-work/publications-resources/research/children-and-families-research-fund-report/experiences-of-new-zealand-children-actively- reading-for-pleasure.html

- Buckingham J, Beaman R, Wheldall K. 2014. Why poor children are more likely to become poor readers: the early years. Educ Rev. 66(4):428–446. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2013.795129.

- Burawoy M. 1998. The extended case method. Sociol Theory. 16(1):4–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/0735-2751.00040.

- Chamberlain M, with Essery R. (November 2020). PIRLS 2016: The importance of access to books and New Zealand students’ reading confidence. Educational Measurement and Assessment. Ministry of Education.

- Clark C, Rumbold K. 2006. Reading for pleasure: A research overview. London, UK: The National Literacy Trust.

- Clinton J, Hattie J. 2013. New Zealand students’ perceptions of parental involvement in learning and schooling. Asia Pacific J Educ. 33(3):324–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2013.786679.

- Cremin T, Hendry H, Chamberlain L, Hulston S. N.D. Approaches to reading and writing for pleasure: an executive summary of the research. https://cdn.ourfp.org/wp-content/uploads/20231212163945/Reading-and-Writing-for-Pleasure-REVIEW_04Dec-FINAL.pdf.

- Cummings S, McLaughlin T, Finch B. 2018. Examining preadolescent children’s engagement in out-of-school literacy and exploring opportunities for supporting literacy development. AJLL. 41(2):103–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03652011.

- Damaianti VS. 2017. Volitional strategies through metacognitive development in fostering reading motivation. Indonesian J Appl Linguist. 7(2):36. https://doi.org/10.17509/ijal.v7i2.8130.

- Davey R, Parkhill F. 2012. raising adolescent reading achievement: the use of sub-titled popular movies and high interest literacy activities. English in Aotearoa. 78:61–71.

- De Naeghel J, Van Keer H. 2013. The relation of student and class-level characterstics to primary school students’ autonomous reading motivation: a multi-level approach. J Res Read. 36(4):351–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9817.2013.12000.x.

- De Naeghel J, Van Keer H, Vanderlinde R. 2014. Strategies for promoting autonomous reading motivation: a multiple case study research in primary education. Frontline Learn Res. 3:83–101.

- Fenwick T, Edwards R, Sawchuk P. 2011. Emerging approaches to educational research: tracing the socio-material. Florence, South Carolina, United States: Taylor & Francis Group.

- Fletcher J, Nicholas K. 2018. What do parents in New Zealand perceive supports their 11- to 13-year-old young adolescent children in reading? Education 3-13. 46(2):237–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2016.1236828.

- Fox NJ, Alldred P. 2016. Sociology and the new materialism: theory, research, action. Los Angeles, California, United States: SAGE Publications, Limited.

- Graff JM. 2010. Countering narratives: teachers’ discourses about immigrants and their experiences within the realm of children’s and young adult literature. English Teach Pract Crit. 9(3):106–131.

- Gray W. 1924. The importance of intelligent silent reading. Elem School J. 24(5):348–356. https://doi.org/10.1086/455529.

- Gutiérrez K. 2008. Developing a sociocritical literacy in the third space. Read Res Q. 43(2):148–164. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.43.2.3.

- Hetaraka M, Meiklejohn-Whiu S, Webber M, Jesson R. 2023. Tiritiria: understanding Māori children as inherently and inherited-ly literate—Towards a conceptual position. N Z J Educ Stud. 58(1):59–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40841-023-00282-7.

- Jerrim J, Moss G. 2019. The link between fiction and teenagers’ reading skills: international evidence from the OECD PISA study. Br Educ Res J. 45(1):181–200. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3498.

- Johnson RA. 2019. Attending to wonder: an affective exploration of the purposes for reading with youth in secondary English classrooms. PhD Dissertation, Michigan State University.

- Klauda SL, Wigfield A. 2012. Relations of perceived parent and friend support for recreational reading with children’s reading motivations. J Lit Res. 44(1):3–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086296X11431158.

- Kucirkova N. 2021. Socio-material directions for developing empirical research on children’s e-reading: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of the literature across disciplines. J Early Child Lit. 21(1):148–174. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468798418824364.

- Kucirkova N, Cremin T. 2020. Children reading for pleasure in the digital age: mapping reader engagement. London, England; Thousand Oaks, California, United States: SAGE Publications, Limited.

- Marin MM, Lampatz A, Wandl M, Leder H. 2016. Berlyne revisited: evidence for the multifaceted nature of hedonic tone in the appreciation of paintings and music. Front Hum Neurosci. 10:536. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2016.00536.

- Massumi B. 2015. Politics of affect. Cambridge, England; Malden, Massachusetts, United States: Polity Press.

- McNaughton S. 2020. The literacy landscape in Aotearoa New Zealand: what we know, what needs fixing and what we should prioritise. Office of the Prime Minister’s Chief Science Advisor: Kaitohutohu Mātanga Pūtaiao Matua ki te Pirimia.

- Ministry of Education. 2023. English learning area: Ministry of Education, Retrieved from https://curriculumrefresh.education.govt.nz/english.

- Morgan PL, Fuchs D. 2007. Is there a bidirectional relationship between children’s reading skills and reading motivation? Except Child. 73(2):165–183. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440290707300203.

- Neal JW, Neal ZP. 2013. Nested or networked? Future directions for ecological systems theory. Soc Dev. 22(4):722–737. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12018.

- Neugebauer SR, Gilmour AF. 2020. The ups and downs of reading across content areas: the association between instruction and fluctuations in reading motivation. J Educ Psychol. 112(2):344–363. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000373.

- Oakden J, Spee K. 2022. Reading Together® Te Pānui Ngātahi: summary of evaluations and implementation exemplars. Pragmatica Limited. https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/topics/BES/reading-together-te-panui-ngatahi.

- OECD. 2021. 21st-century readers: developing literacy skills in a digital world. PISA. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/a83d84cb-en.

- Phillips G, McNaughton S. 1990. The practice of storybook reading to preschool children in mainstream New Zealand families. Read Res Q. 25(3):196. https://doi.org/10.2307/748002.

- Pulvirenti G, Gambino R, Sylvester T, Jacobs AM, Lüdtke J. 2020. The Foregrounding Assessment Matrix: an interface for qualitative-quantitative interdisciplinary research. ENTHYMEMA. (26), :261–284. https://doi.org/10.13130/2037-2426/14387.

- Quigan EK, Gaffney JS, Si’ilata R. 2021. Ēhara tāku toa i te toa takitahi, engari he toa takitini: the power of a collective. Kōtuitui. 16(2):283–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/1177083X.2021.1920434.

- Romero-González M, Lavigne-Cerván R, Gamboa-Ternero S, Rodríguez-Infante G, Juárez-Ruiz de Mier R, Romero-Pérez JF. 2023. Active Home Literacy Environment: parents’ and teachers’ expectations of its influence on affective relationships at home, reading performance, and reading motivation in children aged 6 to 8 years. Front Psychol. 14:1261662. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1261662.

- Rutherford L, Merga M, Singleton A. 2018. Influences on Australian adolescents’ recreational reading. AJLL. 41(1):44–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03652005.

- Scholes L, Spina N, Comber B. 2021. Disrupting the ‘boys don’t read’ discourse: primary school boys who love reading fiction. Br Educ Res J. 47(1):163–180. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3685.

- Silinskas G, Sénéchal M, Torppa M, Lerkkanen MK. 2020. Home literacy activities and children’s reading skills, independent reading, and interest in literacy activities from Kindergarten to Grade 2. Front Psychol. 11:1508. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01508.

- Smith JK, Smith LF, Gilmore A, Jameson M. 2012. Students’ self-perception of reading ability, enjoyment of reading and reading achievement. Learn Individ Differ. 22(2):202–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2011.04.010.

- Stewart K. 2017. In the world that affect proposed. Cult Anthropol. 32(2):192–198. https://doi.org/10.14506/ca32.2.03.

- Strommen LT, Mates BF. 2004. Learning to love reading: interviews with older children and teens. J Adolesc Adult Lit. 48(3):188–200. https://doi.org/10.1598/JAAL.48.3.1.

- Suárez-Fernández S, Boto-García D. 2019. Unraveling the effect of extrinsic reading on reading with intrinsic motivation. J Cult Econ. 43(4):579–605. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-019-09361-4.

- Sullivan A, Brown M. 2015. Reading for pleasure and progress in vocabulary and mathematics. Br Educ Res J. 41(6):971–991. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3180.

- Taylor BM, Frye BJ, Maruyama GM. 1990. Time spent reading and reading growth. Am Educ Res J. 27(2):351–362. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312027002351.

- Traficante D, Andolfi V, Wolf M. 2017. Literacy abilities and well-being in children: findings from the application of EUREKA, the Italian adaptation of the RAVE-O Program. Form@re - Open Journal per La Formazione in Rete. 17(2):12–38. https://doi.org/10.13128/formare-21015.

- Vanobbergen B, Daems M, Tilburg S. 2009. Bookbabies, their parents and the library: an evaluation of a Flemish reading programme in families with young children. Educ Rev. 61(3):277–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131910903045922.

- Wilhelm J, Smith M. 2016. The power of pleasure reading: what we can learn from the secret reading lives of teens. Engl J. 105(6):25–30. https://doi.org/10.58680/ej201628647.

- Wolf M. 2018. Reader, come home: the reading brain in a digital world. New York, United States: HarperCollins Publishers. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/aut/detail.action?docID=29434316.

- Wylie C. 2004. Twelve years old & competent: the fifth stage of the Competent Children project – a summary of the main findings, NZCER. https://www.nzcer.org.nz/research/publications/twelve-years-old-and-competent.

- Zasacka Z, Bulkowski K. 2017. Reading engagement and school achievement of lower secondary school students. Edukacja. 141(2):78–99. https://doi.org/10.24131/3724.170205.

- Zieger LR, Jerrim J, Anders J, Shure N. 2022. Conditioning: how background variables can influence PISA scores. Assess Educ. 29(6):632–652. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2022.2118665.