ABSTRACT

This article sets out key findings of an interdisciplinary Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) funded project that uses Long Live Southbank’s (LLSB) successful campaign to retain London’s Southbank Undercroft for subcultural use – skateboarding, BMXing, graffiti art, etc. – as a case study to generate discussions about young people’s experiences and engagements with (sub)cultural heritage and political activism. At the heart of this inquiry is the perceived contradiction between the communicative practices of subcultures and social protest movements: the former typically understood to be internally oriented and marked by strong boundary maintenance, and the latter, to be successful, to be externally oriented to a diverse range of publics. In explaining the skaters/campaigner’s negotiation of this contradiction, we look to the inclusive and everyday concepts of ‘inhabitant knowledge’ [Ingold, T., Citation2000. The perception of the environment: essays in livelihood, dwelling and skill. London: Routledge], ‘vernacular creativity’ [Burgess, J., 2009. Remediating vernacular creativity: photography and cultural citizenship in the Flickr photosharing network. In: T. Edensor, D. Leslie, S. Millington, and N. Rantisi, eds. Spaces of vernacular creativity: rethinking the cultural economy. London: Routledge, 116–126] and ‘affective intelligence’ [Van Zoonen, L., 2004. Imagining the fan democracy. European journal of communication, 19 (1), 39–52]. In eschewing the exclusionary and contestatory language of (post)subcultural and spatial theories, this article proposes new frameworks for thinking about the political nature of young people’s bodily knowledge and experiences, and the implications of this for the communication of (sub)cultural value.

The Southbank Centre sits on a part of the River Thames that was developed for the Festival of Britain in 1951. The Undercroft which lies beneath the Southbank Centre was ‘left over’ space (Participants 1 and 2) and has, over the years, been used to park cars, store bins and to shelter the homeless. It was, in the words of the skaters, ‘space that nobody wanted’ (Participant 1) that was quickly discovered to be ‘absolutely perfect’ for street-skating (Participant 9) and, as a result, has been used by successive generations of skaters since 1973. As the commercial value of the land increased, the decision was taken in 2013 to remove the skaters from the site in order to open retail units with the potential to fund the Southbank Centre’s ambitious redevelopment programme (Long Live Southbank (LLSB) Citation2014). The Southbank Centre was mindful of the skater community and planned to build a new purpose-built skate park a few hundred metres down the river under Hungerford Bridge. However, their offer was rejected by many of the skaters, who nimbly put together an online and offline campaign, LLSB, which articulated to both policymakers and the wider public the value of the cultural practices which took place in the Undercroft. The tagline of LLSB’s ‘Dear Jude’ (Citation2013) YouTube film ‘Look at What We Made’ (see ) succinctly captures the complex interweaving of tangible and intangible heritage to which the skaters laid claim: they, not the Festival Wing’s Brutalist architects, brought this ‘found space’ (Participant 11) into existence through their usage.

Figure 1. LLSB’s ‘Dear Jude’ (Citation2013) video highlights the complex interweaving of tangible and intangible heritage.

We have explored elsewhere how the concept of ‘found space’, central to the LLSB’s claims and campaign, necessitates a reconceptualizing of authenticity such that it recognizes the felt experience and emotions generated by individual and collective users of space. Acknowledging and authenticating the experiences and emotional attachments of the skaters is a controversial and contested area of heritage practice within an English system that does not recognize intangible heritage in the way that many of the international charters and declarations do (UNESCO Citation2003). In that article, for the International Journal of Heritage Studies, we suggested that the Undercroft calls for an extension of even these frameworks in recognizing not just the experiences but also the expertise of ‘citizen experts’ such as the skateboarders involved in the LLSB campaign (Madgin et al. Citation2018).

In this article, we want to take up where that article left off, and explore how the attachments, experiences and expertise of this distinct ‘subcultural’ community were communicated and translated within the LLSB’s ‘political’ campaign. At the heart of this inquiry is the perceived contradiction between the communicative practices of subcultures and social protest movements: the former typically understood to be internally oriented and marked by ‘strong boundary maintenance’ (Hodkinson Citation2003), and the latter, to be successful, to be externally oriented to a diverse range of publics (Fraser Citation1991). In explaining the skaters/campaigners’ negotiation of this contradiction, we look to the inclusive and everyday concepts of ‘inhabitant knowledge’ (Ingold Citation2000), ‘vernacular creativity’ (Burgess Citation2009) and ‘affective intelligence’ (Van Zoonen Citation2004). In eschewing the exclusionary and contestatory language of (post)subcultural and spatial theories, this article proposes new frameworks for thinking about the political nature of young people’s bodily knowledge and experiences, and the implications of this for the communication of (sub)cultural value. In short, the three sections are shaped around three fundamental questions: how did and do the skaters feel about the space, how did they communicate these attachments and experiences, and to what extent were they heard?

Methods

In order to analyse this apparent contradiction, our Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) funded research project brought together a range of expertise from diverse fields: from social movement studies, (sub)cultural studies, town planning and heritage studies. Whilst members of the research team brought very different bodies of theoretical knowledge to the project, we shared a broadly social constructivist epistemological position and this underpinned our shared methodological approach.

We gathered together an archive of online and offline materials both from mainstream and alternative sources. These were used to formulate the topic guides for 25 semi-structured interviews. These included a series of walking interviews with individuals who were directly involved with the campaign, and a series of oral history interviews with an older generation of skaters who no longer skated the Undercroft. Finally, we interviewed a wide range of individuals who are involved in different capacities with the construction of heritage policy and planning decisions. Interviewees were recruited through snowball sampling. All the interviews were transcribed and analysed thematically by individual members of the research team. We then compared our findings collectively. Whilst the reliance on interviews with skaters, campaigners and policymakers directly involved with the conflict over the future of the Undercroft limits the range of voices available for analysis, it has enabled us to develop a real depth of understanding. Because of the focus of this article, we draw heavily on the campaigning side of the interviews, as well as analysing the online and offline campaign materials they created and circulated.

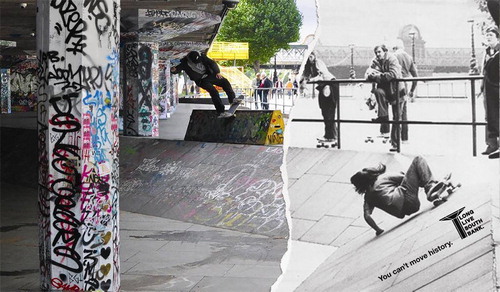

The research team also wanted to show the experiences and emotions of the Undercroft community, and the ways in which the skaters interacted with the space, to a range of different audiences. We worked in collaboration with Paul Richards from BrazenBunch, and a long-time Southbank skater and filmmaker Winstan Whitter, to produce a 20-minute film entitled You Can’t Move History (Citation2016) that could convey the experiences of skating at the Undercroft. The film is designed to allow a sensorial engagement with skating to be experienced as it conveys the sights, sounds, and uses of the space, and was first screened for an audience of arts and heritage policymakers (including the Director of Policy and Planning at the Southbank Centre). As such, it can be read as an intervention which helped the Southbank Centre recognize the ‘blind spot’ they had in relation to the Undercroft (Participant 16). Since then the film has been awarded the ‘Best Research Film, 2016’ in the AHRC’s ‘Research in Film Awards’ and is designed to act as a companion to this paper. All participants have been anonymized in the paper except where their words are spoken within the accompanying film. To watch the 22-minute film, please see https://vimeo.com/146671695.

The Undercroft as subcultural space

In this section, we begin by mapping some of the current approaches to understanding skateboarding via subcultural, post-subcultural and spatial theory. It makes a case for moving beyond the limits of these previous studies of skateboarding and other subcultures, in shifting from an exclusionary and contestatory language of ‘subcultural capital’ (Thornton Citation1996, Kahn-Harris Citation2007, Atencio et al. Citation2009, Dupont Citation2014) and ‘spatial tactics’ of resistance (de Certeau Citation1984, Borden Citation1998, Citation2003, Chiu Citation2009), to a more inclusive and everyday language of ‘inhabitant knowledge’ (Ingold Citation2000) and a ‘politics of bodily knowledge and experience’ (Moores Citation2012). We follow Shaun Moores (Citation2012, Citation2015) in this regard, looking to non-representational theories to assist in understanding both the skateboarder’s attachments to the Undercroft – grounded in the everyday, sensual experiences of inhabiting rather than spectacular, symbolic acts of resistance – and their successful communication of the skate spot’s primarily lived rather than representational value.

Within sociological and cultural studies of skateboarding, street-skating has been framed through two dominant theoretical frameworks: a focus on skater’s transgressive uses of space often via De Certeau and Lefebvre (Borden Citation1998, Citation2003, Chiu Citation2009); and a focus on the communal and contested relationships between skaters and mainstream culture via subculture and post-subculture literature (Brake Citation1985, Beal Citation1996, Dupont Citation2014). These studies tend to be favourable – at times utopian – about the counterhegemonic ‘tactics’ employed by skaters to ‘win back space’ (although following Birmingham’s Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies’ subcultural lead [Hall and Jefferson Citation1975] mostly symbolic space) from dominant commercial culture. More recently, ethnographic research has highlighted the mainstream-subcultural distinction underlying these analyses to be overstated and oversimplified. Drawing particularly on Sarah Thornton’s (Citation1996) reworking of Bourdieu (Citation1984) for the early 1990s club culture scene, recent research has characterized the world of skateboarding as hierarchically divided, with elite skaters distinguishing themselves not only from the ‘mainstream’ but also one another – particularly across generational and gendered lines – through their assertion of social and subcultural capital (Atencio et al. Citation2009, Dupont Citation2014).

These studies raise a number of questions for the study of contestation for and within the Southbank site. In particular, they provoke an inquiry into the extent to which a subcultural lexicon – both as theoretical framework and as situated argot – applies to how the Undercroft skaters and campaigners understand and articulate their connections to each other and to their space. Through their chosen verbal and visual vernaculars, LLSB clearly constructed their campaign as resistance to mainstream, corporate culture, but in a way that embraced wider public and policy concerns around preservation and gentrification. In addition, whilst the campaign evidenced its argument for maintaining the Undercroft through a unique visual and discursive language derived from skate media within its online spaces, it was at pains to be inclusive with regard to more subculturally naïve or inexperienced actors, highlighting the Undercroft as a welcoming space for all classes, ages, genders, and ethnicities, where novice and expert co-existed harmoniously (LLSB Citation2014). LLSB’s foregrounding of inclusivity can be understood, at least in part, as a response to the South Bank Centre’s attempts to delegitimize their campaign by characterizing the Undercroft community as ‘just white, just men, just middleclass’ (Paul).

Our empirical and historical research exposed this claim as reductive but did highlight ongoing limitations and contestations with regard to gendered power relations within the Undercroft site. The current and ex-skaters we interviewed were from a range of racial, ethnic and classed backgrounds, but the gendered makeup of our sample (gathered in collaboration with the Undercroft campaigners and skaters) was almost entirely male. The oral histories with older (ex)skaters stressed that the Undercroft was historically ‘almost exclusively male, 99.9%’, and that the culture could be a ‘bit macho sometimes’ (Participant 9), but that ‘one of the great changes that’s happened in skating over the last decade, which I find good to see, is there are far more women skating than there were’ (Participant 8). This was seen by older skaters to have filtered into the gendered makeup of the Undercroft community (Participant 9). Ethnographic observation and responses from our interviewees suggest that in recent years there has been a marked increase in female usage, with, in particular, an emergent generation of female teens currently skating the spot. Unfortunately, these skaters fell outside our criteria for interviewing as they were under 18. Despite these recent positive developments, gender continues to be a key factor structuring the power relations of the Undercroft, but not in a straightforward fashion.

An interview we conducted with a female photographer who used to regularly skate the Undercroft in the late 1990s alongside a ‘core group of other females’ (Jenna), indicated some correlation with the recent scholarship on gendered power relations and spatial distinctions in skating. Atencio et al.’s (Citation2009) research suggests that street-skating and its associated media constructs and circulates a ‘masculine habitus’ associated with risk-taking and technical prowess that serves to exclude women and mark their involvement as inauthentic. Our interviewee explained that for her female skate gang, it was the structural changes to the ‘feel’ of the space enacted by the South Bank Centre – in reducing the space to a third of the size – that served to exclude women, not the inherent male dominance or machismo. She explained: ‘It’s such a small area now, with the barriers, basically inviting people to come and watch the skateboarding, and I think you know sometimes that can put the women off. It’s not so much the skateboarders itself, but more just how the environment feels’ (Jenna). She highlights the spatial changes as instigating this shift in gendered usage but also suggests that the shift in power relations that the barrier and reduction of the space created was experienced differently through the male habitus within the Undercroft. These experiential attachments – and the violence enacted by the ‘vandalism’ (Participant 9) of both the South Bank Centre and other users – are key to the spatial connections that interviewees reported across gendered and generational divides, though in divergent ways.

We identified clear generational distinctions in how older and younger skaters communicated about and within the Undercroft space. In the oral histories we conducted, the older generation of (ex)skaters expressed a ‘subcultural’ positioning to the space, conveying nostalgia for an authentic, underground experience that had been lost. The older skaters simultaneously bemoaned and lamented the ‘dark ages’ period in the late 1970s to early 1980s when skateboarding became less popular and so a more exclusive and committed community skated the Undercroft. One of the oral histories explicitly connected that era’s core group of regulars to the subcultural capital circulated within underground music subcultures:

I mean there was a strong element, I think, during the dark era in particular of being into something that other people weren’t into, that sort of obscure knowledge, I’m into this obscure band that nobody else has ever heard of. And there’s only five of us in the entire planet, only two copies of this record ever released! That level. (Participant 8)

These familial connections, however, were explicitly and repeatedly foregrounded in the discourse used by the current Undercroft skaters, with the terms ‘family’ (Participants 2 and 3), ‘home’ (Participant 2, 3 and 13), and ‘mother’s womb’ (Participant 4) used to describe the community and its connection. For example, one of the skaters stated, reflected, and then substantiated his selection of the term ‘home’ to capture the sense of belonging and nurturing the Undercroft provoked for him: ‘I dunno, it’s home man. It’s home for a lot of people. And not in the sense of like somewhere you live, but as where you feel comfortable’ (Grant).

As Livingstone points out the notion of ‘home’ has historically been associated with the private rather than the public sphere (citing Williams Citation1983). However, there is a body of work which seeks to examine the political potential inherent in familial spaces. Dahlgren, for example, describes such spaces as ‘a reservoir of the pre-or non-political that becomes actualized at particular moments when politics arise’ (Citation2003, p. 155). Similarly, Van Zoonen makes a connection between the activities of leisure-based fan communities and participating publics arguing that both ‘can be seen as provoking the “affective intelligence” that is vital to keep political involvement and activity going’ (Citation2004, p. 39) beyond the confines of ‘home’ and ‘family’. Consequently the skaters identification of the Undercroft as ‘home’ does not preclude the formation of a more publicly orientated community, indeed it could be read as a precondition of its formation creating spaces characterized by ‘early expressions of interest, explorations of experience, tentative trying out of view points’ (Livingstone Citation2005, p. 28).

The idea of subcultures operating as symbolic family structures – even spaces to work through unresolved Oedipal tensions – goes back to the Chicago School in the interwar years and is central to the Birmingham School’s theorizations of post-war subcultures. But the way in which the skaters marshal a familial discourse goes way beyond these theoretical equivalences. For example, one of the skaters explained that the extra-familial connections within the Southbank community had facilitated his reconnection and resolution of issues with his estranged family. He explains:

You know and I’m sorting things out that I was supposed to sort out a long time ago, like things like relationships with my family […] I’ve got a feeling from being here, when we had such a big you know community here of people coming together. (Participant 4)

Within the interviews, the current Undercroft community adopted a highly emotive and inclusive language to discuss their attachments to the space, rather than the exclusionary argot or subcultural capital more usually associated with internal subcultural communication. This emotional register was tied very much to an experiential sense of more universalist values of ‘feeling’ and ‘belonging’, but one built up through individual and collective usage of the space over time. Setha Low’s conception of ‘embodied space [as] the location where human experience and consciousness take on material and spatial form’ (Citation2003, p. 10) ran through many of our interviews. So, for example, one of the skaters who was in charge of the online campaign said:

It’s integrated with my muscle memory, you know the things I feel. And I can feel skating there when I’m miles away. And I can come to places that are similar and I’m instantly reminded of it. It’s like an imprint on my psyche. It’s very special to me. And anyone who’s ever skated here. Just the way it sounds. People can tell you exactly the way it sounds. I could hear a thousand different sounds. Nowhere sounds like Southbank. That’s it. (Jason)

No, I just remember as it a space and an atmosphere, I know exactly … I can remember the space exactly as it existed in its entirety, because I traversed it so many times, but it’s just the atmosphere of it and the noise that comes with those kinds of places, the way the noise reverberates around in that enclosed … with that low ceiling. (Participant 9)

The skaters we interviewed shared a skating style that has evolved as a result of the limited space within the Undercroft which requires skaters to build the speed required to do tricks in two rather than three pushes. As one skater put it, the Undercroft ‘breeds a certain style as well, like you can always tell here who is local, ‘cause you can tell they are skating the Southbank style’ (Louis). Whilst the recognition of this ‘style’ clearly requires a high degree of shared inhabitant knowledge, it also recognizes the presence – in principle as well as in practice – of those who ‘aren’t locals here’ (Louis). In doing so the skate community implicitly acknowledges the ‘relation of inclusion/exclusion’ (Dahlberg Citation2007, p. 835) which underpins many of the inhabitants’ connections in the Undercroft. However, it does so whilst also implicitly acknowledging the potential for ‘association’ (Mouffe Citation2005, p. 20) with non-locals both within and beyond the Undercroft.

Ingold explains that it is ‘the ability to situate one’s current position within the historical context of journeys previously made – journeys to, from and around places – that distinguishes the countryman from the stranger’ (Ingold Citation2000, p. 219). The above account of breeding localness – the ‘Southbank style’ – through retreading and revising familiar ‘lines’ fits Ingold’s distinction between the ‘countryman’ and ‘stranger’, but also points to more spatially and temporally complex processes. Throughout their interviews, the younger generation of skaters we spoke to were at pains to highlight the diversity/inclusivity of the Undercroft as both a material space and a subcultural community. Even the older skaters, whose accounts of the Undercroft had a tendency to slip into a ‘celebration of the ghetto’ (Sennett cited in Calhoun Citation1998, p. 388) were eager to point out the significance of the Undercroft as the focal point and essential networking ‘hub’ (Participants 1, 2, 7 and 11) which spread out across the country. This was summed up by one of the older skaters who said:

You didn’t just skate there all day long, you’d meet there, have a little skate while you’re waiting for everyone and then say, ‘Right, we’re going to go … We’d go to Glasgow and skate up there and go skate Bury and Manchester, Birmingham, but we’d meet at Southbank and go. So, there’s always that space you come back to. (Participant 1)

Furthermore, and equally significantly, non-locals were not the only strangers to be found in the Undercroft. The ‘sociability’ of skating (Woolley and Johns Citation2001) enables skaters to participate in communal interactions even when they are not skating, or indeed when the practice of skating had been rendered impossible. Thus, for example, one of the older skaters described the way in which even in the ‘dark ages’ the community would congregate in the space ‘sitting on the walls that aren’t there now … spending more time moaning about the state of the world, their particular world, than skating’ (Participant 1). Time spent beyond the board ‘chatting, eating … and watching others skate’ (Jenson et al. Citation2012, p. 347) has the potential to include non-skating friends including those whose place within the skating community is secured by a distinct but closely related form of inhabitant knowledge – the ability to mediate tricks. In the following section, we will explore the role of mediation in the constitution of the Undercroft, and the resultant (re)use of media within the LLSB campaign as a method of mobilizing the public and decision-makers through communication of the skaters’ bodily understandings and inhabitant knowledge.

The Undercroft as mediated space

In this section, we use the concept of ‘vernacular creativity’ (Burgess Citation2009) to understand the coproducing social practices of skateboarding and filmmaking that emerge and evolve in the Undercroft, and their resultant relatability beyond that specific social, temporal and geographical context. In moving on to discuss the LLSB campaign, we highlight how its language and visual imagery sought to translate the bodily understandings and inhabitant knowledge of the skaters to ‘strangers’ encountering their message both within the physical space of the Undercroft and the media environments of YouTube and social media platforms. We argue that the LLSB campaign’s foregrounding of habitual practices and social interactions connect the Undercroft to a ‘body politics’ of the ordinary and every day that set it apart from the oft-perceived, elitist and exclusionary practices of both official cultural institutions (including those sharing the Southbank site) and subcultural groups (Thornton Citation1996).

Most of the skaters highlight the communal retreading of paths across generations as where the heritage value of the Undercroft is located, as one skater explains: ‘The journey is what matters […] the ongoing process is what matters, the evolution of it, you know’ (Domas). And whilst the LLSB campaign clearly makes reference to the tangible space of the Undercroft – hence the tagline ‘You Can’t Move History’ – its significance emanates from the collective reinscribing of that space through its use rather than specific historical or architectural factors. As one skater and campaigner explains:

You can see the history in the space. In the stones themselves there’s marks of tricks that people have done that nobody even remembers anymore, but that somebody might have saw, that never left them, that’s the kind of place it is really. (Jason)

[…] that is a part of a language that I think the younger guys have built up which I think is … I’m not denigrating it in any way, I think it’s fantastic, but I think they’ve been very aware that there’s been this great arc of time that they’ve been able to capitalise on, whereas I think for my generation it was just living in the moment in a sense and there was no sense of the past, there was no recorded past like there is now, there’s no way that these guys could go on and look online and find loads of pictures of them from years ago. (Participant 9)

Over the years analogue photographs, hand-held video cameras and mobile phones have all made the Undercroft accessible to locals, non-locals and non-skaters beyond its walls. This is not, of course, a new phenomenon. However, the ease of digitization, curation and circulation of analogue skate media alongside newly captured digital footage has intensified a wider sense of (mediated) accessibility and historical continuity (Garde-Hansen Citation2011). Moreover, the movement of images through the skate community expands the ‘constellation’ of individuals who can collectively remember the Undercroft in its many incarnations (Pentzold and Sommer Citation2011, p. 74). In this way, the mediation of the Undercroft extends the spaces in which the skate community can reflect upon the development of their attachments, experiences and expertise over time and in doing so validates their claim to space.

This mediation of the Undercroft facilitated a ‘tentative trying out of view points’ (Livingstone Citation2005, p. 28) which enabled the skate community – both current and former – to develop a stronger sense of collective memory. The contingent and non-linear sense of that memory might go some way to explaining what one of the current skaters described as ‘this whole generational paradigm, paradox, where it becomes the younger people touting about history and the older people talking about a compromise’ (Jason). For the older skaters, their presentist experiences of the Undercroft (‘I think for my generation it was just living in the moment’) carried over into their initial feelings about the campaign – that their space and their moment had been lost so why not take the offer of a new skate park for a new generation. The younger skaters feeling of generational inheritance – whether arising from the aforementioned remediations of the Undercroft’s ‘recorded past’ or the demands of improvising a preservation campaign, or both – became the central campaign message.

The significance of skate videos and photographs – both commercially and non-commercially produced and circulated – was a constant across generations of skaters. The connection between skating and filming, in particular, is one which has been explored by commentators in this field (Borden Citation1998, Jenson et al. Citation2012). Many typographies of skate culture place the filmmaker at the heart of the community alongside the skater and BMXer (Dupont Citation2014, p. 564). Here we will draw upon the concept of ‘vernacular creativity’ to understand LLSB’s strategies for ‘translating the feeling into something that people who don’t skate can understand’ (Henry), which was extremely successful with the wider public, but was (initially) unsuccessful with the Southbank Centre.

Almost all the Undercroft skaters (particularly those not originally from London) foregrounded the circulation of historic and contemporary images and videos in magazines, videos and online platforms as how they initially came to understand the Undercroft temporally as well as spatially. One skater, originally from Mainland Europe, explained that his first experience of the Undercroft was when it was included as a level in the PlayStation Tony Hawk Pro Skater 4 video game. He explains: ‘[…] that was the first time I heard about it or seen it, you know, skated, virtually skated, skateboarded here, you know!’ (Domas). This virtual ‘wayfinding’ experience created not only an initial cognitive map but also shaped future embodied experiences of the Undercroft. He continues that on moving to London: ‘I felt the first time I came here, I felt like I was in that video game, I’m you know Tony Hawk Pro Skater! Aw, this bit was there, you know’ (Domas). The physical rupture of migration was offset by the continuity in feeling of inhabiting the Undercroft across geographical and digital/physical boundaries.

Skate media – particular skate magazines and videos – are central to skate culture and connect ‘locals’ with other skaters and skate spots elsewhere. This was evidenced by the way in which most of the interviewee’s Undercroft origin stories foregrounded the role of both mainstream and underground media in shaping their identities, attachments and experiences of skate spots like the Undercroft. As one skater who grew up in the New Forest explained:

Well, the elements of the Undercroft that are meaningful to me, in the first instance, was the things that I saw in magazines, because we were just kids then, and when we got hold of skateboarding magazines which were quite difficult to get, and then there was these really beautiful photographs that were shot with a fish eye lens, so all the dimensions were kind of warped, so places like this just look incredible in that format. (Joey)

You don’t love it any less because you’re the guy who only takes pictures, because you realise that you’re not going to reach the kind of skill level you want but you love it, you can hang out with the people who are amazing if you take good pictures of them. And you might give those pictures to another friend of yours who also like makes magazines or runs a blog or … it’s just … it’s fantastic like that. (Participant 9)

In Jean Burgess’ terms, skating and filming are converging modes of ‘vernacular creativity’ that emerge from everyday practices and spaces, that are communally rather than individually produced, and are predominantly socially rather than economically productive. Burgess explains, vernacular creativity operates outside the ‘institutions or cultural value systems of high culture or the commercial popular media, and yet draws on and is periodically appropriated by these other systems in dynamic and productive ways’ (Citation2009, p. 116). Whilst the habitual and material (sub)cultural practices that emerged and evolved within the Undercroft are associated with a specific temporal, social and geographical context, they are not elite or exclusionary in the way that the creativity of official art worlds and cultural institutions (including many on the Southbank site) are often perceived to be (Becker Citation1982, Bourdieu Citation1993). A key aspect of the relatability and translatability of the LLSB campaign was the non-elite and non-institutional nature of its message: its commonness. Edensor et al. state that vernacular creativity ‘possesses the power to transform space and everyday lives of ordinary people to reveal and illuminate the mundane as a site of assurance, resistance, affect and potentialities’ (Citation2009, p. 10). Whether walking past and pausing to watch skaters performing tricks on the Undercroft banks and obstacles, or watching this vernacular creativity remediated via a YouTube video, ‘strangers’ are invited to pass through a material and social environment that feels simultaneously ordinary and familiar, and spectacular and special (Silverstone Citation2002). Moreover, while this engagement is not in itself political, it can be read as being pre-political (Dahlgren Citation2003) in so far as it addresses the passer-by as interested and potentially participatory.

LLSB’s campaign film ‘The Bigger Picture’ (Citation2013) (which has had almost 100,000 views on YouTube alone) makes the beauty of the everyday explicit in the opening of the film as a long, elegant tracking shot, running in reverse with the camera at foot level, follows members of the public walking past Undercroft then doubles back to follow skaters following the same paths and lines. This intro makes an equivalence between the two forms of ‘being in the world’ – locals and strangers on a shared journey – whilst grounding skating as a pedestrian and everyday practice. The everyday vernacular of the skaters in juxtaposition to the elitist and exploitative vernacular of the Southbank Centre is made even more explicit in LLSB’s YouTube film ‘Consumerism over Culture’ (Citation2014) which edits between footage of skaters and market stalls on the Southbank, and combines interviews with skaters and market traders advocating for the value of the Undercroft.

Visually and within the interviews, a symbiotic relationship is drawn between the organic skate community and local economy of the Southbank Food Market, and the joint threat of the ‘fancy restaurants’ planned to take their place. One of the food market’s stall holders reiterates the testimonies from our interviews, in locating place in embodied practices and habitual retreading of paths, explaining:

When you come past the sound of the screech of the skateboard and, you know what I mean, the sound of the wheels hitting the concrete, its great and you do know the sounds … them sounds when you hear them they will make you feel yeah I’m here, I can hear it, know what I mean.

In fact, LLSB converted its vernacular creativity into commercial activity in order to fund the campaign. This involved turning the intangible and non-representational – the feeling of the Undercroft – into the tangible and representational – an identifiable product that captured the spirit of the Undercroft semiotically. Emblazoned on t-shirts, hoodies, stickers, even its own exclusive range of Adidas sportswear, the LLSB logo of a monochrome image of one of the Undercroft’s concrete pillars transcended its material referent to become not only a good funds generator but also a globally recognized symbol (see ). The symbol, though indexically referencing the materiality of the space was seen to be authentic (‘people seem to really respect the logo’ [Participant 11]) because it emerged from the inhabitant knowledge of a ‘skater from there’ articulating his ‘interpretation of that space’ (Participant 11).

This articulation of inhabitant knowledge into a recognizable visual language for strangers was a vital component of the more explicitly campaigning LLSB videos. Whilst some featuring well-known skaters (within the skate community) doing tricks were clearly aimed at a niche audience, videos aimed at a decision-makers, stake holders and the wider public combined the aesthetics and DIY ethics of skate media with more recognizable (art) cinema technique. For example, the ‘Dear Jude’ video – addressed to the Southbank Centre’s then artistic director Jude Kelly – employed slow motion and montage editing and focused far less on tricks and more on the faces of the young skaters and the reactions of the public spectating and signing petitions (see ). This balletic film captures the Undercroft’s community and creative agency but also extends it to the wider public. These YouTube videos and photos (many explicitly highlighting historical continuity between the seventies and today [see ]) circulated through Facebook, Twitter and Instagram served to funnel viewers back to the LLSB website which had been created as a ‘one click place to go’ to inform the wider public of the proposed redevelopment plans and encourage them to sign their petition and write to the Southbank Centre and the local council (Participant 11). In the final section of this article, we will reflect upon the communicative dynamics of the LLSB activists and analyse the Southbank Centre’s perceived failure to ‘hear’ the skate community’s heritage claims.

Figure 3. LLSB's ‘Dear Jude’ (Citation2013) video challenges the barrier between spectator and spectacle.

The Undercroft as political space

In this final section we examine the ‘critical publics’ (Warner Citation2002, pp. 45–46) bought into being by the campaign to save the Undercroft and explore the ways in which the ‘affective intelligence’ of fan communities/publics (Marcus cited in Van Zoonen Citation2004, p. 39) created mediated spaces in which alternatives to the status quo could be imagined (Livingstone Citation2005). While skate films enabled ‘skater's performances' to be ‘broadcast to one and another’ and another (Dupont Citation2014, p. 568), and to wider publics beyond the skate community, these films were not being watched by the Southbank Centre.

A traditional understanding of the public sphere as a space in which sincere individuals arrive at a consensus as to what constitutes the greater good (Habermas Citation1974) underpinned the position of both the Southbank Centre and the LLSB campaign’s understanding of the debate which unfolded about the future of the Undercroft. Thus, one of the directors from the Southbank Centre described the conflict over the future of the Undercroft as ‘two separate groups of people acting in an honourable way’ (Participant 16), whilst one of the key campaigners from LLSB maintained that the campaign tried to establish a ‘common goal for both people that everyone could benefit from’ (Participant 11). The initial failure of the two groups to arrive at a common consensus about the future of the Undercroft was rooted, in part, in the different modes of communication favoured by both organizations.

The Southbank Centre is a hierarchically organized arts institution which communicated with the skaters through ‘the usual corporate language’ (Participant 2). The Southbank Centre made an early attempt to reach out to the skate community by commissioning a third party – Central School of St Martins – to organize a series of consultations designed to engage the skaters in the process of relocating the spot to a space beneath Hungerford Bridge. However, these attempts depended heavily upon skaters’ preparedness to participate in ‘pre-given frameworks’ and therefore engendered a sense of disempowerment in the skate community (Warner Citation2002, p. 414). The Southbank Centre misread the skaters favoured communicative approach as an unwillingness to engage per se (Participant 16). Moreover, and as is often the case with informal, horizontally organized groupings, when the skaters did attempt to engage with the Southbank Centre, their actions were susceptible to being framed as ‘incoherent, uncontrollable and therefore potentially dangerous’ (Ruiz Citation2014, p. 93). This sense was summed up by one of the skaters who said that skateboarding is ‘always misrepresented by the media, by people who take the image of it or think they understand it and want to use it in some way and it skews it and taints it’ (Participant 2).

In contrast to the Southbank Centre, the LLSB campaign described itself as ‘an organic big group of people, a community who have no real formal structure and who have no hierarchy or particular leader’ (Participant 11). The Undercroft community responded to the threat posed by the Southbank Centre’s redevelopment plans by calling itself into being as a ‘self-creating and self-organizing’ organization (Warner Citation2002, p. 414). In this way, the skaters moved from being a ‘pre or proto or quasi-public’ tentatively exploring the affects and experiences offered by the Undercroft (Livingstone Citation2005, p. 29) to being a fully formed critical public (Warner Citation2002) or counterpublic (Fraser Citation1991) attempting to engage the Southbank Centre.

As the conflict unfolded, the Southbank Centre continued to try and engage the skaters through traditional communications forms such as planning documents, formal emails and press releases. Such communicative processes require very specific and narrowly defined forms of engagement which were felt to preclude the participation of the skater community in the wider decision-making process. These ‘vertically integrated’ or top-down forms of communication clashed with the more ‘tentative’ (Livingstone Citation2005) ‘alongly integrated’ (Ingold Citation2007, p. 89) or horizontal communication preferences (Downing Citation2001, Atton Citation2002) of the skate community. Thus, one of the campaigners remarked:

Certain members of our community were really against the way that we were being treated in the meetings. Yeah, being divided into different rooms, and having big screens with presentations and these grandiose plans for alternatives. But then there’s real issues to people that come here every day and skateboard every day that weren’t being addressed, so it felt like there was a lack of respect, instead of treating us as people with creative power and imagination. (Joey)

The material and digital discursive spaces set up by the Southbank Centre to engage the skate community were invariably constructed by communicative norms which are – upon closer inspection – exclusionary in their formation (Fraser Citation1991, p. 57). In doing so they failed to recognize that participation in the public sphere, as opposed to participation in the type of externally organized process identified by Warner, requires conditions in which the communicative terms of the debate are mutually constructed. Instead, the Southbank Centre addressed the skate community as users of the Undercroft, in other words as passive consumers of ‘left over’ space, rather than as community active and critically engaged in the production of (sub)cultural spaces (Livingstone Citation2005). Consequently, there was no space in which the LLSB campaign could ‘speak “in one's own voice”, thereby simultaneously constructing and expressing … cultural identity through idiom and style’ (Fraser Citation1991, p. 69).

The sense of exasperated miscomprehension prompted by the Southbank Centre’s failure to communicate with the skate community was summed up by one of the skaters who said:

[…] the main feeling at the time … is they’ve got all these words, they’re trying to look at statistics, they’ve got this, they’ve got that but just take a moment to look at the beauty of what this place is, that transcends any language […]. (Henry)

The fact that ‘the texts’ produced by the LLSB campaign were ‘not even recognizable as texts’ by the Southbank Centre did not prevent their videos from calling publics into being (Warner Citation2002, p. 414). In many ways, the LLSB campaign strategy was predicated on the notion of translation and assumed that while the average member of the wider public might lack the cultural competencies required to understand the nuances of particular tricks, many people walking past the Undercroft or clicking through the website would be able to decode the images produced and circulated by the LLSB campaign. Thus, one of the skater/filmer/campaigners said:

My biggest job would be to translate the concept of skateboarding to people who wouldn’t necessarily be open to it […] to explain to people that it’s a valid form of expression just as dance is, as music is. (Henry)

The LLSB campaign’s sophisticated understanding of social networks enabled them to circulate ‘current photos, campaigning photos and some historical stuff’ quickly to publics of non-locals and strangers. As one campaigner put it ‘you slam it on social media and everyone knows and they’re going to share it with all their people, so it resonates with thousands and thousands of people’ (Participant 11). The Southbank Centre did not ‘follow’ the LLSB campaign, choosing instead to ‘monitor’ their feeds. However, large numbers of the wider public did follow the campaign, sign electronic petitions and contact their MPs and other decision-makers. Indeed, by the end of the campaign 150,000 members of the public had joined the campaign and 40,000+ objections (the highest number in UK history) had been lodged with Lambeth Council.

As public pressure grew, the Southbank Centre did attempt to communicate via YouTube with the skate community. Unfortunately, the video they produced was described by members of the LLSB campaign as:

Having this horrible, fake, urban feel to it which is probably what they were trying to avoid. But any kind of institution that that’s far removed from the real culture that’s happening on a street level is always going to try and replicate and create these kind of pastiche culture videos – essentially the skate park itself would’ve been a pastiche of our culture. (Henry)

Figure 5. The Southbank Centre's ‘Hungerford Bridge’ video fails to communicate with LLSB on their terms.

Correspondingly, the LLSB campaign’s success depended upon the ability of skater/campaigners to maintain the ‘fine balance between presenting it in a kind of sanitized clean way that your average middleclass worker-type person could understand but at the same time staying true to the raw street essence of it’ (Henry). This ‘balance’ is difficult to maintain and is something that the skaters demonstrate an acute awareness of, as one of the key campaigners said:

Yeah, it was so hard because I had to start using language that I would not usually use to describe skateboarding because I was translating it, and every time I was saying something or putting out a video or writing something I was always conscious of what the skaters thought of it, because the biggest job was to represent them because this was the first time that the eyes were on the skateboard community. (Henry)

Conclusion

At the outset of this article we posed three key questions: how did and do the skaters feel about the space; how did they communicate these attachments and experiences; and to what extent were they heard? As we have explored elsewhere (Madgin et al. Citation2018), a reoriented and relocated conception of ‘authenticity’ is required in understanding how the skaters feel about this ‘found space’. In this article, we have borrowed the concept of ‘inhabitant knowledge’ (Citation2000) from anthropologist Tim Ingold, to articulate how the authentic is located within a collective and individual ‘bodily knowing’ of the space. This sense of the familiar and the familial – articulated through a language of ‘community’ and ‘home’ – is central to the current Undercroft users’ experience of its (sub)cultural value.

The threat to the Undercroft posed by the Southbank Centre’s redevelopment plans required the skate community to develop and evolve their bodily understandings and inhabitant knowledge into a more overtly political form of communication. Moreover, the need to communicate with policymakers and the wider public in a language beyond that of skating brought different generations of skaters together and created a more sophisticated self-understanding of the ‘community’. This was recognized by a director from the Southbank Centre who rather ruefully commented that ‘the paradox here is that it took the Save campaign for them to articulate what it was that was special about the space which they couldn’t have told me, even if I asked, before that’ (Participant 16). The rupture in routine evinced by the Southbank Centre’s plans ‘enable[d] aspects of practical knowledge to be brought to discursive consciousness’ and for the skaters to rearticulate them in a familiar and familial vernacular (Moores Citation2012, p. 107). In this way, the LLSB campaign not only ‘formulated oppositional interpretations of their identities and needs’ amongst themselves (Fraser Citation1991, p. 67), but also successfully circulated these understandings to a wider public who heard the skaters’ argument that they owned the space because they brought into existence through their everyday usage.

The skater/campaigners were not, at least initially, heard by the Southbank Centre or the heritage and planning sectors. The breakdown in communication which characterized the early stages of the relationship with the Southbank Centre was rooted not in the skaters’ failure to speak in their own voice, but in the Southbank Centre’s failure to hear those voices. Over the course of their campaign, however, LLSB successfully drew upon the inhabitant knowledge of their community to contest the exclusionary norms which structured the Southbank Centre’s attempts to arrive at a consensus about the future of the Undercroft. In welcoming everyday exchanges and conversations – both in situ at the campaign table and (re)mediated online – the skaters elicited political solidarity from the wider public, whilst discharging claims of oppositionality and exclusivity onto commercial and cultural elites. The Southbank Centre’s concession to LLSB, in the form of a long-term guarantee that the Undercroft would remain open and skateable under a section 106 planning agreement, was motivated more by political and public pressure than an explicit acknowledgement that figurative or felt ownership can amount to a legal claim. But this victory – and the subsequent collaborations between LLSB and the Southbank Centre on the ‘You Can Make History’ restoration of the original Undercroft space – is significant beyond this individual instance of contesting (sub)cultural value through emotional and experiential claims. In persisting with and nuancing its challenge to the orthodoxy that legal ownership affords an automatic position of dominance – and the power to set the discursive frameworks – the skaters offer a powerful model for conveying (sub)cultural particularity as a public good.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Winstan Whitter and Paul Richards, and all of the participants involved in the research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Pollyanna Ruiz is a Senior Lecturer in Media and Communications at the University of Sussex. Her research examines the media’s role in the construction of social and political change with particular reference to protest movements, digital communications and the public sphere.

Tim Snelson is a Senior Lecturer in Media History at the University of East Anglia. His research addressing the relationship between media and social history has been published in journals including Media History, Cultural Studies and The Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television.

Rebecca Madgin is a Senior Lecturer in Urban Development and Management, University of Glasgow. Her research examines emotional attachments to urban heritage sites in a British context. She is also interested in comparative urbanism and to this end has conducted research in Europe and Asia.

David Webb is a Senior Lecturer in Town Planning at the School of Architecture, Planning and Landscape, Newcastle University. His research explores spaces which run counter to neoliberalized statutory planning processes and in the potential contribution of these to new forms of socially centred development.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Atencio, M., Beal, B., and Wilson, C., 2009. The distinction of risk: urban skateboarding, street habitus and the construction of hierarchical gender relations. Qualitative research in sport and exercise, 1 (1), 3–20. doi: 10.1080/19398440802567907

- Atton, C., 2002. Alternative media. London: Sage.

- Beal, B., 1996. Alternative masculinity and its effects on gender relations in the subculture of skateboarding. Journal of sport behavior, 19, 204–220.

- Becker, H., 1982. Art worlds. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Borden, I., 1998. Body architecture: skateboarding and the creation of super-architectural space. In: J. Hill, ed. Occupying architecture: between the architect and the user. London: Routledge, 195–216.

- Borden, I., 2003. Skateboarding, space and the city: architecture and the body. Oxford: Berg.

- Bourdieu, P., 1984. Distinction: a social critique of the judgement of taste. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bourdieu, P., 1993. The field of cultural production: essays on art and literature. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Brake, M., 1985. Comparative youth culture. London: Routledge.

- Burgess, J., 2009. Remediating vernacular creativity: photography and cultural citizenship in the Flickr photosharing network. In: T. Edensor, D. Leslie, S. Millington, and N. Rantisi, eds. Spaces of vernacular creativity: rethinking the cultural economy. London: Routledge, 116–126.

- Calhoun, C., 1998. Community without propinquity revisited: communications technology and the transformation of the urban public sphere. Sociological inquiry, 68 (3), 373–397. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-682X.1998.tb00474.x

- Chiu, C., 2009. Contestation and conformity: street and park skateboarding in New York City public space. Space and culture, 12 (1), 25–42. doi: 10.1177/1206331208325598

- Consumerism over Culture. 2014. dir. Long Live Southbank [online]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a46rG2ivLPY [Accessed 16 April 2018].

- Dahlberg, L., 2007. Rethinking the fragmentation of the cyberpublic: from consensus to contestation. New media and society, 9, 827–847. doi: 10.1177/1461444807081228

- Dahlgren, P., 2003. ‘Reconfiguring civic culture in the new media milieu’. In: J. Corner and D. Pels, eds. Media and the restyling of politics. London: Sage, 151–170.

- Dear Jude. 2013. dir. Long Live Southbank [online]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I8fUpaD94nI [Accessed 16 April 2018].

- de Certeau, M., 1984. The practice of everyday life. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Downing, J., 2001. Radical media rebellious communication and social movements. London: Sage.

- Dupont, T., 2014. From core to consumer: the informal hierarchy of the skateboard scene. Journal of contemporary ethnography, 43, 556–581. doi: 10.1177/0891241613513033

- Edensor, T., eds., 2009. Spaces of vernacular creativity: rethinking the cultural economy. London: Routledge.

- Fraser, N., 1991. Rethinking the public sphere: a contribution to the critique of actually existing democracy. Social text, 25/26, 56–80.

- Garde-Hansen, J., 2011. Media and memory. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Habermas, J., 1974. The public sphere: an encyclopedia article (1964). New German critique, 3 (autumn), 49–55. doi: 10.2307/487737

- Halberstam, J., 2003. What’s that smell? Queer temporalities and subcultural lives. International journal of cultural studies, 6 (3), 313–333. doi: 10.1177/13678779030063005

- Hall, S., and Jefferson, T., eds., 1975. Resistance through rituals: youth cultures in post-war Britain. London: Hutchinson.

- Hermes, J., and Stello, C., 2000. Cultural citizenship and crime fiction: politics and the interpretive community. Cultural studies, 3 (2), 215–232.

- Hodkinson, P., 2003. “Net.goth”. On-line communications and (sub)cultural boundaries. In: D. Muggleton and R Weinzierl, eds. The post-subcultural reader. Oxford: Berg, 285–298.

- Ingold, T., 2000. The perception of the environment: essays in livelihood, dwelling and skill. London: Routledge.

- Ingold, T., 2007. Lines: a brief history. London: Routledge.

- Ingold, T., 2011. Being alive: essays on movement, knowledge and description. London: Routledge.

- Jenson, A., Jeffries, M., and Swords, J., 2012. The accidental youth club: skateboarding in Newcastle-Gateshead. Journal of urban design, 17, 371–388. doi: 10.1080/13574809.2012.683400

- Kahn-Harris, K., 2007. Extreme metal: music and culture on the edge. Oxford: Berg.

- Livingstone, S., 2005. On the relation between audiences and publics. In: S. Livingstone, ed. Audiences and publics: when cultural engagement matters for the public sphere. Changing media – changing Europe series. Vol. 2. Bristol: Intellect Books, 17–41.

- Long Live Southbank. 2014. Culture and heritage assessment report. Available from: http://www.llsb.com/ wp-content/uploads/2013/08/Southbank-Undercroft-Cultural-and-Heritage-Report-September-2014.pdf [Accessed 9 October 2017].

- Low, S., 2003. Behind the gates: life, security and the pursuit of happiness in fortress America. London: Routledge.

- Madgin, R., et al., 2018. Resisting relocation and reconceptualising authenticity: the experiential and emotional values of the Southbank Undercroft, London, UK. International journal of heritage studies, 24 (6), 585–598. doi: 10.1080/13527258.2017.1399283

- Moores, S., 2012. Media, place and mobility. Key concerns in media studies. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Moores, S., 2015. We find our way about: everyday media use and ‘inhabitant knowledge’. Mobilities, 10 (1), 17–35. doi: 10.1080/17450101.2013.819624

- Mouffe, C., 2005. On the political. London and New York: Routledge.

- Pentzold, C., and Sommer, V., 2011. Digital networked media and social memory. Theoretical foundations and implications. Aurora: Revista de Arte, Mídia e Política, 10, 72–85.

- Ruiz, P., 2014. Articulating dissent: protest and the public sphere. London: Pluto.

- Silverstone, R., 2002. Complicity and collusion in the mediation of everyday life. New literary history, 33, 761–780. doi: 10.1353/nlh.2002.0045

- The Bigger Picture. 2013. dir. Long Live Southbank [online]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iFaKN98Xg3E [Accessed 16 April 2018].

- Thornton, S., 1996. Club cultures: music, media, and subcultural capital. Cambridge: Polity.

- UNESCO (United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organisation), 2003. Convention for the safeguarding of the intangible cultural heritage, October 17, 2003. Paris: UNESCO.

- Van Zoonen, L., 2004. Imagining the fan democracy. European journal of communication, 19 (1), 39–52. doi: 10.1177/0267323104040693

- Warner, M., 2002. Publics and counterpublics. New York: Zone Books.

- Williams, R., 1983. Keywords: a vocabulary of culture and society. London: Fontana.

- Woolley, H., and Johns, R., 2001. Skateboarding: the city as playground. Journal of urban design, 6, 211–230. doi: 10.1080/13574800120057845

- You Can’t Move History. 2016. dir. Paul Richards and Winstan Whitter [online]. Available from: https://vimeo.com/146671695 [Accessed 16 April 2018].