Abstract

There is a widespread consensus that China’s growing network of regional trade agreements in the Asia-Pacific has crucial strategic and economic implications for states in the region. Yet despite the recognition that China’s agreements are initially limited and then expanded substantially over time, few accounts explore the strategic and economic implications of this aspect of China’s approach. This article addresses this flaw by drawing attention to the relation between regional power dynamics and China’s gradualist approach to negotiating regional trade agreements. It presents a new framework which suggests that due to China’s steadily improving economic position vis-à-vis its regional counterparts and the growing economic dependence of these partners on it, China’s negotiating approach increases opportunities to maximize its growing bargaining leverage and influence over time and thereby improve its regional position still further. This article concludes by drawing out the implications of this for the region.

China and regional integration

In recent decades, economic integration in the Asia-Pacific has accelerated markedly, with the expansion of regional production networks and supply chains, the growth of regional multinationals and the intensification of trade connections between countries in the region. The ratio of intra-regional trade between East Asian countries alone has grown from around 25% in the 1960s to over 50% by the mid-2010s (Dent, Citation2017, p. 18). One of the most important mechanisms by which this has occurred is through the conclusion of a raft of regional trade agreements (Kawasaki, Citation2015, p. 20) and China has played both a direct and indirect role in stimulating this process (Das, Citation2014; Kawasaki, Citation2015). China’s approach to the design of regional trade agreements has received particular attention (Antkiewicz & Whalley, Citation2011; Li, Wang, & Whalley, Citation2017; Song & Yuan, Citation2012; Zeng, Citation2016) with the consensus that its agreements are of low quality in terms of coverage and liberalization because they are driven largely by political, not economic, considerations (Antkiewicz & Whalley, Citation2011; Bergsten, Citation2007; Kwei, Citation2013; Zeng, Citation2016). As of 2019, China has concluded agreements in the Asia-Pacific with the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN), Hong Kong, Macao, Pakistan, Singapore, The Republic of Korea, New Zealand, and Australia. Each of these agreements incorporates specifically Chinese preferences in terms of design and, crucially because of the low quality of the initial agreement, entail substantial subsequent expansion in terms of both coverage and liberalization (Antkiewicz & Whalley, Citation2011; Ravenhill, Citation2010; Zeng, Citation2010). Yet whilst the political and strategic implications of these deals have received a great deal of attention, surprisingly little attention has been paid to the relation between these economic and political implications and the dynamic evolution of these deals over time, as if their political impact is a function only of their original design but not their subsequent expansion and modification. In short, by analysing China’s agreements as a static ‘snapshot’ rather than an on-going process, existing accounts may miss an important part of the story (Pierson, Citation2004).

Static approaches are particularly problematic in analysing trade in the Asia Pacific both because of the rapid pace of change in the region and because the growth in China’s relative economic power has increased fears on the part of China’s trade partners regarding the risks of greater integration with, and increased dependence upon, a large, growing regional power (Ba, Citation2014). The situation in the region has become even more fluid in recent years with the seeming (though perhaps temporary) retreat of the U.S. from active participation in trade integration in the region due to its withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership in January 2017 (Park, Citation2017). At the same time, potential new agreements are on the horizon and are likely to have significant implications not only for the region, but the global economic system more generally (Wang, Citation2011, p. 497). Understanding the relationship between China’s power trajectory and the implications of its trade agreements then is all the more pressing today given the uncertain future of integration in the region.

To explore the relation between China’s power trajectory and its design of regional trade agreements, I begin by analysing each of China’s agreements in turn and emphasise two elements. First, China has offered generous up-front terms to a number of its more junior negotiating partners, despite its clear ex-ante bargaining advantage. Second, it has exhibited a preference for narrower, incomplete initial agreements that are progressively expanded over time. In the first section of the paper, I develop a new framework for understanding the implications of China’s strategy and suggest that its progressive approach to regional trade agreements increases opportunities for China to maximize its growing bargaining leverage and regional influence by extending the negotiation of these agreements over time. In the subsequent section, I establish the regional power dynamics between China and its trade partners, before moving on to a detailed analysis of each of China’s regional agreements. I then show how China’s gradual approach contrasts with that adopted by other major regional (but not rising) economic powers in the region, Japan and the United States, who have tended to adopt much more comprehensive initial agreements that require little if any subsequent expansion. This article concludes by drawing out the implications of China’s approach for the future of the Asia-Pacific.

Dependence, relation-specific investments and bargaining power

It has long been recognized that agreement design is crucial in determining the downstream bargaining power of contracting parties both at the domestic and international levels (Coase, Citation1937; Cooley & Spruyt, Citation2009; Williamson, Citation1983). One of the primary purposes of any such formal agreement is to protect one party against subsequent opportunism or reneging by the other. This vulnerability becomes particularly acute where one party makes comparatively more costly investments in the relationship that cannot be easily utilised for a different purpose (Williamson, Citation1983, p. 527). Therefore, any agreement that induces one party to make such investments presents the possibility that they can later be exploited unless sufficient safeguards are included. Such problems are exacerbated further where an agreement leaves details to be finalized in subsequent negotiations because the specific investments of one party can be, in effect, taken hostage and used as leverage when subsequent negotiations take place. Such limited agreements may arise then because it is advantageous for one party to negotiate at a later date and the weaker party should therefore fear the increased leverage of the more powerful at subsequent negotiation stages (Cooley & Spruyt, Citation2009, p. 6). Indeed, there is a well-established international relations literature pointing to the various ways in which vague or incomplete international agreements and institutions present opportunities for exploitation of the weak by the strong (Cooley & Spruyt, Citation2009; Krasner, Citation1976; Stone, Citation2011).

Adding to the risks inherent in such bargaining dynamics in relation to trade agreements is that states can utilise trade as an effective means of broader political influence. In his classic exploration of this issue, Albert Hirschman distinguished between the supply effect of trade and the influence effect. In discussing the latter, the political influence of one state upon another resulting from trade, he suggested ‘derives from the fact that the trade conducted between country A, on the one hand, and countries B, C, D, etc., on the other, is worth something to B, C, D, etc., and that they would therefore consent to grant A certain advantages—military, political, economic—in order to retain the possibility of trading with A.’ (Hirschman, Citation1945, p. 17). In order for a country to maximize its influence over other states via trade therefore, it must create a situation in which they would pay a heavy price in order to maintain the trading relationship. To do so a state must create a situation in which it is difficult for partners ‘to dispense entirely with the trade they conduct with [it], or… to replace [it] as a market and a source of supply with other countries.’ (Hirschman, Citation1945, p. 17). The costs of doing so depends on three primary factors: the value of the trading relationship to the partner country, the costs of switching or interruption of the trading relationship, and ‘the strength of the vested interests which [a country] has created by its trade within the economies of [its partners]… (Hirschman, Citation1945, p. 18). In the subsequent discussion, these factors are explored in relation to China’s growing regional influence and regional trade partnerships. They are referred to as dependence (measured by the relative importance of the trading relationship to a country), switching costs (indicated by the hypothetical ease of transfer of trade with China to other countries) and political sensitivity (measured by the dependence of an economically and politically important economic sector on the continuation of the trading relationship with China). This article utilises the idea of the influence effect of trade to develop a new framework to explore the relationship between these factors and the gradualist approach to trade agreement design adopted by China. Combining these two factors, with respect to China’s trade policy, the argument is developed that China’s gradual approach to trade negotiations has negative implications for the downstream bargaining power of partner states. The strategy of gradual negotiations allows China to hold out the reward or punishment of subsequent agreement expansion or revision and thereby increases its broader influence more effectively than would an approach that resulted in an initially comprehensive agreement.

To be more precise, it is suggested that the gradual negotiation of trade agreements by China leads to two consequences. First, the initial limited agreement and up-front concessions leads trade partners to make relation-specific investments which allow them to maximize the benefits of the trading relationship with Beijing. In line with the literature on this topic, such investments are defined as relation specific when they arise following a contractual agreement and would be costly to transfer or re-purpose for purposes outside the agreement (Klein, Citation1980, p. 357; Williamson, Citation1983, p. 522). For example, a country that is highly dependent on exporting a particular good to the Chinese market at a very high volume will find it difficult to switch elsewhere without incurring substantial costs given the almost unmatched size of the Chinese market. Investments in such export industries are consequently treated as relation specific in the subsequent discussion. The second consequence of the gradual approach adopted by China is that these initially limited trade agreements induce dependence in China’s trade partners not only in terms of investments, but more broadly. This dependence can be measured with respect to the relative importance of China to the trade partner. For example, if China is the destination for 40% of exports from a partner country, but the partner country is the destination of only 4% of China’s exports, it can reasonably be said that the export industry of the partner country is more dependent on the continuation of the relationship than China. These factors combine to ensure that the bargaining power of the partner is reduced in future bargaining across a range of issue areas. Without the gradual approach adopted by China in its negotiations and the potential to revise or expand the contract subsequently, the utilisation of this leverage would not be so directly available to China. The gradual approach to negotiations is therefore important in making it much more difficult for partner countries to exit from cooperating with China and provides a substantial reason for maintaining good relations more broadly. Finally, because of China’s positive power trajectory viz-a-viz its trade partners in the region, the leverage provided by the initial contract increases over time, which exacerbates this dynamic even further and leads eventually to increasingly unfavourable agreements for junior partners.1 The subsequent empirical analysis constitutes a plausibility probe of this idea.

Regional power dynamics

That China constitutes a rising power within the Asia-Pacific region, in terms of its economy and trading position, there can be little doubt. Since its economic reforms of the early 1980s, China’s GDP has grown at an average annual rate of over 9.5% and its share of global GDP has increased from 2.3% in 1980 to over 18% in 2017 (IMF, Citation2018). By contrast, other major economies in the region, Japan, Korea, Indonesia and Malaysia have grown at a respectable but comparatively meagre average rate of around 2%, 6%, 5.5% and 6%, respectively (IMF, Citation2018). Moreover, since 2010, these average GDP growth numbers have been 7.8% for China and 1.4%, 3.3%, 5.5% and 5.5% for Japan, Korea, Indonesia and Malaysia, respectively. In short, the economic gap between China and its major regional competitors and trade partners has been growing wider, not narrower in recent years.

In terms of trade too, China has become an increasingly important economic hub in Asia, with a growing proportion of its imports coming from its Asian partners and its exports to the region also growing (Morck & Yeung, Citation2016, p. 297). China is increasingly the most important destination for exports from many countries in the region (Blancher & Rumbaugh, Citation2004; Tong & Zheng, Citation2008) and as a result, it presents both a risk and an opportunity for its regional partners (Ba, Citation2014, p. 150). For example, exports from the Association of South East Asian States (ASEAN) to China increased by almost 140% between 1996 and 2002, even before a trade agreement between the two parties was concluded. Between 2001 and 2009 by contrast, ASEAN exports to the U.S. market declined by 7.5%, and China had become ASEAN’S largest trade partner and export market by 2010 (Ba, Citation2014, p. 150). More broadly, China has become the most important export market for other East Asian economies whilst its own export dependence on East Asian markets has declined (Ravenhill, Citation2006, Citation2010, p. 5). Exports to China now constitute an economically important proportion of its regional partners’ total exports whilst the same is not true for China (Morck & Yeung, Citation2016, p. 297). This closer economic integration with regional partners has been an explicit goal of Chinese foreign policy and since China’s entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001 it has pursued an active strategy of securing trade agreements with its regional partners which form the foundations of China’s regional influence (McNally, Citation2007).

What will be the impact on the Asia Pacific as China’s trade policy evolves in the coming decades? Unlike previous accounts, the purpose in analysing China’s regional agreements here is not to provide a comprehensive description of China’s foreign trade strategy in the region. Rather the objective is to think through the consequences of China’s gradualist approach for China and its regional partners. The article accordingly focuses on the consequences of China’s design choices, not the motives driving them. In other words, this article is agnostic on whether the consequences flowing from China’s approach result from a deliberate strategy or merely a side effect with important consequences for the bargaining power of its partners. The subsequent sections explore the interplay between design and power dynamics by exploring each of China’s agreements in turn, utilising original analysis of the agreements themselves combined with analyses provided by the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the latest trade data.

China’s regional trade agreements

When it comes to bilateral trade agreements, China is a relative newcomer as it only concluded its first agreements in 2003. Yet in the last decade, it has become much more active in the pursuit of a trade strategy which aims to strengthen economic relations with major trade partners and emerging markets (Aggarwal & Urata, Citation2013; Barfield, Citation2007, p. 104; Goh, Citation2014). As a result, it is today party to 14 bilateral trade agreements, of which 8 are with partners in Asia or the Pacific. The choice of partners immediately reveals number of patterns – until recently China has tended to target economically minor but politically significant partners (Pakistan, Hong Kong, Macao, New Zealand and Singapore), only recently progressing to negotiations with larger economic powers such as Korea. Beijing divides its trade agreements into two broad categories, in the first category, with nearby countries, China has adopted the ‘neighbouring country relations strategy’. In the second category are agreements with countries possessed of particular resources and raw materials required by China, such as Chile or Australia (Barfield, Citation2007). These categories are not mutually exclusive and there is overlap in important instances (Australia is an obvious regional example here).

In many of the negotiations over these agreements, Beijing’s negotiators have pushed for agreements that are initially narrow, entail limited liberalization and are subsequently expanded over many years in numerous negotiation rounds. Thus, unlike the approach adopted by other major trading powers, the U.S., Japan, and the EU, China’s agreements differ in their designs and leave ‘many aspects as the subject of continued negotiations, and…several omit elaborate dispute resolution procedures’ (Hepburn et al., Citation2007, p. 20). China’s agreements also often incorporate few advanced provisions (such as environmental protections) and often simply reiterate existing commitments under the WTO. Even the few advanced provisions that are included in some Chinese trade deals are often vague and Liberalization of agreements is usually shallow. Dispute mechanism procedures are weak and often not clearly defined either (Salidjanova, Citation2015, p. 18). The second notable characteristic of China’s approach is the number of unusual up-front concessions China has provided to its more junior partners. This is borne out particularly with respect to regional deals with ASEAN and Pakistan, but also in relation to almost all of China’s regional trade partners where China has liberalized a wider range of goods and services over a shorter time period than many of its partners. The next section outlines these patterns in more detail in relation to each of China’s regional trade partners.

Agreements with Hong Kong and Macao (2003)

China’s first trade agreements following accession to the WTO in 2001 were with Hong Kong and Macao, territories with an obvious special significance given their political status with respect to the mainland. Despite this unique status, they remain instructive examples of China’s subsequent approach to more substantial regional trade deals. The political motivations behind the Hong Kong and Macao deals were obvious – they allowed China to demonstrate the benefits of economic integration with the mainland whilst also safeguarding increasingly closer political and economic ties, but they did so in an initially limited, piecemeal fashion. In the Hong Kong agreement, there was a clause that explicitly stipulates further negotiations to extend the deal at a later stage with the initial agreement only incorporating thirteen pages of text which included no explicit dispute resolution procedures (Antkiewicz & Whalley, Citation2005, p. 2). In 2004, an expansion of the Hong Kong deal was agreed, and supplementary agreements have consequently been negotiated five further times since then, with negotiations taking place in 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008 and 2009 to expand the coverage of the deal. Further, given Hong Kong’s status as a trading port, the agreement entailed a ‘one-sided concession’ from China to unilaterally reduce tariffs on imports to zero by 2006 (Antkiewicz & Whalley, Citation2005, p. 10). As a result, it has been said that China gained little economic advantage from the deal as prior to the agreement only around 20% of goods trade from Hong Kong was tariff free but after implementation this figure stood at 90% (Hufbauer & Wong, Citation2005, p. 6). Partially as a result of the agreement, the two economies are increasingly interdependent and, Hong Kong’s dependence on the PRC had increased substantially following the deal (Cabrillac, Citation2004). As of 2018, China is responsible for over 50% of Hong Kong’s total trade, compared with 25% in 1997. It is also the source of 46.3% of its imports and the destination of 44.2% of exports (Trade and Industry Department Government of Hong Kong, Citation2019). At the same time, Hong Kong’s role as an economic gateway to China has become less important, as a result of economic liberalization in China and the development of competing port cities in the mainland. The size of Hong Kong’s economy relative to China’s has also declined due to growth of the Chinese economy (Scobell & Gong, Citation2016, p. 3). Similarly, and unsurprisingly, the dependence of Macao has also grown, as of 2017 China is recipient of 7% of Macao exports (2017) and 35% of imports into Macao come from China (World Bank, Citation2018d). In short, in the years since the first agreement was concluded, the economic dependence of both territories on the mainland has increased dramatically (DFAT Australian Government, Citation2018). Given the political and geographic situation of these two territories, abandoning or substantially modifying the trading relationship with China is largely precluded and so the costs of switching to alternative suppliers and markets would be prohibitive in economic and political terms. Indeed the growing economic dependence of each territory has led to the a growing formal and informal influence of China in Hong Kong and Macao and with it reduced the desire or capacity to reduce economic ties with the mainland (Holliday, Ngok, & Yep, Citation2004; Yuen, Citation2014, p. 71). The ability or desire to resist further expansions of the agreement is therefore also limited. When the agreements entered into force in 2004, they covered just a few service sectors and the facilitation of investment. Today the agreements now comprise several supplementary agreements. For example, the ninth supplementary agreement, signed in 2012 with Hong Kong, expanded the number of service sectors and now includes education and training and rail transportation (DFAT Australian Government, Citation2018). A further supplementary agreement (the tenth) entered into force in 2014 and this further liberalized trade in services, with a further expansion of market access with the mainland. We see in both agreements then a similar pattern, a generous initial agreement that is very limited in scope, accompanied by a growing dependence of the junior party which is combined with the gradual expansion of the agreement over many years.

ASEAN–China FTA (2004)

Arguably the most important regional trade agreement concluded by China is that with the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN), a group of states with a market size of around 630 million people and a collective GDP of almost 2.5 trillion dollars (ASEAN Secretariat, Citation2016, p. 1). A framework agreement between the two parties was finalized in 2002 and an agreement on goods liberalization was signed two years later in 2004. In a third round of negotiations, a deal covering liberalization in services was concluded in 2007 and then two years later, the parties agreed a deal on investment (Salidjanova, Citation2015, p. 8). Since 2007, there have been multiple rounds of negotiations and expansions of the agreement culminating in another upgrade of the deal in 2015 despite misgivings of some important ASEAN members (Xinhua News, Citation2015).

From the start of the negotiating process, ASEAN states were worried that their markets would be overwhelmed by more competitively produced Chinese goods (Ba, Citation2003). Chinese officials claimed to be attempting to overcome these concerns by pursuing a policy of generosity, pointing to the approach of giving a lot whilst receiving little in return (Salidjanova, Citation2015, p. 8). As evidence of this, China offered concessions to ASEAN in the form of an ‘Early Harvest Program’ (EHP) which provided protections for the agricultural sectors in ASEAN countries during implementation of the agreement. It allowed tariffs on around 200 agricultural products to be eliminated by China whilst reciprocal liberalization was not required on the part of less developed ASEAN members Cambodia, Myanmar, Laos and Vietnam (Ba, Citation2003, p. 637). There was also concern for ASEAN that less developed members would suffer particular harm from Chinese competition. As a result, China agreed to extend most favoured nation status to ASEAN’s newer members and provided them an extra 5 years to comply with the agreement (Ba, Citation2003, p. 637).2 This meant that in the early stages of cooperation, these states gained access to China’s market before reciprocal access was granted. China also agreed to write-off debts owed by these less developed states to China. These initiatives appear to have had the desired effect and the EHP was concluded as part of the framework agreement in 2002. This agreement (perhaps unsurprisingly) is extremely limited. The framework deal included no dispute resolution mechanism but instead contained a clause which stated the DRM was to be negotiated at a later date. Article 11 of the text of the agreement states:

The Parties shall within 1 year after the date of entry into force of this Agreement, establish appropriate and formal dispute resolution procedures and mechanism for the purpose of the agreement. Pending the establishment of the formal dispute settlement procedures and mechanism under paragraph 1 above, any disputes concerning the interpretation, implementation or application of this Agreement shall be settled amicably by consultations and/or mediation. (ASEAN Secretariat, Citation2002)

The goods deal between China and ASEAN was subsequently concluded in 2004 and was limited compared to international standards: It allowed each party to register hundreds of goods on ‘sensitive’ and ‘highly sensitive’ tracks that are not subject to tariff reductions until 2020 and up to 40% of some states tariff lines can be included in these sensitive categories. Article 6 of the agreement also states that ‘Any Party to this Agreement may, by negotiation and agreement with any Party to which it has made a concession under this Agreement, modify or withdraw such concession made under this Agreement.’ The text also includes a vague exception clauses such as: ‘nothing in this Agreement shall be construed to prevent the adoption or enforcement by a Party of measures: (a) necessary to protect public morals;’ (ASEAN Secretariat, Citation2006).

Similarly, the services component of the deal, signed in 2007, is limited in scope, and contains a clause that states ‘At subsequent reviews… the Parties shall enter into successive rounds of negotiations to negotiate further packages of specific commitments under Part III of this Agreement so as to progressively liberalise trade in services between the Parties.’ In terms of depth of liberalization too, the services agreement falls well short of similar EU and U.S. agreements. The liberalization commitments in the services deal are broken down in to two packages: the first package entail commitments that go beyond existing GATS commitments. However, the parties also agreed to conclude a ‘second package’ of commitments to improve on the first within one year. Further negotiations are ‘anticipated to conclude further specific commitments on liberalizing trade in services under the agreement review mechanism’ (WTO, Citation2015a, p. 10).

The agreement with ASEAN has subsequently been expanded through an additional agreement on investment, concluded in 2009 but, like the other components, is itself vague and leaves much to subsequent negotiations. For example, it suggests that a contracting party should not expropriate investments ‘unless for a public purpose’ It also allows exceptions if ‘necessary to protect public morals or to maintain public order’. In 2009, a further memorandum on intellectual property is noteworthy because it contains a clause on dispute resolution which states any disputes ‘will be settled amicably through mutual consultation or negotiation among all participants through diplomatic channels without reference to any third party or tribunal’ The potential implications of this, given the distribution of bargaining power between the two parties, are obvious.

The agreement underwent further expansion in 2010 when the China-ASEAN free trade area was implemented and a year later in another side payment, China offered ASEAN members a package of $10 billion credit plus access to a new $3 billion maritime cooperation fund(Song & Yuan, Citation2012, p. 113). The effects of the expansion of the FTA in 2010 have been positive in terms of sheer trade volume, with trade between China and ASEAN growing to $480 billion in 2014. However, this has come with costs for ASEAN: its goods trade with China went from a surplus prior to the deal to a nearly $45 billion deficit in 2013 (Salidjanova, Citation2015, p. 8). As a result, businesses in ASEAN’s largest member state, Indonesia, were already expressing concern prior to implementation of the deal that industries such as textiles and electronics would be adversely effected (The Economist, Citation2010). Despite these on-going concerns, a further protocol was signed in 2015 to upgrade the free trade area even further.

Here alongside this gradual expansion, we can also observe an increased dependence of ASEAN’s largest members on China since the first goods agreement was concluded: In 2006, China was the fourth most important destination for Indonesian exports, worth $8.3 billion. By 2017, it had become the top destination for Indonesia’s goods, with exports worth over $23 billion, since conclusion of the agreement Indonesia has possessed a trade deficit with China over many years as a result(Lee, Citation2015, p. 10). Similarly, in 2006, China was the fourth most important destination for Malaysian exports, worth $11.6 billion; by 2017, it was the second most important destination for exports, worth almost $30 billion (IMF, Citation2017). Other ASEAN members have become increasingly dependent on the relationship with China too because of the kinds of products they import, for example, Vietnamese manufacturers are dependent on importing Chinese intermediary products such as machinery, and electronic components. For Thailand too, it is highly dependent on importing intermediary products from China (Lee, Citation2015, p. 9). Overall by 2015 ASEAN’s trade with China had increased to three times its value in 2005 (Das, Citation2017, p. 2) and despite concerns being raised by some ASEAN members, as of September 2017 China, was calling for the two parties to upgrade the deal still further (Straits Times, Citation2017).

From the conclusion of the framework agreement up until the present, the trade agreement between ASEAN and China has been characterised by two core elements: The limited nature of the initial agreement combined with initial generosity on the part of China leading to greater dependence of ASEAN states. This is followed by successive extension of the agreement in spite of concerns and deteriorating bargaining power of ASEAN members. It is also interesting to note for the future that many of the previous extensions themselves explicitly incorporate further negotiations and incorporate a significant number of vague clauses.

Pakistan–China FTA (2006)

China concluded an agreement with Pakistan in 2006 and as with the ASEAN deal, the outcome of negotiations was a limited initial agreement on trade in goods that required subsequent expansion. Despite these extensions to the agreement on services, investment and banking, negotiations are still on-going to extend the agreement further. Notably the contract extensions have been in areas where China has a growing advantage, particularly in terms of construction and banking services. Despite this, in recent years further agreement expansion has continued to be discussed and negotiations continue despite growing objections from many of Pakistan’s businesses fearful of further exposure to Chinese competition (Paracha, Citation2016).

Prior to the agreement, trade between the two countries was largely concentrated in low-value goods with much less trade in services (WTO, Citation2008, p. 2). Consequently, it is perhaps understandable that the initial 2006 agreement covered liberalization only in goods, yet even here, tariffs were eliminated on just 35% of products upon entry into force (WTO, Citation2008). Expansion of the goods agreement is built-in to the initial deal and future liberalization and extension were dependent on subsequent negotiations under phase II of the agreement. In addition to its low level of coverage in goods, the initial agreement does not include chapters on competition, intellectual property rights, or public procurement but does establish a commission comprising representatives from both parties in order to expand the deal in these areas at an unspecified later stage (WTO, Citation2009, p. 7).

Perhaps surprisingly, despite the power asymmetry between the negotiating parties, China yet again offered a concession in the form of and Early Harvest Program in order to support the agriculture sector in Pakistan during implementation of the goods deal. Interestingly however, this short-term benefit for Pakistan has exacerbated the growing asymmetry in dependence over time given that it has increased trade in these products between the two countries. Agriculture constitutes just over 20% of Pakistan’s economy and employs around 43% of the entire labour force (CIA Factbook, Citation2017) and in 2006, agricultural products accounted for over 13% of Pakistan's merchandise exports, whilst for China agricultural products accounted for just 3.4% (WTO, Citation2008, p. 1).

Alongside the limited scope of the goods agreement there was also weak liberalization in a number of important goods categories including textiles and plastics and, as a result, the agreement falls short of the requirements of GATT article XXIV on eliminating tariffs on substantially all trade. The omission of textiles was particularly significant since these made up around 72% of China’s imports from Pakistan but only 7% from China to Pakistan (WTO, Citation2008, p. 4). Following the goods agreement, an amending protocol was added to the contract in October 2008, creating special ‘China-Pakistan investment zones’. This protocol included a clause stating that the two parties will specifically consider reduction/elimination of tariffs on goods produced in these zones and consequently further reductions will be subject to subsequent negotiations and extensions of the agreement (WTO, Citation2008). A year after this protocol, and despite the relatively low level of trade in services between the two countries, the initial agreement was further expanded to include liberalization in services in 2009. In 2011, a second phase of talks on further expanding the agreement was initiated. Following the conclusion of the goods agreement and before the signing of the services agreement China possessed a large trade surplus in services with Pakistan (WTO, Citation2011, p. 3).3 This surplus was concentrated in construction and transportation sectors in 2008 (WTO, Citation2011, p. 3). It is important then that as part of the services agreement Pakistan improved its commitments in these two areas compared to its WTO commitments under the Generalized Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) whilst Chinese commitments remained unchanged and in line with its existing GATS commitments(WTO, Citation2011, p. 9). In the year that the agreement was concluded, construction made up just 0.9% of Pakistan’s trade in services whereas for China this number was 7.3% (WTO, Citation2014a, p. 18, 2015b, p. 78). We see then an initial agreement that favoured Pakistan but over time it has been expanded in ways more beneficial to China. Over this same period Pakistan’s dependence on the relationship has been growing. Indeed, all three elements of a trade policy that maximizes China’s influence are present in the relationship with Pakistan. Trade dependence, high switching costs due to relation specific investments, and domestic sensitivity to changes in the trade relationship.

The services agreement, as with the deal on goods, is not only limited in coverage but also explicitly incorporates further extension of the treaty at a later date, a WTO report summarizes:

Three years after the entry into force of the Agreement, the Free Trade Commission established under Article 75 of the agreement in goods may review the Agreement taking into account the developments and regulations on trade in services of the Parties as well as the progress made at the WTO and other specialized forums. The Parties may also review and modify the Agreement when necessary following a request by a Party (Article 19). (WTO, Citation2011, p. 16)

The agreement thus sets out further opportunities for direct bargaining between the two parties even as the power asymmetry and dependence of Pakistan grows. By 2015, a new banking services protocol was also concluded alongside a large round of memorandums of understanding between the two parties (Haider, Citation2015). This is another example where the agreement has been expanded to the advantage of China given that its more significant banking and services sectors (WTO, Citation2011, p. 16). Alongside these protocols and extensions a further eight rounds of trade negotiations have occurred under phase II of the agreement, culminating in the most recent negotiation to upgrade the deal in late 2016 despite Pakistan’s reluctance to further expand the agreement (Haider, Citation2015). In particular, Pakistan is holding up negotiations because many domestic producers feel increasingly unable to compete with their Chinese counterparts (Khan, Citation2016). As a result, the agreement continues to be highly controversial in Pakistan as China has recently demanded that Pakistan reduce duties to 0% on 90% of products under the proposed revised FTA. Indicating the increased pressure resulting from gradual expansion of the agreement, the response from Pakistan has been simply that ‘we can’t do it’ (Khan, Citation2016). Thus far, under phase I of the agreement, Pakistan has reduced duties to zero only on 35% of its products, while China has reduced duties to 0% on 40% of Pakistan’s exports, consequently expansion to 90% is a challenge for Pakistan already struggling to cope with Chinese competition (Khan, Citation2016). Pakistan has recently requested revision of existing elements of the treaty because they argue that the agreement itself brings no added advantages compared with countries that have no agreement with China. Yet China is ‘unwilling to accept Islamabad’s demand for the revival of the preferential treatment for exportable products under the FTA’ (Khan, Citation2016). In parallel with this dynamic, we see China becoming an increasingly important trading partner for Pakistan: Goods exports from Pakistan to China have increased from $500 million in 2006 when China was Pakistan’s eighth most important destination for exports of goods, to $1.4 billion in 2017 when it was its third most important destination for exports for goods. Exports of goods from China were worth $4.2 billion in 2006 and Pakistan was the 33rd largest importer, in 2018, this figure was $18 billion but Pakistan was in 27th place (IMF, Citation2017). China is the source of almost 7% of Pakistan’s imports and the destination for around 27% of its exports. Its next biggest destination for exports is UAE at half that value of (13%). China takes almost a higher percentage of Pakistan’s exports than its next four export destinations combined (World Bank, Citation2018f).Given this, for Pakistan finding an alternative destination for these exports, whilst not impossible, would indicate high switching and adjustment costs for domestic producers.

Crucially, despite the reluctance of some in Pakistan, the process of agreement expansion has continued, and Pakistan possesses limited options given the high costs of replacing its third largest market. There have now been eight negotiation rounds under the second phase of the trade agreement (Financial Express, Citation2017) with Pakistan continuing to show ‘concern about not being able to get meaningful market access during the first phase of the FTA’ (Dawn, Citation2017).

As with the ASEAN deal, an agreement that was initially accompanied concessions from the rising state has over time had a negative impact on the economy of the junior partner. Also, similarly to the ASEAN deal, the value of the initial concessions in agriculture were time limited and now despite requests to modify the existing agreement from Pakistan, negotiations are ongoing to extend the agreement further. Indeed this dynamic shows no signs of abating, Pakistan’s economic dependence upon China is likely to increase in future and consequently it will be less likely to be able to resist Beijing’s growing bargaining power advantage (Maini, Citation2018)

New Zealand–China FTA (2008)

Following the Pakistan deal, China signed an agreement with New Zealand, its first trade deal with an advanced economy, in 2007. At the beginning of negotiations, China was New Zealand’s fourth largest export market and its second largest import source whilst New Zealand was China’s 59th largest destination for exports and 52nd largest import source (WTO, Citation2010). Today China is New Zealand’s top trading partner both in terms of exports and imports. It constitutes the source of over 22% of NZ imports and the destination for almost 20% of New Zealand’s exports (World Bank, Citation2018e). The choice of New Zealand had particular significance for China as it was also the first advanced economy to recognize China’s status as a market economy, which had important implications for China’s position within the WTO. It has been suggested that the agreement is an exception to the trend of China concluding limited, politically driven bilateral trade agreements in the region precisely for this reason (Leal-Arcas, Citation2013, p. 294). The agreement can in this sense be seen as a reward to New Zealand for this recognition and stands in notable contrast to the lack of a New Zealand–U.S. trade deal, despite the best efforts of New Zealand to secure such an agreement. Nevertheless the agreement with New Zealand remains limited compared to international standards, and there are no provisions in the initial agreement on government procurement and no coverage of behind the border (or Singapore) issues (WTO, Citation2010, p. 30). During negotiations, New Zealand officials were pushing for broader market access but were ‘rebuffed by the Chinese’ (Salidjanova, Citation2015, p. 9). However, in relation to the few areas that are covered, liberalization has been relatively deep compared to China’s previous agreements and, unlike other agreements signed by China, the goods and services components were concluded simultaneously from the start. Despite this however, coverage of services was limited due to China’s insistence on a positive list approach (whereby only services explicitly mentioned in the agreement are covered) (WTO, Citation2010, p. 30).

Following implementation of the agreement, goods exports from New Zealand to China almost quadrupled since entry into force and China is now New Zealand’s largest trading partner(MFAT New Zealand, Citation2018). In 2007, China was New Zealand’s fourth most important destination for exports worth $1.7 billion. By 2017, China was the top destination for exports from New Zealand worth $8.4 billion. In 2007, the year before conclusion of trade talks China’s exports to New Zealand have gone from $2.1 billion to $5.1 billion in 2017 with New Zealand going from 56th most important destination for China’s exports to 50th (IMF, Citation2017). The initial agreement induced New Zealand exporters to focus much of their production in servicing the Chinese market. This is particularly true in the economically and politically vital dairy sector, New Zealand’s largest export industry with respect to China (Kendall, Citation2014).This sector constitutes around 3.5% of the country’s GDP, contributing almost $8 billion per year and employing 40,000 workers (Ballingall & Pambudi, Citation2017). There has also been substantial investment in the sector in both directions following implementation of the deal (Whitehead, Citation2018).

In 2016, both parties agreed to extend the agreement and commence further negotiations on, among other issues, rules of origin, services, competition policy, e-commerce, agriculture, the environment, and government procurement. As of June 2018, there have been four further rounds of negotiation on these issues, but no time frame has been agreed on the conclusion of these talks. Whilst there have been signs that in recent years the Chinese government has utilised its economic leverage to influence the broader foreign policy in New Zealand, most recently with respect to the controversy surrounding Huawei, it remains to be seen whether this pattern will be sustained (Graham-McLay, Citation2019). In the agreement with New Zealand then we again observe both increased dependence and relation specific investments in politically sensitive areas by New Zealand, accompanied by gradual expansion of the agreement.

Singapore–China FTA (2008)

In the same year that the New Zealand deal was concluded, China finalized its agreement with Singapore. It built on the agreement with ASEAN (of which Singapore is a member) and it is broader in coverage than some other agreements signed by China. As with the agreement with New Zealand, the deal with Singapore covers trade in goods, services and also incorporates clauses related to rules of origin, trade remedies, sanitary measures and technical barriers to trade and investment. Despite this, the agreement covers fewer issues than comparable agreements signed by Singapore, for example with the United States, Japan or the EU. The China–Singapore FTA is significantly shorter; it extends to around 75 pages whereas the U.S agreement is over one and a half thousand pages long. No notable concessions were offered by either party in the initial negotiations, though China conceded slightly more in tariff reductions due to the already high level of liberalization by Singapore as an open trading state. The agreement entails preferential treatment of around 95% of Singapore’s exports to China whilst Singapore grants preferential tariff-free treatment to 100% of China’s exports to Singapore (WTO, Citation2014b, p. 10). The relationship between Singapore and China does not exhibit the levels of highly asymmetric dependence as China’s other trade partners because of Singapore’s global trading position and diversity of other trade partners. Singapore is the only ASEAN member without a trade deficit with China (Das, Citation2017, p. 3). Nevertheless, 10 years after the agreement was signed, China is Singapore's primary destination for goods exports, while Singapore is China's biggest source of foreign direct investment. China is now Singapore’s top trading partner in terms of both exports and imports. It is the recipient of over 14% of Singapore’s exports and the source of over 13% of imports (World Bank, Citation2018g). A survey found significant investment from domestic producers in Singapore into China, noting that China was the third largest destination for overseas production bases by Singaporean companies (Kawai & Wignaraja, Citation2011, p. 179). In 2015, the parties commenced negotiations to upgrade the agreement in areas such as services and investment, and in November 2018, both parties agreed to a further upgrade of the agreement after eight rounds of negotiations over three years (Siong, Citation2018). As with China’s other regional agreements, both dependence and relation specific investments, along with gradual expansion of the agreement, are present in the case of the China–Singapore relationship.

Australia–China FTA (2015)

China’s agreement with Australia, concluded in 2015, took more than a decade to finalize and the reasons for this slow progress arguably resulted from China’s gradualist approach. Negotiations between the two countries consistently stalled due to their inability to agree on the scope of the agreement. It has been suggested that this was because Australian negotiators wanted a ‘commercially meaningful’ comprehensive agreement with Chinese negotiators conversely preferring a ‘selective, gradual approach to trade liberalisation’ rather than a ‘single undertaking’ (Jiang, Citation2008, p. 182). Chinese negotiators also argued that so-called ‘behind the border issues’ should not be included in the initial agreement (Jiang, Citation2008). There was similarly disagreement over the form of any dispute resolution mechanism (DRM). Australia had a preference for formalized dispute resolution procedures whereas China preferred ‘bilateral negotiation and friendly consultation, with third-party adjudication as the last resort’. Liberalization of services in particular was an obstacle to a deal, with Australia pushing for greater liberalization but China ‘reluctant to liberalize beyond what it agreed to at WTO accession’ (Jiang, Citation2008, p. 185). Crucially Australia’s, economy is interdependent with China’s to a greater extent than any other developed country, particularly in terms of agricultural products (Salidjanova, Citation2015, p. 10). China is now Australia’s largest export market for goods and largest trade partner overall. Trade with China is now worth more than Australia’s trade with Japan and the U.S. combined (Chau, Citation2019). Further, this dependence on China is concentrated in politically important sectors, namely, agriculture and energy. China buys more of Australia’s agricultural exports than any other country and by the mid-2010s this was worth $9 billion to Australia. China is also Australia’s top import destination for energy-related products and the agreement eliminates all of Chinese tariffs on Australian these and natural resources (Conifer, Citation2015).

Whilst crucial for Australia, the trade relationship with Australia on the other hand does not have a significant impact on China’s growth (Hoa, Citation2008). Nevertheless, Beijing views Australia as an important regional partner and has attempted to improve relations. In this way, the Chinese hoped that the trade agreement would upgrade relations to the level of a new ‘strategic partnership’ (Song & Yuan, Citation2012, p. 113). When the agreement was concluded, China was Australia’s top destination for exports, worth $60 billion. In 2017, this number was $76 billion, with China remaining the top destination for Australia’s exports. At the same time, Australia has remained China’s 14th most important destination for its exports (IMF, Citation2017). As of April 2017, Australia and China have agreed to hold talks on upgrading the agreement but no schedule for doing so has yet been agreed (Xinhua, Citation2017). Today China is Australia’s top trading partner both in terms of exports and imports, it is the market for nearly 30% of Australia’s exports and the source of 21% of Australia’s imports (World Bank, Citation2018a). As a result, China is a larger recipient of Australian products than Japan, South Korea, the United States and India combined. Iron ore and coal exports to China are worth more than $120 billion and China is Australia’s biggest customer for these resources too (Chau, Citation2019). Overall Australia’s exports to China are worth $144 billion – almost two and a half times that of Japan, Australia’s next largest export destination (Laurenceson & Zhou, Citation2019b). It is estimated that the relationship with China is now worth around 7% of Australian GDP (Laurenceson & Zhou, Citation2019a).

In the agreement with Australia, it can be observed again that there is increasing dependence of the junior partner combined with progressive attempts to expand an initially limited agreement. In terms of utilising this leverage more broadly, in 2018, it has been suggested that that the Chinese government targeted Australian exports of beef, wine, tourism services and higher education in response to political tensions. In 2019, there were also reports of Australian coal shipments to China facing delays at Chinese ports (Laurenceson & Zhou, Citation2019b). It remains to be seen how the negotiations between the two countries develop.

Korea–China FTA (2015)

The agreement with Korea, is the largest agreement, in terms of trade value, concluded by China to date (Wang, Citation2016b, p. 117). Whilst the agreement is more comprehensive than some of China’s other regional agreements, it again remains a relatively shallow FTA in global terms (Wang, Citation2016a, p. 418). In addition to covering the same chapters as other Chinese agreements (trade in goods, services, investment, dispute settlement), the agreement with Korea also contains new chapters on e-commerce, competition and environmental standards (Wang, Citation2016a, p. 418). The agreement is again notable for its gradual approach to coverage – as part of the deal subsequent negotiations were scheduled to start within two years after the entry into force of the agreement. It is not stated in the initial agreement precisely how other chapters will be negotiated, simply that committees under the agreement will play a central role. Crucially, the agreement states that negotiations will be based on new proposals, ‘rather than existing FTA provisions’ (Wang, Citation2016a). Thus whilst the deal with Korea is an improvement in the level of coverage of China’s agreements, it does not seem to represent a shift away from China’s gradualist approach. The agreement instead reflects ‘the piecemeal, gradual, and pragmatic approach of China in upgrading the FTA rules’ (Wang, Citation2016a).

Upon entry into force of the agreement, Korea and China eliminated 50% and 20% of tariff lines, respectively, and within 10 years 79% and 71% of tariff lines, respectively (Schott, Jung, & Cimino-Isaacs, Citation2015, p. 4). Thus, both countries agreed to liberalize a large proportion of their bilateral trade, but there are substantial exceptions. For example, unlike similar agreements between Korea and the U.S., EU or Japan, market access negotiations on services and investment were deferred to subsequent negotiation rounds (Schott et al., Citation2015, p. 1). As a result, it has been suggested that the liberalization entailed by the China–Korea agreement is much more shallow when compared with Korea’s agreements with the EU or U.S. (Wang, Citation2016b, p. 146). For example, in Korea’s agreement with the U.S., the parties agreed to eliminate tariffs on 98.3% and 99.2% of products, respectively, within 10 years. In its agreement with the EU, Korea and the EU agreed to eliminate tariffs on 93.6% and 99.6% of products within five years (Schott et al., Citation2015, p. 5). The agreement with China also fails to establish Most Favoured Nation (MFN) treatment which is common in Korea’s other agreements. Consequently, Korea and China simply agreed to ‘consider’ MFN treatment in their subsequent negotiations, scheduled to be held two years after entry into force of the original agreement. As with China’s other agreements, the original deal with Korea reflects a positive list approach but interestingly, subsequent negotiations on services will be conducted under a negative list approach (similar to that adopted by the U.S. and EU), which means that all sectors will be liberalized unless specifically stated otherwise in the agreement (Schott et al., Citation2015).

The agreement with Korea then, though more detailed than China’s other agreements, confirms China’s gradualist approach to trade and investment liberalization, with some exceptions, liberalization in trade and investment were postponed until the second round of negotiations (Schott et al., Citation2015). As a result, the deal with Korea is expected to have relatively a limited economic impact due to its narrow initial coverage. The final agreement then entails a two-stage negotiation, in which both parties agreed on the coverage of agricultural liberalization in the first stage and other sectors/issues in the second stage. In agreeing to this sequencing, China agreed to protect the Korean agricultural sector from liberalization, in return for excluding Korea’s major export sectors from the agreement (Schott et al., Citation2015). Today China is Korea’s largest market for exports with almost 25% of all exports from Korea destined for China, substantially more than both the U.S. and Japan combined. China is also now the largest source of imports into Korea. Meanwhile Korea is the fourth largest destination for Chinese exports and the number one source for imports into China (World Bank, Citation2018b, Citation2018c). Alongside this growing interdependence, China has begun to utilise its economic leverage with Korea in recent years. When Korea recently installed a U.S. missile defence system, China responded by implementing policies which led to the closure of a substantial number of Korean owned stores in China and also advised businesses to stop sending Chinese tourists to Korea (Das, Citation2017, p. 2). In the case of Korea then we see a gradual negotiating approach combined with increasing interdependence and the utilisation of the economic relationship for broader political objectives by China.

China’s agreements in comparative perspective

To understand the ways in which China’s approach to regional trade agreements is exceptional, it is instructive to compare the regional agreements concluded by other major economic powers in the region, Japan and the United States. First taking the U.S., its strategy has been to employ a comprehensive template when negotiating deals, and as a result its deals cover issues beyond traditional trade areas, such as e-commerce, the environment and labour provisions. However, this can create problems in negotiations, as can be seen in the long-running discussions with Korea that resulted in delayed implementation of the agreement. Similarly, when ASEAN proposed a bilateral agreement, the U.S. signalled ‘that it would not accept a least-common-denominator approach to accommodate ASEAN laggards’ in the way that China has done with respect to ASEAN (Feinberg, Citation2003, p. 1036). In fact, unlike the asymmetrical concessions, we observe from the powerful to the junior partners in Chinese negotiations, it has been suggested that ‘Asymmetric reciprocity has characterised US FTAs: trading partners have had to make more concessions (in mercantilist terms) and remove more trade barriers and investment restrictions’. The U.S. has used its greater bargaining power to set the negotiating agenda and it has been ‘the champion of comprehensive FTAs, going beyond industrial market access…’ (Feinberg, Citation2003, p. 1036)

The other major economic power in the region, Japan has transformed its approach to regional agreements in recent decades – since 1974, it had only concluded a few limited bilateral deals, usually with the U.S., specifically related to a small number of products and sectors (Pempel & Urata, Citation2006, p. 76). Aside from these very narrow agreements, Japan has previously tended to favour multilateral liberalization and has only engaged in bilateral and regional trade agreements partially in reaction to China’s regional initiatives. Japanese officials feared that Japan’s regional influence would be reduced if it was unable to develop an FTA strategy of its own, and of course, trade diversion away from Japan was also a concern following the proliferation of regional trade deals (Ahearn, Citation2005, p. 3). Maintaining its regional trading position was crucial to Japan not just for strategic reasons but also because East Asian countries have traditionally imposed the highest barriers against Japanese exports (Ahearn, Citation2005, p. 3). Though Japan’s regional agreements entail a comparatively high level of liberalization when compared to those of China, exemptions are common. Japan’s agreement with Singapore for example liberalized only 18.8% of agricultural products. Elsewhere, studies have demonstrated that Japan’s agreements result in liberalization of around 94% on imports in terms of import value, but in terms of tariff lines, it is lower than 90%. It is for this reason that the Japanese agreements to be less comprehensive (in terms of liberalization) than those of the U.S but still result in substantially higher liberalization than do China’s agreements. They also tend to cover more issues than do the majority of China’s regional agreements.

As we have seen, China has also tended to adopt a positive list approach which means that only those areas explicitly mentioned in the agreement are covered. This is in contrast to the approach of both Japan and the U.S., who tend to both adopt a negative list (where liberalization occurs unless exemptions are made explicit). In terms of concessions, Japan, like the U.S., has offered few if any up-front concessions to its negotiating partners and has in fact sought to maximize its bargaining leverage as much as possible by, for example, negotiating with individual members of ASEAN before concluding a deal with the organization overall (in contrast to the approach of China). Crucially, for Japan, like the U.S. there have been few significant expansions of its initial agreements.

China’s gradualist approach to trade: implications for the future of the region

What are the implications of China’s gradual approach to the negotiation of regional trade agreements for the Asia Pacific? The analysis highlights a number of important consequences of China’s deals: The first is unsurprising – as a result of the agreements, China’s junior trade partners have become more economically dependent on China and as a result, their bargaining power has declined. Trade with China has become a more significant proportion of their trade and China has become a much more important destination for their exports, but the same cannot be said for China (with the possible partial exception of Korea). Moreover, this trade is also often in politically sensitive sectors such as agriculture and natural resources. In the cases of ASEAN, Pakistan, Australia and New Zealand, this is a particularly noticeable factor. Such a high percentage of exports from these countries to China in these sectors means that political sensitive economic sectors are now dependent on continuing good relations with China because finding alternative markets for these goods would be costly. There is evidence too that China is utilising this dependence to improve its bargaining position over time both with respect to the trade deals themselves (Pakistan, ASEAN) and over issues beyond trade (New Zealand, Korea and Australia). China’s up-front concessions have been crucial in inducing some of its junior partners to conclude a trade deal despite the lack of detail and the vulnerabilities that come with that (this is most obvious in the case of ASEAN and Pakistan). These up-front concessions are also important in accelerating investments and the increased dependence of the partner country upon the China. The concessions induce them (or more precisely producers or importers within the partner state) to make investments because this is often where the highest return and largest market is as a result of the initial agreement. Indeed, we see situations in trade partners are reluctant to expand the agreement further, particularly Indonesia and Pakistan, but China nevertheless pushing for further expansion. We also see these deals linked to broader political issues, as in the cases of Korea, Australia and New Zealand. Such power dynamics are not new, but the relationship between these dynamics and China’s particular approach has not been sufficiently explored in previous analyses.

Once conclusion of the preceding analysis is that, in evaluating the relation between China’s approach and power dynamics, a distinction should be drawn between its increased leverage with respect to the expansion of the deals themselves (what could be termed internal leverage) versus the way in which the agreements increase its leverage in issues beyond trade (external leverage). The cases of Pakistan and ASEAN are good examples of the former, New Zealand, Australia and Korea are increasingly good examples of the latter. To illustrate how China’s gradual approach to regional agreements can increase its internal bargaining leverage we can construct a simple two period scenario where a more powerful rising state, A, offers its weaker counterpart, B, generous terms with respect to B’s export of products to A’s market. These more favourable terms imply that producers of these products in B re-direct their export of these products to A’s market to secure superior returns. These producers may change their behaviour in two ways as a result: first, they can shift production to goods that are in higher demand in country A or they may create more specialized versions of products suited primarily to the market of country A. Thus, firms and producers in country B are induced to make relation-specific investments as a result of the initial trade deal. The economic impact that the collapse of an existing trade deal would have on country B would be severe and the domestic political consequences are potentially even more significant – particularly if the generous terms are directed toward industries that are politically salient in country B, such as agriculture in ASEAN countries, Pakistan, New Zealand and Korea. In this way the producers of country B become hostages to the continuation of the trading relationship between with A and this reduces the exit options of that country. These investments then are important in transforming the relationship between the junior partner and China in allowing the strong, rising partner to gain greater bargaining leverage in future. This dynamic has been neatly summarized elsewhere; a trade agreement will alter ‘[The] smaller state’s self-perception of its own interest: it will converge toward that of the larger. Why? Because the simple act of participation in the arrangement strengthens those who benefit from it relative to those who do not.’ (Kirshner, Citation2003, p. 227).

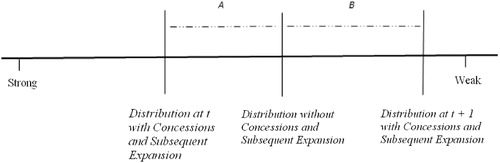

In selecting between a limited agreement that is subsequently expanded (as with China) or a comprehensive deal from the very beginning (like the U.S. or Japan), the most powerful state in a negotiation can decide the best course of action based on its anticipated relative power trajectory. If the rewards that result from up-front concessions and subsequent agreement expansion exceed the benefits of an initially broad agreement, then they will pursue an initially more limited agreement. If not, they will opt for an initially comprehensive agreement that locks-in their advantage. The rewards that derive from subsequent agreement expansion are determined by the difference between the payoffs of bargaining the first period and the second period, this is turn is a function of their power trajectory viz-a-viz their trading partner. Substantively this means that the increased leverage derived from gradual agreement expansion is determined by the change in bargaining power possessed by the strong state from t to t + 1…. The figure below illustrates this logic.

In , the horizontal line represents the share of all possible gains resulting from trade cooperation and each vertical line represents a given distribution. A vertical line at the far right would represent a division such that all benefits accrue to the stronger state, a line at the far left would signify all gains accruing to the relatively weak state. For the strong to be incentivized to pursue a strategy of concession and limited agreements with subsequent expansion in order to maximize internal leverage, distance B must exceed distance A. This means that the gains from expansion exceed the costs of the initial up-front concessions combined with the value of the foregone gains resulting from the narrower agreement in the first round. We see evidence for this most strongly in the agreements with Pakistan and ASEAN. In terms of China’s leverage beyond the negotiation of the trade agreements themselves, the gradual approach to negotiations still presents opportunities for China to hold-out the possibility of favourable revision or expansion when discussing other bilateral issues. If correct, this framework suggests that increased dependence on China and progressively expanded deals have one major implication: That (all else equal) China is going to become increasingly economically and politically dominant in the Asia Pacific and the bargaining power of China’s partners, relative to China will not only decline but will decline at a faster relative rate because they will become progressively more dependent on China, providing China with even greater leverage to extract further concessions over time. These two dynamics will therefore reinforce each other.

The conclusion presented here that China’s gradual approach to regional trade agreements increases its leverage should not be read as a refutation of the importance of economic and political factors driving the selection and design of these agreements, but rather complementary to them. There are, of course, important domestic economic actors shaping trade agreement design (Goldstein & Martin, Citation2000; Hiscox, Citation2002; Naoi, Citation2009) and to these influences should also be added cultural and legal factors driving differences in approach between China and others (Peng, Citation2000; Silbey, Citation2010). The aim here is not to deny this but to introduce a more dynamic evaluation of the leverage arising from China’s approach to largely static existing accounts.

In line with existing accounts, the conclusions outlined here should also not be interpreted as implying a deliberate grand strategy on the part of China. Without access to the highest-level policy discussions such a conclusion would be premature. Though decision making power in China is relatively highly centralized, its foreign policy and trade strategy remain the result of competing domestic and bureaucratic interests. As suggested elsewhere, China’s approach is therefore better understood ‘as the selective application of economic incentives and punishments designed to augment Beijing’s diplomacy’ (Reilly, Citation2013, p. 4). The dynamics highlighted here should be seen then as enhancing our understanding of the incentives driving China’s approach to regional trade cooperation. Though further empirical work is required as the trade relationship between China and its regional partners develops, the theoretical and empirical discussion of this paper serves as a useful framework within which to progress this important discussion.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Duncan Snidal, Walter Mattli, Christina Davis, Karolina Milewicz, Daniel Thomas, Quentin Bruneau, Julia Costa Lopez, and two anonymous reviewers for their valuable insights and comments on versions of this paper. Any errors are the author's own. Research for this article was supported by The Department of Politics and International Relations at the University of Oxford, Balliol College Oxford, The US-UK Fulbright Commission, and the Jane Eliza Procter Fellowship.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Michael Sampson

Dr Michael Sampson is Assistant Professor of International Relations at the Institute of Political Science, Leiden University.

Notes

1 A treaty is defined as unfavourable here either where it is expanded to include sectors in which China has an advantage or where the dependence of the partner far outweighs that of China and this dependence is utilised to exert broader influence.

2 Ba refers to these concessions as ‘sweeteners’.

3 This is in contrast with China’s broader trade in services in the world in which it runs a deficit.

References

- Aggarwal, V., & Urata, S. (2013). Bilateral trade agreements in the Asia-Pacific: Origins, evolution, and implications. London: Routledge.

- Ahearn, R. J. (2005). Japan’s free trade agreement program. Library of congress: Congressional research service. Washingtnon, DC: United States Congress.

- Antkiewicz, A., & Whalley, J. (2005). China’s new regional trade agreements. The World Economy, 28(10), 1539–1557. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9701.2005.00746.x

- Antkiewicz, A., & Whalley, J. (2011). China’s new regional trade agreements. In J. Whalley (Ed.), China’s integration into the world economy (pp. 99–121). Singapore: World Scientific.

- ASEAN Secretariat. (2002). Framework agreement on comprehensive economic co-operation between ASEAN and the People’s Republic of China Phnom Penh, 4 November 2002.

- ASEAN Secretariat. (2006). Protocol to amend the agreement on trade in goods of the framework agreement on comprehensive economic cooperation between the Association of Southeast Asian Nations and the People’s Republic of China. Retrieved from http://www.asean.org/wp-content/uploads/images/2013/economic/afta/ACFTA-ProtocoltoAmendTIG-2006.pdf

- ASEAN Secretariat (2016). ASEAN community in figures. Retrieved from http://www.aseanstats.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/25Content-ACIF.pdf

- Ba, A. D. (2003). China and ASEAN: Renavigating relations for a 21st century Asia. Asian Survey, 43(4), 622. doi:10.1525/as.2003.43.4.622

- Ba, A. D. (2014). Is China leading? China, Southeast Asia and East Asian integration. Political Science, 66(2), 143–165.

- Ballingall, J., & Pambudi, D. (2017). Dairy trade’s economic contribution to New Zealand.

- Barfield, C. (2007). The dragon stirs: China’s trade policy for Asia and the World. Ariz. J. Int’l & Comp. L., 24, 93.

- Bergsten, F. C. (2007). China and economic integration in East Asia: Implications for the United States. Washington D.C.: Peterson Institute for International Economics.

- Blancher, N. R., & Rumbaugh, T. (2004). China: International trade and WTO accession. Washington D.C.: International Monetary Fund.

- Cabrillac, B. (2004). A bilateral trade agreement between Hong Kong and China: CEPA. China Perspectives, 54, 1–12.

- Chau, D. (2019). “Australia’s Fortunes Are Linked to China’s Economy—For Better or Worse.” ABC News. Retrieved from https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-01-15/china-economy-slowdown-will-affect-australia/10716240

- CIA Factbook. (2017). The World Factbook: Pakistan. Retrieved from https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/pk.html

- Coase, R. H. (1937). The nature of the firm. Economica, 4(16), 386–405. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0335.1937.tb00002.x

- Conifer, D. (2015). Australia and China Sign ‘history Making’ Free Trade Agreement after a Decade of Negotiations. ABC News. Retrieved from www.abc.net.au/news/2015-06-17/australia-and-china-sign-free-trade-agreement/6552940

- Cooley, A., & Spruyt, H. (2009). Contracting states: Sovereign transfers in international relations. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Das, D. K. (2014). The role of China in Asia’s evolution to global economic prominence. Asia & The Pacific Policy Studies, 1(1), 216–229. doi:10.1002/app5.10

- Das, S. B. (2017). Southeast Asia worries over growing economic dependence on China. ISEAS Yusof Ishak Institute. Retrieved from http://think-asia.org/bitstream/handle/11540/7648/ISEAS_Perspective_2017_81.pdf?sequence=1

- Dawn. (2017). ‘Breakthrough’ in Sino-Pak FTA Talks. Dawn. Retrieved from www.dawn.com/news/1357937

- Dent, C. M. (2017). East Asian integration: Towards an East Asian economic community (ADBI Working Paper Series).

- DFAT Australian Government. (2018). Macau brief. Retrieved from http://dfat.gov.au/geo/macau/Pages/macau-brief.aspx

- Feinberg, R. E. (2003). The political economy of United States’ free trade arrangements. The World Economy, 26(7), 1019–1040. doi:10.1111/1467-9701.00561

- Financial Express. (2017). China, Pakistan to begin second phase of trade talks next week. Financial Express. Retrieved from http://www.financialexpress.com/world-news/china-pakistan-to-begin-second-phase-of-trade-talks-next-week/848391/

- Goh, E. (2014). The modes of China’s influence: Cases from Southeast Asia. Asian Survey, 54(5), 825–848. doi:10.1525/as.2014.54.5.825

- Goldstein, J., & Martin, L. L. (2000). Legalization, trade liberalization, and domestic politics: A cautionary note. International Organization, 54(3), 603–632. doi:10.1162/002081800551226

- Graham-McLay, C. (2019). New Zealand fears fraying ties with China, its biggest customer. New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/14/world/asia/new-zealand-china-huawei-tensions.html.

- Haider, I. (2015). Details of agreements signed during Xi’s visit to Pakistan. Dawn. Retrieved from www.dawn.com/news/1177129.

- Hepburn, J., et al. (2007). Sustainable development in regional trade and investment agreements: Policy innovations in Asia? (Centre for International Sustainable Development Law (CISDL) Legal Working Paper). Retrieved from http://cisdl.org/public/docs/news/cisdl_studie_asia.pdf

- Hirschman, A. O. (1945). National power and the structure of foreign trade. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Hiscox, M. J. (2002). International trade and political conflict: Commerce, coalitions, and mobility. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Hoa, T. (2008). Australia‐China free trade agreement: Causal empirics and political economy. Economic Papers: A Journal of Applied Economics and Policy, 27(1), 19–29. doi:10.1111/j.1759-3441.2008.tb01023.x