Abstract

What explains the degree of peacetime alliance cohesion? Why do some alliances maintain cohesion regarding common external threats while others do not? I argue that the interaction of allies’ threat-specific time horizons determines whether allies are cohesive or incohesive in deterring common threats. I demonstrate that allies’ behavior towards common threats differs depending on the length of their threat-specific time horizons, which can be categorized as either ‘short’ or ‘long.’ Based on this demonstration, I predict that high alliance cohesion occurs when the lengths of allies’ time horizons are mutually congruent, whereas low alliance cohesion occurs when they are incongruent. To systematically measure allies’ time horizons, I propose a novel typology. To test my argument, I conduct cross-case analyses of peacetime alliance cohesion in the US-Japan and US-ROK alliances over the past two decades in response to the rise of China.

Introduction

States form an alliance primarily to keep peace and deter common threats.Footnote1 As George Liska put it, ‘alliances are against, and only derivatively for, someone or something’ (Liska, Citation1962, p. 12). After an alliance has been formed to counter a common threat, what factors determine the degree of cohesion among alliance members during peacetime?Footnote2 In peacetime, why are some alliances more cohesive and why do they achieve greater consensus regarding the deterrence of a common external threat than others? Answering these questions is crucial for three reasons. First, peacetime alliance cohesion can be an indicator of the reliability of alliance commitments and the credibility of deterrent threats. The tightness of an alliance achieved through costly (ex-ante) military coordination (e.g. integrated military commands, joint military planning, foreign troop deployments through allied consultation) serves as ‘significant sunk-cost signaling’ of allies’ resolve to honor defense commitments/security guarantees and implement deterrent threats against the enemy should war occur (Fearon, Citation1997, pp. 83–85; Schelling, Citation1966). Therefore, functioning as the symbol of the robustness of (extended) deterrence, strong allied solidarity during peacetime would help convince both allies and enemies of the credibility of the alliance. Second, the level of unity among allies during peacetime is a critical factor in determining the alliance’s warfighting capability—the ability to engage in combat effectively (Holsti, Hopmann, & Sullivan, Citation1973, p. 22; Morrow, Citation1991, pp. 272–273). Even if deterrence collapses, the alliance will be able to demonstrate its maximum combined defense capability and readiness through its highly coordinated war aims and joint operational plans. Third, alliance cohesion is highly relevant for alliance durability (Leeds & Savun, Citation2007; Morrow, Citation1991). Basically, the lower the level of alliance cohesion, ceteris paribus, the more likely the alliance is to collapse—for example, the Sino-Soviet alliance, which dissolved in the aftermath of serious intra-alliance conflicts (Lüthi, Citation2008).

This paper, which proposes a novel approach to understanding peacetime alliance cohesion, focuses on allies’ distinct time horizon assessments of a common threat, referred to as threat-specific time horizons. I posit that a state’s time horizon for a threat will be short when the state assesses it as impending, whereas it will be long when the state perceives it as a distant future threat. Based on this premise, I make two predictions: ‘low’ alliance cohesion when allies’ time horizons are ‘incongruent,’ and ‘high’ alliance cohesion when their time horizons are ‘congruent.’ It is important to note that the independent variable in this study is not a specific ally’s threat-specific time horizon categorized as long or short, but rather the congruence or incongruence of time horizons among allies regarding a particular external threat. In essence, this study explores allies’ perception of the urgency of a specific threat and highlights the often-overlooked temporal dimension of threat perception. For example, I predict that if ally A views an enemy’s aggression as a temporally near threat, whereas ally B views it as a temporally remote threat, alliance cohesion will be undermined.

This paper proceeds as follows. First, I examine previous studies of alliance cohesion. Second, I establish a theory of alliance cohesion and flesh out the causal mechanisms on which it is built. Third, I illustrate the utility of my theory by conducting cross-case analyses of the US-Japan and US-ROK alliances. I conclude by briefly discussing the policy implications for contemporary world politics.

Conceptualizing peacetime alliance cohesion

Ole Holsti, P. Terrence Hopmann, and John Sullivan define ‘alliance cohesion’ as ‘the ability of member states to agree on goals, strategy, and tactics, and coordinate activity directed toward those ends’ (Holsti et al., Citation1973, p. 16). Adopting Holsti et al.’s conceptualization, Patricia Weitsman defines alliance cohesion as the ability of allied states to coordinate their goals and specific strategies toward attaining those goals (Weitsman, Citation2004, p. 24). Similarly, Evan Resnick defines alliance cohesion as ‘the extent to which the members of a military alliance resemble a unitary actor in their wartime or peacetime activities’ (Resnick, Citation2013, p. 674). Synthesizing the previous definitions, I define peacetime alliance cohesion as the degree of convergence between allies regarding goals—specifically, the deterrence of common external threats—and the particular strategies that alliance members employ to achieve those goals. With this definition in mind, I offer two operational indicators of peacetime alliance cohesion, which are drawn from Resnick’s definition and operationalization of wartime alliance cohesion (Resnick, Citation2013, p. 674). These indicators include: (1) the extent to which the deterrent target priorities of allies overlap, and (2) the extent to which the specific deterrent strategies of allies coincide. Simply put, alliance cohesion refers to the extent to which allies deter a common threat by responding to it as a unitary actor.

To clarify, this study focuses on peacetime alliance cohesion and not wartime alliance cohesion. The two concepts are closely intertwined, but they need to be distinguished (Weitsman, Citation2004, pp. 31–33). Essentially, alliances serve different purposes in peacetime and in wartime. In peacetime, the main purpose of an alliance is to deter a common enemy, thus preventing war and ensuring the maintenance of the status quo, whereas in wartime it is to defeat the enemy and win a victory through aggregated capabilities.

Literature review

The topic of peacetime alliance cohesion has garnered significant academic attention. Notably, scholars have conducted extensive research on the determinants of alliance cohesion to comprehend its dynamics. An ample literature, including this article, treats external threats as a determinant of alliance cohesion. Extant studies that adopt this threat-based approach can be divided into three variants.

In the first variant, which consists of classic studies that focus on the level of an external threat (Holsti et al., Citation1973; Liska, Citation1962, pp. 97–98), proponents argue that as the external threat increases, alliance cohesion grows. Simply put, proponents believe in a roughly linear relationship between the severity of the threat and the level of alliance cohesion. The second variant focuses on the degree of commonality of an external threat, or the extent to which allies view a particular state as a shared threat to their security (e.g. Liska, Citation1962, p. 129; Rafferty, Citation2003, pp. 352–356). This school predicts that if ally A views a particular state as a threat, whereas ally B does not or no longer does, the resulting lack of commonality will undermine alliance cohesion, as observed in the cases of the Southeast Asian Treaty Organization (SEATO) and the US-Pakistan alliance (Heydarian, Citation2011; Tahir-Kheli, Citation1982, p. 25). The third variant emphasizes the significance of intention in threat perception, building upon Walt’s balance-of-threat theory (Walt, Citation1987). Put simply, when a state perceives offensive or hostile intentions from its adversary, it heightens its perception of the threat. Consequently, one could argue that if ally A views the enemy’s intentions towards it as highly aggressive, ally A will be more inclined to forge a close collaboration with ally B to counter this substantial threat, thereby enhancing alliance cohesion.

While the existing threat-based explanations are convincing, they do not fully grasp the dynamics of peacetime alliance cohesion. Extant threat-based explanations overlook the possibility that allies’ threat perceptions can diverge, depending on the perceived urgency of the same threat. For example, even if ally A and ally B agree that X is an aggressive adversary and that X poses a significant common threat to the alliance, the allies still may have divergent threat perceptions because the urgency of the threat they perceive differs. Consequently, allies may hold contrasting preferences concerning the alliance’s goals and the specific approaches to be taken against the threat. Furthermore, one’s aggressiveness or hostility can sometimes be artificially amplified by another state through selective historical narratives driven by parochial elite interests (Lerner, Citation2020). For instance, in the context of Sino-Japanese relations, following the escalation of the Senkaku/Diaoyu conflict in the early 2010s, Japanese domestic groups actively portrayed China as an ‘irrational or arrogant state that frequently tries to intimidate the weak Japanese state’ (Suzuki, Citation2015, p. 96). In other words, focusing solely on the intention factor can lead to inaccurate interpretations and limit our understanding of the underlying dynamics of threat perception. Exploring the influence of states’ time horizons on threat perceptions can complement and enhance extant threat-based explanations, thereby addressing their theoretical shortcomings.

Challenging extant threat-centric explanations, other scholars assert that the degree of peacetime alliance cohesion is affected by three other variables: the ideology/regime types of allies (Liska, Citation1962, pp. 61–69; Risse-Kappen, Citation1997), the degree of within-alliance institutionalization (Tuschhoff, Citation1999; Wallace, Citation2008), and inter-ally power differentials (Kih, Citation2020; Troutman, Citation2020). However, these non-threat-centric arguments cannot fully explain confusing cross-case variations in alliance cohesion. For example, as detailed below, the US-Japan alliance and the US-Republic of Korea (ROK) alliance share similarities, including political regimes/ideologies, institutionalization levels, and power distributions. Yet, with the rise of China over the last two decades, the former has remained highly cohesive while the latter has become increasingly dissonant. As demonstrated below, the consistently congruent US and Japanese assessments of threat-specific time horizons regarding the rise of China has allowed these allies to enjoy high alliance cohesion. In contrast, increasing differences in US and South Korean assessments of threat-specific time horizons regarding China have produced intensifying rifts within this alliance.

Some scholars have provided case-specific explanations for the cohesion of the US-Japan and US-ROK alliances. Hyun-Wook Kim, for instance, introduced four operational indicators, divided into attitudinal and behavioral factors, to assess the cohesion of the post-Cold War US-Japan alliance (Kim, Citation2011). However, Kim’s study does not explain the causal mechanism that determines alliance cohesion. This is so because he assumes that both attitudinal and behavioral factors consistently serve as operational indicators for alliance cohesion—that is, he does not recognize that these factors play different roles. To address this gap, I propose a new causal mechanism in which the attitudinal factor is the independent variable and the behavioral factor serves as an indicator for the level of alliance cohesion, which in this study is the dependent variable.Footnote3 Jae Jeok Park and Sang Bok Moon’s study convincingly explains the cohesion of the US-Japan and US-ROK alliances, focusing on the functional aspect of alliance operation (Park & Moon, Citation2014). They demonstrate that both liberal and conservative governments in Japan and South Korea are motivated to maintain a US-led regional order in the Asia-Pacific that benefits both allies. However, their study does not satisfactorily explain why South Korea has hesitated to closely collaborate with the US to counter China’s rise, despite the fact that for the past two decades, China has posed a significant challenge to the US-led regional order. To address the limitations of existing research, this article explores overlooked temporal dynamics related to allied threat perceptions.

The argument

Definition and determinants of time horizons

Before developing specific propositions and causal logics, I clarify the definition of the term ‘time horizons.’ In contrast to economists and psychologists, international relations scholars have paid little attention to the concept and its function (Streich & Levy, Citation2007). Only recently, scholars have begun to apply time horizons to international politics and analyze the intertemporal dynamics of the behaviors of international actors. A handful of studies have found that in the international arena, the distinct time horizons of individuals and states influence foreign policy decision-making and strategic interactions between states (e.g. Edelstein, Citation2017; Krebs & Rapport, Citation2012; Kreps, Citation2011). Sarah Kreps defines ‘time horizons’ as ‘the way actors value the future relative to the present, or the period of time that actors take into account when making decisions’ (Kreps, Citation2011, p. 29). According to David Edelstein, the term describes ‘the value that [a] leader [or a state] places on present as opposed to future payoffs, or, as it is often called, the rate of intertemporal discounting’ (Edelstein, Citation2017, p. 5). I define time horizons as the temporal distance from a specific threat perceived by states. In other words, the term refers to a state’s assessment of how much time is left before an external threat becomes manifest through actual military aggression. Consequently, the unit of analysis in this study is a state’s time horizons rather than those of an individual leader.

Table 1. Typology of temporal distance from threats and time horizon outcome.

However, the measurement of time horizons has obstructed explorations of their role in international politics. Previous efforts have focused on a variety of factors thought to be determinants of time horizons, including a leader’s inherited/inborn attributes, age, the duration of his or her tenure, and a state’s political regime type (e.g. Olson, Citation1993; pp. 135–178; Horowitz, McDermott, & Stam, Citation2005, pp. 667–669). Yet in these cases, the causal distance between previously explored proxies for time horizons and states’ actions in the international arena has arguably been too long. Consequently, states’ behaviors during these long temporal gaps could be influenced by many other confounders. To overcome the limitations of these approaches, I instead focus on the perceptual temporal distance from a given threat posed to a state’s security. Given that survival is one of their primary concerns, states pay close attention to security issues—especially when the external security environment is severe. Simultaneously, in the anarchic international structure, states are exposed to external threats to varying degrees. Some states occupy a more acute and severe security environment than others. The universal but heterogenous features embedded in external threats have encouraged scholars to measure threat severity systematically, and this has resulted in quantified datasets such as the International Crisis Behavior (ICB) dataset).Footnote4 Accordingly, my study focuses on the perceived temporal distance from an external threat and posits that the length of a state’s assessment of the time horizon of a threat is a function of that state’s judgment about the temporal duration allowed for it to take measures to deter that threat and ensure national security. As David Edelstein highlights, ‘threats themselves unfold over different time horizons’ (Edelstein, Citation2020, p. 394). In other words, from the viewpoint of states, ‘some threats are more immediate and certain, while others are more long term and uncertain’ (ibid.). Consequently, when a temporal distance from an external threat is short, a state will be time-pressured about the threat. In contrast, when a temporal distance from an external threat is long, a state will be time-relaxed about the threat.

Goal setting

Once an alliance is formed, fellow allied states should repeatedly attempt to coordinate their opinions on the following two fronts: 1) common goals; and 2) specific strategies needed to attain the shared goals. As clarified above, alliance cohesion refers to allies’ ability to reach agreement on these two fronts. To theorize about how one’s time horizon—determined by the perceptual temporal distance to an external threat—ends up determining alliance cohesion, we should identify how threat-specific time horizons affect states’ behaviors in terms of ‘goal setting’ and ‘the establishment of specific strategies’ to achieve shared objectives.

When it comes to goal setting, the first and foremost goal of an alliance is to deter a mutual short-term threat (Morrow, Citation1991, p. 926–927). Therefore, an ally generally prefers to prioritize goals for deterring common impending threats over those associated with distant future threats (e.g. forestalling unfavorable transitions in the balance of power). When allies have congruent external threat time horizons, they should more easily coordinate the order of goal-setting priorities. When time horizons among allies are incongruent, however, those allies are likely to be at odds with each other. Thus, they should come into conflict over which external threat should be the top priority, and, thus, their primary target of deterrence. A time-pressured ally would believe that a common threat would soon materialize and develop into actual aggression. Therefore, the ally with short time horizons would attempt to designate the alleviation of the immediate threat as the alliance’s top security task. Conversely, a time-relaxed ally would discount the urgency of countering a seemingly remote threat. Instead, the ally with long time horizons would expect the alliance to mainly target its own other proximate threats.

In the case of bilateral alliances, for instance, when two allies have congruent time horizons concerning the same threat, they could easily coordinate their positions when prioritizing alliance objectives. For example, if both allies conclude that a certain external enemy’s increasing assertiveness will soon translate into actual aggression, they will share symmetric short time horizons regarding that common threat. Consequently, both time-pressured allies will easily agree to designate deterring the adversary as their first-priority goal, putting distant future threats aside.

Establishing specific strategies

Even if allies concur that deterring a particular enemy is the most urgent goal, they may disagree about how to achieve that goal—that is, what specific strategies/defense plans should be formulated and executed to attain the alliance’s objectives. The essence of deterrence is to convince an enemy that it will not win a quick and inexpensive victory against a target state (Mearsheimer, Citation1985). As Patrick Morgan puts it, ‘deterrence and defense are analytically distinct but thoroughly interrelated in practice’ (Morgan, Citation1977, p. 30). Within the context of an alliance, a highly coordinated joint defense planning and a solid combined defense readiness against enemy attacks pave the way for a robust deterrence of the common enemy. Generally, alliance treaties entail continued negotiations over the establishment of joint war plans in military contingencies (Poast, Citation2019). This implies that, among allies, the preferred way of deterring a common enemy may differ depending on the length of the threat-specific time horizons of the various allied parties.

For a time-pressured ally, the best deterrent posture is to employ a forward defense to prevent enemy troops from penetrating into the allied territories, ‘stopping an offensive before it makes any headway’ (Mearsheimer, Citation1981, p. 105). Specifically, a time-pressured ally will want to place pre-positioned robust joint allied troops on high alert along the impending enemy’s likely invasion routes. Substantial forward-deployed troops will retard the enemy troops’ quick advances and trigger the mobilization of reinforcements from day one of war (Schelling, Citation1960, p. 119; Citation1966, p. 47, p. 99). Simply put, a substantial forward military presence with high-military readiness will function as credible evidence of the alliance’s strong political willingness and military capability to deter and, if necessary, defeat the enemy (Lee Citation2021, pp. 769–771).

In contrast, an ally with long time horizons will prefer a more relaxed and moderate deterrent force posture. An excessive and rash deterrent posture against a distant future threat could provoke the adversary, triggering an inadvertent and unnecessary escalation of conflict. Such overreacted deterrence, therefore, could advance the development of a potential threat into an actual conflict. Moreover, for a time-relaxed ally, a bolt-from-the-blue attack by the potential enemy would seem unlikely in the near future. Even if tensions flare up between the opposing sides, the alliance will have sufficient time to brace for the enemy’s attack. In other words, even after the outbreak of military crisis, time is expected to remain on the alliance’s side. For these reasons, an ally with long time horizons will not want to preposition substantial troops on the potential enemy’s doorstep because it could ignite a stronger backlash by the enemy and lead to a destabilizing escalation of conflict.

In summary, when threat-specific time horizons among allies are congruent, allied states will find it easier to reach an agreement about how to deter and defeat enemies. In contrast, when allies’ time horizons are incongruent, this will not occur, causing allies to experience frequent intra-alliance conflicts.

Measurement

Drawing on insights provided in studies by Thomas Christensen and Sarah Kreps, I propose a simple method to measure a state’s length of time horizons. Christensen creates a novel typology to illustrate how easily leading elites can mobilize domestic support for foreign policies, depending on ‘the directness of [external] threat’ posed to the leading group (Christensen, Citation1996, p. 27). More specifically, he proposes three measures of the directness of an external threat. First, is the target of the threat (challenge): Who faces the gravest threat from the adversary, and, therefore, who is the most likely target of the enemy’s aggression—the homeland, allies (both formally and informally), or nonaligned states? Second, is the time frame of the threat: When is the external threat expected to damage national security in earnest—in an immediate future, short-term future, or long-term future? Third, what is the type of the threat: During peacetime, is a given threat military, political, or economic in nature (ibid.)?

Kreps adopts and modifies Christensen’s typology to measure a state’s time horizons (Kreps, Citation2011, pp. 30–31). She posits that the more direct an external threat is to a state, the shorter its time horizons are, whereas the more abstract a threat is to the state, the longer its time horizons are (ibid., p. 175). Tweaking Kreps’s modified model, I develop a typology of perceptual temporal distance from an external threat, which is assumed to determine a state’s threat-specific time horizon. A shortcoming of the work by Christensen and Kreps is that neither attempts to quantify Christensen’s typology. To improve the applicability and replicability of the typology, I add a simple three-scale rating to the Kreps’s measurement of time horizons. The typology below presents my quantified measures of a state’s assessed temporal distance from a threat, which ultimately shapes that state’s time horizons (see above).

To illustrate, when the temporal distance from a specific threat is assessed as ‘short,’ it scores ‘3′; in the case of ‘medium,’ it scores ‘2′; in the case of ‘long,’ it scores ‘1.’ I code a state’s specific threat time horizon as short when the combined score of the three measures falls within the range of ‘7 to 9.’ A state’s assessed time horizon of that threat is coded as long when the combined value falls within the range of ‘3 to 6.’ The independent variable of this study is whether threat-specific time horizons among allies are congruent—either a ‘short-short’ or a ‘long-long’ dyad—or incongruent. To reiterate, the congruent case leads to high alliance cohesion, whereas the incongruent case leads to low alliance cohesion.

Methods and case selection

To illustrate the plausibility of my argument, I examine US-Japan and the US-ROK alliances from the early 2000s—the starting point of China’s rise—through today (Ross, Citation2019, pp. 309–312). That is, I explore the US’s defensive alliances in East Asia.Footnote5 Exploring these cases allows me to test whether my argument can account for cross-case variation in alliance cohesion during a given period. In addition, the two alliances are arguably the ‘most similar cases’ among the US alliances (Seawright & Gerring, Citation2008, pp. 304–306). That is, the two East Asian allies resemble each other in terms of the threat environment, political ideology, military power, and economic size. However, during the examined period, there have been stark differences in the allies’ assessments of the Chinese threat.

By examining these cases while controlling for other influential variables and unobserved confounders, we can observe how the contrasting time horizon assessments of the same security threat (China) by the East Asian allies have disparately affected their ties with the same alliance partner (the US). Furthermore, the US-ROK alliance case defies the predictions of the confounders mentioned above, such as ideological similarities between allies, the degree of within-alliance institutionalization, and inter-ally power differentials, thus enabling the maximization of the ‘experimental variance’ (Peters, Citation2013, p. 31).

Case studies

The US and japan’s time horizons for a Chinese threat

Time-pressured US

Since the early 2000s, the US’s time horizons for the Chinese threat have gradually shortened as China has emerged as a peer competitor in Asia. China’s rapidly expanding economic power has facilitated its sharply intensifying military power. Between 2000 and 2022, the annual growth rate of China’s announced defense budget ranged between 6.6% and 17.8% (GlobalSecurity.org, n.d.). Rapid economic and military growth, coupled with heightened nationalism, fueled China’s assertive rhetoric and hostile actions. In particular, starting in the early 2010s, China rapidly expanded its maritime presence in the East and South China Sea, triggering a series of military collisions and tensions with regional countries (Hughes, Citation2011; Yahuda, Citation2013).

Starting in the mid-2000s, the US’s growing concerns about China’s aggrandizement led to a substantive US reorientation or rebalance toward Asia (Silove, Citation2016). During the Trump administration, this evolved into all-encompassing efforts to contain China. While the Obama administration sought to find a modus operandi for US-China relations, the Trump administration turned to confrontation, demonstrating a shift towards a more assertive US policy. For example, President Trump stated that ‘Obviously, China is a threat to the world in a sense, because they’re building a military faster than anybody’ (Rappeport, Citation2019). Former Vice President Mike Pence even ‘delivered a de-facto declaration of cold war against China’ (Allison, Citation2018). Importantly, the heightened threat perception of American leaders toward China did not derive merely from China’s rapidly growing economic and military power. More precisely, American leaders’ anxiety derived from the recognition that ‘time is no longer on their side,’ leading them to feel compelled to act now to address the impending threat (Medeiros, Citation2019, p. 93).

The short time horizons established by the Trump administration for Chinese threats have continued into the Biden administration, constituting rare common ground between the two administrations. Issuing an order to establish a China task force as quickly as possible, President Biden indicated that countering China is the administration’s top-priority and most urgent issue (Seligman, Citation2021). In his senate confirmation hearing, then-Defense Secretary nominee Lloyd Austin testified that ‘the Pentagon and the Department of Defense view China as our primary pacing challenge’ (Austin, Citation2021). In addition, Secretary of State Anthony Blinken warned that China had made a ‘fundamental decision that the status quo was no longer acceptable, and that Beijing was determined to pursue reunification on a much faster timeline [emphasis added]’(Marlow, Citation2022). In short, over the last two decades, the US time horizons for China’s rise have shortened, leading to Washington’s current short time horizon assessment of Beijing’s menace. This point is substantiated by the three measures of the temporal distance from an external threat.

First, regarding the main target of the threat, American leaders believe that China’s hostilities are primarily targeted at US-friendly states in the Indo-Pacific, such as Australia, India, Japan, and Taiwan. China is currently involved in a number of territorial disputes with the US’s regional allies and strategic partners. Moreover, ‘the most immediate role’ for China’s growing military is ‘regional, which means direct defense of China and domination of the surrounding area’ (Bandow, Citation2020). Accordingly, from the US perspective, the main targets of Chinese threats are its allies in the Indo-Pacific.

Second, regarding the time frame of the threat, it would be correct to view China’s growing aggressiveness towards the regional friendly nations as an emerging short-term threat. US leadership has watched China’s recent territorial aggrandizement with deep concern. Washington has remained vigilant about Beijing’s possible aggression against US-friendly nations in the Indo-Pacific into the foreseeable future. Such a grim assessment mainly derives from the fact that ‘the military balance in the Indo-Pacific is becoming more unfavorable’ for the US and its regional friendly nations, which has promoted Beijing’s adventurism and miscalculation (Seldin, Citation2021). In other words, Washington has evaluated very seriously the possibility that the self-reliant deterrence of regional allies against Beijing could collapse in the next few years (Inhofe & Reed, Citation2020). For example, Adm. Philip Davidson, then-Commander of the US Indo-Pacific Command, testified that ‘Taiwan is clearly one of their [China’s] ambitions. … And I think the threat is manifest during this decade, in fact, in the next six years’ (Seligman, Citation2021, emphasis added). In sum, it would be accurate to say that in Washington’s eyes, security challenges posed by China are a short-term threat to the US’s regional allies and partners—but they are short of the ‘immediate’ threshold (that is, not today or in the next couple of months).

Third, overall, it is evident that since the rise of China, Chinese threats have been perceived by the US as both military threats and an economic and political menace. China’s rise certainly poses a growing challenge to the US’s long-standing global economic and technological hegemony (Medeiros, Citation2019). Yet over time, America’s assessment of the military threat presented by China has become considerably more pronounced. This is exemplified by the 2006 US Department of Defense [DOD] report, which suggests that China’s considerable military improvements ‘have the potential to pose credible threats to modern militaries operating in the region’ (US Department of Defense, Citation2006, p. I). Recent American tabletop wargames have revealed that in an armed conflict over Taiwan, the US would emerge victorious against China, albeit at a substantial cost (Lendon & Liebermann, Citation2023). These results support Washington’s contention that China currently poses a significant military threat to the informal ally. In summary, the combined score of the three measures is ‘7′ (=2 + 2 + 3), indicating the US’s assessed time horizons for Chinese threats have been short.

Time-pressured Japan

Tokyo in recent decades has grown more vocal as China’s military has made incursions around islands administered by Japan in the East China Sea—islands known as Senkaku in Japan and as Diaoyu in China. In 2012, the maritime dispute escalated in earnest when the Japanese government announced the nationalization of the disputed islands by purchasing them from their Japanese private owner. Warning Japan not to purchase the islands, China sent out two patrol ships to reassert its claim (Takenaka, Citation2012). Since then, China’s coast guard ships and civilian fishing vessels have frequently entered Japan’s contiguous zone. Furthermore, they have sometimes intruded into Japan’s territorial waters surrounding the disputed islands, threatening Japan’s territorial integrity (Japan MOFA, Citation2021, p. 17). In response, Tokyo went to considerable lengths to bolster its surveillance and observation capabilities in the disputed areas and to increase the combat readiness of its Self-Defense Force (SDF) against China’s maritime aggression (BBC, Citation2014; Cavas, Citation2016).

During the Cold War, Japan viewed a possible Soviet invasion of Japan’s main islands (especially Hokkaido) as a main short-term threat to its territorial integrity (Robertson, Citation1988, p. 106; Lind, Citation2004, pp. 106–108). In contrast, during most of the same period, Tokyo did not perceive a Chinese invasion of its territories as a proximate threat (Dian, Citation2014, pp. 76–77; Oren & Brummer, Citation2020, p. 79). Japan’s relaxed time horizon assessment of the China matter began to shorten in the mid-2000s. For example, in 2005, the Japanese foreign minister, Taro Aso, described China as a ‘neighboring country with … military spending that has shown double-digit growth for the last 17 years, with extremely little transparency…. It’s [China is] becoming a considerable threat’ (Onishi, Citation2005). Echoing his statement, Japan’s 2007 Defense White Paper warned that ‘China is accelerating the modernization of its military forces’ (Pilling, Citation2007). Especially since the early-2010s, Japan’s perceived temporal distance from a Chinese threat has decreased significantly as China’s incursion into Japan’s territorial waters have increased dramatically (Kim & Simón, Citation2021, p. 20). In 2020 Japan’s former Defense Minister, Kono Taro, noted that ‘right now, what’s happening in East China Sea, our fighter jets scramble against Chinese airplanes almost every day…Their ships, with guns, are trying to violate our territorial waters constantly…’ (Long, Citation2020). In short, like the US, Japan has been time-pressured in its perception of the Chinese threat.

Japan’s short time horizon assessment of the China matter is corroborated by the three-fold quantified measurement I suggested above. First, in terms of a main target of threat, Japanese leaders have believed that their own territories in the East China Sea (and not those of their allies or third-party states) have been a primary target of a Chinese threat. Japan’s 2013 Defense White Paper, for example, assessed that China’s rapidly expanding military capabilities were being embodied as the adversary’s ‘intrusion into Japan’s territorial waters, its violation of Japan’s airspace, and even dangerous actions that could cause a contingency situation’ much more frequently than in previous years (Japan Ministry of Defense [MOD], 2013, p. 46).

Second, in terms of the time frame, over the last two decades, the Japanese government has enhanced military readiness in the East China Sea because it has assumed that a Chinese threat could soon translate into an actual attempt to take over of the disputed Senkaku Islands militarily (Kyodo News, Citation2021). Given that Tokyo has ramped up its patrol and surveillance capabilities to brace for such an emerging scenario, it would be rational to code Japan’s time frame regarding a Chinese threat as short-term (Japan MOD, Citation2016, pp. 5–10).

Third, regarding the type of threat (and as demonstrated above), Japanese leaders have been alarmed by China’s rapidly intensifying military capabilities, which could be exploited to attack Senkakus (Onishi, Citation2005). China’s continuous military arms build-up and saber-rattling in the East China Sea has convinced Japan that China constitutes a military threat. Admittedly, Japan’s apprehensions about the rise of China have been multidimensional: Japan also has been anxious about challenges from China in the political and economic realms (Hughes, Citation2009, pp. 840–841). Nonetheless, Tokyo’s concerns about China’s growing political and economic strengths have been increasingly outweighed by concerns about its military (ibid.).

To sum up, the combined score of the quantified measurement from the three aspects is ‘8′ (=3 + 2 + 3). This suggests that since the mid-2000s, Japan’s time horizon assessment of the China matter, like that of the US, has been short.

End Results: high alliance cohesion of the US-Japan alliance

Goal setting

The US and Japan have regarded deterring China as the alliance’s top-priority task. That said, both the US and Japan have been exposed to threats from North Korea (e.g. nuclear saber-rattling, ballistic missile test-firings) and Russia (military provocations in Eastern Europe and Northeast Asia). Nevertheless, both allies have agreed that a Chinese threat is their common most urgent security issue. The two allies, therefore, adopted an alliance objective to willingly counter a Chinese threat in a broad region beyond the Japanese territories. For example, endorsing the George W. Bush administration’s concern about China’s rise, the Japanese government agreed to accept maintaining the status quo between China and Taiwan as the alliance’s ‘common strategic objective’ (Faiola, Citation2005). Similarly, in a joint US-Japan press conference, President Barack Obama and Prime Minister Shinzo Abe stated: ‘With regard to China, based on the rule of law, a free and open Asia Pacific region will be developed and we would try to engage China in this region. And we agreed to cooperate toward this end’ (The White House, Citation2014). Prime Minister Abe added that ‘[c]hanges of the status quo based on intimidation and coercion will not be condoned. We want to make this a peaceful region which values laws, and in doing this strengthening of our bilateral alliance is extremely important. On this point, I fully trust President Obama’ (ibid.).

Recently, the alliance’s common top-priority objective—to counter China—has been reflected in the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD). Notably, the US and Japan have together taken the lead in establishing the minilateral security arrangement. Back in 2007, then-Japanese Prime Minister Abe proposed the QUAD as a means of encircling China with an ‘arc of democracies’ composed of the US, Japan, Australia, and India (Lintner, Citation2020). In 2017, the Trump administration reinvigorated the incomplete defense initiative as a bulwark against Chinese aggrandizement in the Indo-Pacific, culminating in the first QUAD summit meeting held in March 2021 (Lendon & Wang, Citation2021).

Moreover, at the recent 2 + 2 meeting between the American Secretaries of State and Defense and their Japanese counterparts, the two sides jointly announced that: ‘We’re united in the vision of a free and open Indo-Pacific region, … we will push back if necessary when China uses coercion or aggression to get its way’ (US Department of State, Citation2021). Simultaneously, the US reaffirmed that Article V of the US-Japan security treaty would apply to the protection of the Senkaku Islands. Simply put, they together pledged to pursue the common goal—to deter China’s ‘aggressive and coercive behaviors’ in the Indo-Pacific region (ibid.). In short, based on congruent short time horizon assessments of a Chinese threat, both sides have closely coordinated their opinions. As a result, the two allies have set their first-priority aim—to deter China’s adventurism in peacetime—easily and without serious disagreement.

Establishment of specific strategies

In addition, the US and Japan have successfully coordinated their deterrent force postures to attain the alliance’s most urgent goal: deterring China. The US has stationed rapid response capabilities in US military bases in the Japanese Archipelago. Importantly, most of the US troops stationed in Japan are prepositioned in Okinawa, adjacent to the potential flash points—Senkaku/Diaoyu—between Japan and China. Specifically, as of 2018, 70.4% of US troops stationed in Japan were in Okinawa, ‘which comprises less than 1% of Japan’s total land area’ (Chanlett-Avery & Rinehart, Citation2016, p. 10; Okinawa Prefectural Government, Citation2018, p. 6). The substantial forward-deployed American troops would function as rapid reaction and strike units against China’s invading troops in the event of war. The US forward presence is charged with curbing China’s adventurism by demonstrating that the US, on behalf of Japan, already has sufficient military capabilities to foil any attempt by China to quickly capture the disputed islands. Moreover, between 2004 and 2012, the US gradually beefed up its marine presence in Okinawa in order to offset China’s growing power projection capabilities over the disputed islands. Consequently, in 2012, the total number of US marines deployed in Okinawa reached 19,000 (Tritten, Citation2012). In short, the US has adopted a forward-defense strategy to deter the short-term threat in the region.

Meanwhile, in coordination with the US, Japan has taken similar steps to deter China. Initially, Japan’s deterrent posture was based on ‘the Basic Defense Force’ concept that had governed Japan’s defense strategy since 1976. Grounded in the assumption that a Soviet invasion was the main threat to Japan, the static Basic Defense Force (BDF) concept hinged on the deployment of ‘a large number of heavy weapons and infantry uniformly across the main islands in order to deter an outright [Soviet] invasion’ of Japan’s main islands from north (Hokkaido) to south (Kyushu) (Fouse, Citation2011, p. 4). When the Japanese government released the new National Defense Program Guidelines (NDPG) in 2010, the BDF concept was officially replaced by a ‘Dynamic Defense Force’ that possesses ‘readiness, mobility, flexibility, sustainability, and versatility, and is reinforced by advanced military technology … and intelligence capabilities’ (Japan MOD, Citation2012, p. 115). Subsequently, Tokyo endorsed the notion of a ‘Dynamic Joint Defense Force’ and ‘Multi-Domain Defense Force’ to enhance deterrence mainly targeted at an evolving Chinese threat (Japan MOD, Citation2019, 208–210).

To this end, Japan has stressed ‘increasing its visibility in the southern islands through improved intelligence, reconnaissance and surveillance (ISR) capabilities…by developing a more mobile and flexible force structure that is better coordinated for a timely response’ (Fouse, Citation2011, p. 3). Prioritizing deterrence against China, Japan has made efforts to enhance its defense and rapid reaction capabilities in the forward area. The objective is to protect its remote islands from potential aggression by China. To illustrate, Japan has recently constructed missile batteries and radar facilities on remote islands like Miyako, Amami Oshima, and Yonaguni, establishing the so-called ‘southwestern wall’ (Denyer, Citation2019). This shift towards a forward-oriented deterrent approach by Japan aligns with US movements in the region, including the establishment of a US Marine Littoral Regiment in Okinawa (Gould, Citation2023). Furthermore, Japan recently announced its intention to acquire significant counterstrike capabilities (Cooper & Sayers, Citation2023), including the pursuit of hundreds of US-built Tomahawk cruise missiles, which would allow it to target military sites on mainland China (Lee & Nakashima, Citation2022).

In conclusion, over the past two decades, the US and Japan have successfully coordinated their stances both in terms of alliance objectives and specific strategies needed to counter China’s rise. Consequently, the two allies have demonstrated strong solidarity, deterring the common threat as a unitary actor.

South Korea’s time horizon assessment of a Chinese threat

Time-relaxed South Korea

South Korea has viewed North Korea as a proximate and the most direct threat to its national security, although South Korean authorities have believed that a North Korean invasion would not happen overnight. In particular, South Korea’s conservative politicians and media outlets have expressed concern that North Korea could launch nuclear attacks against their country at any time in the near future. Even some South Korean conservative politicians have argued that US tactical nuclear weapons should be reintroduced to South Korea to discourage the North’s possible aggression (Gallo, Citation2021). Contrasting with this active response to North Korea, South Korea has remained aloof from US efforts to contain China, maintaining a low-key position to avoid antagonizing its large neighbor (Lind & Press, Citation2021, p. 366). From Seoul’s perspective, the need to deal with the Chinese threat has not been urgent.

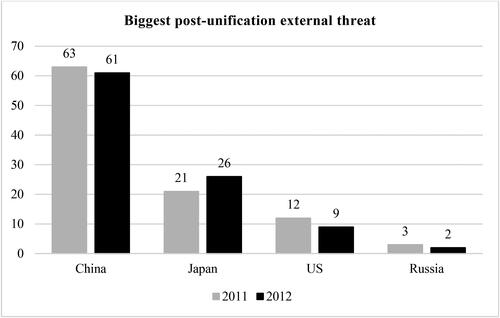

South Korean society widely shares a relaxed attitude towards the perceived threat from China. In surveys conducted in 2011 and 2012, 63% and 61% of respondents, respectively, believed that China would become the biggest threat to a unified Korea in the future (The Asan Institute for Policy Studies, Citation2012) (see below). Similarly, in a 2021 survey, 46% of South Korean respondents viewed North Korea as the primary current threat to South Korea, while 33% considered China to be the most significant current threat (Dalton, Friedhoff, & Kim, Citation2022, p. 12). However, when asked about the threat landscape in 10 years, 56% anticipated that China would pose the most significant threat, while only 22% predicted it would be North Korea. In summary, South Korea, unlike the US, views China’s rise as a long-term threat rather than an immediate concern.

This point is further corroborated by the three-fold measurement described above. First, regarding the main target of the threat, Seoul has believed that the main objects of Beijing’s menace are Japan, Taiwan, India, and Southeast Asian countries involved in territorial disputes with China; all are non-aligned Asian countries with which Seoul has had neither formal nor informal allied relationships.Footnote6 Thus, Seoul has been reluctant to demonstrate a clear position about regional territorial disputes between China and these countries (Lee, Citation2016).

Second, regarding the time frame of the threat, Seoul believes that Beijing is unlikely to employ its formidable military force to directly attack its forces or territory in the foreseeable future. Importantly, there is no land border shared between South Korea and China. Consequently, the military forces of South Korea do not directly encounter Chinese forces along the coterminous border, thereby decreasing the probability of engaging in armed conflicts with China. Furthermore, unlike Japan, South Korea has not experienced any specific territorial disputes or direct military confrontations with China for the past several decades—i.e. since South Korea normalized diplomatic relations with China in 1992. While China has intruded into the South Korean Air Defense Identification Zone dozens of times every year since 2016, it has never violated the ROK’s airspace (Trent, Citation2020). Remarkably, China’s consistent de-escalatory stance in the Yellow Sea has since 2010 been starkly different from its greatly assertive stance in the East China Sea (Luo, Citation2022). When asked about China’s assertiveness in recent years, former South Korean Foreign Minister Chung Eui-yong responded, ‘I don’t know whether we should call it assertive or not’ (Council on Foreign Relations, Citation2021). In short, South Korea has discounted the urgency of Chinese armed attacks against its troops and territory. This assessment has shaped Seoul’s long-term perspective on the Chinese threat.

Finally, regarding the type of threat, before the outbreak of the THAAD (Terminal High Altitude Area Defense) dispute in 2016, both conservative and liberal ROK administrations had viewed China as a significant economic partner and a competitor. However, until recently, South Korean governments did not perceive China as an explicit political or military threat to their security. To elucidate, China has been South Korea’s largest trading partner and the biggest foreign market of ROK-produced end-products, components, and equipment. On the other hand, China’s rapid economic growth and the sophistication of its industrial structure have positioned it as a major competitor for South Korea in various industrial sectors, such as semiconductors, batteries, and smartphones—sectors where Seoul had previously held a leading position (Gibbs, Citation2014; Mozur, Citation2015). As succinctly summarized by a South Korean economist, ‘our biggest customer [China] has become our competitor’ (Harris, Citation2018). As such, an increase in China’s global market share leads to a decline in the ROK’s global share of industrial sectors. Moreover, the ROK’s growing economic interdependence with China increases South Korea’s vulnerability to a possible weaponization of economic interdependence by China.

The THAAD dispute was a turning point in South Korea’s perception of the Chinese threat. China’s strong opposition to and retaliatory measures against South Korea’s decision to deploy the THAAD system on its soil, which Seoul argued was a defensive measure against the North Korean nuclear missile threat, were perceived as indications of China’s growing assertiveness, fueled by its rapid military expansion (Yonhap News, Citation2021; You, Citation2022). Furthermore, amid the growing tensions in the Taiwan Strait, South Korea’s 2022 Defense White Paper expressed concerns about the issue for the first time, assessing that China’s increasing muscle-flexing toward Taiwan ‘raised security concerns not only in Taiwan but also in Japan and other countries in the region’ (ROK MOD, Citation2022, p. 17). Regarding China’s growing military pressure on Taiwan, South Korean president Yoon Suk Yeol recently targeted China, declaring in an interview that, ‘[a]fter all, these tensions occurred because of the attempts to change the status quo by force, and we together with the international community absolutely oppose such a change’ (Kim, Park, & Shin, Citation2023). In short, it seems that in recent years, South Korea has come to recognize China as both an economic threat to its country and a military threat to the region.

In summary, the combined South Korean score as measured by the three measures of the temporal distance from a Chinese threat shifted from ‘3′ (=1 + 1 + 1) to ‘5′ (=1 + 1 + 3), remaining in the range of a ‘long’ time horizon. Seoul has consistently been time-relaxed about China, which starkly contrasts with Washington’s time-pressured stance towards it.

End Results: low alliance cohesion of the US-ROK alliance

Goal setting

An incongruency of time horizons between the US and South Korea has prevented these countries from forming a united and cohesive front against the regional challenge. With regards to goal setting, the US has revealed its wish to expand the US-ROK alliance—traditionally targeted at North Korea—to a regional security alliance that would also check China’s growing assertiveness in the Indo-Pacific. For example, when he congratulated Park Geun-hye for her victory in the 2012 South Korean presidential election, President Obama stated that the US-ROK alliance ‘serves as a linchpin of peace and security in the Asia Pacific’ (The White House, Citation2012). In 2019, referencing President Moon’s visit to the US, President Trump’s White House issued a statement that the US-ROK alliance is ‘the linchpin of peace and security on the Korean Peninsula and in the region’ (Smith & Shin, Citation2019, emphasis added). Making the same point, but more bluntly, Defense Secretary Austin in a joint press conference with his South Korean counterpart stated that ‘it [the US-ROK alliance] is the linchpin of peace, security and prosperity for Northeast Asia, a free and open Indo-Pacific region and across the world’ (US Department of Defense, Citation2021). Simply put, Washington has increasingly pushed Seoul to assume a more active role in countering China and has gone to great lengths to transform the alliance into a core component of the US-led balancing coalition against China.

South Korea, however, has been lukewarm about the US efforts (Lind & Press, Citation2021, pp. 361–362). For example, while Japan has been more committed to balancing its efforts in alignment with the US, South Korea has been hedging against China (Han, Citation2008). In defiance of explicit and implicit US requests, South Korea governments have been reticent about the QUAD and have responded with ambiguity to an envisioned QUAD-Plus arrangement—an expanded format of the QUAD (Do, Citation2021). Furthermore, Seoul has been circumspect about engaging with efforts to counter China beyond the Korean Peninsula, revealing its caution about antagonizing China (Hyunh, Citation2023; Park, Citation2014, p. 110). Instead, reflecting its preoccupation with North Korea, Seoul maintains that deterring Pyongyang is the sole short-term goal of the US-ROK alliance.

Establishment of specific strategies

For two decades, the voices of South Korea and the US were divided. South Korea wanted to maintain a pre-existing forward defense strategy that involved an American forward military presence, strategically positioned along the most likely invasion routes to Seoul. South Korea believed that in the early stages of war, North Korean attacks on American troops would trigger a quick US intervention, acting as a tripwire that would ensure prompt US involvement (Roehrig, Citation2017, p. 25). Contrary to Seoul’s wishes, Washington raised the idea of realigning US Forces Korea (USFK). The gist of the relocation project was to move substantial US troops from their current positions near the DMZ to a location further south on the Korean Peninsula, specifically, south of the Han River that flows through central Seoul.

In February 2003, the George W. Bush administration’s Secretary of Defense, Donald Rumsfeld stated that ‘it is unfortunate to leave US Forces Korea in Seoul’ (Hong, Citation2004, p. 45). A month later, he again claimed that the arrangement of the USFK at the time was too inflexible: ‘We still have a lot of forces in Korea arranged very far forward where it’s intrusive in their [South Korean] lives, where they really aren’t very flexible or useable for other things’ (Associated Press, Citation2003). Tied down in the inter-Korean border to deter the North, the freedom of action of the American troops was curtailed significantly. Stressing the importance of securing the strategic flexibility of the USFK, he indicated that the USFK would increasingly assume a supportive role in the rear area of the Korean Peninsula (ibid.; Lee, Citation2005).Footnote7

Within a few hours of Rumsfeld’s statement, South Korea’s Prime Minister, Goh Kun, hurriedly met with the US Ambassador to the ROK, Thomas Hubbard. The ROK Prime Minister expressed his deep concerns about Rumsfeld’s statement, conveying three principles to the American Ambassador: ‘no lessening of the U.S. forces’ role as a deterrent against war, the USFK’s continued status as a tripwire for automatic involvement in case of North Korean aggression, and no relocation of U.S. Forces Korea until the current North Korean nuclear crisis is over’ (The Korea Herald, Citation2003). Despite the ROK’s request for a more phased approach, the US did not budge. After serious discord, South Korea accepted most of the new US position. Finally, in 2003, the two sides signed an agreement that stipulated the relocation of the USFK’s forward military bases and installations to Camp Humphreys in Pyeongtaek, 40 miles south of Seoul—which is set to be completed in the next few years.

In this regard, it is worth noting the strategic value of Camp Humphreys, which is located outside the range of most North Korean artillery range. In 2016, it was estimated that North Korea had about ‘14,000 artillery pieces and multiple rocket launchers,’ and of these ‘the only artillery system that would be able to reach Camp Humphreys was the new North Korean 300 mm multiple rocket launcher (Bennett, Citation2017).’ In addition, Camp Humphreys is located just 10 miles east of the Yellow Sea. Consequently, the location significantly enhances the strategic flexibility of the USFK. As many experts speculated, the US motivation for relocating the base was to secure rapid response capabilities against China’s territorial expansion in the broader Asia-Pacific region (Cho, Citation2018, p. 104). However, South Korea was wary of the possibility that its territory and military facilities could be exploited as an outpost to contain China and a springboard from which the USFK could be projected to neighboring flash points, including the Taiwan Strait (Nam, Citation2006). In particular, Seoul was concerned that the USFK’s further engagement in countering Beijing could lead to the weakening of the US-ROK alliance’s traditional deterrence missions against Pyongyang (Kwon, Citation2003).

In summary, for the last two decades, the distance between the US and South Korea both in terms of ‘goal setting’ and ‘the establishment of specific measures’ has been substantial. With incongruent time horizon assessments of the Chinese threat, Washington and Seoul have often experienced intra-alliance discordances and disagreements. In other words, differences in their perceptions of the urgency of the Chinese threat have prevented the two allies from forging a united and cohesive front against China.

Rebuttals to potential criticisms

In this section, I rebut potential criticisms of my argument. First, it could be argued that South Korea has recently shown a greater commitment to countering a Chinese threat, which would contradict my argument. For example, in May 2021, the South Korean government publicly expressed for the first time concern about the Taiwan issue, noting in the ‘US-ROK Leaders’ Joint Statement’ ‘the importance of preserving peace and stability in the Taiwan Strait’ (The White House, Citation2021a). Referring to the statement, the former First Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs, Choi Jong Kun, explained, ‘More than 90% of our imports and exports pass through the South China Sea and the Taiwan Strait, so stability and peace in the regions are directly related to our national interests. This is a generalized and normative statement’ (Gil, Citation2021). That is, by adding to the phrase the word ‘preserving,’ South Korea wanted to reflect its view that the current state of the Taiwan Strait is peaceful and stable (ibid.). Indeed, the mild tone of the US-ROK joint statement is subtly but distinctly different from the US-Japan joint statement, which was announced a month earlier. Referring to the Taiwan issue, the latter referred to the ‘importance of peace and stability across the Taiwan Strait and encourage[d] the peaceful resolution of cross-Strait issues’ (The White House, Citation2021b). This phrase, without the word ‘preserving,’ indicates that both the US and Japan view the current state of the Taiwan Strait as already unstable due to China’s threatening behaviors and, therefore, they believe the issue should be resolved peacefully. Moreover, the US-Japan joint statement explicitly called out ‘China’ several times, expressing ‘objections to China’s unlawful maritime claims and activities in the South China Sea,’ which are absent in the US-ROK joint statement (ibid.). In summary, the two joint statements reflect the differing threat perceptions of China held by the two Asian allies.

Another potential criticism is that South Korea’s response to a Chinese threat may vary depending on the political party in power, whether conservative or progressive. Given that the conservative Yoon administration introduced its own Indo-Pacific strategy, this critique initially seems persuasive. However, upon closer examination, the criticism’s potential explanatory power diminishes. A senior official from the Yoon administration emphasized that South Korea’s Indo-Pacific strategy does not aim to control or confront any specific state, including China. Instead, it prioritizes inclusion, distinguishing it from the US strategy (Kim, Citation2022). More importantly, when President Yoon was asked during a CNN interview about South Korea’s stance on the Taiwan issue, he responded, ‘Regarding Taiwan, China is escalating tensions—for instance, by sending aircraft above the territory of the Taiwan Strait. However, from South Korea’s perspective, the most immediate threat is North Korea’s nuclear capabilities [emphasis added].’ He stressed that deterring North Korea should remain a top priority for the US-ROK alliance, even in the event of military contingencies in the Taiwan Strait.

In the case of military conflict around Taiwan, there would be increased possibility of North Korean provocation. Therefore, in that case, the top priority for Korea and the US-Korea alliance on the Korean Peninsula would be based on a robust defense posture. We must deal with a North Korean threat first (Zakaria, Citation2022).

Similarly, during a discussion held at the Harvard Kennedy School the day after the Washington Declaration was endorsed with President Biden at their summit in Washington, President Yoon stated, ‘North Korea’s nuclear weapons are not far away but the danger is right in front of us, and in a very specific way’ (Lee, Citation2023). In summary, South Korea has consistently maintained a relaxed approach to China’s rise, which has resulted in divergent perspectives within the US-ROK alliance regarding the Chinese threat.

Conclusions

In this article, I suggest that allies’ threat-specific time horizons are a significant determinant of the degree of alliance cohesion. To demonstrate the validity of my argument I examine the empirical cases of the US-Japan and US-ROK alliances.

This article offers important implications for pundits and practitioners. First, international relations scholars who study the dynamics of threat perception have focused on material and spatial factors. For example, geographical proximity to the enemy, its military capabilities, and/or the offense-defense balance have been regarded as main elements of threat assessments (e.g. Diehl, Citation1985; Glaser & Kaufmann, Citation1998; Walt, Citation1987). However, this article suggests that states’ perception of a common threat and their resulting responses can vary according to distinct temporal characteristics associated with the threat. For example, considering only spatial and material factors, it can be said that South Korea has viewed China more seriously than has Japan because the power differential in the Sino-South Korea dyad is greater than in the Sino-Japan dyad (the material factor); moreover, Seoul is closer to Beijing than Tokyo (the spatial factor). Hence, it is to be expected that South Korea would actively cooperate with the US in countering China and align itself more fully with the ally, but this has not yet occurred. Future scholarship should examine how the temporal dimension interacts with material and spatial dimensions, and how this affects states’ actions towards threats.

This study offers several avenues for future studies. First, although this study assumes for the sake of simplicity that all congruent dyads would have the same causal impacts on alliance cohesion, nuanced differences in causal mechanisms and resulting levels of cohesion could distinguish ‘short-short’ and ‘long-long’ dyads. For example, it can be expected that allies confronting distant threats would experience greater fragmentation than those confronting imminent threats. Impending threats tend to be more visible, specific, and obvious, and thus they foster cohesion among time-pressured allies (Krebs & Rapport, Citation2012). Second, this study primarily focuses on analyzing alliance’s strategies to deter high-intensity armed attacks. However, it is important to acknowledge the growing significance within US alliances of lower-intensity threats, such as China’s gray-zone aggression and Russia’s hybrid operations (Lanoszka, Citation2016; Mazarr, Citation2015). It would be valuable to evaluate the relevance and applicability of my argument to these emerging lower-intensity threats. Third, this paper focuses on a cross-case analysis of the US-Japan and the US-ROK alliances. To supplement this study, it would be valuable to explore whether my argument can explain within-case variation in other cases (e.g. the time-variant cohesion of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)). Since Russia invaded Ukraine, NATO allies have universally perceived Russia as an immediate threat; before the invasion, they shared this perception only with some Eastern European allies (Lawless, Wilson, & Corbet, Citation2022; Reuters, Citation2015). For the first time since the end of the Cold War, the current congruent short time horizons among allies seem to have led to a very high allied consensus on goal setting and strategy establishment. NATO allies now identify deterring Russian as the alliance’s top-priority goal, and they are rapidly moving toward a forward-oriented deterrent posture by significantly bolstering deterrence forces and defense capabilities along NATO’s border with Russia (O’Donnell, Citation2022). In short, my argument seems to be highly consistent with the NATO case.

Regarding policy, as leaders of a global alliance network, US leaders should recognize that allies may endorse different time horizon assessments of particular threats. Based on that understanding, American leaders could devise a more realistic and practical rhetoric and discourse to promote a more cohesive cooperation with its allies. For example, to enhance alliance cohesion on the Chinese matter in the case of the US-ROK alliance, Washington could claim that in the event of military contingences on the Korean Peninsula, China’s aggrandizement and increasing domination of the Indo-Pacific region could limit US military maneuvers in peacetime and rapid reinforcement of the USFK. Eventually, China’s rise could weaken the credibility of US extended deterrent commitments to the South, thereby fomenting North Korean adventurism and military provocations against the South. In short, to build closer ties between Seoul and Washington, American policymakers should convince South Korea that China’s rise is a close rather than a remote threat to Seoul’s security, in part because of China’s connection to North Korea, which is Seoul’s own short-term threat. In conclusion, paying more attention to temporal dynamics will enhance both theoretically and practically understanding of alliance politics.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Iordanka Alexandrova, Joshua Byun, Noel Foster, Gorana Grgic, Edward Jenner, Dong-Hun Kim, Dong Jung Kim, Lami Kim, Tongfi Kim, Dong Sun Lee, Eunbi Lee, Manseok Lee, Shin-wha Lee, Sangsoo Lim, Neil Narang, Sunwoo Paek, Seung Joon Paik, DongJoon Park, Ellen Park, Shira Pindyck, Brian Radzinsky, the editors, and anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and constructive suggestions for this paper. The author is also grateful to seminar participants at Korea University, the University of California at San Diego, and panel participants at the annual meeting of the International Studies Association.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Do Young Lee

Do Young Lee is a Postdoctoral Fellow (Assistant Professor) in the Department of Political Science at the University of Oslo. Previously, he was a postdoctoral fellow at UC San Diego and a predoctoral fellow at the George Washington University. He holds an MA and a PhD in Political Science from the University of Chicago. His research focuses on extended deterrence, nuclear weapons, alliance politics, and the international relations of the Asia-Pacific. His article titled “Strategies of Extended Deterrence: How States Provide the Security Umbrella” was published in Security Studies (Vol. 30, No. 5). Additionally, an article titled “Upgrading the Bomb: Why and How the US Provides Advanced Nuclear Assistance to Junior Allies” was published in The Chinese Journal of International Politics (Vol. 16, No. 2), and he co-authored an article with Joshua Byun titled “The Case Against Nuclear Sharing in East Asia,” which was published in The Washington Quarterly (Vol. 44, No. 4).

Notes

1 Admittedly, deterring a common threat by pooling resources is not the sole purpose of alliance formation. States also form alliances to manage and control their alliance partners (Schroeder, Citation1976; Weitsman, Citation2004).

2 To clarify, in this paper, I focus only on peacetime alliance cohesion and not on wartime alliance cohesion.

3 In contrast to Kim’s study, which regards the attitudinal factor as the goal factor, this study posits that the behavioral factor is the goal factor. Specifically, this study examines how allies’ behaviors towards goal setting vary depending on time horizons rather than their attitudes towards it.

4 For example, see the GRAVTY variable in the ICB dataset. The dataset is available at https://sites.duke.edu/icbdata/.

5 Therefore, this article focuses on defensive alliances, excluding other alliances (e.g., offensive alliances, neutrality pacts, nonaggression pacts, and consultations). I make this choice because, among the different alliance types, ‘defensive ones have the greatest relevance for studies of deterrence,’ which are ‘the only type that commit an ally to the target’s defense’ (Clare, Citation2013, p. 547).

6 One might argue that Japan is South Korea’s informal ally or a security partner in light of trilateral US-Japan-South Korea security cooperation. Even if this perspective is adopted, it does not affect my measurement of South Korea’s time horizons—long—over a rising China, as provided below (the combined value is ‘4,’ lower than 6.).

7 Troops’ strategic flexibility refers to their capability to intervene in and respond to unexpected crises and war that occur outside the location where they are currently stationed. In the context of the Korean Peninsula, it refers to the possibility of USFK ‘being dispatched to areas outside the Korean Peninsula if necessary’ (Lee, Citation2005).

References

- Allison, G. (2018). The US is hunkering down for a new cold war with China. Financial Times, October 13.

- Associated Press. (2003). Rumsfeld wants U.S. troops in Korea moved farther from DMZ or sent home. Associated Press, March 7.

- Austin, L. J. (2021). Transcript: Secretary of defense briefs reporters on NATO defense ministerial and ongoing department of defense issues. https://www.defense.gov/Newsroom/Transcripts/Transcript/Article/2509623/secretary-of-defense-briefs-reporters-on-nato-defense-ministerial-and-ongoing-d/.

- Bandow, D. (2020). The pentagon sizes up China, sees a serious military threat. The Cato Institute, September 10. https://www.cato.org/commentary/pentagon-sizes-china-sees-serious-military-threat.

- BBC. (2014). Japan to build military site near disputed Senkaku islands. BBC, April 19.

- Bennett, B. W. (2017). Lowdown on Pyeongtaek garrison. The Korea Times, July 24.

- Cavas, C. P. (2016). Japan extends East China Sea surveillance. Defense News, March 17.

- Chanlett-Avery, E., & Rinehart, I. E. (2016). The U.S. military presence in Okinawa and the Futenma base controversy. Congressional Research Service, January 20. https://sgp.fas.org/crs/natsec/R42645.pdf.

- Cho, S. (2018). The realignment of USFK and the U.S.-ROK alliance in transition. In Kwak, T., & Joo, S. (Eds.), The United States and the Korean Peninsula in the 21st century. London. Routledge.

- Christensen, T. J. (1996). Useful adversaries: Grand strategy, domestic mobilization, and Sino-American conflict, 1947-1958. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Clare, J. (2013). The deterrent value of democratic allies. International Studies Quarterly, 57(3), 545–555. doi:10.1111/isqu.12012

- Cooper, J., & Sayers, E. (2023). Japan’s Shift to War Footing. War on the Rocks, January 12.

- Council on Foreign Relations. (2021). A conversation with foreign minister Chung eui-yong of the Republic of Korea. https://www.cfr.org/event/conversation-foreign-minister-chung-eui-yong-republic-korea.

- Dalton, T., Friedhoff, K., & Kim, L. (2022). Thinking Nuclear: South Korean Attitudes on Nuclear Weapons. The Chicago Council on Global Affairs. https://globalaffairs.org/sites/default/files/2022-02/Korea%20Nuclear%20Report%20PDF.pdf

- Denyer, S. (2019). Japan builds an island ‘wall’ to counter China’s intensifying military, territorial incursions. The Washington Post, August 21.

- Dian, M. (2014). The evolution of the U.S.-Japan alliance: The eagle and the chrysanthemum. Oxford: Chandos Publishing.

- Diehl, P. F. (1985). Contiguity and military escalation in major power rivalries, 1816–1980. The Journal of Politics, 47(4), 1203–1211. doi:10.2307/2130814

- Do, J. (2021). Korea faces growing calls to join Quad plus. Korea Times, February 7.

- Edelstein, D. M. (2017). Over the horizon: Time, uncertainty, and the rise of great powers. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Edelstein, D. M. (2020). Time and the rise of China. The Chinese Journal of International Politics, 13(3), 387–417. doi:10.1093/cjip/poaa010

- Faiola, A. (2005). Japan to join U.S. policy on Taiwan. The Washington Post, February 18.

- Fearon, J. D. (1997). Signaling foreign policy interests: Tying hands versus sinking costs. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 41(1), 68–90. doi:10.1177/0022002797041001004

- Fouse, D. (2011). Japan’s 2010 national defense program guidelines: Coping with the ‘grey zones.’ Honolulu: Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies.

- Gallo, W. (2021). US rules out redeploying tactical nukes to South Korea. VOA News, September 24.

- Gibbs, S. (2014). China rising: Xiaomi becomes world’s third biggest smartphone manufacturer. The Guardian, October 30.

- Gil, Y. (2021). 정부, 한-미정상성명 ‘대만언급’ 논란 조기차단 나서 [Government tries to cut off controversy over ‘Taiwan reference’ in Korea-US summit statement]. 한겨레 [The Hankyoreh], May 24.

- Glaser, C. L., & Kaufmann, C. (1998). What is the offense-defense balance and can we measure it? International Security, 22(4), 44–82. doi:10.2307/2539240

- GlobalSecurity.org. (n.d.). China’s defense budget. https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/china/budget.htm?utm_content=cmp-true

- Gould, J. (2023). Japan to OK new US Marine littoral regiment on Okinawa. Defense News, January 11.

- Han, S. (2008). From engagement to hedging: South Korea’s new China policy. Korean Journal of Defense Analysis, 20(4), 335–351. doi:10.1080/10163270802507328

- Harris, B. (2018). South Korea: The fear of China’s shadow. Financial Times, August 19.

- Heydarian, R. J. (2011). The fading U.S.-Pakistan alliance. Foreign Policy in Focus, December 23.

- Holsti, O. R., Hopmann, P. T., & Sullivan, J. D. (1973). Unity and disintegration in international alliances: Comparative studies. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Hong, G. H. (2004). The drawdown and realignment of USFK and South Korea’s security. Seoul: Korea Institute for National Unification.

- Horowitz, M., McDermott, R., & Stam, A. C. (2005). Leader age, regime type, and violent international relations. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 49(5), 661–685. doi:10.1177/0022002705279469

- Hughes, C. W. (2009). Japan’s response to China’s rise: Regional engagement, global containment, dangers of collision. International Affairs, 85(4), 837–856. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2346.2009.00830.x

- Hughes, C. (2011). Reclassifying Chinese nationalism: The geopolitik turn. Journal of Contemporary China, 20(71), 601–620. doi:10.1080/10670564.2011.587161

- Hyunh, T. (2023). Bolstering middle power standing: South Korea’s response to U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy from Trump to Biden. The Pacific Review, 36(1), 32–60.

- Inhofe, J., & Reed, J. (2020). The pacific deterrence initiative: Peace through strength in the Indo-Pacific. War on the Rocks, May 28.

- Japan MOD. (2012). Defense of Japan 2012. Tokyo: Japan MOD.

- Japan MOD. (2019). Defense of Japan 2019. Tokyo: Japan MOD.

- Japan MOD. (2016). Defense programs and budget of Japan: Overview of fy2016 budget. Tokyo: Japan MOD.

- Japan MOFA. (2021). The Senkaku Islands. Tokyo: Japan MOFA.

- Kih, J. (2020). Capability building and alliance cohesion: Comparing the US-Japan and US-Philippines alliances. Australian Journal of International Affairs, 74(4), 355–376. doi:10.1080/10357718.2019.1685935

- Kim, D. (2022). Office of the President ‘Indo-Pacific Strategy Includes China as a Partner [대통령실 ‘인도태평양 전략, 중국도 협력 대상에 포함’]. Chosun Ilbo, December 28.

- Kim, H. (2011). Substantiating the cohesion of the post-cold war US–Japan alliance. Australian Journal of International Affairs, 65(3), 340–359. doi:10.1080/10357718.2011.567442