Abstract

Refugee students may come to schools with fragmented educational histories and other exile-related stressors, but many also settle fast, enjoy school and live rather ordinary childhoods. These more positive stories are not told because they get overridden by well-meaning but counterproductive stories of victimhood. This article presents a storycrafting project with 13 primary school aged refugee children in Australia, with an aim to problematise this deficit-discourse. The outcome was the group’s “preferred narrative”, that is, a story combining fact and fiction within the dialogical process between the teller and the audiences. The story was published as a fictional book and an animated film entitled Ali and the Long Journey Australia. This article discusses this process and its outcome; how a child-led project combining fact and fiction can inform qualitative research, and how stories are welcomed by audiences which are out of reach by regular research outputs.

Introduction

In my qualitative, Finnish-Australian research What enables refugee background students’ educational success, I asked children from a range of refugee-like backgroundsFootnote1 to talk about and draw their positive school experiences. The participating children drew their educational journeys from the time they started school in their countries of origin, or countries of transit, to the present day, and marked all key moments in which they had felt successful or happy at school (see Kaukko & Wilkinson, Citation2020).

One of the girls—I will call her LinaFootnote2—loved this activity. Her drawing started to look more like a piece of art than research data, and my interview with her lasted much longer than anticipated. The story she told was filled with detailed accounts of events she wanted to share and key people she was happy to recall.

“Who’s going to hear these stories?” she asked at the end of the long interview. I replied that only I would hear the story as she told it and that I would later publish some parts of the story for other researchers to read. I also assured her that the readers would not know who told the story because her name would not be published.

Lina was not satisfied with this answer. On the contrary, she was horrified to hear that her story would be published in parts and without her name and that the audience would be limited to researchers. “Wouldn’t it be nice if other children could hear these stories too?” she asked. She then explained her reasoning, saying that more people, especially other children, should understand that refugee children, such as herself and her friends, do normal things and live normal lives. I agreed, unwilling to tell her that the tradition of academic publishing compels me to turn her story into a more or less detached, dehumanised account for perusal by a handful of other academics. Furthermore, I did not mention that the institutional structures of universities tend to discourage the public outreach of academics even in fields as inherently public as education, despite their bold, opposite claims (Spyrou, Citation2021). Lina had a vested interest in my research; she wanted other children to understand more about the lives of refugees. I also wanted this, and as a researcher with background in primary school teaching and a strong interest in children’s rights and participation (Kaukko, Citation2017), I considered it my responsibility to support Lina’s wish. However, I acknowledged the ethical and practical challenges of sharing her story as it was told.

Lina’s comments were the starting point for a group-storycrafting (Karlsson et al., Citation2019) project, which aimed to hear, document, and present the stories of refugee children as they wanted them to be heard. The project evolved into a co-produced “preferred narrative” (Lenette, Citation2019, p. 118), that is, a story that takes shape within the dialogical process between the teller and the audience and in which the protagonist(s) decide(s) what to include and exclude, what is important to them, and how the story should be framed for their own or public viewing. The outcome was published in the form of a fictional book and a short, animated film entitled Ali and the Long Journey to Australia (henceforth Ali). Although writing Ali was an unplanned sideline of my original research, it became a powerful counter-narrative problematising some of the taken-for-granted assumptions about refugee children’s lives.

Like all representations of refugees, the story of Ali has its limitations. It may be argued to fit too well within the familiar and established humanitarian frames of the refugee narrative (Malkki, Citation1996; Rajaram, Citation2002), thus strengthening the stereotypes it seeks to problematise. It may also be criticised for separating refugee experiences from their historical and political roots by not providing enough context. However, Ali is the children’s story, told as they want it to be heard. Furthermore, as I show later in this paper, its reach turned out to be much broader and more powerful than that of any of my other research outputs.

In this article, I discuss the Ali project both in terms of its product and processes. The product relates to Ali’s contribution to knowledge, in other words, how fictional stories can add to our knowledge in educational research by illuminating children’s realities. My attempt here is not to justify the project in terms of scientific rigor, reliability, or validity, or to ask whether the story is true. My aim, rather, is to read the preferred story of Ali and ask, like Bochner (Citation2018), “What if this were true? What then?” This calls attention to which stories are told, how they are told, and what knowledge these stories produce or hide. Secondly, I discuss the process of crafting and disseminating the story and how it managed to honour the wishes of the participants and how I, a female researcher without a refugee background, received the story. Finally, I consider how the story reached the audiences the authors wished to engage with—in this case other children and those who work with children—and its potential in changing their hearts and minds.

Refugee children as victims/heroes/topics of stories

The question of how stories are told is particularly important when working with marginalised populations, such as refugee children. I am by no means the first to argue that even the term “refugee” has negative connotations, and it is not surprising that Lina wanted to challenge that discourse. Framing refugee narratives is always a complex process of selection. Simplifying refugee stories to be suitable for children may miss the multi-layered nature of human experience and essentialise refugees into a faceless mass (Rajaram, Citation2002) and reinforce colour-blind narratives about a universal “refugee identity” and a universal refugee journey (Strekalova‐Hughes & Peterman, 2020). Simplified accounts might also underestimate children as readers and thinkers. On the other hand, writing about refugees, without mentioning their background may also be risky. It can erase their presence from stories, another issue that Lina identified clearly, or what’s worse, imply that their experiences are something be ashamed of or that their existence is of no relevance to their peers. Likewise, enough socio-political contexts of displacement should be provided to connect the experiences to their historical roots (Strekalova-Hughes, Citation2019) while at the same time keeping the stories short and their audience, in this case children, in mind.

Some of the same risks apply in how research on refugee-related topics is communicated. The vast majority of research on refugee education shows how pre- and post-displacement risks and barriers negatively impact on the lives and learning of refugees long after their settlement (Graham et al., Citation2016; Montgomery, Citation2011), schools in host countries fail to recognise the skills and knowledge which refugee students bring to formal learning (Wilkinson et al., Citation2017; Yosso, Citation2005) and that teachers feel unequipped and untrained to respond to the academic and social needs of refugee students (Roy & Roxas, Citation2011). I do not wish to undermine this important scholarship or the very real challenges many refugee children face. Yet much of this research, covertly or overtly, portrait refugee children and youth as solely needy or greedy and their new schools as remedial places. Interspersed with such negative images, there are also narratives that celebrate the achievements of refugees who are considered successful in their new societies. These are the lucky few who tend to be portrayed as “miraculous exceptions” (Bourdieu, Citation1979), thriving against all odds. As Adichie (Citation2009) states, the problem with stories of exceptionality is not that they are untrue; the problem is that they can become a single story. Whatever their source, single stories of exceptionality exclude the ordinary life, far from the dramas of individual exceptions (see also Wang et al., Citation2019).

A final issue worth mentioning here is that children, across the board, are more often the topics of stories than the narrators of the stories. When children’s stories are written, they are almost always authored by adults. This is true for both academic and non-academic texts, and it is not always a bad thing; many adults make efforts to preserve the child’s unique, unadulterated voice as much as possible. There have been various attempts to observe, elicit, or dialogue with the voice of a child (Jackson, Citation2003; Mayes, Citation2019). At the same time, many authors are conscious that a “voice” cannot be commodified or reproduced in its authentic form, no matter how genuine our attempts as researchers or authors are. All people, regardless of status, already have a voice but if care is not taken, voice can be misinterpreted, or even misused (James, Citation2007; Mayes, Citation2019; Spyrou et al., Citation2019). However, the unavoidable fact is that texts about children, written or published by adults, often comprise the “child’s voice” that wider audiences hear. The risk cannot be fully avoided but it can be mitigated by the adults’ reflexive and transparent accounts of their own roles in the process.

So, while most of the literature within and beyond educational research highlights the exceptional (mostly negative) aspects of refugee children’s lives, a small but growing body of research has started to challenge these unhelpful polarisations (e.g. Crawley & Skleparis, Citation2018; McIntyre & Abrams, Citation2020; McIntyre et al., Citation2020; Wang et al., Citation2019; Wernesjö, Citation2012). These studies often implement critical, participatory, and arts-based methods (Lenette & Cleland, Citation2016; Nunn, Citation2010; Winskell & Enger, Citation2014) to experiment with ways to challenge the taken-for-granted assumptions regarding refugees and other marginalised groups and be more sensitive to the complexity of their experiences. Another emergent body of research which is relevant to this article is that of critical public childhood research (Spyrou, Citation2021). It aims to take research with children closer to its diverse public audiences and engage with them in ways that are meaningful. Its criticality lies in the fact that it aims to retain scientific rigor and critical capacities by engaging in social critique and social justice debates and by being robust and reflexive as a result of being public (Burawoy, Citation2005; Spyrou, Citation2021).

Some educational research with children, as well as in rare cases with adults, uses fiction as a tool to generate data or communicate findings (Clough, Citation2002). Some may do it because, unlike simple facts, stories with fictional characters have the power to evoke feelings. Others may turn to fiction to present claims to evidence in accessible, ethical, and emotionally engaging ways without claiming that those facts per se would be true. Like Bradshaw (Citation2007) puts it,

[Stories] speak a truth unlike any other, because they are irremediably tied to the world, and aim at trying to fit us in a coherent way into a world and a history that otherwise appear contingent, capricious, and wayward. They aim at reconciling us to reality, and at helping us to cope with sorrows. In accomplishing this end, stories often lie about facts in order to get to a truth beyond facts, but even while doing so, there are limits to the extent of the forgery. The world calls us back and is still the reference point for the truth content of stories. Stories differ from the truths of fact-finding and philosophical reflection, because they are sort of in between the two. Like the fact-finder, the storyteller turns to the world for her material, but not completely. (Bradshaw, Citation2007, p. 16)

Stories can also be used to generate research data in non-traditional ways or foster dialogue with research participants prior to the actual research. Stories give us the power to imagine what our futures could look like or what to make out of our pasts (MacIntyre, Citation2013). Through stories we can come to know the world and ourselves, make discoveries, find things that have been hidden in the shadows, and find ways to speak of what has been unspoken (Farrant, Citation2014). Artistic, fictionised research forms have the potential to engage with non-academic audiences, problematise stereotypes, and influence policy and public attitudes unlike many other research approaches. Their rigor exists in relation to the imagination, aesthetics, and creativity that make the project good (Bochner, Citation2018; Leavy, Citation2016) or in the reflexivity the researcher shows throughout the process (Spyrou, Citation2021). Importantly for our purposes in Ali, fiction may sometimes be the only way to get to a truth beyond facts if the actual, identifiable facts are too sensitive or impossible to share due to ethics guidelines. So, Ali cannot be read as a true story of those who wrote it, but it can be read as a truthful story. Before sharing the story, I describe the process of its creation.

Storycrafting as a method to convey a preferred story

The children who participated in my research had experiences that could add to our understanding of refugee childhood and disrupt the single story told of it. My dilemma was that anonymous research publications did not seem to be the most powerful way to share this knowledge. Few people would read it, and the readers would not include the audiences Lina wanted to address. The anonymity would hide the origin of the stories and remove the authorship from its creators. This is why I turned to storycrafting (Karlsson et al., Citation2019; Riihelä, Citation2001), a dialogic research method of sharing experiences by telling and listening. It originates from the field of child psychology in Finland, first as a therapeutic tool and later, in the 1990s, as a part of arts-based research methodological genre responding to the marginal, invisible, and inaudible position of children in societies (James & Prout, Citation1990). Storycrafting is situated within the nexus of narrative and participatory research approaches (Karlsson, Citation2013), and its aims are similar to many other public-oriented and artistic approaches (Leavy, Citation2015): to help the storycrafters be heard; to help the listeners to listen; and to maximise the reach of the produced stories. Like in any qualitative research, its quality criteria must be tied to study-specific theories, paradigms, and to the communities the study aims to serve (Tracy, Citation2010). In this project, theories of childhood and research about refugee children (Kohli, Citation2006; Spyrou et al., Citation2019) helped me interpret the stories as part of their contexts.

Storycrafting has mostly been used in research with (young) children in schools, but also with other groups such as the elderly and asylum-seeking children (Lähteenmäki, Citation2012; Silvennoinen, Citation2011). The steps of the method are simple:

The listener (usually an adult) asks the narrator/narrators (usually a child or children) to tell a story as the child wants it to be heard.

The adult writes it down, word by word.

The adult reads the story back to the child or children so that they can be sure that they are understood correctly,

The adult asks the child or children if there is something they want to change and edits as long as is necessary for the story to become ready.

When I proposed a storycrafting project to Lina’s school, they were keen to participate. A new ethical review was conducted,Footnote3 an open invitation was sent to all the children who had participated in another research I conducted at the school in collaboation with Jane Wilkinson. 13 children (9–12 years of age), Lina being one of these, agreed to take part. After discussing with them how this project differed from their participation in research, especially in relation to publicity and privacy, the group created the story in 12 2-h sessions. The children and their school wanted their own names to appear in the output and accompanying media material to ensure that they kept ownership of the outcome (for more about the process, see Monash Lens, Citation2018).

Most storycrafting projects start without a particular subject or specific questions. The child is encouraged to tell any kind of a story, be it true, fictional, or a mix of both, and keep full ownership of it. There should be little guidance and, importantly, no value judgements from the listener. In the storycrafting project leading to Ali, the starting point, that is, the children’s shared migration experiences, was pre-determined, as it brought us together and justified the project. Crucially, the children were not prescribed a particular storyline to follow, but rather the process was non-sequential (Johnson & Kendrick, Citation2017).

The story was told by the children and edited in its final written form by me. The process began with one student narrating, continuing as long as he or she wanted. Other students then followed, one at a time, adding their own ideas to the common story. The transcribed storycrafting narrations included false starts, repetition, parts that were told but immediately changed, and even listeners disagreeing with what was being told. In the instances of disagreement, I as the facilitator encouraged the narrator to keep telling as long as she or he would be satisfied with the part, while reminding the listeners to respect the narrator. Such interventions compromised my neutrality in the process, but they were needed to keep the atmosphere safe and respectful. Due to my background in primary school teaching, they also came rather naturally.

At the beginning of each meeting, I read the story in its current form for the children inviting them to comment, criticise and question it. When there was a need to decide matters such as the family composition, the authors paused and negotiated between themselves. When there was something to be checked, such as whether it was even possible to travel by boat from Somalia to Australia, the authors investigated the issue. In these instances, the group spread out across different working spaces in the workshop area. Flexible groups and room to move around fostered richer dialogue and jointly produced, rather than pre-planned, conversation. All of the important negotiations and investigations were initiated by the authors to keep the project as child-led as possible and to ensure that everyone’s chosen moments were added to the story. It also ensured that the outcome became sufficiently credible and true to the combination of the authors’ experiences. This process of telling, listening, and reading continued until the story was ready to the group’s satisfaction. I, as the adult listener, avoided correcting, questioning, or overly editing the story. Also, although the feminist in me struggled to keep quiet, I did not to problematise the group’s unanimous decision to have a male protagonist in the story. When the children asked me how to rephrase something, I offered advice but did not push the story in any direction. By giving this kind of help when it was asked for, I was honouring the children’s wish to produce a story that would be as high quality as possible.

When the children were happy with some sections of the story, I wrote them onto an interactive Padlet-platform. Children could enter the Padlet to read, comment, and suggest different ways to continue using their own devices. Padlet was also used to store images and additional resources, some of which ended up in the final story. At the end, the story was stitched together as a cohesive plot.

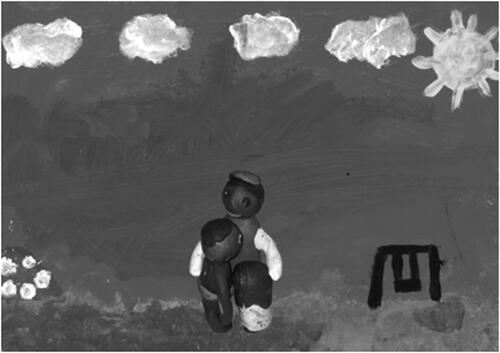

The story was finished when the whole group was happy with it, that is, when nobody wanted to change or add anything. This instance, occurring after eight joint workshops, was when we arrived at one version from many. This is when I considered that Ali had become the group’s preferred story. Next, the story was illustrated by the authors. We discussed how it would be laid out in printed book form, how each part of the story would be illustrated and by whom. The authors painted the backgrounds and made Plasticine figures for the characters. The final illustrations were photos of the Plasticine figures arranged in front of the painted backgrounds (see ). The book was printed in full colour and distributed to libraries, schools, and NGOs through our networks. The media teamFootnote4 from my then-employer, Monash University, saw the book and came up with the idea of making Ali come alive in a stop motion animation, using the original, child-made Plasticine figures and the paintings. It was to be a collaborative effort involving the children, myself, the media team, the participating school, and various animation artists. One of the authors narrated the story as the fictional Ali-character. Since the authors were keen to share their story as widely as possible, we distributed the subtitled animation in Finland.

Overall, the process of storycrafting went well; the children were keen to participate, the sessions were pleasant, and the outcome was satisfactory. We prioritised usefulness and workability over following the storycrafting steps precisely, ensuring the practical value of the process. We used multiple textual, visual, and verbal methods of communicating rather than simply relying on language and text. This was done to make the process easier for the children who created it in their second or third language (Vecchio et al., Citation2017). It also added to the project’s creative and aesthetic value. Illustrations, carefully created, brought the story to life, calling “the nonlinguistic –- into the service of the linguistic as supplementary resources”, as Johnson and Kendrick (Citation2017, p. 668) put it. The practical choices were designed to give the children freedom to think out loud and be creative about what they wanted to share with others based on their thoughts, feelings, memories, and experiences (Lenette et al., Citation2019), without worrying about the technicalities of composing a coherent and a credible final story. The ethics of the process meant that rather than being overly worried about the risk of compromising the children’s anonymity, I considered my relational obligation to the children and their story and my opportunity to disseminate the story as the authors wanted it to be heard. They decided what to include or omit with their imagined audiences, most importantly, other children, in mind, and they together co-constructed it into their preferred story. As Lenette et al. (Citation2019, p. 83) argue, enabling these preferred stories is important because, in contrast to the more common presentation of “trauma stories”, they can illuminate some of the unique ways in which refugees make sense of their at times disrupted lives, using their own voice and own frames of reference.

Ali and its truths

The plot of the story can be summarised as follows: 10-year-old Ali and 7-year-old Fatima play hide and seek in their home country, Somalia, when their home is bombed and burned. Ali and Fatima’s parents, simply named Mother and Father in the story, come and find the children; they must flee. The family seeks shelter in their relatives’ home. After some time, a military group comes to the house, asking for Ali to join the army. Father does not allow Ali to go, so he needs to go in Ali’s place. Mother flees with the two children. With the help of smugglers, they board a little boat, uncertain of the destination. The boat sinks, and the passengers, including the family, are rescued in a helicopter. The family is taken to Australia, where they seek asylum and move to a tall apartment building in the city. The kids start school, and life starts to return to normal. One dramatic day, Ali and Fatima come home to find Mother crying. They are afraid of what might have happened, but the news is happy: Father was found in another country, and he would soon be on his way to Australia. The closing scene shows a united, happy family, ready for their new life in Australia.Footnote5

In all its innocence and naivety, the story of Ali is true. Its truth lies in the collective experiences of the authors and their agreement on how parts from their experiences could form a preferred story. All of the major events are based on real life, although the sequence of events was invented and parts were combined from different stories. So, while Somali asylum seekers do not really travel to Australia by boat, and asylum seekers arriving by boat are generally not accepted to settle in mainland Australia, the experiences behind these parts of the plot were true. Some of the authors had left Somalia, others had arrived by boat via offshore detention centres, and with a child’s imagination and a quick look at the map, those experiences can be combined. It was not my place, as the adult facilitator, to judge or check facts. Rather, the question for me was: what can be understood from the process and the outcome, and what if the story was true? The validity of a fictional story, in Leavy’s (Citation2016) view, means that the story could have happened. All the parts in Ali had happened or could have happened, at least in the minds of children whose experiences are close to those of the fictional character of Ali.

Without over-interpreting what is, overall, a fictional product, it is worth considering what the story illuminates about refugee children’s lives. For example, what is highlighted from Ali’s pre-migration life is normality. It takes the form of a soccer ball and a bedroom, both signifying ordinariness in Ali’s life. It can be read as a counter-narrative to the dominant, reductive, or stereotypical narratives that would present Ali and Fatima as being solely or primarily refugees fleeing extraordinary lives. They lived rather normal lives, but it was lost because of war. In turn, the school with its chickens, as well as the new apartment building in Australia, communicated ordinariness that was regained. The choices to include these details in the story were not made deliberately or to respond to Lina’s comment. Yet from the abundance of events and items mentioned in the strorycrafting sessions, the children decided to choose events of normality. This may be their way of conceiving their experiences as part of a rather ordinary childhood story, but also connecting the story to themes that other children could relate to.

Secondly, the story illuminates hope throughout its rather dramatic text. In the process of storycrafting, the group decided that Ali and Fatima would lose their father. Losing somebody from the family is common among refugee families; some of the authors had experienced it themselves. Yet losing a father permanently felt too dramatic for them so, in the final story, the family is reunited. Talking to the authors about this afterwards, it became clear that the decision was to include hope in the story. Those who had lost their loved ones were generally optimistic that they would see their families again, however unlikely it seemed. So, the authors chose to tell a story without downplaying trouble and while highlighting hope. A more pragmatic and mundane reason for this twist, as the authors told me, is that children’s books must have a happy ending (see ).

There is a third, methodological layer to the narratives presented here which needs acknowledgement; how some experiences are easier to communicate with silence and not voice (see Kohli, Citation2006). One author wanted to include a shipwreck, but rather than portraying it in words, this child contributed by painting the stormy sea (see ). When the animation was designed, the child explained what kind of backing soundtrack the scene should have. In this way, the child’s emotion, significance, and meaning were produced in the sounds and not just the words themselves (Lenette, Citation2019). Another child’s contribution was a carefully crafted Plasticine boat that Ali’s family used to flee from their country. The boat, as the author told the group, was as accurate as the child could remember. Neither wanted to narrate these experiences in words; other authors filled the silent gaps for the story. Without over-interpreting these silences, they could serve the purpose of saying: “I have experiences I don’t want to talk about, but they should be part of the story”. This silence should be honoured and different methods of communication promoted. Probing for more information or details would put the narrators at unease or cause worry about how they can be shared and with whom, and whether their stories would sound credible (Kohli, Citation2006). This highlights the importance of treating storycrafting as a relational narrative method rather than a mere data generation tool.

Claiming that Ali is true would hardly fill any conventionally accepted criteria of rigor, validity, or reliability. Knowledge from stories cannot be validated with these criteria for the simple reason that fiction is inevitably at odds with traditional logic-rationalistic forms of knowledge. Therefore, I argue that Ali can only serve partial truths; they are true as evidence of the authors’ personal meaning, but not of the factual occurrence of the events reported (Karlsson et al., Citation2019; Polkinghorne, Citation2007). Another group would craft a different story; another researcher would come to different conclusions from it. My positionality as a teacher and a non-refugee immigrant woman with children of similar ages as the authors shaped my interaction with the group. It also influenced my interpretation of the story. The best I can do is to argue that I attempted to retain a critical and reflexive stance towards the knowledge practices and engagements relevant to Ali (see Spyrou et al., Citation2019), and make my partisan position transparent. The authors wanted to keep the final story short and optimistic. It may lack cultural depth and accuracy—I already mentioned the boat trip from Somalia—and fall short on the complexity and nuance of refugee children’s lives, but it is a counter-narrative which the authors, not me as the facilitator or researcher, wanted to tell.

So, by asking what if the story was true, I was encouraged to consider what the authors want us to know about refugee children’s lives, how they want this story to be told, and if it truly is the united wish of the whole group. It is impossible to say how well I succeeded in this, but my interpretation is that the stories the group wanted to tell were those of normality and hope, as they were true and present in their lives (see also, Kaukko et al., Citation2021). The authors wanted to problematise the dominant stories of refugee children’s suffering, which they knew their peers in school often heard.

The reach of the story

Lina’s aim was to “go public” with the research she was part of and which produced findings she wanted to share. The other authors shared this aim, as did I. The aim to widen the public reach of research is not a novel idea. In order to transform society, provoke empathy, change minds or hearts, or do research that is in some other way socially relevant, findings need to be accessible to wide audiences (Burawoy, Citation2005; Flick, Citation2020; Vannini, Citation2019). Ali’s reach, based on views and engagement online, is one way to estimate this.

Ali broke audience records for my then employer, Monash University. It’s combined reach across the social media accounts of the university and my faculty included 600,000 viewings and more than 30,000 engagements (shares, likes, clicks). These engagements included 1,600 comments, compared to an average of approximately 87 reactions on standard Monash University posts. The majority of comments congratulated the students on their story and thanked them for telling it. Well-known Australian children’s authors such as Andy Griffiths and Eddie Woo sent their regards to the children; Mem Fox sent a box of her books entitled I am Australian too, with hand-written notes for the authors. Teachers in Australia, the UK, and Finland have used the film as a resource in their classroom. To date, the film has been seen by hundreds of thousands of people on different platforms, including a video embedded in the Guardian Newspaper. The film was also featured on ABC Me, a news program produced by the Australian national broadcaster for children and premiered at Federation Square as part of Australian Refugee Week. The highlights of all this were when the animation received an award at the Sydney International Film Festival in the Films by child-adult collaboration category and at the Melbourne Human Rights Art and Film Festival in the Human rights resources for children category.

This attention highlights Ali’s impact in terms of its resonance (Leavy, Citation2015; Satchwell et al., Citation2020). The feedback showed that Ali resonated with its audiences and the authors resonated with the audiences, in other words, children succeeded in addressing the audiences they had in mind. “I thought no-one would really notice it, but I was wrong”, one of the authors noted in a feedback session at their school. “It means the world to me, because everyone can understand how I feel”, added another. We managed to reach children by using formats that children enjoy and find unintimidating (Vannini, Citation2019), which the story’s authors accounted for in their planning. This included, for example, the decision that a story must be short and have a happy ending. We reached adults who worked with children (teachers) and adults who had the power to speak to still more children (authors, researchers, media people). None of this would have happened without a good plan, the school’s support, a team invested in the project, an effective communication strategy, and most importantly, a moving story to tell.

Most of the factors that helped to boost Ali’s reach, such as the above-mentioned planning, teamwork, and communication, can be considered when planning future storycrafting projects with children. The final, unpredictable factor that boosted Ali’s reach was that the timing and the social-political climate of Australia were perfect. Our story came out at a time when refugee issues were prominent in the media, especially due to the horrific situation of detained children at Nauru and other offshore detention centres of Australia. The public audiences in Australia were keen to welcome more ordinary stories of refugee children and, in particular, by refugee children, so Ali offered a counter-narrative to the media stories illustrated with images of children behind bars. Ali did not downplay the suffering of some other refugee children at that time, but it may have managed to highlight the humanness in refugee stories. Another supportive element were the critical voices in education, questioning the increasingly strong emphasis on test driven accountability in Australia. The Australian school system places a lot of weight on standardised tests such as NAPLAN (The National Assessment Program—Literacy and Numeracy), but critics argue that such tests are hardly equipped to identify and acknowledge the diverse literacy skills of students from minority backgrounds. Ali can be seen as evidence of the creativity and resourcefulness of such a group of students if they are given the chance to show their skills.

Ali was written to serve the purposes of children and not research, so we can only guess its actual transformative power, that is, how many viewers were moved, impacted, or changed, and whether the impact was limited to the people who were already empathetic to the cause. Measuring intangibles such as emotions is always challenging and impossible in retrospect, but the pride the authors and their school showed in this work shows that at least 13 children and their school community were impacted by Ali. The engagement of other children online shows that the story reached the targeted audiences, that is, other children with and without refugee backgrounds. A future storycrafting project could go a step further by planning and incorporating a measurement tool to be used after an audience views or hears a story. This could show what many of us already know: by evoking new ways of knowing and understanding, stories have power to change hearts and minds.

Discussion

My aim in this article has been to describe and discuss the storycrafting process leading to Ali in a robust and reflexive manner so that the reader can better understand the outcome that is already public. I have invited the reader to consider Ali in particular in terms of its truths, methods, and reach.

The truths of Ali were that refugee children’s lives within and beyond schools are not full of trauma and trouble, as many of them live a rather ordinary life. This is what the authors of Ali wanted to communicate. Ali “lied” (Bradshaw, Citation2007, p. 16) about single facts as needed to go beyond them, while still being evidence of true, personal experiences of a group of children who are brought together by forced migration. The story was chosen to be told in an optimistic manner, using a variety of communication styles that suited the authors as well as those they wanted to address. The creation was a dialogical process between the authors, me as the facilitator, and the imagined audiences. As a teacher and a mother, I did not hesitate to intervene at times of conflict. This helped the more silent voices to be included and kept the process safe and democratic. The final product includes the elements that the authors chose, in ways they wanted them to be communicated. This is how the story of a fictional child named Ali became the group’s preferred story. As Lina argued, sharing this story matters because it can make the lives of children like Ali feel less foreign and less extraordinary to other children. It can problematise the narrow-gazed, problem-focused narrative around refugee children and, perhaps, change some people’s thinking.

Ali invites us to expand the quality criteria of research towards fictional elements and to be more creative in our search for methods that could amplify the less-often heard voices in research. Not all knowledge can be shared in words, which is why we need to tune our senses to be more receptive. The main desire of the authors of Ali was to talk to other children, with or without refugee experience, and children’s engagement in social and other media shows that the authors were successful in doing that. My aim with this article was not to ensure that the text is scientific, detached, and valid, but to do the opposite and make it reflect some of the creativity, urgency, and believability the authors wanted to communicate in Ali.

The reach and success of Ali was not a coincidence, and it was not my achievement. The moving story, the efforts of the school and the marketing team, the right timing, and the resulting warm welcome were key factors in Ali’s success. The story, with its nuances and detailed illustrations, would not have been possible to create from imagination alone. It would have been impossible to share, ethically, purely from research data. Combining fact with fiction was the only way this story could be told. I hope you enjoyed it.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful for Noble Park Primary School, Melbourne, particularly Principal David Rothstadt, for their continuous support throughout this process. I also wish to acknowledge Jane Wilkinson (Monash University) who has been my co-researcher in the study, Tomi Kiilakoski (Youth Research Society, Finland) who suggested storycrafting as a method, Lara McKinley (Monash University), Rodney Dekker and Clem Stamation who produced the film with us, and Kaneli Kaukko who created Finnish subtitles for the animation. Most importantly, my warmest thanks for all the children contributed to Ali.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mervi Kaukko

Mervi Kaukko works as Associate Professor (Multicultural Education) in Tampere University, Finland, and she is an adjunct research fellow (Education) at Monash University, Melbourne, Australia. Most of Mervi’s research has been conducted with refugee- or asylum-seeking children and youth. At the moment, Mervi’s projects investigate refugee students’ day-to-day educational practices and their experiences of success; young refugees’ relational wellbeing; and asylum-seeking students’ experiences in higher education in Australia.

Notes

1 Refugee-like background is a term used in policy and research to refer to both refugees and asylum seekers, but also to other individuals and groups who have left “areas of concern” (UNHCR, Citation2019). The term departs from governmentally designated and often politized categories of those deemed worthy of aid and acknowledges that the line between voluntary and forced migration is often blurry. In this paper, I use the term to refer to children who have arrived in Australia from areas of conflict (UNHCR, Citation2019) without seeking sensitive information about their visa status.

2 Pseudonym approved by the participant.

3 Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee Approval 13105

4 Content producer Lara McKinley led the project which involved video production, media outreach and social media planning. Rodney Dekker was contracted to co-produce the video component and Clem Stamation did the stop-motion animation.

5 See the whole story here: https://issuu.com/trustproject/docs/ali_and_the_long_journey_to_austral

References

- Adichie, C. N. (2009). Ted talk: The danger of a single story. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D9Ihs241zeg

- Bochner, A. P. (2018). Unfurling rigor: On continuity and change in qualitative inquiry. Qualitative Inquiry, 24(6), 359–368. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800417727766

- Bourdieu, P. (1979). The inheritors: French students and their relation to culture. University of Chicago Press.

- Bradshaw, L. (2007). Narrative in dark times. In F. Fagundes & M. Blayer (Eds.), Oral and written narratives and cultural identity (pp. 9–23). Peter Lang.

- Burawoy, M. (2005). For public sociology. American Sociological Review, 70(1), 4–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240507000102

- Clough, P. (2002). Understanding stories. Narratives and fictions in educational research. Open University Press.

- Crawley, H., & Skleparis, D. (2018). Refugees, migrants, neither, both: Categorical fetishism and the politics of bounding in Europe’s 'migration crisis. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 44(1), 48–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1348224

- Farrant, F. (2014). Unconcealment: What happens when we tell stories. Qualitative Inquiry, 20(4), 461–470. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800413516271

- Flick, U. (2020). Hearing and being heard, seeing and being seen: Qualitative inquiry in the public sphere—Introduction to the special issue. Qualitative Inquiry, 26(2), 135–141. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800419857766

- Graham, H., Minhas, R., & Paxton, G. (2016). Learning problems in children of refugee background: A systematic review. PEDIATRICS, 137(6), e20153994–e20153994. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-3994

- Jackson, A. Y. (2003). Rhizovocality. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 16(5), 693–710. https://doi.org/10.1080/0951839032000142968

- James, A. (2007). Giving voice to children's voices: Practices and problems, pitfalls and potentials. American Anthropologist, 109(2), 261–272. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.2007.109.2.261

- James, A., & Prout, A. (1990). Constructing and reconstructing childhood: Contemporary issues in the sociological study of childhood. Falmer.

- Johnson, L., & Kendrick, M. (2017). “Impossible is nothing”: Expressing difficult knowledge through digital storytelling. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 60(6), 667–675. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaal.624

- Karlsson, L. (2013). Storycrafting method – To share, participate, tell and listen in practice and research. The European Journal of Social & Behavioural Sciences, 6(3), 497–511. https://doi.org/10.15405/ejsbs.88

- Karlsson, L., Lähteenmäki, M., & Lastikka, A. (2019). Increasing well-being and giving voice through story crafting to children who are refugees, immigrants, or asylum-seekers. In K. Kerry-Moran & J. A. Aerial (Eds.), Story in children's lives: Contributions of the narrative mode to early childhood development, literacy and learning (pp. 29–54). Springer.

- Kaukko, M. (2017). The CRC of unaccompanied asylum seekers in Finland. The International Journal of Children’s Rights, 25(1), 140–164. https://doi.org/10.1163/15718182-02501006

- Kaukko, M., & Wilkinson, J. (2020). ‘Learning how to go on’: Refugee students and informal learning practices. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 24(11), 1175–1193. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2018.1514080

- Kaukko, M., Wilkinson, J., & Kohli, R. (2021). Pedagogical love in Finland and Australia. A study of refugee children and their teachers. Pedagogy, Society and Culture, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2020.1868555

- Kohli, R. (2006). The sound of silence: Listening to what unaccompanied asylum-seeking children say and do not say. British Journal of Social Work, 36(5), 707–721. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bch305

- Leavy, P. (2015). Method meets art. Art based research practice. The Guilford Press.

- Leavy, P. (2016). Fiction as research practice. Routledge.

- Lenette, C. (2019). Arts-based methods in refugee research. Springer.

- Lenette, C., Brough, M., Schweitzer, R. D., Correa-Velez, I., Murray, K., & &Vromans, L. (2019). ‘Better than a pill’: Digital storytelling as a narrative process for refugee women. Media Practice and Education, 20(1), 67–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/25741136.2018.1464740

- Lenette, C., & Cleland, S. (2016). Changing faces: Visual representations of asylum seekers in times of crisis. Creative Approaches to Research, 9(1), 68–83.

- Lähteenmäki, M. (2012). Sadutus turvapaikanhakijalapsuuden ilmentäjänä. In Kommentti: nuorisotutkimuksen verkkokanava. Nuorisotutkimusseura.

- MacIntyre, A. C. (2013). After virtue. Bloomsbury.

- Malkki, L. (1996). Speechless emissaries: Refugees, humanitarianism, and dehistoricization. Cultural Anthropology, 11(3), 377–404. https://doi.org/10.1525/can.1996.11.3.02a00050

- Mayes, E. (2019). The mis/uses of ‘voice’ in (post)qualitative research with children and young people: Histories, politics and ethics. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 32(10), 1191–1209. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2019.1659438

- McIntyre, J., & Abrams, F. (2020). Refugee education. Theorising practice in schools. Taylor and Francis.

- McIntyre, J., Neuhaus, S., & Blennow, K. (2020). Participatory parity in schooling and moves towards ordinariness: A comparison of refugee education policy and practice in England and Sweden. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 50(3), 391–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2018.1515007

- Monash Lens. (2018). New animated film created with primary school students from refugee backgrounds. https://www.monash.edu/education/news/new-animated-film-created-by-refugee-children.

- Montgomery, E. (2011). Trauma, exile and mental health in young refugees. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 124, 1–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01740.x

- Nunn, C. (2010). Spaces to speak: Challenging representations of Sudanese Australians. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 31(2), 183–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/07256861003606366

- Polkinghorne, D. E. (2007). Validity issues in narrative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 13(4), 471–486. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800406297670

- Rajaram, P. (2002). Humanitarianism and representation of the refugee. Journal of Refugee Studies, 15(3), 247–265. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/15.3.247

- Riihelä, M. (2001). The storycrafting method. Increasing children's participation. Stakes.

- Roy, L., & Roxas, K. (2011). Whose deficit is this anyhow? Exploring counter-stories of Somali Bantu refugees’ experiences in ‘doing school. Harvard Educational Review, 81(3), 521–541. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.81.3.w441553876k24413

- Satchwell, C., Larkins, C., Davidge, G., & Carter, B. (2020). Stories as findings in collaborative research: Making meaning through fictional writing with disadvantaged young people. Qualitative Research, 20(6), 874–891. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794120904892

- Silvennoinen, P. (2011). Storycrafting the elderly. Interdisciplinary Studies Journal, 1(2), 28–33.

- Strekalova-Hughes, E. (2019). Unpacking refugee flight: Critical content analysis of picturebooks featuring refugee protagonists. International Journal of Multicultural Education, 21(2), 23–44.

- Strekalova‐Hughes, E., & Peterman, N. (2020). Countering dominant discourses and reaffirming cultural identities of learners from refugee backgrounds. The Reading Teacher, 74(3), 325–329. https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1944

- Spyrou, S. (2021). A preliminary call for a critical public childhood studies. Childhood, 28(2), 181–185. https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568220987149

- Spyrou, S., Rosen, R., & Cook, D. T. (2019). Reimagining childhood studies. Bloomsbury Academic.

- Tracy, S. J. (2010). Qualitative quality: Eight “Big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(10), 837–851. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800410383121

- UNHCR. (2019). Global trends. Forced displacement in 2018. UNHCR.

- Vannini, P. (2019). Doing public ethnography. Routledge.

- Vecchio, L., Dhillon, K. K., & Ulmer, J. B. (2017). Visual methodologies for research with refugee youth. Intercultural Education, 28(2), 131–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2017.1294852

- Wang, X. C., Strekalova-Hughes, E., & Cho, H. (2019). Going beyond a single story: Experiences and education of refugee children at home, in school, and in the community. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 33(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/02568543.2018.1531670

- Wernesjö, U. (2012). Unaccompanied asylum-seeking children: Whose perspective? Childhood, 19(4), 495–507. https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568211429625

- Wilkinson, J., Santoro, N., & Major, J. (2017). Sudanese refugee youth and educational success: The role of church and youth group in supporting cultural and academic adjustment and schooling achievement. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 60, 210–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2017.04.003

- Winskell, K., & Enger, D. (2014). Storytelling for social change. In K. Wilkins, T. Tufte, & R. Obregon (Eds.), The handbook of development, communication and social change (pp. 189–206). John Wiley & Sons.

- Yosso, T. (2005). Whose culture has capital? A critical race theory discussion of community cultural wealth. Race Ethnicity and Education, 8(1), 69–91.