ABSTRACT

According to the Council of Europe, educators lack awareness on the topic of digital citizenship education and its importance to educate youngsters to move critically in a highly digitalized world. It is a core component of Digital Citizenship Education (DCE) to promote democratic competences, including critical reflection, the development of social and intercultural competences, critical thinking and media literacy. Bearing this in mind, a Teacher Training Package (TTP) was developed, aiming to promote professional development and qualification of pre- and in-service Foreign Language teachers as well as teacher trainers, as far as DCE is concerned, namely, pedagogical methodologies, practices and resources. Our study focuses on the Free Online Training Course for Self-guided Professional Development (part of the TTP), which directly approaches teachers’ professional knowledge. The analysis of the Teaching Units designed by the teachers and of their final course reflections suggest the relevance of the training course for the teachers’ professional development. Those who took part in the course highlighted the pertinence of the topic and underlined the relevance of having had contact with theoretical information and resources, which allowed them not only to reflect on their current practices but also to consider ways of introducing DCE in their lessons.

1. Digital citizenship education

1.1. The concept

Digital Citizenship Education (DCE) has emerged as a supranational priority, seeking to empower younger citizens to participate actively and responsibly in a digital society and to foster their skills to use digital technologies effectively and critically (Richardson & Milovidov, Citation2019). In order to facilitate the implementation of DCE in schools and in curricula across Europe, subject- specific adaptations are required (Frau-Meigs et al., Citation2017).

In recent years European institutions have produced three main frameworks regarding digital competences, digital citizenship education and democratic competences, namely a DCE Handbook (Richardson & Milovidov, Citation2019).

The first one, the European Digital Competence Framework (DigComp), released in 2013, is a reference framework created by the European Commission to offer a common comprehensive understanding of what digital competences are (Punie et al., Citation2013). It was updated in March 2022 (Council of Europe, Citation2022), as it is seen as an important guide for educators that provides a simple understanding of a list of digital knowledge, skills and domains to be addressed with students. The digital competence “involves the confident, critical and responsible use of, and engagement with, digital technologies for learning, at work, and for participation in society. It includes information and data literacy, communication and collaboration, media literacy, digital content creation (including programming), safety (including digital well-being and competences related to cybersecurity), intellectual property related questions, problem solving and critical thinking.” (Council Recommendation on Key Competences for Lifelong Learning, 22 May 2018, ST 9009 2018 INIT) (Vourikari et al., Citation2022, p. 3).

Another important framework to work for DCE is the Reference Framework of Competences for Democratic Culture (RFCDC), elaborated in 2015 and enriched in the following years with other publications. It describes the 20 competences that students need to be able to be part of democratic and culturally diverse society, where people can live peacefully together. It is divided in four areas: values, attitudes, skills, and knowledge and critical understanding (Council of Europe, Citation2018a, Citation2018b) and there are clues on how to assess them (Council of Europe, Citation2021).

The third framework is the DCE conceptual framework, visually represented as a “temple”, whose foundations lay on the democratic competences of the RFCDC. Five constructs emerge as being essential in developing effective digital citizenship practices. These are depicted as pillars in this structure. The competences for democratic culture lay the foundation for digital citizenship, the five pillars uphold the whole structure of digital citizenship development, and they consist of policies, stakeholders, strategies, infrastructures, resources, and evaluation. As a result, a competence framework, encompassing 10 domains grouped in three fundamental areas, was elaborated. The three main areas include: - being online, wellbeing online and rights online.

The number of hours that an individual spends in an educational environment throughout his school life is considerable. Furthermore, to educate for values and responsibilities has a prolonged impact on the existence of a citizen, influencing their decisions and actions both online and offline.

Since it is a specific and particular place to educate for the crossing of cultures, the foreign language classroom is a great circumstantial context to start the discussion about digital citizenship, especially regarding respect for others, for cultural and linguistic differences, fighting racism, xenophobia or other restrictive worldviews, but also within other different themes and curricular contents. In fact, according to Porto et al. (Citation2017, p. 2) “language teaching can and should contribute to educational processes, to the development of individuals and to the evolution of societies”.

This shows the importance of the FL teacher in the development of students’ citizenship, even more when considering how important it is nowadays to address these issues of citizenship. As Byram refers (2001, p.102 as cited in Byram et al., p. 2017), “language teaching as foreign language education cannot and should not avoid educational and political duties and responsibilities”.

Communication in today’s world involves both language competences and digital literacies, which are essential for learners to understand, interpret, manage, share and create meaning in the constantly growing world of digital channels and online media.

However, according to the Council of Europe (Citation2019) there is a “lack of awareness among educators of the importance of digital citizenship competence development for the well-being of young people growing up in today’s highly digitalized world” (p. 9).

2. Teacher education

As digitalization evolves and pervades today’s world, the more relevant the discussion surrounding digital competences and digital citizenship education becomes. In fact, “Digital competence has become a major focus in educational policies in the past few years as a result of a technology-driven society and workplace” (Lucas et al., Citation2021, p. 2), especially when it comes to the need to help teachers develop competences that allow them to fully explore digital technologies and their potential in educational settings (Lucas & Moreira, Citation2018).

As professionals committed to teaching, teachers must be able to use digital technologies with sound pedagogy to enhance students’ learning and facilitate their development of digital competence. As citizens, teachers need to be equipped with this competence to participate in various facets of society (Krumsvik, Citation2014; Redecker, Citation2017).

Digital competence and its relevance have therefore gained a pivotal role in education and have become central in professional development debates (MIND the gaps, Citation2019). As Ferrari (Citation2012) defines it, “Digital Competence is the set of knowledge, skills, attitudes (thus including abilities, strategies, values and awareness) that are required when using ICT and digital media to perform tasks; solve problems; communicate; manage information; collaborate, create and share content; and build knowledge effectively, efficiently, appropriately, critically, creatively, autonomously, flexibly, ethically, reflectively for work, leisure, participation, learning, socialising, consuming, and empowerment.” (p. 45).

Not only teachers need to develop their own digital competences, as this will allow them to make better use of technologies (in life and in teaching), but most importantly they need to be aware of the teaching opportunities that must be created to help students navigate the digital world(s).

In fact, it is crucial that teachers have the ability to endow their students with the necessary tools that will allow them to make the right decisions when using technologies. This will help them optimise their learning opportunities, limit virtual risks (both physical and psychological health), as well as provide them with competences for the defense and respect of their digital rights and for correct and respectful online behaviour, as it is clear that digital citizenship is fundamental for an active and meaningful participation in today’s world.

As school curricula integrate digital citizenship, teachers should have specific training opportunities, so that they can prepare their students for an active, responsible, and healthy integration in the current society. It is thus crucial to foster professional development contexts in which DCE is addressed.

According to OECD (Citation2018) professional development (PD) consists of “activities that aim to develop an individual’s skills, knowledge, expertise and other characteristics as a teacher” (p. 11), including several types of activities which can be formal or non- formal and are essential to improve the quality of education. However, teachers today are faced with new challenges and PD opportunities must meet the new demands.

One of the challenges faced by teachers today is related to time constraints. According to the TALIS survey, half of the teachers present “conflicts with their work schedule as a barrier to participating in professional development activities.” (OECD, Citation2019).

This report, which focuses on innovative and emergent practices of teacher Continuous Professional Development (CPD) and professional learning by teaching professionals who work in compulsory education, highlights the need for new answers when it comes to CPD programmes. As such, there is the need to rethink the design of teachers’ CPD, so that the programs offered comply with teachers’ needs and constraints. In these cases, offering teachers’ professional development and learning opportunities online in a paced (fixed start and end date) or self-paced mode (any time) provides ways to remove the barrier of time conflict.

One of the possibilities of CPD programs may be the online format, which reaches a large number of participants. In the above-mentioned study, in Portugal (ex.9), but also in Sweden (ex.1), Slovenia (ex.12) and Slovakia (ex.27), the online format has reached greater number of participant teachers. It is known that these online programmes should consider teachers’ background (experience, skills, needs, expectations) and present design elements (e.g., interactive videos) that motivate teachers to continue to participate in the course (Qian et al., Citation2018).

According to Jones and Dexter (Citation2014), another important stand in teachers’ professional development is the possibility to engage in independent teacher learning programs, where teachers participate on their own initiative and follow their own pace. A recent OECD publication also highlighted the enhancement of content knowledge and skills, as wells as the impacts in the teachers’ professional identity, self-reflection, confidence, and other, as results of their participation in CPD online program. (Minea-Pic, Citation2020).

It was according to the above-mentioned evidence brought by recent research, that some decisions were taken as far as the creation of the DiCE.Lang training course is concerned: i) the online format; ii) the self-study and autonomous mode and the iii) creation of contexts/platforms for sharing practices on DCE.

2.1. Free online training course for self-guided professional development

The Free Online Training Course for Self-guided Professional Development, directly approaches teachers’ professional knowledge in the DCE domain.

This Free Online Training Course is an opportunity for teachers to reflect on the importance of Digital Citizenship in the FL teaching and learning and think about possibilities of how to adapt and apply them in view of local curricular contexts.

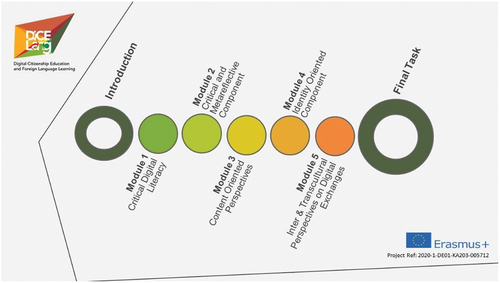

The course was created by the University of Aveiro and the University of Limerick on Moodle, with a specific domain https://dicelang-edu.com/my/. When the participants enter the course, they have access to an overview of the course and of its modules: the Welcome page, where they can find information related to the DiCE.Lang project (its aims and the course structure), an Introduction module (with self-reflection tasks on DCE), five modules related to the five categories of digital citizenship conceptualized in this project, and a module for the development of the final task, as shown in .

Each module presents documents, resources and entails two tasks, which aim to introduce teachers to the concept of DCE and its policy framework, to promote the development of methodologies and resources related to the DCE in FLE and to reflect on their own (past, present and future) practices, qualifying them in this area. To conclude the training course, teachers have to design a teaching unit suitable for their own classes and write a final reflection.

Each of the five modules correspond to the five domains of DCE created within the DiCE.Lang project: Module 1- Critical Digital Literacy, Module 2 - Critical and Meta Reflective Component, Module 3 - Content Oriented Perspectives, Module 4 - Identity Oriented Component and Module 5 - Inter & Transcultural Perspectives on Digital Exchanges. In each module participants are guided through a set of diverse practical and reflexive tasks aimed at the development or improvement of the teachers’ competences regarding methodologies, resources and activities to be put in practice in the foreign language classrooms to approach this topic with their students.

Before the modules, there is an Introduction to DCE, where the concept of DCE is presented in different ways.

The different Modules are easily accessible, just by clicking on the respective pages. The structure of each Module is similar: a short video about the concept behind that unit, two tasks in which one is more reflective and the second one more practical, and the “Dig Deeper” (), with extra material or resources to be approached within the topic.

All the information and instructions needed for the completion of the course are given in short video tutorials or PDF scripts.

To conclude the training course, teachers have to design a teaching unit suitable for their own classes and write a final reflection.

3. Methodology

As far as methodology is concerned, for this paper we analyzed two main types of documents: the 12 Teaching Units (TU) created by the participants in the Free Online Training Course for Self-guided Professional Development, and the 12 final reflections they had to write at the end of the course. The 12 TU had to follow the sample guidelines provided and the final reflection had no outline in terms of what to reflect on.

The analysis consisted mainly of a content analysis, where the main categories were previously defined (Bardin, Citation1977).

In terms of the TU, we analyzed the data concerning: the target public (level of proficiency); the DCE goals and domains; the type of the language domains and the type of resources.

Concerning the reflections, the focus was on: teachers’ motivation, the inputs/gains and possible constraints.

4. Discussion and conclusions

When analyzing the 12 TU, some aspects may be clearly outlined:

In general, most of the teachers seem to have got acquainted with the concept of DCE and were able to create activities for their own students, which addressed DCE in FL lessons.

Only two of the teachers seem to have had difficulties in incorporating the theoretical framework provided as far as DCE is concerned, having created TU whose aims do not include explicit reference to the DCE framework and domains, and to the RFCDC. Two other teachers were able to create activities and define aims that are related to DCE, but do not specify the DCE domain where to incorporate it. The DCE domains that are referred to in the TU are (in some cases one teacher may refer to more than one): COP (N = 4); CMC (N = 2), IOC (N = 1) and CDL (N = 1).

In terms of target public, all the TU are designed to be used with students whose level of proficiency is B1/B2, which may indicate that teachers have some difficulty in envisioning the possibility to address DCE with lower-level students.

As far as the curricular content is concerned, half of the teachers relate the TU to Teens and Technology, since six of the TU address the theme of social media, including for instance the topics of time spent online, addiction, e-safety, digital world and tools, among others. Five teachers create their TU addressing the issue of sustainability, namely, environmental awareness.

One must notice that these are the units where active participation/take action is highlighted, namely with activities where pupils are asked to engage in the creation of campaigns (for example: “investigation of and reflection on an environmental issue while creating a call-for-action campaign that will involve the use of digital technology to educate others and advocate for change”), resources (for instance: “write an article in the school newsletter where students can contribute with tips to avoid social media addiction” or “create an infographic to share with your family about time spent online”, using digital tools. One must notice the clear articulation established of this active participation with the RFCDC item: “Reflect on the use of the Internet to work towards activism and positive social changes”).

In terms of the language items chosen by the teachers, six TU refer to activities involving the four domains (speaking, listening, writing and reading), whereas three do not mention the listening (but list the other 3) and one does not indicate the writing. Two of the teachers decided not to include that information in the TU.

When analyzing the 12 reflections written by the teachers at the end of the Free- online training course, we can see that the motivations to participate in the course vary, and range from broad motivations, such as, professional development (N = 3), development of digital competences (N = 1), to more specific motivations, such as the need to respond to the new challenges posed by the ever-growing digitalisation of the world, or because DCE in FL is perceived as a new and pertinent topic (N = 6) to be approached. Five of the teachers who participated in the Free-online training course specifically mention their need to deepen knowledge on the topic of DCE within the context of FL, both theoretically and didactically. One of the teachers also mentions the role FL may have in addressing issues which are relevant to the development of competences that go beyond the linguistic ones, stressing their motivation to participate as linked to the role FL teaching can have on the development of the students’ critical awareness.

The reports of the 12 teachers also focused on the gains they have achieved through their participation in the training course.

Eight of the teachers stress the fact that their theoretical knowledge on the topic has been strengthened, namely through the contact with the European frameworks, whereas six of the participants highlight the development of new ways to bring the topic into the classroom, thus referring to the didactic development the course has provided, which allows them to feel more able to bring the topic into the classroom. Two of the participating teachers mention as a strong point of the course the ability to contact with materials, namely teaching units, as a great asset and a professional gain.

Another relevant aspect mentioned by two of the teachers has to do with the ability to reflect on their current practices, in a critical and reflective attitude. One teacher specifically mentions the role of the course on their professional development, and another one specifies that the course provided for the development of digital literacy. Lastly, one teacher also mentions that the course has provided a reflection on the need to have a more proactive attitude in the development of the students’ digital skills.

One should also note that all the teachers stress the importance of the training/education for their professional development, as noted in their reports when saying that the course “was fundamental”, that it met their expectations and, even, one of the teachers mentions the course exceeded their expectations, whereas another one says the course made them feel empowered. One of the teachers explicitly refers to the fact that the course “contributed to the change needed in education in developing DCE in students”. Another relevant aspect that deserves highlight is the fact that three of the teachers refer to the peer context and that they wish to share the knowledge developed through the course within their school contexts. These last remarks are in line with studies that suggest that the “Outcomes derived from participation in online learning activities can extend beyond the more conventional set of professional development activities related to improvements in teacher knowledge and changes in teaching practices (Yurkofsky et al., Citation2019).

5. Conclusion remarks

The results indicate that the course can be a successful training opportunity for teachers, since it contributed to their professional development, namely as far as DCE in FL is concerned, as we can see in the teaching units they created as a final task of the course.

As a pilot, we have gathered valuable information, which provides fruitful insights to future training opportunities outline:

the importance of the course design and structure, namely, the advantages of online and self-study/autonomous options;

the need of organizational support when creating the course; the relevance of assuring that teachers possess the needed digital competences to participate in the course (as in Flanigan, Citation2011);

the creation of possible digital environments for teachers to share ideas, practices and resources;

the concern about news forms of accreditation across Europe, for instance the use of Open Badges, an informal but verifiable digital recognition of skills and achievements, for those who complete their open online courses.

In fact, the investment in professional development that is effective and accessible has been one of the major concerns when it comes to school policy. It is our belief that, as our results indicate, online training, at the teachers’ own pace, enabling them to overcome potential constraints, and allowing them to critically engage in activities that foster their knowledge and competencies, is a solution that should be sought and effectively constructed. In Portugal, this modality is not yet recognized as accredited training that allows teacher to progress in their careers, despite recent pilot projects regarding this issue (cf. http://www.dge.mec.pt/noticias/os-mooc-na-formacao- continua-de-professores-questoes-desafios-e-respostas-evento-online-do). The same concerns have been part of international agendas with examples coming from Spain (INTEF) or France (EMPAN MOOC), highlighting that teachers are demanding new approaches to their training and that new answers must be provided.

The pilot of our course, whose results we discussed in this paper, is evidence that teachers can effectively develop their skills and competences through this modality (in particular when it comes to DCE within FL) and, furthermore, that they embrace and value these new formats of teacher training.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Bardin, L. (1977). The content analysis. PUF.

- Council of Europe. (2018a). Reference framework of competences for democratic culture - Context, concepts and model (Vol. 1). Council of Europe Publishing.

- Council of Europe. (2018b). Reference framework of competences for democratic culture – Descriptors of competences for democratic culture (Vol. 2). Council of Europe Publishing.

- Council of Europe. (2019). Digital citizenship education handbook. Council of Europe Publishing.

- Council of Europe. (2021). Assessing competences for democratic culture. Principles, methods, examples. Council of Europe Publishing.

- Council of Europe. (2022, June 30). Digital citizenship education project (DCE) – 10 domains. https://rm.coe.int/10-domains-dce/168077668e

- Ferrari, A. (2012). Digital competence in practice: An analysis of frameworks. JRC-IPTS.

- Flanigan, R. L. (2011). Professional learning networks taking off. Education Week, 31(9), 10–12.

- Frau-Meigs, D., O’Neill, B., Soriani, A., & Tomé, V. (2017). Digital citizenship education – Overview and new perspectives (Vol. 1). Council of Europe.

- Jones, W., & Dexter, S. (2014). How teachers learn: The roles of formal, informal, and independent learning. Educational Technology Research & Development, 62(3), 367–384. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-014-9337-6

- Krumsvik, R. J. (2014). Teacher educators’ digital competence. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 58(3), 269–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2012.726273

- Lucas, M., Bem-Haja, P., Siddiq, F., Moreira, A., & Redecker, C. (2021). The relation between in-service teachers’ digital competence and personal and contextual factors: What matters most? Computers & Education, 160, 160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2020.104052

- Lucas, M., & Moreira, A. (2018). DigCompEdu: quadro europeu de competência digital para educadores. UA.

- MIND the gaps. (2019). Youth digital citizenship education. European Commission.

- Minea-Pic, A. (2020). Innovating teachers’ professional learning through digital technologies. OECD Education Working Papers, No. 237. OECD Publishing,

- OECD. (2018). TALIS Teacher Questionnaire. How teachers learn: The roles of formal, informal, and independent learning.

- OECD. (2019). TALIS 2018 results (volume I): Teachers and school leaders as lifelong learners. TALIS, OECD Publishing. https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/1d0bc92a-en

- Porto, M., Houghton, S., & Byram, M. (2017). Intercultural citizenship in the (foreign) language classroom. Language Teaching Research, 22(5), 484–498. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168817718580

- Punie, Y., Brecko, B., & Ferrari, A. (Eds.). (2013). DIGCOMP: A framework for developing and understanding digital competence in Europe, EUR 26035. Publications Office of the European Union.

- Qian, Y., Hambrusch, S., Yadav, A., & Gretter, S. (2018). Who needs what: Recommendations for designing effective online professional development for computer science teachers. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 50(2), 164–181.

- Redecker, C. (2017). European framework for the Digital Competence of Educators. DigCompEdu. Publications Office of the European Union. https://doi.org/10.2760/178382

- Richardson, J., & Milovidov, E. (2019). Digital citizenship education handbook: Being online, well-being online, rights online. Council of Europe.

- Vourikari, R., Kluzer, S., & Punie, Y. (2022). DigComp 2.2. The digital competence framework for citizens with new examples of knowledge, skills and attitudes. Publications Office of the European Union.

- Yurkofsky, M., Blum-Smith, S., & Brennan, K. (2019). Expanding outcomes: Exploring varied conceptions of teacher learning in an online professional development experience. Teaching and Teacher Education, V.82, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.03.002