ABSTRACT

Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine published a famous demolition of John Keats’s poetry in August 1818. The same issue also announced its hostility to John Ferriar’s Essay towards a Theory of Apparitions (1813). Ferriar’s essay treated visionary experience as a form of hallucination, ‘a waking dream’ whose causes were not essentially different from other physical diseases. This lecture explores the intersecting trajectories of Keats and Ferriar – who died in 1815 just as the poet started his medical training at Guy’s – to suggest both responded to the emergent science of mind in the period not as a demystification but rather a re-enchantment of imaginative life.

In August 1818, Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, a new kid on the block of reviewing, making a name for itself for its cutting and slashing attacks on new writing, published its famously devastating attack on John Keats’s poetry.Footnote1 Damning Keats’s association with the liberal circle involved with Leigh Hunt’s Examiner, John Gibson Lockhart’s review was part of a series of assaults on what Blackwood’s derided as ‘The Cockney School of Poetry’. Keats’s medical training brought him in for special treatment. Blackwood’s suggested that Keats had unwisely quit medicine because he had fallen victim to ‘Metromanie’, the craze for writing metre it described as ‘the most incurable’ of ‘all the manias of this mad age’:

His friends, we understand, [wrote Lockhart with a sneer] destined him to the career of medicine, and he was bound apprentice some years ago to a worthy apothecary in town. But all has been undone by a sudden attack of the malady to which we have alluded. (519)

Keats’s poetry becomes the symptom of an underlying cultural malaise that manifests as a kind of mania. One imagines Keats read the review with eyes swimming. Quite likely stunned, he would have continued flipping the pages as he processed his feelings. If he did, he would have come across a review of a collection of supernatural tales called Phantasmagoriana (coincidentally, a volume that Mary Shelley acknowledged as an influence on Frankenstein).Footnote2 The reviewer, this time J. H. Merivale, continued in the pugnacious register that distinguished Blackwood’s, but his animus was not directed towards the book under review this time. Instead, he opens with an assault on the theories of John Ferriar’s Essay towards a Theory of Apparitions, published five years earlier in 1813.Footnote3 Assuming his readers had a degree of familiarity with Ferriar’s book, Merivale presented it as an ‘invasion’ of ‘the empire of imagination’, an act of medical disenchantment that claimed to use physiological maladies to explain away ‘all cases of spectral appearances, invisible spiritual agency, and magical delusion’ (589). Returning to Ferriar after spending some pages exploring the ghost stories gathered in Phantasmagoriana, Merivale declared his ‘decided anti-ferriarism’, and confirmed his faith instead in the autonomy of ‘that noble faculty of our souls, the imagination’ (595). Merivale presented himself as a defender of wonder against the medical disenchantment of ‘the physician or moralist’ who explains all such narratives as the product of ‘hallucination’, a word that in the 1810s was virtually synonymous with Ferriar’s name:

There is too much philosophy stirring in our days […] too much for the free indulgence of our poetical power. Nay we are not sure that but we may call the whole world at present a world of accountants and botanists. (595)Footnote4

Who would not give their assent to such an appeal? Surely Keats the poet would have agreed? But in this lecture, I am going to suggest – on the contrary – that Keats was more likely to have felt sympathy with John Ferriar, fellow-victim of the Blackwood’s scourge.

What Merivale’s account of Ferriar’s Essay represses is that the physician presented his ideas not as a scientific disenchantment of the universe, not as reducing the imagination to the ills of the body, but as the opening up of an entirely new field of imaginative possibility. Ferriar even begins Essay on Apparitions by presenting himself as a kind of Gothic novelist: ‘Take courage, then, good reader, and knock at the portal of my enchanted castle’ (ix). A knowledge of the physiological bases of hallucinations does not close down the imagination, Ferriar claims, but creates a new resource for it:

The highest flights of imagination may now be indulged […] great convenience will be found in my system; apparitions may be evoked, in open day […] Nay, a person rightly prepared may see ghosts, while seated comfortably by his library-fire, in as much perfection, as amidst broken tombs, nodding ruins, and awe-inspiring ivy. (vii–viii)

Clearly well-read in the vogue for Gothic tales soon to produce Frankenstein, he was dismissive of the mechanical contrivances used to explain away the experiences of supernatural terror to which Gothic novelists subjected their heroines.

I have looked, also, with much compassion, on the pitiful instruments of sliding pannels, trap-doors, backstairs, wax-work figures, smugglers, robbers, coiners, and other vulgar machinery, which authors of tender consciences have employed, to avoid the imputation of belief in supernatural occurrences. So hackneyed, so exhausted had all artificial methods of terror become, that one original genius was compelled to convert a mail-coach, with its lighted lamps, into an apparition. (vi)

The true power of ‘our terrific modern romances’ (33), as he called Gothic fiction, ought to come from the workings of the mind. Ferriar’s ideas in this area have been granted an important place in the history of medicine. Richard Hunter and Ida MacAlpine’s classic Three Hundred Years of Psychiatry (1982), for instance, describes Ferriar as the first to give apparitions ‘an entirely physio-pathological explanation’, but their rather dour summary says nothing about the way his essay offered ‘to the makers and readers of such stories, a view of the subject, which may extend their enjoyment far beyond its former limits’ (vi).Footnote5 Ferriar jokingly claimed for himself ‘the honors due to the inventor of a new pleasure’ (v) – and with it came an invitation to experiment that I am going to suggest Keats accepted in some of his greatest poems.

***

Before jumping to Keats’s poetry, I want to spend a bit more time with Ferriar’s Essay towards a Theory of Apparitions, a text that was still familiar enough to the poet’s circle to be set out in a summary paragraph in the Examiner in 1823.Footnote6 What this brief summary necessarily omits is Ferriar’s characteristic witty and provocative manner. Ferriar began his thesis by affirming the ‘undeniable fact, that the forms of the dead, or absent persons have been seen and their voices have been heard, by witnesses whose testimony is entitled to belief’ (13). Apparitions, he claimed, were not feigned by impostors, but a real pathological experience, experienced in the senses and felt on the body. Ferriar’s key claim, as the Examiner summary noted, was that the experience of apparitions and spectres was the product of renewed impressions that retained a presence in the mind ‘more durable than the application of the impressing cause’ (16). What we see, he is claiming, remains with us beyond the immediate sensory impression and thereby remains available as a resource for hallucinations triggered by illness, including forms of morbid obsession, or ‘scenes of domestic affliction, or public horror’ (17), what we might today call trauma. As proof of the durability of impressions, he adverted to Erasmus Darwin’s discussion of the ocular spectra and ‘the well-known experiment of giving a rotatory motion to a piece of burning wood, the effect of which is to exhibit a complete fiery circle to the eye’ (19). The ‘renewal of impressions formerly made by different objects’, claimed Ferriar, ‘may be truly called a waking dream’ (19, 20).

These secondary impressions did not necessarily replay as they were experienced. Apparitions were not just copies. Ferriar believed that ‘a morbid disposition of the brain is capable of producing spectral impressions, without any external prototypes’ (99). ‘Composed of the shreds and patches of past sensations’, the allusion to Hamlet was characteristic of Ferriar, they were part of everyday life, experienced by everyone: ‘there are, perhaps, few persons who have not occasionally derived entertainment from it’ (19, 20). Everyone also experienced them by way of what Freud would later call ‘the Dream-work’:

From this renewal of external impressions, also, many of the phaenomena of dreams admit an easy explanation. When an object is presented to the mind during sleep, while the operations of judgment are suspended, the imagination is busily employed in forming a story, to account for the appearance, whether agreeable or distressing. (17)

Hallucinations, from this perspective, were a pathological extension of the Dream-work and other non-pathological mental processes that had trespassed into conscious life. Ferriar’s Essay is concerned not with insanity as such here, despite his role as director of the asylum in Manchester, but cases where dreams appeared in the experience of those who seemed otherwise sane.Footnote7 To use Ina Ferris’s words, writing about Ferriar’s influence on Sir Walter Scott, ‘these images appeared within the scene of the real’, creating a territory that corresponded to the half-world of waking dreams explored by so much of Keats’s poetry.Footnote8

Ferriar’s interest in this area was built on a lifetime of clinical experience as a physician in Manchester.Footnote9 From the late 1780s, he had been at the centre of a reforming push in the city’s infirmary to improve provision for the poor, opposed by the town’s entrenched Tory hierarchy as inaugurating ‘a Medical Republic of the worst kind’.Footnote10 He and his mentor Thomas Percival were responsible for the first fever hospital in Manchester, in the face of opposition from the same quarters, and then managed to set up a Board of Health to co-ordinate the town’s medical provision (the first in the country). Ferriar had been drawn to Manchester like many Edinburgh-trained doctors because of the opportunities created by the population boom associated with the early years of the industrial revolution. He explored the medical consequences in a series of essays on the typhoid epidemic of 1789 and 1790, on the ‘Origin of Contagious and New Diseases’ and ‘Of the Prevention of Fevers in Large Towns’ published in the three volumes of his Medical Histories and Reflections (1792–8, reissued with a fourth volume in 1810). His essays ‘Advice to the Poor’ and ‘Of the Treatment of the Dying’ were widely applauded for their liberal approach to their topics (the latter is still mentioned today in discussions of palliative care).Footnote11

Like his friend and mentor Percival, Ferriar had been a student of the Edinburgh professor William Cullen whose lectures treated health not simply as a matter of disease but of complex ‘proximate’ and ‘remote’ causes that might inhere in the body or in external phenomena (like social conditions). The result was that Ferriar viewed the human body as a porous and responsive organism whose state was, in Kevis Goodman’s words, ‘delicately calibrated to and contingent upon movements outside and well beyond it’.Footnote12 Consequently, there was no mental disorder that could not produce physical effects or vice versa. His influential essay ‘On the Conversion of Diseases’, a term he is credited with introducing to psychiatry, discussed cases where in the course of one illness apparently independent symptoms could manifest in other parts of the body, including, for instance, in his words, ‘the production of melancholy and madness, by the suppression of eruptions, or the healing of old ulcers’.Footnote13 One can see here the medical foundations of his more sportive writing in the Essay on Apparitions. His essay ‘Epidemic Fever of 1789 and 1790’ had included a lack of proper food and sleeping in sodden cellars among the causes of the typhoid epidemic of 1790, but added to these physical causes ‘the constant action of depressing passions on the mind’.

These causes also increase the danger of the disease in a very great degree. I have seen patients in agonies of despair on finding themselves over-whelmed with filth, and abandoned, by everyone who could do them any service; and after such emotions I have seldom found them recover.Footnote14

For someone with Ferriar’s training, body and mind were assumed to be entangled in ways that had serious clinical consequences for the poor as much as the literary elite.

The Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society, founded in 1781, provided Ferriar with a venue in which to explore the implications of this approach beyond practical medical matters. The presence among its membership of students of Cullen like Ferriar and Percival helps explain the Manchester society’s broad interest in what their friend Thomas Cooper called ‘the phenomena termed mental’.Footnote15 Several of the papers given at the society approached topics like taste and imagination as forms of embodied experience. John Aikin – another physician – gave a paper on the impression of reality attending dramatic performances, read to the society in 1791 with Ferriar in the chair, arguing that people reacted to events in the theatre as if they were real because they triggered renewed impressions.Footnote16 Ferriar’s own contributions included papers on vitality or the principle of life, always a potentially controversial topic when there was any suggestion that the animating force had nothing to do the orthodox notions of the soul (an issue haunting the Blackwood’s response to the Essay on Apparitions).Footnote17 Generally speaking, Ferriar was careful not to step over those boundaries, unlike his friend Cooper, who ended up being driven into exile in the United States in 1794 for his religious and political opinions. Ferriar anyway had reservations about Cooper’s rather mechanistic reduction of the mind to the brain, but shared with his friend a scepticism about the abstraction of life from natural causes. A paper he gave to the Manchester society on ‘genius’ included a toilet joke about the Roman addiction to creating tutelary deities extending to inventing a goddess – Cloacina – to preside over what Ferriar called ’the least dignified of our natural functions.’Footnote18

Ferriar took a risk in the same essay when he hinted at the consequences of the influence of Plato on the development of Christianity. Essay towards a Theory of Apparitions encroached on similar ground when it identified ‘religious melancholy’ as ‘one of the most frequent causes of the Daemonomania’ (40), although he tried to insulate himself from any criticism on this front in his preface: ‘What methods may have been employed by Providence, on extraordinary occasions, to communicate with men, I do not presume to investigate’ (ix-x). He didn’t entirely succeed, not with the Quarterly anyway. Its querulous review implied that Ferriar ought to be careful about chipping away at ‘the universal belief in the immortality of the soul’, a warning that also haunts the hostile account in Blackwood’s.Footnote19 Both journals were always suspicious of the way The Examiner circle mocked pretensions to spiritual experience. They may have feared that Ferriar’s Essay was providing the group with ammunition, intentionally or not. Certainly William Hazlitt’s essay ‘On the Causes of Methodism’, first published in The Examiner in October 1815, seems to allude to Ferriar’s ideas when it judges:

The cold, the calculating, and the dry, are not to the taste of the many; religion is an anticipation of the preternatural world, and it in general requires, preternatural excitements to keep it alive. If it becomes a definite consistent form, it loses its interest: to produce its effect, it must come in the. shape of an apparition.Footnote20

The papers that Ferriar gave at Manchester nearly always had the same underlying interest in the entanglement of body and mind. The most important of these for today’s purposes was ‘Of Popular Illusions, and especially of Medical Demonology’, which opened up the territory he explored more fully in Essay towards a Theory of Apparitions twenty years later, but he also spoke about more directly literary topics.Footnote21 Laurence Sterne was a favourite author, unsurprisingly given the emphasis in Tristram Shandy on nervous sensibility and the hobby-horses of the mind. His friend Aikin’s paper on the theatre had included a digression on a passage in Sterne that he believed could trigger weeping through the renewal of impressions. Ferriar’s contribution to Sterne criticism included the discovery that the novelist had lifted some of the best known passages in Tristram Shandy from older writers like Robert Burton and François Rabelais (both of whom had a predilection for writing about the sensitive body and the way it affected and was affected by mental states). Similar interests are also apparent in his essay on Shakespeare’s contemporary Philip Massinger, another favourite of Keats’s. William Gifford’s 1805 edition of Massinger, reissued in 1813, included Ferriar’s essay as a preface. It seems likely Keats read it given the number of allusions to Massinger’s plays in his writing. Here is a passage from the essay that Samuel Taylor Coleridge transcribed into his notebooks c. 1808:

One observation however may be risked on our irregular and regular plays; that the former are more pleasing to the taste, and the latter to the understanding: readers must determine, then, whether it is better to feel, or to approve. Massinger’s dramatic art is too great, to allow a faint sense of propriety to dwell on the mind, in perusing his pieces he inflames or sooth[e]s, excites the strongest terror, or the softest pity, with all the energy and power of a true poet.Footnote22

When I first read it, I was immediately reminded of Keats’s famous letter on the camelion poet:

As to the poetical Character itself, (I mean that sort of which, if I am any thing, I am a Member; that sort distinguished from the wordsworthian or egotistical sublime; which is a thing per se and stands alone) it is not itself—it has no self—it is every thing and nothing—It has no character—it enjoys light and shade; it lives in gusto, be it foul or fair, high or low, rich or poor, mean or elevated—It has as much delight in conceiving an Iago as an Imogen. What shocks the virtuous philosopher, delights the camelion Poet.Footnote23

Ferriar himself wrote one influential poem: ‘The Bibliomania’, first published separately in 1809 before being included in the revised two-volume Illustrations of Sterne (1812).Footnote24 It sparked a rage for writing about the contemporary passion for collecting old books. Significantly, though, ‘The Bibliomania’ didn’t present the disorder as one from which Ferriar himself was exempt (anyone who had read his essays on Sterne could see the strength of his passion for old books). Ferriar tended not to present himself as the kind of scientific enquirer who was above and beyond the phenomena that he was observing.

***

I want to say something now about where and when Keats may have encountered Ferriar’s ideas. For several decades now, literary scholars have been interested in the way creative writers in this period started to be influenced by the emergence of a biological science of mind. Keats spent a year training as a physician at Guy’s under the guidance of major figures in the field like Sir Astley Cooper, so it’s hardly surprising that his poetry has attracted a lot of critical attention in this regard. Cooper took ‘a brain-based, corporeal approach to mind’, as Alan Richardson puts it, with an awareness of the way mental states could impact physical health.Footnote25 Keats made this note from Cooper’s lectures: ‘The Passions of ye Mind have great influence on the secretions, Fear produces increase Bile and Urine, Sorrow increases Tears.’Footnote26 One of Keats’s fellow students included an anecdote in his notes from Cooper’s lecture ‘On Sympathy’ about a man who came to St Thomas’s with a broken leg and died from fear a few days later with no symptoms of inflammation or any other unfavourable signs.Footnote27 One might recall Ferriar’s essay on contagious diseases and the fatal effects of despair on his patients. By the time Keats began his studies, Ferriar was an acknowledged authority in this field. His death in 1815, just a couple of weeks before Keats enrolled at Guys, was recorded in all the national newspapers, including The Examiner.Footnote28 Ferriar’s publisher Cadell and Davis took the opportunity to reissue his most influential works: An Essay towards a Theory of Apparitions, the two-volume Illustrations of Sterne, and the four-volume Medical Histories and Reflections. By November they had brought out an engraving of his portrait that was included in the following year’s Gallery of Contemporary Portraits.Footnote29

I first encountered Ferriar through my research into the role of medical men in the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society. Only somewhat later did I realize there was already a developed corpus of literary writing about Ferriar’s influence on, for instance, Sir Walter Scott’s historical novels and James Hogg’s psychological Gothic novel Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner, in which the protagonist may or may not be egged on to murder by a visit from the Devil.Footnote30 More delving revealed to me that Mary Shelley’s father William Godwin spent the day of 17 April 1816 reading Ferriar’s essay in one sitting.Footnote31 The assiduous researches of Nora Crook have revealed that Percy Shelley knew Ferriar’s Essay.Footnote32 Its role in the origin of Frankenstein is yet to be discussed, although the influence seems palpable to me, but perhaps even more surprisingly, given Keats’s medical training, little or nothing has been written on Keats and Ferriar. His name does appear in the long list provided in Hermione de Almeida’s monumental study Romantic Medicine and John Keats of those authors whose books were present on the shelves of the Physical Society while Keats was a student at Guy’s.Footnote33 These included the volumes of the Memoirs of the Literary and Philosophical Society of Manchester – with Ferriar’s essays in them, including the one on popular illusions – along with both the three- and four-volume Medical Histories and Reflections.Footnote34

The Physical Society was an extramural gathering of staff and students that met to discuss recent case histories. Its library provided access for students to expensive medical books. The Physical Society’s records, which still exist in the archives of King’s College London, offer no evidence that Keats was a member, but many of his friends were, and critics of Keats have long used its records to provide a rich context for his knowledge.Footnote35 Membership was not inexpensive and – in terms of borrowing books – it was enough for a friend to be a member to have access to its collection (no wonder it was constantly seeking the return of lost and stolen books). The Society’s catalogues don’t record a copy of Ferriar’s Essay towards a Theory of Apparitions, but then it was not the sort of expensive multi-volume book that students needed the library to help them access. Interestingly, though, a fellow student of Keats’s, Walter Cooper Dendy, wrote a ghost story called The Philosophy of Mystery (1841) that makes a reference to Ferriar’s ideas.Footnote36 Given that Hunt’s Examiner circle, including Shelley, was itself a book-sharing network, Keats may have come by a copy through that connection. Certainly Leigh Hunt’s new venture in 1823 The Literary Examiner felt able to assume that ‘most of our general readers are acquainted with the very acute and illustrative essay of Dr. Ferriar of Manchester’.Footnote37 Enough to say, then, that it seems likely Keats would have had access to Ferriar’s broader ideas at Guy’s, including the early essay on ‘Popular Illusions’, which may have encouraged him to investigate the elaborated version of its ideas in Essay towards a Theory of Apparitions, if only by borrowing it from his literary friends.

The most developed discussion of Ferriar’s influence on the period’s creative writers comes from scholars of Coleridge – whose engagement with the Massinger essay I have already mentioned – and stretches right back to the exhaustive account of the sources of the poet’s imagination in John Livingston Lowes’s study The Road to Xanadu (1927) and includes more recently Neil Vickers’s excellent Coleridge and the Doctors.Footnote38 Possibly because Coleridge was in Manchester in 1796 trying to sell subscriptions to his periodical The Watchman, he knew about and made use of the papers Ferriar gave to the Literary and Philosophical Society – volumes of which he later borrowed from the Bristol Library – on the vitalism debate, on Massinger, and, most importantly for today’s purposes, the one on ‘Popular Illusions’. Chris Murray has drawn my attention to an encounter between Coleridge and Keats on Hampstead Heath in April 1819 that may have drawn on the older poet’s knowledge of Ferriar.Footnote39 Obviously thrilled at his encounter with a literary celebrity, Keats gave an account of their meeting in a long letter to his brother and sister-in-law:

I met Mr Green our Demonstrator at Guy’s in conversation with Coleridge—I joined them, after enquiring by a look whether it would be agreeable—I walked with him a[t] his alderman-after dinner pace for near two miles I suppose In those two Miles he broached a thousand things—let me see if I can give you a list—Nightingales, Poetry—on Poetical sensation—Metaphysics—Different genera and species of Dreams—Nightmare—a dream accompanied <with> by a sense of touch—single and double touch—A dream related—First and second consciousness—the difference explained between will and Volition—so [many] metaphysicians from a want of smoking the second consciousness—Monsters—the Kraken—Mermaids—southey believes in them—southeys belief too much diluted—A Ghost story (2: 88–9)

Dreams, nightmares, second sight, ghost stories – questions of volition and sensation – were all topics covered in Ferriar’s writing on apparitions. Keats probably already knew as much, I have been suggesting, most likely from his student days, and quite possibly this previous interest was rekindled a few months earlier by the issue of Blackwood’s that had taken pot shots at both of them. Both Keats and Ferriar, those reviews suggested, were guilty of confounding the maladies of the body with the purity of the imagination.

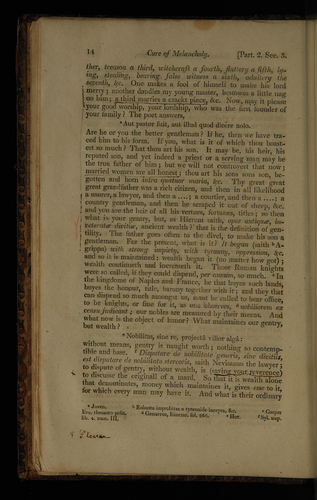

Murray follows Nicholas Roe and other scholars in identifying this encounter as a transformative moment for Keats, imparting energy to ‘the living year’, as it is called, when in an intense burst of creativity he wrote the poetry for which he is now best-known. ‘Poetry, poetical sensation and different kinds of dreams were all among his recent preoccupations’, writes Roe, who believes that the encounter helped trigger ‘Keats’s own remarkable resurgence of creativity’.Footnote40 These topics were also, of course, strongly identified with Ferriar’s name for contemporaries as was another name which came to preoccupy Keats in this period: Robert Burton, author of The Anatomy of Melancholy (1621). Only a few of the books Keats owned have come down to us, but among them is the second volume of a two-volume set of Burton’s Anatomy.Footnote41 Burton’s massive and rambling study is an early-modern medical treatise that explores the causes and symptoms of melancholy as a morbid obsession of the mind. The final part of Burton’s book focusses on two particular types – love melancholy and religious melancholy – of particular interest to Ferriar, who played his own small part in the revival of Burton’s reputation by revealing Sterne had liberally filched from him in the essay Keats may have encountered in the Physical Society’s library. I was able to examine Keats’s annotations to Burton thanks to access to the scan of the volume held at Keats House graciously facilitated by Ken Page.Footnote42 When it thunked onto my digital doormat, I was desperate to find ‘Ferriar’ scribbled in the margin, hoping to emulate Nora Crook’s recent recognition of Ferriar’s name in a previously misidentified Shelley annotation. Sadly, it isn’t there, whatever my wakeful dreams. The cold light of day, though, did reveal that the first word Keats wrote in his copy was ‘Sterne’ whose writing Ferriar had shown to be shot through with passages lifted from Burton ().

Figure 1. Keats’s annotation to his copy of Volume 2 of Robert Burton, Anatomy of Melancholy (London: Walker et al, 1813), 14. Image courtesy of Keats House, City of London Corporation. K/BK/01/015.

Later Keats also underlines the words ‘ride on’ in a passage from Burton that Ferriar had identified as another Sterne debt to Burton, an identification widely enough known to be re-circulated by The European Magazine in 1816.Footnote43 I should add that Keats also notes a couple of places where Burton seemed to have taken images from Massinger’s plays.Footnote44 The annotations to Burton are Keats’s own distinctive response to Anatomy of Melancholy, it provided the source for his poem ‘Lamia’, among other things, but they also suggest the hand of someone who had read Ferriar’s essays, at least those on Massinger and Sterne.

***

Let me come now to Keats’s poetry. Keats told his friend the painter Benjamin Robert Haydon ‘[the] truth is I have a horrid Morbidity of Temperament’ (1: 142). This temperament often manifested itself in a tendency towards over-intensive study, a species of readerly melancholy that Ferriar had identified as an important source of apparitional after-effects.Footnote45 Just such a scenario is explored in Keats’s ‘Dream after reading Dante’s Episode of Paolo and Francesca’ written out in the same letter to his brother and sister-in-law that described the encounter with Coleridge in Hampstead. The result is the kind of waking dream that registers the spectral after-effects of reading as bodily sensations:

Any encounter with An Essay towards a Theory of Apparitions would have intensified Keats’s self-consciousness about the way certain temperaments were prone to blur the boundaries between dreams and waking life. The porousness of this boundary is a salient feature of the poems of 1819 collected in the volume Lamia, Isabella, The Eve of St. Agnes and Other Poems (1820) Keats published shortly before his death. Was interest in the ‘waking dream’ the product of a re-connection with Ferriar? Reading through the issue of Blackwood’s that attacked his early poetry as a kind of mania, did its declared anti-ferriarism only serve to encourage him into the nexus of topics broached in his conversation with Coleridge a few months later? Did it also send him to Burton, whose influence on the 1820 volume has been so richly documented by Bob White?

Ferriar had specifically promised that his ideas offered new opportunities for the writers of ‘terrific modern romances’, a generic category often taken to encompass the three narrative poems that open Keats’s 1820 collection. ‘Romance’ was a term widely used to describe Gothic prose and narrative poetry in the period, set, like Keats’s three poems, in an alien past.Footnote47 Each of Keats’s romances centres around episodes where morbid obsession becomes the portal for the dream world to pass into everyday life. ‘Isabella’ retells a medieval tale from Boccaccio in which the heroine is visited by the spirit of her lover who has been murdered by her brothers. Grief turns into the kind of love melancholy described by Burton and Ferriar when she finds the body hidden in the forest, severs its head, and hides it in a pot of basil which she constantly waters with her tears until she pines away to death. ‘The Eve of St Agnes’ centres on the kind of incident Ferriar explored in the ‘Popular Illusions’ essay. Its heroine Madeline is convinced that she can conjure a vision of her lover if she observes certain superstitions:

Ferriar had claimed that ‘an attention to dreams and omens is one of the first acts of superstition’ and notes ancient authorities ‘directed certain forms and diet prior to sleep to induce dreams’. He also discusses the Swiss philosopher Lavater’s idea that the imagination of a sick or dying person, who longs to behold some absent friend, could trigger a situation where ‘impressions generally revive, and friends and relations rush upon us’.Footnote48 So too in her dream, Madeline seems to conjure the image of her lover, Porphyro, who turns out to have been hiding in her room all along, watching her undress:

This is the familiar Keatsian territory of the waking dream, where apparitions seem to be conjured by ‘love-melancholy’, although with the ironic disenchantment that the lover does appear in reality with sexual designs upon the dreamer.

In ‘Lamia’, there is a more explicit scene of disenchantment. Set in classical Greece, the story was taken from Burton, as Keats acknowledged in a note that described the titular figure as a ‘phantasm’, ‘Lamia’ tells the tale of a mortal who falls in love with a nymph disguised in human shape.Footnote49 In the source, the Lamia figure adopts the form of mortal women in order to ensnare and then devour her victims. In Keats’s poem the two lovers live together happily enough until the young man decides they should cross the threshold between the dream and the real world and marry in Corinth. There his former tutor – Apollonius – reveals Lamia’s true identity, but her exposure is treated by Keats – unlike his sources – as a cruel disenchantment by ‘cold philosophy’:

Of course, this charge was the one made in Blackwood’s against Ferriar. The charge itself was echoed by Leigh Hunt in a review of John Alderson’s An Essay of Apparitions (1823), a fairly reductive anticipation – or so the author claimed – of Ferriar’s ideas. Hunt’s dismissive review complained: ‘Our sole regret is on the score of the innumerable good stories which will shrink into most inelegant fiction, by the cold touch of a philosophy so inelegantly founded on mere matter of fact.’ Hunt distances Ferriar from Alderson at the beginning of the review as an author his readers would already know whose ideas had already ‘allayed all curiosity on the subject’.Footnote50 Evidently Ferriar was on Hunt’s mind around this time as a few months earlier he alluded to him in another short article mocking the superstitious beliefs of Prince Hohenlohe:

A very entertaining essay might be written on the physical properties of the imagination […] Dr Ferriar’s little work upon Apparitions may be thought to supply something towards such a production, but it is not sufficiently general, being rather a treatise on the delusion of the senses than an endeavour to trace the recondite operation of imagination on our physical energies.Footnote51

Here Ferriar is not seen as the dead hand of cold philosophy but as someone who has made a contribution to a larger project. I have been suggesting that Keats had already begun the task of pushing Ferriar’s ideas further by 1819.

I want to end with the idea that it is precisely this project that distinguishes the great odes published in the Lamia volume. In May 1818, Keats wrote to tell his friend J. H. Reynolds:

I am glad at not having given away my medical Books, which I shall again look over to keep alive the little I know thitherwards […] An extensive knowledge is needful to thinking people—it takes away the heat and fever; and helps, by widening speculation, to ease the Burden of the Mystery (1: 277)

Later in the same letter he returned to the last phrase, acknowledging its source in Wordsworth’s ‘Tintern Abbey’, but suggesting he might take the exploration of the mind further than his predecessor: ‘the World is full of Misery and Heartbreak, Pain, Sickness and oppression – whereby This Chamber of Maiden Thought becomes gradually darken’d and at the same time on all sides of it many doors are set open’ (1: 281). Ferriar did not provide a map for this exploration, but he did set up a signpost for further exploration.

Ferriar claimed that his system encouraged the ‘highest flights of imagination’, not least because it allowed apparitions to be ‘evoked, in open day’ (viii). A few pages later he describes how as a young boy he had been able to amuse himself by renewing an intense impression ‘with a brilliancy equal to what it had possessed in day-light, [that] remained visible for several minutes’ (17). Keats imagined a version of this scenario in ‘Ode on a Grecian Urn’ where a beloved object is projected into space before the poet. Most scholars now agree that Keats’s urn had no single ‘external prototype’ to use Ferriar’s phrase.Footnote52 Unlike his sonnet ‘On Seeing the Elgin Marbles’, which describes the ‘dizzy pain’ (11) induced by his close encounter with the marvels of Greek sculpture, the ode describes a ‘composite drawn from different sources’, ‘an ingenious illusion’, as Grant F. Scott describes it, renewing the impressions of ancient artefacts he has witnessed before in a new combination, turning in the air like an apparition before him.Footnote53 Tellingly, the apparition, which teases him into perplexity, is indexed against an awareness of suffering in the body that seems in some way to have produced its apparitional presence:

‘Ode to a Nightingale’ more explicitly traces the phantasmal experience at its heart to a desire to escape from the trauma of the suffering body:

‘Here’ might just as easily be scenes Keats encountered at Guy’s or the scenes Ferriar witnessed in the Manchester infirmary. Faced with this world of suffering, the song of the nightingale conjures an enchanted world ‘in faery lands forlorn’ (348, 70). This word ‘forlorn’ tolls the realization that ‘the fancy cannot cheat so well / As she is famed to do’ (73–4), and brings about the kind of disoriented return experienced by many of the figures in Ferriar’s case histories. With this return comes the question the physician had tried to answer in The Essay towards a Theory of Apparitions about the status of such experiences:

I have been suggesting that Ferriar’s answer to this question was double, not simply a disenchanting sense of the ‘cheat’ of such apparitional experiences, but also an encouragement to reorient poetry towards the exploration of this kind of mental process and its traumatic foundations.

Perhaps the most explicit dedication of Keats’s poetry to ‘the privilege of raising [ghosts] without offending against true philosophy’ (vii), to use Ferriar’s terms, comes in ‘Ode to Psyche’. ‘Psyche’ has long been identified with Keats’s medical education, primarily because its description of ‘the wreathed trellis of a working brain’ (60) draws on the vocabulary used to teach the anatomy of the brain at Guy’s.Footnote54 Critics have also identified the ode as a reconsecration of poetry towards Psyche, described in the poem as ‘latest born and loveliest vision far / Of all Olympus’ faded hierarchy’ (24–5) as if psychology in an embodied human mind were displacing an older kind of inspiration:

This ‘“untrodden” psychic region’, writes Alan Richardson, ‘not only gives poetic life to the newly complex brain revealed [by Keats’s teachers at Guys], but provides too a fresh canvas for Keats to exercise the imaginative powers he grounds in the embodied psyche’.Footnote56 Recall Ferriar’s impatience with the classical tendency to displace natural forces onto tutelary deities in his essay ‘On Genius’, a tendency his writing aims to reverse. Here Keats does much the same, presenting himself not as the temple-priest who worships a transcendent deity, but one who will commit himself to the exploration of the ‘untrodden’ regions of the mind.

I have no doubt that Keats was aware of Ferriar’s reputation on a wider scale as a physician who had not simply explored these avenues but had also seen medicine as entailing a social mission manifested most obviously in the Manchester Board of Health and its enquiries into the social conditions of the emergent industrial city. I find it hard not to think of Ferriar’s example in this regard when reading Keats’s self-castigating distinction between the dreamer and the poet in ‘The Fall of Hyperion. A Dream’:

Ferriar was a physician – and a poet himself – who was always interested in the imaginative capacity of the human mind as a source of both pain and pleasure in both medical and cultural contexts.Footnote57 He did not wish simply to disenchant the imagination by reducing it to a function of the body. Instead he opened up a new universe of wonder in the ‘wreathed trellis of a working brain’ based on an awareness of the power of the embodied mind to illuminate but also compound the weariness, the fever, and the fret. Keats pursued this avenue of enquiry even through the painful consciousness that tuberculosis would soon claim him. In March 1820, he wrote to Fanny Brawne: ‘I rest well and from last night do not remember any thing horrid in my dream, which is a capital symptom, for any organic derangement always occasions a Phantasmagoria’ (2: 277).

Acknowledgements

I’d like to thank James Grande for inviting me to give the Keats Memorial Lecture, to Neil Vickers for his kind introduction to the lecture, and also Katie Sambrook, Head of Special Collections at King’s College London, for giving me access to the Physical Society’s archives. Ken Page generously supplied me with scans of Keats’s annotations to Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy, among them the illustration for this lecture. I’d also like to thank Professor Bob White, who first taught me Keats over forty years ago, and whose recent book on Keats and Burton has been invaluable to this lecture. Email conversations with Bob and Chris Murray in Australia were great helps to preparing the lecture. Needless to say neither they nor any of the above are responsible for my own Ferriar-mania.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jon Mee

Jon Mee is Professor of Eighteenth-Century Studies at the University of York. He was formerly Professor of Romanticism at the University of Warwick, and Margaret Candfield Fellow in English at University College and Professor of the Romantic Period in the English Faculty at the University of Oxford. He has written several books on the eighteenth century and the romantic periods, including Dangerous Enthusiasm: William Blake and the Culture of Radicalism in the 1790s (Oxford, 1992), Romanticism, Enthusiasm, and Regulation: Poetics and the Policing of Culture in the Romantic Period (Oxford, 2003), Conversable Worlds: Literature, Community, and Contention, 1762-1830 (Oxford, 2011), and Print, Publicity, and Popular Radicalism in the 1790s: The Laurel of Liberty (Cambridge, 2016). His most recent book is Networks of Improvement: Literature, Bodies, and Machines in the Industrial Revolution (Chicago, 2023).

Notes

1 John Gibson Lockhart, ‘The Cockney School of Poetry,’ No. IV’, Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, 3.17 (August 1818): 519–24. Page references given in-text.

2 J. H. Merivale, ‘Phantasmagoriana,’ Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, 3.17 (August 1818): 589–96. Page references given in the main text. For the identification of Merivale as the author of the review, see A. L. Strout, A Bibliography of Articles in Blackwood’s Magazine, Volumes I through XVIII, 1817–1825 (Lubbock, Texas Technological College, 1959), 44. On the role of Phantasmagoriana in Frankenstein, acknowledged in Mary Shelley’s 1831 preface, see Maximiliaan van Woudenberg, ‘The Variants and Transformations of Fantasmagoriana: Tracing a Travelling Text to the Byron-Shelley Circle’, Romanticism 20.3 (2014): 306–20.

3 John Ferriar’s An Essay towards a Theory of Apparitions (London: Cadell and Davis, 1813). Page references to Ferriar’s Essay are given in the main text from this point onwards.

4 On the association of Ferriar’s name with the word ‘hallucination’, see Terry Castle, ‘Phantasmagoria: Spectral Technology and the Metaphorics of Modern Reverie,’ Critical Inquiry, 15, no. 1 (1988): 55n.

5 Richard Hunter and Ida MacAlpine (eds), Three Hundred Years of Psychiatry, 1535–1860 : A History Presented in Selected English Texts (Hartsdale, N.Y: Carlisle Pub., 1982), 543.

6 ‘Newspaper Chat,’ The Examiner, March 16, 1823, 187.

7 For discussions of Ferriar’s work at the asylum, see Leonard Smith, Lunatic Hospitals in Georgian England, 1750–1830 (Routledge: New York and London, 2007) and Roy Porter, Mind-Forged Manacles. A History of Madness in England, from the Restoration to the Regency (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1987). Smith, 69, notes that Ferriar, as one might expect, treated mental illness as ‘closely aligned with physical disorders’.

8 Ina Ferris, ‘“Before Our Eyes”: Romantic Historical Fiction and the Apparitions of Reading,’ Representations 121, (2013): 64.

9 For a detailed account of Ferriar’s career in Manchester, see Jon Mee, Networks of Improvement: Literature, Bodies, and Machines in the Industrial Revolution (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2023), especially Chapter 3.

10 Manchester Mercury, March 17, 1789.

11 On the last, see, for instance, Harold Y. Vanderpool, Palliative Care: The 400-Year Quest for a Good Death (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, Incorporated, 2015).

12 Kevis Goodman, Pathologies of Motion: Historical Thinking in Medicine, Aesthetics, and Poetics (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2023), 46.

13 John Ferriar, ‘Of the Conversion of Diseases,’ in Medical Histories and Reflections, 3 vols (London: Cadell and Davis, 1792–8), 2: 47.

14 Ferriar, ‘Epidemic Fever of 1789 and 1790,’ in Medical Histories and Reflections, 1: 139.

15 Thomas Cooper, ‘Sketch of the Controversy on the Subject of Materialism’, in Tracts Ethical, Theological and Political … . Vol.1. (London: J. Johnson, 1789), 167. No second volume was published. Cooper migrated to the United States with Joseph Priestley in 1794.

16 John Aikin, ‘On the Impression of Reality Attending Dramatic Representations’, Memoirs of the Literary and Philosophical Society of Manchester, 4 (1793): 96–108. It was advertised as the first paper in the 1791–2 season by the Manchester Mercury, 4 October 1791. The paper was read at the Society on 7 October.

17 See Ferriar, ‘Observations on the Vital Principle’, and ‘An Argument against the Doctrine of Materialism’, Memoirs of the Literary and Philosophical Society of Manchester 3 (1790): 216–4 and 4 (1793): 20–44. These essays were written as part of an ongoing debate with his friend Thomas Cooper, see the discussion in Mee, Networks of Improvement, 118–20.

18 ‘On Genius’ in Illustrations of Sterne, 2 vols, 2nd edn (London: Cadell and Davis, 1812), 2: 165.

19 ‘An Essay towards a Theory of Apparitions. By John Ferriar, M.D.’, Quarterly Review, 9.18 (July 1813): 312. Jonathan Cutmore, Contributors to the Quarterly Review: A History, 1809–1825 (London: Pickering and Chatto, 2008), 129, identifies William Stewart Rose as the reviewer.

20 Hazlitt’s essay appeared in ‘The Round Table’ series in the Examiner, 22 October 1815, 685. The Examiner certainly regularly tracked cases of religious enthusiasm, or what it called ‘supernatural pretensions of every kind’ (The Examiner, 9 May 1813, 300). On 11 September 1814, for instance, in one of a series of reports about Joanna Southcott, it reported in Ferriar-like terms that she was ‘no impostor’ but ‘labours under a strong mental delusion’ (588).

21 ‘Of Popular Illusions, and especially of Medical Demonology,’ Memoirs of the Literary and Philosophical Society of Manchester 3, (1790): 31–116.

22 ‘Essay on the Dramatic Writings of Massinger’, ibid: 125. For Coleridge’s use of the passage, see The Notebooks of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, vol. 3, 1808–1819, ed. Kathleen Coburn (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1973), 3445. Ferriar’s essay appears in full in The Plays of Philip Massinger, ed. William Gifford, 4 vols (London: 1805), 1: lxxxvii–cxxvii.

23 To Richard Woodhouse, 27 October 1818, The Letters of John Keats 1814–1821, 2 vols, ed. H. E. Rollins (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1958), 1: 386–7. Further references to the letters appear in the text.

24 The Bibliomania, an Epistle to Richard Heber, Esq. (London: Cadell and Davis, 1809).

25 Alan Richardson, British Romanticism and the Science of the Mind (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 120.

26 Hrileena Ghosh, John Keats’ Medical Notebook: Text, Context, and Poems (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2020), 41.

27 [Anon.] ‘The Lectures of Astley P Cooper, Esq, on Surgery, given at St Thomas’s Hospital. Volume the 1st. GB 0100 G/PP2/10. Guy’s Hospital Medical School Records, King’s College London.

28 The Examiner, February 19, 1815, 128.

29 The three books were advertised together, for instance, in The St James’s Chronicle, 26–28 September and The Star, 29 September 1815. The engraving by Bartolozzi after a drawing by Thomas Stothard was issued on 15 November 1815 and gathered into the Gallery of Contemporary Portraits No. XXI with images of Byron and others. Both were later included in the first volume of The British Gallery of Contemporary Portraits, 2 vols (Cadell and Davis: London, 1822).

30 For discussions of Ferriar and Scott, see Ferris, ‘“Before Our Eyes”’. On his influence on Hogg, see Michelle Faubert, ‘John Ferriar’s Psychology, James Hogg’s Justified Sinner, and the Gay Science of Horror Writing’, in Romanticism and Pleasure, ed. Faubert and Thomas H. Schmid (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 83–108, and Megan Coyer, ‘The Embodied Damnation of James Hogg’s Justified Sinner’, Journal of Literature and Science, 7.1 (2014), 1–19.

31 Godwin wrote ‘Ferriar, on Apparitions, pp. 139’ in his entry for the day. See The Diary of William Godwin, ed. Victoria Myers, David O’Shaughnessy, and Mark Philp (Oxford: Oxford Digital Library, 2010) <http://godwindiary.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/diary/1816-04-17.html>; (accessed October 31, 2023) and the discussion in David O’Shaughnessy’s ‘Godwin, Ireland, and Historical Tragedy’ in New Approaches to William Godwin: Forms, Fears, Futures, ed. Eliza O’Brien, Helen Stark, and Beatrice Turner (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2021), 27.

32 Nora Crook, ‘Shelley and his Waste-Paper Basket: Notes on Eight Shelleyan and Pseudo. Shelleyan Jottings, Extracts, and Fragments’, Keats-Shelley Review, 25 (2011): 68–78.

33 Hermione de Almeida, Romantic Medicine and John Keats (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991), 30.

34 See ‘A Numerical Catalogue of Books in the Library of the Physical Society, Guy’s Hospital’, 1817 and ‘A catalogue of books in the library of the Physical Society, Guy’s Hospital, 1850’, both at King’s College London. The catalogue record for the first edition of Ferriar’s Medical Histories and Reflections in the Physical Society Collection is at <https://librarysearch.kcl.ac.uk/permalink/44KCL_INST/1el9h9v/alma990006255270206881>. This also had the fourth volume of the later addition added. A set of the later edition of 1810–13 from the historical library of St Thomas’s Hospital, is at <https://librarysearch.kcl.ac.uk/permalink/44KCL_INST/1el9h9v/alma990006257700206881>.The Physical Society’s set of the first five volumes of Memoirs of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society is at <https://librarysearch.kcl.ac.uk/permalink/44KCL_INST/1el9h9v/alma990006057400206881>.

35 See ‘Minutes Book of the Physical Society of Guy’s Hospital 1813–20’, GB 0100 G/S4/M9, King’s College London. The best account of the society as a context for Keats remains John Barnard’s ‘John Keats in the Context of the Physical Society, Guy’s Hospital, 1815–1816’ in John Keats and the Medical Imagination, ed. Nicholas Roe (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), 73–89.

36 Walter Cooper Dendy, The Philosophy of Mystery (London: Longman & Co., 1841), 11, 150, and 351. Dendy claimed to have seen Keats ‘in the lecture-room of Saint Thomas’s […] in a deep poetic dream: his mind was on Parnassus with the muses’. He listed the poet among those who ‘leave the lone heart to prey on its own sensibility’, 99. The veracity of Dendy’s account of seeing Keats in the lecture theatre has been disputed. See the discussion in Donald C. Goellnicht, The Poet-Physician: Keats and Medical Science (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1984), 35–6.

37 ‘An Essay on Apparitions. By Dr. John Alderson, M. D.’, The Literary Examiner, 6 December 1823, 362.

38 See John Livingston Lowes, The Road to Xanadu: A Study in the Ways of the Imagination (London: Constable, 1927), 471 and 500, and Neil Vickers, Coleridge and the Doctors (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 52 and 101. For a fuller discussion of the Ferriar-Coleridge connection, see Mee, Networks of Improvement, 123–4.

39 See Chris Murray, ‘“Death in his hand”: Theories of Apparitions in Coleridge, Ferriar, and Keats’, Nineteenth-Century Literature, 78.3 (2023): 179–210.

40 Nicholas Roe, John Keats: A New Life (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012), 308–9.

41 See the discussion in R. S. White, Keats’s Anatomy of Melancholy: ‘Lamia, Isabella, The Eve of St Agnes and Other Poems’ (1820) (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2020).

42 The annotations are reproduced in The Complete Works of John Keats, ed. H. Buxton Forman, rev. M. Buxton Forman, 8 vols (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1938), 5: 306–20, but the underlining and other markings are omitted.

43 Burton, Anatomy, Keats House, City of London Corporation. K/BK/01/015, 186. Ferriar identified this passage as the origin of the Lady Baussiere story in Tristram Shandy. See Ferriar, Illustrations of Sterne, 2: 95–8. Acknowledging that Ferriar had noticed the parallel ‘upwards of twenty years’ earlier in the essay published in Memoirs of the Literary and Philosophical Society of Manchester, the two passages were printed side by side in ‘To the Editor’, European Magazine, 69 (1816), 320.

44 Anatomy of Melancholy, Keats House, 404 and 444.

45 Ashley Miller, ‘“Striking Passages”: Memory and the Romantic Imprint’, Studies in Romanticism, 50.1 (2011), 31, notes the tendency among the period’s scientists of mind for linking spectral illusions with reading, ‘so that hallucination seems to take as inspiration the materiality of the page, which seems to possess the memory (and thus, according to these materialist physiologists, the body) of its reader’. Miller describes Ferriar’s Essay as a ‘seminal’ (39) text for this tendency.

46 John Keats, The Complete Poems, ed. John Barnard, 3rd edn (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1988), 334. Quotations from the poems are to this edition with lines or stanza numbers given in the text.

47 See White, Keats’s Anatomy of Melancholy, 5.

48 Ferriar, ‘Of Popular Illusions’, 26–7 and 83.

49 Lamia, Isabella, The Eve of St Agnes, and Other Poems (London: Taylor and Hessey, 1820), 45.

50 ‘Essay on Apparitions’, Literary Examiner, 6 December 1823, 366 and 361. Alderson claimed to have read his ideas to a literary society in 1810 before Ferriar published his Essay. Hunt doesn’t give any sign of knowing the much earlier essay on popular superstitions Ferriar had given to the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society.

51 ‘Prince Hohenlohe – The Royal Touch’, Literary Examiner, 9 August 1823, 87.

52 Grant F. Scott, The Sculpted Word: Keats, Ekphrasis, and the Visual Arts (Hanover: University Press of New England, 1994), 133.

53 Ibid.

54 Goellnicht, Poet-Physician, 136–9; Richardson, Science of the Mind, 124–5; and Ghosh, John Keats’s Medical Notebook, 191–2.

55 See John Barnard, John Keats (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987), 100–4; Richardson, Science of the Mind, 125, among many others, with many differences as to the exact terms of the reconsecration.

56 Richardson, Science of the Mind, 127.

57 The snide article ‘Manchester Poetry’, Blackwood’s, 9.49 (April 1821) excepted Ferriar’s ‘elegant mind and varied researches’, 66, from its general mockery of the idea of the industrial city producing poetry of literary merit.