Abstract

Since 1978, Mainland China has transformed cities into attractive branding engines to satisfy political and economic agendas at an unprecedented speed and scale. However, what is often concealed is that China’s urban growth has been achieved thanks to the invaluable efforts of migrant workers. Treated as undesirable urban aspects and erased from the city due to their rural origins and low education, migrants’ labour has been crucial to the building of new cities and infrastructure. To shed light on these social dynamics, I investigate the representation of migrant workers through visual arts. Informed by semi-structured interviews with contemporary artists and visual analysis, this article offers an insight into the official narrative and the socio-spatial inequalities brought about by urbanisation. Lastly, it contributes to the contemporary visual art discourse, outlining different representational and creative strategies, from erasure to socially engaged works, which evoke migrant workers’ social and transformative potential.

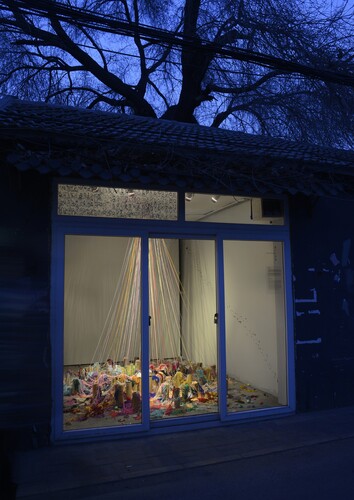

Ma Yongfeng, Ma Yongfeng's tag with Li Zhan's words, mixed media, installation, 2011, part of SSR&D's Beijing Project n.02, Invest in Contradiction, 新“大字报”, image: courtesy of Alessandro Rolandi

Since 1978, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has entered a new phase in history marked by extensive reforms and global exposure. As the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) and the Maoist era came to an end, Deng Xiaoping’s Open Door Policy (1978) allowed Mainland China to enter the international market and undergo unprecedented urban transformation.Footnote1 In a few decades, high-rise buildings and skyscrapers sprouted from the rubble, efficient urban infrastructure was set up to tackle traffic congestion, and entire new cities were built to compete internationally. In 2001, as the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) included urbanisation in the tenth Five Year Plan, China also entered the World Trade Organization (WTO) and, consequently, increased the speed and scale of urban transformations until 2008, the year of the Beijing Olympics and the global economic crisis. Over less than forty years, China turned from being a largely rural nation into a world power, and produced a range of globally competitive cities through incessant and strenuous efforts.Footnote2

The exceptionality of China’s urban development, with its overwhelming scale and pace, has attracted much scholarly attention. The abundant literature that studies urban planning often involves the analysis of economics and policymaking, together with a historical approach that highlights the fast shift from the Maoist to the contemporary era.Footnote3 Additionally, an increasing number of studies have analysed the social contradictions and inequality brought about by urbanisation.Footnote4 As some people became rich overnight thanks to China’s reforms, a new social class emerged: migrant workers.Footnote5 Migrant workers, floating population, cheap labour, and rural workers are only some of the different terms used to refer to those individuals who temporarily come from the countryside to find a job in the city. They often reside in the peripheries, where they can float between rural and urban. This new social class is ‘treated as inferior second-class citizens deprived of the right to settle in cities and to most of the basic welfare and government-provided services enjoyed by urban residents’.Footnote6

Despite migrant workers’ voices being largely underexamined in the scholarly and public debate, their persona has been created based on widespread prejudices and biased news reporting. Investigating the reputation and social stigma of rural migrants, Chen et al identified the stark role played by the ‘local newspapers, magazines, television programs, and radio programs’ in shaping, spreading, and perpetuating certain narratives around migrants.Footnote7 Their interviews with urban residents in Beijing in 2004 indicated that migrant workers are often perceived as ‘inferior, incapable, cheating, violent, stealing, robbing, killing, setting off fires’.Footnote8 Similarly, Wanning Sun advances that journalists depict migrant workers either with pity or fear and, overall, prioritise ‘conflict, action, and spectacle’.Footnote9 With regards to the general public, Chun Wing Tse reports that the more educated and wealthier the urban resident, the more prejudiced they are against migrant workers.Footnote10 In a very recent study, Jiang et al discovered that urban residents still consider migrants ‘as a threat to urban society, blaming them for a plethora of social problems such as unemployment, congestion, environmental degradation, and crime’.Footnote11

Drawing from mobility studies, the dominant narrative around migrant workers in China can be easily explained. Indeed, Cresswell argues that ‘the drifter, the shifter, the refugee and the asylum seeker have been inscribed with immoral intent. So, too, the travelling salesman, the gypsy-traveller, and the so-called wandering Jew’.Footnote12 Often residing in the cities without the right permission and working precariously, China’s migrant workers are associated with transience, irregularity, poverty, crime. Furthermore, they are looked down on for their lack of, or low, education and money-driven attitude. While rural–urban migration is not unique to contemporary China, the scale is certainly unprecedented and has intensified several common problems associated with migration, including ‘unequal opportunities in employment, medical services and children’s education’, to name a few.Footnote13 Indeed, migrants’ illegality in the city and informal housing have earned them an association with other irregular settlements in developing countries, such as slums, shantytowns, and bidonvilles to name a few.Footnote14 This reference has instigated international demands for the central government to regulate land and society.Footnote15 Ultimately, the problem is not so much the physical as the symbolic existence of migrants, which stands for inefficient governmental control, and can consequently undermine China’s modern and appealing national image, as well as negatively impacting foreign investments.Footnote16

Therefore, the strategy of erasure should be understood as a symbolic and political preventative measure to safeguard the aims of the party – in this case, a ‘harmonious society’. The principle of ‘harmonious society’ calls for an equal and fair Chinese society. It was firstly advocated by former president Hu Jintao amidst China’s urban and economic growth and has been revived by the current Chinese president, Xi Jinping, as part of the official propaganda of the China Dream. The China Dream has become synonymous with President Xi and stands for a ‘national dream shared by all the Chinese people’.Footnote17 Part of Xi’s mission to pursue the China Dream, the principle of ‘harmonious society’ is a long-time imperative of the CCP to reduce the increasing socio-economic inequalities between rural and urban areas and maintain social order. As the existence of migrant workers – as a signifier of unfair social conditions – risks compromising the legitimacy of the CCP and China’s social stability, erasure turns into a significant quick-fix.

Indeed, Groys suggests that the power of ideology ultimately lies in its vision.Footnote18 The aesthetic and visual language in the city becomes one way in which the party-state promotes the China Dream and the image of a socially cohesive nation, specifically through attractive and persuasive images that, consciously or not, penetrate urban dwellers’ imagination.Footnote19 Due to the high number of visual experiences in the urban space, the central government seems to exacerbate politics’ own aesthetic dimension. For instance, local authorities and urban planners increasingly commission distinctive skylines to implant a carefully designed vision of their cities and future. On the other hand, there are also street managers whose duty includes painting over illegal advertisements on the walls and overlooking the public space.Footnote20 This particular instance speaks to Rancière’s ‘distribution of the sensible’. By theorising a specific aesthetic-political system that defines what is visible and audible, Rancière argues that ‘the ability or inability to take charge of what is common to the community’ is determined by certain powerful actors.Footnote21 In his words, ‘aesthetics is a delimitation of spaces and times, visible and invisible, speech and noise that simultaneously determines the place and the stakes of politics as a form of experience’.Footnote22 In the Chinese urban context, this aesthetic-political regime is upheld by the central government and locally enforced by the authorities. In this light, the symbolic, cultural and visual erasure of rural migrants and the continuous shift from concealed to apparent, illegal to legal can be viewed as the performative actions of officials who want to impose a certain aesthetics and politics, and the grassroots who, in turn, attempt to subvert their own condition of invisibility.

Through the lens of contemporary visual arts, this article offers an insight into non-mainstream representations of migrant workers and the socio-spatial inequalities brought about by urbanisation. Specifically, this paper identifies three artistic forms. First, there are works that conceal and avoid referring to the floating population and, hence, reiterate the widespread strategy of erasure. Secondly, there are artistic practices that use the tropes of invisibility and darkness to offer a more nuanced view of migrant workers. Contrary to the clear-cut portrayals of rural migrants as either dangerous or pitiful, these artistic practices acknowledge their hardships whilst recognising the agency of this under-represented social group. In this middle section, the hidden potential of migrants takes shape and alludes to the possibilities and stimuli that being invisible involves, including the ability to set up informal housing or the extreme strategies to be heard. Last, there are socially engaged projects and art spaces that include or are mostly formed by migrants. In these latter cases, erasure constitutes the motivation for and backdrop of more hopeful, collective and creative expressions. By exploring the tensions between rural/urban and visible/concealed, the argument moves from erasure towards an increasing awareness and potentiality.

This article is divided into three sections, which reflects the three stages of erasure. First, I give an overview of the government’s social and land regulations since the Open Door Policy and introduce the artwork by Wang Wei, followed by a mention of Liu Bolin. In the second section, I examine works by Hu Weiyi and Jiang Zhi in relation to migrants’ housing and the potential inherent within erasure. The last section is dedicated to art spaces and projects – the Migrants’ Culture and Art Museum, Handshake 302, and Social and Sensibility Research & Development – which give voice to, and enhance the creativity of, the floating population through workshops, museums and educational projects. For the purpose of this article, I will concentrate on artworks playing with the concept of erasure, and prioritise the practices by artists I interviewed in 2019 during my fieldwork in Beijing and Shanghai.

Erased

Before delving into an historical overview of the emergence of migrant workers, it is worth better defining this social figure. Indeed, it is necessary to distinguish two types of migrants: the ones that move to the city and cannot ‘access public and commercial housing in state redistribution and formal market’;Footnote23 and those who are englobed by the city and informally build houses to fulfil the housing demands.Footnote24 During China’s unprecedented urbanisation, as the central and local governments supported the development of metropolises, entire rural villages were encroached by the expanding urban area. Deprived of their lands, those villagers previously working in the fields suddenly found themselves in a fast and ever-changing reality that prioritised the secondary and tertiary sectors at the expense of agriculture. This induced rural villagers to ‘construct illegally’ and make profit from renting.Footnote25 Alongside local villagers, who often became landlords, shareholders, and entrepreneurs and are more likely ‘to make use of their ‘local’ resources and opportunities’,Footnote26 there are rural migrants. The latter are often grouped together according to shared geographical origins, dialect and even skills.Footnote27 Whereas migrant men have been mostly exploited in high-intensity jobs, female workers are often recruited in the clothing, textiles, food processing and sex industries.Footnote28 Whilst there is an obvious difference in the degree of segregation experienced by both rural migrants and villagers, they have both emerged alongside China’s urban transformations and are subject to discrimination.

The problems associated with the flows of rural workers into the city are a direct consequence of China’s numerous land and social reforms at the end of the twentieth century, which were motivated by economic and urban interests. Although land consistently belonged to the party-state, since 1979 the central government has leased its land-use rights to make profits. By 1982, the Chinese territory was either labelled as ‘urban’, or ‘rural’.Footnote29 Rural lands were owned by the state and only leased to villagers. These land reforms deliberately coincided with the industrialisation process of the 1970s and the subsequent shift of focus from rural to urban.Footnote30 As the expansion of cities was given priority, the land-use rights of villagers were often expropriated, and croplands reallocated.Footnote31 Although this strategy aimed at relieving the widening social and economic gap between urbanities and countryside, the creation of a land lease market in the 1980s contributed to the capitalisation of rural land and the escalation of inequalities.Footnote32

The hukou system, namely household registration system, has further exacerbated this social and spatial fragmentation. Originally heralded as a census tool, it was established in 1958 by the central government to monitor Chinese migration.Footnote33 Assigned either a rural or urban citizenship, residents can access welfare, education, health and other state-provided services only from their designated area. However, more than a census tool, Ma and Wu suggest that the hukou is reminiscent of the popular baojia system deployed during the Song dynasty (960–1279) ‘to maintain local control and mutual surveillance’.Footnote34 Throughout the years, the central government has intermittently tightened and eased rural–urban migration in an attempt to sustain economic growth while relieving socio-spatial inequalities. In the 1970s, it was the central authorities that overlooked any shift from rural to urban hukou and temporarily allowed rural migrants into the city to fulfil unwanted work.Footnote35 In Guangzhou, Lin, de Meulder and Wang report that it was ‘only a minority of highly educated and skilled migrants’ that could easily acquire access.Footnote36 Later, in the 1980s and 1990s the process was simplified, and local governments increasingly gained decisional power. In Shenzhen, O’Donnell explains that with the development of the housing market, acquiring a property would guarantee the buyer an urban hukou.Footnote37 Today, in many Chinese cities, university graduates are also offered urban status.Footnote38

Scholars agree that the hukou has supported the unprecedented scale of China’s urbanisation, arbitrarily allowing rural migrants into the city whilst denying them social and spatial rights. Since 2012, the central government has set the goal of reducing the rural–urban gap and promoted the relaxation of the hukou system in line with the ideological imperative of a ‘harmonious society’. For instance, in 2014, the central government promoted the shift from rural to urban status for those with stable employment in cities and towns.Footnote39 However, the study published by Li et al in 2023 indicates that the liberalisation of the household registration system does not necessarily encourage the shift from rural to urban status.Footnote40 Furthermore, while policies have a more immediate implementation and impact, it takes longer to erase discrimination and reshape dominant narratives around migrant workers.Footnote41

Alongside the attempts to reform the household registration system, since the 1990s local authorities have implemented cleansing campaigns and urban renewal projects to fight the unattractiveness associated with migrant workers and achieve an attractive city in aesthetic, symbolic and economic terms.Footnote42 For instance, in Guangzhou, the city government has promoted the elimination of the ‘Three Olds’, namely old villages, old urban districts, and old factories.Footnote43 The top-down cleansing campaigns reduce the risk of hindering the glossy image of a modern, socially stable and economically secure nation. They remove the sight of clustered housing and irregular businesses and often upgrade the infrastructure and sanitary conditions of certain neighbourhoods. However, they only temporarily relieve the city centres from the presence of informal workers as migrants settle somewhere else. Overall, the ‘discriminatory mechanism[s]’Footnote44 are still in place and remain talent oriented.Footnote45

Since the 1990s, numerous artists have engaged with rural migrants and reflected on their unjust social conditions through performance (eg Song Dong, Zhu Fadong, Liu Zedan), installation (eg Wang Wei, Zhang Dali), film (eg Jia Zhangke) and photography (eg Wang Jin, Zhang Huan). However, I argue that the contemporary art discourse on the severity of migrant workers’ social and spatial segregation still remains underexplored compared to other social concerns. This has to do with artists’ individual inclinations and perhaps with practical difficulties in approaching migrants. Moreover, though the widespread prejudices towards migrants might not be directly linked to the low artistic engagement, it might have played a more substantial impact on the artistic tropes and strategies. Indeed, several artists tackle this social concern by reinforcing erasure. This is the case of artist, Wang Wei, who was born in 1972 in Beijing. He graduated from the Fresco Painting Department at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, Beijing, in 1996, which perhaps instilled in him his interest in space and public works. Since then, Wang’s practice has often enquired into quotidian life and ‘the plurality of sensual experiences’ in the urban space.Footnote46

On the occasion of his first solo exhibition, ‘Temporary Space’ (2003), at Long March Space in 798 Art District, Beijing, Wang showcased a multimedia work that claims to reflect on urban transformations rather than Chinese migrants.Footnote47 It included three different elements: an installation, a video projection and twelve photographs. The two-week-long installation 25,000 Bricks was built by ten migrant workers and consisted of a square measuring ten by ten metres with four-metre-high walls. Throughout the fourteen days, workers collected bricks from rubble sites and piled them up into walls while Wang took pictures of the process.Footnote48 On the day of the opening, the figures of the workers had already disappeared, and the bricked structure occupied almost the entire gallery, leaving only a one-metre-wide corridor from each side of the built square. Alongside the installation, a series of twelve photos and an eight-minute video marked the absence of the workers. Whereas the former captured the overall building process, the video focused on the village of Dong Ba, from where the workers collected the bricks.Footnote49 The day after the opening, the bricked structure was suddenly knocked down under Wang’s instruction and migrants started collecting bricks all over again.

The curator of ‘Temporary Space’, Philip Tinari, asserts that the performance was not judgemental or nostalgic about the constant demolitions, nor did it touch upon migrant workers’ exploitation.Footnote50 Likewise, the artist himself reinforces that the show was not directly referring to workers’ social condition and inequality.Footnote51 However, I advance that his exhibition and statement can be revealing of how the presence of migrant workers has been treated. Despite his denial, Wang’s installation 25,000 Bricks is reminiscent of the concealment of China’s cheap labour by performing the disappearance of migrants’ persona. In the white cube, as workers erect the four bricked walls around themselves, their bodies gradually vanish until they are buried behind the red bricks. Likewise, migrants working in the city become invisible against the glossy and shiny facades of central business districts, shopping malls and luxurious gated communities.

What should also be noted is that Wang specifically chose the ten workers from a previous photoshoot. At that time, he was still working for the Beijing Youth Daily and invited them for lunch to learn about their working and living conditions.Footnote52 Notwithstanding Wang’s rejection of any engagement with this under-represented social group, the exhibition suggests something different. The apparent disengagement with and de-personification of migrants by naming the work 25,000 Bricks could perhaps constitute a strategy to sensibilise the audience and acknowledge this socio-spatial problem whilst navigating China’s authoritarian and censored regime. Aligning with the dominant narrative of erasure and exploitation associated with the floating population, it could be argued that artists re-produce this narrative to perhaps safeguard their status.

For instance, the case of Liu Bolin as a migrant artist who moved to Beijing in 2005 can give an insight into this issue. Initially, his photographic project Hiding in the City aimed to critically present his personal experience as a migrant and respond to the demolition of Suojia Artists’ Village in Beijing. He would carefully paint his face, body and clothes to camouflage himself amongst the ruins. His figure would disappear against a variety of backgrounds, from ruins to walls, and again from billboards to street signs.Footnote53 Whereas Liu’s project stemmed from the desire to problematise the unjust social discrimination against migrant workers in Chinese metropolises, today, his project has turned into remunerative and commercial collaborations with luxury fashion brands and perhaps lost its initial social relevance.

The trope of erasure and indirect engagement can be highly problematic. As spacious, cheap studios can only be found in the city outskirts and peripheries, artists ‘move to the only areas that migrant workers can afford’.Footnote54 Living in the same suburbs, they have privileged access to the floating population’s life conditions. However, artists often decide not to overtly denounce the increasing social and spatial inequalities. Liu Bolin’s case shows that as he entered the art market and international scene, his social status as rural migrant became forgotten. Whilst this instance cannot be generalised, it aligns with Xiang Wang’s findings in Guangdong on the arbitrariness of the migration regulations and hukou system, which often allow exceptions according to the status and fame of individuals.Footnote55 Going back to the symbolic erasure of migrant workers, Wang Wei's exhibition mirrors the (non-)existence of this social class by concealing them in the gallery and refuses overtly to criticise the top-down policies. Whether deliberately or not, Wang’s artistic exercise, capturing the illegality, elusion and transience of the floating population, seems to reinstate the way in which this social group has been widely and unfairly represented by officials, media, and urban dwellers.

Semi-hidden

Rather than accepting their denigrated and excluded condition, migrants have demonstrated their resilience by residing in the city and shaping a better life for themselves. Even though they often have no other alternatives, villagers move to urban areas because they aspire to improve their own condition.Footnote56 Indeed, despite mostly securing low-skilled, unstable and badly paid jobs due to poor education and rural origins, these informal occupations still prove to be more profitable and, hence, more attractive than agriculture.Footnote57 Furthermore, migrants’ presence in the city is often reliant on their ability to create a web of relations – friends or villagers already there who can introduce them into their inner circle. During the Covid-19 lockdowns they demonstrated their key role by providing indispensable services to the city, such as the numerous delivery drivers who camped on the streets to deliver food and make a living in these unprecedented times.Footnote58 Overall, I advance that migrants are resourceful, crucial to the functioning of the city, and even creative in their everyday solutions, as exemplified by the rural villagers who converted their residential lands into multi-storey buildings to be rented.

Moreover, I posit that the creative, innovative, and invaluable dimension of migrants can be found in their sites, namely the rural–urban fringes and villages in the city (VICs). They both are hybrid places, physically or metaphorically, in between the city and the countryside. The former refers to the edges of the city and those villages in the countryside that have been encroached on by the expanding urbanities. The latter, VICs, are informally built villages within the city centre. Often overshadowed by the glossy high-rises and the modern central business district, they provide constant stimuli, thanks to their ever-changing features and continuous spatial renegotiations between the city and periphery. These VICs provide migrants, students, white- and blue-collar workers with housing, services and easy access to the city and their workplace. They emerge spontaneously, and incessantly re-adjust to the changing layout of the city. The tension augmented by differences, and the multiplicity of places, rather than being worthy of contempt, adds to the functioning of the city. On the one hand, the liminalities of the rural and urban areas can be thought of as two grinding surfaces, whose friction releases heat and produces sparkles of energy and potentiality; on the other, the same in-betweenness opens up possibilities and initiates dialogues through a fluid exchange. Whereas Svetlana Boym asserts that cities (as a whole) are porous beings, I suggest that their capacity to absorb, release and mutate is particularly evident in these fluid and ephemeral zones.Footnote59 Overall, rural–urban fringes and VICs not only show the resourcefulness of rural migrants and villagers, but also provide invaluable services and diversity to the city, making them inseparable.

The increasing awareness towards the potentiality inherent within the top-down concealment of the floating population is mirrored by Hu Weiyi’s The Window Blind (2019). Born in Shanghai in 1990, Hu graduated in Public Art from the China Academy of Art in Shanghai and pursued an MA in media. Hu’s multimedia works are concerned with social and spatial inequality by physically displaying the disappearance of individuals and local activities. Hu had always lived in the city centre of Shanghai until moving to Songjiang, a district in the southwest of Shanghai. Despite being over an hour from the city centre, many artists rent their studios there as they can afford bigger and cheaper spaces. Known as the ‘root of Shanghai’, Songjiang was a commercial town located in Jiangsu province.Footnote60 It was only in 1958 that it was re-designated as part of Shanghai municipality. Since then, it has experienced rapid industrial and urban development and become a village in the urban fringes of Shanghai. Contrary to the urban core, where transformations are slower and harder to notice, this peripheral neighbourhood is considered by many artists as an eclectic and kaleidoscopic space that provides a multisensorial experience. Fascinated by the lights, smells, sounds and the intrinsic energy of Songjiang, Hu describes it as ‘a kind of place in between the city and the countryside’, where you can quickly spot the changes and encounter ‘strange landscapes’.Footnote61

Though Hu’s exhibition The Window Blind does not include any direct references to the floating population, he states that his work departs from quotidian scenes in Songjiang to investigate the erasure of migrants and the power-relations staged in the liminal areas between city and countryside. Specifically, in his video installation, No Traces (2019), Hu depicts the so-called ‘handshake’ buildings, which are high-rise structures so close to each other that they can metaphorically kiss or shake hands. They are bottom-up solutions to official urban policies. They mirror the creativity and inventiveness of those rural workers who had to find an alternative income to agriculture and illegally added floors to their compounds to rent them out.Footnote62 However, more often than not, they are treated by the central government as untidy, unhygienic, and unsafe accommodation that needs to be renewed or demolished. In Hu’s video, the windows of these densely populated habitations are either portrayed as empty and dark hollows or with hanging clothes overlooking the apartment. As the sliding bar moves from one end to the other, the windows liven up or shut down, cleaning the building again and again.Footnote63

Hu Weiyi, No Traces, 2019, video installation, 95 × 170 × 20 cm 1 + 1AP, photograph: courtesy of the artist

Hu’s work also alludes to the governments’ cleansing campaigns, which have been implemented since the 1990s. As mentioned at the beginning of this article, cleansing campaigns are instrumental in concealing the existence of the rural population and deterring illegality, which, in turn, can be indicative of inefficient government control. However, as Hu’s video displays, it is not only the untidy and displeasing that is concealed or removed, but the overall liveliness and diversity of migrants and their spaces. The demolition of villages and neighbourhoods alters the overall urban dynamics, flattening the urban fabric and wiping out the heterogeneity, fluidity and potentiality provided by these migrating population and territories. From inhabited and bustling flats, Hu’s sliding bar empties and turns them into ghost buildings. Apart from the bar and brush, Hu also uses another object to convey erasure, a semi-transparent curtain. The filtered image becomes granular, losing definition and clarity. By deploying the brush and curtain to cleanse buildings, Hu brings attention to the central government’s attempts to conceal the existence of an irregular floating population as a preventive strategy to safeguard the party’s goal for a harmonious society.

The curtain calls for a reference to Václav Havel’s veil, which supposedly embodies the pervasiveness of ideology. Investigating post-totalitarian regimes in Eastern Europe, Havel argues that ideology connects the regime to the people by offering them an easy escape from reality, an illusion.Footnote64 Whereas Havel conceives of ideology as an imaginary construction of reality, neo-Marxists, such as Althusser, Jameson and, later, Žižek, argue that ‘ideology has nothing to do with “illusion”, with a mistaken, distorted representation of its social content’.Footnote65 They argue that what we experience as real is deeply ideological, to the point that it becomes impossible to disentangle ideology from reality. Applied to the context of China, the China Dream and the principle of ‘harmonious society’ pervade reality. As the presence of migrants showcases an unfair and unequal society, it can also allude to the faults of the PRC. Although Žižek argues that in democratic and late-capitalist societies, the significance of confrontation has lost its power, I argue that in a non-democratic and transitioning country such as China, there is still a residual fear of losing legitimacy.

Indeed, ideology is characterised by an intrinsic tension that ‘designates totality set on effacing the traces of its own impossibility’.Footnote66 Although the China Dream, can be thought of as the connective tissue between individuals and reality, it is fragile and precarious. Due to this internal instability the regime condemns even the mildest attempts to resist ideology, including students’ demonstrations, workers’ strikes and petitioning, as well as the illegal construction of buildings and settlements by rural villagers and migrants. Although these are not active attempts to fight against ideology, they are localised points of friction with the authorities that are deemed to be expressions of dissent.Footnote67 In Hu’s series The Windows Blind, the white, semi-transparent curtain seems to refer to the politics of erasure enacted by the central government to advance a certain ideology. By cleansing the urban scene, the veil brings forth the vision of a tidy and organised city as imagined by real-estate planners and local authorities.

However, the veil can metaphorically point to another kind of erasure: on the one hand, there is the above-mentioned detractive erasure spread across urbanites; on the other, there is an erasure that is conducive to possibilities. This latter – what I refer to as ‘hidden potential’ – is activated by migrants themselves, who make the most of their unfavourable conditions and want to resist their unseen-ness. Confined to the hidden sphere, the floating population attempts to take advantage of their erasure. Havel argues that the ‘hidden sphere’ is where an initial potential for transformation can emerge within individual’s conscience.Footnote68 It is only through this hidden sphere that one can aspire to mature awareness and perhaps advance a political or social critique. Today, in China, this hidden and transformative potential has materialised along the streets, where several illegal ads and tags appear on the walls and are promptly painted over by local authorities. Bearing in mind Rancière’s distribution of the sensible, Parke suggests that these marks provide tangible instances of the spatial struggle between visible/hidden, and official/non-official. Footnote69 Their apparition and erasure, as performed respectively by the grassroots and the local authorities, can be interpreted as the visualisation of the continuous renegotiation of space and power.

Recently, the desire to be seen and heard has translated into several bottom-up interventions, such as the protests of nail houses, and the negotiation of residents’ compensation and urban renewal.Footnote70 Beijing-based artist Jiang Zhi reflects on this latter episode in his five-minute video work Black Sentence (2010). Jiang was born in 1971 in Yuanjiang, Hunan, and studied and graduated in 1995 at the China Academy of Art in Hangzhou. Between 1998 and 2005, Jiang worked as a photo reporter in Shenzhen and started investigating the urban and economic development in Chinese cities through photographs.Footnote71 Jiang’s video Black Sentence demonstrates his urban and social concerns at a time of incessant and rapid transformations. This video work engages with an exceptional case of eviction, when three family members climbed onto their house roof and set themselves on fire, with one elderly family member dying from his wounds a few days later. The forced relocation episode reached the national news due to the severity of the incident and the upsetting images circulated on the web.

Jiang’s video is a response to the photographs of the man’s burns and portrays an unperturbed and featureless face being swollen by red, purple and yellow flames. The video proceeds slowly and inexorably. The viewpoint is central and directly focused on the face, not letting anything else enter the scene. Whereas the audible crackle and visual intensity of the flames evoke the despair of the evicted man, the black ashes and fumes at the end of the short film seem to metaphorically refer to his stillness and silence. The video culminates in the dark, bringing the man back to oblivion. This extreme and violent act was a request for visibility in a world where this man could not get noticed. Sun argues that ‘gestures toward suicide are, to borrow Spivak’s words (albeit in a very different context), a “message inscribed in the body when no other means will get through”’.Footnote72 Instilled by necessity, migrants’ intervention is different from visual artists’ in that it is intrinsically precarious; ‘its effectiveness is often contingent, its outcome unpredictable, and its impact on workers extremely uncertain’.Footnote73

In the artistic practices analysed, erasure, instead of denying presence, amplifies the absence and lets potentialities emerge. Black Sentence demonstrates one tragic outcome of this invisibility, which reached the national news and encouraged an international artist like Jiang Zhi to record this ephemeral moment. Likewise, in Hu’s video installations No Traces, the process of cleaning up and erasing certain places and (symbolically) migrants is rendered particularly evident. Not only does it show the abruptness of the erasure, but it also hints at the liveliness and resourcefulness of these excluded people. In these instances, the tools of concealment and liminality take on a different connotation. Erasure turns into a means by which to shed light on migrants’ biased reputation and urgency to be seen. As I will demonstrate in the next section, erasure becomes the initiator for processes of multiplicity, simultaneity and hybridity.

Visible Engagements

Although the exclusion of migrants from space-making and society is still predominant, in the last fifteen years, there have been increasing urban and creative demonstrations of the existence of the floating population. Alongside the already mentioned urban tags on public surfaces, Liu et al report the informal attempts to offer free education to migrant children in Shenzhen.Footnote74 Moreover, until May 2023 there were two museums entirely dedicated to migrant workers: the state-owned Migrant Labour Museum in Shenzhen, which romanticises the figure of the rural worker and weaves a ‘linear and optimistic narrative’ to reassure NGOs and activists; and a grassroots-run museum just outside Beijing, in Picun village, the Migrant Workers’ Culture and Arts Museum.Footnote75 Established in 2008, the space in Picun emerged thanks to the New Workers’ Art Troupe (NWAT), in dialogue with Chaoyang Cultural District Bureau and the village committee.Footnote76

Conducting a comparative analysis of the two above-mentioned museums, Qian and Florence posit that the mission of the Migrant Workers’ Culture and Arts Museum in Picun was to offer ‘a platform for voice-making and improving the recognition of rural migrant workers by the state and society at large’.Footnote77 In the words of one founder of the museum: ‘workers who had contributed so much to building and advancing society were unable to make our voices heard and our culture visible’.Footnote78 Hence, the permanent collection, comprising five exhibitions halls, wanted to demonstrate ‘the workers’ efforts and sacrifices which have not been rewarded by the Chinese society’.Footnote79 Specifically, the museum provided an array of textual and visual materials, including governmental policies, ‘official and self-produced surveys’, as well as the number of injuries at work in a year.Footnote80 Additionally, the personal stories of migrant workers in the form of letters, documents, poems, photographs and drawings featured highly in the exhibition space as case studies to show instances of individual endurance and hardships whilst fostering values like justice and communality.Footnote81

Alongside the collection, the museum also organised workshops and collaborated with researchers, for instance in the project ‘The New Workers Dictionary’.Footnote82 Furthermore, the NWAT ran a series of cultural activities in Picun, such as the New Workers’ Art Festival, the Precarious Workers’ Spring Festival Gala, the free screening of films at the weekend, and the Tongxin experimental school for migrant children.Footnote83 Contrary to the official narrative, Picun museum encouraged a sense of community by giving space to the individual stories of this under-represented group and recognising the interlinked role of migrants within society. Unfortunately, Picun museum was forced to close in May 2023 and will soon be demolished due to top-down redevelopment plans.Footnote84

Despite the increasing number of projects aimed at developing a deeper engagement with the local communities and those migrants residing in rural-urban fringes and VICs, many institutions have faced a similar fate to the museum in Picun. For instance, the art space Handshake 302 in Baishizhou village, Shenzhen, opened in 2013 to empower local residents and re-imagine their urban space but shut down in 2019 due to local government’s plans for the neighbourhood.Footnote85 Strategically situated in one of Shenzhen’s VICs, where many migrant workers reside, the space invited the local community to conceive of the city as a work-in-progress they are part of.Footnote86 Although Baishizhou was certainly one of China’s VICs, it was no longer inhabited by line-factory workers and poor migrants; on the contrary, Baishizhou local residents were established working-class families that had enough capital to invest in their children’s education and join Handshake 302’s art programme.Footnote87 This certainly played a significant role in the successful interactions between Handshake 302 and the residents. From walking tours to artists’ residencies, collaborations with the Shenzhen Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism/Architecture (UABB) and workshops, local families could benefit from and develop artistic and creative encounters.

Throughout the years, Handshake 302 has valued and fostered the interlinkages between locals, individuals’ imagination and the city through bodily and collective practices.Footnote88 Site-specific works, such as Dalang Graffiti Festival (2015), Evolution (2014) and Urban Fetish: Baishizhou (2013) are exemplary projects that invite the local community to re-appropriate and reshape the imagined future of Baishizhou through art. Alongside these earlier works, the education project Handshake 302’s Art Sprouts (2016–2018) brought migrant children together to find beauty in the everyday and create artistic responses to their surroundings.Footnote89 In the project Paper Crane Tea (2014), one thousand patiently folded origami cranes were installed in the art space of Handshake 302 as a backdrop for on-site conversations and exchanges among the local and artistic community. Specifically, this work allowed for a two-fold reflection: on the one hand, the labour-intensive practice of folding paper and the final result were reminiscent of the repetitive working rhythms of migrants and their cramped spaces; on the other, the metamorphosis from dull, thin paper into elegant and stronger origami was a hopeful metaphor for the collective efforts and aspirations of this social class.Footnote90 In the inclusive and hybrid space of Handshake 302, the engagement with Baishizhou inhabitants allowed for alternative imaginaries that can perhaps inform future urban practices. Since its closure in August 2019, the space has maintained its online presence and has continued to organise educational events, workshops and walking tours of the city.Footnote91

Another collaborative project worth mentioning for its ongoing impact on the everyday reality of migrants working in factories and assembly lines is the Social Sensibility Research & Development Program (SSR&D). Initiated by Beijing-based artist Alessandro Rolandi in 2011, the Social Sensibility is a department within the French company Bernard Controls in Beijing.Footnote92 It has developed through collaboration between the factory CEO, international artists and the spontaneous participation of workers to allow for solidarity, sensibility and exchanges within the working environment. Twice a week, the factory staff can decide to dedicate some of their paid time to engage with the invited artists. The reactions have been diverse: some find the artistic interventions disrupting and prefer not to engage; some do not seem to mind the presence of the artist and often accept the interactions; last, there are those workers who are very enthusiastic and pro-active.Footnote93 This is the case with Li Zhan, an assembly line worker who developed the work I Like Round Things (2016). Collating personal objects from her private life together with tools from the factory, such as bolts, screws and other components, she created a vibrant installation that was exhibited at the Arrow Factory, Beijing. Colourful yarns and threads fell from the ceiling to the floor, where clay balls, cardboard tubes, sectioned vegetables and fruits were casually arranged. From an intimate reflection on Li’s private and working life, her work left the factory to be showcased in the spaces of the Arrow Factory and the Guangzhou Times Museum.

Although the intent of SSR&D could be misinterpreted as a top-down strategy to alleviate the workers’ strenuous life conditions through artistic engagement, it seems to be genuinely driven by a social mission. SSR&D is an eleven-year-old project that was initiated through a fortuitous conversation between Rolandi and CEO Guillaume Bernard, who shared similar views on art.Footnote94 Rolandi argues that before even trying to imagine and change migrants’ everyday life, SSR&D aims to make the workers more aware of their space and social interactions by altering power relations that are embedded within the work environment and normally expressed through reverence, gratitude and intimidation.Footnote95 Departing from the notion of art-object and the idea of authorship, SSR&D values the spontaneous exchanges within the factory, which are aimed at breaking established hierarchies, introducing creative thinking, and allowing the participants to deal with art.

With regard to artist’s residencies, the artist is invited to live in the factory and interact with the workers only if both are willing to do so. According to Rolandi, it is in the relations and conversations among factory workers and artists that art and sensibility lie. By preferring the qualitative process of art to its final product, SSR&D believes that art can affect people’s sensibility, which is the ultimate ‘capacity to respond in an organic way to external situations’.Footnote96 Art becomes a skill that allows workers to be better equipped for life. Despite the occasional challenges and confrontation from above that SSR&D has to face, Rolandi recognises that there have been several positive outcomes, such as workers leaving the factory to develop their own life projects.

The discussion of the previous artistic practices reveals the constant tension that characterises the relationship between urban and rural residents. Even though the floating population has often been treated as displeasing and concealed, it is extremely relevant to the urban ecosystem and can provide alternative solutions to the socio-spatial inequalities inherent within Chinese cities. On the one hand, migrants have spontaneously formed VICs, developed webs of relations and set up 24/7 services for those temporarily residing in urban areas; on the other, they have provided urban and social planners with diverse, flexible and informal solutions to overcome the lack of housing and services, the shortage of labour and the need to fulfil unwanted jobs, among others. Alongside greatly contributing to the urban and economic development of the last forty years, migrants have offered informal economies and cultural enterprises that are crucial for the city’s functioning.

In terms of artistic representations, this article has presented an array of practices that tackle or ignore, at times, this social concern. Artists, as part of the urban fabric, and personally bound to these peripheral areas and their populations, have certainly had a privileged insight into these issues. However, they have often fed into the official discourse of erasure. This is the case of Wang Wei, who almost touches upon the seclusion and obliteration of migrant workers but avoids openly denouncing the social and spatial inequalities. This choice is certainly interlinked with China’s authoritarian regime and the use of censorship by the central government. Artists’ disengagement with sensitive concerns allows them to maintain their status and move away from what could be interpreted as oppositional. Moreover, the tactic of adopting the state rhetoric has long been internalised and proved successful in mobilising bottom-up protests.Footnote97 By deploying the same official strategies, artists have more leeway to advance alternative narratives and foster the audience’s own interpretation, whilst safeguarding themselves.

The trope of erasure has therefore been shown to be powerful and widely adopted to represent the floating population. It can be useful to articulate the complex dynamics and tensions between different groups – migrants, artists and more powerful urban actors. Moreover, it has been deployed in different ways: from reiterating the invisibility of migrant workers to a strategy of talking about the proliferation of illegal businesses, informal transactions and services offered to the excluded. Additionally, erasure has also become the catalyst for many art spaces, such as the museum in Picun or Handshake 302 and SSR&D. In these latter cases, the erasure and unfairness associated with migrant workers still constitute the underlying motivation. These socially engaged practices that call for the participation of under-represented groups have emerged to let ‘the subaltern speak’ and make a more concrete difference.Footnote98 In this article, Handshake 302, SSR&D and the migrants’ museum in Picun village are presented as successful attempts to reposition villagers and their community as conscious holders of artistic and transformative agency, capable of advancing their visions and dreams. As wider exchanges across different social strata are essential to address problems and reconfigure more sustainable and inclusive realities, more artistic and socially engaged collaborations should emerge and inspire future discussion.

I wish to thank my doctoral supervisors Prof Jiehong Jiang and Dr Theo Reeves-Evison for their insights and Dr Lauren Walden for being an invaluable mentor. Moreover, I am thankful to the artists mentioned in this paper who kindly agreed to meet to discuss their works and use their images. This work was supported by Midlands3Cities (AHRC) funding under the AHRC Doctoral Studentship Award. This article has stemmed from my doctoral thesis, ‘Urban Imaginaries: Contemporary Art and Urban Transformations in Mainland China since 2001’, Birmingham School of Art, Birmingham City University, 2022.

Notes

1 From now on, I will refer to Mainland China as China.

2 While other countries in Southeast Asia have experienced tremendous urban changes, according to Thomas Campanella and Wu Fulong, the case of China is especially worth examining. For instance, Campanella identifies six characteristics of the PRC which make the Chinese case extraordinary as they are all occurring simultaneously: speed, scale, spectacle, sprawl, segregation and sustainability. See Thomas J Campanella, The Concrete Dragon: China’s Urban Revolution and What It Means for the World, Princeton Architectural Press, New York, 2008, p 281. Moreover, Wu Fulong recognises the stark presence of the state in mediating globalisation as a unique feature of the PRC. See Fulong Wu, China’s Emerging Cities, Routledge, Abingdon, 2007, p 6.

3 See Wu, China’s Emerging Cities, op cit; Campanella, The Concrete Dragon, op cit; Maurizio Marinelli, ‘Urban Revolution and Chinese Contemporary Art in a Total Revolution of the Senses’, China Information, vol 29, no 2, 2015, pp 154–175

4 Kim Wing Chan, ‘The Household Registration System and Migrant Labour in China: Notes on a Debate’, Population and Development Review, vol 36, no 2, 2010, pp 357–364; Him Chung, ‘The Spatial Dimension of Negotiated Power Relations and Social Justice in the Redevelopment of Villages-in-the-City in China’, Environment and Planning A 45, 2013, pp 2459–2476; Cindy C Fan, China on the Move: Migration, the State, and the Household, Routledge, Abingdon, 2008; Arianne Gaetano, ‘Rural Woman and Modernity in Globalizing China: Seeing Jia Zhangke’s The World’, Visual Anthropology Review, vol 25, no 1, 2009, pp 25–39

5 See Chaolin Gu and Jianafa Shen, ‘Transformation of Urban Socio-Spatial Structure in Socialist Market Economies: The Case of Beijing’, Habitat International, vol 27, no 1, 2003, pp 107–122

6 Kim Wing Chan and Will Buckingham, ‘Is China Abolishing the Hukou System?’, The China Quarterly 195, 2008, pp 582–583

7 Xinguang Chen, Bonita Stanton, Linda Kaljee, Xiaoyi Fang, Qing Xiong, Danhua Lin, Liying Zhang, and Xiaoming Li, ‘Social Stigma, Social Capital Reconstruction and Rural Migrants in Urban China: A Population Health Perspective’, Human Organization, vol 70, no1, 2011, p 28

8 Ibid

9 Wanning Sun, Subaltern China: Rural Migrants, Media, and Cultural Practices, Rowman & Littlefield, London, 2014, pp 59, 63

10 Chun Wing Tse, ‘Urban Residents’ Prejudice and Integration of Rural Migrants into Urban China’, Journal of Contemporary China, vol 25, no 100, 2016, pp 579–595

11 Hechao Jiang, Taixiang Duan, and Mengyi Tang, ‘Internal Migration and the Negative Attitudes toward Migrant Workers in China’, International Journal of Intercultural Relations 92, 2023, p 2

12 Tim Cresswell, On the Move: Mobility in the Modern Western World, Routledge, New York and Oxford, 2006, p 26; see also Pete Merriman, Mobility, Space and Culture, Routledge, New York and Oxford, 2012

13 Hui Li, Kunqiu Chen, Lei Yan, Ling Yu and Yulin Zhu, ‘Citizenization of Rural Migrants in China’s New Urbanization: The Roles of Hukou System Reform and Rural Land Marketization’, Cities 132, 2023, p 1

14 Alan Smart and Wing-Shing Tang, ‘Irregular Trajectories: Illegal Building in Mainland China and Hong Kong’, in Laurence Ma and Fulong Wu, eds, Restructuring the Chinese City: Changing Society, Economy and Space, Routledge, New York, 2005, p 73

15 Ibid

16 Bruno de Meulder, Yanliu Lin and Kelly Shannon, eds, Village in the City: Asian Variations of Urbanisms of Inclusion, Park Books, Zurich, 2014, p 43

17 William Callahan, ‘The China Dream and the American Dream’, Economic and Political Studies, vol 2, no 1, 2014, p 156. The China Dream calls for the ‘rejuvenation of the nation’ through the so-called socialism with Chinese characteristics. Xi envisioned socialism with Chinese characteristics as ‘a continuation and development of Marxism-Leninism, Mao Zedong Thought, Deng Xiaoping Theory, the Theory of Three Represents, and the Scientific Outlook on Development’. See ‘Full Text of Resolution on Amendment to CPC Constitution’. Xinhua. 2017, http://www.xinhuanet.com//english/2017-10/24/c_136702726.html.

18 Boris Groys, Art Power, MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, 2008, pp 6–7

19 Federica Mirra, ‘Urban Imaginaries: Contemporary Art and Urban Transformations in Mainland China since 2001’, doctoral thesis, Birmingham School of Art, Birmingham City University, 2022, p 268

20 Elizabeth Parke reflects on these illegal tags (banzheng) in ‘Out of Service: Migrant Workers and Public Space in Beijing’, in Minna Valjakka and Meiqin Wang, eds, Visual Art, Representations and Interventions in Contemporary China: Urbanized Interface, Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 2018, pp 261–284

21 Jacques Rancière, The Politics of Aesthetics: The Distribution of the Sensible, Continuum International Publishing Group, London and New York, 2011, pp 12–13

22 Rancière, The Politics of Aesthetics, op cit, p 13

23 Yanliu Lin, Bruno de Meulder, and Shifu Wang, ‘Understanding the ‘Village in the City’, in Guangzhou: Economic Integration and Development Issue and their Implications for the Urban Migrant, Urban Studies, vol 48, no 16, 2011, pp 3583–3598, p 3587

24 Ibid, pp 3587−3588

25 Wing-Shing Tang and Him Chung, ‘Rural–Urban Transition in China: Illegal Land Use and Construction’, Asia Pacific Viewpoint 43, 2002, p 49

26 Chung, ‘The Spatial Dimension of Negotiated Power Relations’, p 2463

27 Jie Fan and Wolfgang Taubmann, ‘Migrant Enclaves in Large Chinese Cities’, in John R Logan, ed, The New Chinese City: Globalization and Market Reform, Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, 2001, pp 183–197

28 Fan, China on the Move, op cit; Fan and Taubmann, ‘Migrant Enclaves in Large Chinese Cities’, op cit; Gaetano, ‘Rural Woman and Modernity in Globalizing China, op cit; Zheng Tiantian, ‘Complexity of Life and Resistance: Informal Networks of Rural Migrant Karaoke Bar Hostesses in Urban Chinese Sex Industry’, China: An International Journal, vol 6, no 1, 2008, pp 69–96. Since Covid-19, the gender gap has also increased as many women migrants returned home and were less likely to come back to the city. See Yueping Song, Hantao Wu, Xiao-yuan Dong and Zhili Wang, ‘To Return or Stay? The Gendered Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Migrant Workers in China’, Feminist Economics 27, nos 1–2, 2021, pp 236–253.

29 Margaret Crawford and Jiong Wu, ‘The Beginning of the End: Planning the Destruction of Guangzhou’s Villages’, in Stefan Al, ed, Villages in the City, Hong Kong University Press and University of Hawaii Press, Hong Kong, 2014, pp 19–20

30 Gu and Shen, ‘Transformation of Urban Socio-Spatial Structure, op cit, pp 107–122

31 Ma and Wu refer to this practice as the policy of ‘abolishing counties and establishing cities’, see Laurence J C Ma and Fulong Wu, eds, Restructuring the Chinese City: Changing Society, Economy and Space, Routledge, New York, 2005, p 27. As mentioned above, villagers also started constructing illegal buildings on their land to find an alternative income to agriculture.

32 Stefan Al, ed, Villages in the City: A Guide to South China’s Informal Settlements, Hong Kong University Press and University of Hawaii Press, Hong Kong and Honolulu, 2014; Yani Lai and Xiaoling Zhang, ‘Redevelopment of Industrial Sites in the Chinese “Villages in the City”: An Empirical Study of Shenzhen’, Journal of Cleaner Production 134, 2016, pp 70–77; Smart and Tang, ‘Irregular Trajectories’, op cit

33 Chan, ‘The Household Registration System’, op cit, pp 357–358; Lin, de Meulder and Wang, ‘Understanding the “Village in the City”, op cit, p 3586

34 Ma and Wu, Restructuring the Chinese City, op cit, p 28. The baojia system was abandoned with the establishment of the People’s Republic of China and the introduction of the hukou.

35 Chan, ‘The Household Registration System, op cit

36 Lin, de Meulder, and Wang, ‘Understanding the “Village in the City”’, op cit, p 3586

37 Mary Ann O’Donnell and Jonathan Bach, ‘Reclaiming the New, Remaking the Local: Shenzhen at 40’, China Perspectives 2, 2021, p 74

38 Ibid

39 Guowuyuan (State Department, 国务院), Guowuyuan guanyu jin yi bu tuijin huji zhidu gaige de yijian (The view of the State Department on bringing the reforming of the household registration system a step further, 国务院关于进一步推进户籍制度改革的意见), zhonghua renmin gongheguo zhongyang renmin zhengfu (The People Republic of China's Government, 中华人民共和国中央人民政府), 30 July 2014, https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2014-07/30/content_8944.html. Moreover, Xiang Wang investigated the impact of the top-down reforms in Guangdong province, see Xiang Wang, ‘Permits, Points, and Permanent Household Registration: Recalibrating Hukou Policy under “Top-Level Design”’, Journal of Current Chinese Affairs, vol 49, no 3, 2020

40 Li et al, ‘Citizenization’, op cit

41 Sun, Subaltern China, op cit, p 12. For instance, in the aftermath of Covid-19, not only have rural migrants been some of the worst hit by the lockdowns but they have also faced job discrimination as they look for employment. See Lei Che, Haifeng Du and Kam Wing Chan, ‘Unequal Pain: A Sketch of the Impact of the Covid-19 Pandemic on Migrants’ Employment in China, Eurasian Geography and Economics, vol 61, nos 4–5, 2020, pp 448–463; ‘Migrant workers still at great risk despite key role in global economy’, UN News: Global Perspective Human Stories, 16 December 2021, https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/12/1108082, accessed 6 November 2023; Nathan Chung, ‘“We won’t survive”: China’s Migrant Workers Fear More Lockdowns as Covid Threat Remains’, The Guardian, 16 June 2022.

42 Yani Lai and Xiaoling Zhang, ‘Redevelopment of industrial sites’, op cit

43 Shizhengfu bangongting (The Municipal Government’s Office,市政府办公厅), ‘Guanyu Jiakuai Tuijin ‘San Jiu’ Gaizao Gongzuo de Yijian (Opinions on Accelerating the Pace of Redevelopment of the Three Olds, 关于加快推进’三九’改造工作的意见)’, Guangzhoushi renmin zhengfu (The People’s Government of Guangzhou Municipality, 广州市人民政府), 2010, http://www.gz.gov.cn/zwgk/fggw/szfwj/content/post_2833198.html

44 Sun, Subaltern China, op cit, p 12

45 Wang, ‘Permits, Points’, op cit, p 284

46 Mirra, Urban Imaginaries, op cit, p 78. For more texts on Wang Wei, see Wu Hung, Exhibiting Experimental Art in China, The David and Alfred Smart Museum of Art, The University of Chicago, Chicago, 2000; Sophie McIntyre and Zhaohui Zhang, Concrete Horizons: Contemporary Art from China, Adam Art Gallery, 2004; Federica Mirra, ‘The Art of Billboards in Urbanized China’, Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art, vol 7, nos 2–3, 2020, p 295.

47 Author’s in-person interview with Wang Wei at the artist’s studio, Beijing, 30 April 2019

48 Karen Smith, ‘Artist’s Introduction by Karen Smith’, Arrow Factory, accessed 18 February 2020, http://www.arrowfactory.org.cn/wangwei/articles/KarenSmith.htm

49 Philip Tinari, ‘What Does Not Stand Cannot Fall: Wang Wei’s Temporary Space’, Arrow Factory, accessed 18 February 2020, http://www.arrowfactory.org.cn/wangwei/fei-er.htm

50 Philip Tinari, ‘Wang Wei’s Temporary Space’, in Meiling Cheng and Gabrielle H Cody, eds, Reading Contemporary Performance: Theatricality Across Genres, Routledge, London and New York, 2016

51 Author’s in-person interview with Wang Wei at the artist’s studio, Beijing, 30 April 2019

52 Tinari, ‘Wang Wei’s Temporary Space’, op cit

53 Meiqin Wang, Urbanization and Contemporary Chinese Art, Routledge, New York and Abingdon, 2015, Chapter 5, ‘Disappearing Bodies’, pp 161–206

54 Federica Mirra, ‘Artistic and Spatial Mobility in China’s Urban Villages’, Patricia Garcia and Anna-Leena Toivanen, eds, Urban Mobilities in Literature and Art Activism, Springer Nature, Cham (in press)

55 Wang, ‘Permits, Points’, op cit

56 Mirra, ‘Artistic and Spatial Mobility’, op cit

57 Fan, China on the Move, op cit

58 Xin Li, ‘Fearing Lockdown, Beijing’s Delivery Workers Camp Outside’, Sixth Tone, 23 November 2023, https://www.sixthtone.com/news/1011728; Vivian Wang, ‘In a City under Lockdown, Hope Arrives by Motorbike’, The New York Times, 2020

59 Svetlana Boym, The Future of Nostalgia, New Books, New York, 2001, p 77

60 Author’s in-person interview with Jin Feng and Bi Rongrong, artist’s studio, Shanghai, 17 May 2019

61 Author’s in-person interview with Hu Weiyi, HdM Gallery, Beijing, 6 May 2019

62 Al, Villages in the City, op cit, p 1

63 In-person interview with Hu Weiyi, HdM Gallery, Beijing, 6 May 2019

64 Václav Havel, ‘The Power of the Powerless’, International Journal of Politics, vol 15, nos 3–4, 1985, pp 23–96

65 Slavoj Žižek, Mapping Ideology, Verso, London, 2012, p 4

66 Žižek, op cit, p 49

67 In ‘The Power of the Powerless’, Havel makes a useful distinction between the terms, ‘opposition’ and ‘dissent’. Whereas the former originated in the West to describe a legitimate alternative to the current government in Western democracies, dissent was deployed by Western journalists to refer to the opposition specific to post-totalitarian regimes. Dissent is the systematic expression of unconventional and critical opinions in public, whose intention has a strong political dimension. Havel suggests that those who are called dissidents do not consider themselves as such and do not decide to become dissidents.

68 Ibid

69 Parke, ‘Out of Service’, op cit, p 262

70 Matthew Erie reported several instances of nail house protests in China, including the successful negotiation by Wu Ping in Chongqing in 2007 and the distressing case of three family members burning themselves on their evicted house roof as an act of protest in 2010 near Fuzhou city. See Matthew S Erie, ‘Property Rights, Legal Consciousness and the New Media in China: The Hard Case of the “Toughest Nail-House in History”’, China Information, vol 26, no 1, 2012, pp 35–59.

71 In the last ten years, Jiang Zhi has been more concerned with light and the exploration of reality. Several monographs and catalogues have been dedicated to his work and career, including Leo Li Chen and Zhi Jiang, Jiang Zhi, Blindspot Gallery, Hong Kong, 2018; Agnes Lin, Jiang Zhi: On the White, Osage Kwun Tong, Hong Kong, 2008; Pauline J Yao, Jiang Zhi: Shine Upon Me, DF2 Gallery, Los Angeles, 2008; na, Sucker: Works of Jiang Zhi, Da Dao Publishing House, Hong Kong, 2003, as well as mentions by Jiehong Jiang in: An Era Without Memories, Thames & Hudson, London, 2015, and The World of Art: The Art of Contemporary China, Thames & Hudson, London, 2021, p 137–138.

72 Sun, Subaltern China, op cit, p 71

73 Ibid

74 Liu et al, ‘Towards Inclusive and Sustainable Transformation’, op cit

75 Junxi Qian and Eric Florence, ‘Migrant Worker Museums in China: Public Cultures of Migrant Labour in State and Grassroots Initiatives’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, vol 47, issue 12, 2020, pp 2706–2704

76 Qian and Florence, ‘Migrant Worker Museums in China: Public Cultures of Migrant Labour in State and Grassroots Initiatives’, op cit

77 Ibid, p 2711

78 Jia Li, ‘Starting From Picun: About the Migrant Workers’ Culture and Art – An interview with Sun Heng (Cong picun kaishi guanyu dagong wenhua yishu bowuguan – fang Sun Heng 从皮村开始关于打工文化艺术博物馆——访孙恒.)’, Contemporary Art and Investment (Dangdai yishu yu touzi 当代艺术与投资) 6, 2011, pp 85–89, http://m.wyzxwk.com/content.php?classid=23&id=238229

79 Qian and Florence, ‘Migrant Worker Museums in China’, op cit, p 2717

80 Qian and Florence, ‘Migrant Worker Museums in China’, op cit, p 2718; Qi Shi (石奇), ‘Zaifang Picun dagong bowuguan zhiyi: bu wei wangque de jinian’ (Revisit one of the Picun Migrant Workers’ Museums: A Memorial that Is not Forgotten, 再访皮村打工博物馆之一:不为忘却的纪念,), Hong ge hui wang (Red Song Society, 红歌会网), 2023), https://www.szhgh.com/Article/gnzs/worker/2023-06-15/328599.html

81 Ibid

82 Li, ‘Starting from Picun’, op cit

83 Federico Picerni, ‘Strangers in a Familiar City: Picun Migrant-Worker Poets in the Urban Space of Beijing’, IQAS, vol 51, nos 1–2, 2020, pp 47–170; Shan He, and John Sexton, ‘Migrant Workers Tell Their Story in New Museum’, China.Org.Cn, 2008, http://www.china.org.cn/china/features/content_16728913.html

84 Maghiel van Crevel, ‘Picun Museum to be Demolished’, Modern Chinese Literature and Culture, 18 May 2023, https://u.osu.edu/mclc/2023/05/18/picun-museum-to-be-demolished

85 The project started in October 2013 thanks to Mary Ann O’Donnell, Zhang Kaiqin, Wu Dan, Liu He and Lei Sheng, Mirra, ‘Artistic and Spatial Mobility’, op cit

86 Meiqin Wang, ‘Walking the City: Handshake 302 and Reinventing Public Art in Shenzhen’, Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art, vol 7, nos 2–3, pp 177– 200

87 According to an anonymous interviewee, there is some misunderstandings around urban villages, spatially and historically. Whereas in the 1990s, VICs and urban villages could offer cheap rents and services to factory workers due to unreliable electricity and water, with the rapid urbanisation of the 2000s, villages got connected to the city and, hence, became more popular and expensive. Around the same time in 2005, the city centres were also de-industrialised and, hence, both factories and workers moved to the urban peripheries. The same anonymous interviewee argues that due to the official urban and economic agendas, VICs are getting increasingly less diverse. Author’s online interview with anonymous interviewee on Zoom, 21 August 2021.

88 For a more in-depth analysis of some of the Handshake 302 projects, see Mirra, ‘Artistic and Spatial Mobility’, op cit

89 Handshake 302 is particularly committed to art education programmes and has three main subprojects: Handshake Academy, where they work with young children, often focusing on low-impact art; Handshake on campus, where they engage with college students and teach them how to research; and Handshake 302 as the art collective interested in including the local community.

90 Mirra, ‘Artistic and Spatial Mobility’, op cit

91 The first demolitions in Baishizhou were in 2016. Handshake 302 was first requested to move in 2018, and in 2019 the space was shut down. The art space is currently exploring off-site and digital possibilities and working to offer three different online tours of Shenzhen alongside physical ones.

92 For more information on the project, see Alessandro Rolandi, ‘What Cannot Be Seen: Thoughts and Notes on Social Practice and Social Sensibility’, Academia.edu, 2016, https://www.academia.edu/28155432/What_Cannot_Be_Seen_Thoughts_and_Notes_on_Social_Practice_and_Social_Sensibility; and Alessandro Rolandi, ‘No Title’, nd, https://www.alessandrorolandi.org/.

93 Author’s online interview with Alessandro Rolandi on Zoom, 26 July 2021

94 Rolandi recounts opting for ‘social sensibility’ as it resonated better with their vision of what artistic practices can do for individuals

95 Author’s email exchange with Alessandro Rolandi, 20 August 2021

96 Alessandro Rolandi, ‘The Social Power of Art | Alessandro Rolandi | TEDxBeijing’, Youtube, 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O30nu06zjEA

97 Matthew S Erie, ‘Property Rights, Legal Consciousness and the New Media in China’, op cit; Ching Kwan Lee, ‘The “Revenge of History”: Collective Memories and Labor Protests in North-Eastern China’, Ethnography, vol 1, no 2, 2000, pp 217–237; Dingxin Zhao, The Power of Tiananmen: State–Society Relations and the 1989 Beijing Student Movement, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2001; Kevin J O’Brien and Lianjiang Li, Rightful Resistance in Rural China, Cambridge University Press, New York, 2006; Lucian W Pye, ‘Tiananmen and Chinese Political Culture: The Escalation of Confrontation from Moralizing to Revenge’, Asian Survey, vol 30, no 4, 1990, pp 331–347

98 I borrow the phrase from Spivak, who used it in colonial and postcolonial discourse. See Gayatry Chakravorty Spivak, ‘Can the Subaltern Speak?’, in Laura Chrisman and Patrick Williams, eds, Colonial Discourse and Post-colonial Theory: A Reader, Harvester Wheatsheaf, New York and Sydney, 1993, pp 66–111