Abstract

This article considers the documentary film, Taking Alcatraz (John Ferry, 2015), in the context of US-Indigenous history. The documentary form presents alternative ideas and futures beyond those dominant in the US imagination and run counter to stereotypical representations of Native Americans found in the Western genre. The 1969 Occupation of Alcatraz can be seen as part of a history of political dissent by Indigenous peoples whilst the (mediated) nature of film reinvigorate and reanimate ideas such as those employed at Alcatraz – perceived dormant since the closure of the prison, save for the eighteen months of Indigenous occupation, commencing in 1969. At the heart of this analysis is the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty which returned all unused land to Native peoples, prompting the Occupation, and how this event is offered continued context and urgency whilst opening previously closed dialogues of Indigenous history; stressing the power of the (moving) image.

Introduction

In mid-2016 to early 2017, Indigenous peoples and their allies gathered at Standing Rock to protest the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL), which was encroaching on Sioux (Lakota) land and undermining the 1851 Fort Laramie Treaty. Standing Rock marks a key moment of US–Lakota history but is hardly an isolated event, with echoes ranging from the signing of the Fort Laramie Treaties of 1851 and 1868 to the occupations of Wounded Knee in 1890 and 1973, and the Occupation of Alcatraz in 1969.Footnote1 The latter event is the central focus of the documentary Taking Alcatraz, a film examined here for the first time in critical detail, informing the contexts of the Standing Rock movement. In examining the strategies of the leadership of the Occupation of Alcatraz, it is possible to perceive new meaning within US historical and political discourse, and to consider the role of film in this context as cultural mediator of Indigenous activism in bringing this to light.

Standing Rock represents an important political and cultural intervention against US colonialism and capitalism for the preservation of Lakota land rights, and the event became the focus of documentary filmmakers. This includes Dislocation Blues (Sky Hopinka, 2017) and Awake, A Dream from Standing Rock (Myron Dewey, Josh Fox, James Spione, 2017), which, together with Taking Alcatraz, provide a critical dialogue around Indigenous activisms. Focusing on Taking Alcatraz, this article examines the documentary form with regards to Indigenous representation, and highlights how film contributes to the revitalisation of Indigenous knowledge systems. Furthermore, the focus here is on ways in which documentary film continues to animate political and cultural discourse, forming a space of critical intervention into US settler-colonial society. As Jeffrey Geiger writes: ‘documentary does not just reflect or engage with national consciousness, it helps us to imagine ideas and futures beyond its immediate framework and subject matter; it has the potential to transform the experience and comprehension of the national imaginary’.Footnote2 That is, film, in particular the Western genre, has contributed to ideas about America that reflect dominant discourse, such as the progressive narrative of the frontier. The Western genre’s dedication to projecting images of ‘Indians’ in romanticised forms or as a savage enemy of progress only echoes mythical portrayals of US history as seen in the Wild West shows that formed a precursor to the moving image. Footnote3 However, documentary has proved a powerful tool for filmmakers to disrupt dominant discursive narratives and the images that support them.

Taking Alcatraz is a documentary account of the 1969 Occupation of Alcatraz Island by the Indians of All Tribes (IAT), and illustrates the significance of pan-Tribal organisation, as well as how film can animate Indigenous history in a way that reconfigures colonial history. Arguably, low-budget activist documentaries such as Taking Alcatraz offer a means with which to disrupt settler–colonial discourse and open up previously closed dialogues of Indigenous history. In some ways these play on stereotypical Hollywood representations of Native Americans, but even more they are linked to Indigenous tradition and epistemology. Engaging with the Western genre as a point of departure as opposed to a point of critical enquiry will only naturalise the process that any filmic intervention seeks to achieve. Moving away from a Eurocentric interpretation is central to this process, by considering Indigenous epistemology and alternative meanings which filmic constructions can animate.

Linda Tuhiwai Smith (Ngãti Awa and Ngãti Porou iwi) argues that alternative knowledge systems can be used to counter colonial imaginings, adopt non-Eurocentric narratives and form a part of political and environmental praxis.Footnote4 Therefore, I will make use of the work of early twentieth-century Lakota writers Charles Eastman Ohiyesa and Luther Standing Bear, as well as more modern cultural critics such as Sioux journalist Nick Estes, in my analysis and consider how Indigenous epistemology responds to US narratives of progress, of limitless growth and the weight of European imperialism and colonialism as precursors to contemporary globalisation.

Taking Alcatraz considers the historical referent of the Fort Laramie Treaties of 1851 and 1868 and re-signifies them via filmic repetition and metonymic association. In this way, these filmic tropes in Taking Alcatraz present an opportunity to establish an intervention into colonially imposed narratives, with cultural constructions of the ‘Indian’ forming a useful starting point. However, these cultural formations are not solely derived from film, but reflect US discourse. That is, frontier mythology has continually pitted the ‘Indian’ against the US self, such as the cowboy.Footnote5 These notions, whilst finding expression in popular culture, go beyond cultural formations, seeping into the very fabric of the US nation. However, these cultural constructions have found expression within film, particularly in Hollywood, to the detriment of Native American representation. I will consider how the documentary form can offer an alternative vision of the US, and a cinematic mode that has been an important aspect of Indigenous filmmaking.Footnote6

The Fort Laramie Treaties and De-naturalising Dominant Discourse

In 1851, the Fort Laramie Treaty was signed by Sioux representatives and others, allowing passage of migrants and land concessions in exchange for government compensation for destroyed lands. This was followed by a flood of settlers and US military incursions into Sioux territories, vicious ‘Indian Wars’ against the Sioux and others, and eventually the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868. The second treaty established in perpetuity the Great Sioux Reservation, comprising lands from the Missouri River to the Big Horn Mountains, including the Black Hills, the Badlands, and all of South Dakota west of the Missouri. The Black Hills have long been deemed a theft from the Sioux, in this respect.

Politically, the Treaty of 1868 signalled the end of ‘Red Cloud’s War’, which began in 1866. This era witnessed Sioux and Cheyenne allies leading a series of sieges against the forts established on the Bozeman trail in response to gold-driven white encroachment in the Black Hills. The result of the treaty and the cessation of hostilities persuaded the government to close the road to public travel. This did not stop goldminers from traversing the Bighorn Mountains, or, indeed their deaths at the hands of the area’s Indigenous inhabitants. The legal boundaries of the Great Sioux Reservation were established as part of the signing of the treaty, which affirmed Indigenous hunting rights and signalled the military withdrawal from the Bozeman Trail forts.Footnote7

The Fort Laramie Treaties form the context of John Ferry’s film. Taking Alcatraz takes the viewer ‘back’ in time – in Ferry’s own view – forcing the viewer to consider dominant cultural and historical narratives of ‘progress’. Donna L Akers (Choctaw) makes reference to the US ‘Master Narrative’ and its function in historical discourse to present an unfettered image of the white American past that procured former Indigenous lands through purchase. Fitting into this over-arching mythology is the notion that the method of treaty making between white and Indigenous was sound and identical to international treaty protocol.Footnote8 However, this was not the case, as Akers illustrates: ‘These treaties were almost without exception procured through corrupt and dishonourable practices sanctioned by the highest levels of the US government.’Footnote9 Treaties demanded massive forfeiting of lands in exchange for rights that soon after proved to be violable. Treaty-making was a major tool of Euro-American conquest of the North American continent, and fits with the celebratory narratives of US nation building as well as the legal legitimation set down by the Doctrine of Discovery. The documents themselves were typically hastily constructed on scraps of paper.

The grainy cinematic pan of rows of white tepees which establishes the narrative context of Taking Alcatraz’s opening moments marks a connection between historical Lakota land concerns established by treaty. The tepee also forms a visual link between the Reservation era and the Occupation of Alcatraz, maintaining a continuum in Indigenous resistance.

In the film, a sole tepee can be seen against the backdrop of the Bay Area. This visual image not only disrupts the historical narrative but situates a Native American presence in contemporary America, establishing an important political and ideological permanence in US cultural discourse. Whilst the physical presence of Indigenous peoples on Alcatraz Island would be temporary, the ideology of resistance – and Indigenous social and political presence – persists in the US cultural imagination. Taking Alcatraz accentuates the effect the Occupation had on the wider perception of Native Americans and reverses the narrative of colonial occupation to one in which the Indigenous peoples were the occupier, whilst drawing attention to the plight of Native Americans in contemporary US.

However, it is important not to overstress the message of a forty-minute documentary film. Taking Alcatraz takes up the narrative, but also empowers the viewer to continue this trend in actively engaging with history. Taking Alcatraz’s title suggests not a documentary review of a fixed moment in time, but an on-going fluid interaction with the historical record. Whilst the Fort Laramie Treaty, historically, signalled a chain of events that would lead to the diminishment of Sioux lands and their economic and cultural systems, the narrative established by Taking Alcatraz disrupts this historical interpretation commonly referred to as the end of the so-called ‘Indian Wars’ by making important associations between treaty–making, Indigenous land rights, and narrative threads connecting Indigenous political and cultural resistance.Footnote10

The Historical Site as Film Trope

In 1968, several members of the Ojibwe Nation, including Dennis Banks, Clyde Bellecourt and George Mitchell, amongst others, founded the American Indian Movement (AIM) in Minneapolis. AIM opened survival schools and staged protests at abandoned military facilities, national parks and the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), sustaining the decolonial ideology that was a feature of the Red Power protests.Footnote11 Events staged by the Red Power movement in the first half of the nineteen-seventies contested both the public space and the memories attached to them. Many of the events acted as an ironic Indigenous counter-commemoration of the nation’s past. Sam Hitchmough highlights the example of protests held at Mount Rushmore, which ultimately ‘invert the sacred symbols of settler American identity and colonialism’ whilst challenging ‘the real and symbolic erasure of Indigenous peoples’.Footnote12 This intervention is both literal and symbolic, which was continued during the Occupation of Alcatraz. As the Indians of All Tribes would later proclaim: ‘We came to Alcatraz with an idea. We would unite our people and show the world that the Indian spirit would last forever… The idea was born and spread across this land, not as a fire of anger, but as a warming glow.’Footnote13

This was also key to the 1973 Occupation of Wounded Knee. This event, which is seen as a starting point for many with regards to Indigenous activism, is actually the latter phase of ongoing Indigenous resistance in the post-World War II period, and forms a link to the first occupation of Wounded Knee. In 1890, the US authorities were concerned about the growing power of the Ghost Dance movement – which was an Indigenous movement for spiritual and cultural renewal – inspired by the Pauite prophet, Wovoka. Whilst the US press spoke of an ‘Indian uprising’, the military were given orders to intercept a band of Ghost Dancers under the chieftanship of Big Foot.Footnote14 Despite the beleaguered nature of the band, mostly unarmed and containing women and children, the stand-off resulted in the deaths of Big Foot and his followers, who were simply seeking shelter and food.Footnote15

The events at Wounded Knee in 1890 would signify a conclusion to the so-called ‘Indian Wars’, after which assimilation would gather pace. However, this only offers a neat and teleological retelling of history, again fitting with the US ‘Master Narrative’. In 1973, Wounded Knee thus became a rallying call for Native Americans and served as a metonymic reminder of all the injustice served upon Indigenous peoples by the US government, and a platform from which to challenge ‘official’ history. Importantly, the staging of Wounded Knee in 1973 relied heavily on the events of 1890. As Elizabeth Rich explains:

The staging of the event was based on a rhetorical trope in which the place Wounded Knee came to stand for simply the site of the 1890 Big Foot massacre in which many of Big Foot’s people died, running from the advancing US cavalry. The invention of Wounded Knee marks a new effort to organize discursively as well as politically. An analysis of Wounded Knee as a site, an event, and a trope, reveals an agonistic approach to organizing that has become increasingly linguistic and symbolic since 1973.Footnote16

In the same way as the contemporary Ceremonial Big Foot Riders want to engage with the symbolic image and remembrance of Wounded Knee by re-animating the narrative as a yearly event with the purpose of engaging with the colonially imposed narrative. Rich continues: ‘Digging out of the rubble of these images by using, as tools the language and logic of the colonizers meant having to re-think, re-name, and re-write identity and history in a way that would problematize colonial codification.’Footnote17 Interestingly, Rich emphasises how the ‘language and logic’ of colonialism is directly engaged with via the trope of Wounded Knee, de-stabilising the colonially imposed meaning behind the event. Through a re-staging, animation through remembrance effectively re-codifies meaning by engaging with static depictions of history and culturally imposed stereotypes found in film.

Wounded Knee, instead of being a static narrative of victimhood becomes a moment of strength, renewal and spiritual resistance. Wounded Knee has become a symbolic trope in representing Native peoples and the legacy of resistance to AIM and beyond, in this manner: ‘Wounded Knee has come to represent the millions of Indians who died at the hands of the United States and it represents all that is wrong with the United States’ past. It represents the Indigenous condition throughout the world.’Footnote18 Whilst meaning via cultural discourse is complex and unstable, it is precisely these factors that offer Wounded Knee such discursive and political power when cultural difference and cultural hegemony are brought to bear. Wounded Knee ceases to be a static, ‘historicised’ event, and Taking Alcatraz’s visual imagery of the era, establishes a link to the colonial underpinnings that formulate a discourse of victimhood and images of ‘Indians’. As Rich continues: ‘It makes a space to articulate a different vision and story in order to establish a ground from which to make political, ethical and spiritual judgements.’ The site of Wounded Knee is continuously animated in this manner, and re-configured through cultural, spiritual and political engagements. The same is established in a similar way via Taking Alcatraz and its historical referents.

Cheyenne and Arapaho director Chris Eyre’s 2002 film Skins references such real-life locations to create a powerful symbolic effect. In the film, Rudy Yellowshirt (Eric Schweig) gives George Washington’s likeness at Mount Rushmore a bloody nose, echoing the Red Power movement’s earlier activism. Eyre makes use of the documentary form to add authenticity to his film, splicing archival and news footage within the narrative. This strategy suggests a link between film form and Indigenous activism that is key to Taking Alcatraz. Eyre, essentially, lends an alternative meaning to Mount Rushmore by connecting the space to Indigenous activism and leaving the historical meaning open to reinterpretation. The ‘bloody nose’ given to Washington could be seen as a red tear, representing the blood of Indigenous peoples. Rather than maintaining Mount Rushmore as a site of US colonial dominance, the Black Hills have been re-inscribed by Rudy’s red paint.

Taking Alcatraz confronts the viewer in precisely this manner, by making reference to previous acts of Indigenous activism, with the film representing real-life locations.Footnote19 By re-articulating the significance of the Occupation of Alcatraz, it places the onus on the viewer to interact with US–Lakota history, and thus invites the viewer to consider the structural imbalance of US–Indigenous discourse whereby dominant narratives serve the settler state. The Occupation itself references the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, which stated that all surplus federal land be returned to the Sioux. As such, this film offers an engagement with a narrative thread of US history that links to Indigenous political intervention in US historical discourse – one that offers alternatives to hegemonic ideas of the nation and nation building.

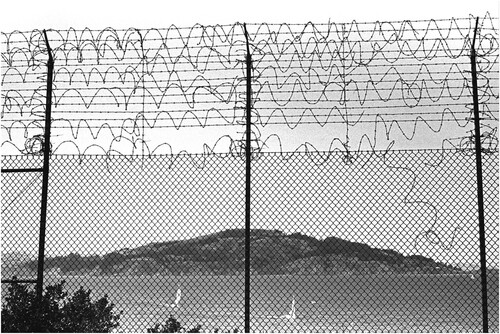

John Ferry, Taking Alcatraz, 2015, film still, courtesy the director, photograph: Ilka Hartmann, 1981

Nationalists such as Thomas Jefferson were committed to unlimited US expansion, which envisioned an empire with no place for the continent’s Indigenous habitants. As the nation’s population increased, settlers would occupy new lands in the West. Territorial expansion was key to the vision of the republic that Jefferson and the other ‘founding fathers’, held. The organising principle of this expansionism was essentially capitalistic, based on the ownership of land. This model of political economy could not tolerate the coexistence of alternative forms of social arrangement. As Jeffrey Ostler writes:

According to this theory, Indians had no right to continue wasteful and inefficient uses of land or to perpetuate barbaric social and religious practices once civilization made its demands. Thus, although U.S. policy recognized Indian tribes as nations with limited sovereignty and made treaties with them, American leaders envisioned nothing less than the eventual extinguishing of all tribal claims to land.Footnote20

This also suggests the ‘flexibility and adaptability’ of Lakota tradition, which lays the foundation for politicised and spiritual movements, such as those seen at Alcatraz and subsequently at Standing Rock. By linking events such as the theft of the Black Hills, the Fort Laramie Treaties and their subsequent contravention, and the AIM sheds light on past injustices whilst directing present and future activism. Articulation thereby takes the form of informative, linguistic and aesthetic protest as opposed to physical and militaristic. Footnote23 Furthermore, it shows how dominant cultural tropes can be used to engage directly with colonially imposed narratives by thinking differently about the world, the discursive-ised structures dominated by Eurocentric, patriarchal hierarchies, and the role of documentary in achieving this.

Indians of All Tribes’ Alcatraz Proclamation

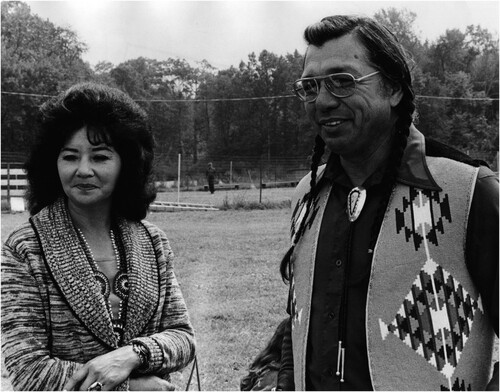

John Ferry has worked in documentary film since 1975, and has directed and produced a number of films, including Sitting Bull: A Stone in My Heart (2006) and Contrary Warrior: The Life and Times of Adam Fortunate Eagle (2010). The subject of the latter is the artist, activist and author of Heart of the Rock (2008), an account of the Occupation of Alcatraz. Born Adam Nordwall to a Swedish father and Ojibwe mother, Fortunate Eagle, along with Richard Oakes (Mohawk), was part of the early organisation to establish an ‘Indian’ presence on Alcatraz Island. Nordwall had apparently alerted the media to the first occupation of Alcatraz in 1964, which stands as a precursor to the 1969 occupation.

Evidently, the ‘dismissive’ reporting of a ‘Wacky Invasion’ was Fortunate Eagle’s doing, and not the media’s slippage into facetious stereotypes; however, such context could potentially reaffirm historical and cultural stereotypes of Native Americans. An activist whose specialism was publicity stunts, Fortunate Eagle had achieved just that, but the chemistry was not quite right for a successful occupation at this time. However, the anti-colonial ideology and use of humour and irony incorporated into public acts of Indigenous protest remained – notably in 1968, when Columbus’s ‘discovery’ of America was re-enacted with boy scouts dressed as Native Americans. In protest at this, Fortunate Eagle ‘scalped’ event organiser Joe Cervetto, flicking off his toupee with his ceremonial stick, much to the assorted amusement and chagrin of the crowd.Footnote24

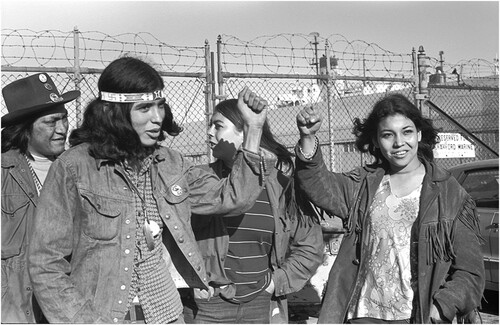

Adam Fortunate Eagle and his wife Bobbie, John Ferry, Taking Alcatraz, 2015, film still, courtesy the director, photograph: Ilka Hartmann, 1969

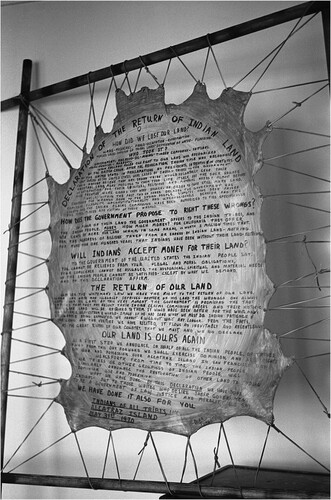

The use of humour and satire can be further illustrated by the original declaration that was presented at the onset of the Occupation of Alcatraz, on 20 November 1969, by a group of seventy-eight Native Americans. The Indians of All Tribes Proclamation, composed by Fortunate Eagle and his comrades, stated:

We will purchase said Alcatraz Island for twenty-four dollars ($24) in glass beads and red cloth, a precedent set by the white man’s purchase of a similar island about 300 years ago. We know that $24 in trade goods for these 16 acres is more than was paid when Manhattan Island was sold, but we know that land values have risen over the years. Our offer of $1.24 per acre is greater than the 47¢ per acre that the white men are now paying the California Indians for their land.Footnote25

The Indians of All Tribes Proclamation, John Ferry, Taking Alcatraz, 2015, film still, courtesy the director, photograph: Ilka Hartmann, 1969

The Proclamation has a playfulness, speaking to and representing an alternative take on a history that is usually presented as progressive and for the benefit of white Europeans under the auspices of a ‘manifest destiny’ – a narrative that was underpinned by Frederick Jackson Turner’s ‘Frontier Thesis’ (1893), which fostered ideas that were not subject to critical scrutiny – at least in the mainstream – for a hundred years. This animation of a less triumphant version of the US’s strategy of land acquisition offers a deferral of the dominant narrative. Furthermore, the use of humour and irony offers a non-aggressive route with which to consider the structural and historical power relations of the US, whilst animating pre-colonial Indigenous knowledge and identities. In the humour and irony is a seriousness. The emergence of pan-Tribal identity at Alcatraz evokes a collective Indigenous identity with which to counter cultural stereotypes perpetuated in Hollywood. Moreover, these tropes were also played on at Alcatraz, but in order to deconstruct colonial logics that underpin discourses, as opposed to counter filmic and cultural stereotypes.Footnote26

Furthermore, the Indians of All Tribes’ Proclamation was underpinned by the Fort Laramie Treaty, which agreed to return to Native peoples retired, abandoned and out of use federal lands, such as the forts that were historically situated along the Bozeman Trail. From this the organisers took their cue and reclaimed the site of the former prison, which had closed in 1963. This was not just an act of reclamation, but included actions to which Taking Alcatraz draws reference, such as cleaning up and converting the disused buildings into a site of education and training. The construction of an Indigenous Cultural Centre, and the establishment of a Central Council, which, as was stated, ‘is not a governing body, but an operational one’, was captured ineradicably by Ferry’s camera.

These acts on the island established an Indigenous presence, one that was firmly situated in the contemporary US. This Native American ‘space’ may have been ephemeral, but the documentary ‘capturing’ is a form of confrontation rather than absorption.Footnote27 Taking Alcatraz animates the space once physically occupied. Furthermore, the ironic references to Manhattan Island, which was seemingly ‘bought’ by the Dutch West India Company in 1626 with $24 worth of trinkets, continues the performative and ideological goals set out in the Proclamation, revealing an interactive performativity, but also exposing the tradition of Indigenous storytelling at the heart of the Proclamation’s narrative.

This continuum in literature and storytelling is perhaps best expressed in Tommy Orange’s (Cheyenne and Arapaho) 2018 novel There There, which offers a literary supplement to the visuals presented in Ferry’s Taking Alcatraz, and provides cultural continuity of Indigenous presence. There There not only presents an Indigenous interpretation, continuing the work of cultural commentators, artists, writers and filmmakers. It is these representations that counter dominant cultural formations animated by US constructions of the ‘Indian’.

Orange’s novel deals primarily with urban Native Americans who are disillusioned with the life forced upon them as a result of Termination and Relocation, and those urban Native Americans finding conditions in the cities no better than life on Reservations. The Proclamation goes on to state that Alcatraz Island is ‘more than suitable for an Indian Reservation, as determined by the white man’s own standards’, further concluding that the population of the island had been held as prisoners and dependent on others, with Alcatraz serving as a perfect metaphor and microcosm for US−Indigenous relations.

Détournement as Decolonial Strategy

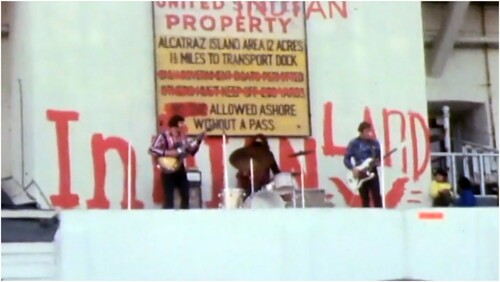

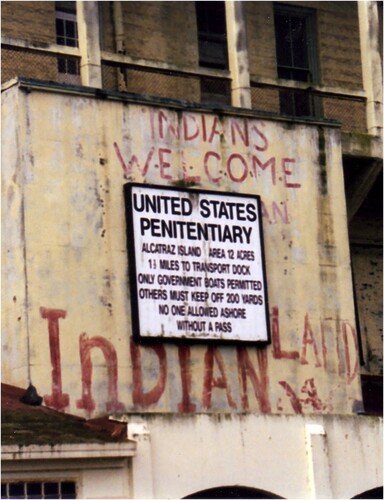

The IAT Proclamation can be considered a rhetorical détournement, that is, a document that presents a subversive reading of dominant historical discourse, with scepticism and irreverence as a decolonial strategy. Ferry’s images provide a visual aesthetic expressive of the pan-Tribal identity established by the Occupation and strategised by its leaders. A mid-shot of some of the activists in front of the derelict buildings of the prison which were re–faced with graffiti stating that the prison and island were now ‘United Indian Property’, emphasises how pan-Tribal Indigenous identity played a part in the Occupation of Alcatraz.

Whilst Alcatraz was unfit for human habitation, the occupiers immediately refashioned the buildings into a functioning community. Alcatraz Island’s resemblance to the Reservation illustrates again the arbitrary manner in which colonial practices have affected Native Americans. As Casey Ryan Kelly writes: ‘The IOAT Proclamation exemplifies the radical potential of détournement. Leading up to the occupation, movement leaders emphasised the importance of collectively reading the key texts used in defense of colonialism to expose their contradictions.’Footnote28 The desolate view from Alcatraz Island belies the spirit of community evident from the images of the Occupiers.

John Ferry, Taking Alcatraz, 2015, film still, courtesy the director, photograph: Ilka Hartmann, 1970

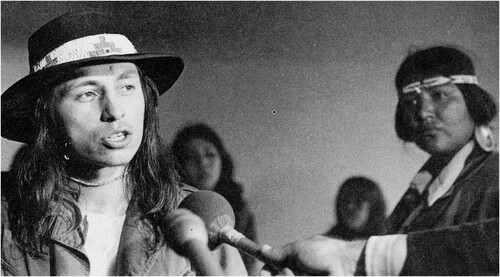

The declaration at the onset of the occupation, with the IAT leaders laying claim to the former federal prison ‘by right of discovery’, is deeply ironic. Playing on Columbus’s declaration that he had ‘discovered’ America, when it had been occupied for thousands of years, illustrates the deployment of détournement, and a way to re-read the white Euro-American colonial ‘discovery’ and occupation of America. Moreover, what the IAT did do exceptionally well was make their presence known, not only to the local San Francisco Bay Area – which would be a vital source of supplies in the coming eighteen months – but to the world’s media.Footnote29

John Ferry, Taking Alcatraz, 2015, film still, courtesy the director, photograph: Ilka Hartmann, 1970

This strategy, whilst initially caught in print media, and illustrated by Taking Alcatraz, forms and contributes to an ongoing media performativity that relies on a myriad of audio-visual imagery and cultural commentary in film, literature and other media to undermine colonial discourse. Indeed, the Occupation of Alcatraz, which was expressive of the cultural and political shifts of the sixties and speaks to the activism of the era, has parallels with contemporary art created by Native Americans. The woodblocks created by T C Cannon of Native Americans seemingly mimic Edward Curtis portraits, but in so doing reveal and overturn the colonial dimensions of the original pieces.

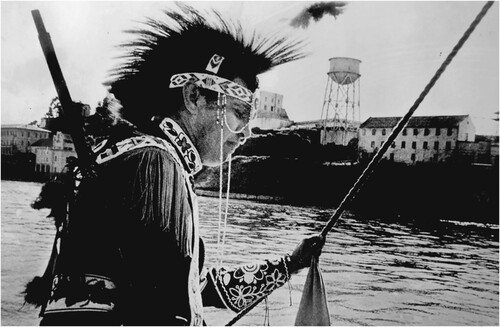

As such, the IAT, who were not all representative of the Plains tribes, effectively drew on cultural signifiers that had crossed between Native and white peoples via film and television, particularly the Western genre. Cultural motifs, typically attributed to the Plains tribes, such as the headdress, bow and arrow, tepee, and beating drums were utilised as a visual backdrop to the IAT on Alcatraz, as can be seen on the documentary footage that Taking Alcatraz director Ferry weaves into his narrative, such as an image of Adam Fortunate Eagle in full regalia.

Prominent anthropologist and cultural critic Margaret Mead noted how this strategy affected the public consciousness, describing the Occupation of Alcatraz as ‘a magnificent piece of dramatization’.Footnote30 As the grafitti and rhetoric of the occupation re–inscribed US political and cultural formations and replaced them with conceptions based on Indigenous ideas, Taking Alcatraz continues in this vein by offering a vision of the US that includes Indigenous peoples in its cultural imagination. The film became as powerful as the physical site of Alcatraz, itself reawakened by the very nature of that which is represented in the documentary.Footnote31

Adam Fortunate Eagle with Alcatraz in the background, © John Ferry, courtesy of the director and the Nordwall Archive, photograph: Beth Begsby, 1969

Détournement proposes an approach by which to engage with, and act upon, Euro-American history, and the ongoing practices of capitalism and colonialism. In the above instance, the IAT’s declaration evokes the Declaration of Independence, as well as US originary narratives and concepts, such as the myth of the frontier and ‘manifest destiny’.Footnote32 As Kelly confirms: ‘By arranging iconic selections of sacred Western political texts in a subversive parody, the IoAT illustrated how most Euro-American political texts are quite amenable to the colonial mentality.’Footnote33 This strategy undermines the hegemony of US mythology and dominant heteronormative white structures that have been naturalised within dominant cultural texts, such as the Declaration of Independence.

In addition, the satirical reference to the purchase of Manhattan Island in the IAT’s ‘Proclamation to the Great White Father’ set the tone for Alcatraz and a determined counter–colonial strategy based on non-violent protest, Indigenous knowledge and playing on stereotypical tropes of ‘Indians’ in contemporary culture and the mainstream media. These strategies would have great effect at Standing Rock.Footnote34 Such ideological animations, based not only on dominant texts, but on, and through, popular culture establish a Native ‘space’ in film and counter-hegemonic narratives that denaturalise white heteronormative interpretations of history.

Alcatraz Revisited

A discussion of Taking Alcatraz by the California Historical Society in July 2017, which featured Fawn Oakes, Richard Oakes’s (Mohawk) daughter and Sacheen Littlefeather,Footnote35 accentuated the political nature of urbanisation and the link between earlier periods of Indigenous resistance and contemporary concerns of Native Americans. Littlefeather, who was a student at the time, and a visitor to Alcatraz, would be cast into the mainstream media’s perception after she refused, on his behalf, Marlon Brando’s Oscar for The Godfather (Francis Ford-Coppola 1972) at that year’s ceremony. This was a strategy to gain recognition for the Occupation at Wounded Knee in 1973, and the wider American Indian Movement. Littlefeather was pressurised at the ceremony with arrest if she went over sixty seconds, and despite some of the audience’s negative reaction, she remained composed and dignified throughout. Littlefeather even recounts being backstage and John Wayne having to be held back by six security men, so incensed was he by her speech. More sinister was her retelling of how the FBI hounded her afterwards and effectively destroyed her media career.Footnote36

The Taking Alcatraz panellists discussed openly the context of the sixties and Alcatraz. Movements for civil and human rights, as well as fervent anti-Vietnam demonstrations, had begun in the US. There was an awakening of Native Americans across the country, and ‘Indian Rights’ came to the fore in the context of sixties’ activism and affected those Native Americans who had relocated to the cities. Whilst the Red Power movement has been reconsidered as a continuum of phases of Indigenous resistance, Alcatraz brought about worldwide media attention and dissemination of the plight of Indigenous peoples in the US; just as the Black Power movements, which highlighted the racial injustice towards African Americans in the US, did, whilst the anti-Vietnam war protests would rock the political establishment.

Ironically, the visuals of the IAT presented by Ferry’s Taking Alcatraz would have captured the contemporary US public imagination probably because of the cultural referents to ‘Indians’ only seen in film and television, which were now represented in visual and print media reporting of the Occupation. Playing on the ‘Indian’ would be essential to the performativity of Alcatraz, in order to spark wider recognition. As Vine Deloria Jr wrote: ‘The more we try to be ourselves the more we are forced to defend what we have never been. The American public feels most comfortable with the mythical Indians of stereotype-land who were always THERE.’Footnote37 Deloria refers not to the images projected by contemporary print media, which were largely positive during the occupation’s early phase. Rather, given the reality of Native Americans engaging in political discourse, occupying a public space, and having contemporary concerns which were aligned with other civil and human rights groups at the time, this was a strategy to play on their identity and the public imagination.

Whilst the media coverage of the Occupation was initially – uncharacteristically – sympathetic, by the end of the nineteen months views towards those on the island hardened, and news broadcasts resorted to the reporting that ‘warlike, violent Indians reminiscent of earlier colonial reporting had emerged’. It would seem that the occupiers early use of satire was key to winning favourable perception with reporters and those witnessing and perceiving events as conveyed in the media. Milner continues: ‘the majority of the Bay Area residents received their news of the occupation from mainstream sources. This time, however, the joke would not be on the protestors, but on the government, ‘manifest destiny’ and the society that had spawned the reservation system. This strategy of controlling representation by offsetting the mainstream media’s ‘Indian’ would prove, initially, a success at Alcatraz, and would also prove significant at Standing Rock in 2016 and 2017. Furthermore, the historic pattern of reporting was ruptured and expressive of the context of more progressive attitudes towards ‘race’ in the US, at the time due to civil and human rights movements during the sixties. As David Milner concludes: ‘The Alcatraz protestors rode the tide… fortuitously taking advantage of a rare, opportune moment in which the press, public and political pawnbrokers were demanding more favourable coverage of minorities than the established norm.’Footnote38

John Trudell speaking to the Press, John Ferry, Taking Alcatraz, 2015, film still, courtesy the director, photograph: Ilka Hartmann, 1970

As Taking Alcatraz illustrates, the Occupation of Alcatraz brings Native Americans into the consciousness of contemporary America and deconstructs cultural and filmic stereotypes by presenting an Indigenous presence. It is possible to witness the denaturalisation of dominant tropes of Indianness, and their associated meaning, as evidenced in Taking Alcatraz’s visuals, and the island’s occupants’ humorous play on their filmic stereotypes in order to gather attention. Timm Williams of the Yurok tribe, who participated in the Occupation, is often seen wearing a Plains-style headdress. The Yurok peoples are an Indigenous group from the Pacific coast, and their ceremonial headdress is constructed of a broad band of deerskin decorated with the red scalps of the woodpecker and is visibly different from the tribal headdresses associated with the Sioux, Cheyenne and others of the Plains region. Footnote39 This performative display suggests that film representations of Indigenous identity can offer a starting point that reveals the colonial structures and discourse, undergirding cultural stereotypes.

Conclusion

Taking Alcatraz determines links between contemporary Indigenous protest and the historical event which reveal the sedimented discourse associated with US colonialism. This imagery is all the more powerful for establishing that link and emphasises the importance of contemplating colonial structures when investigating filmic representations of Native Americans. The documentary medium has the potential to question historical power asymmetries within the US, particularly those animated by the cowboy–Indian binary that has found expression within the Western genre. Taking Alcatraz narrates the notion of a perpetual Indigenous resistance that was seemingly ‘ended’ at Wounded Knee in 1890, via the destabilising of cultural formations of Indigenous stereotypes that are perpetuated in mainstream film. Illustrating how representation is an ongoing aspect of discourse, and visual culture can impact and contribute to the investment and recovery of Indigenous identity, as opposed to the stifling cultural appropriation and mainstream media images of ‘Indians’ which perpetuate, via stereotypes, negative images of Native Americans.

Huge thanks to Jeff Geiger, Professor of Film at the University of Essex, for his guidance when preparing this article – all mistakes are mine. Thank you to John Ferry, director of Taking Alcatraz, and producer of LilliMar films for his assistance with the accompanying images in this article.

Notes

1 Judith Walker and Pierre Walter, ‘Learning About Social Movements through News Media: Deconstructing New York Times and Fox News Representations of Standing Rock’, International Journal of Lifelong Education, vol 37, no 4, 2018, pp 401–418

2 Jeffrey Geiger, American Documentary Film: Projecting the Nation, Edinburgh University Press, 2011, p 5

3 Richard Slotkin, Gunfighter Nation: The Myth of the Frontier in Twentieth-Century America, Antheneum, New York, 1992, pp 10–13

4 Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples [1998], Zed Books Ltd, 2013, pp 1–5

5 Robert Warrior (Osage) also notes that the frontier has been weaponised as discourse against Native Americans, calling the frontier an ‘ideologically imbued term that has served as a primary weapon in the material oppression of Native Americans in the Americas’. The People and the Word: Reading Native Nonfiction, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis and London, 2005, p xxvi. See also: Slotkin, Gunfighter Nation, op cit.

6 Geiger, American Documentary Film, op cit, pp 6–9

7 Castle McLaughlin, Lakota War Book from the Little Big Horn, Harvard University Press, 2014, pp 26–28

8 Donna L Akers, ‘Decolonizing the Master Narrative: Treaties and Other American Myths’, Wicazo Sa Review, vol 29, no 1, 2014, pp 58–76

9 Akers, ‘Decolonizing the Master Narrative’, op cit, p 59

10 Louis S Warren, God’s Red Son: The Ghost Dance Religion and the Making of Modern America, Hachette UK, 2017. Indigenous resistance to US colonialism persisted and adapted to the conditions of the early twentieth century and the period of assimilation. Luther Standing Bear’s life and writings are a perfect example of this. See also Jenny Tone-Pah-Hote, Crafting an Indigenous Nation, Kiowa Expressive Culture in the Progressive Era, University of North Carolina Press, 2018.

11 Casey Ryan Kelly, ‘Détournement, Decolonization, and the American Indian Occupation of Alcatraz Island 1969–1971’, Rhetoric Society Quarterly, vol 44, no 2, 2014, pp 168–190

12 Sam Hitchmough, ‘Columbus Statues Are Coming Down – Why He Is So Offensive to Native Americans’, https://theconversation.com/columbus-statues-are-coming-down-why-he-is-so-offensive-to-native-americans-141144, accessed 20 August 2020

13 See ‘The Taking of Alcatraz – We Hold the Rock!’, https://www.theattic.space/home-page-blogs/indiansalcatraz, accessed 3 November 2023

14 History of Big Foot’s Journey to Wounded Knee, https://healingheartsatwoundedknee.com/25-year-reunion-ride/history/, accessed 9 November 2020

15 Vestal, Sitting Bull, op cit, pp 276–277; see also Charles A Eastman, From the Deep Woods to Civilization: Chapters in the Autobiography of an Indian, University of Dakota, Scholarly Commons, pp 102–109, https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/235073202.pdf, accessed 3 November 2023

16 Elizabeth Rich, ‘Remember Wounded Knee: AIM’s Use of Metonymy in 21st Century Protest’, College Literature, 2004, pp 70–91; emphasis in original, in order to distinguish the place from the trope.

17 Ibid, p 78

18 Nick Estes, ‘Wounded Knee: Settler Colonial Property Regimes and Indigenous Liberation’, Capitalism Nature Socialism, vol 24, no 3, 2013, pp 190–202

19 See ‘Director Biography – John Ferry’, https://filmfreeway.com/423513, accessed 7 November 2020. The film intentionally transposes the viewer back to the reservation era and places the narrative on the significance of the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868. Taking Alcatraz is a 40-minute documentary that had a budget of around $10,000, and, in director Ferry’s own words, is meant as a ‘primer’.

20 Jeffrey Ostler, The Plains Sioux and U.S. Colonialism from Lewis and Clark to Wounded Knee, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge and New York, 2004, pp 13–15

21 Slotkin, Gunfighter Nation, op cit, pp 10–13

22 Jodi A Byrd, The Transit of Empire: Indigenous Critiques of Colonialism, Minneapolis and London, University of Minnesota Press, 2011, pp xx–xxv

23 Rich, ‘Remember Wounded Knee’, op cit, pp 78–82

24 See Sam McManis, ‘Adam Fortunate Eagle Nordwall: Bay Area’s Trickster Grandfather of Radical Indian Movement’, https://www.sfgate.com/news/article/PROFILE-Adam-Fortunate-Eagle-Nordwall-Bay-2781588.php, accessed 7 November 2020

25 Alcatraz Proclamation and Letter (1969), https://www.historyisaweapon.com/defcon1/alcatrazproclamationandletter.html, accessed 20 August 2020. Subsequent references to the Proclamation are taken from the reproduction on this webpage.

26 Byrd, The Transit of Empire, op cit, p xxx

27 Natchee Blu Barnd discusses the submerged ‘Native Spaces’ which can be deployed strategically by inhabiting – or playing – on Indigenous identity to contest colonialism. This includes using the concepts of the ‘Indian’ and Indian-ness, as cultural constructions as a site of investigation and disruption. See Natchee Blu Barnd, Native Space: Geographic Strategies to Unsettle Settler Colonialism, Oregon State University Press, 2017, pp 1–5.

28 Détournement was a strategy advocated by the Situationist International, a small collective of artists and intellectuals that formed in Paris in 1957, known for its avant-garde theory and influence on the 1968 student and worker movements. The strategy was to subvert dominant ideologies through a shift in the context of the cultural text, Kelly, Détournement, op cit, pp 168–190. See also Jan Matthews, ‘An Introduction to the Situationists’, https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/jan-d-matthews-an-introduction-to-the-situationists, accessed 24 August 2020.

29 David Milner, ‘By Right of Discovery: The Media and the Native American Occupation of Alcatraz, 1969–1971’, Australasian Journal of American Studies, vol 33, no 1, Special Issue: America in the 1970s, 2014, pp 73–86

30 Margaret Mead, quoted in ‘The Taking of Alcatraz – We Hold the Rock!’, op cit

31 Carolyn Strange and Michael Kempa, ‘Shades of Dark Tourism: Alcatraz and Robben Island’, Annals of Tourism Research, vol 30, no 2, 2003, pp 386–405; see also Carolyn Strange and Tina Loo, ‘Holding the Rock: The “Indianization” of Alcatraz Island, 1969–1999’, The Public Historian, vol 23, no 1, 2001, pp 55–74; see also Dean Rader, Engaged Resistance: American Indian Art, Literature, and Film from Alcatraz to the NMAI, University of Texas Press, 2011

32 Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies, op cit, pp 173–174, p 183

33 Kelly, Détournement, op cit, p 175

34 Milner, ‘By Right of Discovery’, op cit, p 75

35 Of course, it has since been revealed that Littlefeather’s Native ancestry was falsified. That said, the question of Native ancestry is one that has long been problematic in the US; defined, particularly by a coloniser-imposed blood quantum.

36 Taking Alcatraz Film Screening and Discussion, YouTube, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bLRXwK-o4qw, accessed 5 November 2020; panellist Troy Martinez was quick to emphasise the context of Alcatraz, the support from locals, and the initial good relationship with the press.

37 Quoted in David Treuer, ‘How a Native American Resistance Held Alcatraz for 18 Months’, New York Times, 20 November 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/20/us/native-american-occupation-alcatraz.html, accessed 27 October 2020; Vine Deloria Jr, ‘Custer Died for Your Sins: An Indian Manifesto’, Macmillan, New York, 1969, p 189

38 Milner, ‘By Right of Discovery’, op cit, pp 75–79

39 For an example, see Edward Sheriff Curtis’s 1923 photogravure at the Portland Art Museum’s online collection. For a photo of Timm Williams wearing the Plains-style headdress see Treuer, op cit.