Abstract

One of the new models for thinking the production of art in a new decolonialised art history might be the artist colony. Certainly, in Australia, one of the revolutions Aboriginal art has brought about lies in the way it takes place in a series of artist colonies: self-identifying and -regulating cultural centres that have little or nothing to do with any imagined national art. Australian artists have been involved with any number of artist colonies throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, not just in Australia but around the world. This article will address just one: the Abbey Art Centre in New Barnet, just outside of London. Owned by gallerist and ethnographic art collector William Ohly, the complex of studios operated from the late 1940s until the late 1950s as the base for a generation of Australian artists and art historians, who enjoyed an entrée into the English art scene offered to no others either before or after. In particular, we examine the artists Robert Klippel, James Gleeson and Mary Webb, who stayed between 1947 and 1949, and the art historian Bernard Smith, who stayed between 1949 and 1950.

We want to begin by suggesting that art history has always been a matter of art colonies. Art colonies are places where artists live and work alongside each other. Sometimes they are associated with the teaching of art and art schools, but this is not always the case. On other occasions they involve shared workshops, for example in printmaking, but again this is not strictly speaking necessary. They can exist either in smaller outlying towns or villages or in larger metropolitan centres; moreover, with regards the latter, it is not, for example, Paris that is the colony but rather certain districts within Paris, with Montmartre and Montparnasse being the best known. However, even within these quarters, they are to be found within particular neighbourhoods or building complexes. In Montmartre, the Bateau-Lavoir is the most celebrated; but before that there was the purpose-built Villa des Arts with more than sixty studios, many residential, where for more than thirty-five years the Australian expatriate John Russell lived and worked when he was in Paris, alongside, for instance, Paul Signac, Auguste Renoir, Eugène Carrière and Paul Cézanne. In fin de siècle Paris, the Villa des Arts was where Carrière painted Portrait of Paul Verlaine in 1890, Renoir painted Portrait of Stéphane Mallarmé in 1892 and Cézanne painted Portrait of Ambroise Vollard over some 110 sittings throughout 1898 and 1899. In Montparnasse, it was the purpose-built studio buildings that likewise became colonies: 31 rue Campagne-Première, for example, was where the Australian J W Power had his studio in the mid-1930s and where the Surrealist Man Ray lived and worked from the 1920s onwards, and was important as well for the wider French interwar avant-garde. On the same street, S W Hayter’s famed printmaking workshop and art school, Atelier 17, was named after its street number; Giorgio de Chirico, Tsuguharu Foujita, Othon Friesz and Wassily Kandinsky all had studios in the Cité des Arts at number nine in the interwar years; and the Hôtel Istria, where once Marcel Duchamp, Francis Picabia and Tristan Tzara resided, is number twenty-nine. Bound together by shared interests and concerns, these art colonies exist because they offer both the physical and the intellectual conditions that make art possible: sufficient light, topographic beauty, cheap rent and the opportunity to share ideas, materials and knowledge with others.

In this article we will closely follow the movements of four key Australian art figures in and out of the artist colony in London known as the Abbey Arts Centre. They are the abstract painter Mary Webb, the Surrealist painter James Gleeson, the half surreal, half abstract sculptor Robert Klippel and Australia’s foundational art historian Bernard Smith. Throughout the history of Australian art there have been a number of well-known and not so well-known artist colonies, both in Australia and around the world, where Australian artists have lived and worked. Among the best known outside Australia are Étaples, Pont-Aven and Giverny in France, and Newlyn and St Ives in England. Australian artists have also worked in artist colonies in America, at Provincetown in New England and Taos in New Mexico. In Australia, the best known were formed by the Australian Impressionists in camps around Heidelberg, just outside of Melbourne, and in the coves around Sydney Harbour in the late nineteenth century. Also, we would suggest – which, for us, goes to show the continuing power and relevance of the idea well into the twentieth century – there have been artist colonies at the Lutheran mission of Hermannsburg near Alice Springs in the Northern Territory, where famously Rex Battarbee and John Gardner came to know Arrernte man Albert Namatjira in the 1930s, and at Papunya, 150 kilometres west of Hermannsburg, where Tim Johnson and Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri worked alongside each other in the late 1970s, soon after the emergence of so-called contemporary Aboriginal art.

Other artistic cultures have also recently been paying attention to their artist colonies – not merely those in their own countries but also those around the world where their artists lived and worked.Footnote1 And this is to say that to think of the art of a nation in terms of artist colonies is necessarily to open it up to the outside, to think both of those artists from other places who come to work in a country and of those artists from that country who go to work in other places. It is one of the ways in which our new global or world art history gets written today, and was perhaps already being written before those terms existed. It is this problem that lies at the heart of the so-called School of Paris, which always, even in principle, included non-French artists, and it is something that has already been raised in a series of exhibitions. We might think, for example, of the Kandinsky-inspired ‘Origines et développement de l’art international indepéndant’ at the Musée du Jeu de Paume in Paris in 1937, which included the work of Power as well as ‘sculptures and objects from Polynesia, Oceania and New Zealand’; and of its echo in ‘Artistes étrangers en France’ at the Petit Palais in Paris in 1955, which included the work, among many others, of the Cuban Wifredo Arcay, the Greek Alkis Pierrakos, the Iranian Hossein Kazemi and the Armenian-Lebanese Zaven Hadichian, alongside the Australians Mary Webb and Helen Lempriere.

We suggest that in our new global or world art histories – but we can see it was already intuited before then – everywhere is a colony. That is, we now understand that there are no single undivided centres of art and art-making, whether it be a country or a city, but that it is always a matter of small, mixed centres of artistic activity. In a sense, then, the art-historical emphasis on particular artist colonies belongs to a space between the national and the post-national. The histories of artist colonies are notable because they are written within and against the dominant national histories, but they themselves also point beyond these national histories and towards that globalised, decentred art history to come. And perhaps, to recall the theme of this special issue of Third Text, we might say that the art history that results from this emphasis on artist colonies is necessarily polyphonous. It is not only to emphasise the gathering of artists from different places in the same place but also to say that no place exists outside of its relation to other places, for this history is always the history of the movement between art colonies. The art colony, then, as the term suggests, always exists in relation to another, be it the national or the metropolitan, and herein is the paradox: that it allows us to see this other as only itself another art colony.

We seek to write here a brief history of the ‘English’ – inverted commas – artist colony known as the Abbey, concentrating on the Australians who were there following its establishment in the years immediately following World War II. It is an artist colony that has largely fallen out of the national histories of both England and Australia, even though it was set in the village of New Barnet, then on the northern outskirts of London, and was in its early years dominated by Australian artists. More particularly, we want to see this tension between the national and the post-national played out not only in how we might understand the Abbey now but in how it was understood by its inhabitants back then. Put simply, we suggest, the founding of the Abbey opened up a certain post-national possibility for both English and Australian art history; but as this history moved on, both in terms of its art-historical understanding and its inhabitants, it passed over into the Australian. Here in our narrative we want to keep the two possibilities in tension, maintaining the distinct historical moment these artist colonies represent, both art historiographically and in terms of any actual history of Australian art.

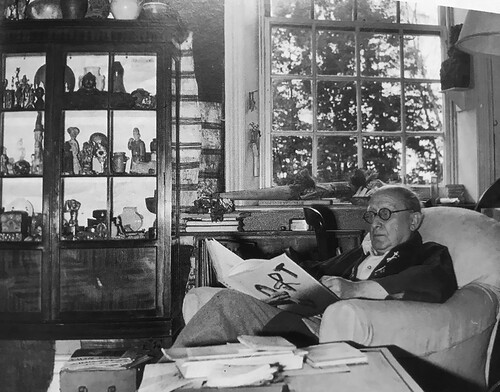

The Abbey artist colony was originally set up in 1947 by William Ohly, the British-born, German-educated owner of Berkeley Galleries, in Mayfair, which dealt principally in Asian and so-called primitive art. Ohly had opened the gallery in 1942, and he continued to run it throughout the war, among the city’s bombed-out buildings, for a traumatised public beset by food and medical shortages; and a year after the Allied victory he decided to make his three-acre New Barnet property, newly purchased from a failed religious order, cheaply available for artist studios. While the colony was conceivable only because Ohly was its landlord, it is also true that he was a crucial animator of life around the communal table and kitchen of the main house where he lived, which was set at the centre of the several barns, garden cottages and sheds that served as its studios.

Of course, the end of the war saw any number of artists hurrying to leave Australia and heading over once again to England and France, continuing a long line of Australian expatriate artists (and art students) that went back to the mid-nineteenth century. In the early 1900s such Heidelberg School Impressionists (so-called because they lived and worked around the then outer Melbourne settlement of Heidelberg) as Tom Roberts, Arthur Streeton and Charles Conder lived and worked in Chelsea. These are the artists who are enshrined as the first to produce a truly national art by Bernard Smith, who nonetheless observed that ‘it was in the Chelsea Arts Club that the Heidelberg School established its last and least distinguished camp’.Footnote2 And while the Abbey would be a residence for new arrivals after 1946, London’s art and culture world was already full of Australasians. We might just mention here the New Zealand-born but Australian knighted Sir Rex Nan Kivell, who had begun working for Redfern Gallery in Cork Street in 1925 before becoming its managing director in 1931, and the diasporic Cambridge-, Freiburg- and Sorbonne-educated Douglas Cooper, who, having been the co-owner of the Mayor Gallery in the 1930s and one of the so-called Monuments men after the war, was then cataloguing the Courtauld collection. (Cooper was also one of the world’s great collectors of Cubist art and a close friend of both Pablo Picasso and Francis Bacon, who himself, it has recently been revealed, was half Australian.)

But here we want to follow in particular three Australian artists who made landfall in London in 1947. The first is the Sydney artist Mary Webb, who trained with the Neopolitan Antonio Dattilo-Rubbo there in the 1930s, was a founding and long-term exhibiting member of the Contemporary Art Society (CAS) in the 1940s and was forty-five years old when she departed her home town on the HMT Asturias in March 1947. Her fellow passengers included the writer and broadcaster Alister Kershaw, the future Nobel Prize-winning novelist Patrick White, as well as the thirty-two-year-old Sydney Surrealist painter James Gleeson, our second artist, who had trained at East Sydney Technical College (now the National Art School) and was also an exhibiting member of the CAS. The third is twenty-seven-year-old Sydney sculptor Robert Klippel, who, discharged from the navy, and like Gleeson having studied at East Sydney Technical College, departs Sydney on the SS Priam, coincidentally on the same day as Webb and Gleeson.

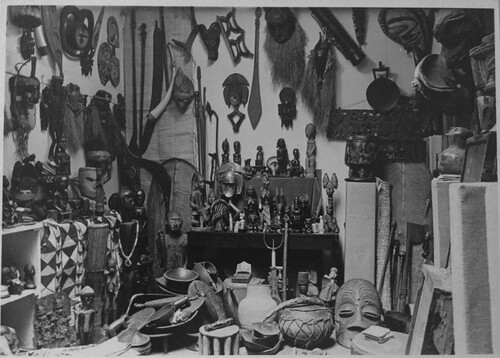

Arriving in April after a month aboard, Klippel moves to London and sees a small sign advertising artist studios to let at the Abbey in the window of Ohly’s Berkeley Galleries. He soon after moves there. At almost exactly the same time Webb also looks in the same window and sees the same notice and herself moves out to New Barnet. The two had not known each other in Sydney, insofar as Klippel was fresh out of art school, had never exhibited and was some eighteen years younger than Webb. On the other hand, when Webb and Gleeson first catch up in London, having known each other for years through their shared exhibitions with the CAS, Webb immediately tells him about the residential studios at the Abbey. Gleeson quickly moves into the main house; and together he, Webb and Klippel form a close intergenerational relationship, visiting either as a threesome or in pairs London’s museums, galleries, cinemas and theatres, and it is they who embody the first incarnation of the artist colony at the Abbey. In the months to come they will be joined by the Jewish German sculptor Inge Neufeld, who arrives from the Glasgow School of Art and would later marry the Melbourne printmaker Grahame King, following his arrival at the Abbey in late 1947. For his part, Ohly would regularly entertain his lodgers, lending them books from his library and sharing with them his collection of material from – to quote the 1952 Abbey Art Centre Museum brochure – ‘the South Seas brought back from Captain Cook’s voyages, a cast bronze from Benin in Nigeria, a Queen mother’s ceremonial stool from Ashanti and a host of other interesting objects from the Australian Aboriginals, ancient America, Egypt, China and the Melanesian islands’.Footnote3 (It was this Benin bronze that was recently sold at auction by Ohly’s grand-daughter for £10 million.Footnote4) At the time both the sculptor Henry Moore and painter Matthew Smith were regular visitors to the Abbey, and Ohly’s interests and wide-ranging connections brought other visitors over the years, including the British historian and broadcaster Kenneth Clark and German collagist John Heartfield.

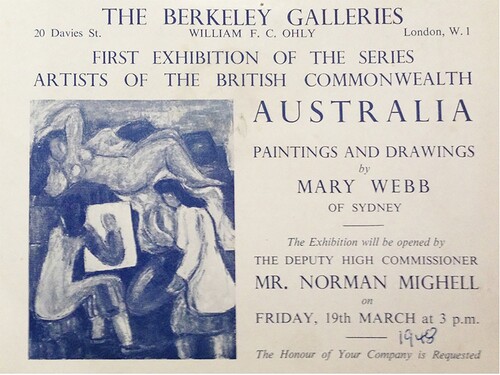

In May, Klippel, taking advice from the Italian-Scottish artist Eduardo Paolozzi, enrols in life drawing classes at the Slade. He will last less than six months there, and will write during this time in his characteristically acerbic tone: ‘My first impression is that sculpture in this country is just about turning over. Amazingly mediocre.’Footnote5 But it is also during this time that he will begin to work on (in the end, collaboratively with Gleeson) the well-known No 35 Madame Sophie Sesostoris (a Pre-Raphaelite Satire), with its title deriving from the clairvoyant character in T S Eliot’s poem ‘The Waste Land’. It was in May a year later that another of Ohly’s friends, the Belgian Surrealist E L T Mesens, visited the Abbey and met Klippel and Gleeson, and after seeing their work offered them an exhibition at his and Roland Penrose’s London Gallery, to be held in November. Before that, however, the exhibition ‘Paintings and Drawings by Mary Webb’ opened at Ohly’s Berkeley Galleries in March 1948. Webb’s show of mostly brightly coloured and somewhat expressionistic landscapes, still lifes and portraits, many of them set in the Abbey grounds, was relatively conventional. Certainly, it was judged to be so and found wanting when it was reviewed by the critic Eric Newton in the Sunday Times.Footnote6 Then in July, Webb, Klippel and Gleeson showed together in ‘Group Exhibition’, also at Berkeley Galleries, alongside a number of their fellow residents from the Abbey, after which Gleeson headed off on a two-month tour to Italy and France. And in July too – showing us that just over a year after arriving she was already establishing a profile for herself in London – Webb is included in the two-part group exhibition ‘Artists of Fame and Promise’ at the Leicester Galleries in Leicester Square, one of their ongoing series of well-known shows with this title.

Mary Webb exhibition invitation card, Berkeley Galleries, 1948, Mary Webb Papers, National Art Archive at the Art Gallery of New South Wales

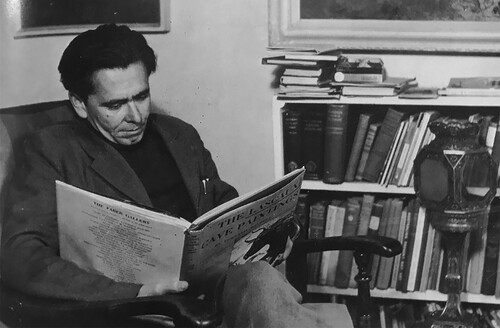

In September 1948 a thirty-two-year-old Bernard Smith, already the author of Place, Taste, Tradition: A Study of Australian Art since 1788 (1945) and fed up with his ‘anomalous position at the [Art] Gallery [of NSW], [where he was] never more than “a seconded teacher”’,Footnote7 boards the SS Stratheden departing Sydney for Southampton. He has received a British Council Scholarship for, in their words, ‘a piece of research on 18th- and 19th-century British art’.Footnote8 (This work will form the basis of his landmark European Vision and the South Pacific, eventually published in 1960.) Smith is travelling with his wife Kate and their two young children, and on their arrival the family stays initially for about a year at Kate’s family’s house near Ditchling, half an hour by train from London. Smith soon finds a room for himself in town, near Primrose Hill, where he works Monday to Friday. In his autobiography he reveals that he was asked to leave, having attempted to seduce his landlord’s au pair, and is hurriedly forced to find new accommodation, this time near Earl’s Court, the home of Barry Humphries’s legendary comedic figure of the 1960s and 1970s, Bazza McKenzie.Footnote9 How very ‘Australian’, we might say.

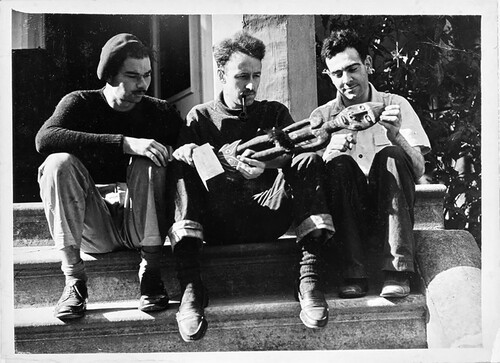

Robert Klippel (right) with two unidentified others at the Abbey with an unidentified sculpture from the William Ohly collection, c 1948, unknown photographer, National Art Archive, gift of Andrew Klippel, donated through the Australian Cultural Gifts Program, Art Gallery of New South Wales

The same month Gleeson returns to the Abbey from his two-month grand tour and less than a week later Klippel returns from his trip to Paris. In the month ahead they will complete the work for their upcoming show with Mesens at the London Gallery. Reunited with Webb, they resume their rounds of cinema and theatre, enjoying, or not, Medea, Le Diable au corps and Andalusian Dog, according to Gleeson’s diary entries.Footnote10 Then, on ninth November, the very day of Gleeson and Klippel’s exhibition, Smith is listening to Ernst Gombrich’s second lecture on ‘The Renaissance Approach to Classical Sculpture’ at the Courtauld Institute. Smith writes that, while discussing Michelangelo Gombrich said, ‘in a throw-away comment, “but then all art is conceptual”. It acted as a revelation.’Footnote11 This ‘revelation’ can be understood to be one of the keys that unlocks the argument of Smith’s European Vision and the South Pacific, which is in part about the way that European explorers came to the South Pacific with a neoclassical world view and, thanks to their encounter with the unclassified and perhaps even unclassifiable flora, fauna and even peoples they encountered there, returned to Europe with an effectively Romantic world view, thus changing European culture irrevocably. (We also cannot help but wonder what influence Ohly’s collection of Oceanic art and artefacts, which Smith eventually came to see at the Abbey, would have had on this book.)

Klippel and Gleeson’s exhibition, held in conjunction with three others, including one by Lucien Freud, includes, alongside No 35 Madame Sophie Sesostoris, fourteen sculptures and sixteen works on paper by Klippel and thirteen paintings and ten drawings by Gleeson. Nothing sells from it. Not long before it opens, Gleeson is photographed in his studio painting the head piece of Sesostoris, which seems to us clearly indebted to the objects in Ohly’s collection, with the image dominated by Gleeson’s large painting Agony in the Garden (1948), set beside him on an easel. Gleeson and Klippel’s exhibition will mark the end of the ‘triangle’ formed at the Abbey by its first residents, which had lasted just over eighteen months. The three artists, Webb, Gleeson and Klippel, had arrived in England within weeks of each other and each would leave within weeks of the other. Their future lives and careers would be irrevocably marked by the time they spent there together, all of it constituting a kind of unlikely and extended coincidence. Perhaps Gleeson’s painting can even be seen as something of an allegory of their time in the rundown studios set in the parklands of the walled-off artist colony on the outskirts of a still bombed-out London. For is it not asking, who if not us will remember them and this moment when they become who they are?

James Gleeson in his studio at the Abbey with his painting Agony in the Garden, 1948, image: courtesy of Estate of James Gleeson, Art Gallery of New South Wales

In late November Webb leaves England for some two months, initially heading for Paris and then going on to Italy. A week afterwards Klippel and Gleeson also travel together to Paris. There, through the agency of Mesens, they meet André Breton at the Café de la Place Blanche in Surrealism’s first city. Klippel will stay on in Paris for eighteen months, while Gleeson returns alone to London after Christmas, just in time to depart England permanently for Sydney on New Year’s Eve 1948. Back in Australia, he will enjoy a successful and long-running career as a Surrealist painter (the de Chirico-like but symbolist Italy (1951) is a good example of the kind of work for which he will become well known) and newspaper art critic (he will write for the Sun in Sydney from the year of his return, 1949, and also for the Sun-Herald from 1962, during which time he will provide a countervailing cosmopolitan perspective to the increasingly nationalist tone of the public discussion of Australian art).

While Gleeson is reacclimatising himself to life in Sydney, in January 1949 Smith joins London’s newly opened Institute for Contemporary Art (ICA), which he would later describe as ‘the only organisation in Britain at the time that sought to encourage innovatory art’.Footnote12 Formed the year before, the ICA’s inaugural exhibition was ‘40 Years of Modern Art’, followed by ‘40,000 Years of Modern Art: A Comparison of the Modern and the Primitive’, which opened just before Christmas and ran until the end of January. It is at a ‘Discussion on Primitive and Modern Art’ between institute co-founder Herbert Read and the anthropologist William Fagg, held in March to accompany this second exhibition, that Webb, briefly back in London to tidy up her affairs prior to her forthcoming move to Paris, bumps into Smith, and, as she had done with Gleeson, tells him about the Abbey, putting in train Smith and his family’s move to New Barnet later in the year. Fagg, who was close to Ohly and Read, would later publish a version of his side of the discussion as ‘Tribal Art and Modern Man’ in his collection The Tenth Muse: Essays in Criticism (1957). And, although Smith had already become aware of Aboriginal culture and the European reaction to it while working on Cook’s voyages back in Sydney, the ICA’s opening pair of exhibitions and Read and Fagg’s discussion was perhaps the second key that unlocked the logic of European Vision. By the end of March Smith had started writing the essay ‘European Vision and the South Pacific’, which would end up being published in the Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes the following year.Footnote13

By February Klippel was ensconced in another artist colony, this time in Paris at La Cité Fleurie on the boulevard Arago in Montparnasse, and in March Webb moved into what would be her lifelong apartment studio on the place Edmond-Rostand, just off the boulevard Saint-Michel in the heart of the Left Bank. Like the Villa des Arts and the Abbey, the Cité Fleurie was another artist colony formed by a complex of buildings, and Klippel surely obtained his new studio through the agency of the Dutch abstract artist César Domela, who had been resident there since 1933. In all likelihood, Klippel and Domela met the same way Gleeson and Domela had, by his attending Domela’s opening at the Galerie Apollinaire in London in June the previous year. In a letter to Gleeson not long after he had moved into his new residence, Klippel wrote of Domela’s perceptive take on his work, noting that ‘I showed him photos of my work and he was disconcerted as he considered ½ was Surrealism and ½ Non Objective.’Footnote14 In thus finding a studio in La Cité, Klippel was extending the line of Australians who had previously lived there, beginning with E Phillips Fox and Ethel Carrick, who had moved in months after they were married in 1905, with Carrick following the death of her husband in 1915 also teaching there. The Australian painter Stella Bowen, on the other hand, stayed a much shorter time, having moved there with her husband the novelist and editor Ford Madox Ford in 1923, where she entertained, for instance, Ernest Hemingway and James Joyce, only to take a studio the following year next to what will become Fernand Léger’s Académie Moderne on rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs. Webb, on the other hand, much less connected than Bowen, found a studio of her own just down from the Panthéon overlooking the Jardin du Luxembourg, the scene of so many of Carrick’s paintings.

In May, Klippel will hold his first ever one-person exhibition, which the Canadian tachiste Jean-Paul Riopelle had helped him hang, at the Galerie Nina Dausette in the back of her bookshop La Dragonne, among the fading embers of official French Surrealism. Besides Riopelle, he has now became friendly with the English sculptor William Turnbull, whom he met in London through Paolozzi, as well as French master of the palette knife Nicolas de Staël. For her part, Webb will come to know long-term Australian resident painters Kathleen O’Connor, who had by then returned to Paris from London, where she had spent the war, and Moya Dyring, whose Île Saint-Louis apartment will become known to a generation of Australian artist expatriates as ‘Chez Moya’. Within a year of leaving London she is showing in an international milieu, participating alongside, for example, Hans Hartung, Marie Raymond, Pierre Soulages and Francis Picabia in a small group exhibition at the legendary Galerie Colette Allendy. And now, as Klippel wrote to Gleeson, Webb was ‘doing Abstracts madly’.Footnote15

In the meantime, from July to September Smith, once something of a Surrealist painter himself, travels alone through Europe for six weeks, going first to Cologne and Nuremberg, then to Prague and finally on to Italy and France. By the time of his return to London, in early September, his family has already moved into the Abbey. Indeed, by this stage and certainly during Smith's stay – as had already been the case during the later months of Webb, Klippel and Gleeson – the Abbey was a thriving and cosmopolitan community, populated by artists from Australia (Oliffe Richmond, Grahame King, James Wrigley, Leonard French, Douglas Green and Noel Counihan), from Britain (Alan Davie, Philip Martin and John Coplans) and from elsewhere around the world (Peter Foldes from Hungary, Helen Grunwald from Austria and later Lotte Reiniger and Carl Koch from Germany). Smith mixed in particular with Noel Counihan, a fellow Communist and a Social Realist painter, and Davie, with whom he argued about Jackson Pollock’s paintings, which Davie had seen at the Venice Biennale in 1948 when Peggy Guggenheim had taken over the Greek Pavilion and displayed her collection when that country was unable to participate due to postwar political difficulties. Smith disapproved of them as part of his long-running objection to abstraction, which he would later make clear in the manifesto he wrote for the exhibition ‘The Antipodeans’ in 1959, where he speaks of abstraction’s ‘luxurious pageantry’ and its ‘innumerable band of camp followers [who] threaten to benumb the intellect and wit of art with their bland and pretentious mysteries’.Footnote16

Not long after his family moved to the Abbey and before his essay appeared in the Journal, Smith is hospitalised with pneumonia and acute nephritis and remains in care for three months. Following his release, he attends five ‘brilliant’ and ‘great’ lectures – his words – at the Courtauld given by Anthony Blunt on Picasso in May,Footnote17 and then in late August he visits museums in eight cities in Belgium and the Netherlands in eight days, before spending three weeks alone in Paris. Kate joins him there in late September, and the couple head south to Milan, Venice, Arles and Avignon before returning to London in mid-October. Then in November – after just over two years in Europe and one at the Abbey – Smith and his family board the HMS Otranto to return to Australia, arriving home on New Year’s Day 1951. Smith will immediately return to work at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, where he is compiling the first catalogue of the collection, and he will complete his Bachelor of Arts at the University of Sydney the following year. Later, in 1956 Smith will be appointed the third member of the Department of Fine Arts at the University of Melbourne – at the time the only place in the country to offer a degree in art history – as the first Australian-born lecturer alongside the Englishman Joseph Burke and the Austrian Franz Philipp. Also in 1956 he will publish his essay ‘Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner and Cook’s Second Voyage’ in the Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, and in 1960 the book now widely regarded as a foundational text of postcolonialism, European Vision and the South Pacific, 1768–1850, and then in 1962 his national, and nationalist, Australian Painting 1788–1960.Footnote18

For his part, Klippel, having returned to Sydney in June 1950, was asked by the pioneering geometric abstract painter Ralph Balson the following year whether he would like to share an exhibition with him at the Macquarie Galleries in May 1952 – it was opened by the architect Harry Seidler and reviewed positively by Gleeson.Footnote19 Five years later Klippel will leave Sydney for America with his wife – the American poet and writer Nina Mermey, whom he had met in Paris – moving first to New York and then to Minneapolis in 1958, where he will teach sculpture at the School of Art there until 1962, before returning to Sydney alone the following year.

For her part, Webb in Paris in 1949, to quote the Belgian art historian Michel Seuphor, ‘launched out into abstraction’,Footnote20 confirming Klippel’s earlier observation. The following year she held her first one-person exhibition in Paris at Galerie Colette Allendy, and in all she held three one-person exhibitions and participated in numerous small exhibitions there, in effect becoming an Allendy artist. In 1950, too, she began to show with the progressive Salon des Réalités Nouvelles, showing as sociétaire from 1953 until she ceased to participate in the Réalités Nouvelles, as they were by then known, in 1957. During this time she formed a close friendship with Seuphor and agitated successfully on behalf of her Australian colleagues Grace Crowley, Ralph Balson and Frank Hinder for their inclusion in Seuphor’s globalist Dictionary of Abstract Painting (1958), and all four were invited to participate in the accompanying globalising exhibition ‘50 ans de peintre abstraite’. In 1956 Webb became a founding member of the Club international féminin, and shortly before her death, in late 1958, she was awarded the Medaille d’argent de la Ville de Paris.

Following the death of the Australian artist-potter Anne Dangar in 1951 at the artist colony at Moly-Sabata on the river Rhône south of Lyon, overseen by the French Cubist Albert Gleizes, Webb began a correspondence with Dangar’s lifelong friend and confidante Crowley in Sydney, who was looking for a work of Dangar’s to gift to the Art Gallery of New South Wales in her honour. Having obtained and presented it to the gallery four years later, this offering was rejected by the trustees, then under the spell of Australian nationalism and uninterested in expatriates. And, ironically, the same fate would be visited upon Webb herself. Following her death in 1958, Seuphor will write to Crowley, hoping ‘that a few paintings of Mary Webb will enter now the museums and collections of Australia’,Footnote21 but this would not happen until 1975 when her work was purchased for the National Gallery of Australia – an acquisition in fact overseen by Gleeson acting in his capacity as curator for the not yet built institution – but her work remained unseen on the walls of any Australian state or national gallery until 2015.

To sum up, Klippel and Gleeson left the Abbey in 1948, Webb in 1949 and Smith in 1950. At the time Smith leaves there are still several Australians living there. And although the experience of it is decisive in Smith’s life and career – it is where he does his most important research and where perhaps he gets the two ideas that move his work from a study of Cook’s topographers to the extraordinary reverse perspective argument of European Vision – this is not reflected in any way in his Australian Painting, whose argument is based on genius loci, the spirit of place. Thus, Smith’s history places outside the category of Australian art our expatriate and immigrant artists. But with their movements to England and then on to Paris, Webb, Klippel and to a lesser extent Gleeson worked as part of the world and not apart from it. However, it is not only the reality of these artists’ experience at the Abbey but also its wider art-historical meaning that have not yet been properly considered. It is a story typical of so many Australian artists, who encounter influences not simply from overseas but while overseas and who thereby decide – in the case of Webb, forever, and for Klippel, for an extended period – to make their careers elsewhere. What we see in our examination of the chronology is that Webb, Klippel and Gleeson were in motion. They used the artist colony not as an end in itself but as a stopping point on the way to somewhere else. Yet this first generation of Australian artists in London after the war also knew that the experience – and the principle – of the Abbey was decisive, and in various ways it would become an essential part of their future practices. For Smith, however, who represents something of a second generation, it was different. Although his time in London was crucial to the construction of his art history, he makes not a single mention of the Abbey in Australian Painting. Likewise, the contribution not only of Australian artists but also of any of the artists at the Abbey to English art is barely if at all mentioned in its histories.Footnote22 What we can see, nonetheless, is that artists, if not art historians, do not construct their practice in terms of the national. Those Australian artists we have looked at here did not see themselves as making Australian art or drawing lines around what counted as Australian. Artists come from somewhere, they move somewhere else and sometimes stop for a period, as they have done for hundreds, if not thousands, of years. But when those first artists at the Abbey left and did things initially outside of Australia and then outside of England, they and their work were rendered invisible both by Smith’s Australianist history and by English art history’s equally nationalistic limitations and constructions.

Yet we can now hear their voices. Their stories are still available to us if we pay enough attention. Their whispers can still be heard, for instance, in the essay ‘A Summer in an Artistic Haunt’ written in 1885 by the American painter Annie Goater about her experiences at the famous Hôtel des Voyageurs at the artist colony at Pont-Aven on the Brittany coast, where the Australian artists Mortimer Menpes and Iso Rae were also working around this time. Goater writes:

Russia, Sweden, England, Austria, Germany, France, Australia and the United States were represented at our table, all as one large family, and striving towards the same goal… After lunch, on pleasant, sunny days, would follow the mid-day chat as, seated outside on hotel stoop and doorway, we leisurely sipped coffee and cognac… Criticism would be freely given and received; all were at liberty to say just what they pleased, and without any ill feeling. They were pleasant hours, indeed, spent around that Breton doorway and not wholly fruitless ones either.Footnote23

This polyphony, this confusion of tongues, is the new basis of art history today, out of which comes moments of dialogue, conversation, bursts of song. The history of art is a history of scenes, or as Ernst Gombrich tells us in The Story of Art, there is no such thing as the history of Art, only of artists.Footnote24 And if we wanted an image of this, we might look at the photograph of Ohly’s art collection in the basement of Berkeley Galleries in 1942, in which, in the middle of war, he tried to bring together the world’s art and create a safe space for it. And it is this that he also tried to do for all the world’s artists when the war was over. Like that photograph of Ohly’s collection, we hope to have brought the story of the Australians at the Abbey out of the art-historical basement and to have made it visible. It is only one of many such stories.

Acknowledgement

This research was funded by an Australian Research Council Discovery Project, ‘The Abbey Art Centre: Reassessing Post-War Australian Art, 1946–1956’ (DP200102794), 2020-2023.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 See eg Michael Jacobs, The Good and Simple Life: Artist Colonies in Europe and America, Phaidon, Oxford, 1985; Steve Shipp, American Art Colonies 1850–1930: A Historical Guide to America’s Original Art Colonies and Their Artists, Greenwood, Westport, Connecticut, 1996; Nina Lübbren, Rural Artists’ Colonies in Europe, 1870–1910, Manchester University Press, Manchester, 2001

2 Bernard Smith, Australian Painting, 1788–1960, Oxford University Press, London, 1962, p 152

3 ‘The Abbey Art Centre Museum’, London, 1952, np

4 ‘The Art Dealer, the £10m Benin Bronze and the Holocaust’, BBC News, 14 March 2021, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-56292809

5 Robert Klippel, ‘Sculpture Notes, Notebook 1945–50’, quoted in Deborah Edwards et al, Robert Klippel, exhibition catalogue, Art Gallery of New South Wales, 2002, p 33

6 Eric Newton, ‘The Value of Tradition’, Sunday Times, 28 March 1948, p 7

7 Bernard Smith, A Pavane for Another Time, Macmillan Education, South Yarra, Victoria, 2002, p 157

8 Ibid, p 158

9 Ibid, pp 251–252

10 James Gleeson, 1948 Diary, Papers of James Gleeson, National Library of Australia, MS 7440, Series 3, Box 7

11 Smith, A Pavane for Another Time, op cit, p 240

12 Ibid, p 293

13 Bernard Smith, ‘European Vision and the South Pacific’, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, vol 13, no 1/2, 1950, pp 65–100

14 Robert Klippel to James Gleeson, 22 February 1949, Papers of James Gleeson, Series 2, Box 4, Folder 29

15 Robert Klippel to James Gleeson, 20 June 1949, Papers of James Gleeson, Series 2, Box 4, Folder 29

16 Bernard Smith, The Antipodean Manifesto, exhibition catalogue, Victorian Artists’ Society Galleries, East Melbourne, 4–15 August 1959, reprinted in Ann Stephen, Andrew McNamara and Philip Goad, eds, Modernism and Australia: Documents on Art, Design and Architecture, 1917–1967, Miegunyah Press, Melbourne, 2006, pp 695–697

17 Smith, A Pavane for Another Time, op cit, p 388

18 Bernard Smith, ‘Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner and Cook’s Second Voyage’, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, vol 19, no 1/2, 1956, pp 117–154; Bernard Smith, European Vision and the South Pacific, 1768–1850, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1960

19 Gleeson wrote: ‘[The exhibition] brings some high tension excitement into Sydney’s somewhat drowsy artistic climate’. James Gleeson, ‘Abstract Art Show Exciting’, The Sun (Sydney), 21 May 1952, p 8.

20 Michel Seuphor, ‘Webb, Marie’, The Dictionary of Abstract Painting, Methuen, London, 1958, p 287

21 Michel Seuphor to Grace Crowley, 19 December 1958, Grace Crowley Papers, Art Gallery of New South Wales Research Library and Archive, Sydney

22 To take just one example, the Abbey is not mentioned at all in Stephen Alomes’s When London Calls: The Expatriation of Australian Creative Artists to Britain, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1999. We do note, however, the special issue ‘Transnationalism and Visual Culture in Britain: Emigrés and Migrants 1933 to 1956’ of the journal Visual Culture in Britain, vol 13, no 2, 2012.

23 Annie Goater, ‘A Summer in an Artistic Haunt’, Outing, vol 7, no 1, 1885, pp 10–11, cited in Lübbren, Rural Artists’ Colonies in Europe, op cit, pp 26–27

24 E H Gombrich, The Story of Art, Prentice-Hall, Hoboken, New Jersey, 1984, p 4