Abstract

Art historians trace the history of printmaking as a creative endeavour among Black people in South Africa to the mid-twentieth century. While these genealogies are valuable, they exclude and are silent on the deep history of printmaking as both an artistic and trade skill within the black press. Using a polyphonic art-historical framing, I tap into the Black archive to demonstrate how printmaking was cultivated as both a creative and a visual communications strategy by Black artists during the early 1900s. By examining printed images published in the Ilanga Lase Natal newspaper from 1903 to 1905, I propose a revised chronology of printmaking as a creative endeavour among Black people. The formative Black printmaking tradition I discuss was enabled by colonial-era multinational pharmaceutical enterprises that commissioned many of the etchings and engravings that appeared. A speculative art-historical approach is used to analyse and interpret the various visualisations of New Africans created by these early Black printmakers.

A review of select authoritative texts on South African art history locates the emergence of printmaking as a creative endeavour among Black people in the 1950s and 1960s.Footnote1 The gospel-like art-historical writings of, among others, Philippa Hobbs and Elizabeth Rankin, Juliette Leeb-du Toit, Elza Miles, Judy Seidman, Judith B Hecker and Gavin Jantjes and colleaguesFootnote2 carefully stitch together the genealogies of printmaking practices of Black people,Footnote3 tracing the genesis of printmaking to mid-twentieth-century schools that targeted Black creatives, for example Polly Street Art Centre (est 1949), Ndaleni Art School (est 1952) and the Evangelical Lutheran Church Art and Craft Centre at Rorke’s Drift (est 1962). My aim in what follows is not to discredit these essential educational mappings but instead to posit that the parameters of analysis, when engaging with the untold colonial-era art histories of Black people, must be consistently broadened.Footnote4 To this end the polyphonic art histories schema proposed in this special issue of Third Text is an opportune moment for considering alternate chronologies of South African printmaking histories.

Genealogies and timelines are central to the practice of art history.Footnote5 A cursory look at any major art-historical text or publication reveals the almost mandatory requirement to name, date, classify and organise artistic legacies in linear trajectories. However, there is a growing discourse that exposes the limitations of chronological accounts of the artistic histories of those who have been othered.Footnote6 Speaking within the context of queer performance cultures, the cautionary words of Benjamin Gillespie and Bess Rowen, regarding the shortcomings of sequentialised histories, are instructive for my argument here. They write: ‘chronology creates a false linear-progress narrative that does not value or underscore the dynamic exchange of aesthetic ideas, activist values, and alternative communities embedded in queer histories that offer the potential for new perspectives and critiques of the present’.Footnote7 Similarly, the prevailing date-stamped records of printmaking among Black people in South Africa – written almost exclusively by white art historians – has resulted in ‘false linear-progress narratives’ that inhibit the production of alternate and unrecorded stories or oral accounts that unsettle the canon. While I lean on many of the publications authored using chronological art-historical methodologies, especially in my vocation as an art educator, I am equally critical of the restrictions embedded therein. This article is another attempt to chronicle untold narratives of the rich Black artistic legacies that were simultaneously compromised and nurtured by colonial encounters. The intolerable irony is that to destabilise the existing taxonomies of histories of printmaking in South Africa, I must make use of the very linear chronology methodology.

Using the verifiable archive together with a speculative interpretation of history – in keeping with the precepts of this special issue – I present a revamped timeline showing the earliest manifestations of printmaking among Black artists during the early 1900s. I must emphasise that this undertaking would not have been possible without relying on the fact-based library archive. To retrieve the images created by early Black printmakers, I spent a long time at the South African National Library in Pretoria, scanning through their diligently preserved microfilm copies of the Ilanga Lase Natal newspaper.Footnote8 As stated, the paradox herein is that Black art historians depend on elite colonial-era knowledge and social institutions such as the national library to produce redemptive South African art histories.

The Influence of the Early Black Press

The printmaking medium was among the first ‘modern’ artistic modes used by Black creatives of the early twentieth century to translate the changing Black experience into images. The primary vehicle that enabled the production of these printed images and their eventual dissemination to a wide audience was the newspaper. Through church-based printing presses that were established to spread the Gospel to Africans, various Black-run newspapers were birthed during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.Footnote9 The interest of the early Black press was, according to Tim Couzens, the production of material specifically targeted at a Black readership, the content of which was almost exclusively directed by Black intellectuals.Footnote10 These rurally based publishing enterprises were working at the coalface of articulating the aspirations of African modernity, and, as Ntongela Masilela postulates, it was only later, in the 1930s to 1950s, that urban-based publications like Bantu World and Drum entered the fray, projecting the sociopolitical voices and subjectivities of Black people.Footnote11 Furthermore, the introduction of printing presses in Black African communities during the colonial era had significant socioeconomic spin-offs, resulting in ‘higher social capital leading to higher economic activity and higher well-being’, both within the communities where the presses were based and more broadly in the spaces where the newspapers were distributed.Footnote12 Hlonipha Mokoena also observes that beyond being vehicles for punting Christianity, these mission-based Black ‘newspapers were used by the literate as a source of local and international news, as fora for the airing of grievances, as expressions of class aspirations, and as platforms for publishing texts as diverse as poems, clan genealogies and even reports of sporting events’.Footnote13 As seen in the examples I present later, the representation of a certain calibre of individual was central to the image-making conventions adopted by this early Black printmaking tradition.

One of the newspapers that aggressively promoted printmaking as an artisanal praxis among Black people was Ilanga Lase Natal. Established in 1903 by Dr John Langalibalele Dube and his wife Nokuthela Dube, Ilanga Lase Natal is one of the leading bilingual newspapers in South Africa, printed in both isiZulu and English, and is considered ‘the longue durée of the black press’ due to its continuing existence over a century later.Footnote14 It was not only targeted to the isiZulu reader, as there were regular inserts of articles dealing with matters relating to Sotho, Xhosa and white (English and Afrikaans speaking) readers. Advertisements utilising various visuals were flanked by text seeking to tap into the vast Black readership market. As I will discuss, some of the adverts included testimonials by prominent Black people, such as chiefs, professionals, clergymen and even Dube himself, who benefited from using the products.

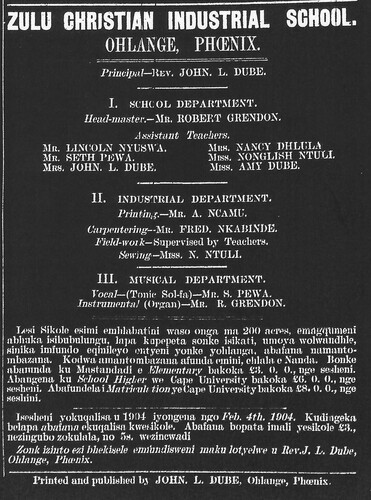

For the initial print runs of Ilanga Lase Natal, Dube used the International Printing Press on Grey Street in Durban.Footnote15 This was a multilingual press established in 1898 as a trading offshoot of the Natal Indian Congress, but, as Isabel Hofmeyr phrases it, in effect it was Gandhi’s printing press in light of how the influential Mohandas K Gandhi, who had arrived in South Africa from India in 1893, used it to advance the political and civic interests of Indians through publications like Indian Opinion, established in 1903.Footnote16 Then from October 1903 onwards production moved to the Ohlange Institute (initially known as the Zulu Christian Industrial School) after a press had been imported from America.Footnote17 Founded by the Dubes,Footnote18 the institute opened its doors in 1901 and is celebrated as ‘the first education institution for Africans by Africans’.Footnote19 It is unsurprising that such a pioneering institution of Black education played a leading role in the development of printmaking among Africans.

In 1903 several adverts appeared in Ilanga Lase Natal calling on interested individuals to enrol at the Ohlange Institute. They gave details of the personnel who served at the school:Footnote20 listed as principal was Dr Dube and within the Industrial Department was a printing section overseen by a Mr A Ncamu (expanded to Mr A JNO Ncamu in 1904). The existence of a press fully owned and operated by Black individuals enabled the careers of Black professionals, including artisan printmakers like Ncamu, to advance within these publishing houses. At the dawn of the twentieth century printing technology had advanced to the degree that photographs were being reproduced in newspapers and periodicals throughout Europe and America. However, for the fledgling Black press in Africa, which relied on older presses that had either been donated or sold at a discount to the missionary institutions, pictures of people were inserted into newspapers and books through wood engravings or later half-tone photographic exposures.Footnote21 There is no harm in speculating that when non-photographic images appeared in Ilanga Lase Natal from late 1903 onwards, they were created by a Black printmaker who had made engravings or etchings based on photographic originals. And since Ncamu is recorded as the expert in the printing section of the Industrial Department at Dube’s school where the Ilanga Lase Natal printing press was housed, it is not far-fetched to ascribe to him the status of being among the earliest Black printmakers in South Africa. In the absence of further evidence to triangulate this finding, I will refrain from evoking Ncamu’s name when thinking about the possible makers of the images under discussion here. That said, it remains indisputable that the existence of Ncamu is evidence enough of other Black printmakers who practised during and after his brief mention in the Ilanga Lase Natal adverts for Dube’s Ohlange Institute.

Unfortunately, rapid advancements in the mass reproduction of photographic images in newspapers rendered these antiquated processes obsolete within the newspaper publishing industry by the 1910s. Although the vocation of printing continued within the various Black presses throughout the 1920s and up until the 1940s,Footnote22 printmaking per se did not resurface again until the 1950s and 1960s, when Black students in the emerging art schools were introduced to the craft of printing as an artistic endeavour, with an emphasis on concept, narratology, authorship and ownership as part of the creative process. Another constraint is that the very classification of a Black printmaker or artist, in the Western conception, was not readily accorded to Black artists during the early 1900s. Thus, the printmakers who created these images could not be acknowledged as such, which also contributed to their non-inclusion in the various anthologies of South African art histories. It was only during the 1920s and 1930s, with the emergence of Simon Mnguni, Moses Tladi, George Pemba and Ernest Mancoba, that Black creatives were acknowledged for the first time as virtuoso artists, and much later in the 1950s that printmaking was acknowledged as a creative practice among Black artists. For Daniel Magaziner, these artists literally ‘invented the idea that you could be an artist’ as a Black person in the Westernised art production paradigm.Footnote23

Lithograph Colonial Archetypes of Africans

Before examining the images produced by whom I speculate were the first Black printmakers during the early 1900s, it is critical to appreciate the coming into being of these illustrations within the context of global, or more pointedly Euro-American, visualisations of the African. Although Ilanga Lase Natal was not a provincial newspaper concerned exclusively with the stories and subjectivities of isiZulu speakers, its founders were of Zulu ancestry and sought to counter the problematic stereotypes of Zulu and African people generally within the Western imaginary. As confirmed by Robert T Vinson and Robert Edgar in their reading of representations of Zulu people in the American cultural circuit from 1880 to 1945, ‘portrayals of the Zulu depicted Africans as permanent primitives’.Footnote24 Due to his exposure to America society, Dube was acutely aware of these paternalistic caricatures and would have actively worked to create alternate visualisations of the modern African within the pages of Ilanga Lase Natal.

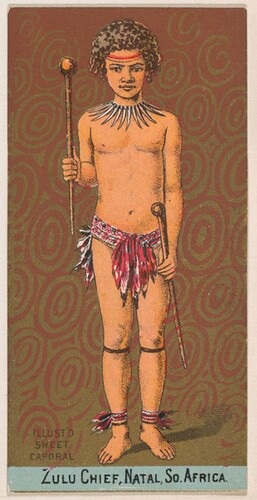

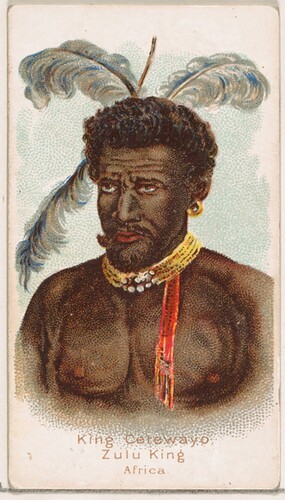

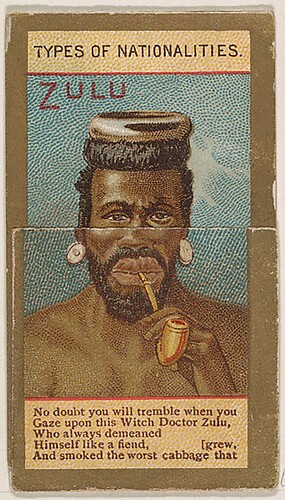

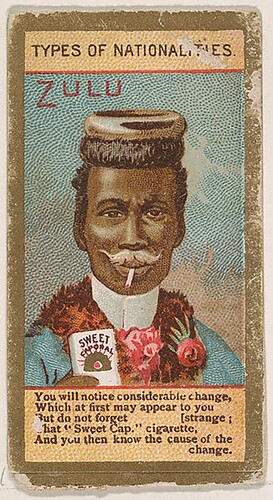

Besides depictions of Africans in trade shows, exhibitions, carnivals, circuses and so-called fine art, some of the most compelling creative illustrations of a fictionalised Zulu identity made by Americans were the trading cards produced and issued by tobacco companies. These foldable cards were a regular staple of tobacco advertising and marketing of the era and played a critical role in normalising smoking. Iain Gately reports that the cards were both collectible and extremely popular among children, who ‘hoarded their pocket money or pestered their fathers’ to purchase cigarettes, seeking to land some of the rarer trading cards.Footnote25 To support the point that the visualisations in Ilanga Lase Natal were a pushback against colonial archetypes of Africans, I would like to focus on a few cards that showcased Zulu people, produced by the Kinney Brothers Tobacco Company, later American Tobacco Company, and William S Kimball & Company during the late nineteenth century. The cards created by the Kinney Brothers were part of the Types of Nationalities series, which sought to expose American audiences to the ‘colourful’ and ‘diverse’ peoples of the world. While several other African cultural groups were portrayed, the Zulu icons were of special interest to Americans. On account of its rather spectacular but short-lived victory over the British in Isandlawana, briefly stunting the imperialist advances of the British Army, the Zulu nation had garnered a myth-like status of barbarous bravery.Footnote26

Kinney Brothers Tobacco Company, Zulu Chief, Natal, South Africa, from the Military Series, 1888, commercial colour lithograph, 7 × 3.8 cm, Jefferson R Burdick Collection, image © The Met Open Access Collection

William S Kimball & Company, King Cetewayo, Zulu King, Africa, from the Savage and Semi-Barbarous Chiefs and Rulers series, 1890, commercial colour lithograph, 6.8 × 3.8 cm, Jefferson R Burdick Collection, image © The Met Open Access Collection

In an attempt to capture this partly admiring, partly revulsive dialectic of the valiant Zulu savage, various oscillating illustrations of Zulu people appeared. The first is an 1888 Kinney Brothers cigarette card of an adolescent Zulu boy who is identified as a Zulu chief.Footnote27 This vividly coloured lithograph shows a light-skinned subject with Nubian facial features dressed in a typical Zulu outfit with an animal bone/teeth necklace and holding two knobkerries. The overall design of the image is evocative of wallpaper through its inclusion of a textile pattern of repeated circular shapes in the background. In contrast to the highly successful aesthetic appeal of the card, its failure is the promotion of the colonial view of the African leader as an infantile who needs the guidance of an all-knowing European. On the other hand, the William S Kimball card of King Cetshwayo kaMpande, misspelt as ‘Cetewayo’, provides a more redeeming picture of Zulu nobility. True to form, this card shows Cetshwayo as a physically imposing figure, an image symbolic of how the Zulu warrior was seen in Western culture. Feathers inserted in Cetshwayo’s hair and a beaded necklace soften the bravado of the figure. Although King Shaka Zulu, who ruled the Zulu Kingdom from 1816 to 1828, is considered the prototypical motif of an African warlord, ‘in the late nineteenth century Cetshwayo was far and away the most prominent symbol of Zulu leadership’.Footnote28 While this fantastical image is more respectful in its veneration of Cetshwayo as a great leader, its limitation resides in the innuendo that he is so because of his supposed brute strength as opposed to military strategy and astute leadership qualities. Yet, on the other hand, the most iconic photographs of Cetshwayo taken in 1879 at the cessation of his reign show him ‘as a composed and Anglicized subject’.Footnote29

Kinney Brothers Tobacco Company, Zulu, from Types of Nationalities, 1890, commercial colour lithograph, 17.4 × 3.7 cm, Jefferson R Burdick Collection, image © The Met Open Access Collection

Kinney Brothers Tobacco Company, Zulu, from Types of Nationalities, 1890, commercial colour lithograph, 17 × 3.7 cm, Jefferson R Burdick Collection, image © The Met Open Access Collection

Zulu people, and Africans at large, were persistently suspended between being visualised as illiterate and backward on the one hand, and as sophisticated modern Black Westerners on the other. While it was generally accepted that the transformation of African societies from traditionalism to modernity would mainly occur through exposure to Western education and ‘religious proselytising’,Footnote30 consumption of Western goods was also seen as a critical facilitator in modernising African peoples. As seen in the Kinney Brothers image, a Zulu smoker identified as a ‘Witch Doctor… who always demeaned himself like a fiend is presented smoking his traditional pipe.’Footnote31 Once the card is folded, the same figure is shown smoking a Kinney Brothers cigarette. The claim made in this advert is how the banal act of smoking Sweet Corporal cigarettes has transitioned the Zulu man from a conjurer of demon-like evil spirits to an upright man dressed in classy Western regalia. What these exotic pictographs of Zulu people reveal is the domestication of the colonial logic that renders Africans as unsophisticated and premodern throughout Western visual culture. While it is true that the average American collector was probably more interested in the rarer trading cards of baseball sporting icons like Honus Wagner,Footnote32 the prospect of having an accessible and fairly cheap pictorial archive of nationalities of the globe was equally compelling. Cigarette trading cards were a cultural phenomena which later fetched hundreds of thousands of dollars in the secondary auction market. But, more pointedly for my discussion, they provide the ideal backdrop to this introductory analysis of the repository of printmaking images published by the Black press.

Examples of Early Black Printmaking

What, then, were the images created by this first generation of unacknowledged Black printmakers? In short, they were concerned with imaging and imagining what Pixley ka Isaka Seme, the famed thinker and politician, described as the New African.Footnote33 In the context of the early twentieth century, the New Africans – members of the New African movementFootnote34 – were highly educated men and women – though women are sadly under-acknowledged in New African movement historiographies – who were trained at the Christian missionary schools and, at times, European and American universities. This elite group of New Africans wielded great influence among African communities, either because of their royal disposition or social status, and perhaps most significantly, as Helen Bradford puts it, they were ‘viewed by the masses as having political skills, and as being capable of challenging the white man successfully’.Footnote35 Of interest is how this mystique was solidified by the portraits published in Ilanga Lase Natal and other newspapers like it. These carefully curated images were habitually communicated to a mass Black audience throughout the country, who perceived them as archetypes of the transcendental modern African.

Of significance is how the creation of printed images in Ilanga Lase Natal was facilitated or enabled by the enterprises that sold the hugely popular Dr Williams’ Pink Pills and Doan’s Backache Kidney Pills.Footnote36 While other Western drugs were accorded advertising space during the early years of Ilanga Lase Natal, Dr Williams’ Pills, product of G T Fulford & Co, established in 1887 by Canadian entrepreneur George Taylor Fulford I, were by far the most promoted medicinal brand.Footnote37 The commercial success of the drugs it sold helped G T Fulford to expand into eighty-two countries, including British-controlled territories like South Africa. This phenomenal transnational distribution network was enabled by colonial trading routes. Dr Williams’ Pills were an iron supplement and immune booster, extremely effective in helping patients recover from most minor ailments. In keeping with the highly lucrative advertising strategy used in America, Australia, Britain and Canada, the images of happy and satisfied clients placed alongside the adverts also contained endorsements by respected New African leaders who had used the product. Though Africa, or South Africa to be specific, is not acknowledged as one of the destinations where Dr Williams’ Pills were shipped, ‘the persistent use of advertisements in the popular press’, and in the case of South Africa, the independent Black press, made the pills ‘an international success’.Footnote38

In a process Max Huang terms ‘transcultural translation in selling medicine’,Footnote39 the printed image and isiZulu text were used to validate the efficacy of the product through textual and visual testimony – discernible in how healthy, full of life and upstanding the clients looked in the images. Furthermore, the advertising income the pills generated for Ilanga Lase Natal was indispensable. The fact that the images were effectively commissioned by multinational companies that had offices in Cape Town, New York, London, Sydney and Shanghai raises several questions of interest. Could the etchings and engravings of the various New Africans in the ads have been commissioned from an independent artist – independent of the Ilanga Lase Natal newspaper – who would have been most likely white? Or was this important duty of validating Western medical products via the printed image ceded to the newspaper to facilitate in-house? Evidence from other parts of the world points to the latter. Speaking on how Western medicine was magnificently marketed and distributed in the early twentieth century Asian market, Huang confirms that homegrown ‘Chinese advertisement designers played an important role in localising and circulating Western consumer culture’; however, he laments that ‘unfortunately we do not have much information about these Chinese designers. Yet their works still exist’.Footnote40 Likewise, in the South African context, though their biographies are unrecorded, the work of early Black printmakers remains, and their story still needs to be told.

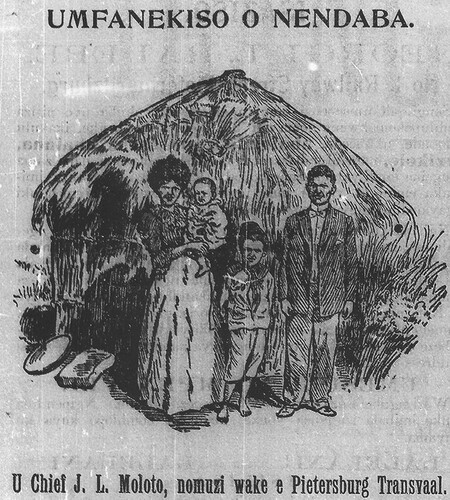

Chief J. L. Moloto and his family in Pietersburg Transvaal (Advert for Dr Williams Pills), engraving for newspaper, ‘Umfanekiso o nendaba’, Ilanga Lase Natal, 18 September 1903, p 8

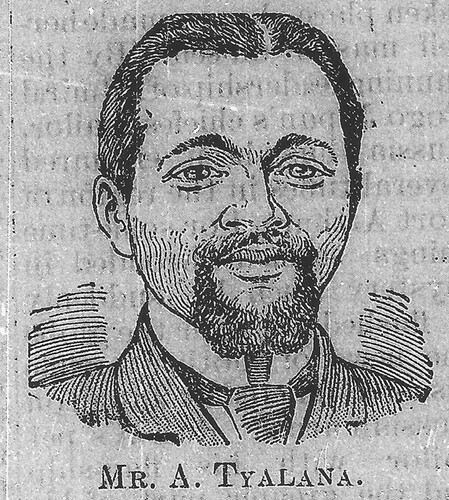

Mr A. Tyalana (Advert for Dr Williams Pills), engraving for newspaper, ‘Wa hlutywa izilonda ezidhluzayo’, Ilanga Lase Natal, 29 April 1904, p 3

This brief explication of the newspaper-based prints produced by those I propose to be the first Black printmakers of the twentieth century is decidedly speculative. The few images shown here are formative artistic visuals produced in the Black press in what is considered a modern artistic idiom – ie printmaking – from 1903 to 1905. To this end, I contend that the printmaker(s) who created these images were keenly aware of the artistic properties of their work. In the image of Chief J L Moloto and his family, for example, the use of the word umfanekiso (picture/illustration) as opposed to isithombe (photograph) in the article title highlights the acute awareness of Ilanga Lase Natal that the image they are publishing is different from a conventional photograph. Although the picture obviously presents the likeness of Chief Moloto and his household, umfanekiso attempts to convey the fictive and imagined character of the image to the reader – it makes clear they are looking at an invented image. Furthermore, the insertion of the person’s name underneath the depiction aligns these prints with the genre of portraiture.

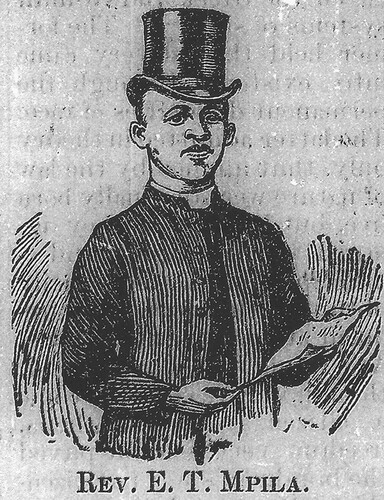

Rev. E. T. Mpila (Advert for Dr Williams Pills), engraving for newspaper, ‘Isihlobo Somkake’, Ilanga Lase Natal, 25 March 1904, p 3

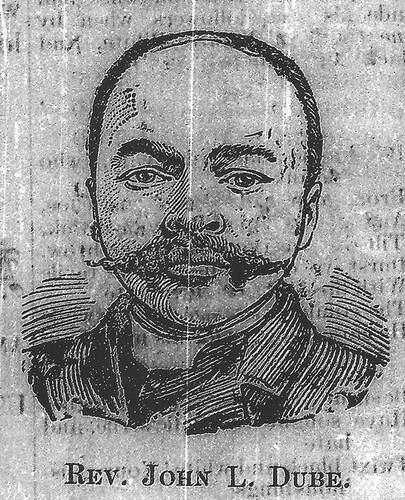

Rev. John L. Dube (Advert for Dr Williams Pills), engraving for newspaper, ‘Ukukatazwa isibindi ne sisu’, Ilanga Lase Natal, 1 April 1904, p 3

Although the images produced by these first Black print artists were highly mimetic insofar as they sought to capture the likeness of the person being depicted, as seen in the image of the Reverend E T Phila and the Reverend John L Dube, the founder of the newspaper, the idiosyncratic nature of the imprint(s) of the artist(s) who etched and engraved for Ilanga Lase Natal is without question palpable in the style of the various pictures. Reporting on nineteenth-century newspaper image printing processes in the Western world, the Illustrated Image Analytics Project at North Carolina State University corroborates that ‘while many periodicals represented their illustrations as visual facts, they were subject to a chain of interpretation, adaptation, and image adjustment all along their production path’.Footnote41 They further crudely explain the idiosyncratic process of creating wood-engraved images for newspaper printing at the time as follows: ‘A typical illustration might start with a sketch or photograph, taken by an artist-reporter at a news event, or even a written description which adapts an idea (whether it was actually seen or not) to visual form.’Footnote42 Similar to prints produced elsewhere in the world using the same processes at the time, the prints in Ilanga Lase Natal were monochromatic, lacking colour and vibrancy. For Mokoena, the black-and-white images deny the reader the ‘colourful milieu in which African men and women dressed for the success they were denied by the colonial culture’.Footnote43 But perhaps more critically, the inability to fully capture colour in these early prints necessitated that the artist accentuate the distinct facial features of individuals so that their Africanness would be identifiable. This is not surprising considering that the target market for these products was primarily African. To achieve this likeness, the person who illustrated these faces required the advanced drawing and observation skills that were being cultivated by Mr Ncamu in the printing section of the Ohlange Institute. Ultimately, while these newspaper-based printmakers operated outside the field of art, and their work could hence not be appreciated as bespoke creations attributable to an individual artist, they were nevertheless producing unique visuals with an artistic idiom.

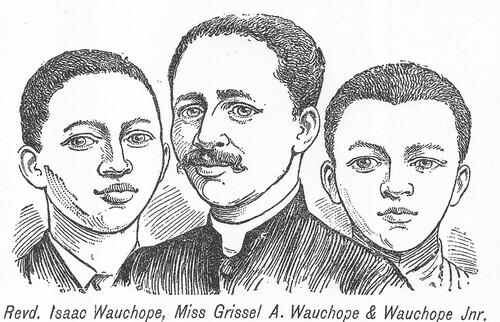

Rev. Isaac Wauchope, Miss Grissel A. Wauchope & Wauchope Jnr. (Advert for Dr Williams Pills), engraving for newspaper, ‘Wapiliswa emva kweminyaka e isitupa’, Ilanga Lase Natal, 14 April 1905, p 3

While I am primarily interested in the artistic qualities of these prints, it is also necessary to consider the broader symbolic meaning of the images and the individuals captured in them. To borrow from Mokoena once more, to understand the significance of these images it is imperative to appreciate that ‘the printed page was also a storehouse of the class aspirations of the men and women who subscribed to newspapers and who were the lifeblood of the black press’.Footnote44 Thus, the selection of clergymen, chiefs, teachers and other persons of higher social standing as faces for these Western medicines conformed both to the belief that the white man’s medicine was more effective in curing certain ailments, and to the idea that in order to belong in the new social order it was important to use foreign medicines. It is also necessary to acknowledge that the presence of women in these images is, at best, peripheral: of the New African gentry who were used as models during the period 1903–1905, only two were women, Chief Moloto’s wife (who appears in the family group discussed earlier) and Miss Grisell A Wauchope, daughter of the Reverend Isaac Wauchope, the writer, politician and pastor who drowned aboard the SS Mendi when it sunk in 1917.Footnote45 The absence of prominent women in the emergent class of Western-educated African intellectuals was consistent with the marginal standing of Black women throughout the African social value chain, both at the time and for the remainder of the twentieth century.

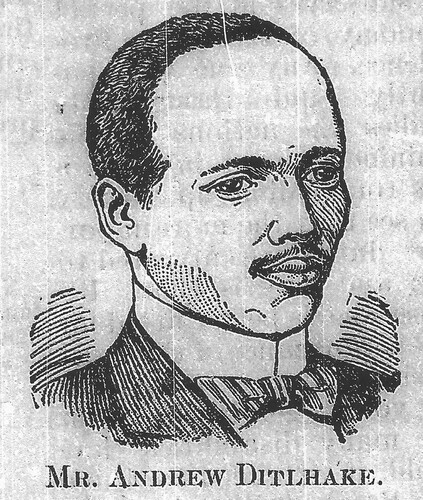

Mr Andrew Ditlhake (Advert for Dr Williams Pills), engraving for newspaper, ‘Wangenwa ufuba’, Ilanga Lase Natal, 13 May 1904, p 3

Despite excluding women, the success of these image and text adverts was ‘their capacity for speaking to the readers directly in a register of interpellations that were both familiar and novel’.Footnote46 For example, the image of Andrew Ditlhake, which appeared in a 1904 advert for Dr Williams’ Pills, reveals the artistic impulses of the printmaker, who translated this image from photograph to print while simultaneously communicating his social positionality. Ditlhake is cited as being from Marabastad, in Pretoria, and is presented as sophisticated and urban-based, dressed in a suit, collar shirt and bow tie. Referencing the selling of luxury items like watches in Ilanga Lase Natal, Mokoena further reveals how the ‘advertisers and sellers tended to undermine the colonial assumption that Africans were ignorant of the function, value, and aesthetics of especially luxury goods by presenting the African consumer as a discerning customer’.Footnote47 Likewise, the types of images created for Dr Williams’ and Doan pills were engaging the Black consumer in non-paternalistic terms. In his analysis of the advertising practices of Western medicinal products in China during the early twentieth century, Huang explains that the ‘medicine sellers also felt it necessary to explain to Chinese consumers Western concepts about how their products worked. Thus, new knowledge about the kidneys, the blood and the brain were introduced to the Chinese audience’.Footnote48 The same is true of Ilanga Lase Natal, wherein discerning African consumers were educated about the complexities of human organs and how the pills assisted in curing specific ailments.

Conclusion

I have sought to show how the establishment of the Black press in South Africa during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries enabled printmaking to come into being as a creative endeavour among Black people. On account of their ‘multi-purpose nature’,Footnote49 the ubiquitous newspapers of the early Black press should be appreciated as foldable and compact gallery walls that were seen by both literate and illiterate Black consumer audiences. The engravings of the educated, Christianised and, most importantly, urbanised neo-African appeared in almost every edition of Ilanga Lase Natal between 1903 and 1905. More striking is how the production of images was in part financed and facilitated by multinational colonial enterprises that paid for the advertising spaces wherein they appeared. But as Mokoena prompts, ‘This then raises questions about what the relationship between consumption and consciousness is, especially in the case of Black press newspapers where the invitation to consume sat side by side with the invitation to readers to constitute themselves as a community or class.’Footnote50 The images of satisfied Black clients who had used the various medicines being advertised must be appreciated as part of a larger continuum of social change that was taking shape, which was inextricably linked to the colonial encounter. A glaring failure of these images is their patriarchal drift. Apart from two images where the wives of the two male figures are depicted, there were limited visualisations of women in the adverts for both Dr Williams and Doan pills. This is extremely curious since elsewhere in the world where the same products were marketed the ‘target consumer was mainly female’.Footnote51 While women were certainly consuming the pills in South Africa, their omission and non-representation in Ilanga Lase Natal as satisfied customers who had also used these products is undeniably worrisome.

It is my conviction that these compelling pictures were most probably produced by a Black master printmaker or team of printmakers within the various Black-operated presses. The substantive circumstantial evidence presented in this introductory reading shows that Black printmakers existed and flourished within the Black press publishing domain during the early 1900s. Unfortunately, rapid advancements in the mass reproduction of photographic images within the newspaper publishing industry in the years that followed rendered the antiquated printing processes used by these early Black printmakers obsolete, and this resulted in the disappearance of their artistic legacy as the earliest Black printmakers.

The petition for polyphonic art histories in this special issue is an opening to expand art-historical practice beyond the limits of existing taxonomies and linear chronologies that pretend to be gospel narratives. Thus, using whatever arsenal of research methodologies, it is my hope that new and yet unrecorded histories of South African printmaking among Black artists that predate and overlap mid-twentieth-century schools, such as Rorke’s Drift and Polly Street, will emerge. These prints need to be analysed alongside the much larger body of images from the early twentieth century that showcase a changing and increasingly urbanised Black subjectivity.Footnote52

Notes

1 Lize van Robbroeck suggests that it is more instructive to talk of plural South African art histories as opposed to a singular and often myopic history of South African art, and thus I refer to printmaking histories instead of a history of printmaking. Lize van Robbroeck, ‘Unsettling the Canon: Some Thoughts on the Design of Visual Century: South African Art in Context’, Third Text Africa, vol 3, no 1, 2013, pp 27–29.

2 Philippa Hobbs and Elizabeth Rankin, Printmaking in a Transforming South Africa, David Philip, Cape Town, 1997; Philippa Hobbs and Elizabeth Rankin, Rorke’s Drift: Empowering Prints, Double Storey, Cape Town, 2003; Juliet Leeb-du Toit, Ndaleni Art School: A Retrospective, Tatham Art Gallery, Pietermaritzburg, 1999; Elza Miles, Polly Street: The Story of an Art Centre, Ampersand Foundation, Johannesburg, 2004; Judy Seidman, Red on Black: The Story of the South African Poster Movement, STE Publishers, Johannesburg, 2007; Judith Hecker, Impressions from South Africa: 1965 to Now, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2011; Gavin Jantjes, Jillian Carman, Lize van Robbroeck, Mandisi Majavu, Mario Pissarra and Thembinkosi Goniwe, eds, Visual Century: South African Art in Context 1907–2007, vols 1–4, Wits University Press, Johannesburg, 2011

3 I am persuaded to call the timelines presented by these authors ‘gospel-like’ chronologies because of the encyclopaedic nature of their works. The texts are well-written, thorough and almost impenetrable fortresses of knowledge, which art educators like myself appreciate and ultimately depend on as reference material to facilitate learning and teaching. This makes it difficult to present alternate histories, which are at odds with such methologically sound taxonomies.

4 Hlonipha Mokoena evokes the polyphonies of fashion, advertisements, music, art, etc, to synthesise the complexities and contradictions of colonial-era modern black histories. Hlonipha Mokoena, ‘… if Black girls had long hair’, Image & Text 29, 2017, pp 112–129; Hlonipha Mokoena, ‘African Utopianism: The Invention of Africa in Diesel’s The Daily African – A Retrogressive Reading’, in Mehita Iqani and Simidele Dosekun, eds, African Luxury: Aesthetics and Politics, Intellect, Bristol, 2020, pp 37–56.

5 Fred S Kleiner, Gardner’s Art Through the Ages: A Global History, 16th edion, Wadsworth/Cengage Learning, Boston, 2020

6 I am thankful to my colleague Refiloe Lepere, lecturer in the Department of Performing Arts at the Tshwane University of Technology, who, during one of those unplanned conversations in a campus hallway, awakened me to the ‘tyranny of chronology’, as she terms it. She argues that scholars often fall prey to retelling Africa’s creative histories using Westernised rubrics like the linear timeline. While I agree with Lepere, here I use chronology as a redemptive strategy to tell a counter-history of black artistic histories that remain hidden.

7 Benjamin Gillespie and Bess Rowen, ‘Against Chronology: Intergenerational Pedagogical Approaches to Queer Theatre and Performance Histories’, Theatre Topics, vol 30, no 2, 2020, p 69

8 The South African National Library has two branches, one in Cape Town (established 1818) and another in Pretoria (established 1887).

9 Les Switzer and Donna Switzer, The Black Press in South Africa and Lesotho: A Descriptive Bibliographic Guide to African, Coloured and Indian Newspapers, Newsletters and Magazines 1836–1976, G K Hall, Boston, 1979; Les Switzer, ed, South Africa’s Alternative Press: Voices of Protest and Resistance, 1880s–1960s, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1997

10 Tim Couzens, ‘History of the Black Press in South Africa 1836–1960’, paper presented at the University of Witwatersrand Institute for Advanced Social Research, Johannesburg, 1984

11 Ntongela Masilela, An Outline of the New African Movement in South Africa, Africa World Press, Trenton, New Jersey, 2013, p 27

12 Julia Cagé and Valeria Rueda, ‘The Long-Term Effects of the Printing Press in sub-Saharan Africa’, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, vol 8, no 3, 2016, p 97

13 Hlonipha Mokoena, ‘“The Hardness of the Times and the Dearness of All the Necessaries of Life”: Class and Consumption in Bilingual Nineteenth-Century Newspapers’, Social History, vol 45, no 4, 2020, p 456, author’s emphasis

14 Ibid, p 458

15 Rachel M Matsha, ‘Mapping an Interoceanic Landscape: Dube and Gandhi in Early 20th Century Durban, South Africa’, Journal for the Study of Religion, vol 27, no 2, 2014, p 247

16 Isabel Hofmeyr, Gandhi’s Printing Press: Experiments in Slow Reading, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2013

17 South African History Online, ‘John Langalibalele’, South African History online, 2019, https://www.sahistory.org.za/people/john-langalibalele-dube, accessed 30 November 2023

18 Nokuthela Dube was hugely influential in the development of her husband’s projects. However, as Leverne Gething laments, ‘the vital role which Nokuthela played in the formation of the school is often overlooked. Nokuthela cofounded the Ilanga Lase Natal newspaper in 1903, Ohlange Institute and Natal Native Congress with Dube—but is not mentioned at all.’ Leverne Gething, ‘Editorial: Autobiographies, Biographies and Writing Lives’, Agenda: Empowering Women for Gender Equity, vol 28, no 1, 2014, p 1.

19 South African Heritage Resources Agency, ‘Declaration of the Ohlange Heritage Site, Inanda, eThekwini, KwaZulu-Natal as a National Heritage Site’, Government Gazette, 42712, 2019, p 16

20 Zulu Christian Industrial School, Ilanga Lase Natal, 25 December 1903, p 4

21 ‘History of Periodical Illustration’, Nineteenth-Century Newspaper Analytics, North Carolina State University, 2023, https://ncna.dh.chass.ncsu.edu/imageanalytics/history.php, accessed 30 November 2023

22 See eg an article in the weekly Bantu World highlighting the need for printers in the native printing offices. ‘Printers in Demand’, Bantu World, 20 August 1932, p 2.

23 Daniel Magaziner, ‘Daniel Magaziner, Author: The Art of Life in South Africa’, SABC News, 2017, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mwhJH5LWRpM&t=2s, accessed 30 November 2023

24 Robert T Vinson and Robert Edgar, ‘Zulus Abroad: Cultural Representations and Educational Experiences of Zulus in America, 1880–1945’, Journal of Southern African Studies, vol 33, no 1, 2007, p 44

25 Iain Gately, Tobacco: A Cultural History of How an Exotic Plant Seduced Civilization, Grove Press, New York, 2001, p 223

26 Vinson and Edgar, ‘Zulus Abroad’, op cit

27 Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, open access collection, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search#!?showOnly=openAccess&offset=0&pageSize=0&sortOrder=asc&q=zulu&perPage=20&searchField=All#, accessed 18 January 2022

28 Vinson and Edgar, ‘Zulus Abroad’, op cit, p 51

29 Hlonipha Mokoena, ‘“How I Photographed Cetywayo”: Photography and the Spectacle of Exile in Colonial South Africa’, 2013, p 18, https://www.academia.edu/31121821/How_I_Photographed_Cetshwayo_Photography_and_the_Spectacle_of_Exile_in_Colonial_South_Africa, accessed 18 June 2021

30 Ntongela Masilela, ‘A New African Artist’, in Bridget Thompson, ed, In the Name of All Humanity: The African Spiritual Expression of Ernest Mancoba, Art and Ubuntu Trust, Cape Town, 2006, p 31

31 Metropolitan Museum of Art, op cit

32 Gately, Tobacco, op cit

33 Masilela, ‘A New African Artist’, op cit

34 In keeping with the individual objectives of New Africans, the shared vision of the New African movement was to facilitate the social, educational, political and economic progress of Africans beyond the yoke of colonialisation. Ntongela Masilela, The Historical Figures of the New African Movement, Africa World Press, Trenton, New Jersey, 2014.

35 Helen Bradford, ‘Class Contradictions and Class Alliances: The Social Nature of ICU Leadership, 1924–1929’, in Tom Lodge, ed, Resistance and Ideology in Settler Societies, Southern African Studies 4, Ravan Press, Johannesburg, 1986, p 50

36 Doan’s Pills, which were regarded as miracle pills and were sold by the Foster-McClellan Company, were developed by Canadian pharmacologist James Doan in the late eighteenth century. Max K W Huang, ‘Medical Advertising and Cultural Translation: The Case of Shenbao in Early Twentieth-Century China’, in Pei-yin Lin and Weipin Tsai, eds, Print, Profit, Perception: Ideas, Information and Knowledge in Chinese Societies, 1895–1949, Brill, Leiden, 2014, p 121.

37 Dr Williams’ Pink Pills were developed by Canadian doctor William Jackson, who sold the rights of the Pink Pills for Pale People to G T Fulford & Co in 1890.

38 ‘About George T Fulford’, Ontario Heritage Trust, 2022, https://www.heritagetrust.on.ca/en/properties/fulford-place/history/the-people, accessed 18 February 2022

39 Huang, ‘Medical Advertising’, op cit, p 121

40 Ibid, p 146

41 ‘History of Periodical Illustration’, op cit

42 Ibid

43 Mokoena, ‘The Hardness of the Times’, op cit, p 462

44 Ibid, p 457

45 South African History Online, ‘Isaac Williams Wauchope’, South African History Online, 2019, https://www.sahistory.org.za/people/isaac-williams-wauchope, accessed 30 September 2023

46 Ibid

47 Mokoena, ‘The Hardness of the Times’, op cit, p 460

48 Huang, ‘Medical Advertising’, op cit, p 146

49 Mokoena, ‘The Hardness of the Times’, op cit, p 456

50 Ibid, p 475

51 Huang, ‘Medical Advertising’, op cit, p 136

52 The amazing book of photographs from the period put together by Santu Mofokeng comes to mind here. Black Photo Album / Look at Me: 1890–1950 (Steidl Verlag, Göttingen, 2013) catalogued the carefully choreographed studio pictures taken by middle-class urban-based black families and individuals during the late nineteenth and first half of the twentieth centuries. The existence of such photos is not surprising, especially because many adverts appeared in black newspapers like Ilanga Lase Natal in the 1900s inviting urban families to take studio photographs.