Abstract

In recent decades, supply chains have become a critical source of competitive advantage. Yet, in the Germany automotive industry, supply chains have turned out to be untransparent and prone to sustainability breaches, with the recent Volkswagen manipulation scandal exemplifying the financial and reputational consequences. Many firms today, therefore, focus on what is called sustainable supply chain management (SSCM). While drivers, barriers, and performance implications of SSCM have been widely explored, little is known about its implementation process. Building on the foundations of organisational change, this study inductively analysed 54 sustainability reports from three German automotive triads between 2014 and 2019. Our results led to an SSCM implementation framework that sequentially employed the nine most prominent implementation stages and related change measures. The framework expands our knowledge on the SSCM implementation process; furthermore, it serves as an example for industry experts aiming to turn their supply chains into sponsors for sustainability.

1. Introduction

Numerous firms have sought to sustain their competitive advantage by establishing efficient, globe-spanning supply chains (Mol Citation2003). On financial grounds, those supply chains seem to have proven most of the firms correct (Skjott-Larsen et al. Citation2007). From a sustainability point of view, however, many global supply chains have turned out to be untransparent and prone to potential sustainability breaches (Hofmann et al. Citation2014). Those breaches in its own right already justify the reconsideration of prevailing supply chain practices. Moreover, they can significantly harm a firm’s reputation and performance (Hoejmose, Roehrich, and Grosvold Citation2014).

The German automotive manipulation scandal serves as a prime example of the potentially severe impact of such sustainability breaches. Starting in 2014, emissions tests conducted by the International Council of Clean Transportation (ICCT) revealed discrepancies in the emissions values of Volkswagen’s car models. Further investigations convicted the firm and its suppliers of the deliberate installation of illegal manipulation software. Triggered by these disclosures, the Volkswagen AG stock lost 40% of its value within only two weeks. Customers, law enforcement authorities, and government representatives alike demanded clarification of all legal infringements and financial compensation for those affected (Jung and Sharon Citation2019). In total, Volkswagen incurred estimated costs of 32 billion euros (Menzel Citation2020). With other automotive firms too being subject to federal investigations, not only Volkswagen but the German car industry as a whole had to cope with a substantial loss of both customer and shareholder trust (Jung and Sharon Citation2019).

Several structural changes in the German automotive industry during the last decades seemed to have paved the way for this scandal. The exploration and integration of new markets and segments allowed for substantial revenue growth, but consequently increased competitive pressures (Thun and Hoenig Citation2011); hence, cost-efficiency became a guiding mantra (Lee Citation2004). To cope with rising cost pressures, German automotive firms outsourced large parts of their production and R&D activities to upstream suppliers (Jüttner, Peck, and Christopher Citation2003). Manufacturing plants were relocated to low-cost countries and cost-efficient procedures, such as just-in-time production, became the new industry standard (Svensson Citation2004; Thun and Hoenig Citation2011). Though increasing the supply chain’s efficiency, the achieved cost advantages did come at a price.

The ongoing relocation and restructuring of supply led to the development of complex and untransparent supply chains (Christopher and Holweg Citation2011). The industry faced a precarious paradox: while focal firms became increasingly reliant on their supply network, they possessed less knowledge about their upstream processes than ever before (Steven, Dong, and Corsi Citation2014). New and unforeseen ecological and social risks arose. As a result, German automotive supply chains became more vulnerable and thus prone to sustainability breaches (Thun and Hoenig Citation2011; Hofmann et al. Citation2014).

Shaken by the emission scandal and its severe consequences, German automotive firms increased their efforts to address this vulnerability, i.e. to implement what is called sustainable supply chain management (SSCM). According to Dubey et al. (Citation2017), SSCM can be understood as a focal firm’s management of its supply chain’s operations by integrating economic, environmental, and social issues. As such, SSCM constitutes a powerful tool to pro-actively address upstream sustainability issues and to meet the rising demands of external stakeholder groups (e.g. regulators, customers, or NGOs) (Dubey et al. Citation2017). Unfortunately, SSCM implementation is anything but an easy task posing several challenges for a firm. As emphasised by Benn, Edwards, and Williams (Citation2014), the most striking challenge is the need for an established organisation to dismantle existing structures and to undergo a fundamental organisational change – both in mind and action.

Irrespective of this major challenge, research shedding light on the SSCM implementation processes remains scarce (Turker and Altuntas Citation2014; Huq, Chowdhury, and Klassen Citation2016). Numerous studies instead emphasised the relationship between SSCM implementation and supply chain performance. Although still lacking a general consensus, many have recognised a positive relationship between SSCM practices and both environmental (Tappia et al. Citation2015; Esfahbodi, Zhang, and Watson Citation2016; Kumar et al. Citation2019) and financial performance (Golicic and Smith Citation2013; Savino, Manzini, and Mazza Citation2015; Gopal and Thakkar Citation2016b). With this in mind, other studies examined the barriers and drivers of implementing sustainable practices within a supply chain. Respective works showed that, for example, budget, coordination, and communication problems can hinder a firm’s SSCM efforts (Carter and Dresner Citation2001; Sajjad, Eweje, and Tappin Citation2015; Ghadge et al. Citation2020). By contrast, regulations, customer expectations, other stakeholder demands, and performance improvements can be guiding motives for SSCM implementation (Dubey et al. Citation2015; Mann et al. Citation2010). Notwithstanding these important insights, it remains unclear which SSCM practices are needed to respond to these driving forces or overcome the identified barriers, respectively. Though, few works provided individual testimonies of feasible measures (e.g. Dubey et al. Citation2017; Zimon, Tyan, and Sroufe Citation2019; Shibin et al. Citation2020), the configuration of SSCM implementation as a process of organisational change remains unclear (see Gopal and Thakkar Citation2016a for one exception). Touboulic and Walker (Citation2015) thus encouraged researchers to ‘develop our understanding of the implementation process of SSCM by framing it as change (…) in organizational practice’ (35).

As a direct response to their call, our study utilises the theoretical foundations of organisational change to identify the steps and sequence of the SSCM implementation process in the German automotive industry. We chose this study context, as global automotive supply chains are seen to be less responsive, integrated, and visible compared to other sectors (e.g. consumer goods or pharmaceutical industry) (Shibin et al. Citation2020). This very well applies to the German automotive industry, which is further characterised by complex supply networks (Christopher and Holweg Citation2011), high dependence on upstream supply chain entities (Steven, Dong, and Corsi Citation2014), highly formalised buyer-suppliers relationships (Durach and Wiengarten Citation2017), and, finally, extensive external sustainability pressures triggered by the emission scandal in 2014 (Jung and Sharon Citation2019). With all these characteristics demanding the implementation of SSCM, the German automotive sector serves as the perfect setting for our investigation. Focussing on this industry, we pose the following research questions:

What are the individual actions taken by German automotive firms to implement SSCM within their supply chains over time?

Which chronological sequence characterises the change process of SSCM implementation in German automotive supply chains?

In our effort to answer these questions, we collected and analysed a longitudinal set of sustainability reports (2014–2019) taken from three supply chain triads in the German automotive sector. Overall, 54 reports were examined to identify SSCM implementation measures and their chronological sequence. Building on the foundations of organisational change, we proposed an SSCM implementation framework that informs researchers and managers alike. Our findings advance our existing knowledge on the SSCM implementation process; thereby, confirming previous studies and pointing at to date under-explored aspects of SSCM implementation. Furthermore, the framework and its underlying measures together serve as an example for industry experts on how to turn their own supply chains into sponsors for sustainability.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. We first introduce the theoretical foundations of organisational change and provide a short overview of related SSCM literature. Afterwards, we describe the applied sampling and analytical approach in more detail. The following section then highlights both our main findings and the resulting SSCM implementation framework. Our results and directions for future research are briefly discussed thereafter. Finally, the article closes with a short conclusion and the study’s limitations.

2. Literature review

2.1. Theoretical foundations of organisational change

Organisational change can be understood as a dynamic process by which an organisation adapts established strategies, technologies, procedures, resources, structures, or cultures to improve its competitive situation or even secure its very survival (Senior and Fleming Citation2006). It is often triggered by pressures arising from the external environment (e.g. coercive, normative, or mimetic pressures [Dubey et al. Citation2017]); yet, the stimulus for change can also originate from within an organisation (Saeed and Kersten Citation2019). In either case, organisational change requires a firm to replace outdated procedures and explore new grounds, which often yields immense resistance among those affected (Benn, Edwards, and Williams Citation2014). To resolve such inertia, the coordination of various interlinked entities and processes is needed; thereby, posing a complex managerial challenge for most organisations (Lewis and Sahay Citation2019).

Change management (CM) thus became an increasingly important area of interest for practitioners and scientists alike. It refers to the management of all actions taken by an organisation to facilitate a desired change, just as its underlying drivers and implications (Cameron and Green Citation2019). Today, the discipline accounts for a wide and growing body of academic research (Schwarz Citation2012). Respective studies have examined, inter alia, the drivers and barriers of change (Král and Králová Citation2016; Kiesnere and Baumgartner Citation2019), the capabilities needed to conduct change (Battilana et al. Citation2010; Wenzel, Danner-Schröder, and Spee Citation2020), or the consecutive phases of change processes (Dixon, Meyer, and Day Citation2010). Interestingly, most contributions to this discipline are still deeply-rooted in a rather limited number of classic change models, which even today determine our understanding of CM (By Citation2005).

One of the most influential change models in management theory was introduced by Lewin (Citation1947). He subdivided a change process into three consecutive phases: (1) ‘un-freeze’, (2) ‘change’, and (3) ‘re-freeze’ (Burke Citation2017). During the ‘un-freeze’ phase, firms strive to prepare for the forthcoming change, reduce existing inertia, and dismantle outdated structures. In the ‘change’ phase, they gradually initiate, monitor, and evaluate the necessary adjustments; thereby, moving from the old to the new state. Finally, in the ‘re-freeze’ phase, firms aim for the newly introduced practices and values to become a substantial part of the organisation’s accepted standard procedures and company culture (Burke Citation2017; Lewis and Sahay Citation2019). Only if all three phases have been performed with due care, the desired organisational change (i.e. the implementation of SSCM) can be performed and sustained successfully (Burke Citation2017).

2.2. SSCM implementation as a process of organisational change

Notwithstanding the growing number of SSCM publications (Carter et al. Citation2019), our current knowledge on SSCM implementation as a process of organisational change remains shallow (Touboulic and Walker Citation2015; Huq, Chowdhury, and Klassen Citation2016); however, building on Lewin’s (Citation1947) change model, one can identify several studies that provided examples for individual CM efforts taken in firms to prepare, execute, and stabilise sustainable supply chain practices (Benn, Edwards, and Williams Citation2014). Turker and Altuntas (Citation2014), for instance, found that firms often relied on the formulation of a ‘Code of Conduct’ to specify their sustainability demands as well as on supplier monitoring or auditing activities when accessing their SSCM progress (see also Villena and Gioia [Citation2018] or Zimon, Tyan, and Sroufe [Citation2019]). Other studies emphasised the utilisation of environmental certifications (Zhu, Tian, and Sarkis Citation2012), the integration of sustainability issues in a firm’s supply chain strategy (Wu and Pagell Citation2011; Macchion et al. Citation2018; Hou, Wang, and Xin Citation2019; Laosirihongthong et al. Citation2020), or the necessity of supplier sustainability risk assessments (Wu, Dunn, and Forman Citation2012; Hadiguna and Tjahjono Citation2017; Xu et al. Citation2019). Pointing specifically towards the lack of visibility in upstream supply chains, Dubey et al. (Citation2017) and Shibin et al. (Citation2020) outlined the central role of information sharing and connectivity between supply chain entities to facilitate SSCM. Finally, efforts taken to develop a committed and trained workforce have been identified as valuable levers for sustainable supply chains (Shibin et al. Citation2018; Brix-Asala and Seuring Citation2020). Viewed in isolation, each of these CM measures may benefit SSCM implementation; yet, they do not fully capture the overall change process as defined by Lewin (Citation1947) and its chronological sequence.

A first contribution to address this gap was provided by Gopal and Thakkar (Citation2016a), who aimed to identify the critical success factors (CSFs) relevant for SSCM implementation (see Luthra, Dixit, and Abid Citation2015; Luthra et al. Citation2018 for other investigations of CSF). Conducting a detailed case study in the Indian automotive sector, the authors identified 25 CSFs. While discussing their major findings, they briefly introduced a short five-step roadmap. This roadmap not only named relevant SSCM implementation steps (e.g. supplier assessments, capacity building programs), but also indicated their logical sequence (Gopal and Thakkar Citation2016a). Yet, despite the insights of their pioneering work, the authors set a clear focus on the CSFs of SSCM implementation, but did not fully explore the actions taken by the firms to exploit them. The roadmap itself thus remained at a rather high level and also did not cover all aspects of an organisational change process; hence, it left further need and potential for both a deeper and broader understanding of the SSCM implementation process. To the best of our knowledge, no other study to date has addressed these shortcomings. In the following, we will thus describe our steps taken to further examine the SSCM implementation process.

3. Methods

3.1. Sample selection

Numerous studies agreed that a firm’s efforts to implement SSCM are often driven by external pressures (Dubey et al. Citation2017; Zimon, Tyan, and Sroufe Citation2020). As for the German automotive sector, two outside forces are of particular importance: (1) strict emissions regimes introduced by governmental institutions and (2) rising customer expectations regarding sustainable mobility (Thun and Müller Citation2010). While emissions regimes rather affect all national industry players equally, the pressures caused by end-customers can vary significantly for different automotive firms. In fact, Green, Toms, and Clark (Citation2015) found that market-oriented firms possessed a stronger recognition of the end-customers’ needs, which again facilitated the establishment of sustainable practices. Put differently, the extent and nature of the SSCM measures taken by a firm might vary according to its proximity to the end-customer; thus, a multi-tier perspective is needed to fully investigate the SSCM implementation measures present in German automotive supply chains.

For this purpose, we decided to analyse triadic supply relationships – also referred to as ‘triads’ (Choi and Wu Citation2009). A triad does not simply conceptualise a supply chain as the dyadic link between a focal firm and its supplier. Instead, it incorporates three connected entities; thereby, acknowledging the interdependencies between individual supply chain members (Madhavan, Gnyawali, and He Citation2004). As a result, triads form a more realistic picture of today’s complex supply chains and facilitate new insights that supplement dyadic observations (Wu, Choi, and Rungtusanatham Citation2010). In our specific study setting, the (buyer–supplier–sub-supplier) triad enabled the identification of SSCM measures used at different levels of a supply chain (see Grimm, Hofstetter, and Sarkis [Citation2014] or Wilhelm et al. [Citation2016] for other studies on triads). In our effort to construct such triads, a two-phase purposeful sampling approach was applied.

3.1.1. First sampling round – selecting a focal firm

During the first sampling round, we aimed to identify a focal firm that served as the head of the triad. Here, our selection relied on two main criteria.

First, the focal firm was required to abide by the reporting guidelines of the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), which provides a well-established framework on how firms should assess and report their sustainability efforts (Turker and Altuntas Citation2014). The basic guidelines specify a set of material sustainability indicators, which reporting firms must disclose; moreover, few GRI sections specifically focus on supply chain-related sustainability issues (e.g. GRI 204, 308, and 414) (Global Reporting Initiative Citation2020).

Second, we required a focal automotive firm to currently operate as an industry leader in reporting its sustainability efforts; thereby, indicating a significant progress being made since the emissions scandals shattered the industry in 2014 (Jung and Sharon Citation2019). Our selection relied on the 2018 CSR report ranking of the German Institute for Ecological Economy Research (IÖW) (Dietsche, Lautermann, and Westermann Citation2019). Based on 44 indicators (26 for small and medium-sized enterprises [SME]), the systematic ranking considered both material and formal criteria for assessing the quality of a firm’s sustainability reporting, while simultaneously accounting for economic, ecological, and social issues.

3.1.2. Second sampling round – selecting upstream suppliers

Having selected a focal firm, the second sampling round served to identify associated upstream suppliers that would allow for the construction of supply chain triads. For this purpose, we selected a first- and a second-tier supplier that each were sequentially connected to the chosen focal firm.

To identify a potential first-tier supplier, we used the Bloomberg supply chain algorithm (referred to as SPLC), which has recently been applied in other SCM studies (see Elking et al. [Citation2017] or Wetzel and Hofmann [Citation2019] for studies applying the SPLC function). The algorithm quantifies supplier relationships based on various data sources, such as financial, end market channel, or product-level data. The relationships are graphically illustrated, listed, and ranked according to different KPIs (e.g. purchasing volume, revenue share, cost of goods sold) (Wetzel and Hofmann Citation2019). For our study, we focussed on the focal firm’s ten most important first-tier suppliers (as measured by purchasing volume). Given their size and strategic importance, they were expected to more likely serve as a feasible disseminator of the focal firm’s SSCM requirements (Wilhelm et al. Citation2016). From this subset, we then selected one first-tier supplier that was headquartered in Germany and had recently published GRI-compliant sustainability reports.

Finally, the SPLC function was employed once more to select a second-tier supplier for the focal firm. Doing so, we simply repeated the above-described process; yet, this time the selection was made from the ten most important suppliers of the already-chosen first-tier supplier. While choosing a suitable firm, we made sure that the chosen second-tier supplier did not overlap with the top ten first-tier suppliers of the respective focal firm.

3.1.3. Final study sample of German automotive supply chains

Following the described two-phase sampling process, we formed a first supply chain triad. For each firm included in the triad, we retrieved and analysed all available GRI sustainability reports published during and after the emission manipulation scandal (2014–2019). Unavailable GRI sustainability reports were compensated for by the analysis of alternative sustainability reports or the corresponding sections of a firm’s annual report. Being our primary data source, the sustainability reports were in most cases easily accessible (via GRI database or firm website), provided vast information on the SSCM aspects addressed by the firms, and enabled a longitudinal analysis that was required for investigating an organisational change process over time (see Turker and Altuntas [Citation2014], Rossi and Tarquinio [Citation2017], or Torelli, Balluchi, and Furlotti [Citation2020] for other studies conducting a longitudinal analysis based on sustainability reports). Having analysed the first triad, two additional supply chain cases extended our analysis until it reached the point of theoretical saturation (Silverman Citation2020).

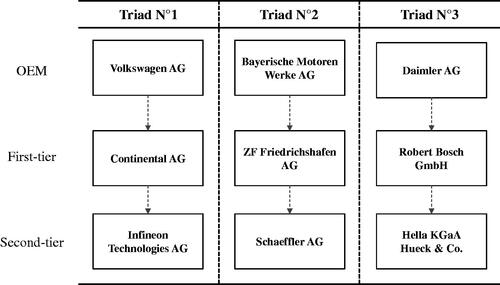

In summary, the overall sample was made up of three supply chain triads, comprising nine German automotive firms (see ) and a longitudinal data set of 54 reports in total. Our sample included almost all major automotive OEMs (with Audi AG and Porsche AG applying the Volkswagen group sustainability standards; Volkswagen Citation2020) and the five largest automotive suppliers in Germany (Puls and Fritsch Citation2020); thereby, forming an acceptable representation of the German automotive industry for our qualitative research design.

3.2. Data analysis

To analyse the selected sustainability reports, we conducted a ‘Content analysis’. The term summarises different types of analysis used in the field of inductive research to examine documents or communication artefacts. It lends itself to analyse and interpret the meaning of a text; thereby, enabling the identification of recurring concepts (Silverman Citation2020). Numerous studies have applied different content analysis approaches to examine sustainability reports (e.g. Campopiano and de Massis Citation2015; Lock and Seele Citation2016; or Landrum and Ohsowski Citation2018). A comparably new methodology of content analysis is the approach described by Gioia, Corley, and Hamilton (Citation2013). It provides clear guidance for systematically analysing and presenting the collected data, while balancing the issues of relevance and rigour for qualitative research. The approach further recommends the consideration of established theoretical knowledge to facilitate new concept generation (Gehman et al. Citation2018). This enabled the incorporation of the previously described foundations of organisational change. It thus perfectly matched our research design and hence was chosen as the guiding approach for our data analysis.

The analysis started with the identification and labelling of all SSCM-related statements found in the selected reports. For this purpose, we conducted two rounds of analysis, each supported by MAXQDA software. During the first reading, we reviewed every report independently; thereby, codes were inductively developed and assigned to each of the identified text passages. During the second reading, we verified the assigned codes by comparing the different reports with one another. This ensured that uniform quotations were labelled with the same code. Resulting from our ongoing code refinement through both the individual report and cross-case analysis, a set of 42 first-order concepts was developed.

In the next analytical step, we identified similarities and differences between the first-order concepts. For this purpose, we continuously cycled between the identified SSCM-related statements, our preliminary categorisation, and the existing SSCM and organisational change literature. Throughout this process, we focussed on sorting those quotations that either revealed the application of individual CM practices or supply chain-specific elements of the overall change process. Respective first-order concepts were grouped accordingly, leading to the further refinement of our initial categorisation. As a result, we reduced the number of concepts to a set of 20 second-order themes.

Finally, we conducted another analysis round to further consolidate our list of second-order themes: This final compression resulted in nine aggregate dimensions, which served to display the most striking regularities found within the sustainability report data (see Gioia and Chittipeddi Citation1991; Gioia, Corley, and Hamilton Citation2013 for additional information on the analysis approach).

To verify the rigour of our approach, the above illustrated process was subsequently checked by an independent, third coder. Adopting the same methodology, the researcher autonomously reproduced the whole analysis based on a randomised sample of 14 sustainability reports (∼25% of the overall sample). Three face-to-face meetings were held to compare the independent researcher’s results with the initial categorisation developed by the authors. During these meetings, the identified quotations in each report, the assigned first-order concepts, and their latter consolidation were discussed. As a result, seven first-order concepts were being added. The formulated second-order categories and aggregate dimensions were adapted accordingly until a full common understanding was achieved. An overview of the overall coding process is provided in .

Table 1. Overview of the data coding process.

4. Results

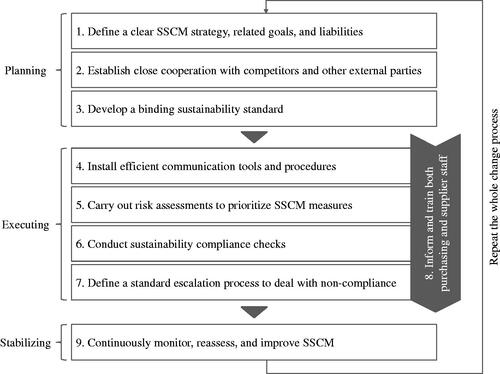

Our inductive analysis led to the identification of nine distinct SSCM implementation measures. Based on our time series data, these measures were categorised according to their appearance over time. Whereas some measures were already reported in the first periods under review (marking the start of the change process), others initially occurred in more recently published sustainability reports (representing later steps of the performed organisational change). Referring to Lewin’s model of change (1947), we summarised early-stage measures in a planning phase, intermediate measures in an executing phase, and late-stage measures in a stabilising phase, respectively. From this categorisation a three-phase SSCM implementation framework was developed (see ).

4.1. First phase: ‘planning’

The ‘planning’ phase focussed exclusively on early-stage measures, which served to prepare for the forthcoming change. Its goal was to dismantle the existing organisational structures, routines, and beliefs and to reduce any prevailing inertia that could possibly hamper the impending change process (Burke Citation2017). The planning phase consisted of the following three steps: (1) define a clear SSCM strategy, related goals, and liabilities; (2) establish close cooperation with competitors and other external parties; and (3) develop a binding sustainability standard.

4.1.1. Define a clear SSCM strategy, related goals, and liabilities

The development of a clear strategy, related goals, and liabilities constituted the very first step of SSCM implementation. Within our sample, two different strategic approaches were applied. Some automotive firms introduced an SSCM-specific strategy (e.g. the ‘Advanced Procurement Strategy (APS25)’ developed by ZF Friedrichshafen [Citation2015, 25]), which defined the firms’ SSCM vision and schedule until 2025. Other automotive firms formulated a more general sustainability strategy, which was not limited to supply chain-related issues, but treated SSCM as an integrated part of the firm’s overall sustainability efforts. In either case, the SSCM strategies provided the basis for quantifiable and time bound goals; for instance, Bosch (Citation2015) aimed to conduct 1,000 sustainability-cheques by 2020, and Daimler (Citation2016) required 70% of their suppliers to provide environmental certificates by 2018. Those strategic goals were then linked with clear responsibilities. Representatives of already existing departments (e.g. purchasing, corporate communication) and newly established institutions (e.g. sustainability committees, supply chain response teams) were held accountable for the achievement of the defined strategic goals.

4.1.2. Establish close cooperation with competitors and other external parties

Establishing close cooperation with competitors and other external parties constituted the second step of the SSCM implementation process. In general, automotive firms cooperated with three different interest groups: (1) the focal firm’s suppliers, (2) external stakeholder groups, and (3) competitors. While cooperation with suppliers and external stakeholders is a common pattern in SSCM (Rodríguez, Giménez, and Arenas Citation2016; Vachon and Klassen Citation2008), the concept of competitor cooperation remains largely neglected (Chen et al. Citation2017). Often referred to as coopetition (Wu and Choi Citation2005), the phenomenon describes behavioural actions taken by two or more firms that compete and cooperate simultaneously (Wu, Choi, and Rungtusanatham Citation2010). In fact, all automotive companies were constantly engaged in geographically distinct industry associations, such as the German Association of the Automotive Industry (VDA) or the American Automotive Industry Action Group (AIAG) (Daimler Citation2016). Competitors also cooperated in even broader initiatives, such as the CDP Supply Chain Program or the Aluminium Stewardship Initiative (ASI) (BMW Citation2015). The engagement brought into these different associations served one central purpose, namely standardisation. This included the development of consistent minimum sustainability requirements, related certifications, supplier questionnaires, and other best-practice procedures.

4.1.3. Develop a binding sustainability standard

Developing a binding sustainability standard constituted the third step of the SSCM implementation process. All automotive firms defined minimum sustainability requirements for their suppliers, which were usually laid down in one comprehensive standard. This standard formed the basis for all further SSCM evaluation and implementation efforts and referred to all three sustainability dimensions; for instance, the Volkswagen group aimed ‘to minimize or prevent negative social, environmental and financial impacts’ (Volkswagen Citation2015, 42) along the supply chain. The BMW Group Supplier Sustainability Standards likewise addressed the financial stability of suppliers, while simultaneously demanding the recognition of human rights and sound environmental, labour, and social policies (BMW Citation2015). Overall, a striking conformity regarding the standards’ scope was observed, which might be attributable to the widespread adaption of internationally recognised regimes and certifications. Indeed, most of the reviewed firms based their sustainability requirements on principles developed by institutions such as the International Labour Organisation (ILO) or the United Nations Global Compact (Volkswagen Citation2015). Furthermore, they widely adapted different third party certifications to specify both their ecological (e.g. ISO 14001, EMAS certification) (Daimler Citation2016) and, to a lesser extent, social (e.g. OGHSAS 19001, SA 8000) (Volkswagen Citation2015) sustainability demands.

4.2. Second phase: ‘executing’

Having prepared for the forthcoming change, the automotive firms entered the subsequent executing phase, which included all the intermediate measures taken to perform the desired change (Lewin Citation1947). The goal of this phase was to familiarise both the internal and external affected parties with the newly introduced values, behaviours, and processes; it thus marked a transition from the old to the new state (Burke Citation2017). The executing phase consisted of the following five steps: (4) install efficient communication tools and procedures, (5) carry out risk assessments to prioritise SSCM measures, (6) conduct sustainability compliance cheques, (7) define a standard escalation process to deal with non-compliance, and (8) inform and train both purchasing and supplier staff.

4.2.1. Install efficient communication tools and procedures

Installing efficient communication tools and procedures constituted the fourth step of the SSCM implementation process. As emphasised in previous studies, communication problems represent a major SSCM barrier (Carter and Dresner Citation2001). Consequently, the information exchange between a focal firm and its suppliers played a key role in the SSCM implementation process. To facilitate communication, automotive firms fell back on specific tools and standardised procedures. The most prominent tools they used were existing supplier management platforms; for instance, Schaeffler in 2016 introduced its ‘Transport Order Management System (TOMS)’ (Schaeffler Citation2017, 29) to coordinate all SSCM-related actions and communication within their supply chain. On the one hand, those online tools served as a knowledge centre for providing detailed information to suppliers (e.g. on the sustainability schedule, requirements, and progress); on the other hand, the platforms were used as a tool to systematically collect and analyse sustainability-related supplier information. In addition, independent whistle blower hotlines were established, which enabled informants to report sustainability infringements anonymously (Daimler Citation2018). Those tools were supplemented by standard communication procedures, which included regularly held supplier development interviews, specialised workshops, or large supplier forums (Volkswagen Citation2017).

4.2.2. Carry out risk assessments to prioritise SSCM measures

Carrying out risk assessments to prioritise SSCM measures constituted the fifth step of the SSCM implementation process. Given their limited resources, the automotive firms did not address all members of their supply chain simultaneously, but instead focussed on the most relevant suppliers. Initially, some firms cooperated intensively with only a strictly limited number of so called ‘pilot suppliers’ (Continental Citation2017, 21). In doing so, they aimed to test the developed standards, tools, and processes in real-life settings before they were rolled out on a larger scale. Next, all firms particularly focussed on their direct suppliers, with the selection being further guided by sustainability risk assessments. Those assessments were used to rate the potential likelihood and impact of sustainability breaches. They relied on different assessment criteria, such as purchasing volume, region, industry, product specifications, or used (raw) materials. BMW (Citation2018), for example, developed a risk filter that accounted for region- or product-specific risks such as the employment of child/forced labour or environmental damage caused by hazardous waste. Corresponding information were drawn from the self-disclosures of suppliers, third-party information (e.g. databases, NGO reports), in-house empirical data, media screening, or on-site visits (Volkswagen Citation2017; BMW Citation2018). Based on the analysis results, whole regions, groups, suppliers, or even single production facilities were classified according to their risk profiles. Alongside, increased attention was often given to newly established direct supplier relationships. Only at a later stage did the automotive firms extend their scope further upstream sub-suppliers, again based on comprehensive risk assessments.

4.2.3. Conduct sustainability compliance cheques

Conducting sustainability compliance cheques constituted the sixth step of the SSCM implementation process. Having identified the riskiest suppliers, the automotive firms assessed their sustainability status quo. For this purpose, two mandatory criteria were introduced. First, the suppliers needed to submit a signed code of conduct (Bosch Citation2017), which included the supplier’s contractual obligation to fulfil the defined minimum sustainability requirements. Moreover, the suppliers committed to pass on and guarantee adherence to the criteria within their own upstream supply chains. Second, suppliers had to conduct a self-evaluation (Daimler Citation2018). The evaluation was based on a previously developed questionnaire that covered all the criteria relating to the sustainability standard. Each question had to be answered and supported by corresponding evidence (e.g. documents, certificates). The assessment’s results were reviewed by the focal firm and, if necessary, further inquiries were conducted to ensure the credibility of the self-evaluation. Only if both the signed code of conduct and the results of the self-assessment were submitted and confirmed adherence to the sustainability standard, the business relationship with the supplier be could established or pursued.

4.2.4. Define a standard escalation process to deal with non-compliance

Defining a standard escalation process to deal with non-compliance constituted the seventh step of the SSCM implementation process. All firms presented pre-defined resolution measures for dealing with non-compliant behaviour. Those measures differed significantly in terms of their intensity, assigned responsibilities, and dedicated time and resource efforts (Schaeffler Citation2017). First, suppliers that were accused of failing to meet binding sustainability requirements were offered the opportunity to provide a written report in response to the charges (Volkswagen 2019). In justified cases the report had to include suggestions for reasonable resolution measures. Second, if the report was rejected, the supplier and the focal firm collaborated to develop joint action plans (Daimler Citation2019). Those plans specified, in detail, which and when certain measures were needed to resolve the sustainability issues. The implementation of those measures was subsequently tracked and reviewed by the focal firm. Third, if any doubts remained, the focal firm reserved the right to further investigate the violation independently, including more intense on- and off-site sustainability audits (BMW Citation2018). These audits were conducted by specialised expert teams and without prior notification. Depending on the respective audit results, the supplier was instructed to make the necessary improvements. If a supplier still refused to undertake the required interventions, the placement of any further orders was suspended. In extreme cases, the business relationship was terminated completely (Volkswagen Citation2017).

4.2.5. Inform and train both purchasing and supplier staff

Informing and training both purchasing and supplier staff constituted the eighth step of the SSCM implementation process. For the executing phase to take full effect, the SSCM implementation measures needed to be accompanied by personnel training on the new requirements, processes, and tools. For this purpose, the automotive firms provided different trainings for both their own and their supplier’s employees. The respective trainings differed in terms of their participants, content, and technical setup. At one end, some firms aimed to reach the highest possible number of potential participants by developing standardised, self-study sustainability courses (Schaeffler Citation2017). These online courses mostly conveyed basic information about, for example, the importance of sustainability in supply chains, its fundamental principles, or the focal firm’s binding sustainability standards. At the other end, many firms conducted intense workshops for small groups, which required participants to attended in person and were held in classroom-like settings (Volkswagen Citation2019). The workshops often provided more detailed knowledge on the completion of self-assessment questionnaires, the execution of sustainability audits, or the configuration of standard escalation measures.

4.3. Third phase: ‘stabilising’

Having performed the desired change, the automotive firms moved into the final stabilising phase, consisting of the late-stage measures needed to deeply anchor the new beliefs, goals, and processes within the organisations (Lewin Citation1947). This prevented the involved parties from falling back into their old habits and challenged them to continuously question and improve the new course of action (Burke Citation2017). The stabilising phase consisted of the following one step: (8) continuously monitor, reassess, and improve SSCM.

4.3.1. Continuously monitor, reassess, and improve SSCM

Continuously monitoring, reassessing, and improving SSCM constituted the ninth step of the SSCM implementation process. Some automotive firms explicitly stated that implementing SSCM is not a finite process (e.g. Infineon Citation2020). Indeed, an ever-changing environment and a dynamic supply base force firms to continuously monitor their supply chain. Few automotive firms thus developed a structured SSCM management approach, which usually consisted of three successive steps: (1) carry out periodic risk assessments, (2) conduct frequent sustainability cheques, and (3) take corrective and improvement actions accordingly (BMW Citation2018). However, simply repeating these once established steps of the SSCM implementation process is inadequate if the change process is truly to be sustained. Not only the suppliers, but also the foundations and tools used for their assessment must be checked and improved on a regular basis (Volkswagen Citation2020). This revision includes all the previous steps; hence, the SSCM implementation process can be viewed as a recurring cycle of monitoring, reassessment, and improvement.

5. Discussion

In summary, the developed framework systematically depicts the nine most important steps taken by German automotive firms to plan, execute, and stabilise sustainable supply chain practices. Our investigation further provided numerous examples that specified individual CM measures applied by the different firms to perform each step. While few measures have already been subject to previous SSCM research and confirmed prior knowledge, others pointed at underrepresented aspects of the SSCM implementation process that need to be further explored.

Looking at the planning phase, measures such as the development of SSCM related strategies and goals (Hou, Wang, and Xin Citation2019; Zimon, Tyan, and Sroufe Citation2019) or the formulation of binding sustainability requirements (Zhu, Tian, and Sarkis Citation2012; Turker and Altuntas Citation2014) have already been addressed in previous research. The SSCM literature further offers several articles that emphasise the consideration of stakeholder groups to deal with external pressures (Graham Citation2020; Fung, Choi, and Liu Citation2020; Torelli, Balluchi, and Furlotti Citation2020). In contrast, the role of collaboration among competitors (e.g. in trade associations) has gained significantly less attention in SSCM research; yet, it has been one of the most common measures reported in our data (I. 05 and I.06). Coopetition (Brandenburger and Nalebuff Citation1996) thus might be a promising venue for SSCM implementation as it facilitates the joint development and dissemination of best-practice standard procedures within an industry. In addition, the governance structures established by firms to implement and monitor their SSCM efforts (e.g. SSCM councils or committees [I.10], quick response teams [I.11]) were reported in detail; yet, seem to be under-explored.

The framework’s executing phase seems to be comparably strong represented in current literature. Recent publications, for instance, outlined the positive impact of information sharing and connectivity among supply chain members to facilitate supply chain visibility (Dubey et al. Citation2017; Shibin et al. Citation2020); thereby demanding effective communication processes and tools. Many studies also addressed the issue of supplier risk assessments (Xu et al. Citation2019; Zimon, Tyan, and Sroufe Citation2019), the need for a well-trained and committed workforce (Wu and Pagell Citation2011; Brix-Asala and Seuring Citation2020), or the execution of regular supplier cheques (Huq, Chowdhury, and Klassen Citation2016; Gopal and Thakkar Citation2016a; Villena and Gioia Citation2018). Less attention, however, was dedicated to the countermeasures taken by firms to deal with violations of their defined sustainability standards. Within our study sample, all firms developed individual sanctions or even a systematic escalation process that clearly determined how to deal with the non-compliant behaviour of a supplier (I.43–47). Still, it remains unclear whether the formally described sanctions are factually applied and how this might influence a supplier’s perception of a focal firm’s commitment on sustainability.

Finally, the continuous monitoring of upstream supply chain entities as described in the stabilise phase has been pointed out by other studies before (Gopal and Thakkar Citation2016b; Brix-Asala and Seuring Citation2020); yet, our framework suggests that this course of action falls short if it is not complemented by the periodic verification of its underlying tools and guidelines. Silvestre (Citation2015) touches upon this topic, when he describes SSCM as ‘not [being] a destination, but a journey’ (156). We support his argumentation and advocate for SSCM being understood as an ongoing and recurring process of organisational change.

In summary, answering the call for more research on a firm’s efforts to implement SSCM (Touboulic and Walker Citation2015; Huq, Chowdhury, and Klassen Citation2016), our findings enrich the limited body of knowledge on SSCM implementation as an organisational change. Unlike previous studies, we did not further investigate the drivers or barriers of SSCM (Mann et al. Citation2010; Sajjad, Eweje, and Tappin Citation2015), but instead showed how firms have responded to and overcome them. Our SSCM implementation framework not only illustrates which, but also when certain change steps are needed. It is further complemented by a wide range of feasible real-life examples of CM measures taken by German automotive firms; thereby, confirming prior SSCM literature and pointing at to date under-explored aspects of SSCM implementation. At last, our results also serve as an example for industry experts that face the challenge to implement or retrospectively assess and improve their own organisation’s SSCM. In this regard, our framework might support executives in developing a change process that follows the basic nine steps of SSCM implementation, while allowing for the selection of individual CM measures that best fit their own organisation’s needs.

6. Conclusion

This research was motivated by the questions of what actions in which sequence were taken by German automotive firms to facilitate a substantial organisational change – the implementation of SSCM post the emission manipulation scandal. In our effort to answer these questions, we inductively analysed a longitudinal set of 54 sustainability reports from three German automotive triads between 2014 and 2019. We identified nine distinct SSCM implementations practices. Based on the theoretical foundations of organisational change, the identified practices were categorised and used to develop a three-phase SSCM implementation framework. The framework describes the steps and individual CM measures taken by the automotive firms to plan, execute, and stabilise their SSCM efforts. As such it contributes to our so far limited knowledge of the SSCM implementation process (Touboulic and Walker Citation2015) and provides an example for industry experts on how to turn their own supply chains into sponsors for sustainability.

Notwithstanding these contributions, our results are subject to some notable limitations. First, our study strictly focussed on a single sector; namely, the German automotive industry. This industry was identified as being an excellent fit four our research question. Moreover, a clear industry focus ensured the suitability and comparability of the reviewed cases (Turker and Altuntas Citation2014; Huq, Chowdhury, and Klassen Citation2016), thereby facilitating the development of the desired framework; yet, it also limited the framework’s generalisability and scope of application. We thus encourage future research to investigate the SSCM implementation process in different industrial or country contexts.

Second, we acknowledge that the information provided in the firms’ reports could have been subject to significant editor bias. As stated by Turker and Altuntas (Citation2014), ‘words might speak louder than actions’ (848). Indeed, the SSCM implementation measures described in the reports could potentially differ from what was objectively done in practice to facilitate SSCM. Although, we aimed to alleviate reporting bias by analysing GRI conform sustainability reports, a biasing effect cannot and should not be ruled out; hence, future studies should challenge our results by using a triangulation of data sources.

Third and finally, our study did not and could not provide evidence of the framework’s effectiveness. Following a purposeful sampling approach, we ensured the inclusion of German automotive firms that were considered to be sustainability leaders within their industry (Dietsche, Lautermann, and Westermann Citation2019). Still, we did not intend to provide proof of the framework’s impact on a supply chain’s financial or environmental performance; thus, future studies should examine the effect of our framework or even single SSCM measures on different performance indicators.

Acknowledgements

We thank the two anonymous reviewers whose comments helped improve and clarify this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

The authors certify that they have no affiliations with, or involvement in, any organisation or entity with financial or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Florian Wissuwa

Florian Wissuwa is a research assistant for the Chair of Supply Chain and Operations Management at ESCP Business School in Berlin, Germany. His main research interests relate to sustainability and risk management in supply chains. He received his M.Sc. in Management from the EBS Universität für Wirtschaft und Recht. Prior to his academic career, he worked as an assistant manager at KPMG Germany in the field of risk management.

Christian F. Durach

Christian F. Durach (Dr. Technische Universität Berlin) is full Professor and occupies the Chair of Supply Chain and Operations Management at ESCP Business School, Berlin Campus. His main research activities are related to supply chain risk management, digitisation, and sustainable operations. He has published several peer-reviewed journal articles (Emerald Outstanding Paper Award, 2018 – Supply Chain Management: An International Journal), is Senior Editor of the Journal of Business Logistics (Outstanding Reviewer Award, 2019), Senior Associate Editor of the International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management (Emerald Best Reviewer Award, 2017) and Editorial Board Member of the International Journal of Operations & Production Management (Emerald Best Reviewer Award, 2020). He is the academic director of all specialised master’s programs hosted by the ESCP Berlin Campus.

References

- Battilana, Julie, Mattia Gilmartin, Metin Sengul, Anne-Claire Pache, and Jeffrey A. Alexander. 2010. “Leadership Competencies for Implementing Planned Organizational Change.” The Leadership Quarterly 21 (3): 422–438. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.03.007.

- Benn, Suzanne, Melissa Edwards, and Tim Williams. 2014. Organizational Change for Corporate Sustainability. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Routledge.

- BMW. 2015. “Sustainable Value Report 2014.” Bayersiche Motoren Werke AG, Munich. Accessed 16 July 2020. https://www.bmwgroup.com/en/download-centre.html.

- BMW. 2018. “Sustainable Value Report 2017.” Bayersiche Motoren Werke AG, Munich. Accessed 16 July 2020. https://www.bmwgroup.com/en/download-centre.html.

- Bosch. 2015. “Sustainability Report 2014.” Robert Bosch GmbH, Stuttgart. Accessed 16 July 2020. https://www.bosch.com/company/sustainability/sustainability-reports-and-figures/.

- Bosch. 2017. “Sustainability Report 2016.” Robert Bosch GmbH, Stuttgart. Accessed 16 July 2020. https://www.bosch.com/company/sustainability/sustainability-reports-and-figures/.

- Brandenburger, Adam, and Barry Nalebuff. 1996. Coopetition: kooperativ konkurrieren. Frankfurt am Main: Deutsche Nationalbibliothek.

- Brix-Asala, Carolin, and Stefan Seuring. 2020. “Bridging Institutional Voids via Supplier Development in Base of the Pyramid Supply Chains.” Production Planning & Control 31 (11–12): 903–919. doi:10.1080/09537287.2019.1695918.

- Burke, W. W. 2017. Organization change: Theory and practice. 5th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- By, Rune T. 2005. “Organisational Change Management: A Critical Review.” Journal of Change Management 5 (4): 369–380. doi:10.1080/14697010500359250.

- Cameron, Esther, and Mike Green. 2019. Making Sense of Change Management: A Complete Guide to the Models, Tools and Techniques of Organizational Change. 5th ed. La Vergne, TN: Kogan Page Publishers.

- Campopiano, Giovanna, and Alfredo de Massis. 2015. “Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting: A Content Analysis in Family and Non-Family Firms.” Journal of Business Ethics 129 (3): 511–534. doi:10.1007/s10551-014-2174-z.

- Carter, Craig R., and Martin Dresner. 2001. “Purchasing's Role in Environmental Management: Cross‐Functional Development of Grounded Theory.” The Journal of Supply Chain Management 37 (3): 12–27. doi:10.1111/j.1745-493X.2001.tb00102.x.

- Carter, Craig R., Marc R. Hatton, Chao Wu, and Xiangjing Chen. 2019. “Sustainable Supply Chain Management: Continuing Evolution and Future Directions.” International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 50 (1): 122–146. doi:10.1108/IJPDLM-02-2019-0056.

- Chen, Lujie, Xiande Zhao, Ou Tang, Lydia Price, Shanshan Zhang, and Wenwen Zhu. 2017. “Supply Chain Collaboration for Sustainability: A Literature Review and Future Research Agenda.” International Journal of Production Economics 194: 73–87. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2017.04.005.

- Choi, Thomas Y., and Zhaohui Wu. 2009. “Taking the Leap from Dyads to Triads: Buyer–Supplier Relationships in Supply Networks.” Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management 15 (4): 263–266. doi:10.1016/j.pursup.2009.08.003.

- Christopher, Martin, and Matthias Holweg. 2011. “‘Supply Chain 2.0’: Managing Supply Chains in the Era of Turbulence.” International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 41 (1): 63–82. doi:10.1108/09600031111101439.

- Continental. 2017. “Sustainability Report 2016.” Continental AG, Hanover. Accessed 16 July 2020. https://www.continental.com/en/sustainability/downloads.

- Daimler. 2016. “Sustainability Report 2015.” Daimler AG, Stuttgart. Accessed 16 July 2020. https://www.daimler.com/sustainability/archive-sustainability-reports.html.

- Daimler. 2018. “Sustainability Report 2017.” Daimler AG, Stuttgart. Accessed 16 July 2020. https://www.daimler.com/sustainability/archive-sustainability-reports.html.

- Daimler. 2019. “Sustainability Report 2018.” Daimler AG, Stuttgart. Accessed 16 July 2020. https://www.daimler.com/sustainability/archive-sustainability-reports.html.

- Dietsche, Christian, Christian Lautermann, and Udo Westermann. 2019. “CSR-Reporting in Deutschland 2018.” IÖW, Berlin. Accessed 16 July 2020. https://www.ranking-nachhaltigkeitsberichte.de/publikationen.html.

- Dixon, Sarah E. A., Klaus E. Meyer, and Marc Day. 2010. “Stages of Organizational Transformation in Transition Economies: A Dynamic Capabilities Approach.” Journal of Management Studies 47 (3): 416–436. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6486.2009.00856.x.

- Dubey, Rameshwar, Angappa Gunasekaran, Stephen J. Childe, Thanos Papadopoulos, Benjamin Hazen, Mihalis Giannakis, and David Roubaud. 2017. “Examining the Effect of External Pressures and Organizational Culture on Shaping Performance Measurement Systems (PMS) for Sustainability Benchmarking: Some Empirical Findings.” International Journal of Production Economics 193: 63–76. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2017.06.029.

- Dubey, Rameshwar, Angappa Gunasekaran, Thanos Papadopoulos, and Stephen J. Childe. 2015. “Green Supply Chain Management Enablers: Mixed Methods Research.” Sustainable Production and Consumption 4: 72–88. Green supply chain management enablers: Mixed methods research.” doi:10.1016/j.spc.2015.07.001.

- Dubey, Rameshwar,Angappa Gunasekaran, Stephen J. Childe, Thanos Papadopoulos, Zongwei Luo, and David Roubaud. 2020. “Upstream supply chain visibility and complexity effect on focal company’s sustainable performance: Indian manufacturers’ perspective.” Annals of Operations Research 290 (1): 343–367.

- Durach, Christian F., and Frank Wiengarten. 2017. “Exploring the Impact of Geographical Traits on the Occurrence of Supply Chain Failures.” Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 22 (2): 160–171. doi:10.1108/SCM-11-2016-0380.

- Elking, Isaac, John-Patrick Paraskevas, Curtis Grimm, Thomas Corsi, and Adams Steven. 2017. “Financial Dependence, Lean Inventory Strategy, and Firm Performance.” Journal of Supply Chain Management 53 (2): 22–38. doi:10.1111/jscm.12136.

- Esfahbodi, Ali, Yufeng Zhang, and Glyn Watson. 2016. “Sustainable Supply Chain Management in Emerging Economies: Trade-Offs between Environmental and Cost Performance.” International Journal of Production Economics 181: 350–366. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2016.02.013.

- Fung, Yi-Ning, Tsan-Ming Choi, and Rong Liu. 2020. “Sustainable Planning Strategies in Supply Chain Systems: proposal and Applications with a Real Case Study in Fashion.” Production Planning & Control 31 (11–12): 883–902. doi:10.1080/09537287.2019.1695913.

- Gehman, Joel, Vern L. Glaser, Kathleen M. Eisenhardt, Denny Gioia, Ann Langley, and Kevin G. Corley. 2018. “Finding Theory–Method Fit: A Comparison of Three Qualitative Approaches to Theory Building.” Journal of Management Inquiry 27 (3): 284–300. doi:10.1177/1056492617706029.

- Ghadge, Abhijeet, Merve Er Kara, Dnyaneshwar G. Mogale, Choudhary Sonal, and Dani Samir. 2020. “Sustainability Implementation Challenges in Food Supply Chains: A Case of UK Artisan Cheese Producers.” Production Planning & Control 13 (2): 1–16.

- Gioia, Dennis A., and Kumar Chittipeddi. 1991. “Sensemaking and Sensegiving in Strategic Change Initiation.” Strategic Management Journal 12 (6): 433–448. doi:10.1002/smj.4250120604.

- Gioia, Dennis A., Kevin G. Corley, and Aimee L. Hamilton. 2013. “Seeking Qualitative Rigor in Inductive Research: Notes on the Gioia Methodology.” Organizational Research Methods 16 (1): 15–31. doi:10.1177/1094428112452151.

- Global Reporting Initiative. 2020. “GRI Standards.” Accessed 19 February 2020. https://www.globalreporting.org/standards/gri-standards-download-center/.

- Golicic, Susan L., and Carlo D. Smith. 2013. “A Meta‐Analysis of Environmentally Sustainable Supply Chain Management Practices and Firm Performance.” Journal of Supply Chain Management 49 (2): 78–95. doi:10.1111/jscm.12006.

- Gopal, P. R. C., and Jitesh Thakkar. 2016a. “Analysing Critical Success Factors to Implement Sustainable Supply Chain Practices in Indian Automobile Industry: A Case Study.” Production Planning & Control 27 (12): 1005–1018. doi:10.1080/09537287.2016.1173247.

- Gopal, P. R. C., and Jitesh Thakkar. 2016b. “Sustainable Supply Chain Practices: An Empirical Investigation on Indian Automobile Industry.” Production Planning & Control 27 (1): 49–64. doi:10.1080/09537287.2015.1060368.

- Graham, Stephanie. 2020. “The Influence of External and Internal Stakeholder Pressures on the Implementation of Upstream Environmental Supply Chain Practices.” Business & Society 59 (2): 351–383. doi:10.1177/0007650317745636.

- Green, Kenneth W., Lisa C. Toms, and James Clark. 2015. “Impact of Market Orientation on Environmental Sustainability Strategy.” Management Research Review 38 (2): 217–238. doi:10.1108/MRR-10-2013-0240.

- Grimm, Jörg H., Joerg S. Hofstetter, and Joseph Sarkis. 2014. “Critical Factors for Sub-Supplier Management: A Sustainable Food Supply Chains Perspective.” International Journal of Production Economics 152: 159–173. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2013.12.011.

- Hadiguna, Rika A., and Benny Tjahjono. 2017. “A Framework for Managing Sustainable Palm Oil Supply Chain Operations: A Case of Indonesia.” Production Planning & Control 28 (13): 1093–1106. doi:10.1080/09537287.2017.1335900.

- Hoejmose, Stefan U., Jens K. Roehrich, and Johanne Grosvold. 2014. “Is Doing More Doing Better? The Relationship between Responsible Supply Chain Management and Corporate Reputation.” Industrial Marketing Management 43 (1): 77–90. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2013.10.002.

- Hofmann, Hannes, Christian Busse, Christoph Bode, and Michael Henke. 2014. “Sustainability‐Related Supply Chain Risks: Conceptualization and Management.” Business Strategy and the Environment 23 (3): 160–172. doi:10.1002/bse.1778.

- Hou, Guisheng, Yu Wang, and Baogui Xin. 2019. “A Coordinated Strategy for Sustainable Supply Chain Management with Product Sustainability, Environmental Effect and Social Reputation.” Journal of Cleaner Production 228: 1143–1156. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.04.096.

- Huq, Fahian A., Ilma N. Chowdhury, and Robert D. Klassen. 2016. “Social Management Capabilities of Multinational Buying Firms and Their Emerging Market Suppliers: An Exploratory Study of the Clothing Industry.” Journal of Operations Management 46 (1): 19–37. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2016.07.005.

- Infineon. 2020. “Sustainability at Infenion: Supplementing the Annual Report 2019.” Infineon Technologies AG, Neubiberg. Accessed 16 July 2020. https://www.infineon.com/cms/en/about-infineon/sustainability/csr-reporting/.

- Jung, Jae C., and Elizabeth Sharon. 2019. “The Volkswagen Emissions Scandal and Its Aftermath.” Global Business and Organizational Excellence 38 (4): 6–15. doi:10.1002/joe.21930.

- Jüttner, Uta, Helen Peck, and Martin Christopher. 2003. “Supply Chain Risk Management: Outlining an Agenda for Future Research.” International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications 6 (4): 197–210. doi:10.1080/13675560310001627016.

- Kiesnere, Aisma L., and Rupert J. Baumgartner. 2019. “Sustainability Management in Practice: organizational Change for Sustainability in Smaller Large-Sized Companies in Austria.” Sustainability 11 (3): 572. doi:10.3390/su11030572.

- Král, Pavel, and Věra Králová. 2016. “Approaches to Changing Organizational Structure: The Effect of Drivers and Communication.” Journal of Business Research 69 (11): 5169–5174. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.04.099.

- Kumar, Niraj, Andrew Brint, Erjing Shi, Arvind Upadhyay, and Ximing Ruan. 2019. “Integrating Sustainable Supply Chain Practices with Operational Performance: An Exploratory Study of Chinese SMEs.” Production Planning & Control 30 (5–6): 464–478. doi:10.1080/09537287.2018.1501816.

- Landrum, Nancy E., and Brian Ohsowski. 2018. “Identifying Worldviews on Corporate Sustainability: A Content Analysis of Corporate Sustainability Reports.” Business Strategy and the Environment 27 (1): 128–151. doi:10.1002/bse.1989.

- Laosirihongthong, Tritos, Premaratne Samaranayake, Sev V. Nagalingam, and Dotun Adebanjo. 2020. “Prioritization of Sustainable Supply Chain Practices with Triple Bottom Line and Organizational Theories: industry and Academic Perspectives.” Production Planning & Control 31 (14): 1207–1221. doi:10.1080/09537287.2019.1701233.

- Lee, Hau L. 2004. “The Triple-A Supply Chain.” Harvard Business Review 82 (10): 102–113.

- Lewin, Kurt. 1947. “Frontiers in Group Dynamics: Concept, Method and Reality in Social Science; Social Equilibria and Social Change.” Human Relations 1 (1): 5–41. doi:10.1177/001872674700100103.

- Lewis, Laurie, and S. Sahay. 2019. Organizational Change. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Online Library.

- Lock, Irina, and Peter Seele. 2016. “The Credibility of CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility) Reports in Europe. Evidence from a Quantitative Content Analysis in 11 Countries.” Journal of Cleaner Production 122: 186–200. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.02.060.

- Luthra, Sunil, Garg Dixit, and Haleem Abid. 2015. “Critical Success Factors of Green Supply Chain Management for Achieving Sustainability in Indian Automobile Industry.” Production Planning & Control 26 (5): 339–362.

- Luthra, Sunil, Sachin K. Mangla, Ravi Shankar, Chandra Prakash Garg, and Suresh Jakhar. 2018. “Modelling Critical Success Factors for Sustainability Initiatives in Supply Chains in Indian Context Using Grey-DEMATEL.” Production Planning & Control 29 (9): 705–728. doi:10.1080/09537287.2018.1448126.

- Macchion, Laura, Alessandro Da Giau, Federico Caniato, Maria Caridi, Pamela Danese, Rinaldo Rinaldi, and Andrea Vinelli. 2018. “Strategic Approaches to Sustainability in Fashion Supply Chain Management.” Production Planning & Control 29 (1): 9–28. doi:10.1080/09537287.2017.1374485.

- Madhavan, Ravindranath, Devi R. Gnyawali, and Jinyu He. 2004. “Two's Company, Three's a Crowd? Triads in Cooperative-Competitive Networks.” Academy of Management Journal 47 (6): 918–927.

- Mann, Hanuv, Uma Kumar, Vinod Kumar, and Inder J. S. Mann. 2010. “Drivers of Sustainable Supply Chain Management.” IUP Journal of Operations Management 9 (4): 52–63.

- Menzel, S. 2020. “Warum der 32 Milliarden Euro teure Dieselskandal auch seine positive Seite hat.” Accessed 14 December 2020. https://www.handelsblatt.com/meinung/kommentare/analyse-der-vw-affaere-warum-der-32-milliarden-euro-teure-dieselskandal-auch-seine-positive-seite-hat/26193462.html?ticket=ST-12860348-tTEzDfTZIbbIQM0qYyZY-ap5.

- Mol, Michael J. 2003. “Purchasing's Strategic Relevance.” Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management 9 (1): 43–50. doi:10.1016/S0969-7012(02)00033-3.

- Puls, Thomas, and Manuel Fritsch. 2020. IW-Report 43/2020. Eine Branche unter Druck: Die Bedeutung der Autoindustrie für Deutschland. Köln: Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft.

- Rodríguez, Jorge A., Cristina Giménez, and Daniel Arenas. 2016. “Cooperative Initiatives with NGOs in Socially Sustainable Supply Chains: How Is Inter-Organizational Fit Achieved?” Journal of Cleaner Production 137: 516–526. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.07.115.

- Rossi, Adriana, and Lara Tarquinio. 2017. “An Analysis of Sustainability Report Assurance Statements.” Managerial Auditing Journal 32 (6): 578–602. doi:10.1108/MAJ-07-2016-1408.

- Saeed, Muhammad A., and Wolfgang Kersten. 2019. “Drivers of Sustainable Supply Chain Management: Identification and Classification.” Sustainability 11 (4): 1137. doi:10.3390/su11041137.

- Sajjad, Aymen, Gabriel Eweje, and David Tappin. 2015. “Sustainable Supply Chain Management: Motivators and Barriers.” Business Strategy and the Environment 24 (7): 643–655. doi:10.1002/bse.1898.

- Savino, Matteo M., Riccardo Manzini, and Antonio Mazza. 2015. “Environmental and Economic Assessment of Fresh Fruit Supply Chain through Value Chain Analysis: A Case Study in Chestnuts Industry.” Production Planning & Control 26 (1): 1–18. doi:10.1080/09537287.2013.839066.

- Schaeffler. 2017. “Sustainability Report 2016.” Schaeffler AG, Herzogenaurach. 16 Accessed July 2020. https://www.schaeffler.com/content.schaeffler.com/en/company/sustainability/reports_and_downloads/reports-and-downloads.jsp.

- Schwarz, Gavin M. 2012. “Shaking Fruit out of the Tree: Temporal Effects and Life Cycle in Organizational Change Research.” The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 48 (3): 342–379. doi:10.1177/0021886312439098.

- Senior, Barbara, and Jocelyne Fleming. 2006. Organizational Change. 3rd ed. Essex, GB: Pearson Education.

- Shibin, K. T., Rameshwar Dubey, Angappa Gunasekaran, Benjamin Hazen, David Roubaud, Shivam Gupta, and Cyril Foropon. 2020. “Examining Sustainable Supply Chain Management of SMEs Using Resource Based View and Institutional Theory.” Annals of Operations Research 290 (1–2): 301–326. doi:10.1007/s10479-017-2706-x.

- Shibin, K. T., Rameshwar Dubey, Angappa Gunasekaran, Zongwei Luo, Thanos Papadopoulos, and David Roubaud. 2018. “Frugal Innovation for Supply Chain Sustainability in SMEs: Multi-Method Research Design.” Production Planning & Control 29 (11): 908–927. doi:10.1080/09537287.2018.1493139.

- Silverman, David. 2020. Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Limited.

- Silvestre, Bruno S. 2015. “Sustainable Supply Chain Management in Emerging Economies: Environmental Turbulence, Institutional Voids and Sustainability Trajectories.” International Journal of Production Economics 167: 156–169. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2015.05.025.

- Skjott-Larsen, Tage, Philip B, Schary, Herbert Kotzab, and Juliana H. Mikkola. 2007. Managing the Global Supply Chain. 3rd ed. Copenhagen, DK: Copenhagen Business School Press.

- Steven, Adams B., Yan Dong, and Thomas Corsi. 2014. “Global Sourcing and Quality Recalls: An Empirical Study of Outsourcing-Supplier Concentration-Product Recalls Linkages.” Journal of Operations Management 32 (5): 241–253. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2014.04.003.

- Svensson, Göran. 2004. “Key Areas, Causes and Contingency Planning of Corporate Vulnerability in Supply Chains.” International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 34 (9): 728–748. doi:10.1108/09600030410567496.

- Tappia, Elena, Gino Marchet, Marco Melacini, and Sara Perotti. 2015. “Incorporating the Environmental Dimension in the Assessment of Automated Warehouses.” Production Planning & Control 26 (10): 824–838. doi:10.1080/09537287.2014.990945.

- Thun, Jörn-Henrik, and Daniel Hoenig. 2011. “An Empirical Analysis of Supply Chain Risk Management in the German Automotive Industry.” International Journal of Production Economics 131 (1): 242–249. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2009.10.010.

- Thun, Jörn‐Henrik, and Andrea Müller. 2010. “An Empirical Analysis of Green Supply Chain Management in the German Automotive Industry.” Business Strategy and the Environment 19 (2): 119–132.

- Torelli, Riccardo, Federica Balluchi, and Katia Furlotti. 2020. “The Materiality Assessment and Stakeholder Engagement: A Content Analysis of Sustainability Reports.” Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 27 (2): 470–484. doi:10.1002/csr.1813.

- Touboulic, Anne, and Helen Walker. 2015. “Theories in Sustainable Supply Chain Management: A Structured Literature Review.” International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 45 (1/2): 16–42. doi:10.1108/IJPDLM-05-2013-0106.

- Turker, Duygu, and Ceren Altuntas. 2014. “Sustainable Supply Chain Management in the Fast Fashion Industry: An Analysis of Corporate Reports.” European Management Journal 32 (5): 837–849. doi:10.1016/j.emj.2014.02.001.

- Vachon, Stephan, and Robert D. Klassen. 2008. “Environmental Management and Manufacturing Performance: The Role of Collaboration in the Supply Chain.” International Journal of Production Economics 111 (2): 299–315. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2006.11.030.

- Villena, Verónica H., and Dennis A. Gioia. 2018. “On the Riskiness of Lower-Tier Suppliers: Managing Sustainability in Supply Networks.” Journal of Operations Management 64 (1): 65–87. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2018.09.004.

- Volkswagen. 2015. “Sustainability Report 2014.” Volkswagen AG, Wolfsburg. Accessed 16 July 2020. https://www.volkswagenag.com/en/sustainability/reporting.html.

- Volkswagen. 2017. “Sustainability Report 2016.” Volkswagen AG, Wolfsburg. Accessed 16 July 2020. https://www.volkswagenag.com/en/sustainability/reporting.html.

- Volkswagen. 2019. “Sustainability Report 2018.” Volkswagen AG, Wolfsburg. Accessed 16 July, 2020. https://www.volkswagenag.com/en/sustainability/reporting.html.

- Volkswagen. 2020. “Sustainability Report 2019.” Volkswagen AG, Wolfsburg. Accessed 16 July 2020. https://www.volkswagenag.com/en/sustainability/reporting.html.

- Wenzel, Matthias, Anja Danner-Schröder, and A. P. Spee. 2020. “Dynamic Capabilities? Unleashing Their Dynamics through a Practice Perspective on Organizational Routines.” Journal of Management Inquiry. doi:10.1177/1056492620916549.

- Wetzel, Philipp, and Erik Hofmann. 2019. “Supply Chain Finance, Financial Constraints and Corporate Performance: An Explorative Network Analysis and Future Research Agenda.” International Journal of Production Economics 216(1): 364–383. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2019.07.001.

- Wilhelm, Miriam M., Constantin Blome, Vikram Bhakoo, and Antony Paulraj. 2016. “Sustainability in Multi-Tier Supply Chains: Understanding the Double Agency Role of the First-Tier Supplier.” Journal of Operations Management 41 (1): 42–60. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2015.11.001.

- Wu, Zhaohui, and Thomas Y. Choi. 2005. “Supplier–Supplier Relationships in the Buyer–Supplier Triad: Building Theories from Eight Case Studies.” Journal of Operations Management 24 (1): 27–52. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2005.02.001.

- Wu, Zhaohui, Thomas Y. Choi, and M. J. Rungtusanatham. 2010. “Supplier–Supplier Relationships in Buyer–Supplier–Supplier Triads: Implications for Supplier Performance.” Journal of Operations Management 28 (2): 115–123. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2009.09.002.

- Wu, Zhaohui, and Mark Pagell. 2011. “Balancing Priorities: Decision-Making in Sustainable Supply Chain Management.” Journal of Operations Management 29 (6): 577–590. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2010.10.001.

- Wu, John, Steve Dunn, and Howard Forman. 2012. “A Study on Green Supply Chain Management Practices among Large Global Corporations.” Journal of Supply Chain and Operations Management 10 (1): 182–194.

- Xu, Ming, Yuanyuan Cui, Meng Hu, Xinkai Xu, Zhechi Zhang, Sai Liang, and Shen Qu. 2019. “Supply Chain Sustainability Risk and Assessment.” Journal of Cleaner Production 225: 857–867. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.03.307.

- Friedrichshafen, Z. F. 2015. “Sustainability Report 2014.” ZF Friedrichshafen, Friedrichshafen. Accessed July 16, 2020. https://www.zf.com/mobile/en/company/sustainability/sustainability_report/sustainability_report.html.

- Zhu, Qinghua, Yihui Tian, and Joseph Sarkis. 2012. “Diffusion of Selected Green Supply Chain Management Practices: An Assessment of Chinese Enterprises.” Production Planning & Control 23 (10–11): 837–850. doi:10.1080/09537287.2011.642188.

- Zimon, Dominik, Jonah Tyan, and Robert Sroufe. 2019. “Implementing Sustainable Supply Chain Management: Reactive, Cooperative, and Dynamic Models.” Sustainability 11 (24): 7227. doi:10.3390/su11247227.

- Zimon, Domnik, Jonah Tyan, and Robert Sroufe. 2020. “Drivers of Sustainable Supply Chain Management: Practices to Alignment with UN Sustainable Development Goals.” International Journal for Quality Research 14 (1): 219–236. doi:10.24874/IJQR14.01-14.