It has been more than a year and a half since the world woke up to the COVID-19 reality/ies. There was considerable confusion at the beginning as to what this was, and how long it would last, even after the World Health Organization (WHO), on January 31, 2020, had declared the coronavirus outbreak a ‘public health emergency’ of international proportions, and still even several weeks later, when on March 11, 2020, WHO Director-General, Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, finally declared the coronavirus a pandemic.

It took considerably more time to recognize the severity of the crisis itself, and the possible damages that it could in turn cause. While the majority of economists had no clue how this exactly fit within their fair-weather models, post-Keynesians had certainly an inkling of what was to come: with supply chain difficulties and a health-care crisis, many of us understood this health crisis would eventually turn into a crisis of aggregate demand, although not one that could be easily solved with traditional Keynesian fiscal means as long as the virus existed. It was in many respects, a perfect storm: simultaneous breakdowns in both supply and demand conditions, which would paralyze much of the world economy.

In this context, the COVID-19 crisis stands in contrast to previous crises, like the 2007/8 global financial crisis, which was in many ways a ‘typical’ crisis of aggregate demand. At the time, central banks did what they normally do in times of slowdown in economic activity. They lowered interest rates (and contributed to the emergence of a great many articles on what we can call the ‘economics of the lower bound’). Governments, on the other hand, primed the fiscal pump. While that crisis was unfolding within a greater crisis of secular stagnation, post-Keynesians understood the need to support aggregate demand as a way of resolving the immediate crisis. Of course, we did not dismiss calls for reforming capitalism, and the need for regulations, but policy priority rested in an immediate support of aggregate demand.

But the current COVID-19 crisis was largely different. There was undeniably an aggregate demand component. While essential, demand stimulus was not sufficient, and the policy priority in this case was overwhelmingly about the need to eradicate the virus or inoculate the population, which required time. Surely any traditional Keynesian-type fiscal policies and near-zero interest rates, both certainly welcome, are not going to be sufficient this time. Moreover, the immediate impact of the COVID-19 crisis was a historical and unparallel drop in output around the world that prompted, in turn, unprecedented government action, although the response proved considerably uneven.

Indeed, it quickly became apparent that the fiscal approaches to the COVID-19 crisis varied across countries. While some governments quickly revived the spirit of Keynes, and adopted a number of programs aimed at supporting workers, incomes and jobs, such as in Canada for instance, in Mexico, the AMLO government did very little on the spending side in comparison. The United States fell somewhere in between, but certainly at the lower end of the spectrum under the Trump administration. To be sure, Keynesian-type aggregate demand policies did serve a purpose, though they were surely not sufficient. Nevertheless, they succeeded in preventing a dire situation from worsening.

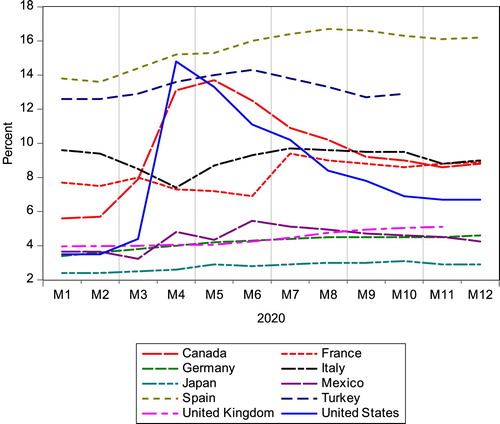

As these economies collapsed and many governments propped up their spending to sustain households and businesses through various support programs, unemployment rates tended upwards, somewhat. However, the labour market response was not the same across countries. While facing similar cuts in growth rates, as the COVID-19 shock was propagated internationally, unemployment rates rose dramatically in Canada and the United States, but they fluctuated little in some other countries regardless of the degree of public spending (see below).

Figure 1. Evolution of official monthly unemployment rates during 2020 in selected OECD countries. Source: OECD.Stat.

In certain countries of the developing world, unemployed workers released from the formal sector may have partly been absorbed by the informal sector, as perhaps in Mexico, thereby resulting in mitigated effects on their official unemployment rates. In other cases, as in Europe and Japan, the unemployment rate remained relatively stable in the face of the crisis but for rather different reasons. Indeed, in the case of France and Italy, as depicted in the chart below, there was even an initial decline of the unemployment rate during the early period of the pandemic as the huge labour market withdrawals more than outweighed the collapse of employment demand.

As is displayed in below for ten selected countries of the OECD, for instance, the measured unemployment rate went from 3.5 percent of the labour force at the beginning of 2020 in the United State to almost Great Depression rates of unemployment of 14.7 percent by April and then back down to 6.7 percent by the end of 2020. In Italy, on the other hand, the official unemployment rate started at 9.6 percent at the beginning of 2020, it fell to 7.4 percent in April and then climbed back up to 9.0 percent by the end of 2020. These different labour market responses reflect the institutional peculiarities and internal dynamics within these disparate economies, therefore, making it difficult to generalize the labour market experiences internationally.

It is impossible here to do justice to the many policies adopted during this pandemic by various countries, and certainly a description is an overwhelming task within the confines of this introduction, although some of the papers in this symposium (see Sawyer, for instance) offer glimpses of an analysis (see KPMG Citation2020; IMF Citation2021, for an overview of per country programs). One thing is clear: many of these policies were adopted with great urgency, although with hindsight, may not have been the best designed policies. Many countries will surely undertake analyses to determine the degree of success, on the one hand, and the possible fiscal excesses that will be raised by the deficit hawks, on the other.

The inevitable result has certainly been the dramatic and unprecedented increase of public deficits, which in some countries increased ten-fold, at a minimum. In Canada, it went from some $26 billion in March 2019, to close to $400 billion today. Similar scenarios are playing out around the world. And so far, the deficit hawks have been kept largely at bay, and public finance criticism has been focused on how money is spent, not whether we should spend at all. There is a general consensus that fiscal policy is required to prevent further economic deterioration, although whether this consensus will hold for, say, six more months or so (at the time of writing, say, by September 2021) is left to be seen.

However, the real challenge for functional finance will come after the vaccination. Indeed, we expect that once the pandemic is over, there will be calls for deficit reductions and the economics of sound finance will find an important footing among political parties and governments on both the right and the left under political pressure to eliminate deficits.

The usual economic arguments are starting to emerge: already there are arguments about the inflationary threats of these deficits, which have generated a massive increase in personal saving with nowhere to spend our incomes. Owing to this pent-up demand, as the story goes, once the vaccine is distributed, there will be a surge of economic activity and we will quickly return to pre-COVID-19 conditions with inflation. Of course, for inflation to arise, this story assumes we will quickly return to full employment and wages may start to soar in excess of productivity growth.

Finally, we need to address not only the domestic and international ‘health’ inequalities that have been so deeply revealed by the pandemic but also the increases in both income and wealth inequalities caused by the ensuing economic crisis. Indeed, it is safe to assume that the dramatic increase in savings resulting from the significant deficit spending of the public sector is concentrated among upper income households who would have benefited from purchasing various titles on the stock market, thereby contributing to the incredible rise in asset values in the last year. This build-up of private wealth of these public deficits was further compounded by the large-scale central bank asset purchases or quantitative easing, which enhanced private asset values at a time when market incomes and the real economy were collapsing. Moreover, depending on the spending programs put in place in the various countries, there was some limited debt relief for both households and firms in certain sectors of the economy. A large segment of workers, however, were made worse off by the crisis, and contributed to increased housing and food insecurities. It has been shown too that non-COVID-related mortality rates (drug-induced, for instance) have increased during the COVID-19 crisis. This has contributed to the increased rhetoric of ‘building back better’.

This symposium

When we decided back in April, 2020, to host not only this symposium, but another one as well in the International Journal of Political Economy (IJPE) – a sister Taylor and Francis journal – the aim was for both of our journals to join forces in producing quality articles on the causes and aftermath of this crisis, from a clear heterodox perspective. The IJPE symposium was published in December 2020.

In this symposium, we have papers that focus more on the European economy (Sawyer) or specifically on Italy (Canelli, Fontana, Veronese Passarella, and Realfonzo), economic theory (Charles, Dallery and Marie; Goes and Gallo; and Michl), and a paper arguing that the COVID crisis was an inherent trait of the capitalist social form of production and consumption (Bellofiore).

The current crisis raises important questions about the state of capitalism today, and the inherent weaknesses of neoliberal economic policies. This is a research agenda that is proving more urgent than ever, and this symposium, as well as the one in the IJPE, hopes to contribute to some early answers, and possible future areas of research.

References

- IMF. 2021. Database of Fiscal Policy Responses to COVID-19. https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/imf-and-covid19/Fiscal-Policies-Database-in-Response-to-COVID-19.

- KPMG. 2020. Government Response – Global Landscape: An Overview of Government and Institution Measures Around the World in Response to COVID-19. https://home.kpmg/xx/en/home/insights/2020/04/government-response-global-landscape.html.