ABSTRACT

Development economics must be rethought. Not only has it hindered the liberation of the Global South, it has also deflected attention from the most critical questions of underdevelopment. Much economics inspires dirty growth, while Western political economy risks defending recolonisation under the guise of protecting nature in the Global South. Most alternative development theorising is similarly Western-centric. Georgist political economy is a possible exception. The systems of land economics Georgist political economy offers is functional and adaptable, often reflecting and supporting ancient knowledge of the earth, facilitating the decolonisation of society, economy, and ecology. The challenge is how to bring about this transformation when many interests potentially run counter to this non-Western alternative development economics.

1. Crisis in Development Economics

Development economics is in long-term crisis. Its condemnation is often associated with Poly Hill’s (Citation1986) classic book Development Economics on Trial. Hill, a student of Joan Robinson, claimed that development economics was Western-centric. In terms of its concepts, its approaches, and its policy focus, development economics looked to the West to save the rest; it did not look to the Global South for solutions to the problems of development. Hill’s specific targets were neoclassical development economics and Marxian development economics.

Way before Hill, however, there had been many critics. Among the pioneers of development economics who challenged the status quo was W. Arthur Lewis, the first black economist to win the Nobel Prize in economics (Tignor Citation2006). Lewis first offered a course in ‘colonial economics’ (as development economics was then called) at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) in 1943–44 in response to demands by students of colour from Africa, Asia, and Latin America who struggled to find courses that reflected their reality. Lewis’ course and research soon established him as an authority in the emerging field of development economics. Lewis (Citation1953, Citation1954, Citation1965, Citation1979) sought to contribute to the emerging field of development economics in such a way that it would emphasise political and economic independence of the poorer nations. Although political economists regard Lewis as a moderate critic of mainstream development economics (Tignor Citation2006, pp. 22–32), his interest in persistent racism, which other development economists such as Theodore Schultz (Citation1961) considered trivial, made him a serious critic of development economics.

John Kenneth Galbraith launched a similar challenge to development economics. Although much less interested in persistent racism, he made other fundamental contributions to reconstructing development economics (for commentaries, see Lewis Citation1985; Darity Citation2009; Darity, Hamilton, and Stewart Citation2015; Leonard Citation2016; Obeng-Odoom Citation2020b, pp. 44–46). For example, Galbraith pointed out that, even at its inception, neoclassical development economics was, in essence, a Western project. Seeking to create the ‘developing’ world in the image of the so-called first world, development economics could not provide genuine liberation. In The Nature of Mass Poverty, Galbraith (Citation1979) argued that the goals of development economics were suited to the needs of the rich, not the poor. Whatever the rich Western nations could offer became the ends of economic development.

This feature was fundamental to development economics. According to Galbraith (Citation1979, pp. 34–35), the American state was aware of widespread poverty, but it was more concerned about how that condition would further enhance the spread and acceptance of communism. Something had to be done. ‘There had to be action’, wrote Galbraith (Citation1979, p. 35), ‘the commitment to this was powerful. But if there was to be a remedy, there had to be a cause. If it couldn’t otherwise be identified, it would have to be invented or assumed’. Galbraith (Citation1979, p. 35) continued, ‘[w]e suppose that on social questions we proceed from diagnosis to action. But if action is imperative, we make the cause fit the action. So it was here’. Because of this invention of development economics to suit American interests, drivers of poverty that America favoured had to be excluded from development economics. In this respect. As Galbraith (Citation1979, p. 36) noted, ‘[t]he most obvious of the possible causes of poverty that had to be excluded was the economic system’ favoured by the US.

Academic economists refused to accept that context and social institutions of the poor had to be studied in their own right. If they did, context was confused for ‘culture’ which, to this day, is used to explain that inter-group disparities arise from certain traits of those in the Global South (Obeng-Odoom Citation2020b). These economists preferred Western ‘solutions’ to Southern alternatives. Local institutions were devalued. Local solutions were sidelined. Only Western standards mattered; deviating from them was not development. Yet, these standards reflected Western interests, needs and experiences. Today, both neoclassical economics and new institutional development economics (e.g. Acemoglu and Robinson Citation2012) take such a Western-centric approach (Darity and Triplett Citation2008; Mkandawire Citation2015).

Consider the idea of ‘economic development’. According to H.W. Arndt (Citation1987), this key focus of development economics has changed in meaning over the years, but every new emphasis has tended to favour the North by distracting attention from the South. Such is evidently the case with free trade. Policies imposed on the Global South, according to Ha-Joon Chang (Citation2002), diverge from Western history of protectionism. One set of rules applies to the West; another applies to the rest. As the Sudanese feminist political economist, Eiman Zein-Elabdin (Citation2016) notes, most of the other traditions in development economics are complicit in this western-centricism.

Georgist political economy (GPE) is one possible exception (George Citation1878, Citation1884; Harrison Citation2008; Haila Citation2016). Advocates claim that GPE can serve as the basis for the transformation of the Global South (Obeng-Odoom Citation2020b). GPE’s focus on land and the institution of property rights more widely provides one avenue for analysing and transcending the contradictions in mainstream, Western-centric development economics. Land plays a prominent place in many demands for black emancipation (Darity Citation2008). Among Indigenous people, land is everything.

Development economics has a place for land, too. But, ever since Alchian and Demsetz (Citation1973) announced their ‘property rights paradigm,’ development economics has taken its inspiration for land reform from new institutional economics. Land is considered an asset, indistinguishable from capital and wealth. On this commodity view of land, non-Western institutions are undeveloped because they have not transformed their land tenure systems into Western forms of property ownership. Developing a system of private property in land, according to this Western-centric view, will address the problem of poverty in the Global South. Prosperity will also be broadly shared. These ideas of poverty and progress are long standing. Since the 17th century, the natural rights school of property economics has become the dominant group defending this commodity view of land. More recently, institutional development economists (de Soto Citation2000; Field Citation2007) have railed against non-Western systems of private property rights and management.

The conceptual mistakes and biases in this commodificaton-of-land framework has been pointed out frequently, starting with J.R. Commons (Citation1924/Citation1925, Citation1924[2012], Citation1934[1990]) and Thorstein Veblen (Citation1923[2009]). Some modern political economists (e.g. Elahi and Stilwell Citation2013) have extended the conceptual critiques of Commons and Veblen; others (Abdulai and Ndekugri Citation2007; Hammond Citation2008; Obeng-Odoom Citation2016a, Citation2016b) have noted a disconnect between the theoretical proposals and the reality of nations following the path of land commodification. It is apparent that the ideas of new institutional economics regarding private property have become associated with particular political-economic groups in whose interests it is to obfuscate the material interests of their proponents, including the World Bank, a major investor in land (George Citation1883[1966], pp. 171–193; Liberti Citation2013).

Currently, development economics is in need of some radical alternatives. Such new pathways must possess at least three characteristics: a critique, an alternative vision, and a strategy. Erik Olin Wright (Citation2010, p. 8) has called this approach to constructing radical change an ‘emancipatory social science.’ Critique does not stop at analysing what is wrong. Diagnosing why some wrong persists is important, too. Alternatives cannot just be utopian; they must combine theoretical plausibility with empirical verifiability. Strategy cannot just be ideas-based; it must entail organisation (Stilwell Citation2000, pp. 13–24). The nature of that mobilisation will depend on whether the current crisis is sustained by ignorance, interests, ideologies, or institutions. Usually it is all of them (Stilwell Citation2019, Ch. 13).

GPE provides one possible pathway (George Citation1883[1966], Citation1885, Citation1898). Centred on land and land rent, GPE provides a critique of orthodoxy, and then offers an alternative vision and a range of proposed paths to attain it. From a GPE perspective, alternative ideas and practices about the economy, society, and ecology are systematically utilised (Ryan-Collins, Lloyd, and Macfarlane Citation2017). These ideas are dismissed in mainstream development economics. Yet, in GPE, these ideas and practices can be better explored, their principles clarified, and their repercussions for progress without poverty more systematically demonstrated.

This paper attempts to investigate the GPE approach more carefully. It argues that not only can GPE guide the development of institutions to drive the well-being and prosperity of nations, GPE can also provide a compass in the struggle for a safer, more inclusive, and cleaner world. From a GPE perspective, western institutions of landed property are central to the current socio-ecological crisis. Alternative ideas about land, now commonly found in non-Western societies, can usefully help to resolve these crises, help to resolve the seeming contradictions between ‘sustainability’ and ‘development’, and address the puzzle about ‘just sustainabilities’ (Agyemang Citation2013). These arguments are developed in the remaining three sections of the paper, respectively titled: unequal development, unequal power, and obstacles to progress. All there sections act as mini case studies and illustrate the problems and prospects of GPE.

2. Uneven Development

Georgist political economists are interested in uneven spatial and social development. Unlike in other schools of thought, GPE explains uneven development as a function of private rent extraction. This emphasis on the place of rent in the economy and society more generally can be illustrated with the analysis of rural development, urban development, and the wider question of uneven global development. Henry George himself showed how this analysis could be done in Social Problems (George Citation1883[1966], pp. 219–240). Contemporary Georgist political economists (Obeng-Odoom Citation2009, Citation2015; Gaffney and Goodall Citation2016) have examined social relations in rural areas. They tend to focus on how the coloniser used force, law and inducements to appropriate rural land, manipulate rural labour, and shape rural development. All these processes of manipulation, exclusion and expulsion served colonial interests.

Analysing systems of landed elites, Georgist political economists focus on slavery and the appropriation of land by slave owners. Unaccountable monarchs, chiefs and priests are also studied as colonial artefacts. For example, research which seeks to develop GPE-related land economics (Forstater Citation2005; Obeng-Odoom Citation2015, Citation2020a, Citation2020b, Citation2021) shows how slavery, the colonial introduction of land tax, and the commodification of rural land forced rural populations in Africa to hire themselves out as wage labour. Others have focused on how transnational corporations, through so-called rural development programmes, which essentially extend agri-businesses, have led to widespread evictions of rural populations to urban centres (e.g. Obeng-Odoom Citation2009). Together with analysing how landlords in cities live off the rent paid by their tenants in rural areas, contemporary research (Rowlandson Citation1996; Obeng-Odoom Citation2013, Citation2015) shows the centrality of absentee land ownership and rentierism to uneven geographies.

These lines of investigation are quite distinct from how other schools of thought approach uneven development. Consider the approach of neo-classical development economics (Fosu Citation2010). Led by economists such as Michael Lipton (Citation1977), the issue of urban bias is taken seriously. The principal concern for critics of urban bias is that cities are too privileged. The state is complicit because it inefficiently subsidises urban living and creates incentives that draw rural population to urban centres. Accordingly, international development agencies, inspired by this neoclassical development economics, push structural adjustment programmes to remove urban bias in Africa (Njoh Citation2003), while the privatisation of rural land is pursued as a strategy to stimulate rural development (Todaro and Smith Citation2006, pp. 343–346, 422–469). According to such critics of urban bias, who often double as proponents of rural development, commodification of the earth provides incentives for the establishment of agribusiness in rural areas. Others propose a green revolution, entailing the use of technology and genetically modified seeds as stepping stones to rural, private-led economic growth, modernisation and development. (Rostow Citation1959; Lipton Citation2020).

Other schools of thought analyse the disparities between rural and urban areas differently. Marxist dependency and postcolonial political-economic approaches point to colonial policies and capitalist development as being responsible for land monopoly in rural areas. David Harvey (Citation2006) writes about ‘uneven geographical development’. Dependency theorists strongly emphasise metropolitan and satellite relations within nations, but also across them, as driving unequal geographies of development (Frank Citation1966). Typically, the analysis tends to emphasise that capital is concentrated in urban centres, which exploit rural labour (Obeng-Odoom Citation2013, p. 22). In A Theory of Uneven Development, Harvey (Citation2003) tried to develop a framework to show the continuing relationship between primitive accumulation and expanded reproduction, calling attention to the dialectical relationship between city and country.

Yet, most Marxist political economists have focused on land in relation to rural peasants, disconnected from processes of expanded reproduction. The criticism of Marxist political economy tends to focus on industrial urban-based capital. When they turn to rural development, their focus has been on rural peasant movements to prevent the physical enclosure of land or to promote physical land redistribution. Postcolonial approaches share the Marxist/dependency interest in the redistribution of parcels of land in rural settings, although their analyses of urban development increasingly emphasise absolute space; not the Marxist focus on relational space along with relative and absolute space (Harvey Citation2006). The most successful recent versions of postcolonial urban analysis stress ordinariness and the need to analyse cities in Africa mainly in their own terms (Robinson Citation2006). The tendency is to reject modernisation by celebrating tradition or uniqueness. The analysis is less about relating urban development to its wider structures or global systems, as Marxists (e.g. Harvey Citation2003, Citation2006) and dependency theorists (e.g. Frank Citation1966) tend to do.

New institutional economics is also critical of uneven geographies. However, it points to the inefficiencies of concentrated land ownership in the countryside as the source of the problem. As a school of thought, new institutional economics is similar to neoclassical economics. Its adherents tend to maintain that urban-based landlords are responsible for unbalanced development. Its proposed alternative is to pursue property-owning democracy by spreading private property (de Soto Citation2000). An early advocate of this approach was Pope Leo XIII, who set out a thesis addressing rural and urban poverty through property-owning democracy in his encyclical letter to the world, Rerum Novarum (Leo Citation1891).

GPE differs from these approaches. Advocates of GPE tend to seek the redistribution of rent, not parcels of land (Harrison Citation2008; Cobb Citation2016). More fundamentally, as George (Citation1891) explains in his response to Pope Leo XIII, the alternatives offered by the other schools of thought are part of the problem. They deny workers the right to the full reward for their labour and compromise the common right of workers to land, and transfer wealth from producers to speculators. One study (Obeng-Odoom Citation2009) showed that African farms and resources served as a reservoir for the industrialisation of the West. Apart from raw materials, Africa provided food for Western industrial workers. So, rural development processes that are not Georgist in orientation can easily become a continuation of uneven and extractivist pattern of development where expulsion and exploitation were justified in the name of ‘law and development’ (Manji Citation2006, pp. 31–47) as was the case in the 1980s.

The 1980s was characterised by widespread privatisation of land as part of structural adjustment programmes, which made land privatisation a precondition for obtaining World Bank loans (Manji Citation2006, pp. 31–47). Streamlining laws, establishing the needed departments and agencies, and going through the process of institutionalising title registration all cost significant money, but the World Bank and other development banks provided financing in many cases. Altogether, since the 1990s, some US$9 billion has been given by the World Bank and other development agencies to aid the process of commodifying land in Africa. Much of this money has gone into changing the rules of property transactions in order to reduce transaction costs and enhance the operation of property markets (Manji Citation2006, p. 52).

Advocates of this process claim that agribusiness flourishes during this process of formalisation and commodification. Proponents also praise resulting large-scale commercial farming and new technologies, which apparently increase the position of African farmers in the global value chains of production (Collier and Venables Citation2012). However, some evidence calls these claims into question. In Ethiopia (Ruben, Bekele, and Lenjiso Citation2017), after years of rural development, powerful transnational corporations still dominate the global value chain, while African small-scale farmers struggle to improve their position.

From a Georgist perspective, evidence of ‘eviction of millions of small farmers in poor countries owing to the 220 million hectares of land, or over 540 million acres, acquired by foreign investors and governments since 2006’ (Sassen Citation2014, p. 3) shows that rural development has not succeeded. In addition, it has made a bad situation worse. While the evictees form new slums or swell the population of existing ones, property developers build new gated estates, which fetch much higher rents (Obeng-Odoom Citation2014; Obeng-Odoom, Elhadary, and Jang Citation2014; Owusu-Ansah et al. Citation2018). So, land commodification has also contributed to major internal inequalities.

In cities, land commodification has intensified, too. A major turning point in this transformation was the time when there was widespread removal of subsidies from urban necessary goods in Africa (Obeng-Odoom Citation2013). This process of land marketisation created the scaffold for speedy processing of land title registration. In Ghana, for example, the time it takes to register landed property was reduced from 36 months to 2.5 months between 2003 and 2011 (Obeng-Odoom Citation2016a, p. 670). However, establishing strong bases for land markets has neither led to prosperity through ease of land transactions and access to bank loans nor provided security of tenure in the country (Hammond Citation2008; Domeher, Abdulai, and Yeboah Citation2016).

Instead, the commodification of land has increased the insecurity of tenure (Asante Citation1975; Obeng-Odoom Citation2016a; Bansah Citation2017). As competition over land has risen and social institutions, such as chieftaincy, that have long ensured the redistribution of land have become transactional, the resulting conflicts have pushed the wealthy into gated communities (Ehwi, Morrison, and Tyler Citation2019). This ‘spatial fix’, however, is phyrric victory because the development of gated estates has further polarised the society in spatial terms. Urban economic inequality has, therefore, clearly taken a physical form (Obeng-Odoom Citation2020a, Citation2020b, Citation2021). Speculation in land has also become increasingly common, as has the number of land-related conflicts (Obeng-Odoom Citation2020a, Citation2020b, Citation2021), creating new fault lines of rural-urban inequality within the persistent old forms of inequality.

Addressing these problems must be part of any alternative approach to development economics. GPE provides some solutions. For privatised land, George proposed a distribution of land rent, not physical land, and he proposed non-commodification for so-called frontier land. In this strategy, taxes will be shifted from labour and productive capital to land value. These land rents will be socialised by being invested in social protection, public programmes, and the protection of the environment. This programme will be good for land, labour, and capital, and so good for nature, society, and economy (George Citation1883[1966], pp. 209–212). Speculative uses of land would be discouraged and the rising rents that contribute to slums, homelessness, displacement, and hunger and food poverty would be ameliorated, if not eliminated. Hoarded land would be brought into more productive uses. Farmers thrown off their land by land concentration would have plots to till. Inequalities associated with these processes would also be curtailed, as privileges are taxed away.

Increased land value, arising from collective activities in the community, would be returned to the public in the form of tax revenue. Such gains would not be kept by monopolists and speculators as rent. With the resulting revenues, a public fund would be created that can be used for public purposes (George Citation1883[1966], pp. 217–218). The state could develop social intervention and protection schemes, as well as public programmes, including free education and health care, and ecologically sensitive interventions. GPE advocates ending the income tax, so the state could save on the costs of not running institutions that administer income tax. Importantly, this alternative programme of not taxing productive labour would incentivise workers. With no taxes on labour income, generous pensions for everyone, and reduced stress from powerful monopolists, labour is likely to become more productive and enjoy work more. Indeed, the self-employment opportunities in Georgist economy will likely create a workers’ market in which employers would have to significantly improve the conditions of work (George Citation1885).

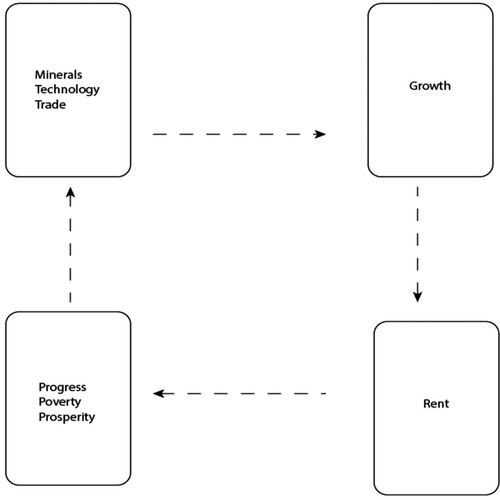

A schematic representation of the elements of a Georgist perspective is presented in .

3. Unequal Power

The analysis of trade is a useful starting point to illustrate what can be gained from a Georgist examination of unequal power. Doing so requires an explanation of why George questioned protectionism and presenting his alternative. For George (Citation1886[1991]), protectionism is flawed for five reasons. First, protectionism leads to beggar-thy-neighbour problems, and creates hostility rather than co-operation. Second, by taxing products,Footnote1 protectionism penalises production and human exertion. Third, protectionism excludes the taxation of land value created by monopolies in land and, hence, results in the private appropriation of socially created land value. Fourth, although George recognised that protection can create jobs, he argued that a better way to create jobs is to remove taxes on wages and to tax socially created land value instead. Finally, George argued that protectionism is rooted in erroneous conceptions about money (for a more detailed critical discussion on the concept and theories of money in economics, see Pressman Citation2000, Citation2021). While George argued that land was central to the development of the concept of money, protectionist theories give limited attention to the place of land.

George’s (Citation1886[1991], pp. 289–290) views provide grounds for a critique of globalisation and free trade today (Westbrook Citation2017). Under free trade theories, George argued, land is either a factor of production, another commodity, or both a factor and a commodity. For George, however, trade theory must be centred on the principle of equal right to land. The implication is that any transformation in land values arising from trade must be socialised. Privatising such rents by allowing them to accrue to landlords creates progress but only through impoverishment arising from gentrification. Privatising socially created rents through trade also arises in the form of the foreign and corporate extraction of minerals in the Global South without sharing the resulting rents with the South.

The Georgist perspective highlights the social and ecological costs arising from the abuse of the equal rights to land principle. Problems are most acute where those who own land do not have any social connection with the land and need not care about the social role of land. In general, all they need is a property title. This tendency is the outcome of a combination of solvency, time pressure, and profiteering (van Griethuysen Citation2012). Solvency requires that every traded item be treated as a commodity valued in money terms. Time pressure entails that speed of both production and consumption are key to the running of the system, pushing aside groups such as Indigenous peoples with a different conception of time. Profiteering entails the persistent pursuit of profit by all means.

According to GPE, free trade, creates a structural tendency towards inequality. Not only does it generate more social problems, it also generates widespread environmental degradation. These problems arise from the activities of land monopolists who take land from the commons, the public, and religious land, while actively seeking to prevent others from obtaining land and its resulting rent (Haila Citation2011; Christophers Citation2019; Obeng-Odoom Citation2020a, Citation2021). Inequalities become worse because the fruits of labour are squeezed by an ever-increasing rent which, in turn, provides disincentive to work, to innovate, and to flourish. On the flip side, the desire to monopolise land leads to gentrification, and speculation. Both lead to the destruction of nature. When nature is turned into a large factory for private gain, it usually becomes degraded. With free trade, the environment counts for little or nothing. Denying ecological limits to economic growth and limits to inequality generates deleterious effects for the environment (Daly, Cobb, and Cobb Citation1994; Obeng-Odoom Citation2020a, Citation2021). Even advocates of fair trade tend to ignore these fundamental concerns. Primarily centred on giving poorer nations preferential access to global markets, fair trade advocates would leave the system of property and rent under free trade unchanged (for a review of fair-trade literature, see Valiente-Riedl Citation2017). For GPE, neither free trade nor fair trade provides an adequate basis for progress (Obeng-Odoom Citation2017a, Citation2020c).

Problems also arise with technological change. Its usual effect is to increase land rent over a long period of time because technological innovation, adoption, and diffusion usually drive economic growth (Romer Citation1990, Citation2018). As ‘a mirror of economic transformation’, land rent increases, too, when the economy grows (Haila Citation1988, p. 79). In turn, landlords are able to extract more and more rent from labour while the labour share of the surplus generated in the production process fall. So, as technology makes it increasingly easy to access various parts of the city, workers and citizens have to be housed in slum-like conditions. While finding more work through the expansion of the economy, workers become worse off as they pay proportionately more of their wages as rent. Landlords, on the other hand, can speculate on land and monopolise the benefits of technology through extracting increasingly more rent. These landlords control not only where people sleep, but also what people have left over to feed themselves and their families. They control the destiny of future generations and the future of the urban economy, as they shape how much land is available, where it is, and how it could be used for development. In the hands of the landlords is the power to shape famine, economic depression and inequality in society.

This dynamic intensifies whenever a new technology is introduced in the city, such as when roads are built, when railway lines are constructed, when high-tech shopping centres are produced, or when new factories are opened. It follows that the future of our cities is quite bleak, not because humans use machines, but because urban land tenure system is designed in such a way that the benefits of using the machines are appropriated by landlords. These circumstances create progress for a few and poverty for many (George Citation1935; Kelly Citation1981, pp. 299–300).

To achieve progress without poverty, George (Citation1886[1991]) proposed a policy of ‘true free trade’. This requires removing all taxes on goods going into and out of countries (except those imposed for public morals, health, and safety) whether they are intended for revenue generation or for protecting local markets. More fundamentally, what makes free trade truly free is the taxation of the value of land to prevent the private appropriation of socially created rent and the removal of taxes from the wages of labour. George (Citation1886[1991]) thought that true free trade would bring about a fair distribution of resources, while encouraging labour to freely produce and exchange.

George’s free trade is based on internationalism, where many nation-states (rather than transnational corporations) make trade policy rather than one powerful nation or a cartel of large global firms. Two principles of true free trade make George’s ideas distinct from other trade theories: ‘That all men have equal rights to the use and enjoyment of the elements provided by Nature’ and ‘That each man has an exclusive right to the use and enjoyment of what is produced by his own labor’ (George Citation1886[1991], p. 280; see also George Citation1892[1981], p. 217; George Citation1883[1981], Ch. 5; Petrella Citation1984; Backhaus and Krabbe Citation1988; Obeng-Odoom Citation2020c).

As such, GPE provides a critique of Western-centric development economics and an alternative to mainstream development policy. Yet, GPE remains marginalised in development studies. Major surveys of the key currents in development economics (Szentes Citation2005; Akbulut, Adaman, and Madra Citation2015) give it little or no attention. It is important to understand why progress developing non-Western development economics has been so slow.

4. Obstacles to Progress

As various studies (see column 4 of ) show, there are diverse impediments to GPE. provides an overview.

Table 1. Impediments to Georgist political economy.

Consider the property lobby — landlords and developers of shopping centres, residential, and other properties. This propertied class seeks to influence state policy to benefit their interests (Haila Citation2016; Wang Citation2019), rather than the common good that GPE strives to advance. Big landlords, who extract rents from their investments, may engage in land grabbing and speculative property development, usually under the guise of creating jobs, supporting the economy, or driving green transformation (Molotch Citation1976). Politicians in Rwanda who have significant investment in landed property have become a major property lobby, blocking attempts at socialising urban land rent (Goodfellow Citation2017). Similar processes are evident in other rural and urban contexts in Africa (Nyantakyi-Frimpong and Bezner-Kerr Citation2017; Nyantakyi-Frimpong Citation2020). Indeed, even smaller landlords with a couple of investments in landed property worry about the consequences of an ascendant GPE. A yet broader array of homeowners, who live in gated or non-gated estates, constitute a collective property lobby with considerable power over the housing question, the size and form of rent, and how the rental relation is varied in their favour (Owusu-Ansah et al. Citation2018).

This property lobby also influences the ‘property mind’ (Haila Citation2017). Universities, real estate professional bodies that accredit economics courses, and individual teachers wield considerable power in influencing students away from GPE. Indeed, GPE seldom finds a significant place in the curriculum. This is explicable in terms of the close relationship between property developers, the class of academics who double as speculators and real estate investors, while seeking to make private property in land look natural in their courses on real estate finance. The well-documented effects of such courses are to slow down the uptake of GPE and to keep students ignorant or limiting their access to critical insights from GPE (Gaffney Citation1994; Haila Citation1988, Citation2017; Obeng-Odoom Citation2016b, Citation2017a).

The property lobby and the property mind are also part of the wider institutional impediments to the further adoption of GPE. Consider the creation, defence, and extension of private property on a global scale. The World Bank, for instance, provides significant funding to de-collectivise African land tenure systems. World Bank conferences on ‘land and development’ might give the impression of pluralist engagement, but the Bank’s systematic financing of land administration programmes aimed at making relations to land transactionary reveal the Bank’s own interest in defending and extending the global institution of private property rights in land. Whether via rural or urban development, free or fair trade, the institutions that have promoted the commodification of land (the media, sector agencies and the empire church), have played important roles in inhibiting the uptake of GPE (Obeng-Odoom Citation2020a, Citation2021). Together, such institutions complement the property lobby and the property mind in seeking to bury GPE.

also points to how Georgist political economists have attempted to overcome these obstacles. In general, vested interests can be addressed by exposure, while ideological interests can be challenged through critique, social action and social movements, seeking to provide alternatives (Stilwell Citation2019, pp. 231–245). Evidence from student surveys (Obeng-Odoom Citation2017b, Citation2019) shows that it is both possible and desirable to redevelop a political economic mindset in which GPE can flourish if taught alongside other institutionalist approaches (Obeng-Odoom Citation2017b, Citation2019).

More can be done in terms of developing the GPE approach to understanding social movements that challenge institutional impediments. In the context of the present obstacles, that would mean directly addressing the property lobby, carefully demonstrating alternatives to private and monopolistic land tenure systems, and showing greater sensitivity to local contexts. This is precisely what George did. He engaged the prevailing ideas of the times. Georgist political economists also directly engaged workers. Boycotts, protests, and demonstrations were some of the most powerful keys of Georgism and its political organisation, The United Labor Party (O’Donnell Citation2015, pp. 146–147).

Modern Georgist political economists have been less successful in achieving broad popular support. They have not worked closely with Indigenous groups nor organised workers. They have not shown an understanding of the complexities of diverse states. Yet the crises of development economics, and the demonstration (van Griethuysen Citation2012; Obeng-Odoom Citation2021) that private property in land is a major driver of current socio-ecological crises, should stir interest in a Georgist alternative.

At the very least, there is a case for re-engaging with GPE. Focal points could include popularising its concepts such as rents and unearned income in development economics, systematic application to contemporary social problems, and the development of stronger links between the Georgist tradition and the various land economics and development studies/economics programmes around the world. A more fundamental goal would be to develop a popular basis for Georgist ideas and policies, for example, among workers, farmers, and the landless (O’Donnell Citation2015, pp. 153–154). Clear communication, aimed not just at the intelligentsia but also at working people, should be the cornerstone. Developing alternative institutions, such as the commons, and paying attention to land in a Georgist manner (Haila Citation2011, Citation2018; Obeng-Odoom Citation2020b) would be other strategies.

Politically, Georgist political economists need to build alliances. In academia, one possibility is to strengthen the link between GPE and the original institutional tradition in economics. Many institutional economists, including Commons, began as Georgist political economists. As J.D. Chasse’s (Citation2017, p.1) biography of Commons notes: ‘In 1883 John R. Commons … started reading Henry George. … It would influence [him]’. Georgist political economists can also work with non-Western feminists who, unlike mainstream feminists, research agrarian structures, property-based urban inequalities arising from women’s unequal access to and control of land (e.g. Amanor-Wilks Citation2009; Kea Citation2010) and the intersectional inequalities that limit the economic advancement of blacks and women, especially black women (Crenshaw Citation1989).

So there is a strong case for Georgist political economists to embrace stratification economics and the political economy of race relations, racial discrimination, and racial privilege (see Obeng-Odoom Citation2020b). An even stronger alliance can be developed with postcolonial analysts (Spivak Citation1988; Chambers and Curti Citation2006; Ashcroft, Griffiths, and Tiffin Citation2013; Raja Citation2019). Marxism has struggled to develop this alliance, as shown by the recent heated debate between Vivek Chibber, Spivak, and other postcolonial writers on the pages of Postcolonial Theory and the Specter of Capital (Chibber Citation2013) as well as The Debate on Postcolonial Theory and the Specter of Capital (Warren Citation2016). Dipesh Chakrabarty’s (Citation2011) famous question, ‘can political economy be postcolonial?’ signals the tensions. The issue is less about whether postcolonialism takes economics seriously (Pollard, McEwan, and Hughes Citation2011) than about the sort of economic analysis employed.

GPE can provide a way forward. Its explicit recognition of Indigenous land tenure systems, values and principles is one basis for progress. Its radical challenge to slavery and a world monopolised by a few transnational corporations often located in Western societies is another. The Georgist support for an alternative system in which economic and ecological reparations play a transitory role is a third. Above all, its strong commitment to respect land and the environment make GPE a candidate likely to succeed in creating a rapprochement with postcolonial studies. The recent publication of major books, comments and reviews drawing on GPE (Bryson Citation2011; Cleveland Citation2012; O'Donnell Citation2015; Pullen Citation2015; Stilwell Citation2016; Giles Citation2016; Haila Citation2016; Obeng-Odoom Citation2016b, Citation2020a, Citation2020b, Citation2021; Ryan-Collins, Lloyd, and Macfarlane Citation2017; Harrison, Citation2021) suggests the possibility of GPE as a formidable alternative approach to development economics.

5. Conclusion

GPE addresses the challenge Keynes (Citation1926[1978], p. 311) posed to economists and humankind: to reconcile economic efficiency, social justice, individual liberty, and sustainable development. This article has shown that GPE can do this and also help analyse unequal geographies of development, unequal power, and impediments to scientific progress.

Moreover, GPE offers an alternative to Western development economics. This paper has set out the alternative path provided by GPE and identified its key contributions. First, GPE addresses contemporary development challenges that cannot be adequately dealt with by Western-centric development economics. Second, GPE highlights the importance of land and location values for current concerns about inequality, poverty, and sustainability when developing an alternative development agenda. Third, GPE provides many examples that demonstrate its practical potential for drawing insights from the Global South, developing Southern analyses, recognising Southern voices, and embracing Southern pathways to development.

GPE represents a threat to existing interests and currents of thought in hegemonic Western development economics. Accordingly, it faces formidable obstacles — from the property lobby, conventional attitudes to landed property, and institutions of private property in land.

Acknowledgements

I gratefully acknowledge the learned comments and constructive criticisms by two external referees for the Review of Political Economy and by Steve Pressman. I also appreciate the helpful suggestions from Ronald Johnson, the Editor of Good Government: A Journal of Political, Social, and Economic Comment. They are alI absolved of any problems with this paper. I gratefully acknowledge Academy of Finland funding for the Urban Land Tenure project (decision number: 320239), of which this paper is a part.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Note that, although taxes are not the only form of protectionism, George’s critique pays particular attention to taxation.

References

- Abdulai, R., and I. Ndekugri. 2007. ‘Customary Landholding Institutions and Housing Development in Urban Centres of Ghana: Case Studies of Kumasi and Wa.’ Habitat International 31: 257–267.

- Acemoglu, D., and J. Robinson. 2012. Why Nations Fail. New York: Crown Business.

- Agyeman, J. 2013. Introducing Just Sustainabilities: Policy, Planning, and Practice. London: Zed Books.

- Alchian, A., and H. Demsetz. 1973. ‘The Property Right Paradigm.’ Journal of Economic History 33 (1): 16–27.

- Akbulut, B., F. Adaman, and Y. M. Madra. 2015. ‘The Decimation and Displacement of Development Economics.' Development and Change 46 (4): 733–761. doi:10.1111/dech.12181.

- Amanor-Wilks, D. 2009. ‘Land, Labour and Gendered Livelihoods in a “Peasant” and a “Settler” Economy.’ Feminist Africa 12: 31–50.

- Arndt, W. 1987. ‘Economic Development: The History of an Idea.' London: University of Chicago Press.

- Asante, S. K. B. 1975. Property Law and Social Goals in Ghana, 1844–1966. Accra: Ghana Universities Press.

- Ashcroft, B., G. Griffiths, and H. Tiffin. 2013. Postcolonial Studies: The Key Concepts. London: Routledge.

- Backhaus, J. G., and J. J. Krabbe. 1988. ‘Henry George's Theory and an Application to Industrial Siting.’ International Journal of Social Economics 15 (3/4): 103–119.

- Bansah, D. K. 2017. ‘Governance Challenges in Sub-Saharan Africa: The Case of Land Guards and Land Protection in Ghana.’ Doctor of International Conflict Management Dissertations School of Conflict Management, Peacebuilding and Development.

- Bryson, P. J. 2011. The Economics of Henry George: History’s Rehabilitation of America’s Greatest Early Economist. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Chakrabarty, D. 2011. ‘Can Political Economy Be Postcolonial? A Note.’ In Postcolonial Economies, edited by J. Pollard, C. McEwan, and A. Hughes. London: Zed Books.

- Chambers, I., and L. Curti. 2006. The Postcolonial Question. London: Routledge.

- Chang, H.-J. 2002. Kicking Away the Ladder – Development Strategy in Historical Perspective. London: Anthem Press.

- Chasse, J. D. 2017. A Worker’s Economist: John R. Commons and His Legacy from Progressivism to the War on Poverty. London: Routledge.

- Chibber, V. 2013. Postcolonial Theory and the Specter of Capital. London: Verso.

- Christophers, B. 2019. The New Enclosure: The Appropriation of Public Land in Neoliberal Britain. London and New York: Verso.

- Cleveland, M. M. 2012. ‘The Economics of Henry George: A Review Essay.’ American Journal of Economics and Sociology 71 (2): 498–511.

- Cobb, C. 2016. ‘Editor’s Introduction: Fighting for Rural America: Overcoming the Contempt for Small Places.’ American Journal of Economics and Sociology 75 (3): 569–588.

- Collier, P., and A. J. Venables. 2012. ‘Greening Africa? Technologies, Endowments and the Latecomer Effect.’ Energy Economics 34 (Nov): s75–s84.

- Commons, J. R. 1924/1925. ‘Law and Economics.’ Yale Law Journal 34: 371–382.

- Commons, J. R. 1924[2012]. Legal Foundations of Capitalism. New York: Macmillan.

- Commons, J. R. 1934[1990]. Institutional Economics: Its Place in Political Economy. Vol 2. New Brunswick and London: Transaction Publishers.

- Crenshaw, K. 1989. ‘Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics.’ University of Chicago Legal Forum 8 (1): 139–167.

- Daly, H. E., and J. B. Cobb Jr., with contributions from C. W. Cobb. 1994. For the Common Good: Redirecting the Economy toward Community, the Environment, and a Sustainable Future. 2nd edition. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Darity Jr., W. 2008. ‘Forty Acres and a Mule in the 21st Century.’ Social Science Quarterly 89 (3): 656–664.

- Darity Jr., W. 2009. ‘Stratification Economics: Context Versus Culture and the Reparations Controversy.’ Kansas Law Review 57: 795–811.

- Darity Jr., W. A., and R. E. Triplett. 2008. ‘Ethnicity and Economic Development.’ In International Handbook of Development Economics, edited by A. K. Dutt, and J. Ros. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Darity Jr., W. A., D. Hamilton, and J. B. Stewart. 2015. ‘A Tour De Force In Understanding Intergroup Inequality: An Introduction to Stratification Economics.’ Review of Black Political Economy 42 (1–2): 1–6.

- de Soto, H. 2000. The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else. New York: Bantam Press.

- Domeher, D., R. Abdulai, and E. Yeboah. 2016. ‘Secure Property Rights as a Determinant of SME's Access to Formal Credit in Ghana: Dynamics Between Micro-Finance Institutions and Universal Banks.’ Journal of Property Research 33 (2): 162–188.

- Ehwi, R. J., N. Morrison, and P. Tyler. 2019. ‘Gated Communities and Land Administration Challenges in Ghana: Reappraising the Reasons why People move into Gated Communities.' Housing Studies. doi:10.1080/02673037.2019.1702927.

- Elabdin, E.-S. 2016. Economics, Culture, and Development. London: Routledge.

- Elahi, K. Q., and F. Stilwell. 2013. ‘Customary Land Tenure, Neoclassical Economics and Conceptual Bias.’ Niugini Agrisaiens 5: 28–39.

- Wright, E. 2010. ‘Envisioning real Utopias.' London: Verso.

- Field, E. 2007. ‘Entitled to Work: Urban Property Rights and Labor Supply in Peru.’ Quarterly Journal of Economics 122 (4): 1561–1602.

- Forstater, M. 2005. ‘Taxation and Primitive Accumulation: The Case of Colonial Africa.’ Research in Political Economy 22: 51–64.

- Fosu, A. 2010. ‘The Effect of Income Distribution on the Ability of Growth to Reduce Poverty: Evidence from Rural and Urban African Economies.’ American Journal of Economics and Sociology 69 (3): 1034–1053.

- Frank, G. 1966. ‘The Development of Underdevelopment.’ Monthly Review 18 (4): 17–31.

- Gaffney, M. 1994. ‘Neo-Classical Economics as a Stratagem Against Henry George.’ In The Corruption of Economics, edited by F. Harrison. London: Shepheard-Walwyn.

- Gaffney, M., and M. Goodall. 2016. ‘New Life for the Octopus: How Voting Rules Sustain the Power of California’s Big Landowners.’ American Journal of Economics and Sociology 75 (3): 649–680.

- Galbraith, J. K. 1979. ‘The Nature of Mass Poverty.' Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- George, H. 1878. ‘Moses – Apostle of Freedom.’ An address delivered by Henry George before the Young Men’s Hebrew Association of San Francisco, and then in many other places. accessed 27.08.2020. http://www.wealthandwant.com/HG/Moses.html.

- George, H. 1883[1966]. Social Problems. New York: Robert Schalkenbach Foundation.

- George, H. 1883[1981]. Social Problems. New York: Robert Schalkenbach Foundation. http://schalkenbach.org/library/henry-george/social-problems/spcont.html.

- George, H. 1884. Moses. London: The United Committee for Taxation of Land Values.

- George, H. 1885. ‘The Crime of Poverty.’ Accessed on 15.01.2019. http://schalkenbach.org/library/henry-george/hg-speeches/the-crime-of-poverty.html.

- George, H. 1886[1991]. ‘Protection or Free Trade: An Examination of the Tariff Question, with Especial Regard to the Interests of Labor.' New York: Robert Schalkenbach Foundation. http://schalkenbach.org/library/henrygeorge/protection-or-free-trade/preface-index.html

- George, H. 1891. The Condition of Labor: An Open Letter to Pope Leo XIII. New York: United States Book Company.

- George, Henry. 1892[1981]. A Perplexed Philosopher. New York: Robert Schalkenbach Foundation. http://www.schalkenbach.org/library/henry-george/perplexed-philosopher/0-Perplexed.html.

- George, H. 1898. The Science of Political Economy. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner and Co.

- George, H. 1935. Progress and Poverty. Fiftieth Anniversary Edition. New York: Robert Schalkenbach Foundation.

- Giles, R. 2016. The Theory of Charges on Common Land. Sydney: Association for Good Government.

- Goodfellow, T. 2017. ‘Taxing Property in A Neo-Developmental State: The Politics of Urban Land Value Capture in Rwanda and Ethiopia.’ African Affairs 116 (465): 549–572.

- Haila, A. 1988. ‘Land as a Financial Asset: The Theory of Urban Rent as a Mirror of Economic Transformation.’ Antipode 20 (2): 79–101.

- Haila, A. 2011. ‘The Comedy of the Suburban Commons: A Chinese Story.’ In Between Utopia and Apocalypse: Essays on Social Theory and Russia, edited by E. Kahla. Helsinki: Aleksanteri Institute.

- Haila, A. 2016. Urban Land Rent: Singapore as A Property State. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell.

- Haila, A. 2017. ‘Institutionalizing “The Property Mind”.’ International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 41 (3): 500–507.

- Haila, A. 2018. ‘Urban Land Tenure’. Helsinki: Academy of Finland.

- Hammond, F. N. 2008. ‘Marginal Benefits of Land Policies in Ghana.’ Journal of Property Research 25 (4): 343–362.

- Harrison, F. 2008. The Silver Bullet. London: The International Union for Land Value Taxation.

- Harrison, F. 2021. ‘# We Are Rent: Book 1 - Capitalism, Cannibalism, and How We Must Outlaw Free Riding.' London: Land Research Trust.

- Harvey, D. 2003. The New Imperialism. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Harvey, D. 2006. Spaces of Global Capitalism: Towards a Theory of Uneven Geographical Development. London and New York: Verso.

- Hill, P. 1986. ‘Development Economics on Trial: The Anthropological Case for a Prosecution.' Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kea, P. 2010. Land, Labour and Entrustment: West African Female Farmers and the Politics of Difference. Leiden: Brill.

- Kelly, J. M. 1981. ‘The New Barbarians: The Continuing Relevance of Henry George.' American Journal of Economics and Sociology 40 (3): 299–308.

- Keynes, J. 1926[1978]. ‘Liberalism and Labour.’ In The Collected Writings of John Maynard Keynes, edited by E. Johnson, and D. Moggridge. London: Royal Economic Society.

- Leo XIII, P. 1891. ‘Encyclical Letter of Pope Leo XIII on The Condition of Labor.’ In The Condition of Labor: An Open Letter to Pope Leo XIII, edited by H. George H. New York: United States Book Company.

- Leonard, T. C. 2016. Illiberal Reformers: Race, Eugenics and American Economics in the Progressive Era. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

- Lewis, W. A. 1953. Report on Industrialisation and The Gold Coast. Accra: The Government Printing Department.

- Lewis, W. A. 1954. ‘Economic Development with Unlimited Supplies of Labour.’ The Manchester School 22 (2): 139–191.

- Lewis, W. A. 1965. Politics in West Africa. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Lewis, W. A. 1979. ‘The Dual Economy Revisited.’ The Manchester School 47 (3): 211–229.

- Lewis, W. A. 1985. Racial Conflict and Economic Development. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Liberti, S. 2013. Land Grabbing: Journeys in the New Colonialism. London and New York: Verso.

- Lipton, M. 1977. Why Poor People Stay Poor: Urban Bias in World Development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Lipton, M. 2020. ‘Land Reform Contexts: Demography/Employment, Farms, Soil-Water Resources/Authority.’ In Rethinking Land Reform in Africa: New Ideas, Opportunities and Challenges, edited by C. M. O. Ochieng. Abidjan: African Development Bank.

- Manji, A. 2006. The Politics of Land Reform in Africa: From Communal Tenure to Free Markets. London: Zed Books.

- Mkandawire, T. 2015. ‘Neopatrimonialism and the Political Economy of Economic Performance in Africa: Critical Reflections.’ World Politics 67 (3): 563–612.

- Molotch, H. 1976. ‘The City as a Growth Machine: Toward a Political Economy of Place.’ American Journal of Sociology 82 (2): 309–332.

- Njoh, A. 2003. ‘Urbanization and Development in Sub-Saharan Africa.’ Cities 20 (3): 167–174.

- Nyantakyi-Frimpong, H. 2020. ‘What Lies Beneath: Climate Change, Land Expropriation, and Zaï Agroecological Innovations by Smallholder Farmers in Northern Ghana.’ Land Use Policy 92 (104469): 1–11.

- Nyantakyi-Frimpong, H., and R. Bezner-Kerr. 2017. ‘Land Grabbing, Social Differentiation and Food Security in Northern Ghana.’ Journal of Peasant Studies 44 (2): 421–444.

- O’Donnell, E. T. 2015. Henry George and the Crisis of Inequality: Progress and Poverty in The Gilded Age. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Obeng-Odoom, F. 2009. ‘The Political Economy of Urban Policies.’ The ICFAI University Journal of Urban Policy 4 (1): 7–20.

- Obeng-Odoom, F. 2013. Governance for Pro-Poor Urban Development: Lessons from Ghana. London: Routledge.

- Obeng-Odoom, F. 2014. Oiling the Urban Economy: Land, Labour, Capital, and the State in Sekondi-Takoradi, Ghana. London: Routledge.

- Obeng-Odoom, F. 2015. ‘Africa: On the Rise But to Where?' Forum for Social Economics 44 (3): 234–250.

- Obeng-Odoom, F. 2016a. ‘Understanding Land Reform in Ghana: A Critical Postcolonial Institutional Approach.’ Review of Radical Political Economics 48 (4): 661–680.

- Obeng-Odoom, F. 2016b. Reconstructing Urban Economics: Towards a Political Economy of The Built Environment. London: Zed Books.

- Obeng-Odoom, F. 2017a. ‘Teaching Political Economy to Students of Property Economics: Mission Impossible?' International Journal of Pluralism and Economics Education 8 (4): 359–377.

- Obeng-Odoom, F. 2017b. ‘Unequal Access to Land and the Current Migration Crisis.’ Land Use Policy 62: 159–171.

- Obeng-Odoom, F. 2019. ‘Pedagogical Pluralism in Undergraduate Urban Economics Education.’ International Review of Economics Education 31: 1–10.

- Obeng-Odoom, F. 2020a. ‘Dying For Sustainability?’ Voices for Sustainability. Accessed 28.08.2020. https://blogs.helsinki.fi/voices-for-sustainability/covid-19-dying-for-sustainability/#more-862.

- Obeng-Odoom, F. 2020b. Property, Institutions, and Social Stratification in Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Obeng-Odoom, F. 2020c. ‘The African Continental Free Trade Area.’ American Journal of Economics and Sociology 79 (1): 167–197.

- Obeng-Odoom, F. 2021. The Commons in An Age of Uncertainty: Decolonizing Nature, Economy, and Society. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Obeng-Odoom, F., Y. A. Elhadary, and H. S. Jang. 2014. ‘Living behind the Wall and Socio-Economic Implications for Those Outside the Wall: Gated Communities in Malaysia and Ghana.’ Journal of Asian and African Studies 49 (5): 544–558.

- Owusu-Ansah, A., D. Ohemeng-Mensah, R. T. Abdulai, and F. Obeng-Odoom. 2018. ‘Public Choice Theory and Rental Housing: An Examination of Rental Housing Contracts in Ghana.’ Housing Studies 33 (6): 938–959.

- Petrella, F. 1984. ‘Henry George's Theory of State's Agenda: The Origins of His Ideas on Economic Policy in Adam Smith's Moral Theory.’ American Journal of Economics and Sociology 43 (3): 269–286.

- Pollard, J., C. McEwan, and A. Hughes. 2011. Postcolonial Economies. London: Zed Books.

- Pressman, S. 2000. ‘A Note on Money and the Circuit Approach.’ Journal of Economic Issues 34 (4): 969–973.

- Pressman, S. 2021. ‘Rethinking the Theory of Money, Credit, and Macroeconomics: A Review Essay.’ Journal of Post Keynesian Economics 44 (2): 302–314.

- Pullen, J. 2015. Nature’s Gifts: The Australian Lectures of Henry George on the Ownership of Land and Other Natural Resources. Sydney: Desert Pea Press.

- Raja, M. 2019. ‘What is Postcolonialism?’ Postcolonial Space, April 2. Accessed 10.02.2020. https://postcolonial.net/2019/04/what-is-postcolonial-studies/.

- Robinson, J. 2006. Ordinary Cities: Between Modernity and Development. London: Routledge.

- Romer, P. M. 1990. ‘Endogenous Technological Change.’ Journal of Political Economy 98 (5): S71–S102.

- Romer, P. M. 2018. Prize Lecture. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/economic-sciences/2018/romer/lecture/.

- Rostow, W. W. 1959. ‘The Stages of Economic Growth.’ Economic History Review, New Series 12 (1): 1–16.

- Rowlandson, J. 1996. Landowners and Tenants in Roman Egypt: The Social Relations of Agriculture in the Oxyrbynchite Nome. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Ruben, R., A. D. Bekele, and B. M. Lenjiso. 2017. ‘Quality Upgrading in Ethiopian Dairy Value Chains: Dovetailing Upstream and Downstream Perspectives.’ Review of Social Economy 75 (3): 318–338.

- Ryan-Collins, J., T. Lloyd, and L. Macfarlane. 2017. Rethinking the Economics of Land and Housing. London: Zed Books.

- Sassen, S. 2014. Expulsions: Brutality and Complexity in the Global Economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Schultz, T. W. 1961. ‘Investment in Human Capital.’ American Economic Review 51 (1): 1–17.

- Spivak, G. C. 1988. ‘Can the Subaltern Speak?’ In Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, Edited by C. Nelson and L. Grossberg. London: Macmillan.

- Stilwell, F. 2000. Changing Track: A New Political Economic Direction. Sydney: Pluto Press.

- Stilwell, F. 2016. ‘Notes on ‘Nature’s Gifts: The Australian Lectures of Henry George on the Ownership of Land and Other Natural Resources.’ Journal of Australian Political Economy 76: 157–158.

- Stilwell, F. 2019. The Political Economy of Inequality. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Stilwell, F., and K. Jordan. 2004. ‘The Political Economy of Land; Putting Henry George in His Place.’ Journal of Australian Political Economy 54: 119–134.

- Szentes, T. 2005. ‘Development in the History of Economics.’ In The Origins of Development Economics: How Schools of Economic Thought Have Addressed Development, edited by K. S. Jomo, and E. S. Reinert. London: Zed Books.

- Tignor, R. L. 2006. W. Arthur Lewis and the Birth of Development Economics. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

- Todaro, M. P., and C. Smith. 2006. Economic Development. New York: Pearson Addison Wesley.

- Valiente-Riedl, E. 2017. ‘To be Free and Fair? Debating Fair Trade’s Shifting Response to Global Inequality.' Journal of Australian Political Economy 78: 159–185.

- van Griethuysen, P. 2012. ‘Bona Diagnosis, Bona Curatio: How Property Economics Clarifies the Degrowth Debate.’ Ecological Economics 84: 262–269.

- Veblen, T. 1923[2009]. Absentee Ownership: Business Enterprise in Recent Times: The Case of America. New Brunswick, NJ and London: Transactions Publishers.

- Wang, Y. 2019. Pseudo-Public Spaces in Chinese Shopping Malls: Rise, Publicness, and Consequences. London: Routledge.

- Warren, R. 2016. The Debate on Postcolonial Theory and the Specter of Capital. London: Verso.

- Westbrook, D. A. 2017. ‘Prolegomenon to a Defense of the City of Gold.' Real-World Economics Review 78: 141–147.