?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The global outbreak of COVID-19 has led to a normalization mode for preventing and controlling the spread of the epidemic. The way of life and work for both organizations and employees has undergone new changes, and the relationship between employees' risk perception and work engagement has attracted attention. Following the social-cognitive model of psychological stress and the resilience theory of positive psychology, by three-stage time-lag design, we obtain 285 questionnaires from employees of effective organizations in Mainland China. Regression analysis and bootstrap tests were conducted on SPSS and AMOS to verify the relevant hypotheses. The results showed that: (1) Employees' risk perception has a positive impact on work engagement; (2) Employees' risk perception has a negative impact on anxiety; (3) Anxiety plays a completely mediating role in the relationship between risk perception and work engagement; (4) Psychological resilience has a negative moderating effect on the relationship between risk perception and anxiety; (5) Psychological resilience has a negative moderating effect on the relationship between anxiety and work engagement. This research contributes to an improved understanding of the mechanism and boundary conditions of employee work engagement under conditions imposed by COVID-19 and provides a theoretical basis and practical guidance for organizations.

1. Introduction

Public health emergencies frequently disrupt normal social life and can pose significant threats to health and safety. Since the end of 2019, COVID-19 has swept the world as a highly infectious global pandemic, with a huge and ongoing impact on economic development and life around the world (Ahamad & Khan Pathan, Citation2021; Cheval et al., Citation2020; Wu et al., Citation2022; Zhang & Tai, Citation2022; Zheng et al., Citation2022).

According to the psychological stress theory proposed by Lazarus and Folkman (Citation1984), at times of a great crisis, people will produce a series of emotional, behavioural and physiological stress responses based on their individual cognitive assessment. Lack of awareness of epidemic risk among employees will lead to negative emotional responses such as anxiety (Šrol et al., Citation2021). Such responses increased markedly in the early stages of the epidemic, and happiness decreased. As epidemic prevention and control measures gradually became the norm, employees developed a more comprehensive understanding of the risks posed by the epidemic, thus reducing their anxiety. At the same time, dealing with epidemic risk will not only impact employees’ personal emotions, but also their behaviour, such as avoidance behaviour (Hai-Ti, Citation2015). Under the epidemic situation, employees will show negative behaviours due to risk reduction and protection of their own safety (Broekens et al., Citation2015; Dai et al., Citation2020; Du & Liu, Citation2015). At the same time, according to the risk perception-based social-cognitive model proposed by Lee and Lemyre (Citation2009), employees’ responses to emergencies are not only influenced by their own cognition and assessment, but are also restricted by situational factors. For example, the severity of the epidemic, the safety atmosphere of the organisation, and the government's epidemic intervention all regulate the employees’ response behaviour to emergencies (Papageorge et al., Citation2021; Riedel et al., Citation2021; Tian et al., Citation2020). Further research shows that when there is no way to solve an emergency, most employees choose escape as a coping strategy, thus affecting their engagement with their work (Bakker et al., Citation2014; Moos & Schaefer, Citation1993).

An organisation’s employees are its core asset and the centre of its creative potential. Improving the subjective initiative and active participation of employees is a key to an organisation’s effective response to the epidemic crisis, as well as a critical factor in creating and maintaining competitive advantage and sustainable development (Matthews & Shulman, Citation2005). In the face of an epidemic, employees maintaining active work engagement will have a positive impact on the employees, their teams and the overall organisation (Bakker & Albrecht, Citation2018). However, there is currently insufficient research on the impact of employees’ risk perception on their work engagement in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and thus, in the present paper, we try to address this research gap.

Emergency situations impact an individual’s emotional and behavioural responses. According to the social-cognitive model, individuals’ risk perception is correlated with behavioural intentions (Lee & Lemyre, Citation2009). From the perspective of this model, when employees face public health emergencies such as COVID-19, they may have negative emotional reactions such as anxiety and panic, as well as behavioural reactions such as avoidance behaviour or active engagement at work (Hai-Ti, Citation2015). The degree of work engagement refers to the performance of employees’ active participation in work (Gallagher, Citation2017). When employees are affected by cognitive, emotional or behavioural disturbances, the degree of work engagement will be affected (Bakker et al., Citation2011; Kundi et al., Citation2021; Taştan & Türker, Citation2014). As the indefinite risk of COVID-19, incomplete information regarding the severity of risks due to the epidemic will create psychological and emotional stress, likely resulting in negative psychological states (Etkin, Citation2009). Crisis conditions raise anxiety levels among employees, resulting in negative psychological states and behaviours in the workplace, such as reduced work enthusiasm and engagement (Lee et al., Citation2018). Therefore, during the epidemic, increased awareness of risk will effectively reduce anxiety and negative emotions, thus improving work productivity. Therefore, it can be inferred that employee anxiety may play a mediating role in the relationship between risk perception and work engagement, that is, anxiety may be an important mediating variable in the relationship.

The theory of psychological resilience indicates that individuals will positively adapt and quickly recover and respond to positive coping behaviours under pressure and adversity (Rutter, Citation1999). According to the theory, employees’ anxiety caused by the risk perception of COVID-19 will be moderated in a timely manner depending on their own mental resilience, allowing them to self-calm their anxiety, recover and even excel themselves (Dong et al., Citation2015). When employees’ anxiety affects their work engagement (Broekens et al., Citation2015), they will positively adapt according to their own psychological resilience, mobilising a positive attitude and available resources to reduce the negative impact of anxiety on work engagement and finally achieve their work requirements.

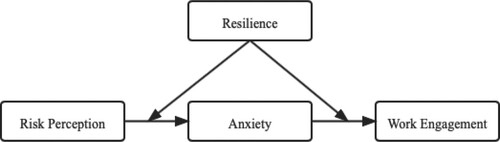

To sum up, based on the social-cognitive model and the theory of positive psychological resilience, this paper explores the impact of employees’ risk perception on work engagement in the context of COVID-19, and constructs a theoretical model with anxiety as a mediating variable and resilience as a moderating variable (Figure ).

Using this model, we will theoretically clarify the mediating mechanism and boundary conditions between risk perception and employee work engagement, explore the causal mechanism of work engagement and provide practical organisational guidance for maintaining employee work engagement in response to the COVID-19 epidemic.

2. Hypotheses developed

2.1. Risk perception and anxiety

The sudden outbreak and rapid spread of COVID-19 have taken a heavy toll on employees and organisations. Negative emotions such as anxiety and depression seriously affect organisational cohesion and development (Azoulay et al., Citation2020; Si-Jia et al., Citation2020). People respond to the epidemic according to their understanding of the risks involved (O'Neill et al., Citation2016; Rosenstock, Citation1974; Weinstein, Citation1988). According to the social-cognitive model proposed by Lee and Lemyre (Citation2009), employees’ perception of an outbreak will affect their mentality and emotions. When individuals are in a dangerous environment or face potential threats, they will experience anxiety and stress (Etkin et al., Citation2010). The risks posed by COVID-19, as well as the unknown, uncontrolled and severe nature of the outbreak, will create anxiety among employees (Trougakos et al., Citation2020).

Risk perception refers to the assessment of the nature, size, controllability and understandability of risks occurring in different situations, as well as the individual’s confidence in his/her ability to accurately assess such risks (Erdem & Swait, Citation2004; Forsythe & Shi, Citation2003; Sitkin & Pablo, Citation1992). Since the outbreak, information released on the official website of China’s National Health Commission has shown that, although the cumulative number of confirmed cases increased sharply during the lockdown stage in Wuhan, China, public panic was alleviated through strong national intervention and experts’ efforts to improve people's awareness of how to protect themselves from infection (Hagan et al., Citation2008). Thus, increased awareness of actual risk and effective mitigation measures will reduce employee anxiety (Ng et al., Citation2020). In the early stage of the outbreak, much of the public anxiety was due to the uncertainty of the situation (Pedrosa et al., Citation2008). Government, media and expert efforts to raise awareness effectively reduced employee anxiety (Labrague & De los Santos, Citation2020). From the perspective of result controllability, respondents indicated they felt the epidemic in China was largely under control, with the exception of imported cases. As society and the economy gradually emerge from the pandemic, employees feel that their efforts to protect themselves from infection are effective, thus reducing their anxiety (Cui et al., Citation2020; Dwivedi et al., Citation2020; Kaushik & Guleria, Citation2020). Therefore, we propose the first hypothesis as follows:

Hypothesis 1: Employees’ risk perception due to epidemic conditions has a significant negative impact on anxiety.

2.2. Risk perception and work engagement

Work engagement refers to the employee's psychological identification with the work and takes work performance as a reflection of the employee's sense of values (Kahn, Citation1990). Rich et al. (Citation2010) measured the emotion, cognition and physiology of work engagement as proposed by Kahn (Citation1990), the results showing that people could significantly develop their physiology, cognition and emotions by immersing themselves in their work roles. Employees will reflect different levels of work engagement based on different psychological states (Yalabik et al., Citation2013). According to the social-cognitive model of risk perception, an emergency can affect an individual's behavioural response, so the relationship between risk perception and behavioural intention is emphasised (Lee & Lemyre, Citation2009). In enterprises, managers seek to promote behaviours beneficial to organisation’s development. Work engagement is regarded as a benign mobilisation of work enthusiasm, involving physical, cognitive and emotional aspects (Taştan & Türker, Citation2014). When employees fully understand and perceive the extent of possibility, uncertainty and controllability inherent in epidemic risk, they will experience a sharp increase in confidence for economic recovery and development, which in turn gives them confidence and motivation to perform positively at work and increase their work engagement (Bakker et al., Citation2008). Therefore, we propose the second hypothesis as follows:

Hypothesis 2: Employees’ risk perception due to epidemic conditions has a significant positive impact on work engagement.

2.3. Mediating role of anxiety

Similarly, according to the social-cognitive model based on risk perception proposed by Lee and Lemyre (Citation2009), after an epidemic outbreak, the infectivity risk will affect employees’ psychological state and emotions, resulting in anxiety and panic. However, as public understanding of the epidemic deepens and national prevention measures are implemented, these negative emotions will gradually recede. In addition, employees’ anxiety will lead to negative behaviours and reduce work engagement (Lee et al., Citation2018). When employees feel anxious, their work efficiency will suffer (Lee et al., Citation2018). Negative emotions leave employees unable to concentrate, thus reducing their work engagement (Ojo et al., Citation2021). However, with full awareness of the risks posed by an epidemic, employees will be less anxious, and thus more productive. Combined with the psychological pathway “cognition–emotion-behaviour”, COVID-19 risk perception affects emotions, and such emotional changes can lead to changes in work behaviour. In view of this, we propose a third hypothesis as follows:

Hypothesis 3: Employees’ anxiety plays a mediating role in the relationship between risk perception caused by epidemic conditions and work engagement.

2.4. Moderating role of psychological resilience

Psychological resilience refers to the ability of employees to moderate their mentality, recover quickly and surpass previous performance to achieve success in the face of difficulties, conflicts and setbacks. Positive psychological resilience theory suggests that a positive mental state will affect employees’ work behaviour, work motivation and work performance (Wu & Zhang, 2017). In the face of difficulties, conflicts and pressures, employees with strong psychological resilience are better able to moderate their mentality, overcome negative thoughts, return to a positive working state, learn lessons from difficulties and show higher work engagement and organisational identity (Fredrickson, Citation2001). Under epidemic conditions, employees with strong psychological resilience will dynamically moderate their psychological state to actively overcome anxiety caused by the perception of epidemic risk. Employees with psychological resilience will have more confidence to overcome negative emotions and recover to a positive psychological state. The more complete one’s understanding of epidemic risk, the less anxiety one will feel. People with greater resilience can more effectively moderate their emotions and attitudes to eliminate negative emotions and anxiety caused by epidemic conditions. In view of this, we propose the fourth hypothesis as follows:

Hypothesis 4: Psychological resilience has a significant negative moderating effect on the relationship between risk perception caused by epidemic conditions and anxiety. The stronger an employee’s psychological resilience, the weaker the negative relationship between risk perception caused by epidemic conditions and anxiety.

According to the theory of positive psychological resilience, as a positive emotion, psychological resilience can help employees quickly moderate and recover and face difficulties with a positive attitude (Wu & Zhang, 2017). Employees with psychological resilience are confident in the face of adversity and difficulties, and are more persistent and diligent in pursuing organisational and personal goals (Fredrickson, Citation2001). Existing research has shown that employees with psychological resilience have higher work engagement in the face of difficulties or setbacks. Britt et al. (Citation2001) also found that employees with psychological resilience are more engaged with their work. In addition, the work engagement of employees is significantly improved by implementing intervention measures designed to improve psychological resilience (Van Wingerden et al., Citation2017).

Employees with strong psychological resilience have full confidence in their own abilities, and are better at using their own advantages and resources to recover from crisis or difficulties. Existing research shows that employees with greater psychological resilience are more likely to use the information provided by their environment to actively evaluate their situation and seek positive solutions (Wu & Zhang, 2017). Therefore, we propose hypothesis 5 as follows:

Hypothesis 5: Psychological resilience has a significant negative moderating effect on the relationship between employee anxiety and work engagement. The stronger the employee's psychological resilience, the weaker the negative influence on the relationship between employee anxiety and work engagement.

Hypotheses 3, 4 and 5, respectively, posit that anxiety plays a mediating role in the relationship between risk perception and work engagement, that psychological resilience has a significant negative moderating effect on the relationship between risk perception and anxiety and that psychological resilience has a significant negative moderating effect on the relationship between employee anxiety and work engagement. Therefore, we further propose that psychological resilience negatively moderates the mediating effect of anxiety on the relationship between risk perception caused by epidemic conditions and work engagement. Specifically, employees with high psychological resilience face risks with a more positive attitude and less negative anxiety, so the impact of risk perception caused by epidemic conditions on anxiety is relatively less. Meanwhile, such employees adjust their approach to work with a more positive attitude, and anxiety has less of a pronounced effect on their work engagement. Employees with low psychological resilience have difficulty making mental adjustments when facing epidemic risk, and cannot respond positively to resulting changes. Such employees suffer greater anxiety as a result of epidemic risk perception, and there is a greater impact on work engagement. Therefore, we propose hypothesis six as follows:

Hypothesis 6: Employees’ psychological resilience negatively moderates the mediating effect of anxiety on the relationship between risk perception and work engagement. The higher the employees’ psychological resilience, the stronger the mediating effect of anxiety on the relationship between risk perception and work engagement.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data collection

During the COVID-19 epidemic a survey was distributed to potential respondents living in the Pearl River Delta, the Yangtze River Delta and the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region in China, along with Hunan and Hubei provinces. Respondents worked in business development, technology research and development, product design, production management and service departments of different enterprises. In the data sampling process, three people were assigned to a group for a unified investigation, and questionnaires are issued and collected together. The research investigator provided enterprise managers with detailed information regarding the research goals and survey content, answered questions from the managers, and asked managers to invite their employees to participate in the survey. Due to the epidemic, surveys were distributed and administered online, and respondents were asked to complete the questionnaire independently. The questionnaire was filled in anonymously, emphasising that the questionnaire information was only used for scientific research, so as to ensure that the respondents could answer with confidence and obtain more real data.

To avoid the influence of common method deviation, the questionnaire was administered in three thematic batches, each separated by an interval of one month. Employee risk perception was investigated in March 2020, followed in April by anxiety and psychological resilience and work engagement in May. Common demographic data were also collected including gender, age, educational level, marriage status, working term, etc.

Data were initially collected from 390 respondents, with a total of 285 valid responses, for a recovery rate of 73.08%. Among the employees surveyed, 131 (45.96%) were male, 142 (49.82%) were unmarried, the average age was 32.66 years, the average length of service was 7.51 years and the average education level is above the junior college level.

3.2. Variable measurement

To ensure questionnaire reliability and validity, the existing maturity scale was used for reference, using standard translation and back-translation procedures to render the survey in Chinese with repeated consultations with the questionnaire delivery team (Brislin, Citation1986). All questionnaires used a 5-point Likert scale (from 1 “strongly disagree” to 5 “strongly agree”).

Risk perception: This section mainly refers to the 15-item scale developed by Dai et al. to measure risk perception of public health emergencies in terms of four aspects: possibility, severity, unpredictability and controllability (Dai et al., Citation2020). For example, for the item “COVID-19 is easily transmitted now”, Conbrach's α coefficient is 0.894.

Anxiety: The 20-item self-anxiety scale developed by Zung (Citation1971) was used to measure anxiety. For example, for the item “Recently, I’ve felt more nervous and anxious than usual”, Conbrach's α coefficient is 0.935.

Resilience: Siu et al. (Citation2009) developed a 9-item scale with samples from Mainland China and Hong Kong to measure resilience. For example, the item, “I have confidence in my ability to overcome current or future difficulties and solve possible difficulties or problems” had a Conbrach's α coefficient of 0.932.

Work engagement: The 18-item scale developed by Rich et al. (Citation2010) was used to measure work engagement in terms of three aspects: of emotion, cognition and physiology. For example, the item “I am very diligent at work” had a Conbrach's α coefficient of 0.910.

To prevent demographic variables from influencing the model results, gender, age and working years were controlled. The reliability of the four variables is shown in Table .

Table 1. Reliability of variables.

4. Data analysis

4.1. Common method bias analysis

To reduce the common method deviation, questionnaires were completed in three distinct stages, each respectively assessing employees’ risk perception, anxiety and psychological resilience. Because of the epidemic, many respondents worked from home, making it difficult for supervisors to directly observe and measure employees’ work engagement, the self-reporting questionnaires were used to investigate employees’ work engagement. Thus, the resulting data required testing for common method deviation. The Harman single-factor test was used to conduct factor analysis for all items, and the common factor number was set as 1, which explained 31.337% of variation (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003). There was no significant homology bias, and the relationship between variables was credible and did not seriously affect the overall results.

4.2. Confirmatory factor analysis

To test the discriminant validity of the variables involved, structural equation modelling was used for factor analysis to test the variables and the model. The analysis results are shown in Table . It can be seen that the four-factor model outperforms the other factor models in fitting the sample data, indicating that the questionnaire design has good discriminant validity. Confirmatory factor analysis was used to test the discriminative validity of each variable (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003). Therefore, the fitting index was selected to judge the fitting degree of the model. The chi-square difference must reach a significant level, the root mean square of approximate error (RMSEA) must be less than 0.08, and the comparative fitness index (CFI) and Tuck-Lewis’s index (TLI) must be greater than 0.9. The four factors represent four different constructs which can be used for regression analysis.

Table 2. Confirmatory factor analysis (N = 285).

4.3. Correlation analysis

To further clarify the relationship between employees’ risk perception, anxiety, psychological resilience and work engagement, correlation analysis was conducted on the relationships among all variables. The results are shown in Table . Correlation coefficients between variables in the hypothesis relationship are all significant (***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05), which provides support for hypothesis verification, but further analysis and testing are needed.

Table 3. Mean value, standard deviation and correlation coefficient of variables (N = 285).

4.4. Regression analysis

The multiple linear regression (Gao et al., Citation2021) and the Process method were used to analyse the relationship between employees’ risk perception, anxiety, psychological resilience and work engagement. Gender, age and tenure duration were taken as control variables, and the results are shown in Table .

Table 4. Regression analysis.

In Table , we find that the gender of employees has a significant impact on work engagement. Specifically, female employees are more engaged in work than male employees. At the same time, it is also found that the working years have a positive impact on work engagement. Specifically, the longer working years, the higher the degree of work engagement. In this study, age has no significant influence on work engagement. However, according to previous studies on work engagement, age of employees is taken as a control variable, because age of employees has a positive influence on work engagement (Schaufeli, Citation2012).

It can be seen from Model 3 in Table that, after controlling for employees’ demographic attributes, employees’ risk perception has a significant positive impact on work engagement (β = .115, P < 0.05), thus supporting Hypothesis 1. As can be seen from Model 1 in Table , after controlling for demographic attributes, risk perception has a significantly negative impact on anxiety (β = −.169, P < 0.01), thus supporting Hypothesis 2.

According to Model 4 in Table , after controlling for demographic attributes, anxiety has a mediating effect on the relationship between risk perception and work engagement (β = −.306, P < 0.001).

To further clarify the mediating effect, the bootstrapping method was used for testing, and the results are shown in Table .

Table 5. Bootstrap test of mediation effect.

As can be seen from Table , after controlling for demographic attributes, the indirect effect of anxiety is significant to the 95% confidence interval. The direct effect of risk perception on work engagement is not significant to the 95% confidence interval, indicating that anxiety plays a completely mediating role in the relationship between risk perception and work engagement, thus Hypothesis 3 is supported.

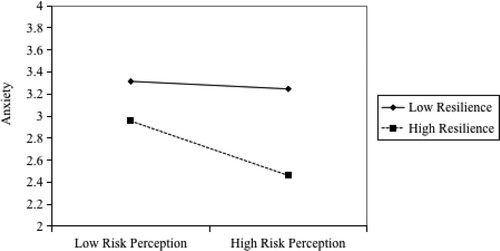

It can be seen from Model 2 in Table that, after controlling for demographic attributes, the interaction term of risk perception and psychological resilience has a negative impact on anxiety (β = −.125, P < 0.05), indicating that psychological resilience plays a moderating role in the relationship between risk perception and anxiety.

To explain this significant regulatory effect, the study utilises Aiken, West and Reno to adjust the level of the moderator variable by one standard deviation (±1 SD) above and below (plus or minus) the mean so as to give a full explanation (Aiken et al., Citation1991), and the results are shown in Figure . Higher psychological resilience is found to reduce the negative impact of risk perception on anxiety, thus supporting Hypothesis 4.

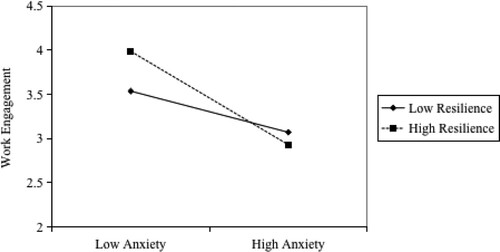

It can be seen from Model 5 in Table that, after controlling for demographic attributes, the interaction term of anxiety and psychological resilience has a negative impact on work engagement (β = −.128, P < 0.05). This result suggests that psychological resilience plays a moderating role in the relationship between anxiety and work engagement. To explain this significant regulatory effect more clearly, the study utilises Aiken, West and Reno to adjust the level of the moderator variable by one standard deviation (±1 SD) above and below (plus or minus) (Aiken et al., Citation1991), and the results are shown in Figure . Higher psychological resilience is found to be associated with a reduced negative impact of employee anxiety on work engagement, thus supporting Hypothesis 5.

To further test the moderated mediation effect, the bootstrapping method was used to test the moderated mediation model, and the analysis results are shown in Table .

Table 6. Indirect effects.

Table shows that, given high psychological resilience, the indirect effect value is 0.167, with a 95% confidence interval of [.045, .319]. Therefore, psychological resilience moderates the mediating effect of anxiety on the relationship between risk perception and work engagement, and the mediating effect is stronger when psychological resilience is high, thus supporting Hypothesis 6.

5. Theoretical contributions and practical applications

So far, in this paper, we have theoretically obtained the following results: (1) the clearer understanding employees have of contagion risk, prevention and control, the higher their work engagement under the COVID-19 spreading; (2) anxiety can reduce employee work engagement, and an inability to effectively improve working environment conditions will naturally sap work enthusiasm (Ojo et al., Citation2021); (3) anxiety can distract employees’ and reduce their enthusiasm for work, thus diminishing work engagement (Crawford et al., Citation2010); (4) employees with high levels of psychological resilience will autonomously adjust their inner emotions to cope with anxiety and recover work productivity.

According to these theoretical findings, in order to improve the organisational management under epidemic conditions, it is easy to see the following operations could be carried out in practice:

Helping employees to better understand epidemic risks.

Since employee epidemic risk perception has a positive impact on their work engagement, thus organisations should ensure employees having access to accurate and timely risk-related information which will enhance employee confidence for the duration of the epidemic and then improved work engagement.

Stabilise employees’ emotions so as to reduce the negative effects of anxiety.

Managers should be continuously aware of emotional changes among employees in a timely manner to effectively address the development of negative emotions in response to an epidemic with particular attention to the development of negative emotions such as anxiety. Meanwhile, the enterprises could organise some emotional catharsis activities to help employees release negative emotions and relieve anxiety.

Truly meet the needs of employee.

The COVID-19 epidemic has led to the shutdown of many enterprises, throwing many people out of work, a situation which is bound to trigger anxiety among even those who are still employed. Therefore, enterprises must maintain awareness of the onset and development of negative emotions among employees, and help them to address these emotions by enhancing their sense of achievement and work security. For example, enterprises can set goals that encourage team work, providing employees with a clear view of their contribution to enterprise sustainability and success (Rafiq & Chin, Citation2019). Managers can also assign more challenging tasks to increase individual employee sense of self-efficacy and stimulate improved work engagement (Rafiq et al., Citation2019).

Enhance employees’ psychological resilience and proactively address epidemic-related concerns.

During the epidemic, enterprises could carry out organisational activities to enhance psychological resilience, such as trainings and meetings interaction between high- and low-resilience employees in a way of raising overall resilience. Such individuals show better adaptability when encountering difficulties and setbacks being work-related under epidemic conditions (Rafiq et al., Citation2019), and better identifications with organisation as well.

6. Conclusion

This research explores issues from the social-cognitive theory of psychological stress, which not only enriches the application range of social-cognitive models, but also proposes new methods for empirical analysis of behavioural research. Hypothesis testing based on questionnaire data shows that risk perception has a significant positive impact on work engagement and anxiety is a complete mediator between risk perception and work engagement. Also, it is proved that psychological resilience has a significant negative moderating effect on the relationship between risk perception and employee anxiety while psychological resilience has a significant negative moderating effect on the relationship between employee anxiety and work engagement.

Meanwhile, with examining the proposed model of moderated mediating, it is demonstrated that moderating effect of employee psychological resilience are all positive on mediating effects of risk perception, anxiety and work engagement. In other words, for employees with high psychological resilience, the mediating effect of risk perception on work engagement is stronger through anxiety. There is no doubt that these interesting findings have strong implications for employees to overcome negative emotions, and so as to enhance the work engagement during COVID-19 and other epidemics.

Certainly, the study presented here provides valuable insight, it is subject to some limitations such as data survey collected from March to May in 2020, a time of the COVID-19 epidemic not being the most acute in China and vast majority of respondents were working online, which posed challenges for managers to assess employee performance directly in a timely manner, and it leads to the study relying on self-reporting by subjects. In addition, analysis conducted here, just from the employee perspective, ignored not only the influence of leadership on employee work engagement but also the influence of Government's Epidemic Prevention Policy.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ahamad, S. S., & Khan Pathan, A.-S. (2020). A formally verified authentication protocol in secure framework for mobile healthcare during COVID-19-like pandemic. Connection Science, 33(3), 532–554. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540091.2020.1854180

- Aiken, L. S., West, S. G., & Reno, R. R. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage.

- Azoulay, E., Cariou, A., Bruneel, F., Demoule, A., Kouatchet, A., Reuter, D., Souppart, V., Combes, A., Klouche, K., Argaud, L., Barbier, F., Jourdain, M., Reignier, J., Papazian, L., Guidet, B., Géri, G., Resche-Rigon, M., Guisset, O., Labbé, V., … Kentish-Barnes, N. (2020). Symptoms of anxiety, depression, and peritraumatic dissociation in critical care clinicians managing patients with COVID-19. A cross-sectional study. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 202(10), 1388–1398. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202006-2568OC

- Bakker, A. B., & Albrecht, S. (2018). Work engagement: Current trends. Career Development International, 23(1), 4–11. https://doi.org/10.1108/CDI-11-2017-0207

- Bakker, A. B., Albrecht, S. L., & Leiter, M. P. (2011). Key questions regarding work engagement. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 20(1), 4–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2010.485352

- Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Sanz-Vergel, A. I. (2014). Burnout and work engagement: The JD–R approach. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 389–411. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091235

- Bakker, A. B., Schaufeli, W. B., Leiter, M. P., & Taris, T. W. (2008). Work engagement: An emerging concept in occupational health psychology. Work & Stress, 22(3), 187–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370802393649

- Brislin, R. W. (1986). The wording and translation of research instruments. In W. J. Lonner & J. W. Berry (Eds.), Field methods in cross-cultural research (pp. 137–164). Sage Publications, Inc.

- Britt, T. W., Adler, A. B., & Bartone, P. T. (2001). Deriving benefits from stressful events: The role of engagement in meaningful work and hardiness. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 6(1), 53–63. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.6.1.53

- Broekens, J., Jacobs, E., & Jonker, C. M. (2015). A reinforcement learning model of joy, distress, hope and fear. Connection Science, 27(3), 215–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540091.2015.1031081

- Cheval, S., Mihai Adamescu, C., Georgiadis, T., Herrnegger, M., Piticar, A., & Legates, D. R. (2020). Observed and potential impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the environment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(11), Article 4140. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17114140

- Crawford, E. R., LePine, J. A., & Rich, B. L. (2010). Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout: A theoretical extension and meta-analytic test. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(5), 834–848. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019364

- Cui, S., Zhang, L., Yan, H., Shi, Q., Jiang, Y., Wang, Q., & Chu, J. (2020). Experiences and psychological adjustments of nurses who voluntarily supported COVID-19 patients in Hubei province, China. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 13, 1135–1145. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S283876

- Dai, Y., Wang, T., Wang, Z., & Xu, B. (2020). Effect of the crowdfunding description on investment decisions from the perspective of prosocial behaviour. International Journal of Embedded Systems, 13(4), 476–484. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJES.2020.110672

- Dong, Y. H., Chen, H., Qian, W. N., & Zhou, A. Y. (2015). Micro-blog social moods and Chinese stock market: The influence of emotional valence and arousal on Shanghai composite index volume. International Journal of Embedded Systems, 7(2), 148–155. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJES.2015.069987

- Du, Y., & Liu, H. (2020). Analysis of the influence of psychological contract on employee safety behaviors against COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(18), Article 6747. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186747

- Dwivedi, Y. K., Hughes, D. L., Coombs, C., Constantiou, I., Duan, Y., Edwards, J. S., Gupta, B., Lal, B., Misra, S., Prashant, P., Raman, R., Rana, N. P., Sharma, S. K., & Upadhyay, N. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on information management research and practice: Transforming education, work and life. International Journal of Information Management, 55, Article 102211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102211

- Erdem, T., & Swait, J. (2004). Brand credibility, brand consideration, and choice. Journal of Consumer Research, 31(1), 191–198. https://doi.org/10.1086/383434

- Etkin, A. (2009). Functional neuroanatomy of anxiety: A neural circuit perspective. Behavioral Neurobiology of Anxiety and its Treatment, 2, 251–277. https://doi.org/10.1007/7854_2009_5

- Etkin, A., Prater, K. E., Hoeft, F., Menon, V., & Schatzberg, A. F. (2010). Failure of anterior cingulate activation and connectivity with the amygdala during implicit regulation of emotional processing in generalized anxiety disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 167(5), 545–554. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09070931

- Forsythe, S. M., & Shi, B. (2003). Consumer patronage and risk perceptions in internet shopping. Journal of Business Research, 56(11), 867–875. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(01)00273-9

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218

- Gallagher, S. (2017). Theory, practice and performance. Connection Science, 29(1), 106–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540091.2016.1272098

- Gao, K., Chang, C. C., & Liu, Y. (2021). Predicting missing data for data integrity based on the linear regression model. International Journal of Embedded Systems, 14(4), 355–362. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJES.2021.117946

- Hagan, P., Maguire, B., & Bopping, D. (2008). Public Behaviour during a Pandemic. The Australian Journal of Emergency Management, 23(3), 35–40. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.439713209745293

- Hai-Ti, Q. (2015). Review of public risk perception model in emergent events. Journal of Intelligence, 34(5), 141–145. (in Chinese). https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1002-1965.2015.05.025

- Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, 33(4), 692–724. https://doi.org/10.5465/256287

- Kaushik, M., & Guleria, N. (2020). The impact of pandemic COVID-19 in workplace. European Journal of Business and Management, 12(15), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.7176/EJBM/12-15-02

- Kundi, Y. M., Sardar, S., & Badar, K. (2021). Linking performance pressure to employee work engagement: The moderating role of emotional stability. Personnel Review. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-05-2020-0313

- Labrague, L. J., & De los Santos, J. A. A. (2020). COVID-19 anxiety among front-line nurses: Predictive role of organisational support, personal resilience and social support. Journal of Nursing Management, 28(7), 1653–1661. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.13121

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer Publishing Company.

- Lee, J. E., & Lemyre, L. (2009). A social-cognitive perspective of terrorism risk perception and individual response in Canada. Risk Analysis: An International Journal, 29(9), 1265–1280. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2009.01264.x

- Lee, K., Duffy, M. K., Scott, K. L., & Schippers, M. C. (2018). The experience of being envied at work: How being envied shapes employee feelings and motivation. Personnel Psychology, 71(2), 181–200. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12251

- Matthews, J., & Shulman, A. D. (2005). Competitive advantage in public-sector organizations: Explaining the public good/sustainable competitive advantage paradox. Journal of Business Research, 58(2), 232–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(02)00498-8

- Moos, R. H., & Schaefer, J. A. (1993). Coping resources and processes: Current concepts and measures. In L. Goldberger, & S. Breznitz (Eds.), Handbook of stress: Theoretical and clinical aspects (pp. 234–257). Free Press.

- Ng, K., Poon, B. H., Kiat Puar, T. H., Shan Quah, J. L., Loh, W. J., Wong, Y. J., Tan T. Y., & Raghuram, J. (2020). COVID-19 and the risk to health care workers: A case report. Annals of Internal Medicine, 172(11), 766–767. https://doi.org/10.7326/L20-0175

- O'Neill, E., Brereton, F., Shahumyan, H., & Clinch, J. P. (2016). The impact of perceived flood exposure on flood-risk perception: The role of distance. Risk Analysis, 36(11), 2158–2186. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.12597

- Ojo, A. O., Fawehinmi, O., & Yusliza, M. Y. (2021). Examining the predictors of resilience and work engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability, 13(5), Article 2902. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052902

- Papageorge, N. W., Zahn, M. V., Belot, M., Broek-Altenburg, E. V. d., Choi, S., Jamison, J. C., & Tripodi, E. (2021). Socio-demographic factors associated with self-protecting behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Population Economics, 34(2), 691–738. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-020-00818-x

- Pedrosa, A. L., Bitencourt, L., Fróes, A. C. F., Cazumbá, M. L. B., Campos, R. G. B., de Brito, S. B. C. S., & Simões e Silva, A. N. (2020). Emotional, behavioral, and psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 2635. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.566212

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Rafiq, M., & Chin, T. (2019). Three-way interaction effect of job insecurity, job embeddedness and career stage on life satisfaction in a digital era. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(9), Article 1580. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16091580

- Rafiq, M., Wu, W., Chin, T., & Nasir, M. (2019). The psychological mechanism linking employee work engagement and turnover intention: A moderated mediation study. Work, 62(4), 615–628. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-192894

- Rich, B. L., Lepine, J. A., & Crawford, E. R. (2010). Job engagement: Antecedents and effects on job performance. Academy of Management Journal, 53(3), 617–635. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.51468988

- Riedel, B., Horen, S. R., Reynolds, A., & Jahromi, A. H. (2021). Mental health disorders in nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic: Implications and coping strategies. Frontiers in Public Health, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.707358

- Rosenstock, I. M. (1974). Historical origins of the health belief model. Health Education Monographs, 2(4), 328–335. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019817400200403

- Rutter, M. (1999). Resilience concepts and findings: Implications for family therapy. Journal of Family Therapy, 21(2), 119–144. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6427.00108

- Schaufeli, W. (2012). Work engagement: What do we know and where do we go? Romanian Journal of Applied Psychology, 14(1), 3–10.

- Si-Jia, L., Yi-Lin, W., Nan, Z., & Ting-Shao, Z. (2020). Social psychology influence by 2019-nCoV epidemic declaration: A study on active web users. [EB/OL] (in Chinese).

- Sitkin, S. B., & Pablo, A. L. (1992). Reconceptualizing the determinants of risk behavior. Academy of Management Review, 17(1), 9–38. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1992.4279564

- Siu, O. L., Hui, C. H., Phillips, D. R., Lin, L., Wong, T. W., & Shi, K. (2009). A study of resiliency among Chinese health care workers: Capacity to cope with workplace stress. Journal of Research in Personality, 43(5), 770–776. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2009.06.008

- Šrol, J., Ballová Mikušková, E., & Čavojová, V. (2021). When we are worried, what are we thinking? Anxiety, lack of control, and conspiracy beliefs amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 35(3), 720–729. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3798

- Taştan, S. B., & Türker, M. V. (2014). A study of the relationship between organizational culture and job involvement: The moderating role of psychological conditions of meaningfulness and safety. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 149, 943–947. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.08.306

- Tian, H., Liu, Y., Li, Y., Wu, C. H., Chen, B., Kraemer, M. U., Li, B., Cai, J., Xu, B., Yang, Q., Wang, B., Yang, P., Cui, Y., Song, Y., Zheng, P., Wang, Q., Bjornstad, O. N., Yang, R., Grenfell, B. T., … Dye, C. (2020). An investigation of transmission control measures during the first 50 days of the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Science, 368(6491), 638–642. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abb6105

- Trougakos, J. P., Chawla, N., & McCarthy, J. M. (2020). Working in a pandemic: Exploring the impact of COVID-19 health anxiety on work, family, and health outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(11), 1234–1245. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000739

- Van Wingerden, J., Derks, D., & Bakker, A. B. (2017). The impact of personal resources and job crafting interventions on work engagement and performance. Human Resource Management, 56(1), 51–67. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21758

- Weinstein, N. D. (1988). The precaution adoption process. Health Psychology, 7(4), 355–386. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.7.4.355

- Wu, S., Liu, Y., Zou, Z., & Weng, T. H. (2022). S_I_LSTM: Stock price prediction based on multiple data sources and sentiment analysis. Connection Science, 34(1), 44–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540091.2021.1940101

- Yalabik, Z. Y., Popaitoon, P., Chowne, J. A., & Rayton, B. A. (2013). Work engagement as a mediator between employee attitudes and outcomes. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(14), 2799–2823. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2013.763844

- Zhang, J., & Tai, Y. (2022). Secure medical digital twin via human-centric interaction and cyber vulnerability resilience. Connection Science, 34(1), 895–910. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540091.2021.2013443

- Zheng, Z., Zhou, Y., Sun, Y., Wang, Z., Liu, B., & Li, K. (2022). Applications of federated learning in smart cities: Recent advances, taxonomy, and open challenges. Connection Science, 34(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540091.2021.1936455

- Zung, W. W. (1971). A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics: Journal of Consultation and Liaison Psychiatry, 12(6), 371–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0033-3182(71)71479-0