ABSTRACT

In order to increase patient active engagement during patient–provider interactions, we developed and implemented patient training sessions in four antiretroviral therapy (ART) clinics in Namibia using a “Patient Empowerment” training curriculum. We examined the impact of these trainings on patient–provider interactions after the intervention. We tested the effectiveness of the intervention using a randomized parallel group design, with half of the 589 enrolled patients randomly assigned to receive the training immediately and the remaining randomized to receive the training 6 months later. The effects of the training on patient engagement during medical consultations were measured at each clinic visit for at least 8 months of follow-up. Each consultation was audiotaped and then coded using the Roter Interaction Analysis System (RIAS). RIAS outcomes were compared between study groups at 6 months. Using intention-to-treat analysis, consultations in the intervention group had significantly higher RIAS scores in doctor facilitation and patient activation (adjusted difference in score 1.19, p = .004), doctor information gathering (adjusted difference in score 2.96, p = .000), patient question asking (adjusted difference in score .48, p = .012), and patient positive affect (adjusted difference in score 2.08, p = .002). Other measures were higher in the intervention group but did not reach statistical significance. We have evidence that increased engagement of patients in clinical consultation can be achieved via a targeted training program, although outcome data were not available on all patients. The patient training program was successfully integrated into ART clinics so that the trainings complemented other services being provided.

Introduction

Namibia has made remarkable progress in the roll-out of antiretroviral therapy (ART) services to HIV-infected persons in need of treatment. The provision of ART in public sector health facilities in Namibia started in 2003 and a subsequent rapid scale-up of ART services has led to coverage approaching Universal Access targets (World Health Organization [WHO], Citation2013). According to a 2013 United Nations General Assembly Special Session on HIV/AIDS (Ministry of Health and Social Services [MOHSS], Citation2013) report, 87% of adults and 70% of children with advanced HIV infection (meeting World Health Organization (WHO) criteria of CD4 counts <350 cells/mm3) are receiving ART in Namibia: a total of 113,486 persons by mid-2013 (MOHSS, Citation2013).

With such rapid scale-up of services, the Namibia Ministry of Health and Social Services (MoHSS) is interested in the quality of HIV care and in understanding the factors associated with patient engagement in care. I-TECH (International Training and Education Center for Health) at the University of Washington has been working in Namibia since 2003 as a technical partner to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and MoHSS to support the roll-out of ART. Through close interactions with Namibian clinicians, leaders of HIV support groups and others, we became aware that ART patients in Namibia often do not actively engage with health-care providers during their clinical consultations. We hypothesized that addressing this lack of engagement through patient education and empowerment trainings for ART patients would help to improve patient–provider interactions.

Improving patient–provider interactions has been shown to impact retention in a treatment program and adherence to ART. Three reviews lend support for adherence interventions that include improving patient–provider interaction (Haynes et al., Citation2005; Rueda et al., Citation2006; Simoni, Amico, Pearson, & Malow, Citation2008). In the USA numerous publications provide evidence that the quality of patient–provider interactions has substantial influence on adherence and engagement in HIV care (Bakken et al., Citation2000; Beach, Keruly, & Moore, Citation2006; Flickinger, Saha, Moore, & Beach, Citation2013; Golin et al., Citation2006; Laws et al., Citation2012; Marelich, Johnston Roberts, Murphy, & Callari, Citation2002). In a 2013 study in the USA, for example, patients kept more appointments if their providers treated them with dignity and respect, listened carefully to them, explained in ways they could understand, and knew them as persons (Flickinger et al., Citation2013). Publications in resource-poor countries have similarly begun to emphasize the importance of communication and the patient–provider relationship in adherence and engagement in ART, although more studies are needed (Chen et al., Citation2013; Laws et al., Citation2012; Layer et al., Citation2014; Molassiotis, Lopez-Nahas, Chung, & Lam, Citation2003; Sanjobo, Frich, & Fretheim, Citation2008; Van Winghem et al., Citation2008; Wachira, Middlestadt, Reece, Chao-Ying, & Braitstein, Citation2014). For example, in a recent study in Kenya, better patient–provider communication was associated with an approximately 25% lower likelihood of patients’ missing an appointment (AOR: 0.75, 95% CI: 0.61–0.92) (Van Winghem et al., Citation2008). This is critical in regions such as sub-Saharan Africa that have high rates of HIV infection and struggle with the challenges of adherence to treatment (Gupta et al., Citation2011; Mills et al., Citation2006).

Despite these benefits, there is little or no routine implementation of strategies to help patients address and express their needs during consultations. Also, few intervention trials have sought to train patients to engage more fully in the health-care process; instead, most studies involve training physicians or other providers to actively communicate with patients (Dwamena et al., Citation2012; Kinnersley et al., Citation2007). Further investigations are needed to establish whether patient-focused interventions can produce overall and sustained benefits, especially for HIV/AIDS patients. The aim of our research, therefore, was to determine the effects of patient education and empowerment training on patient–doctor interactions during medical consultations in four ART clinics in Namibia.

Methods

Study design

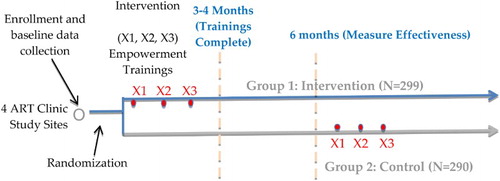

We conducted a randomized controlled parallel group trial at four hospitals in Namibia to evaluate the effectiveness of the patient education and empowerment trainings. Newly initiating adult ART patients were approached at each site. The selected hospital sites had high HIV patient loads: Katutura (Windhoek), Rundu (Kavango Region), Onandjokwe (Oshikoto Region), and Katima Mulilo (Zambezi, Region). Differences in patient–provider interaction outcomes between intervention and control groups were analyzed at 6 months. To ensure an 80% probability of detecting an effect of the patient education and empowerment training (effect size being 30% of the standard deviation of the measure), with a significance level set at p < .05 and loss to follow-up 20%, the design called for enrollment of 592 participants. Patient enrollment was conducted by the study coordinator assigned to each site from January to October 2012.

Intervention

Patients randomly assigned to Group 1 (intervention) received three, two-hour trainings in active participation, patient empowerment, and communication. The 3 trainings occurred at approximately 2 weeks, 1–2 months, and 3–4 months after enrollment. The curriculum was developed in Namibia by local content experts and was framed by the social cognitive theory of self-efficacy (Bandura, Citation1977). The content was translated into the local Namibian languages of each participating region and site. Session 1: Learning to Speak to Providers begins to teach patients how to ask questions and explain their symptoms to doctors. A game is played to teach patients about HIV, ARV side effects and adherence issues. Session 2: Using Tools to Help Communication presents different tools to patients that they can use to prepare for consultations with their doctors, for example, the “Body Map Tool” and a “Side Effects Checklist”. Session 3: Overcoming Barriers to Communication helps patients think through various remaining barriers to communication and provides them with additional tools, such as the “I tool” which teaches them to use statements with their providers that start with “I” such as “I want to know the results of my last lab test.” All trainings were held on-site, at the ART facility, in a designated clinic space that was private and large enough for groups of five to six individuals. Six months after their enrollment date, participants in the control group (Group 2) were also offered training sessions as an ethically important intervention benefit.

Data collection procedures

Data collection was integrated into each site's normal patient care routine. On the day of their ART initiation clinic visit, patients were recruited and, if they consented to participate, they were enrolled in the study. Detailed baseline participant characteristics were collected at that time. At each subsequent visit (2 weeks and 6 weeks post-ART initiation, then 3 months and 6 months post-ART initiation and thereafter every 3 months) the study coordinator placed a recording device in the room with the clinician and patient to audio-record each consultation over at least a 6-month time frame. This was done for both the intervention and control groups. The same clinicians at each site saw both groups of patients but were blinded to the extent possible as to participant group assignment. No incentive was offered to participants, though a small refund was provided to compensate for expenses involved in traveling to trainings.

Patient–provider interaction coding

The effects of the training on patient and provider engagement during medical consultations were measured using a validated method for describing medical dialogue, the Roter Interaction Analysis System (Roter & Larson, Citation2002). The audio-files collected from both groups of patients were systematically coded by four different coders using RIAS software. RIAS has been tested for validity and reliability several times in various clinical situations and has shown great coding adaptability to various types of interaction, resource-specific settings, and disease-specific interventions (Nelson, Miller, & Larson, Citation2010; Ong et al., Citation1998; Price, Windish, Magaziner, & Cooper, Citation2008). The 37 exhaustive and mutually exclusive RIAS categories capture a complete thought that is expressed by either the patient or the physician (referred to as an utterance or unit of talk). These categories group elements of exchange that reflect socioemotional communication (i.e., positive, negative, emotional, partnership building, and social exchanges) and task-focused communication (i.e., asking questions, giving instruction and direction, and giving information) (Hall, Roter, & Katz, Citation1988). In this way, the system captures four primary functions of the medical visit: data gathering, patient education and counseling, responding to patient emotions, and partnership building. In addition to the categorization of verbal communication, coders are asked to rate the global affect (emotional context) of the patient and the physician on each audiotape across several dimensions on a numeric scale of 1 (low/none) to 6 (high) (Roter & Larson, Citation2001). Coders were trained to listen to the medical dialogue in each recorded consultation and code utterances using the 37 RIAS codes. Additionally, coders were asked to rate the affect or emotional context of the dialogue using the global affect scales. Periodic reliability studies were performed, using 30–40 English language audio-files, to determine inter-coder agreement.

Statistical analysis

Data related to baseline patient demographics were compared between intervention Group 1 and the control Group 2. The coded audio-tapes in RIAS were quantified, and frequencies and overall composite scores for all categories calculated. Global affect scores for both doctor and patient were analyzed. RIAS and global affect outcomes were compared at 6 months follow-up between Groups 1 and 2 to test the post-intervention quality of patient/provider interactions (e.g., frequency of provider-initiated utterances, frequency of participant-initiated utterances, and amount of question asking or information gathering). We applied an intention-to-treat approach, considering all available observations provided by participants.

Analyses consisted of statistical testing of differences in mean outcome ratings between the two groups at the 6-month time point. Unadjusted comparisons were performed using a t-test. A mixed effects model was used for the regression, with adjustment for site, length of consultation, nurse versus doctor, provider ID, clinician's sex, patient's sex, and whether an interpreter was present. Unless specified to be for only certain outcomes, each confounder was considered for adjustment to all RIAS and global affect outcome models. If there was a confounder in at least two of these key models, we retained the potential confounder for all models.

Upon analysis of the number of observations available, we decided to use RIAS and global affect measurements from consultations audio-recorded between 4 and 8 months post enrollment.

Ethical review

This study was reviewed and approved by institutional review committees at MoHSS in Namibia, CDC in Atlanta, Georgia, and an institutional review committee at the University of Washington in Seattle, Washington.

Results

The final sample sizes consisted of 299 in the intervention group and 290 in the control group (). For both the intervention and the control groups, loss to follow-up (14% and 9% respectively) was most commonly due to patient transfers away from the study sites to new (decentralized) ART clinics (). At 6 months, a total of 160 patients (or 213 observations) were available for analysis in the intervention group and a total of 129 (or 180 observations) were available for analysis in the control group. Lack of availability of data in the 6-month window was mainly due to a missed data collection procedure (i.e., audio-taping the consultation) on the part of the study team (35.8% of missing data at 6 months in the intervention group and 41.9% of missing data at 6 months in the control group).

The baseline characteristics of the study population did not vary by randomized study group assignment, with the exception of one WHO stage (). The majority of the study participants were women (65% in the intervention group and 69% in the control group). About half of the participants reported to be single (52% in the intervention group and 53% in the control group) and the length of time since testing positive for HIV was approximately a year and a half (17.1 months in the intervention group and 19.7 months in the control group, on average) ().

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the study population by study group.

At 6 months follow-up, RIAS and global affect outcomes were analyzed for all sites combined, and for both study groups. For RIAS outcomes, a total of 393 consultations were analyzed from a total of 289 participants (). For global affect outcomes, a total of 381 consultations were analyzed from a total of 286 participants. The overall average length of consultations was 5.58 minutes, 5.78 minutes in the trained group and 5.37 minutes in the untrained group.

Table 2. Six month RIAS and global affect measures by study group.

Inter-coder reliability was tested 2 times during the study, and resulted in inter-coder per cent agreement ranging from 75% to 85%. The majority of patient–provider interaction outcomes were higher in the intervention group, but were not statistically significantly different than the control group. For those RIAS outcomes measured, 4 of 8 outcomes were statistically significant at the 6-month time point, indicating a statistically significantly higher mean in the intervention group (). The RIAS outcomes for clinicians that were significant were facilitation and patient activation (adjusted difference 1.19, 95% CI = .39, 1.99, p = .004) and clinician information gathering (adjusted difference 2.96, 95% CI = 1.42, 4.50, p = .000). The RIAS outcomes for the patient that were significant were all patient question asking (adjusted difference .48, 95% CI = .11, .85, p = .012) and patient positive affect (adjusted difference 2.08, 95% CI = .79, 3.36, p = .002).

One additional patient–provider global affect outcome was found to be significantly higher in the intervention group. This outcome was clinician positive affect (adjusted difference .60, 95% CI = .08, 1.11, p = .02).

Discussion

This study showed positive impact of patient education and empowerment through targeted training on the quality of patient–provider interactions for newly initiating ART patients in Namibia. This is supported by the statistically significant findings in 5 of the 13 RIAS and global affect outcomes measured at 6 months post enrollment when comparing trained patients to untrained patients. It is also supported by the positive trend of the majority of the 13 patient–clinician interaction outcome means toward the intervention group. Patients who were trained were more likely to ask questions during consultations and generally enjoyed the interaction with the clinicians more than controls, as evidenced by the impact of the training on patient overall question asking and patient positive affect during consultations.

Evidence from the USA suggests that patients who actively participate in consultations influence their care-givers to adopt a more patient-centered style of communication (Cegala & Post, Citation2009). Similarly, we found the training intervention in this study also impacted the health-care providers: clinicians in the study gathered more information from trained patients, facilitated and activated patients and showed more positive emotional affect during consultations. “Facilitation and activation of patients” included interactions where a clinician asks for a patient's opinion, asks for permission (e.g., for a physical examination), asks for reassurance, or paraphrases and checks for patient understanding. It is possible that increases in this kind of interaction with patients resulted from empowered patients encouraging more dialogue with the clinician, thus motivating the clinician to gather more information from, and interact in a more meaningful way, with the patient, respect the patient more and in the end increasing the satisfaction with the interaction for both the provider and the patient. If so, this evidence of high-quality two-way dialogue is a sign that communication during the consultation probably resulted in a high level of mutual understanding and greater trust between the patient and provider (Flickinger et al., Citation2013).

Overall, clinicians did not dominate the conversations with trained or untrained patients, although it was hypothesized that trained patients would dominate the conversation by speaking more than the clinicians. This may indicate that the positive findings in the study are due more to the quality of the interaction between clinician and patient and less to the amount spoken by each during the consultation. Also, there was no significant difference in patient centeredness between groups, although it was expected that empowered patients would feel more open to engage in lifestyle/psychosocial issues. This may indicate that the training did not influence whether dialogue was largely biomedical or lifestyle/psychosocial in nature, as patient centeredness is a composite RIAS variable that contrasts these two patient concerns. However, the analyses show that biomedical codes were very common and lifestyle/psychosocial codes much more rare, making it difficult to measure any difference in lifestyle/psychosocial dialogue. The consultations may also have been too short to allow dialogue to reach lifestyle/psychosocial issues. Still, trained patients were clearly comfortable asking direct questions, especially questions about their medical condition and/or therapeutic regimen, with twice as much question asking in the intervention group as the control group.

It is unclear why so few global affect categories were statistically significant, while many of the RIAS categories were. Since RIAS codes are based directly on utterances, they may be less prone to subjectivity and lack of precision as compared to the more subjective global affect ratings, which rate overall mood and emotion. Indeed, global affect ratings in other RIAS studies have not always equaled the reliability level of the RIAS codes (Ong et al., Citation1998). In addition, the cultural barriers present during the trainings likely did not allow a full exploration of these more complex concepts, when trainers concentrated more on how to train patients to ask more questions and be more involved in their therapeutic course.

Overall, the quality of patient–clinician interactions was higher in the intervention group and for the clinicians who saw them – an important finding given the strong association the patient–provider relationship has with ART adherence, which is ultimately tied to the prevention of growing antiretroviral resistance. Increased provider satisfaction is of great value in high-volume ART settings such as these where high patient load can lead to burn-out among providers. Increased ART patient satisfaction is strongly correlated with better engagement with care (e.g., attending clinic visits), adherence to ARV and other health outcomes (Geng et al., Citation2010). In conclusion, the findings of this study suggest that patients can be trained to improve their interactions with their providers, a quality that has been shown empirically to have a direct impact on ART adherence. Future studies should examine the impact of similar patient education and empowerment interventions on ART adherence.

Acknowledgements

Sincere thanks to the Namibian Government and to the clinical staff and patients at the four ART clinics in the study for so strongly supporting this work. Also we are indebted to the U.S. President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through HRSA (Health Resources and Services Administration) and administered by CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) in Namibia, for supporting this work. GO, EM, LB and CK contributed to the design of the study, protocol development and development of forms. CK, GO, PI, JU, RM, JL, RS, MSP, NH and EM helped to implement the study at the 4 sites in Namibia, including coding of medical dialogue. EM and KT performed the analyses. GO, EM, MSP, KT and LB drafted the manuscript and made substantive intellectual contribution to the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bakken, S., Holzemer, W., Brown, M., Powell-Cope, G., Turner, J., Inouye, J., … Corless, I. B. (2000). Relationships between perception of engagement with health care provider and demographic characteristics, health status, and adherence to therapeutic regimen in persons with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 14, 129–197. doi:10.1089/108729100317795

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84, 191–215. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/847061 doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

- Beach, M., Keruly, J., & Moore, R. D. (2006). Is the quality of the patient-provider relationship associated with better adherence and health outcomes for patients with HIV? Journal of General Internal Medicine, 21, 661–665. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00399.x

- Cegala, D. J., & Post, D. M. (2009). The impact of patients’ participation on physicians’ patient-centered communication. Patient Education and Counseling, 77, 202–208. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2009.03.025

- Chen, W. T., Wantland, D., Reid, P., Corless, I. B., Eller, L. S., Iipinge, S., … Webel, A. R. (2013). Engagement with health care providers affects self-efficacy, self-esteem, medication adherence and quality of life in people living with HIV. Journal of AIDS and Clinical Research, 4, 256–269. doi:10.4172/2155-6113.1000256

- Dwamena, F., Holmes-Rovner, M., Gaulden, C. M., Jorgenson, S., Sadigh, G., Sikorskii, A., … Olomu, A. (2012 , December 12). Interventions for providers to promote a patient-centered approach in clinical consultations. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews , Article # CD003267. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003267.pub2

- Flickinger, T. E., Saha, S., Moore, R., & Beach, M. C. (2013). Higher quality communication and relationships are associated with improved patient engagement in HIV care. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, 63, 362–366. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e318295b86a

- Geng, E., Nash, D., Kambuga, A., Zhang, Y., Braitstein, P., Christopoulos, K.A., … Martin, J. N. (2010). Retention in care among HIV-infected patients in resource-limited settings: Emerging insights and new directions. Current HIV/AIDS Reports, 7, 234–44. doi:10.1007/s11904-010-0061-5

- Golin, C. E., Earp, J., Tien, H. C., Stewart, P., Porter, C., & Howie, L. (2006). A 2-arm, randomized, controlled trial of a motivational interviewing-based intervention to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) among patients failing or initiating ART. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, 42, 42–51. doi:10.1097/01.qai.0000219771.97303.0a

- Gupta, A., Nadkarni, G., Yang, W. T., Chandrasekhar, A., Gupte, N., Bisson, G. P., … Gummadi, N. (2011). Early mortality in adults initiating antiretroviral therapy (ART) in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC): Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One, 6(12), e28691. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0028691

- Hall, J. A., Roter, D. L., & Katz, N. R. (1988). Meta-analysis of correlates of provider behavior in medical encounters. Medical Care, 26, 657–675. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3292851 doi: 10.1097/00005650-198807000-00002

- Haynes, R. B., Yao, X., Degani, A., Kripalani, S., Garg, A., & McDonald, H. P. (2005). Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews , Issue 4. Art. No.: CD000011. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000011.pub2

- Kinnersley, P., Edwards, A., Hood, K., Cadbury, N., Ryan, R., Prout, H., … Butler, C. (2007, July 18). Interventions before consultations for helping patients address their information needs. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Article # CD004565.

- Laws, M. B., Rose, G. S., Bezreh, T., Beach, M. C., Taubin, T., Kogelman, L., & Wilson, I. B. (2012). Treatment acceptance and adherence in HIV disease: Patient identity and the perceived impact of physician-patient communication. Journal of Patient Preference and Adherence, 6, 893–903. doi:10.2147/PPA.S36912

- Layer, E. H., Brahmbhatt, H., Beckham, S. W., Ntogwisangu, J., Mwampashi, A., Davis, W. W., … Kennedy, C. E. (2014). “I pray that they accept me without scolding:” Experiences with disengagement and re-engagement in HIV care and treatment services in Tanzania. AIDS Patient Care and STDS, 28, 483–488. doi:10.1089/apc.2014.0077

- Marelich, W., Johnston Roberts, K., Murphy, D. A., & Callari, T. (2002). HIV/AIDS patient involvement in antiretroviral treatment decisions. AIDS Care, 14, 17–26. doi:10.1080/09540120220097900

- Mills, E. J., Nachega, J. B., Buchan, I., Orbinski, J., Attaran, A., Singh, S., … Bangsberg, D. (2006). Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa and North America. JAMA, 296(6), 679–690. doi:10.1001/jama.296.6.679

- Ministry of Health and Social Services, Directorate of Special Programmes, Windhoek, Namibia. (2013). Global AIDS response progress reporting, Reporting Period 2012/2013. Retrieved from http://www.unaids.org/en/dataanalysis/knowyourresponse/countryprogressreports/2014countries/NAM_narrative_report_2014.pdf

- Molassiotis, A., Lopez-Nahas, V., Chung, W. Y., & Lam, S. W. (2003). A pilot study of the effects of a behavioural intervention on treatment adherence in HIV-infected patients. AIDS Care, 15, 125–135. doi:10.1080/0954012021000039833

- Nelson, E., Miller, E. A., & Larson, K. A. (2010). Reliability associated with the Roter Interaction Analysis System (RIAS) adapted for the telemedicine context. Patient Education and Counseling, 78(1), 72–78. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2009.04.003

- Ong, L. M., Visser, M. R., Kruyver, I. P., Bensing, J. M., van den Brink-Muinen, A., Stouthard, J. M., … de Haes, J. C. (1998). The Roter Interaction Analysis System (RIAS) in oncological consultations: Psychometric properties. Psychooncology, 7(5), 387–401. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9809330 doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(1998090)7:5<387::AID-PON316>3.0.CO;2-G

- Price, E. G., Windish, D. M., Magaziner, J., & Cooper, L. A. (2008). Assessing validity of standardized patient ratings of medical students’ communication behavior using the Roter interaction analysis system. Patient Education and Counseling, 70(1), 3–9. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2007.10.002

- Roter, D. L., & Larson, S. (2001). The relationship between residents’ and attending physicians’ communication during primary care visits: An illustrative use of the Roter interaction analysis system. Health Communication, 13, 33–48. doi: 10.1207/S15327027HC1301_04

- Roter, D. L., & Larson, S. (2002). The Roter interaction analysis system (RIAS): Utility and flexibility for analysis of medical interactions. Patient Education and Counseling, 46, 243–251. doi:10.1016/S0738-3991(02)00012-5

- Rueda, S., Park-Wyllie, L. Y., Bayoumi, A., Tynan, A. M., Antoniou, T., Rourke, S., & Glazier, R. (2006). Patient support and education for promoting adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy for HIV/AIDS. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews , Issue 3. Art. No.: CD001442. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001442.pub2

- Sanjobo, N., Frich, J. C., & Fretheim, A. (2008). Barriers and facilitators to patients’ adherence to antiretroviral treatment in Zambia: A qualitative study. Journal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS Research Alliance, 5, 136–43. doi:10.1080/17290376.2008.9724912

- Simoni, J. M., Amico, K. R., Pearson, C. R., & Malow, R. (2008). Strategies for promoting adherence to antiretroviral therapy: A review of the literature. Current Infectious Disease Reports, 10, 515–521. doi:10.1007/s11908-008-0083-y

- Van Winghem, J., Telfer, B., Reid, T., Ouko, J., Mutunga, A., Jama, Z., & Shobha, V. (2008). Implementation of a comprehensive program including psycho-social and treatment literacy activities to improve adherence to HIV care and treatment for a pediatric population in Kenya. BMC Pediatrics, 8, 52. doi:10.1186/1471-2431-8-52

- Wachira, J., Middlestadt, S., Reece, M., Chao-Ying, J. P., & Braitstein, P. (2014). Physician communication behaviors from the perspective of adult HIV patients in Kenya. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 26, 190–197. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzu004

- World Health Organization. (2013). Global update on HIV treatment 2013: Results, impact and opportunities. Retrieved from http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/20130630_treatment_report_en_0.pdf