ABSTRACT

We compared virological and immunological outcomes for young adults with perinatally-acquired HIV infection (YAPaHIV) in the year preceding, and year of, UK SARS-CoV-2 lockdown restrictions, in a service that maintained face-to-face appointments. Retrospective single-centre cohort analysis from; Period 1(P1) twelve months before the first national lockdown – 23rd March 2019–23rd March 2020, period 2(P2) twelve months of varied restrictions – 24th March 2020–24th March 2021. Data collected from electronic records included age, ethnicity, sex, HIV viral load (VL) (suppression ≤ 200 copies/ml), CD4 count (cells/μL), clinical events, and appointment frequency/modality. Descriptive analysis was comparative between periods. Of 177 YAPaHIV: 56% were female, 86.9% were black, median age at lockdown 23 years (IQR: 21–27). One individual was lost to follow up and excluded from subsequent analysis. 147/176 (83.5%) had a suppressed VL in P1 compared with 156/176 (88.6%) in P2. Of those detectable, median VL was 3200 copies/ml (IQR: 925–36500) in P1, and 911copies/ml (IQR: 317–52300) in P2. In P1, median CD4 was 675 (IQR: 447–845.25). 32(18%) had a CD4 < 350 (median 216.5 [IQR: 94.25–269.75]). 110 (59.5%) had a CD4 count in P2, median 551.5cells/μL (IQR: 329.25–761.25). Thirty one had CD4 < 350 (median 202 [IQR: 134.5–296]). Maintaining face-to-face appointments for vulnerable patients, with remote consultation for stable patients, maintained high levels of care engagement and suppression in a YAPaHIV cohort despite pandemic restrictions.

Introduction

Adolescents (A, 10–19 years) and young adults (YA, 20–24 years) living with perinatally acquired HIV-1 infection (AYAPaHIV) have poorer outcomes at all stages of the care cascade when compared to older adults (Zanoni & Mayer, Citation2014). Adolescence is a complex period of maturation, and encompasses the transition from family based paediatric care, to autonomous independent healthcare, and is a vulnerable time with loss of healthcare engagement, and increased HIV associated morbidity (Foster & Fidler, Citation2018; Zanoni & Mayer, Citation2014). Late adolescence (15–19 years) is the only age group globally with increasing HIV associated mortality (Slogrove et al., Citation2017). UK guidelines from the British HIV Association (BHIVA) recommend 6–12 monthly monitoring of stable adults (18+ years) with a suppressed HIV viral load (VL) on antiretroviral therapy (ART), with CD4 monitoring every 3–6 months until 2 reconstituted chronological counts >350 (Brian Angus et al., Citation2019). How this relates to optimal monitoring for AYAPaHIV remains uncertain, as their “stable” status often varies with life changes.

During the COVID pandemic, the UK government imposed a nationwide stay at home order, limiting reasons for public travel from 23rd March 2020 (UK Government, Citation2020). The NHS issued guidance for a reduction of in-person consultations, particularly in stable patients (NHS England, Citation2020). BHIVA advised that stable individuals with a suppressed VL follow government guidance, and those with a CD4 < 50 cells/μL shield as extremely clinically vulnerable (BHIVA; THT, Citation2020). Easing of the first UK national lockdown restrictions was announced on 10th May 2020, with the reintroduction of essential in-person medical care from July 2020 (Prime Minister’s Office 10 Downing Street; The Rt Hon Boris Johnson MP, Citation2020a). A second national “circuit-breaker” lockdown was introduced in November 2020, with varied “tier” based restrictions through to March 2021 (Prime Minister’s Office 10 Downing Street; The Rt Hon Boris Johnson MP, Citation2020b).

The “900 Clinic” is a specialist multidisciplinary service for AYAPaHIV, described in detail previously, and cares for a vulnerable youth population, many with complex medical, psychosocial, and mental health needs (Foster et al., Citation2020; Mallik et al., Citation2021). Despite viral suppression in 80%, mortality, and rates of malignancy and psychosis are 10 times the aged matched UK population rates (Foster et al., Citation2020; Mallik et al., Citation2020). Healthcare professionals advocated for the continued option for face to face (F2F) consultations throughout lockdown.

We sought to characterise changes in virological suppression and access to care in the year prior to, and during a year of national pandemic restrictions, in a clinic that maintained walk-in F2F care for AYAPaHIV.

Methods

A retrospective single-centre cohort analysis of AYAPaHIV attending a specialist young person’s HIV outpatient service: the “900 Clinic”.

900 Clinic setting

The multidisciplinary service offers weekly booked, and walk-in appointments, the latter to reduce structural barriers to care. Face-to-face appointments provide medical, mental and sexual health assessment, phlebotomy, sexual health screening, vaccination, and long acting ART/contraception. Telephone/Attend Anywhere consultations were available for stable patients, those unable to travel, clinical psychology, and peer support through the third sector agency “Positively UK”. Medical staff redeployed to COVID services returned to run the weekly clinic.

Patients were screened; symptom and temperature check, required to wear masks, and use hand sanitiser at clinic entry. Individuals symptomatic of potential SARS-CoV-2 infection were diverted to COVID accident and emergency for assessment. The waiting room was socially distanced with removal of communal magazines, gaming consoles and snacks typically provided in this “Youth Friendly” service. Free condom access was limited to sealed packs from clinicians rather than freely available in the bathrooms.

Data collection

Data was collected from NHS electronic clinical records for 2 time periods; pre-lockdown, period 1 (P1): 23rd March 2019–23rd March 2020, and during pandemic restrictions, period 2 (P2): 24th March 2020–24th March 2021. Data collected for each time periods included: age, ethnicity, sex, plasma HIV VL (RNAcopies/ml), CD4 counts (cells/μL), genotypic resistance, ART, engagement with care: appointment dates and types, and clinical events. Eligible patients were all those enrolled in care prior to March 2019.

Data analysis

Analysis was descriptive of demographics, VL, and CD4 count for each time period.

The primary outcome was the proportion of individuals with a suppressed HIV plasma VL < 200 copies/ml. Secondary outcomes describe uptake of care and clinical events including hospitalisations, pregnancy, and evidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Routine SARS-CoV-2 testing was not available, with the exception of hospital admission, however, those symptomatic were able to access government-based community PCR testing.

Results

Of 177 AYAPaHIV, 1 (0.6%) had no VL data in period 2 and was excluded from further analysis (phone contact only in P2). Of the 176 retained in care: 56% were female based on assigned sex at birth, 86.9% were black, 6.8% white, 4.5% mixed-heritage, and 1.8% other. Median age at lockdown was 23 years (IQR: 21–27, range 17–35). All individuals were prescribed ART.

Virology

Primary endpoint: 147/176 (83.5%) participants achieved viral suppression (VS) prior to lockdown, with 156 (88.6%) suppressed during lockdown. Of those with detectable viraemia, the median VL was 3200 copies/ml (IQR: 925–36500) in period 1 (n = 29) and 911 copies/ml (IQR: 317–52300) in period 2 (n = 20) (). 17/29 (58.6%) with a detectable VL in P1 (median VL 2050 [IQR: 800–13800]) achieved VS in lockdown. 8/146 (5.5%) suppressed in P1 experienced virological failure in P2; median VL 534 copies/ml (IQR: 248–14033), with no new resistance mutations on genotyping. One hundred thirty nine individuals (80.0%) maintained VS throughout both time periods.

Table 1. Virological, immunological, and clinical outcomes by study period.

Immunology

Prior to lockdown, the median CD4 was 675 (IQR: 447–845.25). 32 (18.2%) had a CD4 < 350 (median 216.5 [IQR: 94.25–269.75]), of whom 5 were shielding (CD4 < 50 cells/μL). 110 (59.5%) had a CD4 count repeated in P2, median 551.5 (IQR: 329.25–761.25) cells/μL. Thirty one with CD4 < 350 (median 202 [IQR: 134.5–296]); 4 shielding. Four of 15 AYAPaHIV with CD4 count < 200 cells/μL in P1 (median 80 [IQR: 38–128]) reconstituted to >200 cells/μL in P2. Three with CD4 > 200 in P1 fell below 200 cells/μL by end of P2 ().

Access to services

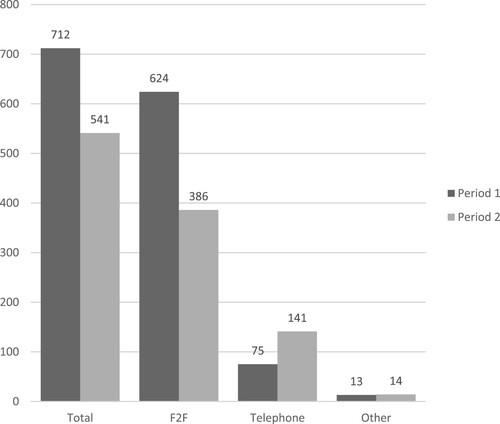

Of 712 appointments in period 1, 624 (87.6%) were F2F with a median of 3 (IQR: 2–4.25) appointments per patient (). Of 541 appointments in period 2, 386 (71.3%) were F2F, appointments per patient 3 (IQR: 2–4). F2F appointments fell from a mean of 3.55 per patient in P1 to 2.19 in P2. The median duration between the last appointment in P1, and the first in P2 was 168 days (IQR: 100–231).

53/176 (30.1%) accessed clinical psychology F2F in P1, compared with 68 (38.6%) remotely in P2. The average number of consultations per week was 5.2 in P1, and 10.9 in P2, most frequently for low mood, with an increase in concurrent anxiety/adjustment issues in P2. There were 4 psychotic episodes; 3 in P1 and 1 in P2 ().

SARS-CoV-2 testing

3 of 25 tested had SARS-CoV-2 infection: 1 by polymerase chain reaction (symptomatic presentation to the “NHS Test & Trace” scheme) and two with past infection by serology, prior to vaccination. There was no evidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection within 14 days of clinic attendance.

Clinical events

No deaths occurred. 9 individuals experienced 12 admissions, 9 in period 1 and 3 in period 2; four with new AIDS defining illnesses (). 16 pregnancies, four ongoing, were recorded for 12 women, with completed outcomes detailed in .

Discussion

The shift to remote medical management during lockdown represented a challenging time for healthcare services. The 900 Clinic remained open for F2F appointments throughout, to minimise barriers to effective HIV care for those individuals most at risk, whilst providing remote consultations and postage of medication for stable patients, and those unable to travel. Maintaining a flexible open access service with symptom screening, social distancing, and face masks was safe and effective, with no deaths, a loss to follow up rate of <1%, and maintained rates of viral suppression; 83.5% in the year prior to, and 88.6% in year of, the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. There was no evidence of SARS-CoV-2 transmission resulting from F2F clinic attendance.

The median number of appointments was maintained at 3 per year, with an increase in telemedicine consultations from 1 in 10 to 1 in 4. Whilst remote consultations remove some structural barriers to care, including financing transportation and clinic waiting times, new barriers are raised such as access to devices, data and subscriptions, and a safe, confidential space in which to talk (Almathami et al., Citation2020). This is particularly pertinent for those living in shared student accommodation, and vulnerable groups including the homeless, the incarcerated, and those living with cognitive, auditory, and visual impairment (Almathami et al., Citation2020). Even for those living within a family home, frequently other relations remain unaware of HIV within the family (Deakin et al., Citation2020). Whilst there were pre-pandemic guidelines for telemedicine in general paediatrics, there were no guidelines specific for adolescent health. Preliminary studies outside the setting of HIV, have cited barriers for youth access to telemedicine relating to race, lower socioeconomic status, devices, and overcrowded accommodation (Barney et al., Citation2020; Wood et al., Citation2020). For those living with HIV, early data from the United States has shown increased virological failure amongst those under 35 years, of black ethnicity, and vulnerable homeless populations when shifting to a telemedicine-based model of care during the pandemic (Spinelli et al., Citation2020). Conversely, this service, for predominantly young adults of black ethnicity, did not adopt a full telemedicine approach, and a hybrid model with open access to F2F multidisciplinary care throughout the year of the pandemic maintained viral suppression with no apparent rise in clinical events. In a survey of UK clinicians, 87% indicated that HIV prevention and treatment had been impacted by the pandemic; highlighting the loss of holistic care particularly for the most vulnerable (BHIVA; BASHH, Citation2020). Their concerns are corroborated by data from Lombardy, an early epicentre of COVID-19, indicating a significant decline in new HIV diagnoses and ART prescription collection, following a pandemic shift to telemedicine (Quiros-Roldan et al., Citation2020). More widely, and of grave concern, there may be an estimated excess of 296,000 HIV associated deaths in Sub-Saharan Africa alone, due to pandemic associated interruptions in HIV prevention and treatment services (The Lancet, Citation2020).

The findings of our study should be interpreted in the context of study limitations that include the retrospective analysis of a small cohort attending a designated youth friendly service, with a small number of clinical events, and the fluctuating nature of governmental COVID-19 restrictions. However, pre-pandemic data suggests that integrated youth-friendly services and adolescent-specific differentiated models of care may improve aspects of the HIV care continuum (Reif et al., Citation2018). Maintaining differentiated models of care for vulnerable populations in the face of generic national guidance and staff redeployment is challenging, but the needs of youth should not be lost when allocating limited healthcare provisions during a pandemic where hospitalisation and death were mainly limited to the elderly (Archard & Caplan, Citation2020). Moving to a hybrid model of care where telemedicine is combined with less frequent but comprehensive F2F appointments that address the multidisciplinary needs of AYAPLHIV requires further exploration, but open access F2F services must remain an option for vulnerable (Evans et al., Citation2020).

In conclusion for this small, well-described cohort, we demonstrated that a proactive response maintaining F2F clinics and regular attendance for vulnerable populations can maintain safe linkage to care and virological control during pandemic restrictions.

Acknowledgements

The preliminary findings were presented as a poster at BHIVA/BASHH Virtual 2021.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Almathami, H. K. Y., Win, K. T., & Vlahu-Gjorgievska, E. (2020). Barriers and facilitators that influence telemedicine-based, real-time, online consultation at patients’ homes: Systematic literature review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(2), e16407. https://doi.org/10.2196/16407

- Angus, B., Brook, G., Awosusi, F., Barker, G., Boffito, M., Das, S., Dorrell, L., Dixon-Williams, E., Hall, C., Howe, B., Kalwij, S., Matin, N., Nastouli, E., Post, F., Tenant-Flowers, M., Smit, E., & Wheals, D. (2019). BHIVA guidelines for the routine investigation and monitoring of adult HIV-1-positive individuals (2019 interim update). BHIVA. https://www.bhiva.org/file/DqZbRxfzlYtLg/Monitoring-Guidelines.pdf

- Archard, D., & Caplan, A. (2020). Is it wrong to prioritise younger patients with covid-19? BMJ, 369(8242), m1509. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m1509.

- Barney, A., Buckelew, S., Mesheriakova, V., & Raymond-Flesch, M. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic and rapid implementation of adolescent and young adult telemedicine: Challenges and opportunities for innovation. Journal of Adolescent Health, 67(2), 164–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.05.006

- BHIVA; BASHH. (2020). APPG inquiry HIV and COVID-19 joint response from the British HIV Association (BHIVA) and British Association for Sexual Health and HIV (BASHH). https://www.bhiva.org/file/5eecd3dba01c6/APPG-BHIVABASHH-submission-190620.pdf

- BHIVA; THT. (2020). British HIV Association (BHIVA) and Terrence Higgins Trust (THT) statement on COVID-19 and advice for the extremely vulnerable. https://www.bhiva.org/BHIVA-and-THT-statement-on-COVID-19-and-advice-for-the-extremely-vulnerable

- Deakin, H., Frize, G., Foster, C., & Evangeli, M. (2020). We’re touching the topic, but we’re not opening the book: A grounded theory study of sibling relationships in young people with perinatally acquired HIV. Journal of Health Psychology, 27(3), 612–623. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105320962271.

- Evans, Y. N., Golub, S., Sequeira, G. M., Eisenstein, E., & North, S. (2020). Using telemedicine to reach adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Adolescent Health, 67(4), 469–471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.07.015

- Foster, C., Ayers, S., Mcdonald, S., Frize, G., Chhabra, S., Pasvol, T. J., & Fidler, S. (2020). Clinical outcomes post transition to adult services in young adults with perinatally acquired HIV infection: Mortality, retention in care and viral suppression. AIDS, 34(2), 261–266. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000002410

- Foster, C., & Fidler, S. (2018). Optimizing HIV transition services for young adults. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases, 31(1), 33–38. https://doi.org/10.1097/QCO.0000000000000424

- Mallik, I., Pasvol, T., Frize, G., Ayres, S., Barrera, A., Fidler, S., & Foster, C. (2020). Psychotic disorders in young adults with perinatally acquired HIV: A UK case series. Psychological Medicine. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720004134.

- Mallik, I., Umaipalan, A., Badhwar, V., Rashid, T., & Dhairyawan, R. (2021). A descriptive study of British South Asians living with HIV in North East London. AIDS Care, 33(4), 537–540. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2020.1754326

- NHS England. (2020). Clinical guide for the management of remote consultations and remote working in secondary care during the coronavirus pandemic. NHS England. https://www.england.nhs.uk/coronavirus/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2020/03/C0044-Specialty-Guide-Virtual-Working-and-Coronavirus-27-March-20.pdf

- Prime Minister’s Office 10 Downing Street; The Rt Hon Boris Johnson MP. (2020a). Prime Minister’s statement on coronavirus (COVID-19): 10 May 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/pm-address-to-the-nation-on-coronavirus-10-may-2020

- Prime Minister’s Office 10 Downing Street; The Rt Hon Boris Johnson MP. (2020b). Prime Minister announces new national restrictions. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/prime-minister-announces-new-national-restrictions

- Quiros-Roldan, E., Magro, P., Carriero, C., Chiesa, A., El Hamad, I., Tratta, E., Fazio, R., Formenti, B., & Castelli, F. (2020). Consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on the continuum of care in a cohort of people living with HIV followed in a single center of Northern Italy. AIDS Research and Therapy, 17(1), 59. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12981-020-00314-y

- Reif, L. K., McNairy, M. L., Lamb, M. R., Fayorsey, R., & Elul, B. (2018). Youth-friendly services and differentiated models of care are needed to improve outcomes for young people living with HIV. Current Opinion in HIV and AIDS, 13(3), 249–256. https://doi.org/10.1097/COH.0000000000000454

- Slogrove, A. L., Mahy, M., Armstrong, A., & Davies, M.-A. (2017). Living and dying to be counted: What we know about the epidemiology of the global adolescent HIV epidemic. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 20(S3), 21520. https://doi.org/10.7448/IAS.20.4.21520.

- Spinelli, M. A., Hickey, M. D., Glidden, D. V., Nguyen, J. Q., Oskarsson, J. J., Havlir, D., & Gandhi, M. (2020). Viral suppression rates in a safety-net HIV clinic in San Francisco destabilized during COVID-19. AIDS, 34(15), 2328–2331. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000002677

- The Lancet. (2020). Maintaining the HIV response in a world shaped by COVID-19. The Lancet, 396(10264), 1703. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32526-5

- UK Government. (2020). Staying at home and away from others (social distancing). https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/full-guidance-on-staying-at-home-and-away-from-others

- Wood, S. M., White, K., Peebles, R., Pickel, J., Alausa, M., Mehringer, J., & Dowshen, N. (2020). Outcomes of a rapid adolescent telehealth scale-up during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Adolescent Health, 67(2), 172–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.05.025

- Zanoni, B. C., & Mayer, K. H. (2014). The adolescent and young adult HIV cascade of care in the United States: Exaggerated health disparities. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 28(3), 128–135. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2013.0345