ABSTRACT

New strategies are needed to improve HIV testing rates in Tanzania, particularly among adult men. We sought to investigate if HIV oral self-testing would increase HIV testing uptake in Tanzanian rural community homes. The study design was a prospective community-randomized pilot study, in two matched villages with similar characteristics (intervention and control villages) Before data collection, we trained village health workers and research assistants for one week. We recruited male and female adults from 50 representative households in each of two villages in eastern Tanzania. We collected data at baseline and we followed-up the enrolled households after a one-month period. There was a high interest in testing for HIV, with all participants from both arms (100%; n = 259) reporting that they would like to test for HIV. After the one-month follow-up, overall, 66.1% (162/245) of study participants reported to have tested for HIV in both arms. In the intervention arm, 97.6% (124/127) reported that they tested for HIV versus in the control arm, 32.2% (38/118) tested for HIV, p-value < 0.001. In Tanzania, we found that availability of HIV self-testing was associated with an enormous increase in HIV testing uptake in a rural population.

Introduction

The HIV/AIDS epidemic has had a devastating impact on sub-Saharan Africa over the last few decades. While huge steps have been made towards developing effective treatments to prevent AIDS among those infected with HIV, we must still increase the proportion of the population testing, and link those that test positive to care and treatment services in order to achieve viral suppression. The current treatment target encouraged by UNAIDS is to achieve 95% of infected individuals knowing their status, 95% of those diagnosed on sustained ARV therapy, and 95% of those receiving antiretroviral (ARV)therapy achieving viral suppression(Ehrenkranz et al., Citation2021). Only 52.2 percent of persons living with HIV/AIDS (PLHIV) aged 15–64 years in Tanzania (55.9% of HIV-positive females and 45.3% of HIV-positive males) are aware of their HIV status (NBS, Citation2017).

In one systematic review, self-testing was identified as one approach that could improve testing and counseling uptake for individuals who prefer to test with a degree of privacy (Pai & Dheda, Citation2013). HIV oral self-testing has been approved in several countries and may provide an important opportunity to increase the proportion of individuals testing; first because the oral test does not require a finger prick, making it easier to self-administer, and second because the distribution of self-testing kits appears to break down numerous barriers to testing including desire for privacy, fear of stigma around HIV, time required to be tested at a clinic, and control over the process (Choko et al., Citation2011). However, the concern is that the individual who uses an HIV self-testing kit and tests positive must follow the necessary steps, including counseling, post-test counseling, and linkage to care.

While HIV testing rates have increased recently in urban areas of Tanzania such as Dar es Salaam and the surrounding towns (Theuring et al., Citation2016), testing rates remain low in more rural areas (Cawley et al., Citation2013, Citation2015; Killewo et al., Citation1990; Sing & Patra, Citation2015). Women who spend their evenings outside and women who have multiple sexual partners could be some of the risk factors that might linked to increased HIV incidence in urban settings than in rural ones (Sing & Patra, Citation2015). Most testing is conducted by young women in prenatal care (Theuring et al., Citation2016), whereas testing rates among men appears to be quite low (Isingo et al., Citation2012; Wringe et al., Citation2012). It was found that fear of a positive test result and a low sense of HIV risk were the hurdles to men getting HIV testing services. Tanzania has created national plans to address these obstacles to HIV testing services and direct the country’s Test and Treat program, which aims to increase the uptake of HIV testing services among men (Conserve et al., Citation2019).

A major gap, therefore, exists between current testing rates in smaller rural villages and the UNAIDS-set goal of 95% testing. In rural Tanzania, a study indicated that 54% of men and 78% of women reported having tested for HIV (Kaufman et al., Citation2015). However, according to a research, the rate of HIV testing in rural Ugandans was 91% (Kalichman et al., Citation2020). One recently developed tool that may help us reach more individuals for HIV testing is the oral self-testing (OST) kit. Oral testing has been developed by at least two companies (OraSure Technologies, Bethlehem, PA [OraQuick] and WinHealth Medical (Suzhou) Technology Co. Ltd [Oral antigen Rapid Test]). The OST has been approved and found to be acceptable and feasible in numerous countries worldwide, including the US (Mathews et al., Citation2020), Kenya (Gichangi et al., Citation2018) (Kurth et al., Citation2016), Uganda (Korte et al., Citation2020), and recently Tanzania (Conserve et al., Citation2018). However, little research has focused specifically on the acceptability and feasibility of HIV OST in rural communities.

The goal of this study was to investigate if HIV oral self-testing will increase HIV testing uptake in Tanzanian rural community homes. We particularly aimed to target households with a male head of household, in light of lower HIV testing rates among men in Tanzania.

Methods

Study design

The study design was a prospective community-randomized trial in two matched villages with similar characteristics that were 8.4 kilometers apart from each other. We conducted an HIV testing initiative in both villages, and the study arms were (1) standard of care in which participants were encouraged to visit the clinic to be tested for HIV, and (2) intervention arm in which participants were also offered HIV oral self-testing kits as a testing option. These two villages purposely selected were roughly matched on size, distance from a main road, distance from an urban center, demographic characteristics, socioeconomic conditions, and access to HIV clinical services. In Tanzania’s Bagamoyo district, Pwani region, Zinga village was chosen as an intervention arm and Kiromo village as a control arm. In the Pwani region, the prevalence of HIV was 5.3% in people between the ages of 15 and 49 in 2017 (TACAIDS, Citation2018). Furthermore, according on antenatal care clinic surveillance for Tanzania’s mainland in 2020, the HIV prevalence in the Bagamoyo district hospital was 4% (NACP, Citation2021). To evaluate study outcomes, interviews with each study participant from each arm were conducted at the beginning of the study and again a month later. We offered the HIV OST kit for measuring HIV infection in the intervention village, whereas in the control village we promoted the clinic-based Tanzanian standard of care for HIV Testing and Counselling (HTC).

Sample size

We planned to enroll adults from 50 households in each village. We estimated an average of three adults per household, leading to an expected 150 participants in the intervention arm and 150 participants in the control arm. The sample size of this pilot study was partially determined by funding limitations; however, given the large effect sizes observed in our previous trials in Kenya (Gichangi et al., Citation2018) and Uganda (Korte et al., Citation2020), the sample size of 50 households per village was expected to attain 80% statistical power to observe an increase in testing from 30% to 58%.

Sampling procedure

The study team with village chairman and village health workers prepared a list of more than 100 male-headed households in each village (sampling frames). We randomly selected 50 households in each village using the simple random sampling method. The study team approached each selected household, assessed inclusion criteria, and sought informed consent from the male head of household. This pilot study was open to all adult household members in the visited 50 households in each village.

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for study participants were as follows: all participants must be adults with age of 18 years or older, participants must live in a home with a male head of household, the participant either never tested for HIV or last tested for HIV at least 3 months ago, either negative HIV status, don’t know / don’t remember or test results was indeterminate, lives in selected village, agreed to be followed up over the one-month period of the study, and provided informed consent to participate in the study.

Description of intervention

For both the intervention and control sites, we performed community sensitization on the need for HIV testing. In addition, in the intervention arm, trained village health workers (VHW) administered questionnaires in a confidential and private setting to the male head of household, to his spouse and any adult in the household, and offered HIV oral self-testing (OST) kit (OraQuick HIV Self-Test). VHW utilized tablets to administer the questionnaires which were translated in Swahili language. Tanzania literacy rate for 2018 was 78% (Nantembelele & Gopal, Citation2018). The VHW provided a brief demonstration of an oral test kit usage to the head of household. The VHW left HIV OST kits at the home with detailed pre-test counseling and instructions manual in the Swahili language for use of the kit and actions to take in response to a positive or negative test result. The OraQuick HIV Self-Test was an in-vitro diagnostic medical device that is used for self-testing of antibodies for HIV-1 and HIV-2 in oral fluid. It was documented that the sensitivity and specificity of the OraQuick HIVST were 99.5% (95%CI: 97.26–99.99) and 100% (95%CI: 98.18–100.0), respectively (Belete et al., Citation2019). The information brochure of the product is explained elsewhere(Devillé & Tempelman, Citation2019). The VHW returned to the household one day after the initial visit or at any day and time convenient to the household member to collect initial data on the test kits used and test results. The test results were defined as follows; if there was one line next to the “C” and no line next to the “T”, the result is negative, if there are two complete lines, one next to the “C” and any line next to the “T”, the positive, any indicator that wasn’t a clear-cut positive or negative result was ambiguous result.

If participants tested positive via self-test, they were instructed to visit the care and treatment clinic at Bagamoyo District Hospital where they found the research assistant and health care worker for the confirmatory HIV tests and linkage to HIV treatment and care.

Data collection

Data were collected between December 2019 and February 2020. Tablet-based open data kit (ODK) forms were used to capture study information. Before data collection, we trained village health workers and research assistants for one week. In both study arms, the baseline questionnaire assessed HIV testing history, HIV knowledge, and basic sociodemographic information including education, employment, medical history, and measures of household wealth. The questionnaire was administered to male and female adult participants in the household. In both study arms, we followed-up the enrolled households after a one-month period to assess testing acceptability, testing uptake, testing results (if could not be collected previously), disclosure of results, and linkage to care among those testing positive.

Pre-test counseling

Counseling and test instructions were aligned to the Tanzania national guidelines for the management of HIV and AIDS (NACP, Citation2015). The pre-test counseling included: basic HIV education, benefits of testing and disclosure, and options for further support. Participants were advised to seek confirmatory testing if the self-test result was positive or ambiguous results.

Data analysis

We compared individuals from the two villages to evaluate balance between the villages on key factors that may relate to HIV testing, including baseline testing behavior, and socioeconomic status. A two-proportion z-test was applied to compare two proportions of intervention and control to see if they were the same at baseline. We constructed a social economic status (SES) index with principal component analysis (PCA). The households’ assets used to calculate the SES index with PCA were a piece of land, chickens, ducks, goats, sheep, cows, a TV, a radio, a bicycle, a motorcycle, a car, and a mobile phone. The PCA is a multivariate statistical technique used to reduce the number of variables in a data set into a smaller number. The main steps in constructing a SES index in this analysis were as follows; selection of households’ assets, application of PCA, interpretation of results, and classification of households into five socio-economic groups (Vyas & Kumaranayake, Citation2006). The primary outcome was HIV testing uptake, defined as the proportion of study participants who tested for HIV by any means during the one-month follow-up (HIV oral self-testing, clinic-based testing, or other means). In our primary analysis, we estimated the impact of HIV self-testing availability, by comparing HIV testing uptake in the two intervention arms. We fit log-linear models to estimate relative risk (RR) for HIV testing with and without intervention.

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance and research permits were obtained from the Ifakara Health Institute Review Board (IHI/IRB/No: 38 - 2018) and the National Ethical Committee of Mainland Tanzania (NIMR/HQ/R.8a/ Vol. IX/3142). We gave adequate information about the study and their participation in it to potential participants so they could make an informed decision. Participants were given a copy of the consent form to keep for their own records. Individual written informed consent was obtained from the participants. International Ethical Standards for Biomedical Research Involving Human Persons were followed in this work (CIOMS, Citation2002).

Results

Study participants involved

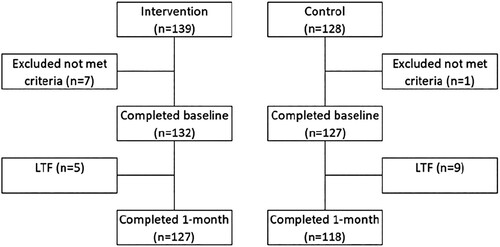

We screened a total of 267 people, and 8 of them were ruled out since they were not eligible. Consequently, there were 259 participants at the start of the study (139 – intervention; 128 – control). At the one-month follow-up visit, there were 14 people lost to follow-up, leaving 245 participants (127 – intervention; 118 – control) ().

Baseline characteristics for study participants

Overall, the baseline characteristics for the intervention and control were comparable (). In total, 259 participants were enrolled in the study. Of participants, 138 (53.3%) were female, 75 (29%) were age 45 years or older, 177 (68.3%) were married, and 31 (12%) reported an education attainment of secondary school or higher. The majority 188 (72.6%) of participants were employed and the distribution of households’ wealth across groups was very similar, ranging from 18.5% of them in the lowest quintile to 20.9% in the highest quintile, .

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of study participants (N = 259).

HIV testing experience and history among enrolled participants

At study baseline, there was high interest in testing for HIV, with all participants (100%; 259/259) reporting that they would like to test for HIV. The majority of the participants reported that they knew a place(s) where they can test for HIV (97.7%; 253/259). However, only one-third (31.3%; 81/259) of study participants knew their HIV status. More than two-thirds (78.4%; 203/259) of the study participants reported that they had ever tested for HIV. More than 90% of those interviewed said that they would notify their spouses or partners if they tested positive for HIV. Only 22.4% (58/259) of participants in the study agreed that getting tested for HIV at a clinic takes a long time ().

Table 2. HIV testing experience and history among study participants at baseline (N = 259).

Acceptability of HIV testing between intervention and control arm

After one-month follow-up, overall, 66.1% (162/245) of study participants reported to have tested for HIV across both arms. In the intervention arm, 97.6% (124/127) reported testing for HIV, while in the control arm, 32.2% (38/118) reported testing. Overall, during the one-month follow-up, study participants in the intervention arm were 3 times more likely to test for HIV compared to study participants in the control arm [RR = 3.0, 95% CI: 2.3–3.9, p-value < 0.001]. Examining subgroup analyses by sex, we found that among men, participants in the intervention arm were 3.2 times more likely to test for HIV than control participants [RR = 3.2, 95% CI: 2.2–4.9, p-value < 0.001]. Similarly, among women, intervention participants were 2.9 times more likely to test for HIV than control participants [RR = 2.9, 95% CI: 2.0–4.0, p-value < 0.001] ().

Table 3. Acceptability of HIV testing between intervention and control arm after one-month follow-up.

Uptake of the HIV oral self-testing kit

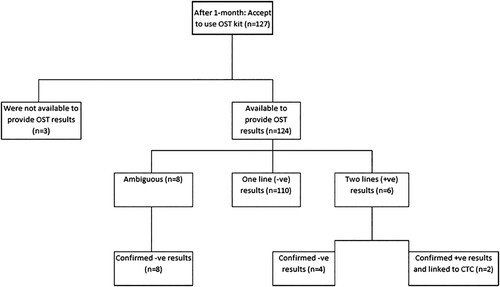

In the intervention arm, a total of 127 study participants used the HIV oral self-testing kit for testing HIV infection over the one-month follow-up period. Of which, 3 study participants were not available to provide OST results (2.4%) while 124 study participants were available to provide OST results (97.6%). Of which, 110 were found to be negative (88.7%), 6 were found to be positive (4.8%), and 8 were found to have ambiguous results (6.5%). Confirmatory tests for positive and ambiguous results revealed that all ambiguous results were negative, and only two of the six participants tested positive on confirmatory testing. Both of these two participants were referred to an HIV clinic for routine care (). Relating to usage experience of the HIV oral self-testing kit among 127 participants, of these participants 121 (95.3%) tested themselves, 5 (3.9%) tests were performed by village health workers, and 1 (0.8%) was performed by the spouse/partner. More than 90% of study participants reported that the kit’s instructions were somewhat difficult to understand ().

Figure 2. Uptake of the HIV oral self-testing kit in the intervention arm (N = 127). Footnote; -ve = negative, +ve = positive, OST = oral self-testing.

Table 4. Experience of the HIV oral self-testing kit in the intervention arm (N = 127).

Discussion

We found that the HIV OST uptake and acceptability was more than 95% among both female and male rural community members in Tanzania. These pilot findings suggest that HIV OST could be a useful technique for increasing HIV testing rates in Tanzanian rural community households. Surprisingly, practically every participant in the intervention arm tested for HIV infection utilizing the OST kits, with only less than 5% being tested by village health workers. A similar study in Uganda found that 77% of couples used HIV self-testing kits (Korte et al., Citation2020), while studies in Kenya revealed that 83% (Gichangi et al., Citation2018) and 90.8% (Masters et al., Citation2016) of male partners used HIV self-testing kits, and 84% of community pharmacy clients used HIV self-testing kits (Mugo et al., Citation2017). All of these studies demonstrated that the availability of HIV self-testing appears to trigger huge increases in HIV testing among different groups of people. Our study results are consistent with this finding, despite the fact that most of our participants did not report that clinic-based testing took a long time.

On the other hand, our findings revealed that routine clinic-based HIV testing remained low among participants in the control group (32.2%), even after the baseline testing campaign implemented as part of this study. The findings of limited uptake of routine HIV testing were similar to those of a Ugandan study (37.2%) (Korte et al., Citation2020). Another study carried out in Tanzania revealed a 9% uptake for conventional clinic-based VCT and a 37% uptake for community-based VCT (Sweat et al., Citation2011). A study conducted in Malawi discovered that there are factors in VCT strategies that may mitigate the fear of HIV testing. Some known factors stated that when people were aware of their positive results they would be stigmatized and lose their lives as a result of having a sickness. They also worry about the pain of the finger prick and the amount of blood that will be extracted (Angotti et al., Citation2009). Other study conducted in Tanzania showed that participants fear of their results during HIV testing at health facility (Sanga et al., Citation2015). These findings suggest the need for ministries of health to reassess routine HIV testing methods to allow a greater number of people to visit a health facility for HIV testing. However, the ministries need to be made aware of HIV stigma, travel time to an HIV clinic, and false beliefs about the nature of HIV testing in a health facility (Chin, Citation2007).

In terms of HIV testing experience and history, we discovered that all participants, regardless of which rural community they came from, wanted to be tested for HIV. This result indicates that members of the community are willing to get tested for HIV. Furthermore, practically all the study participants were aware of where HIV testing could be done. Only one-third of the individuals were aware of their HIV status; however, about 95% of individuals reported they would voluntarily notify their sex partners. According to a study done in Malawi, 91.9% of men and 84.4% of women informed their spouse of the results of their HIV test (Anglewicz & Chintsanya, Citation2011). However, a study conducted in China revealed that only 13% of participants chose to disclose HIV status to their spouse (Li et al., Citation2007).

Only two of the six people who tested positive via self-testing, and had a confirmatory test at the clinic, were found to be positive cases and linked to HIV clinic. We found only 6% of the test results were ambiguous. The ambiguous results could be due to participants having challenges to follow the instructions for using the kit. Given this finding, further validation of the oral self-test may be needed in the Tanzanian setting. However, a study conducted in Ethiopia showed that the sensitivity and specificity of the OraQuick HIVST were 99.5% (95%CI: 97.26–99.99) and 100% (95%CI: 98.18–100.0), respectively (Belete et al., Citation2019). To date, there is no empirical evidence on the performance of the HIVST in Tanzania.

The study’s strengths include the community-randomized design of the intervention pilot study, conducted in a rural setting in Tanzania. We tested a novel intervention in which HIVST was offered to the intervention arm participants, with more than 90% of them testing themselves for HIV. The HIVST technique appears to be feasible in a rural situation. Limitations of the study include the small sample size and limited number of communities. This may limit the generalizability of the results to a wider rural and urban population, especially in terms of conducting HIVST. It also may reduce the likelihood that a statistically significant result reflects a true effect (Button et al., Citation2013). It is critical to understand the acceptability and impact of HIV self-testing in both rural and urban settings.

In Tanzania, HIV self-testing seems to be highly acceptable, with robust uptake of HIVST in a rural population. Still, further proof about HIVST’s performance in Tanzanians is needed. On a bigger scale, more implementation research is needed to look at uptake, yield, and care linkage.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the research assistant and village health workers who collected data for this study. The study is funded by Medical University of South Carolina, U.S.A. A.M., J.K. and O.J., were responsible for the conceptual design of the study and contributed to the initial design of the study. SM. and Village health workers; were collected data. AM and IK., cleaned and analyzed data. A.M., J.K., O.J. and DFC, were provided guidance throughout data collection, cleaning and analysis. AM was drafted the first manuscript; all authors revised and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anglewicz, P., & Chintsanya, J. (2011). Disclosure of HIV status between spouses in rural Malawi. AIDS Care, 23(8), 998–1005. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2010.542130

- Angotti, N., Bula, A., Gaydosh, L., Kimchi, E. Z., Thornton, R. L., & Yeatman, S. E. (2009). Increasing the acceptability of HIV counseling and testing with three C's: Convenience, confidentiality and credibility. Social Science & Medicine, 68(12), 2263–2270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.02.041

- Belete, W., Deressa, T., Feleke, A., Menna, T., Moshago, T., Abdella, S., Hebtesilassie, A., Getaneh, Y., Demissie, M., Zula, Y., Lemma, I., Mamo, G., Workalemahu, E., Kifle, T., & Abate, E. (2019). Evaluation of diagnostic performance of non-invasive HIV self-testing kit using oral fluid in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: A facility-based cross-sectional study. PLoS One, 14(1), e0210866. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210866

- Button, K. S., Ioannidis, J., Mokrysz, C., Nosek, B. A., Flint, J., Robinson, E. S., & Munafò, M. R. (2013). Power failure: Why small sample size undermines the reliability of neuroscience. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 14(5), 365–376. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3475

- Cawley, C., Wringe, A., Isingo, R., Mtenga, B., Clark, B., Marston, M., Todd, J., Urassa, M., & Zaba, B. (2013). Low rates of repeat HIV testing despite increased availability of antiretroviral therapy in rural Tanzania: Findings from 2003-2010. PLoS One, 8(4), e62212. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0062212

- Cawley, C., Wringe, A., Todd, J., Gourlay, A., Clark, B., Masesa, C., Machemba, R., Reniers, G., Urassa, M., & Zaba, B. (2015). Risk factors for service use and trends in coverage of differentHIVtesting and counselling models in northwest Tanzania between 2003 and 2010 Tropical Medicine & International Health, 20(11), 1473–1487. https://doi.org/10.1111/tmi.12578

- Chin, J. (2007). The AIDS pandemic: The collision of epidemiology with political correctness. Radcliffe Publishing.

- Choko, A. T., Desmond, N., Webb, E. L., Chavula, K., Napierala-Mavedzenge, S., Gaydos, C. A., Makombe, S. D., Chunda, T., Squire, S. B., French, N., Mwapasa, V., & Corbett., E. L. (2011). The uptake and accuracy of oral kits for HIV self-testing in high HIV prevalence setting: A cross-sectional feasibility study in Blantyre, Malawi. PLoS Medicine, 8(10), e1001102. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001102

- CIOMS (2002). “International ethical guidelines for biomedical research involving human subjects.” Bulletin Medical Ethics 182: 17-23.

- Conserve, D. F., Issango, J., Kilale, A. M., Njau, B., Nhigula, P., Memiah, P., Mbita, G., Choko, A. T., Hamilton, A., & King, G. (2019). Developing national strategies for reaching men with HIV testing services in Tanzania: Results from the male catch-up plan. BMC Health Services Research, 19(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4120-3

- Conserve, D. F., Muessig, K. E., Maboko, L. L., Shirima, S., Kilonzo, M. N., Maman, S., & Kajula, L. (2018). Mate Yako Afya Yako: Formative research to develop the Tanzania HIV self-testing education and promotion (Tanzania STEP) project for men. PLoS One, 13(8), e0202521. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202521

- Devillé, W., & Tempelman, H. (2019). Feasibility and robustness of an oral HIV self-test in a rural community in south-Africa: An observational diagnostic study. PLoS One, 14(4), e0215353. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0215353

- Ehrenkranz, P., Rosen, S., Boulle, A., Eaton, J. W., Ford, N., Fox, M. P., Grimsrud, A., Rice, B. D., Sikazwe, I., & Holmes, C. B. (2021). The revolving door of HIV care: Revising the service delivery cascade to achieve the UNAIDS 95-95-95 goals. PLoS Medicine, 18(5), e1003651. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003651

- Gichangi, A., J. Wambua, S. Mutwiwa, R. Njogu, E. Bazant, J. Wamicwe, R. Wafula, C. J. Vrana, D. R. Stevens and M. Mudany (2018). “Impact of HIV self-test distribution to male partners of ANC clients: Results of a randomized controlled trial in Kenya.” JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999) 79(4): 467. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000001838

- Isingo, R., Wringe, A., Todd, J., Urassa, M., Mbata, D., Maiseli, G., Manyalla, R., Changalucha, J., Mngara, J., Mwinuka, E., & Zaba, B. (2012). Trends in the uptake of voluntary counselling and testing for HIV in rural Tanzania in the context of the scale up of antiretroviral therapy. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 17(8), e15–e25. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02877.x

- Kalichman, S. C., Shkembi, B., Wanyenze, R. K., Naigino, R., Bateganya, M. H., Menzies, N. A., Lin, C.-D., Lule, H., & Kiene, S. M. (2020). Perceived HIV stigma and HIV testing among men and women in rural Uganda: A population-based study. The Lancet HIV, 7(12), e817–e824. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(20)30198-3

- Kaufman, M. R., Massey, M., Tsang, S. W., Kamala, B., Serlemitsos, E., Lyles, E., & Kong, X. (2015). An assessment of HIV testing in Tanzania to inform future strategies and interventions. AIDS Care, 27(2), 213–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2014.963007

- Killewo, J., Nyamuryekunge, K., Sandström, A., Bredberg-Râdán, U., Wall, S., Mhalu, F., & Biberfeld, G. (1990). Prevalence of HIV-1 infection in the Kagera region of Tanzania Aids (london, England), 4(11), 1081–1086. https://doi.org/10.1097/00002030-199011000-00005

- Korte, J. E., Kisa, R., Vrana-Diaz, C. J., Malek, A. M., Buregyeya, E., Matovu, J., Kagaayi, J., Musoke, W., Chemusto, H., Mukama, S. C., Ndyanabo, A., Mugerwa, S., & Wanyenze, R. K. (2020). Hiv oral self-testing for male partners of women attending antenatal care in central Uganda: Uptake of testing and linkage to care in a randomized trial. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 84(3), 271–279. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000002341

- Kurth, A. E., Cleland, C. M., Chhun, N., Sidle, J. E., Were, E., Naanyu, V., Emonyi, W., Macharia, S. M., Sang, E., & Siika, A. M. (2016). Accuracy and acceptability of oral fluid HIV self-testing in a general adult population in Kenya. AIDS and Behavior, 20(4), 870–879. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-015-1213-9

- Li, L., Sun, S., Wu, Z., Wu, S., Lin, C., & Yan, Z. (2007). Disclosure of HIV status is a family matter: Field notes from China. Journal of Family Psychology, 21(2), 307–314. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.21.2.307

- Masters, S. H., Agot, K., Obonyo, B., Napierala Mavedzenge, S., Maman, S., & Thirumurthy, H. (2016). Promoting partner testing and couples testing through secondary distribution of HIV self-tests: A randomized clinical trial. PLoS Medicine, 13(11), e1002166. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002166

- Mathews, A., Farley, S., Conserve, D. F., Knight, K., Le”Marus, A., Blumberg, M., Rennie, S., & Tucker, J. (2020). Correlates, facilitators and barriers of physical activity among primary care patients with prediabetes in Singapore – a mixed methods approach BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7969-5

- Mugo, P. M., Micheni, M., Shangala, J., Hussein, M. H., Graham, S. M., Rinke de Wit, T. F., & Sanders, E. J. (2017). Uptake and acceptability of oral HIV self-testing among community pharmacy clients in Kenya: A feasibility study. PLoS One, 12(1), e0170868. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0170868.

- NACP (2015). NATIONAL GUIDELINES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF HIV AND AIDS. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, MINISTRY OF HEALTH AND SOCIAL WELFARE.

- NACP. (2021). Anc HIV sentinel surveillance report. DODOMA, National AIDS Control Programme.

- Nantembelele, F. A. and S. Gopal (2018). “Assessing the challenges to e-commerce adoption in Tanzania” Global Business and Organizational Excellence 37(3): 43-50. https://doi.org/10.1002/joe.21851

- NBS (2017). TANZANIA HIV IMPACT SURVEY 2016-2017. National Bureau of Statistics.

- Pai, N., P and K. Dheda (2013). “HIV self-testing strategy: The middle road.” Expert Review of Molecular Diagnostics 13(7): 639-642. https://doi.org/10.1586/14737159.2013.820543

- Sanga, Z., Kapanda, G., Msuya, S., & Mwangi, R. (2015). Factors influencing the uptake of voluntary HIV counseling and testing among secondary school students in Arusha city, Tanzania: A cross sectional study. BMC Public Health, 15(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1771-9

- Sing, R., & Patra, S. (2015). What factors are responsible for higher prevalence of HIV infection among urban women than rural women in Tanzania? Ethiopian Journal of Health Sciences, 25(4), 321–328. https://doi.org/10.4314/ejhs.v25i4.5

- Sweat, M., Morin, S., Celentano, D., Mulawa, M., Singh, B., Mbwambo, J., Kawichai, S., Chingono, A., Khumalo-Sakutukwa, G., & Gray, G. (2011). Community-based intervention to increase HIV testing and case detection in people aged 16–32 years in Tanzania, Zimbabwe, and Thailand (NIMH project accept, HPTN 043): a randomised study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 11(7), 525–532. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70060-3

- TACAIDS (2018). Tanzania commission for AIDS (TACAIDS), Zanzibar AIDS commission (ZAC). Tanzania HIV impact survey (THIS) 2016-2017. National Bureau of Statistics.

- Theuring, S., Jefferys, L. F., Nchimbi, P., Mbezi, P., & Sewangi, J. (2016). Increasing partner attendance in antenatal care and HIV testing services: Comparable outcomes using written versus verbal invitations in an urban facility-based controlled intervention trial in mbeya, Tanzania. PLoS One, 11(4), e0152734. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0152734

- Vyas, S., & Kumaranayake, L. (2006). Constructing socio-economic status indices: How to use principal components analysis. Health Policy and Planning, 21(6), 459–468. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czl029

- Wringe, A., Floyd, S., Kazooba, P., Mushati, P., Baisley, K., Urassa, M., Molesworth, A., Schumacher, C., Todd, J., & Zaba, B. (2012). Antiretroviral therapy uptake and coverage in four HIV community cohort studies in sub-saharan Africa Tropical Medicine & International Health, 17(8), e38–e48. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02925.x