?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is an effective HIV prevention tool, recommended for persons at substantial risk for HIV, such as female sex workers (FSW) and men who have sex with men (MSM). We present Morocco's and the Middle East/North Africa's first PrEP demonstration project. Our pilot aimed to assess the feasibility and acceptability of a community-based PrEP program for FSW and MSM in Morocco's highest HIV prevalence cities: Agadir, Marrakech, and Casablanca. From May to December 2017, 373 eligible participants engaged in a 5–9 month program with daily oral TDF/FTC and clinic visits. Of these, 320 initiated PrEP, with 119 retained until the study's end. We report an 86% PrEP uptake, 37% overall retention, and 78% retention after 3 months. No seroconversions occurred during follow-up. These results underscore PrEP's need and acceptability among MSM and FSW and demonstrate the effectiveness of a community-based PrEP program in Morocco. These findings informed Morocco's current PrEP program and hold potential for the wider region with similar challenges.

Introduction

As of 2015, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended the use of antiretroviral treatment for people at substantial risk of HIV infection in order to prevent the virus acquisition. This figured the concept of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) that should be offered as an additional prevention choice and part of a combination HIV prevention approaches (condom use, sexual behavior counseling, HIV testing) (Guidelines on When to Start Antiretroviral Therapy and on Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis for HIV, Citation2015).

Many studies have been conducted in different countries and regions of the world to demonstrate the efficacy of PrEP (Baeten et al., Citation2012; Fonner et al., Citation2016; McCormack et al., Citation2016; Molina et al., Citationn.d.). Although it can be difficult to precisely quantify the number of avoided transmissions due to PrEP implementation, it is undoubtedly one of the major causes of the reduction of HIV incidence. In London, a 39% decline in infections among men who have sex with men (MSM) has been observed between 2015 and 2018 (New HIV Diagnoses Fall by a Third in the UK since, 2015, n.d.). In France, new cases of HIV dropped by 7% between 2017 and 2018 (Données épidémiologiques VIH/sida France 2019, Citationn.d.). In San Francisco, a dramatic decrease of 44% in new HIV infections has been noted between 2013 and 2017 (The Lancet Hiv, Citation2019).

Despite these achievements, enrolling and maintaining participants into PrEP is challenging. Especially among vulnerable groups that are at extremely high risk of acquiring HIV infection, as reported notably in the Princess PrEP program, that found low PrEP retention rate especially in the 12th month, with a lower adherence among Trans Gender (TG) women (Phanuphak et al., Citation2018). Another study about key and priority populations (fisher folks, truck drivers, and adolescent girls) in South-Central Uganda reported high PrEP uptake percentage but low PrEP retention, especially among men, and a median retention of 45.4 days for both men and women (Muwonge et al., Citation2020).

Faced with these challenges, teams have tried to innovate in order to improve uptake and retention, such as a study among MSM and TG women in Thailand, which analyzed variables related to PrEP uptake and assessed the impact of a novel “Adam's Love Online-to-Offline” (O2O) model on PrEP and HIV testing. Through their pilot, 272,568 people were reached online in 3 months (Anand et al., Citation2017). Besides, “Jilinde Project” aiming to implement oral PrEp as a public routine service in Kenya, showed the feasibility and effectiveness of such approach in promoting PrEP scale-up in low-and middle-income countries (Were et al., Citation2021).

The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region has one of the lowest HIV prevalence in the world (less than 0,1%), with 230,000 people living with HIV in 2020, however, the number of new infections and deaths related to AIDS increases the fastest (Middle East and North Africa, Citationn.d.). Access to effective HIV prevention, testing, and treatment remains also very limited and challenging (Grinsztejn et al., Citation2018). Nevertheless, there is substantial heterogeneity in HIV epidemic dynamics across MENA. Morocco is one of the countries bucking the trend, thanks to the establishment of vast prevention programs targeting people at substantial risk of acquiring HIV and by improving access to treatment and follow-up.

Some groups remain particularly vulnerable and are at extremely high risk of acquiring HIV infection: MSM (with a 4,5% prevalence in 2017 in Morocco), FSWs (1,3%), people who inject drugs (7,9%), and migrants (3%) In Morocco (UNAIDS DATA 2017, Citationn.d.), as in all countries of the MENA region, behaviors such as same-sex relationships, sex work, and drug use are firmly condemned by society, law, and religion creating deeply rooted stigma and discrimination against people living with HIV and key populations (Operario et al., Citation2014; Comprendre et lutter contre la stigmatisation liée au VIH dans la région MENA, Citation2017; Moussa et al., Citation2021).

To strengthen the prevention package intended for key populations, “Association de Lutte Contre le Sida” (ALCS) partnered with the Moroccan Ministry of Health to successfully introduce PrEP in Morocco and conducted, thanks to the support of the Global Fund and The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), in 2017, a demonstration project, PrEPare-Morocco which led to the routine implementation of PrEP since 2017, in Morocco. This paper describes the pilot study which aimed to assess the feasibility and acceptability of a community-based PrEP delivery program for MSM and FSW in Morocco. To our best knowledge, this is the first pilot study in the MENA region on PrEP.

Methods

Study preparation

A Steering Committee was constituted by representatives from the National AIDS Program, UNAIDS Morocco, and the local office of the Global Fund, in addition to the members of the ALCS Research Department. The role of this committee was to provide oversight of the conduct of the study. ALCS’s physicians and peer educators involved in this study were trained for promoting, delivering, and following up on PrEP prescriptions through special training modules elaborated in collaboration between Infectious Diseases physicians and community experts from ALCS. summarizes the PrEP timeline in Morocco.

Study population

The study was conducted among MSM and FSW in the cities with the highest HIV prevalences in Morocco; notably Agadir, Marrakech, and Casablanca.

During the inclusion period, lasting from July to December 2017, all eligible participants visiting ALCS centers, consenting to participate in the study were recruited.

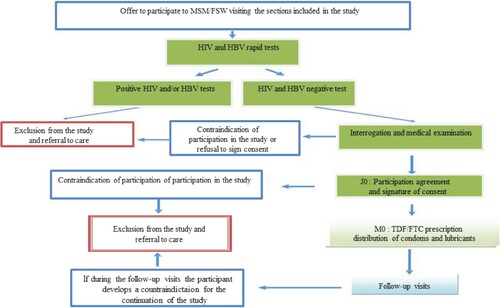

Those who met the inclusion criteria () were invited to a first medical check and were tested for HIV and hepatitis B (HBV). Seronegative individuals for both HIV and HBV were examined by the physician and completed a questionnaire about their sexual behavior.

Table 1. Eligibility criteria.

PrEP delivery and follow-up

PrEP was delivered in ALCS sexual health clinics as an additional prevention choice to other HIV/STIs prevention services already provided by ALCS to MSM and FSW (condoms, lubricant, counseling, HIV testing, etc).

The PrEP regimen proposed in the demonstration study was a single daily tablet containing tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, and emtricitabine. Eligible participants received their dotation of the medicine every month and were monitored till April 2018 with a minimum of 5 months follow-up. Follow-up visits allowed to perform a creatinine clearance test every three months, and to assess potential drug-related adverse effects. Participants were asked to complete a questionnaire about their sexual behavior. At each visit, participants were provided with a comprehensive package of prevention services including free condoms and lube, and they were reimbursed for their travel costs. Process of recruitment is detailed in .

Uptake and retention in PrEP

All PrEP retention indicators were calculated according to WHO guidelines designed to support the implementation of PrEP among a range of populations in different settings (World Health Organization, Citation2018). PrEP uptake is the number of people who initiated PrEP on the number of eligible people who were offered PrEP. Three indicators were also used to measure the retention on PrEP:

PrEP Uptake

Continuation on PrEP

Overall retention

Retention after the critical period

Data analysis

The software EpiData was used to collect and manage data. Univariate analysis was carried out to describe the sample depending on socio-demographic characteristics. Categorical variables are specified as proportions, with percent and confidence intervals (95%). Quantitative variables are represented by median and ranges or mean with IQR.

The data analysis was carried out on Epidata analysis EpiData Analysis V2.2.3.187 and EpiInfo software 7.2.2.6.

Results

Participant’s characteristics

In this study, 396 people (97 FSW and 299 MSM) were recruited. Age of MSM participants ranged from 17 to 63 years, and the median age was 27 years, while FSW participants ages ranged from 19 to 54 years with a median age of 38 years. The level of education varied significantly between participants. Fourteen percent had no formal education, 23% went to primary school, 36% had a high school education and 27% went to university. On average, MSM had a higher level of education than FSW, 77% of MSM attended at least secondary school while 82% of FSW received either no education or only primary education.

At the time of the study, an important proportion of participants reported being unemployed (33%) or having casual employment (28%). On the other hand, 90% of FSW reported being unemployed or having casual employment in contrast with 53% of MSM. Monthly income ranged from 0 to 45,000 MAD ( = 4875$) and the median was 600 MAD ( = 66$). More than 90% of participants were single, divorced, or separated, whereas the remaining 10% were engaged. All the socio-demographic parameters are summarized in .

Table 2. Sociodemographic characteristics of study participants (men having sex with men and female sex workers).

Inclusion in PrEPare_Morocco

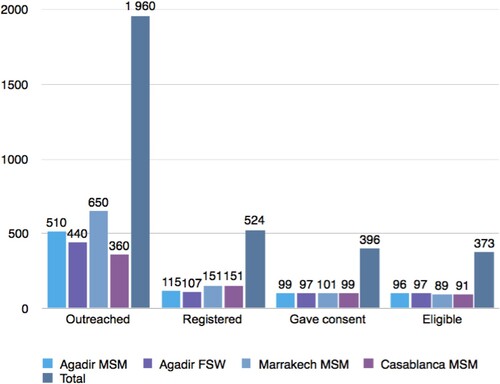

The study planned on recruiting 400 participants, 100 FSW in Agadir and 100 MSM in each of the three cities, Agadir, Casablanca, and Marrakech. During the promotion phase, ALCS informed MSM in the 3 cities and FSW in Agadir about PrEP and assessed their willingness to use it.

About 1,960 people were informed about PrEP (), 524 (417 MSM and 107 FSW) expressed their interest in participating in this study. However, 128 withdraw their approval. All participants signed a consent form to participate and benefit from PrEP. Overall, 373 people were eligible to enter the study. Twenty-three potential participants were excluded: 12 of them were HIV-positive, 8 HBV-positive, whereas 3 had other contraindications. HBV-positive participants were excluded from the present study as, back in 2017, HBV treatment was not widely accessible in Morocco.

Uptake and retention in PrEP

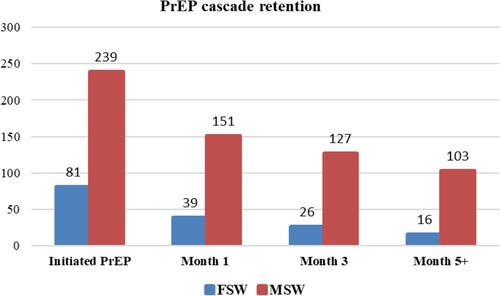

As illustrated in , we report an uptake rate of 86% (320 of participants who initiated PrEP from 373 who were eligible), 86.6% (N = 276) for MSM, and 83.5% for FSW (N = 97). A rate of 48% for continuation on PrEP was registered (153/320) with 26 FSW and 127 of MSM. The overall retention on PrEP was 37% (119/320) (16 of FSW vs 103 of MSM). Furthermore, the retention rate after the critical period was 78% (119/153), 81% among MSM (103/127) vs 62% among FSW (16/26).

In addition, all participants in this study were tested for HIV monthly, with no seroconversion reported, and, creatinine clearance values were also normal throughout the study.

Discussion

Our study assessed the feasibility and the acceptability of a pilot community-based PrEP delivery program for MSM and FSW in Morocco. The uptake of PrEP was very high, reaching 86%, clearly indicating the interest of the key populations (86.6% for MSM, and 83.5% for FSW). This high uptake was similar to other findings, as reported in studies conducted in Senegal and South Africa, where the uptake by FSW was 82.4% and 98%, respectively (Eakle et al., Citation2017; Sarr et al., Citation2020).

As PrEP was unknown to key populations at the time of the implementation of PrEPare_Morocco, the first challenge of this demonstration project was to inform about this new prevention tool and convince the targeted population to engage in the service. Out of the 524 individuals who expressed interest in using PrEP in the promotion phase, 396 actually enrolled in the program, 71% in MSM and 90% in FSW. Studies exploring acceptability reported also high rates among MSM, like in Taiwan 72% (Chuang & Newman, Citation2018), Nigeria 80% (Ogunbajo et al., Citation2019), and Benin 90% (Ahouada et al., Citation2020), as well as for FSW, 60. 3% in U.S.A. (Garfinkel et al., Citation2017), 85,9% in China (Ye et al., Citation2014), and 98% in Kenya (Pintye et al., Citation2020).

Consistent with our results, several studies reported the youthfulness of MSM PrEP users, such as in Benin with an average of 26 years (Ahouada et al., Citation2020), and in Nigeria with an average of 29.2 years (Ogunbajo et al., Citation2019). Moreover, findings on the average age of FSW are similar to other studies in Senegal with an average of 37.7 years (Sarr et al., Citation2020). In contrast, Kenya FSWs were younger (Voeten et al., Citation2007). We also report that 48% of FSWs have no educational level, and only 2% of these women have pursued their education in university, similar to what was reported by a Senegalese study where 41.3% of FSWs were illiterate (Sarr et al., Citation2020).

On the contrary, for MSM, we report a rather advanced level of education compared to FSW, 42% of MSM went to high school and 34% hold a university degree. A study on barriers to PrEP among MSM in Benin showed that 90,5% of them have attended secondary school or higher educational level(Ahouada et al., Citation2020).

Sixty one percent of our participants and 90% of FSWs have no job or a non-formal job; these findings are in agreement with those reported in some Sub-Saharian Africa study among women (Tenkorang, Citation2014). This was confirmed by their low income, 61% of the participants have an income lower than 1500 MAD ( = 165 USD) for 59% of MSM, and 68% of FSW, which is twice lower than the legal minimum wage in Morocco (2,828.71 MAD in 2017) (MACHRAFI, Citationn.d.). Many studies have demonstrated the relationship between low income among women and a high risk of HIV infection (Peragallo et al., Citation2005; Sikkema et al., Citation1996; Whyte IV, Citation2006), and also among MSM (Cáceres et al., Citation2008).

The community-led approach used in PrEPare_Morocco, offering oral PrEP within a whole package of combined prevention, including sexual health services, adherence counseling, and PrEP visit reminders, was successful and has been well accepted by both MSM and FSW. According to the World Health Organization (World Health Organization, Citation2018), the first three months following the initiation of PrEP (Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis) constitute a critical period for users, as it is during this time that the highest number of discontinuations occur. This was confirmed in our study as we observed that the majority of discontinuations occurred during this period. After the critical period, the retention rate was 78%, with 62% for FSW and 81% for MSM.

Moreover, the overall retention rate in our study (37%) was relatively lower than reported in Senegal where 79.9% of FSW were retained in PrEP at 6 months (Sarr et al., Citation2020). In Kenya, the retention rate was lower at one, three, and six months and was only at 40.3%, 26.3% and 14.0% for FSWs, and 32.9%, 21.7%,and 14.8% for MSM (Kyongo, Citationn.d.). In South Africa, retention for FSWs at 3 and 6 months was respectively 44% and 30%, comparable to our findings (Eakle et al., Citation2017). Likewise, in Eswatini, where retention for MSM was also lower than ours, 40% at 3 months, 30% at 6 months (Berner-Rodoreda et al., Citation2020). A study carried out in Cameroon reported that at months 2, 3, 6, 9 and 12, PrEP continuation was 40%, 37%, 28%, 21% and 19%, respectively (Ndenkeh et al., Citation2022).

Limitations of the project

We acknowledge three main limitations to this study. First of all, the small sample, especially since FSW were three times less represented in this sample. Secondly, the participant’s retention was assessed through a self-reporting. The third limitation is that participants were only offered, during this demonstration project, the option of a daily regimen and we weren’t able to assess the on-demand PrEP acceptability and feasibility. However, despite these limitations, this is the very first PrEP demonstration project in a MENA country region and the results obtained were very useful in the subsequent routine implementation process of PrEP strategy among FSW and MSM in Morocco. We believe that the lessons learnt can be extrapolated to other countries of MENA region, sharing similar socio-cultural and religious background.

Conclusion

In the first demonstration project of PrEP in Morocco and the MENA region, we were able to demonstrate the high acceptability of PrEP as an additional prevention tool against HIV infection acquisition for MSM and FSW and as a solid alternative to condom use. We also proved the feasibility of a community-based PrEP delivery program in our settings, notably with the particular socio-cultural and religious background of the MENA Region. More efforts are needed today to increase and expand PrEP community uptake and awareness in Morocco and the MENA region and to develop effective adherence support for key populations.

Abbreviations

ALCS: Association de Lutte Contre le Sida; CI: Confidence Interval; FSW: Female Sex Workers; HBV: hepatitis B; IQR: Inter-Quartile Range; MAD: Dirham Marocain; MENA: the Middle East and North African; MSM: Men who have Sex with Men; PLHIV: The People Living with HIV; STI: Sexually Transmitted Infections; PrEP: Pre-exposure prophylaxis; UNAIDS: The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; WHO: the World Health Organization.

Authors’ contributions

AB led the research and led the writing of the paper. OB contributed to drafting the paper, MS, FH, LO contributed to the interpretation of the data and the development of the idea. NS, contributed in the revision of the paper.

NES, KA, and BE provided critical feedback and helped shape the research, analysis, and manuscript. MK supervised the research and successive drafts of the paper.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The ethics that approved this study are Casablanca Biomedical Research Ethics Committee (IRB00002504) in the Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy of Casablanca at the Hassan II University in Casablanca. Informed written consent was obtained from all participants.

Competing interests

The authors declare to have no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all of the respondents of the key population for their time, contribution, and participation in this study. We additionally like to thank all stakeholders who were instrumental in carrying out this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ahouada, C., Diabaté, S., Mondor, M., et al. (2020). Acceptability of pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention: Facilitators, barriers and impact on sexual risk behaviors among men who have sex with men in Benin. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1267. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09363-4

- Anand, T., Nitpolprasert, C., Trachunthong, D., Kerr, S. J., Janyam, S., Linjongrat, D., Hightow-Weidman, L. B., Phanuphak, P., Ananworanich, J., & Phanuphak, N. (2017). A novel online-to-offline (O2O) model for pre-exposure prophylaxis and HIV testing scale up. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 20(1), 21326. https://doi.org/10.7448/IAS.20.1.21326

- Baeten, J. M., Donnell, D., Ndase, P., Mugo, N. R., Campbell, J. D., Wangisi, J., Tappero, J. W., Bukusi, E. A., Cohen, C. R., Katabira, E., Ronald, A., Tumwesigye, E., Were, E., Fife, K. H., Kiarie, J., Farquhar, C., John-Stewart, G., Kakia, A., Odoyo, J., Mucunguzi, A., … Partners PrEP Study Team (2012). Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. The New England Journal of Medicine, 367(5), 399–410. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1108524

- Berner-Rodoreda, A., Geldsetzer, P., Bärnighausen, K., Hettema, A., Bärnighausen, T., Matse, S., & McMahon, S. A. (2020). It's hard for us men to go to the clinic. We naturally have a fear of hospitals.” men's risk perceptions, experiences and program preferences for PrEP: A mixed methods study in eswatini. PLoS One, 15(9), e0237427. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0237427

- Cáceres, C. F., Konda, K. A., Salazar, X., Leon, S. R., Klausner, J. D., Lescano, A. G., Maiorana, A., Kegeles, S., Jones, F. R., & Coates, T. J. (2008). New populations at high risk of HIV/STIs in low-income, urban coastal Peru. AIDS and Behavior, 12(4), 544–551. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-007-9348-y

- Chuang, D. M., & Newman, P. A. (2018). Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) awareness and acceptability among men who have sex with men in Taiwan. AIDS Education and Prevention: Official Publication of the International Society for AIDS Education, 30(6), 490–501. https://doi.org/10.1521/aeap.2018.30.6.490

- Comprendre et lutter contre la stigmatisation liée au VIH dans la région MENA : Guide pour l’action. Plateforme Elsa. (2017). https://plateforme-elsa.org/comprendre-lutter-contre-stigmatisation-liee-vih-region-mena-guide-laction/ (accessed October 15, 2021).

- Données épidémiologiques VIH/sida France 2019. (n.d.). Sidaction. https://www.sidaction.org/donnees-epidemiologiques-vihsida-france-2019 (accessed October 15, 2021).

- Eakle, R., Gomez, G. B., Naicker, N., Bothma, R., Mbogua, J., Cabrera Escobar, M. A., Saayman, E., Moorhouse, M., Venter, W. D. F., & Rees, H. & TAPS Demonstration Project Team (2017). HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis and early antiretroviral treatment among female sex workers in South Africa: Results from a prospective observational demonstration project. PLoS Medicine, 14(11), e1002444. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002444

- Fonner, V. A., Dalglish, S. L., Kennedy, C. E., Baggaley, R., O'Reilly, K. R., Koechlin, F. M., Rodolph, M., Hodges-Mameletzis, I., & Grant, R. M. (2016). Effectiveness and safety of oral HIV preexposure prophylaxis for all populations. AIDS (London, England), 30(12), 1973–1983. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000001145

- Garfinkel, D. B., Alexander, K. A., McDonald-Mosley, R., Willie, T. C., & Decker, M. R. (2017). Predictors of HIV-related risk perception and PrEP acceptability among young adult female family planning patients. AIDS Care, 29(6), 751–758. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2016.1234679

- Grinsztejn, B., Hoagland, B., Moreira, R. I., Kallas, E. G., Madruga, J. V., Goulart, S., Leite, I. C., Freitas, L., Martins, L. M. S., Torres, T. S., Vasconcelos, R., De Boni, R. B., Anderson, P. L., Liu, A., Luz, P. M., Veloso, V. G., & PrEP Brasil Study Team (2018). Retention, engagement, and adherence to pre-exposure prophylaxis for men who have sex with men and transgender women in PrEP brasil: 48 week results of a demonstration study. The Lancet HIV, 5(3), e136–e145. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(18)30008-0

- Guideline on When to Start Antiretroviral Therapy and on Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis for HIV. (2015). Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Kyongo, J. K. (n.d.). How long will they take it? Oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) retention for female sex workers, men who have sex with men and young women in a demonstration project in Kenya. https://programme.ias2019.org/Abstract/Abstract/1057 (accessed October 15, 2021).

- MACHRAFI K. SMIG Maroc 2021 BLOG OJRAWEB. (n.d.). https://blog.ojraweb.com/gestion-de-la-paie-maroc-valeur-du-smig-au-01-janvier-2021/ (accessed October 26, 2021).

- McCormack, S., Dunn, D. T., Desai, M., Dolling, D. I., Gafos, M., Gilson, R., Sullivan, A. K., Clarke, A., Reeves, I., Schembri, G., Mackie, N., Bowman, C., Lacey, C. J., Apea, V., Brady, M., Fox, J., Taylor, S., Antonucci, S., Khoo, S. H., … Gill, O. N. (2016). Pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent the acquisition of HIV-1 infection (PROUD): Effectiveness results from the pilot phase of a pragmatic open-label randomised trial. Lancet (London, England), 387(10013), 53–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00056-2

- Middle East and North Africa. (n.d.). https://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/middleeastandnorthafrica (accessed October 15, 2021).

- Molina, J.-M. (n.d). Incidence of HIV-infection in the ANRS Prevenir Study in the Paris Region with Daily or On Demand PrEP with TDF/FTC. https://www.natap.org/2018/IAC/IAC_32.htm (accessed October 15, 2021).

- Moussa, A. B., Delabre, R. M., Villes, V., Elkhammas, M., Bennani, A., Ouarsas, L., Filali, H., Alami, K., Karkouri, M., & Castro, D. R. (2021). Determinants and effects or consequences of internal HIV-related stigma among people living with HIV in Morocco. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 163. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10204-1

- Muwonge, T. R., Nsubuga, R., Brown, C., Nakyanzi, A., Bagaya, M., Bambia, F., Katabira, E., Kyambadde, P., Baeten, J. M., Heffron, R., Celum, C., Mujugira, A., & Haberer, J. E. (2020). Knowledge and barriers of PrEP delivery among diverse groups of potential PrEP users in central Uganda. PLoS One, 15(10), e0241399. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241399

- Ndenkeh, J. J. N., Bowring, A. L., Njindam, I. M., Folem, R. D., Fako, G. C. H., Ngueguim, F. G., Gayou, O. L., Lepawa, K., Minka, C. M., Batoum, C. M., Georges, S., Temgoua, E., Nzima, V., Kob, D. A., Akiy, Z. Z., Philbrick, W., Levitt, D., Curry, D., & Baral, S. (2022). HIV Pre-exposure prophylaxis uptake and continuation among key populations in Cameroon: Lessons learned from the CHAMP program. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999), 91(1), 39–46. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000003012

- Ogunbajo, A., Iwuagwu, S., Williams, R., Biello, K., & Mimiaga, M. J. (2019). Awareness, willingness to use, and history of HIV PrEP use among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in Nigeria. PLoS One, 14(12), e0226384. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0226384

- Operario, D., Yang, M.-F., Reisner, S. L., Iwamoto, M., & Nemoto, T. (2014). Stigma and the syndemic of HIV-related health risk behaviors in a diverse sample of transgender women. Journal of Community Psychology, 42(5), 544–557. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.21636

- Peragallo, N., Deforge, B., O'Campo, P., Lee, S. M., Kim, Y. J., Cianelli, R., & Ferrer, L. (2005). A randomized clinical trial of an HIV-risk-reduction intervention among low-income Latina women. Nursing Research, 54(2), 108–118. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006199-200503000-00005

- Phanuphak, N., Sungsing, T., Jantarapakde, J., Pengnonyang, S., Trachunthong, D., Mingkwanrungruang, P., Sirisakyot, W., Phiayura, P., Seekaew, P., Panpet, P., Meekrua, P., Praweprai, N., Suwan, F., Sangtong, S., Brutrat, P., Wongsri, T., Na Nakorn, P. R., Mills, S., Avery, M., … Phanuphak, P. (2018). Princess PrEP program: The first key population-led model to deliver pre-exposure prophylaxis to key populations by key populations in Thailand. Sexual Health, 15(6), 542–555. https://doi.org/10.1071/SH18065

- Pintye, J., Rogers, Z., Kinuthia, J., Mugwanya, K. K., Abuna, F., Lagat, H., Sila, J., Kemunto, V., Baeten, J. M., John-Stewart, G., & Unger, J. A. (2020). Two-way short message service (SMS) communication may increase pre-exposure prophylaxis continuation and adherence among pregnant and postpartum women in Kenya. Global Health, Science and Practice, 8(1), 55–67. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-19-00347

- Sarr, M., Gueye, D., Mboup, A., Diouf, O., Bao, M. D. B., Ndiaye, A. J., Ndiaye, B. P., Hawes, S. E., Tousset, E., Diallo, A., Jones, F., Kane, C. T., Thiam, S., Ndour, C. T., Gottlieb, G. S., & Mboup, S. (2020). Uptake, retention, and outcomes in a demonstration project of pre-exposure prophylaxis among female sex workers in public health centers in Senegal. International Journal of STD & AIDS, 31(11), 1063–1072. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956462420943704

- Sikkema, K. J., Heckman, T. G., Kelly, J. A., Anderson, E. S., Winett, R. A., Solomon, L. J., Wagstaff, D. A., Roffman, R. A., Perry, M. J., Cargill, V., Crumble, D. A., Fuqua, R. W., Norman, A. D., & Mercer, M. B. (1996). HIV risk behaviors among women living in low-income, inner-city housing developments. American Journal of Public Health, 86(8), 1123–1128. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.86.8_pt_1.1123

- Tenkorang, E. Y. (2014). Marriage, widowhood, divorce and HIV risks among women in sub-saharan Africa. International Health, 6(1), 46–53. https://doi.org/10.1093/inthealth/ihu003

- The Lancet HIV. (2019). For the greatest impact, end caps on PrEP access now. The Lancet HIV, 6(2), e67. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(19)30006-2

- UNAIDS DATA 2017. (n.d.). https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2017/2017_data_book (accessed December 6, 2021).

- Voeten, H. A., Egesah, O. B., Varkevisser, C. M., & Habbema, J. D. (2007). Female sex workers and unsafe sex in urban and rural Nyanza, Kenya: Regular partners may contribute more to HIV transmission than clients. Tropical Medicine & International Health: Tm & IH, 12(2), 174–182. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01776.x

- Were, D., Musau, A., Mugambi, M., Plotkin, M., Kabue, M., Manguro, G., Forsythe, S., Glabius, R., Mutisya, E., Dotson, M., Curran, K., & Reed, J. (2021). An implementation model for scaling up oral pre-exposure prophylaxis in Kenya: Jilinde project. Gates Open Research, 5, 113. https://doi.org/10.12688/gatesopenres.13342.1

- Whyte Iv, J. (2006). Sexual assertiveness in low-income African American women: Unwanted sex, survival, and HIV risk. Journal of Community Health Nursing, 23(4), 235–244. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327655jchn2304_4

- World Health Organization. (2018). WHO Implementation tool for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) of HIV infection: module 5: monitoring and evaluation. World Health Organization.

- Ye, L., Wei, S., Zou, Y., Yang, X., Abdullah, A. S., Zhong, X., Ruan, Y., Lin, X., Li, M., Wu, D., Jiang, J., Xie, P., Huang, J., Liang, B., Zhou, B., Su, J., Liang, H., & Huang, A. (2014). HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis interest among female sex workers in Guangxi, China. PloS one, 9(1), e86200. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0086200