ABSTRACT

In a period characterised by worries over the rise of the corporate university, it is important to ask what role feminism plays in the academy, and whether that role is commensurate with feminist values and ethics. Commercial and political pressures brought to bear on the encounter between instructor and student can rob teaching of its efficacy, and the effects of institutional limitations on research may be equally troublesome. This essay argues that through a process-model approach, feminists can understand and intervene in ongoing shifts in institutional governance and mitigate their effects on teaching and research, and that process-model pedagogy is a form of microactivism existing independent of pedagogical content, making process-model feminism fundamentally materialist, radically strategic, and highly portable. Through a discussion of pedagogical and administrative practices in which process-model feminism can intervene, this essay suggests a way of understanding and inhabiting feminism’s current place in the ‘corporate’ academy.

One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman (Simone de Beauvoir).

While academic feminism has by now achieved duration, its history has certainly not been uneventful. Contention has always characterised institutions of higher education, and feminists have had to fight hard to claim a place there. This fight began to achieve visibility in the late 1960s when second-wave feminist activists began, in the words of Rudi Dutschke, a ‘long march through the institutions’, and in our current moment it is again necessary to consider the relationship among feminism, activism, and institutions of higher education. This is true for four reasons. The first is global: institutions exert enormous influence over individuals as primary repositories of economic, military, and political power at a time in which the only organised counterweight to supranational corporations and their associated institutions are national governments and theirs; any feminist interested in fostering social change needs to give institutions their careful attention.Footnote1 The second is local: in the US, specific institutions – colleges and universities – function as gatekeepers for other institutions, meaning that US higher education is tasked with providing a controlled path for individual access to the power concentrated in governmental and corporate institutions.

The third is historical: in addition to their gatekeeping duties, institutions of higher education in the U.S. and the feminist academics that work in them are charged with shaping students into viable citizens. As my own university’s seal proclaims, Disciplina Praesidium Civitatis; the words are a loose translation of Mirabeau B. Lamar’s famous words: ‘a cultivated mind is the guardian genius of democracy’. However, the ‘purpose’ of American higher education has never been settled, as I state above, nor has lasting control ever rested with any of the parties Geiger argues have historically pursued it: state legislators, city and county politicians, religious denominations, business interests, and the institutions of higher education themselves (Citation2005, Citation2015).

The fourth reason to reconsider the relationship between academic feminism and the academy is logistical. If the historical process of contention over control of U.S. higher education currently favours business interests, as critical pedagogy and university studies scholars sometimes claim, it is important both to ask how we know whether this trend is occurring in specific institutions and what response academic feminists ought to make to it. Here, I will ask how (or whether) feminist pedagogues can ethically carry out the twin tasks of higher education – teaching and research – in the institutional settings we are in, and what the effect of the effort may be on our praxis. I will argue that by attending to the processes of education rather than the products, we can expand our understanding of academic feminist praxis and take part in ongoing institutional change without being subsumed thereby.

To accomplish this, I will first examine the macro- and micro-context of U.S. collegiate institutions in order to define the ‘corporate university’ and better understand what effects corporate universities have on research and teaching, followed by an explanation of what process-model feminism is and how I apply it in teaching. To relate these two topoi, I will clarify what I see as the most problematic aspects of product-oriented epistemology and teaching, how they affect both students and teachers at corporate universities, and how process-model teaching and research can intervene. I will also explain how I understand process-model methodologies as at least potentially feminist and what advantages these methodologies have in feminist teaching and research, especially if the task of academic feminism is understood as combining intervention in problematic aspects of the ‘corporate university’ with a limited accommodation of some of its larger goals.

The institutional landscape of American colleges and universities

To locate the ‘corporate university’ as an object of inquiry necessitates a brief historiography of U.S. institutions of higher education, especially in terms of who attended and in what numbers. We know that spending has fallen while enrollments are up, and that tuition rates have been hiked as a result; however, this information lacks context. Especially after the first and second world wars, collegiate enrollment saw significant increase: from 1945 to 1970 the proportion of 18- to 21-year-olds attending college went from 15.5% to 45%, and in the 1960s the growth of the age cohort, added to the percentage of that cohort attending college, indicates the sizable national enrollment increase ().

Figure 1. ‘U.S. Total Enrollment, Fall Semester 1947–2012’. Source: National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) Digest of Education Statistics, 2013.

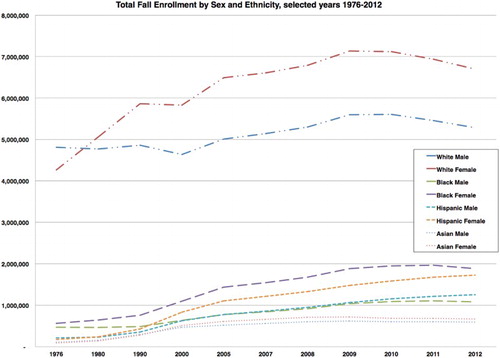

As community colleges opened at the rate of one per week in the late 1960s and the desegregation movement began to affect enrollment, a more diverse population of students than ever before attended institutions receiving relatively high levels of public non-military funding, with a growing emphasis on a general or ‘liberal arts’ education ().

Figure 2. ‘Total Fall Enrollment by Sex and Ethnicity, selected years 1976–2012’. Source: National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) Digest of Education Statistics 2013.

By the 1970s, many university humanities programmes could no longer ignore the cultural and intellectual importance of feminism, and through the 1980s in the U.S. and Canada there remained hope that feminist praxis would transform higher education. Consider these words from 1984’s Knowledge Reconsidered: A Feminist Overview:

From its roots in a distinctive perception, feminist research is creating a new knowledge … [and it] will help to create, in terms of philosophy, content, structure, a new education. Together, the new knowledge and the new education will change our views of society … With knowledge, and education, and time, we may, someday, create a new society. (Gow Citation1984, vii)

In service of this vision Women’s and Gender Studies departments were formed as feminist scholarship continued to demonstrate its importance to various disciplines, and the culture wars of the 1980s and 1990s seemed to confirm the activist potential of academic feminist insights.

Unexpectedly, the years of early feminist encroachment on the U.S. academy were marked by enrollment stagnation, with only a 1% yearly increase in enrollment from 1975 through 1995. Additionally, passage of the Middle Income Student Assistance Act in 1978 began the process of making student loans the linchpin of institutional economics at almost the same time that real spending per student peaked. The effect has been an increased stratification of higher education, and regional campuses and community colleges have been hardest hit by the decrease in state spending.

Throughout this time, my own campus, a large ‘research’ university and the flagship of a state university system, has grown steadily. From 27,345 students enrolled in Fall 1970 to 51,313 in Fall 2014, the university’s size has doubled, with a peak enrollment of 52,261 in Fall 2002 (). Interestingly, enrollment of men during the period has remained fairly constant since 1970 with peak enrollment in 1991 of 27,166, women’s enrollment outstripping this figure for the first time in 2002 and remaining above men’s since. It is striking that men’s enrollment has only risen by 2000 since 1970, suggesting that the general enrollment trend at the university that employs me mirrors that of its women students, that outreach to men is ineffective in getting greater numbers of them on campus, and that my university should be paying more attention to the female undergraduates whose increase in enrollment maps almost perfectly onto the university’s. Nationally, the inclusion of ethnicity data (see ) indicates that black and Hispanic women’s enrollment is similar in trend, if much lower in number.

Figure 3. Fall Semester Enrollment by Sex, 1966–2014. Source: Office of the Registrar/University of Texas Office of Information Management and Analysis.

Clearly, U.S. colleges and universities are enrolling more students than ever before. This is expected to continue (see ) alongside dwindling state financial support for post-secondary classroom instruction, which contention is supported by the NASBO (Citation2013) report:

Enrollments are growing, and to meet future goals for increased degree attainment, they will need to continue to grow for the foreseeable future. Meanwhile, state expenditures for higher education have been declining on a per capita basis and as a percentage of state appropriations in recent years, but they still continue to be major source [sic] of operating revenue for public higher education institutions. As state funds have declined, institutions have sought more independence while also shifting costs on to student tuitions and fees. Tuitions are rising much more rapidly than spending, and while students are paying more, in many cases, less is being spent on them. Over time, spending on instruction has declined slightly, administrative and general support costs have increased, and institutions’ use of various ‘cross-subsidies’ has grown increasingly common.

State government budgeting and financing practices have been evolving, and a growing number of states have experimented with and/or implemented some form of performance-based or outcomes-based budgeting models for higher education, as well as other spending areas. ( … ) Performance funding approaches have emerged as a compelling strategy for states to exercise more control over and build consensus on the goals of public higher education institutions, though this practice alone will not address the underlying cost structural problems facing this nation’s higher education sector. (30)

Figure 4. ‘US Total Undergraduate Fall Enrollment in Degree-Granting Postsecondary Institutions by Attendance Status’. Source: Table 303.70, “Total undergraduate fall enrollment in degree-granting postsecondary institutions, by attendance status, sex of student, and control and level of institution: selected years, 1970 through 2023” National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) Digest of Educational Statistics. Note: * All values after 2014 are projected.

The economistic language and the report’s dependence on a rhetoric of rationalisation and efficiency points to a larger dynamic: a shift away from Mirabeau B. Lamar’s civic-democratic vision of the university and towards a vision of institutions of higher education as efficient producers of … what? Understandably, a group dedicated to budgets focuses on budgets, but it is striking that in the entire report, there is no mention of the purpose or texture of the rationalised education it suggests that colleges and universities produce. This is because it goes without saying: the goal of a ‘corporate’ university is to provide an efficient education for an efficient student who will become an efficient institutional subject.

This economistic rationalism incentivises programmes such as Kent State Stark’s ‘The Corporate University at Kent State Stark’, a public/private partnership describing itself thusly:

As your organizational and professional development training partner, The Corporate University at Kent State Stark provides highly experienced and credentialed subject matter experts, competitive pricing, state-of-the-art facilities, convenient locations, quick response and exceptional quality. Hundreds of area organizations from all industries utilize our resources as a global university coupled with personal attention, customized programming and training plans to improve performance metrics. Value-added program tools provide your organization the framework to maximize investments in training and development with a measurable improvement on business metrics. (The Corporate University)

The ruling principles are efficiency, consumability, accountability, and transparency, the imagined audience a customer choosing between products grouped by brand and ranked by ‘value’. While as Ferrell points out, the principles are ‘hard to argue with in principle’ (Citation2011, 166, emphasis in the original), they imagine an audience allergic to unproductive effort that is also a worker under strict economistic pressures.

Nor are these pressures unusual. As Schrecker notes, 75% of U.S. instructors in post-secondary education lack long-term contracts, leaving only 25% of instructors nationally with access to the job security that could allow them to protest educational commercialism (Citation2012, 39). This kind of ‘secure insecurity’ forces instructors to enhance whatever employment assurance they have through strategy based on ‘subtle and hidden forms of constraint on individual agency, similar in form to self-censorship’ that produce ‘forms of adaptive behavior that serve larger goals’ (Subramaniam, Perrucci, and Whitlock Citation2014, 418). This ‘intellectual closure’ limits exposure to harm on the part of academics engaging only in high-reward, low-risk activities meant to prove their ‘worth’ and protect their employment – typically research rather than teaching, and certainly not activism.

It is obvious where intellectual closure and corporate universities intersect: ‘closed’ individuals help corporate institutions climb higher in the rankings by meeting certain criteria (publication in prestigious journals, successful grant applications, and profitable research), which helps the institution attract more money and more ‘productive’ academic labourers. This becomes a self-serving, self-sustaining institutional cycle without much space for teaching, and this is one-way intellectual closure that hurts institutions of higher education and their members: students are taught by instructors without the job security to fully engage in their teaching duties, and the majority of instructors can neither concentrate on teaching nor exercise oversight in their institutions, creating the potential for widespread exploitation. The second way has to do with the effects of intellectual closure on research: securely insecure researchers in corporate universities, aware that they are dispensable workers in a knowledge factory, require themselves – and are required by their departments/disciplines – to churn out consumable product. This has effects both across and within disciplines.

Across the disciplines, the scientific model of research reigns, and specifically the model used by large, grant-driven projects generating prestige and financial gain for the university (Marcus Citation2002). This model works poorly for non-Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) departments and has major effects on university governance:

Given the importance of research (and the reputation and wealth that it brings a university) over other activities, such as teaching, advising or committee work, in defining the prestige of various programs and departments, and given that research follows a natural science model (where, as noted, in the most successful cases such research brings large grants, equipment, and the possibility of lucrative intellectual property ownership as a wealth accelerator for the university), then any needs or differences of the humanities and social sciences must be exceptions, allowances, and frankly, cases of charity. (Marcus Citation2002, 520)

This charity will remain grudging while STEM departments and their close relationships with business provide administrators a model and a rationale for shifting away from teaching and towards research judged to be viable in corporate terms. This ‘viable’ research is often designed to meet specific industry needs, and indeed industry figures now regularly serve on the committees that allocate research funding, as they have done at the University of California at Berkeley (Aronowitz and Giroux Citation2000, 332). So while I do not mean to imply that all universities are becoming industrial satellites and are thus ‘corporate’, I want to be clear that the current debate over the ‘corporate university’ is not simply another example of the historical process of contention over governance in higher education. It is instead a widespread epistemic change, as evidenced by the NASBO report, and requires an epistemic response. Thus, I use ‘corporate university’ here to refer to any educational institution combining a de-emphasis on teaching with a governance system that recognises as legitimate a specific type of research to the detriment of disciplines less clearly ‘practical’ and more difficult to monetise. Additionally, I mean by a ‘corporate university’ one that treats students and instructors like products, and expects them to do likewise. Against this trend I suggest that as feminists and academic labourers it is process, not product, that is the model we should take for our own.

Feminist Praxis: process versus product

Without consequences, the distinction between process- and product-oriented methodologies becomes meaningless, so here I will tentatively suggest what feminist process-model pedagogy and feminist process-model research should look like, and from whence they come. For me an interest in process first emerged from my experience in early childhood education. ‘Process over product’ is a central tenet of developmentally appropriate early childhood education and guides all environmental and pedagogical decisions. Viewing children as individuals engaged in the process of ontogenesis,Footnote2 and viewing ‘education’ as the context in which ontogenesis is best facilitated, radically changes the power dynamics of classrooms and decentres both teacher and curriculum. This, in turn, gives children the freedom to follow their own inclinations and explore their environment in response to intrinsic motivators, and allows teachers to engage in attentive, non-evaluative care that lessens student dependence on extrinsic motivators and product-oriented evaluation. This, in turn, allows children to engage in self-reflection on their own process, the criteria for success simply the ‘fit’ between inclination and outcome. With roots in Vygotskian psychology and Deweyan pragmatism,Footnote3 process-model learning theory is ubiquitous in developmental early childhood education. It is also frequently at odds with the expectations of people whose product-oriented ideas about education and development come from long experience with traditional schooling methods.

As an early childhood educator, I frequently saw the effects of product-model thinking, particularly in parent/teacher conferences where parents asked whether their child hit a developmental milestone ‘on time’ or sought advice on accelerating their child’s development through products such as the Baby Mozart series, ‘educational’ toys, or through repetitious drills. These milestones – crawling, walking, drawing figures, learning colours, numbers, and letters – are all product-oriented criteria for adducing internal developmental processes, and like all such they are sometimes necessary, but deeply imperfect. Some children who are ‘late’ walkers are engaged in ‘early’ speech development, some children lack interest in drawing figures; what product-model thinking misses is that all children are engaged in a learning process that is punctuated by the production of artefacts, and these should be treated as by-products of that process rather than its purpose.

It is often difficult to explain to parents whose strong product-orientation causes them to view child development solely as a process culminating in a state of ‘normality’ that development is continual, individual, non-linear, and difficult to measure. Parents naturally crave reassurance that their children are healthy, capable learners, but this concern easily becomes an obsession. Toddlers with product-oriented parents become kids who ask adults to produce art for them, who judge the success of their play in terms of results, and whose flexibility in the face of struggle is often limited. Praise for these kids is a sign of productivity, often because it focuses on end results: ‘your drawing is so pretty’, or ‘you made a ---!’ Throughout their education, these same children will have their product-orientation strengthened through repetitious internalisation of the same concerns: Are they learning the material at the rate they should? Are they excelling? Can they demonstrate as much on a standardised test? To a degree, this results from the sheer number of students in U.S. schools and the dearth of teachers to educate and assess them, but the process of learning in such a system is often an exercise in strategic mimicry rather than an intrinsically motivated engagement with unfamiliar ideas.

In my current career path, I see similar processes playing out on campus. Particularly for non-Tenure-Track (NTT) and Tenure-Track (TT) faculty, a product-orientation is essential to their survival in a product-oriented institution, producing the intellectual closure discussed above. Students’ adaptive product-orientation can be seen in an overemphasis on grades and in highly strategic effort allocation. ‘Elective’ and required courses, supposedly meant to cultivate students’ love of learning (though actually designed to support departmental finances), become death marches through unread texts and slept-through discussions with students who have carefully calibrated the minimum effort for maximum effect. Nor are they wrong to do so; since 1978 and the introduction of federal student loans, if not before, rising tuition costs have outstripped the inflation rate every year, and every college student is aware that earning that expensive diploma translates to a host of benefits, from longer life expectancy (Census Bureau Citation2014) to higher lifetime pay (NCHS Citation2012, 32). Frankly, it is deeply unfair to blame students for responding strategically to an environment that, sometimes from before the start of formal schooling, has taught them to view their own cognitive processes as secondary to an assessable product of little intrinsic value to either student or assessor, and which environment eventually rewards them with a longer, wealthier life. That this environment is financially exploitative and sadly impersonal has long since been naturalised.

So how can process-model academic feminism intervene? If institutional change is constant, the trends that have marked the twentieth and twenty-first centuries resulting from competition for influence over higher education among business, government, institutional faculty, and administration, then perhaps all academic feminists need do is advocate strenuously enough, and attend closely enough to the long processes of change in the academy, that we are able to guide them. Activist movements of the 1960s changed the face and character of the academy and are still doing so, but state political/financial decisions have made an equal difference. Using a process model of research on a macro level, with its emphasis on how present crises are by-products of an ongoing process, it is clear that one response academic feminists need to make to the increase in commercialism on campuses is to advocate for state and federal funding not tied to vague, economistic ideas of ‘performance’ or the correct time-to-degree and instead tied to outcomes that actually push education forward and give students responsible tools for thinking with. We need to work with activists and lobbyists to get our perspective heard and our solutions implemented despite their not being obviously ‘feminist’.

On a personal level, I propose process-model pedagogy as a form of microactivism intensely responsive to the classroom encounter between students, and between students and instructors, and also responsive to the institutional pressures brought to bear on the classroom. Having only taught required courses at my current institution, I have a thorough grasp of the ennui of the student struggling to accede to extrinsic motivators. As I teach at a large institution, my students have few courses in their first two years in which an instructor learns their name, the others being large (100+ students) survey courses, so the learning process in our shared classroom automatically looks and feels different. As a graduate student in literature and composition, I teach classes with fewer than 30 students and enjoy the luxury of a 1–1 schedule, so not only can I learn students’ names, I can show them actual care. Beyond this ethic of care, I think central to any process-model pedagogy, though, I want to share an example of process-model teaching before discussing the metapedagogical aspects of the practice I am advocating.

As a typical teacher of composition, I am tasked with teaching a very specific style of writing. Called Standard Edited American English (SEAE), this style has a history. SEAE emerged from a particular location within American higher education, specifically post-Civil War private colleges and universities ‘comprised almost exclusively of Protestants of northeastern European ancestry’, the vast majority of whom were men, and SEAE still retains its function as a gendered, ethnicised marker of elite status (Wilson Citation2012). While I do expect students to learn SEAE, I also see composition as a craft, and in using a modified workshop model I reflect that conviction in classroom processes such as peer editing and guided revision. This is already process-model teaching, of a sort, but one particular assignment most clearly demonstrates the purpose and effects of process-model teaching: towards the end of the semester, when students are becoming exhausted to breaking point, I ask students to complete an in-class, unedited reflection on their relationship to writing and to SEAE.

The results are always surprising and affecting. Multiple students describe a love for creative writing crushed by SEAE’s rigid expectations or by the feelings of inadequacy and illiteracy generated thereby. Most note the intense effort involved in writing to the ‘standard’. Some, often but by no means exclusively non-native English speakers, write that they spend immense amounts of time on minor writing assignments – up to 10 hours – and find their low grades emotionally devastating. These responses always sadden me, and I am careful to reserve the next class meeting for a processing session; feelings are easily lost in a product-oriented environment. However, the written product this assignment creates is of minor importance because I want students, through the process of writing together in the classroom, to reflect on the process of their own education and to understand that the educative process works on them on multiple levels, that the educative process is actually divided into two parts: what Basil Bernstein calls the ‘regulative’ and the ‘instructional’ discourse. The problem of SEAE demonstrates this perfectly because what Bernstein defines as instructional, ‘the discourse which creates specialized skills and their relationship to each other’, is here so closely blended with what he describes as ‘the moral discourse which creates order, relations and identity’, the regulative discourse (Bernstein Citation1996, 46).

Afterwards, I teach students that the process of learning SEAE has as its instructional discourse two aspects: the mechanics of SEAE style – what is typically called ‘correct’ English, consisting of grammatical rules, traditions of punctuation, citation, and structure – and SEAE conventions of expression and explication. All of this has to do with usage traditions in the academy, as Wilson points out, and I suggest to students that their expression is gendered (masculine), ethnicised (white), and classed (elite) through participation in that tradition. Additionally, this assignment prompts students to critique SEAE’s regulative discourse, which misrecognises the value of dialects other than SEAE, silences students’ voices and complicates their writing. SEAE is a formal institutional dialect, and it has always clothed the institutional operations of monocultural, monolingual power on students; more than that, mastery of SEAE is an indicator – one that has serious effects on student self-perception – of their history, their identity, and their ‘failure’ to master the ruling dialect, and it is used by the institution as such.

That classrooms can easily become spaces that reify the operations of patriarchal institutional power on students is not surprising, but for a feminist teacher this is precisely what motivates a process methodology. By reflecting explicitly on the regulative aspects of the classroom encounter between student and instructor, and on the regulative aspects of the encounter between student and subject, and by inviting the student to bring to consciousness and expression their own subjugation to a regulative discourse that seeks to remake them in the image of the hegemon, it is possible to negotiate a place for some kind of educational jouissance Footnote4 and to critique the institution without abandoning the undeniably important work that goes on there.

It could easily be argued that feminist pedagogy is already doing this, and to some degree this is absolutely true. Berenice Malka Fisher writes of ‘teaching through feminist discourse’ in order to foster a classroom discussion ‘aimed at understanding and resisting women’s oppression’, using this ‘discourse work’ to motivate and carry forward a process of relating sociological inquiry to activism, and she proudly claims its place in a second-wave, consciousness-raising-session genealogy (Citation2001, 3). Dorothy E. Smith grounds her feminist praxis in an epistemology with similar aims: a reinterpreted Marxist materialism that understands ideological categories through actual social relations, arguing that the social sciences have long read from category to phenomenon rather than the reverse, and thus elide the truth that ‘it is the social relations of people’s actual lives, which are only reflected or expressed in the categories, that are, or should be, our objects of our inquiry’ (Citation2011, 5). In Teaching to Transgress (Citation1994) bell hooks certainly describes a process-model pedagogy, one that clearly grows from her own student experiences both good and bad, and in the pages of Radical Teacher, Radical Pedagogy, or The International Journal of Critical Pedagogy one can find numerous descriptions of reflexive teaching practices similar to what I am advocating here.

However, this begs the question of what is specifically feminist about process methodologies. One way to answer this is to point out what seems to me anti-feminist in current feminist pedagogy. During the ‘long march through the institutions’, too many academic feminists seem to have gotten lost there, resulting in the use of top-down, transmissive teaching reliant on what Freire calls ‘banking method’ pedagogy, where students encounter the insights of generations of feminist thinkers in an environment seemingly uninfluenced by their implications. While this is not universally true, it seems that many academic feminists tend to assume that our job happens in the instructive discourse of students learning things, pay little or no attention to the normative regulative discourse most of us are trained to use, and thus forget that our current product-oriented model rests on an epistemology in which students and teachers become things.

To make a more affirmative argument about process-model feminism qua feminism, I would argue that in addition to giving back to students some of the power vested in the institution through product-oriented patriarchal epistemology, process-model feminism participates in a long tradition of feminist thought epitomised by De Beauvoir’s famous quote. Process-model feminism has its roots in the second-wave social constructivist feminism that follows from her insight, and it is certainly possible to understand the work of some queer studies scholars as an extension of Judith Butler’s explicitly process-oriented theory of performativity. Peta Hinton and Iris van der Tuin also create space for a future process-oriented feminism, arguing in a recent special issue on Feminist New Materialism that ‘themes of change and transformation are … clear collaborators in what defines feminist praxis’ (Citation2014, 2). All this suggests that process-model feminism is a practical extension of the widespread feminist repurposing of process philosophy whose multigenerational antecedents in social constructivist, queer, and new materialist theory suggest that process-model feminism has always been an aspect of feminist praxis but has neither been named as such nor sufficiently shaped the way academic feminists perform teaching and research. It is valuable to note here that Hinton and van der Tuin understand feminist New Materialism in much the same way as I understand process-model feminism; just as feminist New Materialism asks us to contemplate the materiality of change – ‘how matter comes to matter’, in Barad’s (Citation2003) apposite phrase – process-model feminism asks us to contemplate the materiality of the past as it is expressed in the ongoing present and, moreover, offers techniques for participating in that expression through institutional research and teaching.

But what of those of us for whom feminist content must be peripheral to the business of our classrooms? I am still expected to teach composition – a specific style with a problematic history. I do so because I believe that familiarising themselves with the institutional dialect as the product of a process that has placed institutional norms ahead of student potentiality, in a world where institutions constrain increasing diversity through forced adherence to a phallologocentric ‘logic of the One’, will give students power to negotiate their own institutional identities and to control some of what happens to them in the institutions that will govern their lives. In inviting students thus to reflect on the ongoing regulative and instructional discourses at work in the classroom, I can engage both the civic-democratic and the careerist sides of current collegiate discourse without allowing either to remain unexamined for their potentially problematic, patriarchal aspects. To accommodate more instructional discussion of regulative discourse as a multilayered problematic is an important first step in process-model pedagogies.

Beyond that I find processual feminist methodologies useful because they are portable. Too much work on feminist pedagogy assumes feminist content, and most ‘practical’ or applied fields of study don’t lend themselves to the theoretical feminism academics typically espouse. This need not be always the case; one could teach biology using Emily Martin’s ‘The Egg and the Sperm’ (Citation1991) among many, many others in the field of feminist science studies, but feminist science studies is, again, often process-oriented. Much of it quite literally takes as subject matter the process of scientific investigation, whether it be Haraway’s (Citation1988) work on situated knowledge and feminist objectivity or M’Charek’s (Citation2005) work on the human genome project. Were I to be faced with the problem of using feminist process-model pedagogy in an engineering class I would be able to teach traditional engineering subject matter in the context of these kinds of questions: what is the composition of the field? Who does engineering? Who is the client, and who will be the workers that build these structures? What are the unspoken aspects of the process engineers engage in, and why are they unspoken? I would expect a discussion of regulative discourses that have made engineering a male-dominated field to ensue, or a discussion of global gender politics, political economics and their effects on workers, all of which could offer students both a sense of the process by which current, contingent systems come to be and an opportunity to reflect on their role within them. Admittedly, these are untested scenarios, but one of the points I wish to make in this essay is precisely that most academics are not currently engaged in feminist process-model pedagogy, and thus the implications of that engagement must remain unclear.

In terms of research, the implications are clearer because, as I note above, a great deal of process-model research has already been performed. Process-model research pays careful attention to the located prehistory of a problematic, so in this specific essay I have discussed how collegiate governance as a dynamic, ongoing process has worked and is working now in fairly specific terms. Having done so, I find that I need not adopt the lugubrious tone of so many students of the corporate university, because I know from process-model research that U.S. institutions of higher learning have never been perfect and are now in some ways less exclusive than they’ve ever been. The continual process of transformation that U.S. higher education exists in has always been marked by tension over control both of individual institutions and of the system as a whole, without lasting equilibrium.

More generally, process-model research results in the repetition of fewer received half-truths and ideological presuppositions, since assumptions and received truths are exactly what process-model researchers take as their area of inquiry. Academic feminists are well placed to do this job and, to some degree, have always done it. The canon wars in English departments and the gradual relinquishing of exclusively male physiological models in medicine are both good examples of the real-world results of performing process-model research and both have had feminist effects; what this article calls for is a more precise codification of these methods and a wider application of them. Questioning the theoretical bases on which commonplaces are built, the processes by which they are maintained, and the ways they reify phallologocentrism is the essence of process-model feminism and increases the applied power of any feminist analysis.

Conclusions

In this essay, I have argued that classroom instructors at ‘corporate’ institutions of higher education find themselves at the fulcrum of what has always been a machine in motion. Institutions of higher learning in the U.S. have a turbulent history marked by cyclic power struggles influenced by other, larger processes, especially economic policy-formation and sociological trends affecting enrollment. We are currently in an enrollment uptick predicted to continue, and specific (women) students are driving it. This in itself is an important though incidental conclusion reached through the research process and indicates that the activism uptick we are also seeing in U.S. colleges and universities (Johnson Citation2014; Wong Citation2015), which largely focuses on sexism, sexual assault, university governance and student rights, along with the enrollment boom and the changing nature of academic employment, are products of a process that could be guided in such a way as to change the character of the university and divert it once again from what seems to be its current practice of treating people like products. We need a return to a belief in the ability of feminist praxis to effect change in the academy, and feminist process-model methods are a useful here.

Additionally, in considering through process-model research, the questions raised by the intersection of feminism and institutional teaching, I have found that we need to be asking whether the feminism in question is located in the teaching or its content, and whether feminism can be ‘produced’ through outcome-oriented teaching or whether feminism ‘happens’ in and through the process of reflexive learning. Indeed, the very meaning of the word ‘feminism’ is clearly in flux, as Hinton and van der Tuin note, and process-model feminism offers a methodology and an onto-epistemology descriptive of, and participatory in, that dynamic process. As institutions of higher education continue to change in response to a myriad of pressures brought to bear by widely divergent interests, and as academic and activist feminisms remain closely tied to institutions unlikely to ever be completely transformed by them, process-model feminism offers a way of marching through those institutions without becoming of them.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1. For more, see Gender and Politics 5(2) and Krook and Mackay Citation2011.

2. The term ‘ontogenesis’ I use here to refer to the development or developmental history of an individual.

3. As Garrison (Citation1994) notes, ‘[C]apturing all of the reticulated connections composing Dewey’s holism is a difficult task’, and I agree with Garrison that understanding Dewey only through his philosophic engagement with pragmatism is likely to lead to misunderstandings. Deweyan pragmatism is best understood as an anti-essentialist instrumentalism or as a form of transactional realism, and assumes that the world and those in it are always in-process. In child development, Deweyan pragmatism stresses the co-creation of meaning in community with others, and assumes the central role of communication in the social construction of subjects but, unlike Vygotsky’s theories, lays stress on postcedent rather than antecedent events.

4. Jouissance is a notoriously difficult concept to use and to explain. Here, I use the term in its Lacanian meaning to indicate that students in product-oriented environments are placed under a regime consisting of such intimate prohibitions that they are unable to experience themselves except through their institutionalized identities, and thus are separated from and unable to know their own, immanent desires which, in aggregate, make up their educational jouissance.

References

- Aronowitz, S., and H. A. Giroux. 2000. “The Corporate University and the Politics of Education.” The Educational Forum 6 (4): 332–339. doi: 10.1080/00131720008984778

- Barad, Karen. 2003. “Posthumanist Performativity: Towards an Understanding of How Matter Comes to Matter.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 28 (3): 801–831. doi: 10.1086/345321

- Bernstein, B. 1996. Pedagogy, Symbolic Control and Identity: Theory, Research, Critique. London: Taylor & Francis.

- Ferrell, R. 2011. “Income Outcome: Life in the Corporate University.” Cultural Studies 17 (2): 165–82. doi:10.5130/csr.v17i2.1719.

- Fisher, B. M. 2001. No Angel in the Classroom: Teaching Through Feminist Discourse. New York: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Garrison, Jim. 1994. “Realism, Deweyan Pragmatism, and Educational Research.” Educational Researcher 23 (1): 5–14. doi: 10.3102/0013189X023001005

- Geiger, R. L. 2005. “The Ten Generations of American Higher Education.” In Higher Education in the 21st Century, edited by P. G. Altbach, P. J. Gumport, and R. O. Berdahl, 38–70. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins UP.

- Geiger, R. L. 2015. The History of American Higher Education: Learning and Culture from the Founding to World War 2. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP.

- Gow, J. 1984. “Preface.” In Knowledge Reconsidered: A Feminist Overview, edited by U. M. Franklin, vii–xi. Ottowa, ON: Canadian Research Institute for the Advancement of Women.

- Haraway, D. 1988. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” Feminist Studies 14 (3): 575–99. doi:10.2307/3178066.

- Hinton, P., and I. van der Tuin. 2014. “Preface.” Women: A Cultural Review 25 (1): 1–8.

- hooks, b. 1994. Teaching to Trangress. New York: Routledge.

- Johnson, A. “American Student Protest Timeline, 2014–15.” studentactivism.net. Accessed December 4, 2014. http://studentactivism.net/2014/12/04/american-student-protest-timeline-2014-15 /.

- Krook, M. L. and F. Mackay, eds. 2011. Gender, Politics, and Institutions: Towards a Feminist Institutionalism. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- M’Charek, A. 2005. The Human Genome Diversity Project: An Ethnography of Scientific Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

- Marcus, G. E. 2002. “Intimate Strangers: The Dynamics of (Non) Relationship Between the Natural and Human Sciences in the Contemporary U.S. University.” Anthropological Quarterly 75 (3): 519–526. doi: 10.1353/anq.2002.0048

- Martin, E. 1991. “The Egg and the Sperm: How Science Has Constructed a Romance Based on Stereotypical Male-Female Roles.” Signs 16 (3): 485–501. doi:10.1086/494680.

- NASBO (National Association of State Budget Officers) 2013. Improving Postsecondary Education Through the Budget Process: Challenges and Opportunities. Washington, DC: NASBO.

- NCHS (National Center for Health Statistics) 2012. Health, United States, 2011: With Special Feature on Socioeconomic Status and Health. Hyattsville, MD: NCHS.

- Schrecker, E. 2012. “Academic Freedom in the Corporate University.” Radical Teacher 93: 38–45. doi:10.5406/radicalteacher.93.0038.

- Smith, D. E. 2011. “Ideology, Science, and Social Relations: A Reinterpretation of Marx’s Epistemology.” In Educating from Marx: Race, Gender, and Learning, edited by Sara Carpenter and Shahrzad Mojab, 19–40. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Subramaniam, M., R. Perrucci, and D. Whitlock. 2014. “Intellectual Closure: A Theoretical Framework Linking Knowledge, Power, and the Corporate University.” Critical Sociology 40 (3): 411–430. doi: 10.1177/0896920512463412

- United States Census Bureau. 2014. “Table A-3: Mean Earnings of Workers 18 Years and Over, by Educational Attainment, Race, Hispanic Origin, and Sex: 1975 to 2013.” http://www.census.gov/hhes/socdemo/education/data/cps/historical/index.html.

- Wilson, N. E. 2012. “Stocking the Bodega: Towards a New Writing Center Paradigm.” Praxis: A Writing Center Journal 10 (1). http://www.praxisuwc.com/wilson-101/.

- Wong, A. “The Renaissance of Student Activism.” The Atlantic, Accessed May 21, 2015. http://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2015/05/the-renaissance-of-student-activism/393749/.