Abstract

The relationship between mental exhaustion and somatic sensations has been described across cultures for millennia, including the contextual relationship with studying and learning. In 19th century Britain, concern regarding the impact of ‘excessive’ study (‘overstudy’) and the mental impact on ‘brainworkers’ led to the coining of the term ‘Brain Fag’ in 1850. Anxiety became heightened following the promulgation of the Education Acts from 1870 with compulsory child education. This was felt to be a public health crisis with social class distinctions. Brain fag anxiety subsequently transmitted across the British colonies while declining in Britain. Over a century later, this linguistic and colonial residue was observed in British West Africa where it was described as a culture bound syndrome.

Introduction

Mental exhaustion is a common complaint in contemporary societies, however it is not a novel human phenomenon. Often, the term is used to express feeling mentally tired with a history of cultural metamorphoses from symptoms and idioms of distress processed through medicalization to specific psychiatric disorders.

Mental fatigue associated with somatic sensations has been reported since the ancient Greek era. The Greek physician, Erasistratus of Ceos writing around 280 BCE about the nature of scientific inquiry, quoted by the physician and philosopher Galen, is reported to have said:

‘Those who are completely unused to inquiry are, in their first attempts, blinded and dazed in their understanding and straightway leave off the inquiry from mental fatigue’. [Galen] (Brunschwig et al., Citation2000, p. 238)

Biblical references to physical and mental sequelae of mental fatigue also caution against relentless study, illustrated with the following verses:

And further, by these, my son, be admonished: of making many books there is no end; and much study is a weariness of the flesh Ecclesiastes 12:12 (KJV) (BibleGateway, Citation2020b)

And as he thus spake for himself, Festus said with a loud voice, Paul, thou art beside thyself; much learning doth make thee mad. Acts 26:24 King James Version (KJV) (BibleGateway, Citation2020a)

The English playwright William Shakespeare, writing in Henry IV in the 1500s, graphically describes somatic symptoms attributed to study and the brain in a scene involving the monarch:

I hear, moreover, his Highness is fall’n into same whoreson apoplexy... This apoplexy, as I take it, is a kind of lethargy; please your lordship, a kind of sleeping in the blood, a tingling... It hath it original from much grief, from study, and perturbation of the brain. I have read the cause of this in Galen; it is a kind of deafness. (Shakespeare, Citation1597)

In the modern era, burnout (Maslach, Citation1976; Freudenberger & Richelson, Citation1980; Heinemann & Heinemann, Citation2017) and exam stress (Zunhammer et al., Citation2013; Ringeisen et al., Citation2019) for instance, are conceptualised as challenges of modern society based on the emotional and cognitive toll of mental activity in professionals and students. It has been theorised that burnout has connotations of sustained effort with exhaustion in cognitive professionals with less reference among manual workers (Schaffner, Citation2016) and the question often arises if this term is a proxy for something else?

Oftentimes, the cluster of mental exhaustion symptoms is classified under the rubrics of depression, anxiety, somatoform and medically unexplained disorders in the prevailing World Health Organisation and American Psychiatric Association classificatory systems including ICD 10 (Segal, Citation2010a); ICD 11 (WHO, Citation2019); ICD 10 (WHO, Citation1992); DSM-IV-TR (APA, Citation2000); and DSM 5 (APA, Citation2013) with additional cultural context in glossaries of culture-bound syndromes and culture-specific disorders.

The concept of culture bound-syndromes (CBS) has evolved with controversy regarding their nosological and diagnostic stability over time (Kirmayer & Sartorius, Citation2007; Ventriglio et al., Citation2016). It has been argued that the Western and ethnocentric nature of earlier diagnostic manuals introduce cultural relativism and bias with questions regarding world views that perpetuate ‘exotic’ syndromes (Ayonrinde & Bhugra, Citation2014). Furthermore, CBS may indicate the cultural bias of clinicians and researchers with overvaluing etic over emic insights. In the DSM 5, the cultural concepts of distress incorporating syndromes, idioms of distress and explanations recognises that all mental distress is culturally framed. Against this backdrop, this paper revisits the historical and nosological validity of the frequently described syndrome of mental fatigue – the ‘Brain Fag Syndrome.’ (Prince, Citation1960)

In the early half of the last century, mental exhaustion among non-western students in West Africa with anxiety, affective and somatic symptoms have been syndromised as a unique cultural phenomenon referred to as the ‘Brain Fag Syndrome’ (Prince, Citation1960; (see appendix) and (APA, Citation2000; APA, Citation2013)). More recently, some writers have generalised the presence of symptoms beyond Nigeria and West Africa to include African students in the diaspora. Numerous descriptions of this syndrome, replicated in scientific publications, books and other reference material, claim the etymology of the term ‘Brain Fag’ (mental fatigue) is rooted in West African English both as an idiom of distress and explanatory model. This has also been widely replicated over the internet and in international educational curricula referencing the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the American Psychiatric Association (Citation2000; Citation2013). However, historical observations suggest precolonial use of the term within and across the Victorian British empire (Ayonrinde, Citation2008; Ayonrinde & Bhugra, Citation2014) In 19th century English, to be ‘fagged’ meant to be tired while ‘fag’ in this context referred to fatigue, prostration, exhaustion or tiredness. This use of the term is no longer in wider common parlance.

In contemporary parlance, the term ‘brain fag’ is rarely if ever used in daily communication or as an idiom of distress in West African populations and for all intents and purposes, it is obsolete. Neither is the term brain fag salient in routine current West African clinical psychiatric practice. Existing reference is primarily and almost exclusively found in academic literature and medical education curricula as a culture-bound syndrome. In fact, only 22% of Nigerian psychiatrists ever consider a diagnosis of brain fag with preferred diagnoses of depression (36%), anxiety disorder (49%), somatisation disorder (30%) (Ayonrinde, Citation2008); herein lies a conflict of emic and etic perspectives.

This historical exploration sheds light on the inception, rise and fall of ‘brain-fag’ in 19th century Britain, transmission across the British Empire in the 20th century and current attribution as a West African syndrome in the 21st century. In this paper, the aim is to determine the etymology of the term or phrase ‘Brain Fag’ while exploring its evolution as a symptom, idiom of distress, syndrome and explanatory concept and to investigate the linguistic anthropology of brain fag through bibliometrics.

The earliest application and contextual use of the term ‘Brain Fag’ was identified from a range of original historical sources through a combination of both manual and electronic exploration of medical, literary, newspaper, advertising and therapeutic primary source archives for the term ‘Brain Fag.’

The History of ‘Brain Fag’

Brain Fag in the 19th Century

In 19th century Britain, concern about the impact of study and education on health started to manifest during the post-industrial revolution with the growth of non-manual vocations and ‘brain workers’ in rapidly expanding urban areas. Brain workers were individuals whose vocations required more mental than manual effort such as lawyers, book-keepers, writers, teachers and students in contrast to the working classes such as coal miners, builders and fowlers. These would be considered similar to white-collar and blue-collar workers.

In 1870, the promulgation of Education Acts (UK Parliament, Citation1870) led to the establishment and significant growth in the number of schools and educational institutions with a clear objective to develop literacy and numeracy across the less privileged British population. This stage of British history may be referred to as the ‘Educational Revolution,’ a process sustained through national growth and expansion of the empire intertwined with missionary church objectives till the 20th century Compulsory education was to become the order of the day for many children erstwhile banished to a life of low literacy, poor houses, labour and orphanages. As a means of social mobility, this inadvertently served to heighten anxiety and concern of the ruling classes of society regarding the potential threat and impact of education on different groups. Furthermore, a structured national learning curriculum was alien with uncertainties regarding the appropriate age, gender, social class, duration and activity level for schools. At this stage of British history, no template for the number of hours, breaks and methods applied to education existed.

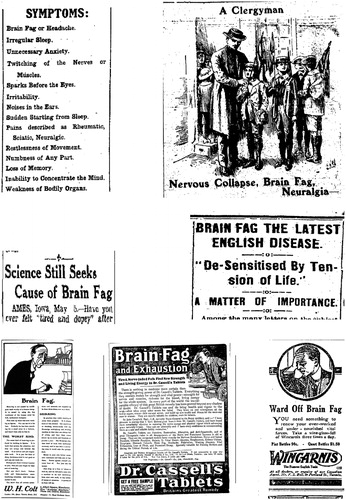

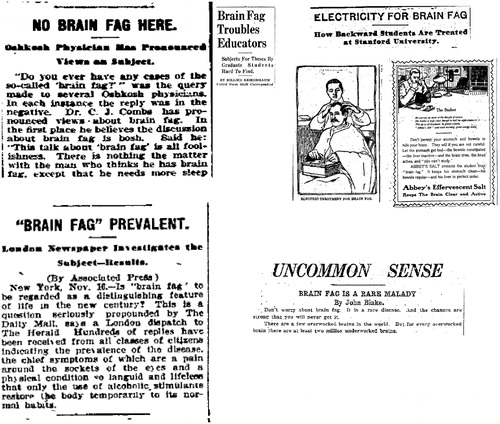

Anxiety regarding the health risks associated with study spread widely through media reports (see and ) while medical science cautioned on nervous diseases, insanity and protracted lethargy from ‘overstudy’ (see ). In fact, mental disorders in schools and colleges believed to be consequential to ‘overstudy’ subsequently became aetiological, psychopathological and pathophysiological grounds for asylum admissions. Additional review of the hospital archives of one of the oldest psychiatric hospitals, the Bethlem Royal Hospital, London, England revealed 15% of male and 4% of female admissions for moral insanity were for Excessive Study or Overwork (1862, Bethlem). These historical archives provided very insightful clinical and cultural context to perceptions of ‘overstudy’ in 19th and 20th century Britain.

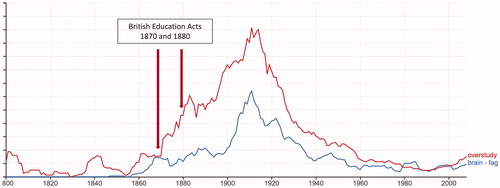

Figure 1. Bibliometric timeline showing the comparative frequency of the terms ‘Overstudy’ and ‘Brain Fag’ in books (1800–2000).

It was in this climate of educational anxiety, industrial and economic growth and competitive job opportunities that the term ‘brain fag’ was coined in Britain as the scourge of ‘brain workers’.

The Etymology of the Term ‘Brain Fag’ – 1850

An exploration of medical bibliography and literature identified that the earliest consistently verifiable primary source use of the term ‘brain fag’ was a book chapter by Tunstall, (Citation1850). James Tunstall, a physician to the Eastern Dispensary of Bath, England and Former Resident Medical Officer of the Bath General Hospital published a series of papers and a book highlighting the healing properties of the Bath Waters. His book, ‘The Bath waters: their uses and effects in the cure and relief of various chronic diseases’, appears to have been widely circulated and cited in British and American medical journals, stirring interest, controversy and commentary in many publications. As is evident from multiple sources (The British and foreign medico-chirurgical review or quarterly journal of medicine, Citation1851 (Br Foreign Med Chir Rev, Citation1851; The Critic, Citation1851); The Journal of psychological medicine and mental pathology, Citation1851, page 300; London Journal of Medicine: a monthly record of the medical sciences, 1852, page 464; publication of the Journal of Psychological Medicine, 1861), the term brain fag coined by Tunstall was widely noted and indeed applauded.

It would be appropriate at this juncture to examine extracts from Tunstall’s original 1850 text, ‘The Bath waters: their uses and effects in the cure and relief of various chronic diseases.’ Chapter IX, page 98 (Tunstall, Citation1850).

BRAIN FAG…‘I have classed together, under the above name, many functional disorders which afflict those who make great use of the pen, and, at the same time, take but little exercise—overworking their mental faculties without sufficient bodily fatigue; the subjects of them being authors, journalists, solicitors, clerks in merchants’ counting-houses, and other persons who are engaged in mental industry, not requiring, but rather preventing, bodily exertion’. (Tunstall, Citation1850), page 98

‘The causes of the disorder are manifestly, in the first place, severe thought and sedentary occupation’ akin to physical fatigue from inadequate exercise. Tunstall elaborates:

Symptoms are ‘severe dyspepsia, loss of appetite, irregularity of the hepatic and renal secretions, with diarrhoea alternating with costiveness, hemorrhoidal tumours with frequent micturition; watchfulness, irritability to the slightest external impression, nervous dreams, palpitation of the heart, with a weak and irregular pulse, and intermittent, ill-defined headache’. These constituting the first stage of the disease. In the second stage ‘lower extremities begin to lose their nervous power, from the pressure applied by the sitting position…. Gradually the feet lose their motive action and the patient describes himself as walking, as it were, upon horsehair; the muscles waste from want of the due exertion; cerebral mischief sets in, and the patient is compelled to abandon all employment: his hands dropping to his side, refuse any longer to write down his thoughts; he, being totally helpless, is compelled to resort to medical advice’. (Tunstall, Citation1850)

The third, or critical stage states:

‘upon his treatment now depends either the total loss of health, or his complete, though gradual, restoration. His symptoms are alarming, his state paralytic, shewing evidence of disease of the cerebro-spinal axis, and for his relief the routine practitioner orders him bleeding and antiphlogistics. He becomes rapidly worse; all his symptoms increase, and still the same system is pursued’. …. ‘Should complete hemiplegia occur, we find it to have taken place a few days subsequently to a venesection’. (Tunstall, Citation1850)

During the ‘railway panic’ (a period between 1825 and 1850 of rapid railway growth, land reclaim and litigation), Tunstall said many persons suffered this disease and found their way to Bath. A description of the classical patient experience was as follows:

‘I had great mental anxiety requiring me to devote several hours a day to studious writing, being then preparing a work, getting up evidence in a case, or to go to Parliament, as the case may be, my meals were irregular; I was up early and late in my study, and suffered much from irregularity of the bowels’. In a short time, headache came on, and I was compelled to apply to my medical attendant, who cupped me on the neck, applied blisters, and ordered me to live sparingly. I became weaker and weaker’. (Tunstall, Citation1850)

Tunstall stressed, ‘the first and most important point is to debar the patient from all mental exertion, and to promote the restoration of digestive functions as well as use of chalybeates’ (a general remedy mineral water in vogue during the 17th–19th century).

Tunstall cautioned that ‘patients in this disease are the ready victims of every quackery: by turns they apply to mesmerisers, homeopathists, and hydropathists’.

With an air of authority and self-promotion, Tunstall recommended ‘a full course of the Bath waters, in conjunction with galvanism’ by a legitimate practitioner adding, ‘The Bath waters are capable of curing the diseased condition of nervous function which I have classified under the name of ‘Brain fag’, with ‘…strict attention to diet, regular hours, change of scene, and by abstinence from all mental labour’.

Over the next decades concern about the burden of study and mental strain on the minds of brainworkers persisted in Britain (Wilde, Citation1861).

On 2nd August 1869, Benjamin Richardson, a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians presented a paper at the Annual Meeting of the Medico-Psychological Association in York titled ‘Physical Disease from Mental Strain’. Richardson categorised six classes of mental (brain) workers distinguished by mental demands and strain associated with their work, namely:

‘the mere copyist, who sits all day at his desk, and transfers copies of writing, or speech, to a piece of paper. The clerk, the compositor, the reporter, and the second and third rate author are of this class’.

‘the thinker and writer, who copies from the great manuscripts’

‘the speculative man, usually very selfish and locked up in himself; who from day to day, and night to night, and hour to hour, schemes; who walks with his head down’.

‘the man who carries on his shoulders other people’s anxieties, who thinks for others and must never be tired by the effort; the professional man is here represented; the politician, the physician and surgeon, the lawyer and accountant’.

‘the artist, who labours towards perfection at some given task, and, absorbed in his work, forgets the world around, and toils on, supported by the applause of many admirers, and deaf to nearly all else’.

Lastly, ‘the learner, the student; the child or youth whose will is hardly his own, who works when he is bidden, and plays when he is permitted; turned out on the world prepared, by education and training’. (Richardson, Citation1870)

Richardson felt that brain fag was most prevalent among professional class of men ‘who suffer most severely and decisively from simple exhaustion of the nervous system, resulting from active overwork’ (Richardson, Citation1870)

Elaborating on clinical presentation Richardson said:

‘symptoms usually commence with irregular action of the heart. He takes cold, suffers from congestion of the lungs or kidneys, and, unable to bear the shock, sinks rapidly under it, his mind becoming intensely irritable, or even losing its balance. He does some foolish thing, trips in his calculation, and is pronounced ‘insane.’ (Richardson, Citation1870)

Further consequence being: ‘diabetes from sudden mental shock’ … ‘in which excretion of sugar and the profuse dieresis sequential to severe mental strain’… ‘constitute a hopeless class, the danger sudden, the course rapid, the fatal end sure’. Richardson deduced that mental exhaustion was linked with lower social classes stating that ‘our uneducated, cloddish populations are the breeders of our abstract insanity, while our educated, ambitious, over-straining, untiring, mental workers are the breeders and intensifiers of some of the worst forms of physical malady’. (Richardson, Citation1870)

With the morbid descriptions above it is no wonder there was escalating panic across the British empire about the scourge of mental exhaustion in brain workers manifesting in brain fag.

In 1879, the concern was reinforced by one of the most influential physicians of the time, D. Hack Tuke who presented a paper to the British Medical Association titled ‘Intemperance in Study’, later published in the Journal of Mental Science (precursor to the British Journal of Psychiatry) (Tuke, Citation1880). Intemperance (excessive indulgence) in study and educational pursuit was opined as a preventable cause of insanity. Tuke asserted that ‘having met from time to time with cases of brain-fag and also actual insanity, arising from excessive mental work’. ‘I regard it as a serious evil………still I fear it is in schools and colleges……….and among students’. (Tuke, Citation1880)

In 1883, the medical opinions of the time also had considerable influence and held great sway in the government and among lawmakers with prominence in the House of Lords debates (Citation1883). Evidence was presented that, ‘The recent increase of lunacy must be principally attributed to intemperance; ……unless the warnings given by some of the highest authorities in the Medical Profession were to be disregarded. Those warnings pointed to overwork at schools as producing serious health and sometimes fatal effects. (House of Lords, Citation1883), citing:

Dr. Crichton Browne, Visitor of Chancery lunatics, said, at the Annual Medical Meeting, in August, 1880—

Of the many conditions tending to the increase of mental disease I would specially direct your attention to education’.….’Injudicious haste or ill-considered zeal may work serious mischief among fragile or badly nourished children, by inducing exhaustion of the brain. It is a curious fact that, since the recent spread of education, the increase of deaths from hydro-cephalous has not been among infants, but among children over five years of age.

While inconsistent with contemporary 21st century knowledge, the gravity of these expert opinions had global influence. Within a decade of the promulgation of the Education Act of 1870, brain-fag was perceived to be a high-risk public health disease of youth and scholars. As overstudy, mental exhaustion and brain fag () became absorbed into the taxonomy of ‘insanity’ and asylums proffered treatments for this sub-type of ‘moral insanity’.

Among medical scholars a number of other descriptive terms were used to describe study-related mental exhaustion, however, they have mostly gone into decline or total extinction [see list below] (Tuke, Citation1892).

Disorders Linked with Overstudy in Brainworkers (19th century) (Tuke, Citation1892)

Cerebropathy

Brain fag

Brain tire

Nervous diathesis

Nervous exhaustion

Ataxia spirituum

Receptive dyaesthesia

Acedia

Encephalopathia literatorum

Alopecia accidentalis

Apoplexia mentalis

Apoplexia sanguinea

Interestingly, as reports of brain fag became more widespread among the British working classes, a distinction started emerging in society. Ultimately, the working-class illness attributed to overstudy was ‘brain fag’ while the ruling and upper social class were diagnosed with neurasthenia. ( and ) This distinction was also evident within physician expertise; brain fag being treated by ‘alienists’ or ‘mad doctors’ in asylums while neurasthenia was attended to by psychotherapists and neurologists in nervous disease hospitals (Taylor, Citation2001).

Figure 2. British and American Newspaper Articles referring to ‘Brain Fag’ vs ‘Neurasthenia’ [1870–2005].

![Figure 2. British and American Newspaper Articles referring to ‘Brain Fag’ vs ‘Neurasthenia’ [1870–2005].](/cms/asset/ad967a0b-8b91-4a13-8d1f-7044bf211dbb/iirp_a_1775428_f0002_c.jpg)

The social class distinction between brain fag and neurasthenia was reinforced by several influential proponents of the time (Wessely, Citation1994; Lian & Bondevik, Citation2015). The American Neurologist George Beard to whom the term ‘neurasthenia’ has been attributed (Beard, Citation1869) asserted that neurasthenia occurred ‘in the civilised, refined and educated, rather than the barbarous and low born and untrained’ (Beard, Citation1881) while in Boston, Edes indicated it was ‘more likely to affect teachers, students and nurses than domestic servants or factory hands’ (Edes, Citation1895). Reinforcing the widely held view, the Canadian physician Pritchard described neurasthenia as a ‘disease of bright intellects; its victims are leaders and masters of men, each one a Captain of industry’ (Pritchard, Citation1905); and in France, it was reported that there was ‘excessive rarity among labouring classes, and its almost exclusive limitation to the cultivated classes’ (Ballet, Citation1908).

In many medical and lay text as well as in the media, the terms Brain Fag and Neuraesthenia were sometimes used interchangeably ().

In 1898, a journalistic contradiction to the social class hypothesis would be some of the news print coverage of the ‘nervous breakdown’ of the British Prime Minister – Lord Salisbury, widely covered over the world that he had suffered from ‘brain fag’ – left depressed, fatigued and unable to write and attend to details culminating in him retiring to the South of France for a break.

Overstudy and Brain Fag in Lexicons

The history and evolution of words and phrases can also be explored through current and old dictionaries, lexicons and bibliography ( and ) By investigating early edition English language dictionaries for the term ‘brain-fag’ and cross-referencing secondary etymological sources such as the Oxford English Dictionary 1989 (OED Online, Citation2020), the earliest etymological source in the Oxford English Dictionary credited the term brain-fag to the 8th Edition of the Dunglison Medical Dictionary and Lexicon in Citation1851 (OED Online, Citation2020). The author, Robley Dunglison, an English born physician was a prolific lexicon writer and reviewer who migrated from England to America in 1832 and later became the personal physician to Thomas Jefferson. The Oxford English Dictionary has since reattributed the etymology to Tunstall (Citation1850) (OED Online, Citation2020). The image in shows an extract from the Dunglison Medical Dictionary and Lexicon (Citation1851) with reference to brain-fag.

Figure 3. Bibliometric timeline showing the comparative frequency of the terms ‘Brain Fag’ and ‘Brain Fag Syndrome’ in books (1800–2000).

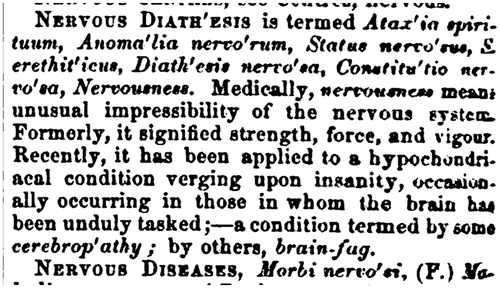

Nervous Diath’esis, ‘Recently, it has been applied to a hypochondriacal condition verging upon insanity, occasionally occurring in those in whom the brain has been unduly tasked; a condition termed by some cerebrop’athy; by others, brain-fag’ (Dunglison, Citation1851, p. 596; OED Online, Citation2020) – see

A review of earlier editions (second edition of 1839 to the preceding 1846) did not find any reference to ‘brain-fag’. Retention of ‘brain-fag’ in seven consecutive editions from 1851, would suggest acceptance in the parlance of the day. Unfortunately, Dunglison did not credit his sources for this definition, and just cited ‘others’.

Further examination of other dictionaries and lexicons found variants of this definition initially in medical dictionaries then subsequently in general volumes, such as:

Brain Fag in the Early 20th Century

With expansion and consolidation of British colonies, so did cultural practices including the use of language. For instance, luxury cruises and migration to South Africa were offered as a panacea to mental exhaustion and fatigue for persons ‘suffering from brain fag’ (Noble, Citation1896). In 1907 brain fag was also mentioned in South African parliamentary debates (Watson, Citation1907).

The concept of brain fag remained embedded in British society and transitioned into the early 20th century with more observations and scientific papers expressing concern about the mental toll of education and brain work. Writing in 1926, Gillespie said:

‘The fatigue syndrome to which the name ‘neurasthenia ‘has been characteristically applied included the following symptoms and physical signs: ‘brain-fag ‘with sensations of pressure in the head; poor memory, lack of concentration, irritability of temper, increased reflexes, poor sleep, anorexia and various aches and pains’. (R. D. Gillespie, Citation1926)

Shortly after, the same author (Gillespie, Citation1933) published clinical observations from Guy’s Hospital, London on the psychoneuroses and brain fag. Describing functional nervous conditions, Gillespie stated, ‘curable disorders include many cases in the purely symptomatic categories’ such as ‘Nervous exhaustion, in which, in addition to feeling exhausted, the patient often complains of brain-fag, poor memory, excessive fatigue, irritability, or insomnia’. Elucidating this with a vignette, he wrote:

‘This was a man of middle-age who complained of ‘brain-fag’ which took the form of inability to read for more than about 40 minutes at a time. He then had to rest for half an hour before he could resume. This had handicapped him considerably in his work for examinations…’………. ‘It had first appeared when the patient was about 13…when it was remarked this was the result of overstrain of his ‘under-developed brain.’ (Gillespie, Citation1933)

These descriptions of brain fag not only positioned the syndrome as having dysphoric, anxiety and somatic components but also as a shared idiom of distress between the patient and clinician in the society of the time. Unlike some of the 19th century reports, cautioning paralysis, epilepsy, strokes and death associated with excessive study, early 20th century descriptions of brain fag symptoms were less catastrophic, morbid or fatal in their prognostication.

Descriptions of Brain Fag in 19th Century Literature and the Arts

While brain-fag had its etymological genesis in the British medical and scientific community, it permeated Victorian British society and further afield across the British Empire. A rich insight into cultural themes can be gained from the literary arts (Montgomery, Citation1915; A Modern Opium Eater, Citation1914; The Critic, Citation1851) press, media stories and personal communication of the period.

Evidence of ‘brain fag’ in the socio-cultural life and parlance of the British empire and colonies can be found in numerous literary writings describing pressures of mental activity and exhaustion through study and the consequences on individuals. The 1886 correspondence between the famous author, Robert Louis Stevenson and his father (Thomas) refers to an experience of brain fag in what might be described as ‘writer’s block’ today. An extract of the letter quoted below:

‘SKERRYVORE, BOURNEMOUTH, JANUARY 25, 1886.

MY DEAR FATHER, - …… To-day I rest, being a little run down. Strange how liable we are to brain fag in this scooty family! But as far as I have got, all but the last chapter, ….a far better story and far sounder at heart than TREASURE ISLAND.

I have no earthly news, living entirely in my story, and only coming out of it to play patience. Your most affectionate son,

ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON’. (Colvin, Citation1899)

In Australia, the link between study and brain fag was presented in the novel The Missing Link, Chapter XIII, the Widow and the Link

‘Nickie wore a good suit, he bore quite a reputable hat, his linen was fairly meritorious like a man accustomed to luxuries… In his varied career Nickie had had ups and downs…. he passed quite easily for a dramatic artist taking rest and change to dissipate brain fag, the result of too studious application to his art’. (Dyson, Citation1908)

In Nigeria, the revered Scottish missionary, Mary Slessor, frequently used the term ‘brain fag’ in correspondence and communication with the indigenous community (Slessor, Citation1910, Citation1913).

22nd December 1910 Ikpe Ikot Nkon

My Dear Old Chief

………Why don’t you go on? It is perhaps that sickening hatred of the pen that keeps you from doing it? Or is it too much to do? & your brain is fagged? It is a pity any how that you don’t go in more for literary work, for you have the power to do it. ……….

Yours affectionately

Mary M Slessor (Slessor, Citation1910);

Ikpe Ikot Nkon 16th Oct 1913

My Dear Old Boss

…….You will be going into the winter, and I do not envy you that experience, but I hope it will be a good time for you and that you may get a good stock of health and strength, of every kind, and a rest from strain and brain fag. …….Thank you for the newspaper cutting. (Slessor, Citation1913).

These correspondences also provide tangible, plausible and logical explanation for how the term ‘brain fag’ was introduced to Nigeria by British missionaries by at least 1910, 50 years before description of the contemporary ‘syndrome’.

In 1913, America, Jack London writing in John Barleycorn provides a vivid description of the mental effects of excessive application to study.

‘Nineteen hours a day I studied. For three months I kept this pace, only breaking it on several occasions. My body grew weary, my mind grew weary, but I stayed with it. My eyes grew weary and began to twitch, but they did not break down. Perhaps, toward the last, I got a bit dotty.’ …. ‘Came the several days of the examinations, during which time I scarcely closed my eyes in sleep, devoting every moment to cramming and reviewing. And when I turned in my last examination paper I was in full possession of a splendid case of brain-fag. I didn’t want to see a book. I didn’t want to think or to lay eyes on anybody who was liable to think’.

‘There was but one prescription for such a condition…… out of the profound of my brain- fag, I knew what I wanted. I wanted to drink. I wanted to get drunk…… my over-worked and jaded mind wanted to forget’. (London, Citation1913)

This rich description of the prolonged mental activity in academic pursuit with mental fatigue, physical fatigue, somatic head and visual sensations, captures the experience of mental pressures and exhaustion from study as well as self-medication with the use of alcohol as an antidote.

A 1917 magazine article titled ‘Brain-fag in school children’ by Mary Bayley and Dr Menas Gregory, Chief Alienist and Director, Psychopathic and Allied Wards, Bellevue Hospital, New York describes a consultation between a mother and her thirteen-year old son with a doctor in the following dialogue:

‘Of what does he complain?’ said the doctor. ‘He does not complain at all’ replied the mother. ‘Very studious, is he not?’ …. ‘Oh, yes! ….John is always at his books’. The doctor said ‘You must take him out of school for a time; there are unmistakable signs of a fagged and overworked brain’. (Bayley, Citation1917)

The article claims that fifty-nine out of 116 children reported prostration from overwork.

Symptoms of brain-fag were described as, ‘a restless wandering of the eyes, compression of the lips, protruding of the tongue with each new effort, extreme irritability, indigestions, general tired feeling, stumbling over words when speaking, substituting one word for another, or extreme forgetfulness’. More pronounced symptoms such as, ‘involuntary twitchings of the hands, face or eyes, frowns or grimaces unconsciously made, asymmetry of posture and unequal movements of the two sides of the body’, were also listed. The article recommended ‘freedom from excitement, plenty of nutritious food, much exercise in open air and abundance of sleep’ for the ‘young brain-worker’. (Bayley, Citation1917)

India – 1921 (Mahatma Gandhi)

In India, the political activist and revered leader Mahatma Gandhi challenged the colonisation and ‘de-indianizating’ of education in India, emphatically stating:

‘The foreign medium has caused brain-fag, put an undue strain upon the nerves of our children, made them crammers and imitators, unfitted them for original work and thought, and disabled them for filtrating their learning to the family or the masses’. (Gandhi, Young India, 1-9-1921)

Brain Fag in Newspapers and Print News Media

Newspaper reports provide a rich historical resource, perspective and insight into specific periods of time with daily accounts of issues of public interest, in essence capturing, documenting and archiving each society and the period, albeit with possible editorial bias.

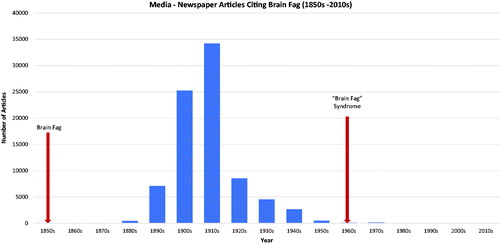

An electronic newspaper database search (NewspaperArchives.com, 2020) found 83,479 article references to the term ‘brain-fag’ in British, Australian, New Zealand, Canadian, Jamaican and North American press with 99.7% of the articles before 1960, the year the Brain Fag Syndrome in Nigeria paper was published. The earliest published news article was found in 1870, twenty years after coining of the term by Tunstall (Citation1850) and nearly a century before Prince (Citation1960) ( and ).

A preliminary content analysis of the references to brain fag found mention in news articles, advertisements, health, education and law reports. An analysis of the frequency of use of the term ‘brain-fag’ and alternative spelling ‘brainfag’ in these newspapers is charted below ( and ):

While the first media citation identified was in 1870s following education legislation in Britain, use of the term remained sporadic till 1895 and then peaked between 1900 and 1910. A rapid decline in the use of the term in the 1920s may correspond with the Great War (World War I) and the Spanish flu pandemic at the time both characterised by a significant reduction in knowledge industry as nations ramped up industrial output for war and fighting disease. A more detailed newspaper analysis under review is beyond the scope of this paper, however the images in () illustrate the concerns associated with brain-fag at the time.

Figure 6. (Continued)

Brain Fag as a Culture Bound Syndrome in Britain

‘Brain-Fag’ in Victorian Britain, would have met the broadly used contemporary criteria for culture bound syndromes and subsequent cultural concepts of distress (APA, Citation2013). Firstly, it was characterised by clusters of affective, anxiety and somatic symptoms emanating within British culture. Secondly, it served as a distinct idiom of distress recognised by lay persons and clinicians, and finally explanations were clearly defined with attributions to ‘overstudy’. Furthermore, an interesting and important historical footnote is that inhabitants of Australia, Canada, USA, India, Jamaica and Nigeria (all nations linked to the British Empire) referred to Brain Fag as an ‘English’ or ‘British Disease’ of the 19th century.

Current Status of ‘Brain Fag Syndrome’

In the DSM IV and IV-TR, Brain fag was defined as - ‘A term initially used in West Africa to refer to a condition experienced by high school or university students in response to the challenges to schooling’ and subsequently in the revised DSM 5 that ‘thinking too much’ may also be a key component of cultural syndromes such as ‘brain fag’ in Nigeria, primarily attributed to excessive study. However, a thought provoking systematic review found that idioms of distress associated with ‘thinking too much’ are ‘common worldwide and show consistencies in phenomenology, aetiology, and effective coping strategies’. Authors emphasised that it would be reductionist to distil the idiom to any one psychiatric construct and ‘in fact, they appear to overlap with phenomena across multiple psychiatric categories, as well as reflecting aspects of experience not reducible to psychiatric symptoms or disorders’. (Kaiser et al., Citation2015)

However, contemporary literature and research on Brain fag symptoms and the Brain Fag Syndrome overall ignore the all too significant preceding British history. The current taxonomy and nosological status remain controversial with declining salience among both African physicians (Ayonrinde et al., Citation2015) as well as within the DSM 5. Research reports from not only West Africa (Fatoye & Morakinyo, Citation2003; Morakinyo, Citation1980; Ola, Morakinyo, & Adewuya, Citation2009) but also disparate North, South and East African cultures with distinct cultural, geopolitical, linguistic and historical identities further emphasise the absence of ‘culture-boundedness’ as Africa is not a homogenous continent. (Harris, Citation1981; Guinness, Citation1992a, Citation1992b ; Durst et al., Citation1993; Peltzer et al., Citation1998).

It could be debated whether the description of Brain Fag Syndrome in Nigeria by a non-indigenous psychiatrist was emically or etically derived or not. Reinforcing these tensions, indigenous psychiatrists have either supported or challenged the validity and relevance of this ‘culture-bound syndrome’ (Ayonrinde & Bhugra, Citation2014; Jegede, Citation1983; Morakinyo, Citation1980; Ola et al., Citation2009; Aina & Morakinyo, Citation2011). Idiomatic reference to heat in the head (Mbanefo, Citation1966; Ayonrinde, Citation1977; Ebigbo, Citation1986) and crawling sensations, may be the singular cultural feature to this polydiagnostic ‘syndrome’. Regardless of the point of view, a common area of agreement among most researchers is that considerably more research is required to understand the phenomenon; such rigorous research remains lacking to date. With such heterogeneity and absence of pathognomonic symptoms and signs, diagnostic stability is not guaranteed and Prince, Citation1985) has since revisited that Brain Fag may actually be a ‘cluster of different illnesses’, ‘stereotyped’ and ‘widespread in Africa’ (Prince, Citation1985).

Conclusions

Physical and mental consequences of mental exhaustion have been described for millennia. Contrary to widely held and published belief in diagnostic manuals, psychiatric, social science and educational text, the term ‘Brain Fag’ and associated syndromes of anxiety, affective and somatoform symptoms in student and ‘brain worker’ populations were first described in 19th century Britain (Tunstall, Citation1850) with dissemination across the British Empire. The subsequent syndromization of similar symptoms in 20th century West Africa (Prince, Citation1960) and the re-attribution of the etymology of ‘brain-fag’ in DSM IV and DSM 5 lacks historical merit and highlights the need for rigorous review and contextualization of so-called ‘culture-specific’ expressions of distress in current literature.

In the absence of the same standards of evidence (replicability, reliability, validity, specificity and sensitivity) as well as international research into ‘brain fag’ symptoms in non-indigenous, non-migrant, and culturally diverse groups, contemporary relevance cannot be ascertained. Further research is needed into the uniqueness and pathognomonic relevance of mental exhaustion complaints in African students.

With nearly identical descriptors and criteria for ‘neuraesthenia’, it is also interesting that the brain fag nosology and taxonomy had been the more attractive in literature regarding Africans. The vagueness and ambiguity of brain fag nosology is inconsistent with contemporary emphasis on objectivity and functionality required in classificatory systems.

The linguistic history and anthropology of brain fag spanning three centuries across social class, continents, race and ethnicity is also an interesting discourse in the construction and perpetuation of knowledge and cultural misattribution over time. The time has come for the decolonization of brain fag and its African syndromization in the true spirit of ethical scientific rigour in the 21st century.

Acknowledgement

The author of this paper would like to acknowledge Dr. Akolawole Ayonrinde for the important contextual, historical and anthropological insights.

References

- A Modern Opium Eater (1914). http://www.druglibrary.org/schaffer/history/e1910/modernopiumeater.htm

- Aina, O. F., & Morakinyo, O. (2011). Culture-bound syndromes and the neglect of cultural factors in psychopathologies among Africans. African Journal of Psychiatry, 14(4), 278–285. https://doi.org/10.4314/ajpsy.v14i4.4

- APA. (2000) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Text Revised (DSM-IV-TR). American Psychiatric Association.

- APA. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association.

- Ayonrinde, A. (1977). Heat in the head: A semantic confusion. African Journal of Psychiatry, 1(2), 59–63.

- Ayonrinde, O. A. (2008). Editorial: Brain Fag Syndrome: New Wine in Old Bottles or Old Wine in New Bottles? Nigerian Journal of Psychiatry, 6(2), 47–50. https://doi.org/10.4314/njpsyc.v6i2.39875

- Ayonrinde, O., & Bhugra, D. (2014). Culture-bound syndromes. In D. Bhugra (Ed.), Troublesome disguises. (2nd ed., pp. 231–251). Wiley Blackwell.

- Ayonrinde, O. A., Obuaya, C., & Adeyemi, S. O. (2015). Brain fag syndrome: A culture-bound syndrome that may be approaching extinction. BJPsych Bulletin, 39(4), 156–161. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.bp.114.049049

- Ballet, G. (1908). Neurasthenia. Henry Klimpton.

- Bayley, M. E. (1917, September). Brain-Fag in school children. The Woman’s Magazine, Newspaper, pp. 17–24.

- Beard, G. M. (1881). American nervousness, its causes and consequences: a supplement to nervous exhaustion (neurasthenia). https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=3moPAAAAYAAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR1&dq=6.%09Beard,+G.M.+(1881)+American+Nervousness:+Its+Causes+and+Consequences.+New+York:+Putnam’s+Sons.+&ots=91LCEluJ-S&sig=ebg_RAe3NOTeyGlmmYsUL-AyirI

- Beard, G. (1869). Neurasthenia, or Nervous Exhaustion. The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, 80(13), 217–221. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM186904290801301

- BibleGateway (2020a). Acts 26:24 KJV – And as he thus spake for himself. https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Acts+26%3A24&version=KJV

- BibleGateway. (2020b). Ecclesiastes 12:12 KJV – And further, by these, my son, be. https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Ecclesiastes+12%3A12&version=KJV

- Br Foreign Med Chir Rev. (1851). Br Foreign Med Chir Rev Volume 7(13). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/issues/281964/

- Brunschwig, J., Lloyd, G. E. R., Geoffrey, E. R., & Pellegrin, P. (2000). Greek thought: A guide to classical knowledge. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Colvin, S. (1899). The letters of Robert Louis Stevenson to his family and friends/selected and edited, with notes and introduction, by Sidney Colvin. [complete in 2 volumes] by Stevenson, Robert Louis (1850–1894): (1899) 1st Edition in this form. MW Books Ltd. https://www.abebooks.com/servlet/BookDetailsPL?bi=11255706178&searchurl=n%253D200000102%2526xpod%253Don%2526ds%253D30%2526bx%253Don%2526pics%253Don%2526sortby%253D17%2526kn%253Drobert%252Blouis%252Bstevenson%252Bnot%252B%252528%252522print%252Bon%252Bdemand%252522%252Bor%252B%252522printed%252Bon%252Bdemand%25

- Dunglison, R. (1851). Medical lexicon: A dictionary of medical science (8th ed.). Blanchard & Lea.

- Durst, R., Minuchin-Itzigsohn, S., & Jabotinsky-Rubin, K. (1993). Brain-fag’ syndrome: Manifestation of transculturation in an Ethiopian Jewish immigrant. The Israel Journal of Psychiatry and Related Sciences, 30(4), 223–232.

- Dyson, E. (1908). The Missing Link – Edward Dyson. https://books.google.ca/books?id=RLP39tg05esC&pg=PT118&lpg=PT118&dq=The+Missing+Link,+Chapter+XIII,+the+Widow+and+the+Link&source=bl&ots=pPnDTial1e&sig=ACfU3U2OFN_qICQ-OUtovNHHM_2tO8SfXg&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwimov30lcnpAhXQT98KHRCwD20Q6AEwAXoECAoQAQ#v=one

- Ebigbo, P. O. (1986). A cross sectional study of somatic complaints of Nigerian females using the Enugu Somatization Scale. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 10(2), 167–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00156582

- Edes, R. (1895). The new england invalid. The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, 133(3), 53–57. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM189507181330301

- Fatoye, F. O., & Morakinyo, O. (2003). Study difficulty and the ‘brain fag’ syndrome in Southwestern Nigeria. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 13, 70–80. https://journals.co.za/content/joap/13/1/AJA14330237_114

- Freudenberger, H. J., & Richelson, G. (1980). Burn-out: The high cost of high achievement. Anchor Press.

- Gillespie, R. (1933). Psychotherapy in general practice. The Lancet, 221(5706), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(00)84460-8

- Gillespie, R. D. (1926). Fatigue a clinical study. The Journal of Neurology and Psychopathology, 7, 26.

- Guinness, E. (1992a). Profile and prevalence of the brain fag syndrome: Psychiatric morbidity in school populations in Africa. British Journal of Psychiatry, 160(S16), 42–52. https://doi.org/10.1192/S0007125000296785

- Guinness, E. (1992b). Social origins of the brain fag syndrome. British Journal of Psychiatry, 160(S16), 53–64. https://doi.org/10.1192/S0007125000296797

- Harris, B. (1981). A case of brain fag in East Africa. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 139(2), 162–163. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.139.2.162

- Heinemann, L. V., & Heinemann, T. (2017). Burnout research. SAGE Open, 7(1), 215824401769715. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244017697154

- House of Lords. (1883). Debates (Hansard, 16 July 1883). https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/lords/1883/jul/16/question-observations

- Jegede, R. O. (1983). Psychiatric illness in African students: “brain fag” syndrome revisited*. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie, 28(3), 188–192. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674378302800306

- Kaiser, B. N., Haroz, E. E., Kohrt, B. A., Bolton, P. A., Bass, J. K., & Hinton, D. E. (2015). ‘Thinking too much’: A systematic review of a common idiom of distress. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 147, 170–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.10.044

- Kirmayer, L. J., & Sartorius, N. (2007). Cultural models and somatic syndromes. Psychosomatic Medicine 69, 832–840. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e31815b002c

- Lian, O. S., & Bondevik, H. (2015). Medical constructions of long-term exhaustion, past and present. Sociology of Health & Illness, 37(6), 920–935. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12249

- London, J. (1913). John Barleycorn. https://www.questia.com/library/120096731/john-barleycorn

- Maslach, C. (1976). Burn-out. Human Behaviour, 9, 16–22.

- Mbanefo, S. E. (1966). Heat in the body’ as a psychiatric symptom: Its clinical appraisal and prognostic indication. The Journal of the College of General Practitioners, 11(4), 235–240.

- Montgomery, L. M. (1915). Anne of the Island. https://books.google.ca/books/about/Anne_of_the_Island.html?id=uoVjDwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=kp_read_button&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Morakinyo, O. (1980). A psychophysiological theory of a psychiatric illness (The brain fag syndrome) associated with study among Africans. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 168(2), 84–89. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-198002000-00004

- Noble, J. (1896). Illustrated official handbook of the Cape and South Africa: A résumé of the – Cape of Good Hope (South Africa). In J. Noble (Ed.), 1896 – Cape of Good Hope (South Africa). J.C. Juta & Co. https://books.google.ca/books?id=TTYbAAAAYAAJ&dq=cape+of+good+hope+brain-fag+africa&source=gbs_navlinks_s

- OED Online. (2020). Oxford English Dictionary Volume II.

- Ola, B. A., Morakinyo, O., & Adewuya, A. O. (2009). Brain fag syndrome – A myth or a reality. African Journal of Psychiatry, 12(2), 135–143. https://doi.org/10.4314/ajpsy.v12i2.43731

- Peltzer, K., Cherian, V. I., & Cherian, L. (1998). Brain fag symptoms in rural South African secondary school pupils. Psychological Reports, 83(3 Pt 2), 1187–1196. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1998.83.3f.1187

- Prince, R. (1960). The ‘brain fag’ syndrome in Nigerian students. The Journal of Mental Science, 106(443), 559–570. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.106.443.559

- Prince, R. (1985). The concept of culture-bound syndromes: Anorexia Nervosa and brain-fag. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 21(2), 197–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(85)90089-9

- Pritchard, W. B. (1905). The American disease: An interpretation. Canadian Journal of Medical Surgery, 18, 10–22.

- Richardson, B. W. (1870). Physical disease from mental strain. American Journal of Psychiatry, 26(4), 449–469. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.26.4.449

- Ringeisen, T., Lichtenfeld, S., Becker, S., & Minkley, N. (2019). Stress experience and performance during an oral exam: The role of self-efficacy, threat appraisals, anxiety, and cortisol. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 32(1), 50–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2018.1528528

- Schaffner, A. K. (2016). Exhaustion: A history. Columbia University Press. ISBN-13: 978-0231172301.

- Segal, D. L. (2010a). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-IV-TR). In The Corsini encyclopedia of psychology and behavioral science (4th ed., pp. 495–497). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Segal, D. L. (2010b). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-IV-TR). In The Corsini encyclopedia of psychology (pp. 1–3). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Shakespeare, W. (1597). Henry IV, Part 2, The Folger SHAKESPEARE. https://www.bl.uk/treasures/shakespeare/henry4p2.html

- Slessor, M. (1910). Mary Slessor: Letters 71–80. http://www.leisureandculturedundee.com/library/localhistory/mary-slessor/letters/71-80

- Slessor, M. (1913). Mary Slessor: Letters 81–84, Leisure and Culture Dundee. http://www.leisureandculturedundee.com/library/localhistory/mary-slessor/letters/81-84

- Taylor, R. E. (2001). Death of neurasthenia and its psychological reincarnation: A study of neurasthenia at the national hospital for the relief and cure of the paralysed and epileptic, Queen Square, London, 1870–1932. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 179, 550–557. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.179.6.550

- The Critic. (1851). The Critic: London Literary Journal. The Critic: A Record of Literature, Art, Music, Science, and the Drama …, X. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/njp.32101065266817

- Tuke, D. (1880). Intemperance in Study. Journal of Mental Science, 25(112), 495–504. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.25.112.495

- Tuke, D. (1892). No Title. A Dictionary of Psychological Medicine. J. & A. Churchill.

- Tunstall. (1850). The Bath waters: Their uses and effects in the cure and relief of chronic. https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=RRoDAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA98&dq=brain-fag&lr=&as_drrb_is=b&as_minm_is=0&as_miny_is=1800&as_maxm_is=0&as_maxy_is=1900&num=100&as_brr=3&hl=en#v=onepage&q=brain-fag&f=false

- UK Parliament. (1870). The 1870 Education Act – UK Parliament. https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/livinglearning/school/overview/1870educationact/

- Ventriglio, A., Ayonrinde, O., & Bhugra, D. (2016). Relevance of culture-bound syndromes in the 21st century. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 70(1), 3–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/pcn.12359

- Watson, W. (1907). Debates of the Legislative Assembly of the Colony of Natal. https://books.google.ca/books?id=TAZKAQAAMAAJ&focus=searchwithinvolume&q=fag

- Wessely, S. (1994). Neurasthenia and chronic fatigue: Theory and practice in Britain and America. Transcultural Psychiatric Research Review, 31(2), 173–209. https://doi.org/10.1177/136346159403100206

- WHO (1992). International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision (ICD-10). World Health Organization.

- WHO. (2019). International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision (ICD-11). World Health Organization.

- Wilde, F. G. S. (1877). Brain-fag from mental worry and overwork: Its pathology, symptoms, and combined treatment by homoepathy and hydropathy. E. Gould & Son.

- Zunhammer, M., Eberle, H., Eichhammer, P., & Busch, V. (2013). Somatic symptoms evoked by exam stress in university students: The role of alexithymia, neuroticism, anxiety and depression. PLoS One, 8(12), e84911. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0084911

Appendix

‘Brain-Fag’ Syndrome in Nigerian Students (From original text, Prince, Citation1960)

Distinctive symptoms of syndrome are:

intellectual impairment

sensory impairment (chiefly visual)

somatic complaints most commonly of pain or burning in the head and neck

Other complaints affecting the ability to study

an unhappy, tense facial expression

a characteristic gesture of passing the hand over the surface of the scalp or rubbing the vertex of the skull

Presentation

‘Often the symptoms commenced during periods of intensive reading and study prior to examinations or sometimes just following periods of intensive study.

Patients generally attribute their illness to fatigue of the brain due to excessive ‘brain work’.

It is for this reason that the designation ‘Brain Fag’ syndrome has been used.

Culture-Boundedness

The expression seems to be used by Nigerians generally to describe any psychiatric disturbance occurring in ‘brain workers’.

‘The syndrome is related to ‘westernization’, for prior to the 19th century when significant European influence commenced, the written word and the student life were unknown to the inhabitants of Southern Nigeria.

The syndrome is rarely seen in the European.

Appears that the illness is related in some way to the fusion of European learning techniques with Nigerian personality.’