Abstract

The aim of this study was to compare financial and human resources for mental health services in selected Scandinavian and Eurasian countries. A cross-sectional descriptive and analytical approach was adopted to analyse questionnaire data provided by members of the Ukraine-Norway-Armenia Partnership Project. We compared Scandinavia (Sweden and Norway) and Eurasia (Armenia, Georgia, Kyrgyzstan and Ukraine). Health expenditure in Eurasia was generally below 4% of gross domestic product, with the exception of Georgia (10.2%), compared with 11% in Scandinavia. Inpatient hospital care commonly exceeded 50% of the mental health budget. The central governments in Eurasia paid for over 50% of the health expenditure, compared to 2% in Scandinavia. The number of mental health personnel per head of population was much smaller in Eurasia than Scandinavia. Financial and human resources were limited in Eurasia and mainly concentrated on institutional services. Health activities were largely managed by central governments. Community-based mental healthcare was poorly implemented, compared to Scandinavia, especially for children and adolescents.

Introduction

Mental Health disorders are recognized among the top 10 leading causes of disease burden worldwide (GDB 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators, Citation2022). About 14.6% of the years lived with disability (YLDs) were attributed to mental health disorders (GDB 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators, Citation2022). A report published by the World Health Organization (WHO) pointed out the wide gap between the global need for treatment for mental health disorders and its provision (WHO, Citation2011). In particular, it stated that up to 85% of people with severe mental health disorders did not receive any treatment if they live in low-and-middle-income countries (LMICs). Global economic losses generated by poor mental health were approximately 2.5 trillion US Dollars (USD) in 2010 and are expected to rise to 6 trillion USD by the year 2030 (The Lancet Global Health, Citation2020).

The global prevalence of mental health disorders among children and adolescents has been reported to be as high as up to 20% (Kessler et al., Citation2007). One-third of them start to experience any mental health disorders by 14 years of age, with a peak age of onset at 14.5 years (Solmi et al., Citation2022). The consequences of not addressing the mental health and psychosocial development of children and adolescents extends into adulthood. These can result in harmful public health problems, such as drug abuse, becoming parents at an early age, and other psychological, physical and social issues (Beecham, Citation2014).

Mental health services are the key institutions to delivering effective interventions for mental health disorders. In recent years, there is a rapidly increasing need for transitioning care and support from psychiatric hospitals to community settings. Many advocates and researchers believe the latter will reduce overall mental health expenditures and destigmatize mental healthcare (Almeida et al., Citation2015; Perera, Citation2020). In addition, there has been a continuing expansion of integrating mental health services, especially those for children and adolescents, to primary or community-based care (Eapen & Jairam, Citation2009). Early interventions are good approaches for disease prevention and sustainable approach to help improve cost-efficiency in a long run (McCrone et al., Citation2010). Given the prevailing burden and impact of mental health disorders among children and adolescents, investing in early interventions in child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) is needed for sustainable population health (Ritblatt et al., Citation2017). However, many mental health services lack the financial and human resources they need to develop and maintain services, especially in LMICs (WHO, Citation2021b). The WHO’s Mental Health Atlas 2017 showed that, the median global mental health expenditure per person was just 2.5 USD (WHO, Citation2018). The Atlas showed that mental health personnel only accounted for 9 per 100,000 population, including psychiatrists, child psychiatrists, other medical doctors, nurses, psychologists, social workers, occupational therapists and other paid professionals working in mental health. There were considerable variations among countries with different income levels. For example, the WHO European Region spent 20 times more on mental health expenditure per person than the African Region and 50 times more on mental health personnel (WHO, Citation2018).

When we speak about LMICs, we often forget about, or do not consider, Eurasian countries. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), defines Eurasia as 13 LMICs that extend from the borders of the European Union to the Far East. There are Afghanistan, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, the Republic of Moldova, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine and Uzbekistan (OECD and Eurasia, Citation2020). This paper focuses on Armenia, Georgia, Kyrgyzstan and Ukraine, for reasons that are explained later. Despite differences in culture, religion and history, health systems in Eurasia share many features due to the ideological influences in the former Soviet Union. Mental health initiatives have tended to focus on pharmaceutical interventions that were provided in psychiatric hospitals that were more like asylums (Aliev et al., Citation2021). In recent years, Eurasian countries have made respectable efforts to institute reforms that have resulted in affordable and efficient community mental healthcare (Wong et al., Citation2021). For example, Armenia launched Psychiatric Services Strategic Plan in 2012 (McCarthy et al., Citation2013), and Georgia produced the Strategic Health Plan for Mental Healthcare for 2014–2020 (Government of Georgia, Citation2014; Wong et al., Citation2021). Kyrgyzstan now has the Program for the Protection of Mental Health of the Population for 2018-2030 (Aliev et al., Citation2021; Government of the Kyrgyz Republic, Citation2018), and Ukraine developed The Concept of National Mental Health Action Plan in 2017 (Ministry of Health of Ukraine, Citation2018; Skokauskas et al., Citation2020). At the time of writing the Ukrainian plan was not yet approved by the Government. Reallocating psychiatric hospital beds from large institutions in Georgia to newly opened psychiatric departments within general hospitals in 2011 was seen as one of the most significant reforms of the country’s mental health system (Makhashvili & van Voren, Citation2013; Sulaberidze et al., Citation2018).

Today, various problems continued to challenge Eurasia’s mental healthcare. Health expenditure is among the lowest worldwide and has mainly focussed on institutional systems (Krupchanka & Winkler, Citation2016; McCarthy et al., Citation2013; Winkler et al., Citation2017). In 2018, the out-of-pocket costs incurred by the general population accounted for more than 40% of the health expenditure of the four countries we studied: Armenia (84.28%), Georgia (47.67%), Kyrgyzstan (52.44%) and Ukraine (49.35%) (WHO, Citation2021a). Community services have remained poorly implemented throughout Eurasia, due to a general lack of funds and clear plans (Winkler et al., Citation2017) and there is a chronic shortage of human resources. Although psychiatrists increased in Eurasia between 2007 and 2013, the WHO’s European Health Information Gateway statistics showed that the numbers were still well below the European average of 13.99 per 100,000 in Armenia (4.73 per 100,000), Georgia (8.76 per 100,000), Kyrgyzstan (3.41 per 100,000) and Ukraine (8.69 per 100,000). In addition, studies on many branches of psychiatry-related social science have been lacking in Eurasia, including social psychiatry, psychiatric epidemiology and research on services and mental health economics (Winkler et al., Citation2017).

The Ukraine-Norway-Armenia (UNA) Partnership Project was developed between 2016 and 2019 to address existing challenges in Eurasia and mental healthcare provision. The Project is a collaborative initiative between universities in Armenia, Georgia, Kyrgyzstan, Norway, Sweden, Ukraine and the WHO, Division of Non-communicable Diseases and Promoting Health through the Life-course in Europe. The founding members were as follows: the Norwegian University of Science and Technology and the Yerevan State Medical University in Armenia, along with the Ukrainian Donetsk National Medical, The Ukrainian Research Institute of Social and Forensic Psychiatry and Drug Abuse and the Ukrainian Catholic University. More universities from Ukraine, Georgia and Kyrgyzstan then joined the partnership. The Project focuses primarily on mental health capacity building in universities throughout Eurasia and empowers local clinicians, educators and scientists to take part in mental health research. Several educational and research initiatives have taken place, including one that focussed on mental health services and health economics.

Mental healthcare in Norway and Sweden also used to be linked to large inpatient institutions for long-term treatment, like Eurasia. Four decades of development have resulted in significant movements towards community-based care and further decentralization of financial and human resources. CAMHS is a part of outpatient care in both Sweden and Norway (Richter Sundberg et al., Citation2021; Ruud & Friis, Citation2021). Today, Norway and Sweden are two of the OECD countries that spend the most on healthcare per head of population. In 2020, Norway spent 11.3% of its gross domestic product (GDP) on health and the figure was 11.4% in Sweden (OECD Stat., Citation2021). By 2018, Norway had 25 psychiatrists per 100,000 people, and Sweden had 23 per 100,000 (Eurostat, Citation2021). Furthermore, both countries share many similarities in planning health systems, including tax-based funding, publicly owned and operated hospitals and comprehensive healthcare coverage (Magnussen et al., Citation2009; Pedersen, Citation2019). In 2018, more than 85% of the health expenditure in Norway and Sweden was covered by public resources (WHO, Citation2021a). Patients contribute to the costs of visits, tests and drug prescriptions, but there are with caps on out-of-pocket costs for most services in both countries.

Resource planning policies that seem to work well in Scandinavia may be applicable to Eurasia. However, Scandinavian models would need to be adjusted, and adapted, for Eurasian countries, due to heterogeneity in geography, demography, history, policy, economy, culture and good practice. The aim of this study was to compare the current state of financial and human resource allocations for mental health services in two Scandinavian and four Eurasian countries. We then used this to examine future directions and possible priorities for advancing mental health resource allocations for Eurasia.

Methods

The comparison was carried out by analysing data collected by the UNA Partnership Project’s mental health economics initiatives. For this study, Eurasia refers to Armenia, Georgia, Kyrgyzstan and Ukraine, which adhere to our four collaborators from the UNA Partnership Project, and Scandinavia refers to Sweden and Norway. Given Sweden being geographically and demographically larger than Norway and both countries being very similar in mental health systems and provision of services, Sweden was considered as representative of Scandinavia and used as a comparator for Eurasia in the present study.

The survey tool was an original questionnaire that was designed by the Project (Appendix S1). The consisted of 18 questions that were written in English. They were structured to depict the most important aspects of resource allocation and social welfare status of mental health services in Eurasia during the 2019 fiscal year. These questions covered topics from healthcare financing to remuneration and other staff entitlements. Data from Sweden were provided in the original questionnaire to represent Scandinavia and to reference some predominantly western definitions, such as high-cost protection, that may have conflicted with Eurasian contexts. In this context, high-cost protection means a cap on out-of-pocket expenses. In the present paper, we aim to compare the current status of mental health service provision and financing in Scandinavia and Eurasian countries. A few quantitative indicators and variables were hence selected from the questionnaire as they answered our research question. The variables we analysed and present in the paper include healthcare and healthcare financing, the mean cost of mental health services, facilities and staffing allocations by healthcare setting and average income by mental health specialties.

We invited one representative (from each of the four Eurasian countries, namely, Armenia, Georgia, Kyrgyzstan and Ukraine) to take part as they are affiliated with the UNA Partnership Project. These were all psychiatrists who played leading roles in their country’s national psychiatric associations, such as president or vice-president. The participants who were invited to take part received the questionnaire in October 2019 and delivered their responses in January 2020. They were all advised to discuss their answers with other members of their national association. The data were drawn from each country’s public administration departments, programs and published documents. These included, the Ministry of Health and National Institute of Health in Armenia and the Ministry of Health in Ukraine. The data from Kyrgyzstan came from the Mandatory Health Insurance Fund under the Government of the Kyrgyz Republic and the Republican Centre for Mental Health. Georgia used the largest number of data sources, namely, the National Statistics Office, the National Centre for Disease Control and Public Health, the Ministry of Internally Displaced Persons from the Occupied Territories, Labour, Health and Social Affairs and the State Health Care Program.

We conducted standardized interviews with each participant, purely to clarify any responses to the questionnaire (Appendix S2). All participants signed a consent form before these interviews, which were performed via Zoom over three weeks in the spring 2021.

Results

At the time of the data collection, Georgia spent more on healthcare than any other Eurasian country, and this amount, which was equivalent to 10.2% of their GDP, compared well with Sweden, who spent 11% (). Armenia spent the least, at barely 1.6% of its GDP share, and Ukraine and Kyrgyzstan both spent less than 4%.

Table 1. General healthcare and mental healthcare financing.

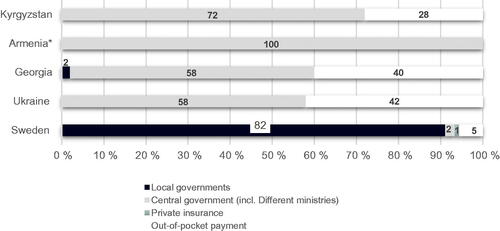

Central governments were the largest purchasers of healthcare activities throughout Eurasia, and they accounted for more than 50% of the health expenditure (). In contrast, healthcare activities in Sweden were predominantly financed by local government organizations. Private insurance played a minor role in the Swedish healthcare system, but the proportion was unknown in Eurasia. Out-of-pocket costs for members of public also accounted for a small proportion of Sweden’s healthcare system. These primarily related to medication and dental care, and some were reimbursed and capped. However, these remained high in Eurasia ().

Figure 1. Revenue sources for health systems. *To date, Armenia lacks information about out-of-pocket costs.

Armenia spent the most on mental healthcare in Eurasia, excluding expenditure on medication, and this accounted for 3.3% of its total healthcare expenditure. This was slightly lower than the 4% recorded in Sweden (). While Sweden allocated 15% of its mental health budget to child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS), Georgia allocated 8.1% and the figure was 2.9% for Kyrgyzstan. Ukraine and Armenia were unable to provide specific figures as they did not have separate budgets for CAMHS.

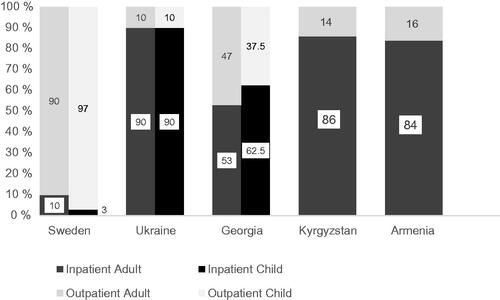

Sweden spent most of its budget for adult mental healthcare services (AMHS) and CAMHS on outpatient services. In contrast, Eurasia went in the opposite direction and spent the majority on inpatient care (). Ukraine was highest with 90%, followed by Kyrgyzstan with 86% and Armenia with 84%. The one exception was Georgia, which spent nearly half of its health expenditure (47%) on outpatient services. At the time of the study, Eurasia’s outpatient mental health community services primarily focussed on adult services. Mobile community adult mental health services were already available in Georgia and had been newly implemented in Ukraine by the WHO pilot project. Outpatient community services throughout Eurasia were financed by state programs (Georgia), municipalities (Armenia and Georgia) or international grants (Armenia, Georgia, Kyrgyzstan and Ukraine).

In general, the healthcare costs of inpatient treatment in Eurasia were linked to the severity of the patients’ mental status, the psychologists’ qualifications, and how long services were provided for. The state budgets usually covered a hospital stay of three to four weeks (). Although the length of hospital stays was not restricted, lengthy hospitalization was not encouraged unless the patient had a very acute condition.

Table 2. Mean cost of mental health services in Eurasia in USD.

Eurasia had more family doctors working in primary care settings, especially in Kyrgyzstan and Ukraine, but fewer medical beds and mental health personnel than Sweden (). Mental health personnel were generally paid less than the national average for the general population in Armenia (365.94 USD), Georgia (377.20 USD), Kyrgyzstan (218.08 USD) and Ukraine (381.13 USD) ( and ).

Table 3. Facilities and staffing allocations by healthcare setting per 1000 population.

Table 4. Average income by specialty for professionals working in AMHS in Eurasia in USD.

Table 5. Average income by specialty for professional working in CAMHS in Eurasia in USD.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this was the first study to compare financial and human resource allocations of mental health services in Scandinavia and Eurasia. The study revealed that financial resources for general healthcare and mental healthcare was very limited in Eurasia and was mainly directed towards inpatient institutional services. Resources for specialized, community-based care were considerably modest and poorly implemented, especially for young people. Healthcare activities were mainly managed at national levels. In contrast to Eurasia, Scandinavia provided generous financial support for general and mental healthcare, and these were mainly targeted at children and adolescents. Healthcare activities were primarily delivered by local governments and municipalities, through highly specialized community services. In addition, Eurasia faced an overall shortage of mental health personnel, compared to Scandinavia, and they were paid less than their countries’ national averages. The monthly income for psychiatrists was typically 29–49% lower than the national averages, psychologists were 35–70% lower, and nurses were 40–65% lower ( and ). There were no notable income variations between AMHS and CAMHS specialties.

Public spending on healthcare varied substantially between Eurasian countries. The amount spent per head of population ranged from approximately 479 USD in Georgia, down to 45 USD in Kyrgyzstan (). Such difference may suggest variations in implementing universal health coverage. The WHO European Health Report recognized the success of Georgia’s program (WHO, Citation2020). This may be partly explained by the fact that its health budget share, as a percentage of GDP, was similar to Sweden. Although Georgia’s publicly financed health expenditure is still low by European standards, this much-needed investment covered just under half of the services provided to the whole Georgian population (Ketevan et al., Citation2021). This is particularly important for those who previously lacked coverage (Ketevan et al., Citation2021).

In Eurasia, high out-of-pocket costs for the general public are a challenge for health systems. When these costs become the dominating resource, mental health services are likely to be accessed according to the ability to a person’s ability to pay rather than the actual needs of the general population (Dixon et al., Citation2006). However, tracking the longer term implications of out-of-pocket costs in different countries can be challenging, as there are limitations to monitoring meaningful changes (Lu et al., Citation2009). Discussions about out-of-pocket costs can also be a sensitive topic for both patients and physicians, even though this dialogue is crucial (Alexander et al., Citation2003).

As well as high out-of-pocket costs, Eurasia also had a general shortage of state healthcare budgets, especially for outpatient community services. Therefore, external donors, such as international governments, organizations and non-governmental organizations, have helped to fund the development of outpatient interventions and care. In Georgia and Ukraine, for example, international funds are being used to pilot new community services, staff training and supervision and service monitoring. This enabled Ukraine to set up pilot mobile mental health teams in 2015. Meanwhile, Kyrgyzstan was able to set up 12 outpatient community services and these were exclusively run by non-governmental organizations. However, external support is not usually sustainable, and initiatives may only be able to function until funding ends. Outpatient community services are starting to be established in Eurasia, and a sustainable financing mechanism needs to be put in place to soften the transition between outpatient and inpatient hospital care (Skokauskas et al., Citation2020).

CAMHS is still not a priority in Eurasia. In Ukraine and Armenia, CAMHS and AMHS come from the same funding pot and Armenia has no funding for outpatient CAMHS. This may be because CAMHS is a relatively new feature of mental health services in Eurasia. Even in high-income countries, like Australia, CAMHS is partly provided by primary care paediatricians, because the challenges of recruiting specialized mental health workforce and poorly distributed private child psychologists and psychiatrists across the country (Oostermeijer et al., Citation2021).

Health systems are most efficient when they combine centralization and decentralization (Abimbola et al., Citation2019; Atkinson et al., Citation2005; Bazzoli et al., Citation2000; Bossert et al., Citation2007; De Nicola et al., Citation2014; Gross & Rosen, Citation1996). Scandinavia is a good example of this practice. The central government makes funds available, but delegates responsibilities for how they are spent to local governments and municipalities. In contrast, these responsibilities are typically operated at national levels in Eurasia, and this could increase the likelihood of inflexible budget allocations at regional and municipal levels. This means that Eurasian countries may not be able to meet local’s healthcare needs. Having a greater emphasis on regional funding may drive local efficiency and improve healthcare outcomes (James et al., Citation2019), especially in large countries, like Ukraine.

The number of psychiatric beds and primary care family doctors in Eurasia, compared to Scandinavia, may suggest that Eurasia is trying to promote outpatient community care. However, it is not possible to get the full picture by just looking at the data in . Take family doctors as an example. Historically, there has been no specific training for specialists working in general primary care practice in Eurasia (Kühlbrandt, Citation2014). Physicians and paediatricians without relevant advanced medical education have worked as family doctors (Kühlbrandt, Citation2014). Although endeavours to strengthen primary care have been made in recent years, primary care facilities are staffed by a mixture of family doctors and those with some specialist expertise. In Ukraine, for instance, more than 5000 clinics and rural hospitals with poor infrastructures have been renamed as general practice centres (Kolesnyk & Švab, Citation2013). Similarly, some old-styled institutions or therapies in other Eurasian countries are now referred to as primary care general practice.

In 2011, Scheffler et al. (Scheffler & WHO, Citation2011) estimated the workforce shortage for mental healthcare in 58 LMICs in six WHO regions. The European Region, including Eurasia, had the lowest deficit per head of population of all the WHO regions, with workforce shortages of 7.2 per 100,000 people. However, Eurasia still had much fewer mental health personnel than Scandinavia and this could partly have been associated with low remuneration. Although salaries increase by length of experience and seniority, they are frequently well below the national average. In comparison, a Swedish psychiatric nurse and psychologist earned an average of 4575.75 USD and 4859.52 USD per month in 2019, surpassing the intermediate level of 3724.05 USD in Sweden (Statistics Sweden, Citation2020). Financial benefits that do not reward the time invested could lead to brain drains. In addition, low remuneration may, to some extent, reflect that Eurasia lacks general financial support for the decentralization of health resources.

Strengths and limitations

This study helps to fill the gap in research on Eurasia’s mental health service provision, by estimating resource allocations. The comparison with Scandinavia has powerfully identified weaknesses in services provided and suggested what implications this shortfall could have. The study presents exact quantitative information on many features of mental health services. These include the proportion of health budgets that are dedicated to mental healthcare, how they are allocated, the number of mental health staff employed and their social and salary status. Informal collaborations between respondents and colleagues, as in this study, can also boost the reliability of reports.

Certain limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings of this study. First, there was little known about the quality of the data obtained, even though most of it was public information. Second, the data collection could have been exposed to information bias. Some of the reports may have been less subjective than others, as some respondents may have spent more time researching the information published in their native language. Finally, the study may have been subject to recall bias, due to the self-reporting method that was used.

Conclusion and future implication

Eurasian healthcare lacks financial and human resources in general and mental healthcare in particular. The central governments of the four Eurasian countries we studied dominated the bulk of the health resources, in contrast to Scandinavia. In Eurasia, mental healthcare was predominantly based on inpatient hospital care and outpatient community services remained under-resourced, especially for children and adolescents. Responsibility for mental health provision should be decentralized and strengthened by regular consultation. Community services should be better targeted, especially for CAMHS. Workforces need to be trained so that they can provide mental healthcare at a primary care level. Steps need to be taken to boost the status and pay of professional working in mental healthcare.

Consent form

Informed consent was obtained from all the study participants. This project was granted exemption from ethics approval by the Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics in Central Norway (reference no 179018), in line with national legislation.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (1.3 MB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abimbola, S., Baatiema, L., & Bigdeli, M. (2019). The impacts of decentralization on health system equity, efficiency and resilience: A realist synthesis of the evidence. Health Policy and Planning, 34(8), 605–617. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czz055

- Alexander, G. C., Casalino, L. P., & Meltzer, D. O. (2003). Patient-physician communication about out-of-pocket costs. JAMA, 290(7), 953–958. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.290.7.953

- Aliev, A.-A., Roberts, T., Magzumova, S., Panteleeva, L., Yeshimbetova, S., Krupchanka, D., Sartorius, N., Thornicroft, G., & Winkler, P. (2021). Widespread collapse, glimpses of revival: A scoping review of mental health policy and service development in Central Asia. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 56(8), 1329–1340. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-021-02064-2

- Almeida, J. C. d., Mateus, P., Xavier, M., & Tomé, G. (2015). Joint action on mental health and well-being–Towards community-based and socially inclusive mental health care. Análise da Situação em Portugal. https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/mental_health/docs/2017_towardsmhcare_en.pdf

- Atkinson, S., Cohn, A., Ducci, M. E., & Gideon, J. (2005). Implementation of promotion and prevention activities in decentralized health systems: Comparative case studies from Chile and Brazil. Health Promotion International, 20(2), 167–175. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dah605

- Bazzoli, G. J., Chan, B., Shortell, S. M., & D'Aunno, T. (2000). The financial performance of hospitals belonging to health networks and systems. Inquiry, 37, 234–252.

- Beecham, J. (2014). Annual research review: Child and adolescent mental health interventions: A review of progress in economic studies across different disorders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 55(6), 714–732. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12216

- Bossert, T. J., Bowser, D. M., & Amenyah, J. K. (2007). Is decentralization good for logistics systems? Evidence on essential medicine logistics in Ghana and Guatemala. Health Policy and Planning, 22(2), 73–82. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czl041

- De Nicola, A., Gitto, S., Mancuso, P., & Valdmanis, V. (2014). Healthcare reform in Italy: An analysis of efficiency based on nonparametric methods. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management, 29(1), e48–e63. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.2183

- Dixon, A., McDaid, D., Knapp, M., & Curran, C. (2006). Financing mental health services in low-and middle-income countries. Health Policy and Planning, 21(3), 171–182. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czl004

- Eapen, V., & Jairam, R. (2009). Integration of child mental health services to primary care: Challenges and opportunities. Mental Health in Family Medicine, 6(1), 43–48. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22477887 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2777591/

- Eurostat. (2021). Physicians by medical speciality. hlth_rs_spec

- GDB 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators. (2022). Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet Psychiatry, 9(2), 137–150. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00395-3

- Government of Georgia. (2014). On approval of the 2014-2020 state concept of healthcare system of Georgia for 'universal health care and quality control for the protection of patients' rights. https://matsne.gov.ge/en/document/view/2657250?publication=0

- Government of the Kyrgyz Republic. (2018). Programma Pravitel’stva Kyrgyzskoy Respubliki po okhrane psikhicheskogo zdorov’ya naseleniya Kyrgyzskoy Respubliki na 2018–2030 gody [The programme of the government of the Kyrgyz Republic on the protection of the population’s mental health for the 2018–2030]. http://cbd.minjust.gov.kg/act/view/ru-ru/11840

- Gross, R., & Rosen, B. (1996). Decentralization in a sick fund: lessons from an evaluation. Journal of Management in Medicine, 10(1), 67–80. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/02689239610113531

- Perera, I. M. (2020). The relationship between hospital and community psychiatry: Complements, not substitutes? Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 71(9), 964–966. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201900086

- James, C., Beazley, I., Penn, C., Philips, L., & Dougherty, S. (2019). Decentralisation in the health sector and responsibilities across levels of government: Impact on spending decisions and the budget. OECD Journal on Budgeting, 19(3), 4. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1787/c2c2058c-en

- Kessler, R. C., Angermeyer, M., Anthony, J. C., DE Graaf, R., Demyttenaere, K., Gasquet, I., DE Girolamo, G., Gluzman, S., Gureje, O., Haro, J. M., Kawakami, N., Karam, A., Levinson, D., Medina Mora, M. E., Oakley Browne, M. A., Posada-Villa, J., Stein, D. J., Adley Tsang, C. H., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., … Ustün, T. B. (2007). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the World Health Organization's World Mental Health Survey Initiative. World Psychiatry : official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 6(3), 168–176.

- Ketevan, G., Mamuka, N., & Triin, H. (2021). Can people afford to pay for health care? New evidence on financial protection in Georgia. WHO Regional Office for Europe.

- Kolesnyk, P., & Švab, I. (2013). Development of family medicine in Ukraine. European Journal of General Practice, 19(4), 261–265. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/13814788.2013.807791

- Krupchanka, D., & Winkler, P. (2016). State of mental healthcare systems in Eastern Europe: Do we really understand what is going on? BJPsych International, 13(4), 96–99. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1192/s2056474000001446

- Kühlbrandt, C. (2014). Primary health care. Trends in health systems in the former Soviet countries. The European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies.

- Lu, C., Chin, B., Li, G., & Murray, C. J. (2009). Limitations of methods for measuring out-of-pocket and catastrophic private health expenditures. SciELO Public Health.

- Magnussen, J., Vrangbaek, K., & Saltman, R. (2009). Nordic health care systems: Recent reforms and current policy challenges: Recent reforms and current policy challenges. McGraw-Hill Education.

- Makhashvili, N., & van Voren, R. (2013). Balancing community and hospital care: A case study of reforming mental health services in Georgia. PLoS Medicine, 10(1), e1001366. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001366

- McCarthy, J., Harutyunyan, H., Smbatyan, M., & Cressley, H. (2013). Armenia: Influences and organization of mental health services. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 35(2), 100–109. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-012-9170-8

- McCrone, P., Craig, T. K. J., Power, P., & Garety, P. A. (2010). Cost-effectiveness of an early intervention service for people with psychosis. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 196(5), 377–382. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.109.065896

- Ministry of Health of Ukraine. (2018). Ministry of Health National mental health action plan (in Ukrainian). https://moz.gov.ua/article/news/moz-zaklikae-doluchitis-do-obgovorennja-nacionalnogo-planu-zahodiv-z-rozvitku-ohoroni-psihichnogo-zdorovja

- OECD and Eurasia. (2020). https://www.oecd.org/eurasia/

- OECD Stat. (2021). Health expenditure and financing. https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=SHA

- Oostermeijer, S., Bassilios, B., Nicholas, A., Williamson, M., Machlin, A., Harris, M., Burgess, P., & Pirkis, J. (2021). Implementing child and youth mental health services: Early lessons from the Australian Primary Health Network Lead Site Project. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 15(1), 16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-021-00440-8

- Pedersen, K. M. (2019). The Nordic health care systems: Most similar comparative research? Nordic Journal of Health Economics, 6(2), 99–107. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5617/njhe.6707

- Richter Sundberg, L., Christianson, M., Wiklund, M., Hurtig, A.-K., & Goicolea, I. (2021). How can we strengthen mental health services in Swedish youth clinics? A health policy and systems study protocol. BMJ Open, 11(10), e048922. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-048922

- Ritblatt, S. N., Hokoda, A., & Van Liew, C. (2017). Investing in the early childhood mental health workforce development: Enhancing professionals' competencies to support emotion and behavior regulation in young children. Brain Sciences, 7(12), 120. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci7090120

- Ruud, T., & Friis, S. (2021). Community-based mental health services in Norway. Consortium Psychiatricum, 2(1), 47–54. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17816/CP43

- Scheffler, R. M, & WHO. (2011). Human resources for mental health: Workforce shortages in low-and middle-income countries. World Health Organization.

- Skokauskas, N., Chonia, E., van Voren, R., Delespaul, P., Germanavicius, A., Keukens, R., Pinchuk, I., Schulze, M., Koutsenok, I., Herrman, H., Javed, A., Sartorius, N., & Thornicroft, G. (2020). Ukrainian mental health services and World Psychiatric Association Expert Committee recommendations. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 7(9), 738–740. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30344-8

- Solmi, M., Radua, J., Olivola, M., Croce, E., Soardo, L., Salazar de Pablo, G., Il Shin, J., Kirkbride, J. B., Jones, P., Kim, J. H., Kim, J. Y., Carvalho, A. F., Seeman, M. V., Correll, C. U., & Fusar-Poli, P. (2022). Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Molecular Psychiatry, 27(1), 281–295. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-021-01161-7

- Statistics Sweden. (2020). Average monthly salary by county, 2019. https://www.scb.se/en/finding-statistics/statistics-by-subject-area/labour-market/wages-salaries-and-labour-costs/wage-and-salary-structures-and-employment-in-the-primary-municipalities/pong/tables-and-graphs/average-monthly-salary-by-county/

- Sulaberidze, L., Green, S., Chikovani, I., Uchaneishvili, M., & Gotsadze, G. (2018). Barriers to delivering mental health services in Georgia with an economic and financial focus: informing policy and acting on evidence. BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-2912-5

- The Lancet Global Health. (2020). Mental health matters. Lancet Glob Health, 8(11), e1352. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/s2214-109x(20)30432-0

- World Health Organization. (2011). Global burden of mental disorders and the need for a comprehensive, coordinated response from health and social sectors at the country level. Report by the Secretariat.

- World Health Organization. (2018). Mental health atlas 2017.

- World Health Organization. (2020). Health and well-being in the voluntary national reviews of the 2030 agenda for sustainable development in the European region 2016–2020 (CC BY-NCSA 3.0 IGO). https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/340007/WHO-EURO-2020-2121-41876-57440-eng.pdf

- World Health Organization. (2021a). Global health observatory data repository. https://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main

- World Health Organization. (2021b). Improving health systems and services for mental health: mental health policy and service guidance package. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44219

- Winkler, P., Krupchanka, D., Roberts, T., Kondratova, L., Machů, V., Höschl, C., Sartorius, N., Van Voren, R., Aizberg, O., Bitter, I., Cerga-Pashoja, A., Deljkovic, A., Fanaj, N., Germanavicius, A., Hinkov, H., Hovsepyan, A., Ismayilov, F. N., Ivezic, S. S., Jarema, M., … Thornicroft, G. (2017). A blind spot on the global mental health map: A scoping review of 25 years' development of mental health care for people with severe mental illnesses in central and eastern Europe. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 4(8), 634–642. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30135-9

- Wong, B. H.-C., Chkonia, E., Panteleeva, L., Pinchuk, I., Stevanovic, D., Tufan, A. E., … Ougrin, D. (2022). Transitioning to community-based mental healthcare: Reform experiences of five countries. BJPsych International, 19(1), 1–3.