?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

As a social justice issue, it is suggested that racialised identity may represent a critical moderator in the association between racism and adverse mental health. We performed a meta-moderation analysis of studies on racialised identity, racism and adverse mental health in children and adolescents. We searched Pubmed, Web of Science, SocINDEX, PsychInfo, Medline, CINAHL and EBSCO Academic Search Ultimate for peer-reviewed articles published between January 2013 and December 2022. Nine studies, encompassing 2146 Black, Moroccan, Turkish, Indigenous, South Korean, Latinx and Multi-heritage children and adolescents between the ages of 7 and 16, were included, covering depressive symptoms, substance use, internalising symptoms and externalising symptoms. A random effect meta-analysis reported a medium size positive correlation of 0.26 (95% CI = 0.20–0.32) between racism and adverse mental health. A comparison between internalising and externalising symptoms revealed a smaller positive correlation of 0.25 (95% CI = 0.09–0.41) for internalising symptoms and a slightly larger positive correlation of 0.30 (95% CI = 0.19–0.41) for externalising symptoms. A small negative moderation of −0.07 (95% CI = −0.17 to 0.02) was found for racialised identity in the association between racism and internalising symptoms, whilst no moderation was found between racism and externalising symptoms. Overall, a negligible moderation of −0.02 (95% CI = −0.08–0.05) was found for racialised identity in the association of racism to adverse mental health. These findings suggest that the effect of racism on internalising symptoms is slightly stronger for children and adolescents with lower racialised identities and slightly weaker for those with higher racialised identities.

Introduction

It is generally recognised that racism and poor mental health are persistently linked (Bhugra et al., Citation2020; Lazaridou et al., Citation2022). Research on the multiple ways that racialised migrants and refugees experience high levels of stress exposure and low financial resources explored how dysfunctional coping could be a strong mediating factor between disadvantaged social status and mental health (Bianca et al., Citation2022; Mehran et al., Citation2022; Saleh et al., Citation2022). Neurobiological pathways implicated in how lifetime exposure to racism impacts mental health, in the literature on Indigenous mental health as well as the mental health of Black people and further racialised groups, are chronic activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA-axis), the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), and the prefrontal cortex (PFC) (Henssler et al., Citation2020; Ketheesan et al., Citation2020). Chronic stress exposure interacts with individual and group vulnerabilities as discussed in the stress vulnerability model (Zubin & Spring, Citation1977), and may impact brain functions and even structure (Geronimus, Citation1992; Geronimus et al., Citation1996; McEwen & Seeman, Citation1999); thus increasing susceptibility to negative mental health outcomes (Ketheesan et al., Citation2020).

A recent meta-analysis found that the stress and trauma of racism is associated with emotional dysregulation in childhood and adolescence (Roach et al., Citation2022). A developmental and ecological model of youth racial trauma (DEMYth-RT) states that the main symptoms at the intersection of vulnerability are re-experiencing intrusion, avoidance, negative mood and cognitions, and psychological arousal (Saleem et al., Citation2020). The culturally informed adverse childhood experiences model (C-ACEs) was developed recently to offer a framework that also recognises racism as potentially traumatising (Bernard et al., Citation2021). Using a retrospective research methodology in adult memory, the original adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) model discovered a dose-dependent relationship between the severity of poor mental health and the number of reported ACEs (Cronholm et al., Citation2015; Felitti et al., Citation1998). The C-ACEs highlights that racism is a constant adverse experience in the lives of migrant and racialised youth, to the point that racism operates as a predisposing, precipitating, perpetuating and present factor in the association between historical stress/trauma and mental health outcomes such as post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and anxiety (Bernard et al., Citation2021).

Whether or not they choose to overtly talk to their children about these issues, studies reveal that parents and guardians have a significant role in socialising their kids about racism (Cooley et al., Citation2016; Hughes et al., Citation2016; Neblett et al., Citation2016). This is crucial to comprehend because, despite differences in how acceptable it is to discuss racism publicly, racism continues to have an intertwining micro, meso, and macro impact on people’s lives (Juang et al., Citation2021). In the context of the sociopolitical landscape, Gilroy (Citation1991) wrote extensively about the intrapsychic conflicts that arise when one attempts to integrate identification with one’s racialised identity with identification with one’s national identity amidst dynamic exposures to and negotiations with blatant racism and prejudice. As an example, the status of racialised-ethnic (Black) and national-citizen (British), respectively, as Gilroy (Citation1991) eloquently described, intersect but are generally perceived as incongruent due to the continued sociopolitical marginalisation of Blackness in the vestiges of colonialism and Empire. Thus, how racialised identity develops in connection to various configurations of social and personal identity is historically situated and culturally mediated, specifically because of the complex intersections of racism, racialisation and the sociohistorical conceptualisation of “race” (Austin, 1988; Galliher et al., Citation2017; Syed & Fish, Citation2018).

Making direct reference to the theorising of Franz Fanon (Citation1986, 1967), bell hooks (Citation2014) claimed that the function of racialised identity is to structure an ‘oppositional gaze’ that questions the naturalisation of racist conceptions about what Blackness is. With intersectionality as a conceptual ‘politics of difference’ (Lorde, Citation2019), racialised identity is regarded as one of many intertwined identities - sometimes complimentary, sometimes conflictual - within a wider and deeper perspective of personality (Romero, 2018). Hall (Citation2021) explains how racialised identity development is the effort people make to organise their self-concept by extracting meaning from their situated experiences and by finding common ground through shared narratives and unifying themes. The agentic power of racialised identity development, as positive growth, is contributed to across a lifetime of becoming as well as being (Wright, Citation2004), thus emphasising a dynamic rather than categorically static concept. Racialised identification is also a form of socialisation into a standpoint that emphasises the importance of imaginative (re-)discovery as well as political positioning (Blitz & Greene, Citation2006). According to Patricia Hill Collins’ (Citation1997) view of feminist standpoint theory, a standpoint of racialised identification involves developing an awareness of one’s group history as well as the opportunities and constraints that socially construct one’s group.

For Black people and People of Colour, “the significance of group consciousness, group self-definition, and ‘voice’ within this entire structure of power and experience” refers to how each group member struggles to find ways to come to terms with actual and potential systematic barriers and exclusions (Collins, 1997, p. 397). In the context of mental health, racialised self-identification may have both empowering and marginalising effects that could increase or reduce stress exposure and coping abilities in various contexts. Therefore, the here presented study seeks to address the debate around racism and mental health, by focusing specifically on what Black feminists describe as a critical lens that protects against the deleterious consequences of internalising the “violence, hostility and aggression” of subjugated positionality (hooks, Citation2014, p. 116). With this study, we seek to test if the strength and direction of the association between racism and mental health depends on racialised identity. In other words, we might expect the strength and direction of the association between racism and mental health to change as the level of racialised identity changes. This hypothesis is based on previous research suggesting that racialised identity has a protective role in the association between racism and mental health in adults (Townsend et al., Citation2020). However, results may differ between young people and adults. In this study, we focus on young people (children and adolescents), because their self-concept, in terms of public and private self-consciousness, may be especially sensitive to, for example, racist stereotypes about ‘racial’ differences in school and wider society (Sladek et al., Citation2020).

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

Quantitative primary studies exploring racism and mental health in children and adolescents were searched for and evaluated using a systematic approach. The final search terms are contained in .

Table 1. Boolean search terms.

A restriction for peer-reviewed publications between January 2013 and December 2022 was applied. All studies that reported an interaction effect of racism x racialised identification on a specified mental health outcome were included. This screening yielded 21 articles that were screened in full. Included quantitative, peer-reviewed primary studies reported (1) adjusted effect size estimates (standardized or unstandardised betas) or odd ratios (ORs), (2) self-reported depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, internalising symptoms and externalising symptoms, or individual symptoms such as substance use and hopelessness that could be coded as externalising symptoms or internalising symptoms, (3) effect size of self-reported racialised identification. Qualitative studies were excluded. Articles on adults were also excluded. Cross-sectional and longitudinal studies were included. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) and additional guidance from Borenstein et al (Citation2009) were followed (see Supplement 1) (Page et al., Citation2021).

Data extraction

Two reviewers extracted data from the studies. The following characteristics could be identified as areas for evaluation: (1) forms of racism: vicarious racism, internalised racism, interpersonal racism, and structural racism, and (2) racialised groups: Black people, People of Colour, and Indigenous people. Adjusted effect size measures and, where available, the corresponding confidence interval (CI) or standard error (SE) were extracted. The extracted data is provided in Supplement 1. The risk of bias assessments, which were performed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) (Wells et al., Citation2013), are provided in Supplement 2.

Statistical analysis

In the present study, we examine racialised identity as a possible moderator variable (M) that might explain why racism (Y1) could be related to mental health (Y2) in some youth and not in others as expressed mathematically by Hair et al. (Citation2017) as:

Variations in raw effect sizes were converted or imputed into Pearson’s correlation r (Rodgers & Nicewander, Citation1988). Odds ratios were converted in r, ß values were imputed into r based on the method of Peterson and Brown (Citation2005) and B values were converted into partial correlation p with the formula given by Aloe and Thompson (Citation2013). Meta-analysis was performed, and forest plots were created in RStudio with the {tidyverse} (Wickham et al., Citation2019), {meta} (Balduzzi et al., Citation2019), {metafor} (Viechtbauer, Citation2010), and {dmetar} (Viechtbauer, Citation2010) packages. We applied the formula provided by Cohen (Citation1988) in RStudio to transform Kenny's (Citation2018) thresholds for interpreting the size of moderation: 0.07 represents small moderation, 0.10 represents medium moderation, 0.16 represents large moderation.

Results

Characteristics of the studies

The current meta-analysis is based on data from an ongoing, larger meta-analysis registered on PROSPOERO on the effect of racism in childhood and adolescence (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=248784). Overall, 15, 638 titles and abstracts were screened and 176 studies on racism and mental health were found. After applying the eligibility criteria for the moderated effect of racialised identity, 21 relevant studies were found. Of these, 8 studies could be included in the meta-analysis (see Supplement 1) (Page et al., Citation2021). The total sample size for this meta-analysis is 2146 children and adolescents. The key characteristics of each included study are provided in .

Table 2. Study characteristics.

Summary of associations

In this analysis, “k” refers to the number of effect size estimates included in calculating the summary effect size. As there were only k = 1 effect size estimates for depressive symptoms and k = 3 from the same study for substance use, we focus on a subsequent subgroup analysis for internalising symptoms and externalising symptoms. However, it should be noted that depressive symptoms can be subsumed under the label internalising symptoms and substance use can be subsumed under the label externalising symptoms.

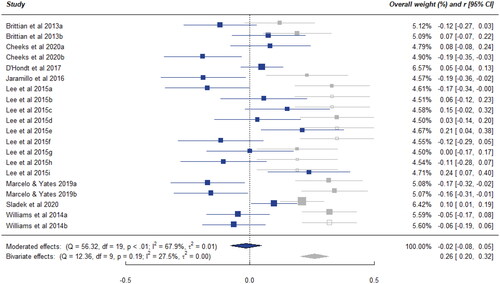

Racism, adverse mental health and racialised identity

We found a medium size effect of racism on adverse mental health in children and adolescents (r = 0.26, 95% CI = 0.20 to 0.32, k = 10) The moderating effect of racialised identity is −0.02 (95% CI = −0-08 to 0.05, k = 20). Therefore, racialised identity is a negligible moderator for the association between racism and adverse mental health (). The relationship between racism and adverse mental health does not significantly depend on different levels of racialised identity. It is not significantly stronger in lower levels of racialised identity nor significantly weaker in higher levels of racialised identity.

Figure 1. Forest plot of meta-analysis comparing the bivariate association between racism and mental health outcomes with the moderating effect of racialised identity on the racism and mental health association. Every bivariate effect corresponds to a grey box (where the hollow grey boxes are duplicates of the above grey box and are excluded from the final pooled calculation) and every moderated effect corresponds to a blue box. The summary effects of the bivariate effects are represented by the grey diamond shape and the moderated effects are represented by the blue diamonds. In addition, we report heterogeneity estimates (I2) and estimates of the between-study variance (τ2). Abbreviations: r = effect size measure Pearson’s correlation coefficient, CI = confidence interval.

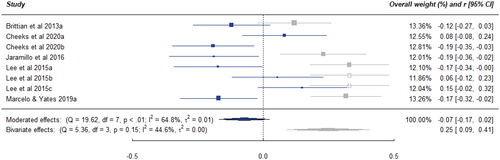

Racism, internalising symptoms and racialised identity

We found a medium size effect of racism on internalising symptoms in children and adolescents (r = 0.25, 95% CI = 0.09 to 0.41, k = 4) The moderating effect of racialised identity is −0.07 (95% CI = −0.17 to 0.02, k = 8). Therefore, racialised identity is a small moderator for the association between racism and internalising symptoms (see ). The relationship between racism and internalising symptoms does depend on different levels of racialised identity. It is slightly stronger in lower levels of racialised identity and slightly weaker in higher levels of racialised identity.

Figure 2. Forest plot of meta-analysis comparing the bivariate association between racism and internalising symptoms with the moderating effect of racialised identity on the racism and internalising symptoms association. Every bivariate effect corresponds to a grey box (where the hollow grey boxes are duplicates of the above grey box and are excluded from the final pooled calculation) and every moderated effect corresponds to a blue box. The summary effects of the bivariate effects are represented by the grey diamond shape and the moderated effects are represented by the blue diamonds. In addition, we report heterogeneity estimates (I2) and estimates of the between-study variance (τ2). Abbreviations: r = effect size measure Pearson’s correlation coefficient, CI = confidence interval.

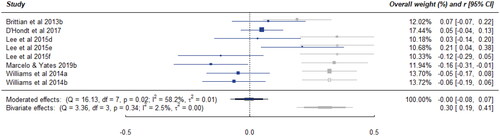

Racism, externalising symptoms and racialised identity

We found a medium size effect between racism and externalising symptoms (r = 0.30, 95% CI = 0.19 to 0.41, k = 4). The moderating effect of racialised identity is −0.00 (95% CI = −0.08 to 0.07, k = 8). Therefore, racialised identity is not a moderator for the association between racism and externalising symptoms. The relationship between racism and externalising symptoms does not depend on different levels of racialised identity (see ).

Figure 3. Forest plot of meta-analysis comparing the bivariate association between racism and externalising symptoms with the moderating effect of racialised identity on the racism and externalising symptoms association. Every bivariate effect corresponds to a grey box (where the hollow grey boxes are duplicates of the above grey box and are excluded from the final pooled calculation) and every moderated effect corresponds to a blue box. The summary effects of the bivariate effects are represented by the grey diamond shape and the moderated effects are represented by the blue diamonds. In addition, we report heterogeneity estimates (I2) and estimates of the between-study variance (τ2). Abbreviations: r = effect size measure Pearson’s correlation coefficient, CI = confidence interval.

Discussion

The primary objective of this meta-analysis was to examine the role of racialised identity in moderating the relationship between racism and adverse mental health in children and adolescents. We conducted a systematic literature search and were able to include effect size estimates from eight studies. In terms of the relationship between racism and mental health, our meta-analysis found that racism increases the overall likelihood of negative mental health outcome: internalising symptoms and externalising symptoms. Our key finding is that racialised identity has a negligible moderating effect on the association between racism and adverse mental health in children and adolescents. While racialised identity had no moderating effect on externalising symptoms, it did have a small moderating effect on internalising symptoms. These findings indicate that the higher the racialised identity, the weaker the link between racism and internalising symptoms. In the impact of racism on internalising symptoms, our results support neurobiological research, which found that increases in racialised identity reduces stress in the relationship between racism and dysregulation in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis (Adam et al., Citation2020). Nonetheless, the number of studies included in this analysis is quite small and therefore our moderation model may not address complex and state-dependent interactions between self-identification, social exclusion stress and mental health as there may be some critical interaction variables not addressed.

Previous research, for example, indicates that Black people and People of Colour (BPoCs) are vulnerable to the internalising of racist ideas and attitudes about their racialised group (David et al., Citation2019). According to institutional racism theory, young BPoCs are exposed to racist attitudes and stereotypes in scholarly endeavours through teaching resources in the formal and hidden curriculum, as well as in interactions with teachers and other adults in schools (Karakayali et al., Citation2022). As a result, they may experience stereotype threat (Seo & Lee, Citation2021), and may disengage from school in accordance with the expectancy-value model of achievement motivation theory (Eccles et al., Citation1983). Our results suggest that disengagement from school resulting from internalised racism may involve externalising behaviours such as reactive aggressions as well as internalising behaviours such as feelings of hopelessness (see also Luthar et al., Citation2021; Njoroge et al., Citation2021; Seaton et al., Citation2022). Internalised racism refers to the acceptance, and endorsement, of derogatory and oppressive stereotypes about one’s racialised group (Jones, Citation2000). Internalised racism has historically received little investigation (Pyke, Citation2010), which is a consequence of the level of stigma the subject has within BPoC groups. However, this is gradually changing, and interest in internalised racism has grown in recent years (e.g. David et al., Citation2019; Tao & Scott, Citation2022). In our meta-analysis, we could only address identity as a factor described in the original investigations. Further studies could distinguish between aspects of empowerment versus internalised racism in self-identification of socially and locally diverse, racialised communities. A nuanced approach describes how racialised identity and internalised racism become intertwined over time and have an impact on mental health (Bailey et al., Citation2022; Willis et al., Citation2021).

James (Citation2022) combined the stigma-induced identity threat model with the minority stress model to explain how internalised racism increases the risk of negative mental health outcomes (Major & O’Brien, Citation2005; Meyer, Citation2003). Group-level recognition of forms of internalised racism and politicised campaigns to combat them have shifted throughout time. The ‘Black is Beautiful’ campaign was especially prominent in the Black community within the 1960s, with a primary emphasis on natural afro hair and on learning to embrace and respect people of darker skin complexion (Camp, Citation2015). The “#BlackGirlMagic” campaign rose to prominence in recent years, with a primary emphasis on highlighting the accomplishments of Black women and girls (Workneh et al., Citation2021). Despite various waves of activism, research suggests that people who live in high-racism communities can become exhausted, making them susceptible to developing adverse mental health outcomes; this condition is referred to as “Black fatigue” and also “battle fatigue” (Winters, Citation2020). “Battle fatigue” is the term used to describe the state of exhaustion that can develop as a result of accumulated interactions with racist hostility throughout the depth and breadth of lived experience (Smith et al., Citation2007). “Battle fatigue” conceptually shares many qualitative similarities with burnout – which is described typically as a work-related mental health consequence and entails exhaustion (that is, chronic fatigue), cynicism (that is, a loss of meaning and purpose), and reduced efficacy (that is, reduced feelings of accomplishment) (Maslach et al., Citation1996; Maslach & Leiter, Citation2016). Although there are qualitative similarities, “battle fatigue” considers the effect of racism on issues unique to racialised identity specific challenges (Gorski, Citation2019). With respect to our results, these considerations suggest that even if largely devoid of internalised racism, identification with one’s racialised group may come at an individually high price – exhaustion, fatigue and ultimately depression or other clinically relevant negative mood states. In terms of coping, Ginwright (Citation2010) proposes a radical healing strategy in the book “Black Youth Rising” that focuses on the support that community-based organisations may provide for young people as they work to overcome the damaging consequences of racism.

Potential diversity in how racialised identity is conceptualised in the data of the underlying studies, in addition to the relatively small number of included studies, constitutes a drawback of this study, which in turn has an impact on the robustness. Racialised identity was conceptualised by the majority of the here included studies as an individualistic concept (e.g. Laursen & Williams, Citation2009). The studies by Meca et al Citation2020 and Sladek et al Citation2020 assessed identity exploration, which is a concept based on the work of Marcia (1966; 1980) derived from Erikson (Citation1950) and represents a person’s effort to gather different perspectives in order to make informed decisions about their respective racialised group positioning. Whilst Brittian et al. (Citation2013) and Williams et al Citation2014 assessed identity diffusion, identity foreclosure and identity achievement, which are identity statuses also based on the work of Marcia (1966; 1980), derived by simultaneously modularising and contrasting identity exploration with commitment to the goals, values and beliefs of racialised identity. The inherent issue is that often racialised identity is a forced choice underpinned by racialisation and racism (macro-level processes of power and inequality) as indicated by biological markers such as skin complexion and social markers such as internal and external identification (by self and others) (Stephan & Stephan, Citation2000). As an attribution ascribed to a person from the outside, racialised identities are laden with racist ideas and stereotypes, and it is the context of these external ascriptions that contributes most significantly to variations in racialised identity trajectories (Appiah, Citation2000). Incongruence between how a person perceives their own racialised identity and how others perceive a person’s racialised identity in terms of how much meaning is assigned to it, what matters, and why can additionally become a source of distress and confusion (Groen et al., Citation2019; Song, Citation2020).

This distress may be ameliorated through socialisation that (re-)connects a person to their racialised identity in terms of heritage and history. This may include the socialisation of positive emotions such as pride around their racialised identity and the socialisation of problem-solving skills to cope with the incongruence and the racism (Cooper & McLoyd, Citation2011). Future research in community-based medicine could explore integrating emotion management in public and private self-consciousness (Browne et al., Citation2022; Hittner and Adam, Citation2020) into models of racialised identity, which is operationalised relationally to impact on the complex aetiology of mental health problems in affected children and adolescents. Emotion management may include focussing on adaptive (positive) mental habits such as activism (Heard-Garris et al., Citation2021). Future research may also seek to focus on the social-contextual dimensions of racialised identity as in a 2022 study by Chen et al, who conceptualised the collectivistic nature of racialised identity as resulting from family and peer socialisation. The point we want to emphasise is that communities can provide learning opportunities and spaces of support, which facilitate a coherent development of component parts of racialised identity that together form a structure such as an ‘oppositional gaze’ (hooks, Citation2014). A collectively constructed identity that provides space and support for the expression of individual experiences may have positive intra- and inter-personal implications for individuals and thus the community (Tribble et al., Citation2019). Further to this, it is suggested that additional research is required that focuses on an affective-behavioural-cognitive conceptualisation of racialised identity development in socially and historically changing circumstances (Heinz et al., Citation2012; Marks et al., Citation2020) – which dynamically positions self in relation to others – to build a more comprehensive moderation model.

Disclosure statement

The authors disclose receipt of the following financial support for the research: Open Access funding provided by the German Federal Ministry for Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth (BMFSFJ).

References

- Achenbach, T. (1991). Manual for the Youth Self-Report and 1991 Profile. University of Vermont, Department of Psychology.

- Adam, E. K., Hittner, E. F., Thomas, S. E., Villaume, S. C., & Nwafor, E. E. (2020). Racial discrimination and ethnic racial identity in adolescence as modulators of HPA axis activity. Development and Psychopathology, 32(5), 1669–1684. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095457942000111X

- Aloe, A. M., & Thompson, C. G. (2013). The synthesis of partial effect sizes. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 4(4), 390–405. https://doi.org/10.5243/jsswr.2013.24

- Appiah, K. A. (2000). Stereotypes and the shaping of identity. California Law Review, 88(1), 41. https://doi.org/10.2307/3481272

- Bailey, T. K. M., Yeh, C. J., & Madu, K. ‑ (2022). Exploring Black adolescent males’ experiences with racism and internalized racial oppression. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 69(4), 375–388. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000591

- Balduzzi, S., Rücker, G., & Schwarzer, G. (2019). How to perform a meta-analysis with R: A practical tutorial. Evidence-Based Mental Health, 22(4), 153–160. https://doi.org/10.1136/ebmental-2019-300117

- Bernard, D. L., Calhoun, C. D., Banks, D. E., Halliday, C. A., Hughes-Halbert, C., & Danielson, C. K. (2021). Making the "C-ACE" for a culturally-informed adverse childhood experiences framework to understand the pervasive mental health impact of racism on black youth. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 14(2), 233–247. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-020-00319-9

- Bhugra, D., Wijesuriya, R., Gnanapragasam, S., & Persaud, A. (2020). Black and minority mental health in the UK: Challenges and solutions. Forensic Science International, 1, 100036. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsiml.2020.100036

- Bianca, C. S. D., Ramona, P. L., & Ioana, M. V. (2022). The relationship between coping strategies and life quality in major depressed patients. The Egyptian Journal of Neurology, Psychiatry and Neurosurgery, 58(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41983-022-00545-y

- Blitz, L. V., & Greene, M. P. (2006). Racism and racial identity: Reflections on urban practice in mental health and social services. Journal of Emotional Abuse: v. 6, no. 2/3. Haworth Maltreatment & Trauma Press.

- Borenstein, M., Hedges, L., Higgins, J., & Rothstein, H. (2009). Introduction to meta-analysis. Wiley.

- Brittian, A. S., Toomey, R. B., Gonzales, N. A., & Dumka, L. E. (2013). Perceived discrimination, coping strategies, and Mexican origin adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing behaviors: examining the moderating role of gender and cultural orientation. Applied Developmental Science, 17(1), 4–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2013.748417

- Browne, R. K., Duarte, B. A., Miller, A. N., Schwartz, S. E. O., & LoPresti, J. (2022). Racial discrimination, self-compassion, and mental health: The moderating role of self-judgment. Mindfulness, 13(8), 1994–2006. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-022-01936-1

- Camp, S. (2015). Black is beautiful: An American history. The Journal of South History, LXXXI(3), 675–690.

- Cheeks, B. L., Chavous, T. M., & Sellers, R. M. (2020). A daily examination of african american adolescents’ racial discrimination, parental racial socialization, and psychological affect. Child Development, 91(6), 2123–2140. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13416

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd Ed.). New York: Routledge.

- Cooley, S., Elenbaas, L., & Killen, M. (2016). Social exclusion based on group membership is a form of prejudice. In Stacey S. Horn, Martin D. Ruck, Lynn S. Liben (Ed.), Equity and Justice in Developmental Science: Implications for Young People, Families, and Communities. (Vol. 51, pp. 103–129). Elsevier Science. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.acdb.2016.04.004

- Cooper, S. M., & McLoyd, V. C. (2011). Racial barrier socialization and the well-being of African american adolescents: The moderating role of mother-adolescent relationship quality. Journal of Research on Adolescence 21(4), 895–903. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2011.00749.x

- Cronholm, P. F., Forke, C. M., Wade, R., Bair-Merritt, M. H., Davis, M., Harkins-Schwarz, M., Pachter, L. M., & Fein, J. A. (2015). Adverse childhood experiences: Expanding the concept of adversity. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 49(3), 354–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2015.02.001

- Cuellar, I., Arnold, B., & Maldonado, R. (1995). Acculturation rating scale for Mexican Americans-II: A revision of the original ARSMA scale. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 17(3), 275–304. https://doi.org/10.1177/07399863950173001

- D’hondt, F., Eccles, J. S., van Houtte, M., & Stevens, P. A. J. (2017). The relationships of teacher ethnic discrimination, ethnic identification, and host national identification to school misconduct of Turkish and Moroccan immigrant adolescents in Belgium. Deviant Behavior, 38(3), 318–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2016.1197004

- David, E. J. R., Schroeder, T. M., & Fernandez, J. (2019). Internalized racism: A systematic review of the psychological literature on racism’s most insidious consequence. Journal of Social Issues, 75(4), 1057–1086. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12350

- Douglass, S., & Umaña-Taylor, A. J. (2015). A brief form of the ethnic identity scale: development and empirical validation. Identity, 15(1), 48–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/15283488.2014.989442

- Eccles, J. S., Adler, T. F., Futterman, R., Goff, S. B., Kaczala, C. M., Meece , et al. (1983). Expectancies, values, and achievement behaviors. In J. T. Spence (Ed.), A series of books in psychology. Achievement and achievement motives: Psychological and sociological approaches. (pp. 75–146). W.H. Freeman.

- Edelbrock, C., & Achenbach, T. M. (1980). A typology of child behavior profile patterns: Distribution and correlates for disturbed children aged 6–16. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 8(4), 441–470. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00916500

- Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and society. New York.

- Fanon, F. (1986, 1967). Black skin, white masks. Liberation classics. Pluto.

- Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., Koss, M. P., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8

- Fisher, C. B., Wallace, S. A., & Fenton, R. E. (2000). Discrimination distress during adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 29, 679–695. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026455906512

- Galliher, R. V., McLean, K. C., & Syed, M. (2017). An integrated developmental model for studying identity content in context. Developmental Psychology, 53(11), 2011–2022. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000299

- Geronimus, A. (1992). The weathering hypothesis and the health of African-American women and infants: evidence and speculations. Ethnicity & Disease, 2(3), 207–221. https://www.jstor.org/stable/45403051

- Geronimus, A. T., Bound, J., Waidmann, T. A., Hillemeier, M. M., & Burns, P. B. (1996). Excess mortality among blacks and whites in the United States. The New England Journal of Medicine, 335(21), 1552–1558. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199611213352102

- Gilroy, P. (1991). There ain’t no black in the Union Jack”: The cultural politics of race and nation. Black Literature and Culture. University of Chicago Press.

- Ginwright, S. A. (2010). Black youth rising: Activism and radical healing in urban America. Teachers College.

- Goodman, R. (1999). The extended version of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire as a guide to child psychiatric caseness and consequent burden. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 40(5), 791–799. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00494

- Gonzales, N. A., Gunnoe, M. L., Samaniego, R., & Jackson, K. (1995). Validation of a multicultural event schedule for adolescents: Paper presented at the Fifth Biennial Conference of the Society for Community Research and Action Chicago, IL.

- Gorski, P. C. (2019). Racial battle fatigue and activist burnout in racial justice activists of color at predominately White colleges and universities. Race Ethnicity and Education, 22(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2018.1497966

- Groen, S. P. N., Richters, A. J. M., Laban, C. J., van Busschbach, J. T., Devillé, W. L., & J., M. (2019). Cultural identity confusion and psychopathology: A mixed-methods study among refugees and asylum seekers in the Netherlands. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 207(3), 162–170. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000935

- Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Gudergan, S. (2017). Advanced issues in partial least squares structural equation modeling (1st). SAGE.

- Hall, S. (2021). Cultural Identity and Diaspora. In S. Hall, P. Gilroy, & R. W. Gilmore (Eds.), Stuart hall: selected writings. Selected writings on race and difference. (pp. 257–272). Duke University Press.

- Harrell, S. P. (1997). The racism and life experience scales. Unpublished instrument. Graduate School of Education and Psychology, Pepperdine University.

- Heard-Garris, N., Boyd, R., Kan, K., Perez-Cardona, L., Heard, N. J., & Johnson, T. J. (2021). Structuring Poverty: How Racism Shapes Child Poverty and Child and Adolescent Health. Academic pediatrics, 21(8S), S108–S116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2021.05.026

- Heinz, A., Bermpohl, F., & Frank, M. (2012). Construction and interpretation of self-related function and dysfunction in Intercultural Psychiatry. European Psychiatry, 27 (Suppl 2), 43. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924-9338(12)75706-1

- Henssler, J., Brandt, L., Müller, M., Liu, S., Montag, C., Sterzer, P., & Heinz, A. (2020). Migration and schizophrenia: Meta-analysis and explanatory framework. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 270(3), 325–335. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-019-01028-7

- Hill Collins, P. (1997). Comment on Hekman’s “Truth and method: Feminist standpoint theory revisited. : Where’s the Power? Signs: Journals of Women in Culture and Society, 22(2)

- Hittner, E. F., & Adam, E. K. (2020). Emotional pathways to the biological embodiment of racial discrimination experiences. Psychosomatic Medicine, 82(4), 420–431. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000792

- hooks, b. (2014). Black looks: Race and representation/bell hooks (Second edition). Routledge.

- Hughes, D. L., Watford, J. A., & Del Toro, J. (2016). A transactional/ecological perspective on ethnic-racial identity, socialization, and discrimination. In Stacey S. Horn, Martin D. Ruck, Lynn S. Liben (Ed.), Equity and Justice in Developmental Science: Implications for Young People, Families, and Communities. (Vol. 51, pp. 1–41). https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.acdb.2016.05.001

- James, D. (2022). An initial framework for the study of internalized racism and health: Internalized racism as a racism‐induced identity threat response. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 16(11). https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12712

- Jaramillo, J., Mello, Z. R., & Worrell, F. C. (2016). ethnic identity, stereotype threat, and perceived discrimination among native American adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence: The Official Journal of the Society for Research on Adolescence, 26(4), 769–775. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12228

- Jones, C. P. (2000). Levels of racism: A theoretic framework and a gardener’s tale. American Journal of Public Health, 90(8), 1212–1215. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.90.8.1212

- Juang, L. P., Moffitt, U., Schachner, M. K., & Pevec, S. (2021). Understanding ethnic-racial identity in a context where “race” is taboo. Identity, 21(3), 185–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/15283488.2021.1932901

- Karakayali, J., Heller, M, & von Unger H. (2022). Rassismus und segregation: Othering in Forschungsprozess zu Schule und Segregation. In I. Siouti, T. Spies, E. Tuider, & E. Yildiz (Eds.), Othering in der postmigrantischen Gesellschaft. (pp. 179–200). Transcript Verlag.

- Kazdin, A. E., French, N. H., Unis, A. S., Esveldt-Dawson, K., & Sherick, R. B. (1983). Hopelessness, depression, and suicidal intent among psychiatrically disturbed inpatient children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 51(4), 504–510. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.51.4.504

- Kenny, D. A. (2018). Moderation. Retrieved from http://davidakenny.net/cm/moderation.htm

- Ketheesan, S., Rinaudo, M., Berger, M., Wenitong, M., Juster, R. P., McEwen, B. S., & Sarnyai, Z. (2020). Stress, allostatic load and mental health in indigenous Australians., 23(5), 509–518. https://doi.org/10.1080/10253890.2020.1732346

- Laursen, B., & Williams, V. (2009). The role of ethnic identity in personality development. In L. Pulkkinen & A. Caspi (Eds.), Paths to Successful Development. (pp. 203–226). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511489761.009

- Lazaridou, F. B., Schubert, S. J., Ringeisen, T., Kaminski, J., Heinz, A., & Kluge, U. (2022). Racism and psychosis: An umbrella review and qualitative analysis of the mental health consequences of racism. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-022-01468-8

- Lee, J. P., Lee, R. M., Hu, A. W., & Kim, O. M. (2015). Ethnic identity as a moderator against discrimination for transracially and transnationally adopted Korean American adolescents. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 6(2), 154–163. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038360

- Lesane-Brown, C. L. (2006). A review of race socialization within Black families. Developmental Review, 26(4), 400–426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2006.02.001

- Lorde, A. (2019). Sister outsider. Penguin modern classics. Penguin Books.

- Luthar, S. S., Ebbert, A. M., & Kumar, N. L. (2021). Risk and resilience among Asian American youth: Ramifications of discrimination and low authenticity in self-presentations. American Psychologist, 76(4), 643–657. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000764

- Major, B., & O'Brien, L. T. (2005). The social psychology of stigma. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 393–421. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070137

- Marcelo, A. K., & Yates, T. M. (2019). Young children’s ethnic-racial identity moderates the impact of early discrimination experiences on child behavior problems. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 25(2), 253–265. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000220

- Marks, A. K., Calzada, E., Kiang, L., Pabón Gautier, M. C., Martinez-Fuentes, S., Tuitt, N. R., Ejesi, K., Rogers, L. O., Williams, C. D., & Umaña-Taylor, A. (2020). Applying the lifespan model of ethnic-racial identity: eploring affect, behaviour and cognition to promote well-being. Research in Human Development, 17(2-3), 154–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427609.2020.1854607

- Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (2016). Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry: Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 15(2), 103–111. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20311

- Maslach, C., Jackson, S. E., & Leiter, M. P. (1996). Maslach burnout inventory manual. (3rd ed.). Consulting Psychologists Press.

- McConaughy, S., & Achenbach, T. (2004). Manual for the ASEBA Test Observation Form. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families.

- McEwen, B. S., & Seeman, T. (1999). Protective and damaging effects of mediators of stress. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 896, 30–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08103.x

- Meca, A., Gonzales-Backen, M., Davis, R., Rodil, J., Soto, D., & Unger, J. B. (2020). Discrimination and ethnic identity: Establishing directionality among Latino/a youth. Developmental Psychology, 56(5), 982–992. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000908

- Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

- Mehran, N., Abi Jumaa, J., Lazaridou, F. B., Foroutan, N., Heinz, A., & Kluge, U. (2022). Spatiality of social stress experienced by refugee women in initial reception centers. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 23(4), 1685–1709. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-021-00890-6

- Neblett, E. W. Jr., Sosoo, E. E., Willis, H. A., Bernard, D. L., Bae, J., & Billingsley, J. T. (2016). Racism. Racial Resilience, and African American Youth Development: Person-Centered Analysis as a Tool to Promote Equity and Justice. Advances in child development and behavior, 51, 43–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.acdb.2016.05.004

- Njoroge, W. F. M., Forkpa, M., & Bath, E. (2021). Impact of racial discrimination on the mental health of minoritized youth. Current Psychiatry Reports, 23(12), 81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-021-01297-x

- Pachter, L. M., Szalacha, L. A., Bernstein, B. A., & Coll, C. G. (2010). Perceptions of racism in children and youth (PRaCY): Properties of a self-report instrument for research on children’s health and development. Ethnicity & Health, 15(1), 33–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557850903383196

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 372, n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

- Peterson, R. A., & Brown, S. P. (2005). On the use of beta coefficients in meta-analysis. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(1), 175–181. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.1.175

- Phinney, J. S., & Ong, A. D. (2007). Conceptualization and measurement of ethnic identity: Current status and future directions. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54(3), 271–281. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.54.3.271

- Pyke, K. D. (2010). What is internalized racial oppression and why don’t we study it? acknowledging racism’s hidden injuries. Sociological Perspectives, 53(4), 551–572. https://doi.org/10.1525/sop.2010.53.4.551

- Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D Scale. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/014662167700100306

- Roach, E. L., Haft, S. L., Huang, J., & Zhou, Q. (2022). Systematic review: The association between race-related stress and trauma and emotion dysregulation in youth of color. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 62(2), 190–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2022.04.013

- Rodgers, J. L., & Nicewander, W. A. (1988). Thirteen ways to look at the correlation coefficient. The American Statistician, 42(1), 59–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/00031305.1988.10475524

- Saleem, F. T., Anderson, R. E., & Williams, M. (2020). Addressing the "myth" of racial trauma: Developmental and ecological considerations for youth of color. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 23(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-019-00304-1

- Saleh, E. A., Lazaridou, F. B., Klapprott, F., Wazaify, M., Heinz, A., & Kluge, U. (2022). A systematic review of qualitative research on substance use among refugees. Addiction, 118(2), 218–253. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.16021

- Scottham, K. M., Sellers, R. M., & Nguyên, H. X. (2008). A measure of racial identity in African American adolescents: The development of the multidimensional inventory of black identity–Teen. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 14(4), 297–306. https://doi.org/10.1037/1099-9809.14.4.297

- Seaton, E. K., Iida, M., & Morris, K. (2022). The impact of internalized racism on daily depressive symptoms among black American adolescents. Adversity and Resilience Science, 3(3), 201–208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42844-022-00061-1

- Seo, E, & Lee, Y. K. ‑ (2021). Stereotype threat in high school classrooms: how it links to teacher mindset climate, mathematics anxiety, and achievement. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50(7), 1410–1423. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-021-01435-x

- Sladek, M. R., Umaña-Taylor, A. J., Oh, G., Spang, M. B., Tirado, L. M. U., Vega, L. M. T., McDermott, E. R., & Wantchekon, K. A. (2020). Ethnic-racial discrimination experiences and ethnic-racial identity predict adolescents’ psychosocial adjustment: Evidence for a compensatory risk-resilience model. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 44(5), 433–440. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025420912013

- Smith, W. A., Allen, W. R., & Danley, L. L. (2007). Assume the position. You Fit the description. American Behavioral Scientist, 51(4), 551–578. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764207307742

- Song, M. (2020). Rethinking minority status and ‘visibility. Comparative Migration Studies, 8(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-019-0162-2

- Stephan, C. W., & Stephan, W. G. (2000). The measurement of racial and ethnic identity. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 24(5), 541–552. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0147-1767(00)00016-X

- Stewart, E. A. (2003). School social bonds, school climate, and school misbehavior: A multilevel analysis. Justice Quarterly, 20(3), 575–604. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418820300095621

- Syed, M., & Fish, J. (2018). Revisiting Erik Erikson’s legacy on culture, race, and ethnicity. Identity, 18(4), 274–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/15283488.2018.1523729

- Tao, C., & Scott, K. A. (2022). Do African American adolescents internalize direct online discrimination? Moderating effects of vicarious online discrimination, parental technological attitudes, and racial identity centrality. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 862557. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.862557

- Townsend, T. G., Kaltman, S., Saleem, F., Coker-Appiah, D. S., & Green, B. L. (2020). Ethnic disparities in trauma-related mental illness: Is ethnic identity a buffer? Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 35(11-12), 2164–2188. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260517701454

- Tribble, B. L. D., Allen, S. H., Hart, J. R., Francois, T. S., & Smith-Bynum, M. A. (2019). no right way to be a black woman": Exploring gendered racial socialization among black women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 43(3), 381–397. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684318825439

- Viechtbauer, W. (2010). Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor Package. Journal of Statistical Software, 36(3), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v036.i03

- Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063

- Wells, G., Shea, B., O’Connell, D., Peterson, J., Welch, V., & Losos, M. (2013). & Tugwell, P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp

- Whitbeck, L. B., Hoyt, D. R., McMorris, B. J., Chen, X., & Stubben, J. D. (2001). Perceived discrimination and early substance abuse among American Indian children. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 42(4), 405–424. https://doi.org/10.2307/3090187

- Wickham, H., Averick, M., Bryan, J., Chang, W., McGowan, L., François, R., Grolemund, G., Hayes, A., Henry, L., Hester, J., Kuhn, M., Pedersen, T., Miller, E., Bache, S., Müller, K., Ooms, J., Robinson, D., Seidel, D., Spinu, V., … Yutani, H. (2019). Welcome to the Tidyverse. Journal of Open Source Software, 4(43), 1686. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.01686

- Williams, J. L., Aiyer, S. M., Durkee, M. I., & Tolan, P. H. (2014). The protective role of ethnic identity for urban adolescent males facing multiple stressors. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(10), 1728–1741. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-013-0071-x

- Willis, H. A., Sosoo, E. E., Bernard, D. L., Neal, A., & Neblett, E. W. (2021). The Associations Between Internalized Racism, Racial Identity, and Psychological Distress. Emerging Adulthood (Print), 9(4), 384–400. https://doi.org/10.1177/21676968211005598

- Winters, M. F. (2020). ‑ Black Fatigue: How Racism Erodes the Mind, Body, and Spirit. Business book summary. Berrett-Koehler.

- Workneh, L., Thompson, C., Ware, J., Odero, D., & Thomas, S. (2021). Good night stories for rebel girls: 100 real-life tales of black girl magic. rebel girls: Vol. 4. Rebel girls.

- Wright, M. M. (2004). Becoming black: Creating identity in the African diaspora/Michelle M. Wright. Duke University Press.

- Zubin, J., & Spring, B. (1977). Vulnerability–a new view of schizophrenia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 86(2), 103–126. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-843x.86.2.103