Abstract

Terrorist attacks can be seen as the ultimate wicked problem. After 9/11, terrorists moved from so-called ‘spectacular’ events to relatively low-intensity attacks against individuals and groups. The emergence of what has become known as the ‘home-grown’ terrorist has added a further dimension to the ‘wicked’ nature of the problem. This paper considers the UK’s CONTEST and PREVENT strategies as a policy response to the threats from terrorism and the impact that the policies themselves can have on the radicalization of individuals. The author highlights some of the limitations of the PREVENT strand of the overall strategy and the constraints that are imposed on government policies by failing to take a holistic perspective on the nature of the problem.

‘Wicked’ problems can’t be solved, but they can be tamed. Increasingly, these are the problems strategists face-and for which they are ill equipped (Camillus, Citation2008, p. 98).

The 21st century has seen an increased interest in the processes by which terrorism can be dealt with as a policy problem. The attacks of 9/11, and those that have followed, have marked a shift in the attack strategies of international terrorists towards indiscriminate mass-casualty events within Western countries (Tucker, Citation2001; Hoffman, Citation2002; Duyvesteyn, Citation2004; Kurtulus, Citation2011). More recently, encouragement has been made from Al QaedaFootnote* to mount individual attacks using knives, thereby increasing the diversity of attack threats. The subsequent public policy debates have centred on the nature and evolution of such attack strategies and the defences that can be deployed against them; the religious and ideological motivations that underpin the violence; the use, or intended use, of weapons of mass destruction; and the role of social media in shaping the mechanisms of radicalization (Asal et al., Citation2009; Browne and Silke, Citation2011; Kurtulus, Citation2011; Gill et al., Citation2013; Coppock and McGovern, Citation2014). Against this complex background, the issue of whether terrorism is a phenomenon that can be solved or tamed lies at the heart of the opening quotation from Camillus and it is also a central element of whether it is a wicked policy problem.

‘Wicked’ problems (Churchman, Citation1967; Rittel and Webber, Citation1973) have been the subject of considerable debate within public management (Weber and Khademian, Citation2008; Head and Alford, Citation2015), but the policy responses made to them have, on occasions, perpetuated and even escalated the problems (Kellner, Citation2002; Bergen and Reynolds, Citation2005; Kennedy-Pipe and Vickers, Citation2007). Like many other forms of public sector crisis decision-making, the threats from terrorist attacks generate problems around the management of various agencies and networks, information-sharing (especially in terms of sensitive information), and the challenges associated with the control of uncertain outcomes (Kapucu and Garayev, Citation2011; Robinson et al., Citation2013; Lecy et al., Citation2014). The adaptive nature of terrorism has also generated challenges for both policy-makers and managers across a range of public and private sector organizations. The result is an ongoing ‘arms race’ between attackers and defenders in which the terrorists seek to find gaps within organizational controls and the defenders attempt to close those gaps and further strengthen their control processes (Faria, Citation2006; English, Citation2013). In this context, terrorists are innovative and, increasingly, devoid of a constraining ethical basis for behaviour, which means that the potential range of targets that has to be defended is considerable and this impacts upon information-sharing and analysis (Drake, Citation1998; Boin and Smith, Citation2006; Asal et al., Citation2009; Fischbacher-SmithandFischbacher-Smith,2013; Fischbacher-Smith et al., Citation2010; Gill et al., Citation2013). As a result, terrorism could be seen as the ultimate wicked problem for public management due to the adaptive nature of the principal actors, the nature of communication and information-gathering, and the capability development and learning around attack strategies that has been generated in other conflict zones (and disseminated to interested parties) (Denning, Citation2010; English, Citation2013; Byman, Citation2014, Citation2015).

Terrorist threats as wicked problems

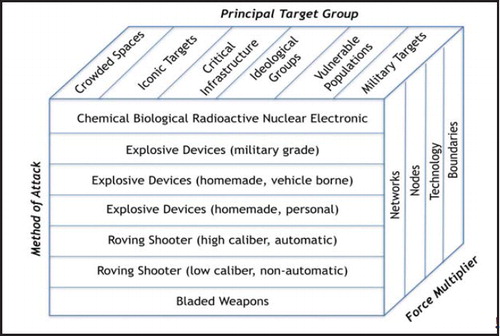

A key challenge arises from the range of available targets and the methods employed by terrorist groups to cause harm. illustrates the policy space in which public management organizations have to deal with the range of threats from terrorist groups, whether foreign or domestic. What makes terrorism such a wicked policy problem is the diversity that is present within the various attack vectors that are available to them (and the associated intensity of those attacks); the potential range of targets that are open to being attacked; and the potential force multipliers that can be found within the urban and organizational spaces in which they choose to mount their attack. For example 9/11 was marked by its destructive potential, but was implemented by the use of small, bladed weapons that were carried on board aircraft, thereby allowing the hijackers to bypass multiple layers of controls that were designed to prevent such hostile actions. By then using the aircraft themselves as weapons, the hijackers were able to generate a force multiplier effect that was far in excess of the intensity of the initial attack on board the aircraft. The asymmetrical impact of the damage caused was also beyond the scale of what would normally have been expected, and the attackers were able to expose other weaknesses in controls across the aviation system to generate harm. Subsequent attacks against aviation by Al Qaeda, its affiliates, and other groups inspired by that ideology have also showed considerable levels of innovation in pursuit of the goal of mass-casualty events (Oh et al., Citation2011; Gill et al., Citation2013; Kollars and Brister, Citation2014; Hemmingby and Bjørgo, Citation2016). This has included, the so-called ‘shoe bomber’, the UK-based liquid bomb plot, and the use of explosive underwear in failed attempts to bring down airliners. While these attacks were unsuccessful, they had the effect of highlighting the vulnerabilities within the system (Clarke and Soria, Citation2009; Sandler, Citation2011; Gill et al., Citation2013; Hastings and Chan, Citation2013). The economic impact of the plots was also an integral part of the over-arching Al Qaeda strategy and remains an active component of the group’s strategy.

The shootings in Orlando in June 2016 also illustrate the wicked nature of such attacks from a policy perspective. The attack marked the worst case of civil gun violence in America’s recent history and its categorization is an important element in the formulation of policy responses to it. Was this an act of terror or a hate crime perpetrated against the LGBT community by a violent individual? As Islamic State took responsibility for the attack and the perpetrator also made phone calls stating his affiliation to the group, the FBI investigated it as a terrorist incident. In this case, it can be considered as the worst terrorist attack in the USA since 9/11. However, it was also clearly an attack on the LGBT community itself and President Obama referred to it as both an act of terror and one of hate. This is not the first time that such an attack has been seen through multiple lenses. For example, in 1999, a nail bomb was placed in the Admiral Duncan pub in London’s Soho district, which was a popular venue for the LGBT community in the area (Newburn and Matassa, Citation2002; Blackbourn, Citation2006; Dwyer, Citation2014). The perpetrator of the bombing was neo-nazi David Copeland (Bowling, Citation2000; Greaves, Citation2000) and, in many respects, he was an early example of what has now become known as ‘lone wolf’ terrorism (Spaaij, Citation2012). This attack on the LGBT community in London has been seen as a watershed in the creation of a supportive relationship between the community and the police (Dwyer, Citation2014)—a process that might not have occurred had the attack been labelled as a terrorist act. Thus, the nuances of the categorization can have wide implications for policy and practice.

The second issue of note, and one that is pertinent to the Orlando shootings, concerns the definition of terrorism itself. There has been considerable debate over the exact meaning of the term and the analytical problems that this lack of an accepted definition brings (Tucker, Citation2001; Ganor, Citation2002; Hoffman, Citation2002; Duyvesteyn, Citation2004; Hülsse and Spencer, Citation2008; English, Citation2009; ClarkeandSoria,2010).English(Citation2009)highlights both the practical and the analytical aspects of terrorism and points to their symbiotic nature. He argues that it is difficult to manage a policy issue when a definition of the core term is ambiguous and, in some cases, defined differently by agencies operating within the same country. He also highlights the different definitional challenges that can arise if terrorism is framed in terms of the underlying ideology, motivations, and the targets chosen (English, Citation2009). It is particularly challenging when one of the hallmarks of terrorist acts is increasingly framed in terms of the innovations that they undertake to bypass organizational controls to cause harm.

As the perpetrator in the Orlando shootings had been interviewed by the FBI about his views, then the case highlights a third issue around such attacks. This relates to the ‘calculative practices’ (Miller, Citation2001) associated with the determination of risk in such cases, where the evidential basis for risk is shrouded in uncertainty and where, even with the benefit of hindsight, prediction is still an imprecise process!

Given the ambiguity that exists around the exact nature of what constitutes terrorism, its principal characteristics, the difficulties associated with the determination of risk, and the points of intervention that are available to policy-makers, then it should not be surprising that it meets many of the main elements of a wicked problem as set out by Rittel and Webber (Citation1973). provides an illustration of the nature of terrorism set against the main elements of the wicked problem construct. While it is not meant to be an inclusive listing, illustrates how these examples of terrorism can be set against the main elements of wicked problems. The paper now turns its attention to considering the challenges that terrorism generates for public policy. It begins by looking at the range of threats that exist within the counter-terrorism policy space and then looks in more detail at the UK’s policy response.

Table 1. The nature of terrorism versus the main elements of the wicked problem construct.

CONTEST: the UK’s counter-terrorism strategy

The range of current terrorist threats has prompted many Western governments to seek to identify and disrupt the processes by which terrorists become radicalized into committing violent acts and also disrupting the networks that underpin this process. In the UK, the main policy instrument currently used to deal with terrorism is the CONTEST strategy (HM Government, Citation2009, Citation2011a). CONTEST has four main elements: Pursue, Prevent, Protect, and Prepare (HM Government, Citation2009). These elements are interlinked but invariably involve different organizations, with different cultures, and can generate a range of issues around information-sharing protocols. Again, this can be seen to contribute to the maintenance of terrorism policy as a wicked problem due to the different perspectives that are brought to bear on it, the policy strategies aimed at resolving it, and the challenges around information-sharing among the various organizations charged with implementing the strategy.

The development of the CONTEST strategy has evolved since the first report was published in 2003 (Home Affairs Committee, Citation2009; HM Government, Citation2009, Citation2011a) and a key element in its evolution has been that of PREVENT which is aimed, as its name implies, at preventing vulnerable individuals from becoming radicalized (HM Government, Citation2009, Citation2011b, 2015; Coppock and McGovern, Citation2014). The PREVENT strategy seeks to identify and respond to early indications of behavioural changes, and is held to be grounded in psychological theories and particularly around the processes that exist in the various channels through which radicalization occurs (HM Government, Citation2012, Citation2015). In the Queen’s speech made at the opening of Parliament in May 2016, the UK government set out its next phase for the development of its counter-radicalization strategy. However, despite the claims around the theoretical basis of the process, the PREVENT strategy has not been met with universal approval and there have been concerns expressed about the focus of the policy (Kundnani, Citation2012; Sukarieh and Tannock, Citation2016).

While the UK government’s strategies are claimed to focus on all forms of violent extremism (which transcend a range of religious and socially-motivated ideologies), much of the focus has been seen to be on extremist Islamist groups and their explicit strategies of radicalization. The reason for this focus is that these extremist groups have shown themselves to be particularly effective at radicalizing young people in large numbers and defining those who will not join their jihad as ‘apostate’. The stated strategy of Islamic State/ Daesh, for example, is to ensure that they destroy the ‘grey zone’ that is inhabited by those Muslims who do not share their extremist views (Ahmed, Citation2015; Anon., Citation2015). The counter-radicalization policies of Western governments have also been used to illustrate the ‘oppression’ and victimization that Islamic State and Al Qaeda are claiming to be fighting against.

As a concept, ‘radicalization’ is also something of a contested term (Sedgwick, Citation2010; Kundnani, Citation2012, Citation2014) and this generates ambiguities around the processes that underpin it—if agreement can’t be reached on the parameters of the problem then it will be difficult, if not impossible, to agree on a policy approach to it. For some, the definition of radicalization chosen by policy-makers serves to construct large segments of society as suspect communities (Kundnani, Citation2012), with the attendant problems around social cohesion that such stigmatization creates. Again, this lack of clarity around the parameters of the problem and the different views held by stakeholders are important elements in the generation of a wicked problem.

As part of the wicked problem argument, it is also necessary to assess whether the PREVENT strategy and the associated Channel framework (HM Government, Citation2012, Citation2015) are able to meet the performance criteria for the design of such a socio-technical system. In particular, there are questions about the potential gaps that exist between the theoretical basis for the policy and its use in practice. Any assessment of the effectiveness of PREVENT should require an appraisal of whether there is inter-organizational consensus around the main ‘source types’ that serve to shape the cultural dynamics of the process (Reason, Citation1987, Citation1993, Citation1997)—namely, commitment, awareness and competence—and the role that these cultural artifacts can play around managing and disrupting the processes of radicalization. Put another way, if the various organizations involved in PREVENT do not have the commitment to address the problem, then they will not generate the awareness that is needed to identify and respond to the early warnings of radical behaviours, or develop the competencies needed to intervene in an effective manner. As many of these partners are public sector organizations—notably, education, social work, the prison service, and the National Health Service—then it is not surprising that there is some opposition to PREVENT among those who are required to implement it (Anon., Citation2014; O’Donnell, Citation2016; Saeed and Johnson, Citation2016). In addition, there is also the issue of whether those organizations also have the capabilities (as well as the commitment) in terms of identifying early-stage radicalization and reporting those concerns to the police. This is an issue of particular concern within education where debating extremist views is seen as an essential part of countering them (Brown and Saeed, Citation2015; Davies, Citation2016; Durodie, Citation2016; Saeed and Johnson, Citation2016). Maintaining awareness within and between these various organizations is also likely to be problematic and expensive to implement. Even at this superficial level, it can be argued that the current PREVENT strategy also contributes to the framing of counter-terrorism as a wicked problem because of the inter-linked nature of the issues around implementation, the different perspectives held by stakeholders, and the judgmental nature of the intervention process at the operational level.

The source types identified by Reason will also have a significant impact on an organization’s abilities to develop a minimum critical specification for the processes in question (Cherns, Citation1976, Citation1987). Within the context of PREVENT, this will relate to the various task demands that the implementing organizations face as a result of dealing with radicalization processes. A number of interlinked issues and challenges (May, Citation2011; Parker, Citation2013, Citation2015) impact upon the implementation of PREVENT within public sector organizations.

First, the strategy has to deal with a perverse ideology that provides both a theological, political, and in some cases an intellectual rationale for the terrorists’ actions. While this ideology is often abhorrent to many, it does seem able to strike a chord among some young and disaffected individuals.

Second, a key driver for this disaffection is seen to be generated by conflict and instability in a number of countries and especially where the crusader analogy has been used to evoke images of a holy war (Ford, Citation2001; Waldman and Pope, Citation2001; Kellner, Citation2004; O’Donnell, Citation2004; Mazid, Citation2007). Unless PREVENT takes account of the role played by UK foreign policy in shaping the nature of that conflict and associated instability, then it will continue to allow the propagation of the ideologies around exploitation and oppression that underpin radicalization. The processes and tools available for the dissemination of ideas around such conflicts are also important.

The use of modern technology is the third core element that can confound the success of the PREVENT strategy, as terrorist groups are able to utilize those technologies as both a means of disseminating their ideological messages but also, in the case of critical infrastructures, as a potential target that will cause disruption to Western economies (Tsfati and Weimann, Citation2002; Conway, Citation2006; Denning, Citation2010; Klausen, Citation2015). The obvious tensions here relate to the freedom of speech and expression (within the limits of the law), that is the cornerstone of democratic societies, and the need to curtail all forms of inflammatory communication. What is evident is that both Al Qaeda and Islamic State are adept in the use of social media and other forms of communication to spread their message.

Each of these three elements has the potential to add to the framing of terrorism as a wicked policy problem and they directly impact on the specific outcomes of radicalization that are the focus of attention within the PREVENT strategy. The interactions between these four main elements (perverse ideology; conflict and instability; modern technology; radicalization) generate a range of issues at the points where they overlap. Again, these second-order issues can contribute to the processes around the generation of a wicked problem. These are:

Core psychological processes around radicalization—the processes here are complex and the theoretical processes around radicalization are often simply ill-understood. The issues here sit at the interface between psychology and sociology and terrorism should not be characterized as a mental health problem, although there will be some individuals attracted to the cause that will have such a diagnosis. Many of these issues sit with areas relevant to social psychology, especially around group dynamics, leadership, and identity (Reicher and Haslam, Citation2016). In addition to the processes surrounding psychological characteristics and socialization mechanisms, there are challenges around communication, the power of beliefs and values, and the role that trust plays in dealing with the conflicting messages that emerge from various sources. The ability to shift away from a particular ideological stance is especially challenging as it often involves changes to the core beliefs and values of the individual. This central core of psycho-social elements also contributes to the wicked problem categorization of terrorism due to the difficulties in framing them, their interlinked nature, the unique conditions prevailing (in space and time) at the point of radicalization, and the different world-views held by the various actors that help to determine the acceptance or rejection of different ideologically-based claims.

Conflict provides a sense of injustice that both fuels and feeds off a pervasive ideology. It also generates a diaspora that can serve to heighten the sense of injustice among immigrants who are marginalized. Many of the issues raised in the media around the movements of people from war zones in Syria and Iraq have centred on the potential vulnerabilities of those groups to radicalization. Invariably, many of these claims are not evidence-based but they can serve to fuel distrust among some groups in society who see refugees as a potential threat (both economically and socially), thereby adding to the potential marginalization of those communities. To be successful, PREVENT also has to deal with the radical (and often xenophobic) views of those groups within society rather than being seen to simply target Muslim communities. It also needs to work to refute erroneous claims made within elements of the media around the perceived risks of domestic-terrorists by providing a more structured, evidence-based approach to challenging such views.

These international conflicts also drive the processes of radicalization by providing additional ‘evidence’ that can be used in support of the ideological stance taken by radicalized groups. That sense of injustice can then carry over into a domestic setting in which national and international views around injustice can feed off each other (Dalgaard-Nielsen, Citation2010; Bangstad, Citation2013; Borum, Citation2014; Coppock and McGovern, Citation2014).

Modern technology provides the mechanisms by which a malevolent ideology is transmitted. It also generates the mechanisms by which tactical information around attack mechanisms is shared among those who have a predisposition to act on their sense of injustice and other grievances.

Radicalized groups and individuals can also use modern technology as an attack vector to cause maximum harm by attacking infrastructures that Western countries rely on. The vulnerability of critical national infrastructure via attacks on the computer network is an issue that has attracted attention from both the policy and the academic communities (Boin and Smith, Citation2006; Cavelty, Citation2008; Geers, Citation2009; Rudner, Citation2013).

There are, therefore, significant challenges around the ways in which CONTEST and PREVENT are implemented and which may also serve to contribute to the maintenance of the current set of terrorist threats being considered as a wicked problem. The management of counter-terrorism policy remains a challenge for public management and one that is likely to continue to prove both problematic and persistent.

Conclusions

This paper has sought to show that the management of terrorist-related policies has some deep-rooted elements that have served to generate a wicked problem and will mitigate against effective intervention through PREVENT. To-date, there has been little discussion of these challenges within the ‘management’ academy, despite the potential impact that terrorism has to disrupt the effective working of organizations across both the public and private sector and this, combined with what could be seen as a relative lack of engagement with research in forensic and social psychology, would suggest that the existing policy problems are unlikely to become any less wicked in the foreseeable future.

The paper highlighted the ways in which terrorism can be framed as a wicked policy problem, by focusing on the nature of the UK’s policy response and the challenges that it creates in terms of making an effective contribution to the policy task demands that terrorism generates. In particular, the paper argues that the main policy challenges relate to the difficulties around the management of inter-agency networks; the problems associated with disrupting the dissemination of terrorist ideologies (while not constraining freedom of speech); and a range of issues around information-sharing within a secure policy environment. These issues then interact with the difficulties associated with dealing with a dynamic, potentially-transient, trans-national, and hostile set of actors. The result of these interactions is the creation of an extremely complex policy space that is essentially ‘wicked’ in both the nature of the hostile actors’ intent and the problems generated for security agencies and policy bodies in terms of response.

Additional work is needed to consider how the design of such policy interventions around terrorism can be more evidence-based and especially in terms of the evidence associated with the creation of policy instruments such as PREVENT and CONTEST. There are, of course, considerable challenges here for the academy in helping practitioners to engage with that evidence base and these centre around access to information about the practices of security and its relationship to other forms of public management; the applicability of more general theories around public management to the security space; and the development of a consensus within the academy itself and especially around the main calculative processes that underpin terrorism policies. These remain quite significant barriers to the development of research that could serve to help shape policy in a more effective manner. There is also a clear need to ensure that the underpinning psychological research that informs processes of counter-radicalization is robust and effectively grounded in the specific characteristics of the various groups that are in danger of being radicalized. At present, the current policy is too broad in its scope, puts the responsibilities for identifying early-stage radicalization on organizations for whom it is not their primary concern (and for which they are ill-equipped), and there is an insufficient research evidence base available to them to show how effective the various forms of intervention might be. Recent concerns expressed by those who will now be charged with implementing PREVENT have pointed to this lack of an evidence base and the challenges associated with addressing extremist views, especially without appropriate training for the task. As a consequence, dealing with terrorist threats is likely to remain a wicked policy problem and one that will continue to evolve and challenge public management to respond in an effective manner.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Moira Fischbacher-Smith and Michaela Lavender for comments on an earlier version of this paper. All errors of omission and commission remain those of the author. The research that underpins this paper was funded by the EPSRC under a project entitled ‘Under dark skies: port cities, extreme events, multi-scale processes and the vulnerability of controls around counter-terrorism’, EPRSC EP/G004889/1.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Denis Fischbacher-Smith

Denis Fischbacher-Smith is Research Chair in Risk and Resilience, Adam Smith Business School, University of Glasgow, UK.

Notes

* The notion of ‘knife revolutionaries’ was set out in the Al Qaeda magazine Inspire (Spring 2016, Issue 15).

References

- Ahmed, N. M. (2015), ISIS wants to destroy the ‘grey zone’. Here’s how we defend it (www.opendemocracy.net).

- Anon. (2014), My NHS counter-terrorism training session (www.cageuk.org).

- Anon. (2015), The extinction of the grey zone. Dabiq, Issue 7 (1436 Rabi’ Al-Akhir), pp. 54–66.

- Asal, V. H. et al. (2009), The softest of targets: a study on terrorist target selection. Journal of Applied Security Research, 4, 3, pp. 258–278.

- Bangstad, S. (2013), Inclusion and exclusion in the mediated public sphere: the case of Norway and its Muslims. Social Anthropology, 21, 3, pp. 356–370.

- Bergen, P. and Reynolds, A. (2005), Blowback revisited. Today’s insurgents are tomorrow’s terrorists. Foreign Affairs, 84, 6, pp. 2–6.

- Blackbourn, D. (2006), Gay rights in the police service. Criminal Justice Matters, 63, 1, pp. 30–31.

- Boin, A. and Smith, D. (2006), Terrorism and critical infrastructures: implications for public– private crisis management. Public Money & Management, 26, 5, pp. 295–304.

- Borum, R. (2014), Psychological vulnerabilities and propensities for involvement in violent extremism. Behavioral Sciences and the Law, 32, 3, pp. 286–305.

- Bowling, B. (2000), Racist offenders: punishment, justice and community safety. Criminal Justice Matters, 42, 1, pp. 30–31.

- Brown, K. E. and Saeed, T. (2015), Radicalization and counter-radicalization at British universities: Muslim encounters and alternatives. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 38, 11, pp. 1952–1968.

- Browne, D. and Silke, A. (2011), The impact of media on terrorism and counter-terrorism. In Silke, A. (Ed), The Psychology of Counter-Terrorism (Routledge).

- Byman, D. (2014), The intelligence war on terrorism. Intelligence and National Security, 29, 6, pp. 837–863.

- Byman, D. (2015), The homecomings: what happens when Arab foreign fighters in Iraq and Syria return? Studies in Conflict and Terrorism, 38, 8, pp. 581–602.

- Camillus, J. C. (2008), Strategy as a wicked problem. Harvard Business Review, 86, 5, pp. 98–101.

- Cavelty, M. D. (2008), Cyber-terror—looming threat or phantom menace? Journal of Information Technology and Politics, 4, 1, pp. 19–36.

- Cherns, A. (1976), The principles of sociotechnical design. Human Relations, 29, 8, pp. 783–792.

- Cherns, A. (1987), Principles of socio technical design revisited. Human Relations, 40, 3, pp. 153–161.

- Churchman, C. W. (1967), Wicked problems. Management Science, 14, 4, pp. B141–B142.

- Clarke, M. and Soria, V. (2009), Terrorism in the UK. RUSI Journal, 154, 3, pp. 44–53.

- Clarke, M. and Soria, V. (2010), Terrorism. The new wave. RUSI Journal, 155, 4, pp. 24–31.

- Conway, M. (2006), Terrorism and the internet. Parliamentary Affairs, 59, 2, pp. 283–298.

- Coppock, V. and McGovern, M. (2014), ‘Dangerous minds’? Children and Society, 28, 3, pp. 242–256.

- Dalgaard-Nielsen, A. (2010), Violent radicalization in Europe. Studies in Conflict and Terrorism, 33, 9, pp. 797–814.

- Davies, L. (2016), Security, extremism and education. British Journal of Educational Studies, 64, 1, pp. 1–19.

- Denning, D. E. (2010), Terror’s web. In Jewkes, Y. and Yar, M. (Eds), Handbook on Internet Crime (Routledge), pp. 194–213.

- Drake, C. J. M. (1998), The role of ideology in terrorists’ target selection. Terrorism and Political Violence, 10, 2, pp. 53–85.

- Durodie, B. (2016), Securitising education to prevent terrorism or losing direction? British Journal of Educational Studies, 64, 1, pp. 21–35.

- Duyvesteyn, I. (2004), How new is the new terrorism? Studies in Conflict and Terrorism, 27, 5, pp. 439–454.

- Dwyer, A. (2014), Pleasures, perversities, and partnerships. In Peterson, D. and Panfil, R. V. (Eds), Handbook of LGBT Communities, Crime, and Justice (Springer), pp. 149–164.

- English, R. (2009), Terrorism: How to Respond (Oxford University Press).

- English, R. (2013), Terrorist innovation and international politics: lessons from an IRA case study? International Politics, 50, 4, pp. 496–511.

- Faria, J. R. (2006), Terrorist innovations and anti-terrorist policies. Terrorism and Political Violence, 18, 1, pp. 47–56.

- Fischbacher-Smith, D. and Fischbacher-Smith, M. (2013), The vulnerability of public spaces: challenges for UK hospitals under the ‘new’ terrorist threat. Public Management Review, 15, 3, pp. 330–343.

- Fischbacher-Smith, D., Fischbacher-Smith, M. and BaMaung, D. (2010), Where do we go from here? The evacuation of city centres and the communication of public health risks from extreme events. In Bennett, P. et al. (Eds), Risk Communication and Public Health (Oxford University Press), pp. 97–114.

- Ford, P. (2001), Europe cringes at Bush ‘crusade’ against terrorists. Christian Science Monitor (19 September).

- Ganor, B. (2002), Defining terrorism. Police Practice and Research, 3, 4, pp. 287–304.

- Geers, K. (2009), The cyber threat to national critical infrastructures. Information Security Journal: A Global Perspective, 18, 1, pp. 1–7.

- Gill, P. et al. (2013), Malevolent creativity in terrorist organizations. Journal of Creative Behavior, 47, 2, pp. 125–151.

- Greaves, I. (2000), Terrorism—new threats, new challenges? RUSI Journal, 145, 5, pp. 15–20.

- Hastings, J. V. and Chan, R. J. (2013), Target hardening and terrorist signaling: the case of aviation security. Terrorism and Political Violence, 25, 5, pp. 777–797.

- Head, B.W. and Alford, J. (2015), Wicked problems: implications for public policy and management. Administration and Society, 47, 6, pp. 711–739.

- Hemmingby, C. and Bjørgo, T. (2016), Breivik in a comparative perspective. The Dynamics of a Terrorist Targeting Process: Anders B. Breivik and the 22 July Attacks in Norway (Palgrave Macmillan), pp. 87–107.

- HM Government (2009), Pursue Prevent Protect Prepare. The United Kingdom’s Strategy for Countering International Terrorism, Cm 7547 (TSO).

- HM Government (2011a), CONTEST. The United Kingdom’s Strategy for Countering Terrorism, Cm 8123 (TSO).

- HM Government (2011b), Prevent Strategy, Cm 8092 (TSO).

- HM Government (2012), Channel: Vulnerability Assessment Framework (Home Office).

- HM Government (2015), Channel Duty Guidance: Protecting Vulnerable People from Being Drawn into Terrorism (TSO).

- Hoffman, B. (2002), Rethinking terrorism and counterterrorism since 9/11. Studies in Conflict and Terrorism, 25, 5, pp. 303–316.

- Home Affairs Committee (2009), Project CONTEST: The Government’s Counter-Terrorism Strategy. Ninth Report of Session 2008-09, HC 212.

- Hülsse, R. and Spencer, A. (2008), The metaphor of terror: terrorism studies and the constructivist turn. Security Dialogue, 39, 6, pp. 571–592.

- Kapucu, N. and Garayev, V. (2011), Collaborative decision-making in emergency and disaster management. International Journal of Public Administration, 34, 6, pp. 366–375.

- Kellner, D. (2002), September 11, terrorism and blowback. CSCM, 2, 1, pp. 27–39.

- Kellner, D. (2004), 9/11, spectacles of terror and media manipulation. Critical Discourse Studies, 1, 1, pp. 41–64.

- Kennedy-Pipe, C. and Vickers, R. (2007),‘Blowback’ for Britain: Blair, Bush and the war in Iraq. Review of International Studies, 33, 2, pp. 205–221.

- Klausen, J. (2015), Tweeting the jihad: social media networks of Western foreign fighters in Syria and Iraq. Studies in Conflict and Terrorism, 38, 1, pp. 1–22.

- Kollars, N. A. and Brister, P. D. (2014), Terrorists that couldn’t: seeing terrorist innovation as a risky venture. Homeland Security Review, 8, pp. 199–218.

- Kundnani, A. (2012), Radicalisation: the journey of a concept. Race and Class, 54, 2, pp. 3–25.

- Kundnani, A. (2014), The Muslims are Coming! (Verso).

- Kurtulus, E. N. (2011), The ‘new terrorism’ and its critics. Studies in Conflict and Terrorism, 34, 6, pp. 476–500.

- Lecy, J. D., Mergel, I. A. and Schmitz, H. P. (2014), Networks in public administration. Public Management Review, 16, 5, pp. 643–665.

- May, T. (2011), Prevent strategy. Hansard (7 June), Vol. 529.

- Mazid, B.-e. M. (2007), Presuppositions and strategic functions in Bush’s 20/9/2001 speech. Journal of Language and Politics, 6, 3, pp. 351–375.

- Miller, P. (2001), Governing by numbers. Social Research, 68, 2, pp. 379–396.

- Newburn, T. and Matassa, M. (2002), Policing hate crime. Criminal Justice Matters, 48, 1, pp. 42–43.

- O’Donnell, M. (2004), ‘Bring it on’: the apocalypse of George W. Bush. Media International Australia incorporating Culture and Policy, 113, 1, pp. 10–22.

- O’Donnell, A. (2016), Securitisation, counterterrorism and the silencing of dissent. British Journal of Educational Studies, 64, 1, pp. 53–76.

- Oh, O., Agrawal, M. and Rao, H. R. (2011), Information control and terrorism. Information Systems Frontiers, 13, 1, pp. 33–43.

- Parker, A. (2013), The enduring terrorist threat and accelerating technological change. Address to RUSI (www.mi5.gov.uk).

- Parker, A. (2015), Director general speaks on terrorism, technology and oversight. Address to RUSI (www.mi5.gov.uk).

- Reason, J. T. (1987), An interactionist’s view of system pathology. In Wise, J. A. and Debons, A. (Eds), Information Systems: Failure Analysis (Springer), pp. 211–220.

- Reason, J. T. (1993), Managing the management risk. In Wilpert, B. and Qvale, T. (Eds), Reliability and Safety in Hazardous Work Systems (Lawrence Erlbaum), pp. 7–22.

- Reason, J. T. (1997), Managing the Risks of Organizational Accidents (Ashgate).

- Reicher, S. D. and Haslam, S. A. (2016), Fueling extremes. Scientific American Mind, 27, 3, pp. 34–39.

- Rittel, H. W. J. and Webber, M. M. (1973), Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sciences, 4, 2, pp. 155–169.

- Robinson, S. E. et al. (2013), The core and periphery of emergency management networks. Public Management Review, 15, 3, pp. 344–362.

- Rudner, M. (2013), Cyber-threats to critical national infrastructure. International Journal of Intelligence and Counter Intelligence, 26, 3, pp. 453–481.

- Saeed, T. and Johnson, D. (2016), Intelligence, global terrorism and higher education. British Journal of Educational Studies, 64, 1, pp. 37–51.

- Sandler, T. (2011), New frontiers of terrorism research. Journal of Peace Research, 48, 3, pp. 279–286.

- Sedgwick, M. (2010), The concept of radicalization as a source of confusion. Terrorism and Political Violence, 22, 4, pp. 479–494.

- Spaaij, R. (2012), Understanding Lone Wolf Terrorism (Springer).

- Sukarieh, M. and Tannock, S. (2016), The deradicalization of education. Race and Class, 57, 4, pp. 22–38.

- Tsfati, Y. and Weimann, G. (2002), http://www.terrorism.com:terrorontheinternet. Studies in Conflict and Terrorism, 25, 5, pp. 317–332.

- Tucker, D. (2001), What is new about the new terrorism and how dangerous is it? Terrorism and Political Violence, 13, 3, pp. 1–14.

- Waldman, P. and Pope, H. (2001), ‘Crusade’ reference reinforces fears war on terrorism is against Muslims. Wall Street Journal (21 September).

- Weber, E. P. and Khademian, A. M. (2008), Wicked problems, knowledge challenges, and collaborative capacity builders in network settings. Public Administration Review, 68, 2, pp. 334–349.