IMPACT

This article contributes to the debate about audit independence by providing insight into the different phases of the audit process and how and why audit activities are subject to influence from different interests. This insight can be used by regulators who are interested in developing policies to improve audit quality.

ABSTRACT

This article reports on an investigation of audit independence in the context of local public audit in Sweden. The article focuses on the influence of two different sets of interests. The results show that there is a risk that the way the results of the audit process are communicated and disseminated in an organization is influenced by political, as well as market, interests. The article reveals the complexity of the public sector audit process and sheds light on the difficulty of securing audit independence and decreasing the audit expectation gap. This article provides valuable insight for researchers, practitioners, and policy developers.

Introduction

The focus of this article is local public audit (LPA) in Sweden, responding to the call for more empirical research into LPA for policy development (Grace & Thorogood, Citation2021; Manes Rossi et al., Citation2021; Martin et al., Citation2013; Mattei et al., Citation2020) and to increase our understanding of audit independence (Mattei et al., Citation2020; Hay & Cordery, Citation2021; Pontones Rosa & Perez Morote, Citation2016).

In contrast with many other countries, the Swedish LPA system includes politically-appointed auditors, as well as private sector auditors (Manes Rossi et al., Citation2021; Collin et al., Citation2014). Studying the Swedish LPA process therefore enables influences from the market, as well as political interests, to be identified. This article contributes to understanding audit independence by revealing:

The influence of market and political interests on the audit process.

The potential effect of the influence of market and political interests on audit quality and audit expectation.

This study thus contributes to our understanding of audit independence and why it has remained a important topic of interest for over a century (Humphrey et al., Citation1992).

Research context and method

The Swedish context and institutional features of LPA in Sweden

The Municipal Act (SFS Citation1991, p. 900) regulates how local governments operate in Sweden. According to this Act, Swedish municipalities enjoy a large degree of autonomy and discretionary power. This includes the appointment of auditors. Auditors are nominated by and selected from the political parties that hold seats in the municipal council—so the appointed auditors are laypeople. The Municipal Act therefore stipulates that a professional auditor must assist these politically-appointed auditors. Although a municipality can procure these services from a private sector auditing firm or use an in-house solution, most Swedish municipalities chose external auditing firms. The politically-appointed auditors hold the primary responsibility for the audit process, and they are the people who sign off on the audit report (Municipal Act, Chapter 9 §9–11 and §16). The political auditors are also responsible for writing an audit statement and making recommendations to the municipal council on how the council should respond to result(s) of the audit (Municipal Act, Chapter 9 §9–11 and §16).

Given the extent to which politically-appointed auditors are involved in the audit process, it is not surprising that the question of how they are able to secure audit independence surfaces from time to time in Sweden. This question is raised by both researchers (Thomasson, Citation2018; Tagesson & Eriksson, Citation2011) and practitioners, including the former head of the Swedish National Audit Office (Ahlenius, Citation2017). The criticism that is levelled against the Swedish LPA process bears several similarities with issues addressed in the academic literature on ‘audit independence’ (Everett & Tremblay, Citation2014; Kells, Citation2011; Roussy, Citation2013).

Research methodology

To investigate how the influence from political, as well as market, interests on the Swedish LPA process is perceived by the auditors themselves, a survey was send to the chairpersons of local audit committees. The survey was developed out of a research project focusing on the politicization of the Swedish LPA process conducted in 2017, as well as a literature review of previous research on LPA in Sweden and other countries. An online questionnaire was used for the survey. The questionnaire was tested on one experienced local politician and current head of the audit committee in a Swedish municipality before it was sent out to the respondents in autumn 2021. One reminder was sent out two weeks after the survey was first distributed. The respondents were assured that their identities would be kept confidential.

Results

Out of the total of 290 Swedish municipalities, 279 participated in the study. The reason why 11 municipalities were not included in the study is that no contact information could be found for the chairperson of those municipalities’ audit committees. Of the 279 audit committees included in the study, 202 responded to the survey—giving a response rate of 72%.

Factors influencing scale and scope of LPA in Sweden

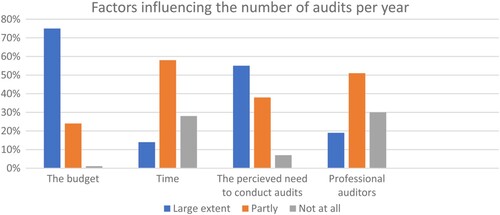

When asked about what determines the number of audits conducted during a year, 75% of the auditors reported that the budget was the primary determining factor (see ). In Sweden, the budget for the audit committee is set by the chairperson of the municipal council, which means that political priorities determine the extent to which municipal boards and committees are audited. By controlling the budget, the chairperson has the potential to influence the LPA process.

In addition to budget constraints, time was considered a relevant factor regarding whether an audit is performed or not. As many as 58% of the auditors responded that time was a factor that partly influenced the number of audits that they conducted. The availability of time and financial resources are likely to be mutually connected because political auditors need support from professional auditors to do their job. The lower the budget, the fewer professional services can be procured. The size of the budget can thus influence overall audit quality. This relationship between audit quality and the budget is also recognized by among others Ellwood and Garcia-Lacalle (Citation2012) as well as Cearns (Citation2012). On the positive side, 55% of respondents stated that it was the need, rather than budget and time, that influenced the number of audits a committee decided to perform.

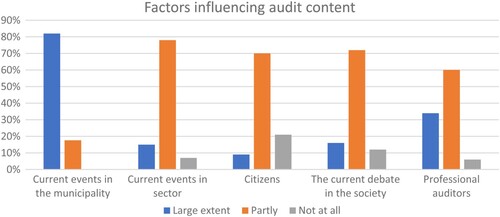

Influencing the scope of the LPA process is the decision regarding which areas of a municipality’s operations will be audited in collaboration with the professional auditors. Regarding which areas should be audited, 60% of the auditors stated that the professional auditors partly influenced this decision (see ). According to Knechel et al. (Citation2020), accounting firms are incentivized to standardize parts of the audit process since such standardization allows for an economy of scale (Knechel et al., Citation2020). For an accounting firm, auditing the same areas across several municipalities could be one way to optimize the firm’s processes and reduce costs. With the influence from professional auditors over content of the audit process, there is thus a risk that local needs and priorities are not considered—something that, according to Downe et al. (Citation2008), could increase the audit expectation gap. There is thus a risk that the market for audit services influence the scope of the LPA process in Sweden.

It is, however, not only market interest that potentially influence the LPA process in Sweden. Note that political auditors are also politicians and members of political parties. Therefore, it is likely that they are influenced by political interests. That the audit process is politicized in Sweden is stressed in an earlier article—see Thomasson (Citation2018). The process of selecting specific areas of a municipality’s operations for audit may thus be influenced by the effects of marketization, as well as by political interests.

The perceived role of politically appointed auditors

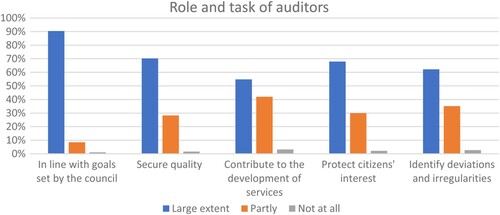

According to the Swedish Municipal Act, auditors work for the municipal council and are tasked with ensuring that the relevant committees and boards comply with the decisions made by the council. When these auditors were asked about what they considered to be the role and task of the political auditors, 90% of them responded that they believed that the political auditors were responsible for ensuring that decisions made by committees and boards were in line with the goals set by the municipal council (see ). A majority (62%) of the auditors also considered that it was their job to look for any inconsistencies and signs of violations of rules and regulations, and 55% of the respondents also thought that their role was to contribute to the development of service provision (see ).

These responses are perhaps not surprising giving that they accurately reflect how the role of the municipal auditor is described in the Municipal Act. It is, however, interesting that 70% of the auditors also considered that they were responsible for securing the overall quality of service provision (see ). This finding is in line with other studies showing how LPA is increasingly focusing focus on performance audit (Mattei et al., Citation2020).

Perceived outcome of audit process

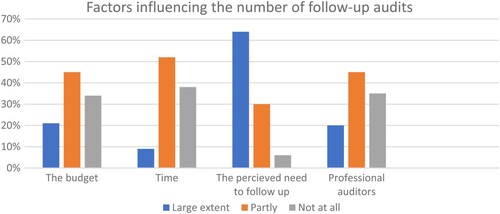

Turning to the perceived outcome of the audit process, 70% of the auditors reported that they follow up on audits to evaluate how the board or commission that was subject to an audit responded to it. According to the respondents, the main reason why they do follow-up audits is because of a perceived need to do so (see ).

Like regular audits, follow-up audits require resources: 45% of respondents stated that the budget was a factor that influenced the extent and scope of follow-up audits, while the corresponding figure for time (as a factor) was 52%. Clearly this phase of the audit process carries a potential risk for political influence on the audit process and the quality of the process.

However, risks are not confined to political influence—professional audits exert influence over the scale and scope of follow-up audits and perhaps even more so than political interests. Twenty per cent of respondents stated that the professional auditors influenced the extent and scope of follow-up audits to a large degree, and an additional 45% said that they partly influenced this decision (see ). Consequently, the outcome of the audit process and, hence, the overall quality of that outcome, runs the risk of being influenced by political interests, as well as the partial marketization of the audit process.

Not only is there a risk of the outcome of the audit process being influenced by various interests, the results from the survey also show that the interest in audit reports tend to be low among council members. As many as 67% of respondents reported that they perceived that their councils were only partly interested in the information provided in the reports. In addition, 54% of respondents claimed that the outcome of the audit process only partly influenced the development of organizational processes.

The present study reveals how the members of the council have limited interest in audits even though the auditors can be said to be the ‘eyes and ears’ of the council. This lack of interest is likely to have ramifications for how an organization perceives and receives audits and how likely it is that audits will affect the status of politically-elected auditors. This study supports previous research on how politicians can influence the audit process (Nickell & Roberts, Citation2014; Thomasson, Citation2018; Kells, Citation2011; Hay & Cordery, Citation2021). This study also shows how the outcome of the audit process might be influenced by professional auditors who are exposed to market interests. Previous research on the marketization of the audit process has focused more on how marketization influences the market for audits and less on the influence on audit outcome. This article highlights the need to examine the influence of marketization on the outcome of the audit process.

Discussion and conclusions

This article has focused on the LPA process in Sweden. In contrast with many other countries, the Swedish LPA system includes politically-appointed auditors as well as private sector auditors (Manes Rossi et al., Citation2021; Collin et al., Citation2014). Studying the Swedish LPA process therefore enabled influences from the market to be identified, as well as political interests.

Audit independence has been shown to be jeopardized by influence from both political interests, as well as market interests. While previous research has focused on the effects of marketization (Cearns, Citation2012; Ellwood & Garcia-Lacalle, Citation2012) or politicization (Hay & Cordery, Citation2021; Kells, Citation2011; Nickell & Roberts, Citation2014), this study shows that every part of the audit process is exposed to (potential) influence from either market or political interests or a combination of the two. Consequently, this study not only confirms the findings of these previous studies, but it also contributes to our existing knowledge on the topic by providing insight into how different interests has the potential to influence the different parts of the audit process.

The need to include the whole audit process in an analysis of audit independence has been identified by Funnell et al. (Citation2016) (among others), but (to the best of my knowledge), the audit process and its different phases have not been comprehensively described or analysed before. More research on the audit process in different institutional contexts is thus called for.

The article illustrates how a municipal council influences the communication and dissemination of audit reports. Given the structure of the Swedish LPA system, political influence over the post-audit phase is clearly a significant risk. This study thus supports findings by Nickell and Roberts (Citation2014) and Thomasson (Citation2018), who identify the risk where politicians use audits to achieve political goals. Kells (Citation2011) emphasizes this point by claiming that the audit process runs the risk of becoming a hollow ritual (see also Power, Citation1997). Although this article does not provide any specific evidence that the audit process is a hollow ritual (Kells, Citation2011), it shows that the risk of this happening is extensive.

Even though the Swedish LPA process is of interest (given how it combines market influences with political influences), it is also unique in many ways. Nevertheless, the findings of this study have some significant research implications—not only for future research but also for policy development. From a policy viewpoint, this article provides information regarding how different actors influence the audit process and how market interests and political interests can influence the audit process. This information may be relevant to the re-design of existing audit systems and for policy development. My call for further research in these specific areas is echoed by Manes Rossi et al. (Citation2021) and Grace and Thorogood (Citation2021).

References

- Ahlenius, I.-B. (2017). Kommunerna behöver oberoende revision (The municipalities need an independent audit), Göteborgs Posten. https://www.gp.se/debatt/kommunerna-behöver-oberoende-revision-1.4167028.

- Cearns, K. (2012). Debate: Local public audit—comparison with the private sector. Public Money & Management, 32(6), 396–397.

- Collin, S.-O., Haraldsson, M., Tagesson, T., & Blank, V. (2014). Explaining municipal audit cost in Sweden: Reconsidering the political environment, the municipal organization and the audit market. Financial Accountability & Management, 33, 391–405.

- Downe, J., Grace, C., Martin, S., & Nutley, S. (2008). Best value audits in Scotland: Winning without scoring. Public Money & Management, 28(2), 77–84.

- Ellwood, S., & Garcia-Lacalle, J. (2012). New development: Local public audit – the changing landscape. Public Money & Management, 32(5), 389–392.

- Everett, J., & Tremblay, M.-S. (2014). Ethics and internal audit: Moral will and moral skill in a heteronomous field. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 25, 181–196.

- Funnell, W., Wade, M., & Jupe, R. (2016). Stakeholder perceptions of performance audit credibility. Accounting and Business Research, 46, 601–619.

- Grace, C., & Thorogood, T. (2021). Debate: Local public audit and accountability—an international and public value perspective. Public Money & Management, 41(8), 582–583.

- Hay, D., & Cordery, C. J. (2021). Evidence about the value of financial statement audit in the public sector. Public Money & Management, 41(4), 304–314.

- Humphrey, C., Moizer, P., & Turley, S. (1992). The audit expectation gap – plus ca change, plus c’est la meme chose? Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 3, 137–161.

- Kells, S. (2011). The seven deadly sins of performance auditing: Implications for monitoring public audit institutions. Australian Accounting Review, 21, 383–396.

- Knechel, W. R., Thomas, E., & Driskill, M. (2020). Understanding financial auditing from a service perspective. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 81, 1–23.

- Manes Rossi, F., Brusca, I., & Condor, V. (2021). In the pursuit of harmonisation: Comparing the audit systems of European local governments. Public Money & Management, 41(8), 604–614.

- Martin, S., Downe, J., Grace, C., & Nutley, S. (2013). New development: All change? Performance assessment regimes in UK local government. Public Money & Management, 33(4), 277–280.

- Mattei, G., Grossi, G., & Guthrie, J. A. M. (2020). Exploring past, present and future trends in public sector auditing research: A literature review. Meditari Accounting Research, 29(7), 94–134.

- Municipal Act, SFS 1991:900, Kommunallagen. Kommunallag (2017:725) Svensk författningssamling 2017:2017:725 t.o.m. SFS 2022:638 - Riksdagen

- Nickell, B. E., & Roberts, R. W. (2014). Organizational legitimacy, conflict and hypocrisy: An alternative view of the role of internal auditing. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 25, 217–221.

- Pontones Rosa, C., & Perez Morote, R. (2016). The audit report as an instrument for accountability in local governments: A proposal for Spanish municipalities. International Review of Administrative Science, 82(3), 536–588.

- Power, M. (1997). The audit society: rituals of verification. Oxford University Press.

- Roussy, M. (2013). Internal auditors’ roles: From watchdogs to helpers and protectors of the top manager. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 24, 550–571.

- Tagesson, T., & Eriksson, O. (2011). What do auditors do? Obviously, they do not scrutinise the accounting and reporting. Financial Accountability & Management, 27(3), 272–285.

- Thomasson, A. (2018). Politicization of the audit process: The case of politically affiliated auditors in Swedish local governments. Financial Accountability & Management, 34(4), 1–12.