The idea that public auditors create value for the public, and through their work further the public interest and deliver public goods, is widely acknowledged. There is self-evident public value in holding public bodies to account for the accuracy of their financial statements and the regularity of their core processes. In the UK and in many other jurisdictions, the scale and character of public expenditure at local level makes local public audit (LPA) a significant and major part of public audit as a whole. Along with the many major individual entities to be audited at the local level, there are issues of partnership and synergy between public bodies for auditors to consider. In terms of central/local relationships, the delivery of national objectives through local bodies is clearly growing in importance. That, too, is a potential topic for local public auditors.

There is also a wider canvass in the increasing realization among policy-makers at the centre that greater devolution and local accountability is a necessary, if not sufficient, condition to tackle many of the ‘wicked problems’ which continue to bedevil UK society. That is, in part, what provides the underlying impulse towards regional/metropolitan mayors—a policy which is now established orthodoxy across the political spectrum. Devolution has not yet gone far enough, and one of the limits to it is the concern at the centre that local accountability is too frail and vulnerable to be an adequate check. LPA—re-imagined and refreshed—could provide the instrument to confer the essential confidence needed to extend devolution that much further.

Why public value?

But why make public value the focus of this Public Money & Management (PMM) theme on LPA? The first reason is that LPA does not only deliver public value through its role and activities. If it is done well, it also impacts positively on the public value delivered by the audited bodies themselves—they can do things better and differently because they have been assessed and explored against demanding and transparent standards, and have found that there are lessons to learn. This both direct and indirect effect is an extra public value dividend, and an amplifier. By not only holding local public bodies to account, but also helping them to improve, public value is generated both directly and also through the changes, the better services, and the greater value for money that results.

Second, the potential for LPA to generate public value remains vastly unrealized in many jurisdictions across the world. There has been development, including the spread and growth of performance audit, which is a key instrument in the audit creation of public value. But the range and depth of the potential value creation is largely untapped.

Third, to realize that value calls for a modern vision for LPA which is focused on how it can optimize the public value it can create for all the many stakeholders who stand to benefit—the entities themselves, citizens and communities, and national governments.

Finally, both authors share the vision of Cardiff Business School to be a ‘public value’ business school, and to explore what it means to consider instruments of business and government like audit from a public value perspective.

This PMM theme is geared to articulating that vision. The articles and debate pieces in this issue provide a rich set of perspectives and insights on LPA in the UK and internationally. Between them, they inform a future vision for LPA which all stakeholders can adopt and benefit from. We introduce all that material in this editorial, starting with a fuller explanation of what public value means, and relating that to the writings in the body of this issue and drawing out what the vision might mean in practical and policy terms.

The impulse for this PMM theme originated in a conversation some years ago at the House of Lords with Michael Bichard. He stood on common ground with one of the authors in recognizing the distressing fragmentation of the English LPA system since 2015, but knew that at that time (which was pre even the Kingman Report) there was not sufficient public or political concern about LPA to underpin a force for change. That situation has been transformed both by the fascination of the horror of the train crash of LPA in England, and by the authoritative reviews which have focused attention—principally, of course, that by Redmond (Citation2020). Fittingly, a PMM Live! event at the House of Lords in November 2022 was both an opportunity to initiate that debate, and also to stimulate additional contributions to this issue, which was then in preparation.

At that event, and in this issue, the focus was on local government. The audit of local health bodies in England is, however, also of deep current concern. A re-imagining of LPA would have benefit for health and, indeed, for many ‘special purpose’ public/mixed sector bodies such as multi-academy education trusts and housing associations, as well as for local government.

What is public value?

Public value has been summarized as both ‘the next big thing for governments aiming to deliver quality public services’ and ‘elusive and devoid of clarity’ (Bojang, Citation2021).

The concept of public value stretches back to an original formulation by Moore in the notion that public sector managers create value for the public in contrast to the theory of shareholder value whereby private sector managers seek to maximize shareholder wealth (Moore, Citation1995). Widely recognized as encapsulated by the ‘strategic triangle, it encompassed three elements of goal and outcome setting (what constitutes public value), decision-making processes (how what constitutes public value is to be agreed by citizens, political leaders and managers) and operational capability to deliver outcomes in line with what has been agreed. According to Moore, these all need to align to create public value.

From its inception, public value was contrasted with New Public Management (NPM); providing a citizen centric and relational definition of public services compared to the consumerist and market orientation of NPM. Since then, the concept has continued to develop as researchers and theorists examine and emphasize different aspects. Something of a dichotomy developed between those like Moore emphasizing managerialist perspectives (how should organizations practically approach the creation of public value?) and others, such as Bozeman (Citation2007), emphasizing achieving a normative consensus about the rights and obligations of citizens and the principles of government—a public value perspective. More recently, scholars have developed broad frameworks encompassing such varied perspectives and allowing for the complex nature of contemporary governance (for example Witesman, Citation2016; Bryson et al., Citation2017).

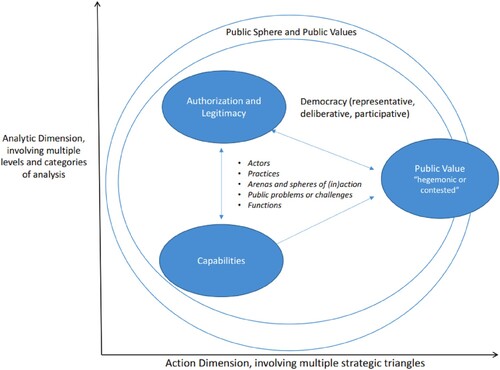

Bryson et al. (Citation2017) propose a broader and more complex strategic triangle adapted explicitly ‘to the new multi-actor, multi-sector, shared power world’ which neatly encapsulates how broad and complex the concept, and its related agenda for research, has become; see .

Figure 1. Adapting the strategic triangle more explicitly to a multi-actor, shared-power world (Bryson et al., Citation2017).

In this issue, Murphy et al. (Citation2023) simply suggest:

Public value is now often understood as more of an umbrella term that encompasses ideas of furthering the public interest and maintaining the delivery of public goods … [a] broader interpretation of public value as a principle that seeks the maintenance and furtherance of public goods and the public interest.

Applying a public value perspective to LPA

A public value perspective on LPA is one requiring a wide scope. If public value is ‘what the public values’ (Benington & Moore, Citation2010) and if this is defined through typically complex interactions between multiple stakeholders encapsulated by Bryson’s triangle (Bryson et al., Citation2017), then the varied and constantly varying definitions imply a potentially broad scope for LPA in assuring stakeholders that public resources are being well used.

Alongside this is the impulse which LPA can give to local public bodies—not merely to deliver public value in the accuracy of their financial statements and their regularity compliance, and to be accountable to their communities for all that. LPA can go beyond that to test value for money and the effective performance of service delivery. Beyond that again, LPA can stimulate the changes which all public bodies constantly need to make in a rapidly changing world if they are to do their very best for those they serve.

The implications of a public value approach to LPA are therefore that the scope of audit should be broad, the process of audit should be geared to the nature of local public bodies and the character of the communities they serve, and the communication of audit outcomes should be intelligible and usable by communities and citizens, as well as by the organizations themselves and by government.

Performance management is integral to the notion of public value—as a basis for strategic management it was central to Moore’s original proposition (Moore, Citation1995). However, research studying performance management and public value has been limited (Höglund et al., Citation2021). Reviewing research literature associating public value and accountability in this issue, Dallagnol et al. (Citation2022) found just 22 articles published since 2009 which were divided by two lines of thought (nine being based on Moore’s framework and eight on Bozeman’s), suggesting that better understanding of the association between these might help the future development of audit from a public value perspective. Central to their conclusions is that the measurement of public value emerges as a little researched area leading the authors to conclude:

Future studies should focus on investigating public value measurement as a way to support more effective accountability processes in the public management context, mainly through Public Audits, either by addressing accountability as means to create public value or as public value per se … Empirical approaches implemented in local governments appear to be particularly welcome.

Perspectives and insights of this PMM theme

LPA has been a developing theme and activity in many jurisdictions across the world. Increasing numbers of countries have established LPA structures and arrangements and, as a general rule, those jurisdictions have tended to embed LPA in the wider national-level public audit function. Beyond that, the tendency to shape LPA to the particular character of local public institutions has been visible, and captured in academic analysis in terms of, for example, the growing interest in performance audit (Ferry et al., Citation2022).

These developments have no doubt had their setbacks and false starts, especially in developing jurisdictions. However, the overall trajectory appears to have been relatively linear—the emergence of LPA as a vital and growing component alongside the audit of central public bodies, then growing further alongside the increasing importance of local government in public expenditure terms, and then extending its scope as the public interest in local government expenditure moves beyond anti-corruption and regularity into broader issues of performance and value for money.

It has therefore been a matter of global significance that LPA in England appears to many observers to have gone backwards by abolishing a powerful (some said over-powerful) body (the Audit Commission) for LPA and thereafter abandoning a publicly-employed workforce to deliver LPA, and also limiting its scope. For such a major and historically important jurisdiction for LPA to reverse direction in such a dramatic and purposeful manner inevitably raised the question as to whether LPA had perhaps been going too far and too fast in a direction that was neither appropriate nor sustainable.

The Audit Commission is a matter of history, and it will not detain us here as an institutional form (although its functions warrant analysis as part of a future vision for LPA). The deeper question is whether this reverse in public policy in England represents a long-term international shift in the role and function of LPA. Beyond that, are there wider lessons from UK and international experience to enable LPA to realize its optimum contribution to public value?

The contributors to this issue illustrate a number of these wider questions. First is the crisis in England’s system of LPA, and understanding the roots of and possible mitigations to that crisis, as well as more radical solutions that may be accessible. Beyond that, critically, is wider international experience, including the overall trends in LPA, and the attendant implications for auditor education and training. Between them they can help fashion a new and compelling vision for LPA in the UK and internationally.

The crisis in England’s system of LPA

The problems facing LPA in England were tellingly documented in Redmond’s excellent review, and his reflections in this issue (Redmond, Citation2023) are that progress has been made in some respects since he reported. He considers that LPA ‘plays an important role in delivering public value’ but that, in practice, the extent and nature of LPA at present ‘does not always cover the public value areas in a comprehensive way’. The English LPA focus is on compliance with statutory requirements. This leaves room to extend LPA, weighed against the additional resources and cost required to do so. The right balance ‘would be greatly assisted by a local authority having a structured approach to public value’. He also points up the importance of audit governance, and the need ‘to introduce minimum standards in respect of how local authorities at member and officer level manage the relationship with local audit’. This highlights the issue of what local authorities really want from their LPA, and this too will be a crucial consideration in fashioning a new vision.

One of the key innovations of the new LPA regime in England was the creation of an independent body, but one lodged firmly within the local government family, to enable the collective procurement of external audit in England, alongside the right of individual authorities to appoint their own auditors. Public Sector Audit Appointments Ltd (PSAA—of which one of the authors was a founding director) has been responsible for two major rounds of external audit procurement, all from the private sector. Its chair, Steve Freer, has contributed two pieces to this issue.

The first (Freer, Citation2022), submitted during the most recent procurement round, articulates the concerns which all stakeholders have about England’s LPA market, and the consequences of the problems it faces. In the face of the fragmentation attendant on the post-2014 arrangements, many have repeatedly highlighted the need to identify a ‘system leader’ with the authority and resources to spot issues and build collaboration to construct and deliver solutions. Freer echoes that imperative, while also highlighting the critical need for ‘supply capacity so that the appointment of capable, competent auditors is assured for all local bodies’. The structure of the private audit market and the unique requirements of LPA mean that this will be no small task. He suggests that the ‘development of a public sector-owned local audit supplier to help support the market is a possible way forward’. After all, there has been no LPA crisis in either Wales or Scotland, both of which have a public sector LPA workforce available as an auditor of last resort, as well as delivering a substantial proportion of audits themselves.

Freer’s second piece reports on the results of PSAA’s procurement exercise, having successfully attracted bidders to cover all audits, but at a cost of a 150% increase in fees, and with the state of the local audit market continuing to be a ‘critical concern’, and with only 12% of local authorities meeting the deadline for 2021/22 audits (Freer, Citation2023). He envisages a ‘few years’ of concerted effort to get England’s LPA on to a stable and sustainable footing.

The effects of systemic problems in England’s LPA has been to compromise the public value which LPA can create. Bradley et al. (Citation2022) document the fragmentation which has flowed from the 2014 legislation, and also draw out some of the key themes in the evidence to the Redmond Review, along with the government’s response. They show that beneath some hubristic and unconvincing rhetoric of the government’s response to Redmond’s pleas for system leadership (which somewhat bizarrely focused on not re-creating the Audit Commission), the government accepted all the major parts of his (highly critical) analysis of the effects of their flagship LPA reforms of just a few years before.

The thrusts of those reforms, and their underlying ideological impulse, was to treat LPA as essentially a minor branch of private, corporate audit. There is an overlap with private corporate reporting, as is well understood, and Bradley et al. (Citation2022) document that clearly. But the differences are as if not more important because the wider scope of LPA ‘plays a fundamental role in securing accountability to a greater range of stakeholders’. They apply a theoretical framework to situate the issues of audit quality, the regulatory correlates of LPA, and the sustainability of the LPA market. Surface audit failures and weaknesses have deeper roots, in their analysis. The key issue is whether the changes embraced by government are up to the task of addressing those underlying issues.

Health

The avalanche of attention to the failures of England’s LPA system in local government have left many wondering about whether the position in health has been any better. For health, as for local government, the Local Audit and Accountability Act 2014 required England’s local NHS bodies to procure and appoint their own auditors, with Wales and Scotland continuing with their own arrangements through their respective auditors-general.

The Healthcare Financial Management Association conducted two surveys to help assess the state of England’s NHS audit market (HFMA, Citation2021; Citation2022), with results as equally worrying and with similar features to the position in local government. Many of the (60 for their 2021 report and 61 for 2022) respondents in 2021 were finding it difficult to appoint an external auditor, with little or no interest being shown in invitations to tender. They discovered problems of low audit fees but this was ‘combined with NHS organizations seemingly uninterested in their auditor’s work indicating that public sector audit has become commoditised and is not valued’ (HFMA, Citation2021). The scale and character of the issues were such that they saw a need for ‘concerted, co-ordinated effort at a national and local level’ (HFMA, Citation2021). By 2022, the position had worsened, with a risk that some of England’s local NHS bodies might not even be able to appoint an external auditor, and with deepening problems of rising fees and a fragile audit market (HFMA, Citation2022; see also Robertson, Citation2023).

Here again the contrast between England with Scotland and Wales is stark, not only in terms of auditor supply (there were no comparable supply problems in either of those jurisdictions), but also scope. As is increasingly recognized, major local health bodies can do much more than respond to illness, and even in that fundamental role they are part of the local public services ecosystem and need to be fully joined up with social care and with public health, in particular. England’s LPA for health bodies does not have such a focus. In Scotland and Wales such connections are routine.

The audit profession

Many of our contributors highlight not only the frontline issue of audit supply and capacity, but also the underlying problems in the audit profession. Broadbent (Citation2022) puts her finger on the irony that ‘the louder the voices calling for ensuring value-for-money and maintaining accountability, the more government policy-makers and we, as a society, seem to ignore and downgrade one of the main tools available to us in ensuring these outcomes’. Her plea is for higher education to engage students with the ‘importance and interest of auditing’ and to help them understand its vital importance in adding public value by informing the resolution of the critical issues facing our society.

Baylis and De Widt (Citation2022) also highlight how the manifold changes to LPA in England have created a skills gap and increasing difficulty to employ appropriately trained and skilled staff, to a degree which seems unlikely to be filled by current plans. Hence thought must be given to new initiatives such as audit firms collaborating to share expertise and training centres, and universities developing public sector audit training using innovative course designs. They pose an important challenge to the sector, including audit firms and universities, to ensure LPA quality. The viability of LPA is already at stake even on existing requirements. Our call to re-orient it towards optimizing public value would enlarge the workforce gap substantially, and the corresponding challenge of how to fill it.

This is a theme explored by Caperchione (Citation2023) in recognizing that if the public really wants the use of public resources and the performance of public institutions to be evaluated, then the focus on public value must come to the ‘centre of the scene’. He argues for a renewal of the audit profession, in effect a new audit profession, which could be capable of performing a wider and modern role to include the capacity and talents to inform issues as significant as climate change and contribution to the SDGs. Caperchione goes on to set out what amounts to a compelling manifesto for that renewal, including a significant focus on the role of education and training.

It is important to recognize that more than 80% of countries conduct public audit through a single authority, and have a public audit workforce. So the changes required in the culture, skills and orientation of the audit workforce will impact a profession anchored in both the private and a public sectors. This emerges from survey of 125 Supreme Audit Institutions for the XXIV International Congress of Supreme Audit Institutions in 2022, as reported by Hamid (Citation2023), who also points us towards some emerging possibilities in the field of public audit.

What is to be done?

The contrast between England, on the one hand, and Scotland and Wales on the other, has been a strengthening theme in the LPA debate as the crisis in England persists while the other two nations have been immunized from the effects of market failure by a (relatively) substantial public sector LPA workforce, employed by their respective national audit bodies under the direction of their auditors-general. In both nations these officials oversee both local and national audit, including health as well as local government. The UK Comptroller and Auditor General (C&AG) highlights the contrasting fortunes of LPA across the UK (Davies, Citation2022), but expresses caution at any notion of replicating a comprehensive approach for England. He points up both constitutional and practical problems, albeit (rightly) without saying that they are unresolvable. (Interestingly, most Supreme Audit Institutions in other countries than the UK appear to take those problems in their stride.) Instead, he advocates clear and effective system leadership, clearing the audit backlog, and consideration (as per Freer) of a public sector owned local audit supplier to supplement the private market to conduct, perhaps, 20% of England’s LPA, and to provide an auditor of last resort.

It is the citizen stakeholder in LPA who should be at the heart of the enterprise for Murphie and Fright (Citation2023), but the chance to make that so has been lost: ‘rather than resetting the relationship between an authority and its citizens … accounting, auditing and statistics have become a means of mediating between central and local government’. They lost the plot, and part of the way forward is to achieve re-connection between citizens and what could be one of the principal instruments for them to exercise effective accountability.

For Murray (Citation2023), the way forward calls for consideration of the broader issues of corporate reporting such as have been set out by the European Commission. These might inform ways in which LPA could be ‘repurposed’. The LPA role in value for money, and in assuring sustainability reporting, presents just such an opportunity, as long as there is ‘an honest conversation about how better to align for corporate governance, statutory audit and regulation’.

Walker (Citation2023) also sees the need for audit to ‘reinvent’ itself. His is a more challenging and radical vision, rooted in a strong sense that audit should be a critical part of broader democratic renewal. He proposes a new architecture through which audit scope would expand to consider how spending contributes to equity, equality and sustainability. Although he does not draw the comparison, this latter purpose is already assigned to LPA in Wales. As we shall see shortly, Wales and Scotland have not only avoided a crisis in LPA. They have also pushed out its boundaries and harnessed it to assessing progress in achieving fundamental and long-term national goals.

International insights and lessons

The first lesson from international insights is that for all its operational and ethical independence, and its reliance on global standards, audit is not best understood as if it were an isolated and self-contained set of activities, or immune from isomorphic forces. Across 20 countries, all four dimensions of ‘audit regulatory space’—organization and fragmentation; independence and competition; scope; and performance assessment/inspection— are informed both by the constitutional framework of each country (such as the degree of centralization) and the ideological trends around audit itself (Ferry et al., Citation2022).

These trends include theories of the modern state, and in particular the argument that the development of the neoliberal state has led to an increased focus on both financial and performance audit. Performance auditing is undertaken for local governments by 11 states, with another four producing performance statistics as part of the process of LPA, plus another, Italy, providing such information via an independent evaluation office—a total of 16 from 20 states. England, arguably originally having the most performance orientated LPAs, is now identified alongside China as engaging in only a ‘limited performance audit’ (Portugal and Sweden having no type of performance assessment). Ferry et al. (Citation2022) conclude that the increasing role of performance audit is a constant across all sorts of audit regime. This ‘confirms the growing stature of performance audit as a fundamental part of local government audit practice’. From an international perspective, therefore, the public value of LPA has been increasing. Indeed, it is only in England that this has reduced.

The growth of internal audit at the local level has also been a developing trend. Langella et al. (Citation2022) examine the process of internal audit development in three Italian health regions. The three regions encompassed centralized, devolved and hybrid models of health care management. Despite isomorphic pressures resulting from national legislation, professional associations, and a desire to mimic, internal audit developed differences of approach in each region which can be explained by their different power structures. While comparisons with external audit in other jurisdictions must be cautious, the authors show that national and regional structure matters in how national audit requirements are practised at local level. The relevance to the variations in LPA found across the UK is clear. It suggests that detailed comparison of such ‘models relating isomorphic and organizational factors would be a valuable research area in understanding the role of audit in achieving public value’.

Isomorphic pressures are also at work in the adoption of audit standards as a core feature of LPA. Rönkkö et al. (Citation2022) looked at the deployment of audit standards across local governments in Finland. Despite no official requirement to do so and, indeed, some contrary pressures resulting from Finland’s competitive municipal audit market, 70% of responding chartered public finance auditors applied International Standards on Auditing (ISAs) when auditing municipalities. Isomorphic pressures resulting from the Audit Oversight Board and other stakeholders encouraged the use of ISAs, and overcame the contrary pressures.

While the use of ISAs speaks to the neutral and technical aspects of LPA, Thomasson (Citation2022) reveals how political and market influences also play their part in the audit of Swedish municipalities. Their auditors are nominated and selected from the political parties that hold seats in the municipal council, assisted by professional auditors mostly from private sector firms. Her survey shows that both political and market factors may influence the scale, scope, purpose and outcomes of LPAs, resulting from the involvement of both political parties and private sector firms, and jeopardizing audit independence. The potential policy implications for audit regimes, such as that in England, where local bodies appoint their own auditors from the private sector, and politicians populate local authority audit committees, are obvious, and suggest this as a key research area.

Potential political influences also emerge Jorge et al.’s analysis (Citation2022) of structures and practices in Portugal. It explains the paradoxes that exist for local public auditors whose role is to certify for assurance and fair presentation but who are in practice used for political gains particularly where politics is intense. Linking these points to Thomasson’s (Citation2022) research further highlights the possible consequences where local politicians may have influence over audit processes and outcomes as in Sweden and in the UK.

Conclusion: Re-imagining LPA through a public value perspective

The insights of the contributors to this PMM theme are the raw material through which to fashion an international vision for LPA. England, in particular, badly needs one which can transcend the sterile re-hashing of old sores, and also the important but perhaps inevitably cautious steps being taken since Redmond reported. A new vision should show how LPA can play an active and vital part in achieving excellence in public service and governance, as well as being a force for accountability and propriety.

We can be sure that England is no longer a beacon. Let us be frank—the state of LPA in England is as shocking and embarrassing as some other aspects of UK governance. The government’s hubristic adventure in radical change has brought the system to the point of collapse. England’s LPA system was deliberately fragmented in both its delivery and functions, and disconnected from any wider approach to public service improvement. It has been fashioned as a public sector adjunct to ‘mainstream’ private audit. Its scope is not very far beyond that of private sector audit in comparison with many other jurisdictions, including developing ones. It uses a workforce of private sector auditors, with appointments made potentially by the audited bodies themselves, and oversight by a body dealing mainly with private sector audit. This situation has been partly moderated through the role of the Local Government Association and PSAA in maintaining a collective approach to audit appointments, and also through the C&AG in broadening somewhat the scope of LPA in England. But the consequences for LPA have still been dire, with an emerging crisis of supply which has been resolved only through an enormous increase in fees, and a huge backlog of late, and very late, audit opinions for English local authorities.

Our new vision has several components. We need to remind ourselves of what we have lost, and highlight examples of what it might look like, and then to see LPA as a ‘whole system’ itself and also as a key contributor to the wider system of public service improvement. Maximizing public value from LPA will require attention to the needs of its three principal stakeholders, and to the essential purpose, scope and functions of LPA in the modern world.

What have we lost?

It is said that those who forget the lessons of history are doomed to have to re-learn them. But the other reason to remember our history is remind ourselves of what we already have, and its relevance to the present. Statements by the Public Audit Forum from 20 years ago make salutary reading. Signed by the C&AG of the UK (and of Wales, as they were then), the Auditors-General of Scotland and Northern Ireland, and the Controller of Audit for LPA in England and Wales, it set out their collective understanding of, inter alia, the role of audit at both local and central level. Audit is potent, and ‘can make powerful contributions in the services provided’ and ‘may take the form of national studies’ (Public Audit Forum, Citation2002). Appointed auditors are ‘concerned to improve the financial and general management, and corporate governance, of public services, by identifying and disseminating good, and challenging poor practices and performance’. Improving the ‘quality and performance of public services, and their underlying management systems and processes, is fundamental to the work of … appointed auditors through their primary focus’. They judge ‘current performance … against best practice established by national research and evidence collected from previous audits … concerned with service outcomes … and with identifying opportunities for measurable improvements in service quality … and … take into account the needs of service users’ (Public Audit Forum, Citation2002).

Perhaps more importantly, they see a visceral relationship between audit and positive change:

The process of external review is a powerful catalyst for change in itself … auditors drive change and help improve performance … (and) … build on their ongoing relationship … to encourage worthwhile change … Auditors may also advise … on the implementation of national policy and make recommendations to government. Their reports can produce valuable information and lessons to government on how services are being delivered on the ground, on best practice … the obstacles to improvement, and on the implications for policy. (Public Audit Forum, Citation2002).

What might it look like?

The UK exhibits the near worse and the near best of what LPA can be. Wales and Scotland offer positive cues to be taken, and England those to avoid. The position of LPA in Wales and in Scotland is as a key instrument of community, local and national democratic governance, directed towards significant policy issues such as local economic development, climate change, and levelling-up. It considers policy-to-delivery chains where local action and intervention is crucial to the delivery of regional and national objectives. It enables comparison across local authorities, and conducts studies of common issues and problems both of substantive service delivery and of corporate functions.

In Wales, LPA includes a wide range of studies geared to improving public services, and extends to assessing how both health and local government give effect to the Welsh national objectives of the Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015 (https://www.futuregenerations.wales/about-us/future-generations-act/). Auditors have a duty to help public services learn from each other, and to offer insights to policy-makers. In Scotland, it is a similar story, including for example broad and comparative assessments of local authority actions in relation to the threat of climate change.

A whole system approach

The experience of the English adventure in LPA underlines how it needs to be seen and treated as a ‘whole system’. A fragmented approach does not work. It leaves the ‘system’ vulnerable to the failure of individual parts, and without the means, leadership or guiding strategy to inform system-wide solutions. It has confirmed that an insistence on, for example, a private sector model of audit appointments and workforce supply has to also make provision for what happens when the private sector is no longer interested in offering supply, save on increasingly generous (to them) terms.

This is also where Redmond’s proposals for addressing the crisis in part by strengthening system leadership are badly needed. A system leader could look at the system as a whole, and address problems in a timely, effective, and co-ordinated way. Time will tell whether the government’s new arrangements for performing that function are adequate to the scale of the challenge. This whole system mantra is why the system leader must be able to influence issues of workforce supply and skills, and education and training, and should be able to speak also to questions of codes and standards.

The whole system of LPA is, however, itself embedded in a wider system, that of public service change and improvement. Ferry et al.’s analysis (Citation2022) shows the international trends in LPA, and also underlines how constitutional frameworks and the ‘ideology of audit’ shape the LPA approach taken in different jurisdictions. But the character of LPA in a given jurisdiction is not only a function of these factors. It also takes its cue from the wider legislative and policy/political context, and from the broad development context of particular jurisdictions. For some of those, for example, the fight against corruption has an overwhelming priority. To urge on them the ‘distraction’ of performance auditing would be to distort their commitment to national priorities. Similarly, a society—or government—which is really disinterested in service improvement, and preoccupied solely with imposing austerity, might also insist on the particular focus of cost and economy. Much as some might like LPA to be able to advance universal functional priorities, it remains in large measure an under-labourer function of government. It must take its cue from the democratically determined national priorities and objectives of given societies at given times.

The three stakeholders

All levels of governance—community, local audited body, and national government—have an interest in, and can benefit from, the outputs which LPA can generate. So we should look at how public value could best be maximized from each of their standpoints, including whether the approaches required by each stakeholder might in fact conflict. In other words, there may be situations in which public value creation is a zero-sum game between the stakeholders who stand to benefit from it.

Short of that, maximizing public value for all stakeholders should start with the users and consumers of public services, the individuals and communities who rely on them for their wellbeing and quality of life. For them, LPA should deliver clear information and evaluation of the quality, value for money and effectiveness of the local government, health and other bodies which serve them, and easy opportunities to inquire and challenge. They also need comparative information about ‘their’ local bodies and those enjoyed by other communities. They should have access to help shape the priority areas of LPA inquiry, and they should be centre stage of the LPA system. That does not sound particularly radical, but what a change that would be!

Another major stakeholder is the local bodies themselves. Here one has to acknowledge the tension and even contradiction in the relationship between those entities and their auditors. Few local public bodies enjoy public challenge and criticism of their efforts to deliver public services. When they are challenged, many will either see things differently or simply feel the need to resist, if only because public critique can sometimes lead to private grief for those deemed responsible for failure.

Even within local bodies there are at least four potential audiences. There are those charged with audit matters—the audit committees with responsibility for commissioning the audit and then deploying it. Then there are the politicians. Our vision envisages political leaders embracing LPA as an integral part of their mission in creating public value, including helping them to identify and address problems, creating more opportunities to learn, and providing another lever for positive change. This may simply be too quixotic, though in a local governance environment which should be devoted to whole community service, and personal disinterest in the trappings of office and the status of power, quite what should drive their attitude to LPA and its public value benefits, if not that?

Beyond the politicians are the administrative leaders, for whom similar considerations might apply, and the middle managers and rank-and-file staff who might also benefit from the insights and challenge of LPA. That is itself public value for those looking on, and seeking to make services accountable. If those actors, in turn, use those insights to make positive change, then the public value will be commensurately amplified.

Finally, of course, central government has an important stakeholder interest in the outputs and the outcomes of LPA. In the UK, at any rate, central government (rightly or wrongly) provides significant resources to local public bodies to enable them to deliver services and, often, also to give effect to centrally set objectives. It also has an interest in how local public bodies deliver key policy priorities and services at local level, and in whether they can devolve more power to those bodies with confidence. By providing independent insights in these matters, LPA also creates public value for central government.

Purpose, functions, and scope of LPA

The final, critical, part of our new vision is to chart the breadth of purpose and functions of LPA. Chief among them are those of compliance, assurance, accountability, performance, timeliness and change. The breadth of these functions may seem very radical from our current vantage point. Stretching back to the Public Audit Forum document of 2002, this modern and forward-looking vision can be seen to be connected to that perspective. Moreover, as they said themselves last year, 20 years on, their collaboration ‘can be a source of great strength as we consider … major issues that impact all of us, whether that be the current cost-of-living crisis or the longer term challenges presented through climate change’ (Public Audit Forum, Citation2022).

Alongside the issue of the scope for LPA attention is another important dimension as to whether LPA can provide authoritative foresight and ‘in flight’ assessments, rather than relying almost entirely on historical information. This raises difficult questions around the potential for auditors to be auditing their own work and previous assessments. There are no easy answers, but these are questions which need to be canvassed in the interests of creating public value for LPA’s stakeholders.

There are also various ways in which LPA could be more joined up. One would be to take a holistic approach to the assessments of local public entities so that their corporate functions and their service performance functions were reviewed in toto. The great insight underlying the methodology of the Comprehensive Performance Assessment was the relationship between the two. (CPA was the Audit Commission’s methodology for developing a comprehensive external assessment of a municipality’s performance, both corporate and service, and including, for example, issues of leadership; see Grace, Citation2012, for an account of how CPA fitted into the overall approach to local government improvement in the UK.)

Excellence in long-term service performance, and effective integrated working between service areas, depends on healthy corporate governance and leadership—so they need to be assessed relationally and in the round.

Another aspect of joining up is to bring together for a local public entity the various perspectives and insights of the auditors, regulators and inspectors who all provide external assessments. The primary responsibility for doing this is, of course, the local entities themselves, and the best of them do so. Many do not, and the external assessors themselves rarely do save when these local public bodies are in extremis. It should be a natural thing to do in synergizing the shared, or even differing insights, generated from the various vantage points of the external reviewers of, for example, trusts in health or in education. It should not be left to the stakeholders of these services somehow to make sense and best use of the various insights.

It would also be a relatively small, but important, further conceptual step to look at how joined up and mutually reinforcing are the several and joint efforts of the many local public entities which create public value for a particular urban or rural community in tackling its challenges and realizing its aspirations. Again, one looks primarily to the local democratically-elected body to take this overview, but those who may need to do most may be least well equipped. The best would be the first to see the benefit of augmenting their own judgements with the challenge and perspective provided by an external, independent and authoritative view.

We need LPA to be tailored to the public service context, and the needs of its stakeholders. This calls for a public value specific approach, which includes, as a matter of course, questions of performance, the use of resources, and wider governance issues, and which also has a workforce and a regulatory regime geared to that public service context. Such a vision, if we have it, may be a long way off, and tough to get to. It may not be achieved. However, if we have no vision at all, the chances of realizing the public value potential of LPA is very small indeed.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Baylis, R., & De Widt, D. (2022). Debate: The future of public sector audit training. Public Money & Management, DOI: 10.1080/09540962.2022.2109881

- Benington, J., & Moore, M. H.2010). Public value: theory and practice. Palgrave.

- Bojang, M. B. S. (2021). Public value management: an emerging paradigm in public administration. International Journal of Business, Management and Economics, 2(4), 225–238. https://doi.org/10.47747/ijbme.v2i4.395

- Bozeman, B. (2007). Public value and public interest. Georgetown University Press.

- Bradley, L., Heald, D., & Hodges, R. (2022). Causes, consequences and possible resolution of the local authority audit crisis in England. Public Money & Management. DOI: 10.1080/09540962.2022.2129550

- Broadbent, J. (2022). Debate: Training for public audit. Public Money & Management, DOI: 10.1080/09540962.2022.2154988

- Bryson, J., Sancino, A., Benington, J., & Sørensen, E. (2017). Towards a multi-actor theory of public value co-creation. Public Management Review, 19(5), 640-654. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.108014719037.2016.1192164

- Caperchione, E. (2023). Debate: Promoting a renewed audit profession in the public sector. Public Money & Management. DOI: 10.1080/09540962.2023.2172811

- Dallagnol, E. C., Portulhak, H., & Peixe, B. C. S. (2022). How is public value associated with accountability? A systematic literature review. Public Money & Management, DOI: 10.1080/09540962.2022.2129531

- Davies, G. (2022). Debate: Local public audit in England. Public Money & Management, DOI: 10.1080/09540962.2022.2131283

- Ferry, L., Midgley, H., & Ruggiero, P. (2022). Regulatory space in local government audit: An international comparative study of 20 countries. Public Money & Management. DOI: 10.1080/09540962.2022.2129559

- Freer, S. (2022). Debate: Solving supply shortages and delays in a challenged local public audit system. Public Money & Management. DOI: 10.1080/09540962.2022.2113634

- Freer, S. (2023). Debate: Local audit—buying in a sellers’ market. Public Money & Management, DOI: 10.1080/09540962.2023.2165272

- Grace, C. (2012). From the improvement end of the telescope: benchmarking and accountability in UK local government. In Fenna, A. and Knüpling, F. (Eds). Benchmarking in federal systems. Australian Government Productivity Commission, pp. 41-60. https://www.pc.gov.au/research/supporting/benchmarking-federal-systems/benchmarking-federal-systems.pdf

- Hamid, K. (2023). Debate: Evolving challenges for public sector external audit. Public Money & Management, https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2023.2180874

- HFMA (2021). The NHS external audit market current issues and possible solutions. https://www.hfma.org.uk/publications/details/the-nhs-external-audit-market-current-issues-and-possible-solutions

- HFMA (2022). The NHS external audit market: an update on current issues. https://www.hfma.org.uk/publications/details/the-nhs-external-audit-market-an-update-on-current-issues

- Höglund, L., Mårtensson, M., & Thomson, K. (2021). Strategic management, management control practices and public value creation: the strategic triangle in the Swedish public sector. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 34(7), 1608–1634. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-11-2019-4284

- Jorge, S., Pinto, A., & Nogueira, S. (2022). Debate: Auditing and political accountability in local government—dealing with paradoxes in the relationship between the executive and the council. Public Money & Management. DOI: 10.1080/09540962.2022.2120279

- Langella, C., Vannini, I. L., & Niccolò Persiani, N. (2022). What are the determinants of internal auditing (IA) introduction and development? Evidence from the Italian public healthcare sector. Public Money & Management, DOI: 10.1080/09540962.2022.2129591

- Moore, M. H. (1995). Creating public value: strategic management in government. Harvard University Press.

- Murphie, A., & Fright, M. (2023). Debate: Local public audit—Start from scratch or start from here? Public Money & Management. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2023.2180186

- Murphy, P., Lakoma, K., Eckersley, P., Dom, B. K., & Jones, M. (2023). Public goods, public value and public audit: the Redmond review and English local government. Public Money & Management, DOI: 10.1080/09540962.2022.2126644

- Murray, I. (2023). Debate: Local audit parties are pulling in different directions. Public Money & Management, DOI: 10.1080/09540962.2023.2173371

- Public Audit Forum. (2002). The different roles of external audit, inspection and regulation: a guide for public service managers. NAO.

- Public Audit Forum. (2022). Joint statement from the members of the Public Audit Forum. https://www.public-audit-forum.org.uk/

- Redmond, T. (2020). Independent review into the oversight of local audit and the transparency of local authority financial reporting. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/916217/Redmond_Review.pdf

- Redmond, T. (2023). Debate: Ensuring financial stability in local councils. Public Money & Management, DOI:10.1080/09540962.2023.2166703

- Robertson, L. (2023). Debate: Realizing the opportunities of system-wide audit reform. Public Money & Management. DOI:10.1080/09540962.2023.2187139

- Rönkkö, J., Lilja, M., & Oulasvirta, L. (2022). Voluntary adoption of the International Standards on Auditing (ISA) in local government audits—empirical evidence from Finland. Public Money & Management, DOI: 10.1080/09540962.2022.2131290

- Thomasson, A. (2022). New development: Marketization versus politicization in a perpetual strive for public audit independence. Public Money & Management, DOI: 10.1080/09540962.2022.2120663

- Walker, D. (2023). Debate: Public audit to the rescue of Britain!. Public Money & Management, DOI: 10.1080/09540962.2022.2139946

- Witesman, E. (2016). From public values to public value and back again. Brigham Young University. https://cord.asu.edu/sites/default/files/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/2015123001-Public-value-to-public-values-and-back-for-PVC1.pdf.