Abstract

Objective

Biologic therapies have revolutionized the management of moderate-to-severe psoriasis; however, there are a limited number of US real-world studies characterizing patients based on response to these treatments. This study examined characteristics at enrollment and change in outcomes of US patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis who achieved insufficient responses with ustekinumab.

Methods

This study included patients enrolled in the Corrona Psoriasis Registry from April 2015 to June 2018 who initiated ustekinumab at enrollment and who were stratified based on achievement of psoriasis body surface area improving to <3% or by 75% from enrollment to the 6-month follow-up visit (response vs insufficient response). Patient demographics and disease characteristics were described at enrollment, and changes in outcomes were assessed at 6-month follow-up for ustekinumab responders and insufficient responders.

Results

Of the 178 patients who initiated ustekinumab in the Corrona Psoriasis Registry and had ≥1 follow-up visit, 99 (55.6%) were classified as responders at the 6-month follow-up visit. Logistic regression modeling showed that increasing age was significantly associated with a decreased likelihood of achieving a response (OR, 0.981 [95%CI, 0.962–0.999]; p = .049).

Conclusions

These findings may help dermatologists characterize patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis who have inadequate responses to biologic treatments.

Introduction

Psoriasis is a common, chronic, immune-mediated inflammatory skin disorder that affects 2–4% of the US population (Citation1). Signs and symptoms associated with psoriasis skin lesions impact the physical, psychological, and social health of patients with psoriasis (Citation2,Citation3). The severity of psoriasis can be classified based on percentage of affected body surface area (BSA; mild [<3%], moderate [3–10%], severe [>10%]) (Citation4,Citation5).

The mainstay treatments for psoriasis continue to be topical medications, phototherapy, and traditional systemic therapies; however, the advent of biologic therapies has revolutionized the management of patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis (Citation6). Biologic treatments for psoriasis include tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFis; adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, and infliximab) (Citation6–16), the interleukin (IL)-12/23 inhibitor ustekinumab (Citation17–19), the IL-23 inhibitors guselkumab, tildrakizumab, and risankizumab (Citation20–24), the IL-17A inhibitors secukinumab and ixekizumab (Citation25–29), and the IL-17RA antagonist brodalumab (Citation30,Citation31). The goals for treatment of psoriasis are not well-defined in the United States, but international groups have described improvements in percentage of affected BSA, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI), and lesion severity using the Physician Global Assessment as measurable targets (Citation32,Citation33). The National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) conducted a study among US experts to determine their preferences for instruments and treatment targets that are feasible in clinical practice (Citation34). The most acceptable response at 3 months was described by the panel as either BSA <3% or a 75% improvement in BSA from baseline, with achievement of BSA ≤1% as the ideal target response (Citation34).

While consensus treatment targets are practical and informative tools for clinicians to evaluate treatment response in clinical practice, there are few US real-world studies that describe outcomes with first-line biologic therapies, such as TNFis or ustekinumab, and characterize patients based on response to these biologic therapies. The objective of this descriptive, cross-sectional analysis of the Corrona® Psoriasis Registry was to examine differences in characteristics at registry enrollment and compare the magnitude of change in outcomes in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis who did or did not achieve responses with ustekinumab at their first follow-up visit (≈6 months).

Materials and methods

Study setting

The Corrona Psoriasis Registry is a prospective, multicenter, observational disease-based registry launched in April 2015 in collaboration with the NPF and has been previously described (Citation35). At the time of the analysis, patients were recruited from 170 private and academic practice sites across 41 US states, with 401 participating dermatologists. Patients are enrolled into the registry if they meet all the following inclusion criteria: psoriasis diagnosed by a dermatologist, age ≥18 years, and has initiated or switched to and continued a US Food and Drug Administration–approved systemic or biologic treatment for psoriasis within the previous 12 months. Questionnaires completed by patients and their treating dermatologists are used to collect follow-up data approximately every 6 months.

As of 30 June 2018, Corrona had enrolled 5302 patients and had data on 12,736 patient visits, with 4345.1 patient-years of follow-up observation time. The mean duration of patient follow-up was 1.40 years (median, 1.29 years). The Corrona Psoriasis Registry was approved by both local and central (IntegReview, Corrona-PSO-500) review boards at participating sites. All patients were required to provide written, informed consent.

Study population

Details of the study population and definition of response are similar to a previous analysis examining response to a different class of biologic therapy within the Corrona registry (Citation36). Briefly, all patients included were aged ≥18 years with moderate-to-severe psoriasis (defined as affected BSA ≥ 3%) enrolled in the Corrona Psoriasis Registry between April 2015 and June 2018 who initiated ustekinumab at the enrollment visit (index therapy) and had ≥1 follow-up visit (i.e. a 6-month follow-up visit) during the observation period with nonmissing BSA data at the enrollment and 6-month visits. Patients were stratified based on achievement of treatment response—for the purpose of this study, ‘responders’ were defined as ustekinumab initiators who achieved an improvement of BSA to <3% or a 75% improvement in BSA from enrollment to the 6-month follow-up visit, and ‘insufficient responders’ were defined as those patients who either remained at moderate-to-severe disease activity (BSA ≥ 3%) or did not achieve a 75% improvement in BSA from enrollment by the 6-month follow-up visit. Patients who switched to another biologic or discontinued their index biologic for efficacy or safety reasons at the 6-month follow-up visit were also classified as insufficient responders.

Study variables and outcomes

The study variables and outcomes for a similar analysis examining response to TNFi therapy were previously described (Citation36). Data collected using questionnaires completed by patients and their treating dermatologists at the time of ustekinumab initiation at the enrollment visit included the following: demographics (age, sex, race, ethnicity, and body mass index [BMI]); prior use of biologic therapies; clinical characteristics (duration of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis and history of comorbidities); disease characteristics (5-point Investigator’s Global Assessment [IGA; 0–4], BSA [continuous and categorical], and PASI [0–72]); and patient-reported outcomes (PROs; patient overall pain, itch, and fatigue visual analog scale [VAS], 0–100; Dermatology Life Quality Index [DLQI; 0–30]; overall health status measured by the EuroQol VAS [EQ VAS; 0–100]; and Work Productivity and Activity Impairment questionnaire [WPAI]).

Mean and categorical changes in outcomes from enrollment to the 6-month follow-up visit were assessed for responders and insufficient responders to index ustekinumab therapy and included change from enrollment in disease activity measures (achievement of IGA 0/1 among those in IGA 2−4 at enrollment, and achievement of PASI 75 and PASI 90) and PROs (mean [SD] change in patient pain and patient itch, and achievement of DLQI score 0−5 among those with DLQI score 6−30 at enrollment).

Data analysis

Descriptive analyses of patient demographics, treatment histories, clinical characteristics, and PROs were conducted at time of enrollment and were performed separately for ustekinumab responders and insufficient responders. Categorical variables were summarized using frequency counts and percentages, while continuous variables were summarized by the number of observations and the mean (SD).

Data analysis was performed as described in a previous Corrona study and was based on as-observed available data (Citation36). Patient demographics, treatment histories, clinical characteristics, and PROs in responders and insufficient responders at enrollment were compared using standardized differences (standardized difference <0.1 denotes negligible difference) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to quantify the effect size independent of sample sizes. For proportions and means, the standardized differences were calculated using the absolute differences divided by a pooled variation, and for categorical variables, the standardized differences were calculated using a multivariate Mahalanobis distance method (Citation37).

For change in outcomes from enrollment to the 6-month follow-up visit, standardized differences (95%CI) were used to quantify differences in outcomes between responders and insufficient responders. Statistical significance for change in outcomes was determined using paired t-tests for continuous outcomes and Wilcoxon’s rank-sum tests for interval/ordinal outcomes.

An exploratory analysis was performed using logistic regression modeling to determine the association of baseline covariates with response to ustekinumab at the 6-month follow‐up visit in the presence of multiple explanatory variables to reduce confounding effects. Characteristics included for the exploratory modeling were chosen a priori based on clinical and statistical insights or were considered and selected when significantly different between responders and insufficient responders (|standardized difference| > 0.1). Parameters included age (continuous), female sex (reference: male), BMI (continuous), BSA (continuous), and fatigue (continuous). The final reported model was determined by the χ2 goodness‐of‐fit significance test. Associations were presented as odds ratios (ORs) and 95%CIs. Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Demographics and treatment characteristics at enrollment

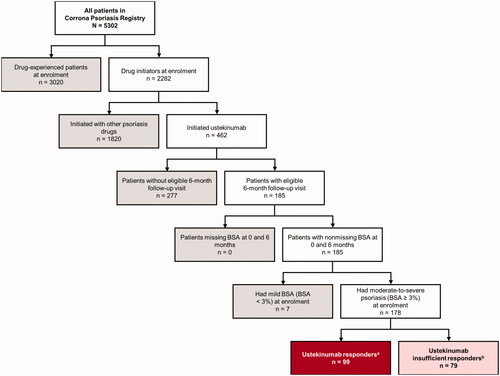

As of June 2018, 5302 patients were enrolled in the Corrona Psoriasis Registry, of whom 2282 initiated systemic therapy at the time of enrollment, including 462 who initiated ustekinumab (). Of those, 178 ustekinumab initiators met the study inclusion criteria, with 99 patients (55.6%) and 79 patients (44.4%) classified as responders and insufficient responders, respectively, based on achievements of BSA or BSA improvement targets. Responders and insufficient responders shared similarities in demographics and patient characteristics at enrollment; however, there were imbalances (). Compared with insufficient responders, responders were younger (mean [SD] age, 46.7 [16.9] vs 51.4 [15.5] years), more likely to be male (52.5% vs 43.0%), and less likely to be white (83.8% vs 87.3%) or overweight or obese (68.0% vs 79.7%). The proportion of responders and insufficient responders, respectively, who had prior biologic use was 48.5% and 51.9%. Among patients with prior biologic use, a lower proportion of responders vs insufficient responders used only 1 prior biologic (58.3% vs 70.7%) vs ≥2 prior biologics.

Figure 1. Patient disposition flow chart. BSA: body surface area. aResponders were defined as patients who achieved either an improvement of BSA to <3% or a 75% improvement in BSA from enrollment to the 6-month follow-up visit. bInsufficient responders were defined as patients who remained at moderate-to-severe disease activity (BSA ≥3%) or those who did not achieve a 75% improvement in BSA from enrollment to the 6-month follow-up visit. Patients who discontinued their index biologic or switched to another biologic for efficacy or safety reasons at the 6-month follow-up visit were also classified as insufficient responders.

Table 1. Demographics and treatment history of patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis at enrollment stratified by response to index ustekinumab therapy at 6 months.

Clinical characteristics and patient-reported outcome measures at enrollment

Responders and insufficient responders were similar at enrollment in terms of IGA scores, percentage of affected BSA, and PASI scores; however, responders had a shorter mean (SD) duration of psoriasis (14.1 [13.0] vs 16.5 [15.6] years), a lower worst BSA ever recorded (20.0% [17.9%] vs 27.9% [20.7%]), and a lower prevalence of hypertension (21.2% vs 31.6%), diabetes mellitus (7.1% vs 17.7%), and cardiovascular disease (2.0% vs 12.7%) (). The proportion of responders and insufficient responders who had PsA was similar (20.2% vs 22.8%), while the duration of PsA in those affected was shorter in responders than insufficient responders (4.4 [4.4] vs 12.1 [10.9] years). Interestingly, a higher proportion of responders than insufficient responders reported anxiety (25.3% vs 16.5%) and depression (24.2% vs 17.7%).

Table 2. Clinical characteristics and patient-reported outcome measures of patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis at enrollment stratified by response to index ustekinumab therapy at 6 months.

Both ustekinumab response groups reported similar degree of burden across all PRO measures, although there were numerical differences in pain, itch, and fatigue scores, EQ VAS scores, and work impairment (WPAI domains) that suggested insufficient responders were more impaired at enrollment ().

Change in clinical and patient-reported outcomes from enrollment at 6-month follow-up

Expectedly, at the 6-month follow-up visit responders had achieved significant differences in mean and categorical improvements from enrollment in all clinical and PROs assessed compared with the insufficient responders ().

Table 3. Change in outcomes from enrollment to 6-month follow-up among responders and insufficient responders to index ustekinumab therapy.

In the exploratory analysis, logistic regression modeling of the adjusted association of characteristics at enrollment with response to ustekinumab found that increasing age was significantly associated with a decreased likelihood of achieving a response at the 6-month follow-up visit (OR, 0.981 [95%CI, 0.962–0.999]; p = .049) (). There were no significant associations between ustekinumab response and sex, BMI, BSA at enrollment, or fatigue.

Table 4. Exploratory analysis: logistic regression modeling of the adjusted association of characteristics at enrollment with response to ustekinumab at the 6-month follow-up visita.

Discussion

This analysis of US patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis in the Corrona Psoriasis Registry showed that 55.6% of patients who initiated ustekinumab were classified as responders at the 6-month follow-up visit. Although there were imbalances in patient characteristics between response groups, only increasing age was associated with decreased likelihood of achieving a response. A modified definition of treatment response was used, based on a consensus expert opinion conducted by the NPF, that described the most acceptable response at 3 months as either BSA < 3% or a 75% improvement in BSA from baseline; the modification was made to extend the time to acceptable response from 3 to 6 months (Citation34). Since Corrona follow-up visits take place approximately every 6 months, the same target was used for response at the time of the first follow-up visit, allowing the treating dermatologist to make treatment decisions based on the observed response. Furthermore, this target has been previously used in the Corrona Psoriasis Registry to identify patients who responded vs those who did not respond to TNFi therapies (Citation36). Insufficient responders and responders were both similarly burdened by disease at enrollment, but there were imbalances between groups across some patient characteristics: the responders were younger, were less likely to have a history of hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes mellitus, and reported a lower worst BSA ever recorded than the insufficient responders.

Compared with insufficient responders, responders to ustekinumab demonstrated significant improvements in clinical outcomes at the 6-month follow-up, as well as patient-reported pain and itch, as expected. When adjusting for differences in patient characteristics to determine association of covariates at enrollment with response to ustekinumab at the 6-month follow-up, only increasing age was significantly associated with a decreased likelihood of achieving a response, while neither sex, BMI, BSA at enrollment, nor fatigue wasassociated with achievement of a response. Increasing age may be associated with longer disease duration and increased prior biologic use, suggesting these patients are more refractory to treatment. Although BSA is the preferred clinical instrument for assessing psoriasis treatment response and is readily easy to use in a routine clinical setting, it may be subject to high interobserver variability and does not account for severity of lesions (Citation34,Citation38). Moreover, BSA, PASI, and IGA measures, which are instruments that take into consideration clinical presentation of the disease, can provide a more detailed assessment of disease activity and response to therapy and have been shown to be closely correlated in patients with psoriasis in clinical settings (Citation34,Citation38,Citation39). This study is consistent with these observations, as BSA-defined responders had significant improvement from enrollment in IGA and PASI scores at 6 months compared with BSA-defined insufficient responders (Citation39,Citation40).

Beyond the physical symptoms of pain and itch, psoriasis has an impact on physical and mental components similar to that of other chronic diseases (Citation41). Ustekinumab responders were more likely to have a history of anxiety and depression at enrollment than insufficient responders. The appearance of psoriatic plaques associated with the social stigma can lead to social isolation, anxiety, and depression in patients with psoriasis (Citation42,Citation43). Although increased psoriasis disease severity is associated with worsened PROs (Citation44), the impact of psoriasis on patients’ health-related quality of life does not always correlate with disease severity. For example, in a large, multinational, population-based survey, approximately 25% of patients with mild disease (BSA ≤ 3%) reported a substantial negative impact of psoriasis on their health-related quality of life, suggesting that even a small amount of disease activity can impact quality of life (Citation45). Furthermore, disease severity has been observed to be higher in patient-reported than physician-assessed measurements (Citation46,Citation47). A more comprehensive assessment of response to therapy can be ascertained by PRO instruments by providing information from a patient perspective about the effectiveness of therapies through measuring improvement in health-related quality of life.

Limitations

This study has limitations that are common to all real-world observational studies. These results from a US registry may not be generalizable to patients with psoriasis outside of the United States. Because participation in the Corrona Psoriasis Registry by patients and their treating dermatologists is voluntary, results may be influenced by selection bias. This study was limited by the small number of patients who initiated ustekinumab at enrollment with a short follow-up period (≈6 months), which may impede meaningful analysis of response. Although response was based on achievement of BSA or BSA improvement targets to reflect NPF target guidelines, caution should be used when using BSA as the sole metric of achievement of responses; in our study, 32% and 13% of insufficient responders, respectively, achieved PASI 75 and PASI 90. Larger studies with longer follow-up are needed to better characterize patients who achieve a sustained response with their index biologic and to perform adjusted analyses.

Conclusions

These data from the Corrona Psoriasis Registry showed that increasing age may be associated with decreased response to treatment and provide valuable insights into the disease burden and outcomes in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis who respond or do not respond to their index ustekinumab therapy in US clinical practice. Further analyses with larger sample sizes and longer follow-up periods are needed to better differentiate characteristics between responders and insufficient responders. However, findings from this study may help clinicians identify patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis who have unmet treatment needs.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the investigators, their clinical staff, and patients who participate in the Corrona Psoriasis Registry.

Disclosure statement

A.S. Van Voorhees has served on an advisory board from Dermira, Novartis, Allergan, DermTech, and Valeant and has served as a consultant for Dermira, Novartis, and AbbVie; M.A. Mason and N. Guo are employees of Corrona, LLC; L.R. Harrold has received a grant from Pfizer, has served as a consultant for AbbVie, BMS, and Roche, and is an employee and stockholder of Corrona, LLC; A. Guana was an employee of Novartis at the time of this study; H. Tian is an employee of Novartis; V. Herrera is an employee and stockholder of Novartis; B.E. Strober has served as a consultant for Corrona, LLC.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Rachakonda TD, Schupp CW, Armstrong AW. Psoriasis prevalence among adults in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(3):512–516.

- Greb JE, Goldminz AM, Elder JT, et al. Psoriasis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16082.

- Rapp SR, Feldman SR, Exum ML, et al. Psoriasis causes as much disability as other major medical diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(3):401–407.

- Horn EJ, Fox KM, Patel V, et al. Are patients with psoriasis undertreated? Results of National Psoriasis Foundation survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(6):957–962.

- Horn EJ, Fox KM, Patel V, et al. Association of patient-reported psoriasis severity with income and employment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(6):963–971.

- Menter A, Feldman SR, Weinstein GD, et al. A randomized comparison of continuous vs. intermittent infliximab maintenance regimens over 1 year in the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(1):31.e1–15.

- Menter A, Tyring SK, Gordon K, et al. Adalimumab therapy for moderate to severe psoriasis: a randomized, controlled phase III trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(1):106–115.

- Elewski BE, Okun MM, Papp K, et al. Adalimumab for nail psoriasis: efficacy and safety from the first 26 weeks of a phase 3, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(1):90–99.e1.

- Gordon KB, Langley RG, Leonardi C, et al. Clinical response to adalimumab treatment in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis: double-blind, randomized controlled trial and open-label extension study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(4):598–606.

- Gottlieb AB, Blauvelt A, Thaçi D, et al. Certolizumab pegol for the treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis: Results through 48 weeks from 2 phase 3, multicenter, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled studies (CIMPASI-1 and CIMPASI-2). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79(2):302–314.e6.

- Lebwohl M, Blauvelt A, Paul C, et al. Certolizumab pegol for the treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis: results through 48 weeks of a phase 3, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, etanercept- and placebo-controlled study (CIMPACT). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79(2):266–276.e5.

- Leonardi CL, Powers JL, Matheson RT, et al. Etanercept as monotherapy in patients with psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(21):2014–2022.

- Paller AS, Siegfried EC, Langley RG, et al. Etanercept treatment for children and adolescents with plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(3):241–251.

- Papp KA, Tyring S, Lahfa M, et al., the Etanercept Psoriasis Study Group. A global phase III randomized controlled trial of etanercept in psoriasis: safety, efficacy, and effect of dose reduction. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152(6):1304–1312.

- Gottlieb AB, Evans R, Li S, et al. Infliximab induction therapy for patients with severe plaque-type psoriasis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51(4):534–542.

- Reich K, Nestle FO, Papp K, et al. Infliximab induction and maintenance therapy for moderate-to-severe psoriasis: a phase III, multicentre, double-blind trial. Lancet. 2005;366(9494):1367–1374.

- Landells I, Marano C, Hsu MC, et al. Ustekinumab in adolescent patients age 12 to 17 years with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: results of the randomized phase 3 CADMUS study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(4):594–603.

- Leonardi CL, Kimball AB, Papp KA, et al. Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab, a human interleukin-12/23 monoclonal antibody, in patients with psoriasis: 76-week results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (PHOENIX 1). Lancet. 2008;371(9625):1665–1674.

- Papp KA, Langley RG, Lebwohl M, et al. Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab, a human interleukin-12/23 monoclonal antibody, in patients with psoriasis: 52-week results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (PHOENIX 2). Lancet. 2008;371(9625):1675–1684.

- Blauvelt A, Papp KA, Griffiths CE, et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab, an anti-interleukin-23 monoclonal antibody, compared with adalimumab for the continuous treatment of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis: results from the phase III, double-blinded, placebo- and active comparator-controlled VOYAGE 1 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(3):405–417.

- Langley RG, Tsai TF, Flavin S, et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab in patients with psoriasis who have an inadequate response to ustekinumab: results of the randomized, double-blind, phase III NAVIGATE trial. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(1):114–123.

- Reich K, Armstrong AW, Foley P, et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab, an anti-interleukin-23 monoclonal antibody, compared with adalimumab for the treatment of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis with randomized withdrawal and retreatment: results from the phase III, double-blind, placebo- and active comparator-controlled VOYAGE 2 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(3):418–431.

- Reich K, Papp KA, Blauvelt A, et al. Tildrakizumab versus placebo or etanercept for chronic plaque psoriasis (reSURFACE 1 and reSURFACE 2): results from two randomised controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2017;390(10091):276–288.

- Gordon KB, Strober B, Lebwohl M, et al. Efficacy and safety of risankizumab in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis (UltIMMa-1 and UltIMMa-2): results from two double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled and ustekinumab-controlled phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2018;392(10148):650–661.

- Blauvelt A, Prinz JC, Gottlieb AB, et al., the FEATURE Study Group. Secukinumab administration by pre-filled syringe: efficacy, safety and usability results from a randomized controlled trial in psoriasis (FEATURE). Br J Dermatol. 2015;172(2):484–493.

- Langley RG, Elewski BE, Lebwohl M, et al. Secukinumab in plaque psoriasis–results of two phase 3 trials. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(4):326–338.

- Paul C, Lacour JP, Tedremets L, et al., the JUNCTURE study group. Efficacy, safety and usability of secukinumab administration by autoinjector/pen in psoriasis: a randomized, controlled trial (JUNCTURE). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(6):1082–1090.

- Gordon KB, Colombel JF, Hardin DS. Phase 3 Trials of ixekizumab in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(21):2102.

- Griffiths CE, Reich K, Lebwohl M, et al. Comparison of ixekizumab with etanercept or placebo in moderate-to-severe psoriasis (UNCOVER-2 and UNCOVER-3): results from two phase 3 randomised trials. Lancet. 2015;386(9993):541–551.

- Lebwohl M, Strober B, Menter A, et al. Phase 3 studies comparing brodalumab with ustekinumab in psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(14):1318–1328.

- Papp KA, Reich K, Paul C, et al. A prospective phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of brodalumab in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175(2):273–286.

- Gulliver W, Lynde C, Dutz JP, et al. Think beyond the skin: 2014 Canadian expert opinion paper on treating to target in plaque psoriasis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2015;19(1):22–27.

- Mrowietz U, Kragballe K, Reich K, et al. Definition of treatment goals for moderate to severe psoriasis: a European consensus. Arch Dermatol Res. 2011;303(1):1–10.

- Armstrong AW, Siegel MP, Bagel J, et al. From the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation: treatment targets for plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(2):290–298.

- Strober B, Karki C, Mason M, et al. Characterization of disease burden, comorbidities, and treatment use in a large, US-based cohort: results from the Corrona Psoriasis Registry. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(2):323–332.

- Van Voorhees AS, Mason MA, Harrold LR, et al. Characterization of insufficient responders to anti-tumor necrosis factor therapies in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis: real-world data from the US Corrona Psoriasis Registry. J Dermatolog Treat. 2019. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/09546634.2019.1656797. [Epub ahead of print].

- Yang D, Dalton JE. A unified approach to measuring the effect size between two groups using SAS®. Orlando, FL: SAS Global Forum. 2012. https://support.sas.com/resources/papers/proceedings12/335-2012.pdf

- Spuls PI, Lecluse LL, Poulsen ML, et al. How good are clinical severity and outcome measures for psoriasis?: quantitative evaluation in a systematic review. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130(4):933–943.

- Langley RG, Feldman SR, Nyirady J, et al. The 5-point Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) Scale: a modified tool for evaluating plaque psoriasis severity in clinical trials. J Dermatolog Treat. 2015;26(1):23–31.

- Lane S, Lozano-Ortega G, Wilson J, et al. Assessing severity in psoriasis: correlation of difference measures (PASI, BSA, and IGA) in a Canadian real-world setting. Value Health. 2016;19(3):A122.

- Moller AH, Erntoft S, Vinding GR, et al. A systematic literature review to compare quality of life in psoriasis with other chronic diseases using EQ-5D-derived utility values. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2015;6:167–177.

- Bewley A, Burrage DM, Ersser SJ, et al. Identifying individual psychosocial and adherence support needs in patients with psoriasis: a multinational two-stage qualitative and quantitative study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28(6):763–770.

- Dowlatshahi EA, Wakkee M, Arends LR, et al. The prevalence and odds of depressive symptoms and clinical depression in psoriasis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134(6):1542–1551.

- Strober B, Greenberg JD, Karki C, et al. Impact of psoriasis severity on patient-reported clinical symptoms, health-related quality of life and work productivity among US patients: real-world data from the Corrona Psoriasis Registry. BMJ Open. 2019;9(4):e027535.

- Lebwohl MG, Bachelez H, Barker J, et al. Patient perspectives in the management of psoriasis: results from the population-based Multinational Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis Survey. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;70(5):871–881.e1-30.

- Paul C, Bushmakin AG, Cappelleri JC, et al. Do patients and physicians agree in their assessment of the severity of psoriasis? Insights from tofacitinib phase 3 clinical trials. J Dermatolog Clin Res. 2015;3(3):1048.

- Lebwohl MG, Kavanaugh A, Armstrong AW, et al. US perspectives in the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: patient and physician results from the population-based multinational assessment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis (MAPP) survey. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17(1):87–97.