Abstract

Background

This study describes the current treatment landscape in adult atopic dermatitis (AD), overall and by disease severity.

Methods

Adult patients with an AD diagnosis in dermatology-specific electronic medical records during 2018 were identified and linked to an administrative claims database. Disease severity was determined using Physician’s Global Assessment (PGA). Written and dispensed prescriptions, within and between class cycling for AD therapies occurring in 2018 were assessed.

Results

In total, 4,364 patients were included. Among patients with available PGA, 43.2% had clear-to-mild, 37.3% had moderate, and 19.6% had severe disease. Most patients (71.0%) had written prescriptions for topical therapies only in 2018. Among the patients with claims for topical therapies alone, 80.7% used topical corticosteroids only. Within and between class cycling was observed in 33.7% and 12.8% of topical users, respectively. In patients with systemic therapy (40.6%), nearly 84.9% also used topical therapy, 25.8% cycled within systemic drug classes, and 24.8% cycled between systemic drug classes. Overall, cycling was more prevalent in patients with more severe disease.

Conclusion

Cycling within and between both topical and systemic drug classes was more common in patients with more severe disease, indicating difficulty of managing these patients and highlighting a need for more treatment options.

Background

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic relapsing inflammatory skin disease characterized by acute or chronic eczematous skin lesions accompanied by intense itching, with an estimated prevalence of 24% in children and 7% in adults in the United States (US) (Citation1–3). Management of AD is complex, particularly in patients with more severe disease. Treatment guidelines recommend a stepwise approach that depends on disease severity (Citation4). Non-pharmacologic interventions, such as the use of moisturizers to improve the skin’s hydration, are the recommended first-line treatment for mild disease and ongoing maintenance (Citation4). Topical treatments are the mainstay of AD management and are typically introduced after inadequate response to good skin care and use of moisturizers. In most patients with mild-to-moderate disease, topical therapies are sufficient to manage the disease (Citation5), and include topical corticosteroids (TCS), topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCI) and topical phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitors. TCS are the most widely used treatment for AD and are prescribed for active inflammatory disease and for the prevention of relapse (Citation6). Overall, TCS have a good safety profile, however prolonged use can lead to adverse events. TCI were approved in 2000 and are recommended for acute and chronic treatment, specifically for patients who have failed TCS or for use on sensitive areas of the body, such as the face (Citation6). PDE4 inhibitors were introduced as a new treatment option for AD in 2016 with the FDA approval of crisaborole for the treatment of mild-to-moderate AD. PDE4 inhibitors are considered a safer treatment option than TCS and TCI for mild-to-moderate AD (Citation7). Phototherapy used as monotherapy or in combination with topical therapies is the recommended second-line treatment in patients whose AD is non-responsive to topical therapies alone. Systemic agents are recommended in patients who fail on topical therapies and/or phototherapy, and in patients with poor quality of life caused by AD, however they should be used with caution as many (particularly systemic corticosteroids) are associated with short- and long-term adverse events and have an unfavorable risk-benefit profile (Citation8). In 2017, dupilumab was the first biologic therapy to be approved for the treatment of adult patients with moderate-to-severe AD who were inadequately controlled with topical and/or systemic treatments. In clinical trials, dupilumab was well-tolerated with low rates of serious adverse events and discontinuation due to adverse events (Citation9). Several anti-inflammatory agents are currently in late-phase clinical development for the treatment of atopic dermatitis, many of which target patients with moderate-to-severe disease (Citation10). Oral and topical Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors have generally demonstrated a favorable safety profile and efficacy in achieving primary endpoints in clinical trials (Citation11).

Little current data has been published on the current comprehensive treatment landscape in adult atopic dermatitis. One study, published in 2019 using claims data between 2010 and 2014, reported utilization of off-label systemic immunosuppressants prior to the introduction of biologic therapy (Citation12). A real-world study conducted by Eichenfield and colleagues reported treatment patterns in AD using more current data through June of 2018, however the focus was on pediatric and adult patients with AD who newly initiated systemic treatments (Citation13). The primary aim of the current study was to describe the real-world use of AD therapies in adults in the United States (US) during 2018 using electronic medical records (EMR) linked to insurance claims data. The results were further stratified by disease severity obtained from EMR.

Methods

For the purpose of this study, data from Modernizing Medicine’s Electronic Medical Assistant (EMATM) specialty-specific EMR database for dermatology was linked to the IQVIA PharMetrics® Plus database. EMA contains structured, real-world data from over 9,000 dermatology providers. PharMetrics Plus contains adjudicated medical and pharmacy claims for more than 150 million health plan members across the United States from 2006 onwards and is representative of the U.S. commercially insured population. All patient-level data were de-identified by Modernizing Medicine Data Services, Inc. (MMDS) and IQVIA in accordance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA). Patients from EMA were linked to the PharMetrics Plus database using deterministic matching, which requires exact matching on patient information. To ensure minimal risk of re-identification of patients due to linkage, dates in the two databases were independently shifted ± 15 days and an additional 15-day grace period was added to the index date to account for lags between written and filled prescriptions, thus a 45-day window around index dates was established.

Adult (≥18 years) patients with at least one record having a clinical diagnosis of AD (ICD-10-CM codes L20.0, L20.8, L20.89, L20.9) were identified in EMA between November 11, 2017 and December 31, 2018 to allow for the 45-day window around the index date for the linked data. The date of the first observed AD diagnosis was defined as the index date. The final study population consisted of patients with linkage to PharMetrics Plus, continuous health plan enrollment with medical and pharmacy benefits during calendar year 2018, and a medical claim with a diagnosis code of AD within 45 days of the index date. Descriptions of the ICD-10-CM codes used to identify AD are provided in Supplemental Table 1. AD-related medications included in the study are reported in Supplemental Table 2.

Measures

Dermatologist prescribed and office-administered AD medications observed in EMA during 2018 are reported at the drug-class level overall and by disease severity. Prescriptions claims, which indicate drugs dispensed, for AD treatments observed in 2018 are reported overall and by disease severity. Results include topical and systemic therapy drug classes received, number of unique drugs used, proportion of days covered (PDC) for systemic therapy, and total days with no systemic drug coverage. Cycling within topical and systemic treatments was assessed. For each treatment category, within and between drug class cycling was reported. Within drug class, cycling was defined by observing claims for multiple drugs from the same drug class (e.g. within corticosteroids, dexamethasone to prednisone). Between drug class cycling was defined by observing claims for drugs from multiple classes (e.g. systemic steroids to biologics). PDC was calculated separately for each systemic therapy drug class as the total days’ supply divided by the total observed period, i.e. 360 days. Concomitant medication use observed in claims was also reported overall and by disease severity. Medications of interest included: asthma medications, antihypertensives, antidiabetics, antidepressants and anti-anxiety medications, antibiotics, antivirals, antifungals, sleep aides, and pain medication.

Treatment use was further stratified by disease severity which was measured by the Physician’s Global Assessment (PGA) from EMA. The PGA is a physician-reported measure assessing overall disease severity at a given point in time on a five-point scale ranging from 0 to 4, 0-1 indicating clear/almost clear, 2 indicating mild, 3 indicating moderate and 4 indicating severe AD (Citation14). Baseline severity was defined by the PGA result closest to the index date. Patient subgroups based on severity were defined as clear-to-mild, moderate, and severe.

Statistical methods

Mean, standard deviation (SD), and median are reported as measures of central tendency and variance for continuous variables. Frequency and percentages are reported for categorical variables. Student’s t and Chi-Square tests were used to compare continuous and categorical variables, respectively, between patients with clear-to-mild vs. moderate and clear-to-mild vs. severe disease. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

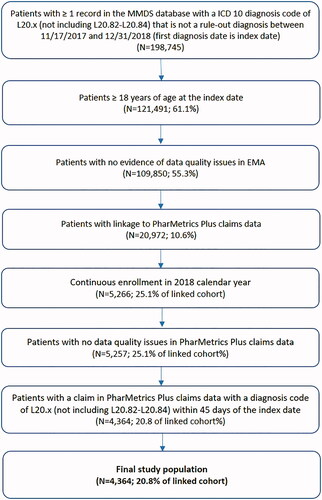

Overall, 198,745 patients with a clinical diagnosis of AD between November 11, 2017 and December 31, 2018 were identified in the de-identified data from EMA, of which 10.6% linked to PharMetrics Plus. Among the patients who were linked (n = 20,972), 25.1% had continuous health plan enrollment in 2018 and 893 (4.3%) patients were excluded for not having a claim with a diagnosis code of AD within 45 days of the index date, resulting in a final study population of 4,364 (20.8%) patients (). Among the 893 patients excluded for not having a claim with an AD diagnosis within 45 days of the index date, 28.4% had an outpatient visit to a dermatologist during this time window, 38.1% had a claim with an ICD-10-CM code for skin and/or subcutaneous tissue (L-code) diseases during this time window, and 11.5% of patients did not have any claims between November 17, 2017 and December 31, 2018.

details the demographic and clinical characteristics of the study sample, overall and stratified by disease severity. The mean (SD) age was 41.8 (15.3) years and 64.9% were female. Most patients were from the South (45.4%) and Midwest (25.9%) regions of the US. Patients had a low comorbidity burden, with 92.2% of patients having a Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) score of 0 or 1. Common comorbid conditions observed in 2018 included depression (31.1%), hypertension (24.0%) and allergic contact dermatitis (22.9%). The most commonly reported lesion locations were the arms (38.8%) and trunk (30.6%).

Table 1. Demographics and clinical characteristics in adults with AD.

Nearly 22% of patients had a PGA score. Among these, 43.2% had clear-to-mild disease, 37.3% had moderate disease, and 19.6% had severe disease. Some differences were observed between the severity cohorts. A higher proportion of patients with severe disease were male compared to patients with clear-to-mild disease (45.2% vs. 34.9%; p=.02) (). Asthma (32.8% vs. 22.0%; p<.01), allergic rhinitis (21.5% vs. 13.2%; p<.01), and pruritus (24.2% vs. 12.2%; p<.01) were more common in patients with severe disease than patients with clear-to-mild disease. The proportion of patients with total body surface area (BSA) reported increased with level of disease severity as measured by the PGA and ranged from 26.3% of patients with clear-to-mild disease to 72.0% of patients with severe disease. Among the patients with available BSA, a BSA > 50% was more common in patients with severe disease as measured by PGA than in patients with clear-to-mild disease (32.8% vs. 5.6%; p<.0001).

Prescribing patterns observed in EMA

describes AD therapies prescribed in 2018. Most patients (71.0%) only had written prescriptions for topical therapies in 2018, with corticosteroids being the most commonly prescribed topical therapy class. Roughly 17.2% of patients had written prescriptions or in-office administration of systemic therapies. Systemic steroids (10.2%) and biologics (7.8%) were the most frequently prescribed systemic treatments observed in 2018. Nearly 12% of patients had no observed written prescriptions for topical or systemic therapy in 2018. Among these patients, prescriptions for other AD-related therapies were uncommon, with less than 1% of patients having written prescriptions for topical antihistamines, topical retinoids, or topical vitamin D3 analogues.

Table 2. Prescribed and dispensed AD therapies observed in 2018, overall and stratified by disease severity.

Differences in prescription patterns were observed by severity. Written prescriptions for topical therapy only were less common in patients with severe disease than in patients with clear-to-mild disease (34.4% vs. 65.6%; p<.0001). Similarly, prescriptions and in-office administration of systemic therapies were more common in patients with moderate (28.8%) and severe (61.3%) than in patients with clear-to-mild disease (17.3%; p<.001). This difference was most pronounced in biologics, where written prescriptions ranged from 11.7% of patients with clear-to-mild disease to 43.5% of patients with severe disease (p<.05).

Treatments observed in claims

Discrepancies were found between written prescriptions for systemic therapies in the de-identified data from EMA and filled prescriptions observed in PharMetrics Plus (). While only 17.2% of patients had a written order for systemic therapy in EMA, 40.6% of patients had a claim for a systemic therapy. This discrepancy appears to be driven by systemic steroids which were observed more frequently in claims than in EMA (36.4% vs. 10.2%).

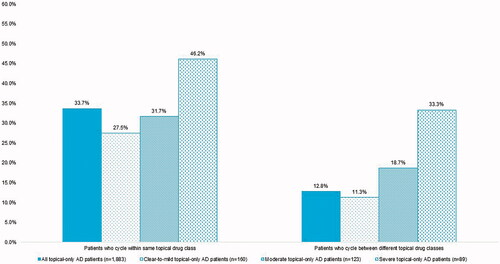

Among the 1,883 patients who had claims for topical therapies alone, 80.7% used topical corticosteroids only while 14.6% had claims for multiple topical therapy drug classes (). On average, patients used 1.6 (0.8) unique topical therapies in 2018. Cycling between topical therapies in the same drug class was observed in 33.7% of patients and between topical class cycling was observed in 12.8% of patients (). A lower proportion of patients with severe disease used only topical therapy in 2018 than patients with clear-to-mild disease (21.0% vs. 39.0%; p<.0001). Use of multiple topical therapy classes was more common in patients with severe disease than clear-to-mild disease (33.3% vs. 14.4%; p<.01). Likewise, within and between class cycling was more prevalent in patients with severe compared to clear-to-mild disease (46.2% vs. 27.5%; p=.02 and 33.3% vs. 11.3%; p<.001, respectively; ).

Figure 2. Within and between class cycling in patients treated only with topical therapies in 2018, overall and by disease severity.

Table 3. AD treatments dispensed in 2018, overall and stratified by baseline disease severity.

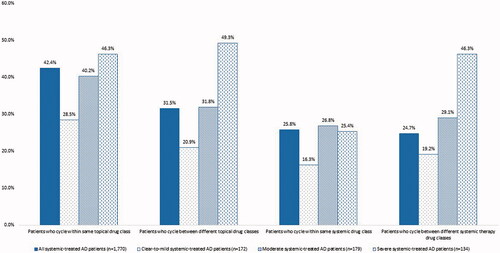

A total of 1,770 patients had claims for systemic therapy in 2018, of which 84.9% also had claims for topical therapy while 15.1% used only systemic therapies (). Use of systemic therapy, with or without topical therapy, increased with severity. Nearly 42.0% of patients with clear-to-mild disease used systemic therapy, compared to 50.6% of patients with moderate disease (p=.02) and 72.0% of patients with severe disease (p<.0001). Use of oral immunosuppressants and biologics was higher in patients with severe disease than patients with clear-to-mild disease (19.4% vs. 8.1%; p<.01 and 44.8% vs. 27.3%; p<.01, respectively). On average, patients who used systemic therapy, had 2.0 (1.1) unique topical and 1.5 (0.7) unique systemic agents. Cycling within and between topical therapy drug classes appeared more common in patients who used systemic and topical therapy compared to those who used topical therapy alone (). Overall, 42.4% of patients who used systemic therapy cycled within the same topical therapy drug class, while 31.5% cycled between topical therapy drug classes. Roughly a quarter of patients treated with systemic therapies had within and between systemic therapy drug class cycling in 2018. Similar to topical only users, patients with severe disease more commonly cycled within and between topical therapy drug classes (46.3% vs. 28.5%; p=.001 and 49.3% vs. 20.9%; p<.0001). Cycling within and between systemic drug classes was also more common in patients with moderate (26.8% vs. 16.3%; p=.02 and 29.1% vs. 19.2%; p=.03) and severe (25.4% vs. 16.3%; p<.05 and 46.3% vs. 19.2%; p<.0001) disease than in patients with clear-to-mild disease.

Figure 3. Within and between class cycling in patients treated with systemic therapies in 2018, overall and by disease severity.

Among all systemic treatment users (n = 1,770), corticosteroids were the most frequently (89.7%) used systemic therapy observed in claims during 2018 with an average of 1.3 (0.6) unique agents used. Despite the common use of systemic steroids in these patients, treatment was brief, with a mean (SD) PDC of 0.1 (0.1) and an average of 343.3 (34.3) days with no systemic steroid drug coverage during the observation period. Biologic use was observed in 16.8% of patients who used systemic therapy, with a mean (SD) PDC of 0.5 (0.3) and mean (SD) number of days with no biologic drug coverage of 199.5 (113.0) day ().

In total 711 (16.3%) patients did not have claims for topical or systemic therapy agents in 2018; 20 (0.5%) received other AD-related treatments, including topical retinoids (0.2%), topical vitamin D3 analogues (0.1%), and phototherapy (0.2%) ().

Concomitant medication use generally aligned with the comorbidity profile of our patient population (). The most commonly observed medications were antibiotics (37.4%) followed by antidepressants/anti-anxiety drugs (30.3%). Roughly 11% of patients used antivirals, 10.1% of patients used pain medications, 9.7% used antifungals, and 3.9% used sleep aids. A higher proportion of patients with severe disease used asthma medications compared to patients with clear-to-mild disease (51.1% vs. 24.6%; p<.0001). Antidepressant/anti-anxiety drug use was more common in patients with moderate and severe disease than in patients with mild disease (35.0% vs. 25.1%; p<.01 and 39.3% vs. 25.1%; p<.001, respectively).

Table 4. Concomitant medication use observed in 2018, overall and by disease severity.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to provide a current assessment of the treatment landscape for adult atopic dermatitis in the United States, overall and by disease severity. To our knowledge, this is the first study to report on the comprehensive adult AD market landscape after approval of dupilumab. Results were reported overall, and by disease severity which was defined using a clinical measure of severity rather than a proxy based on treatments. The strength of the current study lies in the use of PGA to determine disease severity, whereas other studies in AD proxy severity based on initiation of systemic therapy. Our study shows that there are some patients with mild disease who use systemic therapy; other studies of moderate-to-severe AD may be including patients with mild disease who use systemic therapy to treat a flare. Similarly, we found patients with severe disease who are not currently using systemic therapy – patients who would not be included in the study had we used a treatment-based proxy.

According to the American Academy of Dermatology (ADD), systemic corticosteroids should only be used for acute severe exacerbations or as a bridge therapy to other systemic, steroid-sparing treatments. Despite AAD guidelines recommending avoiding systemic steroids due to toxicity (Citation8), nearly 90% of patients who had systemic therapy were treated with corticosteroids. Minimal PDC suggests systemic steroids were chosen to quickly clear AD and possibly treat flares rather than used as a maintenance therapy.

Biologic use was observed in 17% of patients who were treated with systemic therapy in 2018 and was primarily used by patients with severe disease, which is comparable to results published in a prior study of patients with AD using systemic treatment that was conducted using PharMetrics data. Eichenfield and colleagues (Citation13) reported that 21.0% of patients who newly initiated systemic therapy (including phototherapy) used dupilumab during the follow-up period which ended on July 31, 2018. Unlike the Eichenfield study, the current study focused on adult patients and included all patients diagnosed with AD, not just those who newly initiated systemic treatment.

Use of multiple topical and systemic therapies, as well as cycling within and between both topical and systemic drug classes were more common in patients with more severe disease, indicating the difficulty of managing these patients and highlighting a need for more treatment options. Particularly, the higher cycling within and between topical drug classes among severe patients may point to limited options of AD-indicated systemic treatments. Coupled with safety concerns for many systemic treatments, this might preclude patients from initiating a more aggressive therapy. As the treatment landscape continues to evolve, future studies investigating the physician and patient thoughts around treatment strategy, with a focus on reasons for the limited use of systemics in general, and biologics in particular, are warranted.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the data used in this study were not collected for research purposes and only a small proportion of patients had the necessary severity measures available to assess disease severity. These gaps in data may limit the generalizability to the entire adult AD population, particularly if patients with the available data have more active or severe disease than patients with no measures available. Furthermore, although the PGA is considered the gold-standard clinical assessment tool (Citation15), it is not commonly used in clinical practice and has not been validated in any setting (Citation4). As such, health care providers do not always interpret PGA severities the same way and are not trained it its use, limiting cross-study comparisons. A systematic review of Investigator Global Assessment (IGA; also known as PGA in clinical practice) in AD trials revealed that although global assessment measures are frequently used in clinical trials to measure treatment response, there is a lack of standardization and implementation across studies (Citation15). Finally, to minimize the risk of re-identification of patients with linkage between EMR and claims data, dates in each database were independently randomly shifted by ± 15 days, which added a level of uncertainty around dates of disease assessments, therapies ordered in EMATM and treatments received by patients in PharMetrics Plus.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (77.4 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Wei-Ti Huang and Yiyun Lin from IQVIA for their programming and statistical expertise.

Disclosure statement

At the time of this study, NB, WM, and OG were full time employees and stockholders of Eli Lilly and Company. For NB and OG, author affiliation has changed since the time this research was conducted. Assigned affiliation is the institution of employment at the time the research was conducted. MG, XW, and RW were employees of IQVIA, Inc., which received funding from Eli Lilly and Company to carry out the study.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bieber T. Atopic dermatitis. Ann Dermatol. 2010;22(2):125–137.

- Al-Naqeeb J, Danner S, Fagnan LJ, et al. The burden of childhood atopic dermatitis in the primary care setting: a report from the Meta-LARC consortium. J Am Board Fam Med. 2019;32(2):191–200.

- Silverberg, JI. Atopic dermatitis in adults. Med Clin 2020;104(1):157–176

- Boguniewicz M, Fonacier L, Guttman-Yassky E, et al. Atopic dermatitis yardstick: practical recommendations for an evolving therapeutic landscape. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;120(1):10–22.e2.

- Dhadwal G, Albrecht L, Gniadecki R, et al. Approach to the assessment and management of adult patients with atopic dermatitis: a consensus document. Section IV: treatment options for the management of atopic dermatitis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2018; 22(1_suppl):21S–29S.

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Berger TG, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis. Section 2. Management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(1):116–132.

- Yang H, Wang J, Shang X, et al. Application of topical phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors in mild to moderate atopic dermatitis – a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155(5):585–593.

- Sidbury R, Davis DM, Cohen DE, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis. Section 3. Management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(2): 327–349.

- Frampton JE and Blair HA. Duplimumab: a review in moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:617–624.

- Feldman SR, Cox LS, Strowd LC, et al. The challenge of managing atopic dermatitis in the United States. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2019;12(2):83–93.

- Cohen DE. New and emerging therapies for atopic dermatitis. Presented at the 2019 American Academy of Dermatology Annual Meeting; 2019 March 1-5; Washington, DC.

- Armstrong AW, Huang A, Wang L, et al. Real-world utilization patterns of systemic immunosuppressants among US adult patients with atopic dermatitis. PLoS One. 2019;14(1):e0210517.

- Eichenfield LF, DiBonaventura M, Xenakis J, et al. Costs and treatment patterns among patients with atopic dermatitis using advanced therapies in the United States: analysis of a retrospective claims database. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2020;10(4):791–806.

- Gooderham MJ, Bissonnette R, Grewal P, et al. Approach to the assessment and management of adult patients with atopic dermatitis: a consenus document. Section II: tools for assessing the severity of atopic dermatitis. J Cutaneous Med Surg. 2018;22(1S):10S–16S.

- Futamura M, Leshem YA, Thomas KS, et al. A systematic review of investigator global assessment (IGA) in atopic dermatitis (AD) trials: many options, no standards. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;74(2):288–294.