Abstract

Psoriasis is a chronic, immune-mediated disease that includes a broad spectrum of systemic manifestations, complications, and comorbidities. Approximately 20%–30% of patients with psoriasis eventually develop psoriatic arthritis, and up to half of those without psoriatic arthritis experience subclinical musculoskeletal abnormalities. Recognition of early musculoskeletal inflammatory signs in patients with psoriasis is important to understand the extent and severity of this systemic disease, assess the risk of structural joint damage, and ensure timely and effective treatment of the complete spectrum of psoriatic disease. Delayed or ineffective treatment can lead to decreased quality of life, irreversible musculoskeletal damage, and loss of function. In this review, we highlight features of subclinical or early psoriatic arthritis among patients with psoriasis of which dermatologists should be aware. Recent knowledge of features of preclinical psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis is presented. We briefly discuss important risk factors, clinical features, and other characteristics of patients likely to progress from psoriasis to psoriatic arthritis that should be known by dermatologists. Screening tools commonly used in the dermatology clinic to detect psoriatic arthritis are also critically reviewed. Finally, we provide expert commentary for dermatologists concerning the treatment of patients with psoriasis and subclinical signs of early psoriatic arthritis.

Introduction

Psoriasis is a systemic inflammatory disease associated with cutaneous features and a spectrum of potential extracutaneous comorbidities (Citation1,Citation2). Approximately 20% to 30% of patients with psoriasis develop psoriatic arthritis (PsA) (Citation3,Citation4)—a heterogeneous musculoskeletal disease that represents the most common comorbidity and is characterized by peripheral arthritis; enthesitis, characterized by inflammation of sites where tendons or ligaments insert into the bone; dactylitis, or swelling of entire digits; axial disease, characterized by arthritis or enthesitis of the spine, sacroiliac joints, or rib cage; and skin and nail involvement (Citation5). These musculoskeletal inflammatory manifestations share common pathophysiological links to skin disease in psoriasis (Citation6), contribute to disease burden (Citation7–9), and may result in permanent joint remodeling and/or functional disability (Citation3,Citation8,Citation10,Citation11).

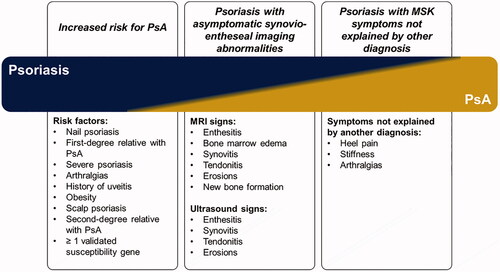

The concept of subclinical PsA was recently introduced as a phase of the progression of psoriatic disease () (Citation12,Citation14). Patients with subclinical PsA have silent joint inflammation and/or morphological changes detectable by diagnostic imaging techniques like ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography, or x-ray, but they do not otherwise fulfill the Classification for Psoriatic Arthritis (CASPAR) Study Group criteria for diagnosis of PsA (Citation14). The continuum of PsA can include patients with psoriasis at increased risk of PsA and those with asymptomatic synovio-entheseal (joint) imaging abnormalities () (Citation12,Citation13). Up to half of all patients with psoriasis may have joint pain, enthesitis, arthralgia, and other musculoskeletal symptoms that may be suggestive but not yet diagnostic of PsA (Citation7,Citation12,Citation15). The impact of subclinical PsA on psoriasis patients’ quality of life and disease burden remains uncharacterized.

Figure 1. Continuum of preclinical phases of PsA (Citation12,Citation13). MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; MSK: musculoskeletal; PsA: psoriatic arthritis.

Appropriate and timely diagnosis and treatment of PsA is known to result in improved patient outcomes (Citation16,Citation17), and prolonged inflammation increases the risk of structural damage to joints (Citation10,Citation18). Modern treatments may inhibit progression of psoriatic disease including radiographic changes to the joints, control signs and symptoms across the spectrum of disease manifestations, and improve quality of life (Citation19,Citation20). Early detection and treatment of PsA, including the subclinical phase, may attenuate negative outcomes.

Dermatologists have a considerable opportunity to identify the earliest signs of PsA in patients with psoriasis. Undiagnosed PsA is prevalent in dermatology clinics (Citation21,Citation22) and has been identified in up to 30% of patients with psoriasis (Citation22–26). In 1 study, 41% of patients with psoriasis in whom PsA was identified by rheumatologists were not previously diagnosed by their dermatologists (Citation23). This review will provide dermatologists with updated information and expert commentary concerning the identification and treatment of patients with psoriasis who are at risk of developing PsA or who may already be experiencing subclinical signs of early PsA.

Features of subclinical PsA in patients with psoriasis

Subclinical musculoskeletal symptoms indicative of early PsA have been found to be widespread among patients with psoriasis who do not have a diagnosis of PsA (Citation7,Citation15). Imaging modalities have recently identified the presence of inflammation consistent with subclinical PsA in a large proportion of patients with psoriasis not receiving systemic therapies (Citation27–33).

Ultrasonography can detect entheseal abnormalities of PsA with greater sensitivity than clinical observation in patients with early PsA (Citation34). Detection of preclinical inflammatory changes may prognosticate development of PsA (Citation32,Citation35). For example, a prospective cohort study found that patients with psoriasis and no diagnosis of PsA were significantly more likely to have synovitis (50.7% vs 32.6%; p = .024) and enthesopathy (62.5% vs 39.1%; p = .005) detected by ultrasonography than were healthy controls (Citation29). Psoriasis was the only baseline variable predictive of ultrasonography-detectable synovitis (odds ratio [OR] = 2.1; p = .007) and enthesopathy (OR = 2.6; p = .027) (Citation29). Nail ultrasonography can identify changes to the thickness of the nail bed and plate among patients with psoriasis and PsA (Citation36). Specific nail features have been identified using ultrasonography in patients with psoriasis and PsA. These include loss of integrity of the ventral plate beyond the matrix and/or involvement of both the dorsal and ventral plate (Citation36). Thickening of the nail plate among patients with psoriatic disease may be less than the diffuse thickening observed in onychomycosis (Citation37). Importantly, the presence of nail disease is associated with enthesopathy at remote locations in the lower limbs (Citation38).

MRI of the hands and feet can be useful for detection of peripheral arthritis features in PsA (Citation39,Citation40). Although not validated in peripheral joints as a diagnostic tool for early PsA, MRI has identified subclinical PsA abnormalities present among patients with psoriasis (Citation30,Citation41). For example, inflammation of the small joints of the feet detected by MRI in patients with psoriasis was significantly associated with an Early Arthritis for Psoriatic Patients (EARP) screening questionnaire score ≥ 3 (p = .04) (Citation41), which is recognized as the lower cutoff for early PsA (Citation42). MRI is even more important for diagnosis of early axial PsA because inflammatory lesions are evident by MRI before structural changes are visible by classical radiography (Citation43). For diagnosing axial disease with MRI, the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (formerly European League Against Rheumatism) recommends imaging the sacroiliac joints (Citation43). Useful MRI approaches for detecting peripheral and axial PsA are shown in .

Table 1. Summary of MRI and classical radiography for the identification of PsA-associated changes to peripheral and axial joints.

Classical radiography remains useful in diagnosing advanced PsA upon appearance of joint space narrowing and bone erosions () (Citation44). However, PsA should ideally be identified prior to the development of radiographic changes to the joints, which are frequently not detected in early PsA. Bone scintigraphy may detect subclinical joint involvement in patients with psoriasis but without clinical arthropathy (Citation45).

Musculoskeletal changes visible upon imaging are also linked to symptoms felt by patients. Manifestations of nonspecific or vague symptoms such as pain and fatigue have been associated with the development of PsA among patients with psoriasis (Citation12), and up to half of all patients experience joint pain and inflammation (Citation7,Citation15). Subclinical changes to the joints likely characterize a distinct point on the continuum of psoriatic disease. Because ultrasonography and MRI are still considered research tools for detecting subclinical PsA, except in the case of axial disease, additional studies are needed to confirm the utility of these techniques for detecting subclinical PsA in routine clinical practice.

Clinical features and risk factors associated with the development of PsA from psoriasis: what dermatologists should know

Risk factors for the development of PsA from psoriasis—including measures of disease activity, biomarkers, and patient history—have been reviewed extensively (Citation8,Citation46–48), and a subset of these are particularly important for dermatologists to understand () (Citation12,Citation49–53). Some features of psoriatic disease increase the risk of developing PsA. Psoriasis location, including inverse psoriasis, scalp psoriasis, and nail psoriasis, have been associated with an increased likelihood of developing PsA (Citation49,Citation54). Nail psoriasis is a well-characterized risk factor for the development of PsA, and dermatologists should be aware of early nail changes, including pitting, onycholysis, subungual hyperkeratosis, and oil spots as potential signs of early PsA (Citation55,Citation56). An anatomical relationship exists between the nail matrix and the enthesis of the distal interphalangeal joint extensor; this may explain correlations between nail disease and enthesitis (Citation57). The prevalence of nail disease has been found to be higher in patients with PsA than in patients with psoriasis (≤80% vs <50%, respectively) (Citation57,Citation58). In a systematic literature review, distal interphalangeal joint arthritis was found to be associated with nail psoriasis (Citation59). In this study, a meta-analysis identified a trend for increased risk of PsA with a higher Psoriasis Area and Severity Index score (Citation59). PsA can occur even in patients with mild psoriasis, although patients with more severe disease are more likely to develop PsA () (Citation49,Citation52). For example, higher body surface area affected by psoriasis has been associated with increased risk of developing PsA (OR = 2.52) (Citation52).

Table 2. Summary of risk factors of subclinical PsA or progression to PsA among patients with psoriasis.

Patient history and background characteristics—including genetic factors, obesity, and metabolic syndrome—have been linked to the development of PsA among patients with psoriasis (Citation60–62). PsA is a heritable disease with strong familial aggregation (Citation63,Citation64), and the presence of PsA in a first-degree relative is the most important predictive factor for the development of PsA among patients with psoriasis (Citation52). A population-based cohort study from the Icelandic genealogy database found that first-degree relatives of patients with PsA are 39 times more likely to develop PsA than those with no family history (p < .0001) (Citation64).

Enthesitis is one of the strongest clinical signs coinciding with the development of PsA from psoriasis (Citation65,Citation66). A recent prospective cohort study of patients with psoriasis and no clinical evidence of musculoskeletal involvement found that structural enthesitis, as detected by high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography, is associated with progression from psoriasis to PsA (Citation67). Dermatologists should ask patients about joint pain and be aware of this risk factor throughout treatment. The presence of enthesitis at particular locations has been found to be characteristic of PsA; dermatologists should be familiar with musculoskeletal pain or tenderness manifesting at the lateral epicondyle, quadriceps insertion, patellar tendon, Achilles tendon, and plantar fascia (Citation65,Citation68,Citation69). Because inflammatory back pain is present in axial PsA (Citation70), patients with psoriasis presenting with either inflammatory lower back pain or cervical spinal pain should be evaluated for PsA.

There are currently no validated, clinically available biomarkers detectable in the serum or synovial fluid that are specific to PsA (Citation71). HLA-B27 status is generally not considered useful, except when axial PsA is suspected (Citation70). The majority of patients with PsA have normal levels of the inflammatory marker C-reactive protein (CRP) or a normal erythrocyte sedimentation rate (Citation72). However, elevated CRP has been correlated with worse prognosis and increased radiographic damage in patients with PsA (Citation73) and is found in patients with psoriasis that progresses to PsA (Citation27). Therefore, it may be useful to monitor CRP levels if a patient with psoriasis has a high CRP at baseline. More specific biomarkers for PsA are needed.

Identification of PsA in patients with psoriasis

Recognition of earlier signs of progression from psoriasis to PsA is important to ensure that patients receive timely and effective treatment for PsA. Dermatologists should ideally screen all patients with psoriasis at each visit for manifestations of PsA, including arthritis, dactylitis, enthesitis, nail disease, and spondylitis (Citation74).

Screening tools developed for use in the dermatology clinic to identify PsA in patients with psoriasis may be helpful in identifying early PsA; these include the Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool (PEST) (Citation75), the Psoriatic Arthritis Screening and Evaluation (PASE) (Citation76), and the Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Screen (ToPAS) (Citation77), updated ToPAS II (Citation78), EARP (Citation42), and CONTEST questionnaires (Citation79). Each of these instruments has strengths and weaknesses () (Citation42,Citation75–85). A systematic review and meta-analysis of 14 different screening tools used across 27 studies found that the EARP questionnaire has a slightly higher accuracy than the ToPAS, PEST, and PASE tools (Citation86). Of the validated screening tools, only PEST is available without charge. A mnemonic to help guide dermatologists when taking history and to quickly assess PsA characteristics is ‘PsA’: Pain in the joints, Stiffness > 30 min after inactivity/dactylitis (Sausage digit/Swelling), and Axial spine involvement/back pain and stiffness that improves with activity (Citation83).

Table 3. Summary of current screening tools for PsA in patients with psoriasis.

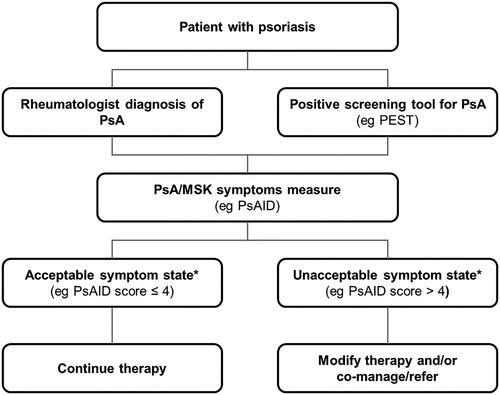

The International Dermatology Outcome Measures (IDEOM) Musculoskeletal Symptoms Workgroup is actively studying measurement of musculoskeletal symptoms and has recently proposed a framework for the clinical identification of musculoskeletal symptoms in patients with psoriasis, which includes arms for rheumatologist-identified PsA as well as PsA identified by the EARP () (Citation87). Further, IDEOM is addressing the unmet need for a patient-reported outcome for early PsA by developing a novel outcome measure to assess musculoskeletal symptoms and their impacts among psoriasis patients without a known diagnosis of PsA (Citation87).

Figure 2. Proposed framework for the clinical identification of MSK symptoms in patients with psoriasis (Citation87). IDEOM: International Dermatology Outcome Measures; MSK: musculoskeletal; PEST: Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool; PsA: psoriatic arthritis; PsAID: Psoriatic Arthritis Impact of Disease. *Based on validated cutoff values for patient acceptable symptoms state. Reprinted with permission from The Journal of Rheumatology, Perez-Chada LM, et al. Report of the Skin Research Working Groups From the GRAPPA 2020 Annual Meeting. J Rheumatol. 2021;jrheum.201668. All Rights reserved.

Expert commentary: dermatologists are important in treating the spectrum of psoriatic disease

With psoriasis, clinicians have the opportunity to identify strategies for diagnosing PsA and to possibly contribute to its prevention by treating the common root cause of psoriatic disease: systemic inflammation. Several systemic therapies have been approved for both psoriasis and PsA (Citation20). Both the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology and Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis recommend early intervention with therapeutics efficacious in affected PsA domains (Citation20,Citation88). US Food and Drug Administration–approved biologics that inhibit radiographic progression and control signs and symptoms include tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFis) and interleukin (IL)-17A inhibitors (Citation20,Citation88–91). However, many dermatologists see patients with psoriasis without a diagnosis of PsA who experience improved mobility, quality of life, or other features of PsA disease activity after initiating treatments that are efficacious in both diseases. Those patients who experience improvements in musculoskeletal symptoms upon treatment with systemic therapies with efficacy across the spectrum of psoriatic disease may indeed have preclinical or undiagnosed PsA and would benefit from continued treatment for PsA.

The concept of disease interception was recently introduced (Citation92). One hypothesis considers the possibility of arresting progression of psoriasis to PsA by targeting cytokines common to the pathogenesis of both diseases. Although much evidence exists for the use of biologics and other systemic therapies in the treatment of both psoriasis and PsA, insufficient evidence exists to suggest that reduction in inflammation by these systemic agents may slow or arrest the development of PsA from psoriasis. Studies are underway to examine this link. One recent cohort study found that systemic therapies for psoriasis may indeed reduce the incidence of PsA progression—especially the manifestation of dactylitis—compared with topical therapies among patients with psoriasis (Citation93). In the Interception in Very Early PsA (IVEPSA) study, the anti–IL-17A antibody secukinumab arrested the progression of joint symptoms in patients with psoriasis, subclinical inflammatory changes, and arthralgia (Citation92,Citation94). Suppression of the IL-23/IL-17 axis with the IL-12/23 inhibitor ustekinumab reduced subclinical enthesopathy from 12 to ≥52 weeks of treatment in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis who had ≥1 entheseal change detected by ultrasonography and no diagnosis of PsA (Citation95). In a recent cohort study, patients with psoriasis treated with TNFis had no decreased risk of developing PsA vs patients who received methotrexate (Citation96). Thus, early treatment with specific biologics may be necessary to intercept the progression of PsA.

Summary

Subclinical musculoskeletal changes among patients with psoriasis are a sign of risk for the development of PsA. These changes may be a useful indicator of how systemic inflammation is affecting more than the skin, and awareness should be widespread among the dermatology community. Fortunately, dermatologists are uniquely positioned to identify early musculoskeletal changes among patients with psoriasis. Early intervention with systemic therapies efficacious in both psoriasis and PsA may help patients with subclinical signs of PsA or early PsA realize improved outcomes. It is advisable for dermatologists to become comfortable with treatment using agents effective in PsA or refer patients with suspected PsA to rheumatologists for subsequent diagnosis and treatment.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Richard Karpowicz, PhD, of Health Interactions, Inc, Hamilton, NJ, USA, for providing medical writing support/editorial support, which was funded by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, East Hanover, NJ, in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines (http://www.ismpp.org/gpp3).

Disclosure statement

Dr Gottlieb has received honoraria as an advisory board member and/or consultant for AnaptysBio, Avotres Therapeutics, Beiersdorf, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Incyte, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Sun Pharmaceutical, UCB, and XBiotech (only stock options, which she has not used) and has received research/educational grants from Boehringer Ingelheim, Incyte, Janssen, Novartis, UCB, XBiotech, and Sun Pharmaceutical. Dr Merola is a consultant and/or investigator for Merck, Bristol Myers Squibb, AbbVie, Dermavant, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Janssen, UCB, Celgene, Sanofi, Regeneron, Arena, Sun Pharmaceutical, Biogen, Pfizer, EMD Sorono, Avotres Therapeutics, and LEO Pharma.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Carvalho AV, Romiti R, Souza CD, et al. Psoriasis comorbidities: complications and benefits of immunobiological treatment. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91(6):781–789.

- Menter A, Strober BE, Kaplan DH, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(4):1029–1072.

- Gottlieb A, Korman NJ, Gordon KB, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: Section 2. Psoriatic arthritis: overview and guidelines of care for treatment with an emphasis on the biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(5):851–864.

- Alinaghi F, Calov M, Kristensen LE, et al. Prevalence of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational and clinical studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(1):251–265.e19.

- Ritchlin CT, Colbert RA, Gladman DD. Psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(21):2095–2096.

- Krueger JG, Brunner PM. Interleukin-17 alters the biology of many cell types involved in the genesis of psoriasis, systemic inflammation and associated comorbidities. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27(2):115–123.

- Kavanaugh A, Helliwell P, Ritchlin CT. Psoriatic arthritis and burden of disease: patient perspectives from the population-based Multinational Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (MAPP) Survey. Rheumatol Ther. 2016;3(1):91–102.

- Gladman DD, Antoni C, Mease P, et al. Psoriatic arthritis: epidemiology, clinical features, course, and outcome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(Suppl 2):ii14–ii17.

- Merola JF, Herrera V, Palmer JB. Direct healthcare costs and comorbidity burden among patients with psoriatic arthritis in the USA. Clin Rheumatol. 2018;37(10):2751–2761.

- Haroon M, Gallagher P, FitzGerald O. Diagnostic delay of more than 6 months contributes to poor radiographic and functional outcome in psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(6):1045–1050.

- Moll JM, Wright V. Psoriatic arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1973;3(1):55–78.

- Eder L, Polachek A, Rosen CF, et al. The development of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis is preceded by a period of nonspecific musculoskeletal symptoms: a prospective cohort study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69(3):622–629.

- Haberman R, Perez-Chada L, Chandran V, et al. A Delphi consensus study to standardize terminology for the pre-clinical phase of psoriatic arthritis. Presented at the American College of Rheumatology Convergence 2020. Poster #0305.

- Scher JU, Ogdie A, Merola JF, et al. Preventing psoriatic arthritis: focusing on patients with psoriasis at increased risk of transition. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2019;15(3):153–166.

- Lebwohl MG, Kavanaugh A, Armstrong AW, et al. US perspectives in the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: patient and physician results from the Population-Based Multinational Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (MAPP) Survey. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17(1):87–97.

- Kirkham B, de Vlam K, Li W, et al. Early treatment of psoriatic arthritis is associated with improved patient-reported outcomes: findings from the etanercept PRESTA trial. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2015;33(1):11–19.

- Ogdie A, Nowell WB, Applegate E, et al. Patient perspectives on the pathway to psoriatic arthritis diagnosis: results from a web-based survey of patients in the United States. BMC Rheumatol. 2020;4:2.

- Menon B, Gullick NJ, Walter GJ, et al. Interleukin-17 + CD8+ T cells are enriched in the joints of patients with psoriatic arthritis and correlate with disease activity and joint damage progression. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(5):1272–1281.

- Coates LC, Gossec L, Ramiro S, et al. New GRAPPA and EULAR recommendations for the management of psoriatic arthritis. Rheumatology. 2017;56(8):1251–1253.

- Gossec L, Baraliakos X, Kerschbaumer A, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of psoriatic arthritis with pharmacological therapies: 2019 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79(6):700–712.

- Radtke MA, Reich K, Blome C, et al. Prevalence and clinical features of psoriatic arthritis and joint complaints in 2009 patients with psoriasis: results of a German national survey. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(6):683–691.

- Haroon M, Kirby B, FitzGerald O. High prevalence of psoriatic arthritis in patients with severe psoriasis with suboptimal performance of screening questionnaires. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(5):736–740.

- Mease PJ, Gladman DD, Papp KA, et al. Prevalence of rheumatologist-diagnosed psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis in European/North American dermatology clinics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(5):729–735.

- Villani AP, Rouzaud M, Sevrain M, et al. Prevalence of undiagnosed psoriatic arthritis among psoriasis patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(2):242–248.

- Reich K, Krüger K, Mössner R, et al. Epidemiology and clinical pattern of psoriatic arthritis in Germany: a prospective interdisciplinary epidemiological study of 1511 patients with plaque-type psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160(5):1040–1047.

- Mease PJ, Palmer JB, Hur P, et al. Utilization of the validated Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool to identify signs and symptoms of psoriatic arthritis among those with psoriasis: a cross-sectional analysis from the US-based Corrona Psoriasis Registry. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(5):886–892.

- Elnady B, El Shaarawy NK, Dawoud NM, et al. Subclinical synovitis and enthesitis in psoriasis patients and controls by ultrasonography in Saudi Arabia; incidence of psoriatic arthritis during two years. Clin Rheumatol. 2019;38(6):1627–1635.

- Acquitter M, Misery L, Saraux A, et al. Detection of subclinical ultrasound enthesopathy and nail disease in patients at risk of psoriatic arthritis. Joint Bone Spine. 2017;84(6):703–707.

- Naredo E, Möller I, de Miguel E, et al. High prevalence of ultrasonographic synovitis and enthesopathy in patients with psoriasis without psoriatic arthritis: a prospective case-control study. Rheumatology. 2011;50(10):1838–1848.

- Faustini F, Simon D, Oliveira I, et al. Subclinical joint inflammation in patients with psoriasis without concomitant psoriatic arthritis: a cross-sectional and longitudinal analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(12):2068–2074.

- Acquacalda E, Albert C, Montaudie H, et al. Ultrasound study of entheses in psoriasis patients with or without musculoskeletal symptoms: a prospective study. Joint Bone Spine. 2015;82(4):267–271.

- Tinazzi I, McGonagle D, Biasi D, et al. Preliminary evidence that subclinical enthesopathy may predict psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis. J Rheumatol. 2011;38(12):2691–2692.

- Gutierrez M, Filippucci E, De Angelis R, et al. Subclinical entheseal involvement in patients with psoriasis: an ultrasound study. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011;40(5):407–412.

- Perrotta FM, Astorri D, Zappia M, et al. An ultrasonographic study of enthesis in early psoriatic arthritis patients naive to traditional and biologic DMARDs treatment. Rheumatol Int. 2016;36(11):1579–1583.

- El Miedany Y, El Gaafary M, Youssef S, et al. Tailored approach to early psoriatic arthritis patients: clinical and ultrasonographic predictors for structural joint damage. Clin Rheumatol. 2015;34(2):307–313.

- Naredo E, Janta I, Baniandres-Rodriguez O, et al. To what extend is nail ultrasound discriminative between psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis and healthy subjects? Rheumatol Int. 2019;39(4):697–705.

- Aluja Jaramillo F, Quiasúa Mejía DC, Martínez Ordúz HM, et al. Nail unit ultrasound: a complete guide of the nail diseases. J Ultrasound. 2017;20(3):181–192.

- Ash ZR, Tinazzi I, Gallego CC, et al. Psoriasis patients with nail disease have a greater magnitude of underlying systemic subclinical enthesopathy than those with normal nails. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(4):553–556.

- Glinatsi D, Bird P, Gandjbakhch F, et al. Validation of the OMERACT Psoriatic Arthritis Magnetic Resonance Imaging Score (PsAMRIS) for the hand and foot in a randomized placebo-controlled trial. J Rheumatol. 2015;42(12):2473–2479.

- Ostergaard M, McQueen F, Wiell C, et al. The OMERACT psoriatic arthritis magnetic resonance imaging scoring system (PsAMRIS): definitions of key pathologies, suggested MRI sequences, and preliminary scoring system for PsA Hands. J Rheumatol. 2009;36(8):1816–1824.

- Mathew AJ, Bird P, Gupta A, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of feet demonstrates subclinical inflammatory joint disease in cutaneous psoriasis patients without clinical arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2018;37(2):383–388.

- Tinazzi I, Adami S, Zanolin EM, et al. The early psoriatic arthritis screening questionnaire: a simple and fast method for the identification of arthritis in patients with psoriasis. Rheumatology. 2012;51(11):2058–2063.

- Mandl P, Navarro-Compan V, Terslev L, et al. EULAR recommendations for the use of imaging in the diagnosis and management of spondyloarthritis in clinical practice. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(7):1327–1339.

- Sudoł-Szopińska I, Matuszewska G, Kwiatkowska B, et al. Diagnostic imaging of psoriatic arthritis. Part I: etiopathogenesis, classifications and radiographic features. J Ultrason. 2016;16(64):65–77.

- Raza N, Hameed A, Ali MK. Detection of subclinical joint involvement in psoriasis with bone scintigraphy and its response to oral methotrexate. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33(1):70–73.

- Catanoso M, Pipitone N, Salvarani C. Epidemiology of psoriatic arthritis. Reumatismo. 2012;64(2):66–70.

- Ogdie A, Gelfand JM. Clinical risk factors for the development of psoriatic arthritis among patients with psoriasis: a review of available evidence. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2015;17(10):64.

- Busse K, Liao W. Which psoriasis patients develop psoriatic arthritis? Psoriasis Forum. 2010;16(4):17–25.

- Wilson FC, Icen M, Crowson CS, et al. Incidence and clinical predictors of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61(2):233–239.

- Soltani-Arabshahi R, Wong B, Feng BJ, et al. Obesity in early adulthood as a risk factor for psoriatic arthritis. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146(7):721–726.

- Eder L, Haddad A, Rosen CF, et al. The incidence and risk factors for psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: a prospective cohort study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(4):915–923.

- Tey HL, Ee HL, Tan AS, et al. Risk factors associated with having psoriatic arthritis in patients with cutaneous psoriasis. J Dermatol. 2010;37(5):426–430.

- Gottlieb A, Merola JF. Psoriatic arthritis for dermatologists. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31(7):662–679.

- Patrizi A, Venturi M, Scorzoni R, et al. Nail dystrophies, scalp and intergluteal/perianal psoriatic lesions: risk factors for psoriatic arthritis in mild skin psoriasis? G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2014;149(2):177–184.

- Castellanos-Gonzalez M, Joven BE, Sanchez J, et al. Nail involvement can predict enthesopathy in patients with psoriasis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016;14(11):1102–1107.

- Langenbruch A, Radtke MA, Krensel M, et al. Nail involvement as a predictor of concomitant psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171(5):1123–1128.

- Sobolewski P, Walecka I, Dopytalska K. Nail involvement in psoriatic arthritis. Reumatologia. 2017;55(3):131–135.

- Raposo I, Torres T. Nail psoriasis as a predictor of the development of psoriatic arthritis. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015;106(6):452–457.

- Rouzaud M, Sevrain M, Villani AP, et al. Is there a psoriasis skin phenotype associated with psoriatic arthritis? Systematic literature review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28(Suppl 5):17–26.

- Eder L, Chandran V, Gladman DD. What have we learned about genetic susceptibility in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis? Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2015;27(1):91–98.

- Oliveira MF, Rocha BO, Duarte GV. Psoriasis: classical and emerging comorbidities. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90(1):9–20.

- Husted JA, Thavaneswaran A, Chandran V, et al. Cardiovascular and other comorbidities in patients with psoriatic arthritis: a comparison with patients with psoriasis. Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63(12):1729–1735.

- Chandran V, Schentag CT, Brockbank JE, et al. Familial aggregation of psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(5):664–667.

- Karason A, Love TJ, Gudbjornsson B. A strong heritability of psoriatic arthritis over four generations–the Reykjavik Psoriatic Arthritis Study. Rheumatology. 2009;48(11):1424–1428.

- Belasco J, Wei N. Psoriatic arthritis: what is happening at the joint? Rheumatol Ther. 2019;6(3):305–315.

- Coates LC, Helliwell PS. Psoriatic arthritis: state of the art review. Clin Med. 2017;17(1):65–70.

- Simon D, Tascilar K, Kleyer A, et al. Structural entheseal lesions in patients with psoriasis are associated with an increased risk of progression to psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020;2020:41239.

- McGonagle DG, Helliwell P, Veale D. Enthesitis in psoriatic disease. Dermatology. 2012;225(2):100–109.

- Poggenborg RP, Eshed I, Ostergaard M, et al. Enthesitis in patients with psoriatic arthritis, axial spondyloarthritis and healthy subjects assessed by ‘head-to-toe’ whole-body MRI and clinical examination. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(5):823–829.

- Feld J, Chandran V, Haroon N, et al. Axial disease in psoriatic arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis: a critical comparison. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2018;14(6):363–371.

- Generali E, Scirè CA, Favalli EG, et al. Biomarkers in psoriatic arthritis: a systematic literature review. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2016;12(6):651–660.

- Punzi L, Poswiadek M, Oliviero F, et al. Laboratory findings in psoriatic arthritis. Reumatismo. 2011;59(1s):52–55.

- van der Heijde D, Gladman DD, FitzGerald O, et al. Radiographic progression according to baseline C-reactive protein levels and other risk factors in psoriatic arthritis treated with tofacitinib or adalimumab. J Rheumatol. 2019;46(9):1089–1096.

- Bagel J, Schwartzman S. Enthesitis and dactylitis in psoriatic disease: a guide for dermatologists. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19(6):839–852.

- Ibrahim GH, Buch MH, Lawson C, et al. Evaluation of an existing screening tool for psoriatic arthritis in people with psoriasis and the development of a new instrument: the Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool (PEST) questionnaire. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2009;27(3):469–474.

- Husni ME, Meyer KH, Cohen DS, et al. The PASE questionnaire: pilot-testing a psoriatic arthritis screening and evaluation tool. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(4):581–587.

- Gladman DD, Schentag CT, Tom BD, et al. Development and initial validation of a screening questionnaire for psoriatic arthritis: the Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Screen (ToPAS). Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(4):497–501.

- Tom BD, Chandran V, Farewell VT, et al. Validation of the Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Screen Version 2 (ToPAS 2). J Rheumatol. 2015;42(5):841–846.

- Coates LC, Savage L, Waxman R, et al. Comparison of screening questionnaires to identify psoriatic arthritis in a primary-care population: a cross-sectional study. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175(3):542–548.

- Dominguez PL, Husni ME, Holt EW, et al. Validity, reliability, and sensitivity-to-change properties of the psoriatic arthritis screening and evaluation questionnaire. Arch Dermatol Res. 2009;301(8):573–579.

- Coates LC, Aslam T, Al Balushi F, et al. Comparison of three screening tools to detect psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis (CONTEST study). Br J Dermatol. 2013;168(4):802–807.

- Helliwell PS. Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool (PEST): a report from the GRAPPA 2009 annual meeting. J Rheumatol. 2011;38(3):551–552.

- Cohen JM, Husni ME, Qureshi AA, et al. Psoriatic arthritis: it’s as easy as “PSA”. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72(5):905–906.

- Gossec L, de Wit M, Kiltz U, et al. A patient-derived and patient-reported outcome measure for assessing psoriatic arthritis: elaboration and preliminary validation of the Psoriatic Arthritis Impact of Disease (PsAID) questionnaire, a 13-country EULAR initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(6):1012–1019.

- Pincus T, Yazici Y, Bergman MJ. RAPID3, an index to assess and monitor patients with rheumatoid arthritis, without formal joint counts: similar results to DAS28 and CDAI in clinical trials and clinical care. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2009;35(4):773–778.

- Iragorri N, Hazlewood G, Manns B, et al. Psoriatic arthritis screening: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology. 2019;58(4):692–707.

- Perez-Chada LM, Kohn A, Gottlieb AB, et al. Report of the Skin Research Working Groups from the GRAPPA 2020 Annual Meeting. J Rheumatol. 2021;2020:201668.

- Coates LC, Kavanaugh A, Mease PJ, et al. Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis 2015 treatment recommendations for psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(5):1060–1071.

- van der Heijde D, Deodhar A, Fitzgerald O, et al. 4-year results from the RAPID-PsA phase 3 randomised placebo-controlled trial of certolizumab pegol in psoriatic arthritis. RMD Open. 2018;4(1):e000582.

- van der Heijde D, Mease PJ, Landewé RBM, et al. Secukinumab provides sustained low rates of radiographic progression in psoriatic arthritis: 52-week results from a phase 3 study, FUTURE 5. Rheumatology. 2020;59(6):1325–1334.

- Chandran V, van der Heijde D, Fleischmann RM, et al. Ixekizumab treatment of biologic-naïve patients with active psoriatic arthritis: 3-year results from a phase III clinical trial (SPIRIT-P1). Rheumatology. 2020;59(10):2774–2784.

- Kampylafka E, D Oliveira I, Linz C, et al. OP0305 Disease interception in psoriasis patients with subclinical joint inflammation by interleukin 17 inhibition with secukinumab – data from a prospective open label study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:199.

- Solmaz D, Ehlebracht A, Karsh J, et al. Evidence that systemic therapies for psoriasis may reduce psoriatic arthritis occurrence. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2020;38(2):257–261.

- Kampylafka E, Simon D, d’Oliveira I, et al. Disease interception with interleukin-17 inhibition in high-risk psoriasis patients with subclinical joint inflammation-data from the prospective IVEPSA study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2019;21(1):178.

- Savage L, Goodfield M, Horton L, et al. Regression of peripheral subclinical enthesopathy in therapy-naive patients treated with ustekinumab for moderate-to-severe chronic plaque psoriasis: a fifty-two-week, prospective, open-label feasibility study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(4):626–631.

- Lininger N, Siegel S, Kiwalkar S, et al. FRI0555 Do TNF inhibitors decrease risk of incident psoriatic arthritis in psoriasis patients compared to those treated with methotrexate alone? Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79(Suppl 1):879–880.