ABSTRACT

Public parks were first established in the UK in the newly industrialised cities of Manchester and Salford, as nineteenth century cultural strategies for public health, regulation and education responding to moral anxieties about the changing conditions of everyday life. This article looks at public parks as vernacular spaces for everyday participation, drawing on empirical research, including ethnographic fieldwork, household interviews and focus groups, and community engagement conducted for the Manchester-Salford ecosystem case study of the ‘Understanding Everyday Participation – Articulating Cultural Value’ (UEP) project [Miles & Gibson, 2016. Everyday participation and cultural value. Cultural Trends, 5(3), 151–157]. It considers narratives of participation [Miles, 2016. Telling tales of participation: Exploring the interplay of time and territory in cultural boundary work using participation narratives. Cultural Trends, 5, 182–193], which reveal how parks are valued and recognised as community assets and spaces for both tolerance and distinction, where different communities can meet, become visible, and perform shared and distinct cultural identities [Low et al., 2005. Rethinking Urban Parks, Public Space and Cultural Diversity. Austin: University of Texas Press]. It draws on the conceptual device of ‘the commons’, defined as a dynamic and collective resource that stands in tension with commodified and privatised space [Gidwani & Baviskar, 2011. Urban Commons Review of Urban Affairs: Economic & Political Weekly, Volume XLVI No. 50 December 10, 2011. http://www.epw.in/journal/2011/50/review-urban-affairs-review-issues-specials/urban-commons.html]., to explore how parks present opportunities for civic participation through contemporary processes of ‘commoning’ [Linebaugh, 2014. The Magna Carta Manifesto: Liberties and Commons for All. Berkeley: University of California Press]. I argue that parks are also subject to contemporary forms of enclosure through social exclusion and physical closure, which impact on the likely success of current policy imperatives for community asset transfer and alternative management models.

Introduction

In 2016, the House of Commons Communities and Local Government Committee’s Inquiry on Public Parks gathered opinion from over 13,000 people who completed an online questionnaire, submitted oral and written evidence and contributed through social media, on the value and future of public parks (CLG, Citation2016). Although at time of writing the Inquiry has yet to report, this outpouring demonstrates the public interest in such resources and a growing concern for their management; in Manchester, the recent consultation on draft strategy for public parks received the highest level of public response for any consultation in the city ever (Chappell, Citation2016, p. 13). At the same time, there are growing numbers of parks’ Friends groups established to augment local authority provision and management through volunteer labour; this whilst 92% of park managers report revenue income cuts over the last three years and 95% of park managers expect budget cuts to continue into the near future (Heritage Lottery Fund, Citation2016a, p. 3).

This article explores the value of parks, as spaces for everyday participation which mediate and contribute to the relationships between people and the places in which they live. It draws on qualitative research in the two wards of Cheetham, North Manchester and Broughton, East Salford, which involved two waves of household interviews (see Miles, Citation2016), three focus groups with young people and a period of ethnographic fieldwork (Edwards, Citation2015).Footnote1 It also discusses a participatory community engagement project with the Manchester Jewish Museum, led by an artist-in-residence in Cheetham Park, which followed on from the empirical research.Footnote2

The site of the research in Salford and Manchester is the location of the very first publicly owned and managed parks in England, established in the mid-nineteenth century as amenities for the rational recreation and self-improvement of the working classes of these industrialised cities (Gilmore & Doyle, Citationin press). The research reveals the types of participation and breadth of communities and interests that are served by these public parks today. The article uses the conceptual lens of ‘the commons’, suggested by the historical relationship between the development of the public park, and the enclosure of common and waste lands (Howkins, Citation2011; Linebaugh, Citation2009), which has more contemporary application as a term to describe a collective resource and vehicle for civic participation (Gidwani & Baviskar, Citation2011). Through analysis of the fieldwork research and the follow-on project, I explore how understanding everyday participation in parks as ‘commoning’ (Linebaugh, Citation2009) may have policy implications for the future sustainability of public parks.

Everyday park life in North Manchester and East Salford

The UEP case study area comprises the inner city wards of Cheetham, North Manchester, and Broughton, East Salford, which span two local authorities and two conjoining cities. These wards are characterised by ethnic diversity and an associated rich range of cultural and religious practices. Broughton (and in particular Higher Broughton) is home to a large, orthodox Jewish community, comprising 14% of the population according to the last census (ONS, Citation2013). The Cheetham Hill Road area has one of the widest ranges of spoken languages in Europe: 35% of residents do not speak English as their first language, with Urdu being the second most spoken first language (Manchester City Council, Citation2013, p. 13). This diversity is rooted in consecutive waves of immigration associated with industrial textiles manufacturing, but also the Irish famine, the persecution of Jewish communities in Europe, post-war commonwealth immigration and more recent settlement from Eastern Europe. This history of immigration and religious diversity is also reflected in a wide range of places of worship. There are high levels of social housing, and also of relative deprivation: the Manchester Independent Economic Review identified Cheetham Hill as an ‘isolate’ neighbourhood applying to the worst fifth of places in terms of indicators of deprivation, where households have a tendency to be trapped into movement between similar areas of social need (MIER, Citation2008). The area has a reputation for the production of counterfeit goods and for organised crime and drug dealing which has been widely reported (e.g. see Osuh, Citation2015; Scheerhout, Citation2016).

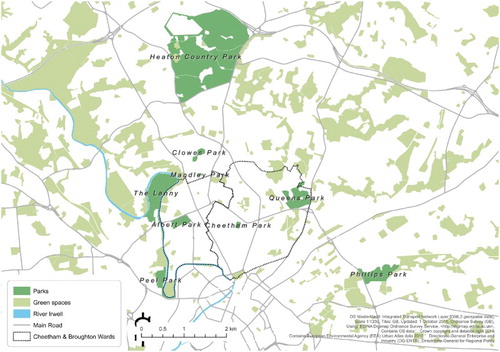

The topography of the research area comprises a mixture of residential streets, industrial estates, local high street shopping and out-of-town shopping parks. The area was rapidly industrialised during the nineteenth century, and is bookended by two of England’s first public parks (Peel Park and Queen’s Park). Arterial roads and tram and bus routes lead into/away from to the centre and to the ring road to Salford, linking the two cities with other towns in the conurbation of Greater Manchester. Typically concentric, the wards are harder to transverse laterally via public transport than to travel towards the inner city. The areas are however relatively well-served by open green spaces, with a range of parks and some nature reserves, as well as brownfield sites waiting development, which are evenly spaced and reachable on foot (see ). In the research analysis below, I look at how these parks comprise ‘commons’ spaces for everyday participation for local communities.

The public park and ‘the commons’

The relationship between parks and common land cannot be understood without consideration of the antonymic process of enclosure and its association with land as productive resource. As Howkins (Citation2011) argues, the effects of the enclosure movement have been hotly debated in English social history, with claims that the enclosure of the open field system fundamentally changed class structure, by forcing wage labour, contrasting with the argument that continuing use of common land subsidised an existing working class. By the mid-nineteenth century enclosure was predominantly associated with the industrial urban context, and ‘the commons’ emerged as an enduring concept for radicalisation and agency, symbolising an English poor, robbed of their birth right. But ‘Commoners’ who used the land for grazing or firewood collection were marginalised, and the commons became seen less as a productive resource, and more a public amenity and form of philanthropy, providing freedom to roam, allied to the concerns over a lack of provision for public walks. These concerns translated into the lobbying and later policy rationale for public parks, which both provided open space and regulated public behaviour (Gilmore & Doyle, Citationin press).

Recent research commissioned by the Heritage Lottery Fund (Citation2016c) reports on the popular use of public parks, with evidence of user segmentation. It finds that over half (57%) of UK adults use their local park once a month or more (with 35% using it once a week). Certain groups are more likely users: 90% of households with children under five are most likely to use the park once a month or more (and 54% once a week or more), while Black and minority ethic people are more likely to use parks more frequently (45% once a week or more) than white residents (34%) (Heritage Lottery Fund, Citation2016c, p. 3). The ethnographic research for UEP conducted by Edwards (Citation2015) also observed a taxonomic grouping of participation (see ) that aligns with other accounts of visitor segmentation (Keshavarz, Citation2013; Neal, Citation2013; Smith, Tuffin, Taplin, Moore, & Tonge, Citation2014). Parks are used for multiple purposes and in different social configurations, as places where families can spend time together, where people may engage in distant-but-together activities, such as team sports, or incidental co-presence, within playgrounds or outdoor gyms. They are also places of solitude and contemplation. They offer participation opportunities that distinctly contrast with those offered within indoor spaces such as shopping centres, the cinema or theatre and museums (Low, Taplin, & Scheld, Citation2005). In particular, there is less constraint on the times and uses they make of park spaces compared to these other cultural spaces and therefore greater freedom in the meanings and values they attach to participation (Edwards, Citation2015).

Table 1. Taxonomy of participation and park users.

The ethnographic research also found that ethnicity can be demarcated and in some cases actively represented by participation in parks. In contrast to other studies, such as Low et al. (Citation2005) and Taplin, Scheld, and Low (Citation2002), it proposes that park users in Cheetham and Broughton are not clearly demarcated by their individual or ethnic identities, but rather through their choices of participation, and the times, spaces and activities in which they participate. This echoes the findings of other studies. Keshavarz (Citation2013) notes in her study of Muslim park users in Birmingham and Aachen that religious practices and beliefs shape participation choices, such as avoiding parks where dog-walkers are common, or during summer months, when non-Muslim users are not wearing full clothing to cover their bodies. Particular parks become social hubs which are gender segregated, chosen by “mothers-with-children”, where relaxation amongst a common Urdu or Arabic-speaking female group can take place; parental control of children and young people’s use of parks is more stringent, for fear of hate crime, dog-walking, drug dealing and other anti-social behaviour (Keshavarz, Citation2013, p. 129).

Similar practices were noted in the focus groups we conducted with young people. For example, the predominantly Muslim members of the Abraham Moss group talked about family days out in parks, most notably Heaton Park, which because of its distance required access by car meant parents and other relatives are usually present. By contrast, the Albion Academy group members (who were predominantly white and all non-Muslim, non-Jewish) spoke of encounters they had in their local park on their own, without parental stricture, as a potentially dangerous place of “full of baggies and paedos” (heroin addicts and paedophiles) where occasionally people could be found living in tents. The members of the Jewish Boys Group in Broughton were more likely to visit parks and public spaces at times most popular with the Jewish community, such as Sunday afternoons, in part to avoid anti-Semitism but also because they did not want to spend time in a place with a high proportion of non-Jewish people to minimise the influence of non-Jewish culture.

The household interviews conducted for UEP reveal a nuanced, narrative understanding of the values and meanings attached to the public parks in the case study area. Participants were asked to identify key places, people and activities in their lives, past and present, which they like and dislike and which give them a sense of belonging, as well as social networks of family and friends and broader communities of interest and association (Miles & Gibson, Citation2016). An analysis of interview data compares references to “park” and “parks”, alongside a range of other assets, including museums, theatres, pubs, shops, libraries, doctors and places of worship (see ). Although this is a basic form of frequency analysis which does not reveal the semantic context of the references, suggests the comparative importance of these assets as a theme and focus of conversations between interview and interviewee.

Table 2. Word frequency of selected ‘community assets’ referred to in Manchester-Salford household interviews.

These references were then explored in context. The discussions about parks suggest that they are considered by interviewees as productive spaces which confer value onto place. When asked about their perceptions of their local neighbourhoods, interviewees acknowledged parks as a mechanism for ‘elective belonging’ (Savage, Bagnall, & Longhurst, Citation2005). They facilitate an attachment to place, with appeal over and above their immediate use value and are “symbolically and functionally part of the larger landscape of the city” (Taplin et al., Citation2002, p. 91). Parks are important resources for families, and there are many references to their use for the entertainment of children and grand-children. This is often articulated as a generative role within the context of the family unit, where visits to the park are not for the interviewee’s participation per se but as places in which you can practice ‘being a family’ in a managed, dedicated space. For example, Steve, a teacher, marathon-runner and mountain-biker who moved from Bolton to live with his partner and her son in Cheetham, mentioned parks as one of the things they like about the area. The parks present a space where they can be together as a family. They are managed spaces, of order and safety in contrast to other public space nearby their home which suffers from vandalism and littering.

I like the locality of it, that it’s easy to get to Manchester. It’s got good parks nearby in Prestwich that we quite like going to, in particular Philips Park, it’s got Prestwich Clough, there’s a lot going on in Prestwich. So it is accessible to quite a few things going on. The bits I dislike about the area are the, well, constant litter. Our house backs onto the grass piece behind and it’s constantly being dumped on with random objects. We’re constantly ringing for fire service ‘cause them objects are then set on fire by children … we have contacted the housing association to see if we could fence it off and do something with it, maybe allotments or something, but we’re struggling to get them to actually agree to anything at the moment.

On the river bank over there they’ve just done the path so that people can use it as a walkway. At first I was a little concerned because I thought, well as long as they don’t put benches over there so that people can sit over there, you know, youngsters can congregate. But whereas I would have been besotted by the idea a few years ago it just went out my mind. I thought, if they’ve got to do it they’ve got to do it, you know. And you know, it’s improved the area, you see joggers, which is nice to actually see people, you know like normal people jogging, using it as--, I mean walking dogs, jogging on it, riding push bikes. I mean because this area has been on its knees in the past, and that people are actually looking after themselves and keeping themselves fit, you know, it’s nice to see.

And over time trees have grown and the River Irwell runs alongside of it and you--, as a kid we used to love going there, you know, it was like--, it was like a big adventure, you know, that was part of my childhood, going there, yeah.

Yeah I do, yeah, it would be very hard for me to move out of here ‘cause obviously out of all my family, they’re dead close by and I’ve lived here, every single park here I’ve grown up in, the primary school, the high schools.

Parks can also facilitate co-operation between different communities by offering the means for communal participation in activities where everyone understands the rules, for example through community sports. In this sense they provide the opportunity for what Linebaugh (Citation2014) call ‘commoning’. He argues the commons is inextricable from its gerund, a verb not a noun, an activity of labour as much as it is a resource: “Commoning is exclusive inasmuch as it requires participation. It must be entered into” (Linebaugh, Citation2014, p. 15). There are rules for participation, agreed terms for use, and mechanisms of policing or sanction, to protect the depletion of the commons.

For Asif, a young man of Pakistani origin who had come to Manchester after growing up in Spain, his local park allows a large and disparate group of other young people to meet and play football or cricket, every weekend and every weekday during summertime. This group is mainly male, but mixed ethnicity including Asian and white. Despite this enduring commitment, it is not the park that acts as a commons but the participation: the same large group also gets together in takeaways if the weather is bad. Asif also comments on how the rules are different here compared to Spain, and he adjusts his understanding of park behaviour to be more culturally sensitive to the practices in Manchester. For example, he was used to graffiti, breakdancing and hip hop culture as normal practice in parks, whereas in Manchester music and dance tend to occur only in some city centre sites and graffiti is criminalised.

However, parks can also be socially exclusive, and sources of fear and anxiety within the broader narratives of people’s lives. This form of ‘social enclosure’ was most often articulated by our interviewees in relation to concerns over the gangs of youths, intimidation, anti-social behaviour and littering which parks can attract. They can become stewarded by particular groups to the exclusion of others: James, who previously had experienced homophobic intimidation and assault, actively avoids part of parks where he knows gangs of youths gather, for fear of further attacks.

I don’t really go around there during the summer though like I said ‘cause it’s too many kids and with my dog as well it’s, you know, I don’t want her like latching on to kids because it’s encouraging them to come over and talk to me and, you know, like I mean, I’ve heard some kids around here and they can be downright cruel.

The threat to urban commons

In their conceptualisation of the urban commons, Gidwani and Baviskar (Citation2011) distinguish between ecological commons (assets that provide or support environmental resources) and civic commons (which include public spaces, schools and transport systems). They argue that urban commons are under threat of enclosure through privatisation, regulation and surveillance, associated with the defence of private property. According to the UEP research, parks are both ecological and civic commons, which can be enclosed through social sanctions which exclude and segment certain groups and practices. Public ownership and access to parks are also threatened by physical neglect and closure due to local authority budget cuts and restructuring imposed by post-recession austerity measures (Neal, Citation2013). Parks in England have experienced on average real-term cuts of over 20% budgets between 2010–2011 and 2013–2014 (Heritage Lottery Fund, Citation2014, p. 6). As a non-statutory service, park management (alongside other arts, culture and heritage budgets) is predicted to be hit by 46% cuts in funding by 2020, and 45% of local authorities are considering disposing of some green spaces (Heritage Lottery Fund, Citation2014, p. 6). As a result, new strategies for managing park portfolios are sought, including further research on the state of parks (Heritage Lottery Fund, Citation2016b) a two-year pilot R&D programme (Nesta, Citation2016), the Commons Select Committee on the Future of Parks (CLG, Citation2016) and in Manchester, a new Parks Strategy for the city’s 143 parks and green spaces. This strategy will need to deliver in the context of budget cuts, re-structuring of the city’s Neighbourhood services and the implications of devolution on the city-region. Alongside a continuing emphasis on maintaining community participation and a local standard for parks, the draft strategy positions parks as part of economic strategy, as “positive value added investments, and a platform for ‘good economics’” (Manchester City Council, Citation2016, p. 4) and calls on potential private investors citing the positive impact on property and land value.

The ‘returns on investment’ which parks can offer in return for public funding are highly contingent on establishing new models for sustainable park management in the face of decreasing revenue budgets. One favoured model emerging from a variety of policy documents, research and consultation exercises is the development of community-led partnerships and management groups which generate new income streams and/or apply for project funding (Greenspace, Citation2011; Heritage Lottery Fund, Citation2014, Citation2016a; Nesta, Citation2016). Community management is seen to have the added value not only of reducing public cost and liability for the upkeep of parks through volunteer labour, but also of social returns on investment through increasing civic participation:

[community managed parks] help empower local people to take more control of their environment and give them an opportunity to become more active in their communities. (Greenspace, Citation2011, p. 8)

The community engagement project which followed on from UEP empirical research attempted to encourage civic participation in Cheetham Park, North Manchester, as a basis for a community-led group which could lobby for the conservation and future of Cheetham Park, North Manchester. This small public park, established in 1885, has been the site of previous civic engagement events, including an Olympic-themed family fun day, with the aim to develop a Friends group as part of the local neighbourhood plan (Manchester City Council, Citation2012). The project was led by an architect working as artist-in-resident with the Manchester Jewish Museum, joined by University of Manchester researchers, including the author. It involved a programme of participatory activities, such as craft workshops, gardening, bird watching walks, nature talks, oral history collecting, public lectures, family events and other participatory practices to ‘activate a commons’ through which to engage local residents in community asset management. The programme was designed to show the park as a productive resource, through the growing of dyes and other plants and through the access it provides to the natural environment and social space. The nearby Manchester Jewish Museum has related collections and connections to the park, which is next to the site of a former Jewish hospital. It hoped to promote local audience development as part of a Heritage Lottery Fund capital development project. Outputs included a short film and digital archive and a new historical society, and the artist applied for Grade II listing of an original park shelter as a heritage asset on the basis of the historical evidence from the research.

A range of local participants including existing park users took part in the activities but the recruitment of ‘commoners’ prepared to commit to ongoing involvement proved unachievable. Coordinating engagement across a range of religious and institutional practices and diaries, including the London-based artist, the Jewish calendar, a nearby mosque and school, proved particularly difficult. ‘Threshold anxieties’ existed for different religious and ethnic groups, who did not want to cross the boundaries of particular spaces or take part in activities at particular times, especially as some activities took place in the Jewish museum, a former synagogue. Despite high expectations and considerable investment in different methods for engagement, the establishment of a management group was neither sustained nor sustainable. Lang (Citationin press) argues that the lack of ‘commoning’ in this instance was not down to the diversity of communities or the conflicts between different ethnic and religious practices, but rather the City Council’s failure to act as enabling body for the collective use of common rights and rules. There was a self-perception within participants that communities are simply neither equipped nor accountable as park managers, and for some even the suggestion of encouraging community involvement seemed an absolution of responsibility by the local authority. Meanwhile the local authority found it hard to invest time into support for the project with so many competing priorities. Ongoing vandalism of the park’s facilities was seen as clear evidence that user-communities do not value the space, despite the strong sense of the park’s place in community history, particularly for older Jewish community members.

Ward (Citation2014) highlights the distinction, made originally by Ostrom (Citation1990), between common-pool property which is owned and managed collectively, and common-pool resources which provide common access for all. The rights to property and to the regulation of access and use of resources are of central concern to the maintenance and sustainability of the commons, with Ward warning that commons are not simple utopian alternatives to private property but involve conflict between individuals, social classes and communities (Citation2014, p. 3). These tensions can be further understood as a distinction between the cultural, involving shared norms but diverse perspectives on decision making, and the economic, which assumes that management of resources will operate through systems of rational self-interest (Ward Citation2014, 59). The tensions over the stewardship of and responsibility for Cheetham Park suggest it does not function as a common-pool property, yet neither is it a common-pool resource for all groups. As the owner of this site, the local authority is ultimately responsible for maintaining common access and for establishing the rules for participation, which may encourage different kinds of community stewardship. Without shared agreement on a community organisation to transfer the park’s ownership to, the likelihood is that the park or parts of it will move into private hands, and that access to the spaces of participation the park currently provides will be lost.

Conclusions

Both the research on everyday participation and the follow-on community engagement project confirm the values of parks to local communities. They suggest that parks provide common spaces where considerable social investment takes place. They are community assets which serve localities and raise the overall quality of and satisfaction with local neighbourhoods. They are places where diverse groups can come together to practice civic participation, continue family life and make memories which carry long into adulthood. Everyday participation in parks requires negotiation of difference and distinction, however, and sometimes the rules of participation in common resources can be exclusionary and create segregation and segmentation of their users.

The pressure is on local authorities to find the means for ongoing maintenance and/or create viable alternative models of management, to enable the urban commons. Parks are in the same position as other non-statutory culture and leisure services such as libraries and museums, with budget cuts predicted to worsen significantly as the proportion of funding for these services will decrease to mitigate the impact on statutory services, such as children and adult social care (Heritage Lottery Fund, Citation2016b). These public spaces therefore face enclosure through the dilapidation of amenities and privatisation. Unless ways are found to resolve tensions between the cultural and the economic, and conflicts over the ownership, rights and responsibilities to these resources, parks will cease to be places for commoning and the cultural values it provides for communities in their everyday lives.

ORCID

Abigail Gilmore http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0596-6667

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. This article presents research and analysis from AHRC Connected Communities project Understanding Everyday Participation – Articulating Cultural Values. Household interviews were conducted in Manchester and Salford in 2012 and 2013 (see Miles & Gibson, Citation2016 for methodology). Three focus groups were held using drama workshop methods with children and young people (between ages of 10–16), recruited through their membership of the following: Abraham Moss School Year 10 Student Voice Leaders group, Albion Academy After School Club and Broughton Hub Jewish Boys Youth Group. All names of participants have been changed.

2. The residency involving Torange Khonsari, DIY Commons/Public Works, with Max Dunbar, Manchester Jewish Museum was funded by Leverhulme Trust. Documentation, oral history research and two events were funded by AHRC Connected Communities Festival 2015 ‘Connecting the museum and the park – everyday participation and community stewardship of local cultural assets’ and through the University of Manchester Researcher-in-Residence scheme involving Luciana Lang, Jeni Allison and Eugenia Whitby. Further support came from Manchester City Council and in particular Pauline Clarke. I acknowledge and thank all participants in the project.

References

- CABE Space. (2010). Urban Green nation: Building the evidence base. London: CABE.

- CLG. (2016). Communities and local government committee public parks inquiry. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.uk/business/committees/committees-a-z/commons-select/communities-and-local-government-committee/inquiries/parliament-2015/public-parks-16-17/

- Chappell, K. (2016). The Mancunian breakthrough. In The Fabian Society (Eds.), Green places (pp. 12–14). London: Fabian Society.

- Edwards, D. (2015, May). Ethnography report for Manchester-Salford Cultural Ecosystem, unpublished research report for Understanding Everyday Participation.

- Gidwani, V., & Baviskar, A. (2011, December 10). Urban commons review of urban affairs: Economic & political weekly, Volume XLVI No. 50. Retrieved from http://www.epw.in/journal/2011/50/review-urban-affairs-review-issues-specials/urban-commons.html

- Gilmore, A., & Doyle, P. (in press). Histories of public parks in Manchester and Salford and their role in cultural policies for everyday participation. In E. Belfiore & L. Gibson (Eds.), Culture and power: Histories of participation, values and governance. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Greenspace. (2011). Understanding the contribution parks and green spaces can make to improving people’s lives Retrieved from http://greenflagaward.org/media/51265/green_space.pdf

- Heritage Lottery Fund. (2014). The state of UK parks 2014: Renaissance to risk? London: Heritage Lottery Fund.

- Heritage Lottery Fund. (2016a). State of the UK public parks. London: Heritage Lottery Fund.

- Heritage Lottery Fund. (2016b). State of the UK public parks research report. London: Heritage Lottery Fund.

- Heritage Lottery Fund. (2016c). State of the UK public parks II: Public survey, Report prepared by Britain Thinks. London: Heritage Lottery Fund.

- Howkins, A. (2011). The commons, enclosure and radical histories. In D. Feldman & J. Lawrence (Eds.), Structures and transformations in modern British history (pp. 118–141). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Keshavarz, N. (2013). Muslim perspective on neighbourhood park use in Birmingham City, United Kingdom and Aachen City, Germany (Doctoral thesis). Submitted to the Faculty of Spatial Planning Technical University of Dortmund, Dortmund.

- Lang, L. (in press). Materializing the intangible through civic participation in Cheetham commons. In C. Lewis, & J. Symons (Eds.), Realizing the city: Ethnographic narratives of the Manchester city region. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Linebaugh, P. (2009). The magna carta manifesto: Liberties and commons for all. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Linebaugh, P. (2014). Stop thief! The commons, enclosures and resistance. Oakland, CA: PM Press.

- Low, S., Taplin, D., & S. Scheld. (2005). Rethinking urban parks, public space and cultural diversity. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Manchester City Council. (2012). Cheetham ward plan 2012–2014. Manchester: Manchester City Council.

- Manchester City Council. (2013). 2011 Census ward level analysis, research and performance report. Retrieved from http://www.manchester.gov.uk/download/downloads/id/21207/q05p_2011_census_ward_overview.pdf

- Manchester City Council. (2016, February 23). Update on parks strategy: Report to neighbourhood scrutiny committee. Manchester: Manchester City Council.

- MIER. (2008). Manchester independent economic review economic baseline study; UK archives. Retrieved from http://www.manchester-review.org.uk/project_720.html

- Miles, A. (2016). Telling tales of participation: Exploring the interplay of time and territory in cultural boundary work using participation narratives. Cultural Trends, 5, 182–193. doi:10.1080/09548963.2016.1204046

- Miles, A., & Gibson, L. (2016). Everyday participation and cultural value. Cultural Trends, 5(3), 151–157. doi:10.1080/09548963.2016.1204043

- Neal, P. (2013, November). Rethinking parks. London: Nesta.

- Nesta. (2016, February). Learning to rethink parks. London: Nesta.

- ONS. (2013). Area: Broughton Ward. Religion, 2011 KS209EW [data set] Retrieved November 30, 2016 www.neighbourhood.statistics.gov.uk

- Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Osuh, C. (2015, March 26) Cheetham Hill gang behind £2 m drugs conspiracy given prison sentences totalling more than half a century, Manchester Evening News. Retrieved from www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk

- Savage, M., Bagnall, G., & Longhurst, B. (2005). Globalisation and belonging. London: Sage.

- Scheerhout, J. (2016, January 9). Cheetham Hill named the counterfeit capital of the UK, Manchester Evening New. Retrieved from www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk

- Smith, A. J., Tuffin, M., Taplin, R. H., Moore, S. A., & Tonge, J. (2014). Visitor segmentation for a park system using research and managerial judgement. Journal of Ecotourism, 13(2-3), 93–109. doi:10.1080/14724049.2014.96311

- Taplin, D., Scheld, S., & Low, S. (2002). Rapid ethnographic assessment in urban parks: A case study of independence national historical park. Human Organization, 61.1(Spring), 80–93. doi:10.17730/humo.61.1.6ayvl8t0aekf8vmy

- Ward, D. (2014). The commons in history: Culture, conflict, and ecology. Cambridge: The MIT Press.