ABSTRACT

This paper provides a systematic and critical review of the literature on cultural and creative ecology and ecosystems. There has been a growing use of ecological language in relation to the cultural and creative sectors within both research and policymaking. However, there is little consistency in the terms employed, with considerable slippage in meanings and application. The paper, therefore, undertakes a two-stage review of the literature. First, a systematic review analysing the content of 56 publications identified within Web of Science, Scopus and Google Scholar. Secondly, a critical review examining definitional and terminological inconsistencies, the boundaries and geographical scales of cultural and creative ecosystems, and the range of methods and data employed. Here we clarify the relationship between ecological approaches and previous framings such as “creative industry” and “creative economy”. The paper concludes by proposing an agenda for future research, seeking to consolidate the research field and support ecological policymaking.

Introduction

In recent years there has been a growing emphasis on the need to study the cultural and creative sectors from an ecological perspective. While this connects with broader emerging environmental concerns (discussed later in the paper), here “ecological” is not primarily about the biological environment and more concerned with an increase in the use of complexity and systems frameworks in social science (Byrne, Citation1998) and in application to the cultural and creative industries (CCIs) (Comunian, Citation2019). This paper investigates whether and how ecological research approaches of this kind break some of the limits of previous conceptual framings – such as cultural and creative economy, cultural and creative clusters, cultural and creative industries – by examining cultural and creative activity from a broader perspective (than supply-chains and clustering, for example): including a wider range of actors, relationships and geographic scales.

One of the starting points for this paper is that whilst there is a growing use of this kind of terminology, the existing literature provides little clarity on the overall scope and definition of this “ecological” perspective and its analytical framework. Therefore, in response to the growth in popularity of these ideas and approaches, this paper provides a comprehensive review of the literature on cultural and creative ecologies and ecosystems (CCEE).Footnote1 It presents the current size and characteristics of this growing research area, demonstrating the need to clarify the terminology used and its connections with other terms and research fields. It also reflects on the methodological approaches used by key studies employing ecological perspectives. The paper offers a comprehensive overview that aims to build on existing work to provide clarity of direction for this emerging field, offering foundational reflections for researchers seeking to contribute to the ecological study of culture and creativity in the future, beyond a narrowly sectoral approach.

The paper is structured in four parts. Firstly, we discuss our methodology and data, explaining how we explored the current academic knowledge-base concerning CCEE across a range of disciplines, academic outputs and policy documents. We then present the results of the first phase of our systematic literature review, which led to the selection of a core list of publications. These consequently become the object of an in-depth critical review. In the third part, we explore further how the data (56 between articles, chapters and reports) help us identify different approaches to studying CCEE. Here we discuss the growth of this area of research in recent years and reflect on how it can be read as an expansion beyond previous conceptual framings (such as industry and economy), aiming to more fully address the plurality and interconnectivity of activities, aims and values present within CCEE, and to thereby overcome some of the analytical and policy limitations of these previous perspectives. We reflect on the sometimes-confusing terminology used within the literature on CCEE, and the type of methodological approaches researchers have adopted. In the final discussion and conclusions, we summarise the implications of our systematic and critical literature reviews for the future development of this emerging research field. We offer specific directions for future work in this area, helping to establish a more coherent approach to the study of CCEE.

Methodology, data and research questions

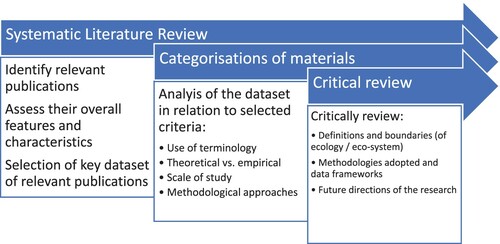

We have examined this emerging research area through a combination of literature review methods to provide a comprehensive overview of the authors and approaches used. Our approach has followed three stages corresponding to three different ways to map and review an existing body of knowledge. Firstly, following Petticrew and Roberts (Citation2008) we conducted a systematic literature review across Scopus, Web of Science and Google Scholar. We then undertook a two-stage integrative and critical review, enabling us to synthesise and differentiate the publications collected. Here we followed the approach of Merli et al. (Citation2018) to think about opportunities for further categorisations of the data that would allow us to answer some key research questions:

In what ways does the literature distinguish (or not) between cultural and creative ecologies and cultural and creative ecosystems?

What is the balance in the literature between theoretical and empirical contributions, and what methodological approaches are used by researchers in the field?

What is the geographical scale of the object analysed? Are ecologies/ecosystems studied at the project (micro), city (meso) or regional/national (macro) level?

In what follows, after establishing a quantitative overview of these dimensions, we develop a critical reading of what insights the data offer as we seek to develop a more coherent research framework with which to study CCEE. In this qualitative analysis, we particularly consider (1) How are CCEE defined and understood within different subject areas and by key authors? (2) What are the methods adopted, including the types of data collection employed? (3) What might move forward the research in this field? The overall process of the literature review is summarised in .

Systematic literature review: methodology and data

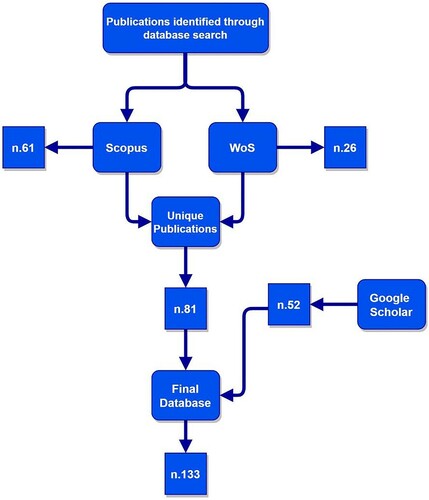

Our systemic literature review (SLR) draws its approach to building and analysing a multi-database literature sample from Petticrew and Roberts (Citation2008) and its process of developing analytical categories from Merli et al. (Citation2018). Firstly, we constructed a database of pertinent publications by aggregating searches on Scopus and Web of Science (WoS). We conducted four searches on the two databases and then merged into two aggregated searches:

“Creativ* Ecolog*”

“Creativ* Ecosyst*”

“Cultur* Ecolog*”

“Cultur* Ecosyst*”

We further refined these searches to obtain literature within or adjacent to the cultural and creative sectors, rather than in fields such as environmental science. On Scopus, the results were limited to four subject areas, Social Sciences, Arts and Humanities, Economics, Econometrics and Finance and Business, Management and Accounting. This resulted in 437 publications. Furthermore, only those containing keywords Creative Cities, Creative Clusters, Creative Ecology, Creative Economy, Creative Ecosystem, Creative Industries, Creative Industry, Creative Labour, Creative Society, Creative and Cultural Economy, Cultural Ecology, Cultural Economy and Cultural Ecosystem were accepted in the final refinement. The subject area and keywords filter allowed us to focus on a coherent dataset, ensuring that the authors selected were all indeed exploring the same broadly conceived research area: what we, in this paper, are bringing together as CCEE. A further filter was then applied, selecting only papers written in English. Through this process 61 publications were identified.

On WoS we excluded every category other than Social Science Interdisciplinary, Humanities Multi-Disciplinary, Economics, Cultural Studies, Management, Regional Urban Planning, Business, Sociology, Urban Studies, Art and Business Finance, leading to 89 papers. Although Scopus and WoS operate different querying structures, we ensured a high degree of similarity between the two searches via a second selection process, applying the very same thirteen keywords used as a filter in Scopus. Again, only English language texts were included. This identified 26 papers in WOS. After removing 6 duplicates, the merged database of Scopus and WoS included 81 unique publications.

The literature review highlights the strong presence of English-language scholars and case studies in the debate. This was expected, given the major role played by “creative industries” policy and academic debates in the UK and Australia and by “creative economy” and “creative class” discourses in North America since the late 1990s. It has been in the UK, Australia and North America that both scholarship and policy debate related to CCCE has primarily taken place: and in many ways we see the development and growth of CCEE research approaches as a response to the narrow policy perspectives – in terms of creative industries, creative economy and creative class – adopted in those locations in the previous decades. However, the CCEE framework now has global reach (See Bakalli, Citation2015) and has the potential to be applied far beyond the initial contexts in which it was developed; and it is precisely part of the potential value of this approach that it can challenge the rigidity and geographical detachment of previous development models (that, for example, completely overlooked the specificities of non-urban, non-western locations) and address differences between contexts.

Within the emerging literature applying ecological concepts to the cultural and creative sectors, a major contribution comes from grey literature, which is not indexed in Scopus or Web of Science. This necessitated a third search on Google Scholar, applying the four ecological keywords listed above, and following up directly on grey literature quoted by authors identified within the original searches. This identified 52 more publications. Based on this sequence of searches, our final database included 133 publications, as summarised in .

Even with the application of our multiple filters, this final sample of 133 items included some publications not directly relevant, due to distinctive usages of ecological terms in disciplines such as anthropology (Dillon & Kokko, Citation2017; Steward, Citation2006) and education (Davies et al., Citation2004). We therefore undertook a further filtering by keyword (as described above for Scopus and Web of Science) selecting only those publications relevant to the cultural and creative sectors, identifying 56 items to be included in the next stage of the literature review.

Categorisation of materials

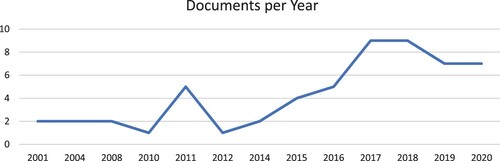

The analysis of the 56 publications included in the final dataset allows us to examine some key characteristics of this emerging research area. Looking at the publications’ timeline across the last two decades we can see a growing interest in CCEE over this period .

Having established this chronological picture, following Merli et al. (Citation2018) we then adopted an iterative process of categorisation. We identified four key features of the publications, and for each key feature we identified analytical categories that allowed us to coherently systematise the body of literature (see ).

Table 1. Key features and analytical categories.

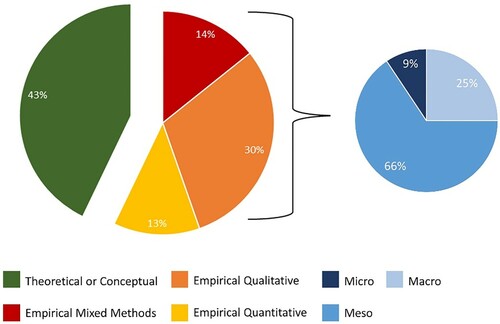

Concerning the type of contribution, two-thirds were classified as academic publications (66%) and 34% as policy reports. Whilst the latter accounts for only a minority of the publications, in the critical review we consider how these documents have been amongst the most influential in the progression of CCEE ideas and debates. We also reflect on why the policy literature has played this role in pushing the ecological agenda forward.

Regarding research methodology or approach, 43% are theoretical or conceptual (including articles that review secondary data). The majority of publications presenting new empirical investigations adopt qualitative methods (30%), whilst quantitative and mixed methods accounted for nearly the same portion, 13% and 14%, respectively. Within the documents that provide new empirical data (57%), we focused next on the geographical level of analysis. Here we follow Comunian (Citation2019) in considering the macro lens as the one that looks at ecosystem level outputs or dynamics; the meso as the one that looks at mid level structures like networks or clusters; and the micro as the one focusing on individual units, often creative workers or their specific projects. Perhaps predictably, the majority of the papers focused on the meso scale and “mesostructures” (66%), including the analysis of networks and network-like phenomenon. Analysis of the macro level was the focus of a quarter of the whole (25%) with only 9% of the documents investigating micro dynamics .

Among the empirical investigations, the favoured geographical scale of analysis is the city (37,5%), followed by region (21,88%), neighbourhood (15,63%) and nation (12,50%). Lastly, both cluster-level analysis and other scales accounted for 6,25% each.

Critical review of the literature

The development of CCEE terminological usage over time

As shown through the systematic literature review, there has been significant growth in the use of ecological language in relation to the cultural and creative sectors in recent years. It is important to connect this development with previous frameworks, mainly the creative and cultural “economy” and creative and cultural “industries”. While these are still very firmly present within the literature, they have been widely criticised for their restrictive nature – for example, for giving priority to neo-liberal growth-oriented accounts of culture and creativity compared to not-for-profit or community driven ones (Comunian et al., Citation2020). They have also been criticised for their top-down policy-led framings that can fail to recognise the “messy” realities of cultural and creative activity, and the diversity of ways in which culture and creativity are part of people’s lives. As with the corpus of literature covered by the SLR as a whole, many of the foundational documents for these debates originate from the UK and English-language academic and policy contexts. For example, Holden’s important piece, The Ecology of Culture, which builds on an earlier publication (Holden, Citation2004), recognises the increase in use of ecological perspectives and explores some key definitional issues. He identifies Knell’s use of the terms “funding ecology” and “the arts and creative ecology” in The Art of Living (Citation2007) as one notable example of the growing use of the term during the first decade of the twenty-first century. Prior to Knell, Jeffcutt and Grabher described the main mode of collaboration between firms in the cultural and creative sectors as a “project ecology”, as “ecologies of creativity” (Grabher, Citation2004) and as a “creative industries ecosystem” (Jeffcutt, Citation2004). In policy documents, the UK Department of Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) and Arts Council England (ACE) refer to the “arts ecology” in the Our Creative Talent report (Citation2008) and This England: How Arts Council England uses its investment to shape a national cultural ecology (Citation2014). Wilson and Gross (Citation2017) highlight the terminology’s international diffusion, including adoption in the first cultural strategy for New York City (New York City Department of Cultural New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, Citation2017).

Scholars and practitioners employing ecological language challenge conventional units of analysis for the cultural and creative sectors, claiming these have significant limitations, and identify ecological thinking as a new and preferable approach. Foster, for example, argues that empirical work demonstrating the ecological functioning of creative and cultural industries shows that researching and managing them simply in terms of “creative clusters” is obsolete (Foster, Citation2020). What emerges across the literature is the authors’ shared hope that by focusing on CCEE a series of limitations of our current understanding of the cultural and creative sectors can be overcome. Firstly, CCEE seems to better acknowledge – using one single concept – the deeply interrelated modalities and value(s) of cultural and creative production and consumption (Potts et al., Citation2008) which have traditionally been considered separately. Secondly, it questions the primacy given to narrow economic imperatives of previous research frameworks (creative city, clusters or economy) by making visible relations between many different kinds of cultural and creative actors, often operating with distinctive (even divergent) value frameworks and value-generating processes. Finally, a CCEE perspective challenges the linear model on which governance and management of the cultural and creative sectors have typically been based.

However, despite these promises and noble aspirations, the CCEE notion is far from unproblematic. Despite its widespread use among policymakers and scholars, there is no shared understanding of the concept. There is no agreement on the words to use – ecology or ecosystem, creative or cultural? – uncertainty over the precise meaning and scope of these terms, and many unanswered questions about the concrete consequences of adopting the concept within research design and policymaking.

Definitional and terminological slippages

Academic work in this and related areas is no stranger to terminological debates and disagreements (Roodhouse, Citation2011). Whether to refer to the “creative industries” or “cultural industries”, and whether the term “industries” is appropriate in these contexts, are long-standing and ongoing disputes. These debates, in combination with uncertainty as to whether to use the term “ecology” or “ecosystem” and what precisely these refer to, makes for a potentially confusing array of terms and meanings within the CCEE literature. Some authors refer directly to these roots of ecological thinking within other disciplines – such as anthropology and environmental science – yet take these ideas in new directions. Holden, for example, refers to cultural work within anthropology when defining “the ecology of culture” (Holden, Citation2015). However, he does not consider further the natural environment within his description of cultural ecologies.

The choice between creative and cultural often appears to be related to the type of sub-sector being addressed, especially to the extent to which it is market-oriented. The term cultural ecology/ecosystem is often employed in the context of studies focused primarily on the not-for-profit and/or “arts” portion of the cultural and creative sectors (Gross & Wilson, Citation2019; Markusen et al., Citation2011; Patuelli, Citation2017), whilst creative ecology/ecosystem is more often employed in reference to market-oriented studies (Bakalli, Citation2015; Jeffcutt, Citation2004). However, there are notable exceptions (Blackstone et al., Citation2016; Jung & Walker, Citation2018; Mohamad & Walker, Citation2019), and because most authors employing an ecological approach do not directly explain why they choose to refer to “cultural” or “creative”, it is difficult to draw a clear or consistent rule based on existing patterns of use. Moreover, Gross and Wilson deliberately make clear that their use of ecological language is intended to demonstrate and examine the interconnections between the profit-making creative industries, the publicly funded arts, and everyday creativity (Gross & Wilson, Citation2018); and as their work shows, it is precisely the potential to more fully understand the interdependencies between these different domains of cultural and creative practice that ecological approaches offer.

Additionally, within the literature reviewed, there is slippage between the use of ecology and ecosystem. These words can be used to address two very different concepts, the former being “the science studying the relation of plants and living creatures to each other and to their environment”, the latter being “all the plants and living creatures in a particular area considered in relation to their physical environment” (Hornby & Cowie, Citation1995). However, their usages overlap. “Ecology” has been defined as both “the relation of plants and living creatures to each other and to their environment” (Ibid.) and the study of this. Hence, due to their partial sharing of meanings, they are often used interchangeably.

In summary, while the object of study is the “ecosystem” and the science studying it is “ecology”, both terms can be used to describe the object of study; and scholars and policymakers picking one or the other term do not consistently share research methods, nor a consistent understanding of the elements that constitute an ecology/ecosystem. As the next section will highlight, which cultural and creative actors and resources should be included is one of the most unclear elements of ecological approaches. This series of definitional and terminological slippages in the literature makes it difficult to consistently summarise what scholars mean and what phenomena they are precisely addressing when using these terms. Nonetheless, it is possible to identify three main ways in which the term “cultural ecology” (or it’s “creative” and “ecosystems” near-synonyms) can be used. Gross and Wilson (Citation2019, p. 10) propose that it can refer to:

A condition of the world – an ontological reality

A descriptive and analytical perspective – an epistemological framework

An approach to cultural policy, programming and practice – an organisational, managerial or strategic method

In other words, CCEE notions have been used, firstly, to indicate the complex interrelations that “always-already exis[t]” (Gross & Wilson, Citation2019, p. 19) in processes of cultural and creative practice (Jung & Walker, Citation2018; Schippers, Citation2016) and cultural and creative product delivery (Markusen et al., Citation2011). Secondly, to name an approach to analysing and understanding the cultural and creative sectors that stresses the importance of the relations among actors, arguing for a shift in “reasoning unit” from the firm and the economy to a wider, more inclusive and interrelated notion that is the CCEE, with consequences in terms of causality and methods (Foster, Citation2020). Thirdly, the notion has been used in terms of developing ecological approaches to policy and practice. For example, if the number and quality of connections between actors is an indicator of the general health of “the system”, rather than focusing on the delivery of specified outputs, attention may turn towards how best to sustain the number and quality of these relationships (Barker, Citation2020; Gross & Wilson, Citation2019; Holden, Citation2015).

Identifying the boundaries and geographic scale of CCEE

Closely connected to definitional and terminological slippage is the question of how to trace the boundaries of a CCEE. This section focuses on how the significant elements that constitute a CCEE have been understood and presented. As with the lack of explicit definitional discussion of “ecology/ecosystem”, in some publications the components of CCEE are not directly discussed or identified. A significant portion of scholars treats CCEE as composed of cultural and creative industries, institutions and artists only, with small variations between their approaches (Blackstone et al., Citation2016; Borin & Donato, Citation2015; Demir, Citation2018; Galatenau & Avasilcai, Citation2017; Mengi et al., Citation2020; Patuelli, Citation2017; Piterou et al., Citation2020). Others explicitly or implicitly include training institutions (Foster, Citation2020; Gollmitzer & Murray, Citation2008; Neelands et al., Citation2015) or the amateur/voluntary sector too (Poprawski, Citation2019). Jeffcutt includes knowledge interfaces – “the mix of social, cultural and professional relationships and networks that the enterprise possesses and can access” – and technologies, and stresses the unicity of the local ecosystem as embedded in the broader “material and social context within (and from) which these value circuits develop and are sustained” (Jeffcutt, Citation2004, pp. 77–78). Overall, beyond the narrowly “cultural” field of investigation closely focused on the not-for-profit and/or “arts” sectors, for many researchers the key potential of CCEE is to allow for the inclusion of actors and institutions operating across multiple economic, cultural and social domains. However, the boundaries are often set not only according to the principle of including many types of cultural and creative actors, but also in response to practical, methodological and feasibility considerations for data collection and analysis. This blurriness and failure (or refusal) to strictly define what is included or excluded is revealing of an important characteristic of what CCEE are. As Wilson (Citation2010) argues, creativity is a “boundary phenomenon”, taking place where different kinds of ideas, practices and materials meet, and thereby challenging and reconstituting boundaries and identities due to its inherently relational nature.

Alongside the blurred selection criteria for including specific entities, the “material and social context” is currently a relatively undefined and under-explored consideration within analyses of CCEE. Only a few authors analyse buildings and physical assets within the CCEE. For example, in one of Gross and Wilson’s case studies the cultural ecosystem is described as “a developing set of interconnections and interdependencies between a shopping centre, a church, a children’s theatre company, a secondary school, a freelance dance teacher, a National Portfolio Organization, a local authority and a network of young men who dance” (Gross & Wilson, Citation2019, p. 7). As this example indicates, place has a significant role in shaping the ecosystem through its physical dimensions, echoing insights of actor-network theory. Similarly, Tarani (Citation2011) includes old buildings and leisure activities beyond the cultural and creative sectors in her analysis. Rieple et al. (Citation2018) states that the “ecosystem includes what has been termed a socially sympathetic infrastructure (Pratt, Citation2002) and nodes: the mix of social spaces, meeting points and public areas such as markets and streets, as well as sources of inspiration such as museums and art galleries” (Rieple et al., Citation2018, p. 118). Markusen et al.’s model of cultural and creative ecology comprises extensive categories such as “organisations, people and places” (Markusen et al., Citation2011). Others include intangible values, governmental bodies, individual artists and local culture within their ecological work (Gasparin & Quinn, Citation2020; Jung & Walker, Citation2018; Schippers, Citation2016).

The complexity of elements is captured by many authors through visualisations that include overlapping or interactive elements (see de Bernard & Comunian, Citation2021 for an overview). The creation of a range of visual models is an interesting phenomenon that acknowledges the limitations of current ecological understanding and the need to develop new representations that make visible actors, hierarchies and relations in new ways. On the other hand, these visualisations clarify that any CCEE visual model is ultimately only a representation, offering a partial, simplified understanding of the complex reality of the CCEE system.

The lack of clarity in the literature pertaining to the boundaries of CCEE is closely related to the fact that competing understandings and definitions of CCEE are in operation. Some are comparatively exclusive, referring only to dimensions of cultural and creative “production”. Others are so inclusive that they are at risk of being hard to operationalise within research or policymaking. These different approaches often mirror the disciplinary roots of the authors and their arguments – economics/business in the former, and anthropology/humanities in the latter. But they also have the potential to lead in radically divergent directions with regards to policy and practice, including different views on who has agency in delivering creative and cultural products.

In the literature grounded in economics and business studies, relations between firms and other elements of the creative sectors have been extensively documented and proven to be crucial toward the delivery of cultural and creative products. In this literature, to trace the perimeter of CCEE specifically around the “cultural and creative industries” risks overestimating their agency and ignores the other stakeholders involved, such as education and training institutions, and the non-market dimensions of the cultural and creative sectors. Indeed, the growing deployment of CCEE notions within academia and policymaking suggests developing an approach able to hold together the analysis of for-profit production processes and non-market activities and contexts has been urgently needed. However, to use this terminology to simply expand but not critically redefine the “cultural and creative industries” would be a missed opportunity.

The publications grounded in anthropology and the humanities, which typically take a very broad view of the component parts of CCEE, risk making this approach hard to operationalise in research and particularly in policymaking. None of the elements included in CCEE in this literature is unreasonable. For example, leisure activities contribute to creating a vibrant environment that supports creative activities (Rieple et al., Citation2018; Tarani, Citation2011), intangible community value, and place identity – including physical dimensions (Gross & Wilson, Citation2019; Jung & Walker, Citation2018). But if intangible values, not-creative-businesses and physical buildings are included, at what point does the CCEE stop? How do the boundaries get drawn?

As Foster (Citation2020) highlights, CCEE are not confined within one “creative cluster”. Instead, they reach out to a wider geographical area, encompassing other businesses and institutions. The same point applies to neighbourhoods, cities and other fixed “space units”. For example, cities have international connections, physical or digital, and networks that involve other cities or regions. This has methodological consequences, as it may be important not to set the geographical boundaries of an ecological study in advance and instead to identify the boundaries of the CCEE on other principles, during the research process. For example, including in the CCEE only those cultural and creative actors identified as being actively involved in cultural and creative activity in the last six months; or focusing on a specific set of key actors, and then deducing the span of the ecosystem specifically in relation to their networks, some of which may be international.

Cultural and creative production networks often include firms that are not “creative” yet are absolutely essential, such as logistics businesses for distribution. Should these firms and individuals be included in the CCEE? Where does the creative sector end in practice? This is again a question of boundary-setting, with significant consequences in terms of who is involved in ecological approaches to cultural and creative sectors research and policy, including sampling decisions (for research) and funding/support decisions (for policy). Beyond the debate on which industries are or are not creative/cultural (Mato, Citation2009; Miller, Citation2009), these distinctions are often drawn for practical and policy purposes, with ongoing arguments for “inclusivity” challenging why certain voices remain excluded (Wilson et al., Citation2017). Similarly, Barker indicates that it is impossible to identify “the true boundaries” of a CCEE, because they are boundaryless systems: any perimeter tracing is artificial and imperfect. However, she proposes that the boundaries of an CCEE should be set in relation to the specific broader ecosystem relevant to the objectives of the research (Barker, Citation2020), such as the ecosystem of the creative industries or theatre sector. While this indicates one way forward, it leaves open a number of questions about how to identify what and who to include.

Methodological approaches to the study of CCEE

Among the limited uses of quantitative methods, three studies incorporate ecological notions most extensively, focusing on relational data. Blackstone et al. (Citation2016) employ Social Network Analysis (SNA) within a CCEE framework to investigate the consequences for individual artists of being rooted within local ecosystems. Similarly, Piterou et al. (Citation2020), use SNA to correlate the interconnectedness of creative firms with measures of innovation. Rieple et al. (Citation2018) look for patterns of “access” to ecosystem resources for designers. Researching dynamics not within one CCEE but between one CCEE and a particular dimension of the wider society, Stern and Seifert investigate the correlation between the presence of a neighbourhood cultural ecosystem – which in their methodology is identified via an aggregated index of several measures of cultural activity and participation – and community change and social wellbeing (Seifert & Stern, Citation2017). Mengi et al. study geographic distributions of creative industries, using the exact geolocation to identify creative ecosystems (Mengi et al., Citation2020); and although it makes conventional use of quantitative data gathering, Jeffcutt’s seminal work Knowledge relationships and transactions in a cultural economy: analysing the creative industries ecosystem (Citation2004) is an important example of using quantitative methods to investigate CCEE.

Qualitative methods have been used to record research participants’ perceptions regarding CCEE. This ranges from the most basic applications in which respondents were asked whether or not they perceive a CCEE to be at work (Gasparin & Quinn, Citation2020; Holden, Citation2015; Tarani, Citation2011), to detailed enquiries in which interviews are the means to outline internal structures and dynamics within cultural and creative processes and activities (Chung, Citation2016; Grabher, Citation2004). Due to the difficulties in identifying causal relations in complex social systems, qualitative methods have been valuable for investigating factors and phenomena affecting the evolution of particular CCEE (Jung & Walker, Citation2018; Mohamad & Walker, Citation2019). They have also been effectively used to examine the reciprocal relationship between a particular CCEE and its wider social context (Seifert & Stern, Citation2017), and to investigate the local conditions that enabled the emergence of cultural ecosystems in the first place (Patuelli, Citation2017).

The enquiries contributing the most significant novelty to the study of CCEE are those adopting mixed methods. Foster (Citation2020), for example, identifies the components of the ecosystem through quantitative data gathering and geolocation, then visualises relational data through SNA and analyses the motivation behind actors’ engagements within the ecosystems via interviews; and Dovey et al. (Citation2016) adopt a similar approach. Addressing a broader geographical scope, Markusen et al. (Citation2011) quantified the geographical presence of the cultural and creative sectors within California’s overall cultural ecology, followed by interviews with cultural organisations’ managers, examining their perspectives on the CCEE. Similarly, Stern and Seifert’s approach (Citation2017), in which cultural and creative sector activities and organisations are quantified and statistically correlated with features of community wellbeing, involves a qualitative phase (gathering data through a range of participatory methods) that investigates the explanatory factors behind the results found in the initial quantitative analysis. Stern and Seifert’s contribution is among the foundations on which New York City’s cultural strategy was developed (New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, Citation2017).

The use of mixed methods may be especially valuable due to the “methodological openness” (Wilson & Gross, Citation2017) that adopting an ecological framework can necessitate. These authors argue that to achieve a more open and inclusive research design, in terms of “a variety of ways of generating knowledge, and a broad range of people contributing”,

There is a need to set aside expectations of a single “birds eye view”, and develop an understanding of the cultural ecology from multiple perspectives, inclusively, and on an ongoing basis – responsive to the emergence, growth and evolution that is inherent to ecosystems. Developing co-produced, ongoing knowledge is both an epistemological and a political necessity. (Wilson et al., Citation2017, p. 4)

Discussion and conclusions

The value of a shared terminology

Before moving to our four proposals for a future research agenda, let us take stock and ask: what is the value of establishing a shared terminology and framework within which research on CCEE can be developed? We suggest that such a terminology and framework is valuable in several respects. It has the potential to enable researchers to develop work that speaks more effectively across disciplines and sites of cultural and creative practice. As discussed above, at present there is a wide range of work being undertaken in respect of CCEE, but too often conversations are taking place at cross-purposes, or not taking place at all. There is much to gain from enabling more sustained and better-quality conversations in this space, including the increased potential for ecological research to enable new forms of policy and management. Whilst there is a growing interest in CCEE within policymaking, it remains limited to a fairly small range of policymakers. Many more continue to operate terminologies and frameworks that treat policy as a linear process of pulling leavers and operating machines to achieve specified outcomes (Goss, Citation2020). Moreover, even for those policymakers sympathetic to ecological approaches there is an awareness that the language of “infrastructure” maintains its currency and efficacy within government (Gross & Wilson, Citation2019, pp. 61–62). In this context, developing a shared research agenda is needed not only to improve the overall quality of the empirical base of shared knowledge of CCEE. It is also needed to test and develop the potential for operating ecological terminologies – and ecological strategic frameworks – within policy processes in many locations.

Power relationships and analytical open-mindedness

To identify the value of this shared research agenda we should also reflect on why the language of CCEE has grown in recent years. Following the three-part categorisation of Gross and Wilson discussed in the critical literature review, there are good ontological, epistemological and policy reasons why ecological approaches are needed, as discussed throughout this paper. Here we reiterate one key point and introduce a new possibility. We suggested above that one of the reasons for the increased interest in ecological perspectives is the need to understand the cultural and creative sectors in ways better able to keep hold of the myriad respects in which culture and creativity matter: the many kinds of value at stake. Placing this point in a broader perspective, we should consider that the upsurge in use of this language is part of a wider concern with the relational nature of human activities, including the interconnections of humans with their environments of all kinds, and the new perspectives on questions of power that relational analysis opens up.

Several of the theoretical models we have reviewed in this paper are useful in identifying the most influential actors in a CCEE (Jung & Walker, Citation2018; New York City Department of Cultural New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, Citation2017; Schippers, Citation2016). However, it is imperative to contextualise these accounts of which actors matter most within specific, real-life circumstances to avoid another one-size-fits-all approach to research and policymaking. Different contexts could present completely different power relationships between particular actors and communities, including, for example, significant contrasts between situations in large metropolises, towns and rural areas. The differences might include the sets of values that motivate people to engage in specific activities within a CCEE, or the presence/absence within the territory of entire categories of resources or types of actor. One of the methodological consequences of this is the need for a preliminary exploratory phase, in order to avoid uncritically deploying an unfitting expectation of what a CCEE consists of in advance of a particular study, and from where most power will be exercised. It is crucial to pay open-minded attention to the specific power relationships within any particular CCEE. Not all the relationships, flows and exchanges between actors happen among “peers”, and even between supposed equals there are always complex power dynamics at play (Comunian, Citation2017). Unacknowledged power relations could lead to excluding entire categories of institutions or people, and to unintended policy consequences. This possibility is one of the criticisms of the CCEE concept made by some artists (Harker, Citation2019). But a failure to attend to power relations is by no means inherent to ecological approaches as such: indeed, they may be well-placed to develop more insightful understandings of how power is exercised within a complex system. And as Bailey et al argue, ecological perspectives can highlight the need for interventions – be it by policymakers, artists, activists, or other citizens – that deliberately cultivate new spaces of “critique” (Citation2019, p. 3) within the ecosystem.

Policymaking

Gross and Wilson propose an approach to managing cultural ecosystems which seek to “hold open spaces and structures”:

Notwithstanding the differences between them, flourishing ecosystems are typically highly connected, heterogenous and conducive to emergence. Our research indicates that effective ecological leadership will involve “holding open” conditions in which connections can be made, experiences shared, skills developed, and diverse practices of culture-making interact. Holding open spaces and structures is at the heart of ecological leadership. (Gross & Wilson, Citation2019, p. 4)

Policy documents have played an important part in the increased attention towards ecological approaches. This recent rise in policy documents addressed to CCEE represents a developing recognition that as the cultural and creative sectors have grown (in size, and in the diverse range of activities involved), policy has often been behind the curve – stuck with traditional frameworks for governance and support that have failed to properly engage with a wide range of constituencies within and beyond the cultural and creative sectors. It constitutes a growing acknowledgement that cultural governance structures (nationally, and at a range of local levels) are often based on unhelpful binaries (funded vs. not-funded; producers vs. audiences; public vs private; national vs. international; regional vs. national etc.). They can thereby fail to grasp the lived realities of CCEE, and in some cases are unfit for purpose. The fact that research has been initiated by a range of policy bodies to develop ecological understandings indicates the willingness (of some of policymakers, at least) to challenge existing modes of funding, planning and support: potentially reaching a wider range of social actors, and more fully supporting CCEE to flourish “inclusively”.

However, whilst the potential for ecological approaches to benefit policy opens up positive opportunities, it also presents challenges. Ecological understandings pose difficult questions regarding where policy is best placed to intervene, support or regulate CCEE, with the complexity of CCEE potentially discouraging policymakers from making confident interventions.

Four proposals for future research

After reviewing this extensive set of publications, here we put forward four suggestions for future research, proposing that a clarified research agenda will have benefits for scholarship and for policymaking. Outlining this agenda – calling for interdisciplinary collaboration and a clarified terminology, emphasising the importance of paying attention to the contestation of value, and connecting with discussions of climate change – there is the potential for a generative unity in diversity: a shared framework within which many different researchers and policymakers can contribute.

This paper affirms and develops Comunian’s proposal (Citation2019) that the understanding of complex adaptive systems like CCEE requires the input from a diversity of disciplines, including a wide range of methods and research tools. The opportunity for CCEE to be a common object of study across anthropology, economic geography, sociology, regional studies and many other disciplines offers great prospects for future developments. However, a multi-disciplinary approach needs to be adopted to consider how each discipline can contribute to the bigger picture. With reference to scale of analysis, it is clear that different subject areas and research projects might operate at specific scales. However, awareness of the implications of adopting a particular scale of analysis is needed – in part to allow research at other scales to be connected and contrasted with greater clarity and precision, benefitting from each other’s findings.

In reference to definitional matters, we stress the importance of distinguishing between cultural and creative ecology as the study or approach, and cultural and creative ecosystems as the object of study. This clarification of terminology – and the consistency in the use of these terms across the field – would benefit dialogue and exchange in this area of research. We also suggest that the use of cultural and creative together can provide a more inclusive framework, able to encompass both the more narrowly defined creative (industries/workers) ecosystem and the broader cultural ecosystem. Ecological approaches require – and demonstrate the need for – the involvement of many different sub-sectors and communities in the study of culture and creativity. Referring to cultural and creative ecosystems is the terminology best able to hold this range of activities and populations within the same frame of analysis.

In addition to the ontological inclusivity of “creative and cultural” – incorporating a wide range of activities and populations – the phrase is useful for making visible the need to address questions of value when undertaking ecological research of this kind. The debate over the definition of the creative industries and whether to revert to the pre-existing notion of the cultural industries is in part a question of value (Gross, Citation2020). Are these areas of activity regarded as important due to their contribution to jobs and GDP? Is their value primarily located in their operating as a key site of meaning-making, helping to make life good and enjoyable, in their capacities to imagine different worlds, to challenge the status quo, and even in some sense to provide the basis for social, political and economic change? Or to what extent can the answer be both? “Cultural and creative ecosystem” is a good choice for the future research agenda we are pointing towards due to its pragmatic value as inclusive of a wide range of methodologies, disciplinary approaches and objects of study, but also because it holds together – in a generative tension – the questions of value that these long-standing debates between “creative industries” and “cultural industries” raise. Within CCEE research and policymaking, using the phrase cultural and creative ecosystems can make visible these key questions of value, holding them up to ongoing scrutiny and debate, rather than skating over them.

Our systematic literature review deliberately did not include research from environmental sciences and ecosystem services. The 56 publications do not address questions of biodiversity loss, climate change or ecological breakdown. But we can consider that the rise in ecological thinking about the cultural and creative sectors is part of a broader rise of relational thinking in the humanities and social sciences that has as one of its driving influences the increasingly urgent need to act in ways that fully recognise the interdependencies of human life and the earth’s systems. There is a growing literature which reflects on cultural practices that have planetary care at their core. In this respect, ecological thinking can play an important role in bridging CCEE with social, ethical and environmental justices (Demos et al., Citation2021). This points towards one further dimension of a future agenda for CCEE research: namely, to build upon the small but emerging body of research addressing CCIs and the environmental crisis (Miller & Maxwell, Citation2017; Oakley & Banks, Citation2020) by explicitly bringing it together with the potential for ecological analysis outlined in this paper. Such work would need to engage with the three dimensions of the research agenda outlined above: particularly the need to attend to the contestation of value – which draws in questions of how to set epistemological boundaries upon the ecosystems that researchers and policymakers seek to study and influence – and the contestation of power within cultural and creative ecosystems. In addition to which, such research would need to explore possibilities for the greater inclusion of “material” dimensions within ecological analyses. Not all ecological analyses will be able to engage in depth with all such questions. But collectively, as part of the overall research agenda we are proposing, they need to be part of the collective project.

This paper has offered an analysis of existing research on cultural and creative ecologies and ecosystems, which we have referred to throughout the paper as “CCEE”, grouping together a wide range of closely related terms and definitions. In making our four proposals for how to coordinate across the different perspectives and definitions adopted by a range of authors and disciplines, we propose a standardisation, using cultural and creative ecosystem to name this complex object of study and policy, and cultural and creative ecology as the study or approach. As we have shown, scholars make different choices in terminology between creative and cultural, and between ecology and ecosystem, whilst often addressing the same or similar phenomenon. Hence, it is essential to try to clarify these vocabulary choices, reflecting on the theoretical roots of the terms, their differences and overlaps. In response to these terminological and definitional challenges, the paper has offered a comprehensive review of CCEE literature. It has discussed what a cultural and creative ecosystem is, because the discipline that attempts to study these systems must address this foundational ontological question, as well as to critically reflect on existing and potential methodologies. We specifically looked at the ways quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods approaches have been employed within this area of research. In particular, we highlighted that the adoption of different methodological frameworks has implications for how cultural and creative ecosystems are studied and what components are included or excluded. We also considered the limitations – and the criticisms that have been made – of ecological concepts and their use, including the lack of recognition of power dynamics. In these ways, we have identified key points of tension, uncertainty and possibility within this emerging field, and on this basis have proposed a set of directions for future research.

The study of cultural and creative ecosystems is an emerging field of research. It builds on existing literature, from ecosystem services to cultural mapping. However, in this paper we have argued that more clarity is needed in the use of key terms, in the scope and application of methods, and in the possibilities for policymaking to build on this research in new forms of cultural and creative governance. In outlining an agenda for future research, we seek to help consolidate the field, and to enable researchers to coordinate research efforts – especially in consideration of methodological and theoretical choices – to inform the dynamic and democratic development of cultural and creative ecosystems in practice. CCEE should not be seen simply as a new label for old phenomena (“creative clusters”, “creative industries”, even “cultural participation”, etc.), but as a new framework with which to study interconnected domains of cultural and creative activity that enables researchers to stretch and connect their understandings across subject areas and scales (micro, meso and macro). It can allow researchers to focus on their specific concerns while locating their work and findings within a bigger systemic picture that they can engage with and contribute to. This has the potential to shed new light on the interconnections and interdependences not only within particular cultural and creative ecosystems, but between cultural and creative ecosystems and the wider socio-economic and political systems in which they exist and evolve.

We conclude by reflecting on how this area of research might become even more central to cultural policy researchers in the aftermath of Covid-19. Beyond the impact of Covid-19 on the public funding available to “culture”, which in some countries may well limit options for simple top-down interventions, Covid-19 has made visible human (and broader biological) interconnectedness and interdependency both at the global and at the hyper-local level, and therefore the need for a more systemic approach to policy and progressive social change in general. This could be acted upon, we suggest, by developing new participatory and deliberative approaches to policymaking: “ecological policymaking” (Gross et al., Citation2020) for cultural and creative ecosystems and beyond, developing sustained spaces for radically inclusive processes of information-sharing, deliberation and decision-making, in which human interdependence – and the interconnectedness of many kinds of cultural and creative activity – is a guiding principle.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 For brevity, throughout this paper we use the acronym CCEE, rather than writing “cultural and creative ecologies and ecosystems” in full each time. We use this compound term to draw together the many closely related terms found within the literature. However, in some places in the text, (where helpful), when authors use specific terminology we employ the term they use. As discussed in the conclusion, we ultimately propose that researchers and policymakers adopt a shared terminology, using “cultural and creative ecosystems” to refer to this complex object of study and policy. “Cultural and creative ecology” is the study or approach.

References

- Arts Council England. (2008). Our Creative Talent: The Voluntary and Amateur Arts in England. Arts Council England.

- Arts Council England. (2014). This England: How Arts Council England Uses Its Investment to Shape a National Cultural Ecology. Arts Council England.

- Bailey, R., Booth-Kurpnieks, C., Davies, K., & Delsante, I. (2019). Cultural ecology and cultural critique. Arts, 8(4), 166–185. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8040166

- Bakalli, M. (2015). The Creative Ecosystem: Facilitating the Development of Creative Industries. United Nations Industrial Development Organization.

- Barker, V. (2020). The democratic development potential of a cultural ecosystem approach. Journal of Law, Social Justice and Global Development, (24), 86–99. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.31273/LGD.2019.2405

- Blackstone, M., Hage, S., & McWilliams, I. (2016). Understanding the role of cultural networks within a creative ecosystem: A Canadian case-study. Journal of Cultural Management and Policy, 6(1), 13–29.

- Borin, E., & Donato, F. (2015). Unlocking the potential of IC in Italian cultural ecosystems. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 16(2), 285–304. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-12-2014-0131

- Byrne, D. (1998). Complexity Theory and the Social Sciences: An Introduction. Psychology Press.

- Chung, H.-L. (2016). Cultural creative industries policies in Urban networks: Case Study design for research on the Six municipalities in Taiwan. International Journal of Cultural and Creative Industries, 3(3), 18–31.

- Comunian, R. (2017). Creative collaborations: The role of networks, power and policy. In M. Shiach & T. Virani (Eds.), Cultural Policy, Innovation and the Creative Economy (pp. 231–244). Springer.

- Comunian, R. (2019). Complexity thinking as a coordinating theoretical framework for creative industries research. In S. Cunningham & T. Flew (Eds.), A Research Agenda for Creative Industries (pp. 39–57). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Comunian, R., Rickmers, D., & Nanetti, A. (2020). Guest editorial: The creative economy is dead–long live the creative-social economies. Social Enterprise Journal, 16(2), 101–119. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/SEJ-05-2020-085

- Davies, D., Howe, A., & Haywood, S. (2004). Building a creative ecosystem–The young designers on location project. International Journal of Art & Design Education, 23(3), 278–289. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1476-8070.2004.00407.x

- de Bernard, M., & Comunian, R. (2021). Creative and Cultural Ecosystems: Visual Models and Visualisation Challenges. Retrieved June 11, 2021, from https://www.creative-cultural-ecologies.eu/research-blog/creative-and-cultural-ecosystems-visual-models-and-visualisation-challenges

- Demir, O. (2018). Looking forward for istanbul's creative economy ecosystem. Creative Industries Journal, 11(1), 87–101. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17510694.2018.1434361

- Demos, T., Scott, E. E., & Banerjee, S. (2021). The Routledge Companion to Contemporary Art, Visual Culture, and Climate Change. Routledge.

- Dillon, P., & Kokko, S. (2017). Craft as cultural ecologically located practice: Comparative case studies of textile crafts in Cyprus. Estonia and Peru. Craft Research, 8(2), 193–222. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1386/crre.8.2.193_1

- Dovey, J., Moreton, S., Sparke, S., & Sharpe, B. (2016). The practice of cultural ecology: Network connectivity in the creative economy. Cultural Trends, 25(2), 87–103. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09548963.2016.1170922

- Foster, N. (2020, January). From Clusters to Ecologies: Rethinking Measures, Values and Impacts in Creative Sector-Led Development [Conference Paper]. Creative Industries Research Frontiers Seminar Series, London, UK.

- Galatenau, E., & Avasilcai, S. (2017). Emerging creative ecosystems: Platform development process. Annals of the Oradea University, Fascicle of Management and Technological Engineering, 2017(3), 5–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.15660/AUOFMTE.2017-3.3296

- Gasparin, M., & Quinn, M. (2020). Designing regional innovation systems in transitional economies: A creative ecosystem approach. Growth and Change, 52(2), 621–640. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/grow.12441

- Gollmitzer, M., & Murray, C. (2008, March 17–18). From economy to ecology: A policy framework for creative labour. Canadian Conference of the arts, Ottawa, ON.

- Goss, S. (2020). An Eco-System View of Change and a Different Role for the State. Compass.

- Grabher, G. (2004). Learning in projects, remembering in networks? Communality, sociality, and connectivity in project ecologies. European Urban and Regional Studies, 11(2), 103–123. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776404041417

- Gross, J. (2020). The Birth of the Creative Industries Revisited: An Oral History of the 1998 DCMS Mapping Document. King’s College London, London.

- Gross, J., Comunian, R., Conor, B., Dent, T., Heinonen, J., Hytti, U., Hytönen, K., Pukkinen, T., Stenholm, P., & Wilson, N. (2019). DISCE Case Study Framework. DISCE Publications. https://disce.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/DISCE-Report-D3.1-D4.1-D5.1.pdf

- Gross, J., Heinonen, J., Burlina, C., Comunian, R., Conor, B., Crociata, A., Dent, T., Guardans, I., Hytti, U., Hytönen, K., Pica, V., Pukkinen, T., Renders, M., Stenholm, P., & Wilson, N. (2020). Managing Creative Economies as Cultural Eco-Systems. DISCE Publications. https://disce.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/DISCE-Policy-Brief-1.pdf

- Gross, J., & Wilson, N. (2018). Cultural democracy: An ecological and capabilities approach. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 26(3) ), 328–343. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2018.1538363

- Gross, J., & Wilson, N. (2019). Creating the Environment: The Cultural Eco-systems of Creative People and Places. http://www.creativepeopleplaces.org.uk/our-learning/creating

- Harker, K. (2019). Seeing beyond a false ‘ecology’ for visual arts in the north. In L. Eggleton & A. Friedli (Eds.), Resistance is Futile (pp. 67–80). Corridor 8 and Yorkshire & Humber Visual Arts Network.

- Holden, J. (2004). Capturing Cultural Value: How Culture has Become a Tool of Government Policy. Demos. https://www.demos.co.uk/files/CapturingCulturalValue.pdf

- Holden, J. (2015). The Ecology of Culture: A Report Commissioned by the Arts and Humanities Research Council’s Cultural Value Project. Arts and Humanities Research Council. http://www.ahrc.ac.uk/documents/project-reports-and-reviews/the-ecology-of-culture/

- Hornby, A. S., & Cowie, A. P. (1995). Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary (Vol. 1430). Oxford University Press.

- Jeffcutt, P. (2004). Knowledge relationships and transactions in a Cultural Economy: Analysing the creative industries ecosystem. Media International Australia Incorporating Culture and Policy, 112(1), 67–82. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X0411200107

- Jung, J., & Walker, S. (2018). Creative ecologies. In S. Walker, M. Evans, T. Cassidy, J. Jung, & A. T. Holroyd (Eds.), Design Roots: Local Products and Practices in a Globalized World (pp. 11–24). Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Knell, J. (2007). The Art of Living. Retrieved October 21, 2021, from https://www.culturehive.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/23974645-The-Art-of-Living-by-John-Knell-2007_0.pdf

- Markusen, A., Gadwa, A., Barbour, E., & Beyers, W. (2011). California's Arts and Cultural Ecology. Retrieved October 21, 2021, from https://www.irvine.org/wp-content/uploads/CA_Arts_Ecology_2011Sept20.pdf

- Mato, D. (2009). All industries are cultural: A critique of the idea of ‘cultural industries’ and new possibilities for research. Cultural Studies, 23(1), 70–87. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380802016212

- Mengi, O., Bilandzic, A., Foth, M., & Guaralda, M. (2020). Mapping brisbane’s casual creative corridor: Land use and policy implications of a new genre in urban creative ecosystems. Land Use Policy, 97, 104792. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104792

- Merli, R., Preziosi, M., & Acampora, A. (2018). How do scholars approach the circular economy? A systematic literature review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 178, 703–722. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.12.112

- Miller, T. (2009). From creative to cultural industries: Not all industries are cultural, and no industries are creative. Cultural Studies, 23(1), 88–99. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380802326660

- Miller, T., & Maxwell, R. (2017). Greenwashing Culture. Routledge.

- Mohamad, S. A., & Walker, S. (2019, November 23–24). The impact of globalization on the creative ecology of a heritage village: A case study from Malaysia. Proceedings of the international conference on Islamic Civilization and Technology Management, Terengganu, Malaysia.

- Neelands, J., Belfiore, E., Firth, C., Hart, N., Perrin, L., Brock, S., Holdaway, D., Woddis, J., & Knell, R. J. (2015). Enriching Britain: Culture, Creativity and Growth: 2015 Report by the Warwick Commission on the Future of Cultural Value. University of Warwick. https://warwick.ac.uk/research/warwickcommission/futureculture/finalreport/warwick_commission_final_report.pdf

- New York City Department of Cultural Affairs. (2017). Create NYC: A Cultural Plan for All New Yorkers. https://createnyc.cityofnewyork.us/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/CreateNYC_Cultural_Plan.pdf

- Oakley, K., & Banks, M. (2020). Cultural Industries and the Environmental Crisis. Springer.

- Patuelli, A. (2017, September). Exploring Cultural Ecosystems: The Case of Dante 2021 in Ravenna. Click, Connect and Collaborate! New Directions in Sustaining Cultural Networks.

- Petticrew, M., & Roberts, H. (2008). Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide. John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470754887

- Piterou, A., Chan, J. H., Lean, H. H., Khoo, S. L., & Mohd Hashim, I. H. (2020, January). Mapping the Creative Ecology of a World Heritage Site: Creative and Cultural Clusters as Social Networks. Creative Industries Research Frontiers Seminar Series.

- Poprawski, M. (2019). New organisms in the cultural ‘ecosystems’ of cities: The rooting and sustainability of arts and culture organizations. In W. J. Byrnes & A. Brkić (Eds.), The Routledge Companion to Arts Management (pp. 278–295). Routledge.

- Potts, J., Cunningham, S., Hartley, J., & Ormerod, P. (2008). Social network markets: A new definition of the creative industries. Journal of Cultural Economics, 32(3), 167–185. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-008-9066-y

- Pratt, A. C. (2002). Hot jobs in cool places. The material cultures of new media product spaces: The case of south of the market. San Francisco. Information, Communication & Society, 5(1), 27–50. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13691180110117640

- Rieple, A., Gander, J., Pisano, P., Haberberg, A., & Longstaff, E. (2018). Accessing the creative ecosystem: Evidence from UK fashion design micro enterprises. In E. G. Carayannis, G. B. Dagnino, S. Alvarez, & R. Faraci (Eds.), Entrepreneurial Ecosystems and the Diffusion of Startups (pp. 117–138). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4337/9781784710064

- Roodhouse, S. (2011). The creative industries definitional discourse. In C. Henry & A. de Bruin (Eds.), Entrepreneurship and the Creative Economy. Process, Practice and Policy (pp. 7–29). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4337/9780857933058

- Schippers, H. (2016). Cities as cultural ecosystems: Researching and understanding music sustainability in urban settings. Journal of Urban Culture Research, 12, 10–19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.14456/jucr.2016.1

- Seifert, S., & Stern, M. (2017). Divergent Paths–Rapid Neighborhood Change and the Cultural Ecosystem. Retrieved October 21, 2021, from https://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1007&context=siap_culture_nyc

- Stern, M., & Seifert, S. (2017). The Social Wellbeing of New York City's Neighborhoods: The Contribution of Culture and the Arts. Retrieved October 21, 2021, from https://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1001&context=siap_culture_nyc

- Steward, J. H. (2006). The concept and method of cultural ecology. The Environment in Anthropology: A Reader in Ecology, Culture and Sustainable Living, 1(1), 5–9. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18574/9781479862689-003

- Tarani, P. (2011, October). Emergent creative ecosystems: Key elements for urban renewal strategies. THE 4TH KNOWLEDGE CITIES WORLD SUMMIT, Bento Gonçalves, Brazil.

- Wilson, N. (2010). Social creativity: Re-qualifying the creative economy. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 16(3), 367–381. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10286630903111621

- Wilson, N., & Gross, J. (2017). Caring for Cultural Freedom: An Ecological Approach to Supporting Young People's Cultural Learning. A New Direction. https://www.anewdirection.org.uk/research/cultural-ecology

- Wilson, N., Gross, J., & Bull, A. (2017). Towards Cultural Democracy: Promoting Cultural Capabilities for Everyone. Cultural Institute, King's College of London. https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/files/117457700/towards_cultural_democracy_2017_kcl.pdf