ABSTRACT

Inclusivity is an underlying principle of community arts, particularly for learning disabled and autistic people for whom the arts can create spaces of equity and inclusive participation. The Covid-19 pandemic required practitioners to find ways of replicating this sense of inclusivity through online delivery. This “digital turn” raised two recurring concerns. First, the accessibility and inclusivity of online activities; second, the quality of alternative digital provision. This paper examines these themes in the specific context of the Creative Doodle Book, which modelled inclusive online practice with learning disabled participants. Drawing on over 20 interviews with learning-disability focused community arts groups, the paper explores barriers to access, but also issues surrounding support and expectations. However, the focus is equally on the benefits once within an online “space”, including new skills, widening networks, the development of inclusive capital and the opportunity to enable greater agency and self-advocacy both during Covid and beyond.

Introduction

Inclusivity is an underlying principle of community art and a vital component of cultural democracy. This is particularly the case when working with learning disabled and autistic people, for whom the arts can create spaces of equity and inclusive participation. Almost invariable this inclusiveness has been premised on in-person delivery, involving the careful facilitation of arts practice with people in the same space as one another. As with every other aspect of our society, the Covid-19 pandemic of 2020–2022 disrupted community arts and required practitioners to radically adapt and find ways to replicate this sense of inclusiveness while physically apart. Indeed, one consequence of social distancing and lockdowns during this period was a shift to various forms of online delivery. While not entirely non-existent prior to 2020, participation in online arts increased exponentially as people took part in virtual choirs, zoom choreographies, live-streamed performances, online arts workshops and much, much more.

This “digital turn” within community arts (Camlin & Lisboa, Citation2021) has raised two recurring concerns. First, the accessibility and inclusivity of online activities; second, the expectations of and satisfaction with the quality of the alternative digital provision. This paper examines these two themes through the perspective and insights of the Creative Doodle Book project, funded by UKRI as part of the rapid response scheme to Covid-19 (AH/V011405/1). This practice-based project sought to investigate, model and disseminate inclusive online community arts during social distancing. While the Creative Doodle Book was used with a diversity of groups, including in schools, care homes and mental health contexts, the focus of this paper is on its use working with people with learning disabilities – a group who were amongst the most negatively impacted upon by Covid-19 (McCausland et al., Citation2021).

By positioning this new online practice in terms of “community arts”, this paper aligns the sometime seemingly political neutral concept of “inclusivity” with the explicitly political objectives of cultural democratisation (Kelly, Citation1984). The ideological focus of community arts is specified upon using creative practice to provide opportunities for voice and expression to marginalised individuals and communities (Bishop, Citation2012, p. 177). The specific context of learning disability arts underlines how without access and inclusivity there can be no cultural democracy – there can be no social justice. Inclusive community arts, and the practice discussed within this paper, precisely seeks to manifest the social mode of disability (Calvert, Citation2015; Hargrave, Citation2015).

Underpinned by this vital political orientation, this paper first sets out its practice-based, methodological and critical contexts: the first is the Creative Doodle Book itself; the second a series of extensive practitioner interviews; and the third the intersection between inclusivity, community arts and emerging online practices. Drawing on over 20 practitioner interviews, the paper then presents its core insights relating to both the significant barriers to access – notable digital poverty, but also learning disability specific issues surrounding support and expectations – but also the potential benefits once within an online “space”. The conceptual framework throughout is the elusive concept of “inclusivity”, or what Simon Hayhoe terms “inclusive capital” (Citation2018), viewed less as a static endpoint and more as an ever-shifting series of relationships, attitudes, adjustments and designed to create a “sense of belonging” (Hall, Citation2010).

This paper proposes there are some notable opportunities, including new skills, widening networks and inclusivity gains, to carefully considered online practice – together these form the potential to actively address the digital divide and build inclusive capital amongst both practitioners and participants. Although there will always be a drive to return to physical and in-person delivery, participation in digital life and culture is an equally important element of social inclusion. There are therefore insights and practices from the Covid-19 experience that we should actively seek to continue in an inclusive and creatively enabling post-pandemic world. (Note on language: except in direct quotations, this paper adopts identity-first language.)

The Creative Doodle Book project

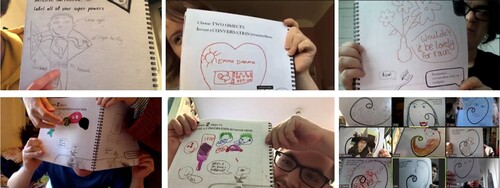

The Creative Doodle Book (CDB) is a physical resource that uses open and playful tasks to encourage creativity, mindfulness and positive reflectivity (see and for example page). The setting of creative tasks is a common feature in arts pedagogy, with the CDB inspired by the work of Keri Smith (Wreck this Journal Citation2013) and Julia Cameron (The Artist’s Way Citation1992). It was originally produced through a collaborative research process with learning disabled artists from Mind the Gap prior to Covid-19, but was quickly reconceived as a useful tool in a remote working context.

Working in collaboration with Mind the Gap, and access champions Totally Inclusive People, the CDB project incorporated distribution of the physical book to members of participating groups, supported by the delivery of a series of online workshops. The book represented a tangible in-the-hand object underpinning the remote online practice.

Between November 2020 and July 2021, the project worked directly with 31 different organisations, delivering over 115 workshops. lists the 21 learning disability groups which participated in the project, predominantly arts focused but also SEND departments within schools and self-advocacy organisations. All interviewees quoted within this paper gave consent for themselves, and their organisations, to be named as part of the research. This enables direct acknowledgement of the vital experience and knowledge that practitioners brought to this research.

Table 1. Learning disability organisations participating in Creative Doodle Book Project.

The reception of the CDB from participating organisations was overwhelmingly positive and accompanied by assertions that the experience would have a lasting impact on practice, both online and beyond:

I love it. I think it is a really nice piece of work, and will be something that we will go on using and spark ideas from. (About Face)

I certainly, from my point of view, will be taking stuff forward into the studio when we return to in-person work, as an alternative to the ways that we have been working in the past. (Into the Sky)

Methodology

The Creative Doodle Book project was a practice-led engagement with inclusive community arts at a moment of extreme crisis and transformation. A primary research focus for the project was how community arts organisations and practitioners adapted to the digital turn in delivery required by Covid-19, and the impact of this on inclusion and quality. The objective was to develop policy and practice implications for the future development of online community art. This paper draws primarily from one element of the methodology, a series of practitioner (or “expert”) interviews conducted with the community arts practitioners during the course of the project.

The “expert interview” is an established qualitative approach that focuses on exploring practitioner knowledge accumulated within a specific and defined field. Schön characterises a professional practitioner as “a specialist who encounters certain types of situation again and again” (Citation1983, p. 60). Within an interview what is often implicit knowing-in-action is made explicit through reflective processes (reflection-on-action), as together the practitioner and interviewer raise to the surface tacit observations and understandings. Kay Hepplewhite usefully defines the expertise of the applied theatre practitioner as “combining artistic and developmental concerns” that is conditional on the responsive nature of applied theatre (Citation2020, p. 7). Exploratory expert interviews can be utilised to establish the basis of a new field of study, while theory generating expert interviews draw upon analysis across several individual statement to begin to formulate new theories and understandings of practice (Bogner et al., Citation2009). For this project, the expert interviews took place over Zoom, primarily with each group’s lead practitioner, and were semi-structured, following a series of open questions which were circulated in advance. As well as exploring the impact of and responses to the CDB project, these interviews also collected each company’s “Covid story”, examining the impact of the pandemic upon themselves and their members and how they had adapted to lockdown and social distancing restrictions.

Early in the research design a decision was made not to systematically collect and analyze completed Creative Doodle Books. Although this would have provided fascinating insight into participants’ experiences of Covid-19, lockdown and isolation, it was felt that it had the potential to transform a valuable expressive arts experience into something research focused. Given the vulnerability of some of the participants, and the particular circumstances of the pandemic, there was an ethical imperative in letting participation be unobserved and of purely intrinsic value. Moreover, there were several active reasons why the research questions for this project lent themselves to the adoption of an expert interview approach and a focus on practitioner perspective.

Covid-19 and the digital turn presented experienced community arts practitioners with a particular and acute circumstance where their accumulated knowing-in-action was at least in part disrupted. Expert practitioners found themselves novice in one element of their practice, online delivery, while crucially maintaining that reflectivity as professional practitioners. This was particularly fertile ground for the expert interview, in which our conversations were happening almost simultaneously with moments of professional discovery and new learning.

The evidence presented here, therefore, represents the insights and learning from practitioners bringing their accumulated expertise and understanding (about learning disability, about arts facilitation, about inclusive practice) to the reflective and responsive consideration of what was for them a new and unique circumstance – that of digital adaptation and delivery. This material was then analysed to generate new theories about this new circumstance, relating to the key research questions of (1) online inclusivity in community arts; (2) quality of provision in online community arts.

Inclusive? Access, universal design and inclusive capital

The concept of “inclusive” has already been prominent within this paper, as it was in the Creative Doodle Book project, which proposed to model and explore inclusive community arts during Covid-19. Indeed, as discussed in the introduction, inclusivity is a foundational principle of community arts, essentially to the goals of cultural democracy and social justice. This section will interrogate what is meant by “inclusive practice”, particularly in the arts. In doing so discussion draws upon discourses from inclusive education, disability activism, the community arts and design theory.

There is often a blurring between ideas and terminology of “access” and a broader philosophy of inclusion, and while hard distinctions are likely impossible some differentiation is conceptually useful. Accessibility most immediately relates to various logistical relationships, which might include getting into a building (and the need for step-free access) to specific access systems within a space (signing, audio description etc). Access questions might also incorporate elements relating to cost, travel, barriers to joining and knowledge. Access is therefore a fundamental starting point and requirement. However it can be treated as a process of ad-hoc adjustments that in practice re-enforce distinctions in a hierarchical way – a ramp at the rear of a building, for example, is accessible, but not inclusive – or which don’t enable meaningful inclusion. John Lee Clark goes even further, writing from a DeafBlind perspective that access adaptations can seem like poor replicas: “divorced from the original […] sorry excuses for what occasioned them in the first place” (Citation2021, np).

If done unreflexively, access adjustments or adaptations as variations to a norm do not change or impact upon that norm or on normative practice. In the context of education, for example, Waterfield and West distinguish between the offering of “alternative approaches” which “reproduce the notion of “disabled” as “different” and a truly inclusive approach in which all opportunities were available to all students” (Citation2006, pp. 18–19). Or in the context of the arts, where for Bree Hadley a fully inclusive performance – or by extension any other arts practice – would incorporate accessibility “as an integral part of the aesthetic”, rather than adaptations that run alongside (Citation2022). This is what has been termed “universal design”, sometimes also known as “inclusive design” or “design for all” (Burgstahler, Citation2015, p. 70). Central to this approach is the understanding that environments or resources should be designed in a manner that can be accessed, understood and used to the greatest extent possible by all people. For Halder and Argyropoulos for example, “The general policy of universal design was planned to respond to the widest possible audience with the minimum possible adaptations and the highest possible access” (Citation2019, p. 5).

An interesting example of this relationship between access and inclusion is found in Fletcher-Watson and May’s (Citation2018) analysis of the Autism Arts Festival, held in Canterbury, UK. Their discussion details the variety of access tools provided and the structuring of the event as not just offering relaxed performances but “relaxed venues”. They describe conflicts in access needs – “You’ll find some who say, ‘It wasn’t loud enough’ or ‘It was too loud (414)’” – and note the relatively low up-take of any one single access aid. As Hadley observes, the challenges of disability access are “compounded by the fact that disability, as a category, brings together individuals with a spectrum of sometimes conflicting needs, interests and desires” (Citation2022). This requires a continual and conscious negotiation of what Jess Watkin (Citation2021), drawing on co-created dialogues taking place across #DisabilityTwitter, describes as “access tensions”. The recognition of the existence of such tensions need not be negative, drawing them to the surface is in itself an inclusive attitude – it requires paying serious and sustained attention to the real complexity of multiple and diverse needs. It begins to pay attention to something that goes beyond access, and is better thought of as inclusion, describing as much an attitude or ethos as a set of measures or adaptations. Within the framework of the community arts, an inclusive practice incorporates the political imperative to challenge and de-centre previously normative positions. To this end, in their conclusion Fletcher Watson and May suggest that while the Autism Arts Festival offered various access tools, it was the establishment of an inclusive “autistic space” that was most impactful and significant.

Inclusion, therefore, clearly requires access but also what Sailaja Chennat describes as an “outlook, a conviction and a philosophy”:

Inclusion is a way of implementing the democratic principles of equality and justice

with acceptance and conviction so that every individual of the group feels accepted,

valued and safe. (Citation2019, p. 39)

While Hall suggests belonging and bonding as forms of social capital, Simon Hayhoe coins the phrase “inclusive capital” to describe our sense of inclusion, premised upon social and cultural processes of feeling valued within networks and connections (Citation2018, pp. 125–128). As with other forms of both economic and non-economic capital, inclusive capital is unequally distributed within society, not least for disabled people for whom a lack of inclusive capital “leads to a lessening of their sense of inclusion in mainstream society, and to a growing sense of social exclusion and isolation” (p. 127). The digital turn prompted by Covid-19 requires that we think about how inclusive capital is distributed in online environments and how policy and practice might ensure that new exclusions are not generated or re-enforced.

The Creative Doodle Book project emerged from and enters into dialogue with these discourses, informed not least from its embedded development with Mind the Gap. The project begun with an inclusive design process where we worked with learning disabled and autistic artists to develop the concept of the book. Its form was orientated to be “accessible” to this original co-creative context and some access adaptations became necessary for other participants – for example a braille version was made available; while the workshops included description of all the written material. However, the philosophy of universal design describes less the look of the book as an object, but rather how it sought to engage with participants through “open” tasks. Open in that there is no right or wrong way of responding, they can be done multiple times with multiple different responses, and they can be completed creatively by people with all sorts of different artistic abilities and interests. This was central to the design of the book and the workshops and was picked up upon by many of the practitioners:

I like the open endedness of it. I like that it gives you a starting point. It can lead to all sorts of things, which is quite unexpected. It feels that it’s just an opportunity to be creative, therefore, it’s open to anybody. (About Face)

The thinking, intentionality and values of the project can therefore be considered in terms of the development of inclusive capital. The combination of physical book and supporting workshop were designed to construct bonds and connections between all participants, to generate a sense of inclusion as the starting point, rather than a secondary add on. This structure enabled multiple ways of engagement, support and response; valuing all contributions, with everyone responding to the same shared starting point. This produced a sense of inclusion, of being within the conversation and of belonging that was tangible to those working with the process:

To hear how much deep thinking has been going on around [inclusivity] is always just heartening and exciting. How do you find the thing that invites everyone to it in a way that is accessible and interesting to everybody, is such an interesting challenge for to grapple with. (Confidance)

Online practice, access and inclusivity

The Covid-19 pandemic drew attention to inequalities across many areas, with the acceleration towards online services emphasising the existence of a digital divide, and the potential to exclude people from online activities due to lack of knowledge, poverty or accessibility reasons. Indeed, Price et al, report that some community music groups resisted online delivery for this reason, motivated by “a perception that having no session was preferable to one that highlighted the digital inequality among members” (Citation2021). It is noticeable that, while very much aware of the potential exclusions, none of the learning disability arts organisations participating in this research took this attitude and all of them opted to run some digital provision. The main reason for this was an awareness that their value to their members would only be increased by the pressures and isolation of lockdown. This is captured by Laura Bassenger, who commented that “For so many of our members, Starlight is literally a lifeline. It’s all they have to get up for in the morning. And having that taken away from them was a real concern” (Starlight).

The possibilities of exclusion from online spaces are significant. Geoff Watts writes in The Lancet that while around 10% of the adult population in the UK are internet non-users, public policy often proceeds as if access to the internet were universal (Citation2020, p. 395). Watts describes three broad elements as contributing to the digital divide: lack of access (mostly to technology and data, largely due to cost); lack of motivation (people don’t believe it is relevant to their lives); and lack of skills and education. In the specific context of digital access for people with learning disabilities the evidence in this paper suggests additional factors relating to support – covering the resources, attitudes and perceptions of support networks (whether families or professional carers).

For community arts practitioners the shift to online delivery presented radical challenges to established approaches to inclusivity and discussion of the barriers to online access – cost, motivation, skills and support – occurred frequently in the interviews. Yet an equally recurring motif was that of a rapid, committed and extremely impactful shift to online delivery. What makes this even more remarkable is the extremely low base from which this shift began. Of the participating companies, very few of them reported having any significant prior experience of online delivery. The majority also reported low levels of technological confidence or resources, with few having previously delivered online workshops or practice. As noted at the top of this paper, the formative and guiding principle of the community arts is that of doing things together, and prior to Covid-19 that had always, unquestionably, meant in-person. As Laura Bassanger put it “Prior to Covid this [online delivery] never existed in our minds, because it was face-to-face and that’s it” (Starlight). Yet, within days or weeks of lockdown, the majority were offering some form of digital provision.

Given this context, the rapidity of the shift to online provision that did occur is fairly remarkable. Several organisations discussed how, perceiving what was on the horizon, they dedicated the last weeks before the first lockdown in March 2020 to digital training. This is captured in remarks by Hannah Facey “We went onto Skype three weeks before anything was announced here. Our last session was a practice so that everyone could understand how to connect to Skype. We were all in the same room, doing this Skype” (Act Up!) The majority of the practitioners interviewed set up some form of regular online support or contact with their members within days or weeks of the imposition of the first lockdown restrictions: “We quickly moved online, which is something we’ve never done before […] I think maybe we had a week break, and then move into Zoom sessions”. (Proud and Loud Arts)

Similar findings are reported elsewhere, such as a survey of support for people with learning disabilities during Covid-19, where Jane Seale notes that the majority of self-advocacy groups and charities were using online technologies within days or weeks, while local authority was slower in both making decisions and implementation (Citation2020, p. 22). Seale describes the online adaptation within learning disability support as “speedy, evolving, creative and fearless” (Citation2020, p. 3). Quantitative data from McCausland et al describes a significant increase in technology use during the pandemic by learning disabled adults in Ireland (Citation2021). Meanwhile, in a review of 47 case studies of arts and health provision during Covid-19, the Culture, Health and Wellbeing Alliance (CHWA) also describe a movement of swift and committed engagement with online delivery, noting:

The most striking aspect of these case studies is the determination and commitment of organisations and freelancers to find ways to support their participants and the staff in the institutions they work with, despite serious restrictions and their own personal challenges. (CHWA, Citation2021, p. 9)

A further recurring theme was to stress that digital access was only part of the endeavour and once within the online space it was necessary to actively work to ensure their practice remained inclusive. Stacey Sampson commented:

It’s just thinking about what activities might still engage people, because it’s not enough for us to think of an activity that’s going to engage two or three people, and everyone else can just watch. We’re obviously constantly thinking about what’s the most accessible and inclusive way to use it. (Under the Stars)

So how best to bridge the digital divide in the UK? Simply giving people the right equipment or access to it is not enough, says Allmann. ‘The solutions have to involve human intervention, commitment, and care.’ What is needed, she adds, are ‘intensive, long-term support networks to help people acquire the digital know-how they lack … People helping people.’ (Citation2020, p. 395)

This last point is vital in the context of learning disabilities, where central to any attempt to narrow the digital divide is the role of “supporters” in facilitating or hindering access.

Participating from home, supporters and digital access

In-person, community arts takes place outside the home. In contrast, online activities involve participating from home or from a care / supported living environment. This produced shifts in the three-way relationship between arts organisation, learning disabled participants, and supporters or support networks.

In research conducted into the online engagement of learning disabled adults during Covid-19, Seale writes that “One of the most significant factors that enables people with learning disabilities to use and benefit from technologies during lockdown is support from someone living with them” (Citation2020, p. 3). Factors here include whether supporters (which includes family, parents, carers and other professionals) themselves have the skills, time, motivation and interest to facilitate access and support digital engagement. The lack of support, or the unwillingness to provide digital support, can result in learning disabled people being excluded from digital spaces. Rouse similarly notes one barrier to digital engagement as being “resistance from support/family” (Citation2020, p. 11). This factor pre-dates Covid, and in a 2014 report Seale draws together data on the technology use by learning disabled adults to present the hypothesis that “a significant proportion of parents whose children have learning disabilities are prejudiced about their ability to use the Internet, apprehensive about their children causing equipment breakdown and fear them being affected by harmful Internet content” (Citation2014).

The organisations interviewed for this paper indicated varying levels of engagement from their members in the alternative online activities that they offered during Covid-19. In some circumstances, organisations were able to draw on well-established support networks and reach close to 100% participation:

We’ve been lucky with support network, parents and carers. they're kind of part of the group and they're in with us. And they're there, they stay usually for the session and get involved. (Cross the Sky)

We’ve got really good relationships with all of the support networks and their families, so we could get them online. (Proud and Loud Arts)

A lot of people that were living in carer assisted accommodation, and things like that, meant that they had less frequent support in terms of people's availability to help them get on technology. We were relying on carers and staff. And obviously, they were being pulled in all different directions. (Under the Stars)

Several of the organisations stressed that it was important to note that carers, parents and family members often lacked the skills to offer support or were themselves elderly, vulnerable or simply being pulled in multiple directions by the challenging circumstances of the Covid-19 pandemic. In these circumstances, there was an understandable unwillingly to judge or be too critical in limitations of support.

However, at times the resistance was connected to other factors, including assumptions that digital delivery just wouldn’t work. Jenna Howlett commented that “It was almost like before you even began there was an assumption that it might not work. Rather than let’s just give it a go […] their carers or parents had decided actually, they're probably not going to engage” (Fuse). Others reported similar feelings:

There was a lot of support staff or families going, oh they won’t interact with Zoom. They won’t, you know, relate to a screen or anything. So we have had a lot of resistance. (Accessible Arts and Media)

The feedback I was getting from parents and carers was that they just wouldn’t engage with it. That's what parents and carers were saying to me, they’re just not interested. It just felt like sometimes it was almost a hinderance to them that they have to, you know, set a laptop or a tablet and sit with them. (Starlight)

What was lovely was seeing the parents, because we obviously we don't usually see them. We’ve got to know them quite a lot more during Covid. Seeing them interact on something that's not their day-to-day activity, that something very, very different for them. (Into the Sky)

The shift to “from home” engagement in the community arts raises other questions that we are only just beginning to untangle. Online delivery involves entering a participants’ residential space, even if only virtually, and therefore prompts questions of privacy, responsibility for safeguarding, independence and support. For a community arts organisation the boundaries of engagement and responsibility become increasingly blurred and potentially extended in ways that would be difficult to sustain. The rapidity of the shift to digital practice has meant the thinking in some of these areas has lagged behind the doing. The digital turn certainly creates challenges to the inclusive ethos of community arts, but it is also clear that social inclusion and cultural democracy today must also include the right to access and participate in online spaces and activities. Ensuring this in learning disability practice requires participants, practitioners and supporters working together to develop new forms of inclusive capital. Some of the implications for this in terms of policy and practice will be returned to in the conclusion.

Opportunities and enhancement: the gains of digital inclusion

This paper has explored how engagement with online community arts began from a low starting point and faced significant obstacles of digital exclusion and lack of support. However, one unintended consequence of Covid-19 was the investment of time and creativity in addressing these challenges, with the result being the development – for both practitioners and participants – of new forms of digital inclusive capital. Part of this took the form of actively identifying positive gains of online provision and leaning into these – that is, working with the technology and the affordances it enabled. With that attitude, what opportunities, positive differences and enhancements might be attainable? Through the CDB project, four areas emerged where practitioners identified positive gains and opportunities from online delivery: new skills, broadening horizons, inclusivity gains, and impacts on creativity ().

New skills

As discussed above, for the vast majority of community arts companies, the shift to online provision occurred from a very low initial base and required a rapid engagement with new skills and new technologies – for both practitioners and members. This acquiring of new skills is a positive outcome in its own right, with the potential to increase the independence and confidence for people with learning disabilities (Rouse et al., Citation2020, p. 10). This impact was observed in several interviews, including:

Well the skillset, to get our guys confident with Zoom, has been extraordinary, extraordinary. They have really, really taken it on board. (About Face)

They are now joining other things on Zoom. And it would have been harder for them to join those things, if they hadn't had this initial support and understood how to work it. (Act Up!)

Broadening horizons

In some ways the rapid engagement with digital and online provision represented a catching up, engaging with technologies and possibilities that have largely been around for several years. As Claire Reda observed:

We've always wanted to do it, but it's always been, we'll do that later. But actually, this was opportunity, why not do it now? (Indepen-dance)

The Creative Doodle Book itself was an example of a project that would not have been possible offline, at least not without considerably greater resources, given the scale and geographical spread of delivery. Several groups took the book in different directions: Independance ordered 250 additional copies to distribute to all their members; Act Up! produced a film about their involvement; Square Pegs used the Doodle Book as the basis for mediated conversations between their members of external artistic mentors:

Zoom enabled us to forge relationships with artists and our company that we might not have been able to otherwise. We’ve been able to bring in artists in a unique way. (Square Pegs)

Access and inclusivity gains

While it is worth remembering the access challenges of online practice, there have been some significant inclusivity gains as a result of the shift to digital provision. This has been broadly noted in terms of the streaming professional performances, which had made work more accessible to disabled people in their own homes (Secmezsory-Urquhart, Citation2021). Within community arts, online delivery similarly lowers barriers to attending. There were occasions, for example, when CDB participants stated that they hadn’t been feeling too well on a particular day, suffering from mental or physical fatigue. If they had needed to travel to the workshop they would not have left the house and would have missed out entirely. In other words, the barriers to participating online are lower, and for learning disabled participants that also removes barriers in terms of independent travel and costs. While all the organisations were looking forward to getting back to in-person delivery, several had started to think about how these access gains might be retained:

If capacity wasn’t an issue would love to carry on with online. Just because I know that some of our participants wouldn’t get to the face to face sessions. (Accessible Arts and Media)

the different skills that zoom requires in how you orchestrate conversation and include people. In some ways it sort of simplifies inclusive practice. Techniques for turn taking make sure people are included. (The Lawnmowers)

While Jenna Howlett commented:

From experience now we can see that sometimes it is actually a lot easier for [non verbal participants] to be watching and taking everything in and then being able to communicate how they want to communicate. (Fuse)

Impacts on creativity

Directly emerging from this equity of the digital space have been the experience that online engagement also encourages and facilitates greater creative autonomy. While everyone interviewed missed the sense of togetherness that is possible when working in the same physical space, nobody would argue that in-person group dynamics are without difficulties – not least concerning group think or peer influence. For Jo Frater one advantage of working with the Creative Doodle Book online was that:

Everyone’s got their own space, no one’s comparing themselves to anyone else. They’re able to have their privacy and their art time and creativity in a really private way. And then they get to share it in this really nice, communal way. And it really fits with the technological advancement of Zoom. (Confidance)

Conclusions: thoughts to the future

As we begin to consider a post-pandemic world, thoughts also turn to what might be retained from our Covid-19 adaptations – not least in terms of what elements of the digital turn might persist in a manner that supports the development of inclusive capital and therefore avoids exacerbating the digital divide. As Seale writes:

The experience of using technology to support people with learning disabilities during the pandemic has led many supporters to conclude that it would be beneficial to continue these practices beyond the pandemic and indeed to develop them further. (Citation2020, p. 3)

The Creative Doodle Book project sought to model inclusive online community arts and through working with a network of practitioners and learning disability arts organisations across the country both reflect upon and learn from this practice. The insights from this project show that it is possible to construct high-quality virtual spaces and practices where learning disabled people’s participation is seen as the fundamental starting point, an accepted normality within our human community. The result is inclusive online spaces that are true to the ethos of community arts and cultural democracy in which everybody belongs. As we return to physical spaces, it is vital that these insights and practices are maintained. Once physical and technological access needs are accounted for, online spaces can be inclusive and can provide engaging, creative and vital resources for people with learning disabilities. It is also clear that participation in online spaces is and must be just as much a right as access to and inclusion within all and any other cultural or social space. Indeed, considering social inclusion without that also embracing online inclusion is increasingly impossible.

These are therefore the key policy insights from the Creative Doodle Book project, which identified clear pathways through which learning disabled people – and their support networks – can develop inclusive capital that actively combats the digital divide. Drawing from both the insights from the CDB, and the literature around inclusive online practice, it is possible to assert the following policy recommendations:

There is a current lack of inclusive and accessible online community spaces for learning disabled people. Online engagement is further limited by the lack of skills and knowledge of support workers, families and other carers.

Experiences during Covid-19 demonstrate the value of these services and their potential for ongoing wellbeing support.

With appropriate support, in the form of investment, technological infrastructure and skills training, there is strong potentially for the community arts to fill this gap.

Learning disability support, in whatever context, must now also incorporate technological and digital support. Inclusion within online spaces must be supported and enabled as a fundamental aspect of social inclusion and cultural democracy. The returns on this are significant, with greater technological skills, confidence and online networking creating spaces for learning disabled people to voice their perspectives, express themselves creatively and gain a sense of belonging through engaging with others on an inclusive and equal basis.

Ethical approval

The research for this project received ethical approval from the School of Arts Ethics Committee, York St John University. Ref. 2184. November 2020. All interviewees quoted within this paper gave consent for themselves, and their organisations, to be named as part of the research. Consent was audio recorded as part of the online interviews.

Acknowledgements

The Creative Doodle Book was developed in collaboration with artists from Mind the Gap and designed in partnership with Brian Hartley. The project team included Vicky Ackroyd, Lisa Debney, Deborah Dickinson and Brian Hartley and was delivered in partnership with Mind the Gap and Totally Inclusive People. The project drew upon the goodwill and dedication of all the participating organisations, their practitioners and members.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Matthew Reason

Matthew Reason is Professor of Theatre and Director of the Institute for Social Justice at York St John University, UK. His current focus is on experiential and phenomenological responses to theatre and dance performance, including through qualitative and participatory audience research. His books include Documentation, Disappearance and the Representation of Live Performance (2006), The Young Audience (2010), Kinesthetic Empathy in Creative and Cultural Contexts (with Dee Reynolds 2012), Experiencing Liveness (with Anja Lindelof 2016), Applied Practice: Evidence and Impact across Theatre, Music and Dance (with Nick Rowe 1917) and the Routledge Handbook of Audiences and the Performing Arts (with Conner, Johanson and Walmsley 2022). For further information visit www.matthewreason.com.

References

- Bishop, C. (2012). Artificial Hells: Participatory Arts and the Politics of Spectatorship. Verso.

- Bogner, A., Littig, B., & Menz, W. (2009). Interviewing Experts. Springer.

- Burgstahler, S. (2015). Opening doors or slamming them shut? Online learning practices and students with disabilities. Social Inclusion, 3(6), 69–79. https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v3i6.420

- Calvert, D. (2015). Mind the gap. In L. Tomlin (Ed.), British Theatre Companies: 1995-2014 (pp. 127–154). Bloomsbury.

- Camerson, J. (1992). The Artist’s Way: A Spiritual Path to Higher Creativity. Jeremy P Tarcher.

- Camlin, D. A., & Lisboa, T. (2021). The digital ‘turn’ in music education (editorial). Music Education Research, 23(2), 129–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2021.1908792

- Chennat, S. (2019). Conceptualizing disability inclusion. In Chennat (Ed.), Disability Inclusion and Inclusive Education (pp. 39–62). Springer.

- CHWA (Culture, Health & Wellbeing Alliance). (2021). How Culture and Creativity Have Been Supporting People in Health, Care and Other Institutions During the Covid-19 Pandemic. Report. https://www.culturehealthandwellbeing.org.uk/how-creativity-and-culture-are-supporting-people-institutions-during-covid-19

- Clark, J. L. (2021). Against Access. McSweeney’s 64: The Audio Issue. https://audio.mcsweeneys.net/transcripts/against_access.html

- Fletcher-Watson, B., & May, S. (2018). Enhancing relaxed performance: Evaluating the autism arts festival. Research in Drama Education: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance, 23(3), 406–420. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569783.2018.1468243

- Hadley, B. (2022). A “Universal design” for audiences with disabilities?. In M. Reason, L Conner, K Johanson, & B Walmsley (Eds.), The Routledge Companion to Audiences and the Performing Arts (pp. 177–181). Routledge.

- Halder, Santoshi, & Argyropouplos, Vassillos. (2019). Inclusion, Equity and Access for Individuals with Disabilities: Insights from Educators across the World. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Hall, E. (2010). Spaces of social inclusion and belonging for people with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 54(1), 48–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2009.01237.x

- Hargrave, M. (2015). Theatres of Learning Disability: Good, Bad, or Plain Ugly. Palgrave.

- Hayhoe, S. (2018). Inclusive capital, human value and cultural access. In B. Hadley & D McDonald (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Disability Arts, Culture and Media (pp. 125–136). Routledge.

- Hepplewhite, K. (2020). The Applied Theatre Artist: Responsivity and Expertise in Practice. Springer.

- Kelly, O. (1984). Community, Art and the State: Storming the Citadels. Commedia.

- McCausland, D., Luus, R., McCallion, P., Murphy, E., & McCarron, M. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on the social inclusion of older adults with an intellectual disability during the first wave of the pandemic in Ireland. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 65(10), 879–889. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12862

- Price, S., Phillips, J., Tallent, J., & Clift, S. (2021). Singing group leaders’ experiences of online singing sessions during the COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid survey.

- Rouse, L., Tilley, E., Walmsley, J., & Picken, S. (2020). Filling the Gaps: The Role of Self-advocacy Groups in Supporting the Health and Wellbeing of People with Learning Disabilities Throughout the Pandemic. The Open University.

- Schon, D. (1983). The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. Basic Books.

- Seale, J. (2014). The role of supporters in facilitating the use of technologies by adolescents and adults with learning disabilities: A place for positive risk-taking? European Journal of Special Needs Education, 29(2), 220–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2014.906980

- Seale, J. (2020). Keeping Connected and Staying Well: The Role of Technology in Supporting People with Learning Disabilities During the Coronavirus Pandemic. The Open University.

- Secmezsory-Urquhart, J. (2021, July 14). The future of access: Disability and the arts. The Skinny. https://www.theskinny.co.uk/theatre/interviews/the-future-of-access

- Smith, K. (2013). Wreck This Journal: To Create is to Destroy. Penguin.

- Waterfield, J., & West, B. (2006). Inclusive Assessment in Higher Education: A Resource for Change. University of Plymouth. www.plymouth.ac.uk/uploads/production/document/path/3/3026/Space_toolkit.pdf

- Watkin, J. (2021, November 3). @fekkledfudge. ‘When you’re blind and you’re in a meeting with Dead folks’. Twitter. twitter.com/fekkledfudge/status/1455918190366806022

- Watts, G. (2020). COVID-19 and the digital divide in the UK. The Lancet Digital Health, 2(8), e395–e396. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2589-7500(20)30169-2