Abstract

Ann Quin’s innovative, versatile oeuvre made a substantial contribution to 1960s and 1970s British avant-garde and experimental writing, but literary scholarship has, until recently, been slow to appreciate the brilliance and importance of her work. This special issue of Women: a cultural review is the first collection of its kind focused solely on Quin. To frame the collection, I offer a short introduction to Quin’s work and life, and discuss how her working-class identity has been considered a significant factor in relation to the distinctive forms, language, aesthetics and experimentation of her writing. I introduce the volume’s contributions, which include an interview, a creative-critical piece, and four critical essays on Quin, to show the correspondences, overlaps and contrasts between them. In particular, I focus on their consideration of archive materials, and the aesthetic and sensory qualities of Quin’s writing. I argue that, precisely by being read together, the contributions deepen and extend our thinking about Quin, give a sense of current critical approaches to her work, and provide a key opportunity to reflect on the significance of our impulse to return to her work today.

Keywords:

Disliking Stein, I detour instead towards Ann Quin. Feeling Beckett is too obvious a point of reference, I detour instead towards Ann Quin. Despite ongoing rumours of a B. S. Johnson revival, I feel our attention could be more usefully directed towards Ann Quin. (Home Citation2003: 169)

The volume’s contributions include an interview, a creative-critical piece, and four critical essays on Quin, many of which are written by emerging scholars who are at the forefront of efforts to recover her work. Its scope is a testament to the current strength of the field of scholars working on Quin, her era, and her fellow experimental writers. Recent academic work in this area includes: British Avant-Garde Fiction of the 1960s (Mitchell and Williams 2019); The nouveau roman and Writing in Britain After Modernism (Guy 2019); The Post-War Experimental Novel: British and French Fiction, 1945–75 (Hodgson 2020); Late Modernism and the Avant-Garde British Novel: Oblique Strategies (Jordan Citation2020); Vagabond Fictions: Gender and Experiment in British Women’s Writing, 1945–1970 (Sweeney Citation2020); The Experimentalists: The Life and Times of the British Experimental Writers of the 1960s (Darlington 2021); ‘Slipping through the Labels’: British Experimental Women’s Fiction, 1945–1975 (Radford and Van Hove 2021). In terms of works focussing solely on Quin, so far we have Ann Quin’s Night-Time Ink, A Postscript (Butler Citation2013) and Re; Quin (Buckeye 2013); forthcoming are Jennifer Hodgson’s much anticipated biography, and my own critical monograph Ann Quin: Gender, Experiment, Precarity (2022).

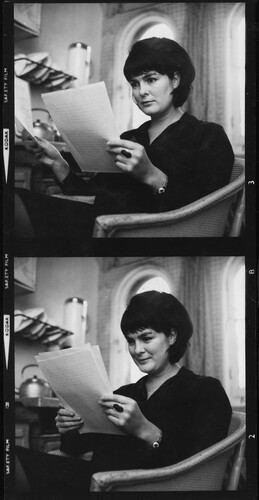

Figure 1. Ann Quin, photograph by Oswald Jones, from the Larry Goodell Collection, courtesy of Larry Goodell.

This collection makes a distinctive contribution to such recuperative work via its range and variety of perspectives on, and forms of response to, Quin. Collected and read together, the pieces included here articulate a vibrant and lively debate about how we (can? should? want to?) read Quin, and how and why her writing is being returned to now. The contributions offer discussion and readings of many of Quin’s major texts, and situate her work in dialogue with archive material, literary and critical contemporaries, the visual arts, and the technological, social, historical, cultural and intellectual contexts of her times. Taken as a whole, the collection shows where the interests of current scholarship lie and opens up new possibilities for reading and responding to Quin’s work. This is demonstrated not because this special issue on Quin aims for ‘coverage’, but because it presents together contributions whose focus and preoccupations overlap and crystallize to offer complex and layered discussions of certain texts, Three and Passages in particular. This depth as opposed to breadth model means that, inevitably, there are gaps—indeed, the ongoing pandemic situation led to contributors unfortunately having to pull out of the project and as a result, this volume does not include more than passing discussion of Quin’s first novel, Berg (1964). For a still insightful reading of that book readers can consult ‘Voices in the Head: Style and Consciousness in the Fiction of Ann Quin’ (Stevick Citation1989), published in Friedman and Fuchs’s seminal work Breaking the Sequence: Women’s Experimental Fiction, as well as the discussions of Berg in the list of texts above and in several of the pieces on Quin’s work in Music and Literature No. 7 (2016).

Quin wrote four novelsFootnote2—Berg, Three (1966), Passages (1969), Tripticks (1972)—as well as a diverse range of shorter pieces including stories, memoir, poetry, radio and television plays. Berg, a deeply strange and darkly comic seaside noir, follows Alistair Berg, posing as a man named Greb, in his failed attempts to murder his father, and was hailed by reviewers as ‘[m]urkily original and menacing’, ‘promis[ing] a talent likely to develop in strength’; the nouvelle vague influenced Three is a fragmented and overlapping collage of diary and narrative forms that centre on the bourgeois married couple Ruth and Leonard’s claustrophobic relationship and their obsessions over an absent third character, S, who has drowned at sea; Passages, a split form text which fluctuates between an impressionistic stream of consciousness style and more static columns of an annotated journal, is another search story, of a woman and her lover across a Mediterranean landscape as they look for her lost brother; Tripticks, whose narrator is on the road on a surreal and frenetic trip across America, is Quin’s most daringly experimental work, a punky, rhythmic and parodic free-form text intercut with cut-up pop art illustrations by Carol Annand.

Quin’s ‘stories and fragments’, written across the 1960s and early 1970s, were recently collected by Jennifer Hodgson and published together for the first time in 2018 by the independent press And Other Stories in The Unmapped Country: Stories and Fragments. This text has played a key role in the resurgence of interest in Quin. The pieces included there range from the memoir-style ‘Leaving School’ and ‘One Day in the Life of a Writer’, to the dark and vividly nightmarish ‘Nude and Seascape’ and monologue ‘Ghostworm’; some stories, such as ‘Never Trust A Man Who Bathes with His Fingernails’ and ‘Eyes that Watch Behind the Wind’, are set in vivid New Mexico landscapes and some—the grotty interiors and drab seaside location of ‘A Double Room’ and the one-sided phone call of ‘Motherlogue’—in domestic and semi-domestic spaces in England; there are also the first two chapters of Quin’s unfinished novel The Unmapped Country, an exploration of madness and critique of institutionalization. Together, these shorter works showcase the intensity and defamiliarizing effects of Quin’s work as a whole, as well as revealing its patterns and preoccupations—the sea, violence, myth, thwarted desire, psychology and psychosis. Across the oeuvre as a whole, pronouns and perspectives shift, strange fantasy and mundane reality merge and overlap, narrative and story are interrupted and refused. Quin’s prose is complex, off-beat, innovative and versatile, at once deeply personal and wildly experimental. As the responses in the present collection attest, the range and risk of her writing still stirs and startles the reader today.

Such a response is articulated in Leigh Wilson’s interview with Claire-Louise Bennett in this volume, a conversation which explores how and why Bennett is engaged with Quin’s work. Bennett’s latest novel, Checkout 19, shortlisted for the 2021 Goldsmiths’ prize, directly engages with and thinks about Quin, and the interview reveals some of the key reasons for this. Bennett describes Quin’s writing as sexual, irreverent and productively contradictory: ‘so thrilling and so alive and so much its own thing’ (pp. 18, 19).Footnote3 Her prose is exciting, free and freeing because of the possibilities it opens up in terms of what areas of life and what kinds of experiences can be written about and in what ways: for Bennett, Quin’s work speaks to aesthetic, phenomenological, and existential concerns that continue to challenge writers and readers in the twenty-first century. Liberated from the conventions of plot and characterization, instead in her prose people and objects move in and out of focus and, for Bennett, this creates particular material effects: ‘the status that things have been accorded are lifted away, and things are loosened and free again, they have autonomy again’ (p. 25). As a whole, the interview makes the case that Quin’s texts make for ‘exhilarating’ (p. 30) reading, and Bennett celebrates the feeling of being immersed and lost in her prose—‘no one’s going to get it completely on the first go, so it’s fine. Her sense-making is just completely different’ (p. 30).

Part of the reason for this different ‘sense-making’, according to Bennett, is Quin’s working-class background, which brings with it a unique relationship to language. Bennett speculates that this class status also provoked the snobbery behind some of the dismissal of her experimentalism: ‘They couldn’t give her any credit because, from their class position, they couldn’t entertain the idea that actually this could be an authentic response to life from a working-class female perspective’ (p. 24). In her experimentalism, Quin was consciously writing against the modes seen as acceptable for working-class writers, associated with the so-called ‘return’ to realism, including ‘kitchen sink’ realism and the angry young men. In this context, Quin’s particular position as a female working-class experimental writer challenged expectations and this perhaps offers some explanation of her previous neglect. As Sweeney reminds us in Vagabond Fictions, Christine Brooke-Rose pointed out the triple difficulty she herself faced: that of being a woman, a woman writer, and an experimental writer at that (Citation2020: 2–3); in Quin’s case there is the fourth difficulty of being working-class. Recent recuperative work has engaged with this, and Quin’s working-class status has been foregrounded, claimed and celebrated as a key contributing factor to her writing’s distinctive uses of language and experimental forms. For example, Quin’s contemporary Giles Gordon claimed: ‘Here was a working-class voice from England quite unlike any other’ (Citation2001: ix). Hodgson opens her introduction to The Unmapped Country: Stories and Fragments with: ‘Ann Quin was a rare breed in British writing: radically experimental, working-class and a woman’ (Citation2018: 7), and in her introduction to the reissue of Passages, Bennett observes ‘growing up in a working-class environment may well engender an aesthetic sensibility that quite naturally produces work that is idiosyncratic, polyvocal, and apparently experimental’ (Citation2021: v). In this way, Quin’s working-class position has been claimed by several of her recent readers as a substantive and necessary part of our reading and (re)appraisal of her work, particularly in terms of how this might be bound up with the distinctive qualities and effects of her engagement with and reimagining and recreation of, modernist and avant-garde styles and forms. The quadruple challenges Quin faced as a female, working-class, experimental writer are thus perhaps precisely what gives the writing its inimitable tang and spirit. At the same time, however, and as noted in the brief biographical sketch below, it is worth being circumspect about positioning Quin as working-class, the relevance of which vis a vis her life and writing is complex, uncertain and mobile. In relation to this, Wilson and Bennett rightly acknowledge the challenges presented to class identity by middle-class orientated education, challenges Quin experienced in terms of an ambivalent relationship with formal education, and which she articulated in pieces such as ‘Leaving School—XI’ and ‘Second Chance’, a late article for The Guardian in August 1973.

Life

Indeed, Quin’s biography both confirms and perhaps complicates the question of her working-class identity. Ann Marie Quin was the only child born to her unmarried Irish father and Scottish mother—on March 17th, 1936 in Brighton. Her father—Montague Nicholas Quin—left when she was young, and Quin remained with her mother, Anne Reid. After Montague Quin left, mother and daughter were turned out of a house populated by paternal aunts and cousins and left destitute, leaving Anne to try and make ends meet. Quin was then sent to school at the Holy Trinity Convent in Brighton to, as she puts it in ‘Leaving School’, be brought up ‘a lady’: ‘To say say gate and not giate—the Sussex accent I had picked up from the village school in my belly-rubbing days had to be eliminated by How Now Brown Cow, if I wanted to make my way in the world. According to mother’ (Citation2018: 15). When she left at seventeen, Quin threw away the school uniform, exchanging it for one of make-up, high heels and nylons. Working as an assistant stage manager, she dreamed of becoming an actor but instead spent time gathering props, scrubbing the stage, sewing, making tea and attempting to be knowing, laughing at ‘camp jokes I didn’t understand’ (18). However, when opportunity came her way an attack of nerves sabotaged her RADA audition, and after winning a poetry prize, she vowed instead: ‘I would be a writer. A Poet’ (19).

This desire to write was in tension with pressing material need, so Quin took a secretarial course and worked for a while at a newspaper office in London. For the next few years, she worked in various secretarial jobs with the hope of writing in her ‘spare’ time, of which there was very little between the long hours working and commuting. As became the pattern throughout her life, optimistic periods of long days working for money and writing in the evenings were interrupted by collapse, illness (physical and mental), and periods of recuperation at her mother’s in Lewes Crescent, Brighton. After a nightmarish summer job in a hotel in Cornwall, which triggered a period of acute breakdown and extended recovery, Quin moved from Brighton to London to escape the ‘hell’ of commuting. 1959 found her living in Soho, fascinated by watching prostitutes from her window. She survived on a pittance working as a part-time secretary for a law firm, but dreamed of buying books and clothes, a nice place to live in ‘If I had more money’ ‘I’d like a tower, facing the sea. I’m never so happy as when by the sea’ (Gordon Citation2001: xii). Instead, she got a secretarial job in the painting department of the Royal College of Art and moved to Lansdowne Road in Notting Hill to ‘an attic kind of place, a small skylight, gas ring; partition next to my bed shook at night from the manoeuvrings, snores of my anonymous neighbour’ (Quin Citation2018: 23).

Quin’s first two attempts at novels—A Slice of Moon: ‘about a homosexual, though at the time I had never met one, knew very little about queers (maybe I had read something on Proust?)’ (20) and a ‘book about a man called Oscar, who kills his monster child—a novel that developed into telephone directory length of very weird content, without dialogue’ (23)—failed to find publishers. The finished manuscript of her third attempt (much of which was banged out on Quin’s typewriter while working at Carol and Alan Burns’ flat), Berg, satisfied John Calder’s reader, Dulan Barber. Barber remembers the then 27-year-old as pale, with a pretty face and long ‘gorgeous’ legs (as well as a ‘round-shouldered defensive hunch’) (Citation1977: 176). As to the novel: ‘I thought it was marvellous, extraordinarily well-written and haunting’ (169). Unsurprisingly, Quin found the focus on her gender and appearance annoying: ‘I find difficulty in being a writer and a woman where lots of men are very unsure of me and they are liable to sort of put me down and treat me from a physical angle which gets me very frustrated’ (Dunn Citation2018: 193). Indeed, much of Quin’s conversation with Nell Dunn in Talking to Women articulates her frustrations with gender norms in terms of being a writer, as well as with expectations around sexuality and domesticity. In life, Quin’s sexual and platonic relationships were often volatile, her love affairs intense, unconventional, open and experimental. In her novels and stories, the writing of voyeurism and sexual violence seems to invite complicity and express an uncomfortable, complex and ambivalent attitude towards gender and sexuality. Sweeney’s Vagabond Fictions reminds us that, while Quin’s writing clearly interrogates sexist institutions such as marriage and the home, she is also writing both in the age of ‘free love’ and before feminism becomes an organized movement from 1970 onwards.Footnote4 Unfortunately, despite her abhorrence and avoidance of female domestic roles, Quin’s material and financial circumstances often trapped her in low-paid, and rather gendered, secretarial jobs. Desperate to put an end to this time-consuming, tiring, tedious work, Quin was impatient and sent letters requesting a contract for Berg. From the start, her correspondence with her publishers is demanding and desperate in tone, expressing a deep anxiety about money.Footnote5

Berg, and its publication by the innovative and exciting partnership of John Calder and Marion Boyars, put Quin’s writing alongside, and in many cases brought her into contact with, other ‘experimental’ writers of the time, such as Natalie Sarraute, Alain Robbe-Grillet, Alexander Trocchi, Samuel Beckett, William Burroughs, Robert Creeley and more. Berg also won Quin the D.H. Lawrence Scholarship from the University of New Mexico and the Harkness fellowship for 1964–1967, which enabled her to travel, live and work in the U.S and New Mexico for several years in the mid to late 1960s. Between 1962 and 1965, whenever Arts Council Grants or finances allowed, Quin also travelled to Paris, Italy, Greece, Amsterdam, Ireland and Scotland. During this peripatetic and liberating time in the mid-sixties, she wrote Three, Passages, and many of her shorter pieces. Once back in England from 1969, and at the end of a particularly painful love affair, Quin wrote a response to her time in America with Tripticks. After the freedom of travelling and being funded by grants, she once again found herself struggling with finances and low paid work while trying to write, and her mental health took a sharp decline, resulting in serious breakdowns and periods of ECT treatment and hospitalization in Sweden and London. There was a brief reprieve, when Quin attended Hillcroft residential college for women as part of a return to formal education, with a view to beginning the University of East Anglia’s BA creative writing course in September 1973. About a month before she was due to go, however, at the age of 37, Quin was found drowned off the coast at Shoreham on Sea, her death recorded by the coroner as a ‘tragic accident’.

Wilson’s interview with Bennett ends by considering Quin’s death: for Bennett, the uncertainty of Quin’s death is important. She says: ‘we don’t really know what happened. You can get into a funny space when you’re in the sea, and she obviously had this very strong connection to the sea’, ‘you could just swim out too far, and not be able to get back in’ (p. 32). In this way, Bennett not only articulates the excitement and liberating possibilities of Quin’s prose for contemporary writers and readers alike: the conversation also meditates on important aspects of Quin’s life in terms of her financially precarious and working-class position, for example, as well as the uncertainty surrounding her death.

Archives

We must of course, however, read between Quin’s writing and life with caution, and the essays in this collection remind us to think carefully about the purposes and uses of Quin’s archive materials in relation to our recuperative critical work. These archives are scattered, located in the institutional archive collections of her lovers Robert Creeley and Robert Sward, for example, as well as in the Calder and Boyars papers, and in private collections of friends and family, Brocard Sewell and Carol Burns included. Many of her manuscripts and correspondence were destroyed in the early 1970s after being covered in cat shit in strange circumstances. As Chris Clarke points out in his reading of archive materials in ‘‘S’ and ‘M’: The Last and Lost Letters Between Ann Quin and Robert Creeley’, there is a strange echo of this when Quin refers to the manuscripts of Three lying about her floor as ‘cat’s doings’ (p. 42).

Several pieces take as their departure points, and even methodologies, the act of writing on Quin through her archives. For example, both Adam Guy’s ‘Ann Quin on Tape: Three’s Auralities’ and Hannah Van Hove’s ‘‘The moving towards words & then from them’: Circling Quin, Circling Passages’ end with reflections on a recording of Quin reading from Three.Footnote6 This recording is particularly symbolic and revealing of some of the key preoccupations of the essays in this volume, and indeed of the wider field of scholarly and creative work on Quin. Goodell’s reel to reel tape recording enables an almost tangible ‘encounter’ with the writer. For the Quin scholar or the writer engaged with her work, the disembodied voice creates the frisson of a ghostly encounter with the subject of one’s desire.Footnote7 Quin’s reading is measured and rhythmic, its sound patterns complement the strange flattening effect that is also achieved in the content of the writing, as it oscillates between intimacy and distance, stasis and motion, fantasies and the material world. Guy’s engagement with the recording provides a fitting and eloquent ending to his discussion of sound in Three, while for Van Hove, the recording offers cognitive dissonance: ‘her voice is so unlike what I imagined, and yet not’; ‘She sounds posher than I would have anticipated’ (p. 111). Here, Van Hove raises questions that are relevant for reflecting on our responses to Quin’s work and life via archive materials. What might we be hoping or looking for when we listen to a recording of Quin? What kinds of desires are at work? (How) does the sound of her RP voice complicate the notion of Quin as ‘working-class’—an aspect of her identity which, as I have discussed, has been important in some of the recent recuperative work?

Goodell’s recording of Quin is just one example from a range of archive materials engaged with across this collection. Van Hove, for example, uses a split form essay to immerse the reader in the affective experience of archival work, and reflects on the experiences of working with Quin’s paper archives in terms of the intimacy/distance dynamics this creates, and the role of scholarly desire. Van Hove’s method, which moves between critical discussions of Quin’s work and life and personal reflections on the experiences of working on her writing and archives, compellingly demonstrates the complexity of this research process—or, as she puts it ‘(re)search’ (p. 96). Here, she admits a wish to get ever closer to Quin, to be able to say ‘this, for example, was what it was like to be writing experimentally as a woman in the sixties’ (p. 96); yet the specificity, the precise subject or object of research, always slips away and refuses to be pinned down. Just what is it, Van Hove asks, that we are looking for?

A similar sense of the elusiveness and limitations of our work with Quin’s archive materials is articulated by Clarke, who quotes from one of Quin’s letters to Creeley in which she refers to a ‘huge trunk’ (p. 36) containing all his letters—yet when Clarke locates the trunk in a private archive collection, it is empty and nothing is found. Across his essay, Clarke’s discussion of archive correspondence and of Quin as a cultural revenant offers a poignant and sensitive reading of the scattering, absence and loss that haunts her published writing, her archive materials and our recuperative work. ‘Consequently', as he puts it, ‘researchers of Quin’s work risk uneasily and indirectly reenacting the drama of Three when they explore what remains of her writing in the archives of her peers or track down her papers in personal collections’ (p. 35). Indeed, as Clarke reminds us, ‘recent attempts to recover Quin from obscurity seem to accentuate rather than to alleviate her ghostly status’ (pp. 33–34). Guy considers the ethical dangers of our broader recuperative work on Quin in similar terms.Footnote8 He articulates caution in relation to such work, which might claim to ‘unearth’ a supposedly forgotten or neglected writer for our own purposes and moment, and reminds us that this relies upon a ‘depth model of literary history, where certain monuments remain above ground, while others must be dug up or lost to posterity’. However, as the above examples suggest, and as Guy reiterates, ‘The greatest irony of Quin’s recuperation on these terms is that her own writing challenges the very preconditions of such acts of recovery’ (p. 74).

Psychology and Aesthetics

As well as considering the elusive nature of the relationship between Quin’s life, archive materials and written work, the essays in this volume engage with critical perspectives and frameworks to offer fresh and insightful readings of her texts. This includes engagement with Laing’s conception of schizophrenia (Van Hove); dreams and the cut-up technique (White); the aesthetics of touch (Hansen) and of sound (Guy).

Interesting parallels, tensions, complements and overlaps arise between the different readings. Via her own split form essay, Van Hove considers the relationship between Laing’s understanding of the split-self and Quin’s uses of a divided/split text form in Passages, to argue that the inner journeys of the male and female character in the book can each be understood in Laingian terms as suffering from ‘ontological insecurity’ (pp. 106, 107). For Van Hove, ‘By giving primacy to the recording of phenomena, rather than being concerned with their explanation or cause, Passages explores how reality appears to the characters and what their phenomenological experiences consist of’ (p. 105). Her argument culminates with the claim that in this novel Quin’s thinking about myth (particularly Dionysus) and schizophrenia can be productively brought together via Laing. This enables us to understand the schizophrenia of Quin’s characters in Passages—a schizophrenia they both explicitly name—‘within a very specific cultural and political understanding of the term’ (p. 110). In this way, Van Hove’s essay thinks about how Quin’s novels might be productively read and contextualized in relation to historically specific psychological ideas of the split or fragmented self.

Hilary White’s ‘Turning her over in the flat of my dreams’: visuality, cut-up and irreality in the work of Ann Quin’ considers the strange sense of stasis and unreality created by Quin’s characterization, to argue that, through this, her writing deliberately and successfully exposes and conveys the ‘unreality of reality’. White’s essay demonstrates this via a consideration of the visual, hallucinatory and dreamlike qualities of Quin’s writing, which, she argues, ‘are tied together, epitomised in her use of the cut-up’ (p. 118). Her focus is the 1968 story ‘Tripticks’, as well as the novels Passages and Tripticks, and her approach considers ‘Quin's interaction with psychoanalytical and countercultural notions of the dream, rather than offering a psychoanalytical reading of Quin’s use of dream’ (p. 115). Here, like Van Hove, White insists on a historically and culturally contextualized approach when reading Quin’s writing as engaged with psychoanalytical ideas—neither does this via specific claims to biography or direct familiarity with Laing or Freud which might result in a reductive reading; instead, both read between Quin’s texts and such ideas in open, complex and contextually sensitive ways. Indeed, White’s essay can be read to extend Van Hove’s consideration of Quin’s split and fragmented characterization via her discussion of the cut-up. White argues that Quin’s use of this method can be distinguished from Burroughs’ in the way that she uses the cut-up to show how reality is already dreamlike, and to show a ‘widespread lack of agency on the parts of the represented, fragmented subjects, the impossibility of meaningful intervention in a system evading any fixed sense of understanding’ (p. 116). In this way, White’s essay considers psychoanalytic understandings of dreams and dreaming via a specific focus on the aesthetic effects of the cut-up as a distinctive compositional literary technique, to claim that the purpose is a mimetic one: ‘Quin uses dreamlike narrative techniques like the cut-up to portray a somewhat dislocated sense of reality’ (p. 129).

Across her oeuvre, Quin’s aesthetics are characterized by lyrical, vivid and intense written expression that often dislocates and destabilizes objects, exterior and interior landscapes, and emotions via a lens of fantasy. At the same time, her writing focuses on the mundane and grimy; it is ‘peculiarly attuned’, as Hodgson reminds us, ‘to what she [Quin] calls the ‘eggy mouthcorners’ of ordinary life’ (Citation2018: 10). Wary of the ‘purview of depth or suspicious hermeneutics’, Guy’s essay on sound in Three aims to return the reader to the aesthetic surface of the text, an approach particularly apposite for Quin’s writing with its aesthetics of accrual and grotesque details such as ‘greasy mackintoshes, milk skin … chintz and clag’ (Hodgson Citation2018: 10). Guy’s surface reading approach and attention to the materiality of sound in terms of the role of tape and the tape recorder in Three, and his consideration of this technology and its affects in the novel, is sensitive to the historical and culturally ambivalent contexts of its development. Given this, Guy claims, it is possible to argue that in Three sound is a mode of knowing bound up with the materiality of tape, as a ‘uniquely errant medium with a distinct materiality’ (p. 75). Thus, ‘Through the figure of tape, Three finds ways of valuing ambience and materiality, while resisting transactional and suspicious forms of knowledge’ (p. 73). In particular, in Guy’s reading of tape in Three, sound is ambient rather than listened to, and a tangible sense of the materiality of this technology is foregrounded at the end by its being reduced to a hum and a tangle of brown tape.

Denise Rose Hansen’s ‘Little Tin Openers: Ann Quin’s Aesthetic of Touch’ also focuses on the materiality and tangibility of Quin’s aesthetics. She considers how Quin’s multiform texts and ‘use of shapes and surfaces aligns with contemporaneous developments in the realm of visual arts’ (p. 55). In particular, Hansen’s essay reads Quin’s work in relation to contemporaneous developments in 1960s visual arts and anxieties about figuration, to claim that ‘The understanding of aesthetic experience as touching and being touched, and Three’s conceptualization of it, is doubly emblematic of 1960s art and culture’ (p. 59). She argues that an understanding of ‘aesthetic experience as “touch and being touched” is fitting for the way Three makes of literature a plane of perception where figures move tenuously in and out of reach’ (p. 53). In this, Hansen’s reading of Quin coincides with Bennett’s description of the presence of Quin’s characters—‘you feel them intensifying and then you feel them dissolving. They thicken and they attenuate’ (p. 25). Hansen reminds us, however, that Quin’s characters look vainly for aesthetic contact and experience, ‘such “touch” is usually withheld, deferred, or even made violent’ (p. 53); ‘Quin’s particular aesthetic of touch is alert to what is there, but equally to what is not, quite, there’ (p. 69).

Read together then—as my discussion above begins to show—the reverberations, overlaps and divergences between the contributions in this volume demonstrate how the elusiveness of Quin’s archive materials both complement and complicate the fragmented uncertainty, psychological preoccupations, and tangible, sensory aesthetics of her published writing. As the contributions point out, the pursuit of and work with this scattered archive creates a particular sense of readerly desire and intrigue when it comes to seeming parallels or echoes between Quin’s life and work. And the role and usefulness of archive materials for our scholarly work is complicated by how the notion of Quin as a ‘person’ has been inevitably partially composed from this scattered collection of papers and manuscripts. The process of recuperating these materials has created a sense of quasi-ownership and perhaps in some cases placed particular (too much?) importance on Quin’s archive and her life experiences when reading her work. This stage in scholarly recovery work is not unusual, especially when it comes to women writers whose work has been neglected—and even more so, those who die in tragic and mysterious circumstances—when the aim is to retrieve and republish, to take seriously and celebrate their work. Yet as Carole Sweeney reminds us in her discussions of Anna Kavan and Ann Quin, initial recovery work on such writers can therefore also fall into the trap of overly focussing on perceived parallels between life and work to produce ‘maladroitly psychopathographical’ and ‘mechanical’ readings which, unwittingly, then add to a problematic critical tendency of reducing a woman writer’s work to her life (Citation2020: 33). The contributions to this special issue on Quin, however, are well aware of the limitations and dangers of such an approach. They are instead cautious and self-conscious about their engagement with Quin’s archive materials, and these are discussed in dialogue with wider cultural contexts in order to extend and enrich readings of her published texts. Clarke’s contribution, for example, shows that Quin was herself cognisant of the elusive and scattered nature of her archive; in turn, this kind of uncollected and fragmentary archive not only becomes a motif in published works such as Three and Passages, but can be thought about further in terms of the context of gender politics and the notion of the ‘woman artist’ in Quin’s era. Clarke also reminds us—and other contributions similarly reveal—how the elusive archive in and of Quin’s life and work has enhanced the sense of search and secrecy bound up with responses to her work. As Alice Butler puts it: ‘Can you keep a secret? Because that’s what she is’ (2013: 4), and the 2014 Brighton Film Festival celebrated Quin as the ‘best-kept secret of British literature’ (p. 34). Butler’s question and answer articulate how, despite recent critical recovery and renaissance, it is not that the secret has been ‘found out’, but that Quin remains—‘that’s what she is’—elusive. In her contribution to this volume, Wilson ponders how and why the experience of reading Quin’s writing remains ‘so attractive’ and suggests ‘it’s like you’re finding out this secret thing when you come across her, it’s like she’s just ours, isn’t it?’ (p. 29). The discussion between Wilson and Bennett expresses the excitement, recognition and relief felt by the reader discovering Quin’s writing. Other contributions to this volume admit a similar attraction to the notion of Quin as a ‘secret’ and are frank about the desire for intimacy that can haunt recuperative scholarly work. Such discussions reveal how useful the idea of Quin as a secret has been for driving the renaissance of her work, and why we might nevertheless, and precisely because of this, want to be circumspect about the extent of its usefulness. In this way, the volume as a whole grapples with, and expresses the complexity of, some of the practical, ethical and scholarly challenges of recovering a writer like Quin.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the editors at Women and our peer reviewer for their careful feedback and support with bringing this issue together. I would especially like to acknowledge Barbara Rosenbaum—for tirelessly answering my questions—and the support and encouragement of the brilliant and much missed Laura Marcus, without whom this volume would never have happened. Thank you to Larry Goodell, Jeremy Ward and Denise Rose Hansen for giving me permission to use the photographs of Quin which help to bring this issue to life. My gratitude, as ever, for the intellectual curiosity and collegiality of the community of scholars interested in Quin, many of whose work I am delighted to include here, but some of whom, because of Covid and other reasons, I was not able to include (this time!). Thank you all.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Shortly after her death, Quin’s friends Carol Burns and Brocard Sewell collected responses to her work with a view to publication. The collection as a whole did not make it into print, although some pieces were published separately, for example those written by Brocard Sewell, Paddy Kitchen and Dulan Barber.

2 Although, as both Denise Rose Hansen and Hannah Van Hove point out in their contributions to this volume, Quin increasingly came to feel that ‘novel’ was not the right term for her work.

3 In the context of this volume as a whole, this triple ‘so’ poignantly resonates with the quotation Chris Clarke includes from Robert Creeley’s tribute to Quin: ‘There will not be another like her—so possessed, so tough, so dearly in the world’ (p. 49).

4 See also: Morley (Citation1999).

5 Examples of such letters can be found in the Calder and Boyars manuscripts held at the Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington, USA.

6 Made available by Larry Goodell here: https://duende.bandcamp.com/track/ann-quin-reading-first-part-of-three-published-in-1966.

7 As Guy’s contribution reveals, in this desire for a ghostly encounter there are interesting echoes between the protagonists Leonard and Ruth listening to tape recordings in Three, and our listening to Quin.

8 In ‘Ann Quin: “infuriating” experiments?’ (Williams Citation2019) I began to outline other potential dangers for our recuperative work on Quin connected to the ‘celebratory’ mode of the recovery of women writers in particular, which could lead to the exclusion of ambivalent, ‘negative’ or challenging critical responses.

Works Cited

- Barber, Dulan (1977), ‘Afterword’ to Berg, London: Quartet Books Limited, pp. 169–71.

- Bennett, Claire-Louise (2021), Introduction to Passages, Sheffield: And Other Stories, pp. v–ix.

- Butler, Alice (2013), ‘Ann Quin’s Night-Time Ink: A Postscript’, MA dissertation, The Royal College of Art.

- Dunn, Nell (2018), Talking to Women, London: Silver Press.

- Goodell, Larry (2018), ‘Ann Quin Reading – First Part of Three, Published in 1966’, https://duende.bandcamp.com/track/ann-quin-reading-first-part-of-three-published-in-1966 (accessed 2 July 2021).

- Gordon, Giles (2001), Introduction to Berg, Chicago, IL: Dalkey Archive Press, pp. vii–xiv.

- Hodgson, Jennifer (2018), ‘Introduction’ to The Unmapped Country: Stories and Fragments, Sheffield: And Other Stories, pp. 7–12.

- Home, Stewart (2003), 69 Things to Do with a Dead Princess, Edinburgh: Canongate.

- Jordan, Julia (2020), Late Modernism and the Avant-Garde British Novel: Oblique Strategies, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Morley, Lorraine (1999), ‘The Love Affair(s) of Ann Quin’, Hungarian Journal of English and American Studies (HJEAS) 5:2, 127–41.

- Quin, Ann (2018), ‘Leaving School’, in J. Hodgson (ed.), The Unmapped Country: Stories and Fragments, Sheffield: And Other Stories, 15–24.

- Sweeney, Carole (2020), Vagabond Fictions: Gender and Experiment in British Women's Writing, 1945–1975, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Stevick, Philip (1989), ‘Voices in the Head: Style and Consciousness in the Fiction of Ann Quin’, in Ellen G. Friedman and Miriam Fuchs (eds), Breaking the Sequence: Women’s Experimental Fiction, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 231–9.

- Williams, Nonia (2019), ‘Ann Quin: “infuriating” Experiments?’, in Kaye Mitchell and Nonia Williams (eds), British Avant-Garde Fiction of the 1960s, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 143–59.