ABSTRACT

This study explored options for pedagogical photo documentation in early childhood education and care (ECEC) practices to hear the voices of children, parents, and guardians in ways that make developing the documentation manageable for practitioners. Two Japanese kindergartens participated in an action research project entitled ‘Wall Newspapers for Children’. Classroom teachers composed and provided daily pedagogical photo documentation focused on children’s free play and later shared it with the children and their parents or guardians. A total of 194 parents and guardians completed a questionnaire about the documentation’s influence. Narrative episodes of children’s play revealed that the documentation mediated the following dispositions of children’s participation: (1) encouraging children to participate in their new environment and get involved in subsequent play activities for several days, and (2) getting the children to develop and create play activities by themselves. The questionnaire results showed that the documentation enhanced the parents’ and guardians’ communication with their children and with other parents, practitioners, and children in the classroom, encouraging them to talk about their children’s play and learning. The implications of these findings for capturing and improving the quality of ECEC through meaning-making discourse are discussed.

Introduction

Pedagogical scholars and practitioners have long debated the best way to assess child development and outcomes and process quality in early childhood education and care (ECEC). Most agree that the quality of educational practices cannot be adequately measured with only rating scales or checklists based on universal norms, necessitating the use of formative and context-specific assessment approaches. Narrative assessment using pedagogical documentation is one of the most widely accepted ways to monitor children’s development and outcomes (OECD Citation2015). One feature of pedagogical documentation is that it is not focused on measuring children’s acquisition of knowledge or competences (Picchio, Di Giandomenico, and Musatti Citation2014). Pedagogical documentation to describe children’s stories through their daily educational practices is widely known as an essential tool for meaning-making and deciding what is going on in the subsequent pedagogies (Dahlberg, Moss, and Pence Citation2013). Explorations of children’s perspectives and their learning experiences during play activities in ECEC practices could help early years practitioners identify the progression of children’s learning to reflect and improve the quality of their pedagogical process and environment to develop children’s learning dispositions (Carr and Lee Citation2019).

Previous research and educational practices have explored various forms of pedagogical documentation in ECEC, including written notes, photos, multimedia documentation using videos, artefacts produced by children and other materials (Buldu Citation2010; Merewether Citation2018). Practitioners have demonstrated considerably different attitudes, assessments, and modes of adopting and implementing such pedagogical documentation (Knauf Citation2015). One pedagogical documentation approach in ECEC originated with the educational theories and practices of Reggio Emilia, which considered pedagogical documentation a tool for ‘listening’ (Rinaldi Citation2006). In this context, listening to the voices of young children has been regarded as a primary goal of pedagogical documentation (Schiller and Einarsdottir Citation2009). Thus, further studies are needed to explore adapted ways of listening to young children’s voices through documentation in ECEC practices.

Pedagogical documentation: tools for listening to children’s voices

In this study, children’s voices mean the ‘views of children that are actively received and acknowledged as valuable contributions to decision-making affecting the children’s lives’ (Brooks and Murray Citation2018; Murray Citation2019). A fundamental role of pedagogical documentation is to listen to the children’s feelings, preferences, thoughts, or findings, including nonverbal forms of communication such as gestures, facial expressions, drawings, or paintings. These communication forms would not be adequately documented or acknowledged by standardised scales or checklists.

Hearing children’s voices in their play context ‘without any need for contrivance, hijacking, or subverting their intentions’ (Goouch Citation2008) encourages children to be active participants and subjects constructing their learning. That is, listening to children’s voices to help their decision-making about matters that affect their daily lives is linked to children’s participation in ECEC practices (Lancaster and Kirby Citation2014). Pedagogical documentation can help ensure children’s participation during activities in ECEC settings. Pedagogical documentation is inherently connected with child-centred ECEC practices and children’s participation (Rintakorpi and Reunamo Citation2017).

However, we need to know more about what conditions and forms of pedagogical documentation are appropriate for facilitating children’s participation by listening to their voices. In investigating teachers’ approaches to assessment in play-based kindergarten education in Canada, Pyle and DeLuca (Citation2017) noted that the teachers primarily featured academic learning expectations in their documentation and assessment measurements. However, they showed an interest in assessing personal and social learning through play-based learning. The teachers tended to withdraw their students, individually or in small groups, from play periods to guarantee that they were learning the essential academic skills. This raises two issues concerning how we should arrange and embark on using pedagogical documentation as a tool to foster children’s participation in play-based ECEC practices.

The first issue concerns the target audience for the documentation, which could empower children to participate in their play activities. In general, we assume that adults (e.g. parents, guardians, teaching staff, or third parties) are the primary addressees of pedagogical documentation. The sheer volume of printed assessments, reports, and evaluations attests to this adult-centred approach. Knauf (Citation2017) noted that a few centres regarded children as the main audience for the documentation but too often it served as a ‘showcase for the efforts of the ECEC centre, and not so much as a tool to understand the children’ (ibid. 25). If we address the documentation to the children, they can refer to it to arrange their play by themselves. Thus, the children would be involved in recurring documenting processes, which would enhance the children’s learning experiences. Addressing documentation to the children would expand its role beyond being a showcase (Knauf Citation2017).

The second issue of children’s participation raises the role of materiality in documentation (Elfström Pettersson Citation2015). If we value expanding and enriching communication to enhance young children’s participation, we must recognise nonverbal communication forms as essential in hearing children’s voices. A visual form like photo documentation would make activities in ECEC settings more visible for young children and adults than written reports. Walters (Citation2006) found that using digital photos in ECEC settings helped verify children’s learning and created resources that motivated children and encouraged communication. Preparing multiple modalities without texts as pedagogical documentation for young children could enhance their enjoyment in accessing the documentation and develop their dispositions to participate in constructing learning through play activities, even for the very young.

Tools for ‘listening’ to parents’ and guardians’ voices

Another expected purpose for pedagogical documentation in ECEC practices concerns the voices of parents and guardians. Many studies have investigated pedagogical documentation as a strategy for interacting with children and parents, which stimulates discussion between practitioners and parents (Carr and Lee Citation2019; Knauf Citation2015). Pictorial pedagogical documentation facilitated such processes (Walters Citation2006; Reynolds and Duff Citation2016). As noted earlier, documentation serves as both a tool to record facts and a mediator for information about children’s lives at home and ECEC settings (Rintakorpi, Lipponen, and Reunamo Citation2014). The same documentation that can make children’s feelings and interests visible can help their parents and practitioners understand the children’s perspectives. The documentation can enable parents to recall and share their pedagogical experiences with children at home by exploring the documentation processes with the children. Similarly, the practitioners can recall and share the children’s at-home experiences. Moreover, pedagogical documentation provides a means for parents and guardians to share their experiences with members of their immediate and extended families (Reynolds and Duff Citation2016).

Recent studies on sharing ECEC practices with parents and guardians through pedagogical documentation have discussed parents’ and guardians’ participation in the process (Birbili and Tzioga Citation2014; Picchio, Di Giandomenico, and Musatti Citation2014). It relates to the eligible role of parents and guardians as active co-constructors of ECEC (Rintakorpi and Reunamo Citation2017). Studies have asserted that family engagement enhances the quality of ECEC (Prieto Citation2018). However, it would not be easy for some parents and guardians to document their children’s meaningful episodes in the same way as practitioners, even if they were involved in the documenting process (Rintakorpi, Lipponen, and Reunamo Citation2014). Thus, it is essential to explore how to elicit parents’ and guardians’ multilayered voices about children’s activities through the documentation for individual parents and guardians. Providing opportunities for parents and guardians to reflect either their own views or vocabularies about their children through pedagogical documentation becomes a first step toward involving the parents and guardians in practical activities as co-constructors of ECEC, which would be linked to co-managing the curriculum of the ECEC settings.

In light of the findings from previous studies, this project shared hard copies of the pedagogical documentation addressed to children with parents and guardians. The reason for using hard copies rather than digital resources was to encourage interactions between parents and guardians about children’s play, learning, and other activities, enabling them to participate in ECEC practices actively.

‘Listening’ to practitioners’ voices for pedagogical documentation

The views of ECEC practitioners must be respected when conducting and developing the pedagogical documentation process for listening to the voices of children, parents, and guardians. In the Reggio Emilia context, pedagogical documentation is also regarded as a form of professional development for teachers (Kalliala and Pramling Samuelsson Citation2014). However, not all practitioners welcome pedagogical documentation, although they might recognise its importance (Knauf Citation2015), partly because of the practical issues associated with the documenting. For example, the ubiquity of electronic visual data requires that practitioners learn skills and strategies to handle digital photos and videos. Some practitioners are daunted by the potential for, and volume of, visual data, knowing that it can involve time-consuming review, conversion, sorting, storage, and reproduction processes (Pyle and DeLuca Citation2017). Practitioners cannot avoid the challenges and hindrances involved in documentation practices in their everyday work, including time constraints, technical issues, learning documentation methods, and other tasks (Rintakorpi Citation2016).

Carr’s (Citation2001, 94–95) guidelines for assessment in ECEC proposed two prinicples for addressing practitioners’ concerns: ‘Assessment process will be possible for busy practitioners’ and ‘The assessment will be useful for practitioners.’ Although considerable research has been devoted to the significance of pedagogical documentation as a tool for understanding and promoting children’s learning in ECEC practices over the past two decades (e.g. Carr and Lee Citation2012, Citation2019), little attention has been paid to the manageability of the pedagogical documentation for busy ECEC practitioners. Consequently, further research and practices need to consider the strategies to encourage more ECEC practitioners to conduct and continue pedagogical documentation to promote the participation of children, parents, and guardians and not just to emphasise educational assessments. This issue needs to be examined in the context of the social and cultural backgrounds of ECEC pedagogies in which practitioners are embedded.

Research questions

This study’s overall goal was to explore the possibilities of pedagogical photo documentation through ECEC practices to listen to the voices of children, parents, and guardians in a way that is manageable for practitioners to maintain. Photo documentation can play a central role in capturing and improving the quality of child-centred ECEC practices through the discourse of meaning-making. Specifically, this study focused on the documentation form and how it facilitated the participation of children, parents, and guardians in ECEC practices. The research questions were as follows:

How does pedagogical photo documentation addressed to children contribute to the development of their play? Does it encourage children’s participation in the assessment process of their learning through play-based ECEC practices?

How does the pedagogical photo documentation addressed to children inspire parents’ and guardians’ views and enhance opportunities for their communication about children’s play and learning? Does it encourage the participation of parents and guardians in ECEC practices?

Materials and methods

Data collection and participants

This action research project with kindergarten practitioners, ‘Wall Newspapers for Children’, has been carried out since 2014. The practitioners gathered several daily class photos on a wall display as pedagogical documentation addressed to children. The data for this study were obtained through specific observation and a questionnaire survey of the children’s parents or guardians concerning documentation. The questionnaire was conducted in the academic years 2016–2017, 2017–2018, and 2018–2019. Altogether, 194 parents and guardians completed the questionnaire (see ). We asked 74 participants (38.1%) of the 194 to answer the questionnaire again after a year because their children were in kindergartens for more than one year. The cumulative total of participants for three years was 268 parents and guardians. The total response rate of the questionnaire survey was 93.3% (n = 250).

Table 1. Questionnaire participants: number of parents and guardians in each academic year.

Two Japanese kindergartens, Hill and Pine (pseudonyms), participated in this project. Although both kindergartens were in the same prefecture in Japan, Hill is in a regional town, and Pine is in the urban centre of the prefectural capital. These kindergartens were attached to the same faculty of education at a national university. Hill kindergarten had 8 teachers, with 78 children divided into three classes based on the children’s age – three, four and five. Two of the classroom teachers were actively involved in this project as co-authors of this study. Pine kindergarten, joining this project in 2017, had four teachers, with 60 children divided into two classes based on the age of the children – four and five. Each class in both kindergartens had a classroom teacher and an assistant teacher.

In Japan, kindergarten is one of the ECEC provisions for children aged three to six. It generally operates for four hours per day. The current national curriculum for kindergarten (Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology Citation2018) states that offering safe, stimulating, and challenging environments for children’s play is crucial for a thoughtfully planned curriculum because children’s learning processes are facilitated through play. This educational philosophy – recognising the value of play – is shared by the national guidelines for nurseries (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare Citation2018).

None of the recommendations – the curriculum, the guidebook for kindergartens, the national guidelines for nurseries – provides any concrete instruction on how to carry out pedagogical documentation to describe and facilitate children’s play. However, they all emphasise that practitioners must understand children’s behaviour in their play in ECEC settings. Text-based pedagogical documentation to reflect on their practices is widely distributed throughout the ECEC provisions in Japan, and some settings use photos to share their pedagogies with parents and guardians. Consequently, there are varying methods used for pedagogical documentation, although each ECEC provider in Japan must be familiar with its broad purposes.

In the participating kindergartens, the practitioners made pedagogical written documentation to reflect their daily classroom practices and children’s activities and used it for regular staff meetings. In the meetings, their colleagues usually shared their practices to review and improve their future plans and curricula.

Materials and procedures

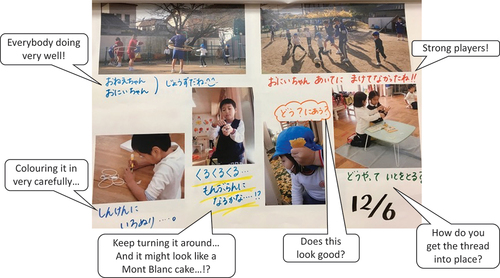

We instructed the practitioners to focus on children’s free play activities and take photos as they played with the children, to capture the children’s viewpoint. Next, we asked them to edit the pedagogical photo documentation to encourage the children to develop their play by themselves; the result usually included three to seven photos. The practitioners could choose the photos from the 20 or so photos they had taken on that day and arrange them on a sheet of A3-sized paper. They sometimes added brief comments or illustrations by hand, such as children’s private speech ().

Figure 1. A sample of daily class photo documentation: on 6 December 2016 for a class of five-to six-year-olds.

The practitioners could choose their favourite photos of children’s play without constraints in the documentation editing process because we wished to minimise the time required to compose it. The photo documentation from each day was pinned onto the previous ones for the wall display in the classroom before the students arrived the next morning. Thus, the children could see both the current and previous documentation.

The classroom teachers collected narrative observational episodes accounting for the documentation’s influence on children’s play activities and interactions. We regularly engaged with the classroom teachers to help them collect the narrative observational episodes and briefly interviewed the practitioners informally. We held meetings with the teaching staff in the participating kindergartens a few times every academic year to share and interpret the episodes and discuss how the documentation inspired the children’s play.

As the first step in this project, we gave all the participants an explanation of the procedures and obtained consent for photo usage and the ethical conditions of the study from parents and practitioners. Before participants completed the questionnaire, we informed them that their responses were confidential, then fully debriefed them and thanked them for their time.

Other datasets: a questionnaire for parents and guardians

Parents and guardians had access to copies of all documentation since May 2016. The practitioners usually provided brief captions to explain the scenes in the documentation only in the copies intended for the parents or guardians. They displayed the copies next to the entrance to each classroom so parents and guardians could view them whenever they visited the classrooms or picked up their children to take them home.

We collected other datasets by administering a questionnaire to the parents and guardians about how the documentation inspired them. We designed the questionnaire based on the research on photo documentation composed by practitioners and parents (Matsui Citation2015), modifying the items through discussion among the authors. We asked the parents and guardians about their backgrounds, how much the documentation had enhanced their interactions, and other open-ended questions (e.g. memorable examples or comments from the documentation). We asked them to rate each of 20 items on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). We administered the survey in January 2017 for a class in the academic year 2016–2017; in December 2017 for four classes in the year 2017–2018; and in January 2019 for five classes in the year 2018–2019 (see ).

Table 2. Numbers of classes that participated in this project.

Results

Specific observations: pedagogical photo documentation for children

The following sections report on the narrative episodes of children’s play mediated by pedagogical photo documentation collected by the classroom teachers and shared with the staff and the authors at regular meetings. The children’s dispositions to use the documentation to inform their participation in play were gradually enhanced throughout each academic year.

Encouraging children’s participation and involvement in subsequent play activities for several days

We found that the documentation fulfilled its role of letting children feel safe and relaxed in a new environment whilst they discovered and enjoyed their play in the initial stages of the school year. When the project started, most children in the classroom showed an interest in the documentation on the wall. The five- and six-year-old children often requested that practitioners document their play activities. Afterwards, they checked whether their pictures had been posted in the documentation. In contrast, the three- and four-year-olds rarely asked to be photographed during play activities at the beginning but usually looked forward to seeing the documentation, including their own photos. The documentation, including their own photos, encouraged children to show an interest in their novel play and communicate with practitioners. Some cases suggested that providing feedback through this documentation, especially for the three-year-olds, put them at ease and provided opportunities for interactions to initiate further play.

After the initial stages, the children’s interest in the documentation gradually changed as they became accustomed to it. Over time, they expressed less interest in whether their photos were included. Nevertheless, we found that its new function had been served – that is, they obtained information about their play through the documentation. The following vignettes suggested that the documentation could help the children enjoy their play continuously. Hence, recalling and reflecting on their play through documentation motivated the children to come up with and import new ideas into their play.

Episode 1: Three- and four-year-old children (mid-February 2016)

On Friday, a few children poured sand into the hole in the table whilst they enjoyed pretend-playing ‘barbeque’ in a sandpit. Next, they accidentally figured out how to make a heap of sand under the table. Practitioners included the scene in the documentation.

After lunch the following Monday, whilst looking at the documentation, Kana said happily, ‘Oh, I’m gonna do it starting now. Miss! Look, it’s a barbeque yesterday!’ ‘Me, too!’ said other children. Her ideas rapidly spread to others. ‘Please look, Miss. This is a barbeque.’ Kana pointed out the photo and repeated what she had said to the practitioners. Kana and her friends tried to make a higher heap under the table than on previous days. One of them proposed adding a small amount of water to the sand based on her experiences of previous play. Three days later, the sand heap finally reached directly below the table board. (see )

Episode 2: Five- and six-year-old children (9 September 2015)

Some girls started to enjoy gymnastics and dance with music. Natsumi rarely joined them and usually just watched their activities instead, although she seemed to want to join. The practitioners picked photos of moving and dancing in the documentation. Two days after the documentation was displayed, Natsumi looked at some pieces on the timeline. She then called a few friends over to the documentation, pointed out the photos of their activities, and chatted with them. Then she said, ‘Let’s keep on it!’ to her friends and started playing, smiling. After that, she spontaneously enjoyed challenging gymnastics movements such as cartwheels, bridges, and others.

Enhancing the quality of children’s play on their own

The documentation often encouraged children to talk about their play with others, even if they had not played together. The following vignette showed that the children could develop their play, which was mediated by the children’s interactions through documentation. Specific observations have indicated that communication among the children, enriched by documentation, enables them to develop and create their own play.

Episode 3: Five-and six-year-old children (16 September 2015)

Haru found a mantis egg case on the branch of a cherry tree on the playground. He took a picture of it and looked it up in an illustrated encyclopaedia for children with his friend Nene. ‘We can all share, can’t you?’ Nene said to Haru. Haru was inspired by Nene’s comments and created the original ‘documentation’ to share his findings with others. His documentation contained printed photos of the mantis egg case, photocopies of various kinds of mantises from the illustrated encyclopaedia, and some captions to explain them (). Haru’s ‘documentation’ was displayed on the wall and introduced to everyone during class assembly.

Questionnaire study: pedagogical photo documentation for parents and guardians

The results of the questionnaire showed that 171 (88.1%) of the participating parents or guardians (n = 194) saw the documentation. Asked about the number of interactions with others inspired by the documentation, the parents or guardians gave the following responses: (1) daughters and sons (n = 154; 79.4%); (2) the parents or guardians of other families (n = 132; 68.0%); (3) family members (n = 95; 49.0%); (4) classroom teachers (n = 63; 32.5%); (5) classmates of their children (n = 34; 17.5%); and (6) other teaching staff (n = 17; 8.8%).

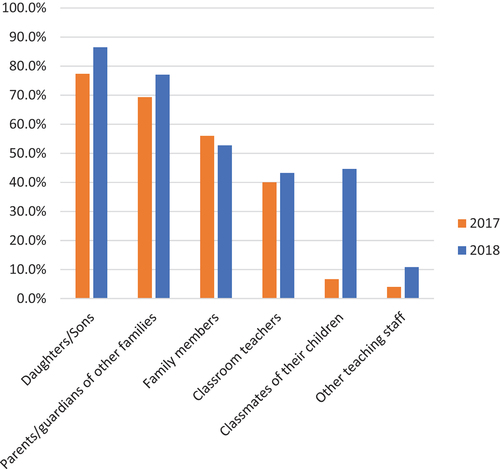

Over two years, 74 parents or guardians completed the survey. shows a two-year comparison of repeat participants who held conversations with others inspired by the documentation. Although the trends for each item were broadly similar between the first and second year, there was a large increase in the rate of parent or guardian interactions with their children’s classmates (from 6.7% to 44.6%). A related-samples McNemar’s test revealed significant differences in the percentage of participants who interacted with their children’s classmates between the first survey and the second survey one year later, z = 27.03, p < .001.

Figure 4. A two-year comparison: how the documentation affects parents’/guardians’ interactions (n = 72).

shows the mean scores and standard deviations of each item in the survey regarding the experiences of the parents or guardians derived from the documentation (n = 179). Using paired sample t-tests, we compared the results between the first and second years for the 74 participants who completed the survey for two consecutive years. We found no significant differences except for an item on understanding what or how the children were doing in the planning or rehearsing processes before school events. For this item, the first-year score was significantly higher than the second-year score, t (65) = 2.08, p = .041, d = 0.36, 95% CI [0.01, 0.71]. This can be accounted for by the improvement in the parents’ or guardians’ knowledge of school events in the second year.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics of the questionnaire for parents/guardians (n = 179).

To explore which part of the documentation attracted the parents or guardians, we categorised the parents or guardians into one of two groups according to the average number of times their children appeared in the photo documentation in each class: (1) frequent (n = 99; average appearance = 7.38 times per month) and (2) infrequent (n = 80; average appearance = 5.38 times per month). An independent sample t-test (p < .05) showed no significant differences in the mean level of the 19 items that emerged between the frequent and infrequent groups. The infrequent group participants reported significantly more chats with the practitioners about what the children had done at kindergarten than the frequent group, t (163) = 2.01, p = .047, d = 0.31, 95% CI [0.01, 0.62]. Overall, these data suggested that photo documentation inspired the parents and guardians, even when their children did not often appear in the photos.

Discussion

Pedagogical documentation for children

This study explored the contribution of pedagogical photo documentation addressed to children to the development of children’s play and the assessment process of their learning through ECEC practices. We identified the following progression of children’s learning through play, mediated by documentation from the narrative observational episodes. The first and second vignettes illustrate our finding that the children engaged in continued play activities for several days. Sharing the activities among children through documentation inspired them to reflect on their playing and to find new ways to develop it. The third vignette illustrates our finding that the children used documentation to enhance the quality of their play on their own. Their playful interactions through documentation enabled them to create and enrich their various ideas for playing, which was often beyond the adults’ expectations.

These results, mediated by the photo documentation addressed to children, seem to support and extend the suggestions of previous studies of pedagogical documentation in ECEC. As conceived in the Reggio Emilia approach, we found a ‘pedagogy of listening’ when participation was part of documentation practices (Knauf Citation2017). Primarily using photos in the documentation enabled the nonreading children to refer to them and to share with their friends. However, this does not mean that all the children accessed the documentation before creating their play activities. Multimedia tools or direct comments by adults, which are more active stimulants than passive displays, have been shown to strongly, sometimes excessively, influence children’s behaviour. Nevertheless, pedagogical photo documentation offers a variety of options for children, including the option of not taking in the documentation information before enjoying their play.

Consequently, the pedagogical documentation addressed to children could encourage children to engage in their play as subjects able to develop and create their own play. We recognised that it could be playing as play, not play as an academic learning tool hijacked by adults’ opinions. The findings provide further empirical support for listening to young children’s voices through pedagogical documentation, which facilitated child-centred practices and children’s participation. This work underlined the importance of understanding the effects of different forms and addressees of pedagogical documentation on the development of children’s learning through play. Suitable ways to share documentation with children might encourage children’s participation in play-based ECEC pedagogies.

However, we need further explorations of ways to encourage practitioners to conduct, continue, and develop pedagogical documentation. Some practitioners considered the documentation as something that educators do as part of their work in the ECEC centres. Others expressed little interest in creating extensive documentation even when they recognised its value.

The classroom teachers who composed the documentation in this project described how selecting the photos helped them review the children’s learning through their play each day. Whilst the practitioners were choosing the photos and writing the captions, they reflected on whether the children had been excited and fully engaged in their play, predicted whether it was likely to continue the next day, and pondered other questions. The classroom teachers reported that although it took them 20–30 minutes per day at the beginning of this project to prepare the documentation, the amount of time gradually decreased as they became accustomed to doing it.

During this project, the practitioners’ comments suggested that focusing on the children’s play, taking photos with an awareness of meaning-making and development, and later selecting and editing the images for the photo documentation enhanced their understanding of the children’s behaviour and their own educational practice. The findings suggested that the experience of creating photo documentation refocused teachers’ attention on understanding the children’s learning embedded in play and encouraged them to rethink and recognise the practical values of the documentation for improving their pedagogical processes. Reflecting on ongoing children’s play activities rather than past play alone and frequently sharing activities with the children through daily photo documentation from the children’s point of view inspired the children to develop and create new forms of play by themselves. The documentation also fulfilled the functions of recording and evaluating the children’s meaning-making in ECEC settings. The findings from the pedagogical photo documentation addressed to children could help busy practitioners reconsider what assessments are meaningful, manageable, and helpful. Further research focusing on practitioners’ perspectives – that is, exploring practicable, manageable, and enjoyable assessment methods – would expand our understanding of pedagogical documentation in ECEC.

Pedagogical documentation for parents and guardians

Another purpose of this study was to examine how pedagogical photo documentation addressed to children might expand parents’ and guardians’ views and provide opportunities for communication about their children’s play and learning, encouraging the parents’ and guardians’ participation. The main findings of the questionnaire study showed that the pedagogical photo documentation enhanced the parents’ and guardians’ communicative experiences by prompting them to talk with both their children and the other parents and guardians, the practitioners, their children’s classroom peers, and others about their children’s play in ECEC settings. The parents and guardians gradually grew accustomed to interacting with their children’s classmates through the documentation. This supports and extends the findings of Reynolds and Duff (Citation2016), who demonstrated that sharing documentation helped create stronger connections between the centre, home, and extended family.

The questionnaire data also noted hardly any significant association between the impact of the documentation on parents and caregivers and whether their children appeared in it. The most popular approach to using photos held in ECEC settings in Japan is to report on children’s activities on a class-by-class basis for parents and guardians. Practitioners in Japan generally pay more attention than necessary to ensure that all children are evenly represented in their reports, which increases their burden. We expected the parents or guardians to be most interested in the documentation when their children were featured in it. The results were surprising: the parents and guardians whose children were shown infrequently chatted more often with the practitioners about what their children had done in kindergarten. A plausible reason for this result could be that the parents and guardians imagined their children’s activities through the interactions of other children they saw in the documentation. In any case, their interest in it was not directly related to the appearance of their own children in the documentation, suggesting that the practitioners did not need to make a concerted effort to represent all the children all the time.

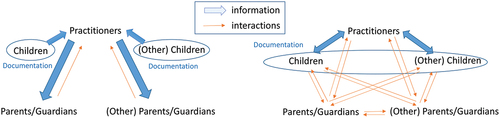

shows the communication processes generated by the assessment tools. As shown on the left side of the figure, educators usually assess children’s academic learning and social skills individually, focusing on each child with a traditional assessment tool or documentation. Each parent and guardian receives information from the practitioners, who ask them directly if they have any enquiries. Consequently, the dimension of the interactions is often limited to interactions between the practitioners and the parent or guardian. As can be seen in the right side of the figure, the photo documentation in this project, despite being primarily addressed to children, was shared with parents and guardians and displayed to encourage everyone (i.e. all the children, parents, guardians, and practitioners) to view and discuss it. If there were enquiries, the parents or guardians had additional points of reference for their discussions with the practitioners who created the documentation and with their own children, other parents and guardians, and their children’s classmates.

This type of documentation seemed to enhance the parents’ and guardians’ communicative experiences and enrich the connections and partnerships among the centre, the homes, and all the concerned parties, including the children. The communicative experiences enriched by documentation could help mediate their interests and enlarge their plural views about ECEC practices. Photo documentation focusing on children’s play activities inspired the parents’ and guardians’ voices even when their children were not featured. Preparing the tools to focus on play activities of all the children in the classroom and affording the children opportunities to share the play activities with their parents or guardians provided the parents and guardians with new insights into their children’s and their classmates’ play. This encouraged them to express their views about ECEC practices spontaneously, making them active co-constructors of ECEC (Rintakorpi and Reunamo Citation2017).

However, it is possible that not all parents will give consent to share their children’s photos with others. Sometimes, practitioners might have to edit the documentation to respect these restrictions. Privacy concerns must take precedence, and this might reduce the applicability of photo documentation.

Limitations and future direction

There are several limitations that need to be considered. First, the study did not explore the possibility of adapting this type of pedagogical documentation for babies, infants, or toddlers. It was easy for young children to find the photo documentation addressed to them, to become familiar with the process, and to refer to the documentation to develop their play activities. Future research should focus on any other role of documentation to enrich the meaning-making of babies, infants, and toddlers in their practices. Notwithstanding these limitations, this project suggests that daily photo documentation addressed to children could help to enhance the understanding of ECEC practices through the discourse of meaning-making.

Second, we need to consider the availability of digital equipment for pedagogical documentation. Although using such technologies was uncommon as recently as several years ago, digital-based documentation has become increasingly popular in the ECEC context. Knauf (Citation2016) illustrated that the use of digital media in kindergartens changed both the quality and quantity of communication; the volume of communication increased, and the communication between teachers and parents had changed from a ‘one-way street’ to a mutual relationship. However, these achievements were not free (Knauf Citation2016).

The present project advances the literature on pedagogical photo documentation in ECEC by demonstrating enhanced interactions among all involved in the ECEC provisions, going beyond the parent–practitioner dyad. Parents and guardians could recognise someone who shared the documentation at the same time and feel comfortable chatting about it with others whilst they looked at paper-based photo documentation of groups of children. However, multimedia tools could be used for documentation. This might make it easier for parents and guardians to visualise their children’s behaviour but more difficult for them to share and communicate with each other about it than photos affixed to a wall, where the scene in focus is fixed.

Consequently, shared paper-based documentation could contribute more positively to a greater variety of views and voices from parents and guardians about children’s activities than information on digital social networks or multimedia documentation, even if the content is the same. Research exploring the strengths and limitations of sharing children’s play activities digitally would expand our understanding of pedagogical documentation in ECEC.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the children, families, and practitioners at both kindergartens for participating in this project. All the participants were given pseudonyms in this study.

Portions of these data were published at Matsumoto, Nishiu, Taniguchi, Kataoka and Matsui (2018), and presented at the TACTYC 40th Anniversary Conference 2018, Derby, UK, the South East England Early Childhood Research and Practice Association event, Canterbury, UK (2019), and the Japan Society of Research on Early Childhood Care and Education National Conference of 70th (2017), 72nd (2019), and 73rd (2020). We wish to thank Ms Yoko Urano, Ms Mariko Kaji,Footnote1 and Ms Chiaki TsudaFootnote2 (Takamatsu Attached Kindergarten, Faculty of Education, Kagawa University, Takamatsu, Japan) , and Associate professor Paul Batten (Kagawa University, Japan) for their contribution throughout this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Present address: Mayumi Kindergarten, Takamatsu, Kagawa, Japan.

2. Present address: Kagawa Prefectural Kagawa Chubu Special School, Takamatsu, Japan.

References

- Birbili, M., and K. Tzioga. 2014. “Involving Parents in Children’s Assessment: Lessons from the Greek Context.” Early Years 34 (2): 161–174. doi:10.1080/09575146.2014.894498.

- Brooks, E., and J. Murray. 2018. “Ready, Steady, Learn: School Readiness and Children’s Voices in English Early Childhood Settings.” Education 3-13 46 (2): 143–156. doi:10.1080/03004279.2016.1204335.

- Buldu, M. 2010. “Making Learning Visible in Kindergarten Classrooms: Pedagogical Documentation as a Formative Assessment Technique.” Teaching and Teacher Education 26 (7): 1439–1449. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2010.05.003.

- Carr, M. 2001. Assessment in Early Childhood Settings: Learning Stories. London: Paul Chapman.

- Carr, M., and W. Lee. 2012. Learning Stories: Constructing Learner Identities in Early Education. London: SAGE.

- Carr, M., and W. Lee. 2019. Learning Stories in Practice. London: SAGE.

- Dahlberg, G., P. Moss, and A. Pence. 2013. Beyond Quality in Early Childhood Education and Care: Languages of Evaluation. Routledge Education Classic ed. London: Routledge.

- Elfström Pettersson, K. 2015. “Sticky Dots and Lion Adventures Playing a Part in Preschool Documentation Practices.” International Journal of Early Childhood 47 (3): 443–460. doi:10.1007/s13158-015-0146-9.

- Goouch, K. 2008. “Understanding Playful Pedagogies, Play Narratives and Play Spaces.” Early Years 28 (1): 93–102. doi:10.1080/09575140701815136.

- Kalliala, M., and I. Pramling Samuelsson. 2014. “Pedagogical Documentation.” Early Years 34 (2): 116–118. doi:10.1080/09575146.2014.906135.

- Knauf, H. 2015. “Styles of Documentation in German Early Childhood Education.” Early Years 35 (3): 232–248. doi:10.1080/09575146.2015.1011066.

- Knauf, H. 2016. “Interlaced Social Worlds: Exploring the Use of Social Media in the Kindergarten.” Early Years 36 (3): 254–270. doi:10.1080/09575146.2016.1147424.

- Knauf, H. 2017. “Documentation as a Tool for Participation in German Early Childhood Education and Care.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 25 (1): 19–35. doi:10.1080/1350293X.2015.1102403.

- Lancaster, Y. P., and P. Kirby. 2014. “Seen and Heard: Exploring Assumptions, Beliefs and Values Underpinning Young Children’s Participation.” In Contemporary Issues in the Early Years, edited by G. Pugh and B. Duffy, 91–108. London: Sage.

- Matsui, G. 2015. “Improving Parent Involvement in a Day Care Center through Making Portfolios.” The Japanese Journal for the Education of Young Children 24: 39–49. (in Japanese with English abstract).

- Merewether, J. 2018. “Listening to Young Children Outdoors with Pedagogical Documentation.” International Journal of Early Years Education 26 (3): 259–277. doi:10.1080/09669760.2017.1421525.

- Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. 2018. “Yochien Kyoiku Yoryo Kaisetsu [Practical Guide of the Course of Study for Kindergarten].” http://www.mext.go.jp/component/a_menu/education/micro_detail/__icsFiles/afieldfile/2018/04/25/1384661_3_3.pdf (in Japanese).

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. 2018. “Hoikusho Hoiku Shishin Kaisetsu [Practical Guide of the Guidelines for Nursery Care].” http://www.ans.co.jp/u/okinawa/cgi-bin/img_News/151-1.pdf (in Japanese).

- Murray, J. 2019. “Hearing Young Children’s Voices.” International Journal of Early Years Education 27 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1080/09669760.2018.1563352.

- OECD. 2015. Starting Strong IV: Monitoring Quality in Early Childhood Education and Care. Paris: OECD Publishing. doi:10.1787/9789264233515-en.

- Picchio, M., I. Di Giandomenico, and T. Musatti. 2014. “The Use of Documentation in a Participatory System of Evaluation.” Early Years 34 (2): 133–145. doi:10.1080/09575146.2014.897308.

- Prieto, J. P.-A. 2018. “Enhancing the Quality of Early Childhood Education and Care: ECEC Tutors’ Perspectives of Family Engagement in Spain.” Early Child Development and Care 188 (5): 613–623. doi:10.1080/03004430.2017.1417272.

- Pyle, A., and C. DeLuca. 2017. “Assessment in Play-based Kindergarten Classrooms: An Empirical Study of Teacher Perspectives and Practices.” The Journal of Educational Research 110 (5): 457–466. doi:10.1080/00220671.2015.1118005.

- Reynolds, B., and K. Duff. 2016. “Families’ Perceptions of Early Childhood Educators’ Fostering Conversations and Connections by Sharing Children’s Learning through Pedagogical Documentation.” Education 3-13 44 (1): 93–100. doi:10.1080/03004279.2015.1092457.

- Rinaldi, C. 2006. In Dialogue with Reggio Emilia. London: Routledge.

- Rintakorpi, K. 2016. “Documenting with Early Childhood Education Teachers: Pedagogical Documentation as a Tool for Developing Early Childhood Pedagogy and Practises.” Early Years 36 (4): 399–412. doi:10.1080/09575146.2016.1145628.

- Rintakorpi, K., L. Lipponen, and J. Reunamo. 2014. “Documenting with Parents and Toddlers: A Finnish Case Study.” Early Years 34 (2): 188–197. doi:10.1080/09575146.2014.903233.

- Rintakorpi, K., and J. Reunamo. 2017. “Pedagogical Documentation and Its Relation to Everyday Activities in Early Years.” Early Child Development and Care 187 (11): 1611–1622. doi:10.1080/03004430.2016.1178637.

- Schiller, W., and J. Einarsdottir. 2009. “Special Issue: Listening to Young Children’s Voices in Research—Changing Perspectives/Changing Relationships.” Early Child Development and Care 179 (2): 125–130. doi:10.1080/03004430802666932.

- Walters, K. 2006. “Capture the Moment: Using Digital Photography in Early Childhood Settings.” Research in Practice Series 13 (4): 1–22. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED497542.pdf