ABSTRACT

Scholars have explored the impact of technological developments on the livelihoods of musicians before digitalisation and in the contemporary age of music streaming platforms. However, a striking gap exists with respect to the Indian music industries which have been conspicuously ignored by scholarship on cultural work. This article contributes towards addressing this gap. First, we show how platformisation is challenging the longstanding domination of Indian music by film soundtracks which relegated non-film musicians to precarious careers with unsustainable work. We show that platformisation has ushered in a new wave of non-film music that is posing unprecedented challenges to the cultural hegemony of film music. Second, we show how platformisation has also accelerated demands for copyright reform, which may benefit some musicians. However, third, we show that platformisation may well reinforce the domination of powerful local record companies, with potentially negative impacts on musicians. Fourthly, we suggest that platformisation may be disadvantaging musicians who work in languages besides the dominant ones of Hindi and English. Our concluding section suggests that platformisation brings both challenges and potential benefits for some musicians and draws out the implications for future research on the platformisation of cultural work.

1. Introduction

Digital platforms have proliferated across many industries. Nieborg and Poell (Citation2018, 4276) define platformisation as ‘the penetration of economic, governmental, and infrastructural extensions of digital platforms into the web and app ecosystems’ (italics in original). Platformisation in the cultural industries is especially significant for recording musicians because music streaming platforms (MSPs) account for more than 62% of global recorded music revenues (IFPI Citation2021). The platformised recorded music industry allows musicians access to global markets and offers them more flexibility than pre-digitalisation business models in getting their work distributed. However, many have claimed that the platform economy may have aggravated longstanding and persistent issues facing musicians, such as inequality and precariousness (Baym Citation2018; Prey Citation2020a; Baym et al. Citation2021). So, the platformised recorded music industry is a rich test case for studying the impact of digitalisation on cultural workers.

India’s recorded music industry has grown rapidly in recent years (IMI Citation2022b) and has been described as ‘the sleeping giant’ of global music markets (Hu Citation2017). In 2020, music streaming revenues accounted for 85.1% of overall recorded music revenues in India (IMI Citation2022a, 8). Furthermore, in a short span of three years, India has entered the top 10 markets for Spotify (Singal Citation2022), the largest MSP in the world. In addition, there is a huge informal music sector (Dredge Citation2022b), i.e. it falls ‘outside the official, authorized spaces of the economy’, though often in interaction with the formal sector (Lobato and Thomas Citation2015, 7).

Academic researchers have analysed the evolution of the Indian recorded music industry and the emergence of new technologies. Manuel has traced the impact of successive waves of technological change through studies of cassette tapes (Citation1993), video compact discs (Citation2012), and online technologies (Citation2014). Booth (Citation2017) analysed how digitalisation and mobile platforms were affecting a regional record company. Ithurbide (Citation2020) offered a detailed description of changes brought about by the MSPs in the Indian recorded music industry. Furthermore, a rich literature on Indian music culture can be found embedded within studies of the Indian film industries, especially Bollywood (Cullity Citation2002; Lorenzen and Täube Citation2008; Beaster-Jones Citation2009; Punathambekar Citation2013; Ciochetto Citation2013; Kumar Citation2017).Footnote1 However, while most of these scholars acknowledge the aesthetic and commercial importance of music in Indian films, few focus on workers in the Indian music industries, with exceptions such as the attention given to prominent Indian musicians such as A.R. Rahman (Punathambekar Citation2007; Beaster-Jones Citation2017). There has also been discussion on the impact of Indian copyright laws on musicians’ royalties by scholars such as Reddy (Citation2012), Reddy and Chandrashekaran (Citation2017), and Booth (Citation2015). But the livelihoods of Indian musicians have rarely been examined in their own right as creators of film or non-film music.

We use the terms ‘film music’/‘non-film music’ to signify all music that is/is not ensconced in films when it is first made available for audience consumption and to categorise musicians who predominantly produce the respective music. The term ‘independent’ is usually associated with those musicians whose music is ‘not produced under a contract with a commercial [major] record label’ (Rohmetra Citation2022). A vast majority of Indian non-film musicians are independent and platformisation has especially enabled their growth. It has also allowed film musicians to pursue parallel independent musical careers. We focus on these dramatic effects in this article.

Recent years have seen a number of studies on the impact of platformisation on musicians (Coulson Citation2012; Marshall Citation2015; Negus Citation2015; Baym Citation2018; Hanrahan Citation2018; Haynes and Marshall Citation2018; Hoedemaekers Citation2018; Morris Citation2020; Prey Citation2020b; Azzellini, Greer, and Umney Citation2021; Baym et al. Citation2021; Hesmondhalgh et al. Citation2021), but the literature on Indian recorded music has tended to neglect these questions. A partial exception is Nowak’s (Citation2014; Citation2018) work on the musicians of Garhwal, a Himalayan region in north India. Nowak’s findings chronicle the opportunities and challenges infused by digitalisation into the regional Garhwali music industries, and also highlight the relationships, aspirations, and strategies deployed by Garhwali musicians to sustain a livelihood in music. But while Nowak focuses on Garhwali musicians, this article sets a strong research agenda for scholars of contemporary Indian music to holistically understand the myriad ways in which digitalisation is potentially shaping the recording careers of Indian musicians at a national and transnational scale.

This article contributes towards filling the above gap in scholarship by examining how musicians in India might be affected by evolving relations between the Indian recorded music industry on the one hand, and digital music platforms on the other. We consider a number of effects of platformisation, distinguishing between those that might in some cases benefit musicians, and in other cases disadvantage them (at least beyond the biggest superstars). We discuss four major impacts of platformisation, starting with two potentially positive aspects which may enable a more plural and sustainable footing for Indian music outside the film music establishment; and then turning to two sets of problems which risk further entrenching inequalities in Indian music. Through this discussion, we sketch out a research agenda for better understanding work in the Indian recorded music industry.

In Section 2, we discuss how the recorded music industry in India has traditionally been dominated by film soundtracks, especially Bollywood music, but how the emergence of national and international MSPs has benefited non-film musicians to a surprising degree. Some musicians and firms beyond the film sector are now achieving considerable success and posing unprecedented challenges to the cultural hegemony of film music. Section 3 then discusses the history of copyright reform in India, arguing that platformisation may involve dynamics that accelerate efforts towards reform. However, Section 4 shows that platformisation also consolidates the advantage of the oligopoly of local, domestic majors, thereby disadvantaging musicians, for reasons elaborated below. Section 5 suggests that platformisation may disadvantage the many musicians working in regional minority-language markets, given the preponderance of Hindi and English on Indian MSPs. Finally, the concluding section raises important issues that lay an agenda for future research. Throughout, the article draws upon both critical political economy and cultural studies perspectives to foreground issues of power and inequality that shape work in the Indian recorded music industry, particularly in the consequences of the expanding use of digital platforms.

The article is based on an interdisciplinary literature review which synthesises recent literature on the trajectory of the Indian recorded music industry on one hand, and literature on the platform economy and cultural work on the other. An extensive reading of recorded music industry reports published by industry organisations (IFPI, FICCI, IMI), specialised trade magazines, newspaper articles, and grey literature was also required to comprehend the changing dynamics and lay the groundwork for future research. A close examination of the music offerings on the home pages of different MSPs’ apps was also undertaken.

How do we define ‘musicians’ in this article? In short, the term covers those who perform or write music. Our interest is primarily in those musicians who seek to make a living, or a partial living, from music. We also emphasise the boundary between the formal and informal sector. Although some musicians work in both sectors, sometimes even unintentionally, our focus is on the ‘formal’ recorded music sector wherein lyricists, composers, and performers receive credit for their work and are entitled to royalties. Our article considers all such roles and when distinctions need to be made, we use the individual terms. The term ‘musicians’ without any prefix also includes film, non-film, and independent musicians, and we provide appropriate qualifiers wherever necessary.

2. Platformisation challenges the dominance of film music

The recorded music industry has been regularly disrupted by, and has had to adapt to, technology – from vinyl records to audio cassettes to CDs to the digital world of today – and these changes have historically impacted how musicians relate to audiences (Baym Citation2018). Hesmondhalgh (Citation2019, 294) claims that ‘[t]he music recording industry was the first major cultural industry to be affected by … ‘digitalisation’’. Manuel (Citation2014) explains that each generation of technology from cassettes to MP3 discs to file-sharing over the Internet worked towards adding exponential scale to the distribution of increasingly larger volumes of music with ease. Sterne (Citation2006, 829) describes how the ‘possibility for quick and easy transfers, … cross-platform compatibility, … and easy storage and access’ were built into the very design of the MP3 file compression technology; a design that lends itself well to illegal file sharing. Rampant piracy through digital music files crippled the business of music rights holders in the early twenty-first century and the Indian recorded music industry ‘experienced the same vicissitudes as its counterparts in the developed world’ (Manuel Citation2014, 392). However, despite all the tribulations of coping with technological developments from the front, a distinctive feature of the Indian recorded music industry has remained unwaveringly resilient: its dependence on the Indian film industry.

The Indian recorded music industry has always been intrinsically linked to the Indian film industry. Music culture in India, at an industrial scale, has been very largely based on film soundtracks. Furthermore, while the production and distribution of recorded music have been dominated by major international record companies in most countries, India by contrast has powerful domestic record companies and the international majors play a relatively limited role.Footnote2 Sony Music is the only one among the three international majors (the others are Universal Music and Warner Music) with enough substantial investments in Bollywood and south Indian film music for its Indian subsidiary to be counted among the major record companies operating in India (Hu Citation2017). Universal Music in India does not focus on film music (Bhardwaj Citation2021) and Warner Music has only recently started independent operations in India, in 2020 (Warner Music Group Citation2020).

The large scale platformisation and legal monetisation of digital music in India can be traced back to the economic success of various music-based valued-added services offered by telecom companies to attract and retain customers. Telecom services offering music for download, ringtones, and especially caller-ring-back-tones (CRBT), which allowed music to be played for the caller, found enormous success among Indian customers (Gopinath Citation2013, 87; Booth Citation2017, 95). The first CRBT service was launched in India by Bharti Airtel Limited (trading as Airtel), a local telecom company, in 2004 under the brand name Hello Tunes (Chhavi Citation2013) and was soon copied by other telecom service providers. Not long before, Apple had launched the iTunes music store in the US in 2003 (Apple Citation2003) and revolutionised music consumption by offering songs for 99 cents apiece without any subscription fees. This provided the Indian recorded music industry an opportunity to sell Indian songs to diasporic audiences abroad via distributors like DesiHits (Jana Citation2008) and to test digital revenue models. However, YouTube launched its services in India only in 2008 (The Economic Times Citation2008). Two of India’s leading MSPs, Saavn (now JioSaavn) and Gaana, were launched in 2007 (O’Brien Citation2015) and 2010 (The Times of India Citation2020) respectively, and the iTunes India store was only launched in 2012 (Apple Citation2012). This gave enough room to telecom service providers to establish strong and, for some time the only, lucrative digital music business models with Indian recorded music rights holders. With the Phonographic Performance Limited (PPL), which licenses sound recordings in India, increasing its earnings from mobile ringtones by 1857% during the six years from 2004 to 2010 (Reddy Citation2011), music-based telecom services can be considered the harbingers of MSPs in India. Today, Airtel’s music-based value-added services have evolved into Wynk Music which is amongst the largest MSPs in India. The launch of telecom services by Reliance Jio Infocomm Limited in 2015, under the brand name Jio, bolstered the uptake of streaming (Mukherjee Citation2019) by providing one of the cheapest data tariffs in the world (Rai Citation2015). As we discuss next, along with Airtel, Jio remains a significant local telecom operator active in the MSP business.

Today, the music streaming market is driven by telecom as well as local Internet companies (Ithurbide Citation2020). Among the major local MSPs, JioSaavn is owned by Reliance Jio Infocomm Limited which acquired a US-based, India-focused MSP called Saavn; Gaana is owned by a local Internet company called Times Internet Limited; Wynk Music is owned by Bharti Airtel Limited; and Hungama is owned by a local Internet company called Hungama Digital Media Entertainment. Spotify and Apple Music, the leading MSPs in most countries, do not enjoy a dominant position in India, though Spotify is expanding rapidly (Dredge Citation2022a). The other major telecom company, Vodafone Idea Limited, operating under the brand name Vi, also offers music services but does not match up to the scale of Wynk Music or JioSaavn. Amazon Prime Music remains a ‘call product’ (Ithurbide Citation2020, 115) for Amazon to attract and sell its e-commerce services and products to customers.

Indian audiences have never been accustomed to paying for digital music and this has contributed to the Indian music streaming market being dominated by advertising-based rather than subscription-based or transaction-based revenue models (Singh Citation2022). Most MSPs in India, except for Apple Music and Amazon Prime Music, offer both advertising and subscription tiers to consumers and try to migrate them towards subscriptions by lowering their subscription fees (Singh Citation2022; L. Jha Citation2022b). However, they face stiff competition from robust and deeply entrenched advertising-driven platforms like YouTube. In fact, the highest consumption of music happens on YouTube (Ithurbide Citation2020, 115) which has built a base of 450 million monthly active users (Gurbaxani Citation2022b). Furthermore, with the launch of the YouTube Music app in India (the market with the most number of YouTube users) in 2019, YouTube has confronted the MSPs head-on (Global Media Insight Citation2022).

Market shares are as follows: Gaana (30%), JioSaavn (24%), Wynk Music (15%), Spotify (15%), Google Play Music (10%), and Others (6%) (Lidhoo Citation2021). However, these shares may be changing rapidly with the growth of YouTube Music and the recent shifting of Gaana to a subscription-only service (Kalra and Vengattil Citation2022). The below presents a snapshot of the top four MSPs in 2021:

Table 1. Comparison of four of the leading MSPs in India, c. 2021

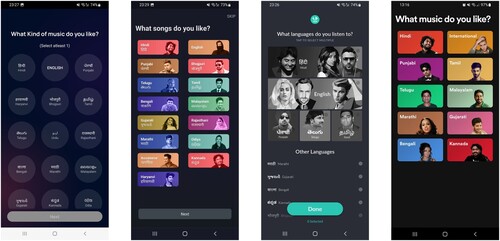

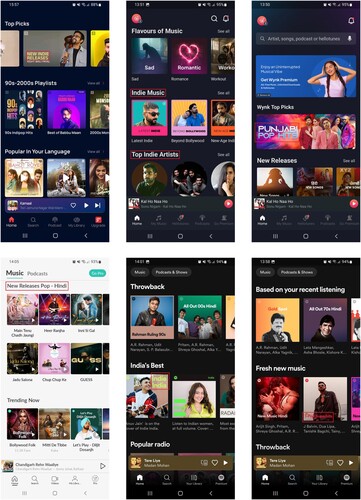

As can be seen, JioSaavn has by far the largest catalogue. Both JioSaavn and Gaana also have exclusive songs funnelled from their respective original non-film recorded music businesses. JioSaavn’s original recorded music business is called ‘Artist Originals’ (stylised as AO) whereas that of Gaana is called ‘Gaana Originals’ (by contrast with the West, where MSPs are prevented from generating content to which they might own rights by licensing agreements with record companies). All four MSPs also provide music across various Indian languages such as Hindi, Punjabi, Tamil, and Telugu, and listening language preferences need to be selected at the time of signing up on the app for the first time (see below). Once logged in, some of the common categories available on all four MSPs involve mood music recommendations, new releases, trending songs, and podcast recommendations. Interestingly, all four MSPs offer non-film music under the ‘pop’ or ‘indie’ categories (see red boxes in below).

Figure 1. Music language selection screen on Indian MSPs (from L-R: Wynk Music, Gaana, JioSaavn, Spotify). Source: screenshots taken by author Lal.

Figure 2. Promotion of ‘indie’/‘pop’ music on Indian MSPs (Top row, L-R: Gaana, Wynk Music, Wynk Music; Bottom row, L-R: JioSaavn, Spotify, Spotify). Source: screenshots taken by author Lal.

Platforms have ushered in novel business models that allow musicians to monetise their music by distributing and marketing their works directly to audiences (for example, by uploading directly to YouTube and SoundCloud). Other business models entail deals with digital distributors and multi-channel networks (MCNs), bypassing deals with recording and publishing companies (Qu, Hesmondhalgh, and Xiao Citation2021).Footnote3

Significantly, the platformised ecosystem of the Indian recorded music industry described above has created a unique opportunity for the rise of non-film music in India. A major contribution to non-film music has come from Punjabi music and the rap and hip-hop genres which have gone mainstream and been appropriated by Bollywood films as well (Bhatt Citation2018; Cardozo Citation2021). Besides Punjabi, music in other languages, such as Bhojpuri, Haryanvi, and Gujarati that do not normally enjoy the patronage of mainstream films, is also expanding via the non-film route (L. Jha Citation2022a).

Admittedly, there was a previous period of growth for non-film music in India in the late 1990s and early 2000s following the advent of cable television in India and the subsequent launch of several music television channels (Rohmetra Citation2022). But this brief flowering soon died out and a popular music culture outside films could not be sustained (Rohmetra Citation2022) by the recorded music industry which as a whole plunged into steep decline from 2002 onwards owing to rising digital piracy and changing patterns and technologies of music consumption (Booth Citation2015, 263). The rise of non-film music in recent times, however, looks to be much more sustainable.

These developments are challenging the cultural hegemony of film music in India. While nine out of the top ten Indian musicians in terms of monthly listeners on Spotify in 2021 were film musicians (out of which eight were from Bollywood) (Keerthana Citation2021), the share of non-film music in the Hindi top 100 charts on Gaana increased from 40% in 2019–65% in 2020 (L. Jha Citation2020). Furthermore, non-film musical products are also finding their way into films via licensing deals in the secondary market (Rohmetra Citation2022).

In its second coming in the age of platformisation, the non-film music market has taken on a stronger industrial form with the entry of a spate of record companies specialising in non-film music (Deb Citation2018; Tagat Citation2020).Footnote4 While most of these record companies have been launched by film and non-film musicians, some such as Big Bang Music (L. Jha Citation2019) and VYRL Originals (Stassen Citation2019) have managed to garner investments from the international majors (Sony Music and Universal Music respectively), signifying a marked shift in the Indian recorded music industry, not seen since the late 1990s, in the form of the infusion of international major record company capital into non-film music. Furthermore, as mentioned above, unlike major western MSPs such as Spotify, the domestic MSPs are also involved in the recorded non-film music industry with JioSaavn’s ‘Artist Originals’ and Gaana’s ‘Gaana Originals’ leading the way. None of this, however, necessarily equates with an improvement in the sustainability of a musical career for the vast majority of musicians working in India’s ‘formal’ music sector (Gurbaxani Citation2022a). As we shall see in Section 3, challenges remain across both film and non-film music, with copyright playing an important role.

3. Platformisation intensifies efforts at copyright reform

Film musicians make significant contributions to the success of Indian films and their songs (Punathambekar Citation2008, 284). Traditionally, they assigned all rights under work-for-hire contracts to film producers who became the first owners of film songs and further licensed or assigned these recordings to record companies along with the underlying works (Reddy Citation2012). This practice was given legal validity by the Indian Supreme Court ruling of 1977Footnote5 which vested the entire first copyright with the film producer or employer who commissioned the work unless there existed a contract to the contrary (Reddy and Chandrashekaran Citation2017, 192). Reddy (Citation2012) highlights some key troublesome interpretations by the Supreme Court of India in its judgment that potentially limit the possibilities for film musicians: the inclusion of music and lyrics in the copyright of cinematographic film; the lack of distinction between film synchronisation and other rights such as public performance rights (right to royalties when sound recordings are communicated to the public via live performance and broadcast); and the absence of criteria to distinguish between employment and work-for-hire contracts. Put together, these ensured that all film musicians’ rights transferred to film producers either as commissioned work or as work produced under employment; and allowed them to exploit these rights as they pleased.

As a result, many famous Indian film musicians have lost substantial lifetime earnings because they have been unable to claim royalties from any subsisting author copyright in their works that were licensed for various purposes outside film such as ringtones, public performances, radio and television broadcasts, and digital downloads and streaming (Reddy Citation2012; Baghel and Dasgupta Citation2017; Hindustan Times Citation2019; Goyal Citation2020). In addition, because film songs were predominantly consumed as sound synchronised with cinematographic film, the success of a song depended upon several other factors apart from the music itself such as the featuring film stars, the visual depiction, and the narrative context (Reddy Citation2012), thereby making it harder for film musicians to negotiate higher wages or royalties. The absence of institutionalised music publishing practices, a lack of knowledge about soundtrack production contracts, weak collective bargaining power to negotiate legal and financial terms (Joshi Citation2011; Reddy Citation2012), and traditional informal systems based on trust and kinship (Lorenzen and Täube Citation2008; Punathambekar Citation2013; Herbert, Lotz, and Punathambekar Citation2020) may have also contributed towards frustrating the endeavours of film musicians to establish fair and equitable rights. The copyright laws and work-for-hire practices also hurt non-film musicians including some iconic figures belonging to other genres such as Indian classical music and ghazal. Some musicians petitioned the government to protect them from predatory record companies by making their right to royalties non-assignable but to no avail (Joshi Citation2011, 23).

The digitalisation of music in the early twenty first century lent new impetus and motivation to musicians’ struggles for fairer rights partly because of the intervention of the booming telecom industry of India. In order to incorporate music into services such as ringtones and CRBTs, the telecom companies had to license music from record companies and licensing and collection organisations such as PPL, which collectively licenses sound recordings on behalf of its record company members, and the Indian Performing Right Society Limited (IPRS) which is responsible for licensing the composition and literary works (i.e. lyrics) underlying the sound recordings (Reddy and Chandrashekaran Citation2017, 203). However, with record companies also on the IPRS board, a subcommittee of the IPRS ruled that ringtones only involved recording rights and no composition/literary rights and so the related royalties would be collected by PPL alone (Joshi Citation2011, 22), thereby once again bringing the exploitation of musician-members (i.e. composers and lyricists) of the IPRS to the fore. Furthermore, musicians’ traditional contracts had not included new technologies such as ringtones (Bhatia Citation2011) and so, most musicians did not receive any share of the monies paid from the telecom companies straight into the coffers of PPL and the record companies. This sparked fresh calls from musicians for a revision of the copyright laws, and the subsequent proliferation of streaming platforms further bolstered their lobbying for urgent reforms.

Changes started taking shape with the election of Javed Akhtar, acclaimed film lyricist, screenwriter, and poet, to the governing board of the IPRS in 2004 and his subsequent nomination to the upper house of parliament in 2009 which gave him better access to ministers and lawmakers. With him leading the IPRS, eventually the Copyright (Amendment) Act 2012 was passed with new rights for musicians (Reddy Citation2012). Under these amendments, musicians can only transfer copyright but not their right to receive royalties (Reddy and Chandrashekaran Citation2017, 197). The revised laws split 25% of the royalty collected for a song equally between the composer and the lyricist and allocated the rest to the rights holder(s) (Joshi Citation2011, 23). Furthermore, the amendments deem any clause that transfers musicians’ rights in future technological mediums as null and void (Reddy and Chandrashekaran Citation2017, 198), allowing the opportunity for musicians to renegotiate terms in the future. The revisions also allow musicians to receive royalties for all uses of their work except in a film played in a cinema hall in India (Joshi Citation2011, 24). Performer royalties were also recognised in these amendments and for the first time playback singers were paid royalties by their collection society, the Indian Singers Rights Association (ISRA), in 2017 (The Hindu Citation2018; Das Citation2018).

However, India is replete with myriad political and socioeconomic tensions and sweeping changes like the above have been hard to enforce (Reddy Citation2012, 527). The country still lacks an organised music publishing industry, confusion persists over musicians’ royalties from radio and television broadcasts, fledgling musicians remain hesitant to oppose unfair contracts out of fear of losing future work (Reddy and Chandrashekaran Citation2017, 208; Ithurbide Citation2020, 123; Rauta Citation2022), and much ambiguity persists not only regarding the lead performer’s share of royalties but also the subjective assignment of credit and royalties for ‘casual or incidental’ (Sivakumar and Lukose Citation2013, 166) performers such as instrument players, music arrangers, sound engineers, backing vocalists, and the likes. In addition, new uses of music on short-video platforms and non-fungible tokens (NFTs) confound the revised laws which in themselves have not been institutionalised yet by the recorded music industry (Rauta Citation2022). The Covid-19 pandemic has also unsettled the system by prompting collection societies to issue new policies regarding the collection of royalties from online live performances (Akundi Citation2020). Furthermore, with the advertising-supported YouTube being the most dominant music consumption platform in the country, the relevance of collection societies to musicians is itself put into question since musicians can earn directly from YouTube (also see Section 4).

Platformisation, then, has accelerated long overdue copyright reforms. However, the road to institutionalising these laws into industry practices has been slow. Furthermore, in an industry characterised by high concentration and winner-take-all effects (Hesmondhalgh Citation2019) it remains to be seen how many of the benefits of these changes trickle down to lower echelons of musicians. We turn to this issue next in the context of changes in industry structures.

4. Platformisation barely dents the power of India’s domestic majors

While digital distribution services might be able to get more music onto western MSPs, few independent musicians can match the marketing and promotion power of the international majors, especially with the low-priced basic services that the distribution companies offer. The international majors enjoy privileged access to resources not just limited to finances and staff but also including data (Baym et al. Citation2021), distribution networks, and promotional alliances (R. Nowak and Morgan Citation2022). Their deep music catalogues allow the international majors to extract better contract terms from platforms and other music retailers (Galuszka Citation2015), since, except for niche stores, no music platform (or physical retailer) can operate without the international majors’ catalogues. On the other hand, independent record companies and distribution services companies managing smaller catalogues may get ‘take-it-or-leave-it deals’ from platforms and retailers (Galuszka Citation2015, 263). The international majors’ vast catalogues also make dealing with them more efficient for music platforms and retailers, as it means they can license the bulk of the recorded music in the industry (Galuszka Citation2015) from a limited number of companies.

There are few signs, then, that the power of the international majors is being meaningfully undermined by platformisation, especially for those independent musicians that aspire to attain stardom (Baym Citation2018, 66) and view commercial success as a validation of artistic skills (Coulson Citation2012; Haynes and Marshall Citation2018).

As we have seen, power is highly concentrated among the domestic majors in India, rather than the international majors who dominate in many countries. Consequently, international MSPs cannot launch their services as successfully in India as in other countries on the back of worldwide licensing deals with the international majors. Domestic majors have asserted their power. For example, domestic major Saregama forced Spotify to remove 120,000 songs owned by Saregama just two months after the streaming service was launched in India (Sanchez Citation2019). The dominance of the domestic majors is also evidenced by the fact that out of the total Indian recorded music industry’s revenue of INR 1,870 crores (FICCI and EY, India Citation2022, 202), Saregama, the only publicly listed major Indian record company, accounts for INR 615 crores (with a market capitalisation of INR 7,367 crores) (The Economic Times Citation2022) and T-Series has an estimated revenue of INR 800 crores (Kohli-Khandekar Citation2021). That is, more than 75% of the industry’s revenue can be attributed to these two record companies alone. Compared to them the revenue of Gaana, the MSP with the largest market share in India, standing at INR 123 crores (Dredge Citation2021) alludes to the lopsided balance of power at the negotiating table.

Furthermore, owing to the unique relationship of record companies and film producers in India (see Section 3), record companies also exert considerable power over the producers. In his interview with Joshi (Citation2011, 23), Akhtar explained that only twelve to fifteen film producers are paid for their films’ music by the record companies. A vast majority of producers not only have to transfer the rights of their films’ music to the record companies for free but must also share the music promotion costs with the record companies in the hopes of promoting their films (Joshi Citation2011, 23). Additionally, the few film producers who get paid by the record companies were also being stripped off their earning potential by transferring their publishing rights to the record companies unconditionally and in perpetuity in exchange for an upfront lump sum payment (Joshi Citation2011, 22–23).

Other major nodes of power include collection societies and rights aggregation companies. The major record companies occupy board positions on the two key licensing and collection organisations, the PPL and the IPRS (Reddy Citation2012), and thereby shape industry-wide decisions related to licensing, collective bargaining, and royalty payments. Unsurprisingly, smaller record companies have assigned organisations such as Novex and Phonographic Digital Limited (PDL) as their agents for administering licenses for public performance (Novex) and digital platforms (PDL). This fragmented membership across different licensing organisations seems to betray friction within the industry in establishing a level playing field even among the record companies. In addition, the powerful marketing campaigns executed by the domestic and international majors also work to effectively isolate smaller independent musicians and record companies (Agrawal Citation2020) from potential revenue opportunities.

As noted in Section 2, the Indian music streaming market is advertising-led, with YouTube driving the maximum consumption of music. This potentially provides an opportunity for Indian independent musicians to subvert the powers-that-be and earn directly from advertising revenue through YouTube. But the largest music channels in terms of subscribers and views on YouTube are controlled by the majorsFootnote6 and large independent record companies, and so, their channels attract far more advertising than those operated directly by independent musicians (or their representatives). A FICCI and EY (Citation2019) report revealed that 40% of the digital revenues for Indian record companies were attributed to YouTube. With the lion’s share of YouTube advertising dollars in the music category going to the majors, advertising income from YouTube will probably not suffice for many independent musicians (A. Nair and Malik Citation2020). However, the advertising industry offers another route to a sustainable livelihood without the need for mediation by record companies.

Several star musicians in India started off in the jingles market for the advertising industry, directly undertaking work like singing, composing, producing, writing lyrics, and voicing (R. Das Citation2016). However, the jingles market too is characterised by the winner-take-all effects prevalent across the cultural industries. It is further complicated by ongoing legal battles between the IPRS and the radio and television broadcasters regarding musicians’ royalties (L. Jha Citation2021) that have effectively made it a work-for-hire market.

The advertising industry has also helped to directly fuel the livelihoods of musicians by way of endorsements and social media campaigns, especially on short-video platforms such as TikTok, Instagram Reels, and YouTube Shorts. TikTok had become an essential music discovery app in India, especially for independent musicians – ‘6 out of the top 10 all-time Indian tracks on TikTok were independent releases and gained considerable traction on YouTube’ (Verma Citation2020). There was a strong correlation between a song’s virality on TikTok and an increase in its listenership on Spotify (Wadhwa Citation2022). In 2020, the Indian government’s ban on various Chinese apps including TikTok led to a surge of indigenous short-video apps such as Moj, Josh, Chingari, Roposo, and MX TakaTak rushing in to fill the void (Wadhwa Citation2022). As important music discovery sites, these platforms not only attract musicians but also advertisers looking to hire musicians for their social media campaigns, and record companies looking to promote their music and license it to these platforms. But the most followed musicians are backed by either a Bollywood repertoire or the majors or both. For example, Neha Kakkar, a popular singer, built an impressive catalogue of Bollywood and non-film projects supported by the majors and became the most followed Indian musician on Instagram with 60 million followers (Vaze Citation2021). Furthermore, despite several options, usage remains concentrated among just a few short-video apps, led by Instagram Reels and YouTube Shorts. While YouTube is the destination for the highest music consumption in India, with 230 million Instagram users India is the largest market in the world for Instagram Reels which is rapidly expanding into the smaller cities (Biswas Citation2022; Dredge Citation2022c) where the domestic apps enjoy a stronger affinity (Business Insider India Citation2021).

Platformisation, then, continues to reinforce the oligopolistic structure of the recorded music industry in India and in the West; and in India we see the power of the domestic majors extend beyond the musicians and the MSPs and impact the film producers and other independent record companies as well. The advertising-skewed Indian platform economy does provide opportunity for independent musicians to generate income without the involvement of intermediaries, but it is not immune to the inequalities and power dynamics at play in the overarching structure of the Indian recorded music industry.

5. Platformisation potentially reinforces the power of musicians performing and working in Hindi and English

Mohan and Punathambekar (Citation2019, 330) explain that states in independent India were reorganised along linguistic lines in 1956 and this led to strong region-state-language links that have been held firmly in place by the production and distribution of culture ever since. Through close readings and analysis of videos produced by a particular YouTube channel they conclude that in India ‘the ‘region’ is the dominant scale at which both industry and user practices are being organised in the digital media industries’ (Mohan and Punathambekar Citation2019, 330). This dynamic is perceptible across the Indian cultural industries. In a recent interview with Hindustan Times, an English daily in India, the CEO of Netflix, Reed Hastings, underscored the regional scale by stating that ‘We kinda treat India like the EU. Many cultures, similar currency, but multiple countries put together, and they love each other most of the time, and share content too’ (Shaikh Citation2021). The MSPs concur. Not just the local MSPs but also the international ones acknowledge that growth depends on penetration into the smaller cities by focusing on regional music which for the likes of Gaana contributes over 35% of total consumption (Lidhoo Citation2021). Gustav Gyllenhammar, vice president, markets and subscriber growth at Spotify, explained in an interview to Fortune India (Lidhoo Citation2021) that ‘India is not one market [but …] a vast region with cultures and languages and different socio-economic realities and we need … to rapidly follow on by winning the tier 2 cities’.

Nonetheless, Hindi is dominant as the putative national language, though not without contest (Mohan and Punathambekar Citation2019), and the Hindi-speaking market (HSMFootnote7) is the most economically vibrant. For example, the international reality format singing competition, Idol, broadcast in India as Indian Idol targets the HSM and features predominantly Hindi songs but enjoys viewership and participation from across the country (Punathambekar Citation2010). Not all participants identify with Hindi as their first language or even claim proficiency in the language, but their performances in the competition must include Hindi songs (Punathambekar Citation2010, 249). The judges and special celebrity guests invited to the show are also predominantly from the Hindi film fraternity, i.e. Bollywood (Punathambekar Citation2010, 247). It is, therefore, not surprising that Bollywood (implied Hindi) music dominates the MSPs in India (IMI Citation2022a, 21).

Another significant factor raised by the geo-linguistic regions within India is a strong preference for music in the local language.Footnote8 International (non-Indian, predominantly English) music in India is growing in absolute numbers but is dropping in share (Jacca Citation2021) despite English being a strong ‘bridge language’ (Mohan and Punathambekar Citation2019, 329) that allows people from different regions and with different native languages to communicate with each other. This inability of international music, whilst growing, to match the overall growth rate of recorded music in the country questions ideas of western cultural imperialism and demands a review of the emphasis in some academic literature on dominant cultural flows from the Global North to postcolonial nations (Herbert, Lotz, and Punathambekar Citation2020) further aggravated by the centralised power wielded by global technology platforms emanating from the West (cf. Jin’s [Citation2015] account of ‘platform imperialism’). In the case of the Indian recorded music industry, we see a resistance to this common narrative not just from the incumbent film music genre but also from local non-film music which, as discussed in Section 2, has been steadily climbing the charts. Resistance to western cultural imperialism can also be evidenced in the fact that Hollywood films still garner only a 14% market share in India (Bamzai Citation2022) and this is owed in no small measure to the practice of releasing dubbed versions of blockbuster Hollywood films in Hindi, Tamil, and Telugu (Hattangadi Citation2020) that employ leading Indian film stars for both dubbing and promotion (Iyer Citation2020; The Times of India Citation2017; Arya Citation2019). In fact, beyond just resistance, there is evidence of counterflows of musical culture from India to the West. Some notable examples are: the sampling of Bollywood tunes in western hits (Kharsynrap Citation2019; Lal Citation2020); the success of musicians from the Indian diaspora (Srivastava Citation2022; Rys Citation2013; Chandran Citation2021); the recent Golden Globe Awards and Academy Awards wins for Indian musician M.M. Keeravani for the song ‘Naatu Naatu’ in the Indian Telugu-language film ‘RRR’ (S. K. Jha Citation2023; Rao Citation2023); Indian musician King breaking into Spotify’s global top song and album charts in 2022 for his non-film album and songs (Loudest Citation2022); Indian musician Arijit Singh featuring among the top ten most followed musicians on Spotify across the globe in 2022, above the likes of Taylor Swift and BTS (Koimoi Citation2022); metal band Bloodywood becoming the first from India to break into the Billboard and U.K. charts in 2022 (Tagat Citation2022); Indian musician Diljit Dosanjh getting billed to perform at Coachella in April 2023 (Outlook Citation2023); and seven out of the top ten musicians on YouTube’s global music chart being from India (Dredge Citation2023). Thus, it is clear from the platform charts that MSPs are not only sites for challenging western musical flows but they also to some extent enable countercultural flows by serving a global audience with Indian music. The charts also reveal that MSPs confirm the domestic cultural hegemony of Indian film music, especially Bollywood music, which itself is being upended by non-film music whose rise is not only encouraged by the inherent affordances of platformisation but also by investments from the majors and the Indian MSPs as discussed in Section 2.

However, notwithstanding the dominance of local languages, local musicians still face the formidable task of navigating domestic and international MSPs which use English as the default user interface language. Meanwhile MSPs face the challenge of judiciously choosing and developing language-based versions of their interfaces (The Economic Times Citation2017). As a result, some local musicians and audiences need to develop their English skills, depend on intermediaries, or remain excluded until platforms develop interfaces in all the local languages. This has important implications for representation for Indian musicians, especially confounding the efforts of regional and rural musicians already vying for visibility in a Hindi-music-dominated market. Language-based issues can frustrate back-end business operations as well. For example, YouTube does not recognise any of the Indian languages except Hindi for its Google Ads interfaceFootnote9 and this limits the ability of regional record companies and musicians to promote their content on YouTube. Furthermore, Google uses the English version of its policies as the official reference for policy enforcement.Footnote10 Such global practices and policies betray a lack of commitment on the part of global MSPs towards empathising with non-Anglophone musicians to make a living off the platform economy.

Thus, we see that India is fragmented along linguistic lines, and while platformisation offers opportunities to musicians from all languages, it also reinforces the systemic domestic and global hegemonies of Hindi and English, respectively.

6. Conclusions

In this article we have presented an overview of platformisation in the Indian recorded music industry and explored some of its implications for the livelihoods of musicians. We saw how platformisation has loosened the hegemonic grip of film music on the Indian recorded music industry and has accelerated demands for copyright reform that may advantage many musicians. But we have also seen how platformisation has reinforced the power of the domestic majors (and international majors are increasingly present), and how it may serve to disadvantage musicians not working with the dominant languages of Hindi and English. In this concluding section, we raise some of the issues that we have not had the capacity to explore in detail, but which may be the basis of future research.

First, the scale and convenience of MSPs’ affordances provide opportunities to a greater number of independent musicians to have their music discovered; but at the same time the highly centralised power wielded by record companies allows these companies to negotiate better deals with MSPs with regards to royalty payments and promotions, thereby effectively crowding out the discoverability of independent, non-film music. So, is optimism concerning non-film music justified? Has platformisation reduced the systemic (over)dependence of Indian musicians on work from the film industry and on the major record companies? How meaningfully has the cultural hegemony of film music been undermined or reinforced by platformisation? These are vital questions for understanding one of the world’s most important music markets, but which remain poorly understood in the literature on platforms and cultural work.

Second, our article illustrates how attention to cultural platforms in a country from South Asia can reveal dynamics quite different from those observed in the Global North. We have highlighted key distinctive features of the Indian recorded music industry, viz. the cultural hegemony of film music, unique copyright laws, strong influence of local record companies and local MSPs, undermining of international western music by local musical preferences, and the importance of Hindi and regional languages. These factors co-exist and intertwine in complex ways that question the direct application of prevalent theories, such as those of cultural industry structures and western cultural imperialism, from the Global North to diverse local contexts (cf. work by researchers such as Elbanna and Idowu [Citation2022] on potentially positive results of crowdsourced work in Nigeria). Critical research on platformisation in the Global North has understandably emphasised negative effects of platformisation (Galuszka Citation2015; Berry Citation2019; Nieborg, Duffy, and Poell Citation2020; Nowak and Morgan Citation2022), but scholars like Nair (Citation2022, 389) have underscored the ‘differences in the political economy of the Global South and North’. Investigation of the working lives and attitudes of Indian musicians in the digitalised recorded music industry might help to further the debate on the need for a modified scholarly approach towards analysing local contexts (Davison and Martinsons Citation2016) and indigenous cultural industries in the Global South (Lorenzen and Täube Citation2008), and to ‘brave highlighting local perspectives’ (Elbanna and Idowu Citation2022, 129).

Third, our article shows that questions remain about the sustainability of non-film music in the wake of platformisation, and in particular the role of copyright. Section 3 explored the evolution of Indian copyright laws, especially the Copyright (Amendment) Act 2012. Yet how effectively have these laws been translated into practice in the Indian recorded music industry and how are the major record companies supporting non-film musicians? What avenues have been made available to film and non-film musicians to learn about their rights and to seek redress in case of continuing traditional practices made illegal by the new laws? What role has the government played in ensuring the implementation of these laws? These questions are once again rarely addressed in existing literature but are vital for understanding the working lives of musicians in India.

Fourth, when people are denied access to information in their own language on the predominantly Anglophonic Internet (Arnaudo Citation2019), the exclusion is ‘both deeply consequential for them and invisible to the dominant culture’ (Plantin et al. Citation2018, 301). How does the continuing operational hegemony of the English language on the MSPs impact the representation of the diversity of musicians and their ability to sustain a living off these platforms in multi-lingual nations such as India? What dependencies does this create for them on Anglophone intermediaries? What training is accorded to local musicians to overcome such language barriers, and are they able to successfully overcome them?

We believe that our overview, and these further questions, help to frame the tensions between the opportunities and challenges afforded by the platformisation of music. Arguably, these are particularly pronounced in the Indian recorded music industry, owing to the huge untapped potential of non-film musicians. The areas of research highlighted here have very serious implications for many musicians and a critical understanding of this underexplored domain could be valuable for shaping future policies and reforms. We hope these questions will pique the interest of colleagues, students, and future researchers, as they do ours.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Aditya Lal

Aditya Lal is a PhD student in the Work and Employment Relations Department at Leeds University Business School. He is also affiliated with the School of Media and Communication at the University of Leeds.

David Hesmondhalgh

David Hesmondhalgh is Professor of Media, Music and Culture in the School of Media and Communication at the University of Leeds, and is the author or editor of 12 books, including Why Music Matters (2013) and The Cultural Industries (4th edition, 2019). From 2021 to 2026, he is leading a major research project on Music Culture in the Age of Streaming, funded by an Advanced Research Grant from the European Research Council. Website: https://musicstreamproject.com/.

Charles Umney

Charles Umney is an Associate Professor in the Work and Employment Relations Department at Leeds University Business School. He is the author or co-author of two books, Class Matters and Marketization, and numerous journal articles including on the subject of working conditions among musicians. From 2022–2025 he is one of the PIs on the international consortium project Humans in Digital Logistics (funded by the CHANSE scheme).

All three authors are affiliated with the ESRC-funded Digital Futures at Work Research Centre.

Notes

1 The word ‘Bollywood’ is sometimes misleadingly used to refer to the Indian film industry as a whole, whereas Bollywood is the colloquial name given to the Hindi film industry based in Bombay (now Mumbai).

2 The major domestic record companies are: T-Series, Saregama, Zee Music Company, and Aditya Music. In addition, vertically integrated companies such as Yash Raj Films, Tips Industries Limited, and Eros International have their own film studios and record companies; a strategy being increasingly deployed by the domestic majors (Bhattacharya Citation2019).

3 The main digital distributors operating in India are local offices of international companies, notably Believe, CD Baby, Tunecore, and The Orchard (which is now owned by Sony Music Entertainment). They either charge a commission on the revenue earned by independent musicians from the streams of their songs, or they charge a fee for various services ranging from plain vanilla distribution to promotions, customer support, and analytics, or any combination thereof (Soundcharts Citation2022). MCNs operate on a similar business model but are largely involved with managing and monetising the YouTube channels of their clients. One Digital Entertainment is an example of a leading Indian MCN that manages the YouTube channels of independent record companies and celebrities including musicians (Vardhan Citation2015).

4 Just between these two sources we found nineteen independent record companies.

5 Indian Performing Right Society Ltd. v. Eastern Indian Motion Pictures Association, 1977, SCR (3) 206, 222.

6 The most subscribed to channel on YouTube in the world publishes Bollywood music and is operated by T-Series (Feeney Citation2022), the largest record company in India.

7 HSM is a term commonly used in media programming and advertising. As a noun it refers to a region – all of India without the five south Indian states, and as an adjective it describes an audience – all those who speak Hindi; but the two do not map perfectly since HSM audiences live outside the boundaries of the HSM region as well where they consume HSM content on pan-India media networks.

8 The IMI (Citation2022a, 11) report notes that 71% of their surveyed respondents preferred listening to local music as opposed to the global average of 49%.

9 See https://support.google.com/google-ads/answer/6333734 for the list of languages recognised and omitted by the Google Ads interface.

10 See https://support.google.com/adspolicy/answer/6088505 for the Google policy statement.

References

- Agrawal, Akshat. 2020. “Who Gets Paid for the Music You Listen To?: Revamping Music and Copyright in India (Part I).” SpicyIP, December 9. https://spicyip.com/2020/12/who-gets-paid-for-music-revamp-music-copyright-india-part1.html.

- Akundi, Sweta. 2020. “New Rules for Online Performances, Here’s Who Has to Pay Royalties.” The Hindu, July 27. https://www.thehindu.com/entertainment/music/new-directive-for-online-performances-by-iprs/article32203597.ece.

- Apple. 2003. “Apple Launches the iTunes Music Store.” Apple Newsroom, April 28. https://www.apple.com/newsroom/2003/04/28Apple-Launches-the-iTunes-Music-Store/.

- Apple. 2012. “Apple Launches iTunes Store in Russia, Turkey, India, South Africa & 52 Additional Countries Today.” Apple Newsroom, April 12. https://www.apple.com/uk/newsroom/2012/12/04Apple-Launches-iTunes-Store-in-Russia-Turkey-India-South-Africa-52-Additional-Countries-Today/.

- Arnaudo, Daniel. 2019. “Bridging the Deepest Digital Divides: A History and Survey of Digital Media in Myanmar.” In Global Digital Cultures: Perspectives from South Asia, edited by Aswin Punathambekar, and Sriram Mohan, 96–122. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Arya, Prakriti. 2019. “Here’s the Voice Cast for The Lion King’s Hindi & English Versions.” The Quint, July 16. https://www.thequint.com/entertainment/celebrities/complete-list-of-lion-king-voice-cast-hindi-english.

- Azzellini, Dario, Ian Greer, and Charles Umney. 2021. “Why Isn’t There an Uber for Live Music?: The Digitalisation of Intermediaries and the Limits of the Platform Economy.” New Technology, Work, and Employment, 1–23. doi:10.1111/ntwe.12213.

- Baghel, Sunil, and Anupam Dasgupta. 2017. “Deepdive: The Row over Money and Melody.” Mumbai Mirror, November 7. https://mumbaimirror.indiatimes.com/deepdive-the-row-over-money-and-melody/articleshow/61665873.cms.

- Bamzai, Kaveree. 2022. “The Rise of Hollywood.” Open, January 14. https://openthemagazine.com/cinema/the-rise-of-hollywood/.

- Baym, Nancy. 2018. Playing to the Crowd: Musicians, Audiences, and the Intimate Work of Connection. New York: New York University Press.

- Baym, Nancy, Rachel Bergmann, Raj Bhargava, Fernando Diaz, Tarleton Gillespie, David Hesmondhalgh, Elena Maris, and Christopher J Persaud. 2021. “Making Sense of Metrics in the Music Industries.” International Journal of Communication 15: 3418–3441. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/17635/3506.

- Beaster-Jones, Jayson. 2009. “Evergreens to Remixes: Hindi Film Songs and India’s Popular Music Heritage.” Ethnomusicology 53 (3): 425–448. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25653086. doi:10.2307/25653086

- Beaster-Jones, Jayson. 2017. “A.R. Rahman and the Aesthetic Transformation of Indian Film Scores.” South Asian Popular Culture 15 (2–3): 155–171. doi:10.1080/14746689.2017.1407551.

- Berry, Mike. 2019. “Neoliberalism and the Media.” In Media and Society, edited by James Curran, and David Hesmondhalgh, 6th ed. 57–82. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Bhardwaj, Tarun. 2021. “World Music Day 2021: Non-Film Music is not Subset of Bollywood, Says Vinit Thakkar, COO, Universal Music India.” Financial Express, June 21. https://www.financialexpress.com/entertainment/world-music-day-2021-non-film-music-is-not-subset-of-bollywood-says-vinit-thakkar-coo-universal-music-india/2275513/.

- Bhatia, Rahul. 2011. “The Quiet Royalties Heist.” Open, March 18. https://openthemagazine.com/art-culture/the-quiet-royalties-heist/.

- Bhatt, Shephali. 2018. “How Punjab Became Home to India’s Biggest Non-Film Music Industry.” The Economic Times, July 8. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/magazines/panache/how-punjab-became-home-to-indias-biggest-non-film-music-industry/articleshow/64898701.cms.

- Bhattacharya, Ananya. 2019. “Why a 118-Year-Old Bollywood Music Label Is Now Betting on Offbeat Films.” Quartz India, June 6. https://qz.com/india/1631997/after-t-series-saregama-indias-yoodlee-to-make-bollywood-films/.

- Biswas, Venkata Susmita. 2022. “Instagram Focuses on Scaling Ads on Reels in India.” Afaqs, July 15. https://www.afaqs.com/news/media/instagram-still-testing-the-waters-with-reels-ads.

- Booth, Gregory. 2015. “Copyright Law and the Changing Economic Value of Popular Music in India.” Ethnomusicology 59 (2): 262–287. doi:10.5406/ethnomusicology.59.2.0262.

- Booth, Gregory. 2017. “A Long Tail in the Digital Age: Music Commerce and the Mobile Platform in India.” Asian Music 48 (1): 85–113. doi:10.1353/amu.2017.0004.

- Business Insider India. 2021. “Josh, Moj, Roposo and Other Short Video Apps Lap up 97% of TikTok’s User Base in India.” Business Insider India, April 22. https://www.businessinsider.in/tech/apps/news/josh-moj-roposo-and-other-short-video-apps-lap-up-97-of-tiktoks-user-base-in-india/articleshow/82193942.cms.

- Cardozo, Elloit. 2021. “Hip Hop Goes to B-Town: Bollywood’s Assimilation of the Underground Aesthetic.” SRFTI Take One 2 (1): 26–43. http://srfti.ac.in/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/SRFTI-Take-One-May-2021.pdf.

- Chandran, Manju. 2021. “Why Great British Hero Bally Sagoo Stepped Back in Time.” EasternEye, February 17. https://www.easterneye.biz/why-great-british-hero-bally-sagoo-stepped-back-in-time/.

- Chhavi. 2013. “Airtel Completes 9 Years of its Hello Tune Service.” Telecom Talk, July 19. https://telecomtalk.info/airtel-completes-9-years-of-its-hello-tune-service/107420/.

- Ciochetto, Lynee. 2013. “Advertising and Marketing of Indian Cinema.” In Routledge Handbook of Indian Cinemas, edited by K. Gokulsing, and Wimal Dissanayake, 311–323. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203556054-24.

- Coulson, Susan. 2012. “Collaborating in a Competitive World: Musicians’ Working Lives and Understandings of Entrepreneurship.” Work, Employment and Society 26 (2): 246–261. doi:10.1177/0950017011432919.

- Cullity, Jocelyn. 2002. “The Global Desi: Cultural Nationalism on MTV India.” The Journal of Communication Inquiry 26 (4): 408–425. doi:10.1177/019685902236899.

- Das, Priyanjana Roy. 2016. “15 Famous Indian Musicians Who Started Their Careers as Ad Jingle Artists.” ScoopWhoop, January 6. https://www.scoopwhoop.com/music/famous-indian-musicians-who-started-as-ad-jingle-artists/.

- Das, Mohua. 2018. “Now, Bollywood’s Playback Singers Get Payback.” The Times of India, April 15. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/home/sunday-times/now-bollywoods-playback-singers-get-payback/articleshow/63765379.cms.

- Davison, Robert M, and Maris G Martinsons. 2016. “Context Is King!: Considering Particularism in Research Design and Reporting.” Journal of Information Technology 31 (3): 241–249. doi:10.1057/jit.2015.19.

- Deb, Mallika. 2018. “Independent Labels that are Game-Changers in the Music Industry.” Musicplus, February 20. https://www.musicplus.in/independent-labels-game-changers-music-industry/.

- Dredge, Stuart. 2021. “Gaana Narrows Losses, but its Revenue Growth has Slowed Down.” Music Ally, September 21. https://musically.com/2021/09/21/gaana-narrows-losses-but-its-revenue-growth-has-slowed-down/.

- Dredge, Stuart. 2022a. “Spotify has Doubled its Subscribers in India over the Last Year.” Music Ally, February 28. https://musically.com/2022/02/28/spotify-has-doubled-its-subscribers-in-india/.

- Dredge, Stuart. 2022b. “India’s ‘informal’ Music Industry: DJs, Indie Artists, Brass Bands … ” Music Ally, September 5. https://musically.com/2022/09/05/india-informal-music-industry-brass-bands/.

- Dredge, Stuart. 2022c. “India’s Short-Video Market Tipped to Reach $19bn by 2030.” Music Ally, September 8. https://musically.com/2022/09/08/indias-short-video-market-tipped-to-reach-19bn-by-2030/.

- Dredge, Stuart. 2023. “Indian Artists are Still Dominating YouTube’s Global Music Chart.” Music Ally, January 30. https://musically.com/2023/01/30/indian-artists-are-still-dominating-youtubes-global-music-chart/.

- The Economic Times. 2008. “YouTube Launched in India.” The Economic Times, May 7. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/tech/internet/youtube-launched-in-india/articleshow/3017907.cms.

- The Economic Times. 2017. “Gaana Launches Ability to Use App Interface in 9 Indian Languages.” The Economic Times, March 30. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/gaana-launches-ability-to-use-app-interface-in-9-indian-languages/articleshow/56251989.cms.

- The Economic Times. 2022. “Saregama India Share Price Today (03 Nov, 2022) - Saregama India Share Price Live NSE/BSE.” The Economic Times, November 3. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/saregama-india-ltd/stocks/companyid-13704.cms.

- Elbanna, Amany, and Ayomikun Idowu. 2022. “Crowdwork, Digital Liminality and the Enactment of Culturally Recognised Alternatives to Western Precarity: Beyond Epistemological Terra Nullius.” European Journal of Information Systems 31 (1): 128–144. doi:10.1080/0960085X.2021.1981779.

- Feeney, John. 2022. “The 10 Most-Subscribed YouTube Channels in the World.” Prestige Online - Singapore, February 19. https://www.prestigeonline.com/sg/pursuits/tech/the-most-subscribed-youtube-channels-in-the-world/.

- FICCI (Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce & Industry), and EY (Ernst & Young), India. 2019. A Billion Screens of Opportunity. India: Ernst & Young LLP.

- FICCI (Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce & Industry), and EY (Ernst & Young), India. 2022. Tuning Into Consumer. India: Ernst & Young Associates LLP.

- Galuszka, Patryk. 2015. “Music Aggregators and Intermediation of the Digital Music Market.” International Journal of Communication 9 (2015): 254–273. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/3113.

- Global Media Insight. 2022. “YouTube User Statistics 2022.” GMI, June 28. https://www.globalmediainsight.com/blog/youtube-users-statistics/.

- Gopinath, Sumanth. 2013. The Ringtone Dialectic: Economy and Cultural Form. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- Goyal, Samarth. 2020. “Lucky Ali: I Am Probably the Only Artist Who has not Been Paid Royalties by a Label.” Hindustan Times, June 16. https://www.hindustantimes.com/music/lucky-ali-i-am-probably-the-only-artist-who-has-not-been-paid-royalties-by-a-label/story-bc19Jxe6ZlrLqrhVO3HKAK.html.

- Gurbaxani, Amit. 2022a. “Who’s Making Money from Spotify?” LinkedIn, January 7. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/whos-making-money-from-spotify-shruti-thacker.

- Gurbaxani, Amit. 2022b. “India is Home to the Largest Number of YouTube Viewers in the World but the Platform’s Music Chart isn’t without Flaws.” Music Business Worldwide, September 2. https://www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/india-is-home-to-the-largest-number-of-youtube-viewers-in-the-world-but-the-platforms/.

- Hanrahan, Nancy Weiss. 2018. “Hearing the Contradictions: Aesthetic Experience, Music and Digitization.” Cultural Sociology 12 (3): 289–302. doi:10.1177/1749975518776517.

- Hattangadi, Sandeep. 2020. “Why are Hollywood Movies Gaining Popularity in India?” Free Press Journal, February 29. https://www.freepressjournal.in/entertainment/hollywood/why-are-hollywood-movies-gaining-popularity-in-india.

- Haynes, Jo, and Lee Marshall. 2018. “Reluctant Entrepreneurs: Musicians and Entrepreneurship in the ‘New’ Music Industry.” The British Journal of Sociology 69 (2): 459–482. doi:10.1111/1468-4446.12286.

- Herbert, Daniel, Amanda Lotz, and Aswin Punathambekar. 2020. Media Industry Studies. Cambridge: Polity.

- Hesmondhalgh, David. 2019. The Cultural Industries. 4th ed. London: SAGE Publications.

- Hesmondhalgh, David, Richard Osborne, Hyojung Sun, and Kenny Barr. 2021. Music Creators’ Earnings in the Digital Era. Newport: The Intellectual Property Office.

- The Hindu. 2018. “Playback Singers get Royalty for First Time.” The Hindu, April 13. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/tamil-nadu/playback-singers-get-royalty-for-first-time/article23531481.ece.

- Hindustan Times. 2019. “Salim Merchant claims YRF haven’t Paid Royalties for 4 Years, ‘I Know Javed Akhtar Sahab Has Not Been Paid.’” Hindustan Times, November 22. https://www.hindustantimes.com/music/salim-merchant-claims-yrf-haven-t-paid-royalties-for-4-years-i-know-javed-akhtar-sahab-has-not-been-paid/story-fv4dXnOIcbY5Rj2RzZrULO.html.

- Hoedemaekers, Casper. 2018. “Creative Work and Affect: Social, Political and Fantasmatic Dynamics in the Labour of Musicians.” Human Relations 71 (10): 1348–1370. doi:10.1177/0018726717741355.

- Hu, Cherie. 2017. “How India, the Global Music Industry’s Sleeping Giant, is Finally Waking Up.” Forbes, September 23. https://www.forbes.com/sites/cheriehu/2017/09/23/how-india-the-global-music-industrys-sleeping-giant-is-finally-waking-up/.

- IFPI (International Federation of the Phonographic Industry). 2021. “IFPI issues Global Music Report 2021.” IFPI, March 23. https://www.ifpi.org/ifpi-issues-annual-global-music-report-2021/.

- IMI (Indian Music Industry). 2022a. Digital Music Study-2021, Music: A Savior in Covid-19 Times. India: The Indian Music Industry.

- IMI (Indian Music Industry). 2022b. “India Trends 2021.” The Indian Music Industry. Accessed September 9 2022. https://indianmi.org/activities/india-trends/.

- Ithurbide, Christine. 2020. “Telecom and Technology Actors Repositioning Music Streaming.” In Platform Capitalism in India: Global Transformations in Media and Communication Research - a Palgrave and IAMCR Series, edited by Adrian Athique, and Vibodh Parthasarathi, 107–128. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Iyer, Siddharth. 2020. “The Jungle Book Hindi Cast and Where to Watch the Hindi Version Online.” Republic World, May 15. https://www.republicworld.com/entertainment-news/others/the-jungle-book-hindi-cast-irrfan-khan-om-puri-priyanka-chopra.html.

- Jacca. 2021. “The State of Indian Artists and Music Streaming in 2021.” RouteNote, October 29. https://routenote.com/blog/the-state-of-indian-artists-and-music-streaming-in-2021/.

- Jana, Reena. 2008. “From South Asia to iTunes.” Bloomberg UK, March 21. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2008-03-21/from-south-asia-to-itunesbusinessweek-business-news-stock-market-and-financial-advice.

- Jha, Lata. 2019. “Sony Music Ties up with Talent Firm KWAN for New Pop Label Big Bang Music.” Mint, August 1. https://www.livemint.com/industry/media/sony-music-ties-up-with-talent-firm-kwan-for-new-pop-label-big-bang-music-1564650479897.html.

- Jha, Lata. 2020. “Streaming of Audio Grows Nearly 40% in India in 2020.” Mint, December 15. https://www.livemint.com/news/india/audio-streaming-grows-40-in-india-in-2020-11608022882735.html.

- Jha, Lata. 2021. “IPRS, Radio Stations Spar over Royalty Payments.” Mint, February 24. https://www.livemint.com/news/india/iprs-radio-stations-at-loggerheads-over-royalty-payments-11614155730534.html.

- Jha, Lata. 2022a. “Labels, Artistes Tap Growing Demand for Non-Film Music.” Mint, April 20. https://www.livemint.com/industry/media/labels-artistes-tap-into-growing-demand-for-non-film-music-11650428801812.html.

- Jha, Lata. 2022b. “Audio Streaming Yearns for Subscription Manna.” Mint, June 23. https://www.livemint.com/industry/media/audio-streaming-yearns-for-subscription-manna-11655925035963.html.

- Jha, Subhash K. 2023. “Golden Globe Winner MM Keeravani: I Was Having a Difficult Time Speaking on the Stage.” The Times of India, January 13. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/entertainment/hindi/bollywood/news/golden-globe-winner-mm-keeravani-i-was-having-a-difficult-time-speaking-on-the-stage-exclusive/articleshow/96961904.cms.

- Jin, Dal Yong. 2015. Digital Platforms, Imperialism and Political Culture. New York: Routledge.

- Joshi, Aparna. 2011. “Interview with Mr. Javed Akhtar.” Soundbox 1 (7): 20–24. https://spicyip.com/docs/issue7_small%20pdf.pdf

- Kalra, Aditya, and Munsif Vengattil. 2022. “Fighting to Survive, Tencent-Backed Indian Music App Gaana Turns to Subscriptions.” Reuters, September 9. https://www.reuters.com/technology/exclusive-fighting-survive-tencent-backed-indian-music-app-gaana-turns-2022-09-09/.

- Keerthana, N. 2021. “Artists with Most Monthly Listeners on Spotify 2021, Which Artists have the Most Monthly Listeners on Spotify 2021?” Freshers Live, December 24. https://latestnews.fresherslive.com/articles/artists-with-most-monthly-listeners-on-spotify-which-artists-have-the-most-monthly-listeners-on-spotify-322537.

- Kharsynrap, Meghan. 2019. “Borrowing Tunes from Bollywood: Right or Wrong?” The Score Magazine 12 (7): 21. https://viewer.joomag.com/the-score-magazine-july-2019-issue/0116685001562321326.

- Kohli-Khandekar, Vanita. 2021. “Music & Film Bring in about Half of Our Business: T-Series’ Bhushan Kumar.” Business Standard, December 16. https://www.business-standard.com/article/companies/music-film-bring-in-half-half-of-our-business-t-series-bhushan-kumar-121121600021_1.html.

- Koimoi. 2022. “Arijit Singh Creates History Beating Taylor Swift Crossing 59 Million Followers, almost near to Cross Eminem in the List of Most Followed Artists on Spotify.” Koimoi, October 11. https://www.koimoi.com/bollywood-news/arijit-singh-creates-history-beating-taylor-swift-crossing-59-million-followers-almost-near-to-cross-eminem-in-the-list-of-most-followed-artists-on-spotify/.

- Kumar, Akshaya. 2017. “Item Number/Item Girl.” South Asia 40 (2): 338–341. doi:10.1080/00856401.2017.1295209.

- Lal, Kish. 2020. “How Bollywood Gave Us Hip-Hop’s Biggest Hits from Jay-Z, Travis Scott & More.” Cool Accidents, February 27. https://www.coolaccidents.com/news/how-bollywood-gave-us-hip-hops-biggest-hits.

- Lidhoo, Prerna. 2021. “How Spotify, despite entering the Audio OTT Space in India in 2019, became One of the Top Three Audio Streaming Services in the Country.” Fortune India, May 17. https://www.fortuneindia.com/technology/spotify-the-sound-of-streaming/105483.

- Lobato, Ramon, and Julian Thomas. 2015. The Informal Media Economy. Cambridge: Polity.

- Lorenzen, Mark, and Florian Arun Täube. 2008. “Breakout from Bollywood?: The Roles of Social Networks and Regulation in the Evolution of Indian Film Industry.” Journal of International Management 14 (3): 286–299. doi:10.1016/j.intman.2008.01.004.

- Loudest. 2022. “Indian Artist ‘King’ Rules Spotify Global Charts.” Loudest, November 25. https://loudest.in/news/indian-artist-king-rules-spotify-global-charts-15996.html.

- Manuel, Peter. 1993. Cassette Culture: Popular Music and Technology in North India. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Manuel, Peter. 2012. “Popular Music as Popular Expression in North India and the Bhojpuri Region, from Cassette Culture to VCD Culture.” South Asian Popular Culture 10 (3): 223–236. doi:10.1080/14746689.2012.706012.

- Manuel, Peter. 2014. “The Regional North Indian Popular Music Industry in 2014: From Cassette Culture to Cyberculture.” Popular Music 33 (3): 389–412. doi:10.1017/S0261143014000592.

- Marshall, Lee. 2015. “‘Let’s Keep Music Special. F-Spotify’: On-Demand Streaming and the Controversy Over Artist Royalties.” Creative Industries Journal 8 (2): 177–189. doi:10.1080/17510694.2015.1096618.

- Mohan, Sriram, and Aswin Punathambekar. 2019. “Localizing YouTube: Language, Cultural Regions, and Digital Platforms.” International Journal of Cultural Studies 22 (3): 317–333. doi:10.1177/1367877918794681.

- Morris, Jeremy Wade. 2020. “Music Platforms and the Optimization of Culture.” Social Media + Society 6 (3): 1–10. doi:10.1177/205630512094069.

- Mukherjee, Rahul. 2019. “Imagining Cellular India: The Popular, the Infrastructural, and the National.” In Global Digital Cultures: Perspectives from South Asia, edited by Aswin Punathambekar, and Sriram Mohan, 76–95. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Nair, Gayatri. 2022. “‘New’ Terrains of Precarity – Gig Work in India.” Contemporary South Asia 30 (3): 388–401. doi:10.1080/09584935.2022.2099813.

- Nair, Adityan, and Subir Malik. 2020. “Sunday Debate: Can Independent Musicians Make Money?” Hindustan Times, September 27. https://www.hindustantimes.com/brunch/sunday-debate-can-independent-musicians-make-money/story-f9tVPrzhUejPNkBrVhfUuJ.html.

- Negus, Keith. 2015. “Digital Divisions and the Changing Cultures of the Music Industries (or, the Ironies of the Artefact and Invisibility).” Journal of Business Anthropology 4 (1): 151–157. doi:10.22439/jba.v4i1.4793.

- Nieborg, David B, Brooke Erin Duffy, and Thomas Poell. 2020. “Studying Platforms and Cultural Production: Methods, Institutions, and Practices.” Social Media + Society 6 (3): 1–7. doi:10.1177/2056305120943273.

- Nieborg, David B, and Thomas Poell. 2018. “The Platformization of Cultural Production: Theorizing the Contingent Cultural Commodity.” New Media & Society 20 (11): 4275–4292. doi:10.1177/1461444818769694.

- Nowak, Florence. 2014. “Challenging Opportunities: When Indian Regional Music Gets Online.” First Monday 19 (10), doi:10.5210/fm.v19i10.5547.

- Nowak, Florence. 2018. “Indian Regional Music Videos as Dreamcatchers in the Attention Economy.” Volume! 14 (2): 161–173. doi:10.4000/volume.5578.

- Nowak, Raphaël, and Benjamin A. Morgan. 2022. “New Model, Same Old Stories?: Reproducing Narratives of Democratization in Music Streaming Debates.” In Music and Democracy: Participatory Approaches, edited by Marko Kölbl, and Fritz Trümpi, 61–84. Wien: mdwPress. doi:10.1515/9783839456576-003.

- O’Brien, Chris. 2015. “India’s Music-Streaming Leader Saavn Raises $100M, Adding 1M Users Each Month.” VentureBeat, July 7. https://venturebeat.com/business/indias-music-streaming-leader-saavn-raises-100m-adding-1m-users-each-month/.

- Outlook. 2023. “Diljit Dosanjh to Perform alongside Blackpink, Bad Bunny, Bjork at Coachella 2023.” Outlook, January 12. https://www.outlookindia.com/art-entertainment/diljit-dosanjh-to-perform-alongside-blackpink-bad-bunny-bjork-at-coachella-2023-news-253079.

- Plantin, Jean-Christophe, Carl Lagoze, Paul N Edwards, and Christian Sandvig. 2018. “Infrastructure Studies Meet Platform Studies in the Age of Google and Facebook.” New Media & Society 20 (1): 293–310. doi:10.1177/1461444816661553.

- Prey, Robert. 2020a. “Locating Power in Platformization: Music Streaming Playlists and Curatorial Power.” Social Media + Society 6 (2): 1–11. doi:10.1177/2056305120933291.

- Prey, Robert. 2020b. “Performing Numbers: Musicians and Their Metrics.” In The Performance Complex: Competition and Competitions in Social Life, edited by David Stark, 241–258. Oxford: Oxford University Press.