Abstract

Personal initiative is an important behavior relevant to future workplaces that will require significant self-reliance. In research on self-initiated expatriates (SIE), it is assumed that those who move to another country and a new job show ‘initiative’ and yet it has received insufficient attention in empirical publications. We highlight the degree to which personal initiative shown by SIEs is context-dependent and conclude that it is untenable to attribute to all SIEs a homogeneous work behavior in terms of personal initiative. To improve the fast-growing SIE research, we incorporate a theory of personal initiative and advocate for, and give suggestions on how to measure initiative. We also, offer an initial model of how personal initiative will improve SIE outcomes. By offering specific guidance for future research, we seek to enhance the meaningfulness of future studies and thus increase their utility for organizations and policymakers alike. We conclude by expressing the importance of this conceptualization in practice.

Introduction

For a variety of reasons, employees that demonstrate personal initiative are increasingly important for organizations. Expatriation represents an interesting case, because relocating abroad independently is likely to require a comparatively high level of personal initiative. By definition, ‘self-initiated’ expatriates (SIEs) are assumed to show personal initiative when relocating abroad (e.g., Andresen, Bergdolt, Dickmann, & Margenfeld, Citation2014; Cerdin & Selmer, Citation2014; Tharenou, Citation2015). Self-initiated international mobility is described as a choice (Doherty, Dickmann, & Mills, Citation2011; Hussain & Deery, Citation2018) made by individuals who decide on their own to go abroad (Dorsch, Suutari, & Brewster, Citation2013). Without organizational assistance (Begley, Collings, & Scullion, Citation2008), they self-arrange new employment overseas (Cerdin & Selmer, Citation2014). Thus, per definition SIE need initiative and a desire to move in a foreign country (Andresen & Margenfeld, Citation2015). Despite the centrality of initiative in the definition of SIEs, ‘initiative’ is usually neither measured nor are differences in the level of SIEs’ initiative discussed in SIE research. Only a handful of definitions of SIEs explicitly address criteria for defining and evaluating initiative (e.g., Selmer, Andresen, & Cerdin, Citation2017). Moreover, the assumption that SIEs show initiative has received scant attention in the empirical SIE literature, although employees with high initiative are sought by employers (Frese & Fay, Citation2015). The research aim of this paper is twofold, we want to make the case that SIEs cannot generally be expected to have a high level of initiative, as the required initiative associated with their international relocation varies greatly depending on the context. We also outline approaches for defining, measuring and researching initiative in the SIE context to advance further research.

Our essay contributes to the expatriation literature in four ways. First, we provide a conceptual basis for ‘initiative’ that is a key element of the concept of self-initiated expatriation. Second, we address this lack of clarity surrounding initiative by incorporating personal initiative theory (Fay & Frese, Citation2000) into SIE research that helps to refine the numerous SIE definitions, reduce the ambiguity around SIEs. Third, by examining sampling issues associated with research into SIEs, we seek to enhance the validity of future research by removing inconsistencies in our knowledge base and thus increasing the utility of the empirical evidence for organizations and policymakers alike. Measuring SIEs’ personal initiative and understanding the heterogeneity in the initiative level among the group of SIEs is a prerequisite for empirically analyzing its impact on relevant outcomes. We give guidance on how personal initiative can be measured and tested on SIE outcomes. Fourth, we show the value of these expatriates for employers. Personal initiative is increasingly an important characteristic of the future workforce. By incorporating personal initiative theory into empirical SIE investigations, researchers will be able to identify the selection value of this pool of workers.

We begin this essay by presenting a conceptualization of personal initiative. We describe the methods and explain the steps we took to run the conceptual analysis. These include a review of the theory of personal initiative as a foundation for the analysis and an outline of the constituents of initiative that we apply to the context of SIEs as well as a conceptual analysis with reference to empirical studies in the field of self-initiated expatriation. Next, we provide specific recommendations for future empirical research on how to measure personal initiative in the SIE context as well as provide an initial research model. Finally, we discuss the conceptual contributions of this paper and derive implications for practice.

Conceptualization of personal initiative

To reach our research aim, we first run a conceptual analysis that takes two steps in line with its methodological requirements. In step 1, we elucidate the complex concept of self-initiation by breaking it up into its simpler and more comprehensible constituent components, explain the meaning of each term in its definition, and apply it to the case of self-initiated expatriation (Beaney, Citation2017; Olsthoorn, Citation2017). In step two, we look into the matter of the content of the linguistic expression, that is, what researchers claim to be thinking and talking about when we refer to expatriates’ initiative (Bassham, Irwin, Nardone, & Wallace, Citation2008; Petocz & Newbery, Citation2010). The goal of this second step is to logically analyze personal initiatives’ meaning in SIE research by identifying and specifying the contexts in which the phenomenon of initiative matters (Furner, Citation2004).

Theory of personal initiative

A definition of SIE still has not solidified and borrowing from personal initiative literature can strengthen SIE research. SIE literature can greatly benefit from the past two decades of personal initiative research. In this vein, we refer to the theory of personal initiative, and apply it within the SIE context. When different research streams cross-pollinate, investigators can advance research agendas and theory. Personal initiative theory was developed to help explain motivation at work (Fay & Frese, Citation2000).

Personal initiative is conceptualized as work behavior with three constituent components including self-starting, proactivity and persistence, that has been broadly researched and validated (e.g., Bledow & Frese, Citation2009). According to Frese and Fay (Citation2001, p. 151), self-starting behavior relates to the degree to which psychological distance must be overcome by doing ‘things that are difficult to do and go beyond what is typically done’. A person, without prompting, chooses to pursue a goal on their own is an example of self-starting (Fay & Frese, Citation2000). Proactivity is anticipating future hurdles, problems and issues and taking action to ensure the goal is accomplished before challenges arise (Frese & Fay, Citation2001). Individuals who act proactively do not wait to respond but instead solicit feedback and look for opportunities. Persistence is behavior that is needed for long-term goal accomplishment (Fay & Frese, Citation2000). An individual may change a strategy or set new goals that create unintended problems, difficulties or challenges that will need to be overcome. If they persist, then they will be more likely to achieve the desired outcome (Frese & Fay, Citation2001). Each facet of personal initiative follows an action sequence consisting of four steps as summarized and adapted to SIEs in . Individuals set goals and seek information that they then use to develop their plan. They then monitor the actions they take to execute their plan and gather feedback to adjust their actions (Frese & Fay, Citation2001).

Table 1. Characteristics of ‘personal initiative’ in the expatriation context (based on Frese & Fay, Citation2001).

The three components represent different avenues to personal initiative. As formative (or causal) indicators of the respondents’ level of personal initiative (Bledow & Frese, Citation2009), the overall strength of personal initiative is higher when more personal initiative components are reflected in a person’s actions (Frese & Fay, Citation2001). The three co-occurring components reinforce each other (Frese, Fay, Hilburger, Leng, & Tag, Citation1997; Frese & Fay, Citation2001). For example, higher proactive behavior, in turn, is related to being more self-starting because an individual wants to exploit future opportunities that others do not yet see. While every individual’s level of personal initiative is based on work behaviors in the three areas, the actions vary in the degree to which they possess personal initiative. Bledow and Frese (Citation2009, p. 232) explain that ‘Actions high in personal initiative are self-starting, proactive, and overcome barriers. Features of actions low in personal initiative are taking the conventional path, accepting the status quo, and managing one’s emotions rather than changing the situation’ (Frese & Fay, Citation2001). The overall score is a composite measure of how frequently respondents report situated preferences for high initiative behaviors in the three areas. Thus, persons differ with respect to the level of their personal initiative in their work behavior and the concept allows for a differentiation between high- and low-initiative respondents (Bledow & Frese, Citation2009).

Bledow and Frese (Citation2009) regard personal initiative as situated action. Because of the interrelationship between personal initiative and its context in which it occurs, the specific situational context with its constraints and affordances is important for what people do. Depending on the concrete situation, individuals show varying levels of initiative. Differences between situations relate, for example, to the kind of competencies that are needed to show initiative and that individuals possess to different levels (Wihler, Blickle, Parker Ellen, Hochwarter, & Ferris, Citation2014).

Application of the concept to self-initiated expatriation

Showing personal initiative when relocating abroad means that SIEs have a self-starting and proactive approach and are persistent in overcoming barriers as well as setbacks to achieve their goal of working abroad. Many of the defining characteristics of personal initiative set out in are individual-level variables. None of these are explicitly measured in any study involving SIEs1. However, in some cases, we can deduce them from the context. This is particularly true for the psychological distance that needs to be overcome, which is an indicator of self-starting behavior, and the need to overcome institutional barriers, which requires persistence. While all kinds of employees, internationally mobile or not, show personal initiative to a certain extent, we assume that SIEs are likely to typically show more actions that are high in personal initiative and in more components of personal initiative as compared to other employees. Suutari and Brewster (Citation2000) argued that the SIEs’ overall level of personal initiative can be expected to be higher as compared to assigned expatriates (AE).

Being a self-starter

Self-starting behavior of SIEs implies that their international relocation is difficult to realize and goes beyond what is typically done. The goal to relocate internationally and large psychological distances are likely to be stronger for SIEs than is for AEs. Many SIEs do not just follow the example of many other expatriates and take the prescribed or conventional path in their work or private lives. Instead, they tend to take initiative in going beyond what is formally required, expected or usual for the job, career or industry concerned (Fay & Frese, Citation2001). In contrast to using standard procedures, SIEs are likely to take it upon themselves to collect information on what can be done and how to select a destination country, seek an adequate job, convince employers of their qualifications, obtain a work permit, and manage the logistics of moving abroad. AEs, by contrast, are likely to show less self-starting behavior, since their international assignments are prescribed in more detail and individuals follow a conventional career path and are coached through the relocation process by their employers (Howe-Walsh & Schyns, Citation2010). Therefore, SIEs that are self-starters seek out the opportunity to work overseas.

Being proactive

Proactive SIEs do not wait until they are forced to respond to a new situation. Instead, they have a long-term focus that enables them to anticipate things to come, such as new job demands or opportunities, and to address them. Proactivity implies that SIEs develop back-up plans in case something does not work out as expected (cf. Fay & Frese, Citation2000). They may anticipate challenges in language and culture and address it by learning the language and studying the culture before arrival. This behavior involves challenging the status quo in one’s employment and private life to improve or change one’s current personal or professional situation, as well as developing personal resources for meeting future work and personal demands (Bolino & Turnley, Citation2005). Therefore, SIEs that are proactive anticipate and plan for the challenges they face in overseas employment.

Being persistent

Persistence helps to overcome barriers and serves to protect the SIE’s goal from being abandoned and it is important for SIEs to manage the challenges of international relocation that often involve setbacks and failure. Expatriates must convince themselves that it is worth continuing with their international relocation plan even if it is not immediately successful. Moreover, people, especially family members, affected by the international relocation may struggle to adapt to the new circumstances (Davies, Froese, & Kraeh, Citation2015; Yamazaki, Citation2010). This requires persistence from SIEs to surmount technical barriers and to overcome the resistance and inertia of their families. The first employment application strategy might fail to lead to employment abroad. They persist and may even change professions in order to secure income (Begley et al., Citation2008). Therefore, SIEs that are persistent overcome the challenges of overseas employment.

SIEs’ level of initiative in context

Personal initiative is an example of situated action and as such, domain-specific. It is usually situated in the work setting. When the overall level of personal initiative is higher, the more of the personal initiative facets are reflected in an SIE’s actions and the more actions high in personal initiative are shown. The evaluation of personal initiative depends on the situation, as we will now argue. We expect that the level of personal initiative varies widely within the group of SIEs due to contextual factors and there are many context factors to choose from. However, we chose three context factors—profession, home country and host country—for two reasons. First, many of the SIE studies list these three factors in their methods section (Doherty, Citation2013). Therefore, using these as examples is more meaningful to researchers. Second, researchers are concerned with the contextually embedded nature of the SIEs’ professional development. When relocating abroad SIEs do not only need to get familiar with a different country culture, but accommodate with local professional norms. Thus, SIEs need to identify with and develop simultaneous membership in several cultural groups at the national and professional levels (Sackmann & Phillips, Citation2004). As SIEs typically cannot rely on organizational support by their employer during their relocation, they need to take initiative themselves to navigate and manage in this multicultural environment.

Profession

Self-starting

Professions can be located along a continuum from high to low in terms of the psychological distance that needs to be overcome when engaging in self-initiated international mobility. We employ the examples of academics and lawyers to illustrate how their position toward opposite ends of this continuum is determined. Taking a comparative look, we can observe that these professions differ considerably regarding the degree of psychological distance individuals must overcome and thus the amount of self-starting behavior required. It is comparatively low for academics, but high for lawyers.

The international mobility of academics is encouraged by national governments and supranational institutions and facilitated by a host of funding bodies (Bauder, Citation2015; Teichler, Citation2015). Mobility is normal in academic environments and is seen as acceptable to move between universities (Morano-Foadi, Citation2005). Academics tend to be encouraged by accruing standing and improving reputation in the field, thus accumulating social and cultural capital (Bauder, Citation2015, p. 85). With the international mobility of academics being an accepted convention, the psychological distance for internationally mobile academics is considered low.

The legal profession, by contrast, ‘is specifically targeted to and based on the national legal systems in which prospective lawyers train and fully qualified lawyers practice’, and this leads to a situation where lawyers may fulfill similar tasks and functions, but where ‘their substantive knowledge differs considerably from state to state’, in a fashion Panteia (Citation2012, p. 15) considers ‘atypical of other (.) professions’. Such differences in substantive knowledge manifest themselves in several considerable institutional barriers to international mobility. According to multiple studies almost all lawyers practice in the country in which they had been trained (Panteia, Citation2012; Silver, De Bruin Phelan & Rabinowitz, Citation2009). Taking all this evidence together, we can conclude that moving internationally is ‘difficult to do’ for a lawyer and goes considerably ‘beyond what is typically done’. In other words, it requires considerable self-starting behavior, as a large psychological distance must be overcome.

Proactivity

In continuing our contrast between academics and lawyers, proactivity is more prevalent in the circumstances of the legal profession when compared to the academic profession. Specifically, lawyers considering a move must also consider how to become certified to practice law in another country. This will involve problem solving behavior and strategic planning to anticipate the challenges. Not only do lawyers have to learn a new set of laws, but they will have to learn new cultural customs related to employment. In this situation, lawyers may take proactive action, such as seeking mentors, finding study guides and seek organizations that will be flexible until the lawyer is qualified to practice law.

Alternatively, academics will need some level of proactivity but the path before them is much easier. Because mobility is a key component to this profession (e.g., Bauder, Citation2015) academic turnover is a normal occurrence. Again, the core functions of the job (research, teaching) generally stay the same, especially if one is moving up in international standing. While lawyers moving countries is rare, academics moving is relatively common and therefore there are typical support practices in place for academics which decreases the need for proactivity.

Persistence

Persistence is especially needed to overcome institutional barriers, is again acutely needed by lawyers. Access to the legal profession is strictly controlled by nations and involves lengthy qualifying periods and requirements to sit additional examinations or to work in conjunction with local lawyers in court proceedings (Panteia, Citation2012; Silver et al., Citation2009). Thus, lawyers who strive to be internationally mobile must demonstrate a very high level of persistence. Depending on the host country, it can take years to be certified because the lawyer may have gone through the entire education cycle before approval to practice law. As academics do not need a license to practice, their need for persistence is arguably lower. Instead academics are expected to continue research on the same topic or area. Furthermore, they are typically asked to teach the same or similar classes regardless of the geographic location.

Home country

Self-starting

Asking whether an individual ‘goes beyond what is typically done’ leads us to looking at how common it is for people to leave their home country and how this is regarded by other members of the respective home societies. In a study of New Zealanders; for example, over 50% of the respondents had experienced ‘a prolonged period of travel, work, and tourism’ (Inkson, Arthur, Pringle, & Barry, Citation1997, p. 358). Similarly, 17.5% of the 15 years or older sample population born in Ireland were living overseas (Arslan et al., Citation2014). It seems fair to conclude that leaving one’s home country does not tend to be regarded as out of the ordinary in countries where half of the young people seek international exposure or where more than 1 in 10 live abroad. Consequently, for New Zealanders or the Irish, the psychological distance to be overcome and thus the need for self-starting behavior in self-expatriating can be considered low.

In contrast, the proportion of Japanese-born people living abroad during the same time period (2010–11) was a mere 0.6% (Arslan et al., Citation2014). Japan has often been characterized as a very homogeneous society that pressures returnees to conform and tends to discriminate against those that are in any form ‘different’ (Sugimoto, Citation2014; Yoshida et al., Citation2009). The expatriate experience changes people and these changes may not be well received when people return to their home societies. The re-integration challenges of Japanese returnees have been well documented (Yoshida et al., Citation2003). Similarly, reporting on the repatriation experiences of Mackintosh (Citation2001) concluded that leaving the home country tended not to be well received in Denmark and aggravated their re-integration. If self-initiated expatriation is unwelcome or puts people in a very small minority of the population and makes significant re-integration challenges upon repatriation likely, we may conclude that individuals from these countries ‘do things that are difficult to do and go beyond what is typically done’. The psychological distance that needs to be overcome is larger for Danish or Japanese than for New Zealander or Irish SIEs and hence more self-starting behavior is required.

Proactivity

If born in New Zealand or Ireland, becoming an SIE presents fewer hurdles and challenges than leaving Japan. Ireland in particular is simple for SIEs because it is a member of the EU so traveling to the rest of Europe is straightforward. Employment laws in Europe are also accommodating to Irish nationals. Similarly, New Zealanders will have a relatively easy time becoming an SIE. Members from both countries will likely have established communities they can join when they arrive to their host country. Because of the factors, Irish and New Zealanders have less need to anticipate issues and challenges. In contrast, very few Japanese live outside of the country (0.6%). While the small population breakdown is not very well known, we can assume that many of the employed Japanese living outside the country are AEs representing Japanese firms. However, for those Japanese who do become SIEs, we can assume they have high levels of proactivity, because they will have to shun custom and create their own path. In one recent study, Japanese SIEs when compared to Japanese AEs in China were more successful at building trust with not only the Chinese employees but also with the AEs and the Japanese employees in the homeland (Furusawa & Brewster, Citation2018).

Persistence

There is appreciably less persistence needed for SIEs from Ireland or New Zealand when compared to Japan. While there are always hurdles and challenges to overcome for all SIEs, Irish and New Zealanders have a well-worn path to follow. Such a high percent of the population regularly works overseas that there is cultural knowledge in traveling overseas. Japanese SIEs are having to figure out how to find another job in another country on their own. While Irish and New Zealanders speak English where the likelihood of being able to communicate in their native tongue is more likely, Japanese SIEs will almost always have to learn a second language that is far more distant than their native language. While expatriate communities may be large where Japanese SIEs relocate themselves, there were likely be very few Japanese expatriates to help them adjust the new country. The degree of isolation that these hurdles present to indicate that a Japanese expatriate will have to have more persistence to be successful.

Host country

Self-starting

Looking at the receiving country, we once more note marked differences in how common foreigners are in the host society and hence to what degree expatriation to that country ‘goes beyond what is typically done’. In 2018, the proportion of non-nationals in the total population was 90% in the UAE, 88.4% in Qatar and 31.4% in Saudi Arabia (World Population Review, Citation2019). The share of foreign-born people in total employment exceeded 20% in Switzerland, Australia or New Zealand in 2017, but was miniscule in Japan, Korea and Poland (OECD, Citation2018). Thus, moving to the UAE would not seem atypical for an SIE as expatriates account for most of the population there. The psychological distance and the need for self-starting behavior can be considered fairly low. Moving as an SIE to Japan, Korea or Poland could be considered a very unusual step indeed with a correspondingly high need for self-starting behavior (see Belot & Ederveen, Citation2012).

Apart from the cultural diversity, including the sizes or shares of cultural groups in the destination community, for example, differences in values and norms, language and religion between the home and host country, or the between-group cultural distance within the destination community determine the level of self-starting behavior that is needed (see Belot & Ederveen, Citation2012; Wang, De Graaff, & Nijkamp, Citation2016). Differences in community culture translate into migration costs that are likely to reduce the attractiveness of self-initiated expatriation. Studies show that expatriation flows to a geographical area with low distance between languages and culture are significantly larger (Belot & Ederveen, Citation2012). Moreover, results suggest that while cultural diversity increases regional attractiveness, individuals were particularly reluctant to accept moves to regions with high average cultural distance between the residing cultural groups (see Belot & Ederveen, Citation2012; Wang et al., Citation2016).

Proactivity

Moving to a host country that has few foreigners is akin to an explorer entering the unknown. There may be broad generalizations that SIEs can use to prepare for the trip but they will lack specifics on how to manage day-to-day life, cultural details, and even basic professional standards. The fear of the unknown will likely drive proactivity in SIEs to prepare. Because of the unknown, SIEs must be proactive and prepare for unexpected contingencies and will plan for not having any support upon arrival as it is unlikely to find other expatriates that may ease the transition for them. Unlike AEs who may be afforded an opportunity to visit the country prior to the relocation, SIEs arrive in the country for the first time. In less developed nations it may be difficult to prearrange housing. In countries with few foreigners, SIEs are easily identifiable whereas in countries with many foreigners, SIEs can blend in and cultural mistakes are more likely to be written off. SIEs traveling to a country with many expatriates (e.g., UAE) will not have to be as proactive. There are entire websites dedicated to expatriates who are considering moving to the host country. They can learn what to expect and to do to be successful. Upon arrival, SIEs can seek out members and networks from their home country and receive the critical support that may aid in their adjustment.

Persistence

Host countries vary greatly in ways of accepting foreign workers. SIEs may have fewer options than AEs of countries to move to because some prefer employment before admittance into the country. Institutional barriers requiring persistence manifest themselves primarily in requirements for residence and work permits, as well as governmental restrictions on the number of migrants (Ceric & Crawford, Citation2016). Most immigration systems differentiate between applicants based on occupation, age, or citizenship. SIEs that attempt to move to a nation that encourages foreign workers (e.g., UAE) require less persistence than ones who create high barriers for foreign workers. With high barriers, SIEs may have to apply more than once and make changes in order to meet the entry requirements.

Once in the host countries, nations that are receptive to foreign workers will require less persistence. Finding a job (if not already acquired) will be straightforward and will follow basic employment supply and demand. If employers have openings and SIEs have the requisite skills employment will follow. In host countries that are not receptive to foreign workers, SIEs may have a more difficult time finding employment. One strategy to circumventing difficult worker visas is to enter the country on the false premises of being a vacationer. The goal of SIEs is to find an employer that will see enough value in them that they are willing to go through the time consuming and expensive process of hiring a foreign worker. Before that occurs, SIEs may have to acquire employment illegally or change professions to financially sustain themselves prior to legal employment. This may take years and will require persistence and fortitude. Although, even in less rigid employment environments, SIEs paving a path for future other foreigners will have significant barriers that they will have to overcome. They may have to take a job that is under their skills and ability because of discrimination, the novelty of hiring a foreign worker, or just because the situation favors employers.

Translating the new conceptualization to empirical research

Although the definition of SIEs suggests a comparatively high initiative, our conceptual analysis suggests that the level of personal initiative varies widely within the group of SIEs. Therefore, SIEs’ personal initiative cannot be taken for granted—neither by companies interested, for example, in recruiting employees with a high level of initiative, nor by researchers. Consequently, SIEs’ personal initiative needs to be measured and analyzed in empirical research. To reach the second part of our research aim, in this section, we will discuss operationalization of personal initiative. We will then address how to manage the contextual factors. Finally, we will offer initial research questions that can be tested.

Operationalization of personal initiative

To date, there is no measure of personal initiative specifically for SIE research. There are indirect ways of measuring personal initiative that researchers could use. At a minimum, researchers deploying survey instruments could utilize the validated 7-item scale of personal self-reported initiative established by Frese et al. (Citation1997). Sample items include ‘I actively attack problems’ or ‘Usually I do more than I am asked to do’. This will allow investigators to determine if there are differences in personal initiative between SIEs and AEs. Ultimately, the difference in general personal initiative may explain some of the behaviors of expatriates. There are other scales that could be used to measure personal initiative that are based on psychological traits such as the proactive personality scale (Bateman & Crant, Citation1993) or the persistence sub scale from the Tridimensional Personality Questionnaire (Cloninger, Przybeck, & Svrakic, Citation1991). It is logical that there is a positive relationship between personal initiative and proactive personality and (psychological) persistence. However, there are limitations of using the general personal initiative measure and other psychological-based scales.

The general personal initiative scale does not determine if the SIEs’ personal initiative is what drove them to expatriate. While expatriates may have high levels of general personal initiative, a natural disaster may be what drives them out of their home country. Personal initiative is regarded as a situated action (Bledow & Frese, Citation2009), so it may not be appropriate to measure general psychological traits. For example, by using a more indirect and situated measure, the measurement of personal initiative can be improved. SIEs would be confronted with different relocation-related critical incidents and asked to report their preferences for specific actions that vary in the degree to which they are high or low in personal initiative (cf. Bledow & Frese, Citation2009). We present how to more accurately measure the three components of personal initiative in SIE research below.

outlines some typical behaviors related to international relocation along the action sequence described by Frese and Fay (Citation2001). First, initiating behavior implies that SIEs are guided by their own goals to gain international work experience that is not obligatory for their career, but useful to advance personal chances (e.g., nurse). Second, SIEs actively seek information about job and housing opportunities, and freely explore job offers. Third, in the planning phase (how to acquire employment abroad given their resource constraints) SIEs take on a lot of responsibilities and considering long-term future issues. Fourth, they monitor the execution and take an active feedback approach by asking other SIEs and foreign nationals.

Table 2. Examples of SIE self-starting behavior, proactivity and persistence.

Towards measuring self-starting

Self-starting implies that an individual develops and pursues the self-set goal to relocate internationally without having been explicitly told to do so: the impetus for the action comes from the person. An international relocation represents a self-starting behavior, if it is an unusual step, at least for the specific career and its context such as the profession or countries in question, difficult to realize and, thus, implies a high psychological distance (cf. Fay & Frese, Citation2000).

To identify whether the international relocation represents a self-starting behavior, the following questions can be embedded in assessment centers and in situational interviews (for analogous approaches, see Fay & Frese, Citation2001). One approach is to ask direct questions on past initiative, for example, ‘Did you relocate internationally and apply for a job abroad?’ The interviewers can then probe into the nature of the relocation by asking whether this goal had been developed deliberately by the expatriate or by other people and whether the relocation is executed without external order or demand. Moreover, the interviewers can ask whether the international relocation was often discussed or executed by colleagues in the same profession and country to understand the ‘psychological distance’ involved. The raters can then code the relocation behavior on whether it required to go beyond expected behavior in this career.

As these questions rely on past events, they risk to be affected by memory effects. To overcome this disadvantage, it is better to focus on present behavior such as interviewees’ present international relocation or future plans to do so, that can reliably be measured within the interview. Only present behavior that is not triggered by demands from the company, spouse or other external pressures counts as self-starting. Using , the coding is based on what the interviewees indicate in terms of the four aspects along the action plan and the three components of initiative.

The self-starting behavior can be motivated by both intrinsic and extrinsic aspects (Fay & Frese, Citation2000). Howe-Walsh and Schyns (Citation2010) distinguish between ‘private SIEs’ (those moving for personal reasons, such as to ‘see the world’, learn a new language, partnership abroad, escaping their home country and wanting to start over) and ‘career SIEs’ (those moving for job-related reasons). If Howe-Walsh and Schyns (Citation2010, p. 266) are correct that ‘private SIEs’ are often ‘already (…) familiar with the country’s culture’ and may be ‘willing to accept a position that has a low fit with their prior work experience’, this has profound implications for the level of self-starting behavior required. Familiarity with the host country will lower psychological distance. Similarly, SIEs that are forced out of their home country, with reasons including an active war, discrimination, natural disasters, economic hardship, political reasons and the current home country situation escalates to a point where this group of SIEs can no longer tolerate living in their home country, are not categorized as self-starters, because their relocation is triggered by external pressures. It is also highly relevant that numerous studies find that those we currently study as SIEs move primarily not for work-related reasons (e.g., Doherty et al., Citation2011; Richardson & McKenna, Citation2002; Thorn, Citation2009).

Towards measuring proactivity

While researchers have inadvertently researched self-starting behavior by looking into the reasons why SIEs leave, there is little research on the SIEs’ proactivity (as exceptions see Guo, Porschitz, & Alves, Citation2013; Tharenou, Citation2010). The key to proactivity is anticipating and planning for the future—before leaving and upon arrival in the host country. There are many scenarios to consider before departing. Proactive SIE behavior will greatly aid success because expatriates will be able to avoid some of the common mistakes and make better decisions. Being proactive upon arrival will help develop a strong support group that will help with adjustment. While this list in is not designed to be exhaustive these are common ways for SIEs to be proactive. Not every SIE will be able to fully prepare or anticipate every scenario before leaving; however, they will be able to mitigate some of the risks and deflate some of the adaptation pain that they might experience when trying to adapt to a new country.

Towards measuring persistence

Persistence is going to be the hardest to measure for a number of reasons. First, there will be a general selection bias. Many of the SIEs with low persistence may quit and return home. The expatriate adjustment research generally concludes that after a period of time the challenges ease and the desire to leave drops off significantly (Fu, Hsu, Shaffer, & Ren, Citation2017). There might be an opportunity to longitudinally measure SIEs before they depart to the host country and follow them through their expatriation so that those with low persistence can be identified and their behaviors recorded. Any future research that measures persistence should try to target failed or short-term SIEs to have a more complete picture. Second, participants may remember the challenges they faced incorrectly has harder or easier than reality.

There are a number of ways to determine the persistence of an SIE including survey methodology. One way would be to develop a scale that tries to determine how they persisted in general with the challenges of any expatriation. Another way would be to ask about specific common challenges that expatriates face like listed in . Persistence may also lend itself to be determined through a critical incident technique during an interview (Fay & Frese, Citation2001). In that way, interviewers can quickly identify the challenges that participants faced and determine the degree of persistence for those challenges. SIEs might delegate a problem during the relocation, instead of attending to it themselves, which is a sign of lower persistence. This may be important as every expatriation is different and the challenges in one location may be different in another.

Incorporating context in research

An aspect of research that we highlighted is that there are many contextual factors that condition the level of personal initiative that is needed for an international relocation and that researchers should consider what impact these factors could have on empirical results. We have demonstrated that the term SIE encompasses a large variety of distinct populations in terms of their level of personal initiative and that combining these distinct groups risks contaminating results and posing a threat to the generalizability of research findings. We therefore support the call by Dorsch et al. (Citation2013) to pay more serious attention to the role of differences within the group of SIEs in future research. SIE research would gain from a systematic and comprehensive consideration and empirical measurement of the personal initiative shown by SIEs. The current operationalization of the broader construct of initiative by self-starting behavior in expatriate research has its limitations. Rather, it is the broader class of behaviors associated with personal initiative that makes initiative important in expatriate settings. We echo the conclusion drawn by Albrecht et al. (Citation2018, p. 192) that ‘studies of expatriate initiative and proactivity would benefit from measuring, rather than assuming, these employee characteristics’. As the level of initiative needed is context-dependent, the context could be the focus of future studies. Using the examples above researchers could compare and contrast the success of expatriates that hail from different countries which have vastly different paths to leaving the country. Some interesting work on the role of context factors has begun, for example, the effect of working for foreign-owned or local organizations on SIEs (Selmer, Lauring, Normann, & Kubovcikova, Citation2015) or the effect of the difficulty of the host country language (Selmer & Lauring, Citation2015). We strongly encourage further work of this nature. Given this there are a few things researchers should include in the methods section.

First, a clear description of the sample should be given. Simply explaining that the participants are SIEs is no longer sufficient. If there are any inherit differences between the sample and an ‘average’ group of international workers they should be explained and noted in the limitations section. Nurses, for example, have a skill set that is in high demand worldwide implying good fit and numerous opportunities abroad so it would require less personal initiative from nurses to relocate internationally as compared to low skilled laborers. Generally, we call for more purposeful sampling. Too often the study population appears to be decided by convenience. There are, of course, many good reasons for mixed samples, like in comparative studies. Another reason for mixed samples would be our desire to learn something about the SIE phenomenon ‘per se’, something that applies to all SIEs irrespective of context factors. This, however, is only possible if the relevant context factors contribute only to the error term; for example, if they cancel each other out rather than bias results systematically. Many mixed samples in SIE research contain disproportionately large clusters of certain professions, home or host countries. In such cases, we believe that it is incumbent on the researcher to demonstrate that these differences do not unduly influence the results. At the very minimum, we should expect a separate breakdown by profession, home and host country or, ideally, by the country dyads involved.

Second, if the sample size allows, control for the context that may influence the results of the research. Studies focusing on SIEs in a single profession, from a single home country in a single host country are extremely rare (i.e., Ramboarison-Lalao et al., Citation2012). We often find mixed samples that combine SIEs from various professions, home and host countries, leading to considerable variance regarding their level of personal initiative (and possibly a number of other relevant factors). What is more, in many cases the description of sample characteristics does not allow for disaggregation by profession, home or host country. Studies are needed that focus on SIEs who change their profession upon relocation and that analyze how the level of personal initiative can help to smoothen transitions and avoid or overcome underemployment. Contextual factors may also heighten or depress empirical results. On the one hand, surveying New Zealand SIEs who are working in the UAE may depress findings surrounding personal initiative. New Zealanders as a population are known to work overseas and UAE has one of the highest expatriate populations in the world. On the other hand, surveying Japanese traveling to any country may improve personal initiative impact on outcomes as they rarely leave for foreign work experiences.

Third, many of the published SIE samples consist of expatriates for whom psychological distance and the need for self-starting behavior is low. By comparison, we know little about SIEs for whom the psychological distance and the need for self-starting behavior is high, such as SIEs living and working in more rural areas. SIEs with personal initiative constitute a large, diverse and yet under-researched population whose high levels of personal initiative could provide a strategic human capital advantage for employers.

Initial research model

We theoretically ground our initial model using conservation of resources (COR) theory. COR theory explains how workers are influenced by gain and loss of resources ( Hobfoll, Citation1988, Citation2001 ). COR theorizes that resources are limited and individuals are driven to obtain, sustain and protect them and lays out two key principles. First, loss of resources are disproportionally more impactful than resource gains. When there are objectively similar gains and losses, the losses create more hardship than the gains. Second, individuals must devote limited resources to gain, maintain and defend resources. Those with resources have an easier time acquiring new resources and are likely to have resource reserves when challenged. Those who are vulnerable ration and defend their depleted resources ( Hobfoll, Citation1988, Citation2001 ). Applying COR theory to our initial research model helps explain why SIEs with personal initiative are more likely to experience success than those without.

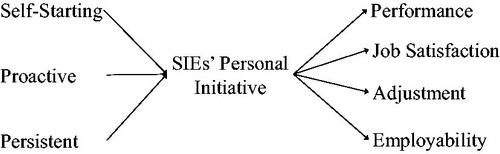

When SIEs show higher levels of personal initiative during their relocation, we expect that they will incur a number of positive outcomes (). Earlier research shows that initiative does lead to better employment results outside of the expatriate context. In a meta-analysis of 163 studies, those employees who possessed higher levels of general personal initiative were found to have higher performance (objective, rated and supervisor) and to experience a higher job satisfaction and lower job stress (Fay & Frese, Citation2001; Tornau & Frese, Citation2013). Similarly, Stroppa and Spieß (Citation2011) found that general personal initiative of AEs related positively to job satisfaction and job performance and negatively to job stress. We would expect to find similar results in the SIE field. Personal initiative enhances expatriates’ chances of success because those employees are more likely to have greater resources than those who lack personal initiative. Specifically, resources for SIEs include mentors, local knowledge, networks, employment, contingency plans, emotional well-being and support of local friends. Learning from mistakes and joining local expatriate groups can help ease the transition and build resilience for expatriates (see ). Similarly, the same study found that initiative was related to job satisfaction (Tornau & Frese, Citation2013).

SIEs who behaviorally initiate () should be able to add resources because they are more likely to set goals, look for information, and monitor feedback. These actions will help them as setting goals leads to positive outcomes (Locke & Latham, Citation2006) and information and feedback lead to better decisions. SIEs who are proactive will add resources, because they will be better prepared to speak the language, understand the culture and have a concrete plan how to move and get started in another country. Without proactive SIE behaviors, expatriates will lose resources attempting to figure everything out while overseas. SIEs who demonstrate persistence will have more resources as they fight through challenges and are more likely to have success and thus resource gains. SIEs who are apt to quit and lack persistence are expected to accumulate resource losses. We expect that SIEs who behaviorally show initiative will have more resources such as mentors, networks, emotional well-being and therefore, we would expect that they will perform better, have higher job satisfaction, adjust better, and will have better employability. While initiative can be an asset for SIEs and the firms that employ them (higher employability), it can also be a liability for international firms. The same situated action that lends to SIEs being better performers should also improve their employment mobility. With high levels of initiative, SIEs will be planning for the future and looking for opportunities to better their career. They should have better networks and they are not constrained to what could be limited regional territories. This leads to them being a flight risk (see Biemann & Andresen, Citation2010).

Translating the new conceptualization to practice

SIEs are a key facet to the future workforce and to the international economy because the need for workers in many countries continues to increase. If personal initiative becomes recognized as a desirable characteristic, understanding how to incorporate these expatriates into their companies’ workforces will become extremely important. Better understanding SIEs, specifically those who have personal initiative, on how to attract, retain and manage them, will be critical to the success of organizations world-wide.

Our conceptualization is relevant because employees that demonstrate personal initiative are increasingly important for organizations for a variety of reasons. To manage successfully in global markets, employees need to proactively manage problems, create or search for new opportunities and make full use of them (Mendenhall, Reiche, Bird, & Osland, Citation2012) and need to show higher levels of personal initiative (Fay & Frese, Citation2000). Personal initiative is also important in view of decentralized decision-making and a reduction of constant close supervision (Sonnentag, Citation2003) requiring a high degree of self-reliance (Fay & Frese, Citation2001). The change of the psychological contract asks employees to adapt to changing job demands and job markets and, thus, to maintain or increase their employability and self-manage their own career (Hall & Chandler, Citation2005). Employees with personal initiative fit the mold with the boundary less career perspective and the change of the psychological contract to employees managing their own careers. Research on the employees’ willingness to take initiative at work is therefore both of practical and of theoretical interest, not only at the national, but also at the international level (Den Hartog & Belschak, Citation2007).

However, until further research is completed, identifying SIEs is a poor proxy of actual personal initiative as it should be measured directly rather than just assumed. Practitioners are well advised to invest into more nuanced investigations of specific decision-making processes of SIEs that apply for jobs. To know about a person’s level of personal initiative is an important aspect that can be used to select individuals with high initiative, to develop the employees’ competencies to show initiative, and to foster an environment in which initiative behavior is supported (Bledow & Frese, Citation2009). Until further research is completed, HRM managers could use contextual factors as another indicator of personal initiative. SIEs that leave war torn countries, nations with high numbers of expatriates, or those who possess highly desirable international skills would be more likely to have average levels of personal initiative. While clearly using context alone is less than ideal, until researchers know more it will have to satisfice.

When further research on SIEs and personal initiative is completed, HRM mangers will have a better understanding on how to manage these unique international workers. It seems likely that those with higher levels of personal initiative, on average, will be able to operate more independently and perform at higher levels than those with lower levels of personal initiative. How to identify and attract these workers to firms will have to be delineated in the future. We suspect that these workers will specifically be attracted to positions that will further their career. HRM managers will need better methods to identify those with personal initiative. Once these are obtained, they will be able to make better informed decisions on employees. The challenge in managing SIEs high in personal initiative will be retention. After all, these are workers who are not bound by even national borders. They are likely to continuously seek better opportunities. More needs to be learned about this population but HRM managers will have to be aggressive and creative in trying to retain SIEs. Ultimately, the goal of better understanding SIEs and personal initiative is that the attraction, selection and retention of these international workers so that firms can gain a strategic human capital advantage. Until more research is conducted, HRM managers will have to continue to make uninformed judgments about hiring SIEs.

Conclusion

While it is recognized that personal initiative is an important behavior for workers to expound, it is unclear how far SIEs can be attributed to establish initiative. This conceptual analysis confirms that personal initiative is assumed important but is not robustly defined in the expatriation context and is rarely measured. In order for the field to move forward we need to develop a more sophisticated perspective of SIEs. SIEs do not all show the same level of initiative and many are influenced by mitigating circumstances. The goal of this analysis is to encourage future research that will grow and develop our understanding of SIEs. We have conceptualized, defined, started the operationalization and developed a preliminary model to encourage personal initiative to be empirically tested in SIE research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Our systematic literature review of 171 SIE peer-reviewed, empirical articles published between 1997 and 2019 shows that only 30.4% included a specific measure indicating how SIEs had been identified in the methods section, and here with reference to only one out of the three criteria of personal initiative at the maximum (25.7% referred to self-starting and 4.7% to proactive behavior). The most frequent measure were survey items that asked expatriates whether they went abroad on their own initiative and whether they had sought or searched for employment internationally on their own initiative in a new organization. These items treat this continuous quantitative variable of personal initiative as a dichotomous variable, leading to limitations in terms of measurement and statistical analyses (see MacCallum, Zhang, Preacher, & Rucker, Citation2002).

References

- Albrecht, A.-G., Dilchert, S., Ones, D. S., Deller, J., & Paulus, F. M. (2018). Success among self-initiated versus assigned expatriates. In B. W. Wiernik, H. Rüger, & D. S. Ones (Eds.), Managing expatriates: Success factors in private and public domains (pp. 183–194). Opladen, Berlin & Toronto: Barbara Budrich Publishers.

- Andresen, M., Bergdolt, F., Dickmann, M., & Margenfeld, J. (2014). Addressing international mobility confusion: Developing definitions and differentiations for self-initiated and assigned expatriates as well as migrants. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(16), 2295–2318. doi:10.1080/09585192.2013.877058

- Andresen, M., & Margenfeld, J. (2015). International relocation mobility readiness and its antecedents. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 30(3), 234–249. doi:10.1108/JMP-11-2012-0362

- Arslan, C., Dumont, J.-C., Kone, Z., Moullan, Y., Ozden, C., Parsons, C., & Xenogiani, T. (2014). A new profile of migrants in the aftermath of the recent economic crisis. Working Paper No. 160. Paris: OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers.

- Bassham, G., Irwin, W., Nardone, H., & Wallace, J. M. (2008). Critical thinking: A student’s introduction (3rd.ed.). Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill.

- Bateman, T. S., & Crant, J. M. (1993). The proactive component of organizational behavior: A measure and correlates. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 14(2), 103–118.

- Bauder, H. (2015). The international mobility of academics: A labour market perspective. International Migration, 53(1), 83–96. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2435.2012.00783.x

- Beaney, M. (2017). Analysis. In Zalta, E. N. (Ed.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy (Winter 2017 Edition). Retrieved May 11, 2018, from https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2017/entries/analysis/.

- Begley, A., Collings, D. G., & Scullion, H. (2008). The cross-cultural adjustment experiences of self-initiated repatriates to the Republic of Ireland labour market. Employee Relations, 30(3), 264–282. doi:10.1108/01425450810866532

- Belot, M., & Ederveen, S. (2012). Cultural barriers in migration between OECD countries. Journal of Population Economics, 25(3), 1077–1105. doi:10.1007/s00148-011-0356-x

- Biemann, T., & Andresen, M. (2010). Self-initiated foreign expatriates versus assigned expatriates: Two distinct types of international careers?. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 25(4), 430–448. doi:10.1108/02683941011035313

- Bledow, R., & Frese, M. (2009). A situational judgment test of personal initiative and its relationship to performance. Personnel Psychology, 62(2), 229–258. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2009.01137.x

- Bolino, M. C., & Turnley, W. H. (2005). The personal costs of citizenship behaviour: The relationship between individual initiative and role overload, job stress, and work-family conflict. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(4), 740–748. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.90.4.740

- Cerdin, J.-L., & Selmer, J. (2014). Who is a self-initiated expatriate? Towards conceptual clarity of a common notion. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(9), 1281–1301. doi:10.1080/09585192.2013.863793

- Ceric, A., & Crawford, H. J. (2016). Attracting SIEs: Influence of SIE motivation on their location and employer decisions. Human Resource Management Review, 26(2), 136–148. doi:10.1016/j.hrmr.2015.10.001

- Cloninger, C. R., Przybeck, T. R., & Svrakic, D. M. (1991). The tridimensional personality questionnaire: US normative data. Psychological Reports, 69(3), 1047–1057.

- Davies, S., Froese, F., & Kraeh, A. (2015). Burden or support? The influence of partner nationality on expatriate cross-cultural adjustment. Journal of Global Mobility: The Home of Expatriate Management Research, 3(2), 169–182. doi:10.1108/JGM-06-2014-0029

- Doherty, N. (2013). Understanding the self‐initiated expatriate: A review and directions for future research. International Journal of Management Reviews, 15(4), 447–469. doi:10.1111/ijmr.12005

- Doherty, N., Dickmann, M., & Mills, T. (2011). Exploring the motives of company-backed and self-initiated expatriates. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22(3), 595–611. doi:10.1080/09585192.2011.543637

- Dorsch, M., Suutari, V., & Brewster, C. (2013). Research on self-initiated expatriation: History and future directions. In M. Andresen, A. Al Ariss, & M. Walther (Eds.), Self-initiated expatriation: Individual, organizational, and national perspectives (pp. 42–56). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Fay, D., & Frese, M. (2000). Self-starting behavior at work: Towards a theory of personal initiative. In J. Heckhausen (Ed.), Motivational psychology of human development: Developing motivation and motivating development (pp. 307–324). New York, NY: Elsevier.

- Fay, D., & Frese, M. (2001). The concept of personal initiative (personal initiative): An overview of validity studies. Human Performance, 14(1), 97–124. doi:10.1207/S15327043HUP1401_06

- Frese, M., & Fay, D. (2001). Personal initiative: An active performance concept for work in the 21st century. Research in Organizational Behavior, 23, 133–187. doi:10.1016/S0191-3085(01)23005-6

- Frese, M., & Fay, D. (2015). Personal initiative. In N. Nicholson, P. G. Audia, & M. M. Pillutla (Eds.), The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Management (2nd ed., pp. 311–312). Oxford: Blackwell.

- Frese, M., Fay, D., Hilburger, T., Leng, K., & Tag, A. (1997). The concept of personal initiative: Operationlization, reliability and validity in two German samples. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 70(2), 139–161. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8325.1997.tb00639.x

- Fu, C., Hsu, Y. S., A. Shaffer, M., & Ren, H. (2017). A longitudinal investigation of self-initiated expatriate organizational socialization. Personnel Review, 46(2), 182–204. doi:10.1108/PR-05-2015-0149

- Furner, J. (2004). Conceptual analysis: A method for understanding information as evidence, and evidence as information. Archival Science, 4(3/4), 233–265. doi:10.1007/s10502-005-2594-8

- Furusawa, M., & Brewster, C. (2018). Japanese self‐initiated expatriates as boundary spanners in Chinese subsidiaries of Japanese MNEs: Antecedents, social capital, and HRM practices. Thunderbird International Business Review, 60(6), 911–919. doi:10.1002/tie.21944

- Guo, C., Porschitz, E. T., & Alves, J. (2013). Exploring career agency during self‐initiated repatriation: A study of Chinese sea turtles. Career Development International, 18(1), 34–55. doi:10.1108/1362043131130

- Hall, D. T., & Chandler, D. E. (2005). Psychological success: When the career is a calling. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(2), 155–176. doi:10.1002/job.301

- Hartog, D. N., & Belschak, F. D. (2007). Personal initiative, commitment and affect at work. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 80(4), 601–622. doi:10.1348/096317906X171442

- Hobfoll, S. E. (1988). The ecology of stress. New York, NY: Hemisphere.

- Hobfoll, S. E. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology, 50(3), 337–370. doi:10.1111/1464-0597.00062

- Howe-Walsh, L., & Schyns, B. (2010). Self-initiated expatriation: Implications for HRM. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 21(2), 260–273. doi:10.1080/09585190903509571

- Hussain, T., & Deery, S. (2018). Why do self-initiated expatriates quit their jobs: The role of job embeddedness and shocks in explaining turnover intentions. International Business Review, 27(1), 281–288. doi:10.1016/j.ibusrev.2017.08.002

- Inkson, K., Arthur, M. B., Pringle, J., & Barry, S. (1997). Expatriate assignment versus overseas experience: Contrasting models of international human resource development. Journal of World Business, 32(4), 351–368. doi:10.1016/S1090-9516(97)90017-1

- Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2006). New directions in goal-setting theory. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15(5), 265–268. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2006.00449.x

- MacCallum, R. C., Zhang, S., Preacher, K. J., & Rucker, D. D. (2002). On the practice of dichotomization of quantitative variables. Psychological Methods, 7(1), 19–40. doi:10.1037//1082-989X.7.1.19

- Mackintosh, J. (2001). Øst, vest - hjemme bedst? Danske emigranters oplevelser ved gensynet med Danmark. København: Borgen.

- Mendenhall, M. E., Reiche, B. S., Bird, A., & Osland, J. S. (2012). Defining the “global” in global leadership. Journal of World Business, 47(4), 493–503. doi:10.1016/j.jwb.2012.01.003

- Morano‐Foadi, S. (2005). Scientific mobility, career progression, and excellence in the European research area. International Migration, 43(5), 133–162.

- Olsthoorn, J. (2017). Conceptual Analysis. In Blau, A. (Ed.), Methods in analytical political theory (pp. 153–191). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Panteia (2012). Evaluation of the legal framework for the free movement of lawyers: Final report. Zoetermeer:Author.

- OECD. (2018). International migration outlook 2018. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Petocz, A., & Newbery, G. (2010). On conceptual analysis as the primary qualitative approach to statistics education research in psychology. Statistics Education Research Journal, 9(2), 123–145.

- Ramboarison-Lalao, L., Al Ariss, A., & Barth, I. (2012). Careers of skilled migrants: Understanding the experiences of Malagasy physicians in France. Journal of Management Development, 31(2), 116–129. doi:10.1108/02621711211199467

- Richardson, J., & McKenna, S. (2002). Leaving and experiencing: Why academics expatriate and how they experience expatriation. Career Development International, 7(2), 67–78. doi:10.1108/13620430210421614

- Sackmann, S. A., & Phillips, M. E. (2004). Contextual influences on culture research: Shifting assumptions for new workplace realities. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 4(3), 370–390. doi:10.1177/1470595804047820

- Selmer, J., Andresen, M., & Cerdin, J.-L. (2017). Self-initiated expatriates. In Y. McNulty, & J. Selmer (Eds.), Research Handbook of Expatriates (pp. 187–201). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Selmer, J., & Lauring, J. (2015). Host country language ability and expatriate adjustment: The moderating effect of language difficulty. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 32(2), 194–210.

- Selmer, J., Lauring, J., Normann, J., & Kubovcikova, A. (2015). Context matters: Acculturation and work-related outcomes of self-initiated expatriates employed by foreign vs. local organizations. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 49, 251–264. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2015.05.004

- Silver, C., De Bruin Phelan, N., & Rabinowitz, M. (2009). Between diffusion and distinctiveness in globalization: US law firms go glocal. The Georgetown Journal of Legal Ethics, 22, 1431–1471.

- Sonnentag, S. (2003). Recovery, work engagement, and proactive behavior: A new look at the interface between non-work and work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(3), 518–528. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.3.518

- Stroppa, C., & Spieß, E. (2011). International assignments: The role of social support and personal initiative. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35(2), 234–245.

- Sugimoto, Y. (2014). An introduction to the Japanese society (4th ed.). Port Melbourne: Cambridge University Press.

- Suutari, V., & Brewster, C. (2000). Making their own way: International experience through self-initiated foreign assignments. Journal of World Business, 35(4), 417–436. doi:10.1016/S1090-9516(00)00046-8

- Teichler, U. (2015). Academic mobility and migration: What we know and what we do not know. European Review, 23(S1), S6–S37. doi:10.1017/S1062798714000787

- Tharenou, P. (2010). Women’s self-initiated expatriation as a career option and its ethical issues. Journal of Business Ethics, 95(1), 73–88. doi:10.1007/s10551-009-0348-x

- Tharenou, P. (2015). Researching expatriate types: The quest for rigorous methodological approaches. Human Resource Management Journal, 25(2), 149–165. doi:10.1111/1748-8583.12070

- Thorn, K. (2009). The relative importance of motives for international self-initiated mobility. Career Development International, 14(5), 441–464. doi:10.1108/13620430910989843

- Tornau, K., & Frese, M. (2013). Construct clean-up in proactivity research: A meta-analysis on the nomological net of work-related proactivity concepts and their incremental validities. Applied Psychology, 62(1), 44–96. doi:10.1111/j.1464-0597.2012.00514.x

- Wang, Z., De Graaff, T., & Nijkamp, P. (2016). Cultural diversity and cultural distance as choice determinants of migration destination. Spatial Economic Analysis, 11(2), 176–200. doi:10.1080/17421772.2016.1102956

- Wihler, A., Blickle, G., Parker Ellen, B., III, Hochwarter, W. A., & Ferris, G. R. (2014). Personal initiative and job performance evaluations: Role of political skill in opportunity recognition and capitalization. Journal of Management, 20(10), 1–33. doi:10.1177/0149206314552451

- World Population Review (2019). Qatar, Saudi Arabia and UAE Population. Retrieved May 7, 2019, from http://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/saudi-arabia/. ; http://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/united-arab-emirates/. ; http://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/qatar/.

- Yamazaki, Y. (2010). Expatriate adaptation: A fit between skills and demands among Japanese expatriates in USA. Management International Review, 50(1), 81–108. doi:10.1007/s11575-009-0022-7

- Yoshida, T., Matsumoto, D., Akashi, S., Akiyama, T., Furuiye, A., Ishii, C., & Moriyoshi, N. (2009). Contrasting experiences in Japanese returnee adjustment: Those who adjust easily and those who do not. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 33(4), 265–276. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2009.04.003

- Yoshida, T., Matsumoto, D., Akiyama, T., Moriyoshi, N., Furuiye, A., & Ishii, C. (2003). Peers’ perceptions of Japanese returnees. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 27(6), 641–658. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2003.08.005