Abstract

HR Analytics (HRA) are said to create value when providing analytical outputs that are relevant to decision-makers’ immediate business issues. While extant research on HRA attributes success (or lack thereof) in providing business relevant outputs to the presence or absence of particular skills and resources, we know little about how practitioners actually mobilize these skills and resources in daily practice. Drawing on observational and interview data from a case study of an HRA team, we identify boundary spanning, customizing dashboards, and speaking a language of numbers as three epistemic practices in which team members combine and mobilize a particular set of skills and resources that allows them to accomplish epistemic alignment, i.e. aligning to decision-makers’ perception of business reality when creating analytical outputs. Epistemic alignment enables the team members to produce complex analytical outputs while at the same time staying close to the decision-makers’ immediate business problems. At the same time, team members are capable of accounting for conditions in the broader organizational context, such as compliance issues, dependencies, political tensions, and a prevailing data-driven decision culture. Our findings contribute to knowledge on how organizations can build effective HRA and how advanced forms of digitalization transform the work of HRM in contemporary organizations.

Supplemental data for this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2021.1886148. The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, ME. The data are not publicly available due containing information that could compromise the anonymity and privacy of research participants.

Introduction

Increased possibilities to gather, store, and process data have spawned unprecedented possibilities to generate insights for understanding, predicting, and controlling business outcomes (Davenport, Citation2006). In the Human Resource Management (HRM) domain, these developments have recently sparked a vivid interest in HR Analytics (HRA), i.e. leveraging data for supporting HR decision-making in organizations. As with other ‘waves’ of digitalization in that past (Bondarouk et al., Citation2017), one central question arising from such technological shifts is how they affect the work and perception of HRM in organizations (Angrave et al., Citation2016; Bondarouk & Ruël, Citation2009; Marler & Boudreau, Citation2017; Strohmeier & Parry, Citation2014; van der Laken, Citation2018). One central hallmark in extant literature is that HRA can support value creation when it is capable of providing business relevant outputs, that is, actionable insight into how HR-related events, developments, or trends relate to decision-makers’ immediate business outcomes (Minbaeva, Citation2018; Rasmussen & Ulrich, Citation2015; van den Heuvel & Bondarouk, Citation2017). How such relevance is achieved, however, remains a quite open question in current HRA literature. Yet, knowing the process of how HRA practitioners come to ask the ‘right questions’ and turn data into ‘actionable insight’ is far from trivial as it can bring detailed insights into how HRM can effectively support value creation and how this affects the perception and recognition of the HRM function in organizations (Greasley & Thomas, Citation2020; Legge, Citation1978).

Extant literature argues that building business relevant HRA requires organizations to establish particular skills and resources at the individual and organizational level. These include suitable theoretical frameworks articulating connections between HR, individual and organizational outcomes, and strategic goals while ensuring proximity to actual business issues (Boudreau & Cascio, Citation2017; Levenson, Citation2017; Peeters et al., Citation2020; Rasmussen & Ulrich, Citation2015), appropriate data and technology management (Minbaeva, Citation2018; van den Heuvel & Bondarouk, Citation2017), as well as appropriate research and communication skills (‘storytelling’) (Boudreau & Cascio, Citation2017; Levenson, Citation2017; Minbaeva, Citation2018). Research further recommends to establish workflows and effective knowledge transfer mechanisms (Boudreau & Cascio, Citation2017; Minbaeva, Citation2018; van den Heuvel & Bondarouk, Citation2017), e.g. by facilitating close cooperation with other departments such as finance or marketing (Rasmussen & Ulrich, Citation2015).

While having these skills and resources is certainly of high importance for generating business relevant outputs, extant perspectives tend to be normative rather than empirical and adopt a quite static view on HRA. In particular, they attribute the success (or lack thereof) of HRA to the presence or absence of certain skills and resources. Hardly any attention has been dedicated to how such skills and resources are actually mobilized in daily HRA practice, e.g. how HRA practitioners leverage existing networks to synergize their knowledge, skills, and resources with those of other departments (e.g. Barbour et al., Citation2017), or what role technology particularly plays in these processes (e.g. Anthony, Citation2018; Kaplan, Citation2011).

In this paper, we use observational and interview data from a case study of an HRA team at TechCom, a German MNC operating in the technology sector, giving insights into the situated, social activities of HRA. By empirically illustrating how team members attempt to render analytical outputs relevant for the HR board member of TechCom, we answer the following research questions: Through which practices do HRA practitioners render HRA outputs relevant to decision-makers? And what skills and resources do practitioners mobilize in these practices? By answering these questions, we contribute to existing HRA literature by providing suggestions of what organizations can do to establish effective HRA. We further contribute to wider debates on the digitalization of HRM by showing how advanced forms of digitalization transform the work of HRM in contemporary organizations.

HRA as epistemic practice

To explore practices by which HRA practitioners render HRA outputs relevant to decision-makers, we apply an ‘HRM-as-practice’ lens as proposed by Björkman et al. (Citation2014), conceptualizing HRM as social phenomenon brought into being by the everyday activity of practitioners. Putting the focus on the ‘practice of HRA’, we understand HRA as the situated, social activities of individuals and groups involved in HRA work (Björkman et al., Citation2014) with the goal to create knowledge relevant to decision-makers in organizations.

Framing HRA as a practice of knowledge creation suggests conceptual proximity to epistemic practices, denoting recurrent activities of developing, acquiring, and validating knowledge (Knorr Cetina, Citation1999, Citation2005). Epistemic practices are considered as objectual (Knorr Cetina, Citation2005) as they evolve and form around epistemic objects, i.e. issues under investigation characterized as unknown, or vaguely known, open-ended, and question-generating. An example of an epistemic object could be the question: Why do people leave our organization? When practitioners work with epistemic objects, they are on their way of becoming technical objects, i.e. fixed, ready-at-hand objects that perform according to known regularities. A technical object in HRA could be a diagram based on a statistical model showcasing the drivers of employee attrition in a particular period.

Fueled by digitalization, epistemic practices heavily rely on a range of technologies shaping how practitioners generate and present knowledge. We refer to these technologies as epistemic technologies, defined as instruments used to engage in the investigation, construction, and presentation of knowledge (Anthony, Citation2018; Kaplan, Citation2011). Digital technologies discussed in the context of HRM, mostly referred to as electronic HRM (eHRM) technologies (Bondarouk & Ruël, Citation2009), usually support users to perform and monitor particular HRM tasks, such as recruiting or talent management (Ellmer & Reichel, Citation2018). HRA projects generating insights into a new business-related issue, however, require technologies allowing practitioners to flexibly calculate, visualize, and present analytical outputs (e.g. R or Tableau). In this paper, we focus on the latter type of digital technology.

Research design and methods

Case selection and data collection

For gaining insights into how HRA practitioners shape HRA outputs relevant according to the requirements of decision-makers, we conducted a single case study (Eisenhardt, Citation1989) of an HRA team at TechCom, a German MNC in the technology sector operating in 120 countries worldwide. Based on media coverage, we expected TechCom to have well-established HRA and searched for contact details of the company’s HR department online. The HR department connected us with the HRA team and after some email conversation we called Christopher, the team leader, who gave us an extensive overview of the team’s workflows, their skills and resources, and how these were developed in the past years. Christopher and the rest of the team also proved to be very research oriented and thus open to being observed in and asked about their daily work. As our research interest lies in how HRA practitioners mobilize particular skills and resources to create relevant analytical outputs in daily practice, the HRA team presented a valuable case setting.

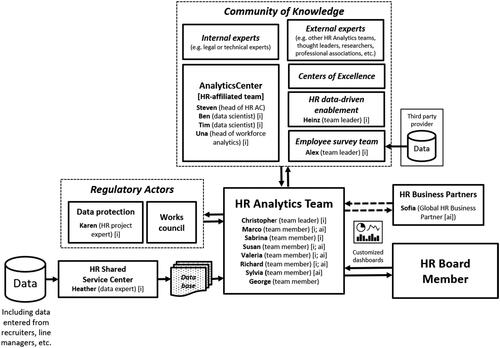

Proceeding from the first contact, the first author collected qualitative data within a 7-month period triangulating several methods, including formal semi-structured interviews, observations, and ad-hoc interviews, mutually informing each other during the data collection process. Before and during our observations, we conducted 13 scheduled open-ended, semi-structured interviews (average duration more than one hour) at relevant practice sites, including interviews with team members and representatives of their ‘community of knowledge’ (see , where an [i] indicates a formal interview conducted with this person). Based on a standardized interview guide we asked questions on how HRA projects are organized, on collaborations with the team’s community of knowledge, central technologies in-use, and how data protection and the works council influence HRA practices.

Information gathered in the first semi-structured interviews informed our subsequent observations. We collected over 90 h of non-participant observation, including the observation of 23 meetings on running HRA projects. While observations in the offices uncovered more mundane activities of the team members, observations of meetings allowed us to observe the HRA team members interacting with each other. In 10 of the observed meetings only members from the HRA team participated. The other 13 were held with representatives of the team’s community of knowledge, e.g. from the employee survey department, or internal experts, such as from the German labor relations (see in the Appendix for details). The observations resulted in detailed observation journals including minute details of single activities as well as minutes of salient quotes caught during the interactions. During the first half of our observations, we were able to observe the HRA team preparing analytical outputs for an upcoming quarterly board meeting. Accordingly, the whole ‘epistemic machinery’ (Kaplan, Citation2011) was working on a comparably high level. In the second half, by contrast, the HRA practitioners were working on a more routine level. Comparing and contrasting these different phases allowed us inducting clear and saturated categories of epistemic practices accomplished by the team members. During our observations, we conducted six ad-hoc interviews (see ‘[ai]’ in ) in which team members answered questions of understanding collected during the observations, e.g. information on organizational structures, further details on their own role, details on people they had called and discussed with, or background information on projects mentioned during the meetings. Complementary to the interviews, we analyzed a range of public documents, such as videos and practitioner-oriented blog articles written by the HRA team members for better contextualizing our observations.

Table 1. Skills and resources related to HRA at TechCom.

Finally, by conducting ad-hoc interviews and by presenting initial preliminary findings of our data analysis to the HRA team at the end of our observations we leveraged member checks (Lincoln & Guba, Citation1985) in our data interpretation. In particular, the comments and feedback of the team members allowed us for increasing the external validity of our findings as we were able to interpret information obtained from the interviews and observations in a more authentic manner in order to avoid exaggerations in data presentation, etc.

Case setting: HRA at TechCom

Before describing how we analyzed the collected data, we briefly describe the setting, i.e. the organizational context at TechCom, the overall structure and workflows related to HRA, as well as the skills and resources identified at the HRA team.

At TechCom, HRM is generally considered as an important topic. As tech companies are frequently in danger of facing severe talent shortages, TechCom aimed to transform itself into a ‘people organization’ to attract and retain critical talent. HRA practices were considered to support HR decisions to reach this goal and were thus strongly promoted in the past decade. Promoting HRA also resonated with a strong data-driven culture at TechCom, demanding a style of decision-making based on data and facts rather than personal experience or intuition (Rasmussen & Ulrich, Citation2015). Data-driven decision-making was installed as a mind-set in all HR operations, resulting in a strong obligation, but also preference, for quantitative types of knowledge for HR professionals at TechCom (Greasley & Thomas, Citation2020). As an HR business partner (HRBP) noted in an ad-hoc interview:

At TechCom, nobody gets anywhere without numbers, anyway. Somebody saying: ‘I have the feeling that this or this is the case’–that does not exist. (Sofia, HRBP)

This context provided a favorable position for the HRA practitioners studied. Nonetheless, they had to put considerable effort in building up HRA in its present form. Christopher, the HRA team leader who was deeply involved in this building process, remembered a meeting about 10 years ago, where they still had to pin printed analytics dashboards on pin boards. In this meeting, a huge confusion in the figures presented occurred.

[A]nd then a lot of people left and said: Man, yes, it’s just that, HR never gets the numbers in order! It’s all worthless what we’re doing here! (Christopher, HRA team leader)

Since the HR function started to professionalize its HRA processes, however, ‘such discussions are gone’ (Christopher) and the team perceives that decision-makers now recognize the value of HRA. This positively affects the overall recognition of the HR function at TechCom. As Christopher, the team leader, described:

Meanwhile, we’ve reached the point where people say: Man, we need much, much more analytics, because … everything is getting better somehow, and because then we’ll have answers to our questions! (Christopher, HRA team leader)

How does HRA at TechCom work and what skills and resources are present in these processes? (see above) provides an overview over the most important actors involved in HRA practices at TechCom, including the affiliation of our interview partners.

The HRA team at the very center is responsible for overseeing current HRA projects, including the processing and delivery of analytical outputs. All members have a high level of theoretical knowledge as well as research and methods skills with more than a half of the team holding a PhD degree in HRM or business psychology. For practicing HRA, the team maintains star-like connections to a broad community of knowledge including actors across TechCom as well as beyond organizational boundaries where professionals hold relevant expertise. For creating analytical outputs, the HRA team has vivid exchange with data scientists specialized in HRM at the AnalyticsCenter (AC) which have exclusive full access to all data at TechCom as well as strong methods skills. When processing outputs, the HRA team members and particularly the AC also have regular exchange with regulatory actors, i.e. the works council and the data protection office.

While the HRA team supports decision-makers at various levels (e.g. the leaders of the HR Centers of excellence (CoEs), or line managers at different levels) as well as HRBPs, we focus our analysis on how team members create analytical outputs for the HR board member at TechCom. When starting an analytical project, the team members have some exchange with the board member in which they gather information on the needs and requirements of the analytical outputs from the board member’s perspective (this happened prior to our observations). Based on these inputs, the HRA team conducts research related to the issue at hand, collects related data, and runs analyses. If the analysis gives insights into a recurring issue (e.g. prediction of employee attrition), the team integrates the outputs into the HR board member’s standard dashboard, showcasing statistics, diagrams, and figures on current and/or strategically relevant HR issues.

In the past years, TechCom made considerable investments into its technological infrastructure, including a highly reliable data base system as well as data analysis and visualization software, including SAP and open source systems. To ensure high data quality, data management is centralized in the HR shard service center where employees standardize and clean incoming data from various information systems. The data visualization software in place allows building dashboards that present real-time data through various elements (different diagrams, figures, text fields, etc.) that can be easily integrated and exchanged. Data scientists working in the AC can also integrate functions into the single dashboard elements (e.g. a mouse-over function or adding filters). summarizes the most important skills and resources we found to be relevant in the work of the HRA team members.

Data analysis

For identifying HRA-related practices for rendering HRA outputs relevant at TechCom, we informed our data analysis by a Grounded Theory coding approach, differentiating into the phases of open, axial, and selective coding (Corbin and Strauss, Citation1990). In the first phase of open coding, the HRA-as-practice approach directed our analytical focus to the everyday activity in both its routine and improvised forms (Feldman & Orlikowski, Citation2011). In particular, we looked out for certain sets of activities of HRA practitioners and how they navigate relationships with other practitioners and stakeholders in tandem with using different technologies for crafting analytical outputs.

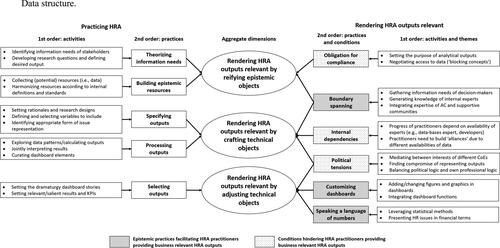

Based on our interest in how HRA practitioners render HRA outputs relevant in their daily HRA praxis (Björkman et al., Citation2014), we inducted several practices related to conducting HRA which we summarized in three practice dimensions: Reifying epistemic objects, crafting technical objects, and adjusting technical objects. In a second round, we looked out for activities and themes that supported or hindered the HRA practitioners to render outputs relevant by identifying quotes and observed activities related to their interaction with decision-makers and other groups. This resulted in different practices of the HRA team members as well as conditions in the organizational context at TechCom.

In the phase of axial coding, we structured the practices and conditions in an integrated overview as proposed by Gioia et al. (Citation2013), allowing us to leverage practices articulating theoretical relationships between the themes discovered in the data (Feldman & Orlikowski, Citation2011). In the final phase of selective coding, we extracted those codes and categories relevant for gaining insights for our research question (see in ) and challenged our findings in light of extant literature to create reasonable connections between data and existing literature.

Findings

As mentioned above, we focus our findings section on empirical illustrations where the HRA team created analytical outputs for the HR board member at TechCom. To this end, we crafted small episodes from our observational and interview data to elucidate the interplay of skills and resources and the practices and themes connected to the theoretical dimensions of interest (see ).

Rendering HRA outputs relevant by reifying epistemic objects

Reifying an epistemic object denotes HRA practitioners collecting information for exploring possibilities and options for its representation as a technical object. As mentioned above, the starting points for reifying an epistemic object were either decision-makers or members of the HRA team coming up with an HR issue, which at this stage is usually very undetermined, fuzzy, and question-generating. To ensure the relevance of the epistemic object at this stage, team members assess and discuss whether the issue relates to the overall strategy of TechCom as well as to a sufficiently concrete business question. The team members stated that value for decision-makers results from ‘staying close to business’ and their ‘immediate [business] decisions’ (Christopher) rather than just digging into topics that appear interesting in from a research perspective. As Sabrina explained:

(…) what I find important is solving concrete business issues and problems. It’s not about us finding a topic cool and just doing our thing, but we have to solve a problem from the business areas and work very closely with them. And only then we actually create value (Sabrina, HRA team member).

If the epistemic object meets the criteria of addressing an actual business problem, the members integrate the epistemic object into their portfolio and start the reification process. A good example for reifying an epistemic object during the observations was the ‘birth’ of a KPI for the HR board member, as described in the following episode.

As structural reorganizations at TechCom increased in the past few years, the HR board member asked the HRA team to integrate KPIs showing how reorganizations affect the well-being and productivity of employees in his dashboard. Two team members, Susan and Richard, were assigned with the task. They started to theorize reorganizations by looking for definitions of reorganizations in academic and business consultation literatures and speculated what information and theoretical constructs (i.e., dependent variables) could be most relevant for the board member. After having a first idea of what reorganization is, they reached out to a range of colleagues to gather knowledge, experience, and data related to reorganizations. These included a colleague working at the German labor relations department, a member of the employee survey team, and a colleague who was involved in a reorganization process at TechCom in the past. After some meetings, Susan and Richard had accumulated a considerably more complex picture of reorganizations, thus adding new constructs and discarding existing ones to their conceptualizations. They also had an overview over what kind of data was available and learned about potential worries of the works council regarding reorganizations. This information provided them with a better understanding of what aspects of reorganizations could be relevant for the board member and allowed them to develop first ideas on building appropriate KPIs.

As the episode shows, a first central practice of reifying an epistemic object is theorizing information needs and ideas, terming a delocalization and abstraction of HR/business issues into tangible and business-related questions and models. In theorizing activities, team members mobilize research and methods skills as well as conceptual and theoretical HRM/OB knowledge and build on the resource of their access to a community of knowledge, i.e. a network of internal and external actors providing important knowledge to their issue at hand. Research and methods skills allow team members for gathering information needs and requirements of the decision-makers and to extend their knowledge on a particular issue by talking to a range of internal and external experts. When gathering information on the epistemic object at hand, linking HRM/OB concepts and theory to the needs and requirements of decision-makers allows them to focus their analytical efforts as well as their discussions with members of the community of knowledge. A second central practice apparent in the episode is building epistemic resources. Again, mobilizing research and methods skills, conceptual and theoretical HRM/OB knowledge and leveraging the community of knowledge, team members identify actors who have potentially interesting data related to the information need of the board member. Collecting these resources sometimes requires harmonizing data, e.g. by streamlining underlying definitions.

These HRA practices were closely related to the practice of boundary spanning, i.e. linking the internal knowledge of the team on a particular issue with external sources of information. By mobilizing their conceptual and theoretical HRM/OB knowledge and research and methods skills, practitioners frequently and systematically reached out to experts for tapping their experience and knowledge related to the epistemic object in question. Gathering these insights helped them to confront the information needs and requirements of the board member with the actual business reality, which directed their attention to important details to be integrated in their theorizing.

Boundary spanning was also part of ensuring compliance of analytical projects where the team members could rely on their community of knowledge. Industrial relation laws and data protection laws in Europe and Germany fundamentally shape HRA practitioners’ scope of action. As implied in the episode, reifying epistemic objects needs a strong consideration of compliance issues with two main regulatory groups at TechCom, i.e. the works council and the data protection office (see ). This mostly concerned negotiating the analytical outputs’ ‘purpose’ of the information provided in the dashboards as the works council had to acknowledge the purpose and use of each. As Christopher outlined:

And of course [the works council] is concerned that we create the ‘fully transparent employee’ and so on. So, at this point (…), we have to negotiate the purpose of each single project. (Christopher, HRA team leader)

When we started our observations, however, this situation was easier–thanks to the community of knowledge: Una, an expert in the AC, was able to negotiate an agreement by which KPIs with a purpose already negotiated could be integrated in any dashboard without the works council’s confirmation. Each new KPI added, however, required another confirmation by the works council.

Concerning data protection, HRA practitioners had to justify their ‘need-to-knows’ and the ‘business needs’ for which they utilized specific data. To ensure compliance, Karen, an expert for HR data in the data protection office, developed ‘blocking concepts’ based on these needs to ensure that employees can only access the data they actually need for their role. While complying with law, this also led to the HRA team members having only limited access to data they would have needed for checking the possibilities for presenting an epistemic object at hand. As a result, the constant quest for legal compliance strongly affected the team members’ scope of action for providing analytical outputs.

Rendering HRA outputs relevant by crafting technical objects

After having reified an epistemic object at hand, the HRA team members move to crafting technical objects, i.e. building a first representation of the epistemic object in question (i.e. ‘pre-technical objects’). In this phase, the HRA practitioners mobilize skills related to research methods and resources of high-quality data and technologies available, as well as their access to their community of knowledge, particularly the data scientists in the AC. The following episode gives insight into the crafting of a technical object in the office of the HRA team.

Marco receives a call from Tim, a data scientist from the AC, to go through some results Tim had calculated. When they explored drivers why people leave TechCom (‘attrition drivers’) some time ago, China turned out to be somehow puzzling compared to other countries and regions. In some prior meetings, they had specified the research design and input variables for gaining a better understanding of the issue. Tim, who as a data scientist has full access to all data at TechCom, has now run a random forest model based on the agreed input. In the call, they go through the results and exchange their interpretations of the patterns discovered. During the joint interpretation, Marco requests some ad-hoc calculations and charts, e.g., results according to board area or hierarchical level. Tim instantly delivers these calculations via screen transmission. Based on their data explorations they conclude that payment seems to play the most important role while age plays the most marginal. In the end, Marco instructs Tim how to present some selected results for delivering them to the board member in a tangible fashion.

As the episode shows, one central practice related to crafting technical objects is specifying outputs. Specifying outputs requires a range of research and methods skills, such as setting rationales and research designs, and defining and selecting variables–in the case of the episode above, the two practitioners did this up-front in various meetings. When crafting dashboards, practitioners mainly discussed how to represent the issue at hand in an appropriate form to the HR board member. Most importantly, they debated what kind of diagrams (e.g. bar diagrams or heat maps) would be most applicable and useful, especially in the upcoming board meeting. A second and related practice when crafting technical objects was processing outputs. As illustrated by the episode, this, again, included research and methods skills such as exploring data, calculating results, and jointly interpreting them. In case of crafting dashboards presenting recurrently important HR issues, HRA team members mainly discussed and identified the most appropriate form of issue representation (e.g. what diagram suits best to present available data) for decision-makers.

When crafting technical objects, HRA practitioners, again, extensively drew on boundary spanning. In the episode, Marco reached out to Tim with an HR issue at hand, who provided expertise in sophisticated data science methods that allowed for generating deep insights into the issue in question. At the same time, Marco had a good idea of what information was actually relevant to the HR board member. As he told us with a smile, data scientists, in deep love with data and visualizations, would often craft diagrams with too much information. As a result, the job of the HRA team is to guide them how to shape dashboards relevant for decision-makers according to their information needs.

When crafting technical objects, establishing relevance was occasionally hindered as HRA team members had to handle dependencies. For instance, the blocking concepts enforced by data protection (see above) led to HR data scientists having full access to all HR data while members of the HRA team only had limited access. Team members were sometimes also dependent on technical experts that could, e.g. solve an issue related to a specific data base. As implied in the episode, constrained access to data again required boundary spanning practices for crafting technical objects in a relevant fashion. In the observation period before the board meeting, we noticed that suchlike dependencies jeopardized HRA practitioners delivering the right figure with the right numbers at the right time to important decision-makers. As indicates, HRA team members also had to consider political tensions when crafting technical objects. We will detail out this condition in the next subsection.

Rendering HRA outputs relevant by adjusting technical objects

After having processed technical objects–in most cases resulting in prototypes of analytical outputs–HRA team members turned to adjusting technical objects in accordance to the information needs of decision-makers, i.e. changing the shape of the analytical output in order to increase their relevance. The following episode illustrates how team members coordinate with other actors at TechCom to adjust technical objects.

Christopher receives a call from a colleague at the communications department. The quarterly board meeting is just two days ahead and there is still need to discuss some KPIs related to HR communication (showing, e.g., Twitter followers or how often board members get retweeted) in the board member dashboard. Christopher and the caller start discussions on whether certain function in the latest dashboard interface would actually provide value, especially for the HR board member, by recurrently putting themselves in their shoes. Christopher reminds the caller that the board member may not have much time, and yet he has to answer questions: ‘He wants to know: What is going well, what is going bad? Where do we have to act? And if we have only one dashboard for representing the issue, then we have to carefully consider the dramaturgy of the figures, we have to arrange them in a way that he easily understands the results’. He suggests: ‘We have this KPI here and this KPI here–and I would just merge them. The board members are supposed to be the target audience. I am not sure, if this is actually “board-relevant”’. Later he concludes: ‘I would just let the retweets-KPI where it is, because this indicates that our board members are very active and this is arguably an achievement related to one of our strategic goals’.

As illustrated by the episode, a first practice of adjusting technical objects is adapting outputs. Adapting outputs required a good share of business savviness on the side of the team members: Next to discussing the final dramaturgy of the dashboard elements, team members also chose a particular set of results and KPIs appearing as most relevant. Selecting, emphasizing, consolidating, or deleting information was usually based on the decision-makers’ perspectives gathered during the phase of reifying the epistemic object, their own expertise and experience, as well as correspondence with the strategic goals at TechCom.

Adapting outputs is closely connected to the epistemic practice of customizing dashboards. Here, the affordances of the epistemic technologies in place played a key role as they allowed the flexible adoption of the dashboard interface to customize analytical outputs towards the needs expressed by the HR board member. In accordance with the dramaturgy negotiated, for instance, team members added, changed, or deleted figures and graphics in dashboards or integrated specific functions (e.g. mouse-over or filter functions) in close cooperation with the AC to give the HR board member the possibility to explore the presented data on his own.

As indicated in the description of the setting at TechCom, another important epistemic practice is speaking a language of numbers. This required a good share of research and methods skills and, again, business savviness. The team members accomplished this by fine-tuning their analyses based on statistical methods and chose appropriate visualizations in the final dashboards (also see ‘crafting technical objects’ above). Speaking a language of numbers also enabled them to correspond to the surrounding data-driven culture and the preference for quantitative knowledge at TechCom. Another theme was HRA team members emphasizing the relevance of integrating financial data into the outputs. As several team members noted, showing financial impact is of particular relevance for attracting the board members attention, again allowing them to leverage the pronounced data-driven culture at TechCom. As Sabrina outlined:

If you want the attention of the board, you’ve got to speak their language. (…) I mean, HR is about the people, right? But if you can link People or HR Analytics to what does this mean in financial terms–then you have a totally different discussion base. (Sabrina, HRA team meember)

As already mentioned, political tensions sometimes hindered practitioners from rendering HRA outputs relevant in the course of adjusting technical objects and also when reifying technical objects (see above). Team members had to mediate between the interests of different CoEs and subsequently find compromises on how to present figures in the dashboards. This occurred, for instance, when single CoEs claimed to be underrepresented in the dashboards as compared to other CoEs. As two team members indicated in their interviews, CoEs sometimes try to circumvent analytical projects as they do not want certain things to be uncovered ‘in public’, making it difficult to access interesting and/or necessary data. In such cases, HRA team members had to balance between their professional view on how to craft rigorous and valuable outputs, and the political logic of the single CoEs. The features of the epistemic technologies allowing to customize the dashboards, again, played a key role in resolving such tensions. For instance, HRA team members balanced the number of KPIs between different CoEs to represent each in an appropriate proportion to others in the interface. From their professional view, however, this hindered them rendering HRA outputs relevant to the board member. Valeria remembered a recent iteration in the board member’s dashboard:

That was very big thing in the end, because we had to involve many, many political decisions. In other words, we couldn’t just say what we think makes sense, how we’d like it to make sense, which KPIs would make sense in the story flow. (Valeria, HRA team member)

Discussion and implications

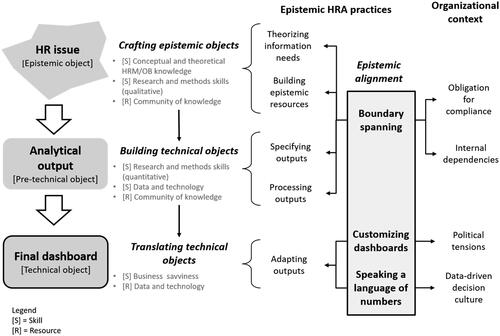

Using an HRM-as-practice lens, we illustrated how practitioners mobilized existing skills and resources in various epistemic practices to produce business relevant HRA outcomes. Based on these findings, we now theorize how HRA practitioners produce business relevant HRA outputs (see ) and unearth, against the background of extant literature, what skills and resources HRA practitioners mobilize in different phases of transforming epistemic objects to technical objects. These insights contribute to knowledge on how organizations can create effective HRA and illustrate how digitalization processes change the work of HRM in contemporary organizations.

Overall, we contend epistemic alignment, i.e. aligning to decision-makers’ perception of business reality when creating analytical outputs, as central mechanism in building business relevant HRA outputs in-practice. Epistemic alignment, accomplished through the epistemic practices of boundary spanning, customizing dashboards, and speaking a language of numbers, allows HRA team members for leveraging rich skills and resources in producing complex analytical outputs, while at the same time staying close to the decision-makers’ immediate business problems and accounting for conditions in the broader organizational context (e.g. compliance, dependencies, political tensions, and a data-driven decision culture). In the following, we detail out these practices and conclude with some practical propositions for each.

First, boundary spanning, i.e. linking the internal knowledge of the team with external sources (i.e. experts form the community of knowledge), was very present and important in the HRA practices observed, particularly in the phases of reifying epistemic objects and crafting technical objects. When reifying epistemic objects, the HRA practitioners established numerous touch points with their community of knowledge across diverse functional departments which presented a critical resource for creating business relevant outputs. To frame discussions with this community in a meaningful way, team members mobilized their knowledge on HRM/OB theory (e.g. by drawing on common theoretical concepts during the discussions) and well as a range of qualitative research and methods skills to effectively gather information on the requirements of the analytical outputs as well as the possibilities of creating them. These included finding and iteratively developing a suitable ‘sample’ of interview partners, preparing some targeted questions for the interviews, and inducting conclusions from the information gained. In the phase of crafting technical objects, team members mainly mobilized their quantitative research and methods skills when spanning boundaries to data scientists in the AC. This allowed the team members to integrate distributed expertise and skills in terms of methods and interpretation skills into the analytical process. Leveraging internal and external expertise from the community of knowledge further helped HRA teams to resolve, or at least anticipate, a broad range of functional, legal, technical, and political challenges associated with HRA project as well as to handle critical internal dependencies (e.g. in terms of data access).

In the light of extant literature, these findings confirm the importance of theoretical knowledge and research and methods skills as well as the resources of high-quality data, high-quality analytical technologies and access to a multi-disciplinary community of knowledge (Boudreau & Cascio, Citation2017; Levenson, Citation2017; Minbaeva, Citation2018; Rasmussen & Ulrich, Citation2015). What our findings add is showing how HRA practitioners mobilize conceptual and theoretical HRM/OB knowledge and their qualitative and quantitative research and methods skills to span productive connections to the community of knowledge. In the process of reifying an epistemic object, theoretical knowledge, research and methods skills, and access to a multi-disciplinary community of knowledge ensure effective knowledge generation on an HR issue at hand which presents an important basis for crafting business relevant outputs. Based on this, we propose:

Proposition 1: Generating business relevant HRA outputs requires effective boundary spanning on the side of an HRA team. Effective boundary spanning can be accomplished by mobilizing a) knowledge on HRM/OB theory b) qualitative and quantitative research and methods skills, and c) access to a multi-disciplinary community of knowledge.

In the phase of adjusting technical objects, the epistemic practices of customizing dashboards and speaking a language of numbers were very present. By customizing dashboards, team members adapted analytical outputs towards the needs expressed by the HR board member, ensuring compliance, and balancing political tensions (especially between different CoEs). Here, team members primarily mobilized their business savviness and the resources of high-quality data and analytics technology. When adapting technical objects, practitioners also leveraged a language of numbers in terms of providing sophisticated statistical outputs as well as integrating financial indicators in the outputs.

These findings are consistent with extant HRA literature suggesting that high-quality data and analytical technologies and business savviness are critical to ensure effective HRA (e.g. Angrave et al., Citation2016; Minbaeva, Citation2018). Our findings add two important nuances. First, they highlight the central role of the epistemic technologies’ particular features with regards to their adaptability, that is, the possibilities to adapt and exchange different elements in the visualization of analytical outputs (such as figures and diagrams). These features, on the one hand, allowed to align the data outputs in accordance to the needs of the decision-makers as well as to conditions in the wider organizational contexts (particularly political tensions). On the other hand, adaptability affordances turned out as important in the iterative and experimental process of transforming epistemic objects to technical objects: As apparent in many meeting discussions, complex analytical projects required a constant back-and-forth to explore what results are the most relevant to decision-makers and much experimentation how to present them in the best way. Based on this, we argue:

Proposition 2: Generating business relevant HRA outputs requires an HRA team having the ability to customize analytical outputs and speaking a language of numbers. This requires HRA team members to mobilize a) quantitative research and methods skills b) analytical technologies that allow for adapting analytical outputs in accordance to decision-makers’ information needs and conditions in the organizational context (e.g., compliance issues or political tensions) and b) business savviness for relating HRA outcomes to financial outcomes.

Our findings further add that speaking a language of numbers is tightly connected to a data-driven decision culture present in the wider organizational context (also see Minbaeva, Citation2018). In the case of TechCom, there was a general obligation to use data for decisions, creating norms of knowledge creation and usage at TechCom (Feldman & March, Citation1981). HRA practitioners, in accordance, strongly attended to this data-driven culture by applying complex quantitative methods and speaking a language of numbers, particularly in financial terms, when creating analytical outputs. This resulted in an interesting interplay: The prevailing culture not only obliged the HR function to speak a language of numbers but also created a favorable, ‘absorptive’ environment for HRA as it also obliged decision-makers at TechCom to use the HRA outputs created by the team. In summary, this cultural obligation created a high level of legitimacy for the HRA at TechCom.

Limitations and future research

Next to the usual limitations of a single case study approach (limited generalizability and construct validity) we see two further important limitations of our approach, paving some avenues for future research. First, albeit we have shown how HRA team members shape HRA outputs in accordance to prior inputs of decision-makers, we still know little about how decision-makers assess the analytical outputs and how they use them. Future research could thus shed light on whether and how this group integrates HRA outputs into their decision-making. This integration may look very different for managers at different levels (e.g. line managers at different levels, heads of the CoEs, board members, etc.). Further, the role of HRBPs in these integration processes is yet to discover. Putting more attention to the role of decision-makers in HRA may also give answers to the question whether practicing HRA conveys a raise in the power and status of HRM in an organization (Greasley & Thomas, Citation2020). While our data indicates an overall positive perception and recognition of the HR function at TechCom, open questions remain to what extent HRA affects the power and status of the HRA team itself and how this feeds back into the certain groups of HR practitioners (e.g. HRBPs), the organizational HRM function, and the field of HRM in general.

Second, the HRA team studied was equipped with a particular set of skills and resources critical for building effective HRA. However, HRA practitioners across organizations may not hold the same set of skills and may not be provided with the same set of resources. In future research, integrating HRA teams in different organizations and applying a configurational perspective could shed light on what skills, resources, practices, and contextual factors actually matter. A configurational approach would particularly allow for identifying configurations of skills, resources, practices, and contextual factors that–as a bundle–increase the chances of the respective HRA practitioners to generate business relevant HRA. These configurations or bundles denote multidimensional constellations of ‘conceptually distinct characteristics that commonly occur together (…)’ (Meyer et al., Citation1993, p. 1175). From these consistent configurations of skills, resources, practices, and contextual factors, typically those linked to favorable outcomes (like business relevant HRA) can be identified. In this way, interactions of various important factors for building business relevant HRA by means of HR-related technology can be considered (Strohmeier & Kabst, Citation2014).

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (18.4 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the HR Analytics team presented in this paper for inviting us to data collection. We also thank the two anonymous reviewers and the editors of this special issue for their constructive criticism and suggestions. Further, we want to thank the attendees at various conferences and workshops where we presented earlier versions of the paper and especially to Ewald Kibler (Aalto University) for his vital input and feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

Supplemental data for this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2021.1886148. The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, ME. The data are not publicly available due containing information that could compromise the anonymity and privacy of research participants.

References

- Angrave, D., Charlwood, A., Kirkpatrick, I., Lawrence, M., & Stuart, M. (2016). HR and analytics: Why HR is set to fail the big data challenge. Human Resource Management Journal, 26(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12090

- Anthony, C. (2018). The question or to accept? How status differences influence responses to new epistemic technologies in knowledge work. Academy of Management Review, 43(4), 661–679. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2016.0334

- Barbour, J. B., Treem, J. W., & Kolar, B. (2017). Analytics and expert collaboration: How individuals navigate relationships when working with organizational data. Human Relations, 90(10), 1–29.

- Björkman, I., Ehrnrooth, M., Mäkelä, K., Smale, A., & Sumelius, J. (2014). From HRM practices to the practice of HRM: Setting a research agenda. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, 1(2), 122–140. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JOEPP-02-2014-0008

- Bondarouk, T., Parry, E., & Furtmueller, E. (2017). Electronic HRM: Four decades of research on adoption and consequences. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(1), 98–131. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1245672

- Bondarouk, T., & Ruël, H. J. M. (2009). Electronic human resource management: Challenges in the digital era. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 20(3), 505–514. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190802707235

- Boudreau, J., & Cascio, W. (2017). Human capital analytics: Why are we not there?Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, 4(2), 119–126. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JOEPP-03-2017-0021

- Corbin, J. M., & Strauss, A. (1990). Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology, 13(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00988593

- Davenport, T. H. (2006). Competing on analytics. Harvard Business Review, 1–10.

- Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532–550. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1989.4308385

- Ellmer, M., & Reichel, A. (2018). Unpacking the “e” of e-HRM: A Review and Reflection on Assumptions about Technology in e-HRM Research. In: Stone, D. & Julebohn, J., The Brave New World of eHRM 2.0, Information Age Publishing, 247–278.

- Feldman, M. S., & March, J. G. (1981). Information in organizations as signal and symbol. Administrative Science Quarterly, 26(2), 171–186. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2392467

- Feldman, M. S., & Orlikowski, W. J. (2011). Theorizing practice and practicing theory. Organization Science, 22(5), 1240–1253. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1100.0612

- Gioia, D. A., Corley, K. G., & Hamilton, A. L. (2013). Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research. Organizational Research Methods, 16(1), 15–31. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428112452151

- Greasley, K., & Thomas, P. (2020). HR analytics: The onto‐epistemology and politics of metricised HRM. Human Resource Management Journal, 39(2), 1–14.

- Kaplan, S. (2011). Strategy and PowerPoint: An inquiry into the epistemic culture and machinery of strategy making. Organization Science, 22(2), 320–346. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1100.0531

- Knorr Cetina, K. (1999). Epistemic cultures: How the sciences make knowledge. Harvard University Press.

- Knorr Cetina, K. (2005). Objectual practice. In T. Schatzki, K. Knorr Cetina, & E. v. Savigny (Eds.), The practice turn in contemporary theory (pp. 184–197). Routledge.

- Legge, K. (1978). Power, innovation, and problem-solving in personnel management. McGraw-Hill.

- Levenson, A. (2017). Using workforce analytics to improve strategy execution. Human Resource Management, 49(1), 49.

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. SAGE.

- Marler, J. H., & Boudreau, J. W. (2017). An evidence-based review of HR Analytics. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(1), 3–26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1244699

- Meyer, A. D., Tsui, A. S., & Hinings, C. R. (1993). Configurational approaches to organizational analysis. Academy of Management Journal, 36(6), 1175–1195.

- Minbaeva, D. B. (2018). Building credible human capital analytics for organizational competitive advantage. Human Resource Management, 57(3), 701–713. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21848

- Parry, E. & Strohmeier, S. (2014). HRM in the digital age – digital changes and challenges of the HR profession. Employee Relations, 36(4). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-03-2014-0032

- Peeters, T., Paauwe, J., & Van De Voorde, K. (2020). People analytics effectiveness: developing a framework. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, 7(2), 203–219. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JOEPP-04-2020-0071

- Rasmussen, T., & Ulrich, D. (2015). Learning from practice: How HR analytics avoids being a management fad. Organizational Dynamics, 44(3), 236–242. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2015.05.008

- Strohmeier, S., & Kabst, R. (2014). Configurations of e-HRM – An empirical exploration. Employee Relations, 36(4), 333–353. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-07-2013-0082

- van den Heuvel, S., & Bondarouk, T. (2017). The rise (and fall?) of HR analytics. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, 4(2), 157–178. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JOEPP-03-2017-0022

- van der Laken, P. A. (2018). Data-driven human resource management: The rise of people analytics and its application to expatriate management. Ridderprint BV.