Abstract

Despite redundancies having far reaching consequences for organisations, relatively limited attention has been paid to the conflicting experiences of those implementing the redundancy process; the redundancy envoys. By drawing on theories of cognitive dissonance and ‘dirty work’ we explain how individuals implementing redundancies can experience a disconnect between their outward and inner emotions. We reconceptualise redundancy envoys as quasi-dirty workers as they intermittently perform ‘dirty work’ tasks that may be perceived as morally tainted, whilst recognising their conventional role incorporates tasks perceived as contrary to that of ‘dirty work’. Our study draws on insider research access to redundancy envoys over a five-year period during the implementation of four consecutive redundancy programmes, providing the opportunity to observe decisions and actions in ‘real time.’ We offer a contemporary reconceptualisation of the redundancy envoywhich permits a deeper understanding of the negative impact on redundancy envoys and offers opportunities to examine how this can be reduced. In addition, it is anticipated that the results of this study will offer support to HR functions in reducing the stigma of ‘dirty work’ for redundancy envoys with the intention of enhancing the management of redundancy implementation.

Introduction

In today’s volatile business environment, redundancies are well established as a key component of management practice (Wilkinson, Citation2005). The Covid-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on the global scale of redundancies despite government schemes to limit job losses (Petzer, Citation2020). Yet despite the popular strategy of implementing redundancies as a method to save costs (Gandolfi & Hansson, Citation2011; Schoenberg et al., Citation2013), studies indicate that redundancies rarely lead to better financial performance or improved productivity (Cascio, Citation2013). Luan et al. (Citation2013) contend that implementing redundancies during an economic downturn can have a further negative impact on organisational performance and thus redundancies should be approached with caution and moderation, particularly as redundancies have long-term impact at the organisational and individual level (Quinlan & Bohle, Citation2009).

There are three groups of employees impacted by redundancies; victims, survivors and redundancy envoys. Victims are the ex-employees who have been unsuccessful in remaining employed by the organisation and as a result have been made redundant. Survivors are the individuals that remain in the company during and after the redundancy programme (Baruch & Hind, Citation1999). Literature on redundancies is replete with studies examining the impact on victims (Clair & Dufresne, Citation2004; Parris & Vickers, Citation2010; Waters, Citation2007) and survivors (Allen et al., Citation2001; Bergström & Arman, Citation2017; Brockner, Citation1996; Tal, Citation1996 and Tourish et al., Citation2004). Some of the adverse psychological effects includes; ill health, family problems, marital problems, lower self-esteem, stress and depression, ill health and feelings of social isolation (Gandolfi, Citation2008b; Greenglass & Burke, Citation2001; Vickers & Parris, Citation2007).

The survivors of an organisational restructure often experience the adverse effects of being subjected to the process as profoundly as those who were made redundant. This typically includes feelings of anger, anxiety, cynicism, resentment, resignation and retribution (Brockner, Citation1992; Baruch & Hind, Citation1999) unfairness, guilt, job insecurity and relief (Brockner et al., Citation1988). Other reported consequences of redundancies on survivors include reduced career consciousness (Freeman,Citation1994), reduced organisational commitment (Freeman & Cameron, Citation1993; Littler & Innes, Citation2003) and stress (Nicholas et al., Citation1998). Survivor behaviour also includes increased levels of absenteeism (Campbell-Jamison et al., Citation2001; Nicholas et al., Citation1998) and less innovation (Cascio, Citation1993). When it comes to the impact on redundancy envoys, literature is limited in comparison to the substantial body of work that focusses on victims and survivors.

Our study contributes to knowledge by focussing on professionals, and their experiences of acting as a redundancy envoy. Being a redundancy envoy is often one of the tasks of the Human Resources (HR) function; it is holding the responsibility of directly conveying the bad news of job losses as a result of redundancies. In addition to the HR function, acting as a redundancy envoy can form part of the roles of directors, line managers and employee consultative representatives.

HR is associated with driving talent and financial outcomes as a strategic partner (CEB, Citation2014; Geimer et al., Citation2017). It has developed as a function to be more focussed on acting as a member of the senior management team in making major business decisions (Boudreau & Ramstad, Citation2007; Lawler III & Boudreau, Citation2009). Directors and managers are often perceived by individuals and peers as the drivers of success (Kets De Vries & Balazs, Citation1997) and strategic change (Åberg & Torchia, Citation2020; Haynes & Hillman, Citation2010) to improve competitive advantage in terms of the organisation’s survival (Agarwal & Helfat, Citation2009; Augier & Teece, Citation2008). In acting as a redundancy envoy conflicting roles emerge, whereby an individual who previously had the responsibility of building an organisation and providing a vision for the future (Cameron et al., Citation1993; Kets De Vries & Balazs, Citation1997) now has to adopt a role of discarding these values with reduced leader credibility (Cameron et al., Citation1987).

We therefore provide evidence to support the implementation of redundancies as being conceptualised as ‘dirty work’ tasks and discuss the consequences for organisations and individuals of this conceptualisation. Recognising that the role of redundancy envoy forms only part of a professional role, we posit that redundancy envoys are quasi-dirty workers, adopting a ‘dirty work’ task perspective rather than a fully-fledged ‘dirty work’ occupation (Baran et al., Citation2012). Due to the episodic nature of acting as a redundancy envoy, we argue that cognitive dissonance can arise in redundancy contexts due to redundancy envoys having to deliver the message of redundancies with a smile, portraying confidence in the decision, whilst experiencing a different internal emotion when they don’t agree with the decision on a personal level. We argue that the intermittent nature of the role and its ‘dirty work’ connotations exacerbate the experiences of cognitive dissonance by redundancy envoys. Often depicted as a ‘smiling assassin’ by those being put at risk of redundancy, and as per Hughes (Citation1962) observations of ‘dirty work’, because organisations often delegate the task of communicating redundancies to individuals, it is redundancy envoys who may experience stigmatisation. We thus contend that when managers, directors, HR and employee representatives adopt the role of redundancy envoy, they perform ‘dirty work’ tasks (Baran et al., Citation2012) that may be perceived as physically, socially or morally tainted. In contrast, other tasks outside of the redundancy role carry no ‘dirty work’ stigma (Kreiner et al., Citation2006). We therefore argue that redundancy envoys are quasi-dirty workers, akin with being ‘partly, but not really’ or ‘seemingly’ ‘dirty workers, as their occupation is not normally that of a ‘dirty worker’ but does reflect characteristics of ‘dirty work’ tasks when implementing redundancies (Baran et al., Citation2012).

Our study makes an important contribution by examining the dichotomy of opposing cognitions experienced by redundancy envoys fuelled by the stigma of conducting ‘dirty work’ tasks. The impact of these experiences is of particular importance as the stress and anxiety caused by implementing redundancies can be mitigated, which could lead to a more effective HR strategy as a critical factor for successful redundancy implementation (Cameron, Citation1994). Research on redundancy envoys is under-developed, and so developing a contemporary understanding of their experiences is important and valuable as their methods can influence the success of a redundancy programme (Wright & Barling, Citation1998; Clair & Dufresne, Citation2004; Ashman, Citation2016).

The paper commences with an overview of the role of the redundancy envoy, followed by the theoretical positioning of the study. We next outline our research design and the subsequent section presents the results of a five-year qualitative longitudinal study. Next, we discuss the adverse impact on redundancy envoys and how this informs the reconceptualisation of redundancy envoys as ‘quasi-dirty workers’ as well as how the cognitive dissonance experienced may be mitigated, prior to offering implications for theory and recommendations for practice.

Idiosyncrasy of the redundancy envoy

Redundancy is not a new phenomenon (Baruch & Hind, Citation1999). Concerned with the dismissal of an employee due to the cessation of an operation, change of business location or no further demand for a particular type of role, the management strategy of restructuring, often resulting in redundancies, has been used globally for more than two decades (Gandolfi, Citation2009; Williams, Citation2004; Allen et al., Citation2001; Orlando, Citation1999; Tourish et al., Citation2004). The objectives of redundancies are to promote organisational efficiency, productivity and improve market competitiveness by making changes that positively impact costs and align the business with the changing economy, such as reducing the size of the workforce and/or restructuring to lower overhead costs (Allen et al., Citation2001; Cameron, Citation1994; Gervais, Citation2014; Burke, Citation2009). Despite these reported organisational benefits, redundancies have a severely negative impact on all of an organisation’s workforce.

In redundancy lexicon, the following labels are used to describe the incumbents of the role of implementers of redundancies; executioners (Kets De Vries & Balazs, Citation1997; Gandolfi, Citation2006), executors (Downs, Citation1995), downsizers (Burke, Citation2009) and downsizing agents (Clair & Dufresne, Citation2004). Ashman (Citation2012a, Citation2012b, Citation2015) however argues that ‘redundancy envoy’ is more in keeping with the experience of being an agent, messenger or diplomat when delivering the implementation of redundancies. Ashman (Citation2012b) postulates that the term of ‘executioner’ is inaccurate and unfair as the role of the occupant requires sensitivity, resilience and discretion, whereas the term ‘executioner’ implies skills associated with using an axe or a noose. Gandolfi (Citation2009) suggests that the definitions of executioners are broad and include responsibilities associated with formal redundancy implementation. Our research therefore adopts the terminology of redundancy envoy as used by Ashman (Citation2012a, Citation2012b, Citation2016), as it reflects the role of a messenger, with a further distinction to the label ‘executioner’ in that redundancy envoy roles are different as their proximity to the affected employees in delivering the message is typically on a one-to-one basis. Research by Kets De Vries and Balazs (Citation1997) refers to executives, such as directors or owners of an organisation. Their role in redundancy implementation is generally different to the majority of redundancy envoys as they are typically responsible for the decision making in implementing redundancies and may be involved in the overall announcement to the affected employees. Executioners’ exposure to the ‘dirty work’ tasks is thus short lived and limited. We argue that redundancy envoys own a significant weight of ‘dirty work’ tasks in comparison during redundancy implementation. A further distinction between the term executioner and redundancy envoy is that our research includes employee representatives as part of the classification of redundancy envoy.

Research on redundancy envoys is limited, with the current body of knowledge being predominantly more than fifteen years old, with notable exceptions including the work of Gandolfi (Citation2008a; Citation2008b), Kets De Vries and Balazs (Citation1997) and Torres (Citation2011), which focuses on the negative consequences and importance of executives in the success of implementing redundancies. Ashman’s (Citation2012a, Citation2012b, Citation2016) work is also a notable exception wherein he explored redundancy envoys in the public sector (2012a, 2012b) and undertook a comparative study between public and private sector envoys in 2016 across a range of organisations. Our research extends Ashman’s (Citation2012a, Citation2012b, Citation2016) work by exploring the experiences of redundancies in the private sector from an insider perspective during the course of four consecutive redundancy programmes. Gandolfi and Hansson (Citation2011, Citation2015) explore the non-financial consequences of implementing redundancies with a strong focus on the HR impact. We build on this work by gaining the unique insider perspective of redundancy envoys and by including employee representatives. Arguably, recent literature by Rook et al. (Citation2019) that addresses stress in senior executives is relevant to directors adopting the role of redundancy envoy. However, this research is not specifically aimed at examining the stress experienced during the implementation of redundancies and hence we complement this research with our specific focus on stress during redundancy implementation. Previous studies have recognised the specific role of HR in the implementation of redundancies (Sahdev et al., Citation1999), the overall importance of HRM and knowledge management (Edvardsson, Citation2008) and specifically HR as a strategic partner during change management programmes such as redundancies (Lemmergaard, Citation2009). More recently research has been conducted on the bundles of HR practices adopted during recessions (Teague & Roche, Citation2014) and the impact of different high-performance working systems as part of a HR strategy (Cregan et al., Citation2021) and their relationship with successful redundancy outcomes. Our research reinforces and highlights the specific importance that HR has in limiting the cognitive dissonance experienced for all the categories of redundancy envoys as part of its role as strategic partner. Interesting new research has emerged from McLachlan et al. (Citation2021) that is novel in the inclusion of employee representatives in a case study of the impact on redundancy victims, survivors and ‘endurers’, however it is not specific to redundancy envoys. In addition, Bergström and Arman (Citation2017) research has also highlighted the important role of employee representatives in their role of redundancy envoys during the implementation of redundancies.

Theoretical positioning of the study

The term ‘dirty work’ is commonplace in today’s society (Ashforth et al., Citation2007) and is argued to be a necessary evil (Kreiner et al., Citation2006). Literature on the stigma of ‘dirty work’ tends to focus on how stigmatised occupations cope (Ashforth & Kreiner, Citation1999; Bolton, Citation2005; Simpson et al., Citation2012). The mitigation of the occurrence of the ‘dirty work’ stigma has also been explored (Devers et al., Citation2009; Helms & Patterson, Citation2014). Zhang et al. (Citation2021) define six sources of stigma: physical, tribal, moral, servile, emotional and associational. We contribute to knowledge specifically in the category of the ‘emotional’ stigma associated with ‘dirty work’ tasks. Emotional stigma is defined as the requirement to engage with burdensome and threatening emotions (Zhang et al., Citation2021). Emotional stigma presents as emotional labour which is socially constructed along with ‘dirty work’ (Rivera, 2015). Emotional labour refers to emotions that are perceived outwards, including smiling, or a lack of emotional demonstration whilst felt emotions are experienced, such as regret (Hochschild, Citation1983; Rivera, Citation2015). Emotional stigma is assigned to occupations that are defined as ‘dirty work’ due to their proximity to negative emotions when working with people who are upset or abusive (Zhang et al., Citation2021). McLoughlin’s (Citation2019) work demonstrated that the burden of the emotional stigma could lead to a negative impact on the individual’s wellbeing. We build on ‘dirty work’ research, by extending the perspective of Baran et al. (Citation2012)’s work that posits how roles that are not typically defined as ‘dirty work’ occupations yet include ‘dirty work’ tasks are still exposed to stigmatised scrutiny which causes cognitive dissonance for the incumbents.

Whilst often having little in common, stigmatised occupations do share a ‘visceral repugnance’ (Ashforth & Kreiner, Citation1999, p. 415), which has implications for ‘dirty workers’ and roles that require episodic ‘dirty work’ tasks. A further distinction to note is that implementing redundancies ‘is an activity that contradicts their basic outlook towards business life’ (Kets De Vries & Balazs, Citation1997, p. 17) as executives are responsible for employee engagement, improved financial performance (Harter et al., Citation2002) and organisational culture (Hartnell et al., Citation2016; Yanchus et al., Citation2020); elements that conflict with the implementation of redundancies. Role conflict when implementing ‘dirty work’ tasks may be an additional burden for redundancy envoys in comparison to ‘dirty work’ occupations that do not comprise a dual role. A re-examination of redundancy envoys as quasi- ‘dirty workers’ conducting ‘dirty work’ tasks therefore appears timely as organisational studies on ‘dirty work’ often neglect to reflect the changes in the demand and nature of occupations (Ashforth & Kreiner, 1999, Simpson, Slutskaya, Lewis & Höpfl, Citation2012).

As per the concept of cognitive dissonance, redundancy envoys may be adept at displaying a different emotion to that which they feel. When an individual holds two or more elements of knowledge that are relevant to each other but inconsistent with one another, a state of discomfort is created. This unpleasant state is referred to as ‘dissonance’ (Harmon-Jones & Harmon-Jones, Citation2008, p. 1518). Cognitive dissonance theory researchers have argued that the existence of needs is presented through external justification (Aronson, Citation1969; Festinger, Citation1957), which influences the cognitive dissonance experienced and results in motivational changes in attitude (Aronson, Citation1969; Wan & Chiou, Citation2010). Redundancy envoys experience cognition or attitude in accordance to the extent to which they feel personally responsible for the task they are performing (Cheng & Hsu, Citation2012). Should the task be of a negative consequence, such as implementing redundancies, redundancy envoys are bound to experience dissonance, regardless of whether the situation could have been reasonably avoided (Goethals et al., Citation1979).

Contemporary studies are in short supply, yet contrary to the negative indications discussed previously, there is some evidence in the literature to suggest some positive outcomes for redundancy envoys. For example, studies have found that redundancy envoys expressed optimism as tough decisions were made and there was a belief that the organisation was on a road to recovery (Sahdev et al., Citation1999). A study by Papalexandris (Citation1996) proposed that HR managers are key in handling redundancies and driving competitiveness in larger firms, and that their joint responsibility with line managers is critical during the difficult task of implementing redundancies. Research by Van Dierendonck and Jacobs (Citation2012) positions the importance of redundancy envoys in the redundancy process as they have a direct impact on how fairness and justice is perceived by victims and survivors and can therefore influence motivation. Redundancy envoys have been described as unsung corporate heroes who try to limit the negative impact on victims during major change programmes (Frost, Citation2003), and who can help to enrich jobs and keep people motivated during restructures by encouraging employees to develop a more positive approach to lateral career development (Holbeche, Citation2009).

It is therefore important to understand the experiences of redundancy envoys as their perceptions are different and distinct (Clair & Dufresne, Citation2004) and they largely adopt more than one role; that of survivor and change agent (Dewitt et al., Citation2003). Utilising and combining the theories of ‘dirty work’ and cognitive dissonance allows us to understand the external and internal experiences of redundancy envoys; whether they are perceived as tainted by a critical mass and/or personally, and whether they experience a disconnect between the emotions they portray and those that they genuinely feel. Redundancy envoys are likely to have a pivotal impact on the success and outcomes of the redundancy strategy as well as on employees’ reactions (Gandolfi, Citation2006, Citation2008a, Citation2008b; Dewitt et al., Citation2003; Kets De Vries & Balazs, Citation1997).

Development of research questions

To begin to develop a contemporary understanding of the impact of redundancy on those that are implementing the process we use the following research questions to frame our study:

How can ‘dirty work’ be reconceptualised to recognise the ‘dirty work’ tasks carried out as part of the role of redundancy envoy?

How can cognitive dissonance experienced through the role of redundancy envoy be mitigated?

Research methodology

As there are limited contemporary studies examining the redundancy process from the perspective of the redundancy envoy, we adopt a qualitative research design that permits the collection of rich data from different sources (Remenyi et al., Citation1998; Trowler, Citation1998). We draw on data collected from redundancy envoys across a range of different industries, including engineering, healthcare, technology, transportation, construction and retail. represents the roles, codes and typical areas of responsibility in redundancy implementation.

Table 1. Responsibility remit of redundancy envoys.

We also present data collected from a five-year longitudinal study conducted within a multinational engineering conglomerate. The longitudinal study examines the impact of four consecutive redundancy programmes from the perspective of the redundancy envoys implementing these programmes. The first author of the paper was employed as a Human Resource Business Partner (HRBP) within the multinational engineering conglomerate that is the subject of examination and acted as an insider researcher. As with previous studies that have utilised insider research (Breen, Citation2007; Unluer, Citation2012), holding a position within the organisation being researched allowed the researcher to develop trusting relationships with participants, and to cause minimal disruption to normal activities (Bonner & Tolhurst, Citation2002; Ryan, Citation1993). Further, being an insider researcher provided the opportunity to observe and to ask questions about behaviours, and to subsequently make sense of these observations (Coghlan et al., Citation2016). Insider research offers several benefits to qualitative studies including having a greater understanding of culture and exploring the process of practice rather than simply its outcome (Reed & Proctor, Citation1995; Pugh et al., Citation2000). Studies have questioned the dichotomy of the ‘insider/outsider’ researcher and suggest that this distinction is overly simplistic, and a continuum is more accurate whereby the researcher is sometimes on the inside and sometimes on the outside (Breen, Citation2007). This is a helpful conceptualisation for research, yet for our study the researcher was predominantly on the ‘inside’ as her role comprised that of redundancy envoy and, somewhat ironically, her position was put at risk of redundancy during a restructuring of the HR department. This experience afforded a very valuable and unique perspective and insight into what it feels like as an employee when your ability to generate an income in your current role is threatened. Not only was it a challenging situation due to the threat of losing income, but even more significantly so due to the insider researcher being the main breadwinner in the household and pregnant with her second child. The researcher therefore identified as being on the inside, and this perspective is adopted throughout the longitudinal study.

Data collection

The insider researcher used multiple methods of data collection (Berg, Citation2001; Patton, Citation2002) to gain a greater understanding of the cognitive dissonance and perceptions of ‘dirty work’ tasks experienced. These included in depth interviews and the capturing of field notes through diary keeping by noting daily events and observations from meetings (Etherington, Citation2004; Maykut & Morehouse, Citation1994; Strauss & Corbin, Citation1998) as well as secondary data collected through an organisation wide online ‘Mood Board’. To ensure accuracy, validity, reliability and transferability of data, researcher interpretations were cross checked with the participants through follow-up interviews (Maykut & Morehouse, Citation1994). Finally, all participants received a copy of their transcribed interviews for accuracy and further comments. The study was conducted in two stages:

Stage one: understanding cognitive dissonance experienced through interviews

A broad sample of 17 redundancy envoys working in aviation, transportation, logistics, education, engineering, manufacturing, cosmetics, automation, technology and hospitality were selected using criterion sampling (Patton, Citation2002). The criterion was that all participants must have previous experience in the active implementation of redundancies, which included being classed as a redundancy envoy. Semi-structured interviews were used, with questions that drew on the theoretical focus of the study, thus enabling our understanding of the cognitive dissonance experienced by redundancy envoys and to what extent they perceive themselves, and are perceived by others, as conducting ‘dirty work’ tasks. Interviews were conducted over a 12-month period, lasting on average one half to two hours, and were recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Stage two: longitudinal study as insider researcher

The longitudinal research was conducted in a division of a large, global engineering conglomerate. This organisation had experienced a series of four redundancy programmes, primarily driven by a need to improve efficiency and productivity. During the four redundancy programmes, data were collected from the impacted workforce to inform the extent to which ‘dirty work’ was perceived and observed. Phase 1 of the business restructuring occurred between November 2011 and April 2012 when two businesses were merged. This was followed by Phase 2 from November 2012 to April 2013 when duplicate processes and positions were removed from the merged businesses. A further restructuring, Phase 3, took place between April–July 2013 with the final phase, Phase 4, driven by profitability targets and carried out between August 2013 and January 2014.

The second stage of data collection was thus focussed on gaining a deeper insight into the real experiences of being a redundancy envoy in the field. Longitudinal data were collected over a period of five years using the following methods:

Semi-structured interviews

Critical ethnography: Author diary keeping/observation

Comments from the organisational Mood Board

Semi-structured interviews

During the five years as an insider researcher, semi-structured interviews were undertaken with the redundancy envoys specific to the four redundancy programmes implemented in the organisation. Participants were therefore selected based on their knowledge and experience of redundancies (Bernard, Citation2002). As the lead author had a long-standing career as a HR professional, access to participants was not a significant challenge. Semi-structured interviews were the main source of data and a further 19 participants were interviewed from the organisational setting; totalling 36 participants across stages 1 and 2 of the research comprising of a further nine HR professionals, six HR directors, 10 line managers, seven organisation directors and four employee representatives. The scale of the global organisational setting allowed for interviews to take place with participants who had redundancy experiences from various countries including UK, Switzerland, Canada, South-Africa, United Arab Emirates, Poland, Germany, France and America. Interviews lasted approximately one and half to two hours and several participants had 2nd interviews for more focussed discussion. With the combination of 2nd interviews, some interviews lasted up to four hours. Interviews were mostly conducted face to face, however due to the international component, some interviews took place via phone and video conferencing. All interviews were recorded with consent and transcribed verbatim, with participants validating transcripts once complete.

Critical ethnography

The researcher kept a diary of field notes and observations in Afrikaans, the first language of the insider researcher, to protect the data. This allowed notes to be taken more freely when in close proximity to colleagues. Trowler’s (Citation1998) work on ‘academics responding to change’ influenced the researcher positively on the approach and benefits of qualitative data and using in-depth analysis to make sense of the data, complementing the data collected from interviews. The observations and notes from diary keeping gave context and meaning when following up with semi-structured interviews and focussing questions to mitigate underlying assumptions.

Comments from the organisation’s mood board

The Mood Board was used as a secondary data collection method that captured the perceptions of employees. By using a digital platform, employees had the opportunity to provide anonymous qualitative feedback on how they felt, what concerned them and what made them happy whilst being impacted by the redundancy programmes. Sixty-six random employees were invited on a weekly basis to post feedback. The average response rate was around 50%, indicating that nominally there is a response from approximately thirty-three employees per week. Over the course of the study, a total of 2033 comments were analysed.

Data analysis

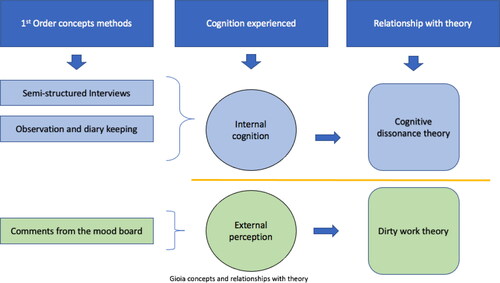

Throughout the two phases of the research design, as detailed below in , we drew on Gioia et al. (Citation2013) work to develop our data structure and analysis.

Synchronous to data collection during stage 2, and subsequent to the first stage of analysis of data collected in stage 1, first order concepts were developed (Gioia et al. (Citation2013). This led to the identification of 2nd order themes informing potential new domains and eventually the formation of aggregate dimensions (Gioia et al., Citation2010). Our interpretive approach comprised of concurrently collecting and analysing data, whilst interviewing new participants. Trustworthiness of data was achieved by deploying Lincoln and Guba (Citation1985) criteria of peer debriefing, where one author (insider) had responsibility for collecting data whilst the second author (outsider) adopted a more general formulation, challenging alternative explanations.

Results

Our data indicate that the negative impact on redundancy envoys is significant and that cognitive dissonance is experienced repeatedly by those who have to deliver the bad news of job losses, whilst not being able to show their true cognition of self-doubt and low morale. We explore the negative and positive cognitions that led to dissonance and discuss this within the context of ‘dirty work’ tasks.

Evidence of negative internal cognition and cognitive dissonance

We identify four negative internal cognitions (see ) which manifested in different behaviours and affected the health of respondents; stress and anxiety, empathy, doubt and insecurity, and guilt.

Table 2. Cognitive dissonance data structure.

Stress and anxiety

From our study the redundancy envoys unanimously agreed that they suffered high levels of stress and anxiety as a result of the implementation of redundancies. The most prevalent reason for this was the on-going experience of conflicting cognitions; for example, redundancy envoys experienced dissonance between their internal emotion and that emotion which they felt compelled to portray in their professional role. This Head of Business Excellence felt exhausted due to pressure and subsequently applied for voluntary redundancy as he felt he had enough:

‘As a big manager in a big business [implementing redundancies] is like failure and I felt the pressure on-a-day-to-day basis. I felt that 6–9 months additional pressure. It drains your energy and you felt tired in a business like this. It sucks the life out of you’ (I-OD).

Empathy

The personal impact of absorbing the negative emotions of the victims was a challenge for redundancy envoys due to the emotional impact of the empathy that they felt. This resulted in redundancy envoys experiencing unpleasant internal conflict by doing a task that they had to do and that was right for the organisation’s survival, yet caused a feeling that was contradictory to ‘doing’ the right thing;

‘putting people at risk of redundancy, at best, is a horrible thing to do’ (I-LM).

Redundancy envoys appeared to be overwhelmed with the personal negative impact that they experienced, declaring a loss of personal and emotional control, often resulting in tears during conversations and interviews;

‘I do not know if I am coming or going, yet, I have to continue with this dysfunctional working’ (DO-LM).

Redundancy envoys vicariously felt the pain and suffering of their victims. It is not an everyday task for managers and HR professionals to cause such significant, disruptive damage to employees’ psychological wellbeing and thus when they step into the role of redundancy envoy, the realisation of the shock of the damage causes a sensation of ‘pain’ for redundancy envoys;

‘It is terrible. It is a sick feeling and very painful when you realise the impact on people with redundancy’ (I-OD).

Some redundancy envoys experienced the destruction of their employees’ livelihoods to such a severe extent they even intimated toward self-destruction such as this envoy who stated;

‘Sometimes, when I drive to work, I think that if I just make a mistake on the road, I can stop this pain’ (DO-LM).

Such quotes highlight the often unrecognised, inner turmoil being felt by the redundancy envoys empathising with those receiving news of job losses.

Doubt and insecurity

Through the process of implementing redundancies, envoys were doubting their own actions. This doubt, experienced internally, impacted on their professional confidence and added to the cognitive dissonance experienced of feeling insecure whilst having to deliver the news of job losses with conviction. A line manager shared the following experience:

‘I was nervous of whether I am doing the right thing, whether I am saying the right thing’ (I-LM).

‘It feels that everyone is watching you and I question myself if I am doing the right thing’ (I-ER).

The feelings of doubt were also heighted as many of these procedures were new to many of the envoys, as a result of being inexperienced and unprepared for ‘dirty work’ tasks.

‘The tribunal has added real pressure. I did not know if what I did was right or wrong’ (I-LM).

From our study it was clear that redundancy envoys rarely shared their doubts with colleagues or managers and their experiences of being alone with their doubts was common amongst the interviewees.

Guilt

Guilt was the most widespread negative emotion experienced by redundancy envoys, arguably due to the conflicting role of being ‘builders’ of the organisation for most of their career and then switching to the role of a redundancy envoy and thus being perceived as ‘destroyers’ of the workforce.

‘You feel guilty, even if you are making the lowest performers redundant’ (I-OD).

Envoys appeared to feel personal responsibility for the need for redundancies and then felt guilty when they were implemented:

‘If I think I have not done enough to challenge the business on their rationale and the individual selection of a colleague, I feel like I have let that individual down’(I-ER).

‘The hardest thing for HR is to make people redundant when it is not a fault or mistake of the employee’ (I-HRD).

‘Of course, I had to stay professional in the meetings, but was going “bastards” under my breath’ (I-LM).

Feelings of guilt were not experienced to the same extent by HR professionals. Arguably this may be because they perceived decisions to implement redundancy programmes to be made by business directors, and so saw themselves more as a ‘vehicle’ to help the business achieve its operational aims. The role of implementing redundancies is traditionally a larger part of the role of HR professionals. From our interviews it was clear that many of the directors, managers and employee representatives had limited experience of the redundancy process. This is in contrast with HR professionals:

‘As an HR person you will get involved in restructures and you will do it a few times in your career, because that is your job’ (I-OD).

Manifestation of cognitive dissonance

The four second order themes identified clearly demonstrate examples of cognitive dissonance as experienced by the redundancy envoys. We found that cognitive dissonance led to redundancy envoys finding the experience of implementing redundancies emotionally taxing, which manifested itself physically. Our illustrative quotations in demonstrate how redundancy envoys experienced a negative impact on their sleep patterns due to the redundancies preying on their thought processes, driven by self-doubt, guilt and anxiety. To help overcome the sleep deficiency and negative emotional impact, redundancy envoys often relied on health interventions such as medication, therapy and psychological support. Some redundancy envoys required medical interventions for symptoms which they believed were from the long-term effects of experiencing cognitive dissonance and examples included a heart attack (OD) and onset of arthritis (LM). Redundancy envoys also experienced poorer physical health, which they believed to be as a result of the emotional burden, and in consequence did not engage in exercise and developed poor eating habits. These habits led to weight gain, increased smoking and alcohol intake, as demonstrated by our illustrative quotations in .

We did find, however, that some redundancy envoys were able to reduce their experience of cognitive dissonance by focusing on positive internal cognition. For example, some of the envoys in our study focused on the opportunities afforded to them from gaining experience of redundancy. Whilst closing a business where this HR Director made over 1000 employees redundant, including himself, he was approached to join a new firm through the outplacement support provider:

‘Carrying out the redundancies, lead me to become a partner in a new firm’ (I-HRD).

‘My assertiveness levels increased. I gained improved influencing and negotiation techniques and skills. My attention to detail increased significantly as decisions required were not only based on business knowledge but also employment law technicalities. It toughened me up’ (I-HR).

‘I enjoyed the challenge to resolve, influence and find appropriate solutions to the various challenges posed by the redundancy situation’ (I-OD).

Episodic nature of redundancies and the envoy as a ‘dirty worker’

From the perspective of the redundancy envoy our findings suggest that the infrequency of adopting the role of redundancy envoy compounded the cognitive dissonance experienced. Redundancy envoys perform the role of informing those at risk of redundancy and supporting the ensuing processes. Informing colleagues of the potential or actual cessation of their employment was not a task that the directors, managers or employee representatives in the case study carried out on a regular basis. For example, a Director of Quality and Business Excellence who had been in employment for over thirty-five years stated:

‘In terms of being involved with redundancies as a manager, this is actually my first time’ (I-OD).

‘I have been a manager for over 30 years yet I have never had to make someone redundant’ (I-OD).

From our interviews it would appear that some redundancy envoys were able to carry out the process by entering into a ‘faustian pact’ wherein their cognitive dissonance was due to trading personal values for the benefit of the greater good; in this case the financial sustainability of the organisation. This HR Business Partner referred to the implementation of redundancies with:

‘I was totally disengaged with the business vision, however I conducted the process professionally’ (I-HR).

‘If you are asking if I am happy, no I am not. I will do it, but I am not happy with it’ (DO-LM).

Table 3. ‘Dirty work’ tasks data structure.

‘I have now totally lost faith in my management to assist me if I have problems on site and I have genuine fears for the future and success of our department, and in turn my career.’

Low morale and motivation were key themes from the Mood Board suggesting that by implementing redundancies, redundancy envoys inflicted the consequences of ‘dirty work’ tasks on the employees:

‘The underlying feeling is that of almost being beyond the point of no return so it will be tough to keep people motivated.’ ‘I know the business has to save money, but what about saving the morale of your employees?’ ‘With the current redundancy process going on, the mood is not particularly great at present.’

‘the management team is not doing enough. I can’t see where the business is going and I have had enough… Customer complaints going through the roof.’ ‘No direction, no work, no future!’

Discussion

Reconceptualising the redundancy envoy as a quasi-dirty worker

Our findings illustrate the negative perception that employees can harbour towards redundancy envoys (see ), and the negative internal cognitions experienced by the envoys themselves (see ). The analysis of our empirical data supports the conceptualisation of redundancy envoys as conducting ‘dirty work’ tasks. Themes from our study stigmatise redundancy envoys as responsible for business failure, causing low morale, fostering feelings of insecurity and frustration with management. Furthermore, making people redundant is a conventional approach to dealing with ‘problem’ workers (Vickers & Parris, Citation2007). Those that conduct this type of ‘dirty work’, in this case redundancy envoys, are stigmatised in society and research has indicated that the experience of being stigmatised leads to low self-esteem and issues with identity (Baran et al., Citation2012; Dovidio et al., Citation2000; Kreiner et al., Citation2006) which is also identified by our findings.

Our findings demonstrate the stigmatisation of redundancy envoys as implementers of ‘dirty work’ tasks. The negative consequences are captured as stress and anxiety, empathy, doubt and insecurity, and guilt that can adversely impact performance, reduce job commitment and result in higher turnover (Gandolfi, Citation2008b; Ashforth & Kreiner, Citation1999). We also add to the labels used to describe redundancy envoys by including that of ‘smiling assassin’ as evidenced in our findings.

Building on redundancy envoys as conducting ‘dirty work’ tasks, we offer a further contribution by reconceptualising redundancy envoys as ‘quasi-dirty workers.’ We develop this reconceptualisation by drawing on our empirical data wherein the episodic nature of the redundancy process, coupled with the emotional stigma attached to conducting ‘dirty work’ tasks, seemed to heighten experiences of cognitive dissonance for many of the redundancy envoys in our study. Redundancy envoys seemed ill-prepared to carry out the role, with many stating that they had little, if any, experience. They may thus appear to be ‘dirty workers’ whilst implementing redundancies, although their exposure to ‘dirty work’ tasks are otherwise limited, hence ‘quasi’ akin to ‘partly’ or ‘almost’ ‘dirty work’ occupations.

The negative cognitive dissonance experienced, as highlighted in , aligns with the emotions experienced during emotive dissonance whereby redundancy envoys experience a clash between their inner feelings (identified as anxiety, stress, guilt and insecurity) and outer displays (appearing confident and smiling) (Hochschild, Citation1983). Tracy (Citation2005) argues that emotive dissonance research has overlooked social discourses; how work becomes and remains ‘dirty’. To this point, our findings build on this argument by demonstrating that the ‘dirty work’ tasks associated with the implementation of redundancies could occur sporadically and infrequently and can also be ‘lifted’ once the ‘dirty work’ tasks are complete. Our findings position redundancy envoys as experiencing emotional stigma, as this role requires them to be in close proximity to the negative emotions of the employee at risk who responds with the emotions of being upset or abusive in line with the work of Zhang et al. (Citation2021). Redundancy envoys thus ‘absorb’ the burden of the emotions from their redundancy victims. In a similar vein to McLoughlin’s (Citation2019) research on the ‘dirty work’ experienced in slaughterhouses, our findings demonstrate that the burden of the emotional stigma could lead to a negative impact on the wellbeing of the redundancy envoy. This is highlighted in where the manifestation of the negative impact is evident in disturbed sleep, medical interventions and the need for therapy to help redundancy envoys to cope. The data on employee perceptions captured in consolidates the interview data and validates how ‘dirty work’ tasks are stigmatised by the perceptions of the critical mass (Ashforth et al., Citation2007). These perceptions, coupled with the interview data, demonstrate how redundancy envoys engage in sense-making of their organisational experiences (Golden, Citation2009) with their own perceptions of conducting ‘dirty work’ tasks as validated by the workforce.

Cognitive dissonance experienced through the role of redundancy envoy

In drawing on , the second order concepts identified clearly indicate two opposite cognitions experienced by redundancy envoys; a positive cognition and a negative cognition. First, we notice an overwhelming negative internal cognition which is directly related to the unpleasantness of making an employee redundant. The symptoms experienced, as identified in , are in line with that of cognitive dissonance, whereby one is experiencing something that is uncomfortable and unpleasant (Festinger, Citation1957). We find the negative impact experienced by redundancy envoys to influence cognitive functioning and emotional distancing, which builds on research suggesting that employees tend to detach themselves emotionally from the organisation (Gervais, Citation2014). Our findings show that emotional distancing occurs as a result of the contradictions in the basic outlook of redundancy envoys (Kets De Vries & Balazs, Citation1997), which is to build and grow organisations rather than to reduce the scale.

The second cognition we identified is evidence of positive internal cognition. There is very limited research examining positive indicators for redundancy envoys and this is an area where our findings bring a fresh and very exciting new perspective on these positive impacts, such as promotions, career development and personal growth. Our findings support the limited body of work that has identified optimism when tough decisions were made (Noer, Citation1993) and demonstrate positive recognition for HR (Sahdev et al., Citation1999). When cognitive dissonance is experienced, an individual often copes with the internal conflict by modifying a cognition (Sronce & McKinley, Citation2006). In applying this to redundancy envoys, identifying a positive aspect in the implementation of redundancies, such as ‘personal development’, allows for a perceptual modification of the negative emotional experience, which leads to a reduction in the cognitive dissonance experienced. We therefore offer an extension to cognitive dissonance theory by demonstrating how individuals can formulate an attitudinal change by addressing the disconnect between cognition and behaviour by providing new evidence to suggest that the positive impact experienced by redundancy envoys results in a lesser experience of cognitive dissonance.

Conclusions

Practical and theoretical implications

The findings from this study offer extensions to the theories of ‘dirty work’ and cognitive dissonance. Our evidence positions the role of redundancy envoys as ‘quasi-dirty workers’, which highlights the importance of strategic HR interventions to support redundancy envoys in reducing the cognitive dissonance experienced whilst conducting ‘dirty work’ tasks. The significance of our findings is that redundancy envoys, contrary to most ‘dirty work’ occupations, only experience an element of ‘dirty work’ tasks on rare and infrequent occasions, such as during the implementation of redundancies. Due to their lack of preparedness for the ‘quasi-dirty worker’ role, and the shock of changing roles from ‘builder to destroyer’, the cognitive dissonance experienced is noteworthy. Further, we present new evidence to demonstrate how cognitive dissonance can be reduced for redundancy envoys by introducing a second, positive cognition to offset the overwhelming negative cognition redundancy envoys experience. The negative impact further extends to employee consultative representatives which experience the same negative psychological and physiological implications as managers and HR professionals during the process of redundancies.

The significance of this research guides us to focus on the importance of strategic HR interventions to provide sufficient support and training to redundancy envoys to help mitigate the negative emotions experienced due to being stigmatised whilst undertaking ‘dirty worker’ tasks, and to reduce the negative cognition. Practical HR interventions, such as providing support to prepare redundancy envoys for the potentially conflicting roles (Baruch & Hind, Citation1999; Petzer, Citation2020), could help reduce the negative cognition experienced by making sense of what is happening on a regular basis.

A further contribution is how our study suggests that in recognising and understanding the experiences of redundancy envoys at a deeper level, redundancies can be implemented responsibly and with compassion (Jacobs, Citation2020; Petzer, Citation2020). This builds on the work of Armgarth (Citation2009) that posits how HR interventions, such as a focus on wellbeing and preparing envoys for effective coping (Meichenbaum, Citation1985) as well as being ready to respond to unpredictable outcomes (Sweeny et al., Citation2006), can alleviate the negative implications for all impacted groups thus increasing likelihood of realising organisational benefits. Our research also supports Cascio’s (Citation2002) notion that HR interventions during redundancy implementation will boost the morale and confidence of the workforce during the aftermath and rebuilding stages. These interventions can thus be incorporated into practical guidance on the implementation of redundancies that is available through sources such as ACAS (Citation2021), CIPD (Citation2021) and XpertHR (Citation2021).

We recognise that a limitation to this study is that we were unable to assess the extent to which the positive impact negates the negative consequences experienced. Nevertheless, our findings offer important insights from the often-overlooked role of redundancy envoy. Collected over a five-year period, this rich qualitative study provides an important foundation for further work in this important area. We suggest that opportunities for future studies could include gaining a more detailed understanding of the causes of stress and exploring successful coping strategies for redundancy envoys, which could lead to the mitigation of the negative impact experienced. Gaining a better understanding of these aspects will help guide HR practitioners to implement the strategic interventions necessary to support redundancy envoys by reducing negative cognition. Our study suggests that supporting redundancy envoys is crucial to ensuring that they are effective in their substantive role of securing the future sustainability of the organisation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Åberg, C., & Torchia, M. (2020). Do boards of directors foster strategic change? A dynamic managerial capabilities perspective. Journal of Management and Governance, 24(3), 655–684. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-019-09462-4

- ACAS. (2021). ACAS redundancy. Retrieved from https://www.acas.org.uk/redundancy

- Agarwal, R., & Helfat, C. E. (2009). Strategic renewal of organizations. Organization Science, 20(2), 281–293. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1090.0423

- Allen, T. D., Freeman, D. M., Russel, J. E., Reizenstein, R. C., & Rentz, J. O. (2001). Survivor reactions to organizational downsizing: Does time ease the pain? Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 74(2), 145–164. Vol https://doi.org/10.1348/096317901167299

- Aronson, E. (1969). The theory of cognitive dissonance: A current perspective. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 4, pp. 1–34). Academic Press.

- Armgarth, E., 2009. 7.7 Human Resources Management protocol on restructuring. 6. Empirical background information: National data on restructuring and related effects on health.

- Ashforth, B. E., & Kreiner, G. E. (1999). “How can you do it?”: Dirty work and the challenge of constructing a positive identity. Academy of Management Review, 24, 413–434.

- Ashforth, B. E., Kreiner, G. E., Clark, M. A., & Fugate, M. (2007). Normalizing dirty work: Managerial tactics for countering occupational taint. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 149–174. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.24162092

- Ashforth, B. E., & Kreiner, G. E. (2014). Contextualizing dirty work: The neglected role of cultural, historical, and demographic context. Journal of Management & Organization , 20(4), 423–440. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2014.38

- Ashman, I. (2012a). Downsizing envoys: A public/private sector comparison (Acas Research Paper 11/12). Retrieved April 18, 2020, from http://www.acas.org.uk/media/pdf/7/1/Downsizing-envoys-a-public-private-sector-comparison-accessible-version.pdf.

- Ashman, I. (2012b). A new role emerges in downsizing: Special envoys. People Management, August, pp, 32–35.

- Ashman, I. (2015). The face-to-face delivery of downsizing decisions in UK public sector organizations: The envoy role. Public Management Review, 17(1), 108–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2013.785583

- Ashman, I. (2016). Downsizing: Managing redundancy and restructuring. In R. Saundry, P. Latreille, I. Ashman (Eds.), Reframing resolution (pp.149-147). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Augier, M., & Teece, D. J. (2008). Strategy as evolution with design: The foundations of dynamic capabilities and the role of managers in the economic system. Organization Studies, 29(8–9), 1187–1208. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840608094776

- Baran, B. E., Rogelberg, S. G., Carello Lopina, E., Allen, J. A., Spitzmüller, C., & Bergman, M. (2012). Shouldering a silent burden: The toll of dirty tasks. Human Relations, 65(5), 597–626. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726712438063

- Baruch, Y., & Hind, P. (1999). Perpetual motion in organizations: Effective management and the impact of the new psychological contracts on “survivor syndrome”. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 8 (2), 295–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/135943299398375

- Berg, B. L. (2001). Qualitative research methods for the social scientists. Allyn and Bacon.

- Bergström, O., & Arman, R. (2017). Increasing commitment after downsizing: The role of involvement and voluntary redundancies. Journal of Change Management, 17(4), 297–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2016.1252784

- Bernard, H. R. (2002). Research methods in anthropology: Qualitative and quantitative approaches (3rd ed.). Alta Mira Press.

- Bolton, S. C. (2005). Women’s work, dirty work: The gynaecology nurse as “other”. Gender, Work and Organization, 12(2), 169–186. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0432.2005.00268.x

- Bonner, A., & Tolhurst, G. (2002). Insider-outsider perspectives of participant observation. Nurse Researcher, 9 (4), 7–19. https://doi.org/10.7748/nr2002.07.9.4.7.c6194 PMID: 12149898.

- Boudreau, J. W., & P. M. Ramstad, (2007). Beyond HR: The New Science of Human Capital. Harvard Business School Press.

- Breen, L. J. (2007). The researcher ‘in the middle?: Negotiating the insider/outsider dichotomy. The Australian Community Psychologist, 19 (1), 163–174.

- Brockner, J. (1992). Managing the effects of layoffs on survivors. California Management Review, 34(2), 9–28. https://doi.org/10.2307/41166691

- Brockner, J. (1996). Understanding the interaction between procedural and distributive justice: The role of trust. In R. M. Kramer & T. R. Tyler (Eds.), Trust in organizations: Frontiers of theory and research (pp. 390–413). Sage Publications, Inc.

- Brockner, J., Heuer, L., Siegel, P.A., Wiesenfeld, B., Martin, C., Grover, S., Reed, T. and Bjorgvinsson, S., 1998. The moderating effect of self-esteem in reaction to voice: Converging evidence from five studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(2), 394.

- Burke, R. J. (2009). Downsizing and restructuring in organizations: Research findings and lessons learned–introduction. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences / Revue Canadienne Des Sciences de L’Administration, 15(4), 297–299. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1936-4490.1998.tb00171.x

- Cameron, K. (1994). Strategies for successful organizational downsizing. Human Resource Management, 33(2), 189–211. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.3930330204

- Cameron, K. S., Freeman, S. J., & Mishra, A. K. (1993). Organizational downsizing and redesign. In G. P. Huber and W. H. Glick (Eds.), Organizational change and redesign. Oxford University Press.

- Cameron, K. S., Kim, M. U., & Whetten, D. A. (1987). Organizational effects of decline and turbulence. Administrative Science Quarterly, 32(2), 222–240. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393127

- Campbell-Jamison, F., Worrall, L., & Cooper, C. (2001). Downsizing in Britain and its effects on survivors and their organizations. Anxiety, Stress and Coping, 14(1), 35–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615800108248347

- Cascio, W. F. (1993). Downsizing: What do we know? What have we learned? Academy of Management Perspectives, 7(1), 95–104. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.1993.9409142062

- Cascio, W. F. (2002). Strategies for responsible restructuring. Academy of Management Perspectives, 16(3), 80–91. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.2002.8540331

- Cascio, W. F. (2013). How does downsizing come about?. In C. L. Cooper, A. Pandey, and J. C. Quick (Eds.), Downsizing: Is less still more?. (pp.51 - 75) Cambridge University Press.

- CEB. (2014). Unlocking HR business partner performance in the new work environment (Report No. CLC8141714SYN).

- Cheng, P., & Hsu, P. (2012). Cognitive dissonance theory and the certification examination: The role of responsibility. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 40 (7), 1103–1111. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2012.40.7.1103

- CIPD. (2021). CIPD: Redundancy: An introduction. Retrieved from https://www.cipd.co.uk/knowledge/fundamentals/emp-law/redundancy/factsheet

- Clair, J. A., & Dufresne, R. L. (2004). Playing the grim reaper: How employees experience carrying out a downsizing. Human Relations, 57 (12), 1597–1625. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726704049991

- Coghlan, D. (2003). Practitioner research for organizational knowledge: Mechanistic- and organistic-oriented approaches to insider action research. Management Learning, 34(4), 451–463. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350507603039068

- Coghlan, D., Shani, A.B. and Roth, J., (2016). Institutionalizing insider action research initiatives in organizations: The role of learning mechanisms. Systemic Practice and Action Research, 29(2), 83-95.

- Cregan, C., Kulik, C. T., Johnston, S., & Bartram, T. (2021). The influence of calculative ("hard") and collaborative ("soft") HRM on the layoff-performance relationship in high performance workplaces. Human Resource Management Journal, 31(1), 202–225. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12291

- Devers, C. E., Dewett, T., Mishina, Y., & Belsito, C. A. (2009). A general theory of organizational stigma. Organization Science, 20(1), 154–171. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1080.0367

- Dewitt, R. L., Trevino, L. K., & Mollica, K. A. (2003). Stuck in the middle: A control- based model of managers’ reactions to subordinates’ layoffs. Journal of Managerial Issues, 15, 32–49.

- Dovidio, J. F., Major, B., & Crocker, J. (2000). Stigma: Introduction and overview. In T. F. Heatherton, R.E. Kleck, M. R. Hebl, & J. G. Hull (Eds.), The social psychology of stigma (pp. 1–28). Guilford.

- Downs, A. (1995). Corporate executions. Amacom.

- Edvardsson, R. I. (2008). HRM and knowledge management. Employee Relations: An International Journal, 30(5), 553–561.

- Etherington, K. (2004). Becoming a reflexive researcher: Using ourselves in research. Jessica Kingsley.

- Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Row, Peterson.

- Freeman, S. J. (1994). Organizational downsizing as convergence or reorientation: Implications for human resource management. Human Resource Management, 33(2), 213–238. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.3930330205

- Freeman, S. J., & Cameron, K. S. (1993). Organizational downsizing: A convergence and reorientation framework. Organization Science, 4(1), 10–29. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.4.1.10

- Frost, P. J. (2003). Toxic emotions at work: How compassionate managers handle pain and conflict. Harvard Business School Press.

- Gandolfi, F. (2006). Corporate downsizing demystified: A scholarly analysis of a business phenomenon. ICFAI University Press.

- Gandolfi, F. (2008a). Downsizing and the experience of executing downsizing. Journal of American Academy of Business, Cambridge, 13 (1), 294–302.

- Gandolfi, F. (2008b). Learning from the past - downsizing lessons for managers. Journal of Management Research, 8 (1), 3–17.

- Gandolfi, F. (2009). Executing downsizing: The experience of executioners. Contemporary Management Research, 5(2), 185–200. https://doi.org/10.7903/cmr.1197

- Gandolfi, F., & Hansson, M. (2011). Causes and consequences of downsizing: Towards an integrative framework. Journal of Management & Organization, 17(4), 498–521. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1833367200001413

- Gandolfi, F., & Hansson, M. (2015). A global perspective on the non-financial consequences of downsizing. Revista de Management Comparat International, 16(2), 185–204.

- Geimer, J. L., Zolner, M., & Allen, K. S. (2017). Beyond HR competencies: Removing organizational barriers to maximize the strategic effectiveness of HR professionals. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 10(1), 42–50. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2016.103

- Gervais, R. (2014). Measuring downsizing in organizations. Assessment and Development Matters, 6 (3), 2–5.

- Gioia, D. A., Corley, K. G., & Hamilton, A. L. (2013). Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia Methodology. Organizational Research Methods, 16(1), 15–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428112452151

- Gioia, D. A., Price, K., Hamilton, A. L., & Thomas, J. B. (2010). Forging an identity: An insider-outsider study of processes involved in the formation of organizational identity. Administrative Science Quarterly, 55(1), 1–46. https://doi.org/10.2189/asqu.2010.55.1.1

- Goethals, G. R., Cooper, J., & Naficy, A. (1979). Role of foreseen, foreseeable and unforeseeable behavioral consequences in the arousal of cognitive dissonance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37(7), 1179–1185. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.37.7.1179

- Golden, A. G. (2009). Employee families and organizations as mutually enacted environments: A sensemaking approach to work life interrelationships. Management Communication Quarterly, 22(3), 385–415. https://doi.org/10.1177/0893318908327160

- Greenglass, E. R., & Burke, R. J. (2001). Editorial introduction downsizing and restructuring: Implications for stress and anxiety. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 14(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615800108248345

- Harmon-Jones, E., & Harmon-Jones, C. (2008). Action-based model of dissonance: A review of behavioral, anterior cingulate, and prefrontal cortical mechanisms. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2(3), 1518–1538. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2008.00110.x

- Harter, J. K., Schmidt, F. L., & Hayes, T. L. (2002). Business-unit-level relationship between employee satisfaction, employee engagement, and business outcomes: A meta-analysis. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(2), 268–279. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0095893 https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.2.268

- Hartnell, C. A., Kinicki, A. J., Lambert, L. S., Fugate, M., & Doyle Corner, P. (2016). Do similarities or differences between CEO leadership and organizational culture have a more positive effect on firm performance? A test of competing predictions. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(6), 846–861. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000083

- Haynes, K. T., & Hillman, A. J. (2010). The effect of board capital and CEO power on strategic change. Strategic Management Journal, 31(11), 1145–1163. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.859

- Helms, W.S. and Patterson, K.D., 2014. Eliciting acceptance for “illicit” organizations: The positive implications of stigma for MMA organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 57(5), 1453-1484.

- Hochschild, A. R. (1983). The managed heart: Commercialization of human feelings. University of California Press.

- Holbeche, L. (2009). Aligning human resources and business strategy (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Hughes, E. C. (1962). Good people and dirty work. Social Problems, 10(1), 3–11. https://doi.org/10.2307/799402

- Jacobs, K. (2020). Skills HR will need in 2021: Restructuring your business with confidence. 11 December 2020, People Management. https://www.peoplemanagement.co.uk/long-reads/articles/skills-hr-need-2021-confident-restructuring-business

- Kets De Vries, M. F. R., & Balazs, K. (1997). The downside of downsizing. Human Relations, 50(1), 11–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872679705000102

- Kreiner, G. E., Ashforth, B. E., & Sluss, D. M. (2006). Identity dynamics in occupational dirty work: Integrating social identity and system justification perspectives. Organization Science, 17(5), 619–636. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1060.0208

- Lawler, E. E., III., & Boudreau, J. W. (2009). What makes HR a strategic partner? People and Strategy, (1), 14–22.

- Lemmergaard, J. (2009). From administrative expert to strategic partner. Employee Relations, 31(1/2), 182–197. https://doi.org/10.1108/01425450910925328

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage.

- Littler, C. R., & Innes, P. (2003). Downsizing and deknowledging the firm. Work, Employment and Society, 17(1), 73–100. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017003017001263

- Luan, C., Tien, C., & Chi, Y. (2013). Downsizing to the wrong size? A study of the impact of downsizing on firm performance during an economic downturn. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(7), 1519–1535. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2012.725073

- Maykut, P., & Morehouse, R. (1994). Beginning qualitative research: A philosophical and practical guide. Falmer Press.

- McLachlan, C. J., Greenwood, I., & MacKenzie, R. (2021). Victims, Survivors and the Emergence of ‘endurers’ as a Reflection of Shifting Goals in the Management of Redeployment. Human Resource Management Journal, 31(2), 438–453. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12314

- McLoughlin, E. (2019). Knowing cows: Transformative mobilizations of human and non-human bodies in an emotionography of the slaughterhouse. Gender, Work & Organization, 26(3), 322–342. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12247

- Meichenbaum, D. (1985). Stress inoculation training: A clinical guidebook. Pergamon Press.

- Nicholas, K., Sue, H., & John, P. (1998). Downsizing: Is it always lean and mean? Personnel Review, 27(4), 296–311.

- Noer, D. M. (1993). Healing the wounds. Jossey-Bass.

- Orlando, J. (1999). The fourth wave: The ethics of corporate downsizing. Business Ethics Quarterly, 9 (2), 295– 314. https://doi.org/10.2307/3857476

- Papalexandris, N. (1996). Downsizing and outplacement: The role of human resource management. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 7(3), 605–617. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585199600000146

- Parris, M. A., Vickers, M. (2010). “Look at Him…He’s Failing”: Male executives’ experiences of redundancy. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 22(4), 345–357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10672-010-9156-9

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Sage.

- Petzer, M. (2020). Don’t shoot the messenger: The enigmatic impact of conveying bad news during redundancy situations and how to limit the impact. Retrieved from https://www.cipd.co.uk/Images/psychological-impact-redundancies_tcm18-76926.pdf

- Petzer, M. (2020). Coronavirus and the workforce: How can we limit redundancies? CIPD LAB. Retrieved from https://www.cipd.co.uk/news-views/changing-work-views/future-work/thought-pieces/coronavirus-workforce-redundancies [accessed 23 February 2021]

- Pugh, J., Mitchell, M., & Brooks, F. (2000). Insider/outsider partnerships in an ethnographic study of shared governance. Nursing Standard (Royal College of Nursing (Great Britain): 1987), 14 (27), 43– 44. https://doi.org/10.7748/ns2000.03.14.27.43.c2798

- Quinlan, M., & Bohle, P. (2009). Overstretched and unreciprocated commitment: Reviewing research on the occupational health and safety effects of downsizing and job insecurity. International Journal of Health Services: Planning, Administration, Evaluation, 39(1), 1–44. https://doi.org/10.2190/HS.39.1.a

- Reed, L., & Proctor, S. (Eds) (1995). Practitioner research in health care. Chapman and Hall.

- Remenyi, D., Williams, B., Money, A., & Swartz, E. (1998). Doing research in business and management: An introduction to process and method. London.

- Rivera, K. D. (2015). Emotional taint: Making sense of emotional dirty work at the U.S. border patrol. Management Communication Quarterly, 29(2), 198–228. https://doi.org/10.1177/0893318914554090

- Rook, C., Hellwig, T., Florent-Treacy, E., & Kets de Vries, M. (2019). Workplace stress in senior executives: Coaching the “uncoachable”. International Coaching Psychology Review, 14(2), 7–24.

- Ryan, T. (1993). Insider ethnographies. Senior Nurse, 13 (6), 36– 39.

- Sahdev, K., Vinnicombe, S., & Tyson, S. (1999). Downsizing and the changing role of HR. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 10 (5), 906–923. https://doi.org/10.1080/095851999340224

- Schoenberg, R., Collier, N., & Bowman, C. (2013). Strategies for business turnaround and recovery: A review and synthesis. European Business Review, 25 (3), 243– 262. https://doi.org/10.1108/09555341311314799

- Simpson, R., Slutskaya, N., Lewis P., & Höpfl, H. (Eds.) (2012). Dirty work: Concepts and identities. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Simpson, R., Slutskaya, N., Lewis, P., & Höpfl, H. (2012). Introducing Dirty Work, Concepts and Identities. In R. Simpson, N. Slutskaya, P. Lewis, & H. Höpfl (Eds.), Dirty work. Identity studies in the social sciences. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Sronce, R., & McKinley, W. (2006). Perceptions of organizational downsizing. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 12(4), 89–108. https://doi.org/10.1177/107179190601200406

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (2nd ed.) Sage.

- Sweeny, K., Carroll, P. J., & Shepperd, J. A. (2006). Is optimism always best? Future outlooks and preparedness. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15(6), 302–306. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2006.00457.x

- Tal, K. (1996). Worlds of hurt: Reading the literatures of trauma (No. 95). Cambridge University Press.

- Teague, P., & Roche, W. K. (2014). Recessionary bundles: HR practices in the Irish Economic Crisis. Human Resource Management Journal, 24(2), 176–193. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12019

- Torres, O. (2011). The silent and shameful suffering of bosses: Layoffs in SME. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 13(2), 181–192. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJESB.2011.040759

- Tourish, D., Paulsen, N., Hobman, E., & Bordia, P. (2004). The downsides of downsizing: Communication processes and information needs in the aftermath of a workforce reduction strategy. Management Communication Quarterly, 17(4), 485–516. https://doi.org/10.1177/0893318903262241

- Tracy, S. J. (2005). Locking up emotion: Moving beyond dissonance for under- standing emotion labor discomfort. Communication Monographs, 72(3), 261–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637750500206474

- Trowler, P. R. (1998). Academics responding to change. New higher education frameworks and academic cultures. Open University.

- Van Dierendonck, D., & Jacobs, G. (2012). Survivors and victims, a meta-analytical review of fairness and organizational commitment after downsizing. British Journal of Management, 23(1), 96–110.

- Unluer, S. (2012). Being an insider researcher while conducting case study research. The Qualitative Report, 17(29), 1–14. Retrieved from https://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol17/iss29/2

- Vickers, M. H., & Parris, M. A. (2007). “Your Job No Longer Exists!”: From experiences of alienation to expectations of resilience—a phenomenological study. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 19(2), 113–125. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10672-007-9038-y

- Wan, C. S., & Chiou, W. B. (2010). Introducing attitude change toward online gaming amongst adolescent players based on dissonance theory: The role of threats and justification of effort. Computers & Education, 54(1), 162–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2009.07.016

- Waters, L. (2007). Experiential differences between voluntary and involuntary job redundancy on depression, job-search activity, affective employee outcomes and re-employment quality. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 80(2), 279–299. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317906X104004

- Wilkinson, A. (2005). Downsizing, rightsizing or dumbsizing? Quality, human resources and the management of sustainability. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 16(8–9), 1079–1088. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783360500163326

- Williams, S. M. (2004). Downsizing – intellectual capital performance anorexia or enhancement? The Learning Organization, 11 (4/5), 368–379.

- Wright, B., & Barling, J. (1998). The executioners’ song: Listening to downsizers reflect on their experiences. Revue Canadienne des. Sciences de L’Administration, 15, 339–355.

- XpertHR. (2021). XpertHR Redundancy. Retrieved from https://www.xperthr.co.uk/employment-law-manual/redundancy/20430/?keywords=redundancy&searchrank=1

- Yanchus, N. J., Brower, C. K., & Osatuke, K. (2020). The role of executives in driving engagement. Organization Development Journal, 38(3), 87–99.

- Zhang, R., Wang, M., Toubiana, M., Greenwood, R., & Greenwood, R. (2021). Stigma beyond levels: Advancing research on stigmatization. Academy of Management Annals, 15(1), 188–222. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2019.0031