Abstract

The point of departure for this paper is the observation that time is central to the study of careers, although research on time and careers is not easy to do and is expensive. The paper does not attempt to minimize these practical difficulties, but nevertheless suggests new ways forward for time-based careers research. First, we review the reasons for time playing such a central role in the study of careers. Next, we examine the approach scholars from other disciplines, ranging from philosophy to organization studies, have taken to the study of time, drawing out a number of anchor points that, we suggest, form the basis for a new research agenda for career studies. Finally, we develop idea for this agenda across three broad themes, to do with conceptual issues, methodological issues, and areas of study that could fruitfully be opened up.

Keywords:

Introduction

Time is and always has been central to the study of careers (Arthur et al., Citation1989, p. 8). However, if we examine the ways in which time has been implemented as a core construct in career research we see two broad forms. The first comprises three distinct approaches which have been well studied: the oldest research tradition of the three, namely stage models about the way that individuals develop over time (e.g. Erikson, Citation1963; Levinson, Citation1978); the way that individuals address time through time perspectives (e.g. Arnold & Clark, Citation2016); and the use of longitudinal research designs to examine the way that careers develop over time (e.g. De Vos et al., Citation2009). The second broad form of research on career and time consists of a number of approaches that examine distinctly different time-based constructs, for example timetables (e.g. Roth, Citation1963), time-bending (e.g. Dahm et al., Citation2019), time-lagged testing of employability (Lo Presti et al., Citation2020), time discounting (Xu & Yin, Citation2020), and the dynamics of career imagination (Cohen & Duberley, Citation2021). To be sure, there is no reason to assume that this list is complete, because as we shall see later in this paper time is an extraordinarily rich and complex construct that, in the scholarly literature generally, has yielded equally rich and different approaches to its study.

This is an impressive range of research. However, it tends to treat time as either a control variable or a dimension which, when added, provides a new framework for examining a familiar construct. This in no sense is meant to be a criticism of the work; as we shall expand on below, time-based research is extremely difficult to fund and carry out, and any work on it is clearly an advance. But there is a long-standing and rich literature on the nature of time, which makes it clear that time is more than just a variable or dimension. In this paper we turn to that literature to see if it points to ways of enriching the study of time and careers.

In a nutshell, time has, over the millennia, been a constant source of fascination and bewilderment to humanity. Fundamental questions about the nature of time and, for example, its irreversibility are still being vigorously debated (Carroll, Citation2016; Gold, Citation1962; Rovelli, Citation2018). Since the beginning of the present century the field of organization studies – arguably the intellectual home of career studies from which the latter draws deeply for theoretical and methodological insights – has become aware of, and has been working on, the need to bring time back in to its research. Examples include the influential special issue of the Academy of Management Review on time in organizational research (Goodman et al., Citation2001), a handbook edited by Roe et al. (Citation2009), a lively stream of research on the rich topic of the subjective nature of time in organizational research (Shipp & Jansen, Citation2021), and another on so-called temporal structures (Orlikowski & Yates, Citation2002). Our intention is by no means to suggest that time-related writing in the careers field is oblivious to these ideas. Rather, we think it might be helpful to examine them more explicitly to see what suggestions might emerge for further developing time-related careers research.

So the purpose of this paper is to return to the general scholarly literature on time to see how it might provide a clearer sense of direction for bringing time to the study of career. To do this, we seek answers to three questions: (1) how is time woven into current approaches in career studies? If time is central to the study of career, (2) what is it that we mean by time and how might answers to that question suggest new directions for the study of careers and time? More specifically, (3) has the field yet to fully exploit the wealth of insight about time from other disciplines?

We are fully aware that time-focused research is very difficult to do (Ancona, Goodman, et al., Citation2001; Shipp & Cole, Citation2015). There are three main obstacles. First, many different conceptualizations of time exist, requiring careful thought to select an appropriate framework. The second obstacle concerns the duration many time-focused studies can take. For example, establishing a three-cohort design that focuses on career aspirations of people entering the labor market and is able to differentiate between age, period, and cohort (APC) effects of commonalities and differences can easily take up to 30 years, which spans much of a typical academic career, let alone yielding results in time for contract and promotion reviews. Third, often these types of study are extremely costly. In order to follow the development of individuals over an extended period of time, the researcher needs to consider issues such as adequate channels to repeatedly address participants, data gathering instruments that are easy to use and ideally even motivating for participants but still allow adequate data collection, feedback mechanisms to keep participants engaged while not polluting the ongoing data collection, incentives and reminders for participants to stay in the panel, replacement strategies to counterbalance panel mortality, and data management that keeps track of data coming in at different points in time and potentially in different formats. Finding sources of funding that will support studies like this is extremely difficult.

Given the exigencies of academic careers, it is more than understandable to work with cross-sectional theoretical frameworks and to conclude papers with a call for longitudinal studies. Yet if time is, as is generally acknowledged, a central career construct, we need to find ways of overcoming these difficulties.

This paper cannot remove the obstacles raised by these exigencies, but it will show in more depth why it is helpful to put time more at center stage in career studies, what to focus on, and how this kind of research might be done. Our elaboration takes the form of a cross-disciplinary examination of the intellectual origins of thought on the nature of time and their implications for how time-based career research could be conducted. Its core contribution lies in providing a framework – a set of ‘anchor points’ – for deducing these implications.

We focus on career studies for greater clarity and precision of our diagnoses and arguments. However, much of what we outline in our section on time-sensitive career studies can be applied correspondingly to HRM research, too, and we will touch on this in our concluding remarks. The paper is organized as follows. First, we examine the paper’s key assertion, that time is a central feature of career studies, by briefly reviewing how the career construct is defined in the literature and locating time within a theoretical framework for career. Next, we examine the ways that time is treated in a number of other disciplines, looking for themes from which the careers field might learn, and identify seven ‘anchor points’ from these literatures. Finally, we take these anchor points to identify three broad thematic areas for more time-sensitive career studies, and offer suggestions for how they might be developed.

Time as a central feature of career studies

We list above many of the areas within the field of career studies in which time puts in an appearance. These are summarized and expanded on in .

Table 1. Approaches to studying careers and time.

Again, as we note above, the range of research referenced in covers an impressive breadth of topics, but tends to relegate the use of time to the role of a variable or dimension. Before turning to the time literature in our search for ways of enriching the construct of time in careers research, we return to basics and address the question: how are the concepts of career and time linked?

Implicitly or explicitly, comprehensive reviews of the field of career studies address time (e.g. Baruch & Sullivan, Citation2022; Gunz et al., Citation2020; Sullivan, Citation1999). Likewise, time is built into all widely-used definitions of career. For example (with emphases added):

the moving perspective in which the person sees his life as a whole (Hughes, Citation1958, p. 63)

a series of separate but related experiences and adventures through which a person passes during a lifetime (Van Maanen & Schein, Citation1977, p. 31)

the evolving sequence of a person’s work experiences over time (Arthur et al., Citation1989, p. 8)

the sequence of employment-related positions, roles, activities and experiences encountered by a person (Arnold, Citation1997)

the individually perceived sequence of attitudes and behaviors associated with work-related experiences and activities over the span of the person’s life (Hall, Citation2002, p. 12)

the pattern of work-related experiences that span the course of a person’s life (Greenhaus et al., Citation2010, p. 10)

the sequence of an individual’s different career experiences, reflected through a variety of patterns of continuity over time, crossing several social spaces, and characterized by individual agency, herewith providing meaning to the individual (De Vos & Van der Heijden, Citation2015, p. 7)

a pattern of a career actor’s positions and condition within a bounded social and geographic space over their life to date (Gunz & Mayrhofer, Citation2018, p. 70)

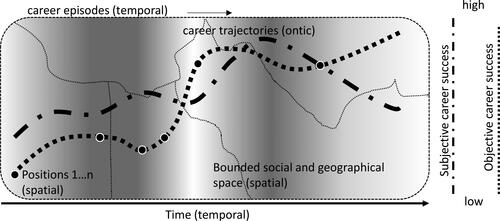

The pervasiveness of time can be seen as well in many other conceptualizations of career (Gunz & Mayrhofer, Citation2018, pp. 26–27). The obvious question that these definitions give rise to is: how does time relate to the construct of career? One potential approach to answering this question is to focus on the observation process that leads us to conclude that we are seeing something we call a career. In their Social Chronology Framework (SCF), Gunz and Mayrhofer (Citation2018) adopt the language of perspective to encompass the idea that the study of career involves the simultaneous application of three perspectives to do with being (ontic), space, and time. At any given point in time we can learn about a career actor’s condition – what we know about the actor, for example their age, income, occupation-specific knowledge, gender – and where they are located in social and geographic space, for instance their position as student in Argentina, COVID-19 patient in Denmark, worker in Indonesia, or as a contractor working with a variety of organizations in Zambia. We use the term ‘social space’ following Bourdieu (Citation1989) as ‘the set of all possible positions that are available for occupation at any given time or place’ (Hardy, Citation2014, p. 249), which provides a set of ‘social facts about the career actor [that] … define the actor’s location in relation to a social order and also to those Alters who might play a role in determining the future of their career’ (Gunz & Mayrhofer, Citation2018, p. 49). Both perspectives – ontic and spatial – tell us a lot about the career actor, but they provide no information about the actor’s career. That information only emerges when information about the actor’s career and position in social and geographic space is plotted on a notional three-dimensional diagram showing how condition and position change over time. shows this graphically; here, for simplicity, we focus on two aspects of the career actor’s condition that feature largely in the careers literature, namely their subjective and objective career success (Hughes, Citation1937).

Others have been here before, of course. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries physicists started exploring the implications of combining the three spatial (Euclidean) dimensions with the fourth dimension of time, yielding what is variously called space-time or Minkowski space (Naber, Citation2012). So space-time provides a canvas on which events in the universe can be drawn, and the idea has also been applied in organization studies (e.g. Boje et al., Citation2016; Calori, Citation2002; Carr & Hancock, Citation2006). The SCF points to an analogous space-time structure for career events, which we shall refer to here as career space-time. We can think of the SCF’s spatial dimensions (social and geographic) as the analogue of Euclidean space; time plays the same role that it does in space-time. Obviously the analogy is extremely partial given that we cannot define the dimensions of social and geographic space with the analytical precision of the three Euclidean dimensions. Our point is simply that career space-time provides a canvas on which career events and their ontic implications for career actors’ condition can be drawn. Other career scholars have noted, too, that both space (providing context for careers) and time are important dimensions of career (e.g. Yao et al., Citation2020)

We conclude this section with a brief note about our use of the term career actor, specifically that they can be collectivities as well as individuals (Coleman, Citation1974; Laumann & Marsden, Citation1979). The social and geographic space within which careers evolve is composed of career actors whose careers potentially coevolve with that of the focal career actor (Gunz & Mayrhofer, Citation2018, pp. 87–89). Collective actors, for example organizations for which the focal career actor provides contracting services, play a particularly significant coevolutionary role, a point to which we return in the final section of this paper.

Next, we turn to other disciplines to identify common themes in their treatment of time that might help us bring time back to center stage in career research.

What we can learn from other scholarship on time

Time is nature’s way to keep everything from happening all at once. (Wheeler, Citation1990, p. 10; ‘[d]iscovered among the graffiti in the men’s room of the Pecan Street Cafe, Austin, Texas’.)

Time has been and continues to be a source of fascination for writers from a great many major disciplines. In this section we select a few themes within each that are most helpful to our purpose of identifying how time might better be integrated into career scholarship. Two criteria guided our choices. First, we wanted to ensure that we linked our account of time to thinking about the fundamental nature of time to be found in the philosophical and physics literatures. Second, we drew on behavioral and social sciences to explore how research and writing on time in disciplines cognate to the study of careers, and the significance of this scholarship for the field in question may help thinking about time in the context of career. Obviously, our selections in both groups are, for reasons of space, very limited. In so doing we are of course neglecting many other disciplines grappling with time – for example anthropology (Gell, Citation1992; Munn, Citation1992), geography (Levine, Citation1997; Thrift, Citation2011), and theology (Swinton, Citation2016). The disciplines we focus on are philosophy, physics, sociology, psychology, and organization studies.

The philosophy of time

For people brought up in a modern educational system it seems odd to ask the question: what is time? We arrange to meet colleagues on Zoom at a particular time in the future, or book a flight home from a distant country (pandemics permitting) at a particular local time for that location. In either case we do so knowing about the precision of such an arrangement: the colleagues will log in to the meeting as anticipated, and we will find our flight on the departures board of the airport when we get to it.

But temporal ambiguities can intervene. A colleague may miss the beginning of the meeting because they forgot that the clocks had gone back an hour that morning, or we might discover at the airport that the flight already left because we forgot that the electronic calendar was set to our home and not the local time zone.

Ambiguities and arbitrary decisions like these pervade the way time is handled in human experience. Hall (Citation1983), arguing that time and culture are closely intertwined, differentiates between eight forms of time that he groups in the form of a mandala. Wax (Citation1959) differentiates between open and closed systems of time. Open systems view time as an open chronology, in the manner of the linear sense of history of the biblical Hebrews which, for them, implied a sense of progress leading to a final endpoint (the coming of the Messiah). Closed systems see life ‘as a series of repetitions or cycles—day and night, one season to another and return, misfortune and blessing, poverty and wealth’ (Roth, Citation1963, p. 96).

What some would call a ‘philosophy of time’ deals with very fundamental issues such as what time is, how it can be perceived, how human life is related to it, and whether time is real (Ryan, Citation2005). McTaggart (Citation1908) takes as his starting point that time is unreal, and proposes an influential duality of A- and B-series of time. The A-/B- distinction rests on what Frischhut (Citation2015) refers to as that between dynamic and static accounts of time. A-series or tensed theories are dynamic: we experience time as past, present, or future, with the future continuously becoming the present and the present the past. Tenseless B-series theories ‘reject the idea that time passes, no matter how passage is characterised’ (Frischhut, Citation2015, p. 144). Instead they view time as a sequence of events, in which Event X always comes before Event Y as in a chronology (Dainton, Citation2010).

One implication of viewing time from a tenseless perspective is that it appears to provide a foundation for inferring causality. Indeed it makes little sense to speak of Event Y, which comes later than Event X, as causing Event X. But the converse is not necessarily true. Jaques (Citation1982, p. 99) usefully distinguishes between two axes for organizing events. The axis of succession is a straightforward chronology, organizing events in a tenseless B-type order in which they happen. He invokes a separate axis, that of intention, to assign causality, or the lack of it, both prospectively and retrospectively to the events depicted in the access of succession.

We next look at the way in which time has been treated in the discipline of physics, treatments that call into question some of the basic assumptions of the philosophies that we have been examining here.

The physics of time

It is very tempting to become completely absorbed in the bizarre and counter-intuitive predictions that physics, initially through the contributions of special and general relativity, have made about time. How does one deal with the career consequences, for example, of a lengthy high-speed space voyage that results in the returning travelers finding that many more years have elapsed on Earth than have elapsed for them? Obviously, problems like this will not become an issue for careers scholars for quite some time even though they are now, for example, for the Global Positioning System (Ashby, Citation2003). That said, there are useful analogies that can be drawn for the careers field from physics. Notably, physicists see the world as a collection of events, not things: ‘even the things that are most ‘thinglike’ are nothing more than long events’ (Rovelli, Citation2018, p. 57), a theme that is echoed in treatments of time in organization studies, as we see below.

Depicting time as part of Minkowski space (Naber, Citation2012), or space-time, leaves a puzzle. None of the spatial dimensions, conventionally labelled the x, y, and z axes, imply any kind of directionality. Certainly for anyone on Earth, ‘up’ is different from ‘down’, but once in deep space the distinction disappears. Why is time, the fourth dimension of space-time, different? To use one of Carroll’s (Citation2016) examples, a video of someone emerging from a swimming pool, the surface of which suddenly changes from turbulent to smooth, then soaring up to a diving board and landing there on their feet obviously looks wrong. The one-way nature of time is referred to as the ‘arrow of time’, the idea that time is inherently directional; typically it is attributed to the second law of thermodynamics, which states that the entropy of an isolated system cannot decrease, it can only stay unchanged or increase.

A final observation about relativistic time which has relevance for careers concerns its approach to simultaneity. Once one moves beyond the proximities of an Earth-bound existence, the only way that Person A can know what Person B has just done is to wait for light from B to reach A, so that it is meaningless to talk about events happening across distances in which the lag is significant as happening ‘at the same time’. Furthermore, because the speed of light in a vacuum is invariant, the order in which an observer experiences a set of events can change depending on the observer’s location and velocity in relation to the events. Chronologies, therefore, are not absolute: although for the philosophy outlined above Event X always comes before Event Y, in physics this is not necessarily the case.

We conclude this section with a segue from the physics to the social science of time supplied by Einstein (Citation1954 [Orig. 1952]) in a discussion of the nature of space and time. He discusses ‘rendering objective the concept of time’ (ibid.) in terms of multiple observers of an event experiencing the same event (lightning): ‘In this way arises the interpretation that ‘it is lightning’, which originally entered into the consciousness as an “experience”, is now also interpreted as an (objective) “event”’.

The sociology of time

Sociological approaches to time shift the focus to making sense of how societies deal with time. The sociology of time is particularly interested in ‘exploring relationships between the concept of time and a number of contemporary sociological issues (e.g., leisure patterns, work scheduling, decision-making, organisational structures, economic)’ (Hassard, Citation2016, p. ix). An early definition of social time is that it ‘refers to the experience of inter-subjective time created through social interaction, both on the behavioural and symbolic plane’ (Nowotny, Citation1975, cited in Nowotny, Citation1992, p. 425). But, as Nowotny (Citation1992) points out, a fundamental theme in discussions of social time acknowledges that there is not one, but a great plurality of social times (Gurvitch, Citation1964).

Ryan (Citation2005) distinguishes between three treatments of time in social theory. The first (see also Bergmann, Citation1992) comprises explicit attempts to created a ‘sociology of time’ by making time the object of social theories (e.g. Durkheim, Citation1965; Gurvitch, Citation1964; Sorokin & Merton, Citation1937; Zerubavel, Citation1981). The second includes time explicitly in the examination of other social phenomena, in particular comprehensive analyses of society or parts of it. Examples include the Marxian analysis of capitalism with its stage-oriented concept of evolution towards the classless society (Marx, Citation1859); Weber’s core interest in historical developments and the specifics of modern capitalism and its iron cage of rationality (Weber, Citation2000 [Orig. 1904-05]); and Luhmann’s view of different forms of time (Eigenzeit) that social systems and their environment have (Luhmann, Citation1995). Ryan’s third category involves social theories in which time appears, if only implicitly, ‘as a taken-for-granted dimension along which a process plays out’ (Ryan, Citation2005, p. 840).

In order to specify the role that time plays in social groups, Sorokin and Merton (Citation1937) distinguish between what they call clock/astronomical and social times. The former is the familiar Newtonian idea of time as something independent of human activity, in this case measured by the orientation of the earth with respect to the sun and other astronomical objects. Definitions of standard times between regions derive from clock/astronomical time which first appeared with the use of mail coaches in late eighteen-century Britain, and was extended as a result of the spread of railways in nineteenth-century Britain and later the U.S. (Zerubavel, Citation1982a). Thus the actual implementation of clock/astronomical time in everyday life is socially defined, this being never more evident when jurisdictions switch to and from ‘daylight saving time’ rather than accommodating seasonal changes in the length of daylight by changing working hours (Sorokin & Merton, Citation1937).

Social time, by contrast, relates to specific social events and is essentially discontinuous, following cycles of varying durations. Gurvitch (Citation1964) describes how cultures not only have different social times, but also how these different social times conflict with each other and how various social groups within a society are in continuous competition over what constitute appropriate times. He differentiates between the micro-level of social groups and communities and their times and the times of macro-level of society and its institutions. Regarding the latter, he identifies various types of societies such as charismatic theocracies, e.g. Babylonia, ancient city states such as the Greek polis and the Latin civitas, and fascist societies, e.g. Argentina in the Peron era, and analyzes the respective social times. Indeed social times may be adopted specifically to develop a group’s distinctive identity, both by accentuating similitudes among members of the group and emphasizing differences from other groups, often those from which the group emerged (Zerubavel, Citation1982b). One example is the way that the early Christian church changed the date on which Easter is held to fall in order to sharpen the distinction between Church and Synagogue (ibid.; cf. Hughes, Citation1958 with respect to revolutionary movements).

Psychology of time

Time plays a key role in the psychological literature. Shipp and Cole (Citation2015) distinguish between how individuals use and manage time, and how they think about time. Developmental psychologists examine the developmental stages that individuals pass through over their life course (Sullivan & Crocitto, Citation2007), to which we devote more attention in the third section of this paper. Others look at learning processes; duration of emotional responses to internal and external events; self-concept in relation to position in the individual life cycle, time-orientation (past, present, future) and the influence of remembrance (past) and anticipation (future), and developmental stages of teams and related performance issues (McGrath, Citation1988; Roe, Citation2008); multi-tasking by doing more than one thing at a time (polychronicity; Bluedorn & Jaussi, Citation2007); variation in optimism with proximity in time (distal optimism vs. proximal pessimism; Sanna & Schwarz, Citation2004); and the change in the apparent passage of time as people age (Winkler et al., Citation2017).

Although researchers may use objective time as a metric in, for example, longitudinal studies, much time-related work in psychology focuses on the subjective view of time. Perhaps the most obvious concerns time perspective (TP; also time orientation, temporal focus, or time personality; Shipp & Cole, Citation2015), ‘the extent to which individuals characteristically direct their attention to the past, present, or future’ (Shipp & Cole, Citation2015, p. 244). Fundamentally, TP refers to individuals’ preferences for orientating their thinking towards past, present, and future. This orientation appears to be ‘situationally determined and … a relatively stable individual-differences process’ (Zimbardo & Boyd, Citation1999, p. 272) and is shaped by a number of factors, among them education, available role models, and childhood and adolescent socialization. It also has a variety of consequences for different aspects of behavior such as experience of environment and self as well as motivation (De Volder, Citation1979).

Future time perspective (FTP) is one important aspect of TP that links future goals and the present. Marko and Savickas (Citation1998) focus on an individual’s orientation to the future in relation to career planning, arguing ‘that a future orientation is a critical dimension in career development and that this time perspective can be learned through experience’ (108). FTP relates to a general consideration of and, correspondingly, concern for one’s future and has been conceptualized both as a malleable state and a trait. More recent views conceptualize it as neither state nor trait, but as a malleable cognitive structure. In their systematic review and meta-analysis, Kooij et al. (Citation2018) view FTP as a ‘malleable, cognitive-motivational construct that develops and changes as a function of experience over the life span’ (869). It affects areas such as individual decision making and well-being and is influenced by age (Laureiro-Martinez et al., Citation2017). Among others, having a more extended future time perspective ‘makes it possible to anticipate the more distant future; to dispose of longer time intervals in which one can situate motivational goals, plans, and projects; and to direct present actions toward goals in the more distant future’ (Simons et al., Citation2004, p. 123). As with TP generally, FTP is not a general disposition, but is related to different areas of behavior, e.g. personal development, family, occupation, politics, economics, and environment (Lamm et al., Citation1976) and assessment of time remaining, in life or in a particular role (Carstensen et al., Citation1999).

Organization studies on time

At the turn of the present century, Goodman et al. (Citation2001, p. 507) remarked that ‘[g]iven the different manifestations of time in organizational life, there is surprisingly little research on time in this setting’, and their call for more of this kind of scholarship has been echoed by a number of other writers (e.g. Kunisch et al., Citation2017; Navarro et al., Citation2015; Roe et al., Citation2009; Sonnentag, Citation2012). In a first step, we look at four approaches to the issue in organization studies.

A first group of contributions draws on basic works about time and emphasizes various conceptualizations of time. Typically, these contributions use the more generic literature on time as a springboard for taking a more in-depth look at some of these conceptualizations that are especially relevant in the context of organizations, groups, and individuals. George and Jones (Citation2000), for example, refer to widely used figures of frequency, rhythm, and cycle in the time literature to show their relevance for issues such as shift work, work assignments, and motivational states (see also McGrath & Rotchford, Citation1983; Mosakowski & Earley, Citation2000; Ofori-Dankwa & Julian, Citation2001). A second group focuses on the theoretical realm and looks for ways of emphasizing the temporal aspects in building theories about phenomena in the world of organizations. For example, Ancona, Goodman, et al. (Citation2001) develop a framework comprising conceptions of time, mapping activities to time, and actors relating to time and their relationships among each other to help understanding existing and shape future research (see also Ancona, Goodman, et al., Citation2001; Bluedorn & Denhardt, Citation1988; Bluedorn & Jaussi, Citation2007; Goodman et al., Citation2001; Orlikowski & Yates, Citation2002; Shipp & Fried, Citation2014a, Citation2014b; Sonnentag, Citation2012; Whipp et al., Citation2002). The third group takes a methods angle and discusses the implications that the temporal dimension has for the design of empirical studies and the formulation of hypotheses. Chan (Citation2014) addresses a number of methodological issues related to the design of empirical studies, operationalization and measurement, as well as data analyses (see also Mitchell & James, Citation2001). A final group picks up the problem of time in the world of work from an empirical point of view. For example, Jianhong and Nadkarni (Citation2017) analyze the link between two distinct temporal dispositions of CEOs, i.e. urgency and pacing, and corporate entrepreneurship as a key strategic behavior; Yakura (Citation2002) focuses on timelines (‘Gantt charts’) as visual artefacts that represent time and how they are used and integrated in organizational life.

Next, we briefly summarize three themes that emerge from this literature and that are important to the study of careers. Perhaps the most recurrent involves the objective/subjective distinction that pervades writing on time more generally (e.g. Ancona, Goodman, et al., Citation2001; Ancona, Okhuysen, et al., Citation2001; Granqvist & Gustafsson, Citation2016; Mosakowski & Earley, Citation2000; Orlikowski & Yates, Citation2002). Shipp and Jansen (Citation2021, p. 3) bring out the role of subjective time in what they call ‘time travel’, ‘as individuals (intrasubjectively) and collectives (intersubjectively) mentally travel through, perceive, and interpret time’ (ibid.: 8).

A second theme involves temporal structuring. This refers to the way that the everyday action of organizational actors produces and reproduces various temporal structures that mold the form and rhythm of their ongoing practices. These structures are identifiable patterns of events that serve to coordinate, orient, and guide activities, and provide structure and meaning to their actors. Examples include academic calendars, financial reporting periods, meeting schedules, and project deadlines. These temporal structures limit acceptable action and, at the same time, are influenced by the very action they are trying to inform. People use these temporal structures to shape their everyday work practices (Orlikowski & Yates, Citation2002, p. 685). Sources of these structures include entrainment, i.e. ‘the adjustment of the pace or cycle of one activity to match or synchronize with that of another’ (Ancona & Chong, Citation1996, p. 251), with the so-called ‘zeitgeber [sic], which is German for time giver’ (Granqvist & Gustafsson, Citation2016, p. 1011) or ‘external pacer’ (Geiger et al., Citation2021) – in the way, for example, that business activity cycles become tied to regulatory-imposed annual financial reporting cycles.

A third theme involves time scales and their effects on research. Zaheer et al. (Citation1999) direct our attention to the importance of specifying the respective time scale when doing organizational analyses, ‘the size of the temporal intervals, whether subjective or objective, used to build or test theory about a process, pattern, phenomenon, or event’ (ibid.: 725). The choice of the time scales heavily influences what one can observe and how researchers can relate to and understand the phenomenon at hand. Mitchell and James (Citation2001) point to the importance of knowing when the events being examined happened.

summarizes the major topics emerging from this brief review of time as seen from a number of other disciplines, the significance of the themes for the field of career studies, and how they connect with the anchor points that we discuss next.

Table 2. Themes from learning from other disciplines, connections with anchor points.

Anchor points when linking time scholarship to the study of careers

Next, we draw together seven themes concerning time that emerge from the disciplines examined in the previous section, themes that constitute anchor points for time-related research on careers. We introduce them by referring to an obvious over-arching fundamental theme that underpins this paper: Time matters to career studies and should be explicitly taken into account. When dealing with careers, time…

is uniquely and subjectively experienced for each individual and collective career actor. As special relativity makes clear, there is no such thing as simultaneity in the universe, merely approximations to it. Similarly, individual and collective actors live in their own presents, experiencing their own times which are linked to the times of other actors by a complex web of temporal structures (see anchor point #2). In order to understand career processes the observer needs to understand the subjective temporal frame that the actor inhabits. Imposing one from outside constitutes a form of evaluation, which may be needed for research purposes, e.g. deciding which of a sample of individuals is more successful because, in the observer’s terms, they have reached a particular goal sooner than the others, but which may not make any sense to the actor and might even obfuscate the research purpose, e.g. when looking at subjective timetables.

is experienced as a stream of events, typically comprising temporal structures, which may or may not be causally linked. Physicists view the universe as being comprised of events, not things; process theorists view organizations in the same way. Similarly, careers are built from a stream of events, some causally connected and others not. Patterns (temporal structures) can be seen in these streams of events that emerge from the social spaces within which careers are lived and that constrain and enable careers. The enactment of these patterns, in turn, changes the social structures that formed them.

relates individual and collective actors. Temporal structures (see anchor point #2) may be restricted to an individual actor or coordinate several actors. The more important the coordinating function, the more the temporal structure produces for the actors an externally-defined, objective view of time. If there is no implicit or explicit agreement between actors about how time works, it is very hard for them to work together.

is a means of mapping both the chronology of a career and the flow of events from a speculative future to a curated past. A central distinction about time that pervades its treatment in most, if not all, disciplines is that between tensed (A-series) and tenseless (B-series) time. Tenseless time provides a basic dimension for mapping events: when they begin and end. For it to do this it must be based on some form of objectification of time, which needs a consensus between actors and observers about how time is measured. But careers are experienced as a flow of events. At any given time the actor experiences the present while facing an unknowable future and remembering a past; in addition, the future is continually turning into the present, which in turn continually becomes the past.

plays a central role in assigning meaning to and making sense of careers. This happens in many ways. Actors curate their past as a narrative that helps them make sense of their career, building in new events as they flow from the present and reconstructing the narrative in the light of these new events. Identifying patterns – temporal structures – in the events being experienced in the actor’s present and anticipated in their future helps them make sense of what is happening to their career. For example, the actor might detect, or think they detect, a pattern in the kind of events they are being asked by their employing organization to take part in, which they interpret as a sign of career success (becoming included in important policy meetings) or failure (being cut out of such meetings).

directs attention to a process-oriented view and its dynamics. The dimension of time emphasizes ‘how and why things emerge, develop, grow, or terminate over time’ (Langley et al., Citation2013, p. 1), namely a process-based view of social reality, which Langley et al. contrast with ‘variance questions dealing with covariation among dependent and independent variables’ (ibid.). Such a view of careers underscores two aspects. First, it raises questions about why the patterns that can be seen in careers happen as they do: how events interact over time to cause these patterns. Second, recognizing that actors’ careers are lived within a social and geographic space, the view directs attention to the way that the various components of those spaces interact over time, that is, how the careers of each of the actors in the spaces affect the careers of the others.

is closely interlaced with space which, in turn, is crucial for navigating through geographic and social career space. Just as physical events can be located in space-time, career events can be located within an analogous career space-time in which ‘space’ is the social and geographic space through which actors move. An objective career, for example, can be defined by events happening at particular times, at a particular location in a social structure and geographic space, and these events require all of the spatial and temporal dimensions to define them properly. The history of events in the physical world (world line; Carroll, Citation2016) is constrained by the speed of light; similarly, career events are constrained by the speed with which information about these events travels between them.

We now turn to the consequences of these themes to career.

Time-sensitive career studies

Based on the sources of inspiration and the identified anchor points, six major areas for more time-sensitive career studies emerge. They relate to conceptual and methodological issues as well as to areas of study.

Conceptual issues

Temporal career theorizing

We suggest four major inroads for a better use of time in career theorizing: process orientation, modes of providing meaning, making use of a broader array of time concepts, and the dynamics of information flow.

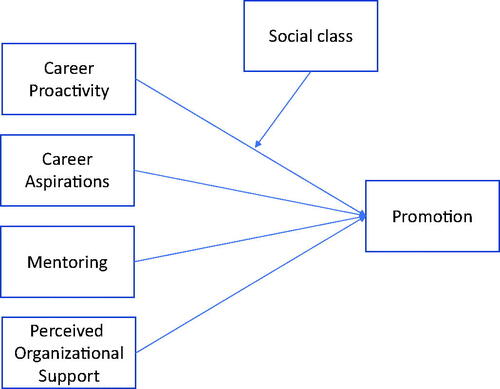

Process orientation. This reflects two substantially different approaches. The first, usually linked to the positivist paradigm and often called ‘variance orientation’ (e.g. Langley et al., Citation2013), analyzes the effects of a clearly defined set of (independent) variables on an outcome (dependent) variable. A schematic example with regard to objective career success might look like this ():

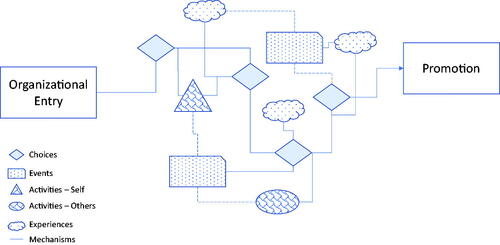

The second, more process-oriented, approach takes a different course. While outcome still plays a role, it focuses on the temporal unfolding of a process tied to events such as activities, choices, experiences; their sequence and multiple interlinkages; the identification of events and emerging phenomena, fluidity, and reversals. In all of this, time is essential, and new ways of depicting flows, relations, processes, paradoxes and tensions indicate a different view of the phenomena researched. gives a schematic example.

Such an approach does not require a specific epistemological and methodological stance. True, process-oriented research is skeptical about the mainstream positivist view and its underlying assumptions, e.g. in terms of the substance of objects. Rather, it often views reality not as a result of configurations of substantialized nature, but emerging from the interplay of partially recursive, interlocking processes and activities. In this sense, there ‘are’ no such ‘things’ as risky or safe careers, but they become more/less risky as a result of practices to which they are subjected. However, even within a positivist paradigm and quantitative analyses such as panel regression, longitudinal mixed models, and latent growth models, a process oriented view that accounts for time has its place. Recent examples include career studies that use path analyses (Yang & Chau, Citation2016), moderated mediation models (e.g. Blokker et al., Citation2019), and sequence analyses (Koch et al., Citation2017) for which time and temporal ordering are constituting characteristics.

Modes of providing meaning. Data that go beyond figures in rows and columns and point towards mutual causality, variations in development tempo and include ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ variants make it difficult to quickly generate meaning or multiple meanings. This requires a look beneath the surface to identify underlying contingent factors, generative mechanisms, and structures (Tsoukas, Citation1989).

Langley (Citation1999) points towards seven not mutually exclusive general strategies for sensemaking. Four of them seem of particular relevance for temporal career theorizing. Narrative emphasizes the need to integrate various bits and pieces of a rich data set into a comprehensive, detailed, and coherent story. Quantification denotes the way from rich, in-depth process data via coding incidents along strict characteristics to a quantitative time series suitable for statistical analyses. Visual mapping (like the example in ) enables the inclusion of very different elements and dimensions with causal, parallel, and recursive relationships as well as varying dynamics. Finally, temporal bracketing structures phenomena into meaningful episodes without implying a strict sequence. Note that in these strategies all three major ways of explanatory reasoning are compatible – deduction, induction, and abduction as the inference to the best explanation.

Variety of time concepts. Time in its objective sense as clock time dominates current research. Using a broader array of time concepts could further enrich our analyses. Two examples may suffice, based on views of time described above.

Wax’s (Citation1959) view of open vs. closed systems of time can be applied to theorizing about promotion systems in different organizations, leading to additional insight. For example, in Austria civil servants, by and large, get a pay raise after every two years of service independent of their performance (bi-annual leap), based on an open, clock-like system of time: the career is seen as a linear process leading to a distant end-point (retirement). Conversely, consultancies link performance ratings and organizational tenure (typically in the form ‘up or out’) to performance in a more closed system of time in which the focus of life is a series of projects, i.e. cycles of work each with its own beginning, middle, and end. Each project involves working in a different organizational setting and, probably, geographic location, and the life of the consultant is defined by where they are in their project, how well the project went, and which project, if any, comes next. Gurvitch’s (Citation1964) concept of plurality of social times draws attention to group-specific views on time and potential resulting conflicts, for example about appropriate next career steps between parents of young athletes and their coaches.

In each case – open vs. closed time, and plurality of times – the time concept adds value. It contextualizes the phenomenon by going beyond individual preferences to the underlying assumptions of social groups and organizations about the world based on jointly negotiated or unilaterally dictated views of time. Exploring and understanding the nature of these assumptions enriches understanding of the careers of the actors involved.

The dynamics of information flow in process models. A further area of process-oriented career research emerges from special relativity’s observation, referred to above, that simultaneity is not a meaningful concept in the universe generally, nor are chronologies absolute. By the same token, social structures build lags into the transmission of information, the result of social and geographical distances between actors. For example, asynchronous communication channels such as email or messaging apps may transmit messages within seconds or minutes, but may be received or read much later for all manner of reasons.

Lags of these kinds result in actors within the same social space having different understandings of their situation, sometimes with disastrous results (as depicted in the closing scenes of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, which result in the deaths of both leading characters). Space does not permit a more complete examination of the issue here; suffice it to say that a process view of careers must also consider the timing of information flows between actors, and this depends, among others, on understanding how the actors relate to each other across social and geographic space.

Contextualize time

Contextualizing time addresses the point that various levels of social complexity have their respective peculiarities when it comes to time. We will analytically differentiate between the individual, group, organizational, occupational, and societal level and use level-specific temporal structures by means of example to illustrate the respective idiosyncrasies and address some resulting research questions.

At the individual level, various events constitute personal temporal structures that order time spans such as day, week, month, and year and create orientation and meaning. Examples include scheduled daily activities such as meals, workouts, and prayers, as well as visits to friends and relatives, vacation periods, and travel over more extended time spans. Of course, what these temporal structures look like and what effects they have depends on a number of different factors such as personal dispositions, e.g. FTP, and contextual opportunities, e.g. climate, geography, legal regulations. Time-related aspects at the individual level lead to a number of interesting research avenues in career studies. Examples include various aspects of the mutual relationship between FTP and/or, more broadly, personal perspectives on time and views on career success, career timetables, adequacy and feasibility of career planning, and handling discrepancies between career aspirations and career achievements.

At the group level, temporal structures can appear in the form of stages that ascribe to groups steps in development (e.g. Tuckman, Citation1965) or phases that draw on ideas of punctuated equilibrium and see an alternation between periods of relative stasis and burst of activities with radical changes and leaps in progress (e.g. Gersick, Citation1989). Likewise, different lengths of time frame (long, short) that channel group processes towards cohesion and change, respectively (Quintane et al., Citation2013), team temporal diversity as the variations of team members’ time perspective, pacing style, and time urgency that affects team performance (Mohammed & Nadkarni, Citation2011), as well as temporal distance, i.e. work schedule difference within and across time zones, and its consequences for team performance (Espinosa et al., Citation2015) influence emerging group time structures such as meeting schedules, planning periods, and joint working hours. For career studies, promising research questions emerge. They include the influence of varying career aspirations on individuals’ willingness to accept, modify, or reject dominant temporal structures in work teams that affect individual and group performance, the effect of team members’ career stage indicating work experience and remaining opportunities on the emerging time frames in groups, and the consequences of a group’s temporal diversity and temporal distance for short- and long-term career goals.

At the organizational level, every organization implicitly or explicitly has views on time. Consequently, temporal structures abound, ranging from clearly visible strategic planning cycles and deadlines to more subtle rhythms of top leadership communications to employees about crucial events. With respect to exploring careers, one issue could be the relationship between organizational time perspectives and organizational career management, e.g. whether available career paths within organizations and the expected or required rate of promotions are linked to particular organizational views on time. In a similar vein, it would be interesting to explore whether individual career aspirations are affected by organizational views on time, e.g. through self-selection of new members with particular aspirations or through socialization effects once individuals have become members of the organization.

At the occupational level, temporal structures play a role, too. Examples include the taxi-driver market in Warsaw, Poland functioning as a linking ecology structured by state time, family time, and religious time (Serafin, Citation2019), and the time-related problems of pressure, speed-ups, and deadlines for knowledge workers (Väänänen et al., Citation2020). Likewise, occupations’ length of planning cycles and reaction time as well as the temporal rhythm of activities can vary greatly. Day traders, fire fighters, and restorers of applied arts and craft show great differences in their event time (Ancona, Okhuysen, et al., Citation2001) with traders on financial markets having to react often in minutes or seconds (Borsellino, Citation1999), fire fighters oscillating between life-and-death decisions in split-seconds and longer periods of relative tranquility (Geiger et al., Citation2021), and restorers working over extended periods of time to return a thing to its original appearance (Scott, Citation2017). Career issues that arise along such a line of thinking comprise, for example, the role of occupational temporal structures in career choice, career goals, career transitions, and subjective career success, the interplay of personality, construal of temporal structures in occupations and individual reactions to being passed over for a promotion, the co-variation of occupational timetables and extent of individual career inaction, and the relationship between occupation-specific time horizons for typical career moves and the degree, scope, and long-ranging of individual career planning.

At the societal level, temporal structures are clearly evident. State holidays, working hour laws, and rhythms of supreme courts being in session or not are just a few of the many examples in this area. Cultural and institutional factors do play a role in their formation and appearance. For career studies, comparative studies looking at the societal influence on and variations in temporality of careers constitute fascinating research avenues, for example by analyzing commonalities and differences between countries’ career development programs, perceptions of career interruptions, and the expected duration of otherwise similar issues such as entry into the labor market, parental leave, work careers, and retirement.

Convergence, stasis, divergence

Whether units of interest over time develop in a way that they converge, i.e. become more similar, diverge and become more different, or remain the same relative to each other (stasis) has been a long-standing issue in research and tackled from a number of disciplines. Its history can be traced back at least to Veblen’s argument about converging tendencies in imperial Germany and England related to the industrial revolution (Ward, Citation1971) or even further back ‘to the Scottish Enlightenment and the publication of an essay by David Hume in 1742 [and t]he ensuing ‘rich country-poor country’ debate between David Hume on the convergence side and Josiah Tucker on the nonconvergence side’ (Elmslie, Citation1995, p. 207). The debate, more recently about effects of industrialism, robotisation, and artificial intelligence, usually is heated and oscillates between bold forecasts of convergence and outright rejections such as ‘it just hasn’t happened, isn’t happening, and isn’t going to happen without serious changes in economic policies in developing countries’ (Pritchett, Citation1996, p. 43). Beyond being controversial, the convergence debate rages in a broad variety of disciplines such as political, sociological, psychological, demographic and management studies. Examples include convergence analyses of firm types (Whitley & Kristensen, Citation1996), state policies (Bennett, Citation1991), societies (Inkeles, Citation1998), and business systems (Crouch & Streeck, Citation1997).

Time plays an obvious role in convergence analyses and so do a number of the anchor points outlined in the previous section. When we look at careers from a process-oriented view and related dynamics and reflect on how they develop, grow, or terminate (Langley et al., Citation2013), questions of convergence, stasis or divergence become crucial, e.g.: Do accountants’ careers in different countries and cultures become more similar due to increasing importance of global standards? Likewise, growing or diminishing similarity, i.e., convergence or divergence, of career chronologies and the flow of career events are a crucial issue when, for example, comparing careers of men and women over time to analyze whether they become more similar or not. Temporal structures, important elements of the stream of events that relates individual and collective actors and for assigning meaning to and making sense of careers, can vary not only in different social and geographical spaces, but also over time. For example, a cross-national comparison of the development of temporal structures over time that govern politicians’ careers inevitably raises the issue of converging or diverging developments.

Against this background, career studies have to relate to four mutually connected issues when comparing developments over time: conceptualization of convergence, selection of units of analysis, choice of time span, and theoretical explanation of observed developments. We will deal with these issues in turn (for a more in-depth debate with a strong HRM-only focus see Mayrhofer et al., Citation2021).

Conceptualization of convergence. In career studies, this relates to four characteristics of the unit of analysis, e.g. when comparing careers of indigenous and migrant blue collar workers entering their new home country or minority women’s social capital in developed and emerging economies at labor market entry two decades ago and now. Direction points towards same or opposing development, for example social capital differences between the minority women in the two groups of countries remaining the same. Difference relates to the unit’s parameter differences becoming smaller, larger, or remain stable, e.g. the gap between financial career outcomes of indigenous and migrant blue collar workers widening over the last two decades. Level indicates the movement of a characteristics value, for example, the amount of minority women’s social capital growing in both groups of countries when comparing their entry situation in 2000, 2011, and 2022. Temporality, i.e. dynamic or static, simply indicates whether the analysis is covering a certain time-span or purely cross-sectional (‘snapshot’). These four characteristics distinctively describe the major forms of (non-)convergence. Extent points towards the magnitude of difference. It indicates the distance between (dis)similar states/developments (Farndale et al., Citation2017). Although not being a constitutive characteristic, it adds valuable information to all constructs. gives an overview.

Table 3. Forms of convergence (Source: Mayrhofer et al., Citation2021, p. 372).

(Dis)Similarity lacks the dynamic component and merely describes the state of two units at a certain point in time. Stasis reveals that differences remain stable, the units develop in the same direction and at the same level, e.g. income of various employee groups over time or the use of career planning in organizations in different countries. Directional convergence indicates same direction and stable difference, but a changing level, e.g. income differences between employee groups remain, but all of them get more money in absolute terms. Final convergence occurs when units of analysis irrespective of their initial starting point strive towards a common endpoint. Divergence, finally, exists when the difference increases over time, irrespective of the direction of the development and with changing levels.

Selection of units of analysis. The units chosen are the pivot of such analyses. In career studies, they can comprise any characteristic of individual and collective career actors and of the context that enwraps them. Examples include individual career aspirations in different countries, the use of mentoring in organizations, and legal regulations about parental leave.

Choice of time span. The chosen time bracket is absolutely crucial when analyzing convergence since this heavily influences the outcome. For example, when you have an underlying wavelike development over time that, on average, remains at the same level, but you only analyze the time span covering the leading side of a wave, you might mistakenly assume ‘increase’ as the dominant pattern.

Theoretical explanation of observed developments. Without a sound explanation of the findings and identifying underlying mechanisms, results of convergence analyses stay at the descriptive level and are, at best, interesting, but not revealing. To make sense of the respective findings requires the availability of strong theories that come, by and large, from three broad sources: cultural, institutional, and functional. Depending on the source and concrete framework chosen, respective mechanisms can help to explain the findings, for example socialization, mimicking/isomorphism, and cost efficiency.

Methodological issues: time-sensitive empirical research

Three building blocks in particular could strengthen time-sensitive empirical research. First, we suggest making greater use of longitudinal research designs. This is a familiar call and we have nothing add to previous voices that point into a similar direction (e.g. Khapova & Arthur, Citation2011). Note, however, that a simple two-points-in-time study does not constitute, at least strictly speaking, a longitudinal study as they do not account for developmental patterns of change (for a more detailed discussion on two waves measurement see Ployhart & MacKenzie Jr., Citation2015)

Second, we call for the use of different types of longitudinal data. Large-scale longitudinal data sets, often funded on a (supra-)national basis, exist that within certain limits are open to all researchers. Prominent examples include the Swiss Household Panel (SHP; Tillmann et al., Citation2020), the National Longitudinal Surveys (NLS; https://www.bls.gov/nls/) in the USA, the United Kingdom Household Longitudinal Study (UKHLS; Economic and Social Research Council (Great Britain) et al.,), 2011), the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey (https://melbourneinstitute.unimelb.edu.au/hilda), the World Value Survey (www.worldvaluessurvey.org), the European Working Condition Survey (EWCS; see https://eurofound.europa.eu/european-working-conditions-surveys-ewcs), and the German Socio-Economic Panel (GSOEP; Goebel et al., Citation2019). All contain career-relevant data covering issues such as personality, jobs and job changes, industry characteristics of the jobs held, etc.

Retrospective questionnaires and interviews allow an in-depth reconstruction of long sequences of career transitions. Despite some inevitable limits due to retrospective bias and oblivion, core elements of one’s career such as major jobs, crucial career transitions, kinds of employers etc. are often easily and accurately retrieved from the respondent’s memory. In addition, specific data collection techniques such as life grid interviews or the event calendar method support adequate reconstruction (Dlouhy et al., Citation2020, p. 243).

Archival data (for using archival data in micro-organizational research see Barnes et al., Citation2018) provide access to career relevant analyses even if the data originally were not collected for such analyses. Examples include the archives of professional associations or public institutions providing the basis for analyzing career outcomes of chief federal prosecutors (Boylan, Citation2005), publicly available information on the Web about careers of typically prominent individuals such as CEOs (Bonet et al., Citation2020; Koch et al., Citation2017), and, in a similar manner, information on professional network sites such as LinkedIn.

Real-time data allows the collection of career relevant information over a defined period of time. This includes diaries in their traditional handwritten form as well as technology-enabled app versions that trigger reactions according to a pre-set or random pattern. Likewise, embodied computing that relies on tangible technologies tied to the body (‘on, in, around’) opens up new ways. Examples range from facial recognition surveillance systems and smart cities to wearables, e.g. intelligent wristbands or watches, and epidermal electronics fixed to the skin and measuring electric activity by body parts such as skeletal muscles, brain, and heart to implantables and ingestibles. These data potentially are of interest for career researchers and participants. For example, they can offer new insight into emotional and stress-related reactions as well as micro- and macro-movement patterns during specific career transitions such as exit talks, promotion procedures etc. To be sure, a number of substantial legal and ethical issues arise when using such data sources (Pedersen & Iliadis, Citation2020).

Third, the variety of collected data makes a huge difference. Mixed methods studies that combine observations leading to extensive field notes, interviews, analyses of documents, and archival data over an extended period of time allow the researchers to gain an in-depth view of the field. Through intensive immersion in the field, it supports both an emotional and a cognitive sense of what happened within the covered time span and provides rich material for temporal bracketing and graphical display of sequences and trajectories during the interplay of stability and change. In addition, it helps to better make sense of what has happened and develop theory (Langley et al., Citation2013).

Areas of study

Rejuvenated career stage models

Career stage models (for an overview and their development over time see Sullivan & Crocitto, Citation2007) were an established part of career studies until the early 1980s. They deal with complex phenomena such as the whole life course (e.g. Erikson, Citation1963; Levinson, Citation1978), work-related life-span (e.g., Super, Citation1980) and crossing external and internal organizational boundaries including organizational socialization processes as ‘small-scale’ career stage models (e.g. Hall, Citation1987; van Maanen, Citation1977; Van Maanen & Schein, Citation1979). Their basic reasoning is sound: They assume that discernable, sequentially ordered stages exist that actors go through; that each stage has typical characteristics in terms of their onset, what has to be dealt with and achieved when going through it and what it takes to enter into the next stage; and that these stages are not purely idiosyncratic, but have some regularities and serve as lifespan temporal structures. Overall, they provide orientation in dealing with career as a complex, time-sensitive phenomenon. At the same time, such models have been criticized for, in particular, truncating the richness of the underlying phenomenon, artificial bracketing into stages, turning a blind eye to substantial overlap and deviations in sequence, being too static, and at least implicitly assuming a unidirectional development instead of allowing for movements in multiple directions (for critique about stage models in other areas see, e.g., Dall’Alba & Sandberg, Citation2006)

To contemporary career studies, career stage models have lost nearly all their appeal. Beyond the long-standing critiques outlined above, the final blows to popularity came from the seemingly fundamentally different new careers and the highly individualized work and life concepts emerging over the past three decades that seem to lie outside the reach of career stage models. Contrary to such an account, we call for reassigning career stage models a prominent place in career studies again. Beyond recalling that models per definitionem are an abstraction from reality and that proponents of major career stage models would argue that the stages were never meant to be seen as ‘iron cages’ to be passed through consecutively in a linear way, we see three major reasons supporting such a call. First, even if one accepts (which we do not) that career stage models cannot capture so-called new careers and underlying developments, the traditional career is far from being dead. Traditional lines of work still exist in great numbers as careers in retail, craft such as plumber, masonry, bricklayer, academia, (large parts of) management, civil service, firefighters, physiotherapy and many others attest. Likewise, characteristics of the new careers such as boundarylessness and more frequent job changes at best only partially hold up to theoretical and empirical scrutiny (see, for instance, the analyses in Inkson et al., Citation2012; Kattenbach et al., Citation2014; Rodrigues et al., Citation2016).

Second, career stage models have unchanged value when applied to boundary crossing into and within organizations. Working for medium and large sized organizations where, for example, formal boundaries play a particular role still constitute a substantial proportion of the workforce. For example, in the US, nearly two thirds of those employed work in organizations with more than 100 people with over half being part of what the U.S. Census Bureau defines as large organizations (more than 500 employees; Caruso, Citation2015).

Third, a number of issues emerged during the past four decades that wait to be incorporated in career stages models since they hardly feature in existing career stage models. These issues implicitly or explicitly have temporal aspects.

Organizational phenomena. A number of new realities exist within organizations such as fewer well-defined jobs and job titles, more fluid and project-related bundles of activities, strong virtual and remote elements in cooperation relationships such as virtual teams, new ideas of organizing, e.g., agility, and the emergence of culturally mixed work groups in many sectors and segments beyond internationally operating organizations. Time plays an obvious role here since many of these phenomena change the organizational rhythm of work, affect how individuals experience time in, e.g., deadlines, and encounter culturally preformatted views on time. Furthermore these phenomena have changed over time (the point behind the ‘new careers’ referred to above) and, given their sensitivity to, for example, macroeconomic contextual factors there is no reason to suppose that they will not continue to change. Consequently, career stages are affected, too.

Global contextual realities. These have consequences for careers in general and for career stage models in particular. Take Ageing and Gender Equality as two examples included in the UN and WEF global agenda, respectively, that have an obvious reference to time: Does the increased life span between formal retirement and death and being able to make a visible contribution to the common good in this period require additional stages after leaving the work force and are these temporal stages gendered?

Emphasis on nonlinearity. Some voices argue that paradoxical and dialectic relationships are at the heart of social relationships (Langley et al., Citation2013). Building paradox, contradictions, tensions, dialectics etc. into career stage models as a central underlying theme then becomes crucial. Underlying this is at least one clear temporal aspect: how individuals experience future time plays an important role in such nonlinear processes.

Fundamental career changes. These always have been part of the career picture as the time-limited careers of soldiers, top athletes, or ballet dancers with its need to change careers at a relatively early age testify to. Such changes now seem to be more prominent. Rejuvenated career stage models have to include them not only as the exception to the norm, but as one of the regular options, including less extensive time spans than one’s whole working life.

Shorter career episodes. A switch between two or more occupations, shorter membership cycles in organizations, long-standing freelancing or gig-work and the simultaneous membership in two or more organizations call for a more fine-grained temporal approach leading to, for example, micro-stage or parallel models.

Greater variety of stakeholders. Arguably, the past decade has seen a rise in the number and kind of stakeholders that have to be taken into account when developing career stage models. Examples include partners working full-time, patchwork configurations of partners, parents, and siblings, and a digital eco-system with the related public that globally and in real-time can affect careers. Synchronizing or at least being aware of different time structures of these stakeholders is crucial in order to understand and navigate various career stages.

Importance of coevolution. The case of dual-career couples or the importance of the reputation of the organization, e.g. in consulting or academia, for future individual career steps are just two examples to illustrate this issue. As this is not only important for career stage models, but a crucial element of a stronger integration of time into career studies, we turn to this in the next section.

Multi-actor coevolution

As noted above, careers do not unfold in isolation, but are embedded in a social and geographic space that is populated by other actors, both individual and collective, all of whom develop over time. Thus, the focal actor’s career is related to the careers of other actors such as supervisors, colleagues, mentors, the organizations they are working in or for (Gunz & Mayrhofer, Citation2018), and other institutions with which they interact, for example their professional bodies. Take an HRM director of an important national subsidiary of a multinational corporation whose national CEO is promoted to become CEO at the headquarters and is on the lookout to fill the position of global head of HRM; a second-level financial officer in a financial institution learning in their morning paper that the financial service provider they are working for is deeply entangled in massive financial fraud; and the case of the national infrastructure severely damaged by natural disasters such as earthquakes or man-made events such as large explosions or wars. In all of these cases, events that affect (the careers of) actors in the social and geographical space of the focal career actor have massive effects on the careers of the latter.

Conceptually, this points towards the way that various actors’ careers at different levels coevolve (our account here draws on that of Gunz & Mayrhofer, Citation2018, pp. 173–180). Coevolution happens when ‘[t]he environment [of an evolving entity] changes in part because it also often consists of evolving systems that try to optimize their fitness. This interdependency, where the change in fitness of one system changes the fitness function for another system, and vice-versa, is called co-evolution’. (Heylighen & Campbell, Citation1995, p. 184) In the context of careers, ‘fitness’ can be interpreted in terms of career success, without necessarily being specific about what we mean by success. When we say that careers coevolve, we mean that, because a focal career actor is embedded in a social and geographic space, their career success affects the success of others in their social space, and the success of these others in turn affects the focal actor’s success. Suppose that a career actor has a number of mentors who coach their protégé about who needs to be impressed when putting forward ideas within their organization. As the protégé’s hit rate increases in terms of successful proposals, the mentors’ careers are likely to benefit from being associated with this success. But, additionally, if the organization benefits from these successful proposals then everyone – protégé, mentors – benefit from this corporate success, too.

The example we have just provided is one of coevolution as a virtuous cycle: success breeding success. But coevolution can produce deleterious effects on coevolving groups of actors as, for example, synergies degrade to destructive competition (Heylighen & Campbell, Citation1995). Mentorship relationships, typically held up in the literature as something that everyone benefits from, can deteriorate and become mutually destructive or lead to the development of self-serving cliques (Gunz & Mayrhofer, Citation2018, p. 177, Citation2020). Coevolution theory suggests approaches that can be taken to modify the extent to which these negative outcomes take place (Baum, Citation1999), but the basic point remains: viewing career actors and others in their social space as coevolving systems provides an alternative, dynamic (i.e. time-based) perspective that can lead to counterintuitive predictions that, in turn, suggest novel research questions.

This suggests an approach to the study of careers that examines the coevolution of a set of careers – individual or collective – over time, potentially providing a rich set of new ideas to work with. To take the example of mentorship: time by itself has been at the core of mentorship research for decades. Kram’s (Citation1985) seminal work on the mentorship relation studied it as a multistage process, and much work on mentorship has implied a time base when outcomes of different mentoring relationships and processes are studied (Chandler et al., Citation2011). Nor is the idea of a set of mentorship relationships comprising a social network new (e.g. Higgins & Kram, Citation2001). A coevolutionary perspective on the relationship, however, opens up exciting new territory as the dynamics of complex social groupings are explored over time

Examples of time-sensitive studies

The issues in the previous section outline the lay of the land of time sensitive career studies. This section comprises three examples that roughly outline desirable, yet feasible studies that illustrate potential ways forward, even in the light of the substantial obstacles of doing time-sensitive research to which we allude above.

Process orientation