Abstract

The antecedents and outcomes of teacher burnout have received increasing research attention in China over the last three decades, as burnout becomes a serious issue for a large workgroup of 1.6 million teachers in Chinese education system. However, there has been no comprehensive review to synthesize the literature in this area, limiting our understanding on how burnout is experienced in this specific culture context. In this paper, using job demands-resources (JD-R) model as a theoretical framework, we conduct an integrative literature review on teacher burnout in China, which includes 67 studies published from 1995 to the present. We review on the job demands, job resources, personal resources as the antecedents of burnout, and also on the outcomes of burnout. Our review indicates that teachers in China experience unique job demands because of specific cultural context. Moreover, we summarize how proactive and avoidant coping contribute differently to the mechanism of burnout development among Chinese teachers. Third, drawing from the recent extension of the JD-R model, we build a conceptualized framework to suggest future avenues for teacher burnout research in China, including examining job demands, job resources, and personal resources under specific cultural context, further investigating the role of coping strategies in the JD-R model, and conducting more research on intervention.

1. Introduction

The burnout experience of teachers has received international research attention because teaching is among those professionals with the highest level of job stress and burnout (Farber, Citation1991; Hakanen et al., Citation2006; Stoeber and Rennert, Citation2008; Skaalvik and Skaalvik, Citation2017). Teacher burnout has serious consequences for the teachers’ occupational health and for the quality of education. Research in different countries indicates that burnout can impair teachers’ physical and mental health, reduce their job performance, and ultimately lead them to quit the profession (Maslach and Leiter, Citation1999; Tang et al., Citation2001; Boreen et al., Citation2003; Hong, Citation2012).

Given its close link to employee wellbeing and job performance, burnout becomes a critical concern for researchers and practitioners in human resource management (HRM). Research has been conducted to find out the role of various HR practices in reducing burnout (Castanheira and Chambel, Citation2010; Stankevičiūtė and Savanevičienė, Citation2019), while managers have been informed about the importance of promoting employee wellbeing through minimising burnout (Lee and Akhtar, Citation2007; Holland et al., Citation2013). Burnout has been recognized as a hazardous occupational health issue over the past few decades (Maslach and Leiter, Citation2016). It is generally conceptualized as a three-dimensional construct: emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (DP) or cynicism (C), and reduce personal accomplishment (PA) (Maslach et al., Citation2001). Due to its devastating consequences, researchers have shown interest in investigating the mechanism of burnout development. According to the job demands and resources (JD-R) model (Demerouti et al., Citation2001; Bakker and Demerouti, Citation2017), burnout is the result of high job demands and low job and/or personal resources. In the educational setting, a number of studies across different cultures show that teacher burnout is found to be positively related to job demands, including heavy workloads, difficult students, role conflict and ambiguity (Pithers and Soden, Citation1998; Kyriacou, Citation2001). On the other hand, teacher burnout is negatively related to job resources and personal resources, such as social support (Halbesleben, Citation2006), performance feedback (Alarcon, Citation2011), emotional intelligence (Mérida-López and Extremera, Citation2017), and personality traits (Kim et al., Citation2019). Notably, apart from demands and resources, recent literature explores the role of coping as a cognitive and behavioural strategy in burnout process, and attempts to integrate it into the JD-R model to increase its predictive power (Bakker and de Vries, Citation2021). However, findings are inconclusive regarding the function and type of coping strategies in the JD-R model, and a review in teaching profession can generate insights on this topic.

Though literature have shown that teachers across the globe share some common factors in their burnout development, recent research argues that different educational and cultural conditions cultivate distinct work and personal characteristics and contribute to varied burnout experiences. In a meta-analysis of teacher burnout from 156 studies across 36 countries, García-Arroyo et al. (Citation2019) reported that differences between countries explain a significant percentage of burnout variability (20.1% for EE, 6.4% for C, and 14.8% for PA). In a similar meta-analysis of 30 studies from different countries, Zheng and Guo (Citation2017) reported that the negative relationship between emotional intelligence and burnout is significantly higher for teachers in China (r=-.38) than for teachers in other countries (r=-.21). However, research is limited on how the antecedents and outcomes relate to teacher burnout in a specific cultural context, and how those factors contribute to the mechanism of burnout development in that context.

Teachers in China is one of the largest teacher group in the world, with a teaching workforce of approximately 1.6 million (Ministry of Education of People’s Republic of China, Citation2017), and this group is facing extremely high level of burnout. In China, teachers reported the second highest scores on emotional exhaustion compared with their peers in 35 other countries (mean = 54.75 compared with average means = 38.29) (García-Arroyo et al., Citation2019). Moreover, a national survey identified that nearly 30% of Chinese teachers experienced serious burnout (SINA, Citation2005), which is 10% higher than that of teachers in U.S. (Farber, Citation1991). China’s cultural context, social and educational conditions add specific demands to this group and contribute to shape a unique burnout profile of Chinese teachers. For example, Confucian beliefs, the traditional Chinese education philosophy, expects teachers to be not only knowledge providers, but also role models, authority figures, or even parents to the students (Cortazzi and Jin, Citation1997; Lau et al., Citation2005; Zhang and Zhu, Citation2008). Such a high and sometimes unrealistic expectation makes teachers vulnerable to burnout (Luk et al., Citation2010). Also, in Chinese education system, the emphasis of students’ academic performance and fierce examination competition generates another major stressor for Chinese teachers (Xu, 200; Zhang and Zhu, Citation2007).

Given the significant consequences of teacher burnout and the unique burnout profile of Chinese teachers, it is urgent to undertake an integrative review to conceptualize a comprehensive mechanism around teacher burnout in China, and bring valuable insights into international teacher burnout research, especially for countries with similar educational environment. With this paper, we aim to make the following contributions. First, we provide a comprehensive understanding of antecedences and outcomes of burnout in the Chinese teacher group through the lens of the job demands and resources (JD-R) model (Demerouti et al., Citation2001). Specifically, we focus on teachers’ job demands, job resources, personal resources, and outcomes of burnout under the Chinese context, and then consider these in relation to three-dimensional construct of burnout. Second, we review on the role of coping strategies, one of the individual cognitive and behavioral strategies, in explaining the burnout process among Chinese teachers. We summarize how proactive and avoidant coping contribute differently to the mechanism of burnout development. Third, drawing from the recent extension of the JD-R model, we build a conceptualized framework to suggest future avenues for teacher burnout research in China.

2. Theoretical backgrounds

2.1. Burnout

Burnout has been defined as a three-dimensional construct in the predominant research literature. Initially, it is characterized as a syndrome of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment among workers working in the human service and interreacting extensively with people (teachers, nurses, etc.) (Maslach and Jackson, Citation1986). Later, burnout was expanded beyond the human service professions, with its three dimensions relabelled in broader terms: exhaustion, cynicism, and reduced professional efficacy (Maslach et al., Citation2001). Exhaustion refers to feelings of being over extended and depleted of one’s emotional and physical resources. The cynicism (or depersonalization) has been described as a detached response to one’s work and a cynical attitude toward other people at work. Finally, reduced professional efficacy refers to a decline in one’s feelings of competence and effectiveness in work (Maslach & Leiter, Citation2008). This definition has been widely accepted in the burnout literature, and is commonly cited in recent research works (Demerouti, Citation2015; Maslach, Citation2017; Bianchi et al., Citation2019).

Burnout is a prolonged response to chronic job stressors, and the development of burnout is an ongoing process. The research on burnout generally supports a sequential link from exhaustion to cynicism. When one faces excess demands, exhaustion occurs first as one’s emotional and physical resources are depleted, which prompts actions to detach from various aspects of work to cope with work overload. Therefore, cynicism is an immediate reaction to exhaustion. However, reduced professional efficacy has a more complex relationship to the other two dimensions of burnout, sometimes being directly related to them and sometimes being more independent (Demerouti et al., Citation2001; Maslach and Leiter, Citation2008).

2.2. The JD-R model

In this review, we synthesize our findings on teacher burnout in China according to the JD-R model. As one of the leading job stress models, the JD-R model was initially proposed about two decades ago to explain the development of burnout (Demerouti et al., Citation2001). Since then, it gradually becomes popular among researchers and inspires increasing numbers of empirical studies (Bakker et al., Citation2014). The reason for its popularity is that the model has the potential to include all job demands and job resources into a comprehensive framework to explain stress and burnout, and that it can be adapted in a variety kind of occupations (Schaufeli and Taris, Citation2014; Bakker and Demerouti, Citation2017). Because of the broad scope and flexibility of JD-R model, we find it an effective framework to organize the antecedents and outcomes of burnout among Chinese teachers, which covers a wide range of work characteristics from different levels. We believe it can offer insightful explanation on how those factors contribute to the development of burnout.

The JD-R model considers burnout to be a symptom that arises when individuals experience high job demands and have inadequate job resources available to them to cope with and effectively manage/decrease those demands (Bakker and Demerouti, Citation2017; Bakker and de Vries, Citation2021). Job demands refers to physical, social or organizational aspects of work that require physical or mental efforts and are therefore associated with psychological costs (Demerouti et al., Citation2001). For example, workload, role ambiguity, role conflict, role stress, stressful events, and work pressure are found to be particularly important demands (Lee and Ashforth, Citation1996). Job resources are defined as job characteristics that help to achieve work goals, reduce job demands and the associated psychological costs, or lead to personal growth (Demerouti et al., Citation2001). Examples of job resource are autonomy, skill variety, performance feedback, etc. (Alarcon, Citation2011). According to the JD-R model, job demands are found to have a strong positive relationship with exhaustion, while job resources show a consistent negative relationship with cynicism (termed as disengagement) (Bakker et al., Citation2004). When employees are exposed to chronic high job demands, they will gradually become emotionally and physically exhausted. If they do not have enough job resources to deal with those demands, they tend to disengage in their work and develop cynical attitudes.

Later refinement of the model proposes that job resources can buffer the impact of job demands on burnout. For example, Bakker et al. (Citation2005) found that several job resources (autonomy, performance feedback, social support, and quality of relationship with the supervisor) could buffer the relationship between job demands (work overload, emotional demands, physical demands, and work–home interference) and burnout among employees in higher professional education in Netherland. More evidence was found in a study among employees from home care organizations (Xanthopoulou et al., Citation2007b). This study showed that employees cope better with job demands (emotional demands/patient harassment) when they have adequate job resources (autonomy, social support, performance feedback, and opportunities for professional development) available.

More recent literature adds personal resources in the JD-R model, arguing it can also be used to deal with job demands (Bakker and Demerouti, Citation2017). Personal resources are defined as aspects of self that are generally related to resiliency, which can be used by individuals to take control of their (work) environment (Hobfoll et al., Citation2003). In a survey study among 714 Dutch employees, Xanthopoulou et al. (Citation2007a) showed that personal resources (optimism, self-efficacy, and self-esteem) have a mediating effect between job resource and exhaustion. Similarly, in a longitudinal study of employees in Netherlands, Xanthopoulou et al. (Citation2009) found that personal resources (optimism, self-efficacy, and self-esteem) have predictive validity for job resources, and work engagement. Thus, individuals with more personal resources are likely to get more job resources, cope better with demands, and are less likely to experience burnout.

3. Review method

Four databases, specifically Google Scholar, EBSCO, ERIC and CNKI (China Academic Journals) were searched for research articles using the following key words: teacher, education, (professional) burnout, job stress, occupational stress, Chinese teacher, China. To be eligible for inclusion the article had to meet the following criteria. First, it needed to be published in a peer-reviewed journal between 1995-2020 and discuss empirical research on the correlates of Chinese teacher burnout. Second, the research subjects were full-time teachers in primary, secondary school, and/or college/university settings. Third, the studies were reported in English or Chinese language. Following these criteria, studies on teacher burnout in non-teaching staff such as principles, and in early education or special education, were removed. We identified 67 empirical articles (see details in ), with 46 samples on primary and/or secondary level teacher burnout, 15 on college and university level teacher burnout, and 6 pieces on teacher burnout in an unspecified level.

Table 1. A review of teacher burnout research in China from 1995 onward (Empirical research N = 67).

Table 1. (continued)

Table 1. (continued)

Generally, the reviewed empirical studies used cross-sectional designs and self-report questionnaires. It is notable that except for one longitudinal study, the other 66 articles applied one-shot designs, which did not allow inference of a causal relationship. Sample sizes varied across the 67 studies from N = 86 to N = 1,831. With five exceptions of large sample size (N > 1,000) (Lau et al., Citation2005; Pan et al., Citation2010; Zhang et al., Citation2014; Zhong and Ling, Citation2014), all studies employed small and/or convenient samples.

4. Measures of burnout

In the burnout literature, the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) is a clear leader in measuring burnout, which assesses all three dimensions of burnout (Maslach and Jackson, Citation1986). In line with an early focus on employees doing ‘people work’, the MBI-Human Service Survey (MBI-HSS) was designed to assess burnout among workers in human service or health care profession. As burnout research expands, the inventory was revised to measure burnout in educational settings (the MBI-Educators Survey, or MBI-ES), and in non-human-service fields (the MBI-General survey, or MBI-GS) (Maslach et al., Citation1996).

In our review, the MBI and its variations are still the most common measurements of teacher burnout in China. Nearly half of the studies utilize directly translated version of MBI, with 18 studies using the MBI-ES and 12 studies using the MBI. Also, on the basis of the MBI, researchers in China attempt to localize burnout scales by making revisions on items, but they still follow the three-dimensional construct in the original measure (Li and Shi, Citation2003; Wang et al., Citation2003; Li and Wu, Citation2005). For example, Li and Wu (Citation2005) conducted interviews and open surveys among several occupation groups in China in order to make contextualized revision to the MBI. They developed the Chinese Maslach burnout inventory (CMBI) including 7 items on each of the three dimensions, with acceptable reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.815 for EE, 0.765 for DP, 0.672 for PA) and construct validity (significant correlation with thoretically related constructs such as well-being and self-esteem). Similarly, Wang et al. (Citation2003) revised MBI-ES based on literature of burnout measurements and interviews of 42 Chinese secondary school teachers. The modified version (MBI-ES-21) contained 7 items on each dimension, with satisfactory reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.86 for EE, 0.84 for DP, 0.80 for PA) and construct validity (significant correlation with thoretically related constructs such as depression and self-efficacy). In the reviewed papers, the most commonly utilized measures that tailored according to Chinese context were those of Li and Shi (Citation2003; k = 8); Wang et al. (Citation2003; k = 5); Li and Wu (Citation2005; k = 7); Li and Wang (Citation2009; k = 4), while 5 other different measures were also used for burnout of teachers in China. In these studies, we found that results do not vary across different measures, one possible explanation is that most of the measures used (65/67) are MBI or revised versions of MBI, and that those studies all reported results on the three dimensions of burnout.

5. Antecedents of teacher burnout in China

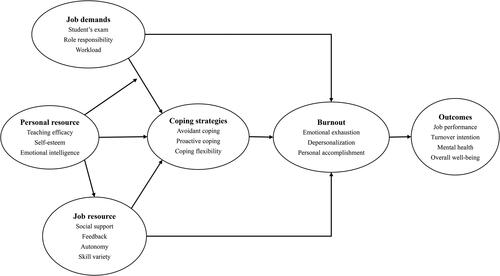

Building on the JD-R model, we organize the antecedents of teacher burnout in China into three main categories: job demands, job resources, and personal resources (). We discuss the varied predicting effects of those variables on the three dimensions of burnout.

Table 2. Antecedents of teacher burnout in China.

5.1. Job demands

Of the 67 articles reviewed, 11 studies have investigated the relationship of job demands and burnout, with more than 20 job demands being identified and examined (see a full list in ). Instead of discussing all the stressors that related to Chinese teacher burnout, we will focus on three demands (role responsibility, student’s exam performance, and workload) which should be understood within the Chinese context and constitute a unique burnout profile of Chinese teachers.

Table 3. Job stressors of teacher burnout in China.

Table 3. (continued)

Student’s exam performance is a particularly significant demand for teachers in China. Education is highly valued in Chinese society, and it is widely believed that excellent academic performance in exams is solid proof of a successful education. To achieve this goal, teachers are constantly under the expectation to help students get high scores, from primary school to high school, culminating with the increasingly competitive college entrance examination (Zhang and Zhu, Citation2007). Students’ exam results are used by schools as criteria to evaluate teachers’ job performance, and are considered by parents and students as a vital aspect of a teacher’s professional ability, making it a major stressor triggering burnout (Wang et al., Citation2015b). Using multiple regression analysis, Xu (Citation2003) found that pressure from student’s exam performance explained 12% of the variance of emotional exhaustion, while Jiao (Citation2009) reported that it explained 8% of that variance of depersonalization. Some other studies include student’s exam performance as a factor of a single latent variable, without reporting details of its specific predictive validity (Liu, Citation2004; Liu et al., Citation2008).

Role responsibility could be another major demand for Chinese teachers because of Confucian beliefs, the basis of traditional education philosophy in China. The role responsibility for Chinese teachers is different from that of western culture. Traditionally, the role of Chinese teacher is deeply influenced by Confucian beliefs, which holds the expectations that teachers are not only knowledge providers, but also role models, authority figures, or even parents to the students (Cortazzi and Jin, Citation1997; Lau et al., Citation2005; Zhang and Zhu, Citation2008). As a saying goes, ‘a teacher a day, a parent forever’ (yiri weishi, zhongsheng weifu), Chinese teachers are expected to take a parent role to some extent and care about students in every aspect of their life. Such a great responsibility and high moral standard may be too overwhelming for a teacher to meet, and thus causing extra stress (Luk et al., Citation2010). Meanwhile, teachers are expected to be strict to students and teach with severity. There is another famous saying from ‘The Three Character’, ‘To feed the body, not the mind – fathers, on you the blame! Instruction without severity, the idle teachers’ shame’ (Pang, Citation1999, p.20), which reflects this deep-rooted belief. Some researchers propose that this teaching philosophy will unconsciously distance Chinese teachers from their students in daily interactions, and possibly contribute to a relatively higher depersonalization level in burnout, compared with western teachers (Lau et al., Citation2005; Luk et al., Citation2010). In a survey study among 511 teachers from primary and secondary school, Liu et al. (Citation2008) showed that teacher’s role responsibility has a significant positive relation with burnout (β=.28), while Xu (Citation2003) reported a positive relation between role responsibility and emotional exhaustion (r=.15). Liu (Citation2004) included role responsibility as a factor in the measurement of job demands but did not analyse it as an individual variable.

In addition, work overload is recognized as a serious stressor among Chinese teachers. Primary and secondary teachers in China often experience overwhelming workload, because schools and parents expect teachers to help students with fierce competition at this stage of education. As result, teachers often have to work for extra hours to meet the demanding condition (Liu et al., Citation2008; Jia and Lin, Citation2013). In a survey study among 367 primary and secondary school teachers, workload ranked number two in six major demands that teachers faced, and is found to have a significant positive relation with emotional exhaustion (r=.17) (Xu, Citation2003). In a similar study among 133 English teachers from secondary school, Zhang and Zhu (Citation2007) added that workload explained 15% of the variance in emotional exhaustion and 4% of the variance in depersonalization. In a SEM analysis, Cai and Zhu (Citation2013) reported that workload is a significant predicator of burnout (β=.37) among 200 secondary school teachers.

5.2. Job resources

It is striking that job resource examined in teacher burnout research in China is mostly limited to the social support that teachers can get, while other important resources (e.g. performance feedback, autonomy, and skill variety) have largely been ignored. Social support refers to the assistance provided by one’s social network (Taylor et al., Citation2004). In the reviewed studies, 15 of them have examined the relationship of social support and burnout among different teacher groups in China. Previous research has shown that social support associated with the emotional exhaustion dimension, while inconclusive results are found for the relationships with the other two dimensions (Xu et al., Citation2005b; Lin et al., Citation2009; Li, Citation2012). Using multiple regression analysis, Xu et al. (Citation2005b) found a significant but weak association between social support and emotional exhaustion among 766 primary and secondary school teachers (β= −.11), and Li (Citation2012) reported similar results between the two constructs among a small sample of 157 teachers from university (β=-.16). Xu et al. (Citation2005b) also found a significant but weak association between social support and depersonalization (β=-.17), while Li (Citation2012) failed to find a significant association between the two constructs. Also, in a SEM analysis of 482 secondary school teachers, Lin et al. (Citation2009) found that social support was significantly related to all three dimensions of burnout (β=-.30, −.23, and .20 for emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment, respectively).

Sources of social support are significant in the prediction of burnout, with supervisor support, co-worker support being the most commonly studied sources (see ). It is noticeable that supervisor support affects all three dimensions of burnout more strongly than co-worker support (Wang and Xu, Citation2004; Leung and Lee, Citation2006; Song, Citation2008). Using SEM analysis in a study among 379 teachers, Leung and Lee (Citation2006) found stronger association between supervisor support and emotional exhaustion (β=-.32) than that between co-worker support and the same dimension (β=-.18). Using multiple regression analysis, Wang and Xu (Citation2004), in a survey study among 679 primary and secondary teachers, found weak to moderate associations between supervisor support and burnout (β=-.27, −.33, for emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, respectively), while co-worker support corelates with these constructs weaker (β=-.15, −.23, for emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, respectively). In a similar study of 400 teachers from secondary school, Song (Citation2008) found stronger association between supervisor support and burnout (β=-.27, −.26 for emotional exhaustion and reduced personal accomplishment, respectively) than between co-worker support and burnout (β=.18, −.24 for emotional exhaustion and reduced personal accomplishment, respectively). Support from families and friends, as well as support from students, are less studied in burnout research. However, a few studies do find them useful in alleviating burnout (Wang and Xu, Citation2004; Zhang and Zhu, Citation2007).

Table 4. Sources of social support and teacher burnout.

5.3. Personal resources

A variety of personal resources have been explored in Chinese teacher group. Besides self-efficacy (teaching efficacy) and self-esteem which have been considered crucial to individuals’ work wellbeing (Xanthopoulou et al., Citation2009), other constructs related to one’s resiliency have also been investigated, such as emotional intelligence.

Some studies report that self-efficacy, a person’s belief in his or her ability to perform certain tasks, is negatively related to teacher burnout, and most significantly with the dimension of reduced personal accomplishment (Tang et al., Citation2001; Chan, Citation2007; Yu et al., Citation2015). In a similar vein, teaching efficacy (Cherniss, Citation1993), which refers to teachers’ professional efficacy, is also negatively associated with teacher burnout. Specifically, teaching efficacy is further defined as personal teaching efficacy and general teaching efficacy with the two having different effects on the three dimensions of burnout (Li et al., Citation2007b; Li et al., Citation2008; Meng, Citation2008; Guo, Citation2017). For example, among primary and secondary teacher groups, Li et al. (Citation2007b), Li et al. (Citation2008) and Meng (Citation2008) found that personal teaching efficacy could predict depersonalization and reduced personal accomplishment, while general teaching efficacy would explain emotional exhaustion. However, in a university teacher sample, Guo (Citation2017) reported that personal teaching efficacy explained the variance of all three dimensions, whereas general teaching efficacy showed no significant effect.

Furthermore, teachers with higher self-esteem experience lower burnout level. Findings from two studies shows that self-esteem could negatively explain all three dimensions of burnout (Xu et al., Citation2005a; Ho, Citation2016). For example, in a sample of 766 primary and secondary teacher, Xu et al. (Citation2005a) reported that self-esteem negatively predicts emotional exhaustion (1% explained variance), depersonalization (6% explained variance) and reduced personal accomplishment (10% explained variance). Ho (Citation2016) confirms the result in a similar teacher sample. Also, these findings are consistent with other studies using similar measures of self-esteem, such as self-concept (Hao, Citation2008; Liu et al., Citation2008) and self-evaluation (Sun et al., Citation2011).

Recent research begins to examine the effect of emotional intelligence (i.e. emotional appraisal, positive regulation, empathic sensitivity, positive utilization) on burnout (Chan, Citation2006; Yao and Guan, Citation2013; Ju et al., Citation2015). Findings from those studies generally shows that four aspects of emotional intelligence interact differently with three dimensions of burnout. Specifically, positive regulation of emotion is found to reduce emotional exhaustion, while positive utilization of emotion could generate teacher’s personal accomplishment.

We have seen that cultural and educational settings in China bring unique job demands (student’s exam performance, role responsibility, workload) that lead to teacher burnout. Meanwhile, research examined how job resource (social support) and personal resources (self-efficacy, self-esteem, and emotional intelligence) corelate with teacher burnout in China. Moreover, coping strategies, one of the individual cognitive and behavioural strategies, also associate with teacher burnout and play a role in burnout development among Chinese teachers.

6. Coping strategies

Coping refers to ‘constantly changing cognitive and behavioural efforts to manage specific external and/or internal demands that are appraised as taxing or exceeding the resources of the person’ (Lazarus and Folkman, Citation1984, p.141). Several different kinds of coping strategies have been identified in the literature, which generally can be classified in one of two categories: proactive and avoidance coping (Tobin et al., Citation1989). When teachers use proactive coping, they actively try to overcome or reduce the stressor. For example, a teacher who experiences a very high level of stress from student’s exam performance may try to optimize the way of working or try to lower the workload. In contrast, when teachers use avoidance coping, they may simply refuse to acknowledge the stressor and try to avoid it.

In our review, studies generally support that proactive coping is negatively related to burnout while avoidant coping is positively related to burnout (Chan and Hui, Citation1995; Xu et al., Citation2005b; Jing, Citation2008; Meng, Citation2008). Moreover, the two coping strategies seem to have different associations with each dimension of burnout. In a survey study of 766 primary and secondary school teachers, Xu et al. (Citation2005b) reported that proactive coping has a significant negative relation with depersonalization and reduced personal accomplishment (β=-.15, −.29, respectively), while avoidant coping is positively corelated to emotional exhaustion and depersonalization (β=.09, .30, respectively). In a similar study of 724 teachers from secondary school, Meng (Citation2008) found that proactive coping is negatively associated with emotional exhaustion and reduced personal accomplishment (β=-.21, −.20, respectively), while avoidant coping has a positive relationship with all three dimensions of burnout (β=.10, .13, .20, for emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment respectively).

Regarding the role of coping in the development of burnout, avoidant coping has been examined as a mediator in the pathway through job demands to burnout (Jia and Lin, Citation2013; Zhang et al., Citation2019b). In a SEM analysis of 385 teachers, Jia and Lin (Citation2013) reported that avoidant coping amplifies the positive relationship between job stress (e.g. workloads, interpersonal stress) and burnout. They argued that when teachers face overwhelming job demands, they may appraise that the perceived demands are threatening and beyond their abilities to meet, and in turn adopt avoidant coping strategy, such as distancing from work, or ignoring their responsibility. Consequently, as the actual problem is not solved and the stressful situation remains, teachers are likely to feel exhausted, develop cynical attitudes towards work, and eventually burn out. In a similar vein, in a group of 386 teachers from primary and secondary schools, Zhang et al. (Citation2019b) found that avoidant coping also has a mediation effect, amplifying the positive relation between occupational stress (e.g. student’s exam performance, workload) and burnout.

Meanwhile, one study conceptualized both proactive and avoidant coping strategies as mediators in the pathway through job resource to burnout, with the two strategies playing distinct roles (Lin et al., Citation2009). In a survey study of 482 teachers, Lin et al. (Citation2009) showed that proactive coping amplifies the negative relationship between social support and reduced personal accomplishment, while avoidant coping ameliorates the negative relationship between social support and emotional exhaustion and depersonalization. They reasoned those teachers with adequate social support will perceive that they have access to enough resources to deal with job demands, which lead them to proactive coping. Eventually, when they make enough effort and solve problems at work, they will feel an increase sense of personal accomplishment. On the other hand, teachers who are lack of social support tend to appraise that they do not possess resources and choose to use avoidant coping strategy. When they avoid or deny their job demands, they are more likely to experience emotional depletion and become distant to people at work.

In addition, two studies extend the mediating role of proactive and avoidant coping strategies to the relationship between personal resources (e.g. self-esteem, extraversion) and burnout (Sun et al., Citation2011; Zhong and Ling, Citation2014). For example, in a survey study among 425 primary school teachers, Sun et al. (Citation2011) found that proactive coping amplifies the negative relation between self-esteem and burnout, while avoidant coping ameliorates that relationship. They provide a possible explanation that teachers with high self-esteem tend to have more confidence with their ability and are likely to employ proactive coping which in turn reduces burnout on all three dimensions. In contrast, teachers with low self-esteem believe that they have less control over their work, and may adopt avoidant coping, and this in turn increases emotional exhaustion and depersonalization.

7. Outcomes of teacher burnout in China

Studies concerning the outcomes associated with teacher burnout in China are relatively less than those on antecedents. The JD-R model posits that burnout is a mediator in the energy draining process in which chronic job demands exhaust individuals’ resources and therefore may lead to health problems and other negative organizational results (Hakanen et al., Citation2008). Specifically, burnout is positively related to teachers’ physical and mental problems, as well as decreased job performance and increased turnover intention ().

Table 5. Outcomes of teacher burnout in China.

Burnout experience has a negative influence on teachers’ physical health, mental health, and overall well-being. Using SEM analysis in a longitudinal study in which teachers’ burnout and mental health were measured at two times, Tang et al. (Citation2001) found a significant positive association between the two constructs (β=.39). Studies also indicate that the dimensions of burnout may be differently related to well-being (Luk et al., Citation2010; Yang et al., Citation2015). For example, in a survey study among 138 teachers, Luk et al. (Citation2010) found emotional exhaustion is found to be more corelated with personal health outcomes than the other two dimensions (r=-.63,-.46,.23, respectively). Yang et al. (Citation2015) found similar results in a larger sample of 460 teachers (r=-.50, −.33, −.35, respectively)

Regarding job-related outcomes, research has shown that emotional exhaustion is a significant predicator of examined job performance and turnover intention. Using objective measurements (e.g. performance appraisals from human resource departments, feedback from supervisors), Meng et al. (Citation2009) found a negative but weak association between emotional exhaustion and teachers’ job performance (β=-.17). Also, using SEM analysis, Leung and Lee (Citation2006) found a significant positive association between emotional exhaustion and teacher’s intention to quit (β=.29), while Li et al. (Citation2007a) reported a higher correlation between these constructs (β=.41).

8. Directions for future research

Building on our review, we create a conceptual framework which can be a guide for future research on teacher burnout in China. Drawing from recent development in the JD-R model, we categorize the antecedents into three groups: job demands, job resources, and personal resources. For each group, we list the variables that are most important for understanding burnout. We also highlight coping as a cognitive and behavioural strategy that can potentially be integrated into the JD-R model in burnout research of Chinese teachers. Our review shows that different coping strategies relate to job demands, job/personal resources, and burnout distinctively, leading to unique pathways toward burnout. However, we list coping strategies worth further researching instead of providing detailed pathway for each strategy, because research in this field is still limited and generates inconclusive findings. illustrate our conceptual integration derived from the JD-R model.

Our review reveals growing research interest on teacher burnout in China. However, there are still some limitations which deserve further investigation. Specifically, our conceptual framework shows that there are several opportunities for researchers to make important contributions and extend existing literature.

8.1. Job demands, job resources, and personal resources under specific cultural context

One of the unique aspects examined in this review is the culturally specific job demands under the Chinese context. However, few studies have analysed the relative impact of these job demands on burnout, especially their differential effects on the three dimensions. For instance, only two studies tested the association between pressure from student’s exam performance and specified dimensions of burnout (Xu, Citation2003; Jiao, Citation2009), while other studies analysed this demand as one of the factors in a single latent variable, which limited our understanding of the relative impact of pressure from student’s exam performance on burnout. Along this line, more empirical research is needed to examine how those specific job demands that teachers in China experience differ in forms and levels from their peers in western culture due to distinct historical and social conditions. Future research could also compare teacher groups across different culture background and identify specific burnout profiles for each group.

The review also has shown that research is lacking on the job resources that teachers in China have access to. In the burnout literature, several job resources have been found to play an important role in burnout development, including social support, feedback on performance, autonomy, and skill variety, etc. (Lee and Ashforth, Citation1996; Alarcon, Citation2011). However, apart from social support, none of those job resources is investigated among the Chinese teacher group. Compared with their western counterparts, teachers in China have limited access to some job resources due to China’s unique educational and cultural context. For example, mental health service in Chinese education system is still young and underdeveloped (Wang et al., Citation2015a). Schools seldom organize trainings on work-related emotional management, and rarely provide psychological counselling service to the teacher group (Yin and Lee, Citation2012; Ju et al., Citation2015). Also, according to Hofstede’s cross-cultural study (Hofstede et al., Citation2005), China is a country with relatively high power distance, which stresses hierarchy and group cohesion (Matsumoto, Citation1989; Zhang et al., Citation2019a). In addition, interpersonal harmony is highly valued in Chinese collectivist culture, which may lead teachers to avoid disagreement with their superiors (Fang et al., Citation2019; Chen et al., Citation2021). With these cultural characteristics, teachers are more likely to experience polarized subordinate-superior relationship at work than those in countries with lower power distance. It is possible that Chinese teachers are under the supervision of authoritative supervisors rather than supportive ones. With scarce mental health service and less support from supervisors, teachers in China lack certain job resources to cope with burnout compared with their western peers, which could explain their highest level of emotional exhaustion among 36 countries (García-Arroyo et al., Citation2019). Researchers could explore the relations between those inadequately studied job resources and burnout among Chinese teachers, and compare the findings with that of international studies.

Moreover, future studies could further explore personal resources that are likely to be influenced by cultural differences, and investigate their relations with teacher burnout in the Chinese context. For example, literature suggests that emotional intelligence may be culturally constructed, as cultural differences have a profound impact on how emotion is recognized, expressed, and managed (Mauss and Butler, Citation2010; Miyamoto and Ma, Citation2011; Yang et al., Citation2021). Specifically, when it comes to stress from work, Chinese teachers are reported to hide or suppress their negative emotions in teaching because communication of those emotions is usually regarded as a threat in Chinese culture (Yin and Lee, Citation2012). Thus, it is sensible to expect that Chinese teachers would use their emotional intelligence to deal with burnout in a different way from their peers in other cultural contexts. However, research is limited on whether or how personal resources, such as emotional intelligence, contribute to the mechanism of burnout development in a culturally specific way, and more empirical research along this line is needed.

8.2. The role of coping strategies in the JD-R model

Our review shows that it is a safe assumption that coping strategies play a role in the burnout process of Chinese teachers. However, the five studies examining coping as a mediator only links coping strategies to one job demand or resource on the one hand and burnout on the other (Jia and Lin, Citation2013; Zhang et al., Citation2019; Lin, Citation2009; Sun, Citation2011; Zhong and Ling Citation2014). To achieve a comprehensive understanding of the underlying mechanism of teacher burnout in China, it is appropriate to explore the role of coping strategies within the JD-R model, which is an overarching framework explaining the relationships of job demands, job/personal resources, and burnout. This is in line with the recent development of the JD-R model, in which researchers have made efforts to expand the role of the individual even further by integrating several individual cognitive and behavioural strategies (Bakker and Demerouti, Citation2017; Demerouti et al., Citation2019). The reason is that employees do not simply react to their work environment, they also actively take action to modify their job characteristics and influence their job tasks (Bakker and de Vries, Citation2021). Following this thought, employee behaviours such as job crafting, and self-undermining are included in recent revision of the model (Bakker and Demerouti, Citation2017). In a more comprehensive reflection on individual strategies, Demerouti et al. (Citation2019) call for research into the role of coping, recovery, self-regulation, and job crafting in the JD-R model, stating that innovation along this line could increase the predictive value of the model and better explain the complex process of employees’ wellbeing. In a similar vein, Bakker and de Vries (Citation2021) integrate several self-regulation cognitions and behaviours (coping inflexibility, self-undermining, recovery, job crafting) into the JD-R model, proposing that burnout is the result of high job demands and low resource, combined with failed self-regulation. In addition, despite being integrated into the JD-R model as a mediator, proactive coping is also found in a few studies to play a moderating role buffering the positive relationship between job demands and burnout, though more empirical evidence and theoretical explanations are need to substantiate these relationships (Jia and Lin, Citation2013; Searle and Lee, Citation2015). Thus, future research on teacher burnout in China could further investigate the role of coping strategies in the JD-R model, testing and comparing different conceptualizations of the relations between coping strategies, job demands, job/personal resources, and outcomes.

Also, different types of coping strategies are likely to further complicate the role that coping plays in JD-R model. In our review, proactive coping and avoidant coping are two distinct strategies that naturally correlate in opposite directions to teacher burnout, and they also differently associate with the three dimensions of burnout. These results are consistent with previous studies in other occupation groups (Chen and Cunradi, Citation2008; Hill et al., Citation2010; Ângelo and Chambel, Citation2014). It is possible that these two coping strategies influence burnout through different pathways. However, findings are inconclusive regarding their individual roles in the JD-R model. Moreover, the idea of coping flexibility is added to recent extension of the JD-R model (Demerouti, Citation2015; Bakker and de Vries, Citation2021). Those authors stated that proactive coping is not always better than avoidant coping, and instead coping flexibility (i.e. the ability to choose appropriate coping strategy depending on situational demands) is found to be most effective. Research along this line is needed to test and clarify how differently conceptualized coping strategies can be integrated into the JD-R model.

8.3. Thorough methodological procedure and effective intervention program

From a methodological perspective, there is a need for more rigorous research designs on teacher burnout in China. With only one exception, most of the reviewed papers relied on cross-sectional design, which would be inadequate since burnout is a process that develops with chronic stress. Also, it is not possible to infer causal relationships through such a design (Schaufeli and Enzmann, Citation1998; Rudow, Citation1999). Thus, future research on burnout in the Chinese context should consider longitudinal design to find evidence for causal effects among burnout and its correlates. Meanwhile, researchers could consider employing measurements other than the MBI to assess burnout among Chinese teachers. About 95% of the reviewed studies used MBI or its variations, despite the fact that different conceptualizations of burnout and viable alternative questionnaires are available (Demerouti et al., Citation2003; Schaufeli et al., Citation2020). For example, in their recent work, Schaufeli et al. (Citation2020) proposed a new definition for burnout and developed an associated measure, the Burnout Assessment Tool (BAT), which includes four core dimensions and three secondary dimensions. Using other validated instruments in China may provide a new perspective and contribute to a better understanding of burnout phenomenon. In addition, more diary studies should be carried out as job demands, resources, and burnout have been found to fluctuate from day to day (Butler et al., Citation2005; Ilies et al., Citation2015). There is already some evidence along this line in burnout literature (Simbula, Citation2010). However, few diary studies have been conducted among Chinese teacher groups.

When considering the practical application of teacher burnout research, there is clearly a lack of study on the intervention strategy, despite extensive empirical work on the antecedents and outcomes of burnout. None of the reviewed studies actually carry out real interventions and evaluate the efficacy of these approaches in an education setting. The scarcity of research on intervention does not result from a lack of interest, but rather from the difficulties in funding, designing and implementing these ideas (Maslach, Citation2003; Maslach and Leiter, Citation2016). However, research in this direction is of theoretical and practical importance. We need more concrete evidence, especially generated by longitudinal research, to support both theories of burnout and practices to reduce burnout.

9. Implications for HRM in the Chinese context

The findings of this review have several implications for HRM in the Chinese context aimed at enhancing employee wellbeing. In recent years, accommodating employee wellbeing and organizational performance is a key issue for HRM in China, as overwork becomes an increasing trend in many companies and jobs (Zhao et al., Citation2021; Guo et al., Citation2021). To enhance the wellbeing of the workforce, our review suggests that managers should implement HR practices that alleviate burnout through decreasing job demands or increasing job resources. For example, considering that coping strategies play an important role in the association between job demands and burnout, managers are advised to provide training programs on how to use a variety of coping strategies to manage different job demands. When employees adopt less avoidant coping and more proactive coping, they are more capable to deal with those demands and less likely to experience burnout. Another effective strategy is to enhance their job resources by encouraging leaders or supervisors to offer adequate feedback and employees to build a strong social network among colleagues. Employees who have access to those resources are less likely to experience burnout. These implications are also consistent with the findings of international HRM research, which indicates that HR practices, such as on-the-job training (Taris et al., Citation2003), HR involvement system (Castanheira and Chambel, Citation2010), HRM system consistency (Xiao et al., Citation2022), can influence job demands and resources, and may have an indirect impact on burnout.

The implications of our study are based on findings from teaching profession. In China, teachers are among those workgroups with the highest level of burnout, and their job is deeply influenced by the Chinese traditional culture, which shapes their culturally specific burnout profile. A comprehensive review on teacher burnout in China could provide valuable insights to HRM practices in the Chinese context in general, particularly to those workgroups with high risk of burnout.

10. Conclusion

This study provides a comprehensive review on teacher burnout research in the Chinese context under the JD-R framework. It makes a number of contributions to the literature of teacher burnout and burnout research at large. Firstly, we construct an integrated conceptual framework of teacher burnout in China based on empirically validated factors and their relationships. Specifically, we systematically identify the job demands, job/personal resources, and outcomes of teacher burnout in the Chinese context. We find that some job demands contributing to Chinese teacher burnout are culturally specific while some key resources are not adequately examined in this context, which suggests that a more contextualized analysis of burnout is worthwhile. Secondly, we discuss how proactive and avoidance coping contribute to the burnout process in the Chinese teacher group. Specifically, we review on the role coping strategies play in the relationships between job demands, job/personal resources, and burnout. Thirdly, this review highlights the gaps in our understanding of teacher burnout research in China. Firstly, future works might examine how national culture influence the development of burnout, and make comparisons among cross culture samples. Secondly, researchers should explore the role of different coping strategies in Chinese teacher burnout under the JD-R framework. Thirdly, we notice the scarcity of rigorous research design such as longitudinal and diary study in teacher burnout field, and point out the need of intervention studies as a valuable practical application. Finally, we contribute to the literature by highlighting the implications of our study for HRM in the Chinese context.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in CNKI at https://chn.oversea.cnki.net/index/, ERIC at https://eric.ed.gov/, and EBSCO at https://www.ebsco.com/.

References

- Alarcon, G. M. (2011). A meta-analysis of burnout with job demands, resources, and attitudes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79(2), 549–562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2011.03.007

- Ângelo, R. P., & Chambel, M. J. (2014). The role of proactive coping in the Job Demands–Resources Model: A cross-section study with firefighters. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 23(2), 203–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2012.728701

- Bakker, A. B., & de Vries, J. D. (2021). Job Demands-Resources theory and self-regulation: New explanations and remedies for job burnout. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 34(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2020.1797695

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 273–285.

- Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Euwema, M. C. (2005). Job resources buffer the impact of job demands on burnout. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 10(2), 170–180.

- Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Sanz-Vergel, A. I. (2014). Burnout and work engagement: The JD–R approach. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 389–411. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091235

- Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Verbeke, W. (2004). Using the job demands‐resources model to predict burnout and performance. Human Resource Management, 43(1), 83–104. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20004

- Bianchi, R., Schonfeld, I. S., & Laurent, E. (2019). Burnout: Moving beyond the status quo. International Journal of Stress Management, 26(1), 36–45. https://doi.org/10.1037/str0000088

- Boreen, J., Niday, D., & Johnson, M. K. (2003). Mentoring across boundaries: Helping beginning teachers succeed in challenging situations. Stenhouse Publishers.

- Butler, A., Grzywacz, J., Bass, B., & Linney, K. (2005). Extending the demands‐control model: A daily diary study of job characteristics, work‐family conflict and work‐family facilitation. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 78(2), 155–169. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317905X40097

- Cai, H., & Zhu, A. (2013). A study on burnout and its influencing factors among secondary shcool teachers. Educational Research and Experiment (6), 29–33.

- Cao, Y., Postareff, l., Lindblom, S., & Toom, A. (2018). Teacher educators’ approaches to teaching and the nexus with self-efficacy and burnout: Examples from two teachers’ universities in China. Journal of Education for Teaching, 44(4), 479–495.

- Cortazzi, M.,& Jin, L. (2002). Communication for learning across cultures. In Overseas students in higher education (pp. 88-102). Routledge.

- Castanheira, F., & Chambel, M. J. (2010). Reducing burnout in call centers through HR practices. Human Resource Management, 49(6), 1047–1065. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20393

- Chan, D. W. (2003). Hardiness and its role in the stress–burnout relationship among prospective Chinese teachers in Hong Kong. Teaching and Teacher Education, 19(4), 381–395.

- Chan, D. W. (2006). Emotional intelligence and components of burnout among Chinese secondary school teachers in Hong Kong. Teaching and Teacher Education, 22(8), 1042–1054. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2006.04.005

- Chan, D. W. (2007). Burnout, self-efficacy, and successful intelligence among chinese Prospective and in-service school teachers in Hong Kong. Educational Psychology, 27(1), 33–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410601061397

- Chan, D. W., & HUI, E. K. P. (1995). Burnout and coping among Chinese secondary school teachers in Hong Kong. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 65(1), 15–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.1995.tb01128.x

- Chen, M.-J., & CUNRADI, C. (2008). Job stress, burnout and substance use among urban transit operators: The potential mediating role of coping behaviour. Work & Stress, 22(4), 327–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370802573992

- Chen, S., Fan, Y., Zhang, G., & Zhang, Y. (2021). Collectivism-oriented human resource management on team creativity: Effects of interpersonal harmony and human resource management strength. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 32(18), 3805–3832. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2019.1640765

- Cherniss, C. (1993). Role of professional self-efficacy in the etiology and amelioration of burnout. In: W. B. Schaufeli, C. Maslach & Marek, T. (Eds.), Series in applied psychology: Social issues and questions. Professional burnout: Recent developments in theory and research. Taylor & Francis.

- Cheung, F., Tang, C. S., & Tang, S. (2011). Psychological capital as a moderator between emotional labor, burnout, and job satisfaction among school teachers in China. International Journal of Stress Management, 18(4), 348–371.

- Cortazzi, M., & Jin, L. (1997). Communication for learning across cultures. Overseas Students in Higher Education, 76–90.

- Demerouti, E. (2015). Strategies used by individuals to prevent burnout. European Journal of Clinical Investigation, 45(10), 1106–1112.

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499

- Demerouti, E., Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Vardakou, I., & Kantas, A. (2003). The convergent validity of two burnout instruments: A multitrait-multimethod analysis. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 19(1), 12–23. https://doi.org/10.1027//1015-5759.19.1.12

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., & Xanthopoulou, D. (2019). Job Demands-Resources theory and the role of individual cognitive and behavioral strategies. Pelckmans Pro.

- Dong, Z., Li, R., & Zhou, J. (2020). The effect of materialism on job burnout in primary and middle schools teachers: The mediating role of social comparison. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 28(2), 274–276.

- Fang, T., GE, Y., & Fan, Y. (2019). Unions and the productivity performance of multinational enterprises: evidence from China. Asian Business & Management, 18(4), 281–300. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41291-018-00052-0

- Farber, B. A. (1991). Crisis in education: Stress and burnout in the American teacher. San Francisco.

- Gan, Y., Wang, X., & Zhang, Y.Zhang, Y. (2006). Job characteristics that affecting job burnout among secondary school teachers in China’s rural area. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 38(1), 92–98.

- García-Arroyo, J. A., Osca Segovia, A., & Peiró, J. M. (2019). Meta-analytical review of teacher burnout across 36 societies: The role of national learning assessments and gender egalitarianism. Psychology & Health, 34(6), 733–753. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2019.1568013

- GUO, R. (2017). A study of teaching efficacy, job burnout and their relationship of teachers of Chinese as a foreign language. Language Teaching and Linguistic Studies, (2), 47–56.

- Guo, W., Chen, L., Fan, Y., Liu, M., & Jiang, F. (2021). Effect of ambient air quality on subjective well-being among Chinese working adults. Journal of Cleaner Production, 296, 126509.

- Hakanen, J. J., Bakker, A. B., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2006). Burnout and work engagement among teachers. Journal of School Psychology, 43(6), 495–513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2005.11.001

- Hakanen, J. J., Schaufeli, W. B., & Ahola, K. (2008). The Job Demands-Resources model: A three-year cross-lagged study of burnout, depression, commitment, and work engagement. Work & Stress, 22(3), 224–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370802379432

- Halbesleben, J. R. (2006). Sources of social support and burnout: a meta-analytic test of the conservation of resources model. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(5), 1134–1145.

- Hao, M. (2008). Study of the status of occupational ennui of college physical education teachers in Henan province and its relation with the occupational self concept. Journal of Physical Education, 15, 63–66.

- Hill, A. P., Hall, H. K., & Appleton, P. R. (2010). Perfectionism and athlete burnout in junior elite athletes: The mediating role of coping tendencies. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 23(4), 415–430. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615800903330966

- Ho, S. K. (2016). Relationships among humour, self-esteem, and social support to burnout in school teachers. Social Psychology of Education, 19(1), 41–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-015-9309-7

- Hobfoll, S. E., Johnson, R. J., Ennis, N., & Jackson, A. P. (2003). Resource loss, resource gain, and emotional outcomes among inner city women. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(3), 632–643.

- Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2005). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. Mcgraw-hill New York.

- Holland, P. J., Allen, B. C., & Cooper, B. K. (2013). Reducing burnout in Australian nurses: The role of employee direct voice and managerial responsiveness. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(16), 3146–3162. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2013.775032

- Hong, J. Y. (2012). Why do some beginning teachers leave the school, and others stay? Understanding teacher resilience through psychological lenses. Teachers and Teaching, 18(4), 417–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2012.696044

- Hu, W., & Zhao, H. (2019). A study on the influence of five personalities of vocational college teachers on job burnuut in Northwest. Qinghai Journal of Ethnology, 20(4), 50–55.

- Ilies, R., AW, S. S., & Pluut, H. (2015). Intraindividual models of employee well-being: What have we learned and where do we go from here? European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 24(6), 827–838. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2015.1071422

- Jia, X., & Lin, C. (2013). Relationship of university teachers’ stress and coping style with job burnout. Studies of Psychology and Behavior, 11, 759–764.

- Jiang, H., Sun, P., & Yu, Z. (2013). The relationship between teachers’ psychological capital and burnout symptoms in radio and TV universities. Open Education Research, 19(1), 48–52.

- Jiao, Z. (2009). Research on the occupational pressure, teaching efficacy and occupational burnout among P.E. teachers in primary and middle Schools. Journal of Chengdu Sport University, 35, 84–87.

- Jing, L. (2008). College P.E. teachers’ occupational tiredness and its influences–A survey in. Wuhan. Journal of Wuhan Institute of Physical Education, 42, 82–85.

- Ju, C., Lan, J., Li, Y., Feng, W., & You, X. (2015). The mediating role of workplace social support on the relationship between trait emotional intelligence and teacher burnout. Teaching and Teacher Education, 51, 58–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2015.06.001

- Kang, Y., & Qu, Z. (2011). Vocational and technical college teachers’ psychological contract and job burnout: The mediating role of job satisfaction. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 19(2), 234–236.

- Kim, L. E., Jörg, V., & Klassen, R. M. (2019). A meta-analysis of the effects of teacher personality on teacher effectiveness and burnout. Educational Psychology Review, 31(1), 163–195.

- Kyriacou, C. (2001). Teacher stress: Directions for future research. Educational Review, 53(1), 27–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131910120033628

- Lau, P. S., Yuen, M. T., & Chan, R. M. (2005). Do demographic characteristics make a difference to burnout among Hong Kong secondary school teachers?. In Quality-of-life Research In Chinese, Western and Global Contexts. Springer.

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer Publishing Company.

- Lee, J. S., & Akhtar, S. (2007). Job burnout among nurses in Hong Kong: Implications for human resource practices and interventions. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 45(1), 63–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/1038411107073604

- Lee, R. T., & Ashforth, B. E. (1996). A meta-analytic examination of the correlates of the three dimensions of job burnout. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 81(2), 123–133.

- Leung, D. Y. P., & Lee, W. W. S. (2006). Predicting intention to quit among Chinese teachers: Differential predictability of the components of burnout. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 19(2), 129–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615800600565476

- Li, Y., & Zhang, J. (2020). The influence of environmental factors on college English teachers’ job burnout. Education Science, 36(2), 71–75.

- Li, M., Wang, Z., & Liu, Y. (2015). Work family conflicts and job burnout in primary and middle school teachers: The mediator role of self-determination motivation. Psychological Development and Education, 31(3), 368–376.

- Li, Y., & Yong, J. (2010). Relationship model of teachers’ occupational commitment, teaching efficacy and job burnout in primary and middle schools. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 18(3), 360–362.

- Li, C., & Shi, K. (2003). The influence of distributive justice and procedural justice on job burnout. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 35, 677–684.

- Li, C., & Wang, H. (2009). Relationship between time management and job burnout of teachers. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 11, 107–109.

- Li, L. (2012). The research on teachers’ job burnout and social support for newly built university. Journal of Educational Science of Hunan Normal University, 11, 77–79.

- Li, Y., Gao, D., & Shen, J. (2007a). Relationship among job burnout, self-esteem, mental health and intention to quit in teachers. Psychological Development and Education, 23(4), 83–87.

- Li, Y., & Wu, M. (2005). Developing the job burnout inventory. Psychological Science, 28, 454–457.

- Li, Y., Yang, X., & Shen, J. (2007b). The relationship between teachers’ sense of teaching efficacy and job burnout. Psychological Science, 30, 952–954.

- LI, Z., Ren, X., Lin, L., & Shi, K. (2008). Stressors, teaching efficacy, and burnout among secondary school teachers. Psychological Science, 31, 218–221.

- Lin, D., Chen, X., & Zhai, D. (2009). Job burnout and its relationship with social support and coping style among the communist youth league cadres in middle schools. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 17, 498–500.

- Liu, Y., Wu, Y., & Xing, Q. (2009). The influences of teacher’s stress on job burnout: The moderating effect of teaching efficacy. Psychological Development and Education, 25(1), 108–113.

- Liu, P. (2014). A comprehensive research about the relationship of college English teachers’ self-efficacy and job burnout. Foreign Language Education, 35(6), 68–82.

- Liu, J., & Fu, D. (2013). Relationships of occupational burnout and psychological health: The Intermediary and regulatory role of psychological capital structure. Studies of Psychology and Behavior, 11(6), 765–769.

- Liu, X. (2004). Relationships between professional stress, teaching efficacy and burnout among primary and secondary school teachers. Psychological Development and Education, 20(2), 56–61.

- Liu, X., Wang, L., Jin, H., & Qin, H. (2008). Mechanism of occupational stress on job burnout of primary and middle school teachers. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 16, 537–539.

- Loerbroks, A., Meng, H., Chen, M. L., Herr, R., Angerer, P., & Li, J. (2014). Primary school teachers in China: associations of organizational justice and effort-reward imbalance with burnout and intentions to leave the profession in a cross-sectional sample. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 87(7), 695–703.

- Lu, Y., He, F., Feng, L., & Luan, Z. (2012). A study on work-family conflict types of primary school teachers and their characteristics in burnout. Teacher Education Research, 24(3), 68–73.

- Luk, A. L., Chan, B. P. S., Cheong, S. W., & Ko, S. K. K. (2010). An exploration of the burnout situation on teachers in two schools in Macau. Social Indicators Research, 95(3), 489–502.

- Ma, C. (2018). The effect of job burnout on mental health of primary and secondary boarding school teachers in Tibetan-inhibited areas of Qinghai. Journal of Research on Education for Ethnic Minorities, 29(2), 31–38.

- Mao, J., & Mo, T. (2014). Relationship among psychology capital, emotional labor strategies and job burnout of primary and secondary school teachers. Teacher Education Research, 26(5), 22–28.

- Maslach, C. (2003). Job burnout: New directions in research and intervention. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12(5), 189–192. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.01258

- Maslach, C. (2017). Finding solutions to the problem of burnout. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 69(2), 143–152. https://doi.org/10.1037/cpb0000090

- Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1986). Maslach burnout inventory manual (2nd ed.). Consulting Psychologists Press.

- Maslach, C., Jackson, S. E., & Leiter, M. P. (1996). MBI: Maslach burnout inventory. CPP, Incorporated Sunnyvale.

- Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (1999). Teacher burnout: A research agenda. In Vandenberghe, R. & Huberman, A. M. (Eds.), Understanding and preventing teacher burnout: A sourcebook of international research and practice (pp. 295–303). Cambridge University Press.

- Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (2008). Early predictors of job burnout and engagement. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(3), 498–512.

- Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (2016). Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry: Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 15(2), 103–111.

- Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 397–422.

- Matsumoto, D. (1989). Cultural influences on the perception of emotion. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 20(1), 92–105. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022189201006

- Mauss, I. B., & Butler, E. A. (2010). Cultural context moderates the relationship between emotion control values and cardiovascular challenge versus threat responses. Biological Psychology, 84(3), 521–530.

- Meng, H., Chen, Y., L. I., Y., & Xiong, M. (2009). The relationship of personality with job stress and burnout: Evidence from a sample of teachers. Psychological Science, 32, 846–849.

- Meng, Y. (2008). Studies of the relationship of secondary school teachers’ coping style and teaching efficacy with professional burnout. Psychological Science, 31, 738–740.

- Mérida-López, S., & Extremera, N. (2017). Emotional intelligence and teacher burnout: A systematic review. International Journal of Educational Research, 85, 121–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2017.07.006

- Ministry of Education of People’s Republic of China. (2017). Educational statistics in 2017. Retrieved December 19, 2018, from http://en.moe.gov.cn/Resources/Statistics/edu_stat2017/national/.

- Miyamoto, Y., & Ma, X. (2011). Dampening or savoring positive emotions: A dialectical cultural script guides emotion regulation. Emotion (Washington, D.C.), 11(6), 1346–1357. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025135

- Pan, X., Tan, X., Qin, Q., & Wang, L. (2010). Teacher’s perceived organization justice and organizational citizenship behavior: The mediating role of job burnout. Psychological Development and Education, 26(4), 409–415.

- Pang, W. S. (1999). The three character classic. Shui Sing. (In Chinese).

- Pietarinen, J., Pyhältö, K., & Soini, T., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2013). Reducing teacher burnout: A socio-contextual approach. Teaching and Teacher Education, 35, 62–72.

- Pithers, R., & Soden, R. (1998). Scottish and Australian teacher stress and strain: A comparative study. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 68(2), 269–279. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.1998.tb01289.x

- Rudow, B. (1999). Stress and burnout in the teaching profession: European studies, issues, and research perspectives. In Vandenberghe, R. & Huberman, A. M. (Eds.), Understanding and preventing teacher burnout: A sourcebook of international research and practice. Cambridge University Press.

- Schaufeli, W., & Enzmann, D. (1998). The burnout companion to study and practice: A critical analysis. Taylor & Francis.

- Schaufeli, W. B., Desart, S., & de Witte, H. (2020). Burnout Assessment Tool (BAT)—Development, validity, and reliability. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(24), 9495. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249495

- Schaufeli, W. B., & Taris, T. W. (2014). A critical review of the job demands-resources model: Implications for improving work and health. In Bridging occupational, organizational and public health. Springer.

- Searle, B. J., & Lee, L. (2015). Proactive coping as a personal resource in the expanded job demands–resources model. International Journal of Stress Management, 22(1), 46–69. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038439

- Shen, J., & Li, Y. (2009). The relationship among teachers’ personality, organizational identification and job burnout. Psychological Science, 32(4), 774–777.

- Simbula, S. (2010). Daily fluctuations in teachers’ well-being: A diary study using the Job Demands–Resources model. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 23(5), 563–584.

- SINA. (2005). Occupational stress and mental health survey among Chinese teachers. Retrieved November 29, 2018, from http://edu.sina.com.cn/l/2005-09-09/1653126581.html.

- Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2017). Dimensions of teacher burnout: Relations with potential stressors at school. Social Psychology of Education, 20(4), 775–790. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-017-9391-0

- Song, Z. (2008). Current situation of job burnout of junior high school teachers in Shangqiu urban areas and its relationship with social support. Frontiers of Education in China, 3(2), 295–309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11516-008-0019-1

- Stankevičiūtė, Ž., & Savanevičienė, A. (2019). Can sustainable HRM reduce work-related stress, work-family conflict, and burnout? International Studies of Management & Organization, 49(1), 79–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/00208825.2019.1565095

- Stoeber, J., & Rennert, D. (2008). Perfectionism in school teachers: Relations with stress appraisals, coping styles, and burnout. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 21(1), 37–53.

- Sun, P., Zheng, X., Xu, Q., & Y. U., Z. (2011). Relationship between core self-evaluation, coping style and job burnout among primary teachers. Psychological Development and Education, 27(2), 188–194.

- Tang, C. S. K., Au, W. T., Schwarzer, R., & Schmitz, G. (2001). Mental health outcomes of job stress among Chinese teachers: Role of stress resource factors and burnout. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22(8), 887–901. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.120

- Taris, T. W., Kompier, M. A., Geurts, S. A., Schreurs, P. J., Schaufeli, W. B., de Boer, E., Sepmeijer, K. J., & Watterz, C. (2003). Stress management interventions in the Dutch domiciliary care sector: Findings from 81 organizations. International Journal of Stress Management, 10(4), 297–325. https://doi.org/10.1037/1072-5245.10.4.297

- Taylor, S. E., Sherman, D. K., Kim, H. S., Jarcho, J., Takagi, K., & Dunagan, M. S. (2004). Culture and social support: Who seeks it and why? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(3), 354–362. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.87.3.354

- Tian, B., & Li, L. (2006). The influence of school organizational climate on job burnout. Psychological Science, 29(1), 189–193.

- Tobin, D. L., Holroyd, K. A., Reynolds, R. V., & Wigal, J. K. (1989). The hierarchical factor structure of the Coping Strategies Inventory. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 13(4), 343–361. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01173478

- Wang, X., Zhang, Y., & Gan, Y., Zhang, Y. (2005). Development of job burnout inventory for middle school teachers. Chinese Journal of Applied Psychology, 11(2), 170–175.

- Wang, W., & Liu, X. (2020). Job characteristics and job burnout of PE teachers in primary and secondary schools: a chain mediation of self-determination and job exuberance. Journal of Shenyang Sport University, 39(1), 29–38.

- Wang, C., Ni, H., Ding, Y., & Yi, C. (2015). Chinese teachers’ perceptions of the roles and functions of school psychological service providers in Beijing. School Psychology International, 36(1), 77–93.

- Wang, L. (2009). The effects of schooI organizational fairness on teachers’ job burnout. Psychological Science, 32(6), 1491–1496.