Abstract

The year 2023 witnessed intensified geopolitical tensions, military conflicts, and international economic sanctions, with heightened risks and uncertainties for businesses, especially multinational enterprises. In this editorial for 2024, we focus on two phenomena—international sanction and mental health—as critical issues for human resource management research and practice. These two issues are closely related to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (Goal 3: Good health and wellbeing and Goal 16: Peace, justice and strong institutions). We draw on dynamic capability theory to illustrate how organizations can develop corporate capabilities to survive and thrive in a volatile global business environment. We suggest sets of research questions to inform policy decisions and practice. We also outline practical implications for human resource professionals.

Introduction

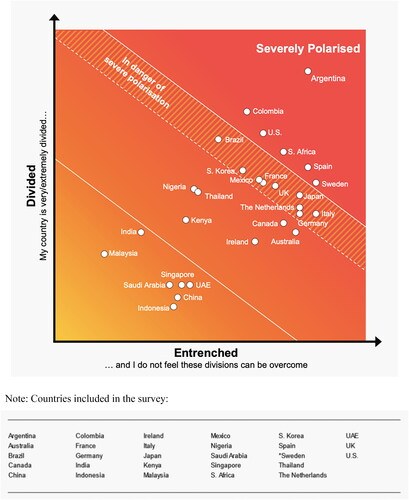

The year 2023 witnessed the continuing and deepening tensions of geopolitics with economic, financial, technological, social, and humanitarian implications on a global scale. As nation states are grabbling with the difficult economic recovery post-Covid-19, businesses, especially multinational enterprises (MNEs), are hampered by not only the impacts of geopolitical tensions (e.g. Cui et al., Citation2023; Melin et al., Citation2023), but also on-going and emerging challenges that affect human resource management (HRM). According to the 2023 Edelman Trust Barometer Global Report which surveyed 32,000 respondents from 28 countries (Edelman Trust Barometer Global Report, Citation2023), the world is increasingly divided with some countries becoming more polarized than others (see ). For example, the survey shows that ‘Australians are more divided than ever on social issues’ (Riches, Citation2023, n. p.). The report also suggests that wealth disparity, the media, and government leaders were the main driving forces for the polarization (Edelman Trust Barometer Global Report, Citation2023). This polarization could be harmful to employees and businesses because it is prone to negative workplace behaviour such as favouritism, prejudice, incivility, discrimination, and victimization (Riches, Citation2023).

Figure 1. How polarized are the 28 survey countries?.

Source: Edelman Trust Barometer Global Report (Citation2023, p. 16 for ; p. 2 for the list of countries included in the survey)

In our 2023 editorial (Cooke et al., Citation2023), we presented an integrated overview of HRM research trends that incorporated four key perspectives: employee-oriented, firm-oriented, tech-oriented, and society-oriented HR investigations. The framework that we presented then has raised substantial interest and we are confident that it can give researchers relevant insights and guidance. Given some of the major geopolitical, technological, and societal developments in the meantime, we want to concentrate on two key issues—international sanctions and mental health—in our 2024 editorial. Both issues are closely related to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, namely, Goal 3: Good health and wellbeing—Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages, and Goal 16: Peace, justice and strong institutions—Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development (United Nations, Citationn.p.). We draw on dynamic capability theory to illustrate how organizations can develop corporate capabilities to survive and thrive in a volatile global business environment. We outline some HRM issues and propose research agendas that have policy and practical implications. We also outline practical implications for human resource professionals. We emphasise up front that the challenges and research directions we identify in this editorial are indicative, rather than exhaustive, to spark further interest and attention to advance the field of research and inform practice.

Geopolitical tensions, dynamic capabilities and implications for HRM

In our 2023 editorial (Cooke et al., Citation2023), we touch upon the topic of international economic sanctions. One year on, geopolitical tensions and sanctions have intensified dramatically, with the Russia-Ukraine war continuing and the Isreal-Hamas military conflict dragging more and more nation states into it. These conflicts and sanctions have significant economic and humanitarian impacts as well as leading to disruptions to businesses.

Economic sanctions are restrictions over economic activities “imposed by one international actor on another with a specific purpose” or a combination of different purposes, such as signalling, coercing a behavioural change, or constraining one’s behaviour (Özdamar & Shahin, Citation2021, p. 1648). They affect the development, mobility, utilization, and retention of human resources, with domestic, regional, and global impact and HRM implications. In particular, economic sanctions have a definitive negative impact on the quality and quantity of human resource supply in the target country that receives the sanction, which is manifested in two main ways.

First, economic sanctions reduce the financial resources of the sanctioned state to provide quality education and other public welfare (e.g. healthcare) for human capital development at the macro level. It also prevents the target country (often developing countries) from receiving education and training support from institutions from the sending country and its allies (Kokabisaghi et al., Citation2019; Ronaghy & Shajari, Citation2013). Second, uncertainties and politico-economic instabilities of the sanctioned country inflict upon the citizens a high level of stress and financial hardship, pushing well-educated elites to emigrate from the country through professional immigration initiatives or by pursuing higher-degree education in developed countries and then stay, as has been seen in Iran, Iraq, Myanmar, Georgia, and many African countries (e.g. Cooke, Citation2022; Malik et al., Citation2014; Newnham, Citation2015; Ronaghy & Shajari, Citation2013; Steinberg, Citation2010). As Steinberg (Citation2010, p. 177) pointed out, ‘two generations of educated young people have left [Myanmar] for both economic and political reasons’ and ‘robbed the state of just the talents needed for growth’ and development activities.

Impoverished and with limited employment prospects, less well-educated citizens may also seek various channels (e.g. seeking refugee status and human trafficking) to leave their home country, causing a high level of international mobility of people and the labour force. Although they also generate income for the target country by sending remittance home, their departure from their home country, albeit primarily in the form of temporary migration, also means a serious brain/labour power drain. These push and pull factors deplete the pool of human resources in the target country, making it difficult for firms to hire qualified staff (Tasavori et al., Citation2021).

So, how could firms affected by international sanctions and regional conflicts directly and indirectly respond to maintain their operations successfully? One suggestion is to develop dynamic capabilities to reverse the negative impact because the organizational capabilities they possess during peace times may not be sufficient. Teece et al. (Citation1997, p. 516) define dynamic capabilities as firms ‘capacity to renew competencies so as to achieve congruence with the changing business environment’ by ‘adapting, integrating, and reconfiguring internal and external organizational skills, resources, and functional competencies’. The concept of dynamic capabilities argues that what matters for business is corporate agility, that is, the capacity to (1) sense and shape opportunities and threats, (2) seize opportunities, and (3) maintain competitiveness through enhancing, combining, protecting, and, when necessary, reconfiguring the business enterprise’s intangible and tangible assets (Teece et al., Citation1997).

Dynamic capability theory emphasizes organizational adaptability and organizational learning in rapidly changing and precarious business environments to sustain and develop critical resources (Zahra et al., Citation2022). The radical impact on the business environment means that MNEs need to reconfigure their intangible and tangible assets to survive and thrive. People and brand reputation are intangible assets. Moreover, for firms to be able to sense and shape opportunities and threats, seize opportunities, and maintain competitiveness, they need to develop their corporate competencies through their people.

One of the ways that firms can advance their practices could be by working towards more agile talent management. While talent management is undoubtedly important for firm and individual success (Collings & Mellahi, Citation2009) traditional talent management approaches have been criticized for not outlining sufficiently how they could support the strategic agility and capability of firms that is needed in highly dynamic contexts (Farndale et al., Citation2021; Harsch & Festing, Citation2020). The pandemic has created a range of reactions from individuals and organizations that have led to a focus on increased technological use of tools and diverse patterns of domestic and international work (Caligiuri et al., Citation2020; Selmer et al., Citation2021). More emphasis is now devoted to organizational resilience which incorporates a move towards more agile working and staffing patterns (Harsch & Festing, Citation2020; Jooss et al., Citation2024). We are witnessing drastic changes in working patterns, staffing shifts and the fine-tuning of competitive approaches. Many exciting avenues for further research as to the individual, organizational, national and societal effects over time are emerging, including managing people in the context of heightened geopolitical tensions.

Although dynamic capability theory has been increasingly applied in international business research, with a focus on how to gain organizational competitive advantage (e.g. Forsgren & Yamin, Citation2023; Kaur, Citation2022; Pitelis & Teece, Citation2010; Teece, Citation2014; Zahra et al., Citation2022), much of the scholarship has focused on how MNEs can develop their dynamic capabilities globally in times of peace implicitly (Dunning & Lundan, Citation2010, see also Pitelis et al., Citation2023 for a systematic review). This scholarship has yet to be expanded to the context of international economic sanctions to examine how firms can adapt to the turbulent global business environment by developing capabilities to identify risks, build competencies, and generate new resources. Similarly, few studies have applied dynamic capability theory in the HRM field (Festing & Eidems, Citation2011; Tasavori et al., Citation2021), and even fewer have applied the theory explicitly to shed light on HRM issues as a result of international sanctions and geopolitical conflicts. Tasavori et al. (Citation2021) study was about HRM in MNEs operating in Iran as a precarious context, but not MNEs operating outside the sanctioned country and the HRM issues they might be confronted with as a result of the sanction. We therefore encourage researchers to examine the implications of geopolitics and international sanctions on firms in and outside the target country, especially MNEs, and HRM implications from the dynamic capability perspective.

For example, what may be the risks associated with HRM in international sanctions? What HRM policy should be put in place to manage these risks? What kinds of support and protection can be provided to the employees, especially those who are captive victims of international disputes (e.g. ship crew members), and how? How can MNEs identify and develop new skills and competencies for their existing workforce to reverse the negative impact of sanctions on their business? How do MNEs make sure that their HRM practices do not violate human rights in conflict zones/sanctioned areas? For MNEs that plan to continue their operations in the sanctioned country by (partially) adopting the remote work arrangement, what legal requirements, e.g. immigration, tax, and employment laws, of the sanctioned country need to be complied with? How can MNEs develop a psychologically safe work environment for the global workforce, given the increasingly polarized world and workplaces?

The literature on working in hostile environments provides useful insights as to the potential dimensions of dangers to individuals (and their families) moving and working abroad. The predominant focus of the work in this area is physical hostilities with a range of repercussions related to the continued operations of organizations and their resilience as well as the duty of care towards staff and their loved ones (Bader et al., Citation2020). Some authors also concentrate on the psychological impacts of heightened dangers including anxiety, stress, and other forms of diminished well-being. More neglected areas of research in hostile contexts—independent of whether this is in sanctioned or unsanctioned countries—would include foci on interactional and institutional hostilities (Raupp, Citation2023) and a stronger embedding of perspectives on domestic actors such as host colleagues or other important local actors.

For domestic firms in a sanctioned country, they may face different challenges to firms operating outside the country or foreign MNEs. Gaur et al. (Citation2023) study of the impact of sanctions on Russian firms suggests that the negative economic effect is not long-lasting as firms will respond with strategic actions and develop capabilities to eliminate the impact. To what extent, if so, and how, is HRM part of the strategic response? What kind of new skills and competencies are required for the management team and the workforce?

Mental health and implications for HRM

Triggered by the momental geopolitical and competitive developments in the past months, we have looked at the broad issues above. But there are important challenges much closer to home for many of us, in part caused by unsettling political, economic, and social tensions and uncertainties globally and domestically. The mental health challenges that our societies experience have far too grave an impact on individuals, families, and society to be ignored and this is why we spotlight mental health issues in this part of our editorial.

It is believed that approximately 1/6 adults experience mental health issues worldwide, many of whom are of working age, and that some 12 billion working days are lost every year to depression and anxiety at a cost of US$ 1 trillion per year in lost productivity globally (World Health Organization [WHO], Citation2022). According to the Health and Wellbeing at Work Report published by the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD) and Simplyhealth, workplace absences have risen to the highest levels in a decade in the UK (Mayne, Citation2023). Specifically, employees were absent an average of 7.8 days, the highest level seen in a decade and two whole days more than the pre-pandemic rate of 5.8 days, and mental ill health was the third most prevalent reason (39%) for short-term sickness absences but the top reason (63%) for long-term sickness absence (Mayne, Citation2023). According to Safe Work Australia, ‘mental stress is the most common reason for serious workplace injury claims related to mental health, resulting in over 11,000 claims from 2020 to 2021 alone (Armstrong, Citation2023, n. p.).

While there are many reasons why an individual suffers from mental ill health, stigma, and discrimination have been widely reported to be the main barriers for individuals to seek help (e.g. Elraz, Citation2018), especially in societies with strong work ethics and masculine culture (e.g. Cooke & Xu, Citation2023). Many organizations have yet to strike the balance of stretching their employees (good stress/eustress) without pushing their employees too far (bad stress/distress).

Research on mental health to date has mainly been conducted in the psychology and healthcare field (see Follmer & Jones, Citation2018 for a comprehensive review), although attention to this important topic is emerging from the HRM discipline (e.g. Cavanagh et al., Citation2017; Hastuti & Timming, Citation2021, Citation2023; Hennekam et al., Citation2021; Suter et al., Citation2022). Much research is still needed to shed light on this significant issue that impacts individuals, workplaces, families and society. For example, why do some employees have better mental health than others? What are the workplace causes of employees’ mental ill health? To what extent does increased workplace control through the use of digital technology and algorithmic management increase contribute to employee mental ill health? What may be the spillover effects between work and life? To what extent, and how, do remote work and hybrid work exacerbate or alleviate employee mental ill health? What can organizations do to develop a better understanding of these problems and develop HR interventions to provide tailored support to their employees? What may be the stumbling blocks to the effective implementation of these HR interventions? How can organizations increase workplace mental health knowledge and managerial competence in managing employee mental health? What role do and can HR professionals play in managing employee mental health? What may be the individual coping mechanisms of mental ill health, and how are they manifested at work, and with what consequences? What are the institutional, economic, technological, and cultural characteristics that underpin mental health problems in the workforce and influence potential interventions in different societal contexts?

These issues are closely connected to sustainable careers. Indicators of sustainable careers include health, happiness, and productivity (De Vos et al., Citation2020). Health is conceptualized by both mental and physical health and individuals look towards assessing their fluctuating health state to fit to their own physical and mental capabilities. Careerists, of course, have their own life and career goals, driven by their own values and needs. Given their various experiences in their working lives, the fit of such goals, values and needs to how their careers are unfolding is related to their happiness. Lastly, individuals’ job performance, internal and external marketability as well as career potential are linked to their productivity (De Vos et al., Citation2020). While the argument around protean careers (Briscoe & Hall, Citation2006) has indicated a shift towards individuals as the primary careerists, organizations still shape much of the context.

For example, how do organizational activities, such as restructuring, strategy changes, moves towards more agile, and skills-based staffing approaches in response to the external environment, result in career shocks and, thereby, impact the sustainability of individuals’ careers? How do firms plan, communicate, and enact changes that lead to career transitions and how do they support individuals to augment the sustainability of their careers? How do different institutional arrangements, for example, those that are conceptualized in different varieties of capitalism, impact sustainable careers where liberal market economies might be characterized by more frequent and more substantial career shocks for individuals than coordinated market economies? And what about sustainable global careers? What impact do international moves, characterized by substantial changes and a high-density learning experience (Mello et al., Citation2023) have on the productivity, health, and happiness of expatriates? In short, there are many exciting research avenues in relation to sustainable careers and their impact on individuals and organizations, as well as national contexts.

Conclusions

In this editorial, we highlighted two key issues that are confronting HRM and societies—geopolitical tensions and employee mental health. While the former offers a macro-level context for developing organizational capabilities for managing people, the latter is to some extent affected by the former in a setting of increasing polarization of society and workplaces. The topical areas that we have selected for discussion in this editorial have strong practical implications in that they accentuate tensions for HRM and challenges for organizational leaders and HR practitioners. The polarization of societies, in part driven by diverse and even conflicting values and ideologies, creates new challenges and calls for new leadership skills and HR competencies to best support their organization and manage the workforce effectively (Javidan et al., Citation2023; Minson & Gino, Citation2022). How can HR practitioners help design HRM policies and practices to accommodate workplace diversity and inclusion on the one hand while conforming to the country’s espoused ethics and values on the other? Such tensions are likely to be amplified for MNEs, bringing extraordinary challenges to organizational leaders and HR practitioners.

To conclude, the role of HR practitioners is increasingly demanding. They need to engage in continuous self-development to adapt to the changing landscape of people management as a result of geopolitical tensions, polarization of workplaces and society, increased use of digital technology, post-COVID pandemic economic downturn, and increase in employee mental ill health and absences. We encourage HR scholars to conduct phenomenon-based research to help inform policy decisions and practices to generate societal impact. We further encourage HR scholars to incorporate their research into management education to better prepare the future generation of organizational leaders and HR practitioners. Embarking on these tasks will help towards achieving the Sustainable Development Goals.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

There is no data associated with this paper.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Armstrong, P. (2023, July 26). How can HR encourage ‘good stress’ and limit ‘bad stress’? https://www.hrmonline.com.au/mental-health/how-can-hr-encourage-good-stress/.

- Bader, B., Schuster, T., & Dickmann, M. (Eds.). (2020). Danger and risk as challenges for HRM: Managing people in hostile environments. Routledge.

- Briscoe, J. P., & Hall, D. T. (2006). The interplay of boundaryless and protean careers: Combinations and implications. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 69(1), 4–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2005.09.002

- Caligiuri, P., De Cieri, H., Minbaeva, D., Verbeke, A., & Zimmermann, A. (2020). International HRM insights for navigating the COVID-19 pandemic: Implications for future research and practice. Journal of International Business Studies, 51(5), 697–713. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-020-00335-9

- Cavanagh, J., Bartram, T., Meacham, H., Bigby, C., Oakman, J., & Fossey, E. (2017). Supporting workers with disabilities: A scoping review of the role of human resource management in contemporary organisations. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 55(1), 6–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7941.12111

- Collings, D. G., & Mellahi, K. (2009). Strategic talent management: A review and research agenda. Human Resource Management Review, 19(4), 304–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2009.04.001

- Cooke, F. L. (2022). Talent management in Africa: Challenges, Opportunities and Prospects. In I. Tarique (Ed.), The Routledge companion to talent management (pp. 153–163). Routledge.

- Cooke, F. L., Dickmann, M., & Parry, E. (2023). Building a sustainable ecosystem of human resource management research: Reflections and suggestions. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 34(3), 459–477. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2023.2165011

- Cooke, F. L., & Xu, W. Q. (2023). Extending the research frontiers of employee mental health through contextualisation: China as an example with implications for human resource management research and practice. Personnel Review. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-05-2023-0377

- Cui, V., Vertinsky, I., Wang, Y., & Zhou, D. (2023). Decoupling in international business: The ‘new’ vulnerability of globalization and MNEs’ response strategies. Journal of International Business Studies, 54(8), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-023-00602-5

- Dunning, J. H., & Lundan, S. M. (2010). The institutional origins of dynamic capabilities in multinational enterprises. Industrial and Corporate Change, 19(4), 1225−1246.

- De Vos, A., Van der Heijden, B. I., & Akkermans, J. (2020). Sustainable careers: Towards a conceptual model. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 117, 103196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.06.011

- Edelman Trust Barometer Global Report. (2023). https://www.edelman.com/sites/g/files/aatuss191/files/2023-03/2023%20Edelman%20Trust%20Barometer%20Global%20Report%20FINAL.pdf.

- Elraz, H. (2018). Identity, mental health and work: How employees with mental health conditions recount stigma and the pejorative discourse of mental illness. Human Relations, 71(5), 722–741. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726717716752

- Farndale, E., Thite, M., Budhwar, P., & Kwon, B. (2021). Deglobalization and talent sourcing: Cross-national evidence from high-tech firms. Human Resource Management, 60(2), 259–272. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.22038

- Festing, M., & Eidems, J. (2011). A process perspective on transnational HRM systems — A dynamic capability based analysis. Human Resource Management Review, 21(3), 162−173.

- Follmer, K. B., & Jones, K. S. (2018). Mental illness in the workplace: An interdisciplinary review and organizational research agenda. Journal of Management, 44(1), 325–351. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206317741194

- Forsgren, M., & Yamin, M. (2023). The MNE as the “crown of creation”?: A commentary on mainstream theories of multinational enterprises. Critical Perspectives on International Business, 19(4), 489–510. https://doi.org/10.1108/cpoib-05-2022-0048

- Gaur, A., Settles, A., & Väätänen, J. (2023). Do economic sanctions work? Evidence from the Russia-Ukraine conflict. Journal of Management Studies, 60(6), 1391–1414. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12933

- Harsch, K., & Festing, M. (2020). Dynamic talent management capabilities and organizational agility—A qualitative exploration. Human Resource Management, 59(1), 43–61. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21972

- Hastuti, R., & Timming, A. R. (2021). An inter–disciplinary review of the literature on mental illness disclosure in the workplace: Implications for human resource management. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 32(15), 3302–3338. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2021.1875494

- Hastuti, R., & Timming, A. R. (2023). Can HRM predict mental health crises? Using HR analytics to unpack the link between employment and suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Personnel Review, 52(6), 1728–1746. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-05-2021-0343

- Hennekam, S., Follmer, K., & Beatty, J. (2021). The paradox of mental illness and employment: A person-job fit lens. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 32(15), 3244–3271. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2020.1867618

- Javidan, M., Cotton, R., Kar, A., Kumar, M. S., & Dorfman, P. W. (2023). A new leadership challenge: Navigating political polarization in organizational teams. Business Horizons, 66(6), 729–740. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2023.03.001

- Jooss, S., Collings, D. G., McMackin, J., & Dickmann, M. (2024). A skills-matching perspective on talent management: Developing strategic agility. Human Resource Management, 63(1), 141–157. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.22192

- Kaur, V. (2022). Multinational orchestration: A meta-theoretical approach toward competitive advantage. Critical Perspectives on International Business, 19(2), 206–233. https://doi.org/10.1108/cpoib-11-2021-0090

- Kokabisaghi, F., Miller, A. C., Bashar, F. R., Salesi, M., Zarchi, A. A. K., Keramatfar, A., Pourhoseingholi, M. A., Amini, H., & Vahedian-Azimi, A. (2019). Impact of United States political sanctions on international collaborations and research in Iran. BMJ Global Health, 4(5), e001692. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001692

- Malik, S., Doocy, S., & Burnham, G. (2014). Future plans of Iraqi physicians in Jordan: Predictors of migration. International Migration, 52(4), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12059

- Mayne, M. (2023, September 29). Identifying the causes of workload stress and tackling different management styles – what we learned from the CIPD Health and Wellbeing at Work report. People Management. https://www.peoplemanagement.co.uk/article/1839181/identifying-causes-workload-stress-tackling-different-management-styles-%e2%80%93-learned-cipd-health-wellbeing-work-report?bulletin=pm-daily&utm_source=mc&utm_medium=email&utm_content=PM+Daily+29.09.23.https%3a//www.peoplemanagement.co.uk/article/1839181/identifying-causes-workload-stress-tackling-poor-management-styles-%25E2%2580%2593-learned-cipd-health-wellbeing-work-report%3fbulletin%3dpm-daily&utm_campaign=7295441&utm_term=1099866

- Melin, M. M., Sosa, S., Velez-Calle, A., & Montiel, I. (2023). War and international business: Insights from Political Science. AIB Insights, 23(1). https://doi.org/10.46697/001c.68323

- Mello, R., Suutari, V., & Dickmann, M. (2023). Taking stock of expatriates’ career success after international assignments: A review and future research agenda. Human Resource Management Review, 33(1), 100913. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2022.100913

- Minson, J. A., & Gino, F. (2022). Managing a polarized workforce. Harvard Business Review, 100(2), 63–71.

- Newnham, R. E. (2015). Georgia on my mind? Russian sanctions and the end of the ‘Rose Revolution’. Journal of Eurasian Studies, 6(2), 161–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euras.2015.03.008

- Özdamar, Ö., & Shahin, E. (2021). Consequences of economic sanctions: The state of the art and paths forward. International Studies Review, 23(4), 1646–1671. https://doi.org/10.1093/isr/viab029

- Pitelis, C. N., & Teece, D. J. (2010). Cross-border market co-creation, dynamic capabilities and the entrepreneurial theory of the multinational enterprise. Industrial and Corporate Change, 19(4), 1247−1270.

- Pitelis, C. N., Teece, D. J., & Yang, H. (2023). Dynamic capabilities and MNE global strategy: A systematic literature review-based novel conceptual framework. Journal of Management Studies, https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.13021

- Raupp, M. (2023). “Am I welcome in this country?”: Expatriation to the UK in times of BREXIT and its “hostile environment policy. In M. Andresen, S. Anger, A. Al Ariss, C. Barzantny, H. Brücker, M. Dickmann, L. Mäkelä, S. L. Muhr, T. Saalfeld, V. Suutari, & M. Zølner (Eds.), Wanderlust to Wonderland?. University of Bamberg.

- Riches, C. (2023, 11 August). How should HR respond to an increasingly polarised workforce? https://www.hrmonline.com.au/section/featured/how-should-hr-respond-to-an-increasingly-polarised-workforce/.

- Ronaghy, H. A., & Shajari, A. (2013). The Islamic Revolution of Iran and migration of physicians to the United States. Archives of Iranian Medicine, 16(10), 590–593.

- Selmer, J., Dickmann, M., Froese, F. J., Lauring, J., Reiche, B. S., & Shaffer, M. (2021). The potential of virtual global mobility: Implications for practice and future research. Journal of Global Mobility: The Home of Expatriate Management Research, 10(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1108/JGM-07-2021-0074

- Steinberg, D. I. (2010). The United States and Myanmar: A ‘boutique issue’? International Affairs, 86(1), 175–194. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2346.2010.00874.x

- Suter, J., Irvine, A., & Howorth, C. (2022). Juggling on a tightrope: Experiences of small and micro business managers responding to employees with mental health difficulties. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 41(1), 3–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/02662426221084252

- Tasavori, M., Eftekhar, N., Mohammadi Elyasi, G., & Zaefarian, R. (2021). Human resource capabilities in uncertain environments. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 32(17), 3721–3747. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2020.1845776

- Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 18, 509−533.

- Teece, D. J. (2014). A dynamic capabilities-based entrepreneurial theory of the multinational enterprise. Journal of International Business Studies, 45, 8−37.

- United Nations (UN). (n.p.). Sustainable development. https://sdgs.un.org/goals.

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2022). Mental health at work. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-at-work.

- Zahra, S. A., Petricevic, O., & Luo, Y. (2022). Toward an action-based view of dynamic capabilities for international business. Journal of International Business Studies, 53(4), 583–600. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-021-00487-2