ABSTRACT

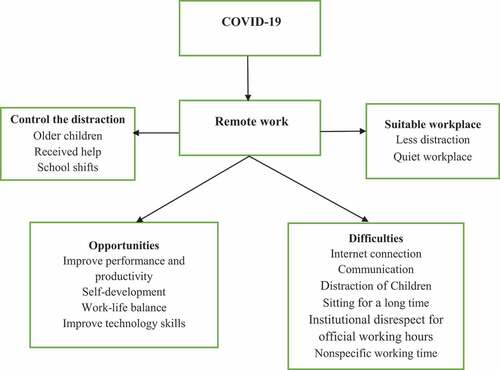

This study explores the perspectives of employed married women in Saudi Arabia and the impact of changing workplace patterns caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. A qualitative approach draws on the findings from in-depth semi-structured interviews with married Saudi working women in the public education sector. The key findings are identified through a thematic analysis. First, remote work is considered to provide a suitable and quiet workplace. Second, the challenges include weak internet connections (major factor), followed by communication, sitting for long periods, institutional disrespect for official working hours and non-specific working hours (minor factors). A specific difficulty was the distraction of children, but this was considered manageable. Third, working remotely gives Saudi married working women opportunities to increase their performance and productivity, develop themselves, create work-life balance and improve their technology skills. Finally, in the education sector, a blended workplace is a suitable pattern that can be implemented effectively. The study is exploratory with a small sample size, so the findings cannot be generalized. However, it generates new insights into gender stereotypes regarding the difficulties and opportunities of the changing workplace patterns caused by COVID-19, through the lens of Saudi married working women.

Introduction

Previous global crises have affected the economies, health services, and work environments of individual countries (Ud Din, Cheng, Nazneen, Hongyan, & Imran, Citation2020). The COVID-19 pandemic has caused a global economic crisis and affected health, social norms, and education (Galasso, Citation2020; Queiroz, Ivanov, Dolgui, & Wamba, Citation2020; Ud Din et al., Citation2020). To curb this disease, most countries imposed lockdowns and quarantines. Many scholars have explored the impact of COVID-19 on the workforce, workplace, careers (Al-Youbi, Al-Hayani, Rizwan, &F Choudhry, Citation2020; Del Boca, Oggero, Profeta, & Rossi, Citation2020; Hite & McDonald, Citation2020), and gender inequality (Galasso, Citation2020). Alon, Doepke, Olmstead-Rumsey, and Tertilt (Citation2020) believe that COVID-19 has had a stronger negative effect on vulnerable and minority groups, such as women. Due to changing workplace patterns in response to the pandemic, employed women face new challenges in managing their life responsibilities and work duties (Del Boca et al., Citation2020).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, some research has paid attention to the impact of remote working on women’s work in the global education sector (Del Boca et al., Citation2020; Hite & McDonald, Citation2020; Kaushik & Guleria, Citation2020; Ud Din et al., Citation2020), but there is a scarcity of studies that have addressed this issue in the Arab region, specifically in Saudi Arabia.

To fill this gap, this study explores the impact of changing workplace patterns caused by the COVID-19 pandemic on married Saudi working women. Specifically, the research questions focus on the individual viewpoints of women regarding their experience of changing workplace patterns, the difficulties and opportunities associated with working remotely, and preferences regarding future conditions. This study contributes to the literature on women’s work during the pandemic and speculates on how these ideas could be applied post pandemic, specifically in a normative country such as Saudi Arabia, and offers several practical recommendations and future research directions.

Literature review

Changing workplace patterns during the COVID-19 crisis

Changes in the work environment have arisen as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic (Hite & McDonald, Citation2020), which necessitated remote working (Hite & McDonald, Citation2020; Kaushik & Guleria, Citation2020) and created both obstacles and opportunities (Alon et al., Citation2020; Al-Youbi et al., Citation2020; Hite & McDonald, Citation2020). The trend of working daily from a home environment increased (Felstead & Henseke, Citation2017), particularly in the initial period of COVID-19 (Alon et al., Citation2020; Bick, Blandin, & Mertens, Citation2020). Olson (Citation1989) explained that working remotely refers to employees performing their work outside the normal organizational boundaries of space and time. According to Cserháti (Citation2020) and Olson (Citation1989), virtual work is suitable for many types of jobs, but not all.

Furthermore, Kaushik and Guleria (Citation2020) have shown that working remotely during COVID-19 has been a positive change for many employees, enabling them to keep up their productivity and performance while maintaining a work-life balance. Cserháti (Citation2020) and Al-Shathry (Citation2012) noted that remote work results in increased performance and productivity in employees because there are often fewer distractions, a quieter work environment, and less time spent commuting. Bloom, Liang, Roberts, and Ying (Citation2015) and Wheatley (Citation2012) demonstrated that performance, work effort, and job satisfaction were significantly increased for a group of homeworkers compared to a workplace-bound group. Similarly, Kelliher and Anderson (Citation2010) noted that employees often worked harder or longer when performing tasks remotely. Additionally, Olson (Citation1989) found that virtual work provided a quiet work environment, which improved employees’ productivity and motivation. Kelliher and Anderson (Citation2010) determined that remote work provided less workplace distraction, although working from home could also produce different distractions. Nevertheless, Al-Youbi et al. (Citation2020) commented that remote work creates a significant imbalance between employees’ professional work and personal lives, which could result in poor performance. Kaushik and Guleria (Citation2020) and Kelliher and Anderson (Citation2010) concluded that remote working requires dedication and commitment for employees to perform well and exercise high levels of effort at work.

While virtual work can provide individuals with more flexibility to manage their daily work duties and life patterns, it can also increase employees’ hours of work, as they are available to work at any time (Baruch & Nicholson, Citation1997; Kelliher & Anderson, Citation2010; Olson, Citation1989). Indeed, remote work requires more intensive and extensive work effort than the traditional workplace (Felstead & Henseke, Citation2017). In contrast, Kelliher and Anderson (Citation2010) found that the workload of a remote worker is maintained regardless of whether employees work full-time or reduce their hours. Remote work also saves employees’ commuting time and increases the time available to them for both work and family (Kaushik & Guleria, Citation2020; Wheatley, Citation2012).

Women’s work in the Saudi Arabian context

Generally, women face several obstacles and interruptions in their work, mostly related to gender-stereotyped divisions of labour (Ginige, Amaratunga, & Haigh, Citation2007; Schein, Citation2007). Women’s work interruptions differ according to country and wider intersectional factors (Al-Asfour, Tlaiss, Khan, & Rajasekar, Citation2017; Ud Din, Cheng, & Nazneen, Citation2018). According to Ud Din et al. (Citation2020), women’s career period can be divided into three typical stages, each of which is characterized with certain interruptions. In the early work stage, motherhood, marital status, and other intersectional factors affect women’s careers. In the mid-level work stage, marital status, childbirth, and childcare are factors of career interruption. In the late-level work stage, women often prefer flexible jobs or a career break to take care of a partner and grandchildren. Therefore, women’s careers are often interrupted, which limits their opportunities; these limitations often stem from cultural acceptance and beliefs about women’s role in society (Al-Asfour et al., Citation2017; Ginige et al., Citation2007). Gender stereotyping is connected to cultural beliefs that reflect the differences between the roles of men and women (Best, Citation2004). According to Heilman (Citation2012), a gender stereotype is an overgeneralized belief about the attribution and normative expectation of individual group members, which negatively affects women’s work. In a society characterized by conservative gender roles, most of the burden of housework and childcare falls on women (Del Boca et al., Citation2020). Because of these societal gender roles in such a society, women face difficulties maintaining a balance between the workplace and family responsibilities, which reduces their ability to compete and creates disadvantages in their career (Kaushik & Guleria, Citation2020; Mavin, Citation2001; Probert, Citation2005). In response to gender roles, other factors such as gender inequality, social structure and cultural norms negatively affect women’s capacity to work (Ud Din et al., Citation2020).

In a male-dominated society such as those found in the Arab region, women face difficulties in their working lives because of traditional values and gender stereotypes (Al-Asfour et al., Citation2017; Omair, Citation2008). Bahudhailah (Citation2019) explains that in Arabian culture, women primarily take care of children and may leave their job because of their family. Similarly, in a highly conservative society such as Saudi Arabia, women face obstacles in employment and the workplace due to social norms and gender stereotypes (Al Alhareth, Al Alhareth, & Al Dighrir, Citation2015; Al-Asfour et al., Citation2017; Alfarran, Pyke, & Stanton, Citation2018). According to Al-Asfour et al. (Citation2017), since widespread gender stereotypes predominate in Saudi society, women’s roles are seen as revolving around the household, as mothers and wives. Alfarran et al. (Citation2018) concurred and asserted that gender stereotypes affect employed Saudi women. Bahudhailah (Citation2019) suggested a flexible work environment for Saudi women could be potentially beneficial.

Scholars such as Olson (Citation1983), Cserháti (Citation2020), Kaushik and Guleria (Citation2020) and Alon et al. (Citation2020) suggest that working remotely from home is an opportunity for women with childcare responsibilities to manage the dual responsibilities of home and work and might be the best employment option. In contrast, Del Boca et al. (Citation2020) argue that in the case of working from home, a woman’s daily burden, resulting from remote working in addition to housework, is increased due to her gender-stereotyped role. Imposed quarantine measures during COVID-19, when family members were required to stay at home, exposed employed women to increased pressure from both work and family duties (Del Boca et al., Citation2020). In this case, women generally ended up having a higher overall workload, and their professional tasks faced more interruptions than usual (Kaushik & Guleria, Citation2020). According to Power (Citation2020), COVID-19 has resulted in a dramatic increase in women’s responsibilities. In conservative societies, women’s work is likely to be interrupted, although this may not be the case among couples who share their duties more equally (Ud Din et al., Citation2018). In Saudi society, family responsibilities remain largely ‘women’s work’ (Al-Asfour et al., Citation2017; Alfarran, Citation2016). Al-Shathry (Citation2012) and Alfarran (Citation2016) consider working remotely as a convenient response to Saudi women’s roles within the family. Olson (Citation1989) stated that remote work provides employees with flexibility in work and life. Flexibility of working hours is associated with a more positive experience for employees (Al-Shathry, Citation2012).

Research methodology

This study was exploratory; a qualitative approach was employed to investigate the perspective of the individuals experiencing the phenomenon of working at home (Veal, Citation2005). Individual face-to-face and telephone interviews were conducted to gain in-depth information (Creswell, Citation2013; Veal, Citation2005), and open-ended questions were used to elicit the maximum flow of information (Flick, Citation2009). Since all participants were native Arabic speakers, the interviews were conducted in Arabic. The main factor that enhanced the data collection was that the interviews were performed by an Arabic-speaking Saudi woman. This improved the understanding of the interviewees’ answers, since it increased the engagement of female participants and ensured privacy for female participants to safely share their perspectives.

Individual, semi-structured, face-to-face interviews were conducted with two groups of married Saudi women working in the public education sector, including schools and universities, regarding their experience of changing workplace patterns in responses to COVID-19. The education sector was selected as it is considered one of the sectors most affected by COVID-19 and transformed from a traditional to an online workplace (Al-Youbi et al., Citation2020). A sample of 12 married Saudi working women was selected and interviewed for approximately 45 minutes each. The sample represented both different job positions and areas, namely universities and schools; six married working women from each area were chosen for the study.

Personal networks were used to select women from each area for the initial interviews, and other participants were sourced for further contacts through a snowball sampling approach (Bryman, Citation2012). Interviews were stopped when saturation was reached and no new information was being generated (Patton, Citation2002). All participants were from the educational sector of [BLINDED] city, in Western Saudi Arabia. Open-ended inductive (bottom-up) reasoning was adopted to identify the significant themes arising from the interviews (Bryman, Citation2012; Kvale, Citation1996; Veal, Citation2005). Thematic analysis was applied to the summaries and data coded for further analysis and interpretation (Creswell, Citation2013). Data labelling was applied to transcripts to ensure the anonymity of the participants (Veal, Citation2005). All study participants provided informed consent, and the study design was approved by the appropriate ethics review board.

Findings

This study illuminates the perspectives of married Saudi working women to explore the impact of changing workplace patterns caused by COVID-19. The demographic characteristics of all participants are presented in .

Table 1. The characteristics of the [BLINDED] Taif university participants.

Table 2. The characteristics of participants from the schools.

shows the codes used for the participants from [BLINDED] Taif University and presents their personal and professional demographics.

The table shows that the education levels of the participants differed, with two participants holding managerial positions, and their experience ranged from 3 to 12 years. The weekly working hours of participants also varied and depended on their education level and occupation. Regarding their personal life, participants had between one and four children, and most of the children were younger than 12 years old (elementary school or nursery/infant). Half of the participants had household help, and half of them worked in a different city from where their family lived.

. shows the codes used for the participants’ who worked in the schools and presents their personal and professional demographics.

The education level of all these participants was a bachelor’s degree, with five participants held managerial positions, and their experience ranged from 12–21 years. Participants’ workdays lasted 7 hours (7 am to 2 pm). Regarding their personal lives, participants had between two and six children, and most of whom were either 7–12 years old (elementary school) or over 18 years old (university or work). More than half of the participants had household help, and all of them worked in the city where their family lived.

The themes identified in this study include the following: women’s experience of changing workplace patterns, the difficulties of dealing with remote work, the opportunities related to remote work and their preferences regarding future workplaces.

Women’s experience of remote work

Before COVID-19, all interviewees worked in traditional workplaces, and their organizations did not facilitate working from home. Thus, none of the participants had previous experience of working in places other than a formal workplace. However, during the COVID-19 pandemic, all the organizations concerned ‘locked down’, and work was run remotely from employees’ homes. None of the interviewees had returned to their traditional workplace during the quarantine. Therefore, all interviewees had experience of remote work during the pandemic.

When the government approved the return to the workplace, all four participants with managerial positions in the schools returned to working from their offices. In contrast, at the university, blended working arrangements were permitted for management staff, which was noted by two interviewees with managerial positions. A university participant stated that:

… before COVID-19, the dean of the department rejected the idea of doing one day remotely. After the safe return, he accepted that … now, I just commute to my workplace four days a week (U4).

However, all participants who did not have managerial positions from both organizations blended working from home and from the office. From the schools, two interviewees (E4, E6) stated that they had been commuting to their traditional workplace once a week. One participant said:

… according to the instruction of the Ministry of Education, we just had to be present at school and run our class online for one day a week (E4).

From the university, four interviewees who did not hold managerial positions had physically been to the university in the first week of each semester for academic advising only. Due to specific safety precautions, the head of each department created a schedule for attendance (a day and time for each member). Thus, faculty members were required to attend only a few days of the week for academic advising and only for a few hours daily.

Most of the participants (11 out of 12) were able to manage distractions while working at home and considered it a suitable and quiet environment. Half of the interviewees, who had older children, informed their family about their working schedule. A participant said:

… at the beginning of the shift to working remotely, I held a meeting with my family to make a daily routine … we set times for work, school, and meals (E2).

Other participants (3 out of 12), who had young children, received help from either a husband or housekeeper. A participant explained:

… my husband and I are both teachers and our children are in elementary school; thus, my husband looks after the kids during my shift in the morning, and I do that for him during the afternoon shift (E6).

A small proportion of participants (2 out of 12), who had young children, noted that school shifts helped them control distractions. Participants (U4, E4) explained that they usually finished their work in the morning while their children were sleeping, as their school shift was in the afternoon. Only one participant from the university (U1) noted ‘I can’t control my family’s distraction’. However, all the interviewees agreed that remote work was a successful experiment and provided a suitable working pattern and a quiet environment, regardless of any difficulties they faced.

In summary, before COVID-19, the organizations in which the participants worked followed the traditional in-person work model; after COVID-19, they required employees to adopt remote work. After the government announced a safe return to the workplace for all sectors, all the participants with managerial positions in the schools returned to working from their offices every day, while all university participants with managerial positions followed a blended work model, as did non-managerial university and schools participants. It is worth mentioning that the experience of remote work could change the mindset of the university’s stakeholders. Moreover, while the Minister of Education required that school staff without managerial positions attended their workplace once a week, it did not impose this requirement on the universities.

The difficulties of dealing with remote work

All the interviewees cited their internet connection as the main difficulty of working remotely, which was problematic for them and their students. Other difficulties mentioned were considered minor. Three participants from the university, who had young children, noted the distraction of children (U1, U2, U4). Two interviewees noted communication occurring with staff during and outside of working hours (E1, E2), difficulty communicating with students (U6, E5), and sitting for long periods in front of the computer (E1, E2) as minor difficulties.

Interestingly, two participants cited a lack of respect from either staff and/or family regarding respect of their working time. A participant (E2) noted that ‘some staff thought that they were on vacation’, and (U6) added, ‘my extended family thought that I was free at all times’. Only university participants with managerial positions noted non-specific working hours. Two participants (U3, U4) stated that they had to be available at any time to do their work. Finally, one participant (E4) complained that ‘students are using their phones to attend classes, which negatively impacts their academic achievements’.

Opportunities related to remote work

Four aspects of working remotely were considered by the interviewees as opportunities: performance and productivity, self-development, work-life balance, and improved technology skills.

All participants agreed that working remotely increased their performance and productivity for the following reasons: completing work was easy; there were fewer distractions, less workload and the time usually spent commuting was saved. Half of the participants (6 out of 12) noted that it was easy to conduct work from home. A school’s principal (E2) explained that ‘online work makes supervision of teachers’ workflow and students participation in classes easier and faster’. From the university group, a participant (U5) added that ‘it is easier to deal with late lectures later in the day, such as from 3 pm to 5 pm’. Less than half the participants (5 out of 12) mentioned implementing new teaching tools in their classes and lectures. Interviewees (U2, E6) elaborated on methods such as flipped classroom activities, reading and summarizing, using PowerPoint slides, assignments, quizzes, and open book exams. Four participants (U1, U5, E1, E6) noted that working from home was less distracting and an ideal, quiet environment which helped them to deliver subject content smoothly. Another four participants (U5, U6, E5, E6) stated that the workload at home was less than what they had in the traditional workplace. Participant E6 added that:

I have to do some administrative work in addition to teaching in the traditional workplace; thus, working remotely has increased my concentration on teaching and delivering the information only (E6).

Four more interviewees (U1, U2, U3, E5) noted that working from home saved time previously spent commuting to or sitting around in the workplace. A participant (U1) noted that ‘commuting to work, office working hours and free time between lectures are time-consuming’.

Self-development was the second beneficial aspect of working remotely as participants found it to be an opportunity for improving themselves. Half the participants stated that they had attended training courses in different disciplines. Moreover, the university participants (U2, U5, U6) had opportunities to communicate with a range of international and local universities to pursue their postgraduate degrees (Master, PhD). A participant from the school (E1) even wrote a book.

The next aspect of working remotely that participants were satisfied with was work-life balance. Four participants (U2, U3, U5, U6) mentioned that working remotely helped them create a balance between their work and personal life. A participant said:

… working remotely gave me a chance to stay with my family in the same city, so I am happy regardless of the workload (U2).

Another participant stated:

… while I have to work from 9 am to 5 pm on some days, I still have free time I can spend with my family (U5).

Another participant added:

… finally, I can cook for my family and look after my son … remote work makes me feel like I am in heaven (U6).

Interestingly, only participants from the university noticed that remote work helped them find more equilibrium between their work and personal life. This could be explained as follows. First, each university staff member’s schedule has different weekly working hours depending on their educational level and occupation. Thus, before remote work was possible, university staff frequently found their schedules were incompatible with family responsibilities. Second, university participants in this study were mothers of young children and infants and had no household help, so working from home gave them more time for home-related tasks. Finally, some of the participants lived and worked in different cities, which increased their work-life balance challenges.

Finally, participants were satisfied with opportunities to improve their technology skills while working remotely. Three participants (U4, E2, E3) mentioned that the technology skills of both educators and students had improved.

Future workplace preferences

Most of the participants (8 out of 12) preferred a blended workplace; three days’ work in the traditional workplace and two days at home. Participants mentioned several reasons for these choices. All six participants with managerial positions from either the university or schools noted that it was sufficient to commute to the workplace a few days a week to complete administrative work. University participants (U1, U3, U4, U5) believed that some subjects could be delivered online but that others required face-to-face interaction with students. It is worth noting that university staff can choose the subjects they want to teach each semester. Other participants (U5, E2, E5) mentioned the need to commute to the traditional workplace in order to communicate directly with students. One participant (U1) noted that this saved time and effort.

Only two participants (teachers) preferred to work mainly from their traditional workplace. As one participant explained:

I am teaching information technology (IT), this subject has a large practical component and needs to be delivered in a computer lab (E4).

Another participant (E6) added:

I am teaching physics, so I have to be with students to ensure that the contents are delivered properly.

Two participants from the university (U2, U6) preferred to work mainly from home to create a better life-work balance.

Discussion

This study explored the impact of changing workplace patterns caused by COVID-19 on married Saudi working women. The research questions focussed on four features: women’s experiences of changing workplace patterns, the opportunities of working remotely, the challenges of working remotely and the participants’ preferences for future working conditions. This paper identified the following key findings:

The first finding concerns the working pattern of the workplace. The participants considered remote work to be that provided a quiet workplace. Further, participants noted that they could managed home distractions while working remotely, regardless of their children’s age. This finding concurs with Kaushik and Guleria (Citation2020)and Alon et al. (Citation2020) who asserted that working remotely from home might be the best employment option for married women with childcare responsibilities. Del Boca et al. (Citation2020) found that due to gender-stereotypical division of labour, working from home increased women’s responsibilities. However, in a conservative society such as Saudi Arabia, working remotely may be a convenient solution for women, given the predominant socio-cultural conditions regarding gender and working roles (Al-Shathry, Citation2012; Ginige et al., Citation2007; Schein, Citation2007). While Alfarran et al. (Citation2018) found that Saudi women had no hesitation regarding working in the public sector, particularly the education sector, the majority of participants preferred to work from home. Thus, it can be argued that while working remotely increases a women’s burden, these married Saudi working women considered it a suitable working arrangement given their roles and family responsibilities.

Second, the participants faced one major external and several minor internal difficulties while working remotely. The major external difficulty experienced while working from home was the weakness of internet connections. Indeed, poor internet connection causes work interruptions and wastes time (Kaushik & Guleria, Citation2020). The minor external factors of remote working were communication with colleagues and students, sitting for long periods in front of the computer, institutional disrespect for official working hours and non-specific working times. Thus, it can be argued that employees working remotely should learn new skills such as those meant to improve communication (Kaushik & Guleria, Citation2020), and maintain their commitment to official working hours (Kaushik & Guleria, Citation2020; Kelliher & Anderson, Citation2010). The finding regarding non-specific working hours is supported by scholars such as Kelliher and Anderson (Citation2010) and Baruch and Nicholson (Citation1997) who argued that remote work increased daily working hours. The effect of remote working on employees’ health due to sitting for long periods in front of a computer has not been raised in previous research. It can be argued that remote workers should implement break times during official working hours for movement and comfort. Finally, a particular internal difficulty faced was the distraction of children in the home environment. However, this was considered a minor, manageable factor by the participants. It could be argued that, due to gender stereotypes in the Saudi context, married working women who received help from a husband or housekeeper preferred to work remotely, regardless of the age of their children. This finding is supported by Bahudhailah (Citation2019), Alfarran et al. (Citation2018), Al-Asfour et al. (Citation2017), and Al Alhareth et al. (Citation2015) who argued that gender stereotypes affect employed Saudi women and suggested working remotely as an employment option. The findings of the current study suggest that either employed women have limited awareness of the difficulties of working remotely or that they prefer to do work remotely regardless of the difficulties.

The third finding indicates that working remotely gives married Saudi working women opportunities to increase their performance and productivity, develop themselves, create better work-life balance, and improve their technology skills. First, remote work increased the performance and productivity of employed women for the following reasons: the women in this study found it easier to conduct their work, experienced fewer distractions, had a reduced workload, and saved time previously spent commuting and sitting around in their workplace between tasks. This finding concurs with Kaushik and Guleria (Citation2020), Cserháti (Citation2020), Al-Shathry (Citation2012) and Olson (Citation1989) who argued that working remotely can increase employees’ performance and productivity due to there being fewer distractions, a quieter work environment, a better life-work balance and saving commuting time. However, this finding contrasts with Del Boca et al. (Citation2020) who found that women’s daily load, resulting from remote work and housework, is increased due to persistent gender roles. It also contrasts with Felstead and Henseke (Citation2017), who determined that virtual work requires more intensive and extensive effort than is required in the traditional workplace. It can be argued that due to cultural acceptance and traditional gender roles in society, women’s performance and competitiveness are low (Kaushik & Guleria, Citation2020; Mavin, Citation2001; Probert, Citation2005) and that they face obstacles in their work, such as interruptions and limited opportunities (Al-Asfour et al., Citation2017; Ginige et al., Citation2007), which hinders their career progression (Al-Asfour et al., Citation2017; Alfarran et al., Citation2018). In the situation of married Saudi employed women, remote working may provide a more suitable environment.

Moreover, regardless of whether women received help or managed their time, remote work gave these participants time to develop themselves. This study confirmed that working from home entails a reduced workload and saves time previously spent commuting or sitting idle in the workplace. In short, due to the reduced workload and time saved by working remotely, employees could utilize the saved time in self-development. Third, remote working enabled these participants to create a balance between work duties and family’s responsibilities. Indeed, working from home appeared to be an opportunity for employed women to manage the dual responsibilities of family and work (as also found by Cserháti, Citation2020; Kaushik & Guleria, Citation2020; Olson, Citation1983; Wheatley, Citation2012). However, this finding contrasts with Al-Youbi et al. (Citation2020) and Del Boca et al. (Citation2020) who found that remote working could cause an imbalance between personal lives and the professional tasks of employees due to gender stereotypes in a conservative society. Nevertheless, the married Saudi working women in this study found that remote work was a suitable alternative. Finally, a new finding here was that remote work improved the technology skills of the participants. This finding contrasts with Kaushik and Guleria (Citation2020) and Al-Shathry (Citation2012) who suggested that workers require updated technology skills in order to work remotely. The sudden situation of COVID-19, which necessitated working from home, encouraged employees to learn new technology skills to deliver their work.

Finally, in the education sector, the blended workplace was a pattern that suited married working women in Saudi Arabia and could be rolled out more generally in the future. For example, administrative work can often be done from home, and some curricula, such as theoretical content, can be delivered through online classes. This finding supports other research that has found virtual work to be suitable for many types of jobs (Cserháti, Citation2020; Olson, Citation1989) and recommends the implementation of remote working in the Saudi education sector, particularly universities (Al-Shathry, Citation2012). Al Alhareth et al. (Citation2015) recommended that the Saudi government should take steps to enable employed women to work remotely. However, it is worth pointing out that remote working can go beyond gender in that it has the potential to improve productivity and self-development, enhance work-life balance and improve technological skills for all workers.

Theoretical implications

This study enriches existing literature on gender stereotypes affecting married working women in Saudi Arabia and offers an in-depth investigation into the perspectives of married employed women regarding remote working. While there is a substantial body of literature on remote working (Alon et al., Citation2020; Al-Youbi et al., Citation2020; Cserháti, Citation2020; Felstead & Henseke, Citation2017; Hite & McDonald, Citation2020; Olson, Citation1989) and scant research exploring the gender issues concerning women’s work in the context of Saudi Arabia (Al-Asfour et al., Citation2017; Alfarran et al., Citation2018), there is no identified research exploring the perspectives of married Saudi working women regarding changing working patterns during COVID-19. These constraints have limited the scope of this research while increasing the significance of the findings, given that little comparable research has been undertaken in the past. The strength of this study has been to give voice to married Saudi working women, capturing their experience and exploring the difficulties and opportunities of remote working from their perspective. Moreover, this paper contributes to the theoretical perspectives of married working women in a context where culture has a strong influence on their work practices due to the dominant gender roles on one hand, and their experience of remote working on the other.

Furthermore, the findings have important implications for Saudi policymakers to help married working women overcome the challenges and obstacles to their work. There is a need to study the possibility of implementing remote working or blended workplace patterns in the education sector as well as more widely. In order to do so, attention needs to be paid to improving internet connectivity, offering virtual skills courses and enacting strict rules regarding official working hours. A female-friendly work environment is the key factor to facilitating women’s workforce participation in Saudi Arabia, and remote working offers once means of achieving this.

Study limitations and future research

Despite the contributions of this study, it has limitations that must be considered. First, there is scant research on the impact of workplace patterns on employed women in Saudi Arabia generally. These limitations create significant constraints on data collection, analysis, and dissemination of research findings. Second, the generalizability of the findings is limited, as the study is exploratory, with a small sample size from only one city. This means that the findings cannot be generalized to all women employed in Saudi Arabia or women from different educational backgrounds and with fewer resources (many of the participants had help at home). Additionally, no research was done on the experience of men working from home during the lockdown.

Suggestions for future research include cross-country studies in other Arab societies to address the impact of remote working on married working women. Future studies could also explore the impact of remote work on Saudi women’s participation rate, employment, career progress and retention in the private sector.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Abeer Kamel Saad Alfarran

Dr.Abeer Kamel Saad Alfarran an assistant professor and the Coordinator of Professional Development and Career Support Unit at the University of Taif. Dr. Alfarran teaches Human Resource Management, Leadership Management, International Business Management, Strategic Management, Operational Management, Hospital Management, Scientific Research Methods and Management Principles. Her research interests lie in the areas of Middle Eastern Women’s Issues, Race and Gender Studies, Cultural Studies and Social Inequalities. In addition, her work has been published in Arabic and English journals such as Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, ALMANARA for Research and Studies and Journal of Economic, Administrative and Legal Sciences.

References

- Al Alhareth, Y., Al Alhareth, Y., & Al Dighrir, I. (2015). Review of women and society in Saudi Arabia. American Journal of Educational Research, 3(2), 121–125.

- Al-Asfour, A., Tlaiss, H., Khan, S., & Rajasekar, J. (2017). Saudi women’s work challenges and barriers to career advancement. Career Development International, 22(2), 184–199.

- Al-Shathry, E. (2012). Remote work skills. International Journal of e-Education, e-Business, e-Management and e-Learning, 2(6), 546.

- Al-Youbi, A., Al-Hayani, A., Rizwan, A., & Choudhry, H. (2020). Implications of COVID-19 on the labor market of Saudi Arabia: The role of universities for a sustainable workforce. Sustainability, 12(7090), 1–13.

- Alfarran, A. (2016). Increasing women’s labour market participation in Saudi Arabia: the role of government employment policy and multinational corporations (Doctoral dissertation). Victoria University Theses and Dissertations Archive. Accessed 2 March 2021. https://vuir.vu.edu.au/31703/3/ALFARRANAbeer-thesis_nosignature.pdf

- Alfarran, A., Pyke, J., & Stanton, P. (2018). Institutional barriers to women’s employment in Saudi Arabia. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 37(7), 713–727.

- Alon, T., Doepke, M., Olmstead-Rumsey, J., & Tertilt, M. (2020). The impact of the coronavirus pandemic on gender equality. Covid Economics, 4. Accessed 21 January 2021. https://voxeu.org/article/impact-coronavirus-pandemic-gender-equality#:~:text=The%20lockdowns%20triggered%20by%20COVID,outsized%20impact%20on%20working%20mothers

- Bahudhailah, M., (2019). Exploring the barriers to work-life balance for women in Saudi Arabia (Master’s thesis). University of Hull eTheses Repository. Accessed 9 February 2021. https://hydra.hull.ac.uk/assets/hull:17573a/content

- Baruch, Y., & Nicholson, N. (1997). Home, sweet work: Requirements for effective home working. Journal of General Management, 23(2), 15–30.

- Best, D. L. (2004). Gender stereotypes. In C. R. Ember, and M. Ember (Eds.), Encyclopedia of sex and gender: Men and women in the world’s cultures (Vol. I) (pp. 11–27). New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers .

- Bick, A., Blandin, A., & Mertens, K. (2020). Work from home after the COVID-19 outbreak. Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. Accessed 19 January 2021. https://www.dallasfed.org/-/media/documents/research/papers/2020/wp2017r1.pdf

- Bloom, N., Liang, J., Roberts, J., & Ying, Z. J. (2015). Does working from home work? Evidence from a Chinese experiment. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 130(1), 165–218.

- Bryman, A. (2012). Social research methods, 4th ed. Oxford University Press, Oxford, England.

- Creswell, J. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Cserháti, I. (2020). “Business is unusual” – Remote work after COVID-19. Köz-gazdaság, 15(2), 38–53.

- Del Boca, D., Oggero, N., Profeta, P., & Rossi, M. (2020). Women’s work, housework and childcare, before and during Covid-19. CESifo Working Paper, No. 8403. Accessed 24 December 2020, Center for Economic Studies and Ifo Institute (CESifo), Munich. http://hdl.handle.net/10419/223475

- Felstead, A., & Henseke, G. (2017). Assessing the growth of remote working and its consequences for effort, well‐being and work‐life balance. New Technology, Work and Employment, 32(3), 195–212.

- Flick, U. (2009). An introduction to qualitative research. 4th ed., Sage Publications Ltd., London, Emgland.

- Galasso, V. (2020). Covid: Not a great equaliser. COVID Economics, 19, 241–255.

- Ginige, K., Amaratunga, R., & Haigh, R. (2007, September 12–13).Gender stereotypes: A barrier for career development of women in construction. 3rd Annual Built Environment Education Conference of the Centre for Education in the Built Environment. London, England, University of Westminster, Central London.

- Heilman, M. (2012). Gender stereotypes and workplace bias. Research in Organizational Behavior, 32, 13–135.

- Hite, L., & McDonald, K. (2020). Careers after COVID-19: Challenges and changes. Human Resource Development International, 23(4), 427–437.

- Kaushik, M., & Guleria, N. (2020). The impact of pandemic COVID −19 in workplace. European Journal of Business and Management, 12(15), 9–18.

- Kelliher, C., & Anderson, D. (2010). Doing more with less? Flexible working practices and the intensification of work. Human Relations, 63(1), 83–106.

- Kvale, S. (1996). Interviews: an introduction to qualitative research interviewing. Sage publications, Thousand Oaks, CA.

- Mavin, S. (2001). Women’s career in theory and practice: Time for change? Women in Management Review, 16(4), 183–192.

- Olson, H. (1983). Remote office work: Changing work patterns in space and time. Communications of the ACM, 26(3), 182–187.

- Olson, H. (1989). Remote office work: Changing work patterns in space and time. Communications of the ACM, 26(3), 182–187.

- Omair, K. (2008). Women in management in the Arab context. Education, Business and Society: Contemporary Middle Eastern Issues, 1(2), 107–123.

- Patton, M. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods, 3rd ed. Sage publications, Thousand Oaks, CA.

- Power, K. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic has increased the care burden of women and families. Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy, 16(1), 67–73.

- Probert, B. (2005). I just couldn’t fit it in: Gender and unequal outcomes in academic careers. Gender, Work and Organization, 12(1), 50–72.

- Queiroz, M., Ivanov, D., Dolgui, A., & Wamba, S. (2020). Impacts of epidemic outbreaks on supply chains: Mapping a research agenda amid the COVID-19 pandemic through a structured literature review. Annals of Operations Research, 1–38. doi:10.1007/s10479-020-03685-7

- Schein, E. (2007). Women in management: Reflections and projections. Women in Management Review, 22(1), 6–18.

- Ud Din, N., Cheng, X., & Nazneen, S. (2018). Women’s skills and career advancement: A review of gender (in) equality in an accounting workplace. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istrazivanja, 31(1), 1512–1525.

- Ud Din, Z., Cheng, X., Nazneen, S., Hongyan, S., & Imran, M. (2020). COVID-19 crisis shifts the career paradigm of women and maligns the labor market: A gender lens. Electronic Journal. Accessed 21 January 2021. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3589448

- Veal, A. (2005). Business research methods; a managerial approach (2nd ed.). Australia: Pearson Australian Group Pty Ltd, NSW.

- Wheatley, D. (2012). Good to be home? Time-use and satisfaction levels among home-based teleworkers. New Technology, Work and Employment, 27(3), 224–241.