ABSTRACT

Violence in post-conflict settings is often attributed to a post-war boom in organized crime, facilitated by the demobilization of armed groups and the persisting weakness of the state. The article argues that this is only one pathway of post-conflict violence. A second causal pathway emerges from the challenges that peace processes can constitute for entrenched local political orders. By fostering political inclusion, the implementation of peace agreements may threaten subnational political elites that have used the context of armed conflict to ally with armed non-state actors. Violence is then used as a means to preserve such de facto authoritarian local orders. We start from the assumption that these two explanations are not exclusive or competing, but grasp different causal processes that may well both be at work behind the assassination of social leaders (líderes sociales) in Colombia since the 2016 peace agreement with the FARC guerrilla. We argue that this specific type of targeted violence can, in fact, be attributed to different, locally specific configurations that resemble the two pathways. The article combines fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis with the case studies of the municipalities of Sardinata and Suárez to empirically establish and illustrate the two pathways.

1. Introduction

The promise of peace after the 2016 peace agreement between the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) has been marred by a wave of assassinations of representatives of local communities, indigenous, Afro-Colombian and peasant organizations as well as other social movement organizations.Footnote1 This targeted violence against social leaders (líderes sociales) provides a powerful reminder that the termination of an armed conflict does not necessarily mean the end of violence.Footnote2

To explain this wave of targeted assassinations in post-agreement Colombia, observers and scholars have mainly focused on the role of criminal actors and illicit economies. This explanation draws on the general observation that persisting violence in many post-conflict societies reflects a shift from armed conflict to post-war organized crime.Footnote3 More specifically, the increase in this type of targeted violence after 2016 is seen as a consequence of the dissolution of local configurations of rebel governance established by the FARC. The demobilization of the FARC and the failure of the state to fill the territorial power vacuum enabled other armed non-state actors (ANSAs) – which include other guerrillas, neo-paramilitaries, criminal groups, and several FARC dissident groups – to violently dispute the control of illicit markets.Footnote4 Social activists are assassinated because they stand in the way of ANSAs’ control over territories and corridors of strategic relevance for illicit economies.Footnote5

In contrast to this explanation, and in line with the focus of this special issue, other studies have highlighted a more explicitly ‘political’ pathway.Footnote6 These scholars argue that the 2016 peace agreement and its implementation challenged de facto authoritarian orders at the subnational level, which are sustained by alliances between local political elites, state institutions and ANSAs. In providing for (limited) socioeconomic and political reforms at the local level and by stimulating the mobilization of marginalized groups in the name of its promises, the peace accord has posed a fundamental threat to local elites who preside over exclusionary orders. In these places, formal democratic procedures are systematically subverted by informal, including violent, means. The assassination of social leaders reflects the violent response of local elites who see their power threatened by sociopolitical challenges ‘from below’ emerging in the wake of the peace process. ANSAs also play an important role in actually exercising violence, but they are seen as part of local power networks seeking to maintain de facto authoritarian orders.Footnote7

Building on this previous research, we start from the assumption that these two explanations are not exclusive or competing, but rather grasp different causal processes that may well both be at work in post-agreement Colombia. Given this country’s subnational variation, we expect that the configuration of factors that causes the targeted violence against social leaders varies across all municipalities. Generally speaking, post-conflict dynamics of violence are as complex and varying as are the civil war settings from which they emerge.Footnote8 As Kasfir et al. highlight, governance arrangements that develop during civil war are characterized by a multiplicity of armed actors, which play a variety of roles and have diverse relationships with civil society and state actors.Footnote9 In this sense, the two causal pathways of post-conflict violence can be understood as reflecting the legacies of different types of local governance arrangements before the demobilization of the FARC.

In focusing on the two pathways, we embrace the possibility of causal complexity behind the assassination of social leaders without sacrificing the goal of establishing some general patterns of post-conflict violence. We do so by, first, presenting the two theoretical explanations and situating the assumed causal processes in existing research. While, analytically, we neatly distinguish between what we call the ‘criminal’ and the ‘political’ pathway, it has to be emphasized that this distinction is problematic. Conceptually, as we explain in Section 3, the labels ‘criminal’ versus ‘political’ are not meant to suggest that the former pathway should be considered as ‘apolitical’ or the latter as not involving criminal activities. Empirically, as our case studies will show, these analytically distinct causal pathways can coexist and merge in individual local settings.

After our theoretical discussion, we conduct an empirical exploration using fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA). QCA is the most appropriate method for our purposes because it is explicitly based on the assumption of equifinality and, thus, well suited to identify multiple pathways that lead to one and the same outcome. We specifically chose fsQCA since our analysis contains conditions that cannot plausibly be measured in a dichotomous way. Focusing on 41 municipalities in regions with a high incidence of assassinations of social leaders that exhibit varying levels of lethal violence against social leaders, we identify two empirical trajectories (each combining a small set of individual solutions) that roughly correspond to the ‘political’ or the ‘criminal’ pathway, respectively. Based on these results, we look more closely at the municipalities of Sardinata and Suárez in order to illustrate how these pathways operate.

Our analysis shows that research on post-conflict violence, theoretically and empirically, has to take subnational variation much more seriously. Theoretically, we should be more open to conceptualizing and investigating causal pathways as complementary, rather than competing explanations, in order to reconstruct the complex micro-dynamics of post-conflict violence. In the case of Colombia, the question should not be whether the assassination of social leaders is a ‘criminal’ or a ‘political’ phenomenon but rather how these respective logics manifest themselves and/or combine in different local settings. As our analysis suggests, both pathways help us understand this post-conflict phenomenon, including the different ways in which ANSAs and previous governance arrangements shape the violence against social leaders.

2. Violence against social leaders in Colombia after the peace agreement

Although commonly referred to as a ‘post-conflict’, the period after the peace agreement between the Colombian government and the FARC has been characterized by disputes over territory and control over illicit markets between other ANSAs not parties to the agreement and the emergence of several FARC dissident groups.Footnote10 The peace agreement brought a decline in most forms of violence (e.g. kidnappings, and overall homicide rates). However, as indicates, the targeted assassination of social leaders rapidly increased.Footnote11 Even though civilians and social activists were targeted throughout Colombia’s civil war,Footnote12 the most recent wave of assassinations reflects dynamics unleashed by the implementation of the agreement, and resembles episodes of targeted violence against social and political activists after previous peace negotiations and agreements.Footnote13

Figure 1. Number of assassinated social leaders in Colombia, 2016–2020.

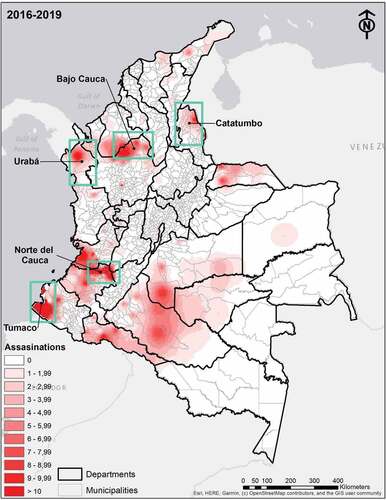

This form of targeted violence occurs in almost all departamentos (provinces), but tends to cluster in some departments and in some municipalities within these (see ) and often in municipalities with a distinct rural profile. The victims reflect the broad spectrum of representatives of non-governmental, societal actors that, in Colombia, is grouped under the concept of líderes sociales. According to data from Indepaz for 2016–2019, the highest shares of assassinated social leaders represented peasant associations (33.6%), indigenous organizations (24.3%), civic associations (10.6%), communal entities such as the local citizen committees (Juntas de Acción Comunal – JAC) (10.1%), groups engaged in coca substitution efforts (9.1%), Afro-Colombian associations (7.6%) as well as trade unions (5.9%) (see Table A1 in the Appendix). Frequently, however, leaders are associated with more than one of these groups. While the different organizations and leaders pursue a broad range of objectives, ranging from the protection of communal land to land restitution and redistribution efforts, or illicit crop substitution, amongst others, the assassinations tend to target actors, particularly from Colombia’s rural peripheries, that have been historically marginalized from local, regional, and national decision-making.

Figure 2. Assassinations of social leaders at the municipal level 2016–2019.

The term ‘social’, while accurately emphasizing their leadership roles in organized civil society groups, tends to deflect attention from the political relevance of these leaders. They not only play important roles within local social organizations and movements, which in and of itself is hardly unpolitical, but, in particular in rural Colombia, social movements are historically closely associated with alternative – usually leftist – political parties.Footnote14 Social leaders, therefore, are often also directly involved in local politics.

The targeted assassination of social leaders has been marked by a high degree of impunity. In 78% of the cases the direct perpetrators remain unknown and we know little about the actual masterminds (see Table A2 in the Appendix). It is therefore unsurprising that this type of violence goes mostly unpunished (El Espectador, 16 September 2020). This type of violence against social leaders is also cheap in monetary terms: According to Michel Forst, UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders, the assassination of a social leader can cost as little as 100 US dollars (Reuters, 4 December 2018). The lack of information about the perpetrators, the impunity that surrounds these cases, and the low cost to violently target social leaders in Colombia resembles similar patterns in other cases of violence against civil society actors.Footnote15

3. Pathways of post-conflict violence

Existing explanations of the recent wave of assassinations of social leaders in Colombia can be summarized in two pathways of post-conflict violence. According to the first pathway, this specific type of targeted violence results from the combination of opportunities for illicit rents (in particular, drug production and traffic) with the dissolution of previous forms of rebel governance in the context of the demobilization of the FARC, which has enabled a whole range of ANSAs competing for the control of these markets and the respective territories. The second pathway, in contrast, stresses that the assassinations reflect attempts by local socio-political elites who – allied with ANSAs – try to violently thwart attempts by emerging sociopolitical challengers to gain political influence in municipalities and enact locally the (modest) reformist agenda encoded in the peace agreement.

We call the first the ‘criminal’ and the second the ‘political’ pathway. We employ these terms to make the pathways relatable to previous academic debates, which tend to focus on either criminal or political actors. Our use of the adjective ‘criminal’ does not mean that this pathway does not involve political elements, as exercising control over a population to control criminal markets is political. As many authors have pointed out, ‘criminal’ actors and ‘criminal’ violence can have political causes and implications.Footnote16 Moreover, the ‘political’ pathway also includes criminal activities, often with the direct involvement of socio-political elites. However, in the first pathway the driving force behind violence is, predominantly, the control over criminal markets, while in the second it is the control over local politics.

3.1 The ‘criminal’ pathway

Despite the cessation of hostilities associated with the end of conflict, violence often continues in post-conflict settings. Even where a resurgence of the armed conflict can be avoided, we often witness overall increases in the level of criminal violence – for example higher homicides rates – and, thus, a transformation from war to post-war crime.Footnote17 These increases can result from a crucial legacy of armed conflict: the presence of ex-combatants with experience in the use of force can readily be employed to regulate criminal markets and populations.Footnote18 Often, the incentive structures created as a result of peace agreements can address the concerns of high-ranking officers, through power-sharing agreements, and of rank-and-file members, through monetary and other reintegration measures. Many middle ranks, however, cannot be effectively satisfied through these measures, making them actors who are likely to employ skills and connections developed in armed conflict,Footnote19 among them their expertise in the use of violence and their pre-existing connections with criminal actors.Footnote20

Connections between many insurgent non-state armed groups and criminal actors often predate the end of conflict. Without implying that the (sole) motivation behind armed insurgency is greed, ANSAs develop relationships with criminal actors during civil war in their attempts to finance their groups and control populations.Footnote21 Moreover, forms of rebel governance established during civil wars, like criminal governance, also regulate illicit markets (for example, through taxation and the enforcement of rules in these markets). Thus, already during war time, ANSAs become active players in illicit markets.

The recent wave of assassinations of social leaders has been explained as a result of the power vacuum that emerged from the demobilization of the FARC.Footnote22 It is well-established that the FARC was successful in constructing forms of rebel governance in certain areas, in varying degrees providing public goods like the administration of justice and regulating illicit markets.Footnote23 As a consequence, the disappearance of the FARC from the territories under their control has been associated with increased killings of social leaders, in particular when other ANSAs were in close proximity.Footnote24

The collapse of governance arrangements established by ANSAs as a result of demobilization processes,Footnote25 together with the limited (or entirely lacking) presence of the state, has created opportunities for pre-existing, transformed or new ANSAs to gain in strength and dispute the control over territories and populations. These violent struggles over the territorial control of criminal markets between rivaling ANSAs come at the expense of local communities and social movements. By claiming human rights, defending access to land, engaging in alternative socioeconomic development projects or simply by resisting extortion or participation in illicit economies, they become a hindrance to the control of lucrative illicit markets, for example, from illegal mining and drug production or trade. ANSAs may also see the activities of social leaders as attracting state action and potentially inviting an unwelcome state presence.Footnote26 As a consequence, ANSAs assassinate social leaders as a strategy of intimidation and demobilization.Footnote27

3.2 The ‘political’ pathway Footnote28

State-building in the Colombian periphery was historically characterized by a process in which the central state informally delegated the construction and maintenance of subnational sociopolitical orders to local elites. The result has been the consolidation of informal authoritarian orders at the subnational level, in which democratic rules as established at the national level are subverted, often through the use of violence.Footnote29

Typically, in the case of Colombia, these subnational orders are hybrid in two regards. First, they are characterized by multifold connections between official elites, which formally control local state institutions, and different types of illegal and armed groups. During Colombia’s decades long conflict, many subnational orders were indeed non-state orders, controlled by either insurgents or paramilitaries.Footnote30 However, in other areas, forms of governance developed in which armed and criminal actors collaborated with local elites and state institutions in the provision of order.Footnote31 In these latter areas, it is therefore frequently difficult to distinguish between criminal groups and local socio-political elites, in particular because the latter are often directly engaged in illicit markets too, or because criminal ‘elites’ eventually became political elites themselves.Footnote32 In this sense, the Colombian case reflects the variations in forms of ‘extra-legal governance’ highlighted by other scholars of rebel governance and wartime orders.Footnote33

Second, these subnational orders are also hybrid in terms of their political regime type. Following the concept introduced by Levitsky and Way with a view to national-level regime types,Footnote34 we define subnational competitive authoritarianism as a hybrid political order at the subnational level in which formally established democratic institutions are undermined to the extent that electoral competition becomes highly unfair.Footnote35 In Colombia’s decentralized, but unitary system, subnational political actors are unable to adapt the formal rules to their advantage (for example by banning opposition parties or creating legal constraints to their activities), prompting them to subvert democratic processes through informal means, including the use of ‘privatized state violence’.Footnote36 In this sense, both forms of hybridity are directly related: multiparty elections are the mechanism through which local political leaders are determined. In these elections, however, violence by established elites, executed by ANSAs, is used to factually limit access to power.

As was the case with previous peace processes in Colombia,Footnote37 the 2016 peace agreement has presented a serious challenge for these established forms of local competitive authoritarianism.Footnote38 As Gutiérrez Sanín and colleagues have argued, the ‘pro-peace policies’ adopted during the government of Juan Manuel Santos (2010–2018) and particularly in the wake of the 2016 agreement meant an acute threat to territorial power structures and local socio-political elites in particular.Footnote39 In addition to provisions related to the FARC’s demobilization process and transitional justice, the peace agreement – while refraining from envisaging fundamental structural changes to the country’s economic and political system – provides for an agenda of rural reform and the building of ‘territorial peace’ in Colombia’s countryside. Specific provisions and programs included land restitution and voluntary coca substitution as well as participatory local development programs (PDETs) focused on areas historically affected by the armed conflict. Overall, the peace process also motivated local communities, social movements and leftist parties to mobilize in the name of the multifold promises contained in the agreement and use the emerging social and political space to challenge exclusionary power structures at the local level. The assassination of social leaders can be understood as reflecting a backlash from local elites, who respond to these bottom-up challenges by resorting to targeted violence as a means to deter further mobilization.Footnote40

In a nutshell, the political pathway of post-conflict violence starts with pre-existing local competitive authoritarian orders, which prevail in a given subnational setting after the peace agreement and are sustained through the use of violence by local elites in conjunction with ANSAs. In the context of the peace process, these elites are then challenged by socio-political forces that represent marginalized groups. In turn, local elite groups and their allies among ANSAs, respond with targeted violence against social activists in order to preempt these challengers from successfully disputing local power.

4. Identifying the pathways: QCA

Previous studies have explored the impact of individual variables on the occurrence and frequency of lethal violence against social leaders.Footnote41 While these statistical analyses provide useful insights into the factors that correlate with the assassination of social leaders, the two pathways outlined above suggest that multiple combinations of factors can cause the outcome at hand. Therefore, we apply a configurational method, QCA, to identify the different configurations that explain high levels of violence against social leaders. Given the nature of QCA, we focus on an intermediate number of cases, namely: 41 municipalities that belong to those regions that are characterized by a high incidence of assassinations of social leaders (Norte del Cauca, Catatumbo, Urabá, Bajo Cauca, and Tumaco, see ). Within these regions and, thus, our 41 cases exhibit great variation in the numbers of assassinations, with municipalities ranging from exceptionally high numbers to cases with not a single one.

4.1 Method and operationalization

QCA is based on set theory and aims at identifying ‘conditions of occurrence’ by using rules of logical inference.Footnote42 In contrast to other methods, QCA explicitly embraces the idea of causal complexity by emphasizing (among other aspects) equifinality and conjunctural causation. In terms of equifinality, QCA assumes that there are frequently different causes or multiple combinations of conditions that can produce one and the same social phenomenon.Footnote43 In line with conjunctural causation, QCA also assumes that an individual factor may not be sufficient to produce an outcome, but in combination with other conditions can still be important.

In the following analysis, we use fuzzy-set QCA. Unlike crisp sets, which are dichotomous by nature, cases in fuzzy sets can exhibit diverse degrees of membership.Footnote44 Two thresholds are used to establish the degree of set membership: total inclusion (a case is fully included in the set of positive cases); and complete exclusion (a case is not part of the set). Finally, we use a value of 0.5 as an indifference threshold (cases are neither included nor excluded). It is worthwhile mentioning that this point is exclusively theoretical, and we were careful not to locate cases at this empirically and logically nonexistent spot.

For each case, then, each condition is assigned a value (associated with a set membership level). These intervals should not be interpreted under the logic of probability theory. On the contrary, they are ways of establishing degrees of membership within a set. In this way, fsQCA does not use scale variables but fuzzy sets.Footnote45

With a view to the outcome (ASSE), there are no theories or broader comparative studies that would suggest a specific threshold to distinguish high from low levels of targeted violence against social leaders. We, therefore, defined the thresholds based on empirical case knowledge. A municipality without any assassination clearly is fully excluded from the set (34% of cases). Since municipalities with one assassination do exhibit the phenomenon at hand, we defined 0.9 as the indifference threshold.Footnote46 Furthermore, we defined ten assassinations as the threshold for full inclusion. At this high level, the targeted violence against social leaders can be read as an all-out attempt to destroy the organizational basis of marginalized groups and thereby thwart any form of bottom-up mobilization. Empirically, 20% of our cases attain this level of full membership.

Turning to the potential causes, we focus on conditions that are associated with our two pathways. Drawing on the state of research discussed in Section 3, we identified those conditions that best capture the two pathways (and for which we also have data). Depending on their respective characteristics, these conditions were calibrated either in a crisp (i.e. the condition is present or absent) or in a fuzzy way (degrees of membership to a set). Table A3 in the Appendix summarizes the thresholds that were defined for the outcome and all causal conditions, as well as data sources.

Regarding the criminal pathway, we analyze four conditions: the local presence of ANSAs, the dissolution of previous FARC control, as well as the existence of illicit markets and overall levels of violence:

4.1.1. Municipalities with high levels of coca cultivation (COCA)

Coca cultivation indicates the presence of an illicit economy and, therefore, a valuable commodity ANSAs fight to control. Given that there are no theoretical priors to guide the calibration process, the thresholds were defined based on the number of cultivated hectares of coca that reasonably allow for large volumes of production. In this way, we define the total inclusion threshold in municipalities at 1,600 ha of coca (one standard deviation above the mean of hectares), the indifference point at 600 ha and the threshold of full exclusion at 0 ha.

4.1.2. Municipalities with previous violent FARC presence (FARC)

We measure the occurrence of violent actions by the FARC between 2010 and 2016, that is, before their demobilization, dichotomously distinguishing between any actions (inclusion) or none (exclusion). The logic, here, is that the disappearance of the FARC from territories in which they were active, enabled the entry and/or strengthening of competing ANSAs, changing the balance in local power, prompting competition between ANSAs and causing more violence.

4.1.3. Municipalities with presence of armed non-state actors (ANSAs)

In line with the criminal explanation, we expect that the existence of ANSAs in a municipality is related to violent confrontation between these groups and the use of violence against social leaders to elicit cooperation and acquiescence of civilians. Here, again, we simply distinguish between presence (inclusion) and no presence (exclusion).

4.1.4. Municipalities with extreme levels of lethal violence (HOM)

It is possible that the observed violence against social leaders is simply a feature of municipalities that are highly violent in general and, in line with the criminal pathway, high homicide rates are considered as the typical expression of transitions from war to criminal violence. In our case, we cannot use conventional standards for identifying high homicide rates (for example, those established by the WHO) because this type of violence is simply too high across the cases. The threshold for total inclusion, a homicide rate of 1.72 per thousand inhabitants, was chosen so as to correspond to the situation in the most violent cities in the world during the last two decades. The indifference threshold was established at 0.61 homicides per thousand inhabitants, which represents a standard equivalent to that of the 15 to 20 most violent cities in the world.

Regarding conditions associated with the political pathway, we focus on the electoral strength of leftist parties, the level of electoral political participation, and the intensity of land restitution efforts:

4.1.5. Municipalities with electorally strong left-wing parties (LEFT)

We use the percentage of votes won by leftist parties in city council elections as a proxy to indicate the level of ‘threat’ posed to local elites ‘from below’. As explained above, social leaders in Colombia have traditionally been central figures of leftist political movements. A good electoral performance of leftist parties is, therefore, usually a good indicator of strong local social movement mobilization in rural Colombia and, thus, signals the existence of a relevant challenge to local elites in a given municipality.Footnote47 Based on theoretical considerations, we set the indifference threshold at 7% for leftist parties.Footnote48 The threshold for total inclusion – 15% of the vote – reflects the percentage achieved by the strongest political parties in Colombia’s highly fragmented party system. 0% is defined as indicating total exclusion.

4.1.6. Municipalities with high levels of electoral turnout (PART)

Local competitive authoritarianism is characterized by low and controlled levels of voter turnout. In this context, only certain voters are encouraged to vote, because ANSAs use (the threat of) violence to dissuade citizens known to support political challengers from participating.Footnote49 Municipalities with low levels of participation indicate the presence of a local order that is de facto relatively exclusionary and authoritarian. We expect that the absence of this condition (i.e. low voter turnout) contributes to the outcome. In this case, the thresholds were established as follows: full membership requires at least 75% of electoral turnout (an international standard associated with a relatively high level of turnout), 50% (the point where the level of participation begins to be higher than that of abstention) indicates indifference, and 0% implies full exclusion.

4.1.7. Municipalities with high levels of efforts of land restitution (REST)

Land distribution is a traditional source of conflict in Colombia. Efforts at land restitution, which have accelerated since the start of the land restitution program in 2011, are often spearheaded by local communities and social movements, and active mobilization in terms of demand for restitution can provoke violent reaction by local elites and allied ANSAs.Footnote50 We therefore expect that high number of restitution claims to indicate strong mobilization for land and a serious bottom-up challenge to established elites. Lacking theoretical priors to inform calibration, we used the median of restitution claims (median associated with all municipalities in the country) as the indifference threshold.Footnote51 For the full membership threshold we used the 75 percentile.

4.2 Results

The analysis of necessary conditions, which is documented in the appendix (Table A4) indicates that three causal conditions exceed the consistency threshold of 0.9 to be regarded as a necessary condition: the presence of other ANSAs, a high percentage of the leftist vote, and a high number of land restitution claims. Given that the first condition is linked to the criminal pattern and the other two to the political one, this lends some initial support to both pathways. Yet, coverage scores of 0.55, 0.57, and 0.58, while exceeding the minimum coverage threshold (0.5), are far from reaching a more demanding standard.Footnote52 This suggests that none of the conditions can be regarded as necessary for the overall set of cases.

While the question of necessary conditions is indisputably relevant, for our pathway argument, sufficiency is decisive. In this sense, summarizes all combinations of conditions that are empirically associated with the outcome ‘municipality with high levels of violence against social leaders’.Footnote53 The truth table is documented in the appendix (Table A4).

The cut-off threshold for the sufficiency analysis was 0.85. The consistency for the result is 0.85 (exceeding the minimum theoretical requirements), while the rate of coverage is 0.71. The solutions, thus, explain a reasonably high proportion of cases.Footnote54

We grouped the results from the sufficiency analysis in two broad trajectories that are close, but not identical to the theoretical pathways previously discussed (see ). The first trajectory (T1) represents a solution that is broadly in line with the ‘criminal’ pathway. Municipalities in this trajectory are characterized by a previous violent FARC presence, the existence of (multiple) ANSAs and significant amounts of coca cultivation. Here, the assassination of social leaders plausibly results from efforts by ANSAs that have used the opportunity offered by the demobilization of the FARC to establish or increase control over illicit economies and the respective strategic territories. Of the 41 municipalities included in the analysis, 7 municipalities are covered by this solution (see ).

Table 1. Sufficient combinations of conditions for high levels of assassinations.

Table 2. Municipalities by pathways.

The second trajectory includes two configurations that come closest to explaining the outcome in terms of the ‘political’ pathway. As the raw coverage indicates, the proportion of cases which can be explained by these solutions is 0.584 and 0.434, respectively. This corresponds to 18 out of the 41 municipalities. Solutions in this trajectory include municipalities in which the electoral strength of leftist parties and a significant number of land restitution processes signals bottom-up challenges to elite rule – indicating that violence against social leaders, in these cases, may result from the efforts by local elites to thwart such efforts. Still, most of the cases also exhibit a high electoral turnout. Our results, thus, indicate that the condition ‘high support for leftist parties’ combined with ‘high turnout’ brings about more violence. While not aligned with our theoretical expectation this does make sense. The combination might precisely point to cases in which civil society groups mobilize electorally (thus, higher turnout) to access spaces of local power, thus threatening established elite control over local government.

Both solutions in the political trajectory are also characterized by a previous, violent FARC presence as well as by either the current presence of ANSAs or high levels of homicide. In the absence of other conditions associated with the criminal pathway, particularly the presence of significant coca cultivation, this can indicate that in these municipalities armed actors are an important condition for violence against social leaders to occur or that these are exceptionally violent municipalities, but that violent actions are not primarily driven by the dispute over criminal markets. In the following section, the case of Suárez will illustrate this point.

5. Exploring the pathways: illustrative case studies

The following illustrative case studies look more closely at two municipalities that each fit exclusively in one of the empirical trajectories identified through the QCA, corresponding with either the ‘criminal’ (Sardinata) or the ‘political’ pathway (Suárez). Empirically, they are based on interviews with local leaders, reports from the media and NGOs as well as on secondary literature.

5.1 Sardinata: illustrating the ‘criminal’ pathway

Sardinata is a municipality located in the northeast of Colombia, in the department of Norte de Santander in the Catatumbo region, bordering Venezuela. According to the QCA results, it closely resembles the criminal pathway in that it displays two key conditions that are empirically associated with the killing of social leaders: presence of various ANSAs and significant existence of coca crops for illicit use. In addition, however, it also features a high demand for land restitution, a condition that is theoretically associated with the political pathway. As we will show, assassinations of social leaders in Sardinata plausibly result from the violent struggle between ANSAs that compete over the control of territories and corridors that are of strategic relevance for their criminal activities, in particular coca cultivation and drug production. Thus, social activists who engage in substitution programs and build alternative development projects are threatened by ANSAs who benefit from coca cultivation.Footnote55

Sardinata is currently one of the ten municipalities in the country with the highest area of coca cultivation: 4602 ha. In the Catatumbo region, the arrival of the coca economy dates back to 1980.Footnote56 In the aftermath of the peace agreement there has been a dramatic increase in coca crops.Footnote57 In addition, Sardinata represents a strategic corridor for the production and transport of cocaine because it is located very close to the Venezuelan border.

Due to the extensive cultivation of coca, Sardinata was included by the national government in the National Illicit Crop Substitution Program (PNIS), instituted in the wake of the peace agreement with a view to enabling the voluntary, community-led substitution of illegal crops.Footnote58 Under President Duque, however, the municipality also became a main target of state efforts at forced coca eradication, which only intensified during the pandemic and provoked confrontations between the community and public security forces.

Coca growers in Sardinata are organized in deep-rooted peasant organizations, such as the Coordinadora Nacional de Cultivadores de Coca, Amapola y Marihuana (COCCAM) and the Asociación Campesina del Catatumbo (ASCAMCAT). The representatives of these associations negotiate with the national government when it comes to the substitution programs. Consequently, these social leaders are targeted by the illegal armed actors who do not want to see peasant communities turning away from coca cultivation.

Sardinata has also historically seen the presence of multiple ANSAs since 1964, such as the National Liberation Army (ELN), the Popular Liberation Army (EPL, also known as Los Pelusos), and the FARC. These three guerrillas coexisted until the late 1990s, when the arrival of paramilitary groups increased territorial disputes in the municipality, provoking massive displacement of civilians.Footnote59

After the peace agreement, new dissident groups emerged as a result of the ruptures that the FARC suffered during and after the negotiations,Footnote60 and today diverse FARC dissident factions are violently disputing the territorial control over illicit economies in the Catatumbo region, partially taking over territories that were previously the domain of the FARC.Footnote61 Despite their different trajectories, all armed groups have demonstrated extremely violent repertoires, particularly against social leaders and coca growers.

The centrality of the coca and cocaine economy in a region of strategic importance for the drug trade, coupled with the active presence of multiple ANSAs seeking to establish control over the municipality creates significant risks for social leaders. Despite their different trajectories, all armed groups perceive social leaders as individuals who impede the development of coca crops, their main source of financing.Footnote62 In fact, three out of the six leaders assassinated between 2013 and 2021, were community representatives in PNIS programs, killed after the peace agreement in 2016 (see Table A7 in the Appendix).

The case of Luis Alfredo Contreras clearly suggests an assassination in line with the ‘criminal’ path. Contreras coordinated eradication and substitution projects in Las Mercedes, Sardinata. Previously, Contreras had served as a representative of the local citizen committee at Las Mercedes, being a visible leader in the area because of his commitment to replacing coca cultivation with cocoa. On 17 January 2019, he was detained by unknown armed men who removed him from his vehicle and subsequently killed him. While the case remains unsolved, one of the most compelling hypotheses for this homicide followed by criminal investigators points to his involvement in coca crop substitution efforts in the same area where ANSAs are located as the motive (La Opinion, 19 January 2019).

Sardinata has also a significant history of forced displacement without an effective response from the state.Footnote63 From 1980 to 2013 the inhabitants of the broader Catatumbo region suffered sixty-six massacres, which caused the displacement of more than 120,000 inhabitants.Footnote64 In the wake of the demobilization of the paramilitaries in the early 2000s and the start of the land restitution program in 2011, the demands for land restitution increased.Footnote65 However, given the reactivation of the violent disputes for territorial control, this type of request implies a risk for the leaders who represent the communities of land restitution. Although unknown actors perpetrate 70% of the assassinations in the Catatumbo region, the Ombudsman’s Office has warned of armed confrontations between different ANSAs that are targeting local citizen committees’ representatives as well as peasant leaders.Footnote66 The killing of Duvis Antonio Galvis in January 2014 is related to land restitution and the coca economy. Galvis served as a liaison for the ASCAMCAT and the families of that place to execute reparation projects for the victims of the forced eradication of crops. In addition, ASCAMCAT has been promoting comprehensive agrarian reform to solve the needs of the peasants (Prensa Rural, 29 January 2014).

5.2 Suárez: illustrating the ‘political’ pathway

Suárez is a municipality located in the sub-region of Norte del Cauca, the northwestern part of the Cauca department. The case of Suárez comes close to the ‘political’ pathway displaying two conditions of this path: a high level of electoral support for leftist parties (26.54%, i.e. a value between the 75th and 90th percentile of all municipalities), and a relatively high level of restitution requests (69, well above the indifference threshold of 31). It also had a strong previous presence of the FARC and exhibits extremely high homicide levels (1.23 for every 1,000 inhabitants).

Historically, in Suárez, Afro-descendant populations developed traditional mining activities, becoming owners of mines and lands. At the beginning of the 1930s many of these lands were dispossessed with the arrival of foreign mining companies. These processes of dispossession intensified during the period of bipartisan violence in which Black peasants, mostly affiliated with the Liberal Party, confronted conservative forces of landowning families from nearby municipalities such as Caloto and Miranda. This tradition also became evident in the 1980s when the inhabitants of the municipality confronted the state in response to processes of dispossession that resulted from the construction of the Salvajina dam.

In the 2000s, foreign companies, such as the multinationals Anglo Gold Ashanti and Cosigo Resort, were granted mining concessions in areas of traditional mining. This generated a deep territorial conflict with the local mining communities. The concessions were granted in disregard of the constitutional right to prior consultation of Afro-Colombian communities. When the Colombian state unsuccessfully ordered the eviction of the miners, criminal gangs eliminate of resulting from paramilitary demobilization processes, such as the Aguilas Negras and Los Rastrojos, responded by persecuting, intimidating, and murdering community leaders.

Despite this history of political violence and repression of ethnic communities, Suárez also displays high levels of mobilization by these same communities. It is characterized by a very active political life, with key socio-political organizations representing the Afro-Colombian and the indigenous populations. The Afro-Colombian population is organized in nine community councils with great influence represented by the Association of Community Councils of Norte del Cauca (ACONC). The local indigenous population is represented by the Association of Cabildos del Norte del Cauca (ACIN). For its part, the (mestizo) peasant population has associations and its representatives also head the local citizen committees (JACs).Footnote67 Despite the violence they have been facing, these associations and organizations have continued to mobilize their constituencies, generate policy proposals and also (indirectly) participate in local electoral politics. This is reflected in the success of leftist and alternative parties, some of them of ‘ethnic’ origin like MAIS (13.79%) and AICO (12.75%), in the 2015 local elections.

Since 2016, leaders who defend pro-peace policies as well as representatives of societal alliances that mobilize in the name of territorial defense and/or for leftist political agendas have been threatened and even assassinated. Many of the leaders assassinated in the region pushed for the implementation of key provisions of the peace agreement, such as the voluntary substitution of coca plants (PNIS) or the PDET program. The victims are leaders of Afro-Colombian, indigenous, and peasant organizations, especially those linked to left-wing organizations such as Marcha Patriótica or Colombia Humana (see Table A8 in the Appendix).

Violence was particularly acute during 2019, the year in which municipal elections were held. For example, Cesar Cerón who was a candidate for mayor from the Colombia Humana, a leftist party and a coalition of indigenous, Afro-descendant and peasant organizations suffered an assassination attempt in May 2019. Francia Márquez, a recognized Afro-Colombian leader, member of the Afro-Colombian community council of Suárez, and in 2022 elected Colombian Vice-President, also suffered an attack in that same month, during a meeting with several Afro-Colombian organizations.

In September 2019, Karina García, another mayoral candidate, was assassinated. Although there is a detainee for her murder, John Jairo Osorio (a member of the FARC dissident group ‘Carlos Martínez’), several people from the municipality claim that the murder of Karina García was paid for by a local rival politician, who subcontracted a member from an ANSA to eliminate a political rival.Footnote68

While the ‘political’ pathway offers a plausible explanation for an important part of the violence facing social and political leaders in Suárez since 2016, recent developments also show that the case might be changing and that future violence against social leaders might increasingly be the product of conditions associated with the ‘criminal’ pathway. The presence of multiple ANSAs in Suárez in the past decades is well documented. Given the strategic position of the municipality, the FARC guerrilla had an important territorial presence since the 1980s. Back then, Suárez as well as neighboring Buenos Aires became a strategic corridor that the FARC used to connect its Central command and the Western command. At the beginning of 2000, paramilitary forces contended with the FARC for territorial control of the region. The arrival of these groups has been marked by episodes of massive violence, including the Naya Massacre in which more than 100 people were killed.

Recently, a dissident group of the FARC (‘Dagoberto Ramos’ Unit), which exercises control over the central mountain range in nearby municipalities, is also present in Suárez. This group seeks control of strategic corridors, as well as illegal income from mining and the drug economy. With the growing importance of the latter, it is likely this case will progressively start acquiring more features of the criminal pathway.

6. Conclusions

In this article, we present two theoretical pathways that can account for the assassinations of social leaders in post-agreement Colombia. Many studies suggest that this specific type of violence results from efforts by armed non-state actors (ANSAs) to control lucrative illicit markets, particularly at a time when ‘rebel orders’ established by the FARC disappeared in the course of their demobilization and the state failed to mount an effective presence. Adding to this ‘criminal’ pathway, there is also a ‘political’ pathway of post-conflict violence. Here, targeted violence against social leaders results from efforts by local elites to thwart political and social changes envisaged in the peace agreement and locally spearheaded by social movements and community organizations, frequently in alliance with leftist parties. As they have done in the past, local elites, which are in many places intimately linked to ANSAs in the context of de facto authoritarian local orders, seek to dispel this threat by using violence. Both pathways include the use of violence against civil society actors by ANSAs and impact the politics of these regions. Our analysis shows that even cases that have been interpreted as ‘criminal’ have political elements. However, it is important to analytically distinguish the different logics of violence of each pathway.

Given the diversity that has historically characterized local governance arrangements throughout Colombia, which is also reflected in the current post-agreement context, we suggest that both pathways are at play in this time and, thus, offer valuable explanations for the phenomenon at hand. Indeed, a fuzzy-set QCA of 41 municipalities finds support for the existence of two empirical trajectories that approximate the theoretical pathways. In addition, two brief case studies on municipalities that relatively correspond to either the ‘criminal’ (Sardinata) or the ‘political’ logic (Suárez) served to illustrate the operation of the respective pathway. Whereas social leaders tend to be assassinated in Sardinata in the midst of disputes between ANSAs for the control of criminal markets, violence against social leaders in Suárez reflects elite attempts to limit political competition, in particular in the face of mobilization by social movements. At the same time, however, evidence from our cases also suggests that the two analytically distinct causal pathways can empirically coexist and merge in a given local setting. This latter finding not only has important implications for research on post-conflict violence, but also indicates that policy efforts to prevent this violence – who for the most part see this as a purely ‘criminal’ phenomenon – need to take elements of the ‘political’ pathway into account.

While we have empirically focused on the case of Colombia, the two theoretical pathways developed in this article provide valuable insights for the study of post-conflict violence in other settings. Studies of wartime orders highlight the diversity and diverse roles of armed actors, their varying relationships with other, state and non-state actors, and the implications of these variations for dynamics of violence.Footnote69 Our analysis highlights how this variation in local governance arrangements during civil war is also reflected in (emerging) post-conflict settings, shaping the dynamics of post-conflict violence at the local level. While similar actors (especially ANSAs) may exist across the territory, the local patterns of violence exercised by them does not necessarily follow one universal logic. With our analysis, we show how it is possible to take such patterns of territorial variation seriously and embrace causal complexity, both theoretically and empirically, without losing the ability to build general explanations.

Ethics statement

The research was conducted in compliance with Colombian regulations and the Research Ethics Committee of Universidad Icesi (Colombia). To protect informants, oral informed consent was obtained from informants and no information that can reveal their identity is provided.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (87.9 KB)Acknowledgments

A previous version of this article was presented at the virtual workshop “Fractures and Continuities of Changing Rule in (Post-)Conflict Settings” (31 March-1 April 2021), the 2021 REDESDAL Conference, the 2021 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association (APSA), the Kroc-Kellogg Workshop at the University of Notre Dame, and the Comparative Politics Workshop at CUNY. We thank the participants of these workshops and, in particular, Ana Arjona, Desmond Arias, André Bank, Abby Córdova, Gary Goertz, Isabel Güiza-Gómez, Thorsten Gromes, Lindsay Mayka, Eduardo Moncada,, Hanna Pfeifer, Regine Schwab, Guillermo Trejo, and Susan Woodward for immensely helpful comments and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Juan Albarracín, upon reasonable request.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/09592318.2022.2114244

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Juan Albarracín

Juan Albarracín is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Political Science, University of Illinois, Chicago (IL, USA).

Juan Corredor-Garcia

Juan Corredor-Garcia is PhD Student at the Graduate Center, City University New York (CUNY, New York, USA).

Juan Pablo Milanese

Juan Pablo Milanese is Professor of Political Science and Director of the Department of Political Studies at Universidad Icesi (Cali, Colombia).

Inge H. Valencia

Inge H. Valencia is Associate Professor and Director of the Department of Social Studies at Universidad Icesi (Cali, Colombia).

Jonas Wolff

Jonas Wolff is Professor of Political Science at Goethe University Frankfurt and Head of the Research Department ‘Intrastate Conflict’ at the Peace Research Institute Frankfurt (PRIF, Germany).

Notes

1. See Albarracín et al., “Local Competitive Authoritarianism”; Ávila, ¿Por qué los matan?; Gutiérrez Sanín et al., “Paz sin garantías”; Holmes and Pavon-Harr, “Violence after Peace”; International Crisis Group, “Leaders under Fire”; and Prem et al., Selective Civilian Targeting.

2. Suhrke, Astri. “The Peace in Between,” 3.

3. Kurtenbach and Rettberg, “Understanding relation between war economies and post-war crime,” 1–2.

4. International Crisis Group, “Leaders under Fire,” 11–20; Prem et al. Selective Civilian Targeting, 4–8; Salas, Wolff, and Camelo, “Towards violent peace?”, 510–513.

5. Prem et al., Selective Civilian Targeting, 25–26. For the case of Tumaco, see Salas, Wolff, and Camelo, “Towards violent peace?”, 513. On the varying configurations of rebel governance established by the FARC and other armed groups see Arjona, Rebelocracy, 170–201.

6. See Albarracín et al., “Local Competitive Authoritarianism”; Ávila, ¿Por qué los matan?; Gutiérrez Sanín et al., “Paz sin garantías”.

7. See Albarracín et al., “Local Competitive Authoritarianism,” 13–15; Gutiérrez Sanín et al., “Paz sin garantías,” 39.

8. Suhrke, “The Peace in Between,” 6.

9. Kasfir, Frerks, and Terpstra, “Introduction.” See also Staniland, “States, Insurgents, and Wartime Political Orders,” 247.

10. In the current Colombian context, ANSAs that have gained in strength since 2006 include pre-existing guerrilla organizations (in particular, the National Liberal Army – ELN), neo-paramilitary groups that emerged from the demobilization of the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC) in the early 2000s, more ‘purely’ criminal organizations, as well as a range of so-called FARC dissident groups.

11. The numbers cited come from the Instituto de Estudios para el Desarrollo y la Paz (Indepaz, www.indepaz.org.co). The precise numbers are contested, but the overall trend is not; the Indepaz data is generally considered relatively reliable. See Albarracín et al., “Local Competitive Authoritarianism.”

12. Kaplan, Resisting War, 2–3.

13. Steele, Democracy and Displacement, 121–143.

14. Carroll, Violent Democratization, 43.

15. Middeldorp and Le Billon, “Deadly Environmental Governance,” 328–329.

16. Barnes, “Criminal politics,” 972; Arias, “How Criminals Govern in Latin America and the Caribbean,” 1–18.

17. Kurtenbach and Rettberg, “Understanding relation between war economies and post-war crime,” 1–4.

18. Steenkamp, “In the shadows of war and peace,” 361.

19. Daly, “The Dark Side of Power-Sharing,” 336–338.

20. Steenkamp, “In the shadows of war and peace,” 367.

21. Ibid, 361.

22. International Crisis Group, “Leaders under Fire,” 11; and Prem et al., Selective Civilian Targeting, 6–7.

23. Arjona, Rebelocracy, 180–192, Gutiérrez D., State, Political Power and Criminality in Civil War, 17.

24. Prem et al., Selective Civilian Targeting, 23.

25. Nussio and Howe, “When Protection Collapses,” 850–851.

26. Prem et al., Selective Civilian Targeting, 11.

27. CINEP et al., ¿Cuáles son los Patrones?; UNHCHR, Situation of human rights in Colombia.

28. The following section and the presented theory draws from Albarracín et al., “Local Competitive Authoritarianism,” 13–19.

29. Eaton and Prieto, “Subnational Authoritarianism and Democratization in Colombia”; Gutiérrez Sanín et al., “Paz sin garantías,” 38–42; González and Otero, “La presencia diferenciada del Estado,” 35–36; Robinson, “Colombia: Another 100 Years of Solitude?”, 44.

30. Arjona, Rebelocracy, 84–110.

31. Duncan, Más que plata o plomo.

32. Albarracín et al., “Local Competitive Authoritarianism,” 14.

33. Kasfir, Frerks, and Terpstra, “Introduction”.

34. Levitsky and Way, Competitive Authoritarianism, 5–13.

35. See also Gibson, Boundary Control, 9–34.

36. Roessler, “Donor-Induced Democratization and the Privatization of State Violence,” 209.

37. Carroll, Violent Democratization, 1–49.

38. Albarracín et al., “Local Competitive Authoritarianism,” 18–19.

39. Gutiérrez Sanín et al., “Paz sin garantías”, 37–42.

40. Albarracín et al., “Local Competitive Authoritarianism,” 19.

41. Albarracín et al., “Local Competitive Authoritarianism”; Prem et al., Selective Civilian Targeting.

42. Berg-Schlosser et al., “Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) as an approach”; Schneider and Wagemann, Set-theoretic methods for the social sciences, 3.

43. Ragin, Redesigning social inquiry, 23; Schneider and Wagemann, Set-theoretic methods for the social sciences, 8–9.

44. Ibid, 13–14.

45. Basurto and Speer, “Structuring the Calibration of Qualitative Data”, 159; Ragin, Redesigning social inquiry, 29–42.

46. Although 0.9 is factually an impossible threshold, this decision was also necessary for methodological purposes. Given that one assassination is a very frequent outcome. It also indicates the presence of some level of violence, qualitatively different from its total absence. Yet having 1 as the indifference threshold would result in a high number of cases precisely on this threshold, presenting difficulties as a state of complete blurriness cannot exist empirically. Using the 0.9 threshold enables us to indicate that cases with one assassination tend more towards full inclusion than exclusion.

47. Carroll, Violent Democratization, 43.

48. According to Gallagher and Mitchell (2008, 607), about 6.8% of the votes are necessary for a party to win a seat in a collegiate body with a total of eleven seats. Eleven seats are the closest whole number to the average district magnitude of the electoral districts in the municipal councils’ elections in Colombia, 10.7.

49. In the Colombian case, ANSAs have tended to depress political participation in comparison with areas without their presence. More specifically, studies found that pro-government militias were more likely to promote ‘differentiated’ electoral turnout, violently repressing voters associated with leftist parties, including using forced displacement to reshape entire electorates, while encouraging turnout from voters close to allied politicians (Garcia, “Sobre balas y votos”; Steele, Democracy and Displacement). Insurgent groups, like the FARC, discouraged electoral participation, for example, by hindering the opening of polling stations.

50. Gutiérrez Sanín et al., “Paz sin garantías”, 25–31.

51. The median was selected and not the mean because the distribution of the data is not normal (most of the cases have values very close to zero).

52. This appreciation can be reinforced by reviewing the location of the points in the XY graphs (see appendix).

53. For this analysis of sufficiency, we chose the intermediate solution, which allowed us to achieve a result that balances parsimony (i.e. it includes fewer conditions for a given solution) and reliability. In contrast, the parsimonious solution did not reach a sufficiently high coverage measure (0.65), while the complex solution would have meant using difficult counterfactuals, which we find unconvincing in this case (see results of the complex and parsimonious solutions in the appendix).

54. The appendix also documents the results of the non-outcome, that is to say, the combinations of conditions that are associated with the absence of assassinations of social leaders. It is important to note that these combinations are consistent with the analysis presented in this article (even if the coverage of all solutions tends to be low).

55. Gutiérrez and Thomson, “Rebels-Turned-Narcos?”, 8.

56. CNMH, Catatumbo, 114.

57. UNODC, “Colombia”.

58. Gutiérrez Sanín, “Fumigaciones, incumplimientos, coaliciones y resistencias”, 476.

59. CNMH, Con licencia para desplazar.

60. Álvarez, Pardo, and Cajiao, “Trayectorias y dinámicas territoriales”, 12.

61. Garzón et al., La Segunda Marquetalia, 14–22.

62. Cuesta, Las Garantías de Seguridad, 17–18.

63. Carrascal, “El desplazamiento forzado interno,” 98.

64. CNMH, Con licencia para desplazar, 19.

65. Ibid, 24.

66. Garzón, Cuesta, and Zárate, El Catatumbo.

67. Escobar, Entre la incertidumbre y el acomodo, 16.

68. This claim is based on informal interviews with people who must remain anonymous for safety reasons. As part of the investigation into Garcia’s assassination, evidence has surfaced that corroborates the account that members of ANSAs were hired by a person whose identity has not been revealed, to eliminate a political rival (El Espectador, 5 September 2020).

69. Staniland, “States, Insurgents, and Wartime Political Orders”; Kasfir et al., “Introduction”; Arjona, Rebelocracy.

Bibliography

- Albarracín, Juan, Juan Pablo Milanese, Inge Helena Valencia, and Jonas Wolff. “Local Competitive Authoritarianism and Post-Conflict Violence. An Analysis of the Assassination of Social Leaders in Colombia.” Unpublished manuscript, 2022.

- Álvarez, Eduardo, Daniel Pardo, and Andrés Cajiao. Trayectorias y dinámicas territoriales de las disidencias de las FARC. Bogotá: Fundación Ideas para la Paz, 2018.

- Arias, Desmond. “How Criminals Govern in Latin America and the Caribbean.” Current History 19, no. 814 (2020): 43–48.

- Ariel, Ávila. ¿Por qué los matan? En Colombia cada día asesinan dos líderes o lideresas sociales. Radiografía de un fenómeno que está matando nuestra democracia. Bogotá: Planeta, 2020.

- Arjona, Ana. Rebelocracy: Social Order in the Colombian Civil War. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

- Barnes, Nicholas. “Criminal Politics: An Integrated Approach to the Study of Organized Crime, Politics, and Violence.” Perspectives on Politics 15, no. 4 (2017): 967–987. doi:10.1017/S1537592717002110.

- Basurto, Xavier, and Johanna Speer. “Structuring the Calibration of Qualitative Data as Sets for Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA).” Field Methods 24, no. 2 (2012): 155–174. doi:10.1177/1525822X11433998.

- Carrascal, Ana María. “El desplazamiento forzado interno en la región del Catatumbo: Vulneración masiva de derechos.” Reflexión Política 21, no. 42 (2019): 94–107. doi:10.29375/01240781.3467.

- Carroll, Leah Anne. Violent Democratization: Social Movements, Elites, and Politics in Colombia’s Rural War Zones, 1984-2008. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame, 2011.

- CINEP et al. ¿Cuáles son los Patrones? Asesinatos de Líderes Sociales en el Post Acuerdo. Bogotá: CINEP. 2018.

- CNMH (Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica). Con licencia para desplazar: Masacres y reconfiguración territorial en Tibú, Catatumbo. Bogotá: CNMH, 2015.

- CNMH (Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica). Catatumbo: Memorias de vida y dignidad. Bogotá: CNMH, 2018.

- Cuesta, Irina. Las Garantías de Seguridad: Una mirada desde lo local: Catatumbo. Bogotá: Fundación Ideas para la Paz, 2018.

- Daly, Sarah Zukerman. “The Dark Side of Power-Sharing: Middle Managers and Civil War Recurrence.” Comparative Politics 46, no. 3 (2014): 333–353. doi:10.5129/001041514810943027.

- Dirk, Berg-Schlosser, Gisèle De Meur, Benoît Rihoux, and Charles C. Ragin. “Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) as an Approach.” In Configurational Comparative Methods. Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) and Related Techniques, edited by B. Rihoux and C. C. Ragin, 1–18. Thousand Oaks: Sage, 2009.

- Duncan, Gustavo. Más que plata o plomo. El poder político del narcotráfico en Colombia y México. Bogotá: Debate, 2014.

- Eaton, Kent, and Juan Diego Prieto. “Subnational Authoritarianism and Democratization in Colombia: Divergent Paths in Cesar and Magdalena.” In Violence in Latin America and the Caribbean Subnational Structures, Institutions, and Clientelistic Networks, edited by Tina Hilgers and Laura MacDonald, 153–172. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017.

- Escobar, Elisabeth. “Entre la incertidumbre y el acomodo: reconfiguración del orden local y la vida rural durante el posacuerdo, por el accionar de las disidencias de las FARC-EP en el municipio de Suárez, Cauca.” M.A Thesis, Universidad Javeriana-Cali, 2021.

- Gallagher, Michael, and Paul Mitchell. “Appendix C.” In The Politics of Electoral Systems, edited by Michael Gallagher and Paul Mitchell, 607–620. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

- García, Miguel. “Sobre balas y votos: Violencia política y participación electoral en Colombia, 1990 – 1994.” In Entre la persistencia y el cambio. Reconfiguración del escenario partidista y electoral en Colombia, edited by Diana Hoyos, 84–117. Bogotá: Universidad del Rosario, 2007.

- Garzón, Juan Carlos, Andrés Cajiao, Juan Corredor García, and Paula Tobo. La Segunda Marquetalia: Disidentes, rearmados y un futuro incierto. Bogotá: Fundación Ideas para la Paz, 2021.

- Garzón, Juan Carlos, Irina Cuesta, and Lorena Zárate. El Catatumbo: El punto débil de la transformación territorial. Bogotá: Fundación Ideas para la Paz, 2020.

- Gibson, Edward L. Boundary Control: Subnational Authoritarianism in Federal Democracies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- González, Fernán, and Silvia Otero. “La presencia diferenciada del Estado: Un desafío a los conceptos de gobernabilidad y gobernanza.” In Gobernanza y conflicto en Colombia, edited by Claire Launay and Fernan Gonzalez, 28–36. Bogotá: CINEP, 2010.

- Gutiérrez Sanín, Francisco. “Fumigaciones, incumplimientos, coaliciones y resistencias.” Estudios Sociojurídicos 22, no. 2 (2020): 1–37.

- Gutiérrez Sanín, Francisco, Margarita Marín, Diana Machuca, Mónica Parada, and Howard Rojas. “Paz sin garantías: El asesinato de líderes de restitución y sustitución de cultivos de uso ilícito en Colombia.” Estudios Socio-jurídicos 22, no. 2 (2020): 361–418.

- Gutiérrez, D., and José Antonio. “Rebel Governance as State-Building? Discussing the FARC-EP’s Governance Practices in Southern Colombia.” Partecipazione e conflitto 15, no. 1 (2022): 17–36.

- Gutiérrez, D., José Antonio, and Frances Thomson. “Rebels-Turned-Narcos? The FARC-EP’s Political Involvement in Colombia’s Cocaine Economy.” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 44, no. 1 (2020): 1–26.

- Holmes, Jennifer S., and Viveca Pavon-Harr. “Violence after Peace.” In As War Ends: What Colombia Can Tell Us about the Sustainability of Peace and Transitional Justice, edited by James Meernik, H.R. Jacqueline, DeMeritt, and Mauricio Uribe-López, 134–160. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

- International Crisis Group. “Leaders under Fire: Defending Colombia’s Front Line of Peace.” ICG Latin America Report 82, 2020.

- Kaplan, Oliver. Resisting War: How Communities Protect Themselves. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017.

- Kasfir, Nelson, Georg Frerks, and Niels Terpstra. “Introduction: Armed Groups and Multi-layered Governance.” Civil Wars 19, no. 3 (2018): 257–278. doi:10.1080/13698249.2017.1419611.

- Kurtenbach, Sabine, and Angelika Rettberg. “Understanding the Relation between War Economies and post-war Crime.” Third World Thematics 3, no. 1 (2018): 1–8. doi:10.1080/23802014.2018.1457454.

- Middeldorp, Nick, and Philippe Le Billon. “Deadly Environmental Governance: Authoritarianism, Eco-populism, and the Repression of Environmental and Land Defenders.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 109, no. 2 (2019): 324–337. doi:10.1080/24694452.2018.1530586.

- Mounu, Prem, Andrés Rivera, Dario Romero, and Juan F. Vargas. “Selective Civilian Targeting: The Unintended Consequences of Partial Peace.” Unpublished Manuscript, 2020. DOI:10.2139/ssrn.3203065.

- Nussio, Enzo, and Kimberly Howe. “When Protection Collapses: Post-Demobilization Trajectories of Violence.” Terrorism and Political Violence 28, no. 5 (2016): 848–867. doi:10.1080/09546553.2014.955916.

- Osorio, Javier, Mohamed Mohamed, Viveca Pavon, and Susan Brewer-Osorio. “Mapping Violent Presence of Armed Actors in Colombia.” Advances of Cartography and GIScience of the International Cartographic Association 1, no. 16 (2019): 1–9. doi:10.5194/ica-adv-1-16-2019.

- Ragin, Charles C. Redesigning Social Inquiry: Fuzzy Sets and beyond. Chicago IL: University of Chicago Press, 2008.

- Robinson, J. A. “Colombia: Another 100 Years of Solitude?” Current History 112, no. 751 (2013): 43–48. doi:10.1525/curh.2013.112.751.43.

- Roessler, Philip G. “Donor-Induced Democratization and the Privatization of State Violence in Kenya and Rwanda.” Comparative Politics 37, no. 2 (2005): 207–225. doi:10.2307/20072883.

- Salazar, Salas, Luis Gabriel, Jonas Wolff, and Fabián Eduardo Camelo. “Towards Violent Peace? Territorial Dynamics of Violence in Tumaco (Colombia) before and after the Demobilisation of the FARC-EP.” Conflict, Security & Development 19, no. 5 (2019): 497–520. doi:10.1080/14678802.2019.1661594.

- Schneider, Carsten Q, and Claudius Wagemann. Set-theoretic Methods for the Social Sciences: A Guide to Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

- Staniland, Paul. “States, Insurgents, and Wartime Political Orders.” Perspectives on Politics 10, no. 2 (2012): 243–264. doi:10.1017/S1537592712000655.

- Steele, Abbey. Democracy and Displacement in Colombia’s Civil War. NY: Cornell University Press, 2017.

- Steenkamp, Christina. “In the Shadows of War and Peace: Making Sense of Violence after Peace Accords.” Conflict, Security & Development 11, no. 3 (2011): 357–383. doi:10.1080/14678802.2011.593813.

- Steven, Levitsky, and Lucan A. Way. Competitive Authoritarianism: Hybrid Regimes after the Cold War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Suhrke, Astri. “The Peace in Between.” In The Peace in Between. Post-war Violence and Peacebuilding, edited by Astri Suhrke and Mats Berdal, 1–24. New York: Routledge, 2013.

- UNHCHR. “Situation of Human Rights in Colombia. Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights.” Geneva: Human Rights Council ( Fortieth session), 2019.

- UNODC. “Colombia. Monitoreo de territorios afectados por cultivos ilícitos 2020.”, 2021. Accessed August 1, 2022. https://www.unodc.org/documents/crop-monitoring/Colombia/Colombia_Monitoreo_de_territorios_afectados_por_cultivos_ilicitos_2020.pdf.