ABSTRACT

The World Health Organization states that gender has implications for health across the course of a person’s life in terms of norms, roles and relations. It also has implications in rehabilitation. In this article, we argue the need of gender perspectives in the field of physiotherapy; gender matters and makes a difference in health and rehabilitation. We highlight a number of central areas where gender may be significant and give concrete examples of social gender aspects in physiotherapy practice and in diverse patient groups. We also discuss why it can be important to consider gender from an organizational perspective and how sociocultural norms and ideals relating to body, exercise and health are gendered. Further we present useful gender theories and conceptual frameworks. Finally, we outline future directions in terms of gender-sensitive intervention, physiotherapy education and a gendered application of the ICF model. We want to challenge physiotherapists and physiotherapy students to broaden knowledge and awareness of how gender may impact on physiotherapy, and how gender theory can serve as an analytical lens for a useful perspective on the development of clinical practice, education and research within physiotherapy.

Introduction

In this article, we demonstrate the need for a gender perspective in the field of physiotherapy. Gender matters and makes a difference in physiotherapy clinical practice, education and research (Öhman, Citation2001), as well as in a wider public health context (Öhman, Citation2008; World Health Organization, Citation2003). However, in both research and education, the core subject of physiotherapy is rooted in medical science and derived from positivism (Engelsrud, Citation2006; Nicholls, Citation2017; Nicholls and Gibson, Citation2010; Öhman, Citation2001; Thornquist, Citation2018). For this reason, the subject takes individual patient perspective with ontological inspiration from atomism (i.e. traditional biomedicine and reductionism) rather than a holistic perspective on humans, which incorporates social and gendered aspects of body and health (Sudmann, Citation2009). The view of humans as being both biological entities and social-relational beings in a social context is emphasized in different models of health, including the biopsychosocial model (Engel, Citation1977) and the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) (World Health Organization, Citation2008). Such holistic models contribute to our understanding of how health develops and constantly changes in relation to complex conditions. However, they do not have an explicit gender perspective (Stenberg, Citation2012). A gender perspective can contribute to illuminate the social power structures (Hammarström et al., Citation2014) that are relatively invisible in other more individualized health care models, such as notions of person-centered care.

A lack of gender theoretical knowledge has been identified within the field of physiotherapy. Gender theory may contribute to theoretical and methodological development in this respect, as there is limited physiotherapy research that incorporates gender theory, and physiotherapy practice is thought to be relatively ‘gender blind’ (Öhman, Citation2001). A promising trend can be seen toward more gender research within the field of physiotherapy and it should be encouraged in order to further accelerate the development of knowledge in this area.

Moreover, little attention is devoted in education to how rehabilitation in clinical settings and the progression of the novice physiotherapist’s professional role can benefit from gender perspectives (Öhman and Hägg, Citation1998). It has proven challenging to bring up gender issues in medical education due to institutional resistance to change, ambiguity in terms of which gender issues should be included, and the lack of practical implementation guidelines (Verdonk, Benschop, De Haes, and Lagro-Janssen, Citation2009). It would be preferable to integrate gender education in the regular curricula, which in turn would require commitment from both teachers and students (Macdonald and Nicholls, Citation2017; Rogg Korsvik, Citation2020; Verdonk, Benschop, De Haes, and Lagro-Janssen, Citation2009)

In this article, we understand gender as a social structure and not only as a personal identity. Gender is shaped by norms, expectations, and social contexts in processes of ‘doing gender’ (Connell, Citation2009, Citation2012), such as performed ‘femininity’ and ‘masculinity’ in a specific time and place (Connell, Citation2009, Citation2012; West and Zimmerman, Citation1987). We use the categories ‘men’ and ‘women,’ ‘boys’ and ‘girls’ but acknowledge that they are unstable and constructed categories that get their meaning within a normative heterosexual framework (Butler, 2006 ; Öhman, Eriksson, and Goicolea, Citation2015). We use ‘femininity’ and ‘masculinity’ when we refer to social constructions of gender and how gender is expressed by individuals in relation to those social norms and practices. Social constructions of gender may also relate to the gender identity (i.e. cis-gender, transgender, non-binary or gender fluid).

Our aim is to highlight some central areas where gender theoretical perspectives may be important for physiotherapy clinical practice, education and research. This theoretical paper is based mainly on empirical research within physiotherapy and/or by physiotherapists. Gender theory is a broad research area, and we will not provide a comprehensive picture of gender in physiotherapy. Rather we want to raise awareness and to inspire new reflections.

The authors of this article are gender researchers in the field of physiotherapy. We identified relevant studies on gender in physiotherapy, first through a reading of key authors who employ gender theory in their work; and secondly through a simple literature search, using the keywords: physiotherapy/physical therapy and gender theory/gender perspective (Pubmed, PEDro, CINAHL in title/abstract, September 2020). As presented below, the identified studies provide a general overview and empirical examples on gender in clinical practice; gendered organizational aspects; and gendered sociocultural norms and ideals. Further we shortly refer to how the included empirical examples use gender theory and conceptual frameworks. Finally, we outline some future directions and challenges of gender in physiotherapy.

Gendered areas relevant to physiotherapy

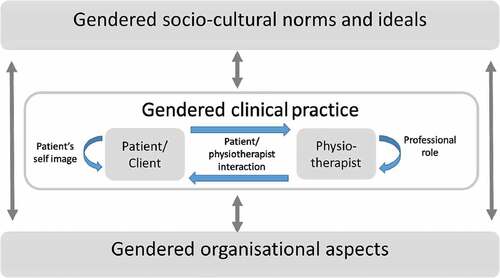

In the following section, we present three areas, where it is important to consider gender, and where we found empirical studies: 1) gender in clinical practice; 2) gendered organizational aspects; and 3) gendered sociocultural norms and ideals. We also discuss how gender in these areas may influence physiotherapy and give some suggestions of clinical implications along with a tentative model that may serve as a framework (). Although we are aware that physiotherapists do not always work with patients, the term patient is used throughout this text for simplicity and can indicate any type of client.

Gender in Clinical Practice

Below we illustrate how gender impacts on clinical practice with examples from existing research about the patient-physiotherapist interaction; patient self-image; and the professional role.

As gender is relational and created by social practices (Connell, Citation2009), also rehabilitation settings and physiotherapists’ clinical practice are influenced by gender. Risberg, Johansson, and Hamberg (Citation2009) developed a theoretical model of gender bias and describe how gendered stereotyped attitudes and preconceptions about gender lead to negative consequences or positive advantages for patients within the health care system . The concept of gender bias in health care and rehabilitation refers to (unequal) differences in treatment, which are not medically justified (Risberg, Johansson, and Hamberg, Citation2009).

There are some studies from physiotherapy settings problematizing the patient-physiotherapist interaction in diagnosis and chosen physiotherapy treatments. It can be expressed for example by taking differences between women and men for granted. Stenberg, Fjellman-Wiklund, and Ahlgren (Citation2014) demonstrated that there were gender-stereotyped differences in health care professionals’ messages to patients with neck and back pain. Women more often perceived the message of “be careful,” which was related to the notion of women being weak and fragile. Men were more often supported in messages saying that “heavy work leads to pain” even though many of the women studied also had physically strenuous work tasks. Men were given fewer suggestions about exercise as treatment, as they were perceived to be strong.

In multimodal pain rehabilitation, there are examples of gender bias and unequal referral to various interventions according to gender-stereotyped thinking among the professionals (Lehti, Fjellman-Wiklund, Stålnacke, and Wiklund, Citation2017; Stålnacke et al., Citation2015; Stenberg, Pietila Holmner, Stalnacke, and Enthoven, Citation2016; Wiklund, Fjellman-Wiklund, Stålnacke, and Lehti, Citation2016). The professionals, including physiotherapists, were for example more hesitant to have men participate in group rehabilitation (Stenberg, Pietila Holmner, Stalnacke, and Enthoven, Citation2016) as they perceived men as reluctant to talk about feelings and that a single man could feel excluded in a group of women. Professionals who included men in rehabilitation groups were mostly positive and thought that it was enriching for the patients to participate in mixed gender groups (Stenberg, Pietila Holmner, Stalnacke, and Enthoven, Citation2016). However, in a study based on physiotherapist data on patients’ consultations for neck and back pain, there were no differences between treatment given to women and to men (Stenberg and Ahlgren, Citation2010). Such differences have been seen among physicians’ patients (Hamberg, Risberg, Johansson, and Westman, Citation2002; Weisse, Sorum, Sanders, and Syat, Citation2001) and there is a need to further study this phenomenon in physiotherapy.

Another example of gender bias, as described by Risberg, Johansson, and Hamberg (Citation2009), is when professionals are over-looking social differences important to health. False assumptions that equity and justice are prevalent could influence the patient-physiotherapist interaction and lead to gender bias. One qualitative study showed that women who used electric wheelchairs felt that the wheelchairs had a masculine-coded design idiom and that the Center for Assistive Technology tended not to accept expressions of femininity (Stenberg, Henje, Levi, and Lindström, Citation2016). When the women asked for adjustments to their wheelchairs, they were not accommodated with reference to the offered chair being the standard.

Moreover, studies of the distribution of physiotherapeutic interventions among children with Cerebral Palsy indicated inequity, as interventions were not only associated with the child’s level of gross motor function but also with the child’s gender (Degerstedt, Wiklund, and Enberg, Citation2017); the county they were registered in (Degerstedt, Enberg, Keisu, and Björklund, Citation2020; Degerstedt, Wiklund, and Enberg, Citation2017), or their country of birth (Degerstedt, Enberg, Keisu, and Björklund, Citation2020).

In an Australian context, Ross and Setchell (Citation2019) found that people who identify as LGBTIQ+ experienced challenges when attending physiotherapy. In their study, the majority of the 114 participants reported experiences of physiotherapy interactions to include biased ‘assumptions’ about their sexuality or gender identity as well as discomfort related to physical proximity, touch, undressing or observations of their body. Participants’ experiences also included fear of discrimination, overt and implicit discrimination, as well as the physiotherapist’s lack of knowledge about transgender-specific health issues.

To our knowledge, there is no study on how patients construct and think about the physiotherapist’s gender, and how this influences the patient–physiotherapist interaction. There are indications that patients more often choose a physiotherapist of the same sex/gender (Stenberg and Ahlgren, Citation2010). A similar pattern has been seen when patients visit nurses and physicians (Bensing, Van Den Brink-Muinen, and De Bakker, Citation1993; Chur‐Hansen, Citation2002) and more studies in this area would be warranted.

Different gendered constructions could have an impact on patient self-image. This can be illustrated in how patients describe their problems and expectations when seeking care (Ahlgren and Hammarstrom, Citation2000; Elderkin-Thompson and Waitzkin, Citation1999). In a study of primary health care, those identified as men expected to receive help when seeking care for neck and back pain, whereas those identified as women did not want to be a nuisance and were afraid of not being taken seriously (Stenberg, Fjellman-Wiklund, and Ahlgren, Citation2012). Men more often viewed their pain as proof of hard labor or heavy exercise, while women more often were ashamed and blamed themselves for causing their pain problems by not doing ‘enough’ exercise. Women may have difficulties to identify with the role of ‘pain patient’ (Côté and Coutu, Citation2010; Werner, Isaksen, and Malterud, Citation2004) as doing so could lead to feelings of shame (Gustafsson, Ekholm, and Öhman, Citation2004; Stenberg, Fjellman-Wiklund, and Ahlgren, Citation2012). This reflects a more general gendered pattern where those identified as men tend to place blame outside of themselves and talk about objective facts as the reason for pain, compared to those who were identified as women, more often internalize feelings of guilt and seek causes for the pain within themselves (Ahlgren and Hammarstrom, Citation2000; Stenberg, Fjellman-Wiklund, and Ahlgren, Citation2012). These differing self-images may also reflect the historically rooted social constructions of men’s bodies as the ‘superior’ norm; and women’s bodies as ‘problematic,’ ‘deviation’ or ‘fault’ (Bordo, Citation2004).

Cultural norms about masculinity and femininity change over time and take different forms in different societies. It is a challenge for physiotherapists to develop a sensitivity to discover needs beyond gender stereotypes and categorical thinking. This became clear when researchers studied men’s experiences of rehabilitation for chronic pain (Ahlsen, Bondevik, Mengshoel, and Solbrække, Citation2014; Ahlsen, Mengshoel, and Solbrække, Citation2012a, Citation2012b).

Gendered patterns are not only seen in verbal communication but may also influence how women and men answer questionnaires in physiotherapy settings (Pohl et al., Citation2015; Stenberg, Lundquist, Fjellman-Wiklund, and Ahlgren, Citation2014). This will influence the assessment and the interaction between patient and physiotherapist.

In youth-oriented physiotherapy (Strömbäck and Wiklund, Citation2017), initial steps were taken toward a gender-sensitive stress-intervention model for young women in youth health services, where gender as a social construct and in context was the point of departure tied to a holistic view of body, movement and health (Strömbäck, Wiklund, Salander Renberg, and Malmgren-Olsson, Citation2016). The intervention model was based on content and forms that addressed and problematized young women’s social and gendered situations in real life; it combined gender-sensitive and participatory group discussions with physiotherapeutic methods such as body awareness and relaxation. A basic assumption put forward in that study is that increased knowledge of external gendered and societal pressures on a structural level will enhance a person’s ability to distance herself from self-blame, find strategies to resist pressures, and relinquish personal responsibility for the overall situation (Strömbäck, Wiklund, Salander Renberg, and Malmgren-Olsson, Citation2016). An important conclusion was that girls can support each other in a group and understand their situation from different perspectives (Strömbäck, Malmgren-Olsson, and Wiklund, Citation2013).

Gender also matters in the physiotherapist’s professional role, in terms of how physiotherapists shape their therapist or professional role in accordance with current gender norms (Dahle, Citation1990; Öhman and Hägg, Citation1998; Stenmar and Nordholm, Citation1994). This division of labor and division of tasks within a profession is gendered social practices, called production relations described by Connell (Citation2009). This means that the division of labor is structured from a gender perspective between groups and within a group, given different meanings and power.

As gender norms change, the therapist role will change. Furthermore, the physiotherapists’ choice of treatment appears to be gendered. A study of treatment for neck and back pain showed some differences between men and women physiotherapists (Stenberg and Ahlgren, Citation2010). Women physiotherapists used significantly more acupuncture and treatment for improved mental function, for example body awareness, whereas men physiotherapists used significantly more joint mobility treatment.

Importantly, in patient–physiotherapist interaction, gender constructs can interplay with perceptions about other social aspects such as socioeconomic status, level of education, ethnicity or age. In a study by Lehti, Fjellman-Wiklund, Stålnacke, and Wiklund (Citation2017) rehabilitation professionals, including physiotherapists, expressed that patients with higher educational levels (i.e. similar education level as themselves) were easier to interact with and rehabilitate; and a registry study in the context of pain rehabilitation confirmed that highly educated women patients were to a greater degree chosen for multimodal pain rehabilitation than women patients with lower levels of education (Stålnacke et al., Citation2015).

Gendered organizational aspects

So far, our empirical examples have primarily touched upon how social gender is created on the individual level and influences patient–physiotherapist interactions in clinical practice. However, for both professionals and patients, it is important to broaden the view to also consider gender constructs and hierarchies on an organizational level. There is, for example, a “gender regime” in health care with an overrepresentation of women professionals while the men professionals, as a group, have more power both at the organizational level and in high-status professions within the organization (Connell, Citation2009). This gender regime has an impact on the physiotherapist’s professional role and career paths. Three years after graduation, men and women have preferred different areas for their future careers (Enberg, Stenlund, Sundelin, and Öhman, Citation2007). The most popular areas of future work among men were sports medicine and occupational health, compared to health promotion and rehabilitation among women (Enberg, Stenlund, Sundelin, and Öhman, Citation2007). Gender constructs thus interact with professional norms and status and may differ between professions. Among recently graduated nurses, for example, a majority of both men and women preferred to have a future career in emergency care, while none of the recently graduated men physiotherapists wanted to work in the field of emergency care (Enberg, Stenlund, Sundelin, and Öhman, Citation2007). Historically, the physiotherapy profession has been organized on the basis of different gender regimes in different times (Ottosson, Citation2016). Such gender regimes in health care or in other working areas impact on patients and physiotherapist alike.

We will now turn to some research examples from an organizational perspective of how gender can affect patients’ working life in terms of body and health. Health-promoting factors in working life are important, such as a balance between demands and control and between effort and reward, as well as separation of work and leisure. Both women and men benefit from considering these factors (Vingård, Citation2015). However, in working life, there are evident gender norms and men are still seen as the norm (Swedish Work Environment Authority, Citation2013a). Many countries, including Sweden, have a gender-segregated labor market (World Economic Forum, Citation2020). This means that women more often have tasks that involve repetitive and monotonous movements while men work with heavy physical loads, thus leading to different physical risks for women and men (Swedish Work Environment Authority, Citation2013b). Tools, instruments and work places are often developed and designed with the man as norm and this can lead to a less favorable fit for women and consequently to higher frequency of musculoskeletal disorders and sick leave.

Threats and violence at work is also a gendered problem in various organizations (Swedish Work Environment Authority, Citation2011). The most vulnerable professions to threats and violence are those where you work with people: health and social care and social services (Swedish Work Environment Authority, Citation2011). Due to gender segregation, there are more women than men working in these professions, and they are thus more exposed to threats and violence. Threats and violence may come from people at work (e.g. work colleagues and managers) as well as from patients and clients (Swedish Work Environment Authority, Citation2011). In a study by Enberg, Stenlund, Sundelin, and Öhman (Citation2007), women also had a higher total amount of work due to the ‘double burden’ of paid work and unpaid work at home.

There are also statistical comparisons between men and women showing gendered patterns of sick leave, with more women than men being on sick leave, particularly due to mental and musculoskeletal disorders (Swedish National Insurance Agency, Citation2016). Many women are forced to end their working life due to mental and musculoskeletal disorders, and sick leave. Among people who are on sick leave, most have an employment in the health care and social services sector (Swedish National Insurance Agency, Citation2016) where the workforce consists predominantly of women. Professionals in this sector often perceive their psychosocial work environment as less favorable, which could be an additional explanation for sick-leave (Swedish National Insurance Agency, Citation2014). However, when women and men have similar working conditions, they develop symptoms of mental and stress-related exhaustion to the same degree (Vingård, Citation2015). For physiotherapists, these gendered patterns are important to take into account in clinical practice as well as in preventive work and health promotion. A dialogue-based workplace intervention coordinated by a physiotherapist could increase return to work, bridging gaps between involved actors (Strömbäck et al., Citation2020) and improve work capacity (Sennehed et al., Citation2018). A physiotherapist has specific knowledge about different diagnoses and could give advice on work adjustments according to individual needs (Eskilsson, Norlund, Lehti, and Wiklund, Citation2021).

Gendered sociocultural norms and ideals

When addressing contextual conditions that directly influence body and health, and indirectly influence physiotherapy and the patient-physiotherapist interaction, it is crucial to be aware of gendered socio-cultural norms and ideals. In physiotherapy, the ‘physical body’ is the main focus, and the view of the physical body as ‘a machine’ is a norm with strong historical roots in biomedicine (Nicholls, Citation2017; Nicholls and Gibson, Citation2010). However, from a social constructionist and gender theory perspective, the body is not only a ‘neutral’ physical entity but rather socially created in time and space (Lupton, Citation2012). As such, the body is tied to gendered ‘lived experience,’ as theorized in feminist phenomenological approaches (Groven and Engelsrud, Citation2010). Below, we provide some empirical examples of the ‘gendered body’ in a social context with relevance for physiotherapists.

One example, derived from research interviews and symptom measures with young Swedish women seeking help from youth health services and physiotherapists because of stress-related and musculoskeletal problems, demonstrates how social constructions of gender and femininity impacted the understanding their complex symptomatology, including pain, sleeping problems, tiredness, restlessness, anxiety and depressive mood – as well as their feelings of being of less value (Strömbäck, Wiklund, Salander Renberg, and Malmgren-Olsson, Citation2015; Wiklund, Bengs, Malmgren-Olsson, and Öhman, Citation2010; Wiklund, Öhman, Bengs, and Malmgren-Olsson, Citation2014). The young women experienced a ‘painful and collapsing body’ which caused them physical, emotional and existential suffering (Wiklund, Citation2010; Wiklund, Öhman, Bengs, and Malmgren-Olsson, Citation2014). These symptoms and experiences can be understood as part of their and others’ ‘doing’ of gender and femininity tied to gendered ideals of perfection and care, expressed as high responsibility-taking in social relationships and high achievements in multiple arenas of life such as school, working-life, relationships and appearance (Strömbäck, Formark, Wiklund, and Malmgren-Olsson, Citation2014; Strömbäck, Wiklund, Salander Renberg, and Malmgren-Olsson, Citation2015; Wiklund, Citation2010; Wiklund, Bengs, Malmgren-Olsson, and Öhman, Citation2010).

From a gender theory perspective, these research studies derived from physiotherapy settings problematize gendered views of women bodies as ‘problematic and weak’ (Strömbäck, Formark, Wiklund, and Malmgren-Olsson, Citation2014; Wiklund, Bengs, Malmgren-Olsson, and Öhman, Citation2010) while also being ‘competitive’ and ‘individualized,’ which is in line with theorization by gender theory and youth researchers who refer to historical and contemporary societal discourses. From a historical gender perspective, the body is seen as a ‘medium of culture’ in relation to the development of gender-related disorders such as ‘hysteria’ and ‘anorexia nervosa’ (Bordo (Citation2004). Youth researchers on the other hand, like Harris (Citation2004) and McRobbie (Citation2009, Citation2015), placed young contemporary women and their ‘problems’ in a wider social and cultural landscape of individualized femininity, ‘post-feminism’ and a ‘new competitive meritocracy’ which idealize individual ability and successful life trajectories. Linked to this is a strong focus on health and appearance as seen people’s accounts relating to body and health (Wiklund, Bengs, Malmgren-Olsson, and Öhman, Citation2010; Wiklund, Jonsson, Coe, and Wiklund, Citation2019), which can be referred to as an individualized ‘healthism’ discourse (Crawford, Citation1980, Citation2006). Such discourses, which define the body as ‘a project,’ involve a strong focus on ‘fitness,’ ‘wellness’ and ‘make-over’ with the healthy, slim, fit and perfect body as the norm (Walseth, Aartun, and Engelsrud, Citation2017; Wiklund, Bengs, Malmgren-Olsson, and Öhman, Citation2010; Wiklund, Jonsson, Coe, and Wiklund, Citation2019). Another example, from group-based physiotherapy treatment offered to women struggling with obesity, indicates that experiences of training were interwoven with general (gendered) experiences of being overweight. When exercising in a fitness gym they felt ashamed and uncomfortable, exposed to ‘the gaze of others,’ while they felt more comfortable and accepted when exercising together with persons in the same situation as theirs (Groven and Engelsrud, Citation2010).

Body, health and illness can thus be understood to be shaped by societal norms and ideals, and as such they are also linked to varying social status (Briones-Vozmediano, Citation2016; Groven and Engelsrud, Citation2010; Wiklund, Bengs, Malmgren-Olsson, and Öhman, Citation2010; Wiklund, Jonsson, Coe, and Wiklund, Citation2019). In Western contemporary societies, the controlled, civilized, healthy and able young masculine body tends to be a dominant body ideal (Lupton, Citation2012). From this perspective, women’s bodies have traditionally been portrayed as ‘frailer,’ ‘weaker,’ and more ‘disorderly’ and ‘prone’ to illness than men’s have (Lupton, Citation2012). In the perspective of health care rehabilitation, this may explain why certain illnesses and diagnoses that primarily affect women, such as nonspecific long-term pain, are ranked low in terms of social status and resource allocation (Album and Westin, Citation2008; Briones-Vozmediano, Citation2016; Lehti, Fjellman-Wiklund, Stålnacke, and Wiklund, Citation2017; Stenberg, Pietila Holmner, Stalnacke, and Enthoven, Citation2016). Studies indicate that care professionals hesitate to give men a low-status diagnosis (Ahlsen, Mengshoel, and Solbrække, Citation2012b) or offer men rehabilitation for such diagnoses (Lehti, Fjellman-Wiklund, Stålnacke, and Wiklund, Citation2017; Stenberg, Pietila Holmner, Stalnacke, and Enthoven, Citation2016). Thus, gender and body are produced in a given context and shaped by discourse. For physiotherapists, it is crucial to incorporate this kind of knowledge in theory and practice.

Clinical implications

To summarize, and as illustrated by the empirical examples, it is important for clinical physiotherapists to be aware of and reflect on physiotherapy in every day practice in relation to gender. Based on the three areas described above, we as physiotherapists can be aware of 1) What patients say and how they act; and how this can be influenced by gender; 2) How we interpret what we have seen and heard (from our patients) based on our own gender norms, assumptions and gender stereotypes; and how we act on the basis of those interpretations; 3) What gender and power regimes we can see and identify in organizations; and how they influence our work, working conditions as well as the patient’s reality and health; and 4) What gendered societal and cultural norms that influence us as physiotherapists and our patients.

In , we propose a tentative schematic framework that also can serve to guide physiotherapists when developing gender awareness and gender responsiveness in clinical practice, education, and research .

Gender theory and conceptual framework

Applied to the areas presented above, gender can be understood from multiple theortetical perspectives, including the social constructionist perspective adopted in several of the studies referred to in this article. In physiotherapy research on gender and its intersects, continuous theoretical development is crucial. This because illness, disease and disability are not only physical or physiological concerns but also social constructions of reality. Medical explanation models are used within a culture of norms, values and expectations that define the meaning of illness for people of that culture, and which set the criteria for something to be defined as illness and disease (Burr, Citation2003). New illnesses and diagnoses emerge and form a context-bound meaningful pattern (Johannisson, Citation2006). A social constructionist perspective has the potential to address and problematize how body, health, ability, diagnoses and treatment are shaped by perceptions, norms and status hierarchies in a certain time and place (Lupton, Citation2012). In the area of gendered sociocultural norms and ideals, these social constructionist perspectives are central.

Gender constructs can be understood as multidimensional since gender relations take place on different levels: within the individual level, in social relations between individuals, and on organizational and societal levels (Connell, Citation2009). According to Connell’s (Citation2009, Citation2012) relational theory, individuals are simultaneously ‘agents’ and ‘objects’ of gendered social practices. According to this view, gender is not a fixed state; instead, norms and expectations are constantly changing and take different forms in different cultures throughout history (Connell, Citation2009). The areas of gender in clinical practice and gendered organizational aspects highlight these aspects of gender as relational and shaped by social practice on individual and organizational levels.

In the area gendered organizational aspects, examples are given on how gender (in)equities in health are created in various social contexts and on different levels of society, such as in the family, in school, in higher education and working life (Hammarström et al., Citation2014). Gendered patterns of (un)employment and socioeconomic status also impact on a person’s health status over a life span (Annandale and Hunt, Citation2009; Strandh et al., Citation2013). Social determinants not only influence individual health and development throughout life but also access to health promoting societal resources such as health insurance and rehabilitation (Marmot, Citation2007; Stålnacke et al., Citation2015). In addition, humans are affected by different power structures that can intersect and reinforce each other. Gender, age, class, ethnicity, (dis)ability or sexuality can create unique intersections of benefits and disadvantages, which in the literature is defined as intersectionality (Crenshaw, Citation1989; Hammarström et al., Citation2014). Conflicting perspectives relating to gendered influences on pain management, access to physiotherapy and patient anatomy have been shown in the interaction between physiotherapists and people with pain from culturally and linguistically diverse communities (Yoshikawa, Brady, Perry, and Devan, Citation2020). Also social identities e.g. ethno culture, social class, migration status and gender can interact and create relative positions of disadvantage for patients with health care providers and within the health system (Brady, Veljanova, and Chipchase, Citation2019). It is of great importance that physiotherapists are aware of these different power structures in clinical practice and that more research will be conducted to highlight intersectionality within the field of physiotherapy.

In physiotherapy research, concepts such as gender, body, health, movement, and physical activity are rarely addressed as social and cultural constructs, although some important contributions have been exemplified above. There is a need to further reflect and study those concepts from a gender perspective and to take power hierarchies and inequity on a structural organizational or societal level into consideration. To date, health research on gender issues has primarely focused on statistical differences between girls/women and boys/men as binary categories (Ahlgren et al., Citation2016; Hammarström et al., Citation2014), and on body function at the physical/individual structural level according to ICF (World Health Organization, Citation2008).

It is a limitation that few studies have so far, examined and presented the participants’ gender identities. Therefore, when we refer to studies, we have chosen to report the results as the authors have described them. Future gender theoretical research within physiotherapy can develop non-binary, intersectional, and critical perspectives further.

Future directions and challenges of gender in physiotherapy

The empirically based examples above, and the gender theoretical framework have implications for the future development of gender perspectives in physiotherapy. In the following section, we outline three future directions where we believe gender matters: 1) Gender in physiotherapy education; 2) Gender-sensitive physiotherapy interventions; and 3) A more gender sensitive ICF model.

Gender in physiotherapy education

Our first suggestion for future development is the integration of gender in physiotherapy education: from basic training at graduate level to postgraduate level and doctoral education. The way physiotherapy students construct their own gender identity can have an impact on their education. Research shows that individuals, depending on gender can have different reasons for entering a physiotherapy program already beforehand. In a study by Öhman, Stenlund, and Dahlgren (Citation2001) among students, men were three times more likely to have chosen the physiotherapy education due to their interest in sports and physical activity compared to women. Men were also seven times more likely to envision being the owner of a private clinic compared to women students when asked about their future career. In a Norwegian study (Dahl-Michelsen, Citation2014), sportiness among physiotherapy students also seems to be an identifier of being a ‘proper’ physiotherapist, where the ‘hyper-sporty’ men were described as the most suitable for the profession, even if there were also ‘hyper-sporty’ women in the group.

When intersecting with other factors, such as belonging to a nonwhite minority group, gender may also influence students’ results in physiotherapy education (Hammond, Citation2009, Citation2013; Norris et al., Citation2018). A study by Hammond (Citation2009) indicated a trend toward men students performing poorer in clinical practice compared to women students, although this was not confirmed in a later study (Norris et al., Citation2018). However, Norris et al. (Citation2018) found that being a man impacted negatively on BSc award attainment. The results may be due to different gendered expectations and interpretations of the profession by students and/or teachers. As there are also indications that physiotherapy teachers may have different views on professional contributions related to the students’ gender, there is a risk of gender bias (Öhman and Hägg, Citation1998).

As creating gender is a constantly ongoing process, there may be cultural differences in terms of gender awareness and stereotyped thinking among medical students (Andersson et al., Citation2012). Also coming generations of physiotherapists may either challenge or change traditionally gendered and stereotyped norms or reproduce them. Dahl-Michelsen (Citation2015) found that physiotherapist students, independent of gender use curing and caring competencies in similar ways, although curing is still valued higher than caring. Men and women in training to become physiotherapists also reported similar gendered profiles and little gender bias in relation to pain expectations (Sivagurunathan et al., Citation2019). There is a future challenge in integrating gender knowledge in higher education syllabi (Rogg Korsvik, Citation2020; Verdonk, Benschop, De Haes, and Lagro-Janssen, Citation2009) which may influence the clinical practice and professional roles of future physiotherapists to be more gender-aware and gender-responsive. There is reason to consider how we can encourage physiotherapy students to incorporate critical analysis in the education and to reflect on how we can develop the role of the physiotherapist outside the stereotypical gender norms in the future (Dahl-Michelsen and Solbrække, Citation2014; Macdonald and Nicholls, Citation2017)

Gender-sensitive physiotherapy interventions

Our second suggestion for future directions is the development of gender awareness in the assessments and interventions of clinical physiotherapy practice. Gender-sensitive health care is defined as the act of recognizing and raising awareness of the health effects of gender differentials (Kuhlmann and Annandale, Citation2010; World Health Organization, Citation2003). Gender sensitivity among health professionals can be described as an awareness that affects both decisions and actions. Gender-sensitive health care aims to connect individual, organizational and societal levels (Kuhlmann and Annandale, Citation2010). So far, studies indicate that health care providers, including physiotherapists, may report a lack of training and experience needed for gender-sensitive approaches, and programs and ‘diversity training’ are therefore suggested to reduce gender-based inequalities and outcomes as well as gender bias and discrimination (Lindsay, Kolne, and Rezai, Citation2020; Ross and Setchell, Citation2019).

To our knowledge, gender-sensitive approaches and interventions are rarely developed and evaluated in clinical physiotherapy practice (Strömbäck, Malmgren-Olsson, and Wiklund, Citation2013). According to Ahlgren et al. (Citation2016) the awareness of how gender influences rehabilitation, treatment and interventions for patients with chronic pain appears to be low. For unknown reasons, the most common measures in rehabilitation research studies are biological and psychological in nature, whereas the social parameters are few. Few studies have investigated how to design gender-sensitive research to avoid gender bias, and there are limited evaluations and guidelines for how to design gender-sensitive interventions in various target groups and settings.

Some studies have found gendered differences in the outcome of rehabilitation; women with chronic pain benefit more from multimodal programs compared to men (Jensen et al., Citation2001; Pieh et al., Citation2012; Spinord et al., Citation2018). The same has been found in the outcome of cognitive behavior therapy for women suffering from burnout (Stenlund et al., Citation2009) but in that study, there were no differences between women and men who only practiced qigong.

In general, gender-sensitive approaches are described as ways to develop attractive interventions, adapted to the specific gendered needs and contemporary life situations of various groups (Kelly, Bobo, Avery, and Mclachlan, Citation2004; Kuhlmann and Annandale, Citation2010; Strömbäck, Wiklund, Salander Renberg, and Malmgren-Olsson, Citation2016). Strategies may include addressing constraints in the form of gendered relations or power imbalances in relationships, as well as gendered attitudes, norms and perceptions. One example of such a strategy is to create ‘separatist’ spaces for certain groups to reach specific goals, such as feminist programs for young women, which aim to encourage their strengths and resources, including social and relational competencies and to empower young women to seek group support (Kelly, Bobo, Avery, and Mclachlan, Citation2004; Strömbäck, Wiklund, Salander Renberg, and Malmgren-Olsson, Citation2016).

There is a need in future research to learn more about different subgroups and their social and gendered living conditions for example, in terms of age, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, sexuality and gender identity. Strengthening awareness of gender as a social construct and determinant of health can help to improve access to health care to tailor treatments to meet specific needs (Lindsay, Kolne, and Rezai, Citation2020; Lundberg, Citation2020). One step in this direction could be the development of gender-sensitive physiotherapeutic interventions to identify and to serve individual needs in a contextualized and gendered perspective (Lindsay, Kolne, and Rezai, Citation2020; Strömbäck, Wiklund, Salander Renberg, and Malmgren-Olsson, Citation2016).

A more gender sensitive ICF model

Our third and final direction and challenge for future development is the ‘gendering of the ICF model’ (World Health Organization, Citation2008). ICF is a commonly used and thus influential model in physiotherapy and rehabilitation, which aims to integrate biological, individual and social perspectives.

The ICF model is a potentially helpful tool for physiotherapists to highlight gender issues in clinical practice and in research (Scherer and Dicowden, Citation2008). The original ICF model included the domains of body function, body structure, activity and participation. The contextual factors were added in 2001, consisting of personal factors and environmental factors. Personal factors include personal background and life history for example sex, age, ethnicity, habits, coping, education, and occupation (World Health Organization, Citation2008). Environmental factors primarily include the physical, social and attitudinal contexts and environments that impact on the individual’s health and functioning (World Health Organization, Citation2008). In the ICF model, personal factors and environmental factors are connected and also impact on other domains. However, the ICF model could benefit from further development in terms of gender. Today gender is absent in the contextual factors in ICF. For example, in environmental factors there is a code for violent earthquakes (e230) but it is not clear how to code violence against women. The World Health Organization (Citation2008) having found that violence against women and girls occurs in every country and culture and is rooted in social and cultural attitudes and norms. The consequence is that 35% of the women worldwide have experienced either physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence or non-partner sexual violence in their lifetime (World Health Organization, Citation2017). Exposure to violence affects health to a very high degree and should be made visible in ICF.

Another problem in the current ICF is that both the model and the classifications are still focusing on an individual perspective; the impact of societal attitudes and social norms (codes in ICF environmental factors) has an inconspicuous place in ICF and its relationship with the ICF domains is vaguely formulated within the model. The model could thus be refined to also include social aspects of gender relating to body, health and participation in society.

Conclusion

In this article, we argue that gender matters in the field of physiotherapy. We aim to inspire our physiotherapist colleagues and physiotherapy students alike to broaden the knowledge base and awareness of how gender may impact physiotherapy, and how gender theory can serve as an analytical lens for useful perspectives on the development of clinical practice, education and research in physiotherapy. We consider that the tentative model () can serve as a useful framework for future reflections and discussions. We believe that reflections on gender and gender norms should be included in the physiotherapist–patient interaction to counteract gender bias in access to rehabilitation, assessment, and decisions relating to treatment; and we have pointed to some research examples on this. Physiotherapists need to be aware of how organizational gender regimes, gender norms, gendered social constructions and culture influence both physiotherapists and patients. More research is needed within the field of physiotherapy to highlight perspectives on intersectionality and other gender identities than the binary gender construct.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to Christina Ahlgren, Associate Professor, Senior Lecturer, Umeå University for her valuable comments on the manuscript, and to our colleagues in the research group Gender Working Life and Psychosocial Health (GAP), Umeå University, Sweden, for their valuable comments on the manuscript. Our research group is connected to Umeå Centre of Health Science (U-CHEC), Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden.

Disclosure Statement

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ahlgren C, Fjellman-Wiklund A, Hamberg K, Johansson E, Stålnacke B 2016 The meanings given to gender in studies on multimodal rehabilitation for patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain–a literature review. Disability and Rehabilitation 38:2255–2270.

- Ahlgren C, Hammarstrom A 2000 Back to work? Gendered experiences of rehabilitation. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 28:88–94.

- Ahlsen B, Bondevik H, Mengshoel AM, Solbrække KN 2014 (Un) doing gender in a rehabilitation context: A narrative analysis of gender and self in stories of chronic muscle pain. Disability and Rehabilitation 36(5):359–366. 10.3109/09638288.2013.793750

- Ahlsen B, Mengshoel AM, Solbrække KN 2012a Troubled bodies-troubled men: A narrative analysis of men’s stories of chronic muscle pain. Disability and Rehabilitation 34(21):1765–1773. 10.3109/09638288.2012.660601

- Ahlsen B, Mengshoel AM, Solbrække KN 2012b Shelter from the storm; Men with chronic pain and narratives from the rehabilitation clinic. Patient Education and Counseling 89(2):316–320. 10.1016/j.pec.2012.07.011

- Album D, Westin S 2008 Do diseases have a prestige hierarchy? A survey among physicians and medical students. Social Science & Medicine 66(1):182–188. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.07.003

- Andersson J, Verdonk P, Johansson E, Largo-Janssen T, Hamberg K 2012 Comparing gender awareness in Dutch and Swedish first-year medical students - Results from a questionnaire. BMC Medical Education 12(1):3. 10.1186/1472-6920-12-3

- Annandale E, Hunt K 2009 Gender Inequalities in Health, Buckingham:Open University Press.

- Bensing J, Van Den Brink-Muinen A, De Bakker D 1993 Gender differences in practice style: A Dutch study of general practitioners. Medical Care 31(3):219–229. 10.1097/00005650-199303000-00004

- Bordo S 2004 Unbearable weight: Feminism, western culture, and the body, Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Brady B, Veljanova I, Chipchase L 2019 The intersections of chronic noncancer pain: Culturally diverse perspectives on disease burden. Pain Medicine 20(3):434–445. 10.1093/pm/pny088

- Briones-Vozmediano E 2016 The social construction of fibromyalgia as a health problem from the perspective of policies, professionals, and patients. Global Health Action 10(1):1275191. 10.1080/16549716.2017.1275191

- Burr V 2003 Social constructionism, London:Routledge.

- Butler J 2006 Gender trouble: feminism and the subversion of identity, New York: Routledge.

- Chur‐Hansen A 2002 Preferences for female and male nurses: The role of age, gender and previous experience - Year 2000 compared with 1984. Journal of Advanced Nursing 37(2):192–198. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02079.x

- Connell R 2009 Gender in world perspective, Cambridge:Polity.

- Connell R 2012 Gender, health and theory: Conceptualizing the issue, in local and world perspective. Social Science & Medicine 74(11):1675–1683. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.06.006

- Côté D, Coutu MF 2010 A critical review of gender issues in understanding prolonged disability related to musculoskeletal pain: How are they relevant to rehabilitation? Disability and Rehabilitation 32(2):87–102. 10.3109/09638280903026572

- Crawford R 1980 Healthism and the medicalization of everyday life. International Journal of Health Services 10(3):365–388. 10.2190/3H2H-3XJN-3KAY-G9NY

- Crawford R 2006 Health as a meaningful social practice. Health 10(4):401–420. 10.1177/1363459306067310

- Crenshaw K 1989 Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum 1989:139–167.

- Dahle R 1990 Arbeidsdeling, makt, identitet: betydningen av kjønn i fysioterapiyrket [division of labor, powewr, identity: The importance of gender in the physiotherapy profession], Doctoral Dissertation, Trondheim: Universitetet i Trondhem, Institutt for Sosialt Arbeid.

- Dahl-Michelsen T 2014 Sportiness and masculinities among female and male physiotherapy students. Physiotherapy Theory Practice 30(5):329–337. 10.3109/09593985.2013.876692

- Dahl-Michelsen T 2015 Curing and caring competences in the skills training of physiotherapy students. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 31(1):8–16. 10.3109/09593985.2014.949946

- Dahl-Michelsen T, Solbrække KN 2014 When bodies matter: Significance of the body in gender constructions in physiotherapy education. Gender and Education 26(6):672–687. 10.1080/09540253.2014.946475

- Degerstedt F, Enberg B, Keisu BI, Björklund M 2020 Inequity in physiotherapeutic inter-ventions for children with Cerebral Palsy in Sweden - A national registry study. Acta Paediatrica 109(4):774–782. 10.1111/apa.14980

- Degerstedt F, Wiklund M, Enberg B 2017 Physiotherapeutic interventions and physical activity for children in Northern Sweden with cerebral palsy: A register study from equity and gender perspectives. Global Health Action 10(sup2):1272236. 10.1080/16549716.2017.1272236

- Elderkin-Thompson V, Waitzkin H 1999 Differences in clinical communication by gender. Journal of General Internal Medicine 14(2):112–121. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00296.x

- Enberg B, Stenlund H, Sundelin G, Öhman A 2007 Work satisfaction, career preferences and unpaid household work among recently graduated health‐care professionals - A gender perspective. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences 21(2):169–177. 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2007.00453.x

- Engel GL 1977 The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science 196(4286):129–136. 10.1126/science.847460

- Engelsrud G 2006 Hva er kropp [is body], Oslo:Universitetsforlag.

- Eskilsson T, Norlund S, Lehti A, Wiklund M 2021 Enhanced capacity to act: Managers’ perspectives when participating in a dialogue‑based workplace intervention for employee return to work. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation 31(2):263–274. 10.1007/s10926-020-09914-x

- Groven KS, Engelsrud G 2010 Dilemmas in the process of weight reduction: Exploring how women experience training as a means of losing weight. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being 5(2):5125. 10.3402/qhw.v5i2.5125

- Gustafsson M, Ekholm J, Öhman A 2004 From shame to respect: Musculoskeletal pain patients’ experience of a rehabilitation programme: A qualitative study. Journal of Rehabilitation and Medicine 36(3):97–103. 10.1080/16501970310018314

- Hamberg K, Risberg G, Johansson E, Westman G 2002 Gender bias in physicians’ management of neck pain: A study of the answers in a Swedish national examination. Journal of Womens Health and Gender-Based Medicine 11(7):653–666. 10.1089/152460902760360595

- Hammarström A, Johansson K, Annandale E, Ahlgren C, Aléx L, Christianson M, Elwér S, Eriksson C, Fjellman-Wiklund A, Gilenstam K, et al. 2014 Central gender theoretical concepts in health research: The state of the art. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 68(2):185–190. 10.1136/jech-2013-202572

- Öhman A, Hägg K 1998 Attitudes of novice physiotherapists to their professional role: A gender perspective. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 14(1):23–32. 10.3109/09593989809070041

- Öhman A, Stenlund H, Dahlgren L 2001 Career choice, professional preferences and gender? The case of Swedish physiotherapy students. Advances in Physiotherapy 3(3):94–107. 10.1080/140381901750475348

- Öhman A 2001 Profession on the move: changing conditions and gendered development in physiotherapy, Doctoral Dissertation, Umeå: Umeå University.

- Öhman A 2008 Global public health and gender theory: The need for integration. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 36(5):449–451. 10.1177/1403494808094242

- Öhman A, Eriksson M, Goicolea I 2015 Gender and health - Aspects of importance for understanding health and illness in the world. Global Health Action 8(1):26908. 10.3402/gha.v8.26908

- Hammond JA 2009 Assessment of clinical components of physiotherapy undergraduate education: Are there any issues with gender? Physiotherapy 95(4):266–272. 10.1016/j.physio.2009.06.003

- Hammond JA 2013 Doing gender in physiotherapy education: a critical pedagogic approach to understanding how students construct gender identities in an undergraduate physiotherapy programme in the United Kingdom, Doctoral Dissertation:PQDT - UK and Ireland.

- Harris A 2004 Future girl: young women in the twenty-first century, London: Routledge.

- Jensen IB, Bergström G, Ljungquist T, Bodin L, Nygren ÅL 2001 A randomized controlled component analysis of a behavioral medicine rehabilitation program for chronic spinal pain: Are the effects dependent on gender? Pain 91(1):65–78. 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00420-6

- Johannisson K 2006 Modern fatigue: A historical perspective Arnetz BB, Ekman R,Eds Stress in health and disease, 1–19. Weinheim: Wiley.

- Kelly PJ, Bobo T, Avery S, Mclachlan K 2004 Feminist perspectives and practice with young women. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing 27(2):121–133. 10.1080/01460860490451831

- Kuhlmann E, Annandale E 2010 The palgrave handbook of gender and healthcare, Basingstoke:Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lehti A, Fjellman-Wiklund A, Stålnacke HA, Wiklund M 2017 Walking down ‘Via Dolorosa’ from primary health care to the specialty pain clinic - Patient and professional perceptions of inequity in rehabilitation of chronic pain. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences 31(1):45–53. 10.1111/scs.12312

- Lindsay S, Kolne K, Rezai M 2020 Challenges with providing gender-sensitive care: Exploring experiences within pediatric rehabilitation hospital. Disability and Rehabilitation Online ahead of print. 1–9. 10.1080/09638288.2020.1781939

- Lundberg V 2020 Children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: Health-related quality of life and participation in healthcare encounters, Doctoral Dissertation, Umeå: Umeå University.

- Lupton D 2012 Medicine as culture: Illness, disease and the body, London:Sage.

- Macdonald H, Nicholls DA 2017 Teaching physiotherapy students to “be content with a body that refuses to hold still.” Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 33(4):303–315. 10.1080/09593985.2017.1302027

- Marmot M 2007 Achieving health equity: From root causes to fair outcomes. Lancet 370(9593):1153–1163. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61385-3

- McRobbie A 2009 The aftermath of feminism: Gender, culture and social change, London:SAGE.

- McRobbie A 2015 Feminism, femininity and the perfect, London:Sage.

- Nicholls DA 2017 The end of physiotherapy, New York:Routledge.

- Nicholls DA, Gibson BE 2010 The body and physiotherapy. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 26(8):497–509. 10.3109/09593981003710316

- Norris M, Hammond JA, Williams A, Grant R, Naylor S, Rozario C 2018 Individual student characteristics and attainment in pre registration physiotherapy: A retrospective multi-site cohort study. Physiotherapy 104(4):446–452. 10.1016/j.physio.2017.10.006

- Ottosson A 2016 Androphobia, demasculinization, and professional conflicts: The herstories of the physical therapy profession deconstructed. Social Science History 40(3):433–461. 10.1017/ssh.2016.13

- Pieh C, Altmeppen J, Neumeier S, Loew T, Angerer M, Lahmann C 2012 Gender differences in outcomes of a multimodal pain management program. Pain 153(1):197–202. 10.1016/j.pain.2011.10.016

- Pohl P, Ahlgren C, Nordin E, Lundquist A, Lundin-Olsson L 2015 Gender perspective on fear of falling using the classification of functioning as the model. Disability and Rehabilitation 37(3):214–222. 10.3109/09638288.2014.914584

- Risberg G, Johansson EE, Hamberg K 2009 A theoretical model for analysing gender bias in medicine. Internal Journal for Equity in Health 8(1):28. 10.1186/1475-9276-8-28

- Rogg Korsvik T 2020 Kjønn og kvinnehelse i helseprofesjonsutdanninger – en kartlegging av læringsmål om kjønn og kvinnehelse i utdanningene medisin, sykepleie, psykologi, vernepleie og fysioterapier [gender and women’s health in health professional education - A survey of learning objectives on gender and women’s health in the education programmes of medicine, nursing, psychology, social care, and physiotherapy]. Kilden kjønnsforskning.no Lysaker Norway http://kjonnsforskning.no/sites/default/files/rapport_kilden_kjonn_og_kvinnehelse_i_helseprofesjonsutdanninger_2020.pdf

- Ross MH, Setchell J 2019 People who identify as LGBTIQ+ can experience assuptions, discomfort, some discrimination, and lack of knowledge while attending physiotherapy. Journal of Physiotherapy 63(2):99–105. 10.1016/j.jphys.2019.02.002

- Scherer MJ, Dicowden MA 2008 Organizing future research and intervention efforts on the impact and effects of gender differences on disability and rehabilitation: The usefulness of the international classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF). Disability and Rehabilitation 30(3):161–165. 10.1080/09638280701532292

- Sennehed CP, Holmberg S, Axen I, Stigmar K, Forsbrand M, Petersson IF, Grahn B 2018 Early workplace dialogue in physiotherapy practice improved work ability at 1-year follow-up-WorkUp, a randomised controlled trial in primary care. Pain 159(8):1456–1464. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001216

- Sivagurunathan M, MacDermid J, Chuang JC, Kaplan A, Lupton S, McDermid D 2019 Exploring the role of gender and gendered pain expectation in physiotherapy students. Canadian Journal of Pain 3(1):128–136. 10.1080/24740527.2019.1625705

- Spinord L, Kassberg AC, Stenberg G, Lundqvist R, Stålnacke BM 2018 Comparison of two multimodal pain rehabilitation programs, in relation to sex and age. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine 50(7):619–628. 10.2340/16501977-2352

- Stålnacke BM, Haukenes I, Lehti A, Fjellman-Wiklund A, Wiklund M, Hammarström A 2015 Is there a gender bias in recommendations for further rehabilitation in primary care of patients with chronic pain after an interdisciplinary team assessment? Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine 47(4):365–371. 10.2340/16501977-1936

- Stenberg G 2012 Genusperspektiv på rehabilitering för patienter med rygg-och nackbesvär i primärvård, [A Gender Perspective on Physiotherapy Treatment in Patients with Neck and Back Pain]. Doctoral Dissertation, Umeå: Umeå University.

- Stenberg G, Ahlgren C 2010 A gender perspective on physiotherapy treatment in patients with neck and back pain. Advances in Physiotherapy 12(1):35–41. 10.3109/14038190903174270

- Stenberg G, Fjellman-Wiklund A, Ahlgren C 2012 “Getting confirmation”: Gender in expectations and experiences of healthcare for neck or back patients. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine 44(2):163–171. 10.2340/16501977-0912

- Stenberg G, Fjellman-Wiklund A, Ahlgren C 2014 “I am afraid to make the damage worse” - Fear of engaging in physical activity among patients with neck or back pain - A gender perspective. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences 28(1):146–154. 10.1111/scs.12043

- Stenberg G, Henje C, Levi R, Lindström M 2016 Living with an electric wheelchair - The user perspective. Disability and Rehabilitation. Assistive Technology 11:385–394.

- Stenberg G, Lundquist A, Fjellman-Wiklund A, Ahlgren C 2014 Patterns of reported problems in women and men with back and neck pain: Similarities and differences. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine 46:668–675.

- Stenberg G, Pietila Holmner E, Stalnacke BM, Enthoven P 2016 Healthcare professional experiences with patients who participate in multimodal pain rehabilitation in primary care - A qualitative study. Disability and Rehabilitation 38(21):2085–2094. 10.3109/09638288.2015.1114156

- Stenlund T, Ahlgren C, Lindahl B, Burell G, Steinholtz K, Edlund C, Nilsson L, Knutsson A, Slunga Birgander L 2009 Cognitively oriented behavioral rehabilitation in combination with Qigong for patients on long-term sick leave because of burnout: REST - A randomized clinical trial. Internal Journal of Behavioral Medicine 16:294.

- Stenmar L, Nordholm L 1994 Swedish physical therapists’ beliefs on what makes therapy work. Physical Therapy 74(11):1034–1039. 10.1093/ptj/74.11.1034

- Strandh M, Hammarström A, Nilsson K, Nordenmark M, Russel H 2013 Unemployment, gender and mental health: The role of the gender regime. Sociology of Health & Illness 35(5):649–665. 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2012.01517.x

- Strömbäck M, Fjellman-Wiklund A, Keisu S, Sturesson M, Eskilsson T 2020 Restoring confidence in return to work: A qualitative study of the experiences of persons with exhaustion disorder after a dialogue-based workplace intervention. PloS One 15(7):e0234897. 10.1371/journal.pone.0234897

- Strömbäck M, Formark B, Wiklund M, Malmgren-Olsson E-B 2014 The corporeality of living stressful femininity: A gender–theoretical analysis of young Swedish women’s stress experiences. Young 22(3):271–289. 10.1177/0973174114533464

- Strömbäck M, Malmgren-Olsson E-B, Wiklund M 2013 ‘Girls need to strengthen each other as a group’: Experiences from a gender-sensitive stress management intervention by youth-friendly Swedish health services - A qualitative study. BMC Public Health 13(1):907. 10.1186/1471-2458-13-907

- Strömbäck M, Wiklund M 2017 Creating space for youth in Physiotherapy: Aspects related to gender and embodiment. In Probst M, Helvik Skjaerven L (Eds) Physiotherapy in mental health and psychiatry: A scientific and clinical based approach, pp. 290–298. Edinburgh:Elsevier.

- Strömbäck M, Wiklund M, Salander Renberg E Malmgren-Olsson EB 2016 Gender-sensitive and youth-friendly physiotherapy: Steps toward a stress management intervention for girls and young women. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 32:20–33.

- Strömbäck M, Wiklund M, Salander Renberg E, Malmgren-Olsson EB 2015 Complex symptomatology among young women who present with stress-related problems. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences 29:234–247.

- Sudmann TT 2009 (En) gendering body politics. physiotherapy as a window on health and illness, Doctoral dissertation, Bergen: University of Bergen.

- Swedish National Insurance Agency 2014 Sjukfrånvaro i psykiska diagnoser - en studie av sveriges befolkning 16–64 [absence due to illness in mental diagnoses a study of sweden’s population 16–64 years] försäkringskassan. Stockholm Sweden. http://www.forskasverige.se/wp-content/uploads/Sjukfranvaro-Psykiska-Diagnoser-2014.pdf

- Swedish National Insurance Agency 2016 Sjukskrivning för reaktioner på svår stress ökar mest. korta analyser [sick leave for reactions to severe stress increases most. short analyzes]. Försäkringskassan. Stockholm, Sweden https://www.forsakringskassan.se/wps/wcm/connect/41903408-e87d-4e5e-8f7f-90275dafe6ad/korta_analyser_2016_2.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CVID=

- Swedish Work Environment Authority 2011 Våld och genus i arbetslivet. kunskapsöversikt. [Violence and Gender in Working Life. Systematic Review]. Stockholm, Sweden. https://www.av.se/globalassets/filer/publikationer/kunskapssammanstallningar/vald-och-genus-i-arbetslivet-kunskapssammanstallningar-rap-2011-3.pdf

- Swedish Work Environment Authority 2013a Under luppen - genusperspektiv på arbetsmiljö och arbetsorganisation. [Under the Loupe - Gender Perspective on Work Environment and Work Organization]. Stockholm, Sweden. https://www.av.se/globalassets/filer/publikationer/kunskapssammanstallningar/under-luppen-genusperspektiv-pa-arbetsmiljo-och-arbetsorganisation-kunskapssammanstallningar-rap-2013-1.pdf

- Swedish Work Environment Authority 2013b Belastning, genus och hälsa i arbetslivet. [Stress, Gender and Health in Working Life]. Stockholm, Sweden. https://www.av.se/globalassets/filer/publikationer/kunskapssammanstallningar/belastning-genus-och-halsa-i-arbetslivet-kunskapssammanstallningar-rap-2013-9.pdf

- Thornquist E 2018 Vitenskapsfilosofi og vitenskapsteori: for helsefag [philosophy of science and theory of science for health sciences], Bergen:Fagbokforlaget.

- Verdonk P, Benschop YW, De Haes HC, Lagro-Janssen TL 2009 From gender bias to gender awareness in medical education. Advances in Health Sciences Education 14(1):135–152. 10.1007/s10459-008-9100-z

- Vingård E 2015 En kunskapsöversikt: psykisk ohälsa, arbetsliv och sjukfrånvaro [a know-ledge overview: mental illness working life and sick leave], Stockholm: Research Council for Health Working Life and Welfare

- Walseth K, Aartun I, Engelsrud G 2017 Girls’ bodily activities in physical education - How current fitness and sport discourses influence girls’ identity construction. Sport, Education and Society 22(4):442–459. 10.1080/13573322.2015.1050370

- Weisse C, Sorum P, Sanders K, Syat B 2001 Do gender and race affect decisions about pain management? Journal of General Internal Medicine 16(4):211–217. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016004211.x

- Werner A, Isaksen L, Malterud K 2004 ‘I am not the kind of woman who complains of everything’: IIllness stories on self and shame in women with chronic pain. Social Science & Medicine 59(5):1035–1045. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.12.001

- West C, Zimmerman DH 1987 Doing gender. Gender and Society 1(2):125–151. 10.1177/0891243287001002002

- Wiklund E, Jonsson E, Coe AB, Wiklund M 2019 ‘Strong is the new skinny’: Navigating fitness hype among teenagers in northern Sweden. Sport, Education and Society 24(5):441–454. 10.1080/13573322.2017.1402758

- Wiklund M 2010 Close to the edge: Discursive, gendered and embodied stress in modern youth, Doctoral Dissertation, Umeå: Umeå University.

- Wiklund M, Bengs C, Malmgren-Olsson EB, Öhman A 2010 Young women facing multiple and intersecting stressors of modernity, gender orders and youth. Social Science & Medicine 71(9):1567–1575. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.08.004

- Wiklund M, Fjellman-Wiklund A, Stålnacke HA, Lehti A 2016 Access to rehabilitation: Patient perceptions of inequalities in access to specialty pain rehabilitation from a gender and intersectional perspective Global Health Action, 9:1 31542

- Wiklund M, Öhman A, Bengs C, Malmgren-Olsson EB 2014 Living close to the edge: Embodied dimensions of distress during emerging adulthood. SAGE Open 2014:1–17.

- World Economic Forum 2020 Global gender gap, World Economic Forum:Geneva, Switzerland. http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2020.pdf

- World Health Organization 2003 “En-gendering” the millennium development goals (MDGs) on health, Department of Gender and Women’s Health World Health Organization. Organization.Geneva: WHO

- World Health Organization 2008 International classification of functioning, disability and health, Geneva: WHO.

- World Health Organization 2017 Violence against women. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women.

- Yoshikawa K, Brady B, Perry MA, Devan H 2020 Sociocultural factors influencing physio-therapy management in culturally and linguistically diverse people with persistent pain: A scoping review. Physiotherapy 107:292–305. 10.1016/j.physio.2019.08.002