ABSTRACT

Aims

Information on standards including structure- and process-based metrics and how exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation (EBCR) is delivered in relation to guidelines is lacking. The aims of the study were to evaluate standards and adherence to guidelines at Swedish CR centers and to conduct a cost analysis of the physiotherapy-related activities of EBCR.

Methods and Results

EBCR standards at all 78 CR centers in Sweden in 2016 were surveyed. The questions were based on guideline-recommended core components of EBCR for patients after a myocardial infarction (MI). The cost analysis included the identification, quantification, and valuation of EBCR-related cost items. Patients were offered a pre-discharge consultation with a physiotherapist at n = 61, 78% of the centers. A pre-exercise screening visit was routinely offered at n = 64, 82% of the centers, at which a test of aerobic capacity was offered in n = 58, 91% of cases, most often as a cycle ergometer exercise test n = 55, 86%. A post-exercise assessment was offered at n = 44, 56% of the centers, with a functional test performed at n = 30, 68%. Almost all the centers n = 76, 97% offered supervised EBCR programs. The total cost of delivering physiotherapy-related activities of EBCR according to guidelines was approximately 437 euro (4,371 SEK) per patient. Delivering EBCR to one MI patient required 11.25 hours of physiotherapy time.

Conclusion

While the overall quality of EBCR programs in Sweden is high, there are several areas of potential improvement to reach the recommended European standards across all centers. To improve the quality of EBCR, further compliance with guidelines is warranted.

Introduction

Meta-analyses confirm that exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation (EBCR) (i.e. supervised and individually prescribed exercise) as part of comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation (CR) is highly effective after a myocardial infarction (MI) and reduces risks of hospital readmissions, cardiac mortality, and recurrent MI (Dibben et al., Citation2021). EBCR also improves aerobic capacity by 10–20% (Sandercock, Hurtado, and Cardoso, Citation2013) and has positive effects on several modifiable cardiovascular risk factors (Lawler, Filion, and Eisenberg, Citation2011) and on psychological well-being (Verschueren et al., Citation2018). CR is considered cost-effective especially with exercise as a component (Shields et al., Citation2018). Consequently, participation in EBCR has received the highest class of recommendation and level of evidence in guidelines from the: European Society of Cardiology (Pelliccia et al., Citation2021; Visseren et al., Citation2021); American Heart Association (Balady et al., Citation2007); and in guidelines from the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare (Citation2018). CR is widely available in Sweden and program density is high in global comparison, or one program per 0.1 million inhabitants (Turk-Adawi, Sarrafzadegan, and Grace, Citation2014). Despite strong evidence-based benefits of EBCR there are still large variations regarding standards, uptake, and adherence across countries, healthcare regions, and hospitals leading to health inequalities and potentially severe consequences for patients and populations (Jernberg, Boberg, and Bäck, Citation2020; Kotseva et al., Citation2019). Moreover, a clear understanding of the resources required to deliver optimal EBCR is currently lacking. Reporting the true costs required for providing EBCR is important in order to determine the amount of resources needed to deliver evidence-based care. In turn, the cost information supports the planning, budgeting, and the allocation of sufficient resources for the implementation of the EBCR program in a sustainable manner.

The European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC) has recently defined the minimal and optimal standards for CR to ensure that patients receive evidence-based, safe and cost-effective CR (Abreu et al., Citation2020). In Sweden, the large quality registry, the Swedish Web-system for Enhancement and Development of Evidence-Based Care in Heart Disease Evaluated According to Recommended Therapies (SWEDEHEART) continuously records and provides information on the quality and content of patient care, treatments, and outcomes after MI over time. The SWEDEHEART cardiac rehabilitation (CR) registry is the part of SWEDEHEART that provides continuous information on secondary prevention including EBCR (Bäck et al., Citation2021). According to the SWEDEHEART registry the proportion of patients after an MI attending a comprehensive CR in 2019 was 83% (range 42–98%), while participation in an EBCR program was 31% (range 4–90%) with only 19% (range 0–72%) attending the recommended exercise program for three months (Jernberg, Boberg, and Bäck, Citation2020).

However, information on the standards and process of EBCR program delivery is not available in SWEDEHEART and has not previously been reported. Consequently, the reasons for the variation in treatment goal attainment are largely unknown. Moreover, information on the mode of EBCR delivery in Sweden, the associated costs and the extent to which CR centers adhere to European standards and guidelines is lacking. Increasing this knowledge is important to be able to guide future quality improvement and implementation projects to increase goal fulfillment evidence-based care. The aims of this study were to: 1) evaluate the EBCR program standards and adherence to guidelines at Swedish CR centers; and 2) conduct a cost analysis of delivering the physiotherapy-related activities of EBCR.

Methods

This is a sub-study from the national cross-sectional survey-based Perfect-CR study. A manuscript containing descriptive data has previously been published (Ogmundsdottir Michelsen et al., Citation2020). The cost analysis employed standard methods of assessing the resources of the EBCR program from a societal perspective, including the identification, quantification, and valuation of resources (Drummond, Citation2015).

Data collection

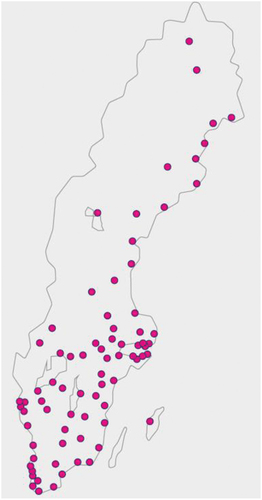

A questionnaire was sent out in November 2016 (pre-COVID-19 pandemic) to all 78 CR centers in Sweden reporting to the SWEDEHEART-CR registry (Ogmundsdottir Michelsen et al., Citation2020). The geographic location of the Swedish CR-centers is shown in . There were no exclusion criteria. Non-responders received a reminder via e-mail on two occasions. The remaining non-responders were contacted by telephone by a research nurse who assisted in the event of technical problems. An online survey system (SurveyMonkey Inc., Palo Alto, California, USA) was used to register the answers. The Perfect-CR study was approved by the ethics committee at Lund University (2336–001).

Perfect-CR questionnaire

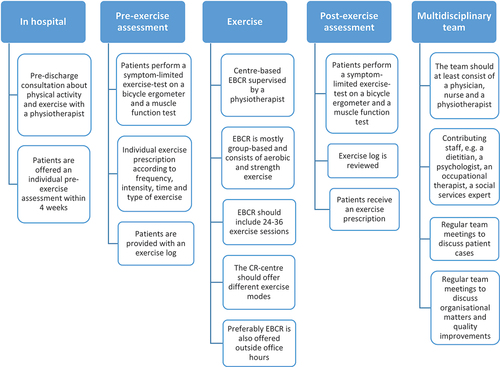

The Perfect-CR questionnaire contained 120 questions, designed by a research team consisting of six cardiologists, two nurses, and one physiotherapist, all with extensive clinical experience in CR. The primary aim of the questionnaire was to assess CR program characteristics and performance in accordance with Swedish and European guidelines on secondary prevention (Piepoli et al., Citation2014). The questionnaire covered every aspect of a comprehensive CR program. The questionnaire included structure-based metrics including human and infrastructure resources and process-based metrics (i.e. core components of CR delivery). Most of the questions were objective (i.e. “Do you have a program director at the CR center?” and “Do you offer an individual assessment with a physiotherapist to patients post discharge?”). For this study, questions specifically related to EBCR were used/analyzed. The European standards of EBCR are summarized in (Abreu et al., Citation2020; Piepoli et al., Citation2014).

To facilitate analyses of answers, the questionnaire mainly consisted of grading scales and multiple-choice questions with a fixed list of answers. In some cases, the respondents were able to write a free-text answer when the given answers were not applicable. For grading scale questions, the respondents were asked to agree or disagree on a scale from 1 (completely disagree) to 6 (completely agree). For this study, answering 1–2 was classified as “disagree” and answering 5–6 as “agree.”

Before distributing the questionnaire, a pilot test was performed at two centers. To test face validity, experts in terms of experienced nurses and physiotherapists at the centers were asked to provide feedback on the questionnaire to address that the items measure what they intend to do. They also gave feedback if the questionnaire seemed to have all the needed questions for the purpose of the study and they checked the time required to complete the questionnaire. The comments from the experts were discussed in the research team and based on their feedback some questions were clarified or revised.

Cost analysis

The cost analysis to determine resource requirements for providing EBCR was made in three steps, comprising the identification, quantification, and valuation of the main physiotherapy-related cost items. The items were defined in accordance with EBCR according to the guidelines in the Swedish healthcare system (Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare, Citation2018) and included the following items: individual patient treatment (i.e. in-hospital, pre-exercise assessment, post-exercise assessment, current patient work, consultation with other professions, and team meetings), group-based treatment activity, and overheads.

To identify and quantify the various resources, a questionnaire was administered to a sample of centers that participated in the Perfect-CR study (n = 18). The centers were sampled to provide a balanced representation of the type of hospital (i.e. university hospital, county hospital, and district hospital), the size of the center, and the geographical location. The questionnaire was designed to capture the main cost items as defined above. Costs were categorized into subcategories of: physiotherapy contacts/visits; administration; and center-based exercise sessions. Lastly, after systematically identifying and quantifying all cost items a valuation of resources was conducted. Specifically, professionals’ gross hourly wage rates were used to value the time costs of providers. We used the average salary for physiotherapists in Sweden in 2020, which was 3,350 euros (33,500 SEK), and added a social fee (46.15%). In line with common practice (Steen Carlsson et al., Citation2004) fixed costs (including facilities) were estimated at 10% of the total direct costs.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were applied using frequencies, proportions (%), means and median values, standard deviations (SDs), and quartiles (q1, q3) or ranges (min-max), as appropriate. The SPSS statistical software package, version 27 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA), was used to analyze data from the Perfect-CR questionnaire. MS Excel was used for the cost analysis.

Results

The questionnaire was completed by all 78 centers invited to participate in the study. At most centers (n = 69, 88%) two or more professionals (nurses, physiotherapists, and/or physicians) answered the questionnaire. Physiotherapists were involved in answering the questionnaire at n = 62 (80%) of the centers ().

Table 1. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation program characteristics of the 78 centers surveyed.

Physiotherapy in hospital

At n = 61, 78% of the centers, patients were routinely offered a pre-discharge consultation with a physiotherapist to discuss physical activity, exercise, and participation in EBCR.

Pre-Exercise assessment

An individual visit to a physiotherapist in an out-patient setting post-discharge (i.e. a pre-exercise assessment visit) was routinely offered at n = 64 (82%) of the centers. Three percent (n = 2) reported offering a pre-exercise assessment but not routinely, while n = 9 (12%) reported not offering any routine pre-exercise assessment. Three centers (4%) had missing data.

Of the 64 centers which reported routinely offering a pre-exercise assessment visit, n = 63 (98%) specified the average timing of the visit. At n = 15/63 (23%) the visit was scheduled ≤2 weeks from discharge (optimal standard), while an additional n = 39/63 (61%) reported scheduling the visit between two and four weeks from discharge, adding up to a total of 86% meeting the minimal standard of ≤4 weeks. At nine centers (14%) the average waiting time was longer than four weeks.

Of the 64 centers routinely offering a pre-exercise assessment visit, n = 55 (86%) reported conducting a cycle ergometer exercise test to measure submaximal aerobic capacity. In n = 9/55, (16%) of these cases ECG monitoring was used. A six-minute walk test was used at n = 37/64 (58%) as the only (n = 3) or an alternative (n = 34) test of functional capacity. When combining access to a cycle ergometer exercise test and/or a 6-minute walk test, n = 58/64 (91%) of the centers reported providing a functional test according to minimal European standards (74% of all 78 centers). Muscle function tests were performed at n = 49/64 (77%) of the centers at the pre-exercise assessment. At n = 44/64 (69%) of the centers, patients were offered an exercise log to register their physical activity and exercise activities.

Supervised center-based EBCR program

Almost all the centers reported offering some form of supervised EBCR program, n = 76 (98%). The majority provided a range of different training modalities including: circuit training (n = 58, 74%); aerobics/calisthenics (n = 42, 54%); resistance training (n = 58, 74%); hydrotherapy (n = 33, 42%); spinning (n = 19, 24%); Nordic walking (n = 8, 10%); and/or medical yoga (n = 7, 9%). At n = 25 (32%) of centers four or more exercise modalities were offered, at n = 23 (29%) of centers three exercise modalities were offered, while n = 25 (32%) of centers offered two or fewer modalities. Two centers reported not providing any center-based supervised EBCR at all. One of these reported referring some of their patients to a privately run training facility staffed with physiotherapists and exercise specialists. In total, n = 57 (73%) of centers reported delivering the minimum criterion of 24 supervised exercise sessions (range 3–72). The median duration of an exercise session was 60 minutes (range 45–90) and sessions were offered a median of twice/week (range 1–4). The total length of the EBCR program was a median of 12 weeks, with a range between one and 24 weeks. Only a few (n = 4) centers reported offering EBCR outside office hours.

Non-supervised exercise

At n = 44 (56%) of the centers, patients were offered home-based exercise alternatives that were followed up by the center physiotherapist (e.g. by telephone or applications) with an additional n = 13 (17%) offering home-based exercise without any structured follow-up by the center physiotherapist. Sixty-nine percent (n = 54) of the centers reported offering patients physical activity on prescription in accordance with the Swedish model (Onerup et al., Citation2019).

Post-exercise assessment

An individual post-exercise assessment visit after completing an EBCR program was routinely offered at n = 44 (56%) of centers. A further n = 7 (9%) reported offering post-exercise assessment but not routinely, while n = 18 (23%) of the centers reported not offering any routine pre-exercise assessment. Twelve percent (n = 9) had missing data.

Of the 44 centers routinely offering a post-exercise assessment visit, n = 28/44 (64%) reported offering a cycle ergometer exercise test. When adding the opportunity to perform a 6-minute walk test, n = 30/33 (68%) of the centers were able to offer a test of physical function as a part of the close-out visit (38% of all 78 centers). At n = 26/44 (59%) of the centers muscle function tests were conducted on the visit. The self-reported exercise log was reviewed at n = 30/44 (68%) of the centers offering a visit and at n = 34/44 (77%) the physiotherapists gave patients an exercise prescription to encourage continuous exercise as part of Phase III CR.

Facilities and equipment

Seventy-seven percent (n = 60) of the centers rated their facilities for individual visits with a physiotherapist as adequate; n = 59 (76%) rated their facilities for exercise as adequate; and n = 57 (73%) rated their exercise equipment as adequate.

Personnel

Almost all the centers reported having a multidisciplinary CR team consisting of the three core professionals: physician, nurse, and a physiotherapist n = 75 (96%). The physiotherapist was a part of the team at n = 76 (98%) of the centers. At n = 31 (40%) regular multidisciplinary team meetings to discuss patient cases were organized and at n = 60 (77%) of the centers, team meetings to discuss organizational matters and quality improvements were regularly held at least once a year. The physiotherapists were reported to participate in these team meetings at n = 62 (79%) of the centers. Based on the results of the administered cost item questionnaire the resources needed for one MI patient to participate in EBCR for 12 weeks is estimated at 11.25 physiotherapy-hours, including indirect time ().

Table 2. Direct and indirect costs of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation.

Cost analysis

The cost analysis is summarized in . The total cost of delivering guideline-based EBCR in terms of physiotherapy to one patient was 437 euro (4,371 SEK). In this model, we included the indirect costs (i.e. current patient work, consultation with other professionals, and team meetings) in addition to the direct costs (i.e. individual patient treatment and group-based treatment) (). The individually based treatment activities amounted to 271 euro (2,815 SEK; around 71% of total costs), while the group-based activities cost 11 euro (1,158 SEK).

Table 3. Direct costs of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation.

According to SWEDEHEART approximately 10,000 patients aged <80 years are treated for an acute MI every year. In 2019, 8,886 patients were followed in the SWEDEHEART-CR registry and can thus be assumed to have attended some form of CR in that year (Jernberg, Boberg, and Bäck, Citation2020). According to our estimate the yearly cost of offering all these patients registered optimal EBCR would be 3.75 million euro (38.8 million SEK) (). As patients aged 80 years and older are not included in SWEDEHEART-CR including these patients in the estimate would make the cost considerably higher. If only direct costs were included the cost/year would be 2.17 million euro (22.5 million SEK) ().

Discussion

This study describes Swedish standards of EBCR in relation to European guidelines. The costs and physiotherapy time needed for EBCR in Sweden are also presented. Studies reporting the results of surveys assessing the characteristics of comprehensive CR programs were previously available (Abreu et al., Citation2020; Pesah, Supervia, Turk-Adawi, and Grace, Citation2017; Supervia et al., Citation2019) while data on EBCR delivery against guideline recommendations are more sparse and have not been assessed in a Swedish setting. This knowledge is important to ensure the consistent provision and quality of EBCR delivery in order to achieve the greatest health benefits for patients.

In many respects, Swedish EBCR quality is high compared with the published core components of CR (Piepoli et al., Citation2014) and the minimal and optimal standards of CR (Ambrosetti et al., Citation2020). CR should start in hospital often referred to as Phase 1 CR, with physical activity and exercise counseling, preferably by a physiotherapist, and encouraging patients to participate in EBCR (Ambrosetti et al., Citation2020; Piepoli et al., Citation2014). Patients should proceed after discharge to an early supervised outpatient EBCR program (Phase 2 CR) to be maintained for life with the aim of sustaining the risk factor and lifestyle changes (Phase 3 CR) (Abreu et al., Citation2020; Ambrosetti et al., Citation2020; Piepoli et al., Citation2014). The outpatient program should ideally be started as soon as possible after the acute MI, optimally in the first 14 days and at a minimum of 30 days (Abreu et al., Citation2020; Fell, Dale, and Doherty, Citation2016). Our results showed that an outpatient visit to a physiotherapist for pre-exercise assessment was routinely offered at most of the centers, but only few patients were referred within two weeks after discharge. This result can be compared with a study by Supervia et al. (Citation2019) which reported a mean time of 3.5 weeks to enrollment in comprehensive CR globally. However, we have found no data giving details on enrollment in EBCR specifically. As the timing of EBCR has a significant impact on physical fitness improvement, the results in our study could be used to guide more effective referral routines and to highlight the need for sufficient physiotherapist resources to be able to deliver timely evidence-based care.

Before starting the EBCR program, a pre-exercise assessment is strongly recommended and should include an exercise test for risk stratification, aerobic capacity evaluation and exercise prescription (Abreu et al., Citation2020; Pelliccia et al., Citation2021; Piepoli et al., Citation2014). In our study, an individual pre-exercise assessment including a symptom-limited cycle ergometer exercise test was offered at most centers. This is consistent with the figure previously reported in Europe but according to a study by Abreu et al. (Citation2019) 77% of CR centers in high-income countries in Europe offer an exercise stress test with the European average being 70% as described by Supervia et al. (Citation2019). However, only a few Swedish CR centers have as yet implemented ECG monitoring during exercise testing which is alarmingly low, as an ECG is strongly recommended to detect potential exercise-related arrhythmias and ischemia (Pelliccia et al., Citation2021). To be able to deliver pre-exercise assessment in accordance with guidelines, this is indeed an area of improvement.

As resistance exercise is recommended as a part of a guideline-based EBCR program, an assessment of muscular function is suggested as part of the pre-exercise screening (Ambrosetti et al., Citation2020). Data from our study showed that 77% of the CR centers conducted muscle function tests at the pre-exercise assessment which is a good result as compared with 46% of European high-income country CR centers.

However, only 56% of the Swedish CR centers reported routinely offering a close-out visit indicating clear potential for improvement. In addition to the evaluation of physical capacity, offering a post-exercise assessment is also important when it comes to providing a recommendation for long-term continuous exercise (Ambrosetti et al., Citation2020). The somewhat discouraging result in Sweden may be a consequence of a reformatory change in the structure of EBCR programs within CR in 2016–2017, which might have contributed to the results. As a result, CR centers did not have time to implement every part of the new recommended EBCR delivery and it would be interesting to perform a re-survey.

Another possible explanation of why all the centers do not provide pre and post-participation assessments as recommended in guidelines could be a lack of physiotherapy resources. A lack of resources is one of the most commonly reported barrier to CR delivery around the globe (Pesah, Supervia, Turk-Adawi, and Grace, Citation2017). It continues to be baffling that CR as a highly evidence-based and cost-effective treatment is under-resourced when compared with other similarly graded recommendations for the same indications.

While it is not possible to draw firm conclusions about the cost-effectiveness of the model presented in this study, our findings suggest that the total cost of delivering optimal EBCR for the 8,886 MI patients registered in SWEDEHEART-CR in 2019 would be around 38.8 million SEK. Given the known high societal costs of MI and the effectiveness of EBCR this would appear to be a relatively small amount. Our results can also be used to calculate the amount of physiotherapist resources needed to deliver EBCR to patients after MI according to guidelines. This figure can be helpful for CR centers to estimate the amount of physiotherapy resources needed to deliver evidence-based EBCR in relation to the yearly number of patients with MI treated at the center. It is important to highlight that this study has assessed costs related to EBCR for patients after only MI, while there are also additional groups of patients with cardiovascular diagnoses attending EBCR. It can be hypothesized that the resources needed to provide EBCR to these groups of patients may be similar, but this needs to be confirmed in future studies.

An EBCR program should be adapted to each patient in order to guarantee safety, efficacy and adherence (Abreu et al., Citation2020; Ambrosetti et al., Citation2020; Piepoli et al., Citation2014). Exercise should be supervised by a physiotherapist, under medical co-ordination, and monitored in high-risk patients. The duration of EBCR needs to be individualized for every patient according to their characteristics, but, as a minimum standard, it should include at least 24 supervised sessions and optimally 36 sessions, which most of the Swedish CR centers could offer. In addition (not surveyed in the current study) in accordance with guidelines the patients followed at Swedish CR centers are encouraged to perform at least one unsupervised aerobic home-based exercise session to reach the guideline-based dose of three sessions/week of aerobic exercise (Ambrosetti et al., Citation2020; Balady et al., Citation2007; Pelliccia et al., Citation2021).

While attending a center-based supervised EBCR program is given a class 1A recommendation, home-based alternatives may be considered for patients that are unable to attend center-based programs (Abreu et al., Citation2020; Ambrosetti et al., Citation2020; Piepoli et al., Citation2014). In our study, supervised home-based EBCR programs were offered at 56% of the CR centers, which can be compared with 34% of European CR programs (Abreu et al., Citation2019) and 32% globally (Chaves et al., Citation2020). In a review of CR program delivery around the world, home-based EBCR was offered by a median of 15% of programs, while digital alternatives were offered by 11% of programs (Pesah, Supervia, Turk-Adawi, and Grace, Citation2017). The current evidence suggests that telerehabilitation may be an effective alternative or an addition for patients after an MI that are unable to participate in center-based EBCR (Scherrenberg et al., Citation2020). A small meta-analysis has shown that telerehabilitation could lead to similar or lower costs as traditional center-based CR. However, due to significant heterogeneity between included studies, more investigations of the value for money of telerehabilitation (Scherrenberg, Falter, and Dendale, Citation2020) are needed.

However, only few trials have investigated the effects of telerehabilitation on major adverse cardiovascular events and safety issues need to be evaluated in larger scale studies (Scherrenberg et al., Citation2020). Given that the barriers to participation in EBCR are already known (Balady et al., Citation2011) together with the addition of new challenges in the ongoing pandemic, there is a call for action to evaluate feasible, safe and evidence-based options for remotely delivered EBCR (Scherrenberg et al., Citation2020).

A multidisciplinary CR team is strongly recommended to cover the skills and competence necessary to achieve the main components of CR (Ambrosetti et al., Citation2020; Piepoli et al., Citation2014). As a minimum standard, the team should include a cardiologist, physiotherapist (exercise specialist), nurse, and nutritionist (Abreu et al., Citation2020). In our study, physiotherapists were part of the team at 98% of Swedish CR centers, which is above the average of 90% in high-income countries in Europe and 59% in other high-income countries globally (Abreu et al.,Citation2019; Pesah, Supervia, Turk-Adawi, and Grace, Citation2017). In another recent survey-based study, an average of 80% of European CR centers reported including physiotherapists in their CR team (Supervia et al., Citation2019).

Regular multidisciplinary team meetings are important to enable communication between members and to provide opportunities to discuss complex clinical cases and evaluate the ongoing program (Abreu et al., Citation2020; Piepoli et al., Citation2014). In our study, below half of the CR centers reported that they organized regular team meetings to discuss patient cases, which leaves room for improvement. Based on clinical experience, the low numbers may be due to making direct contact within the CR team whenever consultation is needed. On the other hand, more CR centers reported meeting at least once annually to discuss organizational matters and quality improvement and using audit data for quality control, which is well in line with the optimal criterion of performing an annual evaluation of delivery and outcomes as described by Abreu et al. (Citation2020). Systematically monitoring the process of delivery and outcomes is important as a means of measuring and improving care (Ivers et al., Citation2012). Clinical registries are effective for audit and evaluation through systematic data collection and have the potential to capture data that reflect real-world clinical practice. A systematic review found seven available CR registries and one international registry (Poffley et al., Citation2017), of which the majority captured patient-level data on EBCR. Information on the process-based metrics of EBCR program delivery was reported less frequently (Poffley et al., Citation2017) and is not available in the SWEDEHEART registry either (Bäck et al., Citation2021). As a result, the reasons for the variation in treatment goal attainment in CR are largely unknown. The use of standards for the evaluation of the quality of CR has so far been tested successfully by using the National Audit of Cardiac Rehabilitation registry in the United Kingdom, to ensure that CR is delivered in a safe way with prognostic benefits (Doherty et al., Citation2017). Moreover, the more recently launched Danish CR Database collects program-level data every three years through surveys targeted at CR staff that can be compared with patient outcome over time (Zwisler et al., Citation2016).

Strengths and limitations

One strength of the present study was the exceptionally high national representation with all 78 CR centers in Sweden at the time of the study included, while previously published studies are limited by low response rates which lead to ascertainment bias (CitationAbreu et al., 2019; Supervia et al., Citation2019). The major limitation of the Perfect-CR questionnaire is that it is not fully validated. However, as the questions were based on core components of current guidelines and thus mostly of objective nature covering multiple aspects of EBCR we believe that the questionnaire provided data of sufficient quality for the present study objectives.

Conclusions

While EBCR delivery in Sweden is highly consistent with European and national guidelines, there are several areas that need to be improved. It is crucial to encourage centers to offer evidence-based pre- and post-exercise assessments to secure the safety and efficacy of exercise. Moreover, access to supervised center-based exercise programs must be enhanced, but it is also suggested that supervised home-based alternatives should be further assessed to increase flexibility and variation. Resources in terms of both direct and indirect costs require sufficient funding for the implementation of an evidence-based EBCR program. Sufficient physiotherapist staffing must be considered. The present survey assessed the structure- and process-based metrics of EBCR, but it is not possible to ascertain how these translate to goal attainment and this must be studied in more detail. In a future study based on the Perfect-CR study we plan to examine the association between CR program standards and patient outcomes in order to identify predictors of treatment goal fulfillment in EBCR. To enable the benchmarking of results against other countries, the creation of a common CR registry would be ideal.

Acknowledgments

This article was written on behalf of the Perfect-CR steering committee, with a special acknowledgment to Mona Schlyter and Ingela Sjölin for their kind help with data collection. We wish to express our sincere gratitude to all the healthcare professionals that have answered the survey.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abreu A, Frederix I, Dendale P, Janssen A, Doherty P, Piepoli MF, Völler H, Davos CH; Secondary Prevention and Rehabilitation Section of EAPC 2020 Standardization and quality improvement of secondary prevention through cardiovascular rehabilitation programmes in Europe: The avenue towards EAPC accreditation programme: A position statement of the secondary prevention and rehabilitation section of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC). European Journal of Preventive Cardiology. doi: 10.1177/2047487320924912. Online ahead of print.

- Abreu A, Pesah E, Supervia M, Turk-Adawi K, Bjarnason-Wehrens B, Lopez-Jimenez F, Ambrosetti M, Andersen K, Giga V Vulic D, et al. 2019 Cardiac rehabilitation availability and delivery in Europe: How does it differ by region and compare with other high-income countries?: Endorsed by the European Association of Preventive Cardiology. European Journal of Preventive Cardiolology 26: 1131–1146.

- Ambrosetti M, Abreu A, Corrà U, Davos CH, Hansen D, Frederix I, Iliou M, Pedretti RF, Schmid JP, Vigorito C, et al. 2020 Secondary prevention through comprehensive cardiovascular rehabilitation: From knowledge to implementation. 2020 update. A position paper from the secondary prevention and rehabilitation section of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology. doi: 10.1177/2047487320913379. Online ahead of print.

- Bäck M, Leosdottir M, Hagstrom E, Norhammar A, Hag E, Jernberg T, Wallentin L, Lindahl B, Hambraeus K 2021 The SWEDEHEART secondary prevention and cardiac rehabilitation registry (SWEDEHEART CR registry). European Heart Journal - Quality of Care and Clinical Outcomes 7: 431–437.

- Balady GJ, Ades PA, Bittner VA, Franklin BA, Gordon NF, Thomas RJ, Tomaselli GF, Yancy CW 2011 Referral, enrollment, and delivery of cardiac rehabilitation/secondary prevention programs at clinical centers and beyond: A presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation 124: 2951–2960.

- Balady GJ, Williams MA, Ades PA, Bittner V, Comoss P, Foody JM, Franklin B, Sanderson B, Southard D 2007 Core components of cardiac rehabilitation/secondary prevention programs: 2007 update: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association Exercise, Cardiac Rehabilitation, and Prevention Committee, the council on clinical cardiology; the councils on cardiovascular nursing. Epidemiology and Prevention, and Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism; and the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation. Circulation 115: 2675–2682.

- Chaves G, Turk-Adawi K, Supervia M, Santiago de Araujo Pio C, Abu-Jeish AH, Mamataz T, Tarima S, Lopez Jimenez F, Grace SL 2020 Cardiac rehabilitation dose around the world: Variation and correlates. Circulation Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes 13: e005453.

- Dibben G, Faulkner J, Oldridge N, Rees K, Thompson DR, Zwisler AD, Taylor RS 2021 Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Systematic Review 11: CD001800.

- Doherty P, Salman A, Furze G, Dalal HM, Harrison A 2017 Does cardiac rehabilitation meet minimum standards:An observational study using UK national audit? Open Heart 4: e000519.

- Drummond MF 2015 Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Fell J, Dale V, Doherty P 2016 Does the timing of cardiac rehabilitation impact fitness outcomes? An Observational Analysis. Open Heart 3: e000369.

- Ivers N, Jamtvedt G, Flottorp S, Young JM, Odgaard-Jensen J, French SD, O’Brien MA, Johansen M, Grimshaw J, Oxman AD 2012 Audit and feedback: Effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Systematic Review 6: CD000259.

- Jernberg T, Boberg B, Bäck M 2020 SWEDEHEART Annual Report 2019. https://www.ucr.uu.se/swedeheart/dokument-sh/arsrapporter-sh/aeldre-arsrapporter-older-reports/arsrapport-2019/1-swedeheart-annual-report-2019.

- Kotseva K, De Backer G, De Bacquer D, Ryden L, Hoes A, Grobbee D, Maggioni A, Marques-Vidal P, Jennings C, Abreu A, et al. 2019 Lifestyle and impact on cardiovascular risk factor control in coronary patients across 27 countries: Results from the European Society of Cardiology ESC-EORP EUROASPIRE V registry. European Journal of Preventive Cardiolology 26: 824–835.

- Lawler PR, Filion KB, Eisenberg MJ 2011 Efficacy of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation post-myocardial infarction: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. American Heart Journal 162: 571–584 e572.

- Ogmundsdottir Michelsen H, Sjolin I, Schlyter M, Hagstrom E, Kiessling A, Henriksson P, Held C, Hag E, Nilsson L, Bäck M, et al. 2020 Cardiac rehabilitation after acute myocardial infarction in Sweden - evaluation of programme characteristics and adherence to European guidelines: The perfect cardiac rehabilitation (Perfect-CR) study. European Journal of Preventive Cardiolology 27: 18–27.

- Onerup A, Arvidsson D, Blomqvist Å, Daxberg EL, Jivegård L, Jonsdottir IH, Lundqvist S, Mellén A, Persson J, Sjögren P, et al. 2019 Physical activity on prescription in accordance with the Swedish model increases physical activity: A systematic review. British Journal of Sports Medicine 53: 383–388.

- Pelliccia A, Sharma S, Gati S, Bäck M, Borjesson M, Caselli S, Collet JP, Corrado D, Drezner JA, Halle M, et al. 2021 2020 ESC Guidelines on sports cardiology and exercise in patients with cardiovascular disease. European Heart Journal 42: 17–96.

- Pesah E, Supervia M, Turk-Adawi K, Grace SL 2017 A review of cardiac rehabilitation delivery around the world. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases 60: 267–280.

- Piepoli MF, Corra U, Adamopoulos S, Benzer W, Bjarnason-Wehrens B, Cupples M, Dendale P, Doherty P, Gaita D, Hofer S, et al. 2014 Secondary prevention in the clinical management of patients with cardiovascular diseases. Core components, standards and outcome measures for referral and delivery: A policy statement from the cardiac rehabilitation section of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation. Endorsed by the Committee for Practice Guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology 21: 664–681.

- Poffley A, Thomas E, Grace SL, Neubeck L, Gallagher R, Niebauer J, O’Neil A 2017 A systematic review of cardiac rehabilitation registries. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology 24: 1596–1609.

- Sandercock G, Hurtado V, Cardoso F 2013 Changes in cardiorespiratory fitness in cardiac rehabilitation patients: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Cardiology 167: 894–902.

- Scherrenberg M, Falter M, Dendale P 2020 Cost-effectiveness of cardiac telerehabilitation in coronary artery disease and heart failure patients: Systematic review of randomized controlled trials. European Heart Journal - Digital Health 1: 20–29.

- Scherrenberg M, Wilhelm M, Hansen D, Voller H, Cornelissen V, Frederix I, Kemps H, Dendale P 2020 The future is now: A call for action for cardiac telerehabilitation in the COVID-19 pandemic from the secondary prevention and rehabilitation section of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology. doi: 10.1177/2047487320939671. Online ahead of print.

- Shields GE, Wells A, Doherty P, Heagerty A, Buck D, Davies LM 2018 Cost-effectiveness of cardiac rehabilitation: A systematic review. Heart 104: 1403–1410.

- Steen Carlsson K, Höjgård S, Lethagen S, Berntorp E, Lindgren B 2004 Economic evaluation: What are we looking for and how do we get there. Haemophilia 10(Suppl 1): 44–49.

- Supervia M, Turk-Adawi K, Lopez-Jimenez F, Pesah E, Ding R, Britto RR, Bjarnason-Wehrens B, Derman W, Abreu A, Babu AS, et al. 2019 Nature of cardiac rehabilitation around the globe. EClinicalMedicine 13: 46–56.

- Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare 2018 Nationella Riktlinjer för Hjärtsjukvård [National Guidelines for Cardiac Care] Sverige. https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/kunskapsstod-och-regler/regler-och-riktlinjer/nationella-riktlinjer/riktlinjer-och-utvarderingar/hjartsjukvard/.

- Turk-Adawi K, Sarrafzadegan N, Grace SL 2014 Global availability of cardiac rehabilitation. Nature Reviews Cardiolology 11: 586–596.

- Verschueren S, Eskes AM, Maaskant JM, Roest AM, Latour CH, Op Reimer WS 2018 The effect of exercise therapy on depressive and anxious symptoms in patients with ischemic heart disease: A systematic review. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 105: 80–91.

- Visseren FL, Mach F, Smulders YM, Carballo D, Koskinas KC, Bäck M, Benetos A, Biffi A, Boavida JM, Capodanno D, et al. 2021 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. European Heart Journal 7: 3227–3337.

- Zwisler AD, Rossau HK, Nakano A, Foghmar S, Eichhorst R, Prescott E, Cerqueira C, Soja AM, Gislason GH, Larsen ML, et al. 2016 The Danish cardiac rehabilitation database. Clinical Epidemiology 8: 451–456.