ABSTRACT

The aim of this paper is to understand the expansion process of investment into Purpose Built Student Accommodation (PBSA) in Europe by examining transformations in student housing investment landscapes and uncovering the profiles and strategies of key investors between 2010 and 2020. Using data from Real Capital Analytics, trends in capital structures and profiles of PBSA investors are identified. Investors driving these trends are scrutinised in terms of their investment timelines, locations, hold periods and strategies of portfolio diversification. Furthermore, in-depth interviews with property analysts, PBSA investors, and developers substantiate the quantitative analysis. The empirical results show that Private Equity entered the European PBSA market, starting with the UK, when the yield premium post-GFC justified the perceived risk. Equity funds typically hold their portfolios for around five years and trade counter-cyclically with institutions such as pension funds. PBSA specialists, mainly REITs, have accumulated substantial portfolios, and the REIT structure is well-suited to the steady income which student rents should provide, but their lack of diversification leaves them vulnerable to changes in student demographics and accommodation requirements.

1. Introduction

Student housing investment is flourishing. In May 2020, amid the UK’s first Covid-19 lockdown, Blackstone purchased iQ Student Accommodation from the Wellcome Trust and Goldman Sachs for €5.22bn. It was the UK’s largest ever private property transaction in any sector, and the biggest student housing transaction globally to date (Mallinson, Citation2020). The transaction epitomised the global expansion of student housing from an ‘alternative property sector (Newell & Marzuki, Citation2018) into a recognised (French et al., Citation2018) or even ‘mainstream worldwide asset class’ (Revington & August, Citation2019). While student housing in North America has been a substantial asset class for many years (CBRE, Citation2019; Savills, Citation2018), its expansion in Europe – with the exception of the UK which has a relatively well-established student housing investment market – is a somewhat recent process (Pyle, Citation2018).

In this paper, we set out to understand the expansion process of investment into Purpose Built Student Accommodation (PBSA) in Europe. Academic engagement with student housing investment in the European context is limited, and cross-country comparisons are even more scarce. Furthermore, the existing literature on student housing investment primarily focuses on internal and external drivers for investors to engage with PBSA (French et al., Citation2018; McCann et al., Citation2020; Newell & Marzuki, Citation2018). While ‘modern property investment allocation techniques are typically based on recognised measures of return and risk’ (Higgins, Citation2015, p. 481), positivist approaches which assume investors’ rational decision-making fall short in shedding light on the actual expansion process of student housing into a maturing asset class. Therefore, we develop a thematic framework derived from the review of property investor types devised by Özogul and Tasan-Kok (Citation2020) to analyse the characteristics of key investors and their strategies driving the expansion of European student housing investments.

Our analysis is twofold. First, we identify changes in the student housing investment landscapes of the five European countries with the highest number of PBSA investment transactions since 2010: the UK, Germany, the Netherlands, France, and Spain. Paying attention to domestic and cross-border transactions, and the type of capital used by investors, we paint a comprehensive picture of the evolution of PBSA investments. We find that following the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), the student housing sector came onto the radar of equity funds and investment managers in their search for yield and portfolio diversification. Meanwhile, PBSA specialists, mainly REITs, built scale – initially through development and later by acquisition – typically collaborating with pension funds and Sovereign Wealth Funds. The UK has the most established PBSA market, but continental Europe is proving increasingly attractive to investors in the sector.

Second, we define key investors driving these trends and scrutinise their investment strategies in terms of their investment timelines, locations, hold periods and strategies of portfolio diversification. We find that global investors that have developed or acquired PBSA in continental Europe mostly preceded that activity with investment in UK PBSA around five years earlier. Opportunistic Private Equity entered the PBSA market when the yield premium post-GFC justified the risk. They built portfolios, which they held for around five years and sold once banks started being willing to lend to purchasers. PBSA specialists, mainly REITs, have accumulated substantial portfolios, and the REIT structure is well-suited to the steady income which student rents should provide, but their lack of diversification puts such investors at higher risk if fewer students require accommodation, such as during the Covid pandemic.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews existing PBSA literature and provides theoretical considerations regarding investor characteristics and strategies. Section 3 outlines the methodology and data. Section 4 provides a cross-country comparison of PBSA investments, followed by an in-depth investigation of investment strategies of key investors active in these countries in Section 5. Finally, in Section 6, we discuss and conclude our findings.

2. Literature review

2.1 Purpose built student accommodation

Literature on student housing investment, and particularly PBSA, predominantly focuses on the external and internal drivers of investors. Discussions on external drivers centre around growing numbers of students in tertiary education, affordability of tuition fees and visa rules facilitating the arrival of international students (French et al., Citation2018). Scholars underscore that the growth of the student housing sector is a phenomenon that follows the simple logic of supply and demand (Lizieri, Citation2003). As the existing housing stock cannot keep up with growing student numbers, it provides student housing investors with better returns than other sectors (French et al., Citation2018), at least in locations with a successful Higher Education institution in their catchment area and a market that is not over supplied (Hale & Evans, Citation2019).

Furthermore, regulatory changes and their effects on PBSA are discussed. For instance, barriers to the construction of new student housing have been removed to meet soaring demand. In the UK, the National Planning Guidance stipulates that local authorities have to account for student housing in their plans, and newly constructed units count towards meeting local authorities’ housing targets (Greater London Authority, Citation2021). In the Netherlands, regulatory changes to housing subsidies drove up demand for PBSA: when subsidies were no longer available for shared student housing, demand for independent student housing units grew considerably (Wilberts et al., Citation2019). Lastly, lifestyle changes and student preferences are discussed in relation to external drivers for the rising popularity of PBSA, by academics (Forrest et al., Citation2019; French et al., Citation2018; McCann et al., Citation2020) and property industry consultants alike (CBRE, Citation2020; S. S. Jones, Citation2020; Knight Frank, Citation2019; Savills, Citation2018).

Internal drivers, on the other hand, focus on investors’ shift in preferences to capital allocations outside traditional sectors (McIntosh et al., Citation2017). Student housing, driven by strong demand, provides opportunities for attractive, long-term yields (CBRE, Citation2020; Newell & Marzuki, Citation2018). As early as 2009, Savills (Citation2009, p. 2) was pointing out that student housing offers ‘attractive investment returns, long-term income streams, rental growth prospects and high occupancy rates’. Where student accommodation is built for a university by a developer who the operates it, leases tend to be long, typically 35 or even 50 years (Osborne Clarke, Citation2017; Owens, Citation2017), and yields have been around 5–6% in recent years, with low vacancy rates and a reliable income stream (Cushman & Wakefield, Citation2021; Gilmore, Citation2019; Pyle, Citation2018). Of course, not all PBSA investment is successful (see, for example, Phillips, Citation2019a), but diversified portfolios that include student housing are said to be more resilient against market downturns and can mitigate risks (Newell & Marzuki, Citation2018), ‘being a counter-cyclical income stream that proves resilient when other real estate sectors may be experiencing cyclical downturns’ (Fiorentina et al., Citation2020). While private rental housing markets are booming, particularly in cities with high student populations (Hochstenbach et al., Citation2020), PBSA allows large-scale investors to become influential players in the student housing market. Corporate investors, for example, entered the PBSA sector in the UK in the mid-2000s and quickly superseded individual one-off investors who accessed buy-to-let mortgages (Leyshon & French, Citation2009).

Analyses of investment drivers provide valuable information on the (rational) decision-making processes of investors in their investment allocations. Insights on investor strategies and the actual expansion process of PBSA investments, however, is limited (Fiorentina et al., Citation2020). Focusing on the Canadian context, Revington and August (Citation2019) and Revington et al. (Citation2020) argue that the private PBSA market is the result of active investor strategies to create a market for themselves within the framework of financialisation. Furthermore, Brill and Özogul (Citation2021) found that the global investor Greystar utilised student housing to gain a better understanding of local markets in London and Amsterdam before expanding to other sectors. Additionally, student housing investment reports produced by private consultancies have proliferated in recent years, yet the number of academic accounts on PBSA investment remains low. They also often come from critical geography, planning and urban studies scholarship, having limited engagement with residential investor stratifications, leading to generalisations and stereotyping (Özogul & Tasan-Kok, Citation2020).

2.2 Investor profiles

Property research tends to explain investment market transformations from the perspective of market maturity (Keogh & D’arcy, Citation1994; de Magalhães, Citation2001). Market maturity entails ‘the diversification of investor opportunities, market openness, an established information and research system, professional standards and the standardization of property rights and market practices’ (de Magalhães, Citation2001, p. 101). More recently, discussions have turned to assessing maturity of individual asset classes or sectors (Gallent et al., Citation2018; McIntosh et al., Citation2017; Portlock & Mansley, Citation2021). For PBSA investment, the US and UK markets are considered the most mature, but ‘the sector is maturing fast in mainland Europe’ (Savills, Citation2019b). Rather than assessing the maturity level of PBSA, however, we are more interested in the investors themselves and how their profiles changed over time.

Since 2015, investors have spent on average $16.7 billion per year on direct PBSA acquisitions globally (Mallinson, Citation2020). This popularity is driven by institutional investors’ turn to alternative property sectors (Newell & Marzuki, Citation2018), and Sovereign Wealth Funds (SWFs) in particular quadrupled their investment in PBSA between 2012 and 2017 (Capape, Citation2019). In the US, the PBSA market transformed from being dominated by developer-operators, but was quickly taken over by Equity Funds, SWFs, Pension Funds and Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) as the most active players (Young, Citation2012). Similar trends are described across Europe (Espinoza, Citation2018; Savills, Citation2019a), but a detailed academic account of the transformation of investor profiles is missing to date.

The type of utilised capital is an important marker of PBSA investor profiles and is often linked to investment strategies in the existing literature. According to Savills (Citation2019a), private investors and SWFs initially had ‘a bigger appetite’ for student housing investments, but a growing number of funds and insurance companies followed. Private investors are often addressed in terms of different categories of high-net-worth individuals engaging in real estate investments (Rogers & Koh, Citation2017, p. 3). Institutional capital – of which SWFs, Equity Funds, Pension Funds and Investment Managers are exemplary investor categories – is invested on behalf of organisations’ members and often includes large portfolio investments and sophisticated investment strategies. Similarly, REITs and other listed real estate companies typically acquire real estate portfolios to support long-term strategies that achieve stable cash flows for their shareholders (Wijburg et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, such companies spread risk and eliminate the necessity of expertise for shareholders who want to take part in real estate investment (Waldron, Citation2018).

Increasingly, pension funds and insurance companies are mindful of ‘reputational risk’ when considering how their residential investments are managed (Bentham, Citation2021; Murray-West, Citation2021). Likewise, emphasis on ‘Impact Investing’ has led to explicit recognition of social benefits (Fixsen, Citation2018), which investors can leverage in their PBSA schemes. Nevertheless, while real estate scholars point out the long-term strategies of institutional investors and REITs, the very same categories are what critical scholars define as ‘financialised landlords’ with aggressive management strategies undervaluing the social functions of (student) housing (Revington & August, Citation2019; Revington et al., Citation2020). Thus, research based on extensive empirical insights is needed, to connect capital structures and, more importantly, different investor types and individual firms, to investment strategies (Brill & Özogul, Citation2021; Özogul & Tasan-Kok, Citation2020).

Another common element to profile an investor is whether they are operating domestically or engage in cross-border transactions. PBSA increasingly attracts foreign investors (Newell & Marzuki, Citation2018a) and globally, cross-border capital ‘accounted for 40% of investment into student accommodation over the last three years’ (Knight Frank, Citation2019, p. 6). 75% of this cross-border capital came from institutional investors (ibid), compared with 39% in 2017 (Savills, Citation2019a). Possible explanations include domestic investors being slow to recognise the benefits offered by residential investment in general and PBSA in particular, the diversification benefits for these foreign investors and exchange rates that make overseas purchases more attractive at certain times, but overseas investors typically pay more than domestic investors when purchasing properties due to a lack of local market knowledge (Devaney & Scofield, Citation2017). Yet, a major challenges lies in defining cross-border investors, particularly in light of global firms with multiple headquarters, several capital sources, and local partners to bridge local knowledge gaps (McAllister & Nanda, Citation2016). Thus, again, caution is advised in drawing hasty conclusions, and a multidimensional analysis is needed to uncover investment strategies (Tasan-Kok & Özogul, Citation2021).

2.3 Investment strategies

Analysing investor profiles and investment strategies conjointly can provide in-depth empirical evidence on the expansion process of student housing investment in Europe. From the field of behavioural economics, it is known that investors do not always act according to the most rational, profit-maximising way. Instead, this neoclassical assumption of ‘perfect human rationality’ is disputed on the basis of cognitive limitations (De Bruin & Dupuis, Citation2000), emotions and subjectivities (Byrne et al., Citation2013). Furthermore, each investor follows a unique investment strategy, places varying emphasis on market knowledge and has differentiated preferences. To shed light on investment strategies, we follow the framework devised by Tasan-Kok and Özogul (Citation2021) who highlight locational and strategic behaviour in terms of hold periods. We add the specific component of portfolio diversification in relation to PBSA investment, and place additional emphasis on investment timelines to scrutinise cross-border expansion of PBSA investments.

With the dimension of investment timelines, we focus on the temporal elements of PBSA investment activities and the expansion of investors into new investment markets. This becomes particularly interesting in relation to the fact that some investors seem to utilise student housing as a low-risk investment opportunity to create local networks and knowledge on local investment markets before venturing into other forms of residential investment (Brill & Özogul, Citation2021). The dimension of investment locations sheds light on the territorial strategies of investors. It is to be expected, in line with PBSA drivers, that investments centre around major cities with high student populations. However, with PBSA being rolled out more widely, it becomes interesting to investigate potential shifts towards smaller towns or regional dynamics.

Investment hold periods indicate the average amount of time that student housing properties are held by a specific investor or investor group. This inquiry becomes particularly important in relation to the differing perspectives on short- versus long-term hold periods of particular investor types and forms of capital in PBSA. Lastly, the analysis of portfolio diversification relates to the extent to which PBSA constitutes an investment priority of an investor, and the position it takes within the overall investment portfolios. In reality, investor profiles and these four investment strategy dimensions are all inter-related. However, with regards to understanding the PBSA expansion process, this framework allows for a structured, targeted, and multifaceted analysis.

3. Methodology

This paper employs a mixed-methods approach. Quantitative investment transaction data is retrieved from Real Capital Analytics (RCA),Footnote1 providing detailed information on transactions larger than €5 M. The database contains details of nearly 2000 transactions of student housing property in Europe, of which only around 100 occurred prior to 2010. More than half of these transactions were for properties in the UK, and the majority of the rest were in one of four countries: Germany, the Netherlands, France and Spain (see ). Combined, constituting more than 90% of PBSA transactions, we selected these five countries to understand changing student housing investment trends in terms of capital and investor types, and domestic and cross-border investments, from 2010 until the end of 2020. Additionally, we reviewed a wide range of reports on PBSA by real estate companies and consultancies such as Savills, CBRE, and Knight Frank to verify investment trends and identify changing discourses on student housing investment within the industry.

Table 1. European countries with the highest numbers of PBSA transactions in RCA database (to 31/12/2020)

RCA also provides access to more than 200,000 investor profiles, including their holdings and transaction history, capital and ownership information, and investment locations. RCA classifies investors by capital type: Equity Funds, Pension Fund, Insurance Companies, Banks, Investment Management Firms and Sovereign Wealth Funds are categorised under Institutional Capital, Listed Capital comprises public REITs and REOCs, while Private Capital encompasses Private REITs and Developer/Owner/Operators.

We identified key investors driving PBSA investment trends across the five countries and gathered information on the four dimensions of their investment strategies. We also followed a simple differentiation of foreign versus domestic headquarters to indicate cross-border or domestic transactions. We supplemented RCA data with sources including investor websites and annual reports.

For the qualitative analysis, we conducted 33 interviews to understand the changing investment contexts in Western Europe more broadly, including eight targeted interviews with student housing developers, investors, and analysts to confirm our research findings and complement our quantitative arguments with qualitative insights. Interviewees, who were identified through a snowballing technique, comprised senior staff (partners, directors, heads of departments, senior managers, senior analysts) from the major global consultancies, PBSA and housing developers, PBSA REITs, private equity funds, and investment management firms. Interviews were conducted between July 2020 and July 2021, thus take into account the systemic shock of the Covid-19 pandemic.

4. Transformations in the European student housing investment landscape

The UK, Germany, Netherlands, France and Spain differ in terms of university metrics. Germany, France and the UK have the most students (c. 2.5–3 M each) and the UK has the largest number of overseas students, at around half a million (Eurostat, Citation2020). Tuition fees are highest in the UK and ‘Tendencies for many European students to live with parents reduces the requirement for dedicated student accommodation in those locations’ (Savills, Citation2013, p. 5).

Nevertheless, investment in PBSA follows an upward trend in all these countries. The UK takes on a special position, having the most established PBSA market, with the first specialist student housing provider Unite founded in 1991 (Global Students Accommodation, Citation2021). Nonetheless, continental Europe is catching up fast, having attracted ‘approximately $2.3bn of inward investment in the last three years’ (Knight Frank, Citation2019, p. 11). In general, mainland Europe is said to lag behind the UK and the US by 10–15 years in terms of investment trends (Young, Citation2012). This point is reiterated by Hale and Evans (Citation2019) and by Greystar’s Managing Director of European Investment, Troy Tomasik, who predicted that capital values of PBSA will rise faster in the ‘less mature markets in Continental Europe’ than in the UK (Phillips, Citation2019b).

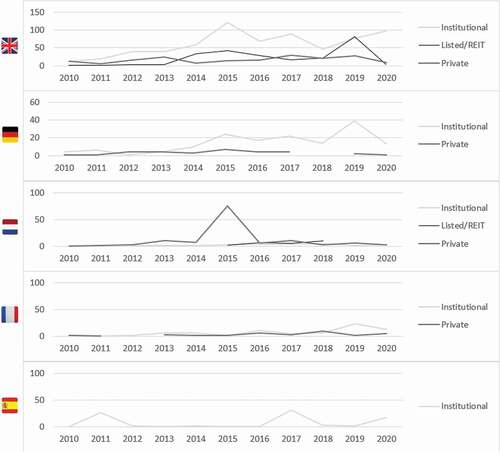

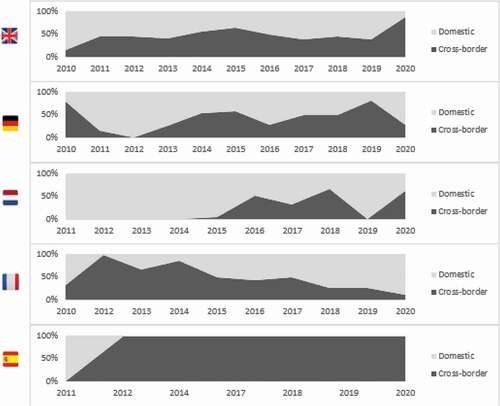

In Germany, PBSA investment increased by 380% in 2016, following 8 years of continuous growth (The Glide Group, Citation2019). In the Netherlands, student housing investments reached a new record in 2016, quickly developing to an ‘asset class in its own right’ (Savills, Citation2017, p. 1), with strong projected growth (Shelton, Citation2019). In France and Spain, investment activity is also projected to grow significantly (JLL, Citation2018, Citation2019; Savills, Citation2019a; Smyth, Citation2020) with Brookfield’s Student Roost platform recently acquiring the Suit’Etudes brand in France and Livensa Living in Spain (Brookfield Asset Management, Citation2021). Although the number of domestic students in Spain is declining, this is more than compensated for with the growth in overseas students (ibid) and institutional investors have recently purchased multiple PBSA properties, including the 37-property Resa portfolio (AXA IM – Real Assets, Citation2017; JLL, Citation2019). In all countries, looking at RCA data, we see an upward trend in transaction volume over time (). These transactions include entity (company merger) and portfolio transactions as well as those of individual properties.

Comparing the growth of PBSA transactions in the property markets of our five selected countries, we can see interesting trends. In the largest PBSA markets, UK and Germany, institutional investment grew, and in Spain, it is in fact the only investment capital that is recorded, albeit still on a small scale in comparison. France is the only country where institutional capital is not increasing and is lower than private capital flowing into PBSA. Listed/REIT capital is growing only in the UK and emerged in the Netherlands in 2015 but is not yet well established elsewhere. The involvement of private capital appears to be reducing.

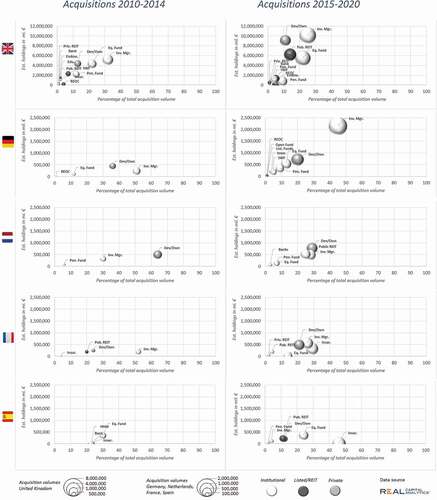

Of course, it is difficult to draw conclusions from these graphs alone, as property markets are socially constructed and deeply embedded in a specific political and regulatory context. By analysing investor types, estimated holdings, acquisitions and percentage of total acquisition volumes over the course of two periods (2010–2014 inclusive and 2015–2020 inclusive), we observe changes over time (). Because investment in the UK PBSA market is so much greater, a different scale has been used for the UK graphs.

Figure 2. Capital structure of investors in European PBSA. a. Acquisitions 2010–2014. b. Acquisitions 2015–2020.

Institutional investors have expanded in all five national PBSA markets and their diversity has increased. Overall, the picture becomes much more complex in all five markets in the 2015–2020 period. In actual numbers, investment managers have been driving the trend, although they already had dominance in most markets. Even in those countries where their overall share of the market decreased, partly because of the growing market actor complexities, the acquisition volumes of investment managers increased massively. However, the involvement of private developers has declined over the past few years, as institutional developers have increasingly developed their own PBSA, sometimes with a Joint Venture partner, and have increasingly transacted existing PBSA portfolios.

Simply looking at cross-border versus domestic investments without further inquiry on the source of origin, however, interesting patterns emerge (). In the Netherlands, cross-border investment in PBSA began in 2014. Domestic investors have taken an increasing share of the market in France, while in Germany they have a roughly equal share. Spain’s PBSA market is almost entirely led by cross-border investments.

To sum up, there is a clear shift in capital, driven by institutional investors. Pension funds and investment managers constitute a growing group and there are also differences in market share between domestic and cross-border investors. This picture paints a useful overview, but this type of analysis omits certain aspects. In continental Europe, cross-border investment tends to comprise joint ventures with a local partner or transactions between near neighbours (Swiss Life investing in France, the Belgian student housing REIT Xior operating in The Netherlands, and the Luxembourg Equity Fund DREF investing in Germany). Only in the more developed UK market do substantial investments by major overseas players occur – primarily large American Equity Funds and Investment Management Firms, Canadian Pension Funds and Singaporean Pension and Sovereign Wealth Funds. Probing these trends requires a more thorough analysis of investors as property market actors.

5. Investment strategies of PBSA trendsetters

To scrutinise the expansion process of student housing investment in Europe, we identified key players in student housing investment driving the trends across the five selected countries between 2010–2020. These were selected from RCA as major investors that retained PBSA property in one or more of the five countries at the end of 2020. shows the investor, type and the location of the headquarters of each organisation. It also shows the European PBSA holdings of each at the end of 2020 as a proportion of their total global property assets. It is, of course, just a snapshot. Some major players in the European PBSA market have acquired substantial holdings but disinvested by the end of 2020, thus do not appear in the table. For example, CPP Investment Board, the Canadian Public Pension Fund, headquartered in Toronto, Canada, bought the 42-property Liberty Living UK PBSA portfolio in March 2015 at a cost of €1.5 bn, but sold it to Unite in November 2019 for €2.5 bn, by which time the portfolio comprised 56 properties.

Table 2. Key Investors in European PBSA

Regarding the types of firms that invest in PBSA, it is evident from that many of the major players are Equity Funds and Investment Management firms, with their substantial portfolio transactions comprising most of the investment volume. Interviewees explained that private equity core funds ‘have a reasonable amount of PBSA in them and the outsourcing operations is very well understood’ (Analyst 4) and that ‘people like Greystar and Blackstone, they’re super active. [They] have come over and applied the US model to the UK and are quite highly leveraged funds that have a finite time period, so it will be a question of building up a platform, getting up to critical mass and possibly exiting and/or going forward … [They aim to] assemble a portfolio of two to three billion that was stabilised, then there’ll be a huge amount of institutional pension funds who’d like to buy it’ (Analyst 2).

According to one interviewee, ‘these things had to come together for student housing to become a recognised asset class, of interest to private equity and investment managers: yields falling, so that institutions would invest in the sector; professional management; debt funding – from the early 2010s banks started to be willing to lend for development of student accommodation’ (Investor 12).

Several of the key players in the European PBSA market are REITs. The REIT structure is appropriate for investment in, and management of, student accommodation because the reliability of rental income conforms to the requirement that most of the profits derive from rental property. This point was made by several interviewees:

‘Student lends itself quite nicely to a REIT structure, with comparatively predictable income and sustainability of paying dividends. You don’t want loads of fluctuations, you just want good, steady performance’ (Consultant 5).

‘[Student housing provides] certainty of income and it rises, broadly, at the rate of inflation, so you have almost an index-linked product’ (Investor 3).

Unite converted to REIT status on 1 January 2017, exactly a decade after the inception of UK REITs and 25 years after it first started developing UK PBSA. In the letter to shareholders seeking approval for the conversion (The Unite Group PLC, Citation2016), the directors emphasised the beneficial tax arrangements that would ensue.

The French REIT market is a few years older than that of the UK (inception 2003), and is second to the UK in size (Moss, Citation2018). The German REIT market began in the same year as that of the UK, while Spanish REITs commenced in 2009 (ibid). The Dutch REIT market ranks third in size, and is the oldest, having been started in 1969. However, none of these REITs invest in student housing. The most active REIT investor in European countries other than the UK is the Belgian REIT Xior Student Housing. Xior has student housing in 30 cities across the Netherlands, Spain, Belgium, and Portugal, as well as office blocks or other properties to be built or converted as part of the REIT’s development pipeline over the next three years (Xior Student Housing, Citation2021).

Several of the key investors shown in are Pension Funds. Student housing is well-suited to the requirements of pension funds because it should be possible to match rental income to the liabilities of the fund, and the possibility of long leases is appropriate for the ‘patient capital’ that they can employ. As one interviewee commented: ‘I keep going back to that security of income, so it’s a terrific pension fund product’ (Analyst 6).

Other interviewees commented on the similarity of PBSA as an investment product to the commercial property they traditionally held.

‘A lot of these pension funds are used to a buy and hold 25 years FRI lease’ (Consultant 4).

‘PBSA was what attracted institutions first, because it’s the closest thing to a commercial asset. PBSA was first delivered with a nominations agreement to universities, so it was, effectively, a long lease’ (Investor 5).

The certainty of income that comes with a nominations agreement applies primarily to the UK and might go some way to explaining the particular attraction of the UK to PBSA investors.

Pension funds typically form a partnership or joint venture with banks, private equity or a REIT when investing in student housing, for example, the partnership between the Dutch Pension Fund PGGM and UPP REIT or those between Canadian Pension Funds and various banks and Equity Funds. The overlap and inter-dependency of the various categories of investor is also exemplified by the takeover approach in July 2021 of CGP Student Living REIT, ‘one of London’s largest listed student accommodation groups’ by a consortium comprising the Dutch pension fund APG Asset Management (already CGP’s largest shareholder) and ‘the world’s largest equity fund’ Blackstone (C. C. Jones, Citation2021). This inter-relationship is most evident in the Investment Management category of investor. One investment manager mentioned their ‘small UK-specific residential fund, which is a pooled fund, largely for pension fund, local authority pension fund investors’ but that ‘the majority of our balanced funds would have student housing but otherwise not a lot of residential exposure’.

5.1 Investment timelines

The first developer/investor focusing specifically on PBSA in Europe was GSA, in its original incarnation as Unite. It was founded in 1991 in Bristol, UK, but expanded rapidly and listed on the London Stock Exchange in 2000. It created Europe’s largest unlisted specialised student housing investment vehicle, USAF, in 2006 and, through various portfolio acquisitions as well as many development projects, now operates in 55 cities around the world (Global Students Accommodation, Citation2021). Its brands include Urbanest, Uninest, and The Student Housing Company. As an example of its partnerships, in the early 2000s Unite formed a joint venture with the Singaporean Sovereign Wealth Fund, GIC, which was the latter’s entrance into the European PBSA market (Bouwmeister, Citation2019).

Interviewees were aware that Unite was an early provider of student accommodation and of its substantial expansion, such as its purchase of the Liberty Living portfolio in 2019.

‘Student was created by Unite as an investment product that didn’t really exist in the mainstream market’ (Analyst 3).

‘The student sector started off with the likes of Unite investing in it; they went out, recapitalised themselves, grew significantly and the early years of student accommodation were typified by direct contracts with universities, so you had a very steady and secure tenancy base’ (Investor 10).

Investor 12 described the entry and mode of operation of private equity investors into the UK PBSA market in the context of supply and demand:

“1) In 2010, the imbalance in supply/demand for PBSA student accommodation was so high, that rents were rising, creating an attractive yield premium for investors willing to own that risk class.

2) From the early 2010s banks started to be willing to lend for development of student accommodation.

3) Many value-add/opportunistic players saw this premium as attractive versus other quasi-residential assets classes, such as serviced apartments, with similar risk profiles, and so bought or built PBSA believing that the yield would fall once there was more confidence in the sector, with institutions wanting to invest.

4) Operators like CRM Students appeared to service this demand.

5) With professional operators in the market and many schemes underway, lenders became open to lending on PBSA, so availability of capital in the PBSA sector increased rapidly.

6) Schemes which were built and stabilised by the opportunistic/value-add players were then sold off to core players and institutions. Alternatively, institutions starting funding the platforms themselves at low rates of expected return (such as. IQ & Wellcome/Goldman Sachs; Urban Nest & M3 Capital Partners).

During this cycle, which lasted roughly 5–7 years (2010–2017), investment yields for PBSA almost halved, making early investors very healthy returns” (Investor 12).

Brookfield entered the UK PBSA market in 2016, at which point, according to the perception of Managing Partner Zachary Vaughan, student housing was not considered to be ‘an institutional-quality physical asset and … it was hard to find partners to aggregate portfolios and run them at scale’. Brookfield built their UK business ‘through development and acquisition’ then ‘used the expertise gained to expand into the continent’ (Brookfield Asset Management, Citation2021, p. 39).

In discussing the entry of private equity into the UK PBSA market, another interviewee described the approach taken by one of the key players: ‘to get a foothold in the UK market, start off with buying student accommodation … [They would] buy a run-down block of student accommodation and modernise it, and then they began some of their own developments’ (Analyst 6). As Bouwmeister (Citation2019) says, ‘there was a time when developers would create their own units and keep them as a long-term investment; that’s changed. You now see institutional investors buying these finished developments for their portfolios, as well as building their own’.

From we can see the year in which the key players entered the European PBSA markets. In general, their entry to the UK market preceded their activity in continental Europe, typically by around 5 years.

An early foray into the student housing sector in mainland Europe was the purchase of a 3-property portfolio in Germany in May and June 2010 by the European Residential Fund of Investment Manager Bouwfonds, which had been part of Rabobank since 2006, and had previously specialised in investment in car parks. Its European Residential Fund was created in 2007. In 2012, the fund added a student property in France, followed by two further French properties two years later. In 2013, Bouwfonds created a second European Student Housing Fund focused on ‘major European university towns and cities with a healthy housing market, principally in Germany and France, followed by the United Kingdom, the Netherlands and Scandinavia’ (Bouwfonds, Citation2013). Bouwfonds IM was acquired by Dutch Investment Manager Primevest Capital Partners in 2017 (Primevest, Citation2021). Primevest is (partly) owned by Commonwealth Investments, a multi-family office vehicle for high-net-worth individuals. Such changes of ownership, complex joint ventures and ownership structures are typical of investment management firms and illustrate the difficulties in untangling the nature of investment in PBSA and other real estate assets. Other examples of changes in ownership of PBSA investors include Patrizia’s acquisition of Rockspring at the end of 2017.

There have been relatively few transactions of student housing in Spain, the exception being the Resa portfolio. In July 2011, Mutua Madrilena (a Spanish Insurance Company), Lazora and Arta Capital (Spanish Equity Funds), and the Spanish Bank Banca March, purchased the Resa student housing portfolio from CDPQ (a Canadian Pension Fund) and a consortium of three Spanish Banks. The portfolio comprised 26 properties throughout Spanish university towns, including Seville, Bilbao, San Sebastian, Tarragona, Barcelona, Salamanca and Madrid. The portfolio was subsequently sold in September 2017 to the French Insurance Company Axa, the US Equity Fund Greystar and the Dutch Insurance Company Nationale Nederlanden, by which time it had grown to 37 properties.

The Netherlands was not an attractive destination for investment in student housing at the start of the decade. The Dutch Pension Fund PGGM had a successful partnership with the UPP REIT to develop and manage PBSA in the UK but was reticent about investing in the Dutch student housing sector in 2013 because at that time it was ‘heavily regulated and subsidised’ with ‘tight rent regulations [which] prevented investors earning market-based returns. The result was that investors struggled to find “economically sensible opportunities”’ (Primevest, Citation2021). However, in April 2015, a substantial portfolio transaction did take place in the Netherlands, with Woonstad Rotterdam acquiring 90 student housing properties from Vestia Groep. The properties ranged in size from 4 to 991 units, with an average of 65 units, and were all in the Rotterdam area.

During the three years from November 2015, a significant player in the Dutch student housing market has been the Belgian REIT Xior. Although it has invested in only around 20 properties in the Netherlands during that period, most comprise around 200–300 units and they are dispersed around Amsterdam, Utrecht, The Hague, Eindhoven, and Rotterdam.

The peak year for investment in PBSA was 2015, and portfolio transactions such as the Nido, Liberty Living and the Rotterdam portfolio sale account for much of the activity. There were also sales of small portfolios in Germany that year, as well as sales of numerous individual student properties and larger portfolios in the UK, such as the 13 property Westbourne Student Housing Portfolio bought by Goldman Sachs and Greystar from Threesixty Developments, with Bank of America acting as lender for the purchase.

Consolidation and acquisition of portfolios has been a key driver in investment volumes. Nido, Liberty Living, Resa, iQ Student Housing and Chapter are all portfolios that have changed hands, in some cases more than once, for substantial amounts of money. Almost all types of investor have had some involvement in one or more of these transactions.

5.2 Investment locations

Derived using RCA data, for towns and cities with more than 500 PBSA units (5000 for the UK), shows the number of PBSA units developed or transacted. It is apparent that investment in European PBSA is concentrated in the main towns and cities, however it has also extended to regional markets with high-quality universities, concurring with the findings of Newell and Marzuki (Citation2018, p. 526).

Table 3. Cities with more than 500* PBSA units transacted to 31/12/2020 (Source: RCA)

The preponderance of the UK as the recipient of PBSA investment is clear from the table, with the country’s largest cities predominating. Major institutional landlords favour locations close to higher ranked ‘Russell Group’ universities. One interviewee, describing his firm’s entry into PBSA development, explained the importance of proximity to the university, or preferably, for direct-let, to several universities: ‘My firm started with Glasgow. We found a hotel within 200 yards of three universities, bought it and converted it to 140-bed, direct-let, boutique accommodation’ (Developer 2). A prime location on this basis would be Manchester, a city with more than 100,000 students in five universities. Student Castle developed ‘the tallest student accommodation in Europe’ in the city (Student Castle, Citation2020) and has submitted plans to build a 55-storey, 165 m tall tower to accommodate students primarily, but also start-up businesses.

According to Bouwmeister (Citation2019), ‘Singaporean players’ invested over £1bn in UK student housing assets since between 2016 and 2018, ‘buying up properties everywhere from Bristol and Brighton to Huddersfield, Sheffield and Leeds’. Brighton is also cited as a favoured destination by Brookfield Vice-President Jennie Wong, ‘because it has the highest ratio of students to purpose-built student accommodation beds, eight to one … and the council there is also very supportive, and wants to take students out of the private housing market’ (Phillips, Citation2019b). Brookfield’s Student Roost ‘agreed a £70 million forward-funding transaction to acquire two development opportunities in York and Bristol, which will provide 660 student beds when completed in time for the 2022–23 academic year’ (Brookfield Asset Management, Citation2021).

Analysis of RCA data reveals that there are 50 towns and cities in the UK with transactions of more than 1000 PBSA units. However, in some locations the PBSA market is undoubtedly oversupplied. ‘When Unite sold stakes in properties in five locations including Plymouth, Birmingham and Sheffield, it accepted a price marginally below book value’ in order to ‘[dispose] of assets with lower than average growth prospects and reinvest into developments increasingly focusing on high and mid-ranked universities’ (Hale & Evans, Citation2019). Interviewees also commented about location-specific factors, such as the proximity of low-rent houses of multiple occupation that make certain places unviable for PBSA development or investment: ‘If you’re competing with low-cost PRS in an area, it’s difficult to make the finances of new-build, high-spec PBSA work’ (Developer 7). There are several other examples of failed PBSA schemes in the UK (Phillips, Citation2019a), further corroboration of interviewees’ suggestions that some parts of the market in the UK could well be oversupplied, particularly in the wake of the pandemic (Thame, Citation2021).

Considering mainland Europe, Greystar has invested heavily in PBSA in France, favouring particularly the Paris area, ‘with a pipeline today of 5,000 beds in the region’, but also ‘cities like Toulouse and Marseilles, which are big student hubs’ (Smyth, Citation2020). Towns near the top of , such as Palaiseau, Bagnolet and Cergy, are all in the Isle de France (Greater Paris region). In Spain, the Resa portfolio has nearly 10,000 beds across 19 Spanish cities, and comprises 10% of Spain’s PBSA (AXA IM – Real Assets, Citation2017). According to JLL (Citation2018), until around 2016 ‘the focus was on Madrid and Barcelona’, but has subsequently turned ‘towards undersupplied regional cities such as Valencia, Granada, Malaga, Seville, Pamplona and Salamanca’. Development and investment in Germany does appear to be heavily focused on the main cities, while according to Wilberts et al. (Citation2019 p. 8),‘Dutch cities with the largest shortfalls in student accommodation are Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Utrecht and The Hague’.

5.3 Investment hold periods

How long an investor holds each PBSA property or portfolio is affected by the nature of the property and the type of investor. Where PBSA is developed in conjunction with a university, typically building on university-owned land, a common arrangement is that the developer has a lease on the property of 35–50 years, during which time they receive the rental income, and at the end of which, the property reverts to the university. There is usually a nominations agreement in place, under which the university guarantees that their students will rent a certain number of rooms. This arrangement has proved beneficial to such developers during the Covid pandemic. ‘We have a 10-year nominations agreement before reverting to direct-let. Without this, Covid would have been disastrous’ (Developer 2). It is beneficial, too, for the university. ‘It is an off-balance sheet proposition which means that, effectively, a university could be getting another 2,000 rooms built, brand new, which are marketed as the university’s rooms because that’s one of the conditions, but they’re not having to pay for them, they’re not getting any revenue from them, but they are getting an up-front capital receipt and at the end of that 50 years, that asset would revert to their ownership’ (Developer 4).

Where an investor forward-funds a direct-let student block (paying for the construction and acquiring the property on completion), the hold period will be determined by the investor’s strategy. Pension funds, that need to match rental income to liabilities, are likely to benefit from keeping the property while occupancy remains high but might need to sell in an oversupplied market. As Investor 6 explained “Pension funds will always invest in a different cycle from that of private investors and equity funds and what you tend to get, if you were to draw it out, it would look a bit like a helix or an oscillation, so whilst pension funds are doing this kind of wave, you’ve got the opposite wave going on with the private sector. Pension funds buy products when it looks like the market’s going up and sell them when it looks like the market’s going down because that’s how pensions operate; they want income-producing assets that are going up in value and they want to shed them when they’re not producing income or they’re going down in value.

Then, you look at where private investment comes in and it’s countercyclical in that respect, so when the value’s going down, if you’re comparatively cash rich and you don’t have to answer to a board or a charities commission … you can pile in and buy at rock bottom prices and then the value goes up and you offload to a pension fund and you’ve made your money. Then it all happens over again, so you’ve got the private money, in some respects, that will invest countercyclically, but then you’ve also got tiered risk money” (Investor 6).

The idea that Private Equity invests for a finite period, with confidence that it can exit by selling to a willing buyer, was a frequent theme amongst interviewees.

‘The private equity, opportunistic “high-risk guys” said, “let’s get in on the act”. Their model was to buy up buildings to convert, then sell within 5 years’ (Investor 12).

‘PE money targeting the space, ultimately, that has to look for an exit’ (Consultant 4) and such funds are building and assembling portfolios of PBSA ‘for the underlying core investor to, hopefully, take it out at the back end’ (Analyst 7).

For the UK student housing REITs such as Unite, Empiric and UPP, at least 75% of net profits must come from the REIT’s rental business; at least 75% of the assets must be used in the rental business; and property financing costs cannot exceed 80% of the property’s profits (Moss, Citation2018). Tax liabilities arise if these rules are violated. The main REIT players (Unite, UPP, Xior etc.) have been accumulating properties, either by development or by acquisition, scaling up their portfolios and building brand recognition for their platforms. They sell only properties that are underperforming or not conforming to the overall strategy (Hale & Evans, Citation2019) or when under pressure to liquidate assets as a result of financial difficulties such as breaching covenants, excessive expenses and high vacancy (Citywire, Citation2017; Hale & Evans, Citation2019).

Because PBSA is a relatively new sector, it is not possible to assess hold periods over the long term, but portfolios of PBSA, typically owned by private equity funds or investment management firms, have changed hands over the past decade, in some cases more than once. The period of five years referred to by several interviewees concurs with the frequency with which the large PBSA portfolios have typically traded, for example, Nido (initially created in 2006) being sold in May 2012, March 2015 and February 2021; and Liberty Living in March 2015 and November 2019. Because the European PBSA market has only evolved more recently, there have been fewer opportunities for repeat sales, so the secondary market is certainly less well established. There have been few transactions between investors in Germany, France and the Netherlands, but the Resa portfolio of Spanish student housing has already changed hands twice, in July 2011 and September 2017.

5.4 Portfolio diversification

Diversification into a variety of asset classes and sectors has been all the more important for investors since the Global Financial Crisis (Aalbers, Citation2019). From , it is apparent that although the volume of investment by global equity funds, investment management firms, insurance companies, pension funds and sovereign wealth funds might be large, as a proportion of their overall property holdings, their investment in European PBSA is typically only around 2%. In the case of Blackstone, two-thirds of investments are in asset classes such as hedge funds, credit, insurance, life sciences, and infrastructure. The company’s ‘real estate portfolio includes logistics, rental housing, office, hospitality and retail properties around the world’ (Blackstone, Citation2021) and includes opportunistic acquisitions, core+ assets in ‘global gateway cities’, and real estate debt loans and securities. Thus, Blackstone exhibits wide-ranging diversification in terms of its portfolio of asset classes, sectors, and geographical dispersal. Large global firms that want to borrow to fund new development have access to sources of finance at low interest rates; Blackstone, for example, has loans from Citi Real Estate Funding, Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, and Wells Fargo banks.

As well as their substantial investments in other asset classes, some of these major players do invest extensively in PBSA globally, giving them expertise, brand awareness and economies of scale. For example, Greystar ‘has more than 660,000 units and student beds under management in more than 50 cities around the world’ and in 2020 it formed ‘a partnership with Ivanhoé Cambridge Holdings UK and Bouwinvest Real Estate Investors to invest €1bn in purpose-built student accommodation in the Greater Paris Region’ (Smyth, Citation2020). Greystar has also used its PBSA investment as a springboard to diversify into the UK Build-to-Rent (BTR) sector, building on its extensive experience of U.S. Multi-family investment (Brill & Özogul, Citation2021). Conversely, the specialist European PBSA providers diversify only by location, not sector or asset class. They might procure an office block or hotel, for example, but this is with the intention of redeveloping the building into student accommodation.

One interesting hybrid model is that of the privately-owned, private equity-backed ‘The Student Hotel’ which operates multiple properties in European cities and serves both students and other short stay occupiers (Savills, Citation2019a). The ability to repurpose student housing into co-living or BTR reduces risks for investors and lays the foundation for future diversification (Rosser, Citation2021).

6. Discussion and conclusion

Student accommodation is an asset class that is accessible to investors at a wide range of scales. Funds have been created with the explicit remit of enabling individuals to invest in new PBSA development (Hickey, Citation2020). Individuals can invest in shares in listed PBSA REITs and REOCs. It is also possible to invest in a single unit of PBSA, receiving the rent as income, and any capital appreciation when the unit is sold, in much the same way that people have invested in buy-to-let houses of multiple occupation for students to rent. RCA, which records only transactions in excess of €5 M, has details of 600 different investors in UK student housing, 100 investors in French student housing, 210 in German, 49 in Spain, and 141 investors in student housing in The Netherlands.

Institutional investors largely turned to PBSA following the Global Financial Crisis in their search for yield and portfolio diversification. Those that have developed or acquired PBSA in continental Europe mostly preceded that activity with investment in UK PBSA around five years earlier. Currently, few investors in PBSA invest in multiple European countries, but the number of transactions and the amount of investment is increasing. This trend is likely to accelerate as the super-normal profits of UK PBSA are abating, with prices increasing, yields declining, and opportunities getting fewer.

Until now, the UK has attracted substantial cross-border investment, while in continental Europe, cross-border investment has tended to comprise joint ventures with a local partner or transactions between near neighbours. As institutional investors have increasingly been forward-funding or developing their own PBSA, the one category of investor whose presence is diminishing is the small-scale private developer. While opportunities for such developers do remain, the current climate is certainly challenging. Specific issues include shortages of labour and construction materials in the wake of the Covid pandemic, exacerbated in the UK by the economic and political shock of Brexit.

Equity Funds typically hold their portfolios for around five years, and these form only a tiny proportion of such investors’ assets. PBSA specialists, mainly REITs, have accumulated substantial portfolios, and the rental income should satisfy the requirements of the REIT structure. However, their lack of diversification leaves REITs vulnerable to local over-supply or more widespread reduction in demand for student accommodation, for example, as a result of the pandemic. Nevertheless, PBSA can in theory be re-purposed for co-living or other residential accommodation, subject to meeting planning requirements, as the approach of The Student Hotel in continental Europe demonstrates.

Investors certainly appear to have confidence in the European PBSA sector, with other substantial portfolio transactions since Blackstone’s record-breaking UK purchase in May 2020. This secondary market is no longer confined to the UK. Although PBSA landlords lost income through the 2020/21 academic year by having to give rent rebates, according to Brookfield Asset Management (Citation2021, p. 38), ‘European student housing has demonstrated its resilience throughout the pandemic and remained in demand for institutional capital’. The pandemic has adversely affected the retail and office sectors, and investors have turned to ‘Beds, Meds and Sheds’Footnote2 (Property Forum, Citation2021) in search of income and/or capital appreciation. While demand for a European university education from overseas students remains strong, and these universities are encouraged to expand, investors’ confidence in European PBSA appears justifiable based on assumptions of risk and return.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Danielle Sanderson

Danielle Sanderson read physics at Oxford University and worked in Computing and Operational Research before becoming a Researcher and Consultant for RealService, as well as competing as an International Athlete. She was awarded her Doctorate from Henley Business School in 2016 and is now an Associate Professor in Real Estate at The Bartlett School of Planning, University College London. Danielle’s research has primarily focused on aspects of Landlord – Tenant Relations, Property Management, and Real Estate Investment in the retail, office and residential sectors.

Sara Özogul is Assistant Professor in Urban Planning at the University of Groningen, in the Faculty of Spatial Sciences. She was previously a Postdoctoral Researcher and Project Manager of the WHIG project in Amsterdam. Her background is in Planning, Urban Studies and Interdisciplinary Social Sciences with a focus on Human Geography. She completed her PhD in Planning at the University of Amsterdam and her MSc in Urban Studies at University College London Her research centres around the link between planning, regulation and (residential) property market dynamics.

Danielle and Sara are co-investigators on the ORA-funded Project What Is Governed in Cities: Residential Investment Landscapes and the Governance and Regulation of Housing Production. This is a collaboration between colleagues in London, Paris and Amsterdam to investigate the relationship between public and private actors involved in the production of housing.

Notes

1. RCA was acquired by MSCI in August 2021

2. residential, healthcare/life-science, and warehousing/logistics

References

- Aalbers, M. B. (2019). Financial geographies of housing and real estate. Financial Geography II, 43(2), 376–387. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132518819503

- AXA IM - Real Assets. (2017). Acquisition of Spain’s largest student accommodation portfolio. Company Website. https://realassets.axa-im.com/en/content/-/asset_publisher/x7LvZDsY05WX/content/acquisition-of-spain-s-largest-student-accommodation-portfolio

- Bentham, Z. (2021). Investing sustainably through a workplace pension - Aviva. Company Website. Retrieved from September 8, 2021, from https://www.aviva.co.uk/business/business-perspectives/expert-view-hub/pensions-and-passions/

- Blackstone. (2021). Blackstone - What we do. Company Website. https://www.blackstone.com/

- Bouwfonds. (2013). Bouwfonds REIM launches European student housing fund. Company Website. Retrieved from April 18, 2021, from http://www.bouwfondsim.com/bouwfonds-reim-launches-european-student-housing-fund/

- Bouwmeister, O. (2019). Student accommodation: Will Europe overtake UK? Company Website. Retrieved from April 6, 2021, from https://www.vistra.com/insights/student-accommodation-will-europe-overtake-uk

- Brill, F., & Özogul, S. (2021). Follow the firm: Analyzing the international ascendance of build to rent. Economic Geography, 97(3), 235–256. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2021.1931108

- Brookfield Asset Management. (2021). Full speed ahead - Covid accelerates pace of change: Firm foundations for European student housing (Issue June). https://www.brookfield.com/sites/default/files/2021-06/PERE_BrookfieldonEuropeanStudentHousing_June2021.pdf

- Byrne, P., Jackson, C., & Lee, S. (2013). Bias or rationality? The case of UK commercial real estate investment. Journal of European Real Estate Research, 6(1), 6–33. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/17539261311312960

- Capape, J. (2019). The future of PBSA. Company Website. Retrieved from August 23, 2021, from https://www.theclassfoundation.com

- CBRE. (2019). United States Student Housing 2019.

- CBRE. (2020). SECTOR UPDATE: PURPOSE BUILT STUDENT ACCOMMODATION (PBSA). https://www.cbre.com/

- Citywire. (2017). Empiric student property dives on dividend cut. Morningstar. Retrieved from July 11, 2021, from https://citywire.co.uk/investment-trust-insider/news/empiric-student-property-dives-on-dividend-cut/a1071873

- Cushman, & Wakefield. (2021). UK student accommodation report 2020/21. https://f.datasrvr.com/fr1/221/77905/UK_Student_Accommodation_Report_2021.pdf

- De Bruin, A., & Dupuis, A. (2000). Constrained entrepreneurship: An interdisciplinary extension of bounded rationality. Journal of Interdisciplinary Economics, 12(1), 71–86. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/02601079X00001200104

- Devaney, S., & Scofield, D. (2017). Do Foreigners’ pay more? The effects of investor type and nationality on office transaction prices in New York City. Journal of Property Research, 34(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09599916.2017.1299197

- Espinoza, J. (2018, February 12). Sovereign wealth funds quadruple investment in student housing. The Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/8fe556e6-0dba-11e8-839d-41ca06376bf2

- Eurostat. (2020). Mobile students from abroad enrolled by education level, sex and country of origin. Eurostat, the Statistical Office of the European Union. https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=educ_uoe_mobs02&lang=en

- Fiorentina, S., Livingstone, N., & Short, M. (2020). Financialisation and urban densification: London and Manchester’s niche student housing markets. Regional Studies Magazines. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13673882.2020.00001079

- Fixsen, R. (2018). Impact investing: Beyond the financial return. IPE International Publishers Ltd. Retrieved from August 9, 2021, from https://realassets.ipe.com/investment-/impact-investing-beyond-the-financial-return/10023546.article

- Forrest, H., Denbee, R., Kingham, R., & Kingdom, J. (2019). UK student housing report. Jones Lang LaSalle, (1), 1–19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429346750-14

- French, N., Bhat, G., Matharu, G., Guimarães, F. O., & Solomon, D. (2018). Investment opportunities for student housing in Europe. Journal of Property Investment and Finance, 36(6), 578–584. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JPIF-08-2018-0058

- Gallent, N., Hamiduddin, I., Juntti, M., Livingstone, N., & Stirling, P. (2018). New money in rural areas Assessing the impacts of investment in rural land assets. RICS (The Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors). https://www.rics.org/uk/news-insight/research/research-reports/new-money-in-rural-areas-assessing-the-impacts-of-investment-in-rural-land-assets/

- Gilmore, G. (2019). Residential investment report 2019. Knight Frank. https://content.knightfrank.com/research/1769/documents/en/residential-ivestment-report-2019-6404.pdf

- Global Students Accommodation. (2021). GSA- our story. Company Website. https://www.gsa-gp.com/about/#our-story

- Greater London Authority. (2021). The London plan 2021 (Issue March, pp. 1–542). GLA. www.london.gov.uk

- Hale, T., & Evans, J. (2019, September 15). Higher education: Is Britain’s student housing bubble set to burst? The Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/770992fc-d3d6-11e9-a0bd-ab8ec6435630

- Hickey, S. (2020). New PBSA funding platform launches with £100m commitment. Property Week. https://www.propertyweek.com/finance/new-pbsa-funding-platform-launches-with-100m-commitment/5109053.article

- Higgins, D. (2015). Defining the three Rs of commercial property market performance: Return, risk and ruin. Journal of Property Investment and Finance, 33(6), 481–493. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JPIF-08-2014-0054

- Hochstenbach, C., Wind, B., & Arundel, R. (2020). Resurgent landlordism in a student city: Urban dynamics of private rental growth. Urban Geography, 1–23. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2020.1741974

- JLL. (2018). Investors wake up to Spain’s student bed opportunity. The Investor. https://www.theinvestor.jll/news/spain/alternatives/investors-wake-spains-student-bed-opportunity/

- JLL. (2019). Student housing in Spain, an evolving sector. https://Www.Jll.Es/. https://www.jll.es/es/analisis-y-tendencias/informes/student-housing-an-evolving-sector

- Jones, C. (2021, July 3). Student housing group reveals takeover approach. The Times Newspaper, 53. hhttps://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/student-housing-group-reveals-takeover-approach-t7863f8c7

- Jones, S. (2020). Student accommodation - Weathering the storm. Cushman & Wakefield. Retrieved from December 31, 2020, from https://www.cushmanwakefield.com/en/united-kingdom/insights/covid-19/student-accommodation

- Keogh, G., & D’arcy, É. (1994). Market maturity and property market behaviour: A European comparison of mature and emergent markets. Journal of Property Research, 11(3), 215–285. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09599919408724118

- Knight Frank. (2019). GLOBAL STUDENT PROPERTY 2019. https://content.knightfrank.com/research/1775/documents/en/global-student-property-report-2019-may-2019-6426.pdf

- Leyshon, A., & French, S. (2009). ‘We all live in a Robbie Fowler house’: The geographies of the buy to let market in the UK. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 11(3), 438–460. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-856X.2009.00381.x

- Lizieri, C. M. (2003). Occupier requirements in commercial real estate markets. Urban Studies, 40(5–6), 1151–1169. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098032000074353

- Magalhães, C. S. D. (2001). International property consultants and the transformation of local markets. Journal of Property Research, 18(2), 99–121. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09599910110014156

- Mallinson, S. (2020). Surveying student housing investment as Covid clouds demand. Real Capital Analytics.

- McAllister, P., & Nanda, A. (2016). Does real estate defy gravity? An analysis of foreign real estate investment flows. Review of International Economics, 24(5), 924–948. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/roie.12228

- McCann, L., Hutchison, N., & Adair, A. (2020). Student residences: Time for a partnership approach? Journal of Property Investment & Finance, 38(2), 128–146. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2021.1931108

- McIntosh, W., Fitzgerald, M., & Kirk, J. (2017). Non-traditional property types: Part of a diversified real estate portfolio? The Journal of Portfolio Management, 43(6), 62–72. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3905/jpm.2017.43.6.062

- Moss, A. (2018). Chapter 10: Europe. In D. Parker (Ed.), The routledge REITs research handbook (pp. 191–213). Routledge.

- Murray-West, R. (2021). Guide to ethical pensions. The Times Newspaper. Retrieved from September 8, 2021, from https://www.thetimes.co.uk/money-mentor/article/guide-to-ethical-pensions/

- Newell, G., & Marzuki, M. J. (2018). The emergence of student accommodation as an institutionalised property sector. Journal of Property Investment and Finance, 36(6), 523–538. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JPIF-01-2018-0007

- Osborne Clarke. (2017). Income Strips: De-risking the deal. Osborne Clarke Insights. https://www.osborneclarke.com/insights/income-strips-de-risking-the-deal/

- Owens, C. (2017). Using off-balance sheet income strips to deliver new-build student accommodation. Pinsent Masons. Retrieved from December 13, 2020, from https://www.pinsentmasons.com/out-law/analysis/using-off-balance-sheet-income-strips-to-deliver-new-build-student-accommodation

- Özogul, S., & Tasan-Kok, T. (2020). One and the same? A systematic literature review of residential property investor types. Journal of Planning Literature, 35(4), 475–494. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0885412220944919

- Phillips, M. (2019a). £100M Student accommodation carve-up company is 1 of 2 to go bust. Bisnow. Retrieved from April 6, 2021, from https://www.bisnow.com/london/news/student-housing/exclusive-distress-comes-to-student-sector-as-two-schemes-go-into-administration-10756700768

- Phillips, M. (2019b). Big beasts see student housing as defensive and developing. Bisnow. Retrieved from December 27, 2020, from https://www.bisnow.com/london/news/student-housing/big-beasts-see-student-housing-as-defensive-and-developing-99631

- Portlock, R., & Mansley, N. (2021). Large scale UK residential investment : Achieving market maturity (Issue March). Investment Property Forum (IPF).

- Primevest. (2021). Primevest capital partners/history. Company Website. Retrieved from April 22, 2021, from https://www.primevestcp.com/about-us/funds/date

- Property Forum. (2021). Sheds, beds & meds will be investment winners in 2021. Investment. https://www.property-forum.eu/news/sheds-beds-meds-will-be-investment-winners-in-2021/7974

- Pyle, A. (2018). Entering the mainstream: A review of alternative real estate (Issue June). Consultancy Firm KPMG. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-00599-3_6

- Revington, N., & August, M. (2019). Making a market for itself: The emergent financialization of student housing in Canada. Environment and Planning A, 52(5), 856–877. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X19884577

- Revington, N., Moos, M., Henry, J., & Haider, R. (2020). The urban dormitory: Planning, studentification, and the construction of an off-campus student housing market. International Planning Studies, 25(2), 189–205. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13563475.2018.1552565

- Rogers, D., & Koh, S. Y. (2017). The globalisation of real estate: The politics and practice of foreign real estate investment. International Journal of Housing Policy, 17(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2016.1270618

- Rosser, E. (2021). Student operator expands with BTR business. Estates Gazette. https://www.egi.co.uk/news/student-operator-expands-with-btr-business/

- Savills. (2009). Spotlight on student housing (Issue May). https://pdf.euro.savills.co.uk/uk/spotlight-on/spotlight-on-student-housing—may-2009.pdf

- Savills. (2013). Spotlight European student housing. https://www.savills.co.uk/insight-and-opinion/#Research

- Savills. (2017). Spotlight student housing in the Netherlands. https://pdf.euro.savills.co.uk/the-netherlands/commercial—dutch-other/spotlight-on-student-housing-in-the-netherlands—june-2017.pdf

- Savills. (2018). WORLD STUDENT The global search for scale. https://pdf.savills.asia/selected-international-research/201710-world-student-housing-en.pdf

- Savills. (2019a). Global student housing investment. http://pdf.euro.savills.co.uk/global-research/global-student-housing-investment-2019.pdf

- Savills. (2019b). Savills reveals three quarters of retail landlords are considering repurposing projects. Savills News: Re: ImaginingRetai. https://www.savills.co.uk/insight-and-opinion/savills-news/289941/savills-reveals-three-quarters-of-retail-landlords-are-considering-repurposing-projects

- Shelton, A. (2019). Student housing Netherlands - 2019 operation and/or real estate? - The class of 2020. CBRE. https://www.readkong.com/page/student-housing-netherlands-2019-operation-and-or-real-2599341

- Smyth, S. (2020, July 13). Greystar’s head of France on why Paris is the next big thing for student housing. CoStar. Retrieved from April 3, 2021, from https://www.costar.com/article/1940529287/greystars-head-of-france-on-why-paris-is-the-next-big-thing-for-student-housing

- Student Castle. (2020). A track record for unique student accommodation across the UK. Student Castle. https://www.studentcastle.co.uk/our-story/

- Tasan-Kok, T., & Özogul, S. (2021). Fragmented governance architectures underlying residential property production in Amsterdam. Environment and Planning A, 53(6), 1314–1330. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X21996351

- Thame, D. (2021). Up, down, shake it all around: 3 things we learned about UK’s regional big city property markets. Bisnow. Retrieved from April 5, 2021, from https://www.bisnow.com/manchester/news/commercial-real-estate/up-down-shake-it-all-around-five-things-we-learned-about-uks-big-city-property-markets-107584

- The Glide Group. (2019). The rise and rise of purpose-built student accommodation in Europe. https://glidegroup.co.uk/news-insight/2019-07-24-the-rise-and-rise-of-purpose-built-student-accommodation-in-europe

- The Unite Group PLC. (2016). Amendments to articles of association and notice of general meeting in connection with REIT conversion. https://www.unite-group.co.uk/sites/default/files/2017-03/real-estate-investment-trust-circular-notice-2016.pdf

- Waldron, R. (2018). Capitalizing on the state: The political economy of Real Estate Investment Trusts and the ‘Resolution’ of the crisis. Geoforum, 90, 206–218.

- Wijburg, G., Aalbers, M. B., & Heeg, S. (2018). The financialisation of rental housing 2.0: Releasing housing into the privatised mainstream of capital accumulation. Antipode, 50(4), 1098–1119. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12382

- Wilberts, B., Schellekens, M., & Kleemans, J. (2019). Student housing: From niche specialism to full-fledged segment. consultancy Savills. https://pdf.euro.savills.co.uk/the-netherlands/commercial—dutch-other/spotlight-student-housing—the-netherlands—2019.pdf

- Xior Student Housing. (2021). Annual Financial Report ’20. https://www.xior.be/uploads/inv_year_reports/8/Xior_Jaarverslag_EN_2020.pdf

- Young, F. (2012, November 6). Student housing has emerged as a mainstream global asset class worth an estimated US$200 billion. Washington, DC: Targeted News Service. https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.ucl.ac.uk/newspapers/student-housing-has-emerged-as-mainstream-global/docview/1164704887/se-2?accountid=14511