ABSTRACT

Regulations to contain the spread of COVID-19 have affected corporations, institutions, and individuals to a degree that most people have never seen before. Information systems researchers have initiated a discourse on information technology’s role in helping people manage this situation. This study informs and substantiates this discourse based on an analysis of a rich dataset: Starting in March 2020, we collected about 3 million tweets that document people’s use of web-conferencing systems (WCS) like Zoom during the COVID-19 crisis. Applying text-mining techniques to Twitter data and drawing on affordance theory, we derive five affordances of and five constraints to the use of WCS during the crisis. Based on our analysis, our argument is that WCS emerged as a social technology that led to a new virtual togetherness by facilitating access to everyday activities and contacts that were “locked away” because of COVID-19-mitigation efforts. We find that WCS facilitated encounters that could not have taken place otherwise and that WCS use led to a unique blending of various aspects of people’s lives. Using our analysis, we derive implications and directions for future research to address existing constraints and realise the potentials of this period of forced digitalisation.

SPECIAL ISSUE EDITORS:

1. Introduction

Web-conferencing systems (WCS) like Zoom and Microsoft Teams have been around for some time. First adopted in the business world to facilitate professional interactions between companies and distributed work (Wilcox, Citation2000), WCS uses include distance education (e.g. Mupinga, Citation2005), telehealth (e.g. Brecher, Citation2013), and more recently personal use, such as by long-distance families (e.g. Follmer et al., Citation2010; King-O’Riain, Citation2015). Despite radical improvements in the infrastructure that underlies WCS, such as faster internet connections and the widespread use of mobile devices, persistent technical issues have led to every second videoconference starting with “Can you hear me?” rather than “Hi, how are you?” In addition, while it approximates face-to-face interactions, WCS has to some extent continued to be perceived as a “second class” medium (Larsen, Citation2015), which created barriers to their widespread implementation and use.

To contain the spread of COVID-19, governments around the world imposed regulations to restrict physical meetings, mobility, and public life in general. While most people did not contract the infection, their lives were dramatically disrupted as the lockdown locked away their everyday contacts and activities. In this extreme situation, institutions and individuals alike responded by switching quickly from physical and location-dependent interactions to virtual interactions. Soaring download numbers and a higher number of daily meeting participants than ever before point to the central role of WCS like Zoom in this transformation (Reuters, Citation2020). The use of WCS doubled between 27 March and May 31 2020, rising to 24 percent of U.S. households (Consumer Technology Association, Citation2020). Not surprisingly, the trend towards working from home whenever possible contributed to this increase (Clutch.co, Citation2020), but people also started to use WCS to support the everyday activities related to school, communities, friends, and families.

Against the background of drastic and widespread changes in people’s digital practices, this paper explores people’s use of WCS during the COVID-19 crisis to explain the unique role of technology during this crisis and derive recommendations for its use and further development. To this end, we analysed Twitter communications about some of the WCS used most often (e.g. Zoom and Microsoft Teams) that were generated during the lockdown period by performing topic modelling on a dataset of about 3 million tweets posted from March 23 2020 to June 14 2020. Drawing on affordance theory, we identify affordances and constraints arising from the use of WCS during the COVID-19 crisis.

The lockdown forced people to think about how to live their everyday lives while keeping their distance from one another. Our study documents how people discovered new affordances in an existing technology that helped them respond to the crisis as WCS emerged as a standard communication channel that supported interactions pertaining to all areas of life. Our findings indicate that WCS afforded a new virtual togetherness, new shared and synchronous social activities and events, and meetings that could not have taken place otherwise. We also identify constraints that arose from the unexpected and unconditional digitalisation of life, such as an increased exposure of people’s private living space. From our analysis we derive implications for Information Systems (IS) design and topics for future research. Beyond helping to address the challenges inherent in the COVID-19 crisis, we hope that this research can contribute to framing this “forced digitalisation” an opportunity to explore new digital practices that are worthwhile and are here to stay.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. The next section provides an overview of WCS and affordance theory. Then we report on the collection and analysis of our dataset, and present and discuss our findings. The article concludes with a discussion of the role of technology during the COVID-19 crisis and directions for future research.

2. Research background

This section first provides an overview of WCS and prior work on its use. This stream of research generally guides our data collection and provides a foundation for discussing our results. We then introduce key concepts of affordance theory, which we employ as a theoretical lens in our study, and report on the use of affordance theory in IS research.

2.1. Web-conferencing systems

WCS are general-purpose systems that facilitate virtual meetings among participants over the internet. WCS’s predecessors include personal videoconferencing applications like the “Picturephone”, which was rolled out in the 1960s, room-based group videoconferencing systems, and desktop videoconferencing (Wilcox, Citation2000). Today’s WCS (or meeting solutions) are communication and collaboration tools that can be accessed from desktop and mobile devices and are available on various platforms. WCS commonly support audio and video calls, messaging, content- and screen-sharing, and meeting recordings (Fasciani et al., Citation2019). They may be used for one-to-one or group calls, webinars, and webcasts. Microsoft Teams and Zoom meeting solutions are amongst the WCS used most often.

WCS are used in various contexts that are characterised by physical distance. Given the high investment in terms of hardware and infrastructure required set up videoconferencing solutions in the early days, such systems were first adopted by companies to facilitate business-to-business interactions and later on the work of distributed teams in an increasingly globalised world (Olson et al., Citation2012; Smith & McKeen, Citation2011). Soon after, videoconferencing was adopted to facilitate distance learning (e.g. Mupinga, Citation2005) and the delivery of health care services (Wilcox, Citation2000). More recently, readily available infrastructure, devices, and software solutions have contributed to videoconferencing’s becoming a social phenomenon (Geenen, Citation2017) by, for instance, helping members of long-distance families keep in touch (Follmer et al., Citation2010; King-O’Riain, Citation2015). Now video chatting increasingly replaces phone calls, especially amongst Millennials (Grech, Citation2019).

Across these and other contexts, technologies like WCS provide access to distant resources by bridging geographic and social distance. Because of its synchronicity and superior ability to convey verbal and non-verbal cues in comparison to other media, videoconferencing is perceived to be the closest available technology to a real-life interaction (Dennis & Valacich, Citation2008; Dennis & Valacich, Citation1999). In the business context, the use of video can facilitate knowledge-sharing and trust-building between distant partners (Zander et al., Citation2013) and is the preferred medium for transmitting complex information (Huysman et al., Citation2003; Sarker & Sahay, Citation2003). On the other hand, videoconferencing’s affordance of conveying visual cues may cause some users to avoid it if they feel monitored or are uncomfortable being viewed (Webster, Citation1998). With regards to private interactions, such as those among transnational family members, video calls enhance the sense of togetherness by facilitating the sharing of daily routines. Video calls are also a more natural communication medium than voice- or text-only forms of communication for children who want to “show and tell” at the same time (Judge & Neustaedter, Citation2010).

Despite technology’s affordance of creating (social) presence, physical distance still tends to be perceived as a barrier to effective communication, collaboration, and establishment of trust (Hacker et al., Citation2019). In addition, while technology has made the world smaller, it has not led to the “death of distance” (Cairncross, Citation1997), as people still have stronger relationships with those who are physically proximate (e.g. McKenna & Bargh, Citation2000). Hence, even though technology enables communication and collaboration in distributed settings, it can address the “problem of distance” only to a finite extent (Hafermalz & Riemer, Citation2016b).

During the COVID-19 crisis, we have seen a remarkable uptake of WCS around the world. Taking the example of Zoom, the number of daily meeting participants went up from about 10 million in December 2019 to 200 million in March 2020 (Reuters, Citation2020). This increased demand by a much broader base of users that started to use WCS in unexpected ways revealed issues in existing solutions regarding security, for example, and presented new requirements (O’Flaherty, Citation2020b). Vendors of WCS were quick to react by changing their pricing schemes, lifting the 40-minute meeting limit on basic accounts for schools (Zoom), and adding new features, such as customised video backgrounds and the ability to raise a virtual “hand” in a meeting (Microsoft Teams). Prior work in the field of crisis informatics shows how the use of technology changes in the aftermath of extreme events and how existing tools evolve into something else. For instance, Twitter, which is usually used for communicating and sharing information, emerged as a tool for collective participation and coordination in responding to a natural disaster, that is the Thailand flooding 2011 (Leong et al., Citation2015) and a tool for collective sense-making after a terrorist attack on the Berlin Christmas market (Fischer-Preßler et al., Citation2019). The increase in the number of users and the release notes of vendors of WCS suggest that WCS have played a unique role in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. In this paper, we seek to clarify this role by drawing on affordance theory.

2.2. Affordance theory

Gibson (Citation1977) pioneered the concept of affordances in the field of ecological psychology. Gibson posits that actors perceive objects in their environments not in terms their material properties but in terms of affordances, that is, the possibilities for action they afford that will allow them to meet their goals. Thus, a hammer is not a hard object with a wooden handle but an affordance for inserting a nail into a board. Drawing on Strong et al. (Citation2014) in the field of IS, we define affordances as “potential[s] for behaviors associated with achieving an immediate concrete outcome and arising from the relation between an artifact and a goal-oriented actor or actors.” In this regard, we differentiate between affordances, that is, “potential[s] for action with respect to an actor’s goals” (Volkoff & Strong, Citation2017, p. 236) and their actualisation, which refers to specific actions taken by individual actors. Based on the general meaning of the word “affordance”, the concept of affordances is often used to refer to enablement. However, as Leonardi (Citation2011), Majchrzak and Markus (Citation2013), and Volkoff and Strong (Citation2017) argue, affordances are both enabling and constraining. For instance, accessing one’s email using a smartphone enables an actor to work from various locations and meets the actor’s goal of flexible work locations and hours. At the same time, this feature may be constraining by making it more difficult for the actor to “switch off” from work when that is her goal. If actors perceive that a technology constrains them from achieving their goals, they may change their routines and/or the technology (Leonardi, Citation2011). In the process of adopting and appropriating a technology, actors may also discover new affordances (Riemer & Johnston, Citation2012) or be able to actualise an affordance more effectively as their skill levels increase (Volkoff & Strong, Citation2017).

Affordance theory is employed in IS research to explore how technology is adopted and adapted and how technology use is interwoven with and triggers changes in organisational structures (Volkoff & Strong, Citation2017). From a socio-technical perspective, affordance theory allows researchers to examine the material properties of technology (i.e. hardware and software) and its social and contextual aspects at the same time. For instance, Ellison et al. (Citation2015) investigate how affordances offered by Enterprise Social Networks (ESN) may impact organisations’ knowledge-sharing practices. In the context of green IS, Seidel et al. (Citation2013) use an affordance lens to show how IS can contribute to creating (and be designed to create) environmentally sustainable organisations.

In this study, an affordance lens is helpful in conceptualising the affordances and constraints that individuals perceive from using WCS in a specific context, that is, during the lockdown. While the specific distancing regulations varied from region to region, most countries imposed regulations that restricted people’s mobility and contact with others, banning public events and gatherings and closing public facilities like “non-essential” shops, recreational facilities, and museums. Because people often tweeted about their use of WCS during the crisis, this data is available for analysis of the specific actions, or actualised affordances, people took. Analysing those actions allows us to infer WCS’s affordances of which actors became aware during the crisis. Given of our dataset and topic modelling approach, in terms of material qualities our analysis is restricted to features that are usually part of WCS and features that specifically came up in our automated analysis, such as virtual backgrounds. Despite this limitation, we consider an affordance lens appropriate for exploring how people reinterpreted WCS and started to use them in new ways during the COVID-19 pandemic.

3. Research method

Given the enormous uptake of WCS during the COVID-19 crisis (e.g. Reuters, Citation2020), this study’s goal is to document the use of WCS that emerged at that time. Rather than testing existing theory, we adopt an inductive (or data-driven) approach to identify new themes and relationships from digital trace data (Berente et al., Citation2019; Müller, Junglas, vom Brocke et al., Citation2016). Hence, prior work on WCS and affordance theory only guide our data collection, analysis, and discussion (Müller, Junglas, vom Brocke et al., Citation2016).

3.1. Data collection and preparation

In light of our research goal, we sought access to data that would lead to insights into the use of WCS by many social actors in many contexts. We chose the microblogging platform Twitter as our data source since many institutions, organisations, and private individuals used it to disseminate COVID-19-related information and report on their lockdown experiences (Hutchinson, Citation2020). Using Twitter facilitates both breadth of data in terms of a comprehensive view of a variety of actors’ WCS use, and depth of data through a detailed analysis of selected tweets. In addition, digital trace data from Twitter is naturally occurring data that can be collected unobtrusively and without being prone to biases that originate from self-reported data collected through interviews or surveys (Müller, Junglas, vom Brocke et al., Citation2016).

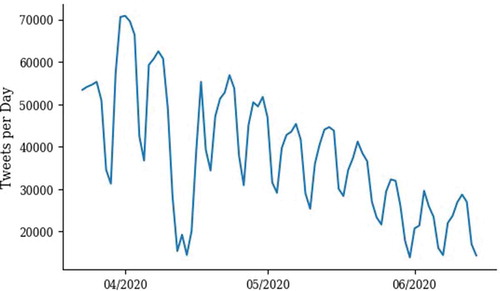

We began collecting tweets on March 23 2020 using Twitter’s REST API and the search terms microsoftteams, skype, zoom, and webex. The search terms refer to WCS that are commonly used to support synchronous communication and collaboration in both business and the private realm. The sample of tweets used in this study comes from twelve weeks of data collection, from March 23 2020 to June 14 2020. The initial dataset of 11 million tweets was reduced to 3.4 million tweets after removing non-English tweets and retweets. We also compared tweets without their trailing hashtag(s) and removed tweets that were 95 percent duplicates of other tweets. This step filtered out about 200,000 tweets, leading to a dataset of 3.2 million tweets. We also did a manual check of eight users who posted a high number of tweets and deemed them spam-bot users, so we removed their tweets (25,560 tweets) from the dataset. , which shows the distribution of the tweets in our dataset over time, indicates that people usually tweet more during the week than they do on weekends and that the traffic related to our search terms decreased as time progressed.

3.2. Data analysis

We used probabilistic topic modelling, a well-established text-mining approach, to identify themes related to the use of WCS during the COVID-19 pandemic. The core idea of this approach is that text – in this case, tweets – contains multiple topics in varying proportions. Topic modelling is used in IS research to analyse datasets in various contexts, such as analysing online job advertisements to identify and compare the skills that are demanded by the job market (e.g. Föll et al., Citation2018; Handali et al., Citation2020), deriving the benefits of customer service management from service request tickets (Müller, Junglas, Debortoli et al., Citation2016), and investigating the evolution of IS research (Jeyaraj & Zadeh, Citation2020). Tutorials on using topic modelling in IS research (Debortoli et al., Citation2016; Müller, Junglas, vom Brocke et al., Citation2016; Schmiedel et al., Citation2019) guided the approach we applied.

We used the cloud-based text-mining tool MineMyText.com, which employs the Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) algorithm, to extract topics from the tweets in our dataset (Blei et al., Citation2003). This algorithm models a document as being composed of a fixed number of topics with proportions from 0 percent (if the document contains no topics) to 100 percent (if the document contains only one topic) – that is, a probability distribution of topics. In a similar fashion, a topic is modelled as a probability distribution of words, and then extracted topics are interpreted manually. We used LDA because it is well-researched from both the technical and the application perspectives, what includes its use in analysing tweets (Jelodar et al., Citation2019).

Setting the number of topics is a key step in implementing LDA. Using Debortoli et al.’s (Citation2016) tutorial, we evaluated various numbers of topics, from 20 to 100 topics in steps of 10, and used the semantic coherence metric to evaluate these topic models automatically. In particular, we applied the method Lau and Baldwin (Citation2016) propose, which builds on Lau et al. (Citation2014), who take pairs of terms present in the top n words used in addressing a topic and calculate how often these pairs co-occur in a narrow, sliding window over a reference corpus. This calculation results in a normalised pointwise mutual information (NPMI) score that ranges between −1 (worst) and 1 (best). shows the computed NPMI score for each topic model that results from averaging its NPMI scores for different numbers of top n words (i.e. 5, 10, 15, and 20) to increase the reliability of the metric (Lau & Baldwin, Citation2016). Then we performed a qualitative evaluation of the coherence of the topic models with 20, 30, 50 and 60 topics and selected the topic model with 50 topics. This model differentiates the topics better than those of coarse-grained models (i.e. 20 and 30 topics) while the added complexity of the model with 60 topics did not provide additional valuable information.

Our final topic model for the analysis undertakes four natural-language pre-processing steps:

Removing Twitter users’ names, URLs, numbers, and punctuations.

N-gram tokenising up to bi-grams – that is, splitting tweets into single words and sequences of two words.

Removing stopwords – that is, words that are deemed uninformative. In addition to the standard English stopwords (e.g. “the”, “is”, “and”), we added “zoom”, “skype”, “webex”, “microsoftteams”, “call”, “meet”, “im”, “meeting”, “join”, “link”, “links”, “dont”, and “youre”. The tool names used in the data collection are removed along with other frequent words, as these words do not add new information to the tweets and might hamper interpretation of the topics.

Lemmatising – that is, reducing words to their dictionary form.

The topic modelling resulted in fifty topics that we labelled and categorised as shown in . We labelled topics inductively, that is, by looking into a topic’s most likely words and most likely associated tweets. In doing so, we realised that topics were often connected to one of the contexts of WCS use – namely, business, private life, and education – that we also found in our literature review. Having initially analysed and aggregated findings according to those categories, we decided to exclude topics that were associated with the education context. The WCS-enabled sudden digitalisation of all levels of education is a large-scale phenomenon of the COVID-19 crisis, so it is also diffuse, as it pertains to various types of educational institutions (primary and secondary schools, universities) and stakeholders (instructors, learners of all ages, parents). Given the scale of this category and its associated topics, we felt that this category deserves a separate study. In addition to excluding topics related to education, we excluded eight topics either because they included a highly mixed set of tweets that did not allow a clear assignment of a label or because they were irrelevant to the topic (e.g. using “zoom” as it relates to photography). Taken as a whole, this process excluded eighteen of the fifty topics. Of the remaining 32 topics, 18 were connected with one of five affordances (A1-A5), and 14 were connected with one of five constraints (C1-C5) that we derived inductively from the topics.

We performed topic modelling on a sample of our 3.2-million-tweet dataset to streamline the topic-extraction process. We randomly sampled 50 percent of the tweets from the first six weeks (1,950,844 tweets published between March 23 2020 to May 3 2020) and used the resulting topic model to assign topics to the remaining tweets. This approach – specifically, the implementation done in a Python package called lda – is proposed in Wallach et al. (Citation2009) and further justified in Buntine (Citation2009). lda uses the topic-word distribution (i.e. the probability that a word belongs to each topic) from the LDA output and an approach called ‘iterated pseudo-count’ to provide accurate estimates of the likelihood that an unseen document contains a particular topic. In addition to content-related labelling of the topics, we considered the distribution of the topics over time by grouping and aggregating topic probabilities on a daily level to observe the development of each topic’s prevalence over time (Müller, Junglas, Debortoli et al., Citation2016).

4. Findings

This section presents our findings regarding the affordances and constraints that arise from the use of WCS during the COVID-19 crisis. Affordances and constraints are reported from the viewpoint of consumers (e.g. those who attend virtual events rather than those who offer virtual events) where such roles can be distinguished.

4.1. Affordances

Here we introduce five affordances (A1-A5) (i.e. action potentials) that individuals perceive from the use of WCS (). As shows, these affordances pertain to various parts of individuals’ lives. The sections describe the actions taken and illustrate them with quotationsFootnote1 from our dataset. provides an overview of the topics (T) that are connected to the affordances, including exemplary tweets and visualisations of the topics’ distribution over time.

Table 1. Affordances that arise from the use of WCS

Table 2. Overview of topics connected to affordances (A1-A5), along with an exemplary tweet and topic distribution over time. (Gridlines on the graph refer to Sundays.)

A1. Communicating with social groups: virtual catch-ups and coffee breaks

Our analysis reveals several actions that relate to the affordance of communication with social groups. During the COVID-19 crisis, many people used WCS to catch up and keep in touch with family and friends (T12). One Twitter user reported using WCS for “[…] talking to my [family] and all their pets on [WCS] for the first time. It was new and beautiful and I am just [thankful] for technology right now”. People also used WCS to meet and socialise online with members of specific groups (T7, T25, T8), such as sports clubs and groups of volunteers. Video calls with the usual daily contacts were used to establish a sense of togetherness, avoid social isolation, and continue the operations of organised groups while being physically distant. Besides keeping up with daily contacts, some tweets suggest that people perceived the crisis as an opportunity to connect with weak-tie contacts. One Twitter user reported on a group of old friends as “[…] [we] are scattered around after [graduate] school. Today we had a group [video call] over lunch and it was just great to see everyone and relax a bit in […] old friendships.” We reason that people may have had more time to connect with such contacts, as their usual routines (e.g. the activities that would normally fill their evenings) were suspended. People may have had more time and/or may have considered that is was just as easy to reach geographically distant “old friends” using WCS as geographically proximate friends when contact restrictions were in place.

In addition, we find that WCS facilitated social encounters beyond people’s usual circles of private contacts, as WCS were used to interact socially with colleagues, such as during virtual coffee breaks or lunch breaks: “I started a [virtual] morning coffee break with my team […]. No work talk, just a chance to chat and check in […].” Topics related to work-related social gatherings online (T17) peaked on Mondays and Fridays. While some companies may have established informal meetings among employees prior to COVID-19 – some tweets point to the online continuation of a regular physical “happy hour tradition” – such interactions are often by-products of formal meetings or they occur by chance, such as when people happen to meet at the coffee machine. Clearly, bumping into each other is not possible when people are physically distant, so planned and dedicated virtual social encounters with work contacts seem to have emerged as a new form of online meeting during the COVID-19 crisis.

A2. Engaging in shared social activities with family and friends: online parties, activities, and reunions

A number of topics point to individuals’ engaging in online socialising with family and friends by, for example, meeting online to watch movies (T49), celebrate birthdays (T34), have virtual parties (T24), or play games (T11, T22). As one tweeter reported, “[…] we had all the family on [WCS] last Saturday night for [playing] bingo it was great fun […].” While playing games online is not a new thing, with whom people played and what objects they used in online games may have been different during the lockdown. Rather than playing alone or meeting with (possibly) unknown gamers in a virtual world, people played with their everyday contacts as a replacement for a physical meeting. Some of those games involved physical items used, such as physical bingo cards or dice cups, so everyday objects were sometimes integrated into virtual interactions. While the tweets reported that meeting people in person and doing things at places other than home were preferred, people appreciated being able to use virtual substitutes for what they would normally have done: “[…] I am looking forward to […] going out and socialising again but I have quite enjoyed [virtual] meetings and family quizzes. […]” As indicated by a peak in the distribution of T45, family reunions attached to holidays like Easter and Passover Seder were also virtualised during the COVID-19 crisis: “My family had a [virtual] Seder, too […] there was a huge [group] […] that I would never see as they are on the opposite coast and [live] pretty [far away]. […] it was a much better and more memorable Seder.” Tying in with our findings regarding the virtual social meetings (A1), this tweet suggests that having to virtualise social interactions enabled encounters that may not have taken place otherwise. Paradoxically, being forced into technology-mediated interactions because of social distancing resulted in some people’s being in touch with more people than they would have been otherwise.

A3. Attending events: virtual concerts, church services, and board meetings in the living room

Our analysis shows that people attended online what are usually physically oriented events, including events related to personal interests, such as concerts (T29), and events that pertain to public life. For instance, we found evidence of church-related events and activities taking place online (T43): “Join us live each Sunday […] for our live morning prayer broadcast at 10:30am with virtual coffee hour […] after the service.” Moreover, people could attend online events related to community and public services using WCS (T26): “[WCS use] brings its own challenges but we are trying to utili[s]e technology to keep cases moving. Please review these […] rules before scheduling a [virtual] hearing […].”

A4. Pursuing hobbies: online yoga classes and book clubs

We also found that WCS enabled people to perform activities related to personal interests, such as discussing books in a book club (T27) and attending exercise classes (T30): “[Three] more weeks of lockdown = [three] more weeks of live [virtual] fitness sessions with trainer […] – Monday 9.30am, Wednesday 6.30pm, Friday 9.30am, Sunday 9.30am […].” While such activities as online exercise classes occurred prior to the crisis, our data indicates that many of these classes also took place live via WCS. As such, they facilitated shared and simultaneous, that is, interactive, activities, approximating the situation in an in-person physical fitness class. Rather than referring to those classes as “online exercise classes”, we might consider them WCS-mediated physical classes, as WCS merely served as a channel. Our analysis does not reveal who took part in such classes or why they did so. People may have converted hobbies that were once physically oriented into virtual hobbies or engaged in alternative activities simply because they were offered online. The disruption of people’s usual day-to-day lives may have caused them to look for new activities that would work under the circumstances. Meeting online to chat with, for example, team members of a sports club (T7) can also be considered a virtual substitute for a physical hobby that is difficult to digitalise.

A5. Consuming non-recreational services: online counselling sessions and webinars

Finally, our analysis shows that individuals used WCS to attend webinars (T37) and access certain services offered online (T44). As one counsellor tweeted, “[…] some clients have asked me if I can do [virtual] sessions […]. For those of you who are unable to visit me in person, an online […] session […] is now available […].” Being able to attend such virtual appointments to access wellbeing support services or receive health advice or career advice may have been a way to deal with the crisis as well as a way to continue attending routine consultations.

4.2. Constraints

In our analysis, we identified five constraints (C1-C5) that prevented or hindered people from accomplishing their goals by using WCS (). Such constraints arise from issues related to technology, the overall lockdown context, and the combination of both during the lockdown. In general, we find that the heavy reliance on technology to work and live while being largely confined at home frequently blurred the boundaries between work and private life. In fact, while the affordance was implicit in the data, we saw few tweets about how WCS were used to continue work, so we did not formulate an affordance regarding this type of interaction. However, many tweets did relate to issues and frustrations that people experienced while working from home, so most of the constraints described in the following pertain to this context. Where applicable, we also report on strategies or newly discovered affordances that helped people mitigate these constraints. provides an overview of the topics connected to the constraints, including exemplary tweets and visualisations of the topics’ distribution over time.

Table 3. Constraints that arise from the use of WCS

Table 4. Overview of topics connected to constraints (C1-C5), along with an exemplary tweet and topic distribution over time. (Gridlines on the graph refer to Sundays.)

C1. Lacking features and competencies: how to set up and configure a WCS

Our analysis reveals that WCS lacked the features required to meet users’ needs and that people lacked the skills to set up and configure WCS. Questions and advice for getting started with web-conferencing and regarding features like configuring security settings (T45) and recording sessions (41) show how users mitigated this constraint by seeking support. Over time, the topic related to getting started with WCS (T13) decreased slightly, while discussions about the benefits and drawbacks of WCS (T9) increased slightly. That people started discussing these benefits and drawbacks indicates that they had achieved a certain level of proficiency using the technology as a result of using it frequently in their daily lives, which enabled them to make informed evaluations.

C2. Having fear of being on camera: masking how one looks

Our analysis suggests that individuals found it difficult to comply with the norms and habits associated with work, such as wearing work clothes, in the absence of the physical workplace outside the home (T48): “Working from home week one: ‘I [am going to get dressed up] and maintain a routine.’ Working from home week […]: ‘I will wash my hair [only] if I am for sure going to be on [a video call].’ […]” Not having to go work and completely relying on technology allowed people to let themselves go, so since using the camera would reveal their unprofessional look, they felt exposed and uncomfortable and reluctant to use the camera (T36). We observe that people dealt with this constraint by configuring the camera so they looked good: “Did that thing […] where [you] zoom into [your] face instead of hold the camera close […].” Hence, as people got more proficient in using the technology, they became able to realise more effectively the affordance of communicating professionally with work contacts.

C3. Having to be always “on”: “zoom fatigue”

While WCS enabled people to work and have a social life during the COVID-19 crisis, our analysis also reveals constraints that arose from this unconditionally digital life. Some tweets indicated increased demands on their time and a prevalence of unnecessary meetings, which were also perceived as a monitoring instrument: “[…] if you are requiring [people] to be on more [video] calls than meetings you [would] have in person: is this because [the pandemic] increased the need for calls? Or, -do you […] believe people can be productive [only in the] office. […]” Virtual social encounters (A1) were referred to as both “life-savers” and as contributors to fatigue with using WCS and drains on people’s energy: “One of the things I am finding challenging [about] working from home [is] spending [a lot of time] on [virtual] calls etc. – so [after] work you do not really want to call friends because you […] need a break from it.” The fact that most aspects of life happened via one channel appears key to such issues. In addition, managers and employees were relatively unprepared for this situation. Scheduling (too) many work-related and informal meetings may be an (overdone) attempt both to keep things under control and to prevent people from being isolated. While not every employee was able to work well from home, and even less so when facilities like childcare were not available, the data also indicates how people tried to establish strategies to adjust to the home-office situation and cope with information overload and “Zoom fatigue” (T2): “[…] I have started doing [some things] to maintain my mental health while I [work from home] […]: – recogni[s]e when my brain is at capacity and take a break – turn off [push] notifications when I need a break – limit the number of [video] calls […].”

C4. Exposing one’s private living space: unexpected co-workers entering the stage

Interruptions by new “co-workers” (T35), such as family members and pets, sometimes led to unintended and awkward situations during online calls with work contacts. While the corresponding tweets were often written in a joking tone, they point to blurred boundaries between people’s work and private lives because all aspects of life took place at home: “Day 2 of [my partner] being home helping with [the children while] I work. He walked past my laptop […] [while] I was on a [video] call [with] my boss. […].” Facing such constraints, people discovered that the virtual background feature could mask their actual background to give a more professional impression during work calls, as well as giving them a way to have fun, shape their “online identity” and make them feel like they were somewhere other than home: “[…] I have selected some of my favo[u]rite photos from [vacation spots], as well as recogni[s]able landmarks from our recent travels [for my own gallery]. […].” The weekday peaks for tweets about virtual backgrounds (T14) could indicate that this feature was used primarily in the business context.

C5. Lacking security: new vulnerability

Our data includes discussions about security and privacy issues (T15, T38), particularly at the beginning of April and June, as they related to Zoom’s security issues. We also found discussions on the “zoombombing” phenomenon (T39), with people asking for and offering meeting codes and asking others to stop this form of online trolling. As people digitalised their work and everyday lives to protect themselves and others from getting sick, they became more worried about the vulnerable parts of a life lived digitally. Relating to C3, we also recognise privacy risks pertaining to people’s private space at home, as colleagues, albeit unintentionally, could get a peek into others’ private lives.

5. Discussion and directions for future research

Recent history shows how disruptive macro-level events can lead people to reassess existing social norms and order. The global financial crisis in 2008 invited people to think about the role and governance of money, which then gave rise to Bitcoin and other kinds of digital money (Kavanagh et al., Citation2019). The case of Bitcoin illustrates how a crisis can trigger the emergence of a new technology – in this case, blockchain technology, which is now employed far beyond the use case of cryptocurrencies.

In this paper, we have shown how WCS became a mainstream communication channel during the COVID-19 crisis. However, WCS are not new and WCS have not changed a lot since the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis. Why, then, should we bother conducting research about the adoption of WCS during the crisis? Here we discuss what was unique about WCS during the COVID-19 crisis and suggest topics for future research. compares previous work on WCS use related to the identified affordances and constraints with the findings of this study. Our research agenda is shown in .

Table 5. Comparison of findings with prior work and implications of the COVID-19 crisis on WCS

Table 6. Research agenda

We contend that the rationale for and the speed and extent of WCS adoption during the COVID-19 crisis was unique. In this regard, we may ask, given that the technology and people were (mostly) ready to use WCS prior to COVID-19, why had such systems not yet become more the norm? For instance, why did people continue to travel for business overseas rather than set up a video call that would save considerable time and money? The answer is that no one had to. Even though the capabilities and benefits of WCS were known before the crisis, the absence of necessity and prevailing social norms, such as the preference for face-to-face interactions (Larsen, Citation2015), prevented people from breaking their habit of meeting in person. The contact restrictions imposed to contain the spread of COVID-19 created the necessity that outweighed prevailing social norms. The numbers of downloads of WCS applications in March (Perez, Citation2020) indicate a rapid adoption of WCS by an extraordinarily high number of people in many locations around the world. Downloading an application and creating an account was all it took for them to shift activities and interactions to the virtual world. From the many tweets concerning how to configure WCS, we can conclude that a considerable number of people had little experience using WCS and/or were not particularly tech-savvy. Since “laypeople” had to integrate this technology into their day-to-day lives and businesses, theory on the diffusion of innovations in social networks (Tscherning, Citation2012) suggests that the discourse on Twitter about the use of WCS indicated a collective process of learning and becoming aware of the affordances and constraints of this technology. Simultaneously, the discourse on Twitter and other social media platforms is likely to have contributed to the diffusion of affordances, which some actors recognised right away and then spurred others to consider, concerning what WCS could offer them in their specific contexts, such as online cultural events and classes as a substitute for real-life meetings. We also see how network effects came into play: As more people in more contexts (e.g. families for private interactions, consumers and providers of leisure time activities) started using WCS, others became more inclined also to adopt WCS, which increased their overall acceptance and valuation.

As COVID-19 is a prolonged crisis, we may wonder what will stay and what will go and how the crisis, despite its far-reaching negative impact, may also serve as a “window of opportunity” (Tyre & Orlikowski, Citation1994) now that people have been forced to change their habits. While the advantages of face-to-face interactions over virtual meetings should not be neglected, we encourage a discourse about which of the newly established virtual practices should stay. For instance, never before has it been so easy to “attend” a festival or conference or to visit a famous museum that is geographically out of reach. We could argue, then, that this crisis has allowed more people to participate in such events, increasing inclusion. Therefore, we recommend that providers of services and events think about business models and hybrid formats that could help them survive this crisis and future crises. We also invite companies and institutions to reconsider their travel policies. Given that academic mobility is recognised as an important factor in education institutions’ carbon footprint (e.g. Arsenault et al., Citation2019), the IS community could take a leading role in establishing tools and concepts for hybrid or fully virtual conferences. That said, the adoption of technology to support new use cases may change the competitive landscapes of industries that provide services that are typically consumed in the areas around where people live such that the digital may challenge the non-digital. For instance, if cultural events continue to be offered online, some people may choose the online event over the physical event they would otherwise have attended, and students may prefer to attend online classes offered by renowned universities, rather than going to a local university. Competition between the virtual and the non-virtual has the potential to improve both, as the WCS experience improves and expands and in-person service providers create unique customer experiences at their locations by, for example, demonstrating the value of in-person classes through collaborative and in-class projects, discussions, and problem-solving.

Beyond why and how the adoption of WCS occurred, what is unique about the use of WCS during the COVID-19 crisis? Our analysis shows how WCS emerged as a standard communication channel pertaining to multiple areas of life as people attempted to translate everyday activities and interactions to the virtual world. How WCS facilitated shared and synchronous social activities that approximate real-life interactions was unique. However, despite what has recently been achieved in using WCS, improvements are needed for such systems to enable more natural encounters, such as real-life encounters that occur without prior invitation. The (physical) coffee machine offers one a good chance of running into (new) people. Such informal encounters contribute to employees’ general awareness about what is going on, help to establish common ground, and may be the starting point for an innovative idea (Allen et al., Citation2007). Designers of IS should think about features that facilitate spontaneous encounters, such as bots that randomly set up meetings with known or unknown people. In addition, we recognise a need for features that facilitate more natural group experiences in online meetings. Consider a group of people meeting for drinks after work: Over the course of the evening, they are likely to have a variety of conversational set-ups, such as one person saying something to whole group, people talking in subgroups, and people leaving one and joining another subgroup after overhearing part of an interesting conversation. Such experiences are not supported in current WCS, where people cannot talk with one group and listen to other conversations at the same time. While break-out rooms support the idea of splitting into sub-groups, entering a break-out room prevents one from being aware of what is happening in other groups. Novel technologies, such as virtual reality, might be used to create more realistic group encounters and to address issues like scalability and real-time capabilities.

After WCS became the main communication channel for many people at the same time, WCS emerged as a social technology that led to a new virtual togetherness. Affordances that long-distance families have long recognised (Geenen, Citation2017) were finally recognised by people who were suddenly restricted from meeting with each other. While personal interactions in this new context were expected, how this new virtual togetherness pertained to professional settings and the greater community in the form of virtual coffees, happy hours and the like seems unique. Prior to the crisis, the lack of access to such interactions was one reason that remote workers felt socially isolated and often “left out” (Hafermalz & Riemer, Citation2016a), but we learned during the crisis how remote work and personal interaction can go hand-in-hand. In the absence of real-world hallways and coffee machines, companies established informal social meetings to keep up the “water cooler” interaction; these proactive measures prevented social isolation and indicated increased awareness and prioritisation of the social side of work. As remote work is likely to become more prevalent after the crisis than it was before the crisis (e.g. Wronski, Citation2020), research and practice alike should develop strategies for how WCS and other tools, such as ESN, can be used to prevent isolation and feelings of “us versus them” in (partly) distributed teams (Sarker & Sahay, Citation2003). In addition, future research should investigate in more detail what constituted “virtual togetherness” during the COVID-19 crisis and how it differed from the virtual togetherness and social presence that prior work investigates (Barden et al., Citation2012; Lombard & Ditton, Citation1997). Given that some streamed events, for example, could be attended by an international audience, this “virtual togetherness” could even occur at a global level.

In addition, WCS facilitated activities and meetings that would not have taken place otherwise. Not only have people met online and performed activities with their day-to-day contacts, such as family and work contacts, but given that everyone and everything were out of reach, they also organised meetings with old friends who were suddenly as accessible as their neighbours through WCS. People who face constraints in meeting people or taking part in activities because of such issues as family obligations or health had better access to a social life during the crisis than they did when everyone else was out and about all day. Benefits connected with remote work (Kurkland & Bailey, Citation1999) or distance education (Mupinga, Citation2005), such as increased flexibility, were now experienced in private and social activities. On the other hand, people with once good access to real-life activities and interactions may have skipped virtual substitutes or perceived them only as “better than nothing”, rather than a “good option”. Since the experiences of non-adopters are not likely to be included in our dataset, which is naturally biased towards adopters of WCS, future research could examine more closely the factors that drove or impeded people’s adoption of WCS during the crisis. We reiterate that forced and unconditional digitalisation revealed the potential of WCS to allow more people to benefit from virtual practices. As access to infrastructure and technology and the skills to use them are becoming ever more important, we should work to mitigate a digital divide by developing strategies and implementing measures that ensure the inclusion of less “digitally fit” groups in their use.

What happened as many aspects of life were suddenly mediated by one channel? Our view is that the use of WCS during the COVID-19 crisis was connected to a unique blending of contexts. The issue of blurred boundaries between work and private life is well established in previous research on remote work (e.g. Kelliher & Anderson, Citation2010), but what seems new is that this blurring is not experienced only by remote workers because of the lack of physical separation between work and private living space, but that other persons at home and distant actors (e.g. during a videoconference) also play an active role in this process of blending. Such blending pertains not only to interactions at work and in private life but also to interactions with acquaintances while pursuing hobbies online. Given the blending of contexts, we recognise a need for features that give people a chance to make a good impression. For many people, virtual backgrounds became part of their (virtual) identities; some organisations even released virtual backgrounds to promote brand recognition, so a design element created utility in the new context of digital cooperation. It also shaped behaviour on the individual and organisational levels, as well as on the market level since increasing numbers of tools now provide virtual background features. Other features that facilitate identity and impression management could help increase personal comfort during videoconferences.

Our also analysis suggests that entering an online meeting is not sufficient to make people feel like they are somewhere else. Firm resolutions to create an “office-like” situation at home by, for example, wearing professional clothing and establishing routines were often discarded quickly. While these issues are not new, they are aggravated when everyone works from home. Relating to prior work on technology overload (e.g. Saunders et al., Citation2017), for some, the heavy reliance on web-conferencing as the main medium for conducting one’s life led to physical and mental exhaustion. There is a need for concepts and features that ensure that place and time can be experienced. While corporate virtual backgrounds help to address this issue, additional features that create context (e.g. features that make an employee feel he or she is at work), mimic external factors, monitor progress, and help people plan their days and stay focused could mitigate such issues. Organisations should also train managers in leading distributed workforces and recognising issues early.

Finally, we showed how heavy reliance on WCS during the COVID-19 crisis revealed privacy and security issues related to existing applications, spurred new forms of cyber-attacks, and created new risks, especially those that pertain to people’s private living space. The more people and organisations communicate and collaborate online, the more vulnerable they become in the virtual world. To prevent a wave of cyber-security issues, IS designers should develop additional privacy- and security-enhancing features. Companies and institutions should also review their IT security and develop employee training on how to avoid these issues.

compares this study’s findings with prior work and presents the unique aspects of WCS use during the COVID-19 crisis. summarises our suggestions for future research.

6. Conclusion, limitations, and outlook

In this paper, we explored the use of WCS during the COVID-19 crisis using an analysis of Twitter data. Our analysis suggested that WCS emerged as channel that facilitates access to everyday activities and contacts that were temporarily “locked away” because of COVID-19 mitigation efforts. We showed how individuals moved once physically oriented leisure activities and social interactions to an online environment. We found that technology use during the COVID-19 crisis went beyond solving a problem of distance, as the crisis situation and contact restrictions stimulated people’s creativity and willingness to recognise and actualise new affordances (as well as previously known affordances) in new settings, revealing that, as social distance became the norm, many people became more, not less, social. New use cases by public services and institutions indicated technology’s central role in helping societies respond to this crisis. This study also developed insights into the constraints that arose from the unexpected and unconditional digitalisation of life. We discussed the benefits of some of the newly established digital practices and highlighted the importance of features that facilitate impression and identity management, context creation, more natural encounters, and privacy protection.

Our study has several limitations that lead to other suggestions for future research. Collecting and analysing social media data, particularly Twitter data, comes with its own challenges. Firstly, Twitter’s API involves particular algorithms that “decide” which tweets are collected first (Driscoll & Walker, Citation2014; Morstatter et al., Citation2013). Unlike the popular Stream API, which facilitates the real-time collection of tweets, using the REST API allowed us to collect tweets published several days before the time of the search. While we expected this approach to yield a larger coverage, the possibility of missing tweets remains. Secondly, as with other social media data, the platform’s demographics (Bruns & Stieglitz, Citation2014), its users’ varying roles and influence (Mirbabaie & Zapatka, Citation2017), and the existence of social bots (Stieglitz et al., Citation2017) may introduce biases in terms of content. As a result, we were able to identify affordances and constraints based only on the communications of the people or institutions that tweeted about them. Thirdly, spam in the social media data could have inflated the amount of data with irrelevant context (Stieglitz et al., Citation2018). We introduced additional data-filtering and pre-processing steps to mitigate the data quality issues. Given the size of our dataset and the wide adoption of Twitter, we believe we achieved a level of coverage that would be required to obtain an initial overview of people’s adoption of WCS during the COVID-19 crisis. In addition, given the nature of our dataset and the scope of this paper, we could derive only limited insights into how actors engaged with the material qualities – that is, features – of WCS in becoming aware of and actualising affordances. Based on these limitations and our initial insights, we plan to continue this project by conducting interviews and fielding surveys to refine and validate our findings and to derive additional design implications that could address the constraints to WCS use.

The welcoming address of an online concert included the observation that “the global community has had to find a new way of sharing, […] and they have found it. People are not just enjoying music together; they are also making music together. And all via the Internet, via livestreaming.”Footnote2 The use of technology in this time of crisis had positive outcomes that would not have been achieved otherwise. We encourage IS scholarship and practice to help societies, businesses, and institutions to deepen and extend the discourse on how technology facilitated an effective response to this crisis and how what we learned from it can help address societal problems more generally. In particular, IS research could show how to leverage the new and potential advantages offered by technology during and beyond the COVID-19 crisis, help to point out missing or obsolete features, and explore the effects of technology use in other settings. We hope our initial insights will inspire this conversation and inform future investigations in this field.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1. All tweets quoted in this paper were edited to ensure the anonymity of the tweets’ authors.

2. This quotation from Burkhard Jung, Lord Mayor of the city of Leipzig, Germany, was part of the welcoming address of the opening concert of the “Bach Marathon”. This online event, streamed live from St. Thomas’s Church, was launched since the physically oriented Bachfest was cancelled because of the COVID-19 pandemic. (Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JDYEkI-w7fk)

References

- Allen, J., James, A. D., & Gamlen, P. (2007). Formal versus informal knowledge networks in R&D: A case study using social network analysis. R&D Management, 37(3), 179–196. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9310.2007.00468.x

- Arsenault, J., Talbot, J., Boustani, L., Gonzalès, R., & Manaugh, K. (2019). The environmental footprint of academic and student mobility in a large research-oriented university. Environmental Research Letters, 14(9), 9. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab33e6

- Ashworth, B. (2020). How to host a virtual watch party. WIRED. https://www.wired.com/story/how-to-host-a-virtual-watch-party/

- Backhaus, A., Agha, Z., Maglione, M. L., Repp, A., Ross, B., Zuest, D., Rice-Thorp, N. M., Lohr, J., & Thorp, S. R. (2012). Videoconferencing psychotherapy: A systematic review. Psychological Services, 9(2), 111–131. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027924

- Barden, P., Comber, R., Green, D., Jackson, D., Ladha, C., Bartindale, T., Bryan-Kinns, N., Stockman, T., & Olivier, P. (2012). Telematic dinner party. In Proceedings of the designing interactive systems conference on - DIS ’12, 38-47. ACM Press. https://doi.org/10.1145/2317956.2317964

- Berente, N., Seidel, S., & Safadi, H. (2019). Research commentary—data-driven computationally intensive theory development. Information Systems Research, 30(1), 50–64. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.2018.0774

- Blei, D. M., Ng, A. Y., & Jordan, M. I. (2003). Latent Dirichlet Allocation. The Journal of Machine Learning Research, 3, 993–1022. https://doi.org/10.5555/944919.944937

- Boell, S. K., Campbell, J., Cecez-Kecmanovic, D., & Cheng, J. E. (2013). Advantages, challenges and contradictions of the transformative nature of telework: A review of the literature. Proceedings of the 19th Americas conference on information systems, Chicago, IL, USA.

- Brecher, D. B. (2013). The use of skype in a community hospital inpatient palliative medicine consultation service. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 16(1), 110–112. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2012.0022

- Brubaker, J. R., Venolia, G., & Tang, J. C. (2012). Focusing on shared experiences. Proceedings of the designing interactive systems conference on - DIS ’12, 96-105. ACM Press. https://doi.org/10.1145/2317956.2317973

- Bruns, A., & Stieglitz, S. (2014). Twitter data: What do they represent? It - Information Technology, 56(5), 240–245. https://doi.org/10.1515/itit-2014-1049

- Buhler, T., Neustaedter, C., & Hillman, S. (2013). How and why teenagers use video chat. Proceedings of the 2013 conference on computer supported cooperative work - CSCW ’13, 759-768. ACM Press. https://doi.10.1145/2441776.2441861

- Buntine, W. (2009). Estimating likelihoods for topic models. In Z. Zhou & T. Washio (Eds.), Advances in machine learning. ACML 2009 (pp. 51–64). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-05224-8_6

- Cairncross, F. (1997). The death of distance: How the communications revolution will change our lives. Harvard Business School Press.

- Charron, J. P. (2017). Music audiences 3.0: Concert-goers’ psychological motivations at the dawn of virtual reality. Frontiers in Psychology, 8(May), 8–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00800

- Chon, M. (2020). ideas for throwing a virtual game night while social distancing (Oprah Magazine). https://www.oprahmag.com/life/a32022684/virtual-game-night/

- Clutch.co. (2020). Change in remote work trends due to COVID-19 in the United States in 2020. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1122987/change-in-remote-work-trends-after-covid-in-usa/

- Cohen, D. (1999). Knowing the drill: Virtual teamwork at BP. http://www.providersedge.com/docs/km_articles/Virtual_Teamwork_at_BP.pdf.

- Consumer Technology Association. (2020). Percentage of U.S. households that report using tech services during the 2020 COVID-19 outbreak. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1122611/tech-services-consumption-consumers-covid19-us/

- Cox, J. (2020). 15 of the best live streams and online virtual concerts. What Hi-Fi? https://www.whathifi.com/features/best-live-streams-and-concerts

- Cyarto, E. V., Batchelor, F., Baker, S., & Dow, B. (2016). Active ageing with avatars. Proceedings of the 28th Australian conference on computer-human interaction - OzCHI ’16, 302–309. ACM Press. https://doi.10.1145/3010915.3010944

- Debortoli, S., Müller, O., Junglas, I., & Vom Brocke, J. (2016). Text mining for information systems researchers: An annotated topic modeling tutorial. Communications of the association for information systems, 39(1), 110–135. https://doi.10.17705/1CAIS.03907

- Dennis, A. R., & Valacich, J. S. (1999). Rethinking media richness: Towards a theory of media synchronicity. Proceedings of the 32nd annual Hawaii international conference on systems sciences, Maui, HI, USA. https://doi.org/10.1109/HICSS.1999.772701

- Dennis, F., & Valacich. (2008). Media, tasks, and communication processes: A theory of media synchronicity. MIS Quarterly, 32(3), 575. https://doi.org/10.2307/25148857

- Driscoll, K., & Walker, S. (2014). Big data, big questions| Working within a black box: Transparency in the collection and production of big twitter data. International Journal of Communication, 8, 1745–1764. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/2171

- Earls, A. (2020). Livestreaming services hasn’t been an option for many churches. LifeWayResearch. https://lifewayresearch.com/2020/03/16/livestreaming-services-hasnt-been-an-option-for-many-churches/

- Ellis, T., Latham, N. K., DeAngelis, T. R., Thomas, C. A., Saint-Hilaire, M., & Bickmore, T. W. (2013). Feasibility of a virtual exercise coach to promote walking in community-dwelling persons with parkinson disease. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 92(6), 472–485. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHM.0b013e31828cd466

- Ellison, N. B., Gibbs, J. L., & Weber, M. S. (2015). The use of enterprise social network sites for knowledge sharing in distributed organizations: The role of organizational affordances. American Behavioral Scientist, 59(1), 103–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764214540510

- Fasciani, M., Eagle, T., & Preset, A. (2019). Magic quadrant for meeting solutions. Gartner. https://www.gartner.com/doc/reprints?id=1-1OEPTVBT&ct=190820&st=sb

- Fischer-Preßler, D., Schwemmer, C., & Fischbach, K. (2019). Collective sense-making in times of crisis: Connecting terror management theory with Twitter user reactions to the Berlin terrorist attack. Computers in Human Behavior, 100(November2018), 138–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.05.012

- Föll, P., Hauser, M., & Thiesse, F. (2018). Identifying the skills expected of IS graduates by industry: A text mining approach. Proceedings of the 39th international conference on information systems, San Francisco, CA, USA .

- Follmer, S., Raffle, H., Go, J., Ballagas, R., & Ishii, H. (2010). Video play: Playful interactions in video conferencing for long-distance families with young children. Proceedings of the 9th international conference on interaction design and children - IDC ’10, 3397–3402. ACM Press. https://doi.10.1145/1810543.1810550

- Fosslien, L., & Duffy, M. W. (2020). How to combat zoom fatigue. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2020/04/how-to-combat-zoom-fatigue

- Geenen, J. (2017). Show and (sometimes) tell: Identity construction and the affordances of video-conferencing. Multimodal Communication, 6(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1515/mc-2017-0002

- Gibson, J. L. (1977). A theory of affordances. In R. Shaw & J. Bransford (Eds.), Perceiving, acting and knowing: Toward an ecological psychology (pp. 67–82). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

- Grech, M. (2019). Video conferencing in 2019: Will it ever become the norm? https://getvoip.com/blog/2019/02/28/video-conferencing-2019/

- Hacker, J. V., Johnson, M., Saunders, C., & Thayer, A. L. (2019). Trust in virtual teams: A multidisciplinary review and integration. Australasian Journal of Information Systems, 23. https://doi.org/10.3127/ajis.v23i0.1757

- Hafermalz, E., & Riemer, K. (2016a). Negotiating distance: “Presencing work” in a case of remote telenursing. 37th international conference on information systems, Dublin, Ireland.

- Hafermalz, E., & Riemer, K. (2016b). The work of belonging through technology in remote work: A case study in telenursing. Proceedings of the 24th European conference on information systems, İstanbul, Turkey.

- Handali, J. P., Schneider, J., Dennehy, D., Hoffmeister, B., Conboy, K., & Becker, J. (2020). Industry demand for analytics: A longitudinal study. Proceedings of the 28th European conference on information systems.

- Hutchinson, A. (2020). Twitter says user numbers are up amid COVID-19 lockdowns, but warns of revenue impacts. Social Media Today. https://www.socialmediatoday.com/news/twitter-says-user-numbers-are-up-amid-covid-19-lockdowns-but-warns-of-reve/574719/

- Huysman, M., Steinfield, C., Jang, C.-Y., David, K., Huis, I., ’T Veld, M., Poot, J., & Mulder, I. (2003). Virtual teams and the appropriation of communication technology: Exploring the concept of media stickiness. Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW), 12(4), 411–436. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026145017609.

- Jelodar, H., Wang, Y., Yuan, C., Feng, X., Jiang, X., Li, Y., & Zhao, L. (2019). Latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA) and topic modeling: Models, applications, a survey. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 78(11), 15169–15211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-018-6894-4

- Jeyaraj, A., & Zadeh, A. H. (2020). Evolution of information systems research: Insights from topic modeling. Information & Management, 57(4), 103207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2019.103207

- Judge, T. K., & Neustaedter, C. (2010). Sharing conversation and sharing life. Proceedings of the 28th international conference on human factors in computing systems - CHI ’10, 2, 655-658. ACM Press. https://doi.org/10.1145/1753326.1753422

- Kavanagh, D., Miscione, G., & Ennis, P. (2019). The Bitcoin game: Ethno-resonance as method. Organization, 26(4), 517–536. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508419828567

- Kelliher, C., & Anderson, D. (2010). Doing more with less? flexible working practices and the intensification of work. Human Relations, 63(1), 83–106. https://doi.10.1177/0018726709349199

- King-O’Riain, R. C. (2015). Emotional streaming and transconnectivity: Skype and emotion practices in transnational families in Ireland. Global Networks, 15(2), 256–273. https://doi.org/10.1111/glob.12072

- Kurkland, N. B., & Bailey, D. E. (1999). The advantages and challenges of working here, there anywhere, and anytime. Organizational Dynamics, 28(2), 53–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0090-2616(00)80016-9

- Larsen, S. (2015). Videoconferencing in business meetings: An affordance perspective. International Journal of E-Collaboration, 11(4), 64–79. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijec.2015100104

- Lau, J. H., & Baldwin, T. (2016). The sensitivity of topic coherence evaluation to topic cardinality. Proceedings of the 2016 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, 483–487, San Diego, CA, USA. https://doi.10.18653/v1/N16-1057

- Lau, J. H., Newman, D., & Baldwin, T. (2014). Machine reading tea leaves: Automatically evaluating topic coherence and topic model quality. Proceedings of the 14th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 530–539, Gothenburg, Sweden. https://doi.10.3115/v1/E14-1056

- Lee, A. R., Son, S.-M., & Kim, K. K. (2016). Information and communication technology overload and social networking service fatigue: A stress perspective. Computers in Human Behavior, 55, 51–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.08.011

- Leonardi. (2011). When flexible routines meet flexible technologies: Affordance, constraint, and the imbrication of human and material agencies. MIS Quarterly, 35(1), 147. https://doi.org/10.2307/23043493

- Leong, C., Ling, M., & Ractham, P. (2015). ICT-enabled community empowerment in crisis response: Social media in thailand flooding 2011. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 16(3), 174–212. https://doi.org/10.17705/1jais.00390

- LifeWayResearch. (2020). Pastors’ Views on how COVID-19 is Affecting their Church April 2020. http://lifewayresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Coronavirus-Pastors-Full-Report-April-2020-LifeWay-Research.pdf

- Lombard, M., & Ditton, T. (1997). At the heart of it all: The concept of presence. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 3(2). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.1997.tb00072.x

- Majchrzak, A., & Markus, M. L. (2013). Technology affordances and constraints theory (of MIS). In E. H. Kessler (Ed.), Encyclopedia of management theory (pp. 832–836). SAGE Publications, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452276090.n282

- Massimi, M., & Neustaedter, C. (2014). Moving from talking heads to newlyweds - exploring video chat use during major life events. Proceedings of the 2014 conference on designing interactive systems - DIS ’14, 43–52. ACM Press. https://doi.10.1145/2598510.2598570

- McKenna, K. Y. A., & Bargh, J. A. (2000). Plan 9 from cyberspace: The implications of the internet for personality and social psychology. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 4(1), 57–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327957PSPR0401_6

- Mirbabaie, M., & Zapatka, E. (2017). Sensemaking in social media crisis communication – A case study on the Brussels bombings in 2016. Proceedings of the 25th European conference on information systems, Guimarães, Portugal, 2169–2186.

- Morstatter, F., Pfeffer, J., Liu, H., & Carley, K. M. (2013). Is the sample good enough? Comparing data from Twitter’s streaming API with Twitter’s firehose. Proceedings of the 7th international conference on weblogs and social media, ICWSM 2013, 400–408. AAAI.

- Müller, O., Junglas, I., Vom Brocke, J., & Debortoli, S. (2016). Utilizing big data analytics for information systems research: Challenges, promises and guidelines. European Journal of Information Systems, 25(4), 289–302. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejis.2016.2

- Müller, O., Junglas, I. A., Debortoli, S., & Vom Brocke, J. (2016). Using text analytics to derive customer service management benefits from unstructured data. MIS Quarterly Executive, 14(4), 243–258. https://aisel.aisnet.org/misqe/vol15/iss4/4

- Mupinga, D. M. (2005). Distance education in high schools: Benefits, challenges, and suggestions. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 78(3), 105–109. https://doi.org/10.3200/TCHS.78.3.105-109

- Neustaedter, C., & Greenberg, S. (2012). Intimacy in long-distance relationships over video chat. Proceedings of the 2012 ACM annual conference on human factors in computing systems - CHI ’12, 753-762. ACM Press. https://doi.10.1145/2207676.2207785

- O’Flaherty, K. (2020a). Microsoft knocks zoom out of the park with new features. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/kateoflahertyuk/2020/06/13/microsoft-knocks-zoom-out-of-the-park-with-new-features-you-need-now/

- O’Flaherty, K. (2020b). Zoom just made these powerful COVID-19 security and privacy moves following outcry. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/kateoflahertyuk/2020/04/02/zoom-just-made-these-powerful-covid-19-security-and-privacy-moves-following-outcry/

- Olson, J., Appunn, F., Walters, K., Grinnell, L., & McAllister, C. (2012). The value of webcams for virtual teams. International Journal of Management & Information Systems, 16(2), 161–171. https://doi.org/10.19030/ijmis.v16i2.6915

- Perez, S. (2020). Videoconferencing apps saw a record 62M downloads during one week in March. TechCrunch. https://techcrunch.com/2020/03/30/video-conferencing-apps-saw-a-record-62m-downloads-during-one-week-in-march

- Porath, S. L. (2018). A powerful influence: An online book club for educators. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education, 34(2), 115–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/21532974.2017.1416711

- Raffle, H., Go, J., Spasojevic, M., Revelle, G., Mori, K., Ballagas, R., Buza, K., Horii, H., Kaye, J., Cook, K., & Freed, N. (2011). Hello, is grandma there? let’s read! StoryVisit. Proceedings of the 2011 annual conference on human factors in computing systems - CHI ’11, 1195-1204. ACM Press. https://doi.10.1145/1978942.1979121

- Reuters. (2020). Zoom takes lead over microsoft teams as virus keeps Americans at home: Apptopia. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-zoom/zoom-takes-lead-over-microsoft-teams-as-coronavirus-keeps-americans-at-home-idUSKBN21I3AB

- Riemer, K., & Johnston, R. B. (2012). Place-making: A phenomenological theory of technology appropriation. Proceedings of the 33rd International conference on information systems, Orlando, FL, USA.

- Sarker, S., & Sahay, S. (2003). Understanding virtual team development: An interpretive study. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 4(1), 1–38. https://doi.org/10.17705/1jais.00028

- Saunders, C., Wiener, M., Klett, S., & Sprenger, S. (2017). The impact of mental representations on ICT-related overload in the use of mobile phones. Journal of Management Information Systems, 34(3), 803–825. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421222.2017.1373010

- Scharber, C. (2009). Online book clubs: bridges between old and new literacies practices. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 52(5), 433–437. https://doi.org/10.1598/JAAL.52.5.7

- Schmiedel, T., Müller, O., & Vom Brocke, J. (2019). Topic modeling as a strategy of inquiry in organizational research: A tutorial with an application example on organizational culture. Organizational Research Methods, 22(4), 941–968. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428118773858

- Seidel, S., Recker, J., & Vom Brocke, J. (2013). Sensemaking and sustainable practicing: Functional affordances of information systems in green transformations. MIS Quarterly, 37(4), 1275–1299.

- Smith, H. A., & McKeen, J. D. (2011). Enabling Collaboration with IT. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 28, 16. https://doi.org/10.17705/1CAIS.02816

- Stieglitz, S., Brachten, F., Ross, B., & Jung, A.-K. (2017). Do social bots dream of electric sheep? A categorisation of social media bot accounts. Proceedings of the 28th Australasian Conference on Information Systems, Hobart, Australia.

- Stieglitz, S., Mirbabaie, M., Ross, B., & Neuberger, C. (2018). Social media analytics – Challenges in topic discovery, data collection, and data preparation. International Journal of Information Management, 39, 156–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2017.12.002

- Strong, D., Volkoff, O., Johnson, S., Pelletier, L., Tulu, B., Bar-On, I., Trudel, J., & Garber, L. (2014). A theory of organization-EHR affordance actualization. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 15(2), 53–85. https://doi.org/10.17705/1jais.00353

- Tscherning, H. (2012). A multilevel social network perspective on IT adoption. In Y. Dwivedi, M. Wade, & S. Schneberger (Eds.), Information Systems Theory (pp. 409–439). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-6108-2_20

- Tyre, M. J., & Orlikowski, W. J. (1994). Windows of opportunity: Temporal patterns of technological adaptation in organizations. Organization Science, 5(1), 98–118. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.5.1.98

- Uebelacker, L., Dufour, S. C., Dinerman, J. G., Walsh, S. L., Hearing, C., Gillette, L. T., Deckersbach, T., Nierenberg, A. A., Weinstock, L., & Sylvia, L. G. (2018). Examining the feasibility and acceptability of an online yoga class for mood disorders. Journal of Psychiatric Practice, 24(1), 60–67. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRA.0000000000000286