ABSTRACT

Options thinking is a powerful approach for managing uncertainty and change in digital environments. It is recognised as a structured process for identifying, developing, and realising options into novel products and services. At Volvo Cars, we have learned it can also become a powerful instrument for innovation renewal, although it can be difficult to apply because it challenges existing firm practices. We elaborate this tension by presenting digital options strategizing as a process of applying options thinking to negotiate capability gaps and configure innovation resources. Our clinical study reveals that this facilitates innovation renewal through emergent processes, practice-oriented design, and opportunity-driven management.

1. Introduction

Over the last decade, digital technology has triggered massive transformations of new product development (Hinings et al., Citation2018; Nambisan et al., Citation2017; Yoo et al., Citation2012). The momentum and speed of these shifts caught most firms off guard. At Volvo Cars, we have used digital technology for decades to streamline internal processes and improve the price-performance ratio of our components. However, the broad digitalisation of society in the 2010s started putting pressure on our organisation, product designs, and business models in ways we had not seen before. Like most other product developing firms, we had to approach digital technology differently. Although we did not know it at the time, we had to recombine, expand, and substitute our resource bases in radically new ways and for new purposes (Henfridsson et al., Citation2018; Yoo et al., Citation2010; Zammuto et al., Citation2007). Therefore, we have made massive investments to master digital innovation over the last decade. We have deeply transformed the organisation for agility and change (Denning, Citation2020), reinforced digital competence (Mankevich & Svahn, Citation2021), developed new business models (Tannou & Westerman, Citation2012), and recently restructured our executive management teamFootnote1 to meet the challenges of digitalisation. These efforts have taught us an important lesson about digital innovation: capability to change knowledge, routines, and designs trumps capability to retain and reinforce (Kane et al., Citation2014). This insight came at a price for an automaker like us because it required us to regard uncertainty as a permanent and natural condition of innovation.

Options thinking is a powerful tool for addressing the inherent uncertainty of digital innovation (Kulatilaka & Venkatraman, Citation2001; Sambamurthy et al., Citation2003). Digital options provide strategic flexibility by generating future decision rights, thereby allowing alternative paths to be kept open. The greater the uncertainty, the more important this flexibility is (Vanhaverbeke et al., Citation2008, p. 252). However, it is difficult for incumbents like us to implement digital options thinking because existing norms and practices make it difficult to accommodate digital technology (Smith & Beretta, Citation2020). At Volvo Cars we have a strong legacy of practicing waterfall processes and linear modes of development. Therefore, rather than keeping alternative innovation paths open, we instinctively seek to close them, to align organisational resources and remove complexity. This paper does not focus on options per se but presents our experiences of how options thinking can help address such tensions and renew existing innovation practices. Specifically, it asks how can digital options thinking support innovation renewal in incumbent firms?

We report a clinical inquiry (Schein, Citation1987, Citation2008) into connected car innovation in which we learned that connected car innovation created uncertainties that existing innovation practices could not handle (problem); introduced options thinking as a structured approach for manoeuvring uncertainty (intervention); and used options thinking to negotiate capability gaps, reconfigure resources, and deploy these resources to renew digital innovation capabilities (outcome).

2. Innovation renewal and digital options

Digital technologies tend to remain ‘incomplete‘ and in a state of flux. Additionally, they diffuse easily across traditional industry boundaries and allow distributed and heterogeneous actors to innovate outside the direct control of a primary firm (Nambisan et al., Citation2017). Consequently, digital innovation exposes existing firms such as Volvo Cars to deep uncertainty. While our traditional innovation practices involve manoeuvring risk, i.e., assessing probabilities of known alternative innovation paths, we are ill-equipped to deal with currently unknown paths. To address the inherent uncertainty of digital innovation, incumbents must accept the idea that innovation processes cannot be defined upfront and must instead be constantly renewed. We thus have to develop dynamic capabilities for building, integrating, and reconfiguring internal and external innovation resources to sense, seize, and transform opportunities as they materialise (Teece et al., Citation2016). The agility this requires can be shaped using digital options (Fichman et al., Citation2005; Sambamurthy et al., Citation2003).

In this context, options thinking is an iterative approach for managerial reflection that can be understood in terms of a lifecycle (Sandberg et al., Citation2014), a chain (Bowman & Hurry, Citation1993), or a series of interlinked stages (Kulatilaka & Venkatraman, Citation2001) in which available options for digital innovation are identified, made actionable, and selectively realised. First, firms have to invest in the capacity to recognise and assess opportunities for growth. In digital innovation, where products and services are not defined up-front, identification of available options is difficult and associated with substantial uncertainty. With limited understanding of future market conditions, it is critical to remain open-minded and recognise potential benefits beyond current business propositions. In the second stage of the option lifecycle, firms make small “investments” in the most promising opportunities. These investments are intended to facilitate and expedite future decision-making, and may result in prototypes, demonstrators, market intelligence, and more. As firms engage in such development of actionable options they gain “the right, but not the obligation, to take an action in the future” (Amram & Kulatilaka, Citation1999, p. 5). Put differently, digital options provide agility (Sambamurthy et al., Citation2003) or strategic flexibility (Vanhaverbeke et al., Citation2008), “by generating future decision rights” (p. 252). The value of this flexibility increases with the level of uncertainty, so digital options must be continuously re-evaluated. The value of a digital option may decrease as market conditions shift, so at some point, the firm should stop investing further in its development. Alternatively, changing markets may provide appropriate conditions for moving on to the final stage of the cycle, where options are activated. By realising options into products or services, the “right” to act is finally exercised.

3. Research engagement

The clinical research reported in this paper follows the methodological guidelines of clinical inquiry developed by Edgar Schein (e.g., Schein, Citation1987, Citation2008). Clinical inquiry is an action research method in which the researcher’s involvement is recognised as an intervention into ongoing client practices. As explained in the Appendix, it differs from mainstream action research in that “the initiative remains at all times with the client” (Schein, Citation1995, pp. 2–3). This legitimises the research in client’s eyes and helps build a trustful environment. Once this trustful relationship is built “the door is open for the researcher to seek additional data based in part on a greater willingness of the clients to provide data that they might otherwise wish to withhold” (Schein, Citation2008, p. 267).

This paper reports a clinical inquiry into digital options thinking in the context of connected cars and centres on Volvo Cars’ Connectivity Hub. Established by the executive team in 2010, this Hub played an important role in how we came to embrace digital innovation (Svahn et al., Citation2017). As a company, we had been experimenting with telematics solutions for over a decade, primarily to reinforce our safety agenda. With the introduction of iOS and Android in 2007, we began rethinking connectivity. The ripple effects of Apple and Google’s products spread through our industry, and it became apparent that their combination of remote access, openness, and capacity to change functionality independently from hardware opened up radically new innovation paths for cars. These insights stirred the whole automotive industry: Ford partnered with Microsoft, BMW initiated a collaboration with Apple, and both suppliers and automakers investigated Google’s Android platform. Inspired and to some extent alarmed by these initiatives, our executive management team established a temporary unit – the “Connectivity Hub” – to strategize digital innovation in the area of connected cars. Mastering new digital technologies would be challenging in itself, but early investigations suggested that novel connected car innovations would also require the firm to establish new forms of collaboration and set aside existing innovation practices. To take on this challenge, the Hub was directed to creatively rethink existing organisational resources. The appointed Hub director described this initial task as follows:

The main job was to establish a new network that didn’t reflect the existing organization, but the different stakeholders expected to be involved in the design or use of connected cars … The Hub was an opportunity to bring different parts of the firm to the same table. Before, we didn’t have an integrated forum where we could discuss those things.

The Hub came to represent diversity in competence and experience (). The members were high-ranking managers with a genuine belief in car connectivity and its potential to make Volvo a stronger brand. They were up-to-date with automotive trends, eager to discuss, and willing to question existing norms and practices. The executive team considered the Hub members excellent change agents who could create a new strategy for connected cars.

Table 1. The connectivity Hub.

4. The clinical research process

4.1. Phase I: deconstructing innovation uncertainty

The newly formed Connectivity Hub faced a serious problem: it could not decide how company resources should be used to handle the uncertainties of connected car innovation. Although its members had invested considerable time and effort into explaining the generative potential of connectivity, colleagues kept asking what specific functions connectivity would enable and when these functions could be integrated into Volvo’s cars. However, market volatility, the pace of technological change, and rigid innovation practices made it difficult to offer relevant answers:

The main problem is that we believe in this [though we lack solid arguments]! The question is: Did Google and others doing similar things see the revenue upfront? Or did they just have the guts to do it? (Product Manager, Infotainment)

To better understand how the apparent uncertainty of digital technology created this deadlock, the Hub (represented by the second author) invited an external researcher (the first author) to two co-created workshops during 2010 (). The researcher introduced a few theoretical perspectives and examples from other industries to facilitate problematisation of the resistance facing Hub members in their efforts to reconfigure organisational resources. While the discussions in these workshops reflected optimism about the potential of connectivity, Hub members also expressed frustration because their inability to assess (and communicate) uncertainty and risk triggered organisational resistance. To manage risk, our established innovation practices relied on long-range planning, proven technologies, and infrequent product releases. However, these practices were incompatible with car connectivity, which requires continuous development, external collaborations, and end-user involvement. In such volatile digital innovation, the dominant risk was not doing things the wrong way but doing completely wrong things. Traditional risk management was thus an inappropriate tool for assessing connectivity:

We never make [proper] risk assessments. We’re doing the basic math, but what if things turn out to be better than expected, or worse? What are the leverage effects? We never make such assessments. (Director Infotainment Engineering)

Table 2. Overview of the clinical inquiry at Volvo Cars.

The first phase of the clinical inquiry established that connectivity brought uncertainties the company’s existing innovation processes could not handle. These uncertainties called for an emergent process () in which features and services are generated in an open-ended manner rather than defined up-front. If implemented successfully, such a process could reduce organisational resistance by not calling for precise answers concerning innovation outcomes. However, to engage a highly institutionalised workforce in largely unbounded innovation renewal we had to develop an alternative innovation process and learn from a steady stream of ideas about future capabilities to frame new organisational and technological resources that could be exercised to generate new innovation capabilities.

4.2. Phase II: contextualising innovation uncertainty

Although the first phase energised the Hub, it also made Hub members pause and reflect on knowledge deficits, limiting their ability to deal with uncertainties of connected car innovation. During the spring of 2011 the Hub director and the first author discussed how the connectivity agenda could be advanced and initiated a second phase of clinical inquiry, which was structured as a series of workshops held during August-September 2011 (). Essentially, this phase was a response to Hub members’ perceptions:

We can’t make sense of these things! We don’t know how to play with platforms and communities to inform connected car innovation. (system designer, Accessories)

Our ability to understand the emergent aspects of connected car innovation was clearly hampered by an unreflective view on innovation. To help clients distance themselves from product innovation practices and appreciate uncertainty in context of a digital innovation logic, the researcher proposed three thematic workshops on open innovation, platforms, and two-sided markets. In each workshop, the clients studied selected, topic-specific articles and then discussed how their concepts could be applied in emergent innovation. The exploration of alternative innovation logics for connected cars was intended to reduce the inertia facing incumbents adapting to technological changes by encouraging Hub members to identify existing or new resources that could produce new digital innovation capability.

These explorations confirmed that Volvo Cars had to prioritise new forms of value creation over protecting things such as market share or profit margins. The readings triggered discussions on controversial innovation paths including knowledge sharing and open access to car resources. While the workshops provided few solutions, they clearly demonstrated a need to shift the focus of our innovation efforts. To manoeuvre in uncertain innovation environments, we had to broaden our resource base: rather than focusing on a few internal resources, to increase efficiency we also had to engage broadly with external resources that were better suited for continuous generation of novel applications and services.

4.3. Phase III: acknowledging options thinking

To facilitate a shift towards external collaboration, the researcher organised a third phase of clinical inquiry in the form of four workshops held between October 2011 and March 2012. Hub members noted that the emerging ecosystems around Android and iOS demonstrated an unprecedented pace of change and diversity. As the Product Marketing Strategy manager put it, shifting attention outwards would require us to develop new capabilities for quickly scanning and assessing opportunities in these ecosystems:

We will never be able to catch that accelerating train, but somehow, we need to get a feeling for its speed.

The third phase of inquiry used scenario planning to experiment with alternative developments for connected cars and explore opportunities and threats provided by these developments. In that sense, scenario planning became an instrument for mapping uncertainty in external environments (). This was mainly done using the “Shell method” (Schoemaker, Citation1993), which has five stages: (1) defining a key question, (2) identifying and clustering driving forces, (3) prioritising driving forces, (4) generating scenarios, and finally (5) evaluating scenarios. During scenario planning, the participants discussed current trends and prospects in the external environment. These discussions repeatedly returned to the question of how to get hold of, transform, and recombine various external resources to develop new innovation capability. The Hub members understood that the diversity and volatility of such externally defined opportunities would increase risks unless Volvo Cars could learn how to manage them:

For me this initiative was an eye-opener. I’ve learned that I need to consider more external variables when making decisions. Now, I’m aware of the range of those variables. (Hub Director)

To facilitate discussions on how to deal with uncertainty and delay decision-making the researcher introduced options theory (Fichman et al., Citation2005; Sambamurthy et al., Citation2003). Although options theory was initially received as a complex framework, this intervention allowed Hub members to visualise connected car innovation as an open-ended process of renewal for exploring future innovation capabilities and evaluating them in relation to existing capabilities. As the third phase unfolded, options thinking took centre stage while scenario planning faded into the background. While Hub members could appreciate scenario planning as an instrument for exploring an uncertain future, it was perceived as speculative. Options thinking, in contrast, was recognised as an instrument for structured, concrete manoeuvring of uncertainty. As Hub members engaged with the concept they adopted a cyclic view on options thinking (as described in section 2). Throughout the four workshops they observed that (1) the uncertainty of digital innovation requires capabilities for identifying available options, (2) the pressing need to re-evaluate decisions as markets change requires capabilities for developing actionable options, and (3) rapid introduction of digital products and services requires capabilities for realising options. Reflecting on the third phase of clinical inquiry Hub members saw important progression. As described by the enterprise architect manager, they saw digital options thinking as a useful tool that allowed them to strategize collectively:

We’ve created a shared value system through our discussions. Although we’re not a formal unit in the organization we’re a lot tighter now … In effect, we’ve built a shared [organizational] platform for the Hub network.

4.4. Phase IV & V: unpacking options thinking for innovation renewal

The researcher conducted two follow-up studies (2014 and 2021) to evaluate how the main intervention – injecting options thinking as a structured approach for manoeuvring uncertainty – was applied and developed for innovation renewal. The first study (phase IV), based on follow-up interviews with Hub members, captured the initial moves towards options thinking. The intervention is strongly linked to the study’s outcome because many of these initiatives were spearheaded by Hub members returning to their normal duties. The second contemporary study (phase V) took a broader view and focused on document sources rather than interviews in search for patterns of options thinking across the organisation. It departed from innovation capabilities identified in the first follow-up study, and evaluated how they were reflected in contemporary processes. In that sense, it demonstrated how the early initiatives extends into today’s agile processes and elaborated connectivity as a driver in Volvo Cars’ innovation renewal. The following sections present selected findings from the follow-up studies as an integrated narrative.

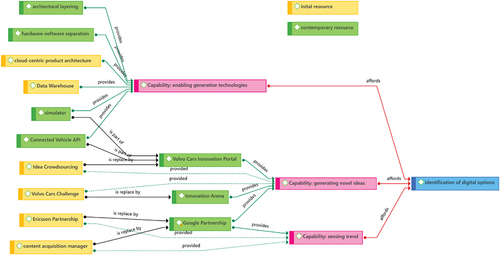

4.4.1. Identifying digital options

Other industries, particularly consumer electronics (smartphones, videogames, TVs, etc.), have provided substantial inspiration for car connectivity. To increase our capability of sensing trends in these related markets, we initially hired a content acquisition manager who followed the consumer electronics market, identified connected car opportunities, and acted as a broker towards the rest of the organisation (). To identify digital options we also partnered with Ericsson on cloud technology in 2014. This collaboration provided deep insights into a critical domain, and we saw Ericsson as “a perfect partner for Volvo Cars, bringing extensive experience and global technology understanding to the table”.Footnote2 As our capability of sensing trends increased, we uncovered sources of uncertainty. Alternative trajectories became visible to many, rather than just a few, and, as a company, we could manoeuvre them more systematically. Today, Google is our ear to the ground. As expressed by our senior vice president for R&D, close collaboration with this tech giant allows us to “embrace a rich ecosystem” and “offer hundreds of popular apps and the best integrated experience in this broad, connected environment”.

While sensing trends remain important, this mutually beneficial collaboration with Google has made us more proactive. We are now less anxious about missing out on external trends and more focused on generating novel ideas. This capability provided managerial power in that we could actively direct creativity to niches with recognised uncertainty. In 2013–2104, we tested innovation contests as a way to identify digital options in the automotive context. With “Volvo Cars Challenge” we targeted established partners in the automotive industry. In the first event we focused on “UX” – user experience – and invited participants to create “innovation within the area of connected services to bridge the connected home to car”. Another initiative – the Volvo Idea Hub – was a Facebook-based, global crowdsourcing initiative in which members of the public were invited to help shape the future of connected cars. Over one million people saw the launch and thousands participated by submitting new ideas about smartphone connectivity apps. In a press release, we stated that “almost all ideas aim to simplify everyday life; everything from having the app suggest the best route to work, to find parking, to help find your lost car keys”.

As of 2021 idea generation is institutionalised through an innovation arena, supporting internal innovation. According to our intranet, this arena is:

based on the idea that innovation is a companywide matter. A matter that cannot be centralized, but a competence that needs to be spread, and shared. An arena is an open construct, not for the selected few but a place of participation reaching beyond Volvo Cars.

We also built an innovation portal to engage external stakeholders in idea generation. The portal includes open data sets, a connected vehicle API, a simulator, and other creative resources that give Volvo Cars the capability to enable generative technologies. Sharing such resources provides creative leeway for third-party developers and allows us to carefully direct them towards useful digital options.

In the early days we made some important moves to expose digital in-car resources. For example, we invested in a new cloud-centric product architecture. As explained by the Hub director, we developed a “data warehouse to support this cloud solution and [to avoid compromising security] we integrate new security functions – in both cars and the back-end – to prevent intrusion”. The architectural principles we developed have largely remained intact, although we have invested significantly in hardware-software separation and made the car architecture increasingly layered.

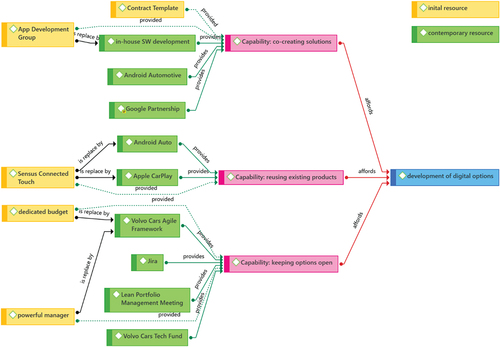

4.4.2. Developing digital options

As our capability to identify digital options grew, we learned that most options will remain out of reach unless developed in concert with existing products, organisational structures, and business models. Developing an option makes it actionable, i.e., prepared for rapid market introduction. In that sense, it is a matter of exploring uncertainties related to the realisation of particular options and outline approaches for handling them. We considered it particularly important to develop digital options for popular smartphone apps such as Spotify or TuneIn. Therefore, in 2013, we introduced Sensus Connected Touch (SCT), an Android-based infotainment platform for the aftermarket that allowed us to easily modify existing apps for operation via the steering wheel controls and in-car voice interaction (). The SCT thus made identified options actionable, increasing our capability for reusing existing products. SCT has since been retired but we have extended this capability by integrating Android Auto and Apple CarPlay, enabling convenient access to mobile phone applications.

While these solutions allow existing applications to be used in the car, they force us take a backseat position with limited influence over creative processes or business models. To create room for manoeuvring in such volatile and uncertain environments, we established the “App Development Group” in 2013. It was created to provide capability for co-creating solutions with external stakeholders. The group was set up as an internal organisational resource, embedded within R&D, to connect internal product innovation to external ecosystems. The group quickly grew to approximately 30 people with experience in telecoms, mobile handsets, and service provisioning. As it gained momentum, we discovered that co-development of apps resonated poorly with existing purchasing practices. We knew that our standard supplier contracts might be difficult for small startup firms to handle, but as noted by the group founder, another aspect took us by surprise:

We make in-car applications together but normally we are not exchanging any money. Volvo is not a customer. We are not providing revenue for those companies. Spotify sells to someone else, like the end-user. TuneIn makes money on commercials, meaning they have another customer.

Companies like Volvo Cars typically negotiate purchasing contracts based on economic transactions, but these co-development initiatives did not include such exchanges. To develop digital options in this way we had to prepare new contract templates, regulating collaboration rather than economic transactions and emphasising equal rights and responsibilities.

While neither the App Development Group nor the contract template are used today, these initial moves helped us develop and adopt in-house software development, where external stakeholders are collaborators rather than suppliers. Our collaboration with Google, where we enable connectivity through the in-car operating system Android Automotive, is an excellent illustration. We develop digital options together, in a trustful and creative manner, despite our divergent business models:

Our relationship with Google is excellent! We collaborate organically - a lot of people at Volvo talk to a lot of people at Google. We share source code, and other things, in a really open way […] Decision-making is also highly organic. When we disagree we push things to a higher level. It works really well! Culturally, we are surprisingly compatible. (Head of Digital Business)

This collaboration is a powerful way of handling uncertainty in that it helps us manoeuvre a broad range of digital options in parallel. However, the idea of keeping options open was initially provocative. In an organisation like ours, R&D is typically project-driven and engineering pre-studies rapidly exclude alternatives to focus attention on the industrialisation of a few specific products. When we launched the App Development Group, it was located within R&D to coordinate internal and external innovation. However, to avoid being steamrolled by the rest of the organisation, it had to be protected. Therefore, the executive team agreed to give the app developers extensive autonomy. The Hub director recalled with relief: “For the first time we have a separate app development budget that is not a part of the overall vehicle projects. Product planning has not been able to control it, so we decide how to use it”. This dedicated budget, together with the appointment of an experienced and powerful manager, created leeway in the development of digital option portfolios. Today, such protection is unnecessary because we have established the Volvo Cars Agile Framework and, as stated in the 2019 annual report, rapidly adopted it across our organisation:

During 2019 we have continued to roll out agile and lean methodology throughout large parts of the company, changing the roles and ways of working for thousands of our employees.

Although the framework is now widely adopted, the former Content Acquisition Manager (now Head of Digital Business) was clear about its genesis: “it all started with connectivity”.

To create transparency, we adopted tools such as Jira (tool for agile project management) and established Lean Portfolio Management Meetings (LPMM) to evaluate and make decisions about our five option portfolios. To keep options open we also launched Volvo Cars Tech Fund as a resource for investing in potentially transformative technologies.

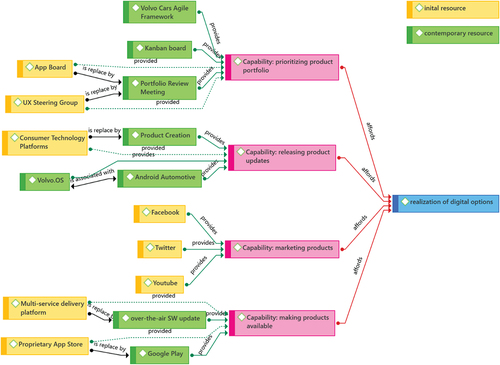

4.4.3. Realising digital options

Digital options thinking is a powerful instrument for manoeuvring uncertainty, but we learned that unless actionable options can be rapidly transformed into products and services efforts may be in vain. At Volvo Cars, it became increasingly clear that we needed to rethink our decision-making processes for connectivity. We traditionally distributed decision-making over the organisational hierarchy, across functionally disconnected and relatively autonomous departments. While that strategy was effective for developing cars, it was inefficient for the cross-functional domain of connectivity because deciding whether to realise an option involved many departments and therefore stressed our organisation. Consequently, we pushed decisions upwards in the hierarchy, slowing the process down.

Realisation of options requires the capability of repeatedly prioritising the product portfolio. To establish this capability, we created the “App Board”, which the Hub director described as “a cross-functional setup” in which “IT, marketing, customer service, R&D, and product management come together every Friday morning to discuss new apps and functions to be realized using apps” (). This organisational resource was tailored-made for rapid realisation of digital options. However, decisions about apps often required complex interrelated judgements concerning driving safety, design experience, and user interaction. Therefore, to accelerate the decision-making process, we launched another initiative called the UX Steering Group involving the directors of electrical engineering, sales, and design. Looking back on these initiatives with pride, the Hub director said “[now] we can make decisions without pushing it all the way to the CEO or ending up making [unauthorized] low-level decisions”. These learnings have shaped the contemporary Volvo Cars Agile Framework, which was designed to “reduce hierarchies that are slowing down decision-making and execution”.Footnote3 For example, this framework includes a Portfolio Review Meeting whose participants have the authority to make critical decisions about our 5 option portfolios, and Kanban boards to provide an overview of the background for these decisions.

Realisation of digital options also requires the capability to continuously release product updates, which we initially found difficult. We learned that a portfolio of continuously changing connectivity apps would not survive within our existing waterfall-based cycle plans because it would be steamrolled by car projects. In the spring of 2013, we responded to this challenge by creating a new Consumer Technology Platforms organisational unit in the IT department with explicit responsibility for maintaining connectivity apps. The unit’s manager explained its purpose as follows:

R&D is project-oriented. They design a car, leave it for production, and shift focus to the next car. They don’t do maintenance. They address quality problems, but they’re not structured for continuous support or delivery. As part of the IT department, we now have that kind of structure in place [for connectivity apps].

This organisational resource handed product responsibility to the IT department for the first time and has now become institutionalised: the former IT department now works closely with R&D in a new organisational branch called Product Creation. This move helps us manoeuvre uncertainty in that it facilitates the continuous release of new connectivity functions using the Android Automotive platform and, in future, our brand-new Volvo.OS.

The realisation of digital options also involves diffusion and adoption. Whereas physical cars are released in distinct model years, we learned that connectivity apps must be delivered directly to customers at the time of release. To shortcut existing practices and build new capabilities for making products available, we explored several new technological resources. To rapidly distribute in-car content, we launched a proprietary app store for the SCT platform. We also adopted Ericsson’s Multiservice Delivery Platform to build ”a global cloud-based solution” that could “enable efficient provision and communication of services and information to the cars”.Footnote4 These resources are now retired, and we rely on Google Play to distribute externally developed apps. Since early 2021 we have also been able to push our own native applications via over-the-air software downloads. This resource creates room for manoeuvring uncertainty in that “a new Volvo is no longer at its finest when it leaves the factory, but keeps improving over time”.Footnote5

Finally, we have explored social media to build new capabilities for marketing products. As a result, a YouTube channel, a Twitter feed, a Facebook page, and an Instagram account all became important resources for realising digital options. To create network effects on these social media platforms we collaborated with artists and athletes including Robyn, Swedish House Mafia, and Zlatan Ibrahimovic, and have also experimented with communities to create media buzz around car connectivity.

5. Discussion

Previous publications have described the funnelling of diverse digital growth opportunities into novel products and services through the process of identifying, developing, and realising digital options (e.g., Kulatilaka & Venkatraman, Citation2001; Sambamurthy et al., Citation2003). Digital options are an important part of our journey towards connected cars. For example, we identified several different options for web radio, developed solutions for a handful, and realised a few into commercial Volvo services. In this paper, however, the options take a backseat. Instead, it focuses on how options thinking helped us renew our innovation capability, referred to as digital options strategizing.

Digital options strategizing rests on the accepted idea that resources and capabilities define a firm’s competitive advantage. It treats resources as stocks of assets that are owned or controlled by the firm, while capabilities are the firm’s capacity to deploy these resources to deliver products or services (Amit & Schoemaker, Citation1993; Grant, Citation1991). However, it also recognises that digital technologies transform the interplay between resources and capabilities because they radically change the nature of operations, products, and services (Nambisan et al., Citation2017; Yoo et al., Citation2012, Citation2010). This paper presents digital options strategizing as a recursive process of innovation renewal, relying on options thinking to negotiate capability gaps, reconfigure resources, and deploy those resources to realise new digital innovation capabilities ().

Our study reveals that digital options thinking can facilitate innovation renewal in several ways. First, it promotes emergent (i.e., ongoing) discussions about requisite and existing innovation capabilities. Clearly articulating requisite capabilities helped us identify digital options. However, when identifying options we immediately began assessing what would be needed to develop them, and when developing options we discussed what we would need to realise them. Digital options strategizing recognises this reciprocity by emphasising that the option lifecycle shapes and is shaped by the negotiation of capability gaps, which can be defined as the “distance[s] between needed capabilities and the firm’s existing capability base” (Capron & Mitchell, Citation2009, p. 295). Second, we learned that digital options thinking necessitates practice-oriented capability gap negotiation. For example, the capability to co-create solutions became vital to our work but it was not developed for any strategic purpose; rather, it emerged from efforts to resolve practical difficulties with TuneIn and Spotify. Similarly, we did not build the capability to prioritise product portfolios in order to launch agile processes but to resolve pressing issues with existing decision-making practices. These negotiations created a shared understanding of tasks, established norms, and drove mutual engagement (Wenger, Citation1999). Third, digital options thinking promotes opportunity-driven rather than problem-driven negotiation of capability gaps. This approach to negotiating capability gaps is called backcasting to emphasise its contrast with forecasting. Forecasting is problem-driven because it departs from existing capabilities: firms first systematically evaluate present conditions, then determine how these conditions resonate with future environmental conditions and identify capabilities needed to fill any gaps (problems) that are anticipated. Conversely, backcasting is opportunity-driven because capability gaps are negotiated by first envisioning a requisite capability (an opportunity) and then determining how it can be realised in relation to existing capabilities (i.e., the feasibility of exploiting the opportunity). That is to say, firms start with a desired future state and try to determine what to do in the present to reach that state (Dreborg, Citation1996). Backcasting is thus concerned “not with what futures are likely to happen, but with how desirable futures can be attained” (p. 814). The negotiation of capability gaps through backcasting is exemplified by the App Development Group: we realised that co-creation with external developers could be hugely beneficial for connectivity but this approach was poorly supported by the existing organisation. To fill this capability gap, we cloned proven external app development practices and created the necessary conditions (e.g., new contractual templates and a powerful manager) to embed the group into our R&D structure.

Digital options strategizing also involves systematically reconfiguring innovation resources. This is vital for innovation renewal because the deployment of resources may irreversibly shift a firm’s innovation trajectory (Oborn et al., Citation2019). In other words, it marks a new path that will influence the development of future resources (Henfridsson & Yoo, Citation2014). For example, our investment in Sensus Connected Touch allowed us to develop and realise options for in-car access to mobile apps. This in turn allowed us to subsequently reconfigure our resource base to support Android Auto and Apple CarPlay. Digital options strategizing recognises this reciprocity by emphasising that the option lifecycle shapes and is shaped by the firm’s resource base. In that sense, it is better understood as an emergent and open-ended resourcing process rather than in terms of traditional resource management. The notion of resourcing directs attention to how assets are brought into use and calls for the adoption of a practice perspective whereby resources allow people to enact schemas (e.g., norms or rules of thumb). Resourcing is the in-practice creation of assets and relationship qualities (trust, authority, etc.) that make enactment possible (Feldman, Citation2004). Through the connected car initiative we learned the meaning of such practice-oriented resource reconfiguration. Conventional wisdom is that a firm’s resources offer a sustained competitive advantage if they are rare, hard to imitate, and without equivalent substitutes (Barney, Citation1991). In this view, it makes sense to keep the firm’s resource base close to the chest. However, such protective practices are simply incompatible with digital innovation. We have therefore reconfigured architectures and developed cloud solutions to expose rather than hide in-car resources, shared knowledge through innovation contests and innovation arenas, and redesigned contracts to encourage co-creation rather than securing profit margins. By bringing resources into use (without detailed plans for using them to create new capabilities) we created a shared resource repertoire (Wenger, Citation1999) that allows Volvo Cars to manage the uncertainties of digital innovation in collaboration with others. We have found that these collaborations often materialise outside the boundaries of the firm. To detect opportunities and capture value, resourcing activities must target loosely coupled external ecosystems (Suseno et al., Citation2018). Digital options strategizing promotes this kind of opportunity-driven resource reconfiguration because it directs managerial attention to external innovation environments and offers a structured approach for managing internal resources to leverage external assets. This is exemplified by our collaboration with Google, through which we became one of the first automakers to integrate Android Automotive into our cars. By providing deep access to the car architecture – which creates considerable security challenges – we helped Google develop support for the increasingly important driving context. In return, we can now enjoy the full benefits of the Android innovation ecosystem. We are not limited to passively identifying options but can actively co-create automotive applications with Android developers. Developing options is thus a matter of ensuring architectural support, while realising options comes down to decision-making.

This paper reports a clinical inquiry into connected car innovation. Clinical research is powerful in that it delves into authentic settings, defined by the clients rather than the researcher. With clients taking centre stage, trustful relationships develop quickly, which opens doors for the researcher and offers unique opportunities to clarify what is really going on. However, in clinical research it is challenging to establish direct links between interventions and outcomes. This paper accounts for how the connectivity Hub engaged in problematisation, intervention, and how the Hub members then implemented a range of initial initiatives to apply options thinking across the organisation (phase IV). At this level of analysis, the individuals made a link between interventions and outcomes. The paper then provides a broader overview to find patterns of options thinking in the contemporary organisation (phase V). Our company is a global organisation with 40000 employees. That means,40000 agents, continuously assessing the firm’s competitive edge, and acting, with the resources they have, to improve it. It is important to underline that causality between interventions and outcomes cannot be established in such a complex environment. However, our paper confirms the presence of options thinking, it demonstrates how the early initiatives extends into today’s agile processes, an it elaborates the importance of connectivity as a driver in Volvo Cars’ transformation towards these agile processes.

Digital options thinking is an instrument to funnel rich and varied but uncertain opportunity spaces into novel products and services. Our research demonstrates that it can also be a powerful engine in the open-ended, creative process of (1) negotiating compromise between requisite and existing innovation capabilities and (2) reconfiguring internal and external innovation resources. Our clinical study thus suggests that digital options strategizing contributes innovation renewal in that it fosters emergent rather than planned processes, practice-oriented rather than function-oriented design, and opportunity-driven rather than problem-driven management.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (65.9 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/0960085X.2022.2088415.

Notes

1. Press release, March 14, 2019

2. Press release January 7 2014.

3. Press release April 29 2020.

4. Press release December 17 2012.

5. Press release February 25 2021.

References

- Amit, R., & Schoemaker, P. J. H. (1993). Strategic assets and organizational rent. Strategic Management Journal, 14(1), 33–46. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250140105

- Amram, M., & Kulatilaka, N. (1999). Real options: Managing strategic investment in an uncertain world (Vol. 4). Harvard Business School Press Boston.

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700108

- Bowman, E. H., & Hurry, D. (1993). Strategy through the option lens: An integrated view of resource investments and the incremental-choice process. The Academy of Management Review, 18(4), 760–782. https://doi.org/10.2307/258597

- Capron, L., & Mitchell, W. (2009). Selection capability: How capability gaps and internal social frictions affect internal and external strategic renewal. Organization Science, 20(2), 294–312. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1070.0328

- Denning, S. (2020, January 26). Why and how Volvo embraces agile at scale. Forbes.

- Dreborg, K. H. (1996). Essence of backcasting. Futures, 28(9), 813–828. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-3287(96)00044-4

- Feldman, M. S. (2004). Resources in emerging structures and processes of change. Organization Science, 15(3), 295–309. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1040.0073

- Fichman, R. G., Keil, M., & Tiwana, A. (2005). Beyond valuation: “Options Thinking” in IT project management. California Management Review, 47(2), 74–96. https://doi.org/10.2307/41166296

- Grant, R. M. (1991). The resource-based theory of competitive advantage: Implications for strategy formulation. California Management Review, 33(3), 114. https://doi.org/10.2307/41166664

- Henfridsson, O., & Yoo, Y. (2014). The liminality of trajectory shifts in institutional entrepreneurship. Organization Science, 25(3), 932–950. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2013.0883

- Henfridsson, O., Nandhakumar, J., Scarbrough, H., & Panourgias, N. (2018). Recombination in the open-ended value landscape of digital innovation. Information and Organization, 28(2), 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infoandorg.2018.03.001

- Hinings, B., Gegenhuber, T., & Greenwood, R. (2018). Digital innovation and transformation: An institutional perspective. Information and Organization, 28(1), 52–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infoandorg.2018.02.004

- Kane, G. C., Johnson, J., & Majchrzak, A. (2014). Emergent life cycle: The tension between knowledge change and knowledge retention in open online coproduction communities. Management Science, 60(12), 3026–3048. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2013.1855

- Kulatilaka, N., & Venkatraman, N. (2001). Strategic options in the digital Era [Article]. Business Strategy Review, 12(4), 7–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8616.00187

- Mankevich, V., & Svahn, F. (2021). Resourcing digital competence in product development. Proceedings of the 54th Hawaii international conference on system sciences.

- Nambisan, S., Lyytinen, K., Majchrzak, A., & Song, M. (2017). Digital innovation management: reinventing innovation management research in a digital world. MIS Quarterly, 41(1), 223–238. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2017/41:1.03

- Oborn, E., Barrett, M., Orlikowski, W., & Kim, A. (2019). Trajectory dynamics in innovation: developing and transforming a mobile money service across time and place. Organization Science, 30(5), 1097. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2018.1281

- Sambamurthy, V., Bharadwaj, A., & Grover, V. (2003). Shaping agility through digital options: Reconceptualizing the role of information technology in contemporary firms. MIS Quarterly, 27(2), 237–263. https://doi.org/10.2307/30036530

- Sandberg, J., Mathiassen, L., & Napier, N. (2014). Digital options theory for IT capability investment. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 15(7), 422–453. https://doi.org/10.17705/1jais.00365

- Schein, E. H. (1987). The clinical perspective in fieldwork. SAGE Publishing.

- Schein, E. H. (1995). Process consultation, action research and clinical inquiry: Are they the same? Journal of Managerial Psychology, 10(6), 14–19. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683949510093830

- Schein, E. H. (2008). Clinical inquiry/research. In P. Reason & H. Bradbury (Eds.), Handbook of action research (2 ed., pp. 266–279). SAGE Publications.

- Schoemaker, P. J. H. (1993). Multiple scenario development: Its conceptual and behavioral foundation. Strategic Management Journal, 14(3), 193–213. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250140304

- Smith, P., & Beretta, M. (2020). The gordian knot of practicing digital transformation: Coping with emergent paradoxes in ambidextrous organizing structures*. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 38(2): 166–191. doi:10.1111/jpim.12548.

- Suseno, Y., Laurell, C., & Sick, N. (2018). Assessing value creation in digital innovation ecosystems: A social media analytics approach. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 27(4), 335–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsis.2018.09.004

- Svahn, F., Mathiassen, L., & Lindgren, R. (2017). Embracing digital innovation in incumbent firms:How Volvo cars managed competing concerns. MIS Quarterly, 41(1), 239–253. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2017/41.1.12

- Tannou, M., & Westerman, G. (2012). Volvo cars corporation: Shifting From a B2B to a “B2B+ B2C” Business Model. MIT Sloan School of Management.

- Teece, D., Peteraf, M., & Leih, S. (2016). Dynamic capabilities and organizational agility: Risk, uncertainty, and strategy in the innovation economy [Article]. California Management Review, 58(4), 13–35. https://doi.org/10.1525/cmr.2016.58.4.13

- Vanhaverbeke, W., Van de Vrande, V., & Chesbrough, H. (2008). Understanding the advantages of open innovation practices in corporate venturing in terms of real options. Creativity and Innovation Management, 17(4), 251–258. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8691.2008.00499.x

- Wenger, E. (1999). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge university press.

- Yoo, Y., Henfridsson, O., & Lyytinen, K. (2010). Research commentary: The new organizing logic of digital innovation: An agenda for information systems research. INFORMATION SYSTEMS RESEARCH, 21(4), 724–735. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.1100.0322

- Yoo, Y., Boland, R. J., Lyytinen, K., & Majchrzak, A. (2012). Organizing for innovation in the digitized world. Organization Science, 23(5), 1398–1408. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1120.0771

- Zammuto, R., Griffith, T., Majchrzak, A., Dougherty, D., & Faraj, S. (2007). Information technology and the changing fabric of organization. Organization Science, 18(5), 749–762. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1070.0307