ABSTRACT

The triad of entrepreneurship, self-employment, and financial inclusion underpins policy and development interventions meant to address the youth employment challenge in Africa. Youth savings groups are being widely promoted as a first step toward financial inclusion and economic empowerment. This article reports on the links between income-generating activities of 57 members of youth savings groups in Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, and Ghana, and their membership in savings groups. It concludes that while savings groups can help to facilitate operational expenses and cash flow – and thus support members’ micro-enterprises – in opportunity starved contexts their transformational potential is probably being oversold.

La triade constituée de l'entrepreneuriat, du travail indépendant et de l'inclusion financière étaye les interventions de politique et de développement qui visent à traiter de la question du chômage chez les jeunes en Afrique. Les groupes d'épargne de jeunes sont largement promus en tant que première étape de l'inclusion financière et de l'autonomisation économique. Cet article rend compte des liens entre les activités génératrices de revenus de 57 membres de ces groupes en Tanzanie, en Ouganda, en Zambie et au Ghana, et leur appartenance à ces groupes. Il avance, dans sa conclusion, que si les groupes d'épargne peuvent aider à faciliter les dépenses opérationnelles et les flux de trésorerie – et par-là, soutenir les microentreprises des membres – dans les contextes privés d'opportunités, leur potentiel transformationnel est probablement survendu.

La tríada capacidad empresarial, autoempleo e inclusión financiera apuntala las intervenciones de políticas públicas y de desarrollo orientadas a hacer frente a la elevada tasa de desempleo entre los jóvenes de África. Como paso inicial hacia la inclusión financiera y el empoderamiento económico, se han promocionados ampliamente los grupos de ahorradores jóvenes. El presente artículo da cuenta de los vínculos existentes entre las actividades generadoras de ingresos en las que participan 57 integrantes de grupos de ahorradores jóvenes de Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia y Ghana, y el hecho de ser miembro de estos grupos. En este sentido, se concluye que, si bien los grupos de ahorradores pueden facilitar la realización de ciertos gastos operativos y los flujos de caja —asegurando a las microempresas de sus miembros— en contextos yermos de oportunidades, es posible que se haya exagerado su potencial de transformación.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

In recent years increasing research and policy attention has been paid to the over-representation of young people among the unemployed and underemployed in Africa (AfDB, OECD, UNDP, and UNECA Citation2012; PRB Citation2013). In a continent where 200 million people (approximately 20% of the population) are aged 15 to 24 (Agbor, Taiwo, and Smith Citation2012), Africa’s young population is seen by some as the source of a potential demographic dividend, if only it can be “managed well” (i.e. integrated into the economy so as to contribute to growth) (Kilara and Latortue Citation2012, 1). However, if not managed well, Africa’s “youth bulge” is also seen as a potential liability linked to political instability (Agbor, Taiwo, and Smith Citation2012, 9).

It is in this context of a “youth employment crisis” (ILO Citation2012) that national governments and international development agencies are now prioritising young people and particularly their access to economic opportunities (FAO, CTA, and IFAD Citation2014; MasterCard Foundation Citation2015; USAID Citation2012). With limited growth in formal sector jobs, the focus has turned very much toward self-employment and small-scale entrepreneurship within the informal sector as a route into remunerative work (Gough and Langevang Citation2016; Langevang, Namatovu, and Dawa Citation2012).

This article is about the links between financial inclusion and livelihoods of poor young people. We follow the OECD in defining financial inclusion as “providing access to an adequate range of safe, convenient and affordable financial services to disadvantaged and other vulnerable groups, including low income, rural and undocumented persons, who have been underserved or excluded from the formal financial sector” (FATF Citation2011, 12). Our specific focus is on youth savings groups as these are promoted as a means of instilling the habit of savings and providing access to financial services to young people in the developing world.

Informed in part by four decades of experience with and (contested) lessons from microfinance (Banerjee et al. Citation2013; Bateman and Chang Citation2012; Sinclair Citation2012; Yunus Citation2003), many observers suggest that a lack of access to financial services, particularly among young people, limits the scope for successful entrepreneurship (CAFOD Citation2013; Fine et al. Citation2012; Markel and Panetta Citation2014). Indeed, according to much recent literature on financial inclusion, young people have especially low rates of access to financial services. For example, Kilara and Latortue (Citation2012, 1–2) state that young people aged 15 to 24 are 33% less likely to have a bank account than adults, and only 4.2 million of the 800 million young people globally living on less than US$2 per day have access to financial services. Various explanations have been put forward, including an unfavourable regulatory environment (where young people under a certain age are often not allowed to open their own bank account); geographic access and lack of mobility; a lack of financial product information; and high fees (Friedline and Rauktis Citation2014; Johnson et al. Citation2015). Mader (Citation2016) provides a provocative analysis that questions three key assumptions underpinning the current interest in financial inclusion: that there is a causal relationship running from financial inclusion to developmental outcomes and broader benefits; that the extension of financial services is directly beneficial to the poor; and that there is an untapped business opportunity in providing financial services to the poor.

It is in this context that some NGOs promote the use of savings groups as a means of providing young people with financial services. Informal savings groups are seen as a “springboard” to financial inclusion, fostering good savings behaviour and asset accumulation (Smith, Scott, and Shepherd Citation2015, 7). One particularly important claim about savings groups is that:

[l]ivelihoods of households and entire communities have been transformed by the power of members knowing that at any time they can call on savings, credit, and insurance benefits in a manner that is flexible, appropriate to their situation, and set in an administrative and social culture where they feel understood and valued. (Allen and Panetta Citation2010, 5)

To date, the experiences of young members of mixed-age savings groups, or members of youth-specific savings groups, have received only limited research attention (Flynn and Sumberg Citation2016, Citation2017). Nevertheless, some large international NGOs, including Plan International and CARE International, have put youth savings groups at the centre of their youth-oriented activities (Plan International UK Citation2016). Plan UK suggests that youth savings groups are attractive to and appropriate for young people since they are simple and easy to understand, and they emphasise small and regular deposits, participatory management, and do not pressurise members to borrow often or in large amounts (Markel and Panetta Citation2014). Youth savings groups provide experiential learning about finance and are “an ideal starter system for youth” (Markel and Panetta Citation2014, 8).

It is important to note that it is not the first time that development programmes have sought to combine access to (micro)finance with the promotion of entrepreneurship. While in the past supporters of such programmes have come to see them as “nothing less than the most promising instrument available for reducing the extent and severity of global poverty” (Snodgrass Citation1997, 1), others have painted a different picture. Bateman and Chang (Citation2012), for example, argued that the microfinance model is likely to keep people in a poverty trap because the addition of microenterprises in what is already usually a saturated informal sector increases competition for the limited amount of available resources, thereby reducing the returns and viability of such enterprises. The poor are also not able to start or expand their microenterprises through microfinance, for example, by investing in and using more sophisticated technology, given that the returns are usually over the longer term, or small-scale farmers simply cannot produce enough surplus to pay back the high interest rates from microfinance institutions. This is an important aspect of what Dichter (Citation2006) described as the “paradox of microcredit” – “the poorest people can do little productive with the credit, and the ones who can do the most with it are those who don’t really need microcredit, but larger amounts with often longer credit terms” (4).

Apart from the problematic link between access to finance and entrepreneurship, a recent review of self-employment interventions targeted at young people published by the International Labour Organization (ILO) cast doubt on the emphasis on self-employment. Specifically, it found that while self-employment can serve as a coping mechanism for individuals and families to generate income in contexts where few economic or employment options exist, “promoting self-employment is probably not a particularly effective policy mechanism by which to promote upward social mobility or reduce poverty” (Burchell et al. Citation2015, 35).

Based on research undertaken with members of youth savings groups in four African countries, in this article we argue that there is a disjuncture between the claims that are made about the links between financial inclusion, entrepreneurship, and income generation on the one hand, and the experience of many savings group members on the other. We believe this disjuncture is due in large part to the low opportunity environments in which many (especially rural) Africans live, and the low skill, low technology, low return activities in which many young people are consequently engaged. Though financial inclusion via savings groups and entrepreneurship may help some members cope with precarity and help “tak[e] the edge off poverty” (Adams and Vogel Citation2016, 152), for example by helping to steady the cash flow needed to operate and benefit from what are typically small-scale economic activities, we find that they are simply not sufficient, at least in the short term, to transform the livelihoods of young people in these environments.

The article is structured as follows. The next section provides a description of our research methodology. We then present findings on the income-generating activities undertaken by members of youth savings groups, and the roles that loans and shareouts from the savings group play in these activities. The term shareout refers to the distribution of all savings, plus accrued interest, to the individual members of a savings group at the end of a “savings cycle” (typically between six and 12 months). The final section discusses the implications of these findings. We conclude by suggesting that the assumptions underpinning the promotion of youth savings groups need to be critically examined, particularly as they relate to the potential role of savings groups in supporting positive transformation of youth livelihoods through income-generating activities.

Methodology

The data used in this article were collected as part of an academic partnership between the Banking on Change (BoC) programme and the Institute of Development Studies (IDS) (Flynn and Sumberg Citation2016). BoC was a joint programme involving Plan International, CARE International, and Barclays Bank. It supported access to financial services by mobilising individuals from opportunity constrained communities into savings groups so they could regularly save and borrow. BoC promoted itself as savings rather than credit-led, and aimed to support members to build assets at their own pace. From 2013 to 2015 the programme had a particular focus on young people. In addition to savings groups, BoC provided training in financial education, enterprise, and employability skills and as appropriate created links to formal finance. BoC operated in seven countries: Egypt, Ghana, India, Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia. By the end of 2015, when it closed, it had established around 11,000 youth savings groups involving some 240,000 members.

Fieldwork took place between April 2015 and August 2015 in Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, and Ghana. Two BoC savings groups were identified in each country for inclusion in the research (). All groups were at least into their second savings cycle, and three were into their third cycle. Information was gathered through group discussions and detailed interviews with 57 individual savings group members. Interviewees were selected from among the original group members specifically to include different saving and borrowing patterns, but in making the selections we were also mindful of their age and sex, and whether they had participated in the baseline survey. The strategy used to identify savings groups and group members, as detailed in Flynn and Sumberg (Citation2016), was meant to capture the diversity of members and savings and borrowing patterns, rather than to arrive at a representative sample. We also analysed savings and borrowing activities as recorded in group ledger books and individual passbooks. In total, over the eight groups, the ledger books and pass books allowed us to construct indicators of savings and loan activity for 280 individuals (these data are not reported here; see Flynn and Sumberg Citation2016).

Table 1. The Banking on Change youth savings groups.

The interviews were open-ended and explored the individual’s income-generating activities, family situation, motivations for joining the group, savings and use of loans and shareouts, training received, challenges, and possible improvements to the model. On average, interviews lasted approximately 1.5–2 hours. Given the small-scale and seasonal or intermittent nature of most of the income-generating activities, and a lack of written records, no systematic attempt was made to estimate the level of turnover or profit associated with individual activities. Notes from the interviews were entered into MS Word and then imported into Nvivo and coded, which allowed information pertaining to particular questions, issues, or discussion points to be easily extracted and analysed.

BoC targeted people up to the age of 35, but focused on those under the age of 25 (Plan International UK Citation2016). Although all the interviewees were between the ages of 13 and 36, and most were considered “youth” by the BoC project, they were nevertheless in very different socio-economic situations. For example, while some were students living at home, with few domestic responsibilities, others had children, were in relationships, or were operating one or more income-generating activities. In order to take account of the diversity in the analysis we categorised interviewees according to their responsibilities for children, and whether or not they had a partner with whom they might share parenting responsibilities; students were put into a separate category. In total five categories were identified ().

Table 2. Distribution of interviewees according to category and gender.

Findings

Types of income-generating activities

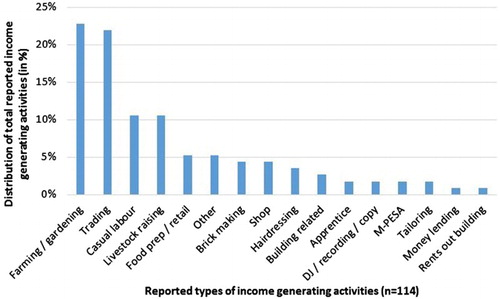

We start by providing an overview of the types of income-generating activities engaged in by savings group members. The 57 interviewees reported being involved in 114 income-generating activities (). The number of activities per interviewee ranged from none (this was the case for six interviewees, five of whom were students with the other having recently completed junior high school) to five. The mean and median number of activities per interviewee was two.

These income-generating activities mainly included small-scale agriculture and livestock rearing, casual farm labour, mud block and charcoal making, small-scale food preparation, services like hair plaiting, and petty trade. Activities like these are typical of many parts of rural Africa, where economic opportunities are constrained. In such settings, income-generating activities are often characterised by low barriers to entry, low skill, low investment, and operation at a small scale.

For example, a 16-year-old female student in Zambia (ID 39, Cat. 1) sold sweets to her classmates at school. A 22-year-old married mother in Uganda (ID 18, Cat. 5) traded charcoal and farmed a 1.25-acre plot which belonged to her husband’s family, and rented another 1.5-acre plot. Maize, cassava, and potatoes provided her with some food for household consumption and some income. She estimated selling three basins of charcoal (a basin is about the size of a large suitcase) per week. Sometimes she ran out of both crops and charcoal to sell. A 19-year-old single man in Uganda (ID 19, Cat. 2) said that he generated income as a DJ and through farming, brick making, and livestock raising. He performed as a DJ at least once per weekend, and sometimes during the week as well, using his own computer (but renting out the sound system). He farmed a 0.5-acre plot of his parents’ land, producing mainly maize and cassava, some of which was sold. He also reported making a pile of bricks which he was still waiting to sell. He used a loan from the savings group to treat some piglets he had purchased, but they all died. He had still not been able to achieve his goal when joining the savings group, which was to purchase his own sound system. A 20-year-old mother in Uganda (ID 25, Cat. 5) farmed and traded charcoal and fish. She started her fish trading activity three years ago with a small amount of capital she had set aside from doing casual labour, and now traded fish four days a week (when the market was open). She started trading charcoal through a loan from the savings group because she “didn’t want to be idle on the days where she wasn’t trading fish”. She farms with her husband, but they do not grow enough food to satisfy their own household consumption. Similar to these examples, the vast majority of the income-generating activities were small-scale, informal, low skill, low technology, low investment, and low return.

There were, however, a few examples that did not fit this pattern. A 20-year-old single man (ID 10, Cat. 2) worked as a house painter. He had two employees of his own and signed formal contracts with clients, particularly for larger jobs. He also received cash advances to help pay for materials, and had clients in his village and in the surrounding area. A 30-year-old married woman (ID 5, Cat. 5) living in Dar es Salaam ran a shop and bar. She started the shop with her husband using funds he had saved from his work as a carpenter. In addition to the doughnuts she makes, she sells water, ugali (maize) flour, and other items in the shop; and she had recently established the bar. A 25-year-old single man (ID 14, Cat. 2) bought maize through traders from various regions in Tanzania, milled the grain and sold the flour to small shops in the surrounding area. He reported using a small loan to pay for transportation to the Tanga area to conduct “research” (specifically to identify cheaper suppliers); his ambition was to open a wholesale shop. A 22-year-old single man (ID 33, Cat. 2) was trading charcoal before using a shareout to buy a computer and printer to establish a copy shop and recording studio. He also recently started a carpentry business in the same location.

A disaggregated view of income-generating activities

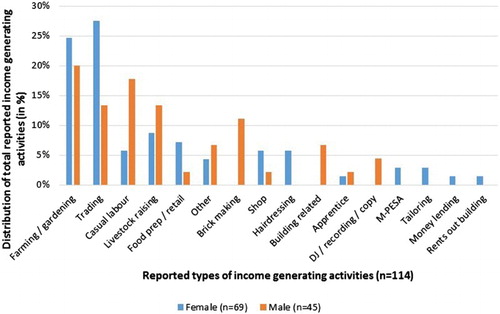

This section presents a disaggregated view of income-generating activities. shows the distribution of all income-generating activities by gender of interviewee. While farming (including commercial gardening) was equally important for both females and males, engagement in other economic activities was more or less strongly gendered. For example, female interviewees more commonly engaged in trading, food preparation and selling, hairdressing, and shopkeeping, while males were more likely to engage in casual labour (typically agricultural wage labour) and livestock raising. Brick making and building-related activities were only undertaken by males.

In the remainder of this section we first explore differences in the income-generating activities of female interviewees across the different categories referred to earlier (since only women were well represented throughout these categories), and then look at sex differences in the types of reported income-generating activities for the categories with significant representations of both female and male interviewees, that is for students (Cat. 1) and for interviewees who were “working, without children, without a partner” (Cat. 2). The 34 female interviewees in Categories 1, 2, 4, and 5 were involved in a total of 66 income-generating activities (). Three activities – trading, farming, and food preparation – formed a strong common core across all categories, accounting for between 54% of activities for interviewees in Cat. 2 and Cat. 4, to 68% for those in Cat 5. There was little difference in the scale of trading activities across these categories, and few signs of growth over the approximately one and a half to two-year timespan covered by the interviews. The scale of farming also varied little, with the vast majority of interviewees farming no more than 2 acres, usually on their partner’s or parents’ land.

Table 3. Income-generating activities of female interviewees, by category.

Beyond this common core, interviewees with children but no partner (Cat. 4) were more likely to engage casual labour. In contrast, those with fewest domestic responsibilities (Cat. 1 and 2) were more likely to engage in livestock rearing. All livestock activities were small-scale: interviewees in Cat. 1 were raising a few chickens, while the two Cat. 2 interviewees both bought and raised one goat (which in one case had given birth to two kids). Members had thus not been able, in the time covered by the interviews, to amass any significant livestock assets. Finally, nearly a quarter of the activities of Cat. 5 interviewees (with children and a partner) involved either hairdressing or running a small shop. A number of these individuals reported that they established these activities with assistance from a spouse or partner.

We proceed to analysing the income-generating activities by gender among students (Cat. 1) and the members who were “working, without children, without a partner” (Cat. 2). Thirteen of the 18 student interviewees engaged in a total of 25 income-generating activities, including casual labour, livestock rearing, farming, and trading (). With the exception of livestock raising, which both male and female students did, a strong gender division is apparent, with female students engaging in farming and trading, and male students in casual labour. Again, the activities were predominately small-scale and often intermittent: for example, some reported selling sweets at school, or eggs in the market on the weekend, while farming was mainly undertaken during school holidays. Livestock raising was also at a small scale (no more than one goat or one to two chickens), the exception being an 18-year-old male student from Zambia (ID 31) who was keeping two goats and three chickens. He said he had been able to acquire his livestock by raising chicks from chickens he bought after a harvest, and selling some of them to buy goats.

Table 4. Income-generating activities of Category 1 interviewees (students), by gender.

We now turn to Cat. 2 interviewees, who were “working, without children, without a partner”. This is an important category because these individuals are just starting out: they have limited domestic responsibility, but neither do they benefit from the potential support of a partner. The 15 interviewees in this category reported engaging in a total of 38 income-generating activities (). Both males and females were involved in trading, farming, and livestock raising, and together this common core accounted for 56% and 69% of activities reported by males and females respectively. Some activities, including food preparation, hairdressing, and money lending, were only reported by females, while others including brick making, casual labour, and building-related activities, were only reported by males.

Table 5. Income-generating activities of Category 2 interviewees (working, without children, without a partner), by gender.

The trading activities undertaken by female interviewees were again small-scale and revolved principally around food, including fish, tomato, and palm oil. A 22-year-old single female from Dar es Salaam (ID 22) said she was involved in a one-time foray into fashion, buying and selling four handbags. Male interviewees were involved in trading blankets, charcoal, coffee, maize, and chickens. For both males and females, investments in and income from trading were generally limited, although two of the five males reported trading more significant volumes. A 25-year-old from Tanzania (ID 14) said he sold ten 180-kilogramme bags of maize per week, while a 22-year-old from Zambia (ID 33) reported selling 100 or so bags of charcoal every few months.

No gender-related differences could be discerned in relation to either the types of crops grown or the scale of farming activities. On the other hand, female interviewees reported rearing single goats, while males reported rearing multiple (e.g. three) pigs or chickens.

Savings groups and income generation

In this section we ask the question, how have the savings groups been used to support these income-generation activities? Overall, 189 cases of loan use and 105 cases of shareout use were reported – 62% of cases of loan use and 28% of cases of shareout use were associated with interviewees’ income-generating activities. The greater use of loans to support income generation may reflect the fact that the financial literacy training that most interviewees received through the BoC project emphasised the need to use loans “productively”. For example, one member (ID 34, a 27-year-old single mother of two) recognised that a challenge within her group was that some people “still don’t borrow for productive purposes” (which hinders members’ abilities to repay the loans and which consequently reduces the amount of money available for borrowing), despite the fact that members had been told by the trainers to invest in things such as assets. In contrast, most shareouts were used to meet household expenses, such as groceries, children’s education, land (for housing), and home improvements such as metal roofing sheets and furniture, especially mattresses.

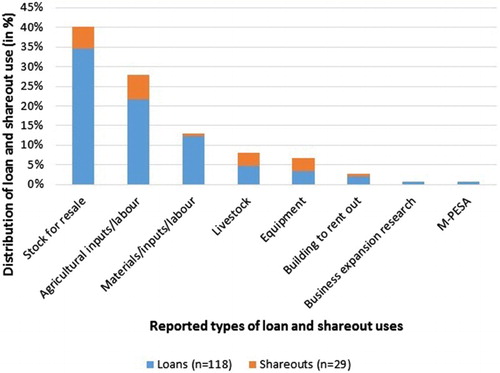

The vast majority (81%) of loans and shareouts that were used to support income-generating activities were used to cover operational expenses: either to purchase stock (e.g. fish, charcoal, or other items to resell) or inputs for different activities (e.g. fertiliser, seeds, labour for farming; firewood for charcoal making; or flour and other ingredients for doughnut or samosa making) ().

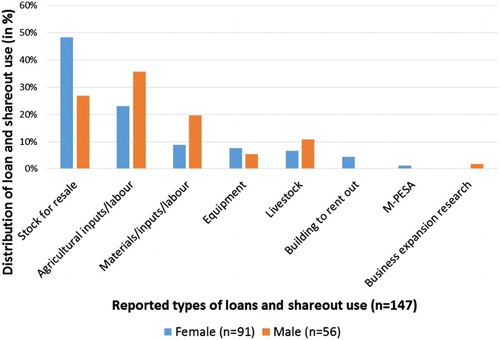

Females used both loans and shareouts to purchase stock for resale (48% of loan and shareout use), while the single most important use of loans and shareouts by males was for farming (36 percent of loan and shareout use). There were few examples of loans or shareouts being invested in new skills, technology or equipment ().

Among the 34 females in Categories 1, 2, 4, and 5, 89 loan and shareout uses were reported (). The purchase of stock for resale and of agricultural inputs and labour accounted for the majority of uses across all categories. Outside this common core, interviewees with fewer domestic responsibilities (Cat. 1 and 2) purchased livestock, while only four female interviewees, all of them with both children and a partner, invested in equipment.

Table 6. Loan and shareout use of female interviewees, by category.

Within categories, eight of 18 students (44%) reported 12 loan and shareout uses. Both male and female students used loans and shareouts to purchase stock for resale, agricultural inputs and labour, other materials and labour, and livestock. The number of cases is limited, but there is little indication of consistent gender-based differences in the way loans and shareouts were used by the students. The same is true for Cat. 2 interviewees (working, no children, not with a partner), thirteen of whom reported 55 uses of loans and shareouts to support their income-generating activities (). Again, a strong common core of uses is apparent, including purchase of stock for retail, agricultural inputs and labour, and to a lesser extent, livestock.

Table 7. Loan and shareout use of Category 2 interviewees (working, no children, not with a partner), by gender.

A small number of examples of the use of loans and shareouts to support income-generating activities were identified that did not fit the patterns described above. These included a 25-year-old single man from Tanzania (ID 14, Cat. 2) who bought maize through traders from various regions in Tanzania, milled the grain and resold the flour to small shops in the surrounding area. He mentioned using a small loan to pay for transport to visit the Tanga area to try to identify cheaper suppliers, which he described as conducting “research”. Another interviewee, a 22-year-old single man from Zambia (ID 33, Cat. 2) bought a computer and printer to set up a copy shop and recording studio, and also a pool table from which he hoped to generate income (though he was ultimately unable to use his pool table as it was irreparably damaged during shipment). Finally, a 28-year-old married doughnut maker from Uganda (ID 16, Cat. 5) used a shareout to buy a bicycle to increase the range and number of customers he could reach; he was observed carrying his doughnuts through the village on the bicycle.

Beyond this, a few interviewees also reported buying equipment in order to initiate activities at a later date. For example, a 21-year-old married woman from Dar es Salaam (ID 3, Cat. 5) bought a fridge for a “kef” activity she wanted to start (a kef is a small snack bar); she planned on investing additional money from the savings group to buy the equipment she was still missing, including tables and chairs. Another married woman from Dar es Salaam (ID 7, Cat. 5) had used three loans to buy equipment for a hair salon she wanted to open; she intended on using the money from her next shareout to rent space for the salon.

Discussion and conclusions

In the previous sections we presented data on the income-generating activities of 57 members of youth savings group from Tanzania, Zambia, Uganda, and Kenya, and their use of loans and shareouts. Four key points emerge from this analysis. First, the vast majority of the income-generating activities were small scale, involved little technology, investment or skill, and therefore generally had very low barriers to entry. Only a handful did not fit this description. Second, trading, farming, and livestock rearing formed the strong common core of income-generating activities across male and female interviewees; while trading and farming formed a common core that united women across the different categories. Third, the vast majority of loans and shareouts used to support these income-generating activities went toward the purchase of stock for trading or inputs such as fertiliser and labour. In other words, they were being used primarily for operational expenses and cash flow management. There were only a few examples of investment in skills, capital goods, or technology upgrading. Fourth, while all interviewees were members of “youth” savings groups, it is clear that in addition to any savings group effect, their income-generating activities reflect their different ages, responsibilities, and social positions.

Thus, the picture that emerges is very similar to that painted by Bateman and Chang (Citation2012). In opportunity starved contexts, where small-scale income-generating activities typically receive only modest investment, the creation or expansion of these kinds of activities tends to increase competition for resources and income, thereby restricting the viability and growth of such activities. In these contexts, therefore, the transformational potential of savings groups, and financial inclusion more generally, is limited, at least in the short term. This signals the need for a critical re-evaluation of the “entrepreneurship–self-employment–financial inclusion” triad that is now so central to policy and development programme responses to the youth employment challenge.

None of this is to say that savings groups may not be valuable in supporting young people’s income-generation activities and their efforts to build their livelihoods. For members and their families, savings groups may provide an additional way to access and distribute usually small quantities of cash, without which it might be more difficult to sustain their economic activities and generate income through trade, farming, or investing in assets such as land and livestock. But, however important this may be, it is far from the general claim that informal savings groups can underpin a revolution in local economic activity.

Yet, there are other possible ways to think about savings groups, which put less emphasis on the short term or direct link with income generation. For example, it may be that the real benefits of membership are in terms of learning, behavioural change (being more business minded, controlling expenses, and restricting “youthful” behaviour), building social capital, and the possible slow but steady accumulation of assets. Our research provided a number of examples that pointed in this direction. If this is the case, benefits and impacts of participation in youth savings groups would probably need to be evaluated on a 5–10-year time horizon.

Another possibility that is worth exploring is that, following Ferguson (Citation2015), in some contexts work is more about establishing and pressing claims to resources than about income generation per se. From this perspective, participation in the savings group and being seen to be applying one’s self through work, allows young people to both press their distributive claims (i.e. to parents’ or siblings’ resources) and also to respond to the distributive claims of others (i.e. through the distribution of the loans and shareouts that arise from their participation in the savings groups, as demonstrated by Flynn and Sumberg Citation2017). In this light, it may be that instead of supporting enterprise development, savings groups help to solidify young people’s more intimate social networks, allowing them to cope in situations of economic precarity, including where the state and institutions at other levels are either absent or weak.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to the BoC partners, including Plan UK, CARE International, and Barclays, for their support during the course of this work. We also thank the two anonymous reviewers for their useful suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Justin Flynn is a Research Officer at the Institute of Development Studies (IDS) in the UK. He has a background in history and development and has work experience mainly relating to young people, savings groups, entrepreneurship, and employment in Africa.

James Sumberg is an agriculturalist by training. He currently works as a Research Fellow at IDS, where he leads the Rural Futures Cluster. His research presently focuses on young people, employment, and the emergence of the Livestock Revolution.

References

- Adams, D. W., and R. C. Vogel. 2016. “Microfinance Dreams.” Enterprise Development and Microfinance 27 (2): 142–154. doi: 10.3362/1755-1986.2016.010

- AfDB, OECD, UNDP, and UNECA. 2012. African Economic Outlook 2012. Special Theme: Promoting Youth Employment. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Agbor, J., O. Taiwo, and J. Smith. 2012. “Sub-Saharan Africa’s Youth Bulge: A Demographic Dividend or Disaster?” In Foresight Africa: Top Priorities for the Continent in 2012 (pp. 9–11). Washington, DC: The Africa Growth Initiative at The Brookings Institution.

- Allen, H., and D. Panetta. 2010. Savings Groups: What Are They? Washington, DC: The SEEP Network.

- Ashe, J., and K. J. Neilan. 2014. In Their Own Hands: How Savings Groups Are Revolutionizing Development. Oakland, CA: Berrett-Koehler.

- Banerjee, A., E. Duflo, R. Glennerster, and C. Kinnan. 2013. “The Miracle of Microfinance? Evidence from a Randomized Evaluation.” MIT Department of Economics Working Paper No. 13-09. Cambridge, MA: MIT.

- Bateman, M., and Ha-Joon Chang. 2012. “Microfinance and the Illusion of Development: From Hubris to Nemesis in Thirty Years.” World Economic Review 1: 13–36.

- Boonyabancha, S. 2001. “Savings and Loans; Drawing Lessons From Some Experiences in Asia.” Environment and Urbanization 13 (2): 9–21. doi: 10.1177/095624780101300202

- Burchell, B., A. Coutts, E. Hall, and N. Pye. 2015. “Self-employment Programmes for Young People: A Review of the Context, Policies and Evidence.” Employment Working Paper No. 198. Geneva: ILO.

- CAFOD. 2013. Thinking Small 2 – Big Ideas From Small Entrepreneurs: Understanding the Needs and Priorities of Small-Scale Farmers and Businesses Owners. London: CAFOD.

- Dichter, T. 2006. “Hype and Hope: The Worrisome State of the Microcredit Movement.” Accessed July 28, 2016. http://media.microfinancelessons.com/resources/microcredit_hype_and_hope.pdf

- FAO, CTA, and IFAD. 2014. Youth and Agriculture: Key Challenges and Concrete Solutions. Rome: FAO (in collaboration with CTA and IFAD).

- FATF. 2011. Anti-money Laundering and Terrorist Financing Measures and Financial Inclusion. Paris: The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

- Ferguson, J. 2015. Give a Man a Fish: Reflections on the New Politics of Distribution. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Fine, D., A. van Wamelen, S. Lund, A. Cabral, M. Taoufiki, N. Dorr, A. Leke, C. Roxburgh, J. Schubert, and P. Cook. 2012. Africa at Work: Job Creation and Inclusive Growth. New York: McKinsey & Company.

- Flynn, J., and J. Sumberg. 2016. Patterns of Engagement with Youth Savings Groups in Four African Countries. IDS Research Report 81. Brighton: IDS.

- Flynn, J., and J. Sumberg. 2017. “Youth Savings Groups in Africa: They’re a Family Affair.” Enterprise Development and Microfinance 28 (3): 147–161. doi: 10.3362/1755-1986.16-00005

- Friedline, T., and M. Rauktis. 2014. “Young People are the Front Lines of Financial Inclusion: a Review of 45 Years of Research.” Journal of Consumer Affairs 48 (3): 535–602. doi: 10.1111/joca.12050

- Gash, M., and K. Odell. 2013. The Evidence-Based Story of Savings Groups: a Synthesis of Seven Randomized Trials. Arlington, VA: The SEEP Network.

- Gough, K. V., and T. Langevang, eds. 2016. Young Entrepreneurs in Sub-Saharan Africa. London: Routledge.

- ILO. 2012. “The Youth Employment Crisis: A Call for Action.” Resolution and conclusions of the 101st Session of the International Labour Conference, Geneva, Geneva, International Labour Office (ILO), 2012.

- Johnson, L., Y. Lee, D. Ansong, M. Sherraden, G. Chowa, F. M. Ssewamala, L. Zou et al. 2015. Youth Savings Patterns and Performance in Colombia, Ghana, Kenya, and Nepal: YouthSave Research Report 2015. CSD Publication 15-01. St. Louis, MO: Center for Social Development (CSD).

- Karlan, D., B. Thuysbaert, C. Udry, E. Cupito, R. Naimpally, E. Salgado, and B. Savonitto. 2012. Impact Assessment of Youth Savings Groups: Findings of Three Randomized Evaluations of CARE Village Savings and Loan Associations Programs in Ghana, Malawi and Uganda. New Haven, CT: Innovations for Poverty Action.

- Kilara, T., and A. Latortue. 2012. Emerging Perspectives on Youth Savings. Focus Note 82. Washington, DC: CGAP.

- Langevang, T., R. Namatovu, and S. Dawa. 2012. “Beyond Necessity and Opportunity Entrepreneurship: Motivations and Aspirations of Young Entrepreneurs in Uganda.” International Development Planning Review 34 (4): 439–460. doi: 10.3828/idpr.2012.26

- Lowicki-Zucca, M., P. Walugembe, I. Ogaba, and S. Langol. 2014. “Savings Groups as a Socioeconomic Strategy to Improve Protection of Moderately and Critically Vulnerable Children in Uganda.” Children and Youth Services Review 47: 176–181. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.08.011

- Mader, P. 2016. Questioning Three Fundamental Assumptions in Financial Inclusion. IDS Evidence Report 176. Brighton: IDS.

- Markel, E., and D. Panetta. 2014. Youth Savings Groups, Entrepreneurship and Employment. London: Plan UK.

- MasterCard Foundation. 2015. Youth at Work: Building Economic Opportunities for Young People in Africa. Toronto: MasterCard Foundation.

- Plan International UK. 2016. The Banking on Change Youth Savings Group Model. London: Barclays Bank PLC, Plan UK, and CARE International UK.

- PRB. 2013. 2013 World Population Data Sheet. Population Reference Bureau (PRB). Accessed May 17, 2016. www.prb.org/publications/datasheets/2013/2013-world-population-data-sheet/data-sheet.aspx

- Sinclair, H. 2012. Confessions of a Microfinance Heretic: How Microlending Lost its Way and Betrayed the Poor. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

- Smith, W., L. Scott, and A. Shepherd. 2015. Financial Inclusion Policy Guide: Enhanced Resilience Through Savings and Insurance via Linkages and Digital Technology. Policy Guide No. 6. London: Chronic Poverty Advisory Network (CPAN).

- Snodgrass, D. 1997. Assessing the Effects of Program Characteristics and Program Context on the Impact of Microenterprise Services: A Guide for Practitioners. Assessing the Impacts of Microenterprise Services (AIMS) Brief 15. Washington, DC: US Agency for International Development.

- USAID. 2012. Youth in Development: Realizing the Demographic Opportunity. Washington, DC: USAID.

- Wilson, K., M. Harper, and M. Griffith, eds. 2010. Financial Promise for the Poor: How Savings Groups Build Microsavings. Sterling, VA: Kumarian Press.

- Yunus, M. 2003. Banker to the Poor: Micro-Lending and the Battle Against World Poverty. New York: PublicAffairs.