ABSTRACT

How can multi-stakeholder dialogue help assess and address the roots of environmental resource competition and conflict? This article summarises the outcomes and lessons from action research in large lake systems in Uganda, Zambia, and Cambodia. Dialogues linking community groups, NGOs and government agencies have reduced local conflict, produced agreements with private investors, and influenced government priorities in ways that respond to the needs of marginalised fishing communities. The article details policy guidance in four areas: building stakeholder commitment, understanding the institutional and governance context, involving local groups in the policy reform process, and embracing adaptability in programme implementation.

Introduction

The links between natural resources and conflict have received increasing attention over the last two decades. Research has shown that natural resources played a role in 40% of all intrastate conflicts in the last 60 years, and that the affected countries are twice as likely to relapse into conflict in the first five years following a settlement (Binningsbo and Rustad Citation2008). Much of this research has focused on the role of high-value resources such as oil, minerals, timber, and diamonds in creating and sustaining conflict, especially large-scale conflict. At the same time, competition over renewable resources such as land and water has also demonstrated significant conflict potential, especially at the local level. These local conflicts are frequent and impact the daily lives of many communities around the world (Rüttinger et al. Citation2012).

Research has also shown that natural resources have great potential to foster cooperation, transform or prevent conflicts, and build peace. Sustainable and equitable management of natural resources can prevent conflict, for example, by reducing grievances and building resilient livelihoods (UNEP Citation2009; Young and Goldman Citation2015). However, as populations increase, economies develop, and cities grow, the demand for natural resources is increasing – as are the negative impacts on the environment. In tandem, global climate change is predicted to bring large-scale impacts on water, land, and ecosystems, in many instances acting as a threat multiplier that increases the risk of local resource conflict (UNEP Citation2009; Rüttinger et al. Citation2015). This brings new urgency to the quest for approaches that transform the conflict potential of natural resources and harness their capacity to catalyse cooperation (Vivekananda, Schilling, and Smith Citation2014; Ratner et al. Citation2017b).

How can multi-stakeholder dialogue be used to assess and address the roots of environmental resource competition and conflict? This article summarises the outcomes and lessons from a three-year action research project focused on this question. The Strengthening Aquatic Resource Governance (STARGO) project supported institutional innovations aiming to build resilient livelihoods among poor, rural producers who depend on wetland and freshwater resources; generate gains in nutrition, income, welfare, and human security; and reduce the likelihood of broader social conflict. The project worked in three ecoregions: Lake Victoria, with a focus on Uganda; Lake Kariba, with a focus on Zambia; and the Tonle Sap Lake in Cambodia. These ecoregions are characterised by persistent poverty, high dependence on aquatic resources for food security and livelihoods, intense resource competition, limited ability of local stakeholders to effectively influence decision-making processes and policies, and significant new pressures that could lead to broader social conflict if not effectively addressed.

The article is organised as follows. The next section outlines the role of multi-stakeholder dialogue and the comparative action research process employed in this study. We then summarise the governance challenges and sources of resource conflict in each ecoregion. The subsequent section presents evidence on the institutional innovations that resulted from structured multi-stakeholder dialogue activities in each case. Drawing on these experiences, the final section provides a synthesis of policy lessons for governments, development agencies, and policy stakeholders working on resource governance, rural livelihoods, and conflict prevention. We detail guidance in four areas: building stakeholder commitment, understanding the institutional and governance context, involving local groups in the policy reform process, and embracing adaptability in programme implementation.

Multi-stakeholder dialogue and action research process

Managing allocation of and access to resources inevitably means addressing diverging interests that can lead to conflict. Conflicts also arise around negative environmental impacts, such as pollution of water resources or destruction of ecosystems. Even local or community-based resource conflicts often involve regional, national, or international actors and market dynamics (Engel and Korf Citation2005; Young and Goldman Citation2015).

Local resource conflicts are complex and highly context-specific. No simple causal links exist between natural resources and conflict. Environment and resource dynamics interact with broader social, political, cultural, and economic factors (Bächler, Spillman, and Suliman Citation2002; Carius Citation2006). If governance institutions are legitimate, inclusive, representative, and transparent, conflicts can often be solved or managed in a peaceful manner (Houdret, Kramer, and Carius Citation2010). On the other side, conflicts are more likely to emerge when certain groups are marginalised or excluded from resource decision-making. These dynamics can be exacerbated by strong group identities, which can be used to mobilise participants and escalate conflict (Colvin, Witt, and Lacey Citation2015). A deficit in effective and legitimate norms and institutions for governing natural resource conflicts can increase the risks of escalation: resource disputes can feed into or interact with other underlying social grievances and conflict structures, and if they turn violent, they can contribute to more generalised social instability (Castro and Nielsen Citation2003).

A range of interventions can be employed to strengthen the governance context in which environmental resource conflicts are addressed, to strengthen the institutions for collective action and collaborative resource management, and to strengthen practices of conflict management in the various “action arenas” in which actors voice their grievances (Ratner et al. Citation2013, Citation2017b). In the latter category, the practice of multi-stakeholder dialogue is suitable in situations where competing actors and potential collaborators are willing to meet and jointly assess the sources of current or future conflict and the strategies to address these. By contrast, where conflict is “hot” or parties are unwilling to enter into a dialogue process, conciliation processes or third-party mediation may be required, sometimes in combination with formal dispute resolution mechanisms (UNDP Citation2010; UNEP Citation2015; Ratner et al. Citation2017a).

This study employed an action research approach to co-develop and apply a common methodology to organise multi-stakeholder dialogue processes and evaluate the outcomes. Action research, as defined by Reason and Bradbury (Citation2008, 1), is:

“a participatory, democratic process concerned with developing practical knowing in the pursuit of worthwhile human purposes … It seeks to bring together action and reflection, theory and practice, in participation with others, in the pursuit of practical solutions to issues of pressing concern to people.”

A common constraint of action research, perhaps particularly common in the case of interpretivist approaches, is that insights from locally defined problems and solutions fail to have broader impact. “The bulk of action research takes place on a case by case basis” write Brydon-Miller et al. (Citation2003, 25), noting the need for “broader, societal-level action research initiatives where the local interventions are part of larger-scale networks and social change strategies”. Expanding the scope of action research initiatives requires “network building and similar efforts that can bring a broad range of actors to share ideas and practices” (Gustavsen, Hansson, and Qvale Citation2008, 64).

This research adopts an interpretivist approach to action research, with a particular focus on comparative processes to draw insights across sites and across regions. Working with teams in Zambia, Uganda, and Cambodia, the project developed guidance on a common approach to multi-stakeholder dialogue and action planning in the context of natural resource competition – the Collaborating for Resilience approach – in advance of initiating the dialogue processes in each study site, then revised on the basis of learning from these cases (Ratner and Smith Citation2014). The approach provides a set of orienting concepts, principles, and practices that different groups – including civil society organisations, development agencies, and governments – can adapt to the socio-cultural context and particular challenges at hand.

The process included several months of scoping in preparation for a sequence of multi-stakeholder workshops and follow-up outcome evaluation activities, conducted during 2012–14. The dialogue workshops, while adopting different tools, followed a common format broken into three phases, aimed at: (a) building a shared awareness of the issues, the possibilities for the future, and the constraints and opportunities of the current situation; (b) debate over different possible courses of action to pursue a common purpose; and (c) deciding on an action plan comprising commitments by individuals and multi-stakeholder teams (Ratner et al. Citation2017a).

Monitoring and evaluation of outcomes was based on the theory of change that underlay and guided each of the community-led actions and institutional innovations in the three regions. Following Augsberger (Citation1992), the outcome indicators focused primarily on the personal and relational dimensions of conflict and cooperation. The personal dimension includes individual attitudes toward members of another group, while the relational dimension covers the relationships and patterns of interaction between individuals and groups. In addition to highlighting progress in addressing particular disputes, this approach enabled research teams to identify early evidence of innovations in governance.

Monitoring and evaluation activities included structured approaches such as questionnaires, focus group discussions, and individual interviews, and narrative descriptions of personal experience such as participant diaries. Research team members also convened local stakeholders periodically to discuss and review findings as a means of validation and collective learning. A cross-regional synthesis workshop provided an opportunity for teams from each of the countries to undertake structured comparison of outcome evidence, formulate initial lessons, and identify elements that required further probing or validation through follow-up interviews and field visits.

Governance challenges and sources of resource conflict in three lake systems

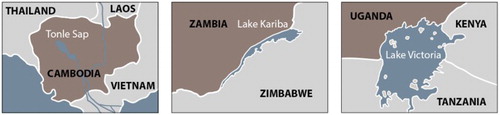

Each of the three ecoregions targeted in the project concerns a large lake ecosystem of international significance (see ). The two African lake systems are bordered by multiple states (Uganda, Kenya, and Tanzania in the case of Lake Victoria; Zambia and Zimbabwe in the case of Lake Kariba), while Tonle Sap Lake in Cambodia is directly affected by decisions of upstream and downstream users of the Mekong River system (China, Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam).

In all three lake systems, fisheries resources are of central importance for food security, rural livelihoods, and national economies. For this reason, conflict potential can increase if the resources and ecosystems are allowed to degrade to the point where they cannot sustain rural livelihoods (Young and Goldman Citation2015). Sustainable management is thus critical to reducing the vulnerabilities that poor families face and to maintaining social stability.

Amid increasing competition over natural resources, national governments in all three focal countries (Uganda, Zambia, and Cambodia) have launched significant policy initiatives aimed at decentralisation of rural development planning, including natural resource management. This reflects a broader global trend toward devolution of authority from central to local levels. This transfer is intended to support community livelihoods, as well as increase participation of local communities in development planning (OECD Citation2004). In the fisheries sector, decentralisation includes efforts in all three countries to institutionalise co-management. However, limited support services, weak organisational capacity of community organisations, and marginalisation of poor fishing households from influence in policy formulation and implementation have posed significant obstacles in each country.

Conflicts in the three lake systems evolved differently as a result of region-specific histories and institutional dynamics. In Lake Victoria, many small conflicts persist at the communal level that have the potential to escalate quickly and immobilise fisheries management processes. Conflict behaviours at the outset of the study period in Lake Victoria included verbal confrontations and mutual threats between fishers and higher-level authorities, shaming and fines by local authorities, acts of civil disorder by groups within fishing communities, and property destruction and violence by both community members and government authorities. For example, taxes for landing fish at one landing site were increased by the sub-county leaders without proper consultation with local stakeholders. This resulted in further interpersonal and institutional conflicts that were angrily aired during meetings between the STARGO team, the fishing community, and leaders from higher levels of public administration. Theft of fishing gear was also a frequent source of local conflict.

In Zambia, conflicts among natural resource users developed in the particularly sensitive context of ethnic marginalisation and change in the racial makeup of the commercial fishing industry. When the Zambezi River was dammed in 1959 to create Lake Kariba, 35,000 households were relocated, sometimes under duress from the state (Bourdillon, Cheater, and Murphree Citation1985). These communities, mainly of the Gwembe Tonga ethnic group, remain marginalised politically, socially, and economically. In recent years, the number of black Zambians in the historically white-dominated commercial fishing industry increased. However, frequent conflicts were reported between the established white commercial fishers, new “small-scale” semi-commercial fishers from urban areas of Zambia, and artisanal players (Mhlanga Citation2009). Recent commercial aquaculture and tourism investments on the lake spawned new tensions over access to the shoreline and fishing grounds. Conflict behaviours included destruction of gill nets by commercial “kapenta” fishing vessels, confiscation of nets by hotel owners, fishing in prohibited zones, and trespassing by villagers on private property.

In Cambodia, fisheries conflicts have been violent in the past, and have included large-scale protests, which helped motivate a series of reforms. Cambodia’s freshwater fishery sector reform is a regionally significant example of a policy shift toward decentralised natural resource management. The reform was implemented in two main waves. The first took place in 2000–01, when 56% of the area covered by fishing lots in Tonle Sap Lake was released for community access. In early 2012, the second wave of reform culminated in the complete removal of all inland commercial fishing lots. This was part of a broader campaign to address poor management, widespread illegal fishing, and ongoing fisheries conflicts around Tonle Sap Lake (Ratner, Mam, and Halpern Citation2014). Many lakeshore fishing communities also face disputes over conversion of seasonally flooded forest lands for dry-season rice cultivation, which is often backed by powerful investors from outside the local area (Keskinen et al. Citation2007; Ratner et al. Citation2017c).

Despite variation among the three regions in conflict behaviours and conflict intensities, there are many similarities. In all three ecoregions, most conflicts stem from attempts to control or limit community access to fisheries resources; for example, through licensing, prohibitions on use of certain fishing gears, fishing in prescribed zones, and by taxation or other fees on fishing activities. When describing conflict causes, fishers in Lake Kariba, Lake Victoria and Tonle Sap all pointed to a “shrinking commons”, with increasing pressure on the fisheries resources due to greater fishing effort. Fishing yields per unit effort were reported to be decreasing, pushing fishers toward illegal practices and theft. Conflicts between large-scale and small-scale fishers were also common.

In the context of broader decentralisation reforms, the governments of each of the three focal countries have taken steps to address the intensifying claims on fisheries resources through varying forms of co-management. In Uganda, fisheries growth has been primarily export-driven (Benkenstein Citation2011). Policy has therefore strongly supported industrial fishers, who are predominantly foreigners. This situation has left villagers in many local beach management units feeling overlooked. In Zambia, the government tried to create a space for indigenous Zambians to take part in commercial fishing under a fisheries law revised in 2011. However, the institutions to support co-management remain incomplete. In Cambodia, government policy has shifted to prioritise the livelihoods of small-scale fishers over commercial interests in freshwater fisheries, with emphasis on strengthening a broad network of community fisheries (Ratner Citation2011; Ratner et al. Citation2017c).

Decentralising natural resource management brings a host of challenges. These often include an increase in competition as local actors manoeuvre to access new rights, influence resource allocation decisions, capture positions of power at the local level, or take advantage of gaps in enforcement (International Crisis Group Citation2012). At the same time, decentralisation reforms can contribute to local dispute resolution while helping build institutional capacities and relationships for improved resource governance. To pursue such gains, practitioners and policymakers need to pay attention to power differences among actors; support mediation between stakeholders; transparently specify benefit and cost sharing between communities, the private sector and governments; safeguard against manipulation of community representative bodies by individuals or interest groups; and build measures for gender equity into resource management planning (Nunan Citation2006).

Institutional innovations and outcomes

Working in the context of these dynamic and contested policy reform processes, the STARGO project supported dialogue efforts not only to build a shared understanding of the sources of current and potential future resource competition, and to explore options for addressing these, but also to foster collective action through institutional innovations to strengthen livelihood resilience. Innovations supported included attempts to increase community voices in private sector investment decisions and efforts to secure access rights for marginalised households in the face of competition. Other innovations sought to strengthen community-based co-management, resource protection, and public health. Although in each case the research team focused on communities that depend significantly on fishing for income and livelihood, the priorities that emerged from the participatory dialogue processes were not restricted to fisheries or natural resource management, as the dialogues provided space for consideration of multiple dimensions of livelihood resilience and vulnerability.

summarises the key outcomes for each case, grouped in four categories: (1) reduced conflict and improved collaboration among user groups; (2) new resource management practices; (3) responsiveness of authorities; and (4) scaling. The following subsections further describe the institutional innovations and outcomes in each case study, as measured through evaluations led by local actors.

Table 1. Outcomes of local innovations, as documented through participatory evaluation.

Lake Victoria

Of the three cases, Lake Victoria presented the most challenging context in which to foster dialogue and promote collective action, because of the intensity of recent confrontations between fishers and government representatives, the severely reduced livelihood opportunities in the sector, a high degree of migration and therefore few recent experiences of successful community action, along with a generally low state of public services and poor responsiveness of government to community needs. Recognising these constraints, stakeholders chose actions they felt would directly reduce poverty and vulnerability and indirectly reduce resource competition in their communities.

In the main site of Kachanga, community members sought to reduce faecal contamination to water resources, fisheries, and agricultural lands as a way to improve water quality, human health and productivity, and fish health. There, community members, beach management units, the Department of Fisheries Resources, and local and district administrations worked together successfully to build a new sanitation facility – a communal latrine designed to also generate biogas. The collaboration strengthened linkages with relevant supportive institutions at community, sub-county, district, regional, and national levels, and has drawn interest from other communities.

During the initial multi-stakeholder workshop, there were clear signs of tension and frequent verbal disputes between fishers, members of beach management units, and Department of Fisheries Resources officers. Once the work started, however, coordination meetings attracted more participants, and by the end of the process the attitudes of community members interviewed had shifted from scepticism to conviction about their central role in setting priorities. Villagers who took on leadership roles as champions of the latrine and biogas facility also earned a new level of legitimacy and trust from community members. They subsequently mobilised community contributions to construct a public kitchen fuelled by the biogas, providing a safe and affordable way for villagers to boil water and cook.

The planning, procurement, and construction of the sanitation facility also increased opportunities for dialogue, networking, and communication among the community-level institutions, with higher administrative bodies, and among community members. Following completion of the biogas facility and having put in place a system to manage its upkeep, the same collection of leaders subsequently pursued support from government and outside agencies to address the lack of clean water for drinking and domestic use. This includes members of the beach management unit responsible for planning and implementing fisheries co-management activities, indicating a more active role and improved prospects for future engagement in management efforts beyond the local scale.

The outcome evaluation also noted an influence on local government behaviours and priorities in response to locally defined needs. Officials from Masaka District and technical extension staff cited the practical relevance of the activities carried out in Kachanga for planning further developments in the water, sanitation, and health sectors, and arranged a series of visits from others in the sector to highlight the experience as a success in community-driven development. Finally, the innovations yielded a range of new linkages to scale out lessons and approaches, in cooperation with UNICEF, the German Society for International Cooperation (GIZ), the Ugandan Ministry of Water and Environment, and UN-HABITAT.

Lake Kariba

In Lake Kariba, the focal site was a set of lakeshore villages around Kamimbi in Siavonga District. The region is characterised by a long-standing parallel structure of authority between the state and traditional chiefdoms, with the chiefs exercising decisions over allocation of communal lands and the Department of Fisheries administering allocation of fishing rights, including licenses for commercial operators. On top of the tensions between commercial fishers and small-scale operators, the arrival of well-capitalised private investors in the aquaculture sector introduced a new dimension of competing resource use demands. These investors require substantial areas of the lake for cage aquaculture operations as well as land along the shore for support operations and processing facilities.

Actions identified as a result of the dialogue workshops included activities focused on managing current and potential conflict arising from the use of the fishery, collaboration to resolve tension over use of the land on the lakeshore, and development of local capacity to engage and leverage a “win-win” relationship with current and future private sector investors in the region. Project activities included facilitating meetings among the communities affected by the privatisation of previously common-property land, between communities and the traditional leaders responsible for allocating land to investors, and between communities and investors.

The initial dialogue workshop revealed that community members lacked a voice in decisions over the allocation of shoreline and fishing areas to investors. By law, large-scale investments are subject to environmental impact assessment procedures, which include requirements for community participation. The Zambian Environmental Management Agency was therefore invited to train fishing communities and Department of Fisheries staff on environmental impact assessment provisions. Using environmental impact assessment as a platform to promote dialogue between investors on the lakeshore and fishing communities, the process yielded a negotiated agreement with one of the investors to address how to maintain access routes villagers and their children use that the investor had blocked.

The village management committee also found that the dialogue approach brought it a new legitimacy, enabling it to address other community concerns in discussions with the regional chief. Regarding land allocation to investors, for example, village leaders report that the chief has shifted toward a much more inclusive mode of consultation. Villagers also report improved collaboration and a marked reduction in complaints between the small-scale and commercial fishers of “kapenta” (the prime, wild-caught commercial fish in the lake), following mediation support from the Department of Fisheries. Women villagers identified transboundary fish trade with Zimbabwe as a significant concern and source of vulnerability, so additional efforts explored improvements to current fish trade arrangements, including the burdensome administrative procedures at the border that often lead to significant spoilage and losses for traders, predominately women. The action research prompted follow-up actions by the Department of Fisheries and SmartFish, an NGO focused on fish trade, to address these concerns.

Finally, the local innovations generated significant interest in applying the lessons to national policy implementation. Zambian Environmental Management Agency staff made plans to incorporate the dialogue principles into their support for environmental impact assessment implementation in other areas. Similarly, the director of the Department of Fisheries identified the STARGO collaboration as a key source of learning in the development of a renewed national policy on fisheries co-management.

Tonle Sap Lake

On Cambodia’s Tonle Sap Lake, prior mobilisation by civil society networks had already significantly influenced the trajectory of fishery governance reforms, expanding the domain officially designated for community fisheries. Yet widespread illegal fishing, poor enforcement, and local conflicts over water use for fisheries and dry-season agriculture meant tensions remained high both in floating villages on the lake and those along the shore. Building on prior dialogue efforts linking five provinces around the lake (Ratner, Mam, and Halpern Citation2014), the action research process focused on Kompong Thom Province, known both for persistent conflicts and active and vocal advocacy efforts by community fishers.

Multi-stakeholder dialogue sessions in three focal sites helped local actors develop community action plans. Initial plans focused on advocacy for increasing access to fishing grounds. Yet, as it became clear that the area of public access and community fisheries would again be significantly expanded, local priorities shifted to making community fisheries more effective. This included efforts aimed at improving resource protection and enforcement on the lake and in floodplain habitats, as well as developing proposals to adapt the rules for fisheries exploitation.

A first significant outcome was implementation of joint patrolling to improve resource protection. Community fishery organisations in all three focal communities restructured their management and strengthened their patrolling. An innovation was the use of joint patrols combining community fishery organisation members and fishery officers, which both cited as a sign of improved collaboration. Community fishery organisation committees were reported to meet more regularly and cited improved collaboration across different local management areas. This included collaboration with village and commune authorities and local police across the three sites in cracking down on illegal fishing, as well as raising awareness about fisheries regulations.

The evaluation also noted reduced conflict between fishers and dry-season rice farmers. A local dialogue resulted in a negotiated agreement on water allocation between dry-season rice farming and maintaining water for fisheries. The community fishery organisation and dry-season rice farmers association reached a verbal agreement in the presence of provincial line departments, and Fisheries Administration officials subsequently followed up to formalise the agreement.

An additional significant outcome was government support to pilot a new form of management known as community-based commercial production. The pilot model would permit commercial capture fisheries under community management, with safeguards to ensure adequate resource protection and benefit sharing. The model has not yet been implemented on the Tonle Sap Lake, as it would require a change in or exemption from current regulation, but civil society groups have continued to organise for approval of the details of a pilot effort.

Lastly, the evaluation found evidence of scaling out lessons from the dialogue approach. The Fisheries Administration director at the time affirmed a need for further participatory, multi-stakeholder monitoring and evaluation processes to assist in implementation of the ongoing fisheries reforms. The focal communities in Kompong Thom shared their experiences with 10 other communities around the Tonle Sap Lake through a series of knowledge marketplace events. And in the mountainous region of northeast Cambodia, the Analysing Development Issues Centre has applied its experience with the dialogue approach to its work on indigenous people’s land rights and community forestry.

Lessons learnt: investing in capacity for conflict management

Project experience in the three ecoregions confirmed the value of a collaborative, stakeholder-driven approach to address the roots of resource conflict. Cross-regional comparison of the action research cases also highlighted a range of emerging lessons for policy officials and development agencies planning initiatives to build capacity for conflict management and collaboration in natural resource management. This section summarises key lessons drawn from the cross-regional comparison.

A dialogue approach requires appropriate conditions, time, and stakeholder commitment

Dialogue processes can reveal unexpected connections between local livelihood resilience, vulnerability, and conflict transformation. In the Lake Victoria case, for example, community members identified pressing needs that could form a focus for joint action, which built the confidence and legitimacy to then expand out to other areas linking environmental resource management and community health. On the basis of early successes, district officials became more convinced of the benefits of engaging with a community-driven process and subsequently showed more responsiveness. Likewise, in Lake Kariba, both investors and traditional chiefs were at first sceptical of the dialogue process but then identified ways that it could improve their ability to operate. As building such stakeholder commitment takes time, organisers and agencies that fund these activities need to demonstrate significant patience in the pace of change.

Past experiences with collective action influence people’s readiness to collaborate. Disappointing past experiences with collective action or failed attempts to gain the support of state agencies can sap people’s interest in attempting new joint efforts. At the Kachanga landing site, there were few prior examples of the whole community working together to reach an overarching community goal. By contrast, in the floating village of Phat Sanday in Cambodia, memories of working together to advocate for fisheries reform were still quite fresh (Ratner, Mam, and Halpern Citation2014). This motivated people to work toward more complex efforts such as joint patrolling and community-based commercial production.

Sustaining new collaborations requires long-term funding and commitment built over time. Dialogue participants will only see collaborative processes as valuable if the outcomes bring direct benefits as defined by the communities concerned. Outside investments may deliver few results if not matched by local actors’ belief in the value of collaboration, which takes time to build. Following incidents of violent confrontation over fisheries revenue collection and fisheries enforcement in Lake Victoria, trust had been eroded to such a degree that long-term investments needed to be made in capacity building for conflict management at the community level. This is why actions responding to an immediate expressed need – improved sanitation – were appropriate to build experience and improve the prospects for subsequent collaboration on resource management challenges at larger ecosystem scales.

Understanding the institutional and governance context is key to identifying appropriate areas for support

Sometimes there is space for innovation in the absence of policy change. Earlier initiatives toward co-management in both Lake Kariba and Tonle Sap Lake were implemented despite the lack of an enabling policy or law. In Tonle Sap, early experimentation with community fisheries provided a positive example and gave legitimacy to subsequent legal reforms and a national rollout of community-based management. In Lake Kariba, on the other hand, earlier efforts left few examples of active village-level organisations a decade later. According to some observers, co-management projects in Zambia were historically largely donor-driven, failing to build local institutional capacity and commitment (Malasha Citation2007). A policy mandate cannot substitute for careful attention to stakeholder roles, relationships, and motivations in initiatives to promote collaborative resource management.

Reform can also provide an opening for local innovation. In Cambodia, the fisheries policy reform opened up new opportunities for collaboration and experimentation. Joint patrols helped reduce tensions between small-scale fishers and local authorities, though they lack an ongoing source of funding. Similarly, by removing an old system of management based on commercial concessions, the reform has created an opportunity to explore new models, such as community-based commercial fisheries production. Communities see this as an opportunity to boost local incomes and generate funds for resource protection – goals that align with national policy for the sector.

Promoting collaboration requires national agencies responsive to local priorities. In Lake Kariba, the decentralisation policy provided a rationale for co-management, but the flow of resources to the local level was very slight and there was very little actual support from central agencies. Recognising this history, the partners found it critical to demonstrate alternative approaches locally and to engage higher-level agencies along the way. In Cambodia, locals often find it difficult to distinguish among the roles of agencies such as the Tonle Sap Authority, the Fisheries Administration, and environment departments at the provincial level. Better distinguishing the roles of different agencies in the success of community fisheries is an important step toward making them more accessible and responsive, as well as strengthening inter-agency collaboration.

Policy changes can aggravate conflicts when instituted without adequate stakeholder involvement

Disconnects between national policy initiatives and local needs contribute to local tension and conflict. Dialogue participants in all three regions identified important instances in which they felt national policy was at odds with local needs. For example, participants argued that Ugandan fisheries management policy focused on sustaining Nile perch production to protect export revenue; local communities voiced concern that they benefit little directly but are nevertheless asked to carry the burden of protection. In Zambia, agricultural policy favours maize production, with fishers feeling overlooked and left to fend for themselves amid new developments like aquaculture investment or increases in cross-border fishing.

Rules changed without community participation can prompt new disputes. In Cambodia, the recent wave of fisheries reform explicitly recognised the need for more equitable resource access. Yet, in an effort to introduce new rules quickly, decisions on allocation of fishing grounds and gear regulation were instituted with little consultation. Rules formulated without community consultation have been viewed as unsuited to local needs, building tension between communities and enforcement entities. The reforms have also raised new ecological risks as more people are drawn to fish, particularly in the floodplain, increasing pressure on sensitive fish habitats and creating the potential for more conflict over limited resources.

Achieving effective stakeholder involvement in reform decisions depends on robust civil society organisations. In Cambodia, where freshwater fisheries policy is a high priority compared to many countries, civil society networks have achieved notable success as advocates of reform on the Tonle Sap Lake. By contrast, in Uganda, the relatively low policy priority on small-scale fisheries means fishing communities have found it much more difficult to advocate for the sector and their priorities in local development planning processes. In Zambia, the renewed policy focus on fisheries co-management prompted the Zambian Environmental Management Agency and the Department of Fisheries to increase their outreach to local communities. However, a shortage of civil society networks linking fishing communities and representing their interests remains an obstacle to effective implementation.

Investing in collaboration and innovation requires a tolerance for uncertainty and risk

Supporting local innovations means reorienting many of the conventional practices of project management. In the STARGO experience, it was critical for teams in each ecoregion to seek out ways to support collaborative actions by local and national stakeholders in line with the agreed purpose, yet with a sense of flexibility about the specific objectives that would emerge. Blueprint plans, fixed timelines of activities, and centralised decision-making had to give way to adaptability and joint planning in mixed stakeholder groups. In each of the cases, the scoping and dialogue processes helped to identify local champions of change who proved critical in catalysing collective action. Not necessarily in formal positions of leadership, these change agents drew their influence from first-hand knowledge of the issues, an ability to relate to multiple stakeholders, and, most critically, trust earned from their interactions with others over time.

Authorities need to demonstrate openness to solutions that build on local insight and initiative. Small “early wins” can help build local commitment and demonstrate that the space for innovation is authentic. In Lake Kariba, initiating multi-stakeholder dialogue events and facilitating joint action planning was sufficient for local groups to build a sense of shared purpose. In subsequent negotiations with investors, they felt empowered by a sense that national authorities and the traditional chief would hear their concerns. In Lake Victoria, constructive communication between community members and local government authorities intensified after the initial multi-stakeholder dialogue, prompting Kachanga community members to raise their own funds for the common sanitation project.

Embracing uncertainty and a measure of risk opens the possibility of more fundamental advances in conflict management. In Tonle Sap, the policy reforms announced soon after the start of project implementation shifted the realm of the possible. Recognising its limited capacity and the suddenly expanded area of fishing grounds released from the commercial lots, the Fisheries Administration became the key proponent of more ambitious plans to support community fisheries. The deputy director general in charge of community fisheries, in particular, took the lead in proposing aggressive milestones for negotiating and piloting efforts in joint patrolling and community-based commercial production. This illustrates how the domain of influence for an initiative can change quickly, and how efforts to invest in capacity for conflict management can accelerate when these openings are identified and plans shifted accordingly.

Conclusion

Conflict management is an intrinsic element of natural resource management, and becomes increasingly important amid growing pressure on natural resources from local uses, as well as from external drivers such as climate change and international private sector investment. If policymakers and practitioners aim to improve livelihood resilience and reduce vulnerabilities of poor rural households, issues of resource competition and conflict management cannot be ignored. While multi-stakeholder dialogue and action planning is not a suitable approach in all instances, it can be an important element of programmes investing in food security, conservation, rural economic development, conflict prevention, and inclusive governance.

Effective representation of resource users’ interests in decision-making, along with strong systems of accountability, can in turn contribute to more equitable decisions on resource allocation, access and management rights. The link between improved collaboration and long-term improvements in governance is, however, neither direct nor assured. Participatory processes, if not grounded in an awareness of the broader governance context, can reinforce existing power inequities (Resurreccion, Real, and Pantana Citation2004). Yet effective dialogue processes can strengthen marginalised voices, help make incremental improvements and provide examples of innovation that lay the groundwork for more systemic reforms. As the cases from Lake Victoria, Lake Kariba, and Tonle Sap Lake also indicate, however, making progress to strengthen governance requires long-term commitment, engagement of actors at multiple levels, and considerable flexibility to identify and pursue opportunities for policy and institutional reform.

Systematic efforts are needed to compare and analyse the results of future experience in this domain across multiple resource systems and social-political environments. This can help develop a more refined understanding of what strategies work under what circumstances and deepen our knowledge of the factors that contribute to lasting transformation. While there remains much to learn, the experiences documented here demonstrate that a structured approach to multi-stakeholder dialogue and learning through action research is feasible in a variety of contexts, can deliver measurable results even in a relatively short time period, and does not require a dramatic policy change or institutional reform to get started.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors. This article includes material extracted and adapted from the following programme report: B. D. Ratner, C. Burnley, S. Mugisha, E. Madzudzo, I. Oeur, M. Kosal, L. Rüttinger, and P. Adriazola. 2014. “Dialogue to Address the Roots of Resource Competition: Lessons for Policy and Practice.” Penang: Collaborating for Resilience.

Notes on contributors

Blake D. Ratner is the Executive Director of Collaborating for Resilience, WorldFish/CGIAR, Penang, Malaysia.

Clementine Burnley is a member of Migration Council Berlin.

Samuel Mugisha is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Zoology, Makerere University, Kampala.

Elias Madzudzo was formerly a Scientist with WorldFish, Lusaka.

Il Oeur is Executive Director of the Analysing Development Issues Centre, Phnom Penh.

Mam Kosal is a Research Analyst at WorldFish, Phnom Penh.

Lukas Rüttinger is a Senior Project Manager at adelphi research, Berlin.

Loziwe Chilufya is a researcher with the Department of Fisheries, Lusaka.

Paola Adriázola is a Project Manager and Climate Governance Speclalist at adelphi research, Berlin.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Augsberger, D. 1992. Conflict Mediation Across Cultures: Pathways and Patterns. Kentucky: Westminster & John Knox.

- Bächler, G., K. Spillman, and M. Suliman, eds. 2002. Transformation of Resource Conflicts: Approaches and Instruments. Bern: Peter Lang AG/European Academic Publishers.

- Benkenstein, A. 2011. “Troubled Waters”: Sustaining Uganda’s Lake Victoria Nile Perch Fishery. Cape Town: South African Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA). Accessed October 9, 2016. www.saiia.org.za/research-reports/troubled-waters-sustaining-uganda-s-lake-victoria-nile-perch-fishery.html.

- Binningsbo, H., and S. A. Rustad. 2008. Resource Conflicts, Resource Management and Post-Conflict Peace. PRIO Working Paper. Oslo: Uppsala University & International Peace Research Institute.

- Bourdillon, M. F. C., A. P. Cheater, and M. W. Murphree. 1985. “Studies of Fishing on Lake Kariba.” Mambo Occasional Papers – Socio-Economic Series No. 20.

- Brydon-Miller, M., D. Greenwood, P. Maguire. 2003. “Why action research?” Action Research 1 (1): 9–28. doi: 10.1177/14767503030011002

- Carius, A. 2006. Environmental Cooperation as an Instrument of Crisis Prevention and Peacebuilding: Conditions for Success and Constraints. Berlin: Adelphi Consult.

- Castro, P., and E. Nielsen. 2003. Natural Resource Conflict Management Case Studies: An Analysis of Power, Participation and Protected Areas. Rome: FAO.

- Colvin, R. M., G. B. Witt, and J. Lacey. 2015. “The Social Identity Approach to Understanding Socio-Political Conflict in Environmental and Natural Resources Management.” Global Environmental Change 34: 237–246. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.07.011

- Engel, A., and B. Korf. 2005. Negotiation and Mediation Techniques for Natural Resource Management. Rome: FAO.

- Gustavsen, B., A. Hansson, and T. U. Qvale. 2008. “Action Research and the Challenge of Scope.” In The SAGE Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice, 63–76. London: Sage.

- Houdret, A., A. Kramer, and A. Carius. 2010. The Water Security Nexus: Challenges and Opportunities for Development Cooperation. Berlin: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ).

- International Crisis Group. 2012. Indonesia: Defying the State. Asia Briefing No. 138. Brussels: International Crisis Group. Accessed October 9, 2016. www.crisisgroup.org/~/media/Files/asia/south-east-asia/indonesia/b138-indonesia-defying-the-state.pdf.

- Keskinen, M., M. Käkönen, T. Prom, and O. Varis. 2007. “The Tonle Sap Lake, Cambodia: Water-Related Conflicts with Abundance of Water.” The Economics of Peace and Security Journal 2 (2): 49–59. doi: 10.15355/epsj.2.2.49

- Malasha, I. 2007. “The Governance of Small Scale Fisheries in Zambia.” Paper submitted to the research project on food security and poverty alleviation through improved valuation and governance of river fisheries, Penang: WorldFish.

- Mhlanga, L. 2009. “Fragmentation of Resource Governance Along the Shoreline of Lake Kariba, Zimbabwe.” Development Southern Africa 26 (4): 585–596. doi: 10.1080/03768350903181365

- Nunan, F. 2006. “Planning for Integrated Lake Management in Uganda: Lessons for Sustainable and Effective Planning Processes.” Lakes and Reservoirs: Research and Management 11: 189–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1770.2006.00305.x

- OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development). 2004. “Lessons Learned on Donor Support to Decentralisation and Local Governance.” DAC Evaluation Series. Accessed October 9, 2016. www.oecd.org/development/evaluation/30395116.pdf.

- Ratner, B. D. 2011. Common-pool Resources, Livelihoods, and Resilience: Critical Challenges for Governance in Cambodia. IFPRI Discussion Paper Series. Washington, DC: IFPRI. Accessed October 9, 2016. www.ifpri.org/sites/default/files/publications/ifpridp01149.pdf.

- Ratner, B. D., C. Burnley, S. Mugisha, E. Madzudzo, I. Oeur, K. Mam, L. Rüttinger, L. Chilufya, and P. Adriázola. 2017a. “Facilitating Multistakeholder Dialogue to Manage Natural Resource Competition: A Synthesis of Lessons From Uganda, Zambia, and Cambodia.” International Journal of the Commons 11: 733–753. doi: 10.18352/ijc.748

- Ratner, B. D., K. Mam, and G. Halpern. 2014. “Collaborating for Resilience: Conflict, Collective Action, and Transformation on Cambodia’s Tonle Sap Lake.” Ecology and Society 19 (3): 31. doi: 10.5751/ES-06400-190331

- Ratner, B. D., R. Meinzen-Dick, J. Hellin, E. Mapedza, J. Unruh, W. Veening, E. Haglund, C. May, and C. Bruch. 2017b. “Addressing Conflict Through Collective Action in Natural Resource Management.” International Journal of the Commons 11 (2): 877–906. doi: 10.18352/ijc.768

- Ratner, B. D., R. Meinzen-Dick, C. May, and E. Haglund. 2013. “Resource Conflict, Collective Action, and Resilience: An Analytical Framework.” International Journal of the Commons 7 (1): 183. doi: 10.18352/ijc.276

- Ratner, B. D., and W. E. Smith. 2014. “Collaborating for Resilience: A Practitioner’s Guide.” Penag: Collaborating for Resilience. Accessed October 9, 2016. http://coresilience.org/manuals/guide.

- Ratner, B. D., S. So, K. Mam, I. Oeur, and S. Kim. 2017c. “Conflict and Collective Action in Tonle Sap Fisheries: Adapting Governance to Support Community Livelihoods.” Natural Resources Forum 41 (2): 71–82. doi: 10.1111/1477-8947.12120

- Reason, P., and H. Bradbury. 2008. The Sage Handbook of Action Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: London: Sage.

- Resurreccion, B. P., M. Jane Real, and P. Pantana. 2004. “Officialising Strategies: Participatory Processes and Gender in Thailand’s Water Resources Sector.” Development in Practice 14 (4): 521–532. doi: 10.1080/09614520410001686115

- Rüttinger, L., A. Morin, A. Houdret, D. Taenzler, and C. Burnley. 2012. Water, Crisis and Climate Change Assessment Framework (WACCAF). Brussels: Initiative for Peacebuilding Early Warning.

- Rüttinger, L., D. Smith, G. Stang, D. Tänzler, and J. Vivekananda. 2015. A New Climate for Peace: Taking Action on Climate and Fragility Risks. Berlin: Adelphi, International Alert, Woodrow Wilson Center, and European Union Institute for Security Studies.

- UNDP. 2010. “Capacity Development in Post-Conflict Countries.” Global Event Working Paper. Accessed October 9, 2016. www.undp.org/content/dam/aplaws/publication/en/publications/capacity-development/capacity-development-in-post-conflict-countries/CD in post conflict countries.pdf.

- UNEP. 2009. From Conflict to Peacebuilding: The Role of Natural Resources and the Environment. Nairobi: United Nations Environment Program.

- UNEP. 2015. Natural Resources and Conflicts: A Guide for Mediation Practitioners. Nairobi: United Nations Environment Program. Accessed October 9, 2016. http://postconflict.unep.ch/publications/UNDPA_UNEP_NRC_Mediation_full.pdf.

- Vivekananda, J., J. Schilling, and D. Smith. 2014. “Climate Resilience in Fragile and Conflict-Affected Societies: Concepts and Approaches.” Development in Practice 24 (4): 487–501. doi: 10.1080/09614524.2014.909384

- Willis, J., and C. L. Edwards. 2014. “Varieties of Action Research.” In Action Research: Models, Methods, and Examples, edited by J. Willis, and C. L. Edwards, 45–84. London: Eurospan.

- Young, H., and L. Goldman, eds. 2015. Livelihoods, Natural Resources, and Post-Conflict Peacebuilding. London: Earthscan.